COVID-19: Stress and Anxiety

[Additional essays and videocasts regarding psychological ramifications of the COVID-19 virus outbreak can be found at: https://communitiescollaborating.com/[

The COVID-19 virus knows all about the human psyche. The virus is aware that we experience stress and become anxious when we keep a distance from other people and are forced to isolate ourselves from direct, physical contact with the people we love and cherish. Under conditons of stress and as we become more anxious, our vulnerability also increases — leaving us even more anxious. A vicious cycle . . . and a cycle that we need to stop!!

This essay includes material prepared by members of the Global Psychology Task Force–a group of experienced professional psychologists from around the world who have come together to address the psychological ramifications of the COVID-19 virus. They have prepared a website (www.communities collaborating.com) that incorporates essays, video clips and links to other references that address these ramifications. This essay is derived from the content of this website.

Stress Ruts, Lions and Lumens

We start with a brief video presentation by Dr. William Bergquist, a member of the Global Psychology Task Force. He has titled his presentation: “Stress Ruts, Lions and Lumens in the Age of the Pandemic”:

Reducing the Stress and Anxiety

This essay concerns the way to reduce the stress and anxiety. In addressing this psychological dynamic we turn to both the anxiety aroused by those who have tested positive for the virus and those who have not been tested or have been tested and are negative but still worry about the physical and psychological health of other people in their life, as well as their own economic health and the economic and societal health of their community and country.

https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/3/21/21188362/manage-anxiety-pandemic

We turn now to someone who have been infected by COVID-19

Managing the Anxiety as Someone Who Has Been Infected

The anxiety associated with any major illness is quite understandable and is not in any way a sign of weakness. There are many ways in which to address this anxiety–such as looking to loved ones for support (even if they can’t be physically present), reducing other sources of stress in one’s life, identifying daily plans for dealing with the virus–and most importantly taking actions that enable you to feel less powerless and victimized.

It is perhaps best to turn from these general recommendations to the insights offered by someone who has been infected and struggled for a lengthy period of time with the infestation and related fever and isolation. This person is Dr. Suzanne Brennen-Nathan, one or our Global Psychology Task Force members. Suzanne is a highly experienced psychotherapist who has specialized in the treatment of trauma in her clinical practice. Who better to reflect on the illness and offer recommendations then someone “who has been there” and has expertise in the traumatizing impact of a major illness like COVID-19. Suzanne has been interviewed by Dr. William Bergquist, another member of the Task Force:

Managing the Anxiety as Someone Who Hasn’t Been Tested or Is Negative But Still Fearful

What about those of us who have not tested positive for COVID-19 or have not been tested at all. At the heart of the matter in facing the challenges associated with the COVID-19 virus — whether these challenges be financial, vocational or family related–is the stress that inevitably is induced when we think about, feel about and take action about the virus’ threatening nature.

We therefore begin this statement about action to be taken with an excellent presentation by one of our task force members, Christy Lewis:

To begin a cross-cultural reflection on the psychological ramifications of the COVID-19 virus, we offer an essay on the way in which one of our Task Force members, Eliza Wong, Psy.D., works with highly anxious clients in her home country: Singapore.

Dealing with Anxiety during COVID-19 in Singapore

We hope these perspectives on stress and anxiety in the age of the COVID-19 virus invasion provides some guidance for you in better understanding the psychological impact of the virus and identifying actions you can take to help ameliorate this impact.

- Related Articles

- More By William Bergquist

- More In Health / Biology

The Shattered Tin Man Midst the Shock and Awe in Mid-21st Century Societies I: Shattering and Shock

Lay me down to sleep: designing the environment for high quality rest, the wonder of interpersonal relationships via: culprits of division and bach family members as exemplars of relating midst differences, i dreamed i was flying: a developmental representation of competence, snuggling in: what makes us comfortable when we sleep, the intricate and varied dances of friendship i: turnings and types, leadership in the midst of heath care complexity ii: coaching, balancing and moving across multiple cultures, leadership in the midst of heath care complexity i: team operations and design, delivering health care in complex adaptive systems i: the nature of dynamic systems, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

I wish to introduce a quite different interpretation regarding the presence of flight in t…

- Counseling / Coaching

- Health / Biology

- Sleeping/Dreaming

- Personality

- Developmental

- Cognitive and Affective

- Psychobiographies

- Disclosure / Feedback

- Influence / Communication

- Cooperation / Competition

- Unconscious Dynamics

- Intervention

- Child / Adolescent

- System Dynamics

- Organizational Behavior / Dynamics

- Development / Stages

- Organizational Types / Structures

- System Dynamics / Complexity

- Assessment / Process Observation

- Intervention / Consulting

- Cross Cultural

- Behavioral Economics

- Technologies

- Edge of Knowledge

- Organizational

- Laboratories

- Field Stations

- In Memoriam

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Adjustment to a “new normal:” coping flexibility and mental health issues during the covid-19 pandemic.

- 1 Department of Psychology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

- 2 Department of Psychology, The University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

- 3 Modum Bad Psychiatric Hospital, Vikersund, Norway

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is an unprecedented health crisis in terms of the scope of its impact on well-being. The sudden need to navigate this “new normal” has compromised the mental health of many people. Coping flexibility, defined as the astute deployment of coping strategies to meet specific situational demands, is proposed as an adaptive quality during this period of upheaval. The present study investigated the associations between coping flexibility and two common mental health problems: COVID-19 anxiety and depression. The respondents were 481 Hong Kong adults (41% men; mean age = 45.09) who took part in a population-based telephone survey conducted from April to May 2020. Self-report data were assessed with the Coping Flexibility Interview Schedule, COVID-19-Related Perception and Anxiety Scale, and Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. Slightly more than half (52%) of the sample met the criteria for probable depression. Four types of COVID-19 anxiety were identified: anxiety over personal health, others' reactions, societal health, and economic problems. The results consistently revealed coping flexibility to be inversely associated with depression and all four types of COVID-19 anxiety. More importantly, there was a significant interaction between perceived likelihood of COVID-19 infection and coping flexibility on COVID-19 anxiety over personal health. These findings shed light on the beneficial role of coping flexibility in adjusting to the “new normal” amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

The emergence of an atypical coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, instigated a global outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 [COVID-19; e.g., ( 1 )]. Following identification of the earliest cases of COVID-19 in December 2019, the World Health Organization ( 2 ) declared the viral outbreak a health emergency of international concern on January 30, 2020, and then a global pandemic <2 months later. The escalating pandemic has induced anxiety and panic reactions in the general public, and the emotional responses bear some resemblance to those observed amid the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003 [e.g., ( 3 , 4 )]. For instance, the panic sell-off of stocks led to a plunge in the global stock market ( 5 ), and long lines for food and the irrational stockpiling of personal protection equipment such as facemasks and hand sanitizers have been widely seen ( 6 , 7 ).

Despite such resemblances, the COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented crisis in terms of the scope of its influence on both physical and mental health [e.g., ( 8 , 9 )]. To curb the transmission of this hitherto unknown virus, governments all over the world have enforced strict epidemic-control measures such as nationwide school closures, stay-at-home orders, and physical distancing regulations in public areas ( 10 ). Also, myriad public and private organizations have adopted teleworking policies mandating that their employees work from home ( 11 ). Although employees hold generally favorable attitudes toward home-based teleworking, the sudden drastic change in work mode left many unprepared ( 12 ). Previous research on the office-home transition has revealed major changes in the work environment to induce the most stress and anxiety in employees who feel the least prepared for this alternative work mode ( 13 ). Devastating problems arising from stressful life changes have been documented not only in adults but also in youngsters, with recent studies revealing a significant proportion of children and adolescents to have experienced psychological distress during the school-closure period ( 14 , 15 ). The COVID-19 pandemic has confronted people of all ages with fundamental life changes [e.g., ( 16 , 17 )].

To grapple with the “new normal” and deal with the considerable challenges brought about by the pandemic, individuals need a considerable degree of flexibility. Psychological resilience is a widely recognized mechanism underlying the adjustment process, with coping flexibility a core component [e.g., ( 18 )]. The theory of coping flexibility postulates that effective coping entails (a) sensitivity to the diverse situational demands embedded in an ever-changing environment and (b) variability in deploying coping strategies to meet specific demands ( 19 ). More specifically, psychological adjustment is a function of the extent to which individuals deploy problem-focused coping strategies (e.g., direct action) in controllable stressful situations and emotion-focused coping strategies (e.g., distraction) in uncontrollable ones. Inflexible coping, in contrast, has been linked to psychological symptoms. For example, individuals with heightened anxiety levels are characterized by an illusion of control [e.g., ( 20 , 21 )]. They tend to perceive all events in life as being under their control, and thus predominantly opt for problem-focused coping regardless of the situational characteristics. In contrast, individuals with depression are characterized by a sense of learned helplessness [e.g., ( 22 , 23 )]. They tend to view all events as beyond their control, and thus predominantly deploy emotion-focused coping across stressful events. Coping flexibility has been identified to foster adjustment to stressful life changes, which is indicated by a reduction in symptoms of anxiety and depression commonly experienced in stressful life transitions ( 24 ).

Applying these theories and findings to psychological adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals higher in coping flexibility are predicted to experience lower levels of anxiety and depression than those lower in coping flexibility. Clinical trial findings on COVID-19 offer a mixture of promise and disappointment regarding the efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates [e.g., ( 25 )], and the absence of a thorough understanding of the etiology and treatment of this atypical virus has elicited widespread public panic responses. According to the theory of psychological entropy ( 26 ), uncertainty is a crucial antecedent of anxiety. In accordance with that theory, studies conducted during the pandemic have revealed unusually high prevalence rates of mental health problems such as anxiety and depression, rates ~3-fold higher than both their pre-pandemic prevalence and lifetime prevalence over the past two decades ( 27 , 28 ).

In light of the transactional theory of stress and coping that highlights the importance of primary and secondary appraisals in the coping process ( 29 ), coping flexibility (secondary appraisal) is predicted to explain the association between context-specific health beliefs (primary appraisal) and mental health. Instead of perceiving the COVID-19 pandemic as aversive and uncontrollable, resilient copers tend to espouse a more complex view by recognizing both controllable and uncontrollable aspects of the pandemic. For instance, these individuals tend to take such positive actions as acquiring new information technology and digital skills to meet the demands of home-based teleworking, but engage in meditation to cope with the unpleasant emotions brought about by mandatory stay-at-home orders. Accordingly, coping flexibility is hypothesized to be inversely associated with anxiety and depression during the pandemic.

As individuals high in coping flexibility are characterized by cognitive astuteness in making distinctions in an array of stressful events ( 30 , 31 ), coping flexibility is also predicted to interact with context-specific health beliefs to have a conjoint influence on mental health in the pandemic context. Although COVID-19 shares similar characteristics with other atypical coronaviruses of SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), the case fatality rate of COVID-19 is much lower than the others ( 32 ). Among individuals high in coping flexibility, those who tend to perceive such differences may experience lower COVID-19 anxiety than their counterparts who do not hold this perception. In this respect, mental health experienced during the pandemic is a function of both context-specific health beliefs and coping flexibility.

The present study was conducted during the “second wave” of COVID-19 infections in Hong Kong. Although the first confirmed COVID-19 case was identified on January 23, 2020, with the first death recorded 2 weeks later ( 33 ), Hong Kong remained largely unscathed by the first wave, with only sporadic cases reported and a relatively flat epidemic curve (i.e., fewer than 100 confirmed cases). However, there was a sudden surge in confirmed cases in March, when the viral outbreak swept the globe ( 34 ). The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) responded to the health emergency by enacting a travel ban on non-residents, issuing compulsory quarantine orders for residents returning from overseas, and tightening various physical distancing measures in late March and early April [e.g., ( 35 , 36 )]. Special work arrangements for government employees were also implemented, and many organizations followed suit. The psychosocial impact was thus so pervasive that all sectors of society were affected. A population-based survey was therefore deemed the most appropriate method for investigating the psychological reactions to the pandemic among residents of Hong Kong. The method yields heterogeneous community samples, which maximizes representativeness and minimizes sampling errors.

Materials and Methods

Sample size determination and power analysis.

The statistical power analysis showed that the minimum sample size was 276 in order to identify statistically significant associations among the study variables, but a larger sample size was recruited to meet the requirements for conducting principal component analysis (PCA). Considering the general rule of thumb of having at least 50 cases per factor and a maximum number of nine factors to be identified in the PCA, the pre-planned minimum sample size was 450.

Participants and Procedures

The respondents were 481 Hong Kong adults (41% men; mean age = 45.09, SD = 23.42), who were recruited from a population-based telephone survey conducted by a survey research center at the first author's university. Random digit dialing was used for identifying eligible households, and then the most recent birth day method was employed to select a household member. To be eligible for participation, respondents had to be aged 18 or older, a resident of Hong Kong, able to understand Cantonese, and willing to give consent. Participation was voluntary, and all respondents who completed the survey were entered into a lucky draw for a chance to win gift certificates worth 500 Hong Kong dollars (about 65 U.S. dollars).

Trained interviewers conducted the telephone interviews using a structured questionnaire with standard questions. To foster interviewer calibration and minimize measurement bias, the survey was piloted in a small group of respondents from April 2 to 10, 2020. The final set of survey questions was amended to enhance the clarity of a few items, and then the full survey was administered from April 20 to May 19, 2020.

The study was conducted according to the ethical research standards of the American Psychological Association, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the human research ethics committee of the first author's university before the survey began (approval number: EA1912046 dated March 4, 2020). All respondents gave verbal consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Instruments

Coping flexibility.

Coping flexibility was assessed by the revised Coping Flexibility Interview Schedule ( 37 ). This interview schedule was originally developed based on clinical samples ( 38 ), and was adjusted for use with heterogeneous non-clinical populations. In the pilot phase, some respondents reported difficulty in understanding the terms of primary and secondary approach coping that was currently used in our interview schedule. The interview questions were revised by combining the terms of primary and secondary approach coping into problem-focused coping and converting the term of avoidant coping style into emotion-focused coping. Problem-focused and emotion-focused coping were originally used in the transactional theory of coping ( 39 ) from which the Coping Flexibility Interview Schedule was derived. The respondents were asked to report their deployment of problem-focused (e.g., information seeking, monitoring) and emotion-focused (e.g., acceptance, relaxation) coping in controllable and uncontrollable stressful situations over the past month.

To obtain a composite score of coping flexibility indicating strategy-situation fit, the individual coping items were subsequently coded by two independent raters according to a coding scheme ( 40 , 41 ) based on coping theories ( 39 , 42 ). One point was given to the deployment of problem-focused coping strategies to handle controllable stressful events and/or the deployment of emotion-focused coping strategies to handle uncontrollable stressful events. Zero points were given otherwise. All of these scores were aggregated, and then averaged to obtain a composite score. Inter-rater agreement was evaluated using Krippendorff alpha coefficients ( 43 ), and the results showed no discrepancies because no subjective codings were required (Krippendorff alpha = 100%).

COVID-19-Related Perceptions

Both perceived likelihood and impact of COVID-19 infection were measured by a modified measure developed and validated during the SARS outbreak ( 44 ). To make this measure relevant to the present pandemic context, the context was altered from “SARS outbreak” to “COVID-19 pandemic.” Respondents gave four-point ratings to indicate their perception of the likelihood of contracting COVID-19 (1 = very unlikely , 4 = very likely ) and the impact of having it (1 = no impact at all , 4 = a large impact ). The measure has been found to display both criterion and predictive validity ( 44 , 45 ).

COVID-19 Anxiety

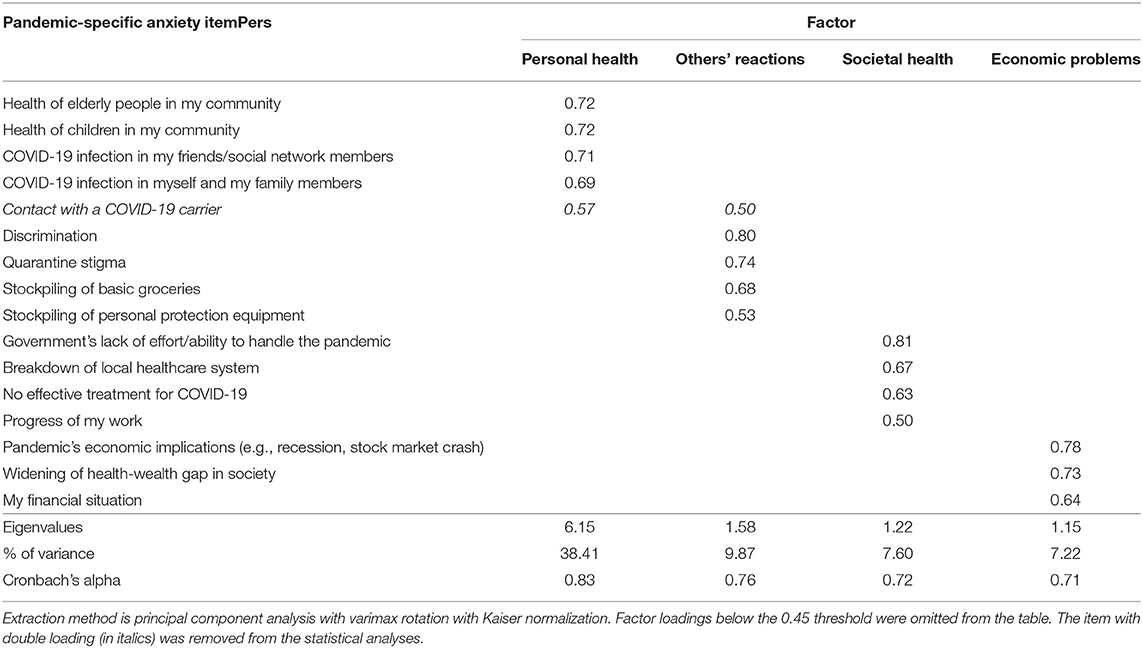

As the events that have occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic are unprecedented, our team conducted a qualitative study in March 2020 asking participants to list all of the issues that had made them feel anxious during the pandemic. Content analysis of the results revealed 16 distinct themes regarding anxiety-provoking issues experienced amid the pandemic (see Table 1 for details). These items were compiled into a context-specific measure for assessing COVID-19 anxiety. Respondents rated each item on a scale ranging from 1 ( not worried at all ) to 4 ( very worried ).

Table 1 . Four-factor promax-rotated factor solution for COVID-19 anxiety ( n = 481).

Depression was measured by the short form of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale ( 46 ), which contains 10 items. The translated Chinese version was used in this study ( 47 ). Respondents rated each item on a four-point scale (0 = rarely or none of the time , 3 = most or all of the time ). In this study, we applied the recommended cut-off score of 10 as the classification scheme [e.g., ( 46 , 48 )].

Statistical Analysis

All statistical procedures were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 for Windows (IBM Corporation, 2019, Armonk, NY). Before hypothesis testing, PCA was performed to identify the factorial structure underlying the 16 anxiety-provoking issues. The components were rotated using the varimax method with Kaiser normalization to increase the interpretability of the findings. The number of factors extracted was determined by the Kaiser rule, with factors retained when the eigenvalue exceeded one. The total amount of variance accounted for by the factors needed to exceed 60%, a minimum criterion for factor selection widely adopted in PCA research ( 49 ). Both the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett's test of sphericity were first examined to check the appropriateness for analyzing the dataset, with appropriateness indicated if the KMO index was >0.50 and the test of sphericity was significant. For PCA, items with a factor loading <0.45 or double loading were removed. Cronbach alpha was used to indicate internal consistency for the items within each factor, with an alpha >0.70 considered adequate.

The potential differences among demographic groups were examined. Differences in sex were detected using an independent-samples t -test, and age differences using Pearson zero-order correlation analysis. In addition to testing age as a continuous variable, we also adopted a generational approach proposed by the Pew Research Center that makes comparisons across four age cohorts: (a) Millennials, who were born in 1981 or after; (b) Generation X-ers, who were born between 1965 and 1980; (c) Baby Boomers, who were born between 1946 and 1964; and (d) Silent Gen'ers, who were born before 1946 ( 50 ). A general linear model (GLM) was employed to investigate the differences among the four generations, with post hoc Bonferroni tests conducted if generational differences were found in any of the study variables.

Pearson zero-order correlation analysis was conducted to obtain an overview of the inter-relationships among the study variables. The hypothesized beneficial role of coping flexibility on mental health was then tested using three-step hierarchical regression analysis. First, the two demographic variables (i.e., sex and age) were entered to control for their potential effects on the criterion in question. Second, the variables of perceived likelihood of COVID-19 infection, perceived impact of COVID-19 infection, and coping flexibility were entered simultaneously. Third, the Perceived Likelihood of COVID-19 Infection × Coping Flexibility interaction and the Perceived Impact of COVID-19 Infection × Coping Flexibility interaction were entered. To address the potential multicollinearity problem, all of the variables were centered before conducting these analyses. The procedures were identical for each mental health problem included as the criterion variable. To unpack significant interaction effects, post hoc simple effects analysis was employed to examine the effects of COVID-19-related perception on a criterion at each level of coping flexibility.

PCA was performed because the KMO index was high (.87) and Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant (χ 2 = 3379.31, p < 0.0001). The results with the principal component weights of the 16 anxiety-provoking issues are presented in Table 1 . A four-factor solution was yielded, accounting for 63% of the total variance, with 38% explained by the first factor, personal health issues (e.g., “ COVID-19 infection in myself and my family members ”); 10% by the second factor, other people's undesirable reactions (e.g., “ discrimination ”); 8% by the third factor, societal health issues (e.g., “ government's lack of effort/ability to handle the pandemic ”); and 7% by the fourth factor, economic problems (e.g., “ pandemic's economic implications ”). It is noteworthy that one item (i.e., “ contact with a COVID-19 carrier ”) had a double loading with a difference of <0.10, and was thus discarded. All four factors displayed internal consistency (Cronbach alphas > 0.70), and were thus included in the subsequent analyses as indicators of COVID-19 anxiety.

The GLM results revealed a significant cross-generational difference only for anxiety over societal health, F (3, 477) = 33.92, p < 0.0001, partial eta squared = 0.18. Post hoc Bonferroni tests indicated that Silent Gen'ers aged over 74 ( M = 2.02, SD = 0.62) reported significantly less anxiety over societal health than did Millennials aged 18–39 ( M = 2.87, SD = 0.66) or Generation X-ers aged 40–55 ( M = 2.71, SD = 0.68), p s < 0.0001. However, there were no other differences regarding sex, generation, or the Sex × Generation interaction, p s > 0.05.

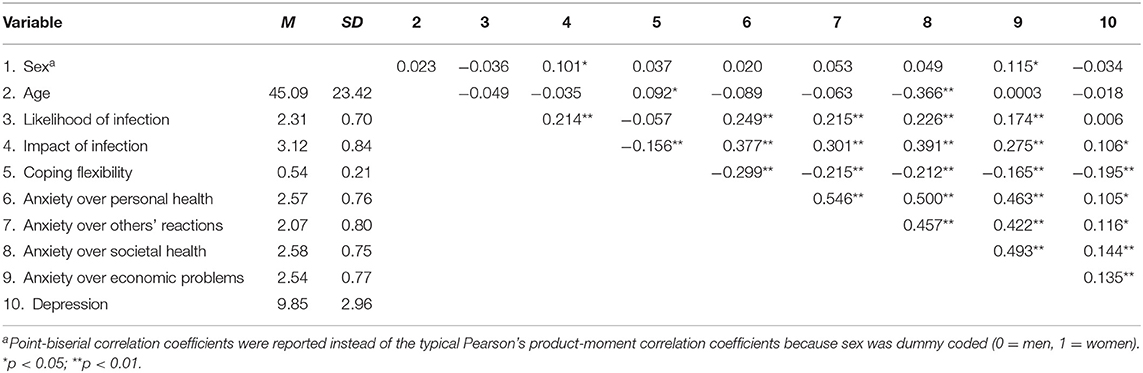

The descriptive statistics of and inter-relationships among the study variables are presented in Table 2 . The average depression score was 9.85, which was very close to the cut-off score for probable depression. Adopting the standard cut-off criterion of 10, slightly more than half (52%) of the respondents were categorized as having probable depression. The probable depression group ( M = 2.67, SD = 0.75) generally experienced a higher anxiety level over societal health issues than the no depression group ( M = 2.48, SD = 0.73), t = 2.72, p = 0.007. In addition, the probable depression group ( M = 0.50, SD = 0.21) also reported a generally lower degree of coping flexibility than the no depression group ( M = 0.58, SD = 0.21), t (479) = −3.95, p < 0.0001. However, no other significant differences in depression level were found for sex or generation, p s > 0.21.

Table 2 . Descriptive statistics of study variables ( n = 481).

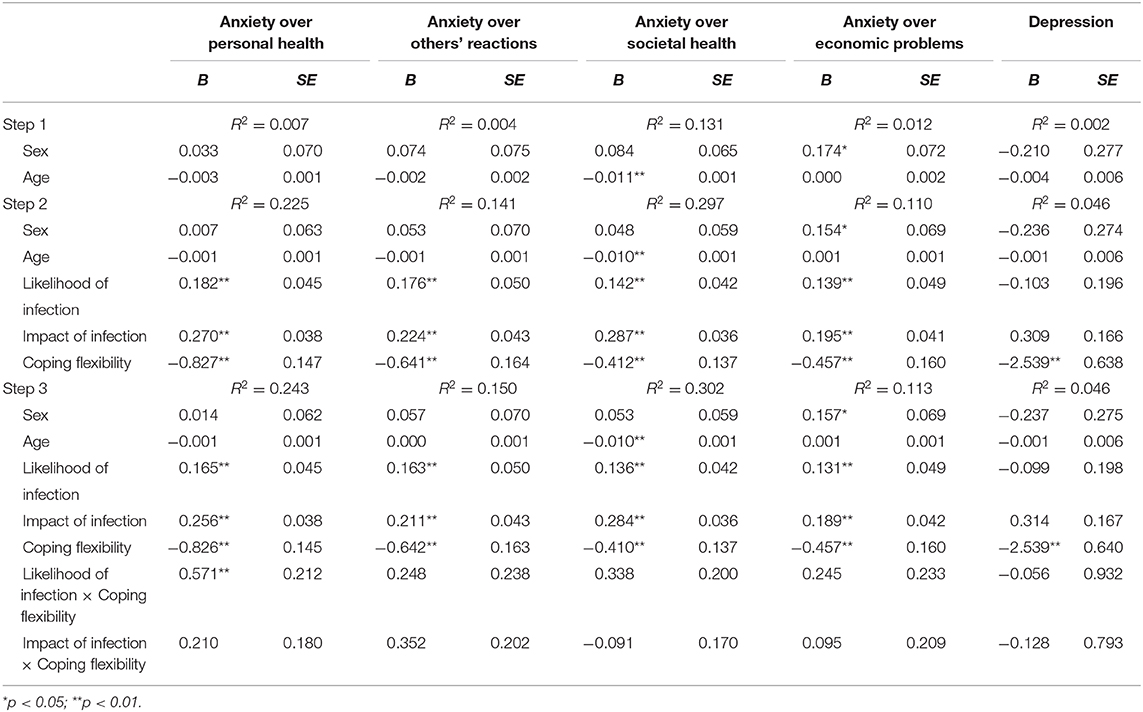

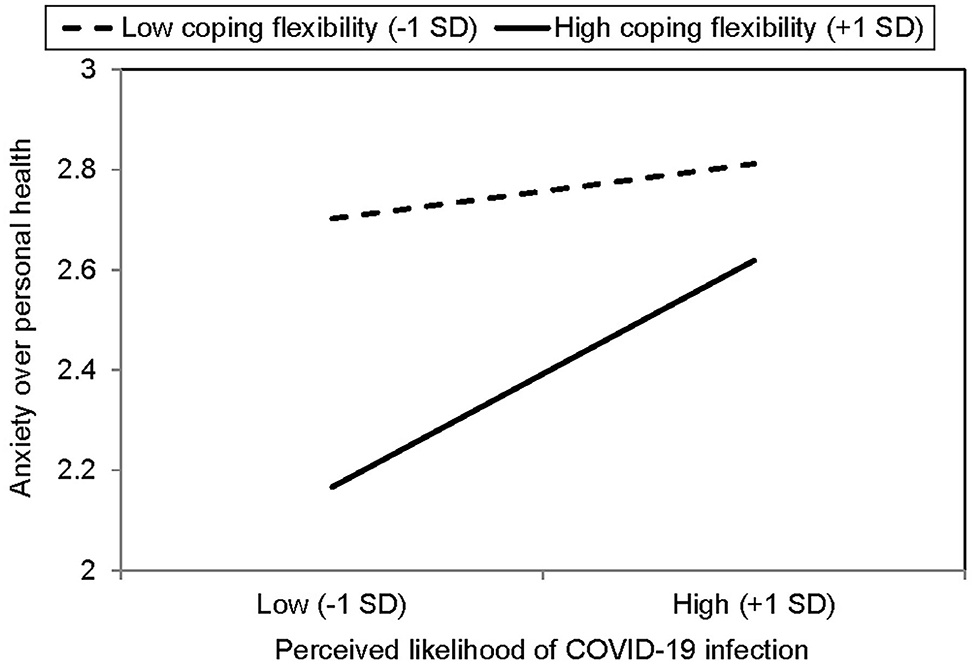

Table 3 summarizes the results of hierarchical regression analysis for various mental health problems. As shown in the table, the pattern of results was highly consistent across the four types of COVID-19 anxiety; that is, all four types were positively associated with both the perceived likelihood and impact of COVID-19 infection and inversely associated with coping flexibility. There was also a significant interaction between perceived likelihood of COVID-19 infection and coping flexibility, and the results are presented in Figure 1 . For individuals higher in coping flexibility, those who perceived a lower likelihood of contracting COVID-19 reported less anxiety over their own health than their counterparts who perceived a greater likelihood of such contraction. For individuals lower in coping flexibility, however, such individual differences were absent and they generally reported greater anxiety over their own health than those higher in coping flexibility. In addition, the results revealed depression to also be inversely associated with coping flexibility, although its associations with the two types of COVID-19-related perception were non-significant. In short, these findings provide support for the hypothesized beneficial role of coping flexibility in dealing with mental health issues experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 3 . Summary of hierarchical regression analysis by mental health problems ( n = 481).

Figure 1 . Simple effects analysis for significant interaction between perceived likelihood of COVID-19 infection and coping flexibility ( n = 481).

In addition to evaluating strategy-situation fit using composite coping flexibility scores, nuanced analysis was conducted to further examine the deployment of individual coping strategies and their associations with mental health problems. Most of the respondents (61%) reported deploying problem-focused coping to handle controllable stressful events during the pandemic, whereas just under half (45%) reported deploying that strategy to deal with uncontrollable stressful events. Fewer respondents said they had used emotion-focused coping to deal with controllable and uncontrollable stressful events (39 and 37%, respectively). Moreover, the deployment of problem-focused coping in controllable stressful events was inversely associated with anxiety over personal health and others' reactions, p s <0.0001, whereas the deployment of emotion-focused coping in controllable stressful events was positively associated with all four types of COVID-19 anxiety and depression, p s < 0.0001. However, neither problem-focused nor emotion-focused coping deployed in uncontrollable stressful events were significantly associated with any of the mental health problems, p s > 0.14.

The present study has investigated coping responses and mental health issues among the general public in Hong Kong amid the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent studies have identified high prevalence rates of anxiety and depression among residents of COVID-19-affected regions all over the world [e.g., ( 28 , 51 )]. Our study expands this growing body of research by specifying four major factors of COVID-19 anxiety: personal health, others' reactions, societal health, and economic problems. Although the third factor is characterized primarily by societal health issues, it is interesting to note that a seemingly unrelated item “ progress of my work ” also loaded onto this factor. This perplexing finding may reflect the fact that employees' work progress has been affected more by societal factors (e.g., implementation of prevention and control disease regulations for business and premises, home-based teleworking policy) than personal factors during the pandemic.

A similar phenomenon is found for the fourth factor, economic problems. Most of the items loading onto it involved broad societal issues (e.g., economic recession, widening of health-wealth gap), but an item related to personal financial problems also did so. This finding similarly indicates that individuals' personal financial condition during the pandemic may be influenced to a great extent by the wider economy. Taken together, these interesting findings reflect the intricate interactions between the individual and society in times of crisis, thus attesting to the necessity of identifying anxiety-provoking issues specific to the pandemic in addition to assessing generic mental health issues that are context-free.

In addition to anxiety, our findings also show depression to have been prevalent among Hong Kong adults during the second wave of the pandemic, with slightly more than half the sample identified as having probable depression. Compared with respondents without depression, those with probable depression tended to experience greater anxiety related to societal health issues but not economic problems or personal health issues. These findings indicate that the unusually high prevalence of depression reported during the pandemic is largely related to health-related problems at the societal level (e.g., governmental actions to combat COVID-19, possible breakdown of local healthcare system) rather than personal health issues.

More importantly, the present study is the first to apply the theory of coping flexibility to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the findings provide support for the hypothesized beneficial role of coping flexibility in relieving heightened anxiety and depression when handling the vicissitudes emerged during the pandemic. Astute strategy deployment to meet the specific demands of an ever-changing environment is essential for adjustment to the “new normal,” and a better strategy-situation fit is found to be inversely associated with both COVID-19 anxiety and depression. It is noteworthy that coping flexibility interacts with perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 infection to have a conjoint influence on COVID-19 anxiety. Even within individuals having a higher level of coping flexibility, those tend to experience fewer symptoms of COVID-19 anxiety over personal health if they display cognitive astuteness in assessing their possibility of contracting COVID-19. These novel findings provide support for the notion that the anxiety-buffering role of coping flexibility is highly context-specific ( 24 ), which is confined to infection susceptibility and anxiety over personal health in this stressful encounter. Such context-specificity is not surprising because subjective appraisals of the possibility of contracting a novel virus should be directly linked with concerns over personal health rather than other anxiety-provoking events related to non-health issues or to the society at large. Moreover, these findings further demonstrate that COVID-19 anxiety is not a unidimensional construct and should thus be studied using a multidimensional approach.

We further found the use of problem-focused coping to deal with controllable stressful events to be related to lower levels of anxiety over personal issues (i.e., personal health and others' reactions) rather than broader societal issues (i.e., societal health, economic problems). It is also noteworthy that the use of emotion-focused coping to handle controllable rather than uncontrollable stressful events was related to higher COVID-19 anxiety and depression, a finding consistent with previous studies on clinical samples of depression ( 22 ). Although the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic is objectively an uncontrollable stressor due to its uncertain nature, the theory of coping flexibility highlights the importance of identifying aspects of life that are controllable and distinguishing these aspects from most other uncontrollable ones in a stressful encounter. For example, when a person high in coping flexibility fails to buy facemasks after visiting many stores, this person still regards the problem as controllable and keeps trying a variety of alternative means (e.g., placing orders in overseas online stores, seeking advice from members of WhatsApp groups). It is the cognitive astuteness in distinguishing between controllable and uncontrollable life aspects that fosters adjustment to stressful life changes.

Such situational differences in coping effectiveness indicate that neither problem-focused nor emotion-focused coping is inherently adaptive or maladaptive. The role of effective coping in mitigating mental health problems depends largely on the extent to which a deployed strategy meets the specific demands of the stressful encounter concerned. For instance, playing online games or browsing social network sites can be stress-relieving during leisure time ( 52 , 53 ), but prolonged gameplay or social media use can impair work or academic performance while working or studying from home ( 54 ). These findings are in line with the theory of coping flexibility, highlighting the beneficial role of flexible coping in soothing mental health problems experienced during the pandemic.

The present findings also have practical implications. Given the beneficial role of coping flexibility, clinicians may work with clients to enhance coping effectiveness with regard to strategy-situation fit. Stress management intervention may involve sharpening clients' skills for (a) distinguishing the key demands stemming from an array of stressful events; (b) assessing whether or not such demands are amendable to a change in effort (i.e., controllable or uncontrollable); (c) applying the meta-cognitive skill of reflection to evaluate strategies that best match the specific demands of diverse stressful situations; and (d) subsequently deploying the most appropriate strategy to handle each stressor. Such flexible coping skills are especially useful for dealing with the psychological distress elicited by a pandemic involving an assortment of stressful events.

Coping flexibility may also be valuable at a broader level because the unpredictable progression of the COVID-19 pandemic across successive waves presents varying challenges for public health authorities worldwide. For instance, the shortage of personal protection equipment aroused immense public anxiety in Hong Kong during the first wave owing to the sudden surge in demand for facemasks and hand sanitizer. After the supply of such equipment had been stabilized, however, new societal problems emerged. For example, during the second wave, public commitment to observing physical distancing measures began to wane owing to “pandemic fatigue” ( 55 ). Public health authorities may need to adopt a certain degree of flexibility in monitoring and identifying emerging issues to allow the timely adjustment of extant disease-control measures or the formulation of new ones to mitigate changing public health threats.

Despite its important findings, several study limitations must be noted. The survey was conducted during the second wave of the pandemic, when the epidemic curve climbed to a high level and then leveled off for a few months before reaching a further peak in the third wave in July and August, 2020 ( 34 ). As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to evolve in an unpredictable manner, some of the anxiety-provoking issues identified in this study may no longer elicit anxiety to the same extent in future waves. The list of issues eliciting COVID-19 anxiety should thus be updated in future research. Given the time sensitivity of these issues, pilot testing is essential to evaluate their relevance in particular phases of the pandemic.

Further, although our findings offer robust support for the hypothesized beneficial role of coping flexibility amid the pandemic, previous meta-analysis indicated that that beneficial role is more prominent in collectivist than individualist regions ( 19 ). A fruitful direction for future research would thus be to replicate the present design in individualist countries, allowing cross-cultural comparisons to be made. In addition to cultural differences, there may also be considerable variations among Chinese adults residing in different regions, as the epidemic trajectory has varied greatly among cities in the Greater Bay Area, such as Guangzhou and Macau ( 56 ). Greater effort can be made to compare the prevalence of psychological disorders and coping processes among Chinese residents of diverse regions.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong (approval number: EA1912046 dated March 4, 2020). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

CC contributed to project design and administration, coordinated the data collection, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. H-yW contributed to project design, survey creation, statistical analysis, and data interpretation. OE contributed to data interpretation and writing parts of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research project was funded by the Public Policy Research Funding Scheme from the Policy Innovation and Co-ordination Office (Project Number: SR2020.A8.019) and General Research Fund (Project Number: 17400714) of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The funders had no role in study design and administration, statistical analysis or interpretation, manuscript writing, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Sylvia Lam, Sophie Lau, Janice Leung, Yin-wai Li, Stephanie So, Yvonne Tsui, and Kylie Wong for research and clerical assistance.

1. Lai C, Shih T, Ko W, Tang H, Hsueh P. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. (2020) 55:105924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. World Health Organization. Timeline: WHO's COVID-19 Response . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline (accessed October 8, 2020).

Google Scholar

3. Chen R, Chou K, Huang Y, Wang T, Liu S, Ho L. Effects of a SARS prevention programme in Taiwan on nursing staff's anxiety, depression and sleep quality: a longitudinal survey. Int J Nurs Stud. (2006) 43:215–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.03.006

4. Cheng C, Tang CS. The psychology behind the masks: psychological responses to the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in different regions. Asian J Soc Psychol. (2004) 7:3–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2004.00130.x

5. Baker SR, Bloom N, Davis SJ, Kost K, Sammon M, Viratyosin T. The unprecedented stock market reaction to COVID-19. Rev Asset Pricing Studies. (2020) raaa008. doi: 10.3386/w26945

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Arafat SY, Kar SK, Marthoenis M, Sharma P, Apu EH, Kabir R. Psychological underpinning of panic buying during pandemic (COVID-19). Psychiatry Res. (2020) 289:113061. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113061

7. Wong JEL, Leo YS, Tan CC. COVID-19 in Singapore—current experience: critical global issues that require attention and action. JAMA. (2020) 323:1243–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2467

8. Bressington DT, Cheung TCC, Lam SC, Suen LKP, Fong TKH, Ho HSW. Association between depression, health beliefs, and face mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:1075. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.571179

9. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729

10. Gostin LO, Wiley LF. Governmental public health powers during the COVID-19 pandemic: stay-at-home orders, business closures, and travel restrictions. JAMA. (2020) 323:2137–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5460

11. Belzunegui-Eraso A, Erro-Garcés A. Teleworking in the context of the Covid-19 crisis. Sustainability. (2020) 12:3662. doi: 10.3390/su12093662

12. Persol Research and Development. Survey of Telework in Japan for COVID-19 . Nagoya: Author (2020).

13. Harris L. Home-based teleworking and the employment relationship: managerial challenges and dilemmas. Pers Rev. (2003) 32:422–37. doi: 10.1108/00483480310477515

14. Tang S, Xiang M, Cheung T, Xiang Y. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: the importance of parent-child discussion. J Affect Disord. (2021) 279:353–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.016

15. Zhang Z, Zhai A, Yang M, Zhang J, Zhou H, Yang C. Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms of high school students in shandong province during the COVID-19 epidemic. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:1499. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.570096

16. Voitsidis P, Gliatas I, Bairachtari V, Papadopoulou K, Papageorgiou G, Parlapani E. Insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic in a greek population. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 289:113076. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113076

17. Cheng C, Ebrahimi OV, Lau Y. Maladaptive coping with the infodemic and sleep disturbance in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Sleep Res. (2020) e13235. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13235

18. Lam CB, McBride-Chang CA. Resilience in young adulthood: the moderating influences of gender-related personality traits and coping flexibility. Sex Roles. (2007) 56:159–72. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9159-z

19. Cheng C, Lau HB, Chan MS. Coping flexibility and psychological adjustment to stressful life changes: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. (2014) 140:1582–607. doi: 10.1037/a0037913

20. Cheng C, Hui W, Lam S. Psychosocial factors and perceived severity of functional dyspeptic symptoms: a psychosocial interactionist model. Psychosom Med. (2004) 66:85–91. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000106885.40753.C1

21. Sanderson WC, Rapee RM, Barlow DH. The influence of an illusion of control on panic attacks induced via inhalation of 5.5% carbon dioxide-enriched air. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1989) 46:157–162. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810020059010

22. Gan Y, Zhang Y, Wang X, Wang S, Shen X. The coping flexibility of neurasthenia and depressive patients. Pers Individ Differ. (2006) 40:859–71. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.09.006

23. Zong J, Cao XY, Cao Y, Shi YF, Wang YN, Yan C, et al. Coping flexibility in college students with depressive symptoms. Health Quality Life Outcomes. (2010) 8:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-66

24. Cheng C, Chau C. When to approach and when to avoid? Funct Flex Key Psychol Inquiry. (2019) 30:125–9. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2019.1646040

25. Jean S, Lee P, Hsueh P. Treatment options for COVID-19: The reality and challenges. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. (2020) 53:436–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.034

26. Hirsh JB, Mar RA, Peterson JB. Psychological entropy: a framework for understanding uncertainty-related anxiety. Psychol Rev. (2012) 119:304–20. doi: 10.1037/a0026767

27. Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US Adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. (2020) 3:e2019686. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686

28. Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LM, Gill H, Phan L. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. (2020) 277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

29. Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen RJ. The dynamics of a stressful encounter. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Motivational Science: Social and Personality Perspectives . New York, NY: Psychology Press (2000). p. 111–27.

30. Cheng C. Dialectical thinking and coping flexibility: a multimethod approach. J Pers. (2009) 77:471–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00555.x

31. Cheng C, Chiu C, Hong Y, Cheung JS. Discriminative facility and its role in the perceived quality of interactional experiences. J Pers. (2001) 69:765–86. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.695163

32. Petrosillo N, Viceconte G, Ergonul O, Ippolito G, Petersen E. COVID-19, SARS and MERS: are they closely related? Clin Microbiol Infect. (2020) 26:729–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.026

33. Centre for Health Protection. Number of Notifiable Infectious Diseases by Month in 2020 . (2020). Available onlone at: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/statistics/data/10/26/43/6896.html (accessed October 8, 2020).

34. Statista. Number of Novel Coronavirus COVID-19 Cumulative Confirmed, Recovered and Death Cases in Hong Kong from January 30 to October 25, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1105425/hong-kong-novel-coronavirus-covid19-confirmed-death-recovered-trend/ (accessed October 28, 2020).

35. The HKSAR and Government (2020). Government Announces Enhancements to Anti-Epidemic Measures in Four Aspects . Available online at: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202003/24/P2020032400050.htm (accessed October 8, 2020).

36. news.gov.hk. Restrictions on Bars Gazetted . (2020). Available online at: https://www.news.gov.hk/eng/2020/04/20200402/20200402_195740_071.html (accessed October 8, 2020).

37. Atal S, Cheng C. Socioeconomic health disparities revisited: coping flexibility enhances health-related quality of life for individuals low in socioeconomic status. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2016) 14:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0410-1

38. Cheng C, Hui W, Lam S. Perceptual style and behavioral pattern of individuals with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Health Psychol. (2000) 19:146–54. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.2.146

39. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. The concept of coping. In: Monat A, Lazarus RS, editors. Stress and Coping: An Anthology . New York, NY: Columbia University (1991). p. 189–206

40. Cheng C, Chan NY, Chio JHM, Chan P, Chan AOO, Hui WM. Being active or flexible? Role of control coping on quality of life among patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Psychooncology. (2012) 21:211–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.1892

41. Cheng C, Cheng F, Atal S, Sarwono S. Testing of a dual process model to resolve the socioeconomic health disparities: a tale of two Asian countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:717. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020717

42. Endler NS. Stress, anxiety and coping: the multidimensional interaction model. Can Psychol. (1997) 38:136–53. doi: 10.1037/0708-5591.38.3.136

43. Hayes AF, Krippendorff K. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Commun Methods Meas. (2007) 1:77–89. doi: 10.1080/19312450709336664

44. Cheng C, Ng A. Psychosocial factors predicting SARS-preventive behaviors in four major SARS-affected regions. J Appl Soc Psychol. (2006) 36:222–47. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00059.x

45. Cheng C, Cheung MWL. Psychological responses to outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome: a prospective, multiple time-point study. J Pers. (2005) 73:261–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00310.x

46. Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am J Prev Med. (1994) 10:77–84. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6

47. Yang CF. Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes , Vol. 1. Taipei: Yuan-Liou (1997).

48. Boey KW. Cross-validation of a short form of the CES-D in Chinese elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (1999) 14:608–17. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199908)14:8<608::AID-GPS991>3.0.CO;2-Z

49. Bagozzi RP, Youjae Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci. (1988) 16:74–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02723327

50. Wang H, Cheng C. New perspectives on the prevalence and associated factors of gaming disorder in Hong Kong community adults: a generational approach. Comput Hum Behav. (2021) 114:106574. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106574

51. Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health. (2020) 16:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

52. Kardefelt-Winther D. The moderating role of psychosocial well-being on the relationship between escapism and excessive online gaming. Comput Hum Behav. (2014) 38:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.020

53. Young NL, Daria JK, Mark DG, Christina JH. Passive Facebook use, Facebook addiction, and associations with escapism: an experimental vignette study. Comput Hum Behavi. (2017) 71:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.039

54. Cheng C, Lau Y, Luk JW. Social capital–accrual, escape-from-self, and time-displacement effects of internet use during the COVID-19 stay-at-home period: prospective, quantitative survey study. J Med Int Res. (2020) 22:e22740. doi: 10.2196/22740

55. Harvey N. Behavioural fatigue: real phenomenon, naïve construct, or policy contrivance. Front Psychol. (2021) 11:2960. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.589892

56. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases . (2021). Available online at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed January 18, 2021).

Keywords: coronavirus disease, resilience, coping, stress, psychological well-being, adaptation, Chinese, epidemic

Citation: Cheng C, Wang H-y and Ebrahimi OV (2021) Adjustment to a “New Normal:” Coping Flexibility and Mental Health Issues During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 12:626197. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.626197

Received: 05 November 2020; Accepted: 01 March 2021; Published: 19 March 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Cheng, Wang and Ebrahimi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cecilia Cheng, ceci-cheng@hku.hk

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- COVID-19 and your mental health

Worries and anxiety about COVID-19 can be overwhelming. Learn ways to cope as COVID-19 spreads.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, life for many people changed very quickly. Worry and concern were natural partners of all that change — getting used to new routines, loneliness and financial pressure, among other issues. Information overload, rumor and misinformation didn't help.

Worldwide surveys done in 2020 and 2021 found higher than typical levels of stress, insomnia, anxiety and depression. By 2022, levels had lowered but were still higher than before 2020.

Though feelings of distress about COVID-19 may come and go, they are still an issue for many people. You aren't alone if you feel distress due to COVID-19. And you're not alone if you've coped with the stress in less than healthy ways, such as substance use.

But healthier self-care choices can help you cope with COVID-19 or any other challenge you may face.

And knowing when to get help can be the most essential self-care action of all.

Recognize what's typical and what's not

Stress and worry are common during a crisis. But something like the COVID-19 pandemic can push people beyond their ability to cope.

In surveys, the most common symptoms reported were trouble sleeping and feeling anxiety or nervous. The number of people noting those symptoms went up and down in surveys given over time. Depression and loneliness were less common than nervousness or sleep problems, but more consistent across surveys given over time. Among adults, use of drugs, alcohol and other intoxicating substances has increased over time as well.

The first step is to notice how often you feel helpless, sad, angry, irritable, hopeless, anxious or afraid. Some people may feel numb.

Keep track of how often you have trouble focusing on daily tasks or doing routine chores. Are there things that you used to enjoy doing that you stopped doing because of how you feel? Note any big changes in appetite, any substance use, body aches and pains, and problems with sleep.

These feelings may come and go over time. But if these feelings don't go away or make it hard to do your daily tasks, it's time to ask for help.

Get help when you need it

If you're feeling suicidal or thinking of hurting yourself, seek help.

- Contact your healthcare professional or a mental health professional.

- Contact a suicide hotline. In the U.S., call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline , available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Or use the Lifeline Chat . Services are free and confidential.

If you are worried about yourself or someone else, contact your healthcare professional or mental health professional. Some may be able to see you in person or talk over the phone or online.

You also can reach out to a friend or loved one. Someone in your faith community also could help.

And you may be able to get counseling or a mental health appointment through an employer's employee assistance program.

Another option is information and treatment options from groups such as:

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Self-care tips

Some people may use unhealthy ways to cope with anxiety around COVID-19. These unhealthy choices may include things such as misuse of medicines or legal drugs and use of illegal drugs. Unhealthy coping choices also can be things such as sleeping too much or too little, or overeating. It also can include avoiding other people and focusing on only one soothing thing, such as work, television or gaming.

Unhealthy coping methods can worsen mental and physical health. And that is particularly true if you're trying to manage or recover from COVID-19.

Self-care actions can help you restore a healthy balance in your life. They can lessen everyday stress or significant anxiety linked to events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Self-care actions give your body and mind a chance to heal from the problems long-term stress can cause.

Take care of your body

Healthy self-care tips start with the basics. Give your body what it needs and avoid what it doesn't need. Some tips are:

- Get the right amount of sleep for you. A regular sleep schedule, when you go to bed and get up at similar times each day, can help avoid sleep problems.

- Move your body. Regular physical activity and exercise can help reduce anxiety and improve mood. Any activity you can do regularly is a good choice. That may be a scheduled workout, a walk or even dancing to your favorite music.

- Choose healthy food and drinks. Foods that are high in nutrients, such as protein, vitamins and minerals are healthy choices. Avoid food or drink with added sugar, fat or salt.

- Avoid tobacco, alcohol and drugs. If you smoke tobacco or if you vape, you're already at higher risk of lung disease. Because COVID-19 affects the lungs, your risk increases even more. Using alcohol to manage how you feel can make matters worse and reduce your coping skills. Avoid taking illegal drugs or misusing prescriptions to manage your feelings.

Take care of your mind

Healthy coping actions for your brain start with deciding how much news and social media is right for you. Staying informed, especially during a pandemic, helps you make the best choices but do it carefully.

Set aside a specific amount of time to find information in the news or on social media, stay limited to that time, and choose reliable sources. For example, give yourself up to 20 or 30 minutes a day of news and social media. That amount keeps people informed but not overwhelmed.

For COVID-19, consider reliable health sources. Examples are the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Other healthy self-care tips are:

- Relax and recharge. Many people benefit from relaxation exercises such as mindfulness, deep breathing, meditation and yoga. Find an activity that helps you relax and try to do it every day at least for a short time. Fitting time in for hobbies or activities you enjoy can help manage feelings of stress too.

- Stick to your health routine. If you see a healthcare professional for mental health services, keep up with your appointments. And stay up to date with all your wellness tests and screenings.

- Stay in touch and connect with others. Family, friends and your community are part of a healthy mental outlook. Together, you form a healthy support network for concerns or challenges. Social interactions, over time, are linked to a healthier and longer life.

Avoid stigma and discrimination

Stigma can make people feel isolated and even abandoned. They may feel sad, hurt and angry when people in their community avoid them for fear of getting COVID-19. People who have experienced stigma related to COVID-19 include people of Asian descent, health care workers and people with COVID-19.

Treating people differently because of their medical condition, called medical discrimination, isn't new to the COVID-19 pandemic. Stigma has long been a problem for people with various conditions such as Hansen's disease (leprosy), HIV, diabetes and many mental illnesses.

People who experience stigma may be left out or shunned, treated differently, or denied job and school options. They also may be targets of verbal, emotional and physical abuse.

Communication can help end stigma or discrimination. You can address stigma when you:

- Get to know people as more than just an illness. Using respectful language can go a long way toward making people comfortable talking about a health issue.

- Get the facts about COVID-19 or other medical issues from reputable sources such as the CDC and WHO.

- Speak up if you hear or see myths about an illness or people with an illness.

COVID-19 and health

The virus that causes COVID-19 is still a concern for many people. By recognizing when to get help and taking time for your health, life challenges such as COVID-19 can be managed.

- Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. National Institutes of Health. https://covid19.nih.gov/covid-19-topics/mental-health. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Mental Health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic's impact: Scientific brief, 2 March 2022. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Mental health and the pandemic: What U.S. surveys have found. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/03/02/mental-health-and-the-pandemic-what-u-s-surveys-have-found/. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Taking care of your emotional health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coping/selfcare.asp. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- #HealthyAtHome—Mental health. World Health Organization. www.who.int/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome/healthyathome---mental-health. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Coping with stress. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/stress-coping/cope-with-stress/. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Manage stress. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/myhealthfinder/topics/health-conditions/heart-health/manage-stress. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- COVID-19 and substance abuse. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/covid-19-substance-use#health-outcomes. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- COVID-19 resource and information guide. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/NAMI-HelpLine/COVID-19-Information-and-Resources/COVID-19-Resource-and-Information-Guide. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Negative coping and PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/gethelp/negative_coping.asp. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Health effects of cigarette smoking. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm#respiratory. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- People with certain medical conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Your healthiest self: Emotional wellness toolkit. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/health-information/emotional-wellness-toolkit. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- World leprosy day: Bust the myths, learn the facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/leprosy/world-leprosy-day/. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- HIV stigma and discrimination. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/hiv-stigma/. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Diabetes stigma: Learn about it, recognize it, reduce it. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/features/diabetes_stigma.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Phelan SM, et al. Patient and health care professional perspectives on stigma in integrated behavioral health: Barriers and recommendations. Annals of Family Medicine. 2023; doi:10.1370/afm.2924.

- Stigma reduction. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/od2a/case-studies/stigma-reduction.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Nyblade L, et al. Stigma in health facilities: Why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Medicine. 2019; doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1256-2.

- Combating bias and stigma related to COVID-19. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19-bias. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Yashadhana A, et al. Pandemic-related racial discrimination and its health impact among non-Indigenous racially minoritized peoples in high-income contexts: A systematic review. Health Promotion International. 2021; doi:10.1093/heapro/daab144.

- Sawchuk CN (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. March 25, 2024.

Products and Services

- A Book: Endemic - A Post-Pandemic Playbook

- Begin Exploring Women's Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Future Care

- Antibiotics: Are you misusing them?

- COVID-19 and vitamin D

- Convalescent plasma therapy

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- COVID-19: How can I protect myself?

- Herd immunity and respiratory illness

- COVID-19 and pets

- COVID-19 antibody testing

- COVID-19, cold, allergies and the flu

- Long-term effects of COVID-19

- COVID-19 tests

- COVID-19 drugs: Are there any that work?

- COVID-19 in babies and children

- Coronavirus infection by race

- COVID-19 travel advice

- COVID-19 vaccine: Should I reschedule my mammogram?

- COVID-19 vaccines for kids: What you need to know

- COVID-19 vaccines

- COVID-19 variant

- COVID-19 vs. flu: Similarities and differences

- COVID-19: Who's at higher risk of serious symptoms?

- Debunking coronavirus myths

- Different COVID-19 vaccines

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

- Fever: First aid

- Fever treatment: Quick guide to treating a fever

- Fight coronavirus (COVID-19) transmission at home

- Honey: An effective cough remedy?

- How do COVID-19 antibody tests differ from diagnostic tests?

- How to measure your respiratory rate

- How to take your pulse

- How to take your temperature

- How well do face masks protect against COVID-19?

- Is hydroxychloroquine a treatment for COVID-19?

- Loss of smell

- Mayo Clinic Minute: You're washing your hands all wrong

- Mayo Clinic Minute: How dirty are common surfaces?

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pregnancy and COVID-19

- Safe outdoor activities during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Safety tips for attending school during COVID-19

- Sex and COVID-19

- Shortness of breath

- Thermometers: Understand the options

- Treating COVID-19 at home

- Unusual symptoms of coronavirus

- Vaccine guidance from Mayo Clinic

- Watery eyes

Related information

- Mental health: What's normal, what's not - Related information Mental health: What's normal, what's not

- Mental illness - Related information Mental illness

Help transform healthcare

Your donation can make a difference in the future of healthcare. Give now to support Mayo Clinic's research.

- Find a Doctor

- Patients & Visitors

- ER Wait Times

- For Medical Professionals

- Piedmont MyChart

- Medical Professionals

- Find Doctors

- Find Locations

Receive helpful health tips, health news, recipes and more right to your inbox.

Sign up to receive the Living Real Change Newsletter

Managing stress during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic

Are you feeling stress, fear and anxiety amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic ? If so, you’re not alone. The recommendations for masking and social distancing affect nearly every part of our lives, including finances, relationships, transportation, jobs and healthcare.

Some common causes of stress during the coronavirus pandemic are uncertainty, lack of routine and reduced social support, says Mark Flanagan, LMSW, MPH, MA, a social worker at Cancer Wellness at Piedmont .

Routines and COVID-19

As humans, we don’t like uncertainty and tend to thrive in routines , says Flanagan. Routines are essential because they create a sense of normalcy and control in our lives. This sense of control then allows us to manage the challenges that come our way.

“When we don’t have a routine, much of our time is spent trying to establish one,” says Flanagan. “Without a routine, we often pay attention to the things that are most ‘flashy.’ When big news happens, we tend to focus on it more.”

Social support and COVID-19

Not only are our routines currently disrupted, but the routines of everyone around us are as well.

“When something goes wrong in our lives, we can usually rely on others to get a sense of calm,” he says. “But when everyone is experiencing the same sense of uncertainty, there’s no real ‘anchor’ to help manage some of the stress.”

Stress affects your health

Stress management is essential for good physical health , and it’s especially important right now as our world addresses the COVID-19 pandemic .

“While short-term pressures and stress are normal and can help us change in positive ways , chronic stress causes a huge deterioration in our quality of life on a physical level,” says Flanagan. “When we are more pessimistic, depressed or anxious, our immune system goes down and produces more stress hormones, reducing our immunity and increasing inflammation.”

Stress can also put a strain on your mental health, relationships and productivity, he notes.

Stress reduction tips for COVID-19

“Rather than dwell on nervousness, focus on the things you can control,” Flanagan suggests. “When you move the locus of control from something outside yourself to inside yourself, you powerfully reduce anxiety and boost confidence.”

He suggests the following steps to regain control and reduce stress.

Follow the recommended health guidelines. These guidelines include getting the COVID-19 vaccine , frequent hand-washing, wearing a mask in public places, social distancing, practicing respiratory etiquette and cleaning commonly used surfaces. See the latest recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Not only will you protect your health, but you’ll also protect the health of vulnerable people in your community, like older adults and those with serious or underlying health issues.

Create a morning routine. When you’re stuck at home, it can be tempting to let go of basic routines, but Flanagan says a morning routine can help you feel more productive and positive. Consider waking up at the same time each day, exercising, showering, meditating, journaling, tidying your home or having a healthy breakfast as part of your morning ritual.

Check in with loved ones regularly. Staying in touch with family and friends can help reduce stress.

Consider ways to help others. This can include picking up groceries for a neighbor and leaving them at their door, donating to a local charity, or purchasing gift cards from your favorite restaurant. By taking the focus off yourself, you can experience reduced stress and a greater sense of well-being.

Have a daily self-care ritual. Self-care can include exercise, meditation, walking outside, reading, taking a bubble bath, painting, journaling, gardening, cooking a healthy meal or enjoying a favorite hobby. Pick one thing and do it at the same time each day. It will help anchor your day and provide a welcome respite.

Limit news and media consumption. “When we constantly check our newsfeeds and see bad news, it activates our sympathetic nervous system and can send us into fight-or-flight mode,” says Flanagan. He recommends limiting how often you check the news to once or twice a day (ideally not first thing in the morning or after dinner), turning off news alerts, and obtaining information from one or two reputable news outlets.

Set boundaries around social media. “There’s this concept of toxic sociality where we constantly have to be connected, even in superficial ways, and when we’re not, it feels like part of us isn’t being ‘fed,’” he explains. “It’s important to practice social distancing with social media too. We may not think we’re having any effect on our newsfeed, but we can take steps to reduce the ripple effect of panic on social media.” He suggests posting positive messages online and being mindful of your likes, shares and comments.

Meditate. Meditation can help restore your sense of control as you focus on your breath or a positive word or phrase. “ Meditation can help you activate your parasympathetic nervous system, and that’s an antidote to fear,” says Flanagan. “And when you’re more centered, you’re able to create a calm reality around you.” Try this guided meditation to get started.

Encourage others. “Often, when we are scared, it can be tempting to repeat negative messages, but actively encouraging family and friends is really important,” he says. “Chances are, someone is having a harder time than you are. Your words matter and people will respond accordingly. It’s important to realize we are not victims; we are helping to create our environment and change it for the better. By sending positive messages out into the world, you’ll not only affect those around you, but those words will come back to you.”

Hope during the coronavirus pandemic

“It’s important to remember that this will pass sooner or later,” says Flanagan. “The world has gone through many different challenges, like disease outbreaks, war and uncertain times. For better or worse, these times always pass. That doesn’t mean this time isn’t significantly challenging, but if we focus on what we can control and do things that are good for our health and the health of those around us, we will come out of this in perhaps a more whole state and with a renewed perspective. It’s important to look toward the future and begin building for that future. You can always have hope. Hope never leaves us.”

For information on coronavirus (COVID-19), including symptoms, risks and ways to protect yourself, click here.

- coronavirus

- infectious disease

- stress management

Related Stories

Schedule your appointment online

Schedule with our online booking tool

*We have detected that you are using an unsupported or outdated browser. An update is not required, but for best search experience we strongly recommend updating to the latest version of Chrome, Firefox, Safari, or Internet Explorer 11+

Share this story

Download the Piedmont Now app

- Indoor Hospital Navigation

- Find & Save Physicians

- Online Scheduling

Download the app today!

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

The Impact of Different Coping Styles on Psychological Distress during the COVID-19: The Mediating Role of Perceived Stress

1 Graduate School of Education, Fordham University, New York, NY 10023, USA; ude.mahdrof@4gnidy (Y.D.); ude.mahdrof@62gnawhj (J.H.)

2 Beijing Key Laboratory of Applied Experimental Psychology, National Demonstration Center for Experimental Psychology Education, Faculty of Psychology, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China; moc.361@ysp_cxf (X.F.); moc.361@iewgnohysp (W.H.)

Jacqueline Hwang

3 Teachers’ College, Beijing Union University, Beijing 100874, China; nc.ude.unb.liam@aijgnaw

Associated Data

We do not provide public access to the data set due to protection of the privacy of the participants. Regarding the details of the data, please contact the corresponding author.