Social Stratification: Definition, Types & Examples

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- The term social stratification refers to how societies categorize people based on factors such as wealth, income, education, family background, and power.

- Social stratification exists in all societies in some form. However, it is easier to move up socially in some than others. Societies with more vertical social mobility have open stratification systems, and those with low vertical mobility have closed stratification systems.

- The importance of stratification is that those at the top of the hierarchy have greater access to scarce resources than those at the bottom.

- Sociologists have created four main categories of social stratification systems: class systems, caste systems, slavery, and meritocracy. The last of these is a largely hypothetical system.

- Class consistency refers to the variability of one”s social status among many dimensions (such as education and wealth) during one”s lifetime. More open stratification systems tend to encourage lower class consistency than closed stratification systems.

- Social stratification can work along multiple dimensions, such as those of race, gender, sexuality, religion, ethnicity, and so on. Intersectionality is a method for studying systems of social stratification through the lens of multiple identities.

What is Meant by Social Stratification?

Social stratification refers to a society”s categorization of its people into rankings based on factors such as wealth, income, education, family background, and power. Someones” place within a system of social stratification is called their socioeconomic status.

Social stratification is a relatively fixed, hierarchical arrangement in society by which groups have different access to resources, power, and perceived social worth.

Although many people and institutions in Western Societies indicate that they value equality — the belief that everyone has an equal chance at success and that hard work and talent — not inherited wealth, prejudicial treatment, racism, or societal values — determine social mobility , sociologists recognize social stratification as a society-wide system that makes inequalities apparent.

While there are inequalities between individuals, sociologists are interested in large social patterns. That is to say, sociologists look to see if those with similar backgrounds, group memberships, identities, and geographic locations share the same social stratification.

While some cultures may outwardly say that one’s climb and descent in socioeconomic status depends on individual choices, sociologists see how the structure of society affects a person’s social standing and, therefore, is created and supported by society.

Origins Social Stratification

Human social stratification has taken on many forms throughout the course of history. In foraging societies, for example, social status usually depended on hunting and leadership ability, particularly in males (Gurven & von Rueden, 2006).

Those who brought back meat for meals were held in higher status than those who rarely succeeded at hunting.

Meanwhile, in parts of the world where agriculture has replaced hunting and gathering, Anne’s land holdings often form the basis for social stratification. These holdings tend to be transmitted throughout generations.

This intergenerational transfer of wealth gave rise to what is known as estates, which were dominant in medieval Europe (Ertman, 1997).

The rise of agriculture also brought the emergence of cities, each with its own forms of stratification, now centered on one”‘s occupation. As the skills needed for acquiring certain occupational skills grew, so did the intergenerational transmission of status according to one”‘s occupational class.

One example of stratification according to occupational classes are guilds (Gibert, 1986). More rigid occupational classes are called castes, which exist both in and outside India.

Examples of Stratification

The factors that define stratification vary from society to society. In many societies, stratification is an economic system based on wealth, or the net values of the money and assets a person has, and income, their wages or income from investments.

However, there are other important factors that influence social standing. In some cultures, for instance, prestige — be it obtained through going to a prestigious university, working for a prestigious company, or coming from an illustrious family — is valued. In others, social stratification is based on age.

The elderly may be either esteemed or disparaged and ignored. The cultural beliefs of societies often reinforce stratification.

Broadly, these factors define how societies are classified or stratified:

Economic condition: the amount someone earns;

Social class: classification based on, for example, economy and caste;

Social networks: the connections that people have — and the opportunities these allow people in finding jobs, partners, and so on.

One determinant of social standing is one”s parents. Parents tend to pass their social position onto their children, as well as the cultural norms, values, and beliefs that accompany a certain lifestyle. Parents can also transfer a network of friends and family members that provide resources and support.

This is why, in situations where someone who was born into one social status enters the environment of another — such as the child of an uneducated family entering college, the individual may fare worse than others; they lack the resources and support often provided to those whose parents have gone to college (Gutierrez et al., 2022).

A society’s occupational structure can also determine social stratification. For example, societies may consider some jobs — such as teaching, or nursing — to be noble professions, which people should do out of love and the greater good rather than for money.

In contrast, those in other professions, such as athletes and C-suite executives, do not receive this attitude. Thus, those who are highly-educated may receive relatively low pay (Gutierrez et al., 2022).

Types of Stratification

Slavery and indentured servitude are likely the most rigid types of social stratification. Both of these involve people being treated as actual property and are often based on race or ethnicity. The owner of a slave exploits a slave”s labor for economic gain.

Slavery is one of the lowest levels in any stratification system, as they possess virtually no power or wealth of their own.

Slavery is thought to have begun 10,000 years ago, after agricultural societies developed, as people in these societies made prisoners of war work on their farm.

As in other social stratification systems, the status of one”s parents often defines whether or not someone will be put into slavery. However on a historic level, slavery has also been used as a punishment for crimes and as a way of controlling those in invaded or enemy territories.

For example, ancient Roman slaves were in large part from conquered regions (Gutierrez et al., 2022).

Slavery regained its property after the European colonization of the Western Hemisphere in the 1500s. Portuguese and Spanish colonists who settled in Brazil and the Caribbean enslaved native populations, and people from Africa were shipped to the “new world” to carry out various tasks.

Notably, the United State’s early gricultural economy was one intertwined with slavery, a fact that would help lead the Civil War after it won its independence from Britain.

Slavery still exists in many parts of the world.

Modern slaves include those taken as prisoners of war in ethnic conflicts, girls and women captured and kidnapped and used as prostitutes or sex slaves, children sold by their parents to be child laborers, and workers paying off debts who are abused, or even tortured, to the extent that they are unable to leave (Bales, 2007).

Even in societies that have officially outlawed slavery, the practice continues to have wide-ranging repercussions on socioeconomic standing. For example, some observers believe that a caste system existed in the southern part of the United States until the civil rights movement ended legal racial segregation. Rights, such as the right to vote and to a fair trial, were denied in practice, and lynchings were common for many decade (Litwack, 2009).

South Africa, meanwhile, had an official caste system known as apartheid until the 1990s. Although black people constituted the majority of the nation”s population, they had the worst jobs, could not vote, and lived in poor, segregated neighborhoods.

Both systems have, to the consensus of many sociologists, provided those of color with lower intergenerational wealth and higher levels of prejudice than their white counterparts, systematically hampering vertical class mobility.

Caste Systems

Caste systems are closed stratification systems, meaning that people can do very little to change the social standing of their birth. Caste systems determine all aspects of an individual”s life, such as appropriate occupations, marriage partners, and housing.

Those who defy the expectations of their caste may descend to a lower one. Individual talents and interests do not provide opportunities to improve one”s social standing.

The Indian caste system is based on the principles of Hinduism.

Those who are in higher castes are considered to be more spiritually pure, and those in lower castes — most notably, the “untouchable” — are said to be paying remuneration for misbehavior in past lives. In sociological terms, the belief used to support a system of stratification is called an ideology, and underlies the social systems of every culture (Gutierrez et al., 2022).

In caste systems, people are expected to work in an occupation and to enter into a marriage based on their caste. Accepting this social standing is a moral duty, and acceptance of one”s social standing is socialized from childhood.

While the Indian caste system has been dismantled on an official, constitutional level, it is still deeply embedded in Indian society outside of urban areas.

The Class System

Class systems are based on both social factors and individual achievement. Classes consist of sets of people who have similar status based on factors such as wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation.

Class systems, unlike caste systems, are open. This means that people can move to a different level of education or employment status than their parents. A combination of personal choice, opportunity, and one’s beginning status in society each play a role.

Those in class systems can socialize with and marry members of other classes.

In a case where spouses come from different social classes, they form an exogamous marriage. Often, these exogamous marriages focus on values such as love and compatibility.

Though there are social conformities that encourage people to marry those within their own class, people are not prohibited from choosing partners based solely on social ranking (Giddens et al., 1991).

Meritocracy (as an ideal system of stratification)

Meritocracy , meanwhile, is a hypothetical social stratification system in which one’s socioeconomic status is determined by personal effort and merit.

However, sociologists agree that no societies in history have determined social standing solely on merit.

Nonetheless, sociologists see aspects of meritocracies in modern societies when they study the role of academic and job performance and the systems in place intended to evaluate and reward achievement in these areas (Giddens et al., 1991).

Systems of Stratification

Sociologists have distinguished between two systems of stratification: closed and open. Closed systems accommodate for little change in social position.

It is difficult, if not impossible, for people to shift levels and social relationships between levels are largely verboten.

For example, estates, slavery, and caste systems are all closed systems. In contrast, open systems of social stratification are — nominatively, at least — based on achievement and allow for movement and interaction between layers and classes (Giddens et al., 1991).

What is Status Consistency?

The term status consistency describes the consistency — or lack thereof — of an individual”s rank across factors that determine social stratification within a lifetime. For example, a child in a class system may fail to finish high school — a trait of the lower class — and take up a manual job at a store”s warehouse — consistent with the lower or working class.

However, through persistence and favor with their employers, this person may work their way up to managing the store or even joining the corporation”s higher level management – an occupation consistent with the upper-middle class.

The discrepancies between someone’s educational level, occupation, and income represent low status consistency. Caste and closed systems, meanwhile, have high status consistency, as one”‘s birth status tends to control various aspects of one’s life.

The Role of Intersectionality

Intersectionality is an approach to the sociological study of social stratification. Sociologists have preferred it because it does not reduce the complexity of power constructions along a single social division, as has often been the case in stratification theories.

Generally, societies are stratified against one or more lines. These include race and ethnicity, sex and gender, age, religion, disability, and social class. Kimberle Crenshaw introduced the concept of intersectionality as a way of analyzing the intersection of race and gender (2017).

Crenshaw analyzed legal cases involving discrimination experienced by African American roman along the lines of both racism and sexist. The essence of intersectionality, as articulated by the sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (1990), is that sociologists cannot separate the effects of race, social class, gender, sexual orientation, age, disability, and so on in understanding social stratification (Gutierrez et al., 2022).

Bales, K. (2007). What predicts human trafficking?. International journal of comparative and applied criminal justice, 31 (2), 269-279.

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black feminist thought in the matrix of domination. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment, 138 (1990), 221-238.

Crenshaw, K. W. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press.

Ertman, T. (1997). Birth of the Leviathan: Building states and regimes in medieval and early modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. Giddens, A., Duneier, M., Appelbaum, R. P., & Carr, D. S. (1991). Introduction to sociology . Norton.

Gilbert, G. N. (1986). Occupational classes and inter-class mobility. British Journal of Sociology , 370-391.

Grusky, D. (2019). Social stratification, class, race, and gender in sociological perspective . Routledge.

Grusky, D. B., & Sørensen, J. B. (1998). Can class analysis be salvaged ?. American journal of Sociology, 103(5), 1187-1234.

Gurven, M., & Von Rueden, C. (2006). Hunting, social status and biological fitness. Social biology, 53(1-2), 81-99.

Gutierrez, E., Hund, J., Johnson, S., Ramos, C., Rodriguez, L., & Tsuhako, J. (2022). Social Stratification and Intersectionality .

Litwack, L. F. (2009). How free is free?: The long death of Jim Crow (Vol. 6). Harvard University Press.

What is social stratification?

Social stratification refers to the way in which society is organized into layers or strata, based on various factors like wealth, occupation, education level, race, or gender.

It’s essentially a kind of social hierarchy where individuals and groups are classified on the basis of esteemed social values and the unequal distribution of resources and power.

What is the main purpose of social stratification?

Ensures Roles are Filled by the Competent: Stratification means that positions are given to those who have the ability and skill to execute the duties of the job. People in higher strata often have higher education and skills.

Maintains Social Order: By establishing a hierarchy and clear societal roles, stratification can contribute to overall societal stability and order.

9.4 Theoretical Perspectives on Social Stratification

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Apply functionalist, conflict theory, and interactionist perspectives on social stratification

Basketball is one of the highest-paying professional sports and stratification exists even among teams in the NBA. For example, the Toronto Raptors hands out the lowest annual payroll, while the New York Knicks reportedly pays the highest. Stephen Curry, a Golden State Warriors guard, is one of the highest paid athletes in the NBA, earning around $43 million a year (Sports Illustrated 2020), whereas the lowest paid player earns just over $200,000 (ESPN 2021). Even within specific fields, layers are stratified, members are ranked, and inequality exists.

In sociology, even an issue such as NBA salaries can be seen from various points of view. Functionalists will examine the purpose of such high salaries, conflict theorists will study the exorbitant salaries as an unfair distribution of money, and symbolic interactionists will describe how players display that wealth. Social stratification takes on new meanings when it is examined from different sociological perspectives—functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism.

Functionalism

In sociology, the functionalist perspective examines how society’s parts operate. According to functionalism, different aspects of society exist because they serve a vital purpose. What is the function of social stratification?

In 1945, sociologists Kingsley Davis and Wilbert Moore published the Davis-Moore thesis , which argued that the greater the functional importance of a social role, the greater must be the reward. The theory posits that social stratification represents the inherently unequal value of different work. Certain tasks in society are more valuable than others (for example, doctors or lawyers). Qualified people who fill those positions are rewarded more than others.

According to Davis and Moore, a firefighter’s job is more important than, for instance, a grocery store cashier’s job. The cashier position does not require similar skill and training level as firefighting. Without the incentive of higher pay, better benefits, and increased respect, why would someone be willing to rush into burning buildings? If pay levels were the same, the firefighter might as well work as a grocery store cashier and avoid the risk of firefighting. Davis and Moore believed that rewarding more important work with higher levels of income, prestige, and power encourages people to work harder and longer.

Davis and Moore stated that, in most cases, the degree of skill required for a job determines that job’s importance. They noted that the more skill required for a job, the fewer qualified people there would be to do that job. Certain jobs, such as cleaning hallways or answering phones, do not require much skill. Therefore, most people would be qualified for these positions. Other work, like designing a highway system or delivering a baby, requires immense skill limiting the number of people qualified to take on this type of work.

Many scholars have criticized the Davis-Moore thesis. In 1953, Melvin Tumin argued that it does not explain inequalities in the education system or inequalities due to race or gender. Tumin believed social stratification prevented qualified people from attempting to fill roles (Tumin 1953).

Conflict Theory

Conflict theorists are deeply critical of social stratification, asserting that it benefits only some people, not all of society. For instance, to a conflict theorist, it seems wrong that a basketball player is paid millions for an annual contract while a public school teacher may earn $35,000 a year. Stratification, conflict theorists believe, perpetuates inequality. Conflict theorists try to bring awareness to inequalities, such as how a rich society can have so many poor members.

Many conflict theorists draw on the work of Karl Marx. During the nineteenth-century era of industrialization, Marx believed social stratification resulted from people’s relationship to production. People were divided into two main groups: they either owned factories or worked in them. In Marx’s time, bourgeois capitalists owned high-producing businesses, factories, and land, as they still do today. Proletariats were the workers who performed the manual labor to produce goods. Upper-class capitalists raked in profits and got rich, while working-class proletariats earned skimpy wages and struggled to survive. With such opposing interests, the two groups were divided by differences of wealth and power. Marx believed workers experience deep alienation, isolation and misery resulting from powerless status levels (Marx 1848). Marx argued that proletariats were oppressed by the bourgeoisie.

Today, while working conditions have improved, conflict theorists believe that the strained working relationship between employers and employees still exists. Capitalists own the means of production, and a system is in place to make business owners rich and keep workers poor. According to conflict theorists, the resulting stratification creates class conflict.

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism uses everyday interactions of individuals to explain society as a whole. Symbolic interactionism examines stratification from a micro-level perspective. This analysis strives to explain how people’s social standing affects their everyday interactions.

In most communities, people interact primarily with others who share the same social standing. It is precisely because of social stratification that people tend to live, work, and associate with others like themselves, people who share their same income level, educational background, class traits and even tastes in food, music, and clothing. The built-in system of social stratification groups people together. This is one of the reasons why it was rare for a royal prince like England’s Prince William to marry a commoner.

Symbolic interactionists also note that people’s appearance reflects their perceived social standing. As discussed above, class traits seen through housing, clothing, and transportation indicate social status, as do hairstyles, taste in accessories, and personal style. Symbolic interactionists also analyze how individuals think of themselves or others interpretation of themselves based on these class traits.

To symbolically communicate social standing, people often engage in conspicuous consumption , which is the purchase and use of certain products to make a social statement about status. Carrying pricey but eco-friendly water bottles could indicate a person’s social standing, or what they would like others to believe their social standing is. Some people buy expensive trendy sneakers even though they will never wear them to jog or play sports. A $17,000 car provides transportation as easily as a $100,000 vehicle, but the luxury car makes a social statement that the less expensive car can’t live up to. All these symbols of stratification are worthy of examination by an interactionist.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/9-4-theoretical-perspectives-on-social-stratification

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Module 7: Stratification and Inequality

Social stratification, social inequality, and global stratification, learning objectives.

- Describe social stratification and social inequality

- Explain global stratification

Social Stratification

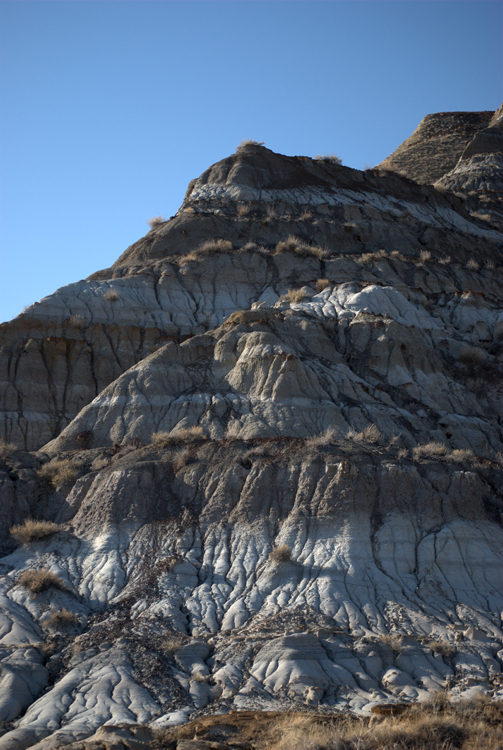

Figure 1. Strata in rock illustrate social stratification. People are sorted, or layered, into social categories. Many factors determine a person’s social standing, such as income, education, occupation, geography, as well as age, race, gender, and even physical abilities. (Photo courtesy of Just a Prairie Boy/flickr)

Social stratification is a system of ranking individuals and groups within societies. It refers to a society’s ranking of its people into socioeconomic tiers based on factors like wealth, income, race, education, and power. You may remember the word “stratification” from geology class. The distinct horizontal layers found in rock, called “strata,” are an illustrative way to visualize social structure. Society’s layers are made of people, and society’s resources are distributed unevenly throughout the layers. Social stratification has been a part of all societies dating from the agricultural revolution, which took place in various parts of the world between 7,000-10,000 BCE. Unlike relatively even strata in rock, though, there are not equal numbers of people in each layer of society. There are typically very few at the top and a great many at the bottom, with some variously populated layers in the middle.

Social Inequality

Social inequality is the state of unequal distribution of valued goods and opportunities. All societies today have social inequality. Examining social stratification requires a macrosociological perspective in order to view societal systems that make inequalities visible. Although individuals may support or fight inequalities, social stratification is created and supported by society as a whole through values and norms and consistently durable systems of stratification.

Most of us are accustomed to thinking of stratification as economic inequality. For example, we can compare wages in the United States to wages in Mexico. Social inequality, however, is just as harmful as economic discrepancy. Prejudice and discrimination—whether against a certain race, ethnicity, religion, or the like—can become a causal factor by creating and aggravating conditions of economic inequality, both within and between nations.

Gender inequality is another global concern. Consider the controversy surrounding female circumcision (also known as female genital mutilation or FGM). Nations favoring this practice, often through systems of patriarchal authority, defend it as a longstanding cultural tradition among certain tribes and argue that the West shouldn’t interfere. Western nations, however, decry the practice and are working to expose and stop it.

Inequalities based on sexual orientation and gender identity exist around the globe. According to Amnesty International, a range of crimes are commonly committed against individuals who do not conform to traditional gender roles or sexual orientations (however those are culturally defined). From culturally sanctioned rape to state-sanctioned executions, the abuses are serious. These legalized and culturally accepted forms of prejudice, discrimination, and punishment exist everywhere—from the United States to Somalia to Tibet—restricting the freedom of individuals and often putting their lives at risk (Amnesty International 2012).

Watch the selected first few minutes of this video to learn about stratification in general terms. You’ll learn some key principles regarding social stratification, namely that:

- Stratification is universal, but varies between societies;

- It is a characteristic of society and not a matter of individual differences; in other words, we need to use the sociological imagination to understand social stratification and see it as a social issue and not just an individual problem;

- It persists across generations, although it often allows for some degree of social mobility;

- Stratification continues because of beliefs and attitudes about social stratification

Thinking Deeply about Inequality

How do you think wealth should best be distributed in the United States? Check out this interactive animation on economic inequality from the Economic Policy Institute .

Link to Learning

Imagine that the United States is divided into quintiles (bottom 20%, second 20%, middle 20%, fourth 20%, and top 20%).

- How do you think wealth is distributed in the United States? What percentage would you attribute to each quintile?

- What do you think is the ideal distribution?

Now watch the video “Wealth Inequality in America” and compare your responses to the actual distribution of wealth. Keep in mind that these numbers are from 2012, but the rates of inequality have not improved since then.

Global Stratification

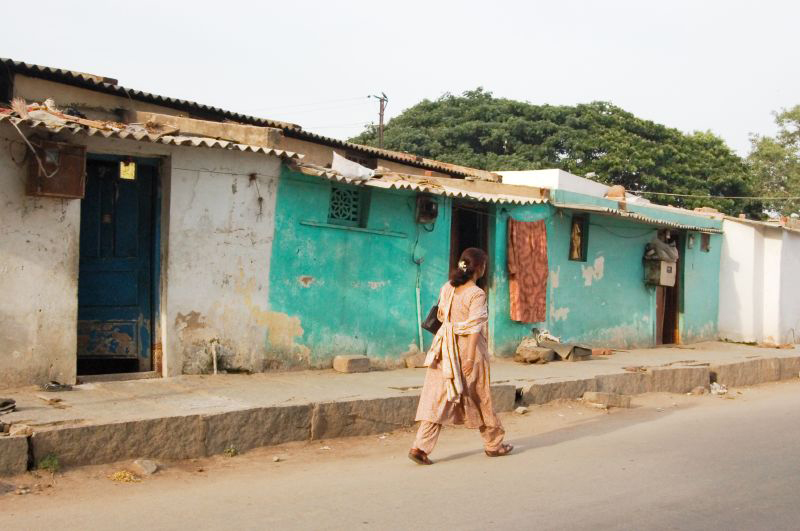

Figure 2. (a) A family lives in this grass hut in Ethiopia. (b) Another family lives in a single-wide trailer in a trailer park in the United States. Both families are considered poor, or lower class. With such differences in global stratification, what constitutes poverty? (Photo (a) courtesy of Canned Muffins/flickr; Photo (b) courtesy of Herb Neufeld/flickr)

While stratification in the United States refers to the unequal distribution of resources among individuals, global stratification refers to this unequal distribution among nations. There are two dimensions to this stratification: gaps between nations and gaps within nations. When it comes to global inequality, both economic inequality and social inequality may concentrate the burden of poverty among certain segments of the earth’s population (Myrdal 1970).

As mentioned earlier, one way to evaluate stratification is to consider how many people are living in poverty, and particularly extreme poverty, which is often defined as needing to survive on less than $1.90 per day. Fortunately, until the COVID-19 pandemic impacted economies in 2020, the extreme poverty rate had been on a 20-year decline. In 2015, 10.1 percent of the world’s population was living in extreme poverty; in 2017, that number had dropped an entire percentage point to 9.2 percent. While a positive, that 9.2 percent is equivalent to 689 million people living on less than $1.90 a day. The same year, 24.1 percent of the world lived on less than $3.20 per day and 43.6 percent on less than $5.50 per day in 2017 (World Bank 2020). The table below makes the differences in poverty very clear.

| Country | Percentage of people living on less than $1.90 | Percentage of people living on less than $3.90 | Percentage of people living on less than $5.50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colombia | 4.1 | 10.9 | 27.8 |

| Costa Rica | 1.4 | 3.6 | 10.9 |

| Georgia | 4.5 | 15.7 | 42.9 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 0.9 | 15.5 | 61.3 |

| Sierra Leone | 40.1 | 74.4 | 92.1 |

| Angola | 51.8 | 73.2 | 89.3 |

| Lithuania | 0.7 | 1.0 | 3.8 |

| Ukraine | 0.0 | 0.4 | 4.0 |

| Vietnam | 1.9 | 7.0 | 23.6 |

| Indonesia | 3.6 | 9.6 | 53.2 |

Global stratification compares the wealth, economic stability, status, and power of countries across the world, and also highlights worldwide patterns of social inequality within nations.

In the early years of civilization, hunter-gatherer and agrarian societies lived off the earth and rarely interacted with other societies (except during times of war). As civilizations began to grow and emerging cities developed political and economic systems, trade increased, as did military conquest. Explorers went out in search of new land and resources as well as to trade goods, ideas, and customs. They eventually took land, people, and resources from all over the world, building empires and establishing networks of colonies with imperialist policies, foundational religious ideologies, and incredible economic and military power.

In the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution created unprecedented wealth in Western Europe and North America. Due to mechanical inventions and new means of production, people began working in factories—not only men, but women and children as well. The Industrial Revolution also saw the rise of vast inequalities between countries that were industrialized and those that were not. As some nations embraced technology and saw increased wealth and goods, others maintained their ways; as the gap widened, the non-industrialized nations fell further behind. Some social researchers, such as Walt Rostow, suggest that the disparity also resulted from power differences. Applying a conflict theory perspective, he asserts that industrializing nations appropriated and took advantage of the resources of traditional nations. As industrialized nations became rich, other nations became poor (Rostow 1960).

Sociologists studying global stratification analyze economic comparisons between nations. Income, purchasing power, and investment and ownership-based wealth are used to calculate global stratification. Global stratification also compares the quality of life that individual citizens and groups within a country’s population can have.

Poverty levels have been shown to vary greatly. The poor in wealthy countries like the United States or Europe are much better off than the poor in less-industrialized countries such as Mali or India. In 2002, the UN implemented the Millennium Project, an attempt to cut poverty worldwide by the year 2015. To reach the project’s goal, planners in 2006 estimated that industrialized nations must set aside 0.7 percent of their gross national income—the total value of the nation’s good and service, plus or minus income received from and sent to other nations—to aid in developing countries (Landler and Sanger, 2009; Millennium Project 2006).

Although some successes have been realized from the Millennium Project , such as cutting the extreme global poverty rate in half, the United Nations has now moved ahead with their program of economic growth and sustainable development in their new project, Sustainable Development Goals , adopted in September of 2015.

Think It Over

- The wealthiest 300 individuals in the world have more wealth than the poorest 3 billion individuals. Does this surprise you? Why or why not?

- Why has the wealth gap between the wealthiest countries and the poorest countries grown larger? How is this different from dominant narratives in the media?

- What changes could be made to reduce global stratification and inequality?

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by : Sarah Hoiland and Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- What Is Social Stratification?. Authored by : OpenStax CNX. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:LYDnfp5S@3/What-Is-Social-Stratification . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

- Global Stratification and Classification. Provided by : OpenStax College. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:7TCPamHd@3/Global-Stratification-and-Classification . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected].

- Global Stratification and Classification. Provided by : OpenStax. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/10-1-global-stratification-and-classification . Project : Sociology 3e. License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/10-1-global-stratification-and-classification

- Global Wealth Inequality. Authored by : TheRulesOrg. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uWSxzjyMNpU . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Social Stratification: Crash Course Sociology #21. Provided by : CrashCourse. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlkIKCMt-Fs . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

38 What Is Social Stratification?

Learning objectives.

- Differentiate between open and closed stratification systems

- Distinguish between caste and class systems

- Understand meritocracy as an ideal system of stratification

Sociologists use the term social stratification to describe the system of social standing. Social stratification refers to a society’s categorization of its people into rankings of socioeconomic tiers based on factors like wealth, income, race, education, and power.

You may remember the word “stratification” from geology class. The distinct vertical layers found in rock, called stratification, are a good way to visualize social structure. Society’s layers are made of people, and society’s resources are distributed unevenly throughout the layers. The people who have more resources represent the top layer of the social structure of stratification. Other groups of people, with progressively fewer and fewer resources, represent the lower layers of our society.

In the United States, people like to believe everyone has an equal chance at success. To a certain extent, Aaron illustrates the belief that hard work and talent—not prejudicial treatment or societal values—determine social rank. This emphasis on self-effort perpetuates the belief that people control their own social standing.

However, sociologists recognize that social stratification is a society-wide system that makes inequalities apparent. While there are always inequalities between individuals, sociologists are interested in larger social patterns. Stratification is not about individual inequalities, but about systematic inequalities based on group membership, classes, and the like. No individual, rich or poor, can be blamed for social inequalities. The structure of society affects a person’s social standing. Although individuals may support or fight inequalities, social stratification is created and supported by society as a whole.

Factors that define stratification vary in different societies. In most societies, stratification is an economic system, based on wealth , the net value of money and assets a person has, and income , a person’s wages or investment dividends. While people are regularly categorized based on how rich or poor they are, other important factors influence social standing. For example, in some cultures, wisdom and charisma are valued, and people who have them are revered more than those who don’t. In some cultures, the elderly are esteemed; in others, the elderly are disparaged or overlooked. Societies’ cultural beliefs often reinforce the inequalities of stratification.

One key determinant of social standing is the social standing of our parents. Parents tend to pass their social position on to their children. People inherit not only social standing but also the cultural norms that accompany a certain lifestyle. They share these with a network of friends and family members. Social standing becomes a comfort zone, a familiar lifestyle, and an identity. This is one of the reasons first-generation college students do not fare as well as other students.

Other determinants are found in a society’s occupational structure. Teachers, for example, often have high levels of education but receive relatively low pay. Many believe that teaching is a noble profession, so teachers should do their jobs for love of their profession and the good of their students—not for money. Yet no successful executive or entrepreneur would embrace that attitude in the business world, where profits are valued as a driving force. Cultural attitudes and beliefs like these support and perpetuate social inequalities.

Recent Economic Changes and U.S. Stratification

As a result of the Great Recession that rocked our nation’s economy in the last few years, many families and individuals found themselves struggling like never before. The nation fell into a period of prolonged and exceptionally high unemployment. While no one was completely insulated from the recession, perhaps those in the lower classes felt the impact most profoundly. Before the recession, many were living paycheck to paycheck or even had been living comfortably. As the recession hit, they were often among the first to lose their jobs. Unable to find replacement employment, they faced more than loss of income. Their homes were foreclosed, their cars were repossessed, and their ability to afford healthcare was taken away. This put many in the position of deciding whether to put food on the table or fill a needed prescription.

While we’re not completely out of the woods economically, there are several signs that we’re on the road to recovery. Many of those who suffered during the recession are back to work and are busy rebuilding their lives. The Affordable Health Care Act has provided health insurance to millions who lost or never had it.

But the Great Recession, like the Great Depression, has changed social attitudes. Where once it was important to demonstrate wealth by wearing expensive clothing items like Calvin Klein shirts and Louis Vuitton shoes, now there’s a new, thriftier way of thinking. In many circles, it has become hip to be frugal. It’s no longer about how much we spend, but about how much we don’t spend. Think of shows like Extreme Couponing on TLC and songs like Macklemore’s “Thrift Shop.”

Systems of Stratification

Sociologists distinguish between two types of systems of stratification. Closed systems accommodate little change in social position. They do not allow people to shift levels and do not permit social relationships between levels. Open systems, which are based on achievement, allow movement and interaction between layers and classes. Different systems reflect, emphasize, and foster certain cultural values and shape individual beliefs. Stratification systems include class systems and caste systems, as well as meritocracy.

The Caste System

Caste systems are closed stratification systems in which people can do little or nothing to change their social standing. A caste system is one in which people are born into their social standing and will remain in it their whole lives. People are assigned occupations regardless of their talents, interests, or potential. There are virtually no opportunities to improve a person’s social position.

In the Hindu caste tradition, people were expected to work in the occupation of their caste and to enter into marriage according to their caste. Accepting this social standing was considered a moral duty. Cultural values reinforced the system. Caste systems promote beliefs in fate, destiny, and the will of a higher power, rather than promoting individual freedom as a value. A person who lived in a caste society was socialized to accept his or her social standing.

Although the caste system in India has been officially dismantled, its residual presence in Indian society is deeply embedded. In rural areas, aspects of the tradition are more likely to remain, while urban centers show less evidence of this past. In India’s larger cities, people now have more opportunities to choose their own career paths and marriage partners. As a global center of employment, corporations have introduced merit-based hiring and employment to the nation.

The Class System

A class system is based on both social factors and individual achievement. A class consists of a set of people who share similar status with regard to factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation. Unlike caste systems, class systems are open. People are free to gain a different level of education or employment than their parents. They can also socialize with and marry members of other classes, which allows people to move from one class to another.

In a class system, occupation is not fixed at birth. Though family and other societal models help guide a person toward a career, personal choice plays a role.

In class systems, people have the option to form exogamous marriages , unions of spouses from different social categories. Marriage in these circumstances is based on values such as love and compatibility rather than on social standing or economics. Though social conformities still exist that encourage people to choose partners within their own class, people are not as pressured to choose marriage partners based solely on those elements. Marriage to a partner from the same social background is an endogamous union .

Meritocracy

Meritocracy is an ideal system based on the belief that social stratification is the result of personal effort—or merit—that determines social standing. High levels of effort will lead to a high social position, and vice versa. The concept of meritocracy is an ideal—because a society has never existed where social rank was based purely on merit. Because of the complex structure of societies, processes like socialization, and the realities of economic systems, social standing is influenced by multiple factors—not merit alone. Inheritance and pressure to conform to norms, for instance, disrupt the notion of a pure meritocracy. While a meritocracy has never existed, sociologists see aspects of meritocracies in modern societies when they study the role of academic and job performance and the systems in place for evaluating and rewarding achievement in these areas.

Status Consistency

Social stratification systems determine social position based on factors like income, education, and occupation. Sociologists use the term status consistency to describe the consistency, or lack thereof, of an individual’s rank across these factors. Caste systems correlate with high status consistency, whereas the more flexible class system has lower status consistency.

To illustrate, let’s consider Susan. Susan earned her high school degree but did not go to college. That factor is a trait of the lower-middle class. She began doing landscaping work, which, as manual labor, is also a trait of lower-middle class or even lower class. However, over time, Susan started her own company. She hired employees. She won larger contracts. She became a business owner and earned a lot of money. Those traits represent the upper-middle class. There are inconsistencies between Susan’s educational level, her occupation, and her income. In a class system, a person can work hard and have little education and still be in middle or upper class, whereas in a caste system that would not be possible. In a class system, low status consistency correlates with having more choices and opportunities.

On April 29, 2011, in London, England, Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, married Catherine Middleton, a commoner. It is rare, though not unheard of, for a member of the British royal family to marry a commoner. Kate Middleton has an upper-class background, but does not have royal ancestry. Her father was a former flight dispatcher and her mother a former flight attendant and owner of Party Pieces. According to Grace Wong’s 2011 article titled, “Kate Middleton: A family business that built a princess,” “[t]he business grew to the point where [her father] quit his job . . . and it’s evolved from a mom-and-pop outfit run out of a shed . . . into a venture operated out of three converted farm buildings in Berkshire.” Kate and William met when they were both students at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland (Köhler 2010).

Britain’s monarchy arose during the Middle Ages. Its social hierarchy placed royalty at the top and commoners on the bottom. This was generally a closed system, with people born into positions of nobility. Wealth was passed from generation to generation through primogeniture , a law stating that all property would be inherited by the firstborn son. If the family had no son, the land went to the next closest male relation. Women could not inherit property, and their social standing was primarily determined through marriage.

The arrival of the Industrial Revolution changed Britain’s social structure. Commoners moved to cities, got jobs, and made better livings. Gradually, people found new opportunities to increase their wealth and power. Today, the government is a constitutional monarchy with the prime minister and other ministers elected to their positions, and with the royal family’s role being largely ceremonial. The long-ago differences between nobility and commoners have blurred, and the modern class system in Britain is similar to that of the United States (McKee 1996).

Today, the royal family still commands wealth, power, and a great deal of attention. When Queen Elizabeth II retires or passes away, Prince Charles will be first in line to ascend the throne. If he abdicates (chooses not to become king) or dies, the position will go to Prince William. If that happens, Kate Middleton will be called Queen Catherine and hold the position of queen consort. She will be one of the few queens in history to have earned a college degree (Marquand 2011).

There is a great deal of social pressure on her not only to behave as a royal but also to bear children. In fact, Kate and Prince William welcomed their first son, Prince George, on July 22, 2013 and are expecting their second child. The royal family recently changed its succession laws to allow daughters, not just sons, to ascend the throne. Kate’s experience—from commoner to potential queen—demonstrates the fluidity of social position in modern society.

Stratification systems are either closed, meaning they allow little change in social position, or open, meaning they allow movement and interaction between the layers. A caste system is one in which social standing is based on ascribed status or birth. Class systems are open, with achievement playing a role in social position. People fall into classes based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation. A meritocracy is a system of social stratification that confers standing based on personal worth, rewarding effort.

Section Quiz

What factor makes caste systems closed?

- They are run by secretive governments.

- People cannot change their social standings.

- Most have been outlawed.

- They exist only in rural areas.

What factor makes class systems open?

- They allow for movement between the classes.

- People are more open-minded.

- People are encouraged to socialize within their class.

- They do not have clearly defined layers.

Which of these systems allows for the most social mobility?

Which person best illustrates opportunities for upward social mobility in the United States?

- First-shift factory worker

- First-generation college student

- Firstborn son who inherits the family business

- First-time interviewee who is hired for a job

Which statement illustrates low status consistency?

- A suburban family lives in a modest ranch home and enjoys a nice vacation each summer.

- A single mother receives food stamps and struggles to find adequate employment.

- A college dropout launches an online company that earns millions in its first year.

- A celebrity actress owns homes in three countries.

Based on meritocracy, a physician’s assistant would:

- receive the same pay as all the other physician’s assistants

- be encouraged to earn a higher degree to seek a better position

- most likely marry a professional at the same level

- earn a pay raise for doing excellent work

Short Answer

Track the social stratification of your family tree. Did the social standing of your parents differ from the social standing of your grandparents and great-grandparents? What social traits were handed down by your forebears? Are there any exogamous marriages in your history? Does your family exhibit status consistencies or inconsistencies?

What defines communities that have low status consistency? What are the ramifications, both positive and negative, of cultures with low status consistency? Try to think of specific examples to support your ideas.

Review the concept of stratification. Now choose a group of people you have observed and been a part of—for example, cousins, high school friends, classmates, sport teammates, or coworkers. How does the structure of the social group you chose adhere to the concept of stratification?

Further Research

The New York Times investigated social stratification in their series of articles called “Class Matters.” The online accompaniment to the series includes an interactive graphic called “How Class Works,” which tallies four factors—occupation, education, income, and wealth—and places an individual within a certain class and percentile. What class describes you? Test your class rank on the interactive site: http://openstax.org/l/NY_Times_how_class_works

Köhler, Nicholas. 2010. “An Uncommon Princess.” Maclean’s , November 22. Retrieved January 9, 2012 ( http://www2.macleans.ca/2010/11/22/an-uncommon-princess/ ).

McKee, Victoria. 1996. “Blue Blood and the Color of Money.” New York Times , June 9.

Marquand, Robert. 2011. “What Kate Middleton’s Wedding to Prince William Could Do for Britain.” Christian Science Monitor , April 15. Retrieved January 9, 2012 ( http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Europe/2011/0415/What-Kate-Middleton-s-wedding-to-Prince-William-could-do-for-Britain ).

Wong, Grace. 2011. “Kate Middleton: A Family Business That Built a Princess.” CNN Money . Retrieved December 22, 2014 (http://money.cnn.com/2011/04/14/smallbusiness/kate-middleton-party-pieces/).

Introduction to Sociology 2e Copyright © 2012 by OSCRiceUniversity (Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/introduction-sociology-2e) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- Founding the discipline

- Economic determinism

- Human ecology

- Social psychology

- Cultural theory

- Early functionalism

- The functionalist-conflict debate

- Rising segmentation of the discipline

Social stratification

Interdisciplinary influences.

- The historical divide: qualitative and establishment sociology

- Methodological considerations in sociology

- Ecological patterning

- Experiments

- Statistics and mathematical analysis

- Data collection

- National methodological preferences

- Academic status

- Scientific status

- Current trends

- Emerging roles for sociologists

- Where did Auguste Comte go to school?

- What was Auguste Comte best known for?

- Why is Herbert Spencer famous?

- Where was Émile Durkheim educated?

- Where did Émile Durkheim work?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- BCcampus Open Publishing - An Introduction to Sociology

- Social Science LibreTexts - An Introduction to Sociology

- The Canadian Encyclopedia - Sociology

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill - Department of Sociology - What is Sociology?

- Simply Sociology - What is Sociology: Origin and Famous Sociologists

- sociology - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- sociology - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Since social stratification is the most binding and central concern of sociology, changes in the study of social stratification reflect trends in the entire discipline . The founders of sociology—including Weber—thought that the United States , unlike Europe, was a classless society with a high degree of upward mobility. During the Great Depression , however, Robert and Helen Lynd , in their famous Middletown (1937) studies, documented the deep divide between the working and the business classes in all areas of community life. W. Lloyd Warner and colleagues at Harvard University applied anthropological methods to study the Social Life of a Modern Community (1941) and found six social classes with distinct subcultures: upper upper and lower upper, upper middle and lower middle, and upper lower and lower lower classes. In 1953 Floyd Hunter’s study of Atlanta, Georgia, shifted the emphasis in stratification from status to power; he documented a community power structure that controlled the agenda of urban politics. Likewise, C. Wright Mills in 1956 proposed that a “power elite” dominated the national agenda in Washington, a cabal comprising business, government, and the military.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, research in social stratification was influenced by the attainment model of stratification, initiated at the University of Wisconsin by William H. Sewell. Designed to measure how individuals attain occupational status, this approach assigned each occupation a socioeconomic score and then measured the distance between sons’ and fathers’ scores, also using the educational achievement of fathers to explain intergenerational mobility. Peter M. Blau and Otis Dudley Duncan used this technique in the study published as The American Occupational Structure (1967).

Attempting to build a general theory, Gerhard Lenski shifted attention to whole societies and proposed an evolutionary theory in Power and Privilege (1966) demonstrating that the dominant forms of production (hunting and gathering, horticulture, agriculture, and industry) were consistently associated with particular systems of stratification. This theory was enthusiastically accepted, but only by a minority of sociologists. Addressing the contemporary world, Marion Levy theorized in Modernization and the Structures of Societies (1960) that underdeveloped nations would inevitably develop institutions that paralleled those of the more economically advanced nations , which ultimately would lead to a global convergence of societies. Challenging the theory as a conservative defense of the West, Immanuel Wallerstein ’s The Modern World System (1974) proposed a more pessimistic world-system theory of stratification. Wallerstein averred that advanced industrial nations would develop most rapidly and thereby widen global inequality by holding the developing nations in a permanent state of dependency.

Having been challenged as a male-dominated approach, traditional stratification theory was massively reconstructed in the 1970s to address the institutional gender inequalities found in all societies. Rae Lesser Blumberg, drawing on the work of Lenski and economist Esther Boserup, theorized the basis of persistent inequality in Stratification, Socioeconomic, and Sexual Inequality (1978). Janet Saltzman Chafetz took economic, psychological, and sociological factors into account in Gender Equity: An Integrated Theory of Stability and Change (1990). Traditional theories of racial inequality were challenged and revised by William Julius Wilson in The Truly Disadvantaged (1987). His book uncovered mechanisms that maintained segregation and disorganization in African American communities . Disciplinary specialization, especially in the areas of gender, race, and Marxism, came to dominate sociological inquiry.

For example, Eric Olin Wright, in Classes (1985), introduced a 12-class scheme of occupational stratification based on ownership, supervisory control of work, and monopolistic knowledge. Wright’s book, an attack on the individualistic bias of attainment theory written from a Marxist perspective, drew on the traits of these 12 classes to explain income inequality . The nuanced differences between social groups were further investigated in Divided We Stand (1985) by William Form, whose analysis of labour markets revealed deep permanent fissures within working classes previously thought to be uniform.

Some investigative specializations, however, were short-lived. Despite their earlier popularity, ethnographic studies of communities, such as those by Hunter, Warner, and the Lynds, were increasingly abandoned in the 1960s and virtually forgotten by the 1970s. Intensive case studies of bureaucracies begun in the ’70s followed a similar path. Like economists, sociologists have increasingly turned to large-scale surveys and government data banks as sources for their research. Social stratification theory and research continue to undergo change and have seen substantive reappraisal ever since the breakup of the Soviet system.

The significant growth of sociological inquiry after World War II prompted interest in historical and political sociology. Charles Tilly in From Mobilization to Revolution (1978), Jack Goldstone in Revolutions: Theoretical, Comparative and Historical Studies (1993), and Arthur Stinchcombe in Constructing Social Theories (1987) made comparative studies of revolutions and proposed structural theories to explain the origins and spread of revolution. Sociologists who brought international and historical perspectives to their study of institutions such as education , welfare, religion, the family, and the military were forced to reconsider long-held theories and methodologies . As was the case in almost all areas of specialization, new journals were founded.

Sociological specialties were enriched by contact with other social sciences, especially political science and economics . Political sociology, for example, studied the social basis of party voting and partisan politics, spurring comparison of decision-making processes in city, state, and national governments. Still, sociologists split along ideological lines, much as they had in the functionalist-conflict divide, with some reporting that decisions were made pluralistically and democratically and others insisting that decisions were made by economic and political elites. Eventually, voting and community power studies were abandoned by sociologists, and those areas were left largely to political scientists.

From its inception, the study of social movements looked closely at interpersonal relations formed in the mobilization phase of collective action. Beginning in the 1970s, scholars focused more deeply on the long-term consequences of social movements, especially on evaluating the ways such movements have propelled societal change. The rich area of historical and international research that resulted includes the study of social turmoil’s influence on New Deal legislation; the rise, decline, and resurrection of women’s rights movements; analysis of both failed and successful revolutions; the impact of government and other institutions on social movements; national differences in how social movements spur discontent; the response of nascent movements to political changes; and variations in the rates of growth and decline of movements over time and in different nations. In short, countering the general trend, social movement research became better integrated into other specialties, especially in political and organizational sociology.

Stratification studies and organizational sociology were broadened to include economic phenomena such as labour markets and the behaviour of businesses. Econometric methods were also introduced from economics. Thus, to predict income, sociologists would examine status variables (such as race, ethnicity , or gender) or group affiliations (looking at degree of unionization, whether groups are licensed or unlicensed, and the type of industry, community, or firm involved). Other economic variables tapped by sociologists include human capital (education, training, and experience) and economic segmentation. As a result of his interaction with economists, for example, James S. Coleman was the first sociologist since Parsons to build a comprehensive social theory. Coleman’s Foundations of Social Theory (1990), based on economic models, suggests that the individual makes rational choices in all phases of social life.

What Is Social Stratification, and Why Does It Matter?

How Sociologists Define and Study This Phenomenon

Corbis / Getty Images

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

- Ph.D., Sociology, University of California, Santa Barbara

- M.A., Sociology, University of California, Santa Barbara

- B.A., Sociology, Pomona College

Social stratification refers to the way people are ranked and ordered in society. In Western countries, this stratification primarily occurs as a result of socioeconomic status in which a hierarchy determines the groups most likely to gain access to financial resources and forms of privilege. Typically, the upper classes have the most access to these resources while the lower classes may get few or none of them, putting them at a distinct disadvantage.

Key Takeaways: Social Stratification

- Sociologists use the term social stratification to refer to social hierarchies. Those higher in social hierarchies have greater access to power and resources.

- In the United States, social stratification is often based on income and wealth.

- Sociologists emphasize the importance of taking an intersectional approach to understanding social stratification; that is, an approach that acknowledges the influence of racism, sexism, and heterosexism, among other factors.

- Access to education—and barriers to education such as systemic racism—are factors that perpetuate inequality.

Wealth Stratification

A look at wealth stratification in the U.S. reveals a deeply unequal society in which the top 10% of households control 70% of the nation's riches , according to a 2019 study released by the Federal Reserve. In 1989, they represented just 60%, an indication that class divides are growing rather than closing. The Federal Reserve attributes this trend to the richest Americans acquiring more assets; the financial crisis that devastated the housing market also contributed to the wealth gap.

Social stratification isn't just based on wealth, however. In some societies, tribal affiliations, age, or caste result in stratification. In groups and organizations, stratification may take the form of a distribution of power and authority down the ranks. Think of the different ways that status is determined in the military, schools, clubs, businesses, and even groupings of friends and peers.

Regardless of the form it takes, social stratification can manifest as the ability to make rules, decisions, and establish notions of right and wrong. Additionally, this power can be manifested as the capacity to control the distribution of resources and determine the opportunities, rights, and obligations of others.

The Role of Intersectionality

Sociologists recognize that a variety of factors, including social class , race , gender , sexuality, nationality, and sometimes religion, influence stratification. As such, they tend to take an intersectional approach to analyzing the phenomenon. This approach recognizes that systems of oppression intersect to shape people's lives and to sort them into hierarchies. Consequently, sociologists view racism , sexism , and heterosexism as playing significant and troubling roles in these processes as well.

In this vein, sociologists recognize that racism and sexism affect one's accrual of wealth and power in society. The relationship between systems of oppression and social stratification is made clear by U.S. Census data that show a long-term gender wage and wealth gap has plagued women for decades , and though it has narrowed a bit over the years, it still thrives today. An intersectional approach reveals that Black and Latina women, who make 61 and 53 cents, respectively, for every dollar earned by a white male , are affected by the gender wage gap more negatively than white women, who earn 77 cents on that dollar , according to a report by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Education as a Factor

Social science studies show that one’s level of education is positively correlated with income and wealth. A survey of young adults in the U.S. found that those with at least a college degree are nearly four times as wealthy as the average young person. They also have 8.3 times as much wealth as those who just completed high school. These findings show that education clearly plays a role in social stratification, but race intersects with academic achievement in the U.S. as well.

The Pew Research Center has reported that completion of college is stratified by ethnicity. An estimated 63% of Asian Americans and 41% of whites graduate from college compared to 22% of Blacks and 15% of Latinos. This data reveals that systemic racism shapes access to higher education , which, in turn, affects one's income and wealth. According to the Urban Institute , the average Latino family had just 20.9% of the wealth of the average white family in 2016. During the same timeframe, the average Black family had a mere 15.2% of the wealth of their white counterparts. Ultimately, wealth, education, and race intersect in ways that create a stratified society.

- What's the Difference Between Prejudice and Racism?

- Visualizing Social Stratification in the U.S.

- What You Need to Know About Economic Inequality

- The Concept of Social Structure in Sociology

- The Differences Between Socialism and Communism

- The Racial Wealth Gap

- What Is Radical Feminism?

- How Race and Gender Biases Impact Students in Higher Ed

- What Are Racial Projects?

- Womanist: Definition and Examples

- Understanding Karl Marx's Class Consciousness and False Consciousness

- What Is Feminism Really All About?

- Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge

- How Expectation States Theory Explains Social Inequality

- Defining Racism Beyond its Dictionary Meaning

- Definition of Systemic Racism in Sociology

Brittani Sommer Université libre de Bruxelles Brussel Belgium

Published by IRA Academico Research, a publisher member of the Publishers International Linking Association, Inc. (Crossref), USA.

This paper is reviewed in accordance with the Peer Review Program of IRA Academico Research

Social Stratification: A review of theories and conclusions

Barkow, J. H. (1992). Beneath new culture is old psychology: Gossip and social stratification.

Cole, J. R., & Cole, S. (1973). Social stratification in science. University of Chicago Press.

Hollingshead, A. B., & Redlich, F. C. (1958). Social class and mental illness: Community study.

Kerbo, H. R. (2006). Social stratification.

Lenski, G. E. (1966). Power and privilege: A theory of social stratification. UNC Press Books.

Parsons, T. (1940). An analytical approach to the theory of social stratification.American Journal of Sociology, 841-862.

Parsons, T. (1953). A revised analytical approach to the theory of social stratification. New York.

Rosen, B. C. (1956). The achievement syndrome: A psychocultural dimension of social stratification. American Sociological Review, 203-211.

Tumin, M. M. (1967). Social stratification (Vol. 5). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

(ISSN: 2455-2267)

Reviewed & Published by IRA Academico Research | ©2012-2024, All Rights Reserved.

Social Stratification and Its Principals Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

The issue of the social stratification is a significant one because it implies that in the society, some groups and individuals are not equal. The present study aims to understand the notion of the social stratification and its principals through the review of Tumin’s work “Some Principle of Stratification: A Critical Analysis.” Tumin’s study is a response to the assumption made by Davis and Moore that the several social positions are more important the others because they lead to more efficient functioning of the society.

The social stratification deals with the idea of a place but not an individual who occupies a particular position. Davis and Moore address two primary questions: why some fields are more attractive and distinguished than the others; and how the individuals acquire these occupations.

The necessity of stratification within the positions originates from the operating principles of these occupation fields. Some spaces require the specific knowledge or talents. For example, a doctor in a hospital is vital in comparison with the administrative or unskilled staff. Thus, these kinds of positions such as doctor or engineer are functionally important, and demand particular expertise and responsibilities from the individual and their duties have to be performed “with the diligence that their importance requires” (Tumin 185).

Society, on the other hand, provides the system of rewards associated with the specific occupations. As an illustration, the individuals who hold the doctor position have some “rights” and privileges such as respect and competitive salary. Since some positions have more significant assets then the others, the social stratification contributes to the creation of inequality. Moreover, the status of a job as functional depends on the deficiency of properly trained and talented personnel. Davis and Moore come to the conclusion that the functional necessity of social stratification is irresistible and leads to positive outcomes for the whole society.

Tumin’s assumption refuses the beneficial effects of the stratification on society. Tumin argues that consideration of some positions as more important than the others is unnecessary. From Tumin’s perspective, the previous example of a doctor is inadequate because the functioning of a hospital as a whole system depends on the administration and maintenance personnel as well. Without organized cleaning, lighting, electric and many other systems, patients are in the equal danger as without doctors.

Considering the issue of the talented individuals who represents the limited number of population, Tumin claims that the system of stratified society blocks the process of finding of many talented individuals. According to the author, the phenomenon can be traced in the societies where the new generation depends on the resources of “the parent generation” (Tumin 188). For example, if the education system is not public or merit based, the significant number of the population does not have a chance to reveal their talents.

The sacrifices for a training period and rewards guaranteed by the certain position to the qualified employees are regarded as irrelevant by Tumin. The author does not recognize a trainee period as a sacrifice, but emphasize the privileges which training and education provides for individuals who are in schools in comparison with their peers who have to work and do not have such an opportunity of self-development.

The prestige and privileges that the society ascribes to the specific jobs and individuals who occupy them derive from the inherently one-sided point of view prevailed in the society. Thus, many other positions that are wrongly considered as less attractive and not functional remain underestimated by the society and individuals as well. Tumin’s response to David and Moore’s assumption highlights the unbalance nature of the social stratification and its harmful outcomes for the society.

Tumin, Melvin M. “Some principles of stratification: A critical analysis.” American Sociological Review 18.4 (1953): 387-393.

- Strong Individualism and Its Benefits to Society

- Morality, Faith, and Dignity in Modern Youth

- Social Stratification System in the United States

- Concept of Social Stratification

- Social Stratification and How to Enhance a Social Standing

- Demographic Transition Over Time and Space

- "Elsewhere, U.S.A" by Dalton Conley

- Social Location and Its Role in Social Problems

- Truly Just Society and John Rawls's Principles

- Urban Planning Issues in the "Boyz n the Hood" Film

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)