10 therapy tasks practiced most frequently by survivors of stroke

Stroke can impact all aspects of life—movement, communication, thinking, and autonomic functions such as swallowing and breathing. Research shows that early and specialized stroke rehabilitation can help to optimize an individual’s physical and cognitive recovery and enhance quality of life. Here, we identify the Constant Therapy tasks used most often by those recovering from stroke.

The goal of stroke therapy: help people regain lost skills

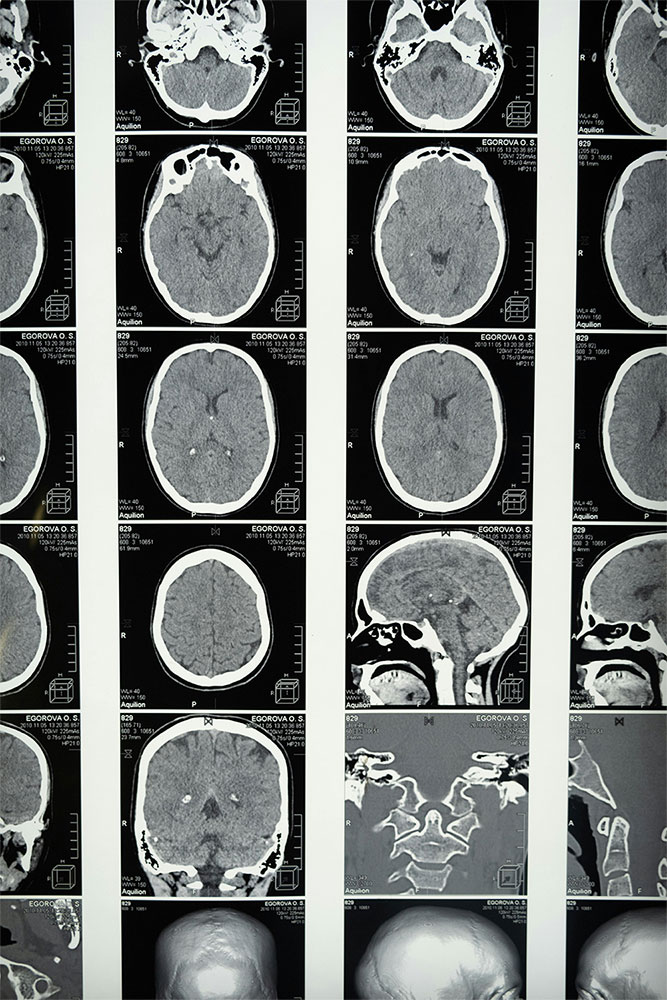

According to the Centers for Disease Control , about 87 percent of all strokes are ischemic strokes, in which blood flow to the brain is blocked. According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, individuals with aphasia or other cognitive-communication issues represent up to 20 percent of the adult caseload for speech-language pathologists in the United States.

Typical goals of stroke therapy include:

- Restoring physical function and enhance the skills needed to perform daily activities

- Building strength, improving balance and regaining mobility

- Improving areas such as speech, language, cognition, or swallowing

- Developing new behavioral or compensatory strategies

Analysis: how is Constant Therapy being used with this population?

Constant Therapy uses artificial intelligence and data analytics to provide each user with a personalized brain exercise program targeting areas such as memory, attention, problem-solving, math, language, reading, writing, and many other skills. Research published in the Journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience showed a significant improvement in standardized tests for survivors of stroke using the iPad-based rehabilitation technology of Constant Therapy.

An analysis of Constant Therapy users identified what tasks are assigned most frequently by clinicians working with survivors of stroke.

- We looked at data on 18,230 users who identified a diagnosis of stroke on the app.

- These 18,230 users completed an average of 572 tasks each

- Total tasks completed numbered 837,700.

The Constant Therapy tasks listed below are the 10 most frequently assigned by clinicians for their clients recovering from stroke.

The top 10 Constant Therapy exercises assigned by clinicians to patients recovering from stroke

1. Follow instructions you hear : Works on auditory memory and auditory comprehension through following directions . Individuals Assigned: 10,207 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke 56%

2. Find the same symbols : Cognitive skills such as attention can be affected after a stroke. Find the same symbols targets a variety of skills which includes attention, visuospatial processing, and executive functioning . Individuals Assigned: 9,216 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 51%

3. Put steps in order : For people recovering from a stroke, executive functioning skills may be affected. In this planning & organizing task , you are presented with steps of daily activities, and must drag these steps into the correct order. This is a great task for people working on sentence level reading comprehension too! Individuals Assigned: 8,814 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 48%

4. Match pictures : For people with cognitive, speech, or language disorders, this task helps visual memory by matching pictures displayed on a grid. For people recovering from a stroke who are working on word retrieval, they can also practice naming the pairs of pictures that they match . Individuals Assigned: 7,629 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 42%

5. Remember pictures in order (N-Back) : This memory task specifically targets an aspect of working memory called updating . There are 3 levels of difficulty. In Level 1, you must remember the order of the pictures from 1 picture ago. In level 3 you must recall 3 pictures ago. Want more N-Back Tasks? Do Remember spoken word order (N-Back) and Remember written words in order (N-back) , too! Individuals Assigned: 7,213 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 40%

6. Do clock math : Stroke can affect number skills, math skills, and word finding. This task helps improve time-based calculation skills by answering math questions associated with clocks . Individuals Assigned: 6,701 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 37%

7. Name Pictures : Helps improve word retrieval skills by speaking the name of presented images. There are 3 levels to this task, with each level increasing in word difficulty. Different cues include semantic, phonemic, graphemic, and whole word cues . Individuals Assigned: 6,635 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 36%

8. Repeat a pattern : This task works on attention, visual working memory, and visuospatial skills . Individuals Assigned: 6,433 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 35%

9. Understand voicemail : This functional task works on comprehension and memory of everyday language by answering questions about voicemails. Looking for a bigger challenge? Check out Infer from voicemail as well . Individuals Assigned: 6,085| Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 33%

10. Remember the right card : This task works on attention, disinhibition, and processing speed. The patient is asked to remember a playing card and tap on that card whenever it is presented in a series of cards . Individuals Assigned: 5,690 Percent of Users Identified As Recovering from Stroke: 31%

- Des Roches, C., Kiran, S. and Balachandran, I. (2015). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, Effectiveness of an impairment-based individualized rehabilitation program using an iPad-based software platform , 2015 Jan 5. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.01015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018). Stroke Facts .

- ASHA (2017). SLP Healthcare Survey: Caseload Characterisics .

Tackle your speech therapy goals, get top-notch support

Related articles, 11 comments.

Do you get this from the App Store? What is the cost?

Hi Lisa. Yes, check out the app store. Our monthly plan is $25 and an annual plan is $250 with a free tablet. If you want to set up a trial and need support, give us a call or email. 1-888-233-1399 or [email protected]

When I purchased a whole year package in 2023 I never received a free tablet. Is this something new?

Hi Todd, thank you so much for subscribing to Constant Therapy! Apologies for the confusion, this is an older comment and we discontinued this program back in 2019. If you have any questions or concerns about the device you use for Constant Therapy feel free to reach out to our Support Team at [email protected] .

What is the app name please?

- Constant Therapy

Thanks have learnt something. Am struggling with after stroke effects especially speech

Is there a way to have the math word problem questions read to you? My brother is working on math as well as re learning reading. He cannot read the questions yet to do the math problem…

Great question! This is a feature that we are working to add in the near future – keep an eye out for announcements in our weekly emails once we have that feature ready to use!

What exercises are recommended for people with primary progressive apraxia?

Hello Alberta, thank you for your question! We spoke with a Speech Language Pathologist and they said that difficulty levels will depend on the condition’s progression. You may be interested at looking into these exercises: Imitate Words, Imitate Sentences, Form and Say Active Sentences, and Form and Say Passive Sentences . These tasks will allow you practice with articulating speech at various levels of complexity. Hope this is helpful!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Constant Therapy Health

- Partner with us

- Try for free

- Request a Demo

- Conditions we support

- For clinicians

- For patients

- For veterans

Support + Resources

- Printable Resources

- Testimonials

Join the Conversation

Science of mind

Boosting Cognition: Memory Exercises for Stroke Patients

Did you know that more than half of all stroke survivors experience post-stroke cognitive impairment? This impairment can affect memory, problem-solving skills, and clear thinking. Fortunately, cognitive exercises tailored for stroke patients can help improve mental aptitude and aid in recovery.

Key Takeaways

- Stroke survivors often experience post-stroke cognitive impairment, affecting memory and cognitive skills.

- Cognitive exercises tailored for stroke patients can help improve mental aptitude and aid in recovery.

- Various memory exercises, puzzles, games, art therapy, and cognitive therapy apps can support cognitive improvement.

- Consistency and repetition are crucial for promoting neuroplasticity and maximizing stroke recovery.

- Working with a speech-language pathologist can provide personalized guidance for optimal recovery.

How can a stroke affect cognition?

A stroke can have profound effects on cognitive function, impacting various aspects of a person’s mental abilities. Commonly referred to as post-stroke cognitive impairment, these changes can significantly impact memory, problem-solving, attention, language, and perception skills.

One of the key challenges faced by stroke survivors is the difficulty in performing daily activities and fulfilling their roles due to these cognitive impairments. The severity and type of cognitive changes experienced after a stroke can vary depending on the specific area of the brain affected by the stroke.

Memory is often one of the cognitive skills most affected by a stroke.Stroke affects cognition and can lead to difficulties in forming new memories or recalling previously learned information. In addition, problem-solving skills may be impaired, making it challenging to navigate complex tasks and find solutions to everyday problems.

Attention may be compromised, resulting in difficulty staying focused on tasks or maintaining concentration for extended periods. Language and communication skills may also be affected, making it harder to express thoughts and understand others. Perception skills, such as spatial awareness or recognizing objects, may be altered as well.

All of these cognitive changes can have a significant impact on a stroke survivor’s ability to perform daily activities, affecting their independence and overall quality of life. However, it’s important to note that every stroke survivor’s experience with cognitive impairment is unique, and the specific cognitive effects can vary from person to person.

Understanding how a stroke can affect cognition is essential for caregivers, healthcare professionals, and stroke survivors themselves. By recognizing the cognitive challenges that may arise after a stroke, appropriate interventions and rehabilitation strategies can be implemented to help individuals regain and enhance their cognitive skills.

The Domino Effect of Cognitive Impairment

It’s important to note that these cognitive changes can create a domino effect, impacting various areas of a stroke survivor’s life. Difficulties in memory, problem-solving, attention, language, and perception abilities can make it challenging to perform tasks that were once routine and effortless.

Simple activities like cooking a meal, managing finances, or even engaging in conversations with loved ones can become immensely challenging. The frustration and limitations imposed by these cognitive impairments can contribute to emotional distress and a decreased sense of self-worth.

Recognizing the breadth of cognitive effects after a stroke is essential in providing appropriate support for stroke survivors. Through targeted cognitive exercises and rehabilitation strategies, individuals can work towards improving their cognitive skills and achieving a higher level of independence and quality of life.

- American Stroke Association. (2019). Emotions After Stroke Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://www.stroke.org/sites/default/files/resources/ASAEmotionsafterStroke.pdf .

- Feddermann-Demont, N., & Seeherman, H. (2020). Cognitive Impairment After Stroke. Frontiers in Neurology, 11. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.593427

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2019). Post-Stroke Rehabilitation Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Post-Stroke-Rehabilitation-Fact-Sheet .

- University of California, San Francisco, Stroke Center. (n.d.). Cognition. Retrieved from http://www.strokecenter.org/patients/stroke-treatment/cognitive-function/ .

Cognitive exercises for stroke patients

When it comes to stroke recovery, cognitive exercises play a crucial role in improving cognitive skills for stroke patients. These exercises encompass a range of activities that stimulate different areas of the brain and promote overall cognitive function. Here are some effective cognitive exercises that can support stroke patients in their recovery journey:

1. Memory Games for Stroke Survivors

Memory games are an excellent way to enhance memory retention and recall abilities. Engaging in memory games like matching cards, word association, or recalling lists can help stroke patients exercise their memory skills and improve cognitive functioning.

2. Analytical Reasoning Exercises

Analytical reasoning exercises involve critical thinking and problem-solving. Puzzles, Sudoku, and logical thinking games challenge stroke patients’ cognitive abilities in terms of analysis, deduction, and decision-making.

3. Quantitative Reasoning Exercises

Quantitative reasoning exercises focus on numerical concepts and calculations. Working with numbers, solving math problems, or playing educational math games can help stroke survivors regain their numerical reasoning abilities and improve cognitive processing.

4. Brain Teasers for Stroke Patients

Brain teasers, such as riddles or mind-bending puzzles, provide an enjoyable way to stimulate cognitive function. These exercises encourage creative thinking, enhance problem-solving skills, and promote cognitive agility.

5. Visuospatial Processing Activities

Visuospatial processing activities involve interpreting and mentally manipulating visual information. Examples include assembling puzzles, drawing, or playing spatial awareness games. These exercises can significantly improve visuospatial skills and enhance overall cognitive performance.

6. Memory Enhancement Games

Memory enhancement games specifically target memory retention and recall. Activities like memory matching games, word recall exercises, or digital memory training apps can help stroke survivors strengthen their memory abilities and boost cognitive function.

7. Cognitive Therapy Apps for Stroke Patients

Cognitive therapy apps provide a structured and convenient way for stroke patients to engage in targeted cognitive exercises. From memory games to problem-solving tasks, these apps offer a wide range of activities designed to support cognitive rehabilitation and recovery.

8. Mindfulness Exercises for Stroke Survivors

Mindfulness exercises, such as meditation or deep breathing techniques, can have profound benefits for stroke survivors. These exercises improve focus, attention, and reduce stress, thereby enhancing cognitive functioning and promoting overall well-being.

By incorporating these cognitive exercises into stroke rehabilitation programs, healthcare professionals can empower their patients to regain cognitive abilities and improve their overall quality of life. Whether through games, puzzles, or mindfulness practices, these exercises offer valuable opportunities for cognitive enhancement and recovery.

Importance of cognitive exercises for recovery

Consistently practicing cognitive exercises is crucial for stroke recovery. When the brain is affected by a stroke, it can lead to various cognitive impairments such as memory loss, attention difficulties, and problems with problem-solving skills. However, by engaging in targeted cognitive exercises, stroke survivors can significantly improve their cognitive function and overall quality of life.

One of the key benefits of cognitive exercises is their ability to promote neuroplasticity, the brain’s remarkable capacity to reorganize and form new neural connections. Neuroplasticity plays a crucial role in stroke recovery as it allows the brain to heal itself and rewire damaged areas. Through consistent practice, cognitive exercises stimulate the creation of new neural networks, enabling the brain to compensate for areas affected by the stroke and improve cognitive function.

Cognitive rehabilitation after a stroke is essential for helping patients regain their independence, improve their cognitive abilities, and enhance overall well-being. By engaging in targeted exercises, stroke survivors can focus on specific cognitive domains, such as memory, attention, language, and problem-solving, addressing the areas most affected by the stroke.

“Cognitive exercises improve cognitive function, enhance problem-solving skills, and promote overall brain health after a stroke.” – Dr. Emily Johnson, Neurologist

One of the significant advantages of cognitive exercises is their versatility. There are various types of exercises that stroke survivors can engage in, including memory games, puzzles, problem-solving activities, and virtual cognitive therapy apps. These exercises can be tailored to the individual’s specific needs and abilities, ensuring a personalized approach to recovery.

Cognitive exercises also offer a sense of empowerment and control over one’s recovery journey. By actively engaging in cognitive rehabilitation, stroke survivors can take an active role in healing their brains and improving their cognitive abilities. This sense of agency can have a positive impact on mental and emotional well-being, further enhancing the recovery process.

Benefits of Cognitive Exercises for Stroke Patients:

- Improved memory retention and recall

- Enhanced problem-solving and analytical thinking

- Increased attention and concentration

- Improved language and communication skills

- Enhanced ability to perform daily activities independently

- Increased confidence and self-esteem

By incorporating cognitive exercises into the rehabilitation process, stroke patients can improve their cognitive abilities, regain independence, and enhance their overall well-being.

Next, we’ll explore the benefits of board games, puzzles, and art therapy in cognitive rehabilitation for stroke patients.

| Exercise Type | Benefits |

|---|---|

| Memory games | Improves memory retention and recall abilities |

| Problem-solving activities | Enhances analytical thinking and logical reasoning skills |

| Puzzles | Improves cognitive function and hand-eye coordination |

| Virtual cognitive therapy apps | Provides a structured approach to cognitive rehabilitation |

| Art therapy | Promotes creativity, emotional expression, and cognitive improvement |

Board games, puzzles, and art therapy

When it comes to cognitive exercises for stroke patients, board games, puzzles, and art therapy can offer a variety of benefits. These engaging activities not only provide entertainment but also promote cognitive function and overall well-being.

Playing board games is an enjoyable way to stimulate concentration, memory, problem-solving, and analytical thinking. Whether it’s classic games like Chess or Scrabble, or more modern options like Settlers of Catan or Ticket to Ride, these games challenge the brain and encourage strategic thinking.

Puzzles, such as crosswords, Sudoku, or jigsaw puzzles, are particularly beneficial for stroke survivors. These activities enhance short-term memory and improve hand-eye coordination. Additionally, solving puzzles provides a sense of accomplishment and can boost confidence.

Another valuable cognitive exercise for stroke patients is art therapy. Engaging in art activities, such as drawing, painting, or crafting, promotes creativity, analytical skills, and emotional expression. It can serve as a therapeutic outlet for managing stress and enhancing cognitive function.

Art therapy for stroke recovery allows individuals to explore their feelings, memories, and thoughts through a creative medium. This form of therapy encourages the use of different senses and can help stimulate neural pathways in the brain.

The Benefits of Board Games, Puzzles, and Art Therapy

1. Cognitive Stimulation: Board games, puzzles, and art therapy provide opportunities for cognitive stimulation, improving memory, problem-solving skills, and analytical thinking.

2. Emotional Well-being: Engaging in these activities can boost mood, reduce stress, and promote a sense of accomplishment and self-esteem.

3. Social Interaction: Playing board games and solving puzzles can be enjoyed with family or friends, promoting social interaction and connection.

4. Rehabilitation: Board games, puzzles, and art therapy are effective rehabilitation tools that can help stroke patients regain cognitive function and improve overall well-being.

5. Enjoyment and Entertainment: These activities provide enjoyable and fulfilling experiences, making cognitive exercises more engaging and motivating.

| Board Games | Puzzles | Art Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulates concentration and memory. | Enhances short-term memory and hand-eye coordination. | Promotes creativity and emotional expression. |

| Improves problem-solving and analytical thinking. | Provides a sense of accomplishment and self-esteem. | Facilitates cognitive stimulation and neural pathway development. |

| Encourages social interaction and connection. | Reduces stress and promotes relaxation. | Offers a therapeutic outlet for managing emotions. |

Brain teasers and cognitive therapy apps

Brain teasers can be an enjoyable and effective way for stroke patients to engage their cognitive abilities and promote mental acuity. Activities such as crossword puzzles, word searches, and Sudoku are not only mentally stimulating but also help improve analytical thinking, problem-solving, and quantitative reasoning skills. These brain teasers challenge the brain to make connections, think critically, and strategize, enabling stroke patients to exercise and strengthen their cognitive functions.

However, it’s not just traditional paper-based brain teasers that can benefit stroke recovery. Cognitive therapy apps have become increasingly popular in providing a convenient and accessible platform for engaging in cognitive exercises. These apps offer a range of therapeutic games and activities specifically designed for stroke patients. They target various cognitive skills, including memory, visual/spatial processing, and reasoning.

Cognitive therapy apps for stroke recovery often include beneficial features such as progress tracking, personalized exercises, and adaptive difficulty levels. These features provide stroke patients with the ability to monitor their progress, receive tailored exercises that suit their cognitive needs, and challenge themselves as they progress in their recovery journey.

By integrating brain teasers and cognitive therapy apps into their rehabilitation regimen, stroke patients can engage their minds, enhance their cognitive abilities, and promote neuroplasticity. These activities not only facilitate recovery but also provide enjoyable and challenging experiences that positively impact overall well-being.

Example Brain Teasers:

- Crossword puzzles

- Word searches

Cooking and mindfulness exercises

Cooking can be a delightful and therapeutic activity that offers numerous benefits for cognitive improvement in stroke recovery. Following a recipe and engaging in the culinary process stimulates various cognitive skills, including sequencing, memory, and problem-solving.

When preparing a meal, you need to follow instructions step by step, which enhances your ability to organize tasks, remember ingredients, and recall the order of actions. This sequencing practice can improve your memory retention and cognitive flexibility.

“Cooking allows me to engage my brain in a creative and purposeful way. It helps me focus on the task at hand and boosts my confidence as I see the end result of my efforts.” – Sarah, stroke survivor

Mindfulness exercises are another valuable practice for stroke recovery. Whether through guided apps or simple present-moment awareness, mindfulness exercises can promote relaxation and have a positive impact on cognitive function.

During these exercises, you pay attention to your thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations without judgment or attachment. This process helps improve attention, mental flexibility, and information processing, which are essential for cognitive improvement after a stroke.

By engaging in both cooking and mindfulness exercises, you not only promote cognitive growth but also create a nurturing environment for relaxation and well-being.

Benefits of Cooking after a Stroke:

- Enhances sequencing and memory skills

- Improves problem-solving abilities

- Promotes cognitive flexibility

- Boosts confidence and self-esteem

- Provides a creative outlet

- Increases engagement in daily activities

The role of consistency and neuroplasticity in stroke recovery

Consistency is vital when it comes to cognitive exercises for stroke recovery. By consistently practicing cognitive exercises, stroke survivors can promote neuroplasticity, which is the brain’s ability to form new neural pathways and heal from damage. Regular and ongoing engagement in cognitive exercises, both during therapy sessions and at home, can lead to lasting improvements in cognitive function.

Neuroplasticity plays a crucial role in the brain’s ability to heal and adapt after a stroke. Through consistent practice, stroke survivors can stimulate the brain’s natural healing processes and promote the development of new neural connections. This process allows the brain to compensate for the areas affected by the stroke, enabling individuals to regain lost cognitive skills and improve overall functioning.

Repetition is a key component in cognitive exercises for stroke recovery. By repeating specific tasks and exercises, stroke survivors can reinforce and strengthen the neural pathways associated with those skills. This repetition helps the brain to reorganize and rebuild connections, enhancing the recovery process and facilitating the restoration of cognitive abilities.

Working with a speech-language pathologist can provide stroke survivors with personalized guidance and treatment plans for optimal recovery. These professionals can design a tailored cognitive exercise regimen that targets specific areas of improvement and ensures consistency in practice. The speech-language pathologist will monitor progress and make adjustments as needed to maximize the benefits of cognitive exercises and promote neuroplasticity.

Source Links

- https://www.healthline.com/health/stroke-treatment-and-timing/brain-exercises-for-stroke-recovery

- https://www.flintrehab.com/best-cognitive-exercises-for-stroke-patients/

- https://gleneagles.com.my/articles/12-good-brain-exercises-for-stroke-recovery

Similar Posts

How bad can memory loss get with fibromyalgia?

Can BPPV Cause Memory Loss? Understanding Risks

How to talk to someone with short term memory loss?

Exploring Music Therapy for Memory Loss Benefits

Does Mounjaro Cause Memory Loss? My Insights

Why does dory have memory loss?

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Coping With Stroke

Frequently asked questions.

- Next in Stroke Guide Everything You Should Know About Stroke

Everyone has a different way of coping after stroke . While some effects of a stroke may be immediately apparent and, perhaps with therapy, relatively short-lived, others may take months or even years to develop and could be long-lasting.

Having support and getting proper rehabilitation from your care team is essential to making your post-stroke life as good as possible. In addition to physical, occupational, and speech therapy, coping can involve talk therapy with a psychologist or social worker and support groups—online or in-person.

Verywell / Ellen Lindner

Sadness, anxiety, anger, and grief are all common responses to a stroke. This can be due to physical or biochemical changes in the brain as well as the emotional response to post-stroke life.

Talk to your healthcare provider about your emotional health and any changes in mood or behavior, as it may be a serious side effect of the stroke. Medications and treatments may be able to help you. Your practitioner might also recommend that you see a mental health professional for specialized treatment.

Different psychological approaches for treating post-stroke emotional disorders include:

- Solution-focused therapy (SFT)

- Problem-solving therapy (PST)

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

- Attitude and commitment therapy (ACT)

- Interpersonal therapy

- Mindfulness therapy, also called mindfulness-based cognitive therapy

Group therapy can also be helpful and many people find the social interaction of a group helps to relieve feelings of isolation following a stroke.

Many people go through a grieving process after a stroke. As you begin to come to terms with new limitations and mourn the loss of your life before stroke, you may experience periods of denial, anger, bargaining, and depression before finally coming to acceptance . This is perfectly normal.

Journaling, talking with a friend, or seeing a therapist can help your emotional healing.

Self-Esteem

The effects of stroke can also challenge your self-esteem. For example, it can be especially hard on you if the stroke has impaired your mobility and limited your independence—affecting, perhaps, what formerly made you feel like a confident individual.

Be gentle with yourself, avoid being self-critical, and try to reframe negative self-talk with positive thoughts.

Behavioral and Personality Changes

After a stroke, new behaviors can include a lack of inhibition, which means that people may behave inappropriately or childlike. Other changes in behavior include a lack of empathy , loss of sense of humor, irrational jealousy , and anger. Talk to your healthcare provider about these changes in behavior, as there may be medications that can help.

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA), also known as emotional lability, reflex crying, and involuntary emotional expression disorder, is more common following a brainstem stroke . In PBA, there is a disconnect between the parts of the brain that control emotions and reflexes.

People with PBA may briefly cry or laugh involuntarily, without an emotional trigger, and in ways that are not appropriate to the situation.

While there are helpful PBA medications and strategies, such as preventing episodes with deep breathing, distractions, or movement, some people find simply alerting those around them in advance can help reduce embarrassment and make it easier to cope.

Depression is common after a stroke, with some studies saying about 25% of stroke survivors become depressed and other estimates putting that number as high as 79%.

Stroke survivors are twice as likely to attempt suicide as the general population. If you are having suicidal thoughts, dial 988 to contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline and connect with a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911 ..

Treating depression with a combination of medication, talk therapy, and group support may improve your mood and also boost physical, cognitive and intellectual recovery.

Clinical Guidelines: Post-Stroke Depression

The American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association jointly recommend periodic reassessment of depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric symptoms in stroke survivors to help improve outcomes. Medications, therapy, and patient education about stroke can all be helpful.

Coping with physical limitations after a stroke can be a struggle. While many of these challenges will improve over time, it can help to know what you can expect during recovery and where to turn for help.

Many long-term physical complications from a stroke can be helped with therapies, while others may be managed with medication or adaptive technologies and other tools that can help improve independence and quality of life.

Most of the time, weakness caused by a stroke affects one side of the body, known as hemiparesis. This commonly affects the face, arm, or leg or a combination of the three. While the weakness may linger long-term, physical therapy can help you to regain strength, and occupational therapy can help you develop alternative strategies for everyday activities.

Many stroke survivors report feeling off-balance, dizzy, light-headed, or as if the room is spinning. These sensations may come and go but may eventually stabilize. Physical therapy is the most effective way to combat balance impairment after a stroke. Your therapist can show you safe, at-home balance exercises or yoga poses to improve balance and combat dizziness.

Vision Changes

Vision problems that may result from a stroke include:

- Double vision (diplopia)

- Visual field loss (hemianopsia )

- Jerking of the eyes (nystagmus)

- Loss of vision

Ophthalmologists and occupational therapists can advise you on the best method to manage vision changes, including therapy to compensate for vision loss, prism lenses, sunglasses, an eye patch, or eye drops.

Communication Problems

Difficulty speaking or understanding words is one of the most well-known results of a stroke and among the most impactful.

Speech-language therapy can help people cope with aphasia (which is trouble speaking or understanding words due to a disease or an injury of the brain) and dysarthria (difficulty articulating words due to muscle weakness or diminished coordination of face and mouth muscles).

Cognitive Deficits

Cognitive changes after a stroke include memory glitches, trouble solving problems, and difficulty understanding concepts. While the severity varies from one stroke survivor to another, research shows cognitive remediation can help significantly.

These interventions include exercises to improve memory, processing speed, and attention, and teaching compensatory strategies, such as making lists and keeping a planner.

Hemispatial Neglect

A stroke on one side of the brain can lead to difficulties with the field of vision or movement on the other side of the body, known as hemispatial neglect. For example, a stroke in the right cerebral cortex can lead to the diminished ability to notice and use the left side of the body.

Depending on the part of the body affected, an optometrist, neuropsychologist, or physical or occupational therapist can help you cope with hemispatial neglect.

Many stroke survivors experience new-onset pain after a stroke. Common locations for post-stroke pain include:

- Muscles (widespread or in a small area)

Rest, physical therapy, and medication can help you to cope with the pain. Post-stroke headaches require special attention from your healthcare provider, but they can improve with the right treatment.

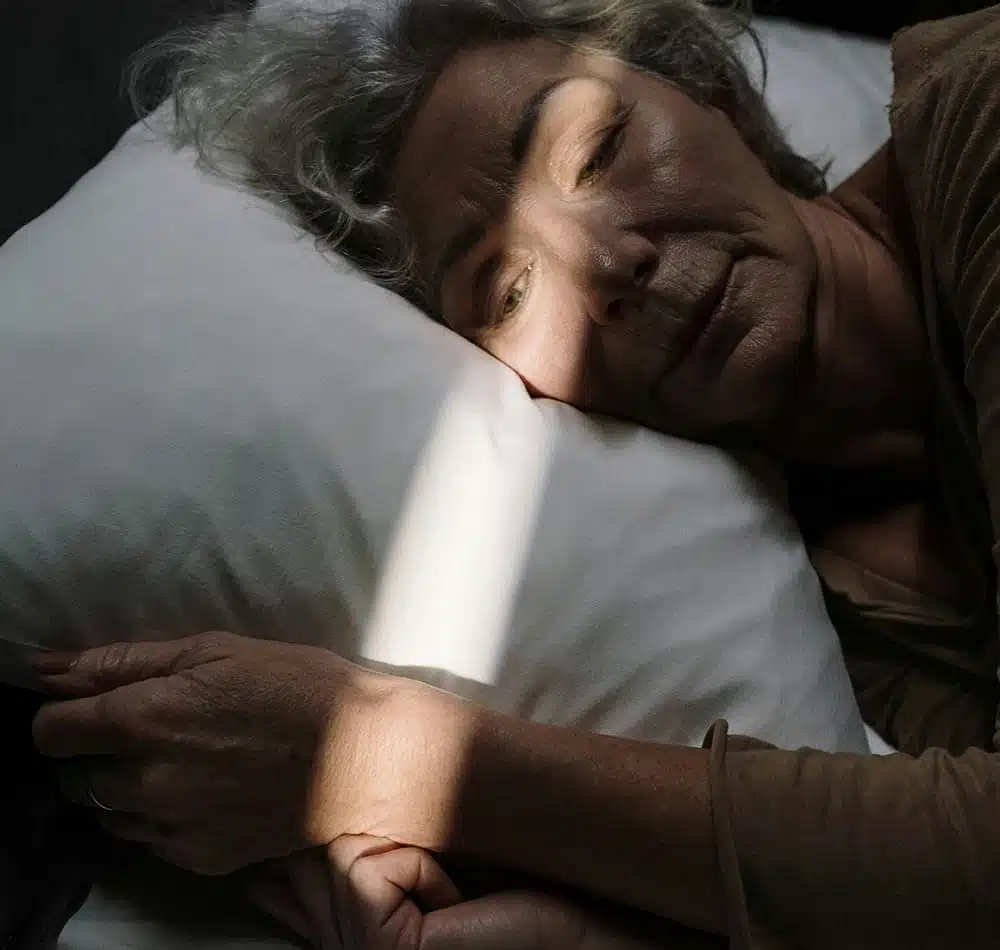

Fatigue and Sleeping Problems

In studies, up to half of stroke survivors report experiencing long-term fatigue following a stroke. For some, this manifests as excessive sleep or the inability to feel rested, while others wake in the middle of the night, have difficulty falling or staying asleep, and nap sporadically throughout the day.

These problems may be due to the stroke itself or a secondary cause, such as depression, pain, or nutritional deficiencies. If you experience fatigue or trouble sleeping, talk to your healthcare provider, who can run additional tests, prescribe medication for insomnia, or offer other strategies to help you cope.

Swallowing Difficulties

A speech and swallow evaluation can identify problems with chewing and swallowing , a common stroke complication known as dysphagia. Most patients see improvement within the first few weeks after a stroke. However, swallowing problems can be quite dangerous.

Choking due to stroke-induced muscle weakness may cause serious illness, such as aspiration pneumonia or even life-threatening breathing obstruction and infection problems. Feeding therapy may help you to regain the ability to swallow safely, although some patients may require a feeding tube to get adequate nutrition.

Trouble With Urination

After a stroke, many stroke survivors experience incontinence , which is urinating when you do not want to. Some stroke survivors also experience bladder retention , which is the inability to urinate on demand. Both of these problems can be managed with medical treatment and physical therapy.

Urination problems can be embarrassing and inconvenient. Discrete bladder-leak protection products like pads for both men and women, disposable underwear, and leak-proof underwear can help you feel more confident going out in public.

Muscle Atrophy

Post-stroke muscle weakness can lead to a lack of movement. A recent stroke patient may need assistance getting up and around in the days following a stroke, and staying in bed too long can result in the muscles shrinking and becoming weaker.

Muscle atrophy can be prevented through pre-emptive post-stroke rehabilitation methods that engage weakened muscles before they shrink. It is difficult to recover from muscle atrophy, but rehabilitation techniques can help improve the situation and slowly rebuild muscle.

Muscle Spasticity

Sometimes weakened muscles become stiff and rigid after a stroke, possibly even jerking on their own. Muscle spasticity and rigidity is often painful and can result in diminished motor control of the already weakened muscles.

Active post-stroke rehabilitation can prevent this, and there are a number of effective medical treatments. Your physical therapy team can provide exercises you can do throughout the day at home to prevent and ease spasticity.

Some people experience post-stroke seizures due to erratic electrical brain activity. Seizure prevention may be part of the post-stroke care program, and seizures are typically managed with medication. Cortical stroke survivors are at especially high risk of developing seizures years later.

Whether your stroke left you with minor physical limitations, speech difficulties, or serious mobility challenges, many people feel isolated after a stroke. Getting back into the stream of life can take time.

Many patients and caregivers find that joining a support group can offer both social engagement and emotional support. Your local hospital or rehabilitation center likely hosts a regular support group, or you can check the American Stroke Foundation's website .

For people with limited mobility, joining an online support group that holds regular online meetings, a Facebook community group, or message boards to talk with other stroke survivors and caregivers can be a lifeline keeping you connected to others. Online support is available through the Stroke Network .

The after-effects of a stroke can present unique individual challenges. Lingering weakness, mobility challenges, difficulty communicating, and visual problems can lead to a lack of independence.

Help With Daily Living

Depending on the degree of your stroke, you may require help with activities of daily living, including cooking, cleaning, and grooming. In some cases, family members step up to help, while others may require a visiting nurse, a part-time aide, or even live-in help like a housekeeper, companion, or nurse.

Some people choose to move to retirement complexes that provide varying levels of care or assisted living facilities.

Getting Around

Some people lose the ability to drive and experience other physical changes that make it difficult to get around. Some stroke survivors find getting a mobility scooter can help them get out in the world independently.

Many communities offer senior or disability buses to help you go shopping or offer car services to bring you to your healthcare provider and therapy appointments. You can also use a ride service like Uber or call a taxi to get from place to place.

Roughly one-quarter of strokes occur in people who have not yet retired. If you are working full-time at the time of your stroke, you should be able to apply for temporary disability until you are able to resume working.

If the stroke has left you with minor impairments, but you can still perform some of your former duties, the American Stroke Association recommends entering into a Reasonable Accommodations Agreement with your employer. If you are unable to work, you may qualify for long-term disability through Social Security .

You may find the quickest improvements happen in the three or four months after the stroke. Recovery may continue for one or two years afterward.

According to the American Stroke Association, 10% of stroke survivors recover almost completely, about 25% recover with minor impairments, and 40% have moderate to severe impairments. Another 10% need care in a long-term care facility.

American Stroke Association. Emotional & behavioral effects of stroke .

Wichowicz HM, Puchalska L, Rybak-Korneluk AM, Gąsecki D, Wiśniewska A. Application of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) in individuals after stroke . Brain Inj . 2017;31(11):1507–1512. doi:10.1080/02699052.2017.1341997

Visser MM, Heijenbrok-Kal MH, Van't Spijker A, Lannoo E, Busschbach JJ, Ribbers GM. Problem-solving therapy during outpatient stroke rehabilitation improves coping and health-related quality of life: Randomized controlled trial . Stroke . 2016;47(1):135–142. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010961

Wang SB, Wang YY, Zhang QE, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for post-stroke depression: A meta-analysis . J Affect Disord . 2018;235:589–596. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.011

American Stroke Association. Post stroke mood disorders .

Renner CIe, Outermans J, Ludwig R, Brendel C, Kwakkel G, Hummelsheim H. Group therapy task training versus individual task training during inpatient stroke rehabilitation: A randomised controlled trial . Clin Rehabil . 2016;30(7):637–648. doi:10.1177/0269215515600206

American Stroke Association. Grief and acceptance .

American Stroke Association. Self esteem post stroke .

American Stroke Association. Personality changes post stroke .

American Stroke Association. Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) .

Hadidi NN, Huna Wagner RL, Lindquist R. Nonpharmacological treatments for post-stroke depression: An integrative review of the literature . Res Gerontol Nurs . 2017;10(4):182–195. doi:10.3928/19404921-20170524-02

Mohd Zulkifly MF, Ghazali SE, Che Din N, Singh DK, Subramaniam P. A review of risk factors for cognitive impairment in stroke survivors . Scientific World Journal . 2016;2016:3456943. doi:10.1155/2016/3456943

Winstein CJ, Stein J, Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association . Stroke . 2016 Jun;47(6):e98-e169. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000098.

Stroke Association. Physical effects of stroke .

van Duijnhoven HJ, Heeren A, Peters MA, et al. Effects of exercise therapy on balance capacity in chronic stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis . Stroke . 2016;47(10):2603–2610. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013839

American Stroke Association. Visual disturbances .

Stroke Foundation. Vision loss after stroke fact sheet .

Brady MC, Kelly H, Godwin J, Enderby P, Campbell P. Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke . Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2016;(6):CD000425. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4

Spencer KA, Brown KA. Dysarthria following stroke . Semin Speech Lang . 2018;39(1):15–24. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1608852

Virk S, Williams T, Brunsdon R, Suh F, Morrow A. Cognitive remediation of attention deficits following acquired brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis . NeuroRehabilitation . 2015;36(3):367-77. doi:10.3233/NRE-151225

Scholarpedia: The peer-reviewed open-access encyclopedia. Hemineglect .

American Stroke Association. Coping with pain .

Stroke Foundation. Pain after stroke fact sheet .

Paolucci S, Iosa M, Toni D, et al. Prevalence and time course of post-stroke pain: A multicenter prospective hospital-based study . Pain Med . 2016;17(5):924–930. doi:10.1093/pm/pnv019

Harriott AM, Karakaya F, Ayata C. Headache after ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis . Neurology . 2019; doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000008591

Stroke Association. Fatigue after stroke .

González-Fernández M, Ottenstein L, Atanelov L, Christian AB. Dysphagia after stroke: An overview . Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep . 2013;1(3):187–196. doi:10.1007/s40141-013-0017-y

Rofes L, Arreola V, Almirall J, et al. Diagnosis and management of oropharyngeal dysphagia and its nutritional and respiratory complications in the elderly . Gastroenterol Res Pract . 2011;2011:818979. doi:10.1155/2011/818979

Stroke Foundation. Incontinence after stroke fact sheet .

Scherbakov N, Doehner W. Sarcopenia in stroke-facts and numbers on muscle loss accounting for disability after stroke . J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle . 2011;2(1):5–8. doi:10.1007/s13539-011-0024-8

Bethoux F. Spasticity management after stroke . Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am . 2015;26(4):625–639. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2015.07.003

Graham NS, Crichton S, Koutroumanidis M, Wolfe CD, Rudd AG. Incidence and associations of poststroke epilepsy: the prospective South London Stroke Register . Stroke . 2013;44(3):605–611. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000220

Wang G, Jia H, Chen C, et al. Analysis of risk factors for first seizure after stroke in Chinese patients . Biomed Res Int . 2013;2013:702871. doi:10.1155/2013/702871

American Stroke Association. 15 things caregivers should know after a loved one has had a stroke .

American Stroke Association. Rehab therapy after a stroke .

American Stroke Association. Reasonable accommodations agreement .

Mohd Zulkifly MF, Ghazali SE, Che Din N, Singh DK, Subramaniam P. A Review of risk factors for cognitive impairment in stroke survivors . Scientific World Journal . 2016;2016:3456943. doi:10.1155/2016/3456943

Oh H, Seo W. A comprehensive review of central post-stroke pain . Pain Management Nursing . 2015;16(5):804-18. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2015.03.002

By Heidi Moawad, MD Dr. Moawad is a neurologist and expert in brain health. She regularly writes and edits health content for medical books and publications.

The effectiveness of problem solving therapy for stroke patients: Study protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial

- BMC Neurology 13(1):67

- Erasmus MC & Rijndam Rehabilitation Center, Rotterdam

- Erasmus University Rotterdam

- Erasmus University MC

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- HEALTH QUAL LIFE OUT

- Andrew Lloyd

- Vincent Thijs

- Hubert M Wichowicz

- Lidia Puchalska

- Martyna Puchalska

- COCHRANE DB SYST REV

- Katherine Laura Cox

- Chia-Lin Koh

- Debbie V. Summers

- Maria E. A. Armento

- R G Robinson

- David J Moser

- PSYCHOL MED

- THE WHOQOL GROUP

- Roijen van L

- Marianne Donker

- APPL PSYCH MEAS

- Lenore Sawyer Radloff

- Deanne Hawkins

- C.H. Vaartjes

- Frank L J Visseren

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Study protocol

- Open access

- Published: 27 June 2013

The effectiveness of problem solving therapy for stroke patients: study protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial

- Marieke M Visser 1 , 2 ,

- Majanka H Heijenbrok-Kal 1 , 2 ,

- Adriaan van ’t Spijker 3 ,

- Gerard M Ribbers 1 , 2 &

- Jan JV Busschbach 3

BMC Neurology volume 13 , Article number: 67 ( 2013 ) Cite this article

6804 Accesses

10 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

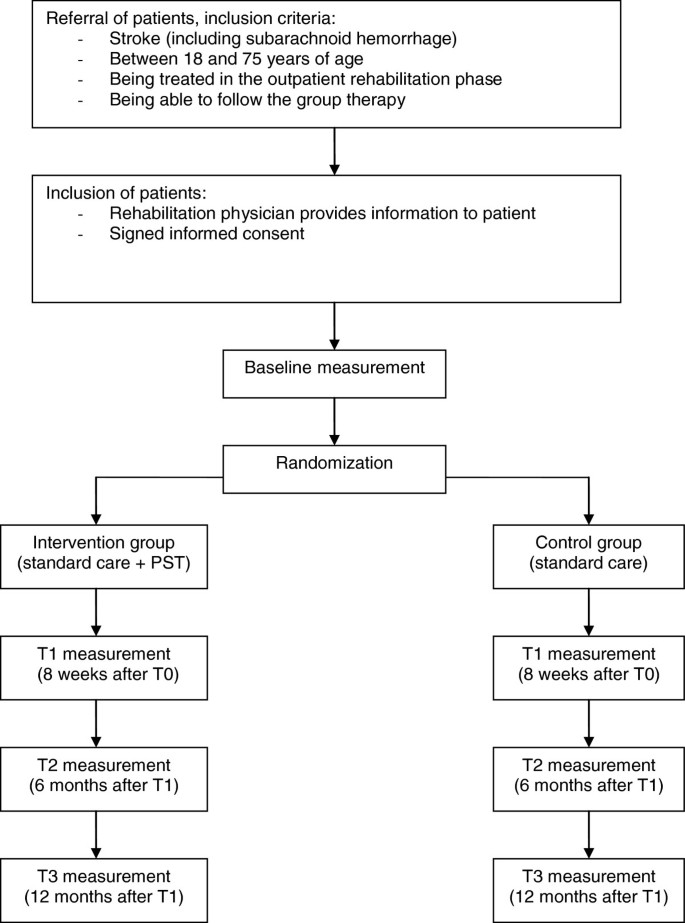

Coping style is one of the determinants of health-related quality of life after stroke. Stroke patients make less use of active problem-oriented coping styles than other brain damaged patients. Coping styles can be influenced by means of intervention. The primary aim of this study is to investigate if Problem Solving Therapy is an effective group intervention for improving coping style and health-related quality of life in stroke patients. The secondary aim is to determine the effect of Problem Solving Therapy on depression, social participation, health care consumption, and to determine the cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Methods/design

We strive to include 200 stroke patients in the outpatient phase of rehabilitation treatment, using a multicenter pragmatic randomized controlled trial with one year follow-up. Patients in the intervention group will receive Problem Solving Therapy in addition to the standard rehabilitation program. The intervention will be provided in an open group design, with a continuous flow of patients. Primary outcome measures are coping style and health-related quality of life. Secondary outcome measures are depression, social participation, health care consumption, and the cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

We designed our study as close to the implementation in practice as possible, using a pragmatic randomized trial and open group design, to represent a realistic estimate of the effectiveness of the intervention. If effective, Problem Solving Therapy is an inexpensive, deliverable and sustainable group intervention for stroke rehabilitation programs.

Trial registration

Nederlands Trial Register, NTR2509

Peer Review reports

Stroke is an increasing public health problem in the Netherlands: every year, 41,000 people suffer from stroke and over 3% of the total health care costs are related to the treatment of stroke and its consequences [ 1 ]. The mortality rate after stroke is 30% and is likely to decrease, which will cause an increase in morbidity [ 2 ]. Almost 50% of stroke survivors experience consequences in daily life that result in a lowered health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) [ 1 ]. The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) Group defines quality of life as “individuals’ perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns [ 3 ]. HR-QoL refers to the health-related aspects of quality of life. On average, utility scores of HR-QoL after stroke range from 0.47 to 0.68 (a utility score equal to death is 0.0 and full health 1.0), which is substantially lower than the value of a healthy reference population (utility score of 0.93) [ 4 , 5 ]. HR-QoL after stroke is predicted by functional constraints, age, gender, and psychosocial factors, like socioeconomic status, depression, and coping style [ 4 , 6 – 8 ]. Functional constraints, age, gender, and socioeconomic status cannot or are difficult to change, but coping style could be targeted. The question then becomes if HR-QoL after stroke could be improved through a coping style intervention. If this is possible, a secondary question would be how such improvement relates to depression, health care consumption, and costs.

A common definition of coping style is someone’s preferred way of dealing with different situations. Several coping styles can be distinguished, such as active, passive, and avoidant coping. Wolters (2010) shows that in traumatic brain-injured (TBI) patients, higher HR-QoL in the long term is predicted by an increase in active problem-focused coping style and a decrease in passive emotion-focused coping style. Unfortunately, in this population of TBI patients the active coping decreases over time, while passive coping increases [ 9 ]. This suggests that if the decrease of active coping can be stopped, there is room for improvement in HR-QoL. Stroke patients make even less use of active, problem-oriented coping styles compared to other brain damaged patients [ 10 ]. Furthermore, Darlington (2007) shows that in stroke patients, coping becomes more important in determining HR-QoL over time, while the importance of general functioning decreases [ 11 ]. This would mean that long term HR-QoL could benefit from improved coping.

Coping styles can be influenced by several interventions. Backhaus (2010) shows that an intervention aimed at changing maladaptive coping styles positively influenced psychosocial functioning of TBI patients [ 12 ]. However, HR-QoL was not measured in this study. No research is found that investigated an intervention aimed at improving HR-QoL through the change of maladaptive coping styles in stroke patients. We therefore set out to investigate whether Problem Solving Therapy (PST), which aims at active problem-focused coping, might improve HR-QoL in stroke patients. PST has been proved effective in other patient populations [ 13 , 14 ]. In stroke patients, PST has been shown successful for the prevention of post stroke depression [ 15 ]. Effects on coping style and HR-QoL have not been investigated yet.

The primary aim of this study is to investigate whether PST is an effective group intervention for improving active problem-focused coping style and HR-QoL in stroke patients. The secondary aim is to determine the effect of PST on depression, social participation, health care consumption, and the cost-effectiveness of the intervention. The effectiveness of the therapy will be investigated in an open group design, which has not been used in PST research before. PST will be added to the standard care just before the end of the rehabilitation program, as at this moment a relapse in HR-QoL is frequently observed, when patients cannot rely on their therapists anymore [ 16 ]. By teaching patients to actively cope with stressful situations, through adapting and realizing their goals, we expect that patients will use more effective coping styles, which consequently may prevent the relapse in HR-QoL, and possibly increase HR-QoL in the long term. With regard to the secondary aims of this study, we expect the incidence of depression to decrease, social participation to improve, and health care consumption to decrease, resulting in a favorable cost-effectiveness ratio for the intervention.

Study design and procedure

The effectiveness of PST for stroke patients will be evaluated in a multicenter pragmatic randomized controlled trial (RCT) with one year follow-up, with the intervention performed in the daily practice of a sub-acute outpatient stroke rehabilitation program. As such, the potential effects of the intervention have a good external validity, which allows us to calculate the cost-effectiveness of the therapy compared with standard care.

The study will be performed in Rijndam Rehabilitation Center in collaboration with Erasmus MC, both in the Netherlands, and in Ghent University Hospital in Belgium. Patients are invited by their rehabilitation physician to participate in the study. Before the start of the study, patients need to sign the informed consent form. Data will be collected at four time points by one of three research psychologists. T0 is the baseline measurement, performed within three weeks before the start of the intervention phase. T1 will be performed within ten days after the intervention phase, T2 six months and T3 twelve months after the intervention phase (Figure 1 ). The measurements will be performed in the rehabilitation center or at the patients’ home in a face-to-face interview. The study has been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Erasmus MC University Medical Center and the Ethics Committee of Ghent University Hospital.

Design of the randomized controlled trial.

Study population

We strive to include 200 stroke patients. Inclusion criteria are: stroke (including subarachnoid hemorrhage), age between 18 and 75 years, being treated in the outpatient rehabilitation phase, and being able to participate in group therapy. Exclusion criteria are: progressive neurological disorders, life expectancy less than one year, insufficient understanding of the Dutch language, excessive drinking or drug abuse, subdural hematomas, moderate and severe aphasia. The same criteria would apply to the implementation of PST in practice, which stresses the pragmatic character of the trial. The inclusion of patients started March 2011 and will end August 2013. The one-year follow-up of all patients will be finished by September 2014.

Randomization

Patients are randomized to the intervention- or control condition using a stratified block randomization procedure with a block size of four. To ensure comparability between the two groups, patients are stratified per rehabilitation center. A member of the research group, who is not involved in the collection of the data, prospectively allocates the patients to the intervention- or control condition in a one-to-one ratio using an online random-number generator. To allow blinded randomization, the allocation information will be put in separate sealed envelopes which are consecutively numbered. At the end of the baseline measurement, the investigator opens the numbered envelop and informs the patient about the condition he or she is assigned to. The research psychologists who perform the baseline and follow-up measurements are blinded for treatment condition. The therapists who provide the intervention are not involved in the collection of the data. The investigator who will analyze the data is not involved in the collection of the follow-up measurements.

Intervention: problem solving therapy

Patients who are assigned to the intervention condition will receive PST in addition to the standard rehabilitation program, which will start during the last eight weeks of outpatient treatment. PST is a widely used and practical intervention method, based on a general model of coping with stress [ 17 , 18 ]. The model states that having a chronic disease causes stressful daily problems, which increase the chance of experiencing psychological stress and depressive feelings. Therefore, the aim of PST is to improve the skills to cope with the stressful daily problems in life after stroke.

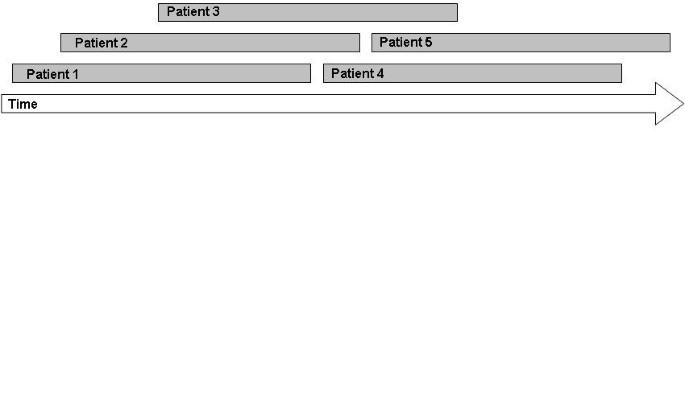

The intervention will be provided in an open group design, with a continuous flow of patients, which means that patients can enter the group every week and leave the group after eight sessions (Figure 2 ). The reason for this design is that it studies group therapy in its most feasible form, where patients start and end their programs at different time-points. If we had chosen to study the effect in closed groups, many patients in the similar stage of their programs are necessary. This would only be possible if patients are admitted to large scale rehabilitation centers, which is not the rehabilitation practice in The Netherlands, or patients would have to wait for a long time before entering the group. The open group design has some disadvantages. Patients may feel unsafe when they enter an already existing group. Furthermore, a continuous flow of patients is required to keep a balanced number of patients in the group. Therefore, interventions aimed at rare diseases cannot be studied with an open group design. However, for our population of stroke patients we do expect the design to be suitable and beneficial, because these patients are frequently seen in rehabilitation treatment. An open group design has several benefits as well. Advantages for the patients are that they do not have to wait until they can start with the intervention, they can share their experiences with other ‘experienced’ stroke patients, and there is room for interaction with many fellow patients. Other advantages are that the intervention is relatively easy to organize and implement in the daily practice of the rehabilitation center. This open group design has not been investigated in PST research yet.

Patient flow in an open group therapy.

The intervention in this study consists of eight group sessions of 1,5 hours a week, with homework exercises after each session. The group consists of a minimum of three and a maximum of six participants. PST is provided by one to three trained neuropsychologists per rehabilitation center. Solving problems will be structured, by dividing the problem solving process in four steps:

Define problem and goal;

Generating multiple solutions;

Considering the possible consequences of the solutions systematically and select the best solution;

Implement the solution and evaluate.

Each session starts with the sharing of experiences from the past week. Then, the model of problem solving will be repeated and explained. If there are some participants who are in the group for a couple of weeks already, they will be asked to explain the model to other new participants. Subsequently, one step of the model will be highlighted every week. With emphasis on this specific step, the model will be applied to one or more examples from the participants. Finally, the participants will be asked to practice the specific step at home by making a homework assignment. During the sessions, inadequate and irrational thoughts will be challenged by common cognitive interventions. A unique aspect of the intervention is the focus on the definition of the problem in the first step of the model. A clear definition of the problem will lead to a better understanding and more solutions to it.

Control condition: standard care

Patients who are assigned to the control condition will receive the standard rehabilitation program, in order to be able to study the additional effect of the intervention to the standard rehabilitation program. This standard rehabilitation program consists of individualized amounts of treatment by a physical therapist, occupational therapist, speech therapist, psychologist, social worker, and rehabilitation physician, depending on the severity of stroke. On average, stroke patients in outpatient rehabilitation receive twelve hours of treatment a week during a nine week rehabilitation program.

Primary outcome measures are changes in task-oriented coping and psychosocial HR-QoL in patients in the intervention group in comparison with the control group. Coping style is measured using the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) and the short version of the Social Problem Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R:SF). The CISS questionnaire consists of 48 questions and contains three subscales; Task-oriented coping, Emotion-oriented coping, and Avoidant coping. The subscale Avoidant coping consists of two subscales; Distraction and Social Diversion [ 18 , 19 ]. Because the PST aims at tasks, ‘Task-oriented coping’ is chosen as a primary endpoint; the other two subscales are used as secondary endpoints. The SPSI-R:SF questionnaire consists of ten questions about problem solving skills regarding daily situations. There are five subscales: Positive Problem Orientation, Rational Problem Solving, Negative Problem Orientation, Impulsivity/Carelessness Style, and Avoidance Style, and all are used as secondary endpoints in this trial [ 20 ].

HR-QoL is measured using the EuroQol (EQ-5D-5L) and the Stroke Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS-QoL-12). The EQ-5D is a generic questionnaire, and consists of five questions regarding mobility, self-care, daily activities, pain/complaints, mood, and a VAS scale. The five dimensions can be combined to one utility scale, representing the societal perspective of the general public [ 21 ]. The SS-QoL-12 is specifically developed for the population of stroke patients [ 22 ]. We will use the abbreviated version containing twelve items, which has been shown valid [ 23 ]. The questionnaire provides a total score and two sub scores: physical and psychosocial, of which the psychosocial sub-score is defined as the primary endpoint. The other HR-QoL scores are used as secondary endpoints.

Other secondary outcome measures are differences in depression, social participation, and health care consumption between patients in the intervention and control group. Additionally, the influence of cognitive functioning, personality characteristics, aphasia, type of stroke, side of stroke, level of functioning, and demographic characteristics on the outcomes will be assessed. Finally, the cost-effectiveness of the intervention will be calculated compared with standard care.

Depression is measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). This questionnaire consists of twenty items concerning depression, higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms [ 24 ].

Social participation is measured using the Impact on Participation and Autonomy (IPA). The questionnaire consists of five dimensions; Autonomy indoors, Family role, Autonomy outdoors, Social life and relationships, Work and education [ 25 ].

Health care consumption is measured using the Trimbos Questionnaire for Costs association with Psychiatric Illness (TiC-P). The questionnaire was developed for economic evaluation in mental health care, and measures health care consumption and productivity losses [ 26 ].

Sample size calculation

To determine the sample size for measuring differences between the intervention- and control group in coping style and HR-QoL, we searched for comparable effect sizes in the literature. With regard to coping style, there was no data available for this calculation. With regard to HR-QoL, Studenski (2005) measured an increase in HR-QoL after a physical therapy for stroke patients, with a long term effect size f ranging from 0.06 to 0.18 [ 27 ]. Because of the lack of more comparable data, we used this data and carefully estimated the effect size f to be 0.08. Considering the design of two groups and four repeated measurements, an expected correlation of 0.70, an alpha of 0.05, and a power of 0.80, we calculated a total required sample size of 132 patients based on the F-test. Because potential drop out is estimated at 0.30, we will strive to include 200 patients.

Statistical analyses

Demographic variables will be analyzed with an independent sample T-test for continuous variables, the Mann–Whitney U test for ordinal variables, and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Linear Mixed Models will be used to compare the repeated measurements between treatment groups, taking into account the correlation within and between subjects. We will create models for all the primary and secondary outcome variables, with time, group condition (intervention or control), and the interaction between these variables as predictors. Furthermore, we will control for variables that are accidentally not equally distributed between the two group conditions.

The cost-effectiveness of the intervention will be calculated by counting all the medical and non-medical costs, like productivity losses. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio will be calculated by dividing the difference in total costs by the difference in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). These QALYs will be calculated based on the EQ-5D questionnaire. The economic evaluation will be conducted according to the Dutch guidelines [ 28 ] and includes multivariate probabilistic sensitivity analyses. In the base case scenario the time horizon will be one year. If the effect is still present at one year follow up, a Markov model will be made to model a longer time horizon.

This study investigates the effect of PST on coping style and HR-QoL in stroke patients. In addition, the effect on depression, social participation, and health care consumption will be investigated, as well as the cost-effectiveness of the intervention. We will study the effectiveness of PST as close to the implementation in practice as possible, using a pragmatic trial design and an open group therapy. Any pragmatic trial has limitations; MacPherson (2004) argued that a pragmatic trial design cannot be used to determine the specific components of a treatment that caused an effect [ 29 ]. It may be possible that patients in the intervention group show improvement caused by the extra attention they receive and not so much by the assumed effective elements of the therapy; this attention effect may be considered a placebo effect. If we would like to distinguish between this ‘placebo effect’ and the effect of the specific treatment elements, the control group should have received a ‘sham therapy’. Such sham therapy would hinder the estimation of the effect of PST in practice, as in practice such additional effort would not take place. Therefore, one of the advantages of the pragmatic study design is that the external validity is better than using a sham-controlled design; the results will be generalizable to the normal rehabilitation setting [ 30 ]. The study population represents the normal stroke population in the outpatient phase of rehabilitation treatment, and the psychologists will provide the intervention to the patients just as they would do in practice. The results of a pragmatic trial are directly applicable to the usual care setting [ 31 ]. Moreover, if the intervention will prove effective, it will be easy to implement the intervention in the standard rehabilitation program, since it is already in use and the psychologists will already be trained. Other rehabilitation centers can use the therapy manual we developed.

We expect that patients who received PST will use more effective coping styles and experience a higher HR-QoL. Furthermore, we expect that patients after PST will show a decrease in depression score, an increase in social participation, and a decrease in health care consumption, which would lead to a reduction in the health care costs. We expect the intervention to be cost-effective, since the costs of the intervention are relatively low; one psychologist can train three to six patients at the same time. Darlington (2009) estimated the cost-effectiveness of an intervention aimed at coping strategies in stroke patients: the maximum costs for a single patient were 2500 euros, which will be lower if the therapy is provided in a group [ 32 ]. If PST will be proved effective for stroke patients in outpatient rehabilitation, the intervention will be an inexpensive, deliverable and sustainable group intervention that could be added to usual stroke rehabilitation programs.

Abbreviations

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations

- Health-related quality of life

Impact on Participation and Autonomy

- Problem Solving Therapy

Quality-adjusted life years

Randomized controlled trial

Social Problem Solving Inventory-Revised

Stroke Specific Quality of Life Scale

Traumatic brain-injured

Trimbos Questionnaire for Costs association with Psychiatric Illness

World Health Organization Quality of Life.

Evers SM, Engel GL, Ament AJ: Cost of stroke in The Netherlands from a societal perspective. Stroke. 1997, 28 (7): 1375-1381. 10.1161/01.STR.28.7.1375.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Vaartjes I, van Dis I, Visseren F, Bots M: Hart- en vaatziekten in Nederland 2009, cijfers over leefstijl- en risicofactoren, ziekte en sterfte. 2009, Den Haag: Nederlandse Hartstichting

Google Scholar

Group W, Harper A, Power M: Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998, 28 (3): 551-558.

Article Google Scholar

Sturm JW, Donnan GA, Dewey HM, Macdonell RAL, Gilligan AK, Srikanth V, Thrift AG: Quality of life after stroke - The North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Stroke. 2004, 35 (10): 2340-2345. 10.1161/01.STR.0000141977.18520.3b.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mittmann N, Trakas K, Risebrough N, Liu BA: Utility scores for chronic conditions in a community-dwelling population. Pharmaco Economics. 1999, 15 (4): 369-376. 10.2165/00019053-199915040-00004.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Paul SL, Sturm JW, Dewey HM, Donnan GA, Macdonell RAL, Thrift AG: Long-term outcome in the north east Melbourne stroke incidence study - Predictors of quality of life at 5 years after stroke. Stroke. 2005, 36 (10): 2082-2086. 10.1161/01.STR.0000183621.32045.31.

Almborg AH, Ulander K, Thulin A, Berg S: Discharged after stroke - important factors for health-related quality of life. J Clin Nursing. 2010, 19 (15–16): 2196-2206.

Patel MD, Tilling K, Lawrence E, Rudd AG, Wolfe CDA, McKevitt C: Relationships between long-term stroke disability, handicap and health-related quality of life. Age Ageing. 2006, 35 (3): 273-279. 10.1093/ageing/afj074.

Wolters G, Stapert S, Brands I, Van Heugten C: Coping styles in relation to cognitive rehabilitation and quality of life after brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2010, 20 (4): 587-600. 10.1080/09602011003683836.

Herrmann M, Curio N, Petz T, Synowitz H, Wagner S, Bartels C, Wallesch CW: Coping with illness after brain diseases - a comparison between patients with malignant brain tumors, stroke, Parkinson's disease and traumatic brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2000, 22 (12): 539-546. 10.1080/096382800416788.

Darlington ASE, Dippel DWJ, Ribbers GM, van Balen R, Passchier J, Busschbach JJV: Coping strategies as determinants of quality of life in stroke patients: A longitudinal study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007, 23 (5–6): 401-407.

Backhaus SL, Ibarra SL, Klyce D, Trexler LE, Malec JF: Brain Injury Coping Skills Group: A Preventative Intervention for Patients With Brain Injury and Their Caregivers. Archives Physical Med Rehabil. 2010, 91 (6): 840-848. 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.03.015.

Merlijn V, Hunfeld JAM, van der Wouden JC, Hazebroek-Kampschreur A, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, Koes BW, Passchier J: A cognitive-behavioural program for adolescents with chronic pain - a pilot study. Patient Educ Counseling. 2005, 59 (2): 126-134. 10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.010.

Hopko DR, Armento MEA, Robertson SMC, Ryba MM, Carvalho JP, Colman LK, Mullane C, Gawrysiak M, Bell JL, McNulty JK, et al: Brief Behavioral Activation and Problem-Solving Therapy for Depressed Breast Cancer Patients: Randomized Trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011, 79 (6): 834-849.

Robinson RG, Jorge RE, Moser DJ, Acion L, Solodkin A, Small SL, Fonzetti P, Hegel M, Arndt S: Escitalopram and problem-solving therapy for prevention of poststroke depression - A randomized controlled trial. Jama-Journal The Am Med Assoc. 2008, 299 (20): 2391-2400. 10.1001/jama.299.20.2391.

Ch'ng AM, French D, McLean N: Coping with the Challenges of Recovery from Stroke Long Term Perspectives of Stroke Support Group Members. J Health Psychology. 2008, 13 (8): 1136-1146. 10.1177/1359105308095967.

Nezu AM, Perri MG, Nezu CM, Berking M: Problem-solving therapy for depression: theory, research, and clinical guidelines. 1989, New York: Wiley

Nezu AM, Nezu CM: Problem Solving Therapy. J Psychother Integr. 2001, 11 (2): 187-205. 10.1023/A:1016653407338.

Endler NS, Parker JDA: Coping inventory for stressful situations (CISS) manual. 1990, Toronto: Multi-Health Systems

Hawkins D, Sofronoff K, Sheffield J: Psychometric Properties of the Social Problem Solving Inventory-Revised Short-Form: Is the Short Form a Valid and Reliable Measure for Young Adults?. Cognitive Therapy Res. 2009, 33 (5): 462-470. 10.1007/s10608-008-9209-7.

Lamers LM, McDonnell J, Stalmeier PF, Krabbe PF, Busschbach JJ: The Dutch tariff: results and arguments for an effective design for national EQ-5D valuation studies. Health Econ. 2006, 15 (10): 1121-1132. 10.1002/hec.1124.

Williams LS, Weinberger M, Harris LE, Clark DO, Biller J: Development of a stroke-specific quality of life scale. Stroke. 1999, 30 (7): 1362-1369. 10.1161/01.STR.30.7.1362.

Post MWM, Boosman H, van Zandvoort MM, Passier P, Rinkel GJE, Visser-Meily JMA: Development and validation of a short version of the Stroke Specific Quality of Life Scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011, 82 (3): 283-286. 10.1136/jnnp.2009.196394.

Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977, 1: 385-401. 10.1177/014662167700100306.

Cardol M, de Haan RJ, de Jong BA, van den Bos GAM, de Groot IJM: Psychometric properties of the impact on participation and autonomy questionnaire. Arch Physical Med Rehabil. 2001, 82 (2): 210-216. 10.1053/apmr.2001.18218.

Hakkaart-Van Roijen L: Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric Illness (TiC-P). Manual. September 2010, Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam

Studenski S, Duncan PW, Perera S, Reker D, Lai SM, Richards L: Daily functioning and quality of life in a randomized controlled trial of therapeutic exercise for subacute stroke survivors. Stroke. 2005, 36 (8): 1764-1770. 10.1161/01.STR.0000174192.87887.70.