- SpringerLink shop

Identifying your research question

Making informed decisions about what to study, and defining your research question, even within a predetermined field, is critical to a successful research career, and can be one of the hardest challenges for a scientist.

Being knowledgeable about the state of your field and up-to-date with recent developments can help you:

- Make decisions about what to study within niche research areas

- Identify top researchers in your field whose work you can follow and potentially collaborate with

- Find important journals to read regularly and publish in

- Explain to others why your work is important by being able to recount the bigger picture

How can you identify a research question?

Reading regularly is the most common way of identifying a good research question. This enables you to keep up to date with recent advancements and identify certain issues or unsolved problems that keep appearing.

Begin by searching for and reading literature in your field. Start with general interest journals, but don’t limit yourself to journal publications only; you can also look for clues in the news or on research blogs. Once you have identified a few interesting topics, you should be reading the table of contents of journals and the abstracts of most articles in that subject area. Papers that are directly related to your research you should read in their entirety.

TIP Keep an eye out for Review papers and special issues in your chosen subject area as they are very helpful in discovering new areas and hot topics.

TIP: you can sign up to receive table of contents or notifications when articles are published in your field from most journals or publishers.

TIP: Joining a journal club is a great way to read and dissect published papers in and around your subject area. Usually consisting of 5-10 people from the same research group or institute they meet to evaluate the good and bad points of the research presented in the paper. This not only helps you keep up to date with the field but helps you become familiar with what is necessary for a good paper which can help when you come to write your own.

If possible, communicate with some of the authors of these manuscripts via email or in person. Going to conferences if possible is a great way to meet some of these authors. Often, talking with the author of an important work in your research area will give you more ideas than just reading the manuscript would.

Back │ Next

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

How to Identify Research Questions

A research question is based on an area of concern or a lacuna in the existing knowledge. The purpose of a research question is to give your work a clear direction and to steer you to focus on important aspects that need to be solved. Learning how to identify research questions that are both meaningful and well-defined is also important for publication success. In fact, while identifying a research question is the very first step in a research project, it is also one of the most challenging activities in research.

How to identify a research question ?

As a researcher, you might need to generate research questions for various projects or come up with a thesis research question or dissertation research question. Here are some points that need to be considered when identifying research questions.

- Originality

An original research question aims to resolve a problem that has not been addressed before. Unique research work will increase your chances of publication, which makes it critical to know how to find a research question. So, familiarize yourself with the work done so far to identify knowledge gaps in the area and ensure that your question does not overlap with something that has already been asked and answered. Note that even within well-studied topics, you can generate research questions that are original simply by delving into the finer aspects of the topic or attempting to untangle a long-standing problem.

A good research question should be important enough and relevant to the scholarly literature in your area of inquiry. When you begin identifying research questions, contextualize the problem in a broad sense and consider the advantages and potential outcomes of answering a particular research problem. Your work should offer something new to the existing literature in your field.

- Feasibility

When you generate research questions, don’t forget to consider the feasibility of the project. Weigh all the possible practical constraints. Consider if the question(s) can be answered within a reasonable time, with the resources, expertise, and funding you have at your disposal.

- Ethical and legal aspects

If you are dealing with animal or human subjects, political issues, etc., your research question will need to factor in ethical and/or legal requirements and implications.

Tips on how to identify research questions

When you generate research questions, it is also important to consider the most up-to-date trends in the subject area, along with your own observations or conjectures.

1. Read as much as you can

The answer to how to identify research questions lies in reading the right material and reading extensively. Reading regularly is the most basic way to find a good research question. Keep up to date with recent advancements and identify critical issues or unsolved problems. You could begin with popular science articles and blogs and, if something catches your interest, look up those topics in journals specializing in them.

Do not miss out on review papers and meta-analyses on your chosen subject area; they are very helpful in discovering hot topics and unanswered questions.

2. Refine your literature search

If you want to know how to identify the research problem and find an original or unique question in your field, perform an extensive literature search to identify gaps in research that have remained unaddressed. The best way to identify research questions is to conduct both forward and backward literature searches, i.e., look through the reference lists of relevant articles, as well as the papers that have cited them.

When you generate research questions, avoid relying only on a few search engines and databases. Use a combination of databases and generalist and specialist search engines. This makes the journey of identifying research questions easier.

If you’re wondering how to identify research questions in an article, extensive and relevant reading is the key. Given the importance of literature searching and reading, R Discovery could be your perfect companion. R Discovery is a literature discovery app that lets you identify and read the most relevant academic research papers from top journals and publishers, covering all major disciplines in the arts and sciences. You can even access the latest preprints, which bring to light the latest research before it is published. This tool allows you to survey highlights and summaries of papers; once you hit upon something exciting, you can read the full version.

3. Define your keywords

Selecting effective keywords are important for a targeted literature search. Identify the key concepts in the topic(s) you are considering. From these, tease out some important keywords, and be sure to include synonyms or alternative phrasing when using search engines or academic databases. This will help to generate good research questions.

When you feed in key terms in the R Discovery literature search tool, it “deep-dives” into the topics and shows up articles that you can sort by recency or relevance and then choose to read in full. Based on your search history, the app even offers a personalized feed. Such customized research reading can make the process of generating research questions much easier.

4. Frame the research question

You have now understood how to find research questions, but do you know how to frame them? Framing the question properly is as important as knowing how to identify research questions. Create lists, thought bubbles, or mind maps to help you do some brainstorming till you hit on a good research question. List ideas from general to specific and from broad to narrow.

Knowing the current status of the topic, including what is known and what is not, will help you refine the original problem statement to a defined and more specific version.

Putting it all together

A good research question is compelling and timely. To generate research questions that can ensure publication success, it is important to stay up to date with the latest in your field and allied fields, as well as generalist and specialist topics. Efficient literature discovery serves as the perfect springboard to jumpstart your foray into an exciting and rewarding research journey.

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

Top 7 Tried and Tested Paraphrasing Techniques

Annex vs Appendix: What is the difference?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Published on October 26, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research question pinpoints exactly what you want to find out in your work. A good research question is essential to guide your research paper , dissertation , or thesis .

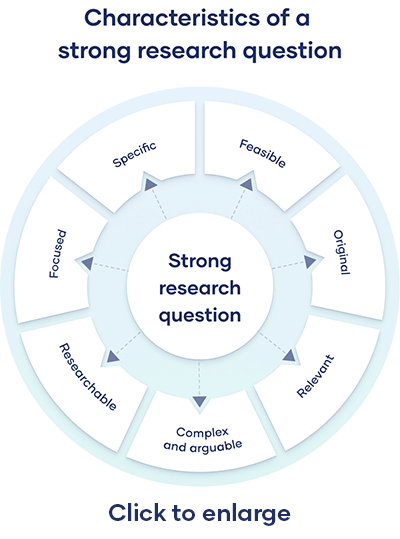

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Table of contents

How to write a research question, what makes a strong research question, using sub-questions to strengthen your main research question, research questions quiz, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research questions.

You can follow these steps to develop a strong research question:

- Choose your topic

- Do some preliminary reading about the current state of the field

- Narrow your focus to a specific niche

- Identify the research problem that you will address

The way you frame your question depends on what your research aims to achieve. The table below shows some examples of how you might formulate questions for different purposes.

| Research question formulations | |

|---|---|

| Describing and exploring | |

| Explaining and testing | |

| Evaluating and acting | is X |

Using your research problem to develop your research question

| Example research problem | Example research question(s) |

|---|---|

| Teachers at the school do not have the skills to recognize or properly guide gifted children in the classroom. | What practical techniques can teachers use to better identify and guide gifted children? |

| Young people increasingly engage in the “gig economy,” rather than traditional full-time employment. However, it is unclear why they choose to do so. | What are the main factors influencing young people’s decisions to engage in the gig economy? |

Note that while most research questions can be answered with various types of research , the way you frame your question should help determine your choices.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Research questions anchor your whole project, so it’s important to spend some time refining them. The criteria below can help you evaluate the strength of your research question.

Focused and researchable

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Focused on a single topic | Your central research question should work together with your research problem to keep your work focused. If you have multiple questions, they should all clearly tie back to your central aim. |

| Answerable using | Your question must be answerable using and/or , or by reading scholarly sources on the to develop your argument. If such data is impossible to access, you likely need to rethink your question. |

| Not based on value judgements | Avoid subjective words like , , and . These do not give clear criteria for answering the question. |

Feasible and specific

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Answerable within practical constraints | Make sure you have enough time and resources to do all research required to answer your question. If it seems you will not be able to gain access to the data you need, consider narrowing down your question to be more specific. |

| Uses specific, well-defined concepts | All the terms you use in the research question should have clear meanings. Avoid vague language, jargon, and too-broad ideas. |

| Does not demand a conclusive solution, policy, or course of action | Research is about informing, not instructing. Even if your project is focused on a practical problem, it should aim to improve understanding rather than demand a ready-made solution. If ready-made solutions are necessary, consider conducting instead. Action research is a research method that aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as it is solved. In other words, as its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time. |

Complex and arguable

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Cannot be answered with or | Closed-ended, / questions are too simple to work as good research questions—they don’t provide enough for robust investigation and discussion. |

| Cannot be answered with easily-found facts | If you can answer the question through a single Google search, book, or article, it is probably not complex enough. A good research question requires original data, synthesis of multiple sources, and original interpretation and argumentation prior to providing an answer. |

Relevant and original

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Addresses a relevant problem | Your research question should be developed based on initial reading around your . It should focus on addressing a problem or gap in the existing knowledge in your field or discipline. |

| Contributes to a timely social or academic debate | The question should aim to contribute to an existing and current debate in your field or in society at large. It should produce knowledge that future researchers or practitioners can later build on. |

| Has not already been answered | You don’t have to ask something that nobody has ever thought of before, but your question should have some aspect of originality. For example, you can focus on a specific location, or explore a new angle. |

Chances are that your main research question likely can’t be answered all at once. That’s why sub-questions are important: they allow you to answer your main question in a step-by-step manner.

Good sub-questions should be:

- Less complex than the main question

- Focused only on 1 type of research

- Presented in a logical order

Here are a few examples of descriptive and framing questions:

- Descriptive: According to current government arguments, how should a European bank tax be implemented?

- Descriptive: Which countries have a bank tax/levy on financial transactions?

- Framing: How should a bank tax/levy on financial transactions look at a European level?

Keep in mind that sub-questions are by no means mandatory. They should only be asked if you need the findings to answer your main question. If your main question is simple enough to stand on its own, it’s okay to skip the sub-question part. As a rule of thumb, the more complex your subject, the more sub-questions you’ll need.

Try to limit yourself to 4 or 5 sub-questions, maximum. If you feel you need more than this, it may be indication that your main research question is not sufficiently specific. In this case, it’s is better to revisit your problem statement and try to tighten your main question up.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis —a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

As you cannot possibly read every source related to your topic, it’s important to evaluate sources to assess their relevance. Use preliminary evaluation to determine whether a source is worth examining in more depth.

This involves:

- Reading abstracts , prefaces, introductions , and conclusions

- Looking at the table of contents to determine the scope of the work

- Consulting the index for key terms or the names of important scholars

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (“ x affects y because …”).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses . In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Formulating a main research question can be a difficult task. Overall, your question should contribute to solving the problem that you have defined in your problem statement .

However, it should also fulfill criteria in three main areas:

- Researchability

- Feasibility and specificity

- Relevance and originality

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 21). Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-questions/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to define a research problem | ideas & examples, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, 10 research question examples to guide your research project, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- McGill Library

Systematic Reviews, Scoping Reviews, and other Knowledge Syntheses

- Identifying the research question

- Types of knowledge syntheses

- Process of conducting a knowledge synthesis

Constructing a good research question

Inclusion/exclusion criteria, has your review already been done, where to find other reviews or syntheses, references on question formulation frameworks.

- Developing the protocol

- Database-specific operators and fields

- Search filters and tools

- Exporting and documenting search results

- Deduplicating

- Grey literature and other supplementary search methods

- Documenting the search methods

- Updating the database searches

- Resources for screening, appraisal, and synthesis

- Writing the review

- Additional training resources

Formulating a well-constructed research question is essential for a successful review. You should have a draft research question before you choose the type of knowledge synthesis that you will conduct, as the type of answers you are looking for will help guide your choice of knowledge synthesis.

Examples of systematic review and scoping review questions

| A systematic review question | A scoping review question |

|---|---|

| Typically a focused research question with narrow parameters, and usually fits into the PICO question format | Often a broad question that looks at answering larger, more complex, exploratory research questions and often does not fit into the PICO question format |

| Example: "In people with multiple sclerosis, what is the extent to which a walking intervention, compared to no intervention, improves self-report fatigue?" | Example: "What rehabilitation interventions are used to reduce fatigue in adults with multiple sclerosis?" |

- Process of formulating a question

Developing a good research question is not a straightforward process and requires engaging with the literature as you refine and rework your idea.

Some questions that might be useful to ask yourself as you are drafting your question:

- Does the question fit into the PICO question format?

- What age group?

- What type or types of conditions?

- What intervention? How else might it be described?

- What outcomes? How else might they be described?

- What is the relationship between the different elements of your question?

- Do you have several questions lumped into one? If so, should you split them into more than one review? Alternatively, do you have many questions that could be lumped into one review?

A good knowledge synthesis question will have the following qualities:

- Be focused on a specific question with a meaningful answer

- Retrieve a number of results that is manageable for the research team (is the number of results on your topic feasible for you to finish the review? Your initial literature searches should give you an idea, and a librarian can help you with understanding the size of your question).

Considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria

It is important to think about which studies will be included in your review when you are writing your research question. The Cochrane Handbook chapter (linked below) offers guidance on this aspect.

McKenzie, J. E., Brennan, S. E., Ryan, R. E., Thomson, H. J., Johnston, R. V, & Thomas, J. (2021). Chapter 3: Defining the criteria for including studies and how they will be grouped for the synthesis. Retrieved from https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-03

Once you have a reasonably well defined research question, it is important to make sure your project has not already been recently and successfully undertaken. This means it is important to find out if there are other knowledge syntheses that have been published or that are in the process of being published on your topic.

If you are submitting your review or study for funding, for example, you may want to make a good case that your review or study is needed and not duplicating work that has already been successfully and recently completed—or that is in the process of being completed. It is also important to note that what is considered “recent” will depend on your discipline and the topic.

In the context of conducting a review, even if you do find one on your topic, it may be sufficiently out of date or you may find other defendable reasons to undertake a new or updated one. In addition, looking at other knowledge syntheses published around your topic may help you refocus your question or redirect your research toward other gaps in the literature.

- PROSPERO Search PROSPERO is an international, searchable database that allows free registration of systematic reviews, rapid reviews, and umbrella reviews with a health-related outcome in health & social care, welfare, public health, education, crime, justice, and international development. Note: PROSPERO does not accept scoping review protocols.

- Open Science Framework (OSF) At present, OSF does not allow for Boolean searching on their site. However, you can search via https://share.osf.io/, an aggregator, that allows you to search for major keywords using Boolean and truncation. Add "review*" to your search to narrow results down to scoping, systematic, umbrella or other types of reviews. Be sure to click on the drop-down menu for "Source" and select OSF and OSF Registries (search separately as you can't combine them). This will search for ongoing and/or registered reviews in OSF.

The Cochrane Library (including systematic reviews of interventions, diagnostic studies, prognostic studies, and more) is an excellent place to start, even if Cochrane reviews are also indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed.

By default, the Cochrane Library will display “ Cochrane Reviews ” (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, aka CDSR). You can ignore the results which show up in the Trials tab when looking for systematic reviews: They are records of controlled trials.

The example shows the number of Cochrane Reviews with hiv AND circumcision in the title, abstract, or keywords.

- Google Scholar

Subject-specific databases you can search to find existing or in-process reviews

Alternatively, you can use a search hedge/filter; for example, the filter used by BMJ Best Practice to find systematic reviews in Embase (can be copied and pasted into the Embase search box then combined with the concepts of your research question):

(exp review/ or (literature adj3 review$).ti,ab. or exp meta analysis/ or exp "Systematic Review"/) and ((medline or medlars or embase or pubmed or cinahl or amed or psychlit or psyclit or psychinfo or psycinfo or scisearch or cochrane).ti,ab. or RETRACTED ARTICLE/) or (systematic$ adj2 (review$ or overview)).ti,ab. or (meta?anal$ or meta anal$ or meta-anal$ or metaanal$ or metanal$).ti,ab.

Alternative interface to PubMed: You can also search MEDLINE on the Ovid platform, which we recommend for systematic searching. Perform a sufficiently developed search strategy (be as broad in your search as is reasonably possible) and then, from Additional Limits , select the publication type Systematic Reviews, or select the subject subset Systematic Reviews Pre 2019 for more sensitive/less precise results.

The subject subset for Systematic Reviews is based on the filter version used in PubMed .

Perform a sufficiently developed search strategy (be as broad in your search as is reasonably possible) and then, from Additional Limits , select, under Methodology, 0830 Systematic Review

See Systematic Reviews Search Strategy Applied in PubMed for details.

- healthevidence.org Database of thousands of "quality-rated reviews on the effectiveness of public health interventions"

- See also: Evidence-informed resources for Public Health

Munn Z, Stern C, Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Jordan Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4

Scoping reviews: Developing the title and question . In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors) . JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-01

Due to a large influx of requests, there may be an extended wait time for librarian support on knowledge syntheses.

Find a librarian in your subject area to help you with your knowledge synthesis project.

Or contact the librarians at the Schulich Library of Physical Sciences, Life Sciences, and Engineering s [email protected]

Need help? Ask us!

Online training resources.

- Advanced Research Skills: Conducting Literature and Systematic Reviews A short course for graduate students to increase their proficiency in conducting research for literature and systematic reviews developed by the Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson).

- Compétences avancées en matière de recherche : Effectuer des revues de la littérature et des revues systématiques (2e édition) Ce cours destiné aux étudiant.e.s universitaires vise à peaufiner leurs compétences dans la réalisation de revues systématiques et de recherches dans la littérature en vue de mener avec succès leurs propres recherches durant leur parcours universitaire et leur éventuelle carrière.

- The Art and Science of Searching in Systematic Reviews Self-paced course on search strategies, information sources, project management, and reporting (National University of Singapore)

- CERTaIN: Knowledge Synthesis: Systematic Reviews and Clinical Decision Making "Learn how to interpret and report systematic review and meta-analysis results, and define strategies for searching and critically appraising scientific literature" (MDAndersonX)

- Cochrane Interactive Learning Online modules that walk you through the process of working on a Cochrane intervention review. Module 1 is free (login to access) but otherwise payment is required to complete the online training

- Evidence Synthesis for Librarians and Information Specialists Introduction to core components of evidence synthesis. Developed by the Evidence Synthesis Institute. Free for a limited time as of July 10, 2024.

- Introduction to Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Free coursera MOOC offered by Johns Hopkins University; covers the whole process of conducting a systematic review; week 3 focuses on searching and assessing bias

- Mieux réussir un examen de la portée en sciences de la santé : une boîte à outils Cette ressource éducative libre (REL) est conçue pour soutenir les étudiant·e·s universitaires en sciences de la santé dans la préparation d’un examen de la portée de qualité.

- Online Methods Course in Systematic Review and Systematic Mapping "This step-by-step course takes time to explain the theory behind each part of the review process, and provides guidance, tips and advice for those wanting to undertake a full systematic review or map." Developed using an environmental framework (Collaboration for Environmental Evidence, Stockholm Environment Institute)

- Scoping Review Methods for Producing Research Syntheses Two-part, online workshop sponsored by the Center on Knowledge Translation for Disability and Rehabilitation Research (KTDRR)

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Online overview of the steps involved in systematic reviews of quantitative studies, with options to practice. Courtesy of the Campbell Collaboration and the Open Learning Initiative (Carnegie Mellon University). Free pilot

- Systematic Searches Developed by the Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library (Yale University)

- Systematic Reviews of Animal Studies (SYRCLE) Introduction to systematic reviews of animal studies

- << Previous: Types of knowledge syntheses

- Next: Developing the protocol >>

- Last Updated: Jul 17, 2024 3:57 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.mcgill.ca/knowledge-syntheses

McGill Library • Questions? Ask us! Privacy notice

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 1. Identify the Question

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

Identify the question

Developing a research question.

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- 6. Synthesize

- 7. Write a Literature Review

From Topic to Question (Infographic)

This graphic emphasizes how reading various sources can play a role in defining your research topic.

( Click to Enlarge Image )

Text description of "From Topic to Question" for web accessibility

In some cases, such as for a course assignment or a research project you're working on with a faculty mentor, your research question will be determined by your professor. If that's the case, you can move on to the next step . Otherwise, you may need to explore questions on your own.

A few suggestions

Photo Credit: UO Libraries

According to The Craft of Research (2003) , a research question is more than a practical problem or something with a yes/no answer. A research question helps you learn more about something you don't already know and it needs to be significant enough to interest your readers.

Your Curiosity + Significance to Others = Research Question

How to get started.

In a research paper, you develop a unique question and then synthesize scholarly and primary sources into a paper that supports your argument about the topic.

- Identify your Topic (This is the starting place from where you develop a research question.)

- Refine by Searching (find background information) (Before you can start to develop a research question, you may need to do some preliminary background research to see (1) what has already been done on the topic and (2) what are the issues surrounding the topic.) HINT: Find background information in Google and Books.

- Refine by Narrowing (Once you begin to understand the topic and the issues surrounding it, you can start to narrow your topic and develop a research question. Do this by asking the 6 journalistic question words.

Ask yourself these 6 questions

These 6 journalistic question words can help you narrow your focus from a broad topic to a specific question.

Who : Are you interested in a specific group of people? Can your topic be narrowed by gender, sex, age, ethnicity, socio-economic status or something else? Are there any key figures related to your topic?

What : What are the issues surrounding your topic? Are there subtopics? In looking at background information, did you notice any gaps or questions that seemed unanswered?

Where : Can your topic be narrowed down to a geographic location? Warning: Don't get too narrow here. You might not be able to find enough information on a town or state.

When : Is your topic current or historical? Is it confined to a specific time period? Was there a causative event that led your topic to become an area of study?

Why : Why are you interested in this topic? Why should others be interested?

How : What kinds of information do you need? Primary sources, statistics? What is your methodology?

Detailed description of, "Developing a Research Question" for web accessibility

- << Previous: Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- Next: 2. Review Discipline Styles >>

- Last Updated: May 3, 2024 5:17 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.16(7); 2020 Jul

Ten simple rules for reading a scientific paper

Maureen a. carey.

Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health, Department of Medicine, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

Kevin L. Steiner

William a. petri, jr, introduction.

“There is no problem that a library card can't solve” according to author Eleanor Brown [ 1 ]. This advice is sound, probably for both life and science, but even the best tool (like the library) is most effective when accompanied by instructions and a basic understanding of how and when to use it.

For many budding scientists, the first day in a new lab setting often involves a stack of papers, an email full of links to pertinent articles, or some promise of a richer understanding so long as one reads enough of the scientific literature. However, the purpose and approach to reading a scientific article is unlike that of reading a news story, novel, or even a textbook and can initially seem unapproachable. Having good habits for reading scientific literature is key to setting oneself up for success, identifying new research questions, and filling in the gaps in one’s current understanding; developing these good habits is the first crucial step.

Advice typically centers around two main tips: read actively and read often. However, active reading, or reading with an intent to understand, is both a learned skill and a level of effort. Although there is no one best way to do this, we present 10 simple rules, relevant to novices and seasoned scientists alike, to teach our strategy for active reading based on our experience as readers and as mentors of undergraduate and graduate researchers, medical students, fellows, and early career faculty. Rules 1–5 are big picture recommendations. Rules 6–8 relate to philosophy of reading. Rules 9–10 guide the “now what?” questions one should ask after reading and how to integrate what was learned into one’s own science.

Rule 1: Pick your reading goal

What you want to get out of an article should influence your approach to reading it. Table 1 includes a handful of example intentions and how you might prioritize different parts of the same article differently based on your goals as a reader.

| Examples | Intention | Priorities |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | You are new to reading scientific papers. | For each panel of each figure, focus particularly on the questions outlined in Rule 3. |

| 2 | You are entering a new field and want to learn what is important in that field. | Focus on the beginning (motivation presented in the introduction) and the end (next steps presented in the conclusion). |

| 3 | You receive automated alerts to notify you of the latest publication from a particular author whose work inspires you; you are hoping to work with them for the next phase of your research career and want to know what they are involved in. | Skim the entire work, thinking about how it fits into the author’s broader publication history. |

| 4 | You receive automated alerts to notify you of the latest publication containing a set of keywords because you want to be aware of new ways a technique is being applied or the new developments in a particular topic or research area. | Focus on what was done in the methods and the motivation for the approach taken; this is often presented in the introduction. |

| 5 | You were asked to review an article prior to publication to evaluate the quality of work or to present in a journal club. | Same as example 1. Also, do the data support the interpretations? What alternative explanations exist? Are the data presented in a logical way so that many researchers would be able to understand? If the research is about a controversial topic, do the author(s) appropriately present the conflict and avoid letting their own biases influence the interpretation? |

1 Yay! Welcome!

2 A journal club is when a group of scientists get together to discuss a paper. Usually one person leads the discussion and presents all of the data. The group discusses their own interpretations and the authors’ interpretation.

Rule 2: Understand the author’s goal

In written communication, the reader and the writer are equally important. Both influence the final outcome: in this case, your scientific understanding! After identifying your goal, think about the author’s goal for sharing this project. This will help you interpret the data and understand the author’s interpretation of the data. However, this requires some understanding of who the author(s) are (e.g., what are their scientific interests?), the scientific field in which they work (e.g., what techniques are available in this field?), and how this paper fits into the author’s research (e.g., is this work building on an author’s longstanding project or controversial idea?). This information may be hard to glean without experience and a history of reading. But don’t let this be a discouragement to starting the process; it is by the act of reading that this experience is gained!

A good step toward understanding the goal of the author(s) is to ask yourself: What kind of article is this? Journals publish different types of articles, including methods, review, commentary, resources, and research articles as well as other types that are specific to a particular journal or groups of journals. These article types have different formatting requirements and expectations for content. Knowing the article type will help guide your evaluation of the information presented. Is the article a methods paper, presenting a new technique? Is the article a review article, intended to summarize a field or problem? Is it a commentary, intended to take a stand on a controversy or give a big picture perspective on a problem? Is it a resource article, presenting a new tool or data set for others to use? Is it a research article, written to present new data and the authors’ interpretation of those data? The type of paper, and its intended purpose, will get you on your way to understanding the author’s goal.

Rule 3: Ask six questions

When reading, ask yourself: (1) What do the author(s) want to know (motivation)? (2) What did they do (approach/methods)? (3) Why was it done that way (context within the field)? (4) What do the results show (figures and data tables)? (5) How did the author(s) interpret the results (interpretation/discussion)? (6) What should be done next? (Regarding this last question, the author(s) may provide some suggestions in the discussion, but the key is to ask yourself what you think should come next.)

Each of these questions can and should be asked about the complete work as well as each table, figure, or experiment within the paper. Early on, it can take a long time to read one article front to back, and this can be intimidating. Break down your understanding of each section of the work with these questions to make the effort more manageable.

Rule 4: Unpack each figure and table

Scientists write original research papers primarily to present new data that may change or reinforce the collective knowledge of a field. Therefore, the most important parts of this type of scientific paper are the data. Some people like to scrutinize the figures and tables (including legends) before reading any of the “main text”: because all of the important information should be obtained through the data. Others prefer to read through the results section while sequentially examining the figures and tables as they are addressed in the text. There is no correct or incorrect approach: Try both to see what works best for you. The key is making sure that one understands the presented data and how it was obtained.

For each figure, work to understand each x- and y-axes, color scheme, statistical approach (if one was used), and why the particular plotting approach was used. For each table, identify what experimental groups and variables are presented. Identify what is shown and how the data were collected. This is typically summarized in the legend or caption but often requires digging deeper into the methods: Do not be afraid to refer back to the methods section frequently to ensure a full understanding of how the presented data were obtained. Again, ask the questions in Rule 3 for each figure or panel and conclude with articulating the “take home” message.

Rule 5: Understand the formatting intentions

Just like the overall intent of the article (discussed in Rule 2), the intent of each section within a research article can guide your interpretation. Some sections are intended to be written as objective descriptions of the data (i.e., the Results section), whereas other sections are intended to present the author’s interpretation of the data. Remember though that even “objective” sections are written by and, therefore, influenced by the authors interpretations. Check out Table 2 to understand the intent of each section of a research article. When reading a specific paper, you can also refer to the journal’s website to understand the formatting intentions. The “For Authors” section of a website will have some nitty gritty information that is less relevant for the reader (like word counts) but will also summarize what the journal editors expect in each section. This will help to familiarize you with the goal of each article section.

| Section | Content |

|---|---|

| Title | The “take home” message of the entire project, according to the authors. |

| Author list | These people made significant scientific contributions to the project. Fields differ in the standard practice for ordering authors. For example, as a general rule for biomedical sciences, the first author led the project’s implementation, and the last author was the primary supervisor to the project. |

| Abstract | A brief overview of the research question, approach, results, and interpretation. This is the road map or elevator pitch for an article. |

| Introduction | Several paragraphs (or less) to present the research question and why it is important. A newcomer to the field should get a crash course in the field from this section. |

| Methods | What was done? How was it done? Ideally, one should be able to recreate a project by reading the methods. In reality, the methods are often overly condensed. Sometimes greater detail is provided within a “Supplemental” section available online (see below). |

| Results | What was found? Paragraphs often begin with a statement like this: “To do X, we used approach Y to measure Z.” The results should be objective observations. |

| Figures, tables, legends, and captions | The data are presented in figures and tables. Legends and captions provide necessary information like abbreviations, summaries of methods, and clarifications. |

| Discussion | What do the results mean and how do they relate to previous findings in the literature? This is the perspective of the author(s) on the results and their ideas on what might be appropriate next steps. Often it may describe some (often not all!) strengths and limitations of the study: Pay attention to this self-reflection of the author(s) and consider whether you agree or would add to their ideas. |

| Conclusion | A brief summary of the implications of the results. |

| References | A list of previously published papers, datasets, or databases that were essential for the implementation of this project or interpretation of data. This section may be a valuable resource listing important papers within the field that are worth reading as well. |

| Supplemental material | Any additional methods, results, or information necessary to support the results or interpretations presented in the discussion. |

| Supplemental data | Essential datasets that are too large or cumbersome to include in the paper. Especially for papers that include “big data” (like sequencing or modeling results), this is often where the real, raw data is presented. |

Research articles typically contain each of these sections, although sometimes the “results” and “discussion” sections (or “discussion” and “conclusion” sections) are merged into one section. Additional sections may be included, based on request of the journal or the author(s). Keep in mind: If it was included, someone thought it was important for you to read.

Rule 6: Be critical

Published papers are not truths etched in stone. Published papers in high impact journals are not truths etched in stone. Published papers by bigwigs in the field are not truths etched in stone. Published papers that seem to agree with your own hypothesis or data are not etched in stone. Published papers that seem to refute your hypothesis or data are not etched in stone.

Science is a never-ending work in progress, and it is essential that the reader pushes back against the author’s interpretation to test the strength of their conclusions. Everyone has their own perspective and may interpret the same data in different ways. Mistakes are sometimes published, but more often these apparent errors are due to other factors such as limitations of a methodology and other limits to generalizability (selection bias, unaddressed, or unappreciated confounders). When reading a paper, it is important to consider if these factors are pertinent.

Critical thinking is a tough skill to learn but ultimately boils down to evaluating data while minimizing biases. Ask yourself: Are there other, equally likely, explanations for what is observed? In addition to paying close attention to potential biases of the study or author(s), a reader should also be alert to one’s own preceding perspective (and biases). Take time to ask oneself: Do I find this paper compelling because it affirms something I already think (or wish) is true? Or am I discounting their findings because it differs from what I expect or from my own work?

The phenomenon of a self-fulfilling prophecy, or expectancy, is well studied in the psychology literature [ 2 ] and is why many studies are conducted in a “blinded” manner [ 3 ]. It refers to the idea that a person may assume something to be true and their resultant behavior aligns to make it true. In other words, as humans and scientists, we often find exactly what we are looking for. A scientist may only test their hypotheses and fail to evaluate alternative hypotheses; perhaps, a scientist may not be aware of alternative, less biased ways to test her or his hypothesis that are typically used in different fields. Individuals with different life, academic, and work experiences may think of several alternative hypotheses, all equally supported by the data.

Rule 7: Be kind

The author(s) are human too. So, whenever possible, give them the benefit of the doubt. An author may write a phrase differently than you would, forcing you to reread the sentence to understand it. Someone in your field may neglect to cite your paper because of a reference count limit. A figure panel may be misreferenced as Supplemental Fig 3E when it is obviously Supplemental Fig 4E. While these things may be frustrating, none are an indication that the quality of work is poor. Try to avoid letting these minor things influence your evaluation and interpretation of the work.

Similarly, if you intend to share your critique with others, be extra kind. An author (especially the lead author) may invest years of their time into a single paper. Hearing a kindly phrased critique can be difficult but constructive. Hearing a rude, brusque, or mean-spirited critique can be heartbreaking, especially for young scientists or those seeking to establish their place within a field and who may worry that they do not belong.

Rule 8: Be ready to go the extra mile

To truly understand a scientific work, you often will need to look up a term, dig into the supplemental materials, or read one or more of the cited references. This process takes time. Some advisors recommend reading an article three times: The first time, simply read without the pressure of understanding or critiquing the work. For the second time, aim to understand the paper. For the third read through, take notes.

Some people engage with a paper by printing it out and writing all over it. The reader might write question marks in the margins to mark parts (s)he wants to return to, circle unfamiliar terms (and then actually look them up!), highlight or underline important statements, and draw arrows linking figures and the corresponding interpretation in the discussion. Not everyone needs a paper copy to engage in the reading process but, whatever your version of “printing it out” is, do it.

Rule 9: Talk about it

Talking about an article in a journal club or more informal environment forces active reading and participation with the material. Studies show that teaching is one of the best ways to learn and that teachers learn the material even better as the teaching task becomes more complex [ 4 – 5 ]; anecdotally, such observations inspired the phrase “to teach is to learn twice.”

Beyond formal settings such as journal clubs, lab meetings, and academic classes, discuss papers with your peers, mentors, and colleagues in person or electronically. Twitter and other social media platforms have become excellent resources for discussing papers with other scientists, the public or your nonscientist friends, or even the paper’s author(s). Describing a paper can be done at multiple levels and your description can contain all of the scientific details, only the big picture summary, or perhaps the implications for the average person in your community. All of these descriptions will solidify your understanding, while highlighting gaps in your knowledge and informing those around you.

Rule 10: Build on it

One approach we like to use for communicating how we build on the scientific literature is by starting research presentations with an image depicting a wall of Lego bricks. Each brick is labeled with the reference for a paper, and the wall highlights the body of literature on which the work is built. We describe the work and conclusions of each paper represented by a labeled brick and discuss each brick and the wall as a whole. The top brick on the wall is left blank: We aspire to build on this work and label this brick with our own work. We then delve into our own research, discoveries, and the conclusions it inspires. We finish our presentations with the image of the Legos and summarize our presentation on that empty brick.

Whether you are reading an article to understand a new topic area or to move a research project forward, effective learning requires that you integrate knowledge from multiple sources (“click” those Lego bricks together) and build upwards. Leveraging published work will enable you to build a stronger and taller structure. The first row of bricks is more stable once a second row is assembled on top of it and so on and so forth. Moreover, the Lego construction will become taller and larger if you build upon the work of others, rather than using only your own bricks.

Build on the article you read by thinking about how it connects to ideas described in other papers and within own work, implementing a technique in your own research, or attempting to challenge or support the hypothesis of the author(s) with a more extensive literature review. Integrate the techniques and scientific conclusions learned from an article into your own research or perspective in the classroom or research lab. You may find that this process strengthens your understanding, leads you toward new and unexpected interests or research questions, or returns you back to the original article with new questions and critiques of the work. All of these experiences are part of the “active reading”: process and are signs of a successful reading experience.

In summary, practice these rules to learn how to read a scientific article, keeping in mind that this process will get easier (and faster) with experience. We are firm believers that an hour in the library will save a week at the bench; this diligent practice will ultimately make you both a more knowledgeable and productive scientist. As you develop the skills to read an article, try to also foster good reading and learning habits for yourself (recommendations here: [ 6 ] and [ 7 ], respectively) and in others. Good luck and happy reading!

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the mentors, teachers, and students who have shaped our thoughts on reading, learning, and what science is all about.

Funding Statement

MAC was supported by the PhRMA Foundation's Postdoctoral Fellowship in Translational Medicine and Therapeutics and the University of Virginia's Engineering-in-Medicine seed grant, and KLS was supported by the NIH T32 Global Biothreats Training Program at the University of Virginia (AI055432). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

How to Identify a Meaningful Research Question

When starting a new research project, it is important to develop a sound research question. This is a crucial step in the research process, as it will guide your research activity. Therefore, you should not rush to write an effective research question.

A properly written research question has several characteristics.

- It should be clearly defined, and free of jargon.

- The question should be sufficiently focused to steer your research to its logical conclusion. It should summarize an outstanding issue or problem you want to investigate through research-by a literature review or an experimental study or a theoretical exercise.

- It must be addressed within your limited time frame and other available resources (e.g., money, equipment, assistants, etc.).

Major Steps to Write a Research Question

Often, you already have a broader subject that interests you. For example, say organismal biology. However, this alone will get you nowhere, whether you are a graduate student or professor writing for a grant. Following steps can help you to organize priorities.

- Narrow down your broad idea to a topic that can be investigated (e.g., biodiversity maintenance). It is easier to do this if you follow your own curiosity and are passionate about a particular research question or problem.

- Get a good and accurate feel for this general topic. Do some preliminary reading, on top of what you know already. Here, review papers are very helpful (note: these are not the same as meta-analyses!). Ask yourself, what has been done previously and more recently? How were these studies conducted? What hypotheses were tested? After some weeks at this, you should be able to identify key gaps in knowledge, i.e., new questions. You may also find conflicting evidence or inconsistencies in the literature. It is the time to revisit old questions again (i.e., do a replication).

- This step is often the hardest. Here, you must refine the topic further — and “run with it”. This is sometimes a matter of taste or style. Other times it can be dictated by what is most logistically feasible to do. In worst cases, you follow a fad or are told by your supervisor what to do. Following our example, you may go on to ask, “What are the ecological processes that contribute most to maintaining biodiversity”, or consider “How is biodiversity maintenance threatened in different ecosystems”. At this point, get the pen out. Write down potential “how” and “why” questions. Write full sentences, not fragments, to clarify your thinking.

- In the final step, you now scrutinize your list of candidate research questions. Be critical. You want to filter them. Ask yourself, can I actually find/collect the data necessary to address this question or problem? Will the method be feasible to do it? Is my question overly broad or narrow, or too subjective or objective?

Revise Your List

Aspects of feasibility are best tested in pilot studies or modeling scenarios. Here, you could factor in costs in terms of time, labor, and tools.

Review your questions carefully. Take these three for instance.

A) How is global biodiversity maintained?

B) Which biotic processes contribute most to maintaining local plant diversity in Western Amazonian forests?

C) What limited biodiversity at site X in Amazonia in the last 5 years?

(A) is much too broad – there are many possible processes, and these will vary geographically. However, (C) is too narrow and probably impossible to answer. (B) is neither too narrow nor too broad. It is specific enough to guide a research project and is feasible.

Likewise, a too objective question will limit you. Take “How many species of trees are there in New England forests”. This is factual information now. So it does not lend itself to argumentation. A more subjective question would be “What is the relationship between climate change and tree diversity dynamics in New England forests?” Also, try to avoid overly simplistic questions (e.g. “Where do forest fires occur most?”), which could be answered with Web searches nowadays. Instead, ask something more complex, like “What are the effects of logging on forest fire frequency and intensity?”

It is Okay to Modify Your Question

Be flexible and adaptable. A good research question is not permanent. Do not be afraid to modify your research question, revising it as you investigate it more. For example, key data may be lacking, or a new study is published that challenges some presumptions you had. In hypothesis-driven research, a good research question can easily be transformed into a testable hypothesis.

In sum, an effective research question is thoughtfully formulated. It interests not only you but potentially other researchers as well. It should follow accepted ethical standards (honesty, no stealing of ideas or fabrication of data, or no harming of human/animals subjects). A useful rule-of-thumb for a well-formulated research question is to follow Hulley et al .’s “FINER”: feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant.

In what part of your research do you find your research question?

Hi Stephen, Thank you for your question. Your research question should ideally be identified before you start your work. Research questions are based on research gaps and the latter becomes evident while conducting a comprehensive literature survey, prior to initiating any kind of research activity. Your entire work plan would be based on the question that you are trying to address through your research. Did you get a chance to install our FREE Mobile App . Make sure you subscribe to our weekly newsletter .

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Infographic

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

- Trending Now

Can AI Tools Prepare a Research Manuscript From Scratch? — A comprehensive guide

As technology continues to advance, the question of whether artificial intelligence (AI) tools can prepare…

Abstract Vs. Introduction — Do you know the difference?

Ross wants to publish his research. Feeling positive about his research outcomes, he begins to…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Demystifying Research Methodology With Field Experts

Choosing research methodology Research design and methodology Evidence-based research approach How RAxter can assist researchers

- Manuscript Preparation

- Publishing Research

How to Choose Best Research Methodology for Your Study

Successful research conduction requires proper planning and execution. While there are multiple reasons and aspects…

Top 5 Key Differences Between Methods and Methodology

While burning the midnight oil during literature review, most researchers do not realize that the…

How to Draft the Acknowledgment Section of a Manuscript

Discussion Vs. Conclusion: Know the Difference Before Drafting Manuscripts

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

In your opinion, what is the most effective way to improve integrity in the peer review process?

- Research Guides

Literature Review: A Self-Guided Tutorial

- 1. Identify the question

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Peer Review

- Reading the Literature

- Using Concept Maps

- Developing Research Questions

- Considering Strong Opinions

- 2. Review discipline styles

- Super Searching

- Finding the Full Text

- Citation Searching This link opens in a new window

- When to stop searching

- Citation Management

- Annotating Articles Tip

- 5. Critically analyze and evaluate

- How to Review the Literature

- Using a Synthesis Matrix

- 7. Write literature review

Identify the Question

In some cases, such as for a course assignment or a research project you're working on with a faculty member, your research question will be determined by your professor. If that's the case, you can move on to the next step . Otherwise, you may need to explore questions on your own.

A few suggestions:

Watch the videos in this section for advice on developing your research question and considerations related to choosing a topic for which you have a strong opinion.

- << Previous: Using Concept Maps

- Next: Developing Research Questions >>

- Last Updated: Jul 18, 2024 4:11 PM

- URL: https://libguides.williams.edu/literature-review

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Where to Put the Research Question in a Paper

Silke Haidekker has a PhD in Pharmacology from the University of Hannover. She is a Clinical Research Associate in multiple pharmaceutical companies in Germany and the USA. She now works as a full-time medical translator and writer in a small town in Georgia.

Of Rats and Panic Attacks: A Doctoral Student’s Tale

You would probably agree that the time spent writing your PhD dissertation or thesis is not only a time of taking pride or even joy in what you do, but also a time riddled with panic attacks of different varieties and lengths. When I worked on my PhD thesis in pharmacology in Germany many years back, I had my first panic attack as I first learned how to kill rats for my experiments with a very ugly tool called a guillotine! After that part of the procedure, I was to remove and mash their livers, spike them with Ciclosporin A (an immunosuppressive agent), and then present the metabolites by high-pressure liquid chromatography.

Many rats later, I had another serious panic attack. It occurred at the moment my doctoral adviser told me to write my first research paper on the Ciclosporin A metabolites I had detected in hundreds of slimy mashes of rat liver. Sadly, this second panic attack led to a third one that was caused by living in the pre-internet era, when it was not as easy to access information about how to write research papers .

How I got over writing my first research paper is now ancient history. But it was only years later, living in the USA and finally being immersed in the language of most scientific research papers, that my interest in the art of writing “good” research papers was sparked during conferences held by the American Medical Writers Association , as well as by getting involved in different writing programs and academic self-study courses.

How to State the Research Question in the Introduction Section

Good writing begins with clearly stating your research question (or hypothesis) in the Introduction section —the focal point on which your entire paper builds and unfolds in the subsequent Methods, Results, and Discussion sections . This research question or hypothesis that goes into the first section of your research manuscript, the Introduction, explains at least three major elements:

a) What is known or believed about the research topic?

B) what is still unknown (or problematic), c) what is the question or hypothesis of your investigation.

Some medical writers refer to this organizational structure of the Introduction as a “funnel shape” because it starts broadly, with the bigger picture, and then follows one scientifically logical step after the other until finally narrowing down the story to the focal point of your research at the end of the funnel.

Let’s now look in greater detail at a research question example and how you can logically embed it into the Introduction to make it a powerful focal point and ignite the reader’s interest about the importance of your research:

a) The Known

You should start by giving your reader a brief overview of knowledge or previous studies already performed in the context of your research topic.

The topic of one of my research papers was “investigating the value of diabetes as an independent predictor of death in people with end-stage renal disease (ESRD).” So in the Introduction, I first presented the basic knowledge that diabetes is the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and thus made the reader better understand our interest in this specific study population. I then presented previous studies already showing that diabetes indeed seems to represent an independent risk factor for death in the general population. However, very few studies had been performed in the ESRD population and those only yielded controversial results.

Example : “It seems well established that there is a link between diabetic nephropathy and hypertensive nephropathy and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in Western countries. In 2014, 73% of patients in US hospitals had comorbid ESRD and type 2 diabetes (1, 2, 3)…”

b) The Unknown

In our example, this “controversy” flags the “unknown” or “problematic” and therefore provides strong reasons for why further research is justified. The unknown should be clearly stated or implied by using phrases such as “were controversial” (as in our example), “…has not been determined,” or “…is unclear.” By clearly stating what is “unknown,” you indicate that your research is new. This creates a smooth transition into your research question.

Example : “However, previous studies have failed to isolate diabetes as an independent factor, and thus much remains unknown about specific risk factors associated with both diabetes and ESRD .”

c) The Research Question (Hypothesis)

Your research question is the question that inevitably evolves from the deficits or problems revealed in the “Unknown” and clearly states the goal of your research. It is important to describe your research question in just one or two short sentences, but very precisely and including all variables studied, if applicable. A transition should be used to mark the transition from the unknown to the research question using one word such as “therefore” or “accordingly,” or short phrases like “for this reason” or “considering this lack of crucial information.”

In our example, we stated the research question as follows:

Example : “Therefore, the primary goal of our study was to perform a Kaplan-Meier survival study and to investigate, by means of the Cox proportional hazard model, the value of diabetes as an independent predictor of death in diabetic patients with ESRD.”

Note that the research question may include the experimental approach of the study used to answer the research question.

Another powerful way to introduce the research question is to state the research question as a hypothesis so that the reader can more easily anticipate the answer. In our case, the question could be put as follows:

Example : “To test the hypothesis that diabetes is an independent predictor of death in people with ESRD, we performed a Kaplan-Survival study and investigated the value of diabetes by means of the Cox proportional hazard model.”

Note that this sentence leads with an introductory clause that indicates the hypothesis itself, transitioning well into a synopsis of the approach in the second half of the sentence.

The generic framework of the Introduction can be modified to include, for example, two research questions instead of just one. In such a case, both questions must follow inevitably from the previous statements, meaning that the background information leading to the second question cannot be omitted. Otherwise, the Introduction will get confusing, with the reader not knowing where that question comes from.

Begin with your research purpose in mind

To conclude, here is my simple but most important advice for you as a researcher preparing to write a scientific paper (or just the Introduction of a research paper) for the first time: Think your research question through precisely before trying to write it down; have in mind the reasons for exactly why you wanted to do this specific research, what exactly you wanted to find out, and how (by which methods) you did your investigation. If you have the answers to these questions in mind (or even better, create a comprehensive outline ) before starting the paper, the actual writing process will be a piece of cake and you will finish it “like a rat up a drainpipe”! And hopefully with no panic attacks.

Wordvice Resources

Before submitting your master’s thesis or PhD dissertation to academic journals for publication, be sure to receive proofreading services (including research paper editing , manuscript editing , thesis editing , and dissertation editing ) to ensure that your research writing is error-free. Impress your journal editor and get into the academic journal of your choice.

- Joyner Library

- Laupus Health Sciences Library

- Music Library

- Digital Collections

- Special Collections

- North Carolina Collection

- Teaching Resources

- The ScholarShip Institutional Repository

- Country Doctor Museum

- ECU Libraries

- Frequently Asked Questions

Q. How do I identify a research study?

- 46 Circulation

- 19 Computing

- 27 Database List Help

- 51 General Information

- 26 Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- 10 Laupus Health Sciences Library

- 3 Library Staff Profiles

- 9 Music Library

- 60 Research Help

- 16 Teaching Resources Center (TRC)

Please note:

Answered by: david hisle last updated: aug 30, 2022 views: 66353.

These guidelines can help you identify a research study and distinguish an article that presents the findings of a research study from other types of articles.

- Ask a research question

- Identify a research population or group

- Describe a research method

- Test or measure something

- Summarize the results

Research studies are almost always published in peer-reviewed (scholarly) journals. The articles often contain headings similar to these: Literature Review, Method, Results, Discussion , and Conclusion .

Articles that review other studies without presenting new research results are not research studies. Examples of article types that are NOT research studies include:

- literature reviews

- meta-analyses

- case studies

- comments or letters relating to previously-published research studies

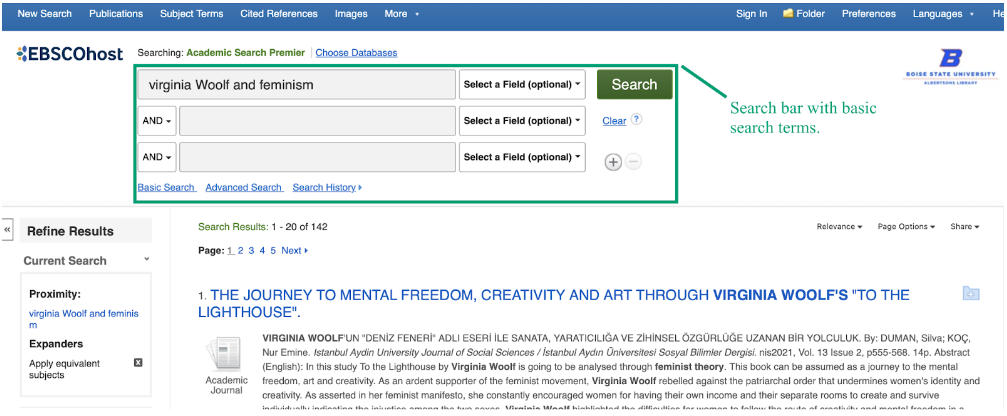

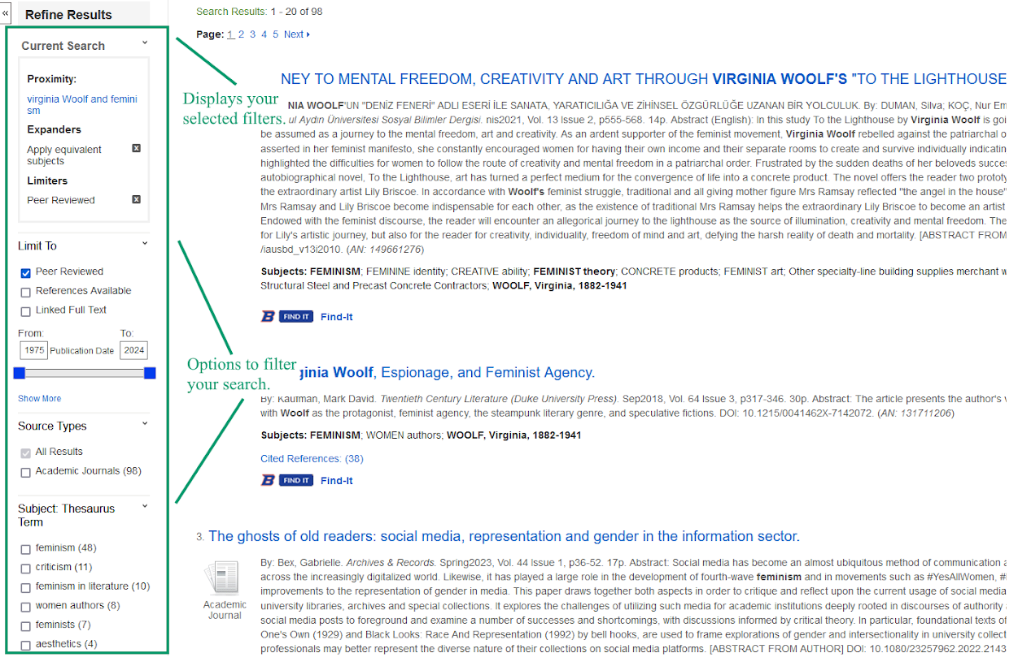

Some databases allow you to limit by publication type. Use this feature to help identify research studies. Here are tips for limiting by publication type in several popular databases:

- Click on the Advanced Search button.

- Type your search terms in the top boxes.

- In the area below the search boxes, find the box labeled "Publication Type".

- Select "Peer Reviewed Journal"

- empirical study

- follow-up study

- longitudinal study

- prospective study

- retrospective study

- treatment outcomes study

ERIC via EBSCO host :

- In the area below the search boxes, find the box labeled "Journal or Document".

- Select "Journal Articles" from the menu choices.