How To Implement Effective Strategic Planning In Healthcare

Are you feeling overwhelmed and uncertain about the future?

According to Deloitte , “The global healthcare sector stands at a crossroads in 2024, poised for profound changes. The future of global healthcare is likely to be shaped by innovation, sustainability, social care integration, cost management, and workforce adaptation.”

If you work in the healthcare industry, you know firsthand how quickly things can change. As technology advances, regulations change, the population ages, and new diseases evolve at lightning speed, it can be tough to keep up.

That's why implementing an effective strategic planning process that is execution-ready is so important. It's a tool that helps healthcare organizations prioritize their goals, anticipate potential roadblocks, and quickly adapt to seize new opportunities.

Whether you’re a manager or a top-level executive, this article will provide valuable insights and guidance to help you develop and execute a successful strategic plan.

We'll also show you how Cascade can help you successfully plan, execute, and track your healthcare strategy in one centralized location. Plus, as a bonus, we'll provide a free strategic planning template prefilled with healthcare examples to help you get started.

So, let's dive in and discover how strategic planning can help you navigate the changing landscape of the healthcare environment and achieve your organization’s goals.

Strategic Planning In Healthcare: What Is It?

Strategic planning in healthcare helps you set business goals and decide how to allocate resources to achieve these goals. It involves looking at your organization’s internal and external environments using established strategic tools .

Doing so lets you develop a strategic plan outlining what you want to achieve and an action plan to get there. Think of it like building a roadmap that helps you get to where you want to go.

With a healthcare strategy, you’ll have a framework for improved decision-making that is aligned with your overarching business objectives . This ensures you’re moving towards your long-term goals and objectives, even when making short-term decisions.

Examples Of Strategic Planning In Healthcare

Strategic planning can significantly enhance the operational efficiency and service quality of healthcare organizations. Here are some specific examples of how you can use strategic planning:

- Boosting Patient Care Quality : Tackle specific challenges like lowering the rates of hospital-acquired infections or enhancing the coordination of patient care. By pinpointing these areas, you can implement targeted improvements that directly benefit patient outcomes.

- Optimizing Staff and Resource Management : Utilize data analytics to make evidence-based decisions regarding staffing and resource distribution. This approach ensures that your workforce is optimally aligned with patient needs, and your resource allocation is efficient, contributing to a more effective healthcare system.

- Exploring New Avenues for Growth : Seize opportunities to expand your services and reach by integrating telehealth, offering home healthcare solutions, or developing specialized programs tailored to unique patient demographics. Such strategic initiatives can open new revenue streams and meet the evolving needs of your community.

- Improving Financial Health : Identify strategies for cost reduction and revenue enhancement, such as streamlining supply chain operations or venturing into untapped markets. These measures can bolster your organization's financial stability, allowing for reinvestment in key areas.

- Fostering Partnerships for Comprehensive Care : Establish collaborations with community organizations, other healthcare providers and facilities, or specialists to broaden your service offerings and improve patient care. Partnerships can lead to a more integrated care model that addresses a wide range of patient needs.

📚 Recommended read: Strategy study: The Ramsay Health Care Growth Study

Healthcare Strategic Planning: Why Is It Important?

Strategic planning in healthcare is more than just setting goals; it's about ensuring your organization is on the right track for success.

These are some of the countless benefits of strategic planning in healthcare:

Boost profitability

Strategic planning helps healthcare leaders improve their organization’s financial performance and achieve long-term sustainability. It's about using resources wisely, cutting costs where possible, and smoothing out inefficiencies by streamlining processes and creating better strategic initiatives to increase patient volume and improve experience.

Additionally, strategic planning plays a crucial role in uncovering new opportunities for revenue, enabling healthcare organizations to diversify their sources of income.

Enhance collaboration and engagement

Strategic planning in healthcare goes beyond identifying operational challenges; it's about bringing to light the issues that affect our teams daily, such as the strain of long work hours. When staff feel overburdened, their motivation dips, leading to decreased engagement and higher turnover rates.

By articulating a clear vision for the organization and actively involving employees in the strategic planning process, we can significantly boost morale. It's about making sure everyone feels seen and heard, understanding that their contributions are valued. This inclusive approach not only enhances team engagement but also encourages stronger retention.

Strategic planning also fosters collaboration across different teams and business units within the healthcare organization. By working together towards common goals, departments can better align their efforts, share insights, and support each other in achieving the organization's objectives. This synergy not only improves efficiency but also builds a more cohesive and motivated workforce.

💡Pro Tip : Ensure your vision statement is crystal clear organization-wide for unified strategic alignment.

Increase efficiency

Strategic planning helps you align your operational activities with the organization’s goals. This ensures that every action contributes toward achieving your business objectives. Strategic planning also empowers healthcare leaders, providing them with the insights needed to make resource allocation decisions wisely in the dynamic healthcare landscape.

Improve communication

A good strategic plan should be shared with all stakeholders so they can form a clear picture of how their actions affect a future outcome. This transparency promotes better communication within the organization, as employees align their efforts towards achieving a common goal. The end result is a more collaborative environment where the collective focus is on attaining shared objectives.

Drive alignment and strategy execution

Involving key stakeholders in the strategic planning process is crucial for aligning your healthcare organization's goals with its overarching strategy. This ensures that everyone, from top management to frontline staff, is aligned and moving in the same direction. Achieving this level of strategic harmony across the organization reduces confusion and clarifies the collective mission, paving the way for successful strategy implementation. This collaborative approach not only fosters a unified effort towards common objectives but also enhances the overall effectiveness of the organization's strategic initiatives.

💡Pro Tip : Ensure you balance a top-down and bottom-up for enhanced vertical and horizontal strategic alignment .

5 Strategic Planning Tools For Your Healthcare Strategy

Here’s a list of strategy tools and frameworks that can help you identify gaps in your healthcare strategy, prioritize strategic initiatives, and develop business goals:

1. Balanced Scorecard (BSC)

The Balanced Scorecard translates strategic goals into measurable indicators or metrics to help you balance four critical organizational perspectives: financial, customer, internal processes, and organizational capacity.

Using this tool ensures that your organization aligns with your strategic objectives and that you’re measuring the right KPIs to track progress toward those objectives.

2. Objectives and key results (OKR)

The OKR framework sets specific and measurable objectives and tracks progress toward them using key results. Objectives should be ambitious and challenging but achievable. Meanwhile, key results should be specific and measurable and have defined target values.

This framework promotes accountability and transparency since everyone works toward the same goals.

3. Political, economic, sociocultural, and technological (PEST) analysis

PEST analysis helps you understand the external factors that may impact your operations. By using this tool, you can identify potential opportunities and threats so you can anticipate and respond to changes in the external environment.

For example, PEST can help you identify a shift toward consumer-driven healthcare. Consequently, this enables you to invest in telemedicine and other digital healthcare technologies to meet patients’ changing needs.

4. Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats (SWOT) analysis

SWOT analysis is a simple yet powerful way to identify the internal and external factors that can impact your organization’s success.

For example, if you discover that staffing levels are a weakness, you may decide to invest in staff training or recruitment programs. Or, if you identify an opportunity to expand into a new service area, you may choose to allocate resources for the expansion.

By leveraging your organization's strengths through this analysis, you can craft targeted strategies that address challenges and capitalize on opportunities for sustained success.

5. Theory of change (TOC)

The theory of change is a framework that helps your organization articulate the desired outcomes and specific steps you need to take to achieve them. This model provides a more structured approach to achieving goals by identifying the inputs required for success.

For example, if you want to reduce hospital readmissions, you may use the theory of change to identify the inputs needed (staff training on patient education), activities needed (discharge planning), and desired outcomes (reduction in hospital readmissions). By mapping out this logic model and continuously evaluating the initiative, your organization can adjust its activities to achieve your desired outcomes and improve the quality of care for your patients.

📚 Recommended read: 26 Best Strategy Tools For Your Organization in 2024

How To Implement A Strategic Plan In Healthcare

Implementing a strategic healthcare plan can be challenging. Follow this step-by-step framework to help you get started.

💡Pro Tip : Streamline your healthcare strategy planning, execution, and tracking with Cascade Strategy Execution Platform . It serves as a centralized hub for enhanced decision-making and accelerated results. Unsure of where to begin? Kickstart your strategic planning process with our complimentary pre-filled healthcare strategy template .

1. Establish goals

The first step is to establish clear and measurable goals. These goals should align with your organization’s mission and vision , and be SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound).

Examples of goals in healthcare include reducing hospital readmission rates, improving patient satisfaction scores, or increasing revenue.

👉🏻How Cascade can help? With Cascade's Planner feature , you can simplify the process of constructing your strategies. It provides a structured approach, making it effortless to break down complex high-level initiatives into actionable outcomes.

2. Set milestones and measure progress

Once you establish goals, it’s important to set milestones and measure progress regularly. This allows your organization to track its progress toward achieving its goals, identify areas for improvement, and make necessary adjustments.

Make sure to establish a timeframe for your milestones, whether it's monthly, quarterly, or yearly, depending on the nature of your goal.

👉🏻How Cascade can help? Cascade's Metrics Library offers a centralized repository for your business metrics, allowing you to seamlessly link these metrics to your plan's Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Integrating core metrics becomes a breeze, whether they originate from your business systems, data lakes, Business Intelligence (BI) tools, or spreadsheets.

3. Develop an execution plan

To successfully achieve your goals, it is essential to have a comprehensive execution plan . This plan should detail all the necessary activities and strategies that will guide you toward success.

An effective execution plan must include a well-structured timeline, a checklist of required resources, and clearly defined responsibilities for each action or project.

👉🏻How Cascade can help? Cascade's Alignment Maps feature empowers you to monitor the interactions between activities by documenting and examining dependencies, blockers, and risks that might arise during your strategic journey. This ensures a smooth path to successful strategy execution.

4. Monitor performance and adapt as needed

Once the plan is in motion, you should monitor its performance regularly and make necessary adjustments when you notice deviations. You must be flexible and willing to change your execution plan as needed.

For example, if the original plan doesn't turn out to be effective, it's important to quickly reevaluate and come up with an alternative strategy.

👉🏻How Cascade can help? Cascade's Dashboards & Reports allow you to gain accurate, real-time insights into your strategic performance, enabling you to easily share this information with your stakeholders.

5. Communicate regularly

Communication is key in implementing a strategic plan . Each stakeholder should understand their role and how their work fits into the big picture. You must inform them of progress toward the established goals, any changes to the execution plan, and other relevant information. This will help you build trust and get buy-in, which are essential for successful strategy execution.

6. Celebrate successes

Celebrating successes helps maintain motivation and momentum. It shows staff and stakeholders that their hard work is paying off. This can be done in various ways, such as recognizing staff members who have contributed significantly to the plan or sharing positive feedback from patients.

Positive reinforcement will motivate employees to keep striving to achieve your organization’s objectives.

📚 Recommended read: How Parker University uses Cascade to help them hold a position as a leader in Patient-Centric Healthcare

Case Study: Perley Health’s Strategic Ambition

Perley Health, a healthcare organization dedicated to improving care for veterans and seniors, faced some significant challenges in their strategic planning and execution processes. These challenges included making assumptions about the stability of the external environment in their long-term planning, inconsistency in how different departments planned and reported, a lack of clarity in how they measured success, and a somewhat fragmented approach to strategic and departmental plans.

Perley Health's journey toward strategic improvement began with the adoption of Cascade, a pivotal decision for them. Initially, they used Cascade to bring together all their strategic plans and initiatives, which brought about greater transparency and alignment with their organizational priorities. This not only made resource allocation more efficient but also provided a standardized way to measure results, making it easier to discuss return on investment (ROI) and track progress systematically.

Empowered by Cascade's capabilities, the management and various teams could now propose forward-thinking initiatives with a clear view of how they aligned with strategic priorities. This sped up decision-making and made funding allocation more precise.

With the right tools in place, Perley Health is now confidently working towards their goal of doubling senior care and establishing themselves as a center of excellence in frailty-informed care. They keep a close eye on their progress using the Cascade platform.

This case underscores the critical importance of strategic planning in navigating the complexities of healthcare, demonstrating a clear path to achieving and surpassing organizational objectives.

📚 Read the complete Perley Health Case Study!

Execute Your Healthcare Strategy With Cascade 🚀

Take the guesswork out of strategic planning in healthcare. With Cascade , you can easily create an execution plan customized to your goals and objectives, including assigning initiatives and setting deadlines for each team member involved.

Take a look at this example of a healthcare strategic plan in Cascade:

You can also leverage easy-to-use dashboards and visualizations that provide real-time data on your progress toward your goals.

Here’s an example of a real-time dashboard:

Cascade lets you collaborate with your team, assign responsibilities, and communicate progress, ensuring everyone is aligned and working toward the same objectives.

Whether you run a small clinic or a large healthcare organization, Cascade will help you make strategic planning in healthcare a breeze. Learn more about Cascade for healthcare !

Looking for a tailored tour of our platform? Book a demo with one of our Strategy Execution experts.

Popular articles

Strategic Initiatives Guide: Types, Development & Execution

.png)

20 Free Strategic Plan Templates (Excel & Cascade) 2024

.png)

How To Write KPIs In 4 Steps + Free KPI Template

.png)

35 Noteworthy Vision Statement Examples (+ Free Template)

Your toolkit for strategy success.

4 Keys to Successful Healthcare Management

By Arial Starks

The business of healthcare continues to grow at an impressive rate , and more healthcare professionals are seeking healthcare management roles that accompany this growth. Healthcare workers aspiring to move into management should take note of a few fundamental keys to success. We sat down with Burch Wood , Director of Healthcare Programs, and Anna Kennedy , Program Coordinator, Health Care, at Vanderbilt Business to learn the keys to successful healthcare management.

1. Gain Business Knowledge

One of the most common reasons healthcare professionals consider returning to school in the middle of their careers is to gain knowledge in areas where they are lacking. This knowledge gap tends to be centered around business concepts that are essential to healthcare management. Wood says in order for a healthcare professional to make the transition to administrative roles, they need to explore pursuing a program like the Master of Management in Health Care (MMHC) where they will gain that core business training.

“That’s why we have the MMHC, to give those who are tasked with the job of running a healthcare organization the business knowledge that will make them effective leaders,” he said.

2. Learn to lead a team/organization

Anna Kennedy

Healthcare professionals can be excellent at what they do, but if they are not able to lead a team or organization, Wood says it could prevent them from reaching their maximum career potential. “In the healthcare field, you have to learn how to manage a very diverse group of people,” he says. “You have to know how to get the most out of them and how to keep them motivated day after day.”

Healthcare management programs like the MMHC teach professionals to work as part of a team and can equip them with the tools they need to effectively lead a group of people. “The MMHC bringing different types of people together, communicating and learning to speak the same (business) language, (that) is part of what you get as the business fundamentals of the program,” says Kennedy.

3. Think and act strategically

One of the essential skills you learn in the Vanderbilt MMHC program is how to approach work with a strategic mindset. Through courses like management and strategy , professionals learn the importance of effective decision-making, which makes them better overall leaders in turn.

“At the end of the day, in order to be a good administrator, you have to understand and be able to answer questions like ‘what’s your 5 and 10 year plan?’ or even ‘how do the people you manage fit into that plan?” says Wood. “I believe part of why Vanderbilt organizes the MMHC program like we do is to give these healthcare professionals a taste of that early on.”

4. Be a life-long learner

A major key to success in any industry, but especially in the ever-changing world of healthcare management, is a commitment to life-long learning. As technology and concepts in healthcare continue to evolve, Kennedy says the ability to learn and adapt sets a person apart from the rest. “That’s what we look for in a candidate for the MMHC program, and it is almost always going to translate to their professional life as well,” she says. “It’s not what you learned 10 years ago, but how you can continue learning over the next 10 years.”

Wood notes that in order to make positive change in your organization, you have to be willing to learn and change as the industry progresses. “You have to have someone who is not only willing to accept change but also be a part of that change,” he says. “The people who are the most successful are the ones who see change coming down the pike and instead of running from it, they harness it and try to make something good out of it.”

Optimal success will look different to everyone in healthcare management, but as Wood says, as long as you are able to make positive change for your organization and in the lives of the people who depend on you as part of that organization, you can consider yourself successful.

To learn more about healthcare management at Vanderbilt Business, click here .

Featured News MMHC News News Press Releases

Other Stories

Want to learn more about MMHC?

The future of healthcare: Value creation through next-generation business models

The healthcare industry in the United States has experienced steady growth over the past decade while simultaneously promoting quality, efficiency, and access to care. Between 2012 and 2019, profit pools (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, or EBITDA) grew at a compound average growth rate of roughly 5 percent. This growth was aided in part by incremental healthcare spending that resulted from the 2010 Affordable Care Act. In 2020, subsidies for qualified individual purchasers on the marketplaces and expansion of Medicaid coverage resulted in roughly $130 billion 1 Federal Subsidies for Health Insurance Coverage for People Under Age 65: CBO and JCT’s March 2020 Projections, Congressional Budget Office, Washington, DC, September 29, 2020, cbo.gov. 2 Includes adults made eligible for Medicaid by the ACA and marketplace-related coverage and the Basic Health Program. of incremental healthcare spending by the federal government.

The next three years are expected to be less positive for the economics of the healthcare industry, as profit pools are more likely to be flat. COVID-19 has led to the potential for economic headwinds and a rebalancing of system funds. Current unemployment rates (6.9 percent as of October 2020) 3 The employment situation—October 2020 , US Department of Labor, November 6, 2020, bls.gov. indicate some individuals may move from employer-sponsored insurance to other options. It is expected that roughly between $70 billion and $100 billion in funding may leave the healthcare system by 2022, compared with the expected trajectory pre-COVID-19. The outflow is driven by coverage shifts out of employer-sponsored insurance, product buy-downs, and Medicaid rate pressures from states, partially offset by increased federal spending in the form of subsidies and cost sharing in the Individual market and in Medicaid funding.

Underlying this broader outlook are chances to innovate (Exhibit 1). 4 Smit S, Hirt M, Buehler K, Lund S, Greenberg E, and Govindarajan A, “ Safeguarding our lives and our livelihoods: The imperative of our time ,” March 23, 2020, McKinsey.com. Innovation may drive outpaced growth in three categories: segments that are anticipated to rebound from poor performance over recent years, segments that benefit from shifting care patterns that result directly from COVID-19, and segments where growth was expected pre-COVID-19 and remain largely unaffected by the pandemic. For the payer vertical, we estimate profit pools in Medicaid will likely increase by more than 10 percent per annum from 2019 to 2022 as a result of increased enrollment and normalized margins following historical lows. In the provider vertical, the rapid acceleration in the use of telehealth and other virtual care options spurred by COVID-19 could continue. 5 Bestsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, and Rost J, “ Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? ” May 29, 2020, McKinsey.com. Growth is expected across a range of sub-segments in the services and technology vertical, as specialized players are able to provide services at scale (for example, software and platforms and data and analytics). Specialty pharmacy is another area where strong growth in profit pools is likely, with between 5 and 10 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR) expected in infusion services and hospital-owned specialty pharmacy sub-segments.

Strategies that align to attractive and growing profit pools, while important, may be insufficient to achieve the growth that incumbents have come to expect. For example, in 2019, 34 percent of all revenue in the healthcare system was linked to a profit pool that grew at greater than 5 percent per year (from 2017 to 2019). In contrast, we estimate that only 13 percent of revenue in 2022 will be linked to profit pools growing at that rate between 2019 and 2022. This estimate reflects that profit pools are growing more slowly due to factors that include lower membership growth, margin pressure, and lower revenue growth. This relative scarcity in opportunity could lead to increased competition in attractive sub-segments with the potential for profits to be spread thinly across organizations. Developing new and innovative business models will become important to achieve the level of EBITDA growth observed in recent years and deliver better care for individuals. The good news is that there is significant opportunity, and need, for innovation in healthcare.

New and innovative business models across verticals can generate greater value and deliver better care for individuals

Glimpse into profit pool analyses and select sub-segments.

Within the context of these overarching observations, the projections for specific sub-segments are nuanced and tightly connected to the specific dynamics each sub-segment is currently facing:

- Payer—Small Group: Small group has historically seen membership declines and we expect this trend to continue and/or accelerate in the event of an economic downturn. Membership declines will increase competition and put pressure on incumbent market leaders to both maintain share and margin as membership declines, but fixed costs remain.

- Payer—Medicare Advantage: Historic profit pool growth in the Medicare Advantage space has been driven by enrollment gains that result from demographic trends and a long-term trend of seniors moving from traditional Medicare fee-for-service programs to Medicare Advantage plans that have increasingly offered attractive ancillary benefits (for example, dental benefits, gym memberships). Going forward, we expect Medicare members to be relatively insulated from the effects of an economic downturn that will impact employers and individuals in other payer segments.

- Provider—General acute care hospitals: Cancelation of elective procedures due to COVID-19 is expected to lead to volume and revenue reductions in 2019 and 2020. Though volume is expected to recover partially by 2022, growth will likely be slowed due to the accelerated shift from hospitals to virtual care and other non-acute settings. Payer mix shifts from employer-sponsored to Medicaid and uninsured populations in 2020 and 2021 are also likely to exert downward pressure on hospital revenue and EBITDA, possibly driving cost-optimization measures through 2022.

- Provider—Independent labs: COVID-19 testing is expected to drive higher than average utilization growth in independent labs through 2020 and 2021, with more typical utilization returning by 2022. However, labs may experience pressure on revenue and EBITDA growth as the payer mix shifts to lower-margin segments, offsetting some of the gains attributed to utilization.

- Provider—Virtual office visits: Telehealth has helped expand access to care at a time when the pandemic has restricted patients’ ability to see providers in person. Consumer adoption and stickiness, along with providers’ push to scale-up telehealth offerings, are expected to lead to more than 100 percent growth per annum in the segment from 2019 to 2022, going beyond traditional “tele-urgent” to more comprehensive virtual care.

- HST—Medical financing: The medical financing segment may be negatively impacted in 2020 due to COVID-19, as many elective services for which financing is used have been deferred. However, a quick bounce-back is expected as more patients lacking healthcare coverage may need financing in 2021, and as providers may use medical financing as a lever to improve cash reserves.

- HST—Wearables: Looking ahead, the wearables segment is expected to see a slight dip in 2020 due to COVID-19, but is expected to rebound in 2021 and 2022 given consumer interest in personal wellness and for tracking health indicators.

- Pharma services—Pharmacy benefit management: The growth is expected to return to baseline expectations by 2022 after an initial decline in 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19-driven decrease in prescription volume.

New and innovative business models are beginning to show promise in delivering better care and generating higher returns. The existence of these models and their initial successes are reflective of what we have observed in the market in recent years: leading organizations in the healthcare industry are not content to simply play in attractive segments and markets, but instead are proactively and fundamentally reshaping how the industry operates and how care is delivered. While the recipe across verticals varies, common among these new business models are greater alignment of incentives typically involving risk bearing, better integration of care, and use of data and advanced analytics.

Payers—Next-generation managed care models

For payers, the new and innovative business models that are generating superior returns are those that incorporate care delivery and advanced analytics to better serve individuals with increasingly complex healthcare needs (Exhibit 2). As chronic disease and other long-term conditions require more continuous management supported by providers (for example, behavioral health conditions), these next-generation managed care models have garnered notice. Nine of the top ten payers have made acquisitions in the care delivery space. Such models intend to reorient the traditional payer model away from an operational focus on financing healthcare and pricing risk, and toward more integrated managed care models that better align incentives and provide higher-quality, better experience, lower-cost, and more accessible care. Payers that deployed next-generation managed care models generate 0.5 percentage points of EBITDA margin above average expectations after normalizing for payer scale, geographical footprint, and segment mix, according to our research.

The evidence for the effectiveness of these next-generation care models goes beyond the financial analysis of returns. We observe that these models are being deployed in those geographies that have the greatest opportunity to positively impact individuals. Those markets with 1) a critical mass of disease burden, 2) presence of compressible costs (the opportunity for care to be redirected to lower-cost settings), and 3) a market structure conducive to shifting to higher-value sites of care, offer substantial ways to improve outcomes and reduce costs. (Exhibit 3).

Currently, a handful of payers—often large national players with access to capital and geographic breadth that enables acquisition of at-scale providers and technologies—have begun to pursue such models. Smaller payers may find it more difficult to make outright acquisitions, given capital constraints and geographic limitations. M&A activity across the care delivery landscape is leaving smaller and more localized assets available for integration and partnership. Payers may need to increasingly turn toward strategic partnerships and alliances to create value and integrate a range of offerings that address all drivers of health.

Providers—reimagining care delivery beyond the hospital

For health systems, through an investment lens, the ownership and integration of alternative sites of care beyond the hospital has demonstrated superior financial returns. Between 2013 and 2018, the number of transactions executed by health systems for outpatient assets increased by 31 percent, for physician practices by 23 percent, and for post-acute care assets by 13 percent. At the same time, the number of hospital-focused deals declined by 6 percent. In addition, private equity investors and payers are becoming more active dealmakers in these non-acute settings. 6 CapitalIQ, Dealogic, and Irving Levin Associates. 7 In 2018, around 40 percent of all post-acute and outpatient deals were completed by an acquirer other than a traditional provider.

As investment is focused on alternative sites of care, we observe that health systems pursuing diversified business models that encompass a greater range of care delivery assets (for example, physician practices, ambulatory surgery centers, and urgent care centers) are generating returns above expectations (Exhibit 4). By offering diverse settings to receive care, many of these systems have been able to lower costs, enhance coordination, and improve patient experience while maintaining or enhancing the quality of the services provided. Consistent with prior research, 8 Singhal S, Latko B, and Pardo Martin C, “ The future of healthcare: Finding the opportunities that lie beneath the uncertainty ,” January 31, 2018, McKinsey.com. systems with high market share tend to outperform peers with lower market share, potentially because systems with greater share have greater ability not only to ensure referral integrity but also to leverage economies of scale that drive efficiency.

The extent of this outperformance, however, varies by market type. For players with top quartile share, the difference in outperformance between acute-focused players and diverse players is less meaningful. Contrastingly, for bottom quartile players, the increase in value provided by presence beyond the acute setting is more significant. While there may be disadvantages for smaller and sub-scale providers, opportunities exist for these players—as well as new entrants and attackers—to succeed by integrating offerings across the care continuum.

These new models and entrants and their non-acute, technology-enabled, and multichannel offerings can offer a different vision of care delivery. Consumer adoption of telehealth has skyrocketed, from 11 percent of US consumers using telehealth in 2019 to 46 percent now using telehealth to replace canceled healthcare visits. Pre-COVID-19, the total annual revenues of US telehealth players were an estimated $3 billion; with the acceleration of consumer and provider adoption and the extension of telehealth beyond virtual urgent care, up to $250 billion of current US healthcare spend could be virtualized. 9 Bestsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, and Rost J, “ Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? ” May 29, 2020, McKinsey.com. These early indications suggest that the market may be shifting toward a model of innovative tech-enabled care, one that unlocks value by integrating digital and non-acute settings into a comprehensive, coordinated, and lower-cost offering. While functional care coordination is currently still at the early stages, the potential of technology and other alternative settings raises the question of the role of existing acute-focused providers in a more integrated and digital world.

Would you like to learn more about our Healthcare Systems & Services Practice ?

Healthcare services and technology—innovation and integration across the value chain.

Growth in the healthcare services and technology vertical has been material, as players are bringing technology-enabled services to help improve patient care and boost efficiency. Healthcare services and technology companies are serving nearly all segments of the healthcare ecosystem. These efforts include working with payers and providers to better enable the link between actions and outcomes, to engage with consumers, and to provide real-time and convenient access to health information. Since 2014, a large number and value of deals have been completed: more than 580 deals, or $83 billion in aggregate value. 10 Includes deals over $10 million in value. 11 Analysis from PitchBook Data, Inc. and McKinsey Healthcare Services and Technology domain profit pools model. Venture capital and private equity have fueled much of the innovation in the space: more than 80 percent 12 Includes deals over $10 million in value. of deal volume has come from these institutional investors, while more traditional strategic players have focused on scaling such innovations and integrating them into their core.

Driven by this investment, multiple new models, players, and approaches are emerging across various sub-segments of the technology and services space, driving both innovation (measured by the number of venture capital deals as a percent of total deals) and integration (measured by strategic dollars invested as a percent of total dollars) with traditional payers and providers (Exhibit 5). In some sub-segments, such as data and analytics, utilization management, provider enablement, network management, and clinical information systems, there has been a high rate of both innovation and integration. For instance, in the data and analytics sub-segment, areas such as behavioral health and social determinants of health have driven innovation, while payer and provider investment in at-scale data and analytics platforms has driven deeper integration with existing core platforms. Other sub-segments, such as patient engagement and population health management, have exhibited high innovation but lower integration.

Traditional players have an opportunity to integrate innovative new technologies and offerings to transform and modernize their existing business models. Simultaneously, new (and often non-traditional) players are well positioned to continue to drive innovation across multiple sub-segments and through combinations of capabilities (roll-ups).

Pharmacy value chain—emerging shifts in delivery and management of care

The profit pools within the pharmacy services vertical are shifting from traditional dispensing to specialty pharmacy. Profits earned by retail dispensers (excluding specialty pharmacy) are expected to decline by 0.5 percent per year through 2022, in the face of intensifying competition and the maturing generic market. New modalities of care, new care settings, and new distribution systems are emerging, though many innovations remain in early stages of development.

Specialty pharmacy continues to be an area of outpaced growth. By 2023, specialty pharmacy is expected to account for 44 percent of pharmacy industry prescription revenues, up from 24 percent in 2013. 13 Fein AJ, The 2019 economic report on U.S. pharmacies and pharmacy benefit managers , Drug Channels Institute, 2019, drugchannelsinstitute.com. In response, both incumbents and non-traditional players are seeking opportunities to both capture a rapidly growing portion of the pharmacy value chain and deliver better experience to patients. Health systems, for instance, are increasingly entering the specialty space. Between 2015 and 2018 the share of provider-owned pharmacy locations with specialty pharmacy accreditation more than doubled, from 11 percent in 2015 to 27 percent in 2018, creating an opportunity to directly provide more integrated, holistic care to patients.

Challenges emerge for the US healthcare system as COVID-19 cases rise

A new wave of modalities of care and pharmaceutical innovation are being driven by cell and gene therapies. Global sales are forecasted to grow at more than 40 percent per annum from 2019 to 2024. 14 Evaluate Pharma, February 2020. These new therapies can be potentially curative and often serve patients with high unmet needs, but also pose challenges: 15 Capra E, Smith J, and Yang G, “ Gene therapy coming of age: Opportunities and challenges to getting ahead ,” October 2, 2019, McKinsey.com. upfront costs are high (often in the range of $500,000 to $2,000,000 per treatment), benefits are realized over time, and treatment is complex, with unique infrastructure and supply chain requirements. In response, both traditional healthcare players (payers, manufacturers) and policy makers (for example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) 16 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Medicaid program; establishing minimum standards in Medicaid state drug utilization review (DUR) and supporting value-based purchasing (VBP) for drugs covered in Medicaid, revising Medicaid drug rebate and third party liability (TPL) requirements,” Federal Register , June 19, 2020, Volume 85, Number 119, p. 37286, govinfo.gov. are considering innovative models that include value-based arrangements (outcomes-based pricing, annuity pricing, subscription pricing) to support flexibility around these new modalities.

Innovations also are accelerating in pharmaceutical distribution and delivery. Non-traditional players have entered the direct-to-consumer pharmacy space to improve efficiency and reimagine customer experience, including non-healthcare players such as Amazon (through its acquisition of PillPack in 2018) and, increasingly, traditional healthcare players as well, such as UnitedHealth Group (through its acquisition of DivvyDose in September 2020). COVID-19 has further accelerated innovation in patient experience and new models of drug delivery, with growth in tele-prescribing, 17 McKinsey COVID-19 Consumer Survey conducted June 8, 2020 and July 14, 2020. a continued shift toward delivery of pharmaceutical care at home, and the emergence of digital tools to help manage pharmaceutical care. Select providers have also begun to expand in-home offerings (for example, to include oncology treatments), shifting the care delivery paradigm toward home-first models.

A range of new models to better integrate pharmaceutical and medical care and management are emerging. Payers, particularly those with in-house pharmacy benefit managers, are using access to data on both the medical and pharmacy benefit to develop distinctive insights and better coordinate across pharmacy and medical care. Technology providers, together with a range of both traditional and non-traditional healthcare players, are working to integrate medical and pharmaceutical care in more convenient settings, such as the home, through access to real-time adherence monitoring and interventions. These players have an opportunity to access a broad range of comprehensive data, and advanced analytics can be leveraged to more effectively personalize and target care. Such an approach may necessitate cross-segment partnerships, acquisitions, and/or alliances to effectively integrate the many components required to deliver integrated, personalized, and higher-value care.

Creating and capturing new value

These materials are being provided on an accelerated basis in response to the COVID-19 crisis. These materials reflect general insight based on currently available information, which has not been independently verified and is inherently uncertain. Future results may differ materially from any statements of expectation, forecasts or projections. These materials are not a guarantee of results and cannot be relied upon. These materials do not constitute legal, medical, policy, or other regulated advice and do not contain all the information needed to determine a future course of action. Given the uncertainty surrounding COVID-19, these materials are provided “as is” solely for information purposes without any representation or warranty, and all liability is expressly disclaimed. References to specific products or organizations are solely for illustration and do not constitute any endorsement or recommendation. The recipient remains solely responsible for all decisions, use of these materials, and compliance with applicable laws, rules, regulations, and standards. Consider seeking advice of legal and other relevant certified/licensed experts prior to taking any specific steps.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, our research indicated that profits for healthcare organizations were expected to be harder to earn than they have been in the recent past, which has been made even more difficult by COVID-19. New entrants and incumbents who can reimagine their business models have a chance to find ways to innovate to improve healthcare and therefore earn superior returns. The opportunity for incumbents who can reimagine their business models and new entrants is substantial.

Institutions will be expected to do more than align with growth segments of healthcare. The ability to innovate at scale and with speed is expected to be a differentiator. Senior leaders can consider five important questions:

- How does my business model need to change to create value in the future healthcare world? What are my endowments that will allow me to succeed?

- How does my resource (for example, capital and talent) allocation approach need to change to ensure the future business model is resourced differentially compared with the legacy business?

- How do I need to rewire my organization to design it for speed? 18 De Smet A, Pacthod D, Relyea C, and Sternfels B, “ Ready, set, go: Reinventing the organization for speed in the post-COVID-19 era ,” June 26, 2020, McKinsey.com.

- How should I construct an innovation model that rapidly accesses the broader market for innovation and adapts it to my business model? What ecosystem of partners will I need? How does my acquisition, partnership, and alliances approach need to adapt to deliver this rapid innovation?

- How do I prepare my broader organization to adopt and scale new innovations? Are my operating processes and technology platforms able to move quickly in scaling innovations?

There is no question that the next few years in healthcare are expected to require innovation and fresh perspectives. Yet healthcare stakeholders have never hesitated to rise to the occasion in a quest to deliver innovative, quality care that benefits everyone. Rewiring organizations for speed and efficiency, adapting to an ecosystem model, and scaling innovations to deliver meaningful changes are only some of the ways that helping both healthcare players and patients is possible.

Emily Clark is an associate partner in the Stamford office. Shubham Singhal , a senior partner in McKinsey’s Detroit office, is the global leader of the Healthcare, Public Sector and Social Sector practices. Kyle Weber is a partner in the Chicago office.

The authors would like to thank Ismail Aijazuddin, Naman Bansal, Zachary Greenberg, Rob May, Neha Patel, and Alex Sozdatelev for their contributions to this article.

This article was edited by Elizabeth Newman, an executive editor in the Chicago office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

The great acceleration in healthcare: Six trends to heed

When will the COVID-19 pandemic end?

Healthcare innovation: Building on gains made through the crisis

Build plans, manage results, & achieve more

Learn about the AchieveIt Difference vs other similar tools

We're more than just a software, we're a true partner

- Strategic Planning

- Business Transformation

- Enterprise PMO

- Project + Program Management

- Operational Planning + Execution

- Integrated Plan Management

- Federal Government

- State + Local Government

- Banks + Credit Unions

- Manufacturing

Best practices on strategy, planning, & execution

Real-world examples of organizations that have trusted AchieveIt

Ready-to-use templates to take planning to the next level

Research-driven guides to help your strategy excel

Pre-recorded & upcoming webinars on everything strategy & planning

- *NEW!* Podcast 🎙️

The Complete Guide to Strategic Planning in Healthcare

RELATED TAGS:

supply chain

Healthcare institutions around the world must adapt their strategies to meet current trends and patient preferences. By using reliable and thoughtful planning, healthcare facilities can initiate patient-centric approaches and boost success.

Strategic healthcare planning consists of creating objectives, setting goals and then creating a plan for achievement. In other words, it’s the process of outlining goals and taking the necessary steps to achieve them. Most healthcare plans also consider government policies and technological advancements that could alter health goals and operations.

Read on to learn more about the importance of planning in healthcare.

In This Article

The Importance of Planning in Healthcare

- New Technologies

- Mass Adoption of Virtual Care

- Continued Management of Cybersecurity Risks

- Evolving Coding Requirements

- Population Health Management

The Benefits of Healthcare Strategic Planning

Questions to ask, partner with achieveit today.

Strategic planning is essential for a healthcare facility’s overall success. Planning allows organizations to adjust to the changing demands of the healthcare industry while supporting goal achievement.

You can also see the importance of strategic healthcare planning in other areas, including:

- Adapting to current trends: Having strong plans in place can help your facility adjust to current trends. By strategically thinking about the future of the field, you can avoid surprises later. For example, a significant change facing the healthcare industry is the rise of hybrid and remote work. Many facilities offer telehealth services or remote appointments for patients. With strategic management in healthcare, institutions can take note of these changes and adjust upcoming hiring policies and staff positions.

- Meeting patient needs: Strategic planning can also aid facilities in meeting patient needs. As technological advancements progress and the number of available providers grows, patients are seeking personalized and high-quality options. Facilities can examine patient demands and use these to craft their upcoming strategy in healthcare. In turn, they can create a patient-centric approach that improves the quality of care and sets them apart from competitors.

- Reduc ing supply chain disruption impacts: The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the supply chain for all industries, including healthcare. Without the proper tools and equipment, healthcare professionals cannot provide care for all patients. Your strategic plan could help you analyze current supply chain trends and alter ordering decisions in response. For instance, if you notice a specific type of equipment is consistently out of stock, you could order extra quantities for your facility.

- Meeting rising hospital numbers: After the COVID-19 pandemic, the healthcare industry experienced a sudden increase in hospitalizations . Strategic planning allows facilities to allocate necessary resources to meet these trends. They can also become more prepared for other potential health crises.

- Helping with public funding: Strong performance helps healthcare facilities receive more funding from public sources. Most donors use various quality metrics to determine how much funding institutions should gain each year. A strategic plan can boost your facility’s performance on many levels, from care quality to maintaining supplies.

Overall, strategic planning in hospitals and other facilities is essential for institutional success and responding to current trends in the healthcare industry.

Top 5 Strategic Challenges in Healthcare

From the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) influx of insured patients to the increased strain of COVID-19, healthcare facilities have been constantly adapting. Here are some examples of strategic planning in healthcare today.

1. New Technologies

In the medical field, new technologies seem to appear every day. From remote patient monitoring to robust patient portals, healthcare facilities must consider the evolution of the tools used during day-to-day care. These resources may impact workflows, budgets and the patient experience.

Many new technologies offer benefits like improved efficiency and positive experiences, but they can also create healthcare challenges in the form of new requirements for your IT team and staff training. Remaining flexible can help you accommodate these possibilities, stay ahead of the competition and improve care with modern capabilities.

2. Mass Adoption of Virtual Care

From a cost perspective, one shining light for healthcare systems is the rise of virtual care, commonly referred to as telemedicine. Using internet-enabled services, healthcare providers are able to consult with patients virtually and provide diagnoses, thereby saving time and resources associated with an in-person hospital consult.

As this technology continues to proliferate, and patients become more comfortable with interacting with their doctors over virtual systems, healthcare systems will be able to trim significant expenses across departments, helping to control costs. In creating their strategic plans, healthcare leaders should take a deep look at how they continue managing telemedicine technology to help aid in future cost savings.

3. Continued Management of Cybersecurity Risks

Data security has become a significant challenge across industries, but none more so than the healthcare industry. Due to the extensive nature of personal information inherent in healthcare records, insurance companies and healthcare systems should be cautious regarding the security of their patient records.

As regular security breaches always remind us, healthcare entities should pay special attention to the security of their systems to ensure the privacy of subscribers. Healthcare leadership will need to collaborate extensively with IT, in a strategic sense, to ensure the department has the resources and technology necessary to guarantee data security and HIPAA compliance.

4. Evolving Coding Requirements

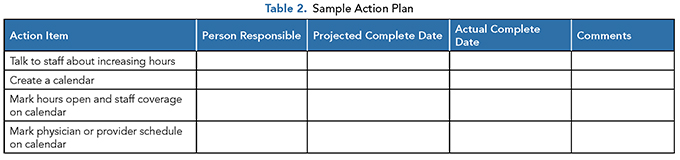

The next version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is currently under review in the U.S. If you’ve been in the industry for a while, you might remember the transition to ICD-10 back in 2015. Although we may not see ICD-11 for a while, healthcare strategy must consider this eventual implementation and other potential changes to reporting and documentation requirements. To ensure full reimbursement, organizations may need to upgrade existing systems and train employees accordingly.

5. Population Health Management

Healthcare systems across the country are being confronted with a new paradigm of healthcare delivery: Ensuring the overall health of demographic cohorts within their communities.

Shifts toward value-based care only increase the focus on population health, requiring healthcare leaders to design strategic plans and allocate resources to educate the populations they serve on preventative care. This will require the participation of stakeholders across departments and often will necessitate new programs to be established to help further population health interests.

Committing to a strategic plan can bring many benefits to healthcare facilities, including:

- Establishing a shared vision: A plan requires your facility to focus on specific goals. As you develop these objectives, you and your team can establish the overall purpose of your facility. Then, you can create concrete ways to meet this vision . You can also inform employees, shareholders and other crucial team members of this vision, inspiring members at every level. All members can unite around a shared purpose and find more value in their work, improving overall performance.

- Prioritizing critical issues: By focusing on a strategic plan, you can prioritize vital issues. Every healthcare facility has specific areas for improvement, whether it’s improving collaboration or meeting staffing requirements. Strategic management in healthcare allows you to identify these areas and brainstorm specific ways to address them. You can focus on resolving the most significant issues first, instead of getting overwhelmed with secondary problems.

- Improving team communication: Strategic planning also assists with communication across your facility. Your plan should address key issues and goals, then outline the steps you will take to achieve these. You can share these plans with all institutional members, giving everyone a clear idea of future actions. With everyone on the same page, your facility can collaborate more easily and stay on track with goals.

- Enhancing motivation: A clear vision and plan can motivate employees to work harder. They can feel empowered to make decisions that support institutional goals. As they work toward a shared purpose outlined in a healthcare strategy, they feel more motivated by their daily work and can improve their performance.

- Solidifying leadership: All healthcare facilities rely on strong leadership to lead employees and meet goals. Leaders can use strategic plans to clearly identify goals for employees. They can clarify expected behaviors and encourage employees to work toward their personal best. Passionate leaders and hard-working employees can establish your facility as a leading healthcare option.

Because the purpose of strategic planning in healthcare is to work towards improvement, asking questions can help you. Healthcare institutions should ask a few crucial questions during their planning. By thinking about particular circumstances, you can tailor plans for your needs. These questions can also help you identify goals and develop a shared purpose.

Here are a few examples of questions to ask during strategic planning:

- What is the current financial situation of your institution?

- What are your goals for finances moving forward?

- What areas need more help or growth?

- What are the needs of your facility’s typical population?

- How could these needs change over time?

- What current trends in the healthcare industry or government policies could impede these goals?

- Where would you like to see your organization in five years or ten years?

You can use questions like these to establish objectives and an overall vision. Once you have developed these, you can develop steps for achievement. Structures like SMART goals can help you create measurable and timely actions .

At AchieveIt, we understand the importance of well-defined healthcare goals and addressing the challenges of healthcare strategy. You can move directly toward your shared vision with a strategic plan and clear-cut goals.

Our strategic planning software helps healthcare institutions meet their goals. The technology helps you analyze data to identify specific goals and areas for improvement. Then, we can help you form quantifiable and actionable goals that move you toward your overall purpose.

AchieveIt software also features:

- Integrated reports

- Automated reminders for deadlines and goals

- Real-time data updates

- Speedy set-ups and communication processes

Our expert team of specialists can help your facility through each step of the planning process. We can enhance your plans and offer specific suggestions for improvement. Whether you want to improve physician care or reduce waiting room times, our software can help you meet these goals.

Let’s actually do this. Schedule a demo with AchieveIt today.

Meet the Author Chelsea Damon

Chelsea Damon is the Content Strategist at AchieveIt. When she's not publishing content about strategy execution, you'll likely find her outside or baking bread.

Related Posts

Balanced Strategy: Mastering the Art of Zooming In and Out

Everything You Need to Know About Business Mission and Vision Statements

Excel vs. AchieveIt for Strategic Planning

Hear directly from our awesome customers

See first-hand why the world's best leaders use AchieveIt

See AchieveIt in action

Stay in the know. Join our community of subscribers.

Subscribe for plan execution content sent directly to your inbox.

5 Tips For Strategic Planning Professionals in Healthcare

Enhance your strategic planning with our 5 tips for healthcare professionals. Elevate your planning and contribute to your organization's success now!

Table of Contents

In healthcare, things change quickly. Some hospitals and healthcare organizations believe that’s a reason to avoid strategic planning—because the change lurking just around the bend is sure to derail even the best-laid plans. But the truth is, a strategy can be your best resource in times of change, as long as it’s grounded in your mission and vision.

As a leading strategy management software provider, we’ve helped numerous healthcare organizations plan and execute their goals for the future. Keep reading to get our take on why strategic management in healthcare is critical for succeeding in a volatile world, and learn a few tips that can help you carry out strategic planning more effectively.

Looking for some examples of healthcare strategic plans? Download sample strategy maps created specifically for medical and healthcare organizations like yours.

Strategic management in healthcare: what is it.

Strategic management in healthcare is the process of defining the future of your organization, setting goals that will move you toward that future, and determining the major projects you’ll take on to meet those goals. It also includes sustaining that strategy focus over a period of three to five years.

Why is strategic management important in healthcare?

Like other companies, healthcare organizations benefit from having a plan for the future—one that all employees are aware of and consistently working toward. Strategy should serve as a guidepost for all important decisions to make sure your facility stays on track.

But as we mentioned above, healthcare is even more complex than your average business—and frequently affected by external forces. If asked to describe how strategic management helps your facility control the future, we’d answer with the following:

- The strategic planning process naturally includes assessing changes in the external environment (through exercises like the SWOT analysis) and thus helps your organization stay on top of them.

- It provides focus and direction for daily work even as circumstances (internal or external) may change.

- It provides leaders with a consistent flow of information about organizational performance, promoting better, more timely decision-making. The availability of such data also helps organizations reprioritize or pivot as needed.

5 Tips For Healthcare Strategic Planning Professionals

1. keep your organization’s mission top-of-mind..

Mission and vision are the cornerstones of your organization and provide a foundation for strategic planning. Make sure the priorities and objectives outlined in your plan support those key elements—and reconsider any goals that are not aligned.

2. Narrow your strategy’s focus.

Too many healthcare organizations try to be everything to everyone. As a result, their strategies touch nearly every base imaginable, from being the best at research and innovation to serving as many potential patients as possible to being customer-centric, etc. Narrowing down your strategy requires courage—it may feel as if you’re passing up opportunities to improve. But in reality, you run the risk of not excelling in anything if you’re trying to achieve everything . Home in on the areas you want to pursue and direct your resources and energy to accomplishing those specific goals.

3. Align your plan with in-progress accreditations or certifications.

If you’re pursuing an accreditation or award like PHAB or Baldrige, your strategic plan needs to align with that goal. Make sure your plan points you in the right direction and supports tracking all the data required by the administering body.

4. Do a SWOT analysis.

Periodically analyzing your organization’s strengths and weaknesses, as well as external opportunities and threats, is a useful exercise that can inform your strategic plan. Follow the steps outlined here to complete the analysis, and see some healthcare-specific examples.

5. Communicate.

Strategic plans are only effective if everyone knows about them. Every department head should be charged with explaining how their team fits into the strategy and why it matters. (Read some tips here on how to effectively communicate with employees.) You’ll also need to create tailored presentations for other stakeholders—patients, administrators, community members, etc.

And finally, remember: Don’t overload yourself and your team with goals and metrics right out of the gate—having too many makes it hard to prioritize and makes communication difficult. Ease into it. The first year, start by creating a high-level plan for the organization as a whole; the following year, try to tackle planning for business units, service lines, etc.

Support Your Efforts With ClearPoint Strategy Reporting Software

Understanding why strategic planning is important in healthcare is the first step; however, the strategic planning process is complex.

In fact, creating the strategy is just the tip of the iceberg. Once it’s been launched, you need to know if you’re making progress—and that requires reporting regularly on your results.

Reporting can sink even the best strategy efforts because, without the right tools, strategy management quickly becomes overwhelming. ClearPoint is the only strategy reporting software that helps healthcare organizations effectively manage all the fundamental activities that go into reporting:

- You need to gather data that will help you draw conclusions about your performance. Your data is likely scattered across locations, systems, and services. ClearPoint seamlessly integrates with your on-premise and SaaS software applications to make data collection easy.

- You need to pull together data in a way that helps you make sense of it. In ClearPoint, you can make sense of any data set. Use data aggregations and complex calculations to get your data in any format you need. Then, automatically evaluate your results so it’s easy to tell if you’re on track.

- You need to analyze data to understand the story it is telling. ClearPoint allows you to link projects with strategy objectives to understand how everything you’re doing fits together; it also facilitates the analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data. This allows your organization to spot problems early and make corrections to areas that need the most help.

- You need to create reports that your leadership teams can review and discuss for decision-making purposes. With ClearPoint, you can create beautifully branded reports (and dashboards like the one below) for any audience—your board, your management team, and your individual providers. ClearPoint lets you create reports in a variety of formats and even schedule reports to automatically generate and send.

When it comes down to it, the fundamental challenge of strategic management in healthcare is managing it all—coordinating resources and people to ensure everyone is continuously working toward a common goal, and staying on top of your successes and failures.

How can strategic planning improve the performance of an organization?

Strategic planning improves the performance of an organization by providing a clear direction and framework for decision-making. It aligns resources and efforts with long-term objectives, identifies potential risks and opportunities, and ensures that all departments are working towards common goals. This results in increased efficiency, better resource allocation, and improved overall performance.

Why is strategic planning important in healthcare?

Strategic planning in healthcare is important because it helps organizations navigate the complex and rapidly changing healthcare environment. It ensures that resources are used effectively to improve patient care, meet regulatory requirements, and achieve financial stability. Strategic planning also helps healthcare organizations set priorities, allocate resources, and measure progress towards their goals, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes and organizational sustainability.

Why do strategic plans fail?

Strategic plans fail for several reasons:

- Lack of Clear Objectives: Vague or unrealistic goals can lead to confusion and lack of focus. - Poor Communication: Failure to communicate the plan to all stakeholders can result in lack of alignment and commitment. - Inadequate Resources: Insufficient resources, including time, budget, and personnel, can hinder implementation. - Lack of Flexibility: Inability to adapt the plan to changing circumstances can make it obsolete. - Poor Execution: Failure to translate the plan into actionable steps and monitor progress can lead to poor outcomes.

How is strategic planning done?

Strategic planning is done through a systematic process that includes:

- Defining Vision and Mission: Establishing the organization's purpose and long-term aspirations. - Conducting Analysis: Performing SWOT or PESTEL analyses to understand internal and external factors . - Setting Goals: Defining specific, measurable objectives. - Developing Strategies: Creating broad approaches and initiatives to achieve the goals. - Allocating Resources: Ensuring necessary resources are available and properly allocated. - Implementing Plans: Executing the strategies and action plans. - Monitoring and Evaluating: Continuously tracking progress and making adjustments as needed.

Who does strategic planning?

Strategic planning is typically done by senior leadership and management teams within an organization. This often includes executives, department heads, and key stakeholders. In larger organizations, strategic planning may also involve input from board members, employees, and external consultants to ensure a comprehensive and inclusive approach.

Ted Jackson

Ted is a Founder and Managing Partner of ClearPoint Strategy and leads the sales and marketing teams.

Latest posts

ClearPoint Strategy versus the Status Quo

.webp)

ClearPoint Strategy vs. Envisio: A Comprehensive Comparison

%20(2).webp)

ClearPoint Strategy vs. AchieveIt: Selecting the Optimal Tool for Strategic Management

Strategic Planning In Healthcare: 2024 Guide + Examples

Sara Seirawan

This guide contains new healthcare planning strategies, their benefits, examples, traps to avoid, and all you need to know.

Whether you’re a medical business owner, an executive, or a practitioner, my promise to you is that, by the end of this article, you’ll get a razor-sharp understanding of what strategic planning is and how it can skyrocket your operational efficiency.

Here’s a brief outline of what I’ll cover:

What is strategic planning in healthcare?

- The importance of strategic planning in healthcare

- 3 Common Mistakes when implementing strategies

- The best 8 healthcare planning strategies

- ‘Secret’ to a fruitful healthcare planning campaigns

Strategic planning in healthcare is setting long-term objectives for your medical business and an action plan to hit your target goals. It’s about taking a proactive approach to building a future-proof medical brand.

There are many strategies (which we’re going to look at) to achieve a strategy-driven business model, but before we go deep into the details, let’s check how this can benefit your practice.

The benefit of strategic planning in healthcare

With a good strategic approach comes great advantages for your medical business.

1) It protect your medical business from unforeseen risks

With the Covid-19 situation, healthcare providers no longer can afford to function reactively. And this is where SP (strategic planning) comes into place. SP, by nature, is a proactive approach. It is focused on long-term goals and future-oriented planning.

This not only immune you against any unlooked-for risks but arms you with a well-crafted plan of what should be done in the face of uncertainty.

The Planning Strategy should work as the shatterproof window for your practice.

2) It speeds up your medical business growth

Having a strategy in place holds everyone involved accountable. This means an increased commitment from your team and faster work processes.

Furthermore, according to Parkinson’s Law, any team, when giving a task, will fill whatever time was allocated for its completion. This not only quickens your operational efficiency, but it also skyrockets your work productivity and patient outcomes.

This enhanced workflow will accelerate the rate at which your medical business grows. Resulting in a faster profit cycle.

The next graph illustrates how business growth rate correlates with operational efficiency.

3) It creates a cohesive workplace for your medical business

Medical businesses routinely separate functions to hierarchical levels to achieve efficiencies, However…

These divides lead to confusion, anxiety, and distrust as employees work at cross-purposes, taking refuge in functional silos instead of a collaborative ecosystem.

This makes your medical staff sub-optimizing when you need all parts working together.

Employees go about directionless, without an understanding of their role in delivering the (non-existent) consistent experience for patients.

To combat this, putting a strategic vision for your business ensures cohesiveness and a united workforce.

The bottom line is : the result of having a shared strategic vision is coherence; the result of aimless workflow is wasted resources.

4) It increases your profit margin

Great medical business owners aim for the stars and land on the moon. And this is what makes strategic financial planning great. It forces you to aim high. This kind of planning breaks the chains of the self-limiting beliefs that are preventing you and your staff from achieving a higher rate of profit margins.

Not only that, but it also makes sure that what you’re doing is directed by a strategy and measurable KPIs (key performance indicators) and not by a mere accumulation of tactics that don’t add up together.

This results in a well-tracked process, efficient way of working, and increased profitability.

3 Common mistakes when implementing healthcare strategic planning

Let’s explore common mistakes medical business fall into when implementing strategic planning workshops.

1) Disregarding their branding efforts

Any medical practice can have strategies, but great medical businesses let their brand act as a decisional filter for their planning effort.

Does your strategy align perfectly with your brand’s core attribute? Does this plan solidify your place in the market or does it weaken your brand’s perceived value? If you don’t have a grounded brand in place, your strategy might end up hurting your medical business.

If you’d like to learn more about brand building and how can you build a mouth-watering brand, you can check our free healthcare branding guide .

2) Focusing on too many metrics and KPIs

Getting distracted by too many metrics is the fast lane to a crumbling healthcare plan. Many practices try to implement a strategy but end up focusing on the wrong metrics and getting overwhelmed.

It is best to list out critical KPIs (key performance indicators) for your medical brand before embarking on a strategy.

3) Lack of professional facilitators

Any healthcare strategic plan needs a good facilitator. A facilitator that has a great knowledge of the healthcare industry know-how and its business side of things. Common trap healthcare organizations or practices fall into is trying to implement these strategies in-house. This leads to unproductive workshops and unfruitful results.

We strongly advise you to outsource these strategies to great facilitators that have past-experience running healthcare strategic planning workshops. This will save you time and provide you with the best result for your medical business.

Best Healthcare Planning Strategies (With Examples)

Let’s go through some of the essentials of strategic planning methods in healthcare.

1) S.W.O.T Analysis Strategy

S.W.O.T is a strategic planning technique used to define your healthcare organization’s (or practice’s) Strengths , Weaknesses , Opportunities , and Threats in the competitive landscape.

SWOT Analysis arms you with a clear overview of critical metrics that are key for your performance and the overall success of your medical business.

Let’s see some examples of SWOT Diagrams in healthcare.

Hospital strategic plan: SWOT example

Strategic planning in nursing: swot example, 2) s.w.o.t strategy canvas™.

SWOT Analysis is not enough to measure the success of your efforts.