United States Foreign Policy Analytical Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

United states foreign policy, usa foreign policy during (1815-1941), usa foreign policy during (1941-1989), usa foreign policy during (1989-present), works cited.

Several countries today have established legal frameworks that determine how they relate with other nations. The United States of America has a comprehensive foreign policy which governs its relationship with other countries. “Since independence, the economy of U.S. has been flourishing and it is today one of the most developed countries in the world” (Hastedt 65).

This has given it a dominant position in the world political arena and it has also influenced how it deals with other nations. “The diplomatic affairs of this country are always under the guidance of the secretary of the State” (Carter 82). However, final decisions on diplomatic affairs are only made by the president.

America’s foreign policy has always been shaped in such away that it favors its interests. It protects its corporations and other commercial organizations from any unfair treatment and competition (Kaufman 15). This has always been done to ensure that no country challenge its economic position.

U.S. has been using its power to suppress other nations that may be thinking of emerging as its competitor. For example it checked the influence of U.S.S.R. In order to continue dominating many countries, the U.S. government keeps on extending its authority and power over many nations.

“It has achieved this by simply influencing the social-economic and political institutions of some countries which are vulnerable to political influences” (Carter 130). Such practices are prevalent in countries which are poor and can not sustain themselves economically.

”Peace, prosperity, power, and principle,” have always acted as the guiding principles of U.S. foreign policy, and its interests revolve around them (Hastedt 29). The U.S. government has been striving to maintain these values, but the only thing that has been changing is the prevailing conditions which influence the manner they are achieved (Hastedt 30). We can therefore examine the foreign policies of U.S in the following phases.

America came up with the policy of “isolation” after the end of its revolutionary war. According to this policy, US did not engage in conflict resolution programs and it always remained impartial whenever some European countries had a conflict with each other (Carter 101). For example, this was demonstrated during the First World War and it continued until the beginning of the Second World War. The main interest of US during the 19 th century was to develop its economy and this influenced how it conducted its diplomatic activities with other nations.

It forged trade ties with other countries which were ready to do business with it. In addition to these, it also engaged in building its territory through bringing more territories under its control. For example in 1819 it managed to conquer Florida; in 1845 it brought Texas under its control and the Russian Empire agreed to sell Alaska to US in 1867.

Imperialism was also partially practiced by U.S. “Foreign policy themes were expressed considerably in George Washington’s farewell address; these included among other things, observing good faith and justice towards all nations and cultivating peace and harmony with all countries” (Carter 74). The US government in many cases declined to engage in signing treaties. For example it refused to be part of the “League of Nations” (Kaufman 67).

There was a remarkable increase in U.S. engagement in peace initiatives during the post World War One, and this formed its key agenda in foreign relations. President Wilson came up with guidelines that were used in ending the First World War. The European powers had a meeting in Paris in 1919 in which they discussed the ways of solving the disputes which had previously led to war among them. “The Versailles Treaty was signed by the countries that attended the conference but U.S. government did not” (Hastedt 120).

This is because the US government felt that some of the members had contradicted some of steps which governed the treaty. U.S. also managed to carry out the disarmament program successfully in 1920s and it also helped Germany to reconstruct its economy which had been ruined by over engagement in war. U.S. tried to continue pursuing the policy of “isolation” during 1930s.

However, President Roosevelt joined the Allied powers during the Second World War and they managed to win it. Japan was forcefully removed from China by U.S. and they also stopped its possible invasion of the Soviet Union. “Japan was greatly humiliated and it reacted by an attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, and the United States was at war with Japan, Germany, and Italy” (Carter 190).

The economy of U.S greatly improved after the second war, while the other European countries grappled with economic challenges. It was now one of the greatest countries and its power and influence was felt in many countries.

The emergence of the cold war in the post war period led to the split of the world into two spheres. These two spheres were dominated by Soviet Union and U.S. Non Aligned Movement was developed as a result of this process. The Cold War period only came to an end towards the end of the 20 th century. “A policy of containment was adopted to limit Soviet expansion and a series of proxy wars were fought with mixed results” (Kaufman 117).

The Soviet Union completely collapsed after the U.S. war against Iraq (Gulf War). America joined this war in order to dislodge Iraq from Kuwait so that peace and stability could be restored in that country. After the war, U.S. shifted its policy from Iraq because it was trying to be a threat to its interests in the region of Middle East (Carter 195).

America is still having an important role in world politics. Nonetheless, it is facing much opposition and competition from other countries like China. Its dominant role and influence has gone down and many countries from Africa are currently shifting their diplomatic relationships to the East. “U.S. foreign policy is characterized still by a commitment to free trade, protection of its national interests, and a concern for human rights”. A group of political scientists contend that the super powers seem to be having similar socio economic and political interests, and if they can find a good opportunity to pursue them together then we shall have a prosperous future.

Carter, Ralph. Contemporary cases in U.S. foreign policy: from terrorism to trade. Washington D.C: Press College, 2010.

Hastedt, Glenn. American foreign policy. New York: Longman, 2010.

Kaufman, Joyce. A concise history of U.S. foreign policy. New York: Rowman and Littlefield , 2009.

- How Long Does It Take to Have a Peace Process?

- Least Developed Countries

- US Foreign Policy in the Balkans

- The War in Iraq and the U.S. Invasion

- Syrian Crisis and Diplomatic Policies

- Current Conflicts in Sudan

- Do the Benefits of Globalization Outweigh the Costs?

- Global Conflict Likelihood

- Afghanistan: The Way to Go

- International Search and Rescue Efforts

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, May 24). United States Foreign Policy. https://ivypanda.com/essays/united-states-foreign-policy/

"United States Foreign Policy." IvyPanda , 24 May 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/united-states-foreign-policy/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'United States Foreign Policy'. 24 May.

IvyPanda . 2018. "United States Foreign Policy." May 24, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/united-states-foreign-policy/.

1. IvyPanda . "United States Foreign Policy." May 24, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/united-states-foreign-policy/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "United States Foreign Policy." May 24, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/united-states-foreign-policy/.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- How did Elizabeth I come to be queen of England?

- What were the biggest issues facing England during Queen Elizabeth I’s reign?

- What was Queen Elizabeth I’s relationship to religion in England?

- What was Queen Elizabeth I’s personal life like?

- Was Elizabeth I a popular queen?

foreign policy

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Academia - Foreign Policy: 16 Elements of Foreign Policy

- Social Sci LibreTexts - Foreign Policy

- UShistory.org - Foreign Policy: What Now?

foreign policy , general objectives that guide the activities and relationships of one state in its interactions with other states. The development of foreign policy is influenced by domestic considerations, the policies or behaviour of other states, or plans to advance specific geopolitical designs. Leopold von Ranke emphasized the primacy of geography and external threats in shaping foreign policy, but later writers emphasized domestic factors. Diplomacy is the tool of foreign policy, and war, alliances, and international trade may all be manifestations of it.

What is foreign policy?

Foreign policy is the mechanism national governments use to guide their diplomatic interactions and relationships with other countries. A state’s foreign policy reflects its values and goals, and helps drive its political and economic aims in the global arena. Many foreign policies also have a strong focus on national and international security, and will help determine how a country interacts with international organisations, such as the United Nations, and citizens of other countries.

Foreign policies are developed and influenced by a number of factors. These include:

- the country’s circumstances in a number of areas, including geographically, financially, politically, and so on

- the behaviour and foreign policies of other countries

- the state of international order and affairs more widely (for example, is there war or unrest? Are there trade alliances to take into consideration?)

- plans for advancement, such as economic advancement or technological advancement

Guided by foreign policy, diplomats and diplomatic bodies can work across borders to tackle shared challenges, promote stability, and protect shared interests.

A nation’s foreign policy typically works in tandem with its domestic policy, which is another form of public policy that focuses on matters at home. Together, the two policies complement one another and work to strengthen the country’s position both within and outside its borders.

Examples of foreign policy

The united kingdom.

Foreign policy in the United Kingdom is overseen by Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office , which is led by the Foreign Secretary.

Recent priorities for the UK’s foreign office have included imposing sanctions on Russia due to its ongoing conflict with Ukraine, and introducing a new Northern Ireland Protocol Bill. The UK has also continued its ongoing action against the regime in Syria.

Following the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union (EU) – made official in 2020 – UK policymakers have been focused on negotiating new trade agreements with international partners.

The United States

American foreign policy is overseen by the U.S. Department of State , which says its mission is to “protect and promote U.S. security, prosperity, and democratic values, and shape an international environment in which all Americans can thrive.”

Domestic bills and legislation connected to foreign policy are managed by the United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs , a standing committee of the U.S. House of Representatives that has jurisdiction over matters such as foreign assistance, HIV/AIDS in foreign countries, and the promotion of democracy. It also has six standing subcommittees that oversee issues connected to human rights practices, disaster assistance, international development, and so on in different regions of the world, such as Asia or the Middle East.

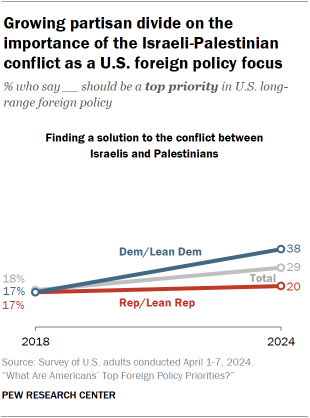

Recent events in American international affairs have included ending its war in Afghanistan, and affirming its support for a two-state solution to the ongoing conflict between Palestine and Israel.

Chinese foreign policy consists of the following elements:

- Maintaining independence and state sovereignty.

- Maintaining world peace.

- Friendly relations.

- Enhanced unity and cooperation between developing countries.

- Increasing its opening and modernisation efforts.

China’s foreign policy also stipulates that China not engage in diplomatic relationships with any country that formally recognises Taiwan, which China does not recognise as a separate nation.

Nigeria’s foreign policy is lauded for strengthening its position and power regionally and internationally. Its objectives are enshrined in its constitution, and include:

- the promotion and protection of the national interest

- the promotion of African integration and support for African unity

- the promotion of international co-operation for the consolidation of universal peace and mutual respect among all nations, and the elimination of discrimination in all manifestations

- respect for international law and treaty obligations, as well as seeking settlement to international disputes by negotiation, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, and adjudication

- the promotion of a just world economic order

What is the difference between foreign policy and international relations?

International relations is a discipline of political science and can be considered one of the social sciences – it’s an area of academic study that examines the interactions between countries. Foreign policy, on the other hand, is a working template that guides how one country interacts with others.

Foreign policy in practice: impacts and consequences

How does foreign policy influence international politics.

Because foreign policies are developed to protect a nation’s interests and influence its dealings with other nations on the world stage, they have a direct impact on world politics. But it’s also fair to say that international affairs help shape foreign policies, too.

There are also a number of international organisations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that directly impact international relations and foreign policies, such as:

- The United Nations

- NATO (The North Atlantic Treaty Organization)

- The European Union

How does foreign policy affect the global economy?

Foreign policies can have a huge impact on the economy, both at home and abroad. While this is partially because policies often focus on the economic advancement of their nations, it’s also because almost all aspects of any foreign policy will have a knock-on effect on the wider global financial system.

For example, Foreign Policy magazine reported earlier this year that the war in Ukraine that was triggered by Russian President Vladimir Putin has already changed the world’s economy. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU has had an ongoing financial impact and consequences for trade relationships throughout Europe (and even farther afield), while the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown measures taken in various countries has had a lasting effect on global supply chains and finances.

Help set public policy agendas

Explore public policy – including foreign policy and international studies – in greater depth with the 100% online Master of Public Administration (MPA) at the University of York.

One of the core modules on this flexible, part-time master’s degree is in policy analysis, so you will explore and analyse the complexity inherent in contemporary social and public policy development and reform. You will critically examine the role of ideas, interests, institutions, and actors in the policy process, and explore the wider social, economic, and political processes that shape contemporary policy-making. You will also gain conceptual and analytical tools to undertake advanced applied policy analysis in a range of local, national, and international policy settings.

Additionally, this postgraduate degree includes a module in policy research, enabling you to critically reflect on the strengths, limitations, and appropriateness of different research approaches and techniques, and helping you to acquire the skills needed to evaluate and commission research for public policy and administration contexts.

For further information about entry requirements, tuition fees, application deadlines, and independent research, please visit the programme page .

Start application

Admission requirements

Start dates

Tuition and course fees

Accessibility Statement

Online programmes

Other programmes at York

University of York

York YO10 5DD United Kingdom

Freephone: 0808 501 5166 Local: +44 (0) 1904 221 232 Email: [email protected]

© University of York Legal statements | Privacy and cookies

What Is Foreign Policy And Why Is It Important?

Understanding the definition of foreign policy further, a look into the purpose and importance of foreign policy, 1. defense and security, 2. economic interest.

Several countries have also formed intergovernmental organizations and multi-state entities to promote their respective economic interest. Examples include the European Union , the World Trade Organization, and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries .

3. Internationalist Pursuit

Acknowledging the modern role of foreign policy.

The three purposes contradict one another at times. There are situations in which national security and economic interest do not go with the security and economic needs of others. Hence, it is important to look at foreign policy not as a tool for promoting international cooperation but as a way of defining the role of a country as an international actor.

What Is Foreign Policy? Definition and Examples

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- The U. S. Government

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.A., International Relations, Brown University

A state’s foreign policy consists of the strategies it uses to protect its international and domestic interests and determines the way it interacts with other state and non-state actors. The primary purpose of foreign policy is to defend a nation’s national interests, which can be in nonviolent or violent ways.

Key Takeaways: Foreign Policy

- Foreign policy encompasses the tactics and process by which a nation interacts with other nations in order to further its own interests

- Foreign policy may make use of diplomacy or other more direct means such as aggression rooted in military power

- International bodies such as the United Nations and its predecessor, the League of Nations, help smooth relations between countries via diplomatic means

- Major foreign policy theories are Realism, Liberalism, Economic Structuralism, Psychological Theory, and Constructivism

Examples of Foreign Policy

In 2013 China developed a foreign policy known as the Belt and Road Initiative, the nation’s strategy to develop stronger economic ties in Africa, Europe, and North America. In the United States, many presidents are known for their landmark foreign policy decisions such as the Monroe Doctrine which opposed the imperialist takeover of an independent state. A foreign policy can also be the decision to not participate in international organizations and conversations, such as the more isolationist policies of North Korea .

Diplomacy and Foreign Policy

When foreign policy relies on diplomacy, heads of state negotiate and collaborate with other world leaders to prevent conflict. Usually, diplomats are sent to represent a nation’s foreign policy interests at international events. While an emphasis on diplomacy is a cornerstone of many states' foreign policy, there are others that rely on military pressure or other less diplomatic means.

Diplomacy has played a crucial role in the de-escalation of international crises, and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 is a prime example of this. During the Cold War , intelligence informed President John F. Kennedy that the Soviet Union was sending weapons to Cuba, possibly preparing for a strike against the United States. President Kennedy was forced to choose between a foreign policy solution that was purely diplomatic, speaking to the Soviet Union President Nikita Khrushchev or one that was more militaristic. The former president decided to enact a blockade around Cuba and threaten further military action if Soviet ships carrying missiles attempted to break through.

In order to prevent further escalation, Khrushchev agreed to remove all missiles from Cuba, and in return, Kennedy agreed not to invade Cuba and to remove U.S. missiles from Turkey (which was within striking distance of the Soviet Union). This moment in time is significant because the two governments negotiated a solution that ended the current conflict, the blockade, as well as de-escalated the larger tension, the missiles near each other’s borders.

The History of Foreign Policy and Diplomatic Organizations

Foreign policy has existed as long as people have organized themselves into varying factions. However, the study of foreign policy and the creation of international organizations to promote diplomacy is fairly recent.

One of the first established international bodies for discussing foreign policy was the Concert of Europe in 1814 after the Napoleonic wars . This gave the major European powers (Austria, France, Great Britain, Prussia, and Russia) a forum to solve issues diplomatically instead of resorting to military threats or wars.

In the 20th Century, World War I and II once again exposed the need for an international forum to de-escalate conflict and keep the peace. The League of Nations (which was formed by former U.S. President Woodrow Wilson but ultimately did not include the U.S.) was created in 1920 with the primary purpose of maintaining world peace. After the League of Nations dissolved, it was replaced by the United Nations in 1954 after World War II, an organization to promote international cooperation and now includes 193 countries as members.

It is important to note that many of these organizations are concentrated around Europe and the Western Hemisphere as a whole. Because of European countries’ history of imperialism and colonization, they often wielded the greatest international political and economic powers and subsequently created these global systems. However, there are continental diplomatic bodies such as the African Union, Asia Cooperation Dialogue, and Union of South American Countries which facilitate multilateral cooperation in their respective regions as well.

Foreign Policy Theories: Why States Act as They Do

The study of foreign policy reveals several theories as to why states act the way they do. The prevailing theories are Realism, Liberalism, Economic Structuralism, Psychological Theory, and Constructivism.

Realism states that interests are always determined in terms of power and states will always act according to their best interest. Classical Realism follows 16th-century political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli ’s famous quote from his foreign policy book "The Prince":

“It is much safer to be feared than loved.”

It follows that the world is full of chaos because humans are egoistic and will do anything to have power. The structural reading of realism, however, focuses more on the state than the individual: All governments will react to pressures in the same way because they are more concerned about national security than power.

The theory of liberalism emphasizes liberty and equality in all aspects and believes that the rights of the individual are superior to the needs of the state. It also follows that the chaos of the world can be pacified with international cooperation and global citizenship. Economically, liberalism values free trade above all and believes the state should rarely intervene in economic issues, as this is where problems arise. The market has a long-term trajectory towards stability, and nothing should interfere with that.

Economic Structuralism

Economic structuralism, or Marxism, was pioneered by Karl Marx, who believed that capitalism was immoral because it is the immoral exploitation of the many by the few. However, theorist Vladimir Lenin brought the analysis to an international level by explaining that imperialist capitalist nations succeed by dumping their excess products in economically weaker nations, which drives down the prices and further weakens the economy in those areas. Essentially, issues arise in international relations because of this concentration of capital, and change can only occur through the action of the proletariat.

Psychological Theories

Psychological theories explain international politics on a more individual level and seek to understand how an individual’s psychology can affect their foreign policy decisions. This follows that diplomacy is deeply affected by the individual ability to judge, which is often colored by how solutions are presented, the time available for the decision, and level of risk. This explains why political decision making is often inconsistent or may not follow a specific ideology.

Constructivism

Constructivism believes that ideas influence identities and drive interests. The current structures only exist because years of social practice have made it so. If a situation needs to be resolved or a system must be changed, social and ideological movements have the power to bring about reforms. A core example of constructivism is human rights, which are observed by some nations, but not others. Over the past few centuries, as social ideas and norms around human rights, gender, age, and racial equality have evolved, laws have changed to reflect these new societal norms.

- Elrod, Richard B. “The Concert of Europe: A Fresh Look at an International System.” World Politics , vol. 28, no. 2, 1976, pp. 159–174. JSTOR , JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2009888.

- “The Cuban Missile Crisis, October 1962.” U.S. Department of State , U.S. Department of State, history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/cuban-missile-crisis.

- Viotti, Paul R., and Mark V. Kauppi. International Relations Theory . 5th ed., Pearson, 2011.

Viotti, Paul R., and Mark V. Kauppi. International Relations Theory . Pearson Education, 2010.

- Who Were the Democratic Presidents of the United States?

- List of Current Communist Countries in the World

- The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962

- Why Did the U.S. Enter the Vietnam War?

- The Reagan Doctrine: To Wipe Out Communism

- The Good Neighbor Policy: History and Impact

- 8 of the Scariest Days in America

- What Is Socialism? Definition and Examples

- What Is Appeasement? Definition and Examples in Foreign Policy

- The History of Containment Policy

- What Was the Open Door Policy in China? Definition and Impact

- What Is Extradition? Definition and Considerations

- Best Political Science Schools in the U.S.

- Commonwealth of Nations

- What Makes a Ruler a Dictator? Definition and List of Dictators

- The "Deep State" Theory, Explained

- All Articles

- Books & Reviews

- Anthologies

- Audio Content

- Author Directory

- This Day in History

- War in Ukraine

- Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

- Artificial Intelligence

- Climate Change

- Biden Administration

- Geopolitics

- Benjamin Netanyahu

- Vladimir Putin

- Volodymyr Zelensky

- Nationalism

- Authoritarianism

- Propaganda & Disinformation

- West Africa

- North Korea

- Middle East

- United States

- View All Regions

Article Types

- Capsule Reviews

- Review Essays

- Ask the Experts

- Reading Lists

- Newsletters

- Customer Service

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Subscriber Resources

- Group Subscriptions

- Gift a Subscription

U.S. Foreign Policy

Explore Foreign Affairs ’ coverage of the evolution of Washington’s approach to foreign policy and the United States’ role in the world.

Top Stories

The credibility trap.

Is Reputation Worth Fighting For?

Keren Yarhi-Milo

The most dangerous game.

Do Power Transitions Always Lead to War?

Manjari Chatterjee Miller

Why they don’t fight.

The Surprising Endurance of the Democratic Peace

Michael Doyle

The fractured superpower.

Federalism Is Remaking U.S. Democracy and Foreign Policy

Jenna Bednar and Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar

The china trap.

U.S. Foreign Policy and the Perilous Logic of Zero-Sum Competition

Jessica Chen Weiss

All democracy is global.

Why America Can’t Shrink From the Fight for Freedom

Article contents

Foreign policy decision making: evolution, models, and methods.

- David Brulé David Brulé Department of Political Science, Purdue University

- and Alex Mintz Alex Mintz Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy, and Strategy, Institute for Policy and Strategy, IDC Herzliya

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.185

- Published in print: 01 March 2010

- Published online: 22 December 2017

Choices made by individuals, small groups, or coalitions representing nation-states result in policies or strategies with international outcomes. Foreign policy decision-making, an approach to international relations, is aimed at studying such decisions. The rational choice model is widely considered to be the paradigmatic approach to the study of international relations and foreign policy. The evolution of the decision-making approach to foreign policy analysis has been punctuated by challenges to rational choice from cognitive psychology and organizational theory. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, scholars began to ponder the deterrence puzzle as they sought to find solutions to the problem of credibility. During this period, cross-disciplinary research on organizational behavior began to specify a model of decision making that contrasted with the rational model. Among these models were the bounded rationality/cybernetic model, organizational politics model, bureaucratic politics model, prospect theory, and poliheuristic theory. Despite these and other advances, the gulf between the rational choice approaches and cognitive psychological approaches appears to have stymied progress in the field of foreign policy decision-making. Scholars working within the cognitivist school should develop theories of decision making that incorporate many of the cognitive conceptual inputs in a logical and coherent framework. They should also pursue a multi-method approach to theory testing using experimental, statistical, and case study methods.

- international relations

- rational choice model

- foreign policy

- deterrence puzzle

- bounded rationality

- bureaucratic politics

- prospect theory

- poliheuristic theory

- foreign policy decision-making

- cognitive psychology

Introduction

Policies or strategies resulting in international outcomes are the products of choices made by individuals, small groups, or coalitions representing nation-states. One approach to international relations – the foreign policy decision-making approach – is aimed at studying such decisions. The focus on decision making can be characterized as micro-theory. It has two defining features: (1) an emphasis on the decision-making process rather than simply outcomes, and (2) the focus on attributes of individual decision-makers. As such, foreign policy decision making concerns human agency, which may entail no more than the incentives and constraints facing individual decision-makers. However, much of the research examines the perceptions, biases, beliefs, and decision rules of decision-makers.

The Evolution of Research on Foreign Policy Decision Making

Since its inception, foreign policy decision making has been inherently interdisciplinary and the development of the subfield follows a series of debates. Insights from economics, psychology, and organizational studies have influenced theory development in foreign policy decision-making research. The evolution of the decision-making approach to foreign policy analysis has been punctuated by challenges to rational choice from cognitive psychology and organizational theory. These debates have typically centered on the extent to which rationalist and non-rationalist approaches emphasize the explanation or prediction of outcomes of decisions (i.e., outcome validity) or the explanation of the process by which decisions are made (i.e., process validity). This essay illustrates the evolution of the foreign policy decision-making approach and offers some suggestions for future research.

Origins of Foreign Policy Decision Making

The rational choice model is frequently identified as the paradigmatic approach to the study of international relations and foreign policy. Rooted in economics (e.g., von Neumann and Morgenstern 1944 ; Friedman 1953 ), rational choice conceives of decisions as means–ends calculations (Zagare 1990 ; Morrow 1997 ). Decision-makers choose among a variety of options on the basis of their expectation that the choice selected will serve some goal better than the alternatives. This is frequently framed in terms of a simple cost–benefit analysis; decision-makers are expected to select the choice which has greater expected net benefits (i.e., benefits minus the costs) than those of other alternatives under consideration. However, many rational theories may simply posit a preference ordering over outcomes (see Morrow 1997 ). For example, if alternative X is expected to yield A and A is preferred to B , a decision-maker should prefer alternative X to an alternative that is expected to yield B . The primary claim of rational choice is that choices are consistent with preferences.

Early Cold War scholars tended to assume a rational choice framework. For example, work on deterrence by Brodie ( 1946 ) and others considered the implications of US national security policy given the recent advent of nuclear weapons from a rational perspective. According to this “first wave” deterrence school (see Jervis 1979 ), the problem posed by the possession of nuclear weapons was that the traditional logic of threats and coercive statecraft appeared no longer to apply. Given that the state to be coerced – the USSR – also possessed nuclear weapons, the cost of using nuclear weapons for the USA was nuclear retaliation. Thus, the use of nuclear weapons as a means to an end – in this case, deterrence or containment of the Soviet Union – promised negative net benefits. Assuming rationality meant that threats to use nuclear weapons were not to be viewed credibly, but only as bluffing behavior.

Rational choice cross-fertilized political science (Arrow 1951 ; Downs 1957 ) during the 1950s, including international relations (e.g., Kaplan 1957 ). Moreover, a “rational policy approach” was a well-known ideal in policy circles (Thompson 1955 ). Nonetheless, many IR scholars were quick to point out the apparent inconsistencies with their understanding of rationality and the manner in which decisions are undertaken. Just as realists would later be charged with “black-boxing” the state, rational choice approaches were thought to “black-box” decision-makers. As Verba ( 1961 :106) argues about rational decision-makers, “All other behaviors – other information he seeks or receives, other modes of calculation, his personality, his preconceptions, his roles external to the international system – are irrelevant to the model.” In other words, the abstraction of “rational man” is unrealistic.

An emphasis on a rational policy approach by critics of rational choice seems to have been misplaced. Critics of rational choice have tended to seize upon deviations from consistency as evidence of the approach’s undesirability (see Snidal 2002 ; Mercer 2005 ). But apparent inconsistencies may be due to the specific goals or preferences identified by a given theoretical application of rational choice and not necessarily the failure of the rational choice approach (Snidal 2002 ). Other critics have conflated the normative ideal of rationality (i.e., procedural rationality) with the positive (i.e., substantive or instrumental) application of the rational choice approach (see Riker 1990 ; Zagare 1990 ).

During the 1950s, the primary task of decision-making analysts appeared to be that of remedying this apparent dearth of verisimilitude of rational theories. In their seminal statement of the foreign policy decision-making approach, Snyder, Bruck and Sapin ( 1954 ) suggest that the structural application of rationality as an explanatory framework is problematic. Specifically, they claimed that rationality implicitly assumed a fixed range of alternatives under consideration, an exogenous problem situation, and the existence of an objective reality. Snyder and colleagues suggest that the process and choice are products of situational and biographical characteristics of the individual(s) making the decision.

Similarly, Harold and Margaret Sprout ( 1956 ) sought to add verisimilitude to the study of international relations by emphasizing the environmental context within which decisions are made. They argue that the study of foreign policy and military strategy (as outputs of conscious decisions) cannot be divorced from the constraints of the environment. Thus, while decision-makers choose alternatives that are consistent with their own motivations, goals, and values, the range of alternatives is limited by the perceived realities imposed by such factors as climate, topography, and geographical location. Consequently, the Sprouts develop a framework that details the interaction between perceptual environmental factors and foreign policy decision making.

Although these “bedrock” efforts at developing a theory of decision making were seminal in their identification of possible variables, they were the subject of three related criticisms. First, the foreign policy decision-making approach was thought to be inordinately complex and of little utility in guiding empirical research (e.g., McClosky 1956 ; Rosenau 1967 ). Indeed, the attempt to add verisimilitude to the analysis of international relations seemed to work at cross-purposes with one of the aims of theory-construction – abstraction. Second, many of the insights gained from these early decision-making studies were charged with pointing out the obvious through a detailed description of historical facts (Emerson 1958 ). Finally, it was unclear whether the inclusion of additional variables added to the explanatory power of foreign policy decision-making approaches relative to rational accounts (Verba 1961 ). Despite such criticisms, the value of these efforts was in their explicit recognition of foreign policy decisions as the products of individual, conscious decision-makers, reacting to and constrained by what they perceive as the exigencies of an external reality.

The Deterrence Puzzle and the Cognitive Response

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw a turning point in the theoretical development of the foreign policy decision-making approach. Specifically, scholars pondering the deterrence puzzle offered potential solutions to the problem of credibility. Brodie ( 1959 ) explicitly links war and the threat of war with national policy objectives – lending the analysis of decision making to ends–means calculation. Brodie makes much of the concept of “limited war,” arguing that an explicit linkage between political aims and military tactics forces decision-makers to conduct a cost–benefit analysis. Other scholars suggested that nuclear war itself could be conducted in a limited way, reducing the costs of carrying out a threat and enhancing the credibility of a threat (Kaplan 1959 ; Snyder 1961 ). Still others were concerned with how to make nuclear threats intended to shield overseas allies credible (Wohlstetter 1959 ; Schelling 1960 ; 1966 ). Indeed, Schelling ( 1966 ) argues that feigning irrationality in the service of coercion is rational because it is a tactic that, if successful, is expected to yield the preferred outcome.

Throughout the 1950s, alternative models of foreign policy decision making were developed in public administration and psychology and applied to the study of economics and organizational behavior (e.g., Simon 1957 ; March and Simon 1958 ; Lindblom 1959 ). Implicit in the bedrock of foreign policy decision making are many of the studies on personality, organizations, and culture from other disciplines (Snyder et al. 1954 ; Sprout and Sprout 1956 ). Dissatisfaction with explanations of decision making provided by rational choice accounts served as the impetus for the exploration of other perspectives.

Personality and Belief Systems

Research on personality was thought to challenge the assumptions of the rational model by suggesting that the means employed for achieving the specified ends of a decision problem may serve other purposes altogether. Early research on personality and foreign policy decision making used the psychobiographical approach, which analyzed single political actors and sought connections between, for example, childhood traumas and their later foreign policy behavior (see Maoz 1990 :51–4). Subsequent research identified general categories of personality traits thought to influence foreign policy decisions. For example, some studies argued that some individuals’ possessing aggressive tendencies may see the international arena as a convenient outlet to release this aggression (e.g., Farber 1955 ).

Other work appeared to treat leader personalities as intervening variables between sociocultural factors and leaders’ decisions. For instance, decision-makers may possess ethnocentric or nationalistic attitudes learned from their own socialization, which may influence their choices if they seek to satisfy a need to affirm national/ethnic superiority rather than the ends of foreign policy (e.g., Gladstone 1955 ; Levinson 1957 ; Greenstein 1969 ). A set of studies by Margaret Hermann (e.g., 1974 ; 1980 ) identified a set of personality traits – nationalism, control over events, dogmatism, and cognitive complexity – that corresponded to overall foreign policy orientation and behavior of leaders.

Research on personality has evolved into two research agendas. The first explores the impact of leadership styles on foreign policy decision making (e.g., Kissinger 1966 ; Foyle 1999 ; Hermann et al. 2001 ). This approach argues that leadership style influences decisions via delegation-management arrangements. Leaders who tend to delegate and take advice seriously can be expected to have less of an impact on the decision than “micro-managers.” The second research agenda is the operational code approach. Operational code analysis argues that decision-makers’ beliefs as “subjective representations of reality” in political life critically influence (i.e., distort, block, and recast) incoming information (Leites 1951 ; Schafer and Walker 2006 ). Given a stimulus from the external environment, beliefs may steer decision-makers toward some courses of action and away from others (see George 1979b ).

One’s beliefs about international objects (i.e., actors, events, and the decision environment) may be referred to as the decision-maker’s cognitive structure. For example, operational codes, schemas, and cognitive maps all refer to naïve theories held by policy-makers (see, e.g., Axelrod 1973 ). Such cognitive structures drive decisionmakers’ perceptions and responses to international events, aiding the organization and interpretation of data. Information that appears to contradict a decision-maker’s preconceived beliefs may be initially ruled out (e.g., Axelrod 1973 ; Jervis 1976 ), resulting in biased decisions. But when the bulk of information contradicts the initial beliefs, decision-makers may become increasingly vigilant and seek additional information in the evaluation of available options (e.g., Pruitt 1965 :411–14; Maoz 1990 :68).

Situational Variables

A decision-maker’s definition of an event may influence the range of alternatives and the available information-processing capacity (Pruitt 1965 ). Snyder and colleagues assert that the foreign policy decision-making approach is focused by the perspective of the “actor in situation.” In particular, threats and opportunities as well as time pressure and ambiguity are the key characteristics of the situation (see Maoz 1990 :62–9). Given that the rational model developed during the period of the new strategy was largely silent about the effect of the situation, critics seized upon the implicit assumption of a homogeneous process of decision making across varying situations. As Maoz ( 1990 ) observes, perceived threats and opportunities speak to the nature of the decision problem, addressing the question of why a decision-maker needs to make a decision.

Threat perception refers to a decision-making problem that is characterized by the “anticipation of harm” (Lazarus 1968 ). International crises themselves are seen as situational variables possessing an implicit threat component (e.g., Hermann 1969a ; Holsti 1972 ; Cohen 1979 ). The situation is also believed to be characterized by potential opportunities. For instance, George and Smoke ( 1974 :160–2) point out that the exclusion of South Korea from the USA’s defense perimeter in the Pacific created a perceived opportunity for North Korean conquest of its southern neighbor.

Time pressure involves the perceived “clock” for making a decision. For example, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the decision-makers perceived a good deal of time pressure to choose a course of action before the Soviet installation of the missiles was complete. Time pressure is frequently associated with stress (Holsti and George 1975 ). Low levels of situational stress tend to be associated with non-innovative, incremental decision making (e.g., Lindblom 1959 ; Cyert and March 1963 ). However, high-stress situations are also associated with the consideration of well-worn alternatives because of a condensed time frame for response search (Holsti 1979 ; Brecher 1980 ; Stein and Tanter 1980 ). Innovation and a more extensive information search are likely to be undertaken at moderate levels of stress.

The ambiguity of the situation may influence the amount of information processing performed by the decision-maker. Although cognitive structures may lead to decision biases due to the nature and amount of information under consideration (e.g., Axelrod 1973 ; Jervis 1976 ), international crises pose a problem for research on foreign policy decision making. For some scholars (e.g., Schelling 1966 :97), “the essence of a crisis is its unpredictability,” and, hence, its ambiguity. For others (e.g., Hermann 1969a ; Snyder and Diesing 1977 ; Brecher 1979 ), crises are relatively unambiguous because they are characterized by, at a minimum, a high level of threat. Recent research (Mintz 2004b ) has shown that the ambiguity of the decision-making environment can lead to changes in decision strategies. When decision-makers are unfamiliar with a given decision problem, they are likely to rely on simplifying heuristics to deal with the demands of the situation. Decision-makers may also rely on historical analogies to overcome problems associated with unfamiliarity (Khong 1992 ).

Organizational Role Variables

Because foreign policy decision making is largely an organizational endeavor, Snyder et al. ( 1954 ) as well as Rosenau ( 1966 ) identified decision-makers’ organizational roles within the group setting as influential in foreign policy making. Research on organizational roles of decision-makers suggests that alternatives advocated by a given group member are likely to be dictated by their own organizational routines or their own organizational interests (Allison 1971 ). Consequently, foreign policy decisions are likely to be the outgrowth of organizational wrangling rather than an effort to match means with foreign policy ends. Other research focused on the attributes of groups as variables that might condition the influence of organizational effects. For example, Hermann ( 1978 ; see also Hermann and Hermann 1989 ) examines such group features as size, role of the leader, and decision rules on the outcome of deliberations.

A prominent study of foreign policy decision making among small groups found that decision-making quality is compromised when group members seek consensus and personal acceptance (Janis and Mann 1972 ; see also Janis 1982 ; Herek et al. 1987 ). In contrast, research exploring the impact of advisors and coalition partners on decision making (e.g., George 1980 ; Kaarbo 1996 ; Redd 2002 ) suggests that the interests and preferences of key advisors or coalition members must be satisfied in order for a decision to be adopted (Mintz and DeRouen 2009 ).

Early Frameworks

A number of decision-making frameworks emerged during the initial stage of the development of the foreign policy decision-making approach, which sought to integrate decisions-makers’ beliefs, as well as situational and organizational variables. These frameworks saw decision making as a process of mediated stimulus–response in which decision-makers’ cognitive attributes interpret objective reality and identify an option (e.g., Sprout and Sprout 1956 ; Frankel 1963 ). Brecher et al. ( 1969 ) argued that decision-makers possess psychological images of the operational decision-making environment. When a significant gap between the psychological and the operational exists, decision-making quality declines (see also Jervis 1976 ). Two key processing variables were identified: availability and accuracy of information, and the decision-maker’s beliefs. Initial case study research assessing the implications of the Brecher et al. ( 1969 ) framework (e.g., Brecher 1974 ; 1980 ) provided partial support, but additional efforts to extend and test the framework led to the evolution of the International Crisis Behavior project (Brecher 1979 ), which is discussed in greater detail below.

Rosenau ( 1966 ) developed a decision-making framework that, like the others, included a list of variables previously identified by challengers to the rational model. These included, for example, decision-makers’ personalities and organizational roles, as well as attributes of society – public opinion and interest groups. Rosenau ( 1966 ) also suggested that external variables such as events, other states’ behavior and the structure of the international system were important to the decision. But Rosenau’s chief contribution was the argument that these variables were not expected to have an unconditional effect on decisions across all states. Research assessing a framework explicitly privileging cross-national variation in state attributes called for cross-national investigation. Thus, Rosenau’s ( 1966 ) framework launched the Comparative Foreign Policy (CFP) research agenda. CFP research embodied the legacy of the behavioral revolution in foreign policy decision making (see Hudson 2005 ). Using events data – which are discussed below – decision-making researchers examined disparate foreign policy behaviors, which were aggregated and compared. CFP scholars sought to test their hypotheses using large-n studies with both cross-national as well as temporal variation (e.g., Hanrieder 1971 ; McGowan and Shapiro 1973 ; Rosenau 1974 ; East et al. 1978 ; Hermann et al. 1987 ).

Resurgent Rationality

The challenges to rationality from the cognitivist school of foreign policy decision making were met with a forceful restatement of the assumptions of the approach (e.g., Zagare 1990 ). An actor-oriented decision theory emerging in the late 1970s is the expected utility (EU) approach (Wittman 1979 ; Bueno de Mesquita 1981 ). EU asserts that decision-makers choose the alternative that is expected to yield the “largest net gain” (Bueno de Mesquita 1984 :228) and incorporates the probability of attaining the outcome attached to the alternative under consideration.

Perhaps one of the more impressive validations of the expected utility theory has been Bueno de Mesquita’s forecasting efforts (e.g., Bueno de Mesquita 1984 ; 1998 ). Relying on area experts to identify competing groups and salient issues, expected utility forecasting has offered real-time predictions of a number of specific events. For example, real-time forecasts predicted leadership changes in the Soviet Union as well as the policy shift of the Iranian leadership in the mid-1980s.

Incorporating the assumptions of rationality, game theory explicitly models the process of strategic interaction inherent in international relations. Using formal methods, scholars seek to discover how decision-makers “should choose among options to gain their desired ends” (Morrow 2000 :165). Each decision-maker considers the likely choices of other actors in the situation and chooses the option believed to yield the most preferred alternative. Game theory has been used to attempt to integrate decision making and structural theories of international relations (e.g., Snyder and Diesing 1977 ) as well as offer explanations of linkages between domestic politics and foreign policy behavior (e.g., Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman 1992 ).

Perhaps the most progressive advances in the approach have concerned noncooperative game theory, which has offered a good deal of leverage on such concepts as signaling, bargaining, and commitment (see, e.g., Morrow 2000 ). Noncooperative game theory has also offered insights into the roles of concepts that were previously thought to be within the exclusive purview of cognitive perspectives. For example, the solution concept of Bayesian equilibrium reflects the beliefs, perceptions, and limited availability of information for each decision-maker in the game. Kim and Bueno de Mesquita ( 1995 ) model the effect of perceptions in strategic crisis decision making. Fearon ( 1995 ) suggests that miscalculation due to, essentially, misperception has been responsible for war.

Models of Decision

Cross-disciplinary research on organizational behavior during the 1950s and 1960s began to specify a model of decision making that contrasted with the rational model discussed above. Models of decision making typically specify processing characteristics by describing how individuals acquire and assess information, as well as how a final choice is selected among alternatives under consideration. These information processing characteristics and decision rules may lead to biases and deviations from an ideal rational choice.

Bounded Rationality/Cybernetic Model

Simon ( 1957 ) proposed a model of bounded rationality. According to the model, individuals are thought to possess cognitive constraints on their information-processing capacities such that it is impossible for a decision-maker to identify all potential alternatives and adequately assess their implications. If a dynamic model of sequential decision making is considered, the problem is further complicated. Simon suggests that a decision made today may yield optimal benefits for the current problem, but the current decision may actually work against an optimal outcome in subsequent decision problems (see also Lindblom 1959 ).

The model of bounded rationality/cybernetic decision making assumes an order-sensitive search process by which the sequence in which alternatives are considered will influence the selection of a choice. Rather than maximize with respect to a goal, decision-makers are thought to employ a satisficing selection rule – the first alternative that is deemed satisfactory is adopted. In terms of information processing, the model assumes that decision-makers limit the amount of information considered at any given time to that deemed relevant to the single alternative under consideration, eliminating the complexity associated with pair-wise comparisons of all available alternatives (Steinbruner 1974 :66).

Empirical research evaluating the bounded rationality/cybernetic model with respect to foreign policy decision making offers qualified support (see Marra 1985 ; Ostrom and Job 1986 ). Perhaps the most prominent example is Ostrom and Job ( 1986 ), which applies a cybernetic model of decision to presidential decisions to use force.

Organizational Politics Model

An outgrowth of Simon’s ( 1957 ) work on bounded rationality is the organizational process model. The seminal work here is Cyert and March ( 1963 ; see also March and Simon 1958 ), which argues that the alternatives available for addressing a given problem are typically determined ex ante by organizational routines and standard operating procedures. The organizational role of a decision-maker is likely to influence foreign policy decisions via predetermined routines and areas of responsibility. A problem cannot be addressed with resources or processes that do not exist; the choice is likely to be one that is organizationally feasible and promises adequate success with respect to implementation.

Although the organizational process model had existed for some time, and bedrock studies (Snyder et al. 1954 ; Rosenau 1966 ) posited the importance of organizational roles, Allison ( 1969 ; 1971 : ch. 3) was perhaps the first to apply the model to a foreign policy decision in his analysis of the Cuban Missile Crisis. He argues that the decision to blockade Cuba can be understood as an available option – i.e., such options as a “surgical” air strike were not said to be available as a routine option – with a preexisting plan for implementation. Since Allison’s ( 1971 ) work, however, relatively little effort has been made to apply the organizational process model to foreign policy decisions. Welch ( 1992 ) suggests that this may be the case because there has been some conflation of the organizational process model with the bureaucratic politics model.

Bureaucratic Politics Model

The bureaucratic politics model has its roots in research on bureaucracies and foreign policy (e.g., Huntington 1960 ; Hilsman 1967 ). According to Allison’s ( 1971 ) formulation of the model, foreign policy decisions are made by a collective executive (i.e., a cabinet) with each member of the group possessing his or her own bureaucratic interests. The position/choice advocated by any group member is likely to be one that serves his or her bureaucratic interests. Specifically, they seek to “promote the positions their organizations have taken in the past” that “are consistent with the interests their organization represents” (Feldman 1989 :13). The process by which decisions are made can be characterized by the “pulling and hauling” of group bargaining (Allison and Halperin 1972 :43). The choice selected by the group is likely to reflect the preferences of the group member(s) who is best able to garner “bargaining advantages, skill and will in using bargaining advantages, and other players’ perceptions of the first two ingredients” (Allison and Halperin 1972 :50). Much of the empirical support for the bureaucratic politics approach was produced through the analysis of defense policy decisions (Allison and Halperin 1972 ; Halperin 1974 ), finding that US decisions concerning arms production and limitations were consistent with the bureaucratic approach.

Two criticisms have been leveled at the bureaucratic politics model. First, although billed as an alternative to the rational choice model, bureaucratic politics is not inconsistent with group decision making assuming rationality (Maoz 1990 ; Christensen and Redd 2004 ). Each group member advocates the alternative (means) that is expected to serve his or her own bureaucratic interests (ends). Second, the model fails to account for the hierarchical structure of the decision-making unit under investigation (Hermann and Hermann 1989 ). The model assumes that the US president is among equals in the cabinet (Rosati 1981 ). But the president has sufficient authority to overrule any member of the cabinet (Smith 1985 ; Bendor and Hammond 1992 ).

Prospect Theory

Unlike the rational choice approach, prospect theory assumes that preferences over alternatives are not transitive, but depend on net asset levels vis-à-vis a reference point – gains and losses from a frame of reference (Kahneman and Tversky 1979 :277). Decision-makers treat gains and losses asymmetrically, overvaluing losses relative to commensurate gains. This asymmetry produces a nonlinear utility function characterized by greater steepness on the loss side than on the gain side. Consequently, decision-makers pursue a strategy of loss aversion, which has been corroborated in a number of studies (Kahneman and Tversky 1979 ; Tversky and Kahneman 1981 ). The central implication of framing and loss aversion is that decision-makers will pursue riskier strategies to reverse losses, but eschew risk when gains have been accumulated.

In foreign policy decision making, risk taking in order to avoid (or reverse) losses has been shown to be associated with decisions involving crisis situations (e.g., McDermott 1992 ; Whyte and Levi 1994 ; Berejikian 2002 ). But a persistent criticism of prospect theory concerns the central concept of framing (see, e.g., Levy 1997 ; Mintz and Redd 2003 ). Decision-makers may perceive themselves in the domain of loss and pursue risky strategies when an objective evaluation of the situation would warrant risk-averse strategies. This subjectivity is complicated by the finding that individuals tend to accommodate to gains more quickly than they do to losses (Kahneman et al. 1991 ). After a series of gains, a decision-maker may regard any subsequent setbacks as losses rather than forgone gains, pursuing risky strategies. But after a series of losses, a decision-maker may not accommodate as quickly, weighing any subsequent gains against cumulative losses and pursuing risk-seeking behavior to eliminate those losses. Clearly, framing poses significant problems for scholars seeking to test the implications of prospect theory (see Boettcher 1995 ).

Poliheuristic Theory

An effort to integrate cognitive and rational approaches to foreign policy decision making is poliheuristic theory (e.g., Mintz et al. 1997 ; Mintz and Geva 1997 ; Mintz 2004a ). Poliheuristic theory postulates a two-stage decision-making process in which leaders utilize a dimension-based search of the alternatives, ruling out those that fail to satisfy requirements on a key, noncompensatory dimension in the first stage of the process. In the second stage, a final choice is made through the analytic (i.e., rational) comparison of the remaining alternatives (see, e.g., Mintz et al. 1997 ; Mintz 2004a ). The noncompensatory heuristic (cognitive shortcut) employed in the first stage reduces the menu of alternatives to a manageable set, reducing the mental effort required in the search for a choice. This procedure is thought to mirror the process by which individuals make decisions. The use of the noncompensatory principle for the elimination of unsatisfactory/unlikely alternatives is also useful for scholars in analyses of leaders’ foreign policy decisions – in both theory-testing and forecasting projects.

Poliheuristic theory is thought to account for a variety of phenomena, including crisis decision making (e.g., Mintz 1993 ; DeRouen and Sprecher 2004 ; Brulé and Mintz 2006 ), international bargaining (Astorino-Courtois and Trusty 2000 ), and the influence of political advisors in foreign policy making (e.g., Redd 2002 ; 2005 ; Mintz 2005 ). The theory is also thought to be useful as guide for policy-makers. The noncompensatory principle can aid policy-makers and intelligence analysts by reducing the amount of information needed to anticipate a foreign leader’s response to a crisis. If policy-makers possess information concerning the domestic political criteria that a leader considers, alternatives that are not expected to satisfy these criteria can be ruled out.

Recent Advances

Research from neuroscience suggests that emotions may play an important part in decision making (Crawford 2000 ; McDermott 2004 ). As human beings, decision-makers are not always cool and thoughtful. Foreign policy decisions may be influenced by hate, fear or anger. In contrast, emotions may serve as cues to policy-makers concerning how to make sense of incoming information, actually enabling decisions that approximate rationality. Recent studies have used fMRI and response time analysis better to explain decisions.

Much has been made of the lack of synthesis in the foreign policy decision-making literature. Mintz ( 2007 ) proposes that cognitive approaches should be organized and synthesized within a new paradigm – behavioral international relations. Because most cognitive theories posit a flexible view of information-processing characteristics and decision rules, they can be categorized and integrated according to their defining features. Like the behavioral paradigm in economics, finance, and marketing, cognitive and social approaches to understanding international relations have collectively generated an important set of research agendas: theories, concepts, and findings (Mintz 2007 ).

Methodological Approaches to Theory Testing

The evaluation of foreign policy decision-making theories has employed a variety of methodological approaches and strategies. The division of labor across decision-making research programs can be seen as a multi-method approach to theory testing, employing case studies, large-n statistical analyses, simulations and experiments.

Small-n Studies

A frequently underappreciated approach in political science is the case study method (e.g., Collier 1993 ). The case study has been the workhorse of decision-making analysis. For example, Snyder and Paige ( 1958 ; see also Paige 1968 ) evaluated the Snyder et al. ( 1954 ) framework using the case of the Korean War onset. Perhaps the most prominent case study is Allison’s ( 1971 ) many observations – or “cuts” – of the Cuban Missile Crisis. But, consistent with other political science fields during the discipline’s behavioral revolution, international relations sought to become more scientific. Specifically, scientific progress meant (among other things) being able to quantify and replicate analyses. Traditional case studies were not regarded as satisfactory (e.g., Kaplan 1966 ).

The 1914 Project of Robert North and colleagues (e.g., North et al. 1963 ; Holsti et al. 1968 ) answered the call for greater rigor. The project sought to examine leaders’ perceptions of messages during the political crisis leading to World War I in the context of a mediated stimulus–response model. Although the project contributed to the scientific study of IR through the development of the content analysis method and the coding of events, it was largely abandoned due to two problems. First, regardless of the number of discrete events identified during the 1914 crisis, the project focused on a single case, which cast doubt on its generalizability (Jervis 1967 ). Second, the theoretical model guiding the collection and coding of data explicitly pointed to the importance of the subjectivity of human decision making (i.e., perceptions, images, biases, etc.). Efforts to identify and measure the effects of subjectivity were problematic, although the non-quantitative supporting materials (footnotes, quotations, etc.) offer more persuasive support (Jervis 1967 ).

Other efforts to offer greater rigor to small-n research in decision making include the structured focused comparison of a small number of cases (George 1979a ). This approach was used rather prominently in deterrence research by George and Smoke ( 1974 ). More recently, Patrick James and colleagues (James and Zhang 2005 ; Sandal et al. 2007 ) used the structured focused comparison approach to evaluate the foreign policies of China and Turkey.

Events Data

The scientific advancement of foreign policy research via large-n statistical studies during the late 1950s and early 1960s faced practical problems concerning the level and units of analysis (e.g., Singer 1961 ; Guetzkow and Jensen 1966 ). Foreign policy decisions are undertaken by individuals who represent nation-states, but such decisions produce events, or outcomes, in the international system. The examination of international events appeared to overcome these challenges and appeared to be analogous to the vote in American politics (see Hudson 2005 ), facilitating the analysis of large-n data sets.

The ascent of “events data” in decision-making research was driven by US government funding (Andriole and Hopple 1981 ; Laurance 1990 ). Although interest in (and funding for) events data began to dry up during the late 1970s and early 1980s, some events data projects survive. For example, the Kansas Events Data System (KEDS) project of the University of Kansas continues to collect data (see, e.g., Gerner et al. 1994 ; Schrodt 1995 ). Others live on because they have proven useful for hypothesis testing; these include McClelland’s ( 1976 ) WEIS (the World Event/Interaction Survey), Azar and colleagues’ ( 1975 ) COPDAB (the Conflict and Peace Data Bank), and the CREON project. The Interstate Behavior Analysis project evolved into the well-known Interstate Crisis Behavior (ICB) project, which has been recently updated (Brecher and Wilkenfeld 2000 ).

Simulations and Experiments

Many of the issues of pressing importance to scholarly research during the behavioral revolution (e.g., nuclear war and proliferation) had not occurred in large numbers (if at all), posing an obstacle to quantitative analysis. The use of simulations appears to have emerged in response to these challenges. Generally speaking, a simulation is an operating model of a system. Relevant variables are given values and a specified routine operates until the model is “solved” – some outcome is achieved.

Simulations may be “manual” – conducted with human participants playing specified roles and aided only by pencils and paper – all-computer – performed entirely by a computer carrying out programmed routines – or of the “man–machine” variety, carried out using some combination of human participants and computing power (see Verba 1964 ). The purpose of the simulation is to test hypotheses relating the manipulated independent variables and the outcome. Such an approach facilitates the examination of scenarios that have yet to be observed, or have been observed only a small number of times (e.g., Guetzkow et al. 1963 ). Two “man–machine” process-tracing simulators are the Decision Board (e.g., Mintz et al. 1997 ) and the DecTracr (Geva).

Efforts to exploit the desirable features of simulations were carried out in earnest during the 1960s. At Northwestern University, Guetzkow and colleagues (e.g., Guetzkow et al. 1963 ) developed the Inter-nation Simulation; a RAND–MIT collaboration produced the Political Military Exercise (Bloomfield and Whaley 1965 ); and Raytheon developed a simulation program dubbed TEMPER (Abt 1964 ). The all-computer variety of simulations frequently used events data for inputs. For example, the North et al. ( 1963) 1914 Project was used extensively to simulate the exchange of diplomatic communiqués (e.g., Pool and Kessler 1965 ; Hermann and Hermann 1967 ; Hermann 1969b ). More recently, computational modeling using cognitive maps as inputs has had some success in reproducing US foreign policy (Taber 1997 ). Simulations have continued to prove useful for research (e.g., Bueno de Mesquita 1998 ; Bennett and Stam 2008 ) and teaching (e.g., Starkey and Blake 2001 ).

But the manual and man–machine variants of simulations were increasingly seen as complementary tools for experimentation. Experiments are particularly well suited for isolating causal variables and decomposing complex phenomena (Kinder and Palfrey 1993 ), which facilitates the relatively direct assessment of the process by which individuals make decisions. For example, Semmel and Minix ( 1979 ) use an experimental design to evaluate group dynamics in decision making. Using a computerized process-tracing platform in an experimental setting, Mintz et al. ( 1997 ) find that individuals are likely to use an attribute or dimension-based choice search when the number of alternatives is relatively large, but analytic methods when the choice set is of a more manageable size.

Directions for Future Research

As a perspective, the foreign policy decision-making approach is diverse and somewhat disjointed. In particular, the gulf between the rational choice approaches and cognitive psychological approaches appears to have stymied progress (see Brulé 2008 ). But beyond this larger debate, the “actor-specific” perspective seems to be operating in relative isolation from other subfields within international relations. Two recommendations are believed to help reverse the current state of affairs.

Scholars working within the cognitivist school should develop theories of decision making that incorporate many of the cognitive conceptual inputs in a logical and coherent framework (see Mintz 2007 ). As it stands now, many concepts, such as leadership or framing, tend to be considered in relative isolation. But such concepts may have interactive effects on foreign policy decision making. Consideration of the glut of cognitive inputs in a unified framework may contribute to cumulation within the subfield.

Second, decision-making scholars should pursue a multi-method approach to theory testing using experimental, statistical, and case study methods (e.g., Maoz et al. 2004 ). Each of these methods has unique strengths that complement the others. Although the subfield as a whole can be regarded as employing a multi-method approach, individual scholars tend to focus on their own preferred methods. For example, scholars privileging cognitive variables tend to prefer experiments and simulations, while rationalists tend to prefer large-n statistical analyses. Each school points to supportive evidence and suggests that spuriousness is responsible for the results of the other schools. Consequently, the competing decision-making schools have developed largely in mutual isolation, each dominant in its own realm (see, e.g., Kaufmann 1994 ; Rosati 2000 ). Such mutual isolation, however, does not bode well for progress in the study of international relations or foreign policy analysis. If each theory is evaluated using a variety of methods, results can be more easily compared.

- Abt, C. (1964) War Gaming. International Science and Technology 32, 29–37.

- Allison, G. (1969) Conceptual Models and the Cuban Missile Crisis. American Political Science Review 63, 689–718.

- Allison, G. (1971) Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis . Boston: Little, Brown.

- Allison, G. , and Halperin, M. (1972) Bureaucratic Politics: A Paradigm and Some Implications. In R. Tanter and R. Ullman (eds.) Theory and Policy in International Relations , Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 40–79.

- Andriole, S.J. , and Hopple, G.W. (1981) The Rise and Fall of Events Data: Thoughts on an Incomplete Journey from Basic Research to Applied Use in the US Department of Defense. Unpublished paper, US Department of Defense, Washington, DC.

- Arrow, K.J. (1951) Social Choice and Individual Values . New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Astorino-Courtois, A. , and Trusty, B. (2000) Degrees of Difficulty: The Effect of Israeli Policy Shifts on Syrian Peace Decisions. Journal of Conflict Resolution 44, 359–77.

- Axelrod. R. (1973) Schema Theory: An Information Processing Model of Perception and Cognition. American Political Science Review 67, 1248–66.

- Azar, E.E. , and Ben-Dak, J. (eds.) (1975) Theory and Practice of Events Research . New York: Gordon and Breach.

- Bendor, J. , and Hammond, T.H. (1992) Rethinking Allison’s Models. American Political Science Review 86, 301–22.

- Bennett, D.S. , and Stam, A.C. (2008) Simulating a Bargaining Theory of War. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Peace Science Society (International), Columbia, SC, Nov. 2–4.

- Berejikian, J.D. (2002) A Cognitive Theory of Deterrence. Journal of Peace Research 39, 165–84.

- Bloomfield, L. , and Whaley, B. (1965) The Political–Military Exercise: A Progress Report. Orbis 8, 854–70.

- Boettcher, W.A., III (1995) Context, Methods, Numbers, and Words: Evaluating the Applicability of Prospect Theory to International Relations. Journal of Conflict Resolution 39, 561–83.

- Brecher, M. (1974) Decisions in Israel’s Foreign Policy . New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Brecher, M. (1979) State Behavior in International Crises. Journal of Conflict Resolution 23, 446–80.

- Brecher, M. (1980) Decisions in Crisis: Israel, 1967 and 1973 . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Brecher, M. , and Wilkenfeld, J. (2000) A Study of Crisis . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Brecher, M. , Steinberg, B. , and Stein, J. (1969) A Framework for Research on Foreign Policy Behavior. Journal of Conflict Resolution 13, 75–101.

- Brodie, B. (ed.) (1946) The Absolute Weapon: Atomic Power and World Order . New York: Harcourt, Brace.