COVID-19: Stress and Anxiety

[Additional essays and videocasts regarding psychological ramifications of the COVID-19 virus outbreak can be found at: https://communitiescollaborating.com/[

The COVID-19 virus knows all about the human psyche. The virus is aware that we experience stress and become anxious when we keep a distance from other people and are forced to isolate ourselves from direct, physical contact with the people we love and cherish. Under conditons of stress and as we become more anxious, our vulnerability also increases — leaving us even more anxious. A vicious cycle . . . and a cycle that we need to stop!!

This essay includes material prepared by members of the Global Psychology Task Force–a group of experienced professional psychologists from around the world who have come together to address the psychological ramifications of the COVID-19 virus. They have prepared a website (www.communities collaborating.com) that incorporates essays, video clips and links to other references that address these ramifications. This essay is derived from the content of this website.

Stress Ruts, Lions and Lumens

We start with a brief video presentation by Dr. William Bergquist, a member of the Global Psychology Task Force. He has titled his presentation: “Stress Ruts, Lions and Lumens in the Age of the Pandemic”:

Reducing the Stress and Anxiety

This essay concerns the way to reduce the stress and anxiety. In addressing this psychological dynamic we turn to both the anxiety aroused by those who have tested positive for the virus and those who have not been tested or have been tested and are negative but still worry about the physical and psychological health of other people in their life, as well as their own economic health and the economic and societal health of their community and country.

https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/3/21/21188362/manage-anxiety-pandemic

We turn now to someone who have been infected by COVID-19

Managing the Anxiety as Someone Who Has Been Infected

The anxiety associated with any major illness is quite understandable and is not in any way a sign of weakness. There are many ways in which to address this anxiety–such as looking to loved ones for support (even if they can’t be physically present), reducing other sources of stress in one’s life, identifying daily plans for dealing with the virus–and most importantly taking actions that enable you to feel less powerless and victimized.

It is perhaps best to turn from these general recommendations to the insights offered by someone who has been infected and struggled for a lengthy period of time with the infestation and related fever and isolation. This person is Dr. Suzanne Brennen-Nathan, one or our Global Psychology Task Force members. Suzanne is a highly experienced psychotherapist who has specialized in the treatment of trauma in her clinical practice. Who better to reflect on the illness and offer recommendations then someone “who has been there” and has expertise in the traumatizing impact of a major illness like COVID-19. Suzanne has been interviewed by Dr. William Bergquist, another member of the Task Force:

Managing the Anxiety as Someone Who Hasn’t Been Tested or Is Negative But Still Fearful

What about those of us who have not tested positive for COVID-19 or have not been tested at all. At the heart of the matter in facing the challenges associated with the COVID-19 virus — whether these challenges be financial, vocational or family related–is the stress that inevitably is induced when we think about, feel about and take action about the virus’ threatening nature.

We therefore begin this statement about action to be taken with an excellent presentation by one of our task force members, Christy Lewis:

To begin a cross-cultural reflection on the psychological ramifications of the COVID-19 virus, we offer an essay on the way in which one of our Task Force members, Eliza Wong, Psy.D., works with highly anxious clients in her home country: Singapore.

Dealing with Anxiety during COVID-19 in Singapore

We hope these perspectives on stress and anxiety in the age of the COVID-19 virus invasion provides some guidance for you in better understanding the psychological impact of the virus and identifying actions you can take to help ameliorate this impact.

- Related Articles

- More By William Bergquist

- More In Health / Biology

The Shattered Tin Man Midst the Shock and Awe in Mid-21st Century Societies I: Shattering and Shock

Lay me down to sleep: designing the environment for high quality rest, the wonder of interpersonal relationships via: culprits of division and bach family members as exemplars of relating midst differences, i dreamed i was flying: a developmental representation of competence, snuggling in: what makes us comfortable when we sleep, the intricate and varied dances of friendship i: turnings and types, leadership in the midst of heath care complexity ii: coaching, balancing and moving across multiple cultures, leadership in the midst of heath care complexity i: team operations and design, delivering health care in complex adaptive systems i: the nature of dynamic systems, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

I wish to introduce a quite different interpretation regarding the presence of flight in t…

- Counseling / Coaching

- Health / Biology

- Sleeping/Dreaming

- Personality

- Developmental

- Cognitive and Affective

- Psychobiographies

- Disclosure / Feedback

- Influence / Communication

- Cooperation / Competition

- Unconscious Dynamics

- Intervention

- Child / Adolescent

- System Dynamics

- Organizational Behavior / Dynamics

- Development / Stages

- Organizational Types / Structures

- System Dynamics / Complexity

- Assessment / Process Observation

- Intervention / Consulting

- Cross Cultural

- Behavioral Economics

- Technologies

- Edge of Knowledge

- Organizational

- Laboratories

- Field Stations

- In Memoriam

- COVID-19 and your mental health

Worries and anxiety about COVID-19 can be overwhelming. Learn ways to cope as COVID-19 spreads.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, life for many people changed very quickly. Worry and concern were natural partners of all that change — getting used to new routines, loneliness and financial pressure, among other issues. Information overload, rumor and misinformation didn't help.

Worldwide surveys done in 2020 and 2021 found higher than typical levels of stress, insomnia, anxiety and depression. By 2022, levels had lowered but were still higher than before 2020.

Though feelings of distress about COVID-19 may come and go, they are still an issue for many people. You aren't alone if you feel distress due to COVID-19. And you're not alone if you've coped with the stress in less than healthy ways, such as substance use.

But healthier self-care choices can help you cope with COVID-19 or any other challenge you may face.

And knowing when to get help can be the most essential self-care action of all.

Recognize what's typical and what's not

Stress and worry are common during a crisis. But something like the COVID-19 pandemic can push people beyond their ability to cope.

In surveys, the most common symptoms reported were trouble sleeping and feeling anxiety or nervous. The number of people noting those symptoms went up and down in surveys given over time. Depression and loneliness were less common than nervousness or sleep problems, but more consistent across surveys given over time. Among adults, use of drugs, alcohol and other intoxicating substances has increased over time as well.

The first step is to notice how often you feel helpless, sad, angry, irritable, hopeless, anxious or afraid. Some people may feel numb.

Keep track of how often you have trouble focusing on daily tasks or doing routine chores. Are there things that you used to enjoy doing that you stopped doing because of how you feel? Note any big changes in appetite, any substance use, body aches and pains, and problems with sleep.

These feelings may come and go over time. But if these feelings don't go away or make it hard to do your daily tasks, it's time to ask for help.

Get help when you need it

If you're feeling suicidal or thinking of hurting yourself, seek help.

- Contact your healthcare professional or a mental health professional.

- Contact a suicide hotline. In the U.S., call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline , available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Or use the Lifeline Chat . Services are free and confidential.

If you are worried about yourself or someone else, contact your healthcare professional or mental health professional. Some may be able to see you in person or talk over the phone or online.

You also can reach out to a friend or loved one. Someone in your faith community also could help.

And you may be able to get counseling or a mental health appointment through an employer's employee assistance program.

Another option is information and treatment options from groups such as:

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Self-care tips

Some people may use unhealthy ways to cope with anxiety around COVID-19. These unhealthy choices may include things such as misuse of medicines or legal drugs and use of illegal drugs. Unhealthy coping choices also can be things such as sleeping too much or too little, or overeating. It also can include avoiding other people and focusing on only one soothing thing, such as work, television or gaming.

Unhealthy coping methods can worsen mental and physical health. And that is particularly true if you're trying to manage or recover from COVID-19.

Self-care actions can help you restore a healthy balance in your life. They can lessen everyday stress or significant anxiety linked to events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Self-care actions give your body and mind a chance to heal from the problems long-term stress can cause.

Take care of your body

Healthy self-care tips start with the basics. Give your body what it needs and avoid what it doesn't need. Some tips are:

- Get the right amount of sleep for you. A regular sleep schedule, when you go to bed and get up at similar times each day, can help avoid sleep problems.

- Move your body. Regular physical activity and exercise can help reduce anxiety and improve mood. Any activity you can do regularly is a good choice. That may be a scheduled workout, a walk or even dancing to your favorite music.

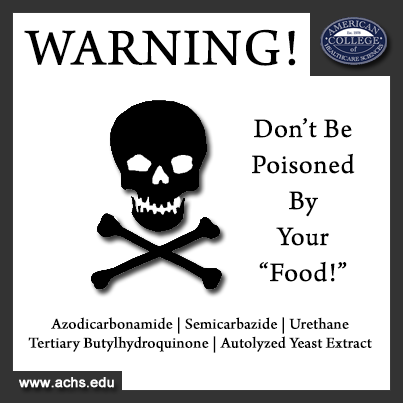

- Choose healthy food and drinks. Foods that are high in nutrients, such as protein, vitamins and minerals are healthy choices. Avoid food or drink with added sugar, fat or salt.

- Avoid tobacco, alcohol and drugs. If you smoke tobacco or if you vape, you're already at higher risk of lung disease. Because COVID-19 affects the lungs, your risk increases even more. Using alcohol to manage how you feel can make matters worse and reduce your coping skills. Avoid taking illegal drugs or misusing prescriptions to manage your feelings.

Take care of your mind

Healthy coping actions for your brain start with deciding how much news and social media is right for you. Staying informed, especially during a pandemic, helps you make the best choices but do it carefully.

Set aside a specific amount of time to find information in the news or on social media, stay limited to that time, and choose reliable sources. For example, give yourself up to 20 or 30 minutes a day of news and social media. That amount keeps people informed but not overwhelmed.

For COVID-19, consider reliable health sources. Examples are the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Other healthy self-care tips are:

- Relax and recharge. Many people benefit from relaxation exercises such as mindfulness, deep breathing, meditation and yoga. Find an activity that helps you relax and try to do it every day at least for a short time. Fitting time in for hobbies or activities you enjoy can help manage feelings of stress too.

- Stick to your health routine. If you see a healthcare professional for mental health services, keep up with your appointments. And stay up to date with all your wellness tests and screenings.

- Stay in touch and connect with others. Family, friends and your community are part of a healthy mental outlook. Together, you form a healthy support network for concerns or challenges. Social interactions, over time, are linked to a healthier and longer life.

Avoid stigma and discrimination

Stigma can make people feel isolated and even abandoned. They may feel sad, hurt and angry when people in their community avoid them for fear of getting COVID-19. People who have experienced stigma related to COVID-19 include people of Asian descent, health care workers and people with COVID-19.

Treating people differently because of their medical condition, called medical discrimination, isn't new to the COVID-19 pandemic. Stigma has long been a problem for people with various conditions such as Hansen's disease (leprosy), HIV, diabetes and many mental illnesses.

People who experience stigma may be left out or shunned, treated differently, or denied job and school options. They also may be targets of verbal, emotional and physical abuse.

Communication can help end stigma or discrimination. You can address stigma when you:

- Get to know people as more than just an illness. Using respectful language can go a long way toward making people comfortable talking about a health issue.

- Get the facts about COVID-19 or other medical issues from reputable sources such as the CDC and WHO.

- Speak up if you hear or see myths about an illness or people with an illness.

COVID-19 and health

The virus that causes COVID-19 is still a concern for many people. By recognizing when to get help and taking time for your health, life challenges such as COVID-19 can be managed.

- Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. National Institutes of Health. https://covid19.nih.gov/covid-19-topics/mental-health. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Mental Health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic's impact: Scientific brief, 2 March 2022. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Mental health and the pandemic: What U.S. surveys have found. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/03/02/mental-health-and-the-pandemic-what-u-s-surveys-have-found/. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Taking care of your emotional health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coping/selfcare.asp. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- #HealthyAtHome—Mental health. World Health Organization. www.who.int/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome/healthyathome---mental-health. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Coping with stress. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/stress-coping/cope-with-stress/. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Manage stress. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/myhealthfinder/topics/health-conditions/heart-health/manage-stress. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- COVID-19 and substance abuse. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/covid-19-substance-use#health-outcomes. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- COVID-19 resource and information guide. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/NAMI-HelpLine/COVID-19-Information-and-Resources/COVID-19-Resource-and-Information-Guide. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Negative coping and PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/gethelp/negative_coping.asp. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Health effects of cigarette smoking. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm#respiratory. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- People with certain medical conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Your healthiest self: Emotional wellness toolkit. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/health-information/emotional-wellness-toolkit. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- World leprosy day: Bust the myths, learn the facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/leprosy/world-leprosy-day/. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- HIV stigma and discrimination. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/hiv-stigma/. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Diabetes stigma: Learn about it, recognize it, reduce it. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/features/diabetes_stigma.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Phelan SM, et al. Patient and health care professional perspectives on stigma in integrated behavioral health: Barriers and recommendations. Annals of Family Medicine. 2023; doi:10.1370/afm.2924.

- Stigma reduction. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/od2a/case-studies/stigma-reduction.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Nyblade L, et al. Stigma in health facilities: Why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Medicine. 2019; doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1256-2.

- Combating bias and stigma related to COVID-19. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19-bias. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Yashadhana A, et al. Pandemic-related racial discrimination and its health impact among non-Indigenous racially minoritized peoples in high-income contexts: A systematic review. Health Promotion International. 2021; doi:10.1093/heapro/daab144.

- Sawchuk CN (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. March 25, 2024.

Products and Services

- A Book: Endemic - A Post-Pandemic Playbook

- Begin Exploring Women's Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Future Care

- Antibiotics: Are you misusing them?

- COVID-19 and vitamin D

- Convalescent plasma therapy

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- COVID-19: How can I protect myself?

- Herd immunity and respiratory illness

- COVID-19 and pets

- COVID-19 antibody testing

- COVID-19, cold, allergies and the flu

- COVID-19 tests

- COVID-19 drugs: Are there any that work?

- COVID-19 in babies and children

- Coronavirus infection by race

- COVID-19 travel advice

- COVID-19 vaccine: Should I reschedule my mammogram?

- COVID-19 vaccines for kids: What you need to know

- COVID-19 vaccines

- COVID-19 variant

- COVID-19 vs. flu: Similarities and differences

- COVID-19: Who's at higher risk of serious symptoms?

- Debunking coronavirus myths

- Different COVID-19 vaccines

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

- Fever: First aid

- Fever treatment: Quick guide to treating a fever

- Fight coronavirus (COVID-19) transmission at home

- Honey: An effective cough remedy?

- How do COVID-19 antibody tests differ from diagnostic tests?

- How to measure your respiratory rate

- How to take your pulse

- How to take your temperature

- How well do face masks protect against COVID-19?

- Is hydroxychloroquine a treatment for COVID-19?

- Long-term effects of COVID-19

- Loss of smell

- Mayo Clinic Minute: You're washing your hands all wrong

- Mayo Clinic Minute: How dirty are common surfaces?

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pregnancy and COVID-19

- Safe outdoor activities during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Safety tips for attending school during COVID-19

- Sex and COVID-19

- Shortness of breath

- Thermometers: Understand the options

- Treating COVID-19 at home

- Unusual symptoms of coronavirus

- Vaccine guidance from Mayo Clinic

- Watery eyes

Related information

- Mental health: What's normal, what's not - Related information Mental health: What's normal, what's not

- Mental illness - Related information Mental illness

5X Challenge

Thanks to generous benefactors, your gift today can have 5X the impact to advance AI innovation at Mayo Clinic.

Stress and decision-making during the pandemic

More than 18 months into the coronavirus pandemic, Americans remain in limbo between lives once lived and whatever the post-pandemic future holds. For many, the current reality encompasses a daily web of risk assessment, upended routines and endless news about the state of COVID-19 in the world, America and our individual communities.

October 26, 2021

A new survey conducted by The Harris Poll on behalf of the American Psychological Association found that stress levels are holding steady from recent years, and despite many struggles, U.S. adults retain a positive outlook. Most (70%) were confident that everything will work out after the coronavirus pandemic ends, and more than three-quarters (77%) said, all in all, they are faring well during the coronavirus pandemic.

However, behind this professed optimism about the future, day-to-day struggles are overwhelming many. Prolonged effects of stress and unhealthy behavior changes are common. Daily tasks and decision-making have become more difficult during the pandemic, particularly for younger adults and parents. As each day can bring a new set of decisions about safety, security, growth, travel, work, and other life requirements, people in the United States seem to be increasingly wracked with uncertainty.

U.S. adults are struggling with daily decisions, especially millennials

For many, the pandemic has imposed the need for constant risk assessment, with routines upended and once trivial tasks recast in light of the pandemic. Many people ask, “What is the community transmission in my area today and how will this affect my choices? What is the vaccination rate? Is there a mask mandate here?” When the factors influencing a person’s decisions are constantly changing, no decision is routine. And this is proving to be exhausting.

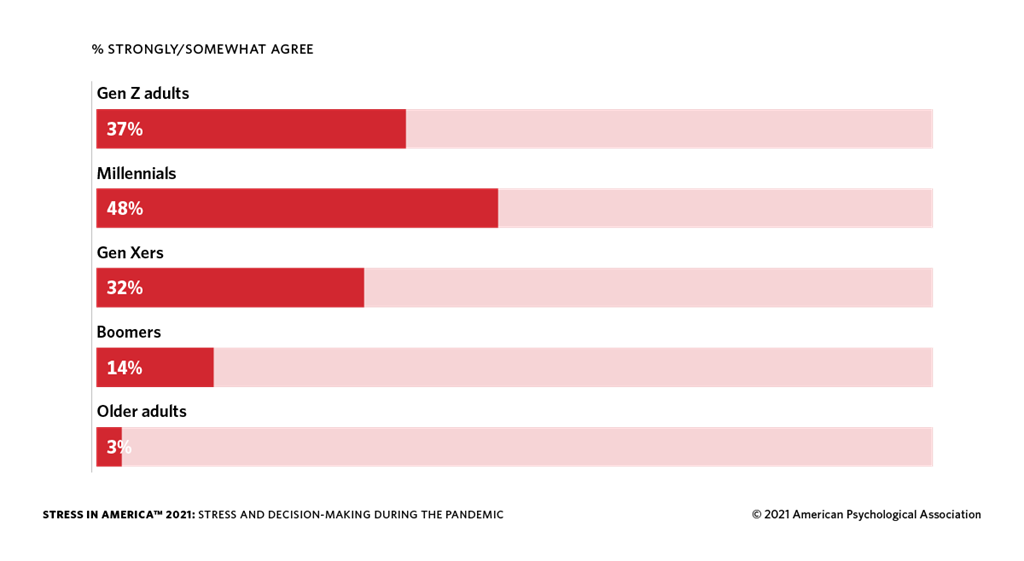

According to the survey, nearly one-third of adults (32%) said sometimes they are so stressed about the coronavirus pandemic that they struggle to make basic decisions, such as what to wear or what to eat. Millennials (48%) were particularly likely to struggle with this when compared with other groups (Gen Z adults: 37%, Gen Xers: 32%, Boomers: 14%, older adults: 3%).

View a full-sized version of the image available for download.

View a full-sized version of the image with a description.

More than one-third said it has been more stressful to make day-to-day decisions (36%) and major life decisions (35%) compared with before the coronavirus pandemic. Younger adults were more likely to feel these decisions are more stressful now (daily decisions: 40% of Gen Z adults, 46% of millennials, and 39% of Gen Xers vs. 24% of boomers, and 14% of older adults; major decisions: 50% of Gen Z adults and 45% of millennials vs. 33% of Gen Xers, 24% of boomers, and 6% of older adults). And slightly more than three in five (61%) agreed the coronavirus pandemic has made them rethink how they were living their life.

More than three in five (63%) agreed that uncertainty about what the next few months will be like causes them stress, and around half (49%) said that the coronavirus pandemic has made planning for their future feel impossible.

When it comes to overall stress, it is not surprising to find that younger generations, who were more likely to say they struggle with basic decisions, also reported generally high stress levels. Gen Z adults (5.6 out of 10 ), millennials (5.7), and Gen Xers (5.2) reported higher average stress levels over the past month related to the coronavirus pandemic than boomers (4.3) and older adults (2.9). This pattern was mirrored in the groups’ respective ability to manage stress; around half of Gen Z adults (45%) and millennials (50%) said they do not know how to manage the stress they feel due to the coronavirus pandemic, compared with 32% of Gen Xers, 21% of boomers, and 12% of older adults.

1 On a scale of one to 10 where one means “little to no stress” and 10 means “a great deal of stress.”

More dependents, more decisions—pandemic parenting stress persists

Decision-making fatigue is having a disproportionate impact on parents, given changes to work, school, and everyday routines during the pandemic. Many are struggling to manage households divided by vaccination status, with one set of rules for vaccinated adults and kids over age 12 and another for younger unvaccinated children—not to mention varying health conditions that may exist.

The ongoing uncertainty and changes seem to be compounding struggles for parents, especially for those with younger children. For instance, parents with children under age 18 were more likely than those without children to say that both day-to-day decisions and major life decisions are more stressful than they were pre-pandemic (daily: 47% vs. 30%; major: 44% vs. 31%), with 54% of those with young children ages zero to four reporting that day-to-day decisions have become more stressful.

Moreover, almost half of parents reported that sometimes they are so stressed about the coronavirus pandemic that they struggle to make basic decisions (e.g., what to wear, what to eat) (47% vs. 24% of non-parents). Meanwhile, the majority made at least one major life decision during the coronavirus pandemic (62% vs. 35% of non-parents), illustrating a decision-making paradox that seems to have emerged: despite uncertainty and decision difficulty, major life changes still occur.

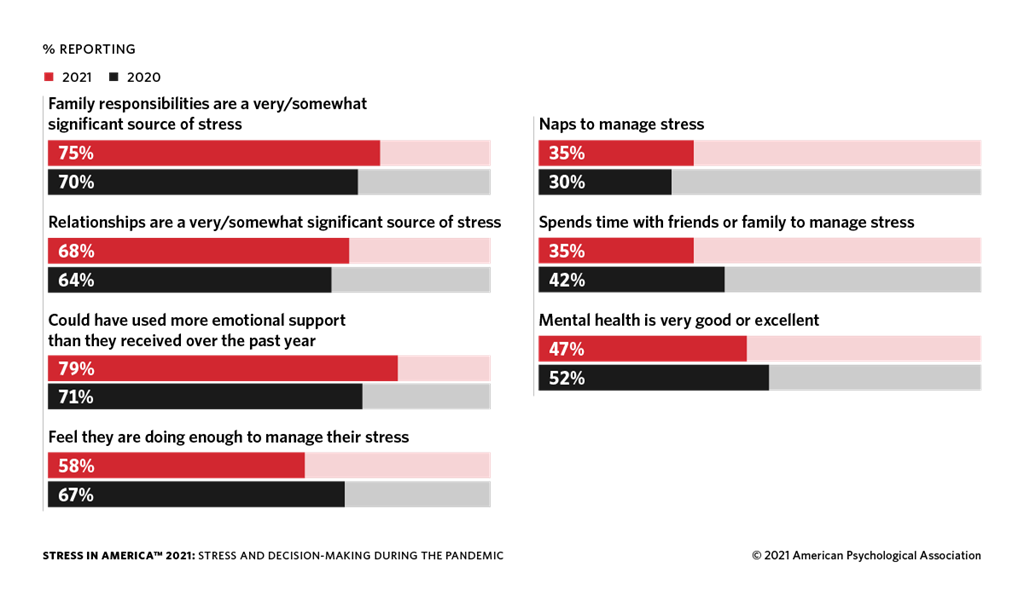

All of this is wearing on parents as the pandemic persists. And while most parents said they are faring well during the coronavirus pandemic, they were less likely to say so than non-parents (71% vs. 80%). Further, compared with 2020, parents were:

- More likely to say family responsibilities (75% vs. 70% of parents in 2020) and relationships (68% vs. 64%) are significant sources of stress in their lives.

- More likely to feel they could have used more emotional support than they received over the past year (79% vs. 71%).

- Less likely to feel they are doing enough to manage their stress (58% vs. 67%).

- More likely to nap (35% vs. 30%) to manage their stress but less likely to spend time with friends or family (35% vs. 42%).

- Less likely to say their mental health is very good or excellent (47% vs. 52%).

Pandemic stress among people of color is still elevated, especially for Hispanic adults

Hispanic and Black adults were less likely to say they are faring well during the coronavirus pandemic than non-Hispanic White adults, though the levels still speak to an overall positive outlook (81% of non-Hispanic White adults vs. 68% of Hispanic adults and 72% of Black adults). Still, in line with the overall survey findings, this optimistic finding stands in contrast to the reality of compounding pandemic-related stressors bearing down on marginalized communities, especially Hispanic adults.

For example, Hispanic adults were more likely than non-Hispanic White adults to say decision-making has become more stressful compared with before the pandemic (day-to-day decisions: 44% vs. 34%; major decisions: 40% vs. 32%), and Hispanic and Black adults were more likely than non-Hispanic White adults to say sometimes they are so stressed about the coronavirus pandemic that they struggle to make even basic decisions (e.g., what to wear, what to eat, etc.) (38% and 36% vs. 29%, respectively).

Hispanic adults reported the highest levels of stress, on average, over the past month related to the coronavirus pandemic (5.6 vs. Black adults: 5.1; Asian adults: 5.1; non-Hispanic White adults: 4.8). Moreover, Hispanic adults were most likely to say they are struggling with the ups and downs of the coronavirus pandemic (61% vs. 51% of non-Hispanic White adults and 51% of Black adults) and that they don’t know how to manage the stress they feel due to the pandemic (43% vs. 33% and 34%, respectively).

This unequal burden of stress on Hispanic adults was not surprising, considering findings from the survey that shine a light on racial and ethnic disparities in relation to the impact of the pandemic. Specifically, Hispanic adults were more likely than non-Hispanic White adults to know someone who had been sick with or died of COVID-19 (sick: 64% vs. 46%; died: 42% vs. 25%).

Stress levels remain higher than pre-pandemic levels, work- and housing costs-related stress on the rise

The average reported level of stress during the past month among all adults was 5.0, which has held steady from 2020. Still, this level is slightly elevated from pre-pandemic levels (2021: 5.0; 2020: 5.0; 2019: 4.9; 2018: 4.9; 2017: 4.8; 2016: 4.8).

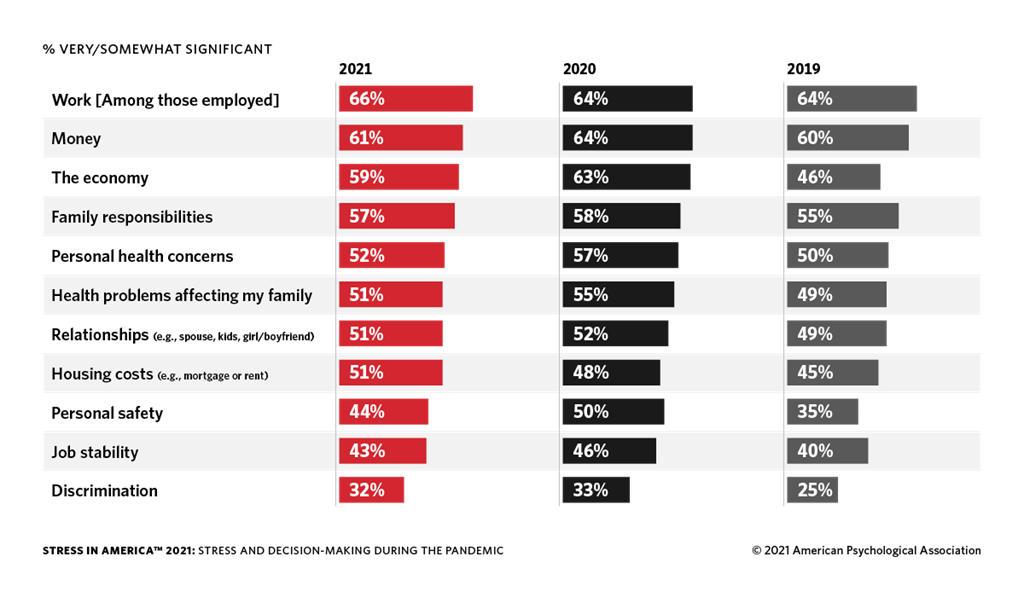

And while a year over year comparison of significant sources of stress shows a downward trend across most factors, work- and housing costs-related stress slightly increased from 2020. Additionally, all sources of stress remain somewhat higher than pre-pandemic levels, with the economy, housing costs, personal safety, and discrimination representing more dramatic spikes.

Significant sources of stress: 2019–2021

Many are suffering from the impacts of stress, younger adults and parents continue to bear the brunt

As a result of stress, nearly three-quarters of U.S. adults (74%) have experienced various impacts in the last month, such as headaches (34%), feeling overwhelmed (34%), fatigue (32%), or changes in sleeping habits (32%). Again, younger adults and parents were more likely to report this, with 86% of millennials reporting impacts of stress, closely followed by Gen Z adults (84%) and Gen Xers (77%); only 59% of boomers and 57% of older adults said the same. Parents were also more likely than non-parents to report experiencing impacts of stress in the last month (83% vs. 69%).

Further, the majority of adults (59%) said they have experienced behavior changes as a result of stress in the past month. Most commonly, the changes had been avoiding social situations (24%), altering eating habits (23%), procrastinating or neglecting responsibilities (22%), or altering physical activity levels (22%). In conjunction with changes in eating habits and physical activity, more than one-third said they eat to manage their stress, which remains elevated after increasing during the first year of the pandemic (25% in 2019, 37% in 2020, and 35% in 2021).

- Gen Z adults: 79%; millennials: 74%; Gen Xers: 64% versus boomers: 37%; older adults: 17%

- Parents: 75% vs. non-parents: 50%

Resilience among populations varies, some are faring better than others

Generally speaking, U.S. adults are adjusting through the pandemic, but some show fewer signs of resiliency than others. More than half of U.S. adults (53%) agreed they are struggling with the ups and downs of the coronavirus pandemic. Further, slightly more than one-quarter (26%) have low resilience, as determined by a score of 1.00 to 2.99 on the Brief Resilience Scale. Fifty-eight percent had average resilience (a score of 3.00 to 4.30) and 16% had high resilience (a score of 4.31 to 5.00), the survey found.

Younger adults, parents, and those with an annual household income of less than $50K were more likely than their respective counterparts to have a low resilience score. Those with low resilience scores were more likely than those with average or high resilience to say:

- Their stress level, on average, over the past month related to the pandemic has been higher (average: 6.3 vs. 4.9 and 3.3).

- The level of stress in their life increased compared with before the pandemic (53% vs. 43% and 24%).

- Making decisions has become more stressful compared with before the pandemic (day-to-day decisions: 55% vs. 33% and 16%; major decisions: 54% vs. 32% and 13%).

- Sometimes they are so stressed about the coronavirus pandemic that they struggle to make even basic decisions (50% vs. 31% and 5%).

Further, those with low resilience scores were around three times as likely to have experienced negative impacts of stress in the last month (94% vs. 75% and 38%), particularly feeling overwhelmed (57% vs. 29% and 12%) and behavior changes as a result of stress (85% vs. 56% and 25%), particularly avoiding social situations (41% vs. 20% and 10%).

Speaking to the struggles of this group, those with low resilience scores were more likely to be taking actions to manage their stress (98% vs. 92% and 80%), but also to feel they could have used more emotional support than they received over the past year (88% vs. 60% and 25%).

Methodology

The August/COVID Resilience Survey was conducted online within the United States by The Harris Poll on behalf of the American Psychological Association between August 11 and August 23, 2021, among 3,035 adults age 18+ who reside in the United States.

Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish. Data were weighted to reflect their proportions in the population based on the 2020 Current Population Survey (CPS) by the U.S. Census Bureau. Weighting variables included age by gender, race/ethnicity, education, region, and household income. Hispanic adults were also weighted for acculturation, taking into account respondents’ household language as well as their ability to read and speak in English and Spanish. Country of origin (United States/non-United States) was also included for Hispanic and Asian subgroups. Weighting variables for Gen Z adults (ages 18 to 24) included education, age by gender, race/ethnicity, region, household income, and size of household, based on the 2019 CPS. Propensity score weighting was used to adjust for respondents’ propensity to be online.

Parents are defined as U.S. adults ages 18+ who have at least one person under the age of 18 living in their household at least 50% of the time for whom they are the parent or guardian.

Generational definitions are as follows: Gen Z adults (ages 18 to 24), millennials (ages 25 to 42), Gen Xers (ages 43 to 56), boomers (ages 57 to 75), and older adults (ages 76+).

Related resources

- Report document (PDF, 4.48MB)

- Survey questions (PDF, 222KB)

- Press release: Pandemic impedes basic decision-making ability

- Contact : Sophie Bethune ( email ) Telephone: (202) 336-6134

- 2021 Work and Well-being Survey report

- 2021 COVID-19 Practitioner Survey report

- Parental burnout: How to recognize and overcome it

- Stress and uncertainty

- What's the difference between stress and anxiety?

- Stress's effects on the body

- More stress information and topics

View the Stress in America TM press room.

- Find a Doctor

- Patients & Visitors

- ER Wait Times

- For Medical Professionals

- Piedmont MyChart

- Medical Professionals

- Find Doctors

- Find Locations

Receive helpful health tips, health news, recipes and more right to your inbox.

Sign up to receive the Living Real Change Newsletter

Managing stress during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic

Are you feeling stress, fear and anxiety amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic ? If so, you’re not alone. The recommendations for masking and social distancing affect nearly every part of our lives, including finances, relationships, transportation, jobs and healthcare.

Some common causes of stress during the coronavirus pandemic are uncertainty, lack of routine and reduced social support, says Mark Flanagan, LMSW, MPH, MA, a social worker at Cancer Wellness at Piedmont .

Routines and COVID-19

As humans, we don’t like uncertainty and tend to thrive in routines , says Flanagan. Routines are essential because they create a sense of normalcy and control in our lives. This sense of control then allows us to manage the challenges that come our way.

“When we don’t have a routine, much of our time is spent trying to establish one,” says Flanagan. “Without a routine, we often pay attention to the things that are most ‘flashy.’ When big news happens, we tend to focus on it more.”

Social support and COVID-19

Not only are our routines currently disrupted, but the routines of everyone around us are as well.

“When something goes wrong in our lives, we can usually rely on others to get a sense of calm,” he says. “But when everyone is experiencing the same sense of uncertainty, there’s no real ‘anchor’ to help manage some of the stress.”

Stress affects your health

Stress management is essential for good physical health , and it’s especially important right now as our world addresses the COVID-19 pandemic .

“While short-term pressures and stress are normal and can help us change in positive ways , chronic stress causes a huge deterioration in our quality of life on a physical level,” says Flanagan. “When we are more pessimistic, depressed or anxious, our immune system goes down and produces more stress hormones, reducing our immunity and increasing inflammation.”

Stress can also put a strain on your mental health, relationships and productivity, he notes.

Stress reduction tips for COVID-19

“Rather than dwell on nervousness, focus on the things you can control,” Flanagan suggests. “When you move the locus of control from something outside yourself to inside yourself, you powerfully reduce anxiety and boost confidence.”

He suggests the following steps to regain control and reduce stress.

Follow the recommended health guidelines. These guidelines include getting the COVID-19 vaccine , frequent hand-washing, wearing a mask in public places, social distancing, practicing respiratory etiquette and cleaning commonly used surfaces. See the latest recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Not only will you protect your health, but you’ll also protect the health of vulnerable people in your community, like older adults and those with serious or underlying health issues.

Create a morning routine. When you’re stuck at home, it can be tempting to let go of basic routines, but Flanagan says a morning routine can help you feel more productive and positive. Consider waking up at the same time each day, exercising, showering, meditating, journaling, tidying your home or having a healthy breakfast as part of your morning ritual.

Check in with loved ones regularly. Staying in touch with family and friends can help reduce stress.

Consider ways to help others. This can include picking up groceries for a neighbor and leaving them at their door, donating to a local charity, or purchasing gift cards from your favorite restaurant. By taking the focus off yourself, you can experience reduced stress and a greater sense of well-being.

Have a daily self-care ritual. Self-care can include exercise, meditation, walking outside, reading, taking a bubble bath, painting, journaling, gardening, cooking a healthy meal or enjoying a favorite hobby. Pick one thing and do it at the same time each day. It will help anchor your day and provide a welcome respite.

Limit news and media consumption. “When we constantly check our newsfeeds and see bad news, it activates our sympathetic nervous system and can send us into fight-or-flight mode,” says Flanagan. He recommends limiting how often you check the news to once or twice a day (ideally not first thing in the morning or after dinner), turning off news alerts, and obtaining information from one or two reputable news outlets.

Set boundaries around social media. “There’s this concept of toxic sociality where we constantly have to be connected, even in superficial ways, and when we’re not, it feels like part of us isn’t being ‘fed,’” he explains. “It’s important to practice social distancing with social media too. We may not think we’re having any effect on our newsfeed, but we can take steps to reduce the ripple effect of panic on social media.” He suggests posting positive messages online and being mindful of your likes, shares and comments.

Meditate. Meditation can help restore your sense of control as you focus on your breath or a positive word or phrase. “ Meditation can help you activate your parasympathetic nervous system, and that’s an antidote to fear,” says Flanagan. “And when you’re more centered, you’re able to create a calm reality around you.” Try this guided meditation to get started.

Encourage others. “Often, when we are scared, it can be tempting to repeat negative messages, but actively encouraging family and friends is really important,” he says. “Chances are, someone is having a harder time than you are. Your words matter and people will respond accordingly. It’s important to realize we are not victims; we are helping to create our environment and change it for the better. By sending positive messages out into the world, you’ll not only affect those around you, but those words will come back to you.”

Hope during the coronavirus pandemic

“It’s important to remember that this will pass sooner or later,” says Flanagan. “The world has gone through many different challenges, like disease outbreaks, war and uncertain times. For better or worse, these times always pass. That doesn’t mean this time isn’t significantly challenging, but if we focus on what we can control and do things that are good for our health and the health of those around us, we will come out of this in perhaps a more whole state and with a renewed perspective. It’s important to look toward the future and begin building for that future. You can always have hope. Hope never leaves us.”

For information on coronavirus (COVID-19), including symptoms, risks and ways to protect yourself, click here.

- coronavirus

- infectious disease

- stress management

Related Stories

Schedule your appointment online

Schedule with our online booking tool

*We have detected that you are using an unsupported or outdated browser. An update is not required, but for best search experience we strongly recommend updating to the latest version of Chrome, Firefox, Safari, or Internet Explorer 11+

Share this story

Download the Piedmont Now app

- Indoor Hospital Navigation

- Find & Save Physicians

- Online Scheduling

Download the app today!

7 Ways to Manage Stress During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Taking it easy when it feels like the world is on fire..

Posted March 20, 2020 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- What Is Stress?

- Take our Burnout Test

- Find a therapist to overcome stress

As I write this, I am sitting in the living room of an apartment I rented on Airbnb in Nashville, Tennessee. Two weeks ago, my family and I were here for a tango marathon when dancers from across the country flocked to the Music City for a weekend of good times, southern charm, and the warm embrace of Argentine tango. We made new friends, caught up with old ones, and left with nothing but fond memories. When we arrived at our next destination, we learned that just after we left, tornadoes ripped through Nashville and other parts of Tennessee, devastating the city we love and had enjoyed so much. A lot can happen in a day.

The coronavirus was on the news and definitely a topic of conversation, but most of the people we talked to felt optimistic . Two weeks later, and it seems to be all anyone can think about. The stores are empty, stripped clean of essential items like toilet paper and milk, and the bars and restaurants that help make this city so much fun are closed. Face masks are common, and every cough or sneeze causes momentary panic. In other countries, and even in other cities and states, citizens have been ordered to remain in their homes, and all large gatherings of people have been canceled. A lot can happen in a couple of weeks.

We are back in Nashville because of our own cancelations. My partner Sarah is a tango dancer, and I am a touring public speaker, and both of us are self-employed. We were on our way to Memphis for a series of speaking gigs when we started receiving the notifications, one after another after another until our entire tour had been canceled. We live on the road as we work, so a canceled tour also means we need to find somewhere to call home for a bit. Being just a couple of hours shy of Nashville, we decided to hole up here for a few days and plan our next steps.

To say our situation is stressful is an understatement. There are a lot of people who have it worse, but we have lost all our income for the next three months, our housing, and we have a little girl to consider as well. It is a tough spot, and yet both of us are in relatively good spirits. Neither of us has dealt with anything like this before, but we both handle stress well and remain optimistic, even when the global situation seems to get worse and worse. How do we do it?

Drugs. Lots and lots of drugs.

I am joking, of course. Sarah and I are both highly resilient people. In fact, the canceled tour was about stress management , a subject that I have been speaking to audiences about for years. I even wrote a book on the subject, The Art of Taking It Easy , and have been putting those skills to practice all my life. Sarah puts her own stress management skills to test every day by having to deal with me.

The coronavirus pandemic, and the reaction to it, may seem as if the world is on fire. Granted, I have never seen anything like this in my lifetime (which probably overlaps significantly with your lifetime), so it might be on a larger scale, but it is still just another source of stress in a long line of things that cause stress. Stress is stress regardless of the source, and the tools to manage it are the same. Allow me to share a few here.

Before I do, please note that I am discussing how we can manage our stress, anxiety , or worrisome reactions to the pandemic, not the coronavirus itself. Also, if you have been personally affected by the coronavirus, I wish you or your loved ones a healthy recovery. My goal here is to help most of us stay calm or, as I like to put it, take it easy.

1. Assess your threat level. When overwhelmed with worry or fear , it is sometimes helpful to inform yourself of the facts to assess your personal level of threat. For example, earlier in the month, I had a moment of concern and looked up the infection statistics at the time. There were about 120,000 people known to have the virus out of the nearly 8 billion people that live on this planet. Also, most of those cases were in China while my feet were planted firmly in the United States.

Digging even deeper, I found that there were only seven cases in my state and none of them in my area. I assessed my threat level as low and slept easily that night. Now, you might say, “But, Brian, what about all those people that could be spreading the virus without knowing it?” to which I’d answer that I am trying to reduce anxiety, not add to it. Once you have assessed your threat, then it is important to…

2. Identify what you can control. When we encounter stress, any stress, it is important that we ask ourselves if we can do anything about it. If there is some action we can take, then taking that action will help reduce our anxiety. For example, experts emphasize the importance of handwashing to minimize the spread of the virus. Most of us are capable of washing our hands, so wash your damn hands more often than you do.

If the experts say avoid crowded areas, then avoid crowded areas, and live with the comfort of knowing that you are doing all you can to reduce your exposure. However, what if, after a couple of weeks of social isolation , you’ve become a handwashing obsessed hermit, and you still feel anxious? Well…

3. Accept what you cannot control. Focus on what you can do, not what you can’t. There are always going to be variables that are out of your control, and that is part of what makes viruses so frightening. We can never know whether we have been in contact. We can’t control our government’s attempts at containment. We can’t control the loss of income we have experienced or the circumstances that put us back in Nashville.

Sometimes, the healthiest thing we can do is accept that there is nothing we can do. Worrying, complaining, ruminating, and wishing things were different are thoughts we will entertain, but if we focus on them too much, they’ll amplify our stress. Regarding all sorts of stress, I ask people all the time: If there is nothing you can do about it, why are you worried about it? Worrying does nothing but make the problem worse. If you are doing all you can and find that you are still overly focused on things that are outside of your control, you may want to try…

4. Actively changing negative thoughts. Did you know that the only part of your brain you have direct, voluntary control over is the part you think with? If you didn’t, that should be really great news, because it is those very thoughts that are contributing to the anxiety you may be feeling during this pandemic.

What we think influences how we feel, and I often tell people if they don’t like the way they feel to change their thoughts. So, if your brain is too frequently occupied by worries about the virus, anger about social distancing, or sorrow over lost income, then change those thoughts. Simply redirect your attention to a new subject whenever needed. Any new stimulus or activity will help change our thoughts. For example, we could listen to music, do the dishes, read a book, go for a walk, literally anything we can do will help change the channel in our head. This brings me to…

5. Staying active. One thing great about this pandemic is that it is happening during the age of the internet. We may be isolating ourselves physically, but we have an amazing opportunity to connect with others virtually.

Over the last few weeks, I have seen some incredible coping strategies as people in quarantine zones are doing what they can to stay active. I’ve seen videos of opera singers in Italy serenading their neighbors from the windows. There are tango dancers that formed the group “I’m not dancing the tango, so I am doing this instead” to share new hobbies, crafts, and other goofy pursuits. There are people who have started working out or learning to cook.

Painting, making music, or creating art, in general, can be very helpful. A lot of people I know are using this time to catch up on their reading list, and if that sounds appealing, I know a book that would make a great addition to that list. Staying active is great, but we can also work on…

6. Positive thinking . Remember earlier when I mentioned the only part of your brain you have voluntary control over is the part you think with? Another thing worth noting is that you can only hold a few thoughts in mind at any given time. So, if you are having positive, optimistic thoughts, there isn’t much room left for dwelling on negativity.

Monty Python once sang “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life,” and while it may have been played for laughs, but there is truth there. Positive thinking and optimism help us pull through. Not to sound like a blind optimist, but things will absolutely get better. And, speaking of playing things for laughs, don't forget about…

7. Humor . My seminars on stress management are popular because I use a lot of humor in my presentations. In fact, humor is a natural stress-management tool. Coping with and minimizing stress is what humor is for. Laughter relieves anxiety, lowers stress hormones , and helps us to calm down. I can’t tell you how to find humor in your situation, but as much as we can, we need to laugh and just take it easy.

So, work from home if you can, avoid crowds, wash your hands, and try to keep your mind off of the negativity as we all wait this one out. As for us, in the morning, we will be packing up and making our way to stay with family for the next month or so. I don’t know when or if we will be able to tour again, but I am sure we will be OK. Today we hung out with our friend Shawn, who lives in Nashville. Keeping with the protocol of social distancing, Sarah and I refused to talk to him.

Brian King, Ph.D. , trained as a neuroscientist and psychologist and travels the world as a comedian and public speaker. he is the author of The Art of Taking It Easy and The Laughing Cure .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Open access

- Published: 17 May 2022

Stress management in nurses caring for COVID-19 patients: a qualitative content analysis

- Mahboobeh Hosseini Moghaddam ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3381-4559 1 ,

- Zinat Mohebbi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2995-0264 1 &

- Banafsheh Tehranineshat ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2066-5689 2

BMC Psychology volume 10 , Article number: 124 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

8688 Accesses

9 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Being in the frontline of the battle against COVID-19, nurses need to be capable of stress management to maintain their physical and psychological well-being in the face of a variety of stressors. The present study aims to explore the challenges, strategies, and outcomes of stress management in nurses who face and provide care to COVID-19 patients.

The present study is a qualitative descriptive work that was conducted in teaching hospitals affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Iran, from June 2020 to March 2021. Sixteen nurses who were in practice in units assigned to COVID-19 patients were selected via purposeful sampling. Data were collected through semi-structured, individual interviews conducted online. The collected data were analyzed using MAXQDA 10 according to the conventional content analysis method suggested by Graneheim and Lundman.

The data collected in the interviews resulted in 14 subcategories under 4 main categories: providing care with uncertainty and anxiety, facing psychological and mental tension, creating a context for support, and experiencing personal-professional growth.

Conclusions

The nurses caring for COVID-19 patients needed the support of their authorities and families to stress management. Providing a supportive environment through crisis management training, providing adequate equipment and manpower, motivating nurses to achieve psychological growth during the pandemic can help them manage stress.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Today, COVID-19 is a life-threatening disease all over the world and has become an international concern and a global emergency [ 1 ]. Following the spread of the infection to more than 150 countries and its reaching pandemic proportions, the healthcare personnel, especially nurses, have been in the frontline of providing care to the infected [ 2 ]. The nature of healthcare professions, nursing in particular, involves working in highly stressful conditions [ 3 ]. The results of several studies show that prolonged exposure to stress can cause nurses and other healthcare personnel to suffer such consequences as a reduction in their physical and psychological health, lower job satisfaction, reduced efficiency and quality of care, and an increase in the rate of job burnout [ 2 , 4 ].

The members of healthcare teams, especially nurses, are exposed to many occupational hazards and experience high levels of stress as a result. According to a study, the nurses who cared for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) patients suffered from high levels of psychological distress [ 5 ]. At the height of SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) epidemic, nurses and medical students in Taiwan and Saudi Arabia who cared for the infected showed signs of psychological issues, including anxiety, stress and aggressiveness [ 6 ]. Fear and anger were other distressful emotions experienced by nurses who provided care to MERS-CoV patients in Saudi Arabia [ 7 ].

The results of recent studies show that the healthcare personnel have experienced high levels of anxiety since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 1 , 8 ]. The pandemic also affected the psychological health of a considerable number of healthcare professionals in Spain, so much so that their resilience was at risk in case of another wave of the infection. Severe stress was often caused by fear of being infected and infecting one’s loved ones. These difficult conditions resulted in care providers’ lack of empathy with COVID-19 patients and inconsistency in caring for the patients [ 9 ]. According to another study in South America, many healthcare professionals experienced lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), including gowns, masks, and face shields, during the pandemic. Concern about lack of equipment and fear of being infected were greater in the personnel who were involved in procedures in which aerosols were produced. Some care providers had to use their gowns and N95 masks several times because there was a shortage of protective equipment [ 10 ]. A study by Zhang et al. (2020) in China showed that, in the early stages of caring for COVID-19 patients, nurses were divided between their professional commitment and fear of being infected. The nurses who had been isolated for 1–2 weeks suffered emotional exhaustion; they were able to adapt psychologically after 3–4 weeks of working in isolated wards [ 11 ].

According to studies in Iran, the causes of care providers’ heightened anxiety in caring for COVID-19 patients are fear of being infected, the difficulty of controlling the pandemic and lack of medical equipment [ 1 , 12 , 13 ], death anxiety, the little-known nature of the infection, lack of time, spread of bad news, obsessive thoughts and the public’s disregard for preventive measures [ 14 ]. Another study in Iran reported administrative issues to be the most significant source of stress for nurses who provide care to COVID-19 patients [ 15 ].

Long working hours and work overload, exposure to infection and close contact with COVID-19 patients, the stigma of being a potential carrier of the infection, social media pressures, and increase in the number of death cases lead to fatigue, despair, and helplessness in the nurses and undermine the quality and quantity of nursing care [ 12 ]. Other consequences of job fatigue in nurses are absence, delay, job burnout, and concentration disorders, with adverse effects on patient safety [ 16 , 17 ].

Compared to the other professionals in the healthcare system, nurses spend more time with patients and play a key role in controlling and treating emerging diseases [ 18 ]. Research shows that nurses have experienced higher levels of occupational and psychological stress during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 8 , 17 ]. Nurses’ psychological health correlates with the quality of healthcare services, and occupational stress is one of the most influential factors in the psychological health of this population [ 19 ]. Accordingly, it is necessary to evaluate nurses’ mental health and stress management skills in facing and caring for COVID-19 patients and to identify barriers to their stress management during the current pandemic. Considering the above-mentioned points and the fact that the researchers could not find any studies which investigated nurses’ stress management at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, a qualitative study could provide an in-depth understanding of the subject in question. Accordingly, the present study uses a qualitative approach to explore the challenges, strategies, and outcomes of stress management in nurses who face and provide care to COVID-19 patients.

Materials and methods

The present study is a qualitative descriptive work of research with a content analysis design which was conducted from June 2020 to March 2021 in teaching hospitals affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. The participants of the study were nurses who were in practice in hospitals dedicated to the treatment of COVID-19 patients or back-up hospitals. As the pandemic continued, all the hospitals in Iran had to admit COVID-19 patients; thus, in every hospital, certain wards, including surgical and internal wards, were assigned to the care and treatment of the infected.

In total, 16 nurses who were in practice in special care, internal, surgical and emergency departments were selected via purposeful sampling [ 20 ]. Sampling continued until the data was saturated, i.e. no new knowledge could be obtained and the categories were saturated in terms of characteristics and dimensions. The researchers reached data saturation after 14 interviews. However, two more interviews were conducted to verify data saturation. Analysis of the last two interviews did not yield any new codes. The research team and two qualitative research experts examined the codes to verify that the data were saturated.

The inclusion criteria were: having a bachelor’s degree in nursing, having at least six months’ experience of full-time practice as a clinical nurse, having at least 2 weeks’ experience of caring for COVID-19 patients, and willingness to share one’s experiences with the researchers. The subjects who were not willing to be interviewed or continue their participation in the study were excluded. Data were collected through 16 in-depth, semi-structured, individual interviews which were conducted by the third author.

The participants were interviewed by video calls with “WhatsApp”, in workplace (one of the classes at school of nursing and midwifery), after arrangements about the time of the interviews had been made with them. Each interview lasted from 40 to 60 min and began with a general question: “Can you describe your experiences of a work shift in which you faced or cared for a COVID-19 patient?” Subsequently, the interviewer asked more specific questions: “What are your experiences of the challenges and barriers to stress management when you faced and cared for COVID-19 patients?”, “What factors improve stress management when nurses face and care for COVID-19 patients?”, “What factors undermine stress management when nurses face and care for COVID-19 patients?”, “How did you feel when/if you could not manage your stress when you faced and cared for COVID-19 patients?”, “What stress management strategies can help nurses who face and care for COVID-19 patients?” and “What are the outcomes of stress management for nurses who face and care for COVID-19 patients?” Moreover, follow-up questions were asked to obtain more details about the objective of the study (Additional file 1 : Interview Guide). The participants' voices were recorded using a Sony Voice Recorder ICD-TX650.

The present study used the conventional content analysis method suggested by Graneheim and Lundman (2004). Frequently used in studies related to nursing, this method allows for collecting new, rich information and mental analysis of the content of textual data through systematic categorization, codification and theme making or developing known paradigms [ 21 , 22 ]. Each interview was transcribed in full immediately after it was completed. To immerse in the data and obtain a general idea of the participants’ answers, the researchers read the transcripts several times. Words, phrases and paragraphs which carried significance with regard to the challenges, strategies and outcomes of stress management in the COVID-19 crisis were selected as meaning units. Similar initial codes were classified into broader categories based on their similarities and differences and categories were thus developed. To ensure that the codes were consistent, the researchers reviewed the categories and compared them to the data again. Afterward, through deep and accurate contemplation and comparison of the categories against each other, the themes emerged [ 23 ]. The data were organized using MAXQDA 2010 distributed by VERBI.

The trustworthiness of the collected data was ensured using Lincoln and Guba’s criteria [ 24 ]. Credibility was achieved through prolonged engagement with the data, member checking, peer debriefing, maximum variation sampling, and searching for contrasting evidence. To ensure dependability and confirmability, the researchers relied on audit trial which consists of using proper techniques to conduct interviews, making accurate transcripts and having the data reviewed by one’s co-researchers. To enhance the transferability of the results, the researchers provided accurate and thorough descriptions of the subject under study, the participants’ characteristic, methods of data collection and analysis, along with documented examples of the participants’ statements [ 25 ].

The participants’ ages ranged from 25 to 48 years, with the mean being 34.93 years. The majority of the participants were female (Table 1 ). Analyses of the data resulted in 510 initial codes, 14 subcategories and four main categories, namely: providing care with uncertainty and anxiety, facing psychological and mental tension, creating a context for support, and experiencing personal-professional growth (Table 2 ). Table 3 presents an example of meaning units, coding, and development of sub-categories and categories. Providing care with uncertainty and anxiety and facing psychological and mental tension were the challenges which the nurses in the present study experienced when they faced and cared for patients with COVID-19.

Providing care with uncertainty and anxiety

One of the findings of the present study was providing care with uncertainty and anxiety. This category consisted of the subcategories of providing care as a professional duty, concern over transmitting the infection to one’s family, fear of the unknown aspects of the disease, and concern over making wrong decisions.

Providing care as a professional duty

According to the participants’ experiences, despite a lack of facilities and personal protective equipment, there was a dominant sense of commitment among nurses to perform their professional duties in the COVID-19 pandemic. From the nurses’ point of view, working in difficult and dangerous conditions is part of a nurse’s job which must be maintained during the pandemic of an emerging disease.

“… anyway, it’s my job to give care in all circumstances and I had to do it at that time …” (P1).

According to another participant:

“…I volunteered to work in the COVID-19 ward … I thought to myself, ‘This is my job and my duty …” (P15).

Concern over transmitting the infection to one’s family

Despite their commitment to perform their professional duties, the nurses in the present study were worried about transmitting the infection to their families and their concern acted as a barrier to their stress management. The participants also mentioned that when their colleagues were infected, the fear of contracting the disease in the near future was a barrier to their stress management.

“… I was really worried that I could be the source of infection to my 60-year-old parents …” (P6).

Fear of the unknown aspects of the disease

One of the major barriers to stress management in the face of COVID-19 was lack of knowledge about the nature of the infection. Fear of the personnel arising from the unknown aspects of the disease was a main source of stress.

“… We didn’t know anything about it. The disease was completely unknown to us …” (P 3).

Concern over making wrong decisions

Some of the nurses were working in COVID-19 units voluntarily; however, they admitted that they had felt doubtful about their decision to provide voluntary care to COVID-19 patients in the first few days.

“… I kept wondering if my decision was right or not …” (P 4).

Another nurse stated that:

“…Maybe the decision I made was a step to fulfill my personal commitment …” (P 2).

Facing psychological and mental tension

Many of the nurses who were working in COVID-19 units declared that they had experienced a variety of psychological issues during their practice in these units which prevented them from managing their stress. This category consisted of the sub-categories of families’ insistence on quitting one’s job, working in difficult conditions, lack of personal protective equipment, and feeling rejected.

Families’ insistence on quitting one’s job

One of the sources of psychological tension for the nurses was the insistence of some of their family members that they should quit their profession as nurses during the pandemic.

“…My dad was strongly against me staying in this profession at those critical times …” (P 3).

Working in difficult conditions

Many of the participants described working in personal protective gear as very difficult. They also referred to work fatigue and physical exhaustion due to work overload as barriers to stress management.

“…When your shift is over, you can barely breathe; with a high PaCO2, it’s hard to breathe … it’s hard to eat in this coverall, you can’t drink any water through your shift … the fatigue …. Working in such conditions won’t let you manage stress…” (P 12).

According to another nurse:

“…Our workload has increased at these stressful times caused by the pandemic; my life and my family’s life have been affected … it’s not easy to work with all this protective gear on … Such things as fogging of my face shield interfered with my job … I was exhausted, both physically and emotionally…” (P16).

Lack of personal protective equipment

The participants stated that one of the major barriers to stress management was lack of personal protective equipment and coveralls, especially in the first few days of the pandemic. According to one of the nurses:

“…When the epidemic started, we didn’t have access to special gear for COVID-19 protection and had to care for the infected with minimum equipment, in regular masks and uniforms …” (P 5).

Feeling rejected

Another barrier to stress management in COVID-19 units was being treated inappropriately and rejected by the personnel in non-COVID-19 units. One of the participating nurses stated that:

“…When I got on the hospital shuttle, I felt so nervous. All the other staff that didn’t work in COVID-19 units would protest and tell the driver that he shouldn’t let me get on board … I should get off ….” (P 7).

Some of the participants had experienced rejection by their family members and relatives, which made it more difficult for them to manage stress.

“…Once, when one of my relatives saw me, she took her son’s hand and walked away from me …” (P 3).

Creating a context of support

In the present study, the participants believed that creating a context of support is an important stress management strategy in facing and caring for COVID-19 patients. This category consists of the subcategories of proper intradepartmental management, support of the authorities, and effective communication skills.

Proper intradepartmental management

The participants’ experiences showed that proper intradepartmental management, e.g. planning according to the personnel’s conditions, replacing COVID-19 personnel with volunteers, avoiding discrimination, playing soft music in the units, and using effective interpersonal communication skills, including empathy, humor and spreading positive thinking, can contribute to the personnel’s stress management. During the COVID-19 crisis, the unit managers tried to make plans according to the personnel’s conditions in order to reduce the personnel’s stress.

“…The husband of one of my staff here could spend two weeks a month with his wife …. I arranged her shifts so she didn’t have to work or worked less when her husband was with her so she wouldn’t be so worried about infecting her husband …” (P 1).

To reduce nurses’ direct contact with COVID-19 patients, the unit managers put the overstressed nurses in charge of recording patients’ history in their files in order to reduce stress in them.

“…One of my staff was stressed out …. I made her the shift supervisor so she would be busy with the patients’ files and have less direct contact with the patients …” (P 8).

Support of the authorities

In order to support the nurses by helping them manage their stress, the unit and hospital authorities arranged certain hours for the nurses to meet with the hospital counselor or for the counselor to see the nurses.

“…Whenever the personnel felt they were suffering from psychological tension and needed counseling, they could visit the hospital counselors ….” (P 11).

Another strategy used by the authorities to help the nurses manage their stress was setting up workshops to inform the nurses about the pathophysiology of COVID-19, how the infection is transmitted, the correct use of personal protective equipment, and regimens that boost the immune system. This information proved very influential in reducing stress in the nurses.

“…We didn’t have any preparation from before; education is really important; once we learned more about the disease, we could protect ourselves better …. We were less stressed …” (P 12).

According to the participants, continuing education was integral to enabling them to manage the stress caused by being in contact with COVID-19 patients. Even though the presence of the supervisors and the other members of the treatment team in the environment could communicate a sense of support and hope to the nurses, some of the supervisors refused to be present in the places where the patients were being cared for.

“…Our supervisor won’t even enter the unit to see for herself what kind of issues we are dealing with here …” (P 9).

Effective communication skills

The head nurses’ use of effective communication skills in their interactions with the staff was found to be a successful approach to stress management in those critical times. In addition, through empathy, the unit personnel tried to connect to their colleagues’ inner worlds and have a mutual understanding of their emotions and concerns, thereby coping with the stress caused by the COVID-19 crisis. The participants stated that in an empathetic relationship, they could experience a sense of support.

Showing appreciation and giving rewards were found to be effective stress management strategies which could raise the personnel’s spirits and improve interpersonal relationships. According to one of the participants:

“…One of the main issues for the nurses who are doing a good job in these units is not receiving any appreciation or rewards. There is a limit to any person’s tolerance. Some turn to spirituality for strength, but not everyone is spiritual. In short, there is a lack of appreciation …” (P 5).

Other behaviors which contributed to the nurses’ stress management were exchanging friendly banters with each other, spreading positive thinking, and remaining optimistic about the future.

Experiencing personal-professional growth

The participants referred to experiencing personal-professional growth as one of the outcomes of working in the very difficult conditions created by the spread of COVID-19. Caring for COVID-19 patients was a constructive experience which could prove instrumental in coping with problems in the future. Making an effort to use various stress management skills in the face of COVID-19 improved nurses’ empowerment and gave them a chance for personal growth. Compared to the time before the emergence of COVID-19, nurses can focus on their problems better and manage stress and stressors more effectively. This category consists of the subcategories of improved learning, perception of positive feelings at the end of a crisis, and self-transformation.

Improved learning

The participants believed that, despite all the difficulties, working during the pandemic had resulted in their gaining useful knowledge. Their experiences showed that providing care during the COVID-19 pandemic had helped them develop time management skills, learn to make optimal use of the available equipment and deal with deficiencies, improve their medication knowledge, increase their knowledge of emerging diseases, and learn to make effective use of infection control strategies.

“…I had read a few things about emerging diseases, but working in this pandemic has given me the chance to gain hands-on experience of caring for these patients …” (P 7).

Perception of positive feelings at the end of a crisis

While providing care to COVID-19 patients, the participants had experienced such positive feelings and emotions as elevated self-confidence, personal satisfaction, the opportunity to prove their competence, and the good feeling of overcoming the difficulties and challenges of caring for COVID-19 patients.

“…Working in these conditions created a positive sense of being useful to others in me … which made me feel happy and lively and physical fatigue could not take away my happiness …” (P 6).

Many of the participants mentioned feeling good about solving problems and happiness about serving one’s fellowmen to be among other outcomes of working in the COVID-19 crisis.