About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets and Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Webinars

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

The Venture Capital Initiative brings together faculty, staff, students, and practitioners to advance and promote research and teaching on innovation and venture capital.

Our goal is to advance understanding of venture capital and innovation ecosystem through conducting research, collecting high quality data, and developing teaching methodology. We aim to bring together leading academics and practitioners to help solve the problems that are highly relevant to entrepreneurs, financiers, policymakers, and researchers worldwide.

Stanford Financing of Innovation Summit

As the inaugural event of the Stanford GSB Venture Capital Initiative, the Stanford Financing of Innovation Summit, brought together leading researchers and practitioners to discuss the direction of research in the field of innovation and venture capital and to exchange ideas and share expertise.

Related Insights by Stanford Business

Inside the secret world of venture capital, how economic insecurity affects worker innovation, silicon valley’s unicorns are overvalued, do funders care more about your team, your idea, or your passion, how much does venture capital drive the u.s. economy, shai bernstein: does face time with investors make a startup more successful, past vci events.

As VCI’s inaugural event, the Stanford Financing of Innovation Summit brought together leading researchers and practitioners to discuss the direction of research in the field of innovation and venture capital and to exchange ideas and share expertise.

Download the Agenda

Download the Event Summary

Faculty Director

Ilya Strebulaev

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Class of 2024 Candidates

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Dean’s Remarks

- Keynote Address

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Marketing

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2024 Awardees

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Get Involved

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- Career Change

- Career Advancement

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Reading Materials

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- Join a Board

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- RKMA Market Research Handbook Series

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

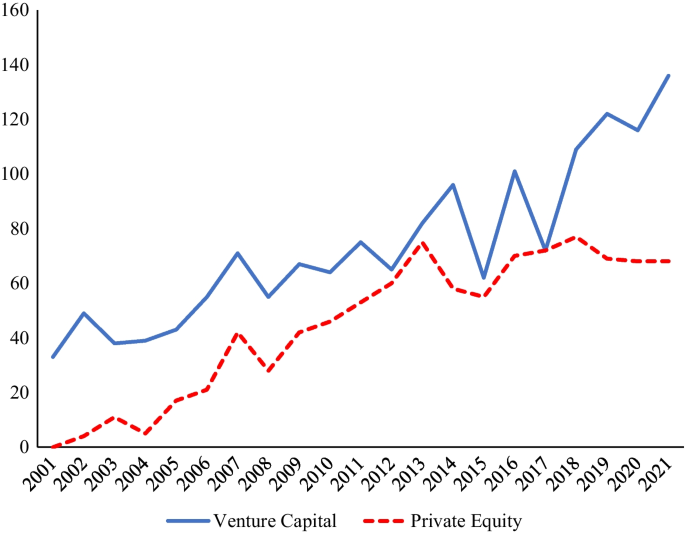

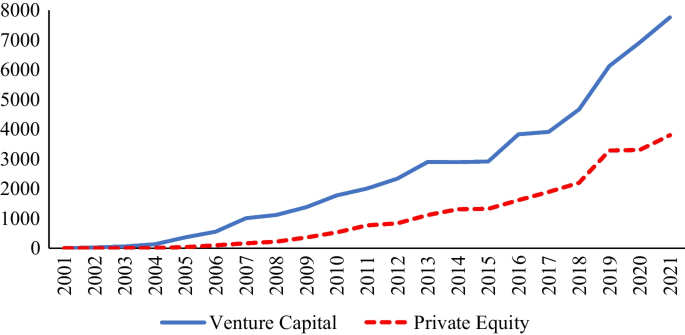

Venture Capital: A Catalyst for Innovation and Growth

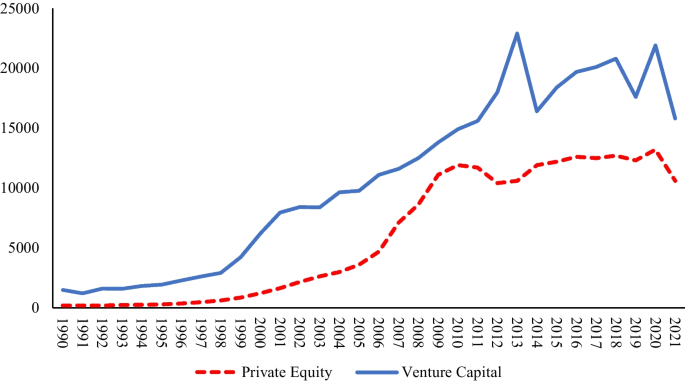

This article studies the development of the venture capital (VC) industry in the United States and assesses how VC financing affects firm innovation and growth. The results highlight the essential role of VC financing for U.S. innovation and growth and suggest that VC development in other countries could promote their economic growth.

Jeremy Greenwood is a professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania. Pengfei Han is an assistant professor of finance at Guanghua School of Management at Peking University. Juan M. Sánchez is a vice president and economist at the Federal Reserve Bank St. Louis. We thank Ana Maria Santacreu for helpful comments.

INTRODUCTION

Venture capital (VC) is a particular type of private equity that focuses on investing in young companies with high-growth potential. The companies and products and services VC helped develop are ubiquitous in our daily lives: the Apple iPhone, Google Search, Amazon, Facebook and Twitter, Starbucks, Uber, Tesla electric vehicles, Airbnb, Instacart, and the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. Although these companies operate in drastically different industries and with dramatically different business models, they share one common and crucial footprint in their corporate histories: All of them received major financing and mentorship support from VC investors in the early stages of their development.

This article outlines the history of VC and characterizes some stylized facts about VC's impact on innovation and growth. In particular, this article empirically evaluates the relationship between VC, firm growth, and innovation.

Read the full article .

Cite this article

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Stay current with brief essays, scholarly articles, data news, and other information about the economy from the Research Division of the St. Louis Fed.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE RESEARCH DIVISION NEWSLETTER

Research division.

- Legal and Privacy

One Federal Reserve Bank Plaza St. Louis, MO 63102

Information for Visitors

16 research papers every VC should know

Posted by Shaun Gold | October 10, 2022

Understanding venture capital is more than reading decks and tweaking your fund’s investment thesis. It requires an edge that comes from knowledge. Here are thirteen of the best research papers on VC to help you obtain that edge.

Table of Contents

1. many of the largest u.s. companies owe a vc.

VC powers the U.S. economy

Will Gornall (University of British Columbia (UBC) - Sauder School of Business) and Ilya A. Strebulaev (Stanford University - Graduate School of Business; National Bureau of Economic Research) showcase that Venture capital-backed companies account for 41% of total US market capitalization and 62% of US public companies’ R&D spending. Among public companies founded within the last fifty years, VC-backed companies account for half in number, three quarters by value, and more than 92% of R&D spending and patent value. This only transpired after the 1970s ERISA reforms. The paper further shows that US VC industry is causally responsible for the rise of one-fifth of the current largest 300 US public companies and that three-quarters of the largest US VC-backed companies would not have existed or achieved their current scale without an active VC industry.

2. Geographic Concentration of VC Investors in a Syndicate is Correlated to Deal Structure, Board Representation, Follow-On Rounds, and Exit Performance

Geographic concentration of venture capital investors, corporate monitoring, and firm performance.

A May 2019 Dartmouth paper by Jun-Koo Kang, Yingxiang Li, and Seungjoon Oh finds that compared to VC investors that are geographically dispersed, those that are geographically concentrated use less intensive staged financing and fewer convertible securities in their investments, are less likely to have board representation in their portfolio firms, and are more likely to form successive syndicates in follow-up rounds. Moreover, their firms experience a greater likelihood of successful exits, lower IPO underpricing, and higher IPO valuation.

3. VC firms that lack diversity perform 11%-30% lower on average

VC firms that lack diversity pay a higher cost

A 2017 paper from Paul A. Gompers and Sophie Q. Wang of Harvard documents the patterns of labor market participation by women and ethnic minorities in venture capital firms and as founders of venture capital-backed startups. If the partners of the VC firm are from the same school, the fund has a lower performance of 11%. If the partners have the same ethnicity, the fund has a lower performance of 30%. If the fund is all men, there is a 20% lower performance.

4. Venture Capital infusion harms non-VC backed industries in communities

The Silicon Valley Syndrome

A 2019 paper from Doris Kwon and Olav Sorenson of Yale University demonstrates that an infusion of venture capital in a region actually is more harmful than beneficial. The paper illustrates that VC infusion in a region is associated with declines in entrepreneurship, employment, and average incomes in other industries in the tradable sector while at the same time an increase in entrepreneurship and employment in the non-tradable sector and income equality overall in the region.

For example, the boom of Silicon Valley caused real estate prices in the Bay Area to rise which priced out low-salaried workers in the non technology sector. This caused other firms to lose talent to a handful of Silicon Valley technology companies. This is similar to the Netherlands in the 1960s after the discovery of natural gas which led to booming petroleum exports and the value of the Dutch currency to rise. Yet this also caused harm to other firms due to rising operating costs and to them losing workers to the natural gas extraction industry. The economy was left more vulnerable overall.This became known as “Dutch Disease.”

5. VC’s who’ve been fortunate to succeed once keep succeeding as initial success brings them quality deal flow

The persistent effect of initial success

A 2019 paper from Sampsa Samila (IESE Business School), Olav Sorenson (Yale), and Ramana Nanda (Harvard) illustrated that each additional initial public offering (IPO) among a VC firm’s first ten investments predicts as much as an 8% higher IPO rate on its subsequent investments, though this effect erodes with time. Successful outcomes result in large part from investing in the right places at the right times; VC firms do not persist in their ability to choose the right places and times to invest; but early success does lead to investing in later rounds and in larger syndicates. This pattern of results seems most consistent with the idea that initial success improves access to deal flow. That preferential access raises the quality of subsequent investments, perpetuating performance differences in initial investments. What does all this mean?

Get lucky once and everyone thinks you have the right stuff which results in more opportunities and quality deal flow.

6. Half of VC investments are predictably bad—based on information known at the time of investment

Predictably Bad Investments: Evidence from Venture Capitalists

Diag Davenport of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business argued in a 2022 paper that institutional investors fail to invest efficiently. By combining a novel dataset of over 16,000 startups (representing over $9 billion in investments) with machine learning methods to evaluate the decisions of early-stage investors, Davenport showed that approximately half of the investments were predictably bad. This was based on information known at the time of investment and that the predicted return of the investment was less than readily available outside options. Suggestive evidence also illustrated that an over-reliance on the founders’ background is one mechanism underlying these choices. The results suggest that high stakes and firm sophistication are not sufficient for efficient use of information in capital allocation decisions.

7. Getting funded by a reputable VC with a strong brand adds a lot of value

This paper by Darden pressor Ting Xu, Shai Bernstein of Harvard Business School, Kunal Mehta of AngelList LLC, and Richard Townsend of the University of California, San Diego analyzed a field experiment conducted on AngelList Talent. During the experiment, AngelList randomly informed job seekers of whether a startup was funded by a top-tier investor and/or was funded recently. Startups received more interest when information about top-tier investors was provided. Information that included the most recent funding amount had no effect. The effect of top-tier investors is not driven by low-quality candidates and is stronger for earlier-stage startups. Essentially, the potential employees cared about who funded it and not the amount. The results demonstrated that venture capitalists can add value passively, simply by attaching their names to startups.

8. VCs invest in the team rather than the product or technology

How do venture capitalists make decisions?

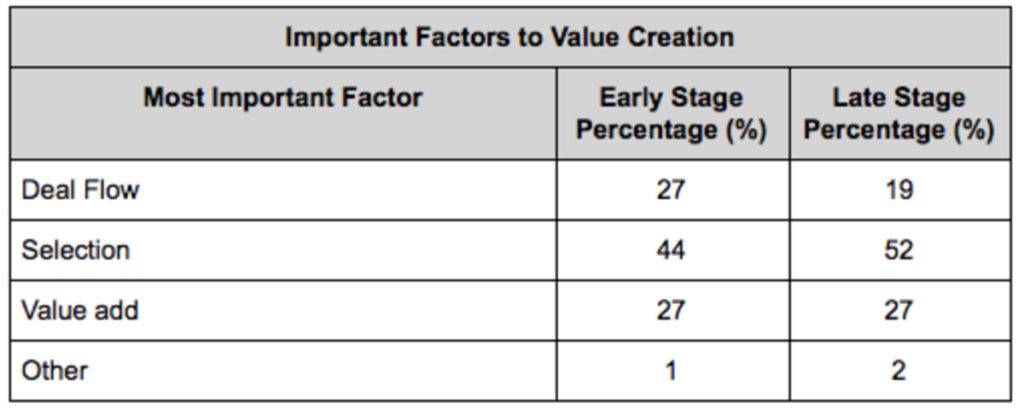

This paper was written by a rockstar team composed of Steven Kaplan, Neubauer Distinguished Service Professor of Entrepreneurship and Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and Kessenich E.P. Faculty Director of the Polsky Center, along with Paul Gompers at Harvard University Graduate School of Business; Will Gornall at the Sauder School of Business at the University of British Columbia; and Ilya Strebulaev at the Stanford University Graduate School of Business. They surveyed 885 institutional venture capitalists at 681 firms about practices in pre-investment screening, structuring investments, and post-investment monitoring and advising. The results showed that VCs see the management team as somewhat more important than business-related characteristics such as product or technology. VCs also view the team as more important than the business to the ultimate success or failure of their investments. The VCs rated deal selection as the most important factor contributing to value creation, more than deal sourcing or post-investment advising.

9. VC has real limitations in its ability to advance substantial technological change

Venture Capital’s Role in Financing Innovation: What We Know and How Much We Still Need to Learn

In this paper, Harvard professors Josh Lerner and Ramana Nanda argue that despite the growth VC brings into technology companies, there remain real limitations in regard to technological change. They are concerned about the very narrow band of technological innovations that fit the requirements of institutional venture capital investors; the relatively small number of venture capital investors who hold and shape the direction of a substantial fraction of capital that is deployed into financing radical technological change; and the relaxation in recent years of the intense emphasis on corporate governance by venture capital firms. They believe this may have ongoing and detrimental effects on the rate and direction of innovation in the broader economy.

10. More collaborative experience among VCs leads to M&A while less leads to an IPO

The Past Is Prologue? Venture-Capital Syndicates’ Collaborative Experience and Start-Up Exits

Dan Wang of Columbia, Emily Cox Pahnke of the University of Washington, and Rory McDonald of Harvard argue that as prior collaborative experience within a group of VCs increases, a jointly funded start-up is more likely to exit by acquisition (which they call a focused success); with less prior experience among the group of VCs, a jointly funded start-up is more likely to exit by initial public offering (which they term a broadcast success). This tested their hypotheses using data from Crunchbase on a sample of almost 11,000 U.S. start-ups backed by venture-capital (VC) firms, using the VCs’ previous collaborative experience to predict the type of success that the start-ups will experience.

11. Solo-founded startups are strongly associated with more rapid growth to unicorn status

In a paper by Greg Fisher, Suresh Kotha, and S. Joseph Chin, startups that have reached unicorn status are thoroughly examined. This is done through prior research on growth and valuation of unicorns as well as examining the dynamics to view the variations in which they reach a billion dollars in valuation. Ultimately, the paper demonstrates that the founder's age, gender, and affiliation with the Ivy League were not significantly related to the growth of unicorns. Furthermore, solo-founded startups are more associated with rapid growth to a unicorn valuation.

12. Warm introductions lead to 13x higher chance of funding

UK Venture Capital and Female Founders Report

Alice Hu Wagner, Calum Paterson, and Francesca Warner illustrate that startup decks that come in warm are far more likely to get funded. This rewards founders who have a great network and are connected but harms the multitude who lack these connections. If founders lack a network of investors, bankers, angels and other founders, fewer will be able to reach a proper VC.

13. Venture capitalists should stay in their lane

Venture capitalists are specialists.

Tyler J. Hull argues that VC performance is much better in the sub-industry they focus on rather than sub-industries where they have limited experience. And they underperform more the further outside their focus they go. Co-investing with another venture capitalist that has the same investment focus as the investment firm partially mitigates this effect. Additionally, the negative effect is shown to be more pronounced the greater the degree of difference between the venture capital’s preferred investment industry and the investment industry.

In other words, VCs should stay in their lane and make investments in their area of focus.

14. Data makes all the difference

Hatcher+ and need for data driven forecasting.

Hatcher+ is a globally diversified, multi-sector, early-stage technology investment fund founded in 2018. Based in Singapore, the managers use a combination of data science, modeling, workflow automation, and machine learning to execute a global venture investment strategy capable of unprecedented scale in terms of the number of investments. As a result, they produced a paper on venture capital transaction history to define and refine its approach to early stage investing. Via their own research, they discovered that data quality is actionable for a data-driven VC firm, accelerator rounds provide a strong opportunity for investment, deal flow is essential (especially for firms with large portfolios), large portfolios with follow on increases viability and adds round diversification, and that larger portfolios by investment count are key to early stage success.

15. Founders can become VCs but that doesn’t guarantee success

Success and failure as a founder plays a role if a founder becomes a VC

Paul A. Gompers & Vladimir Mukharlyamov explore whether or not the experience as a founder of a venture capital-backed startup influences the performance of founders who become venture capitalists. They discovered that almost 7% of VCs were previously founders of a venture-backed startup. Having a successful exit (an acquisition or IPO) as well as being male and white increased the probability that a founder transitioned into a career in VC. Successful founder-VCs have investment success rates that are 6.5 percentage points higher than professional VCs while unsuccessful founder-VCs have investment success rates that are 4 percentage points lower than professional VCs. The primary benefit of a founder-VC is not deal flow but the value add that they provide to their portfolio companies.

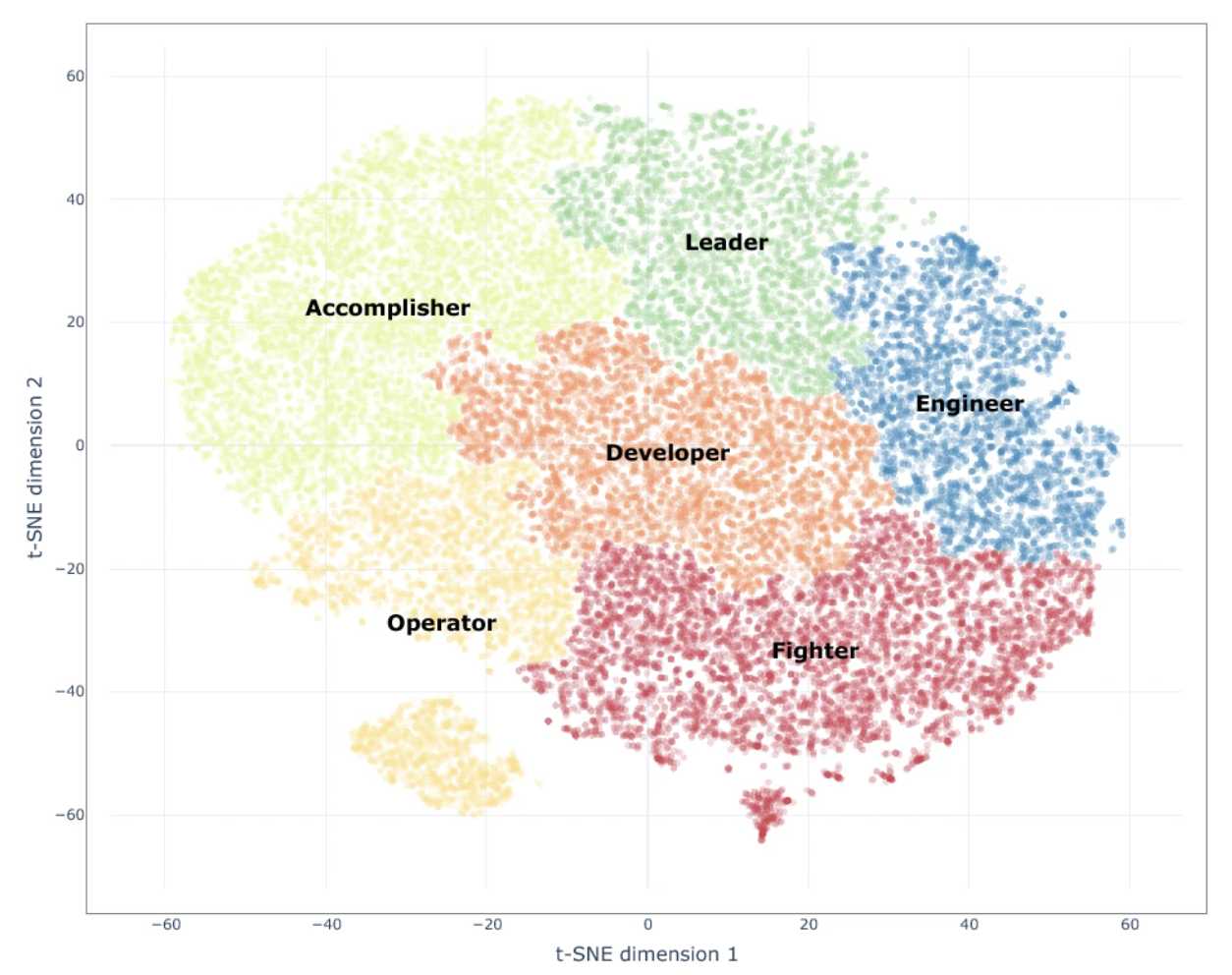

16. Successful founders have similar personality traits

The impact of founder personalities on startup success

Paul McCarty et alii. ran a large-scale study over 21,000 startups worldwide and found that personality traits of startup founders differ from that of the population at large. Successful entrepreneurs show high openness to adventure, like being the centre of attention, have higher activity levels. Six different personality types appear for founders: Accomplisher, Leader, Operator, Developer, Engineer, Fighter.

Venture capital is still a young industry and has more bragging rights than most realize. By effectively reading the research conducted by some of the leading academics at top universities, you can give yourself an edge and competitive advantage. This doesn’t cost but I promise you that it will pay.

Did we miss a great research paper that you think VCs should add to their arsenal of knowledge? Email me at [email protected] and I will add it.

OpenVC is a radically open platform that helps tech founders connect with the right investors.

POPULAR Posts

An LP take on VC portfolio construction

How to write a top 1% cold email to VCs

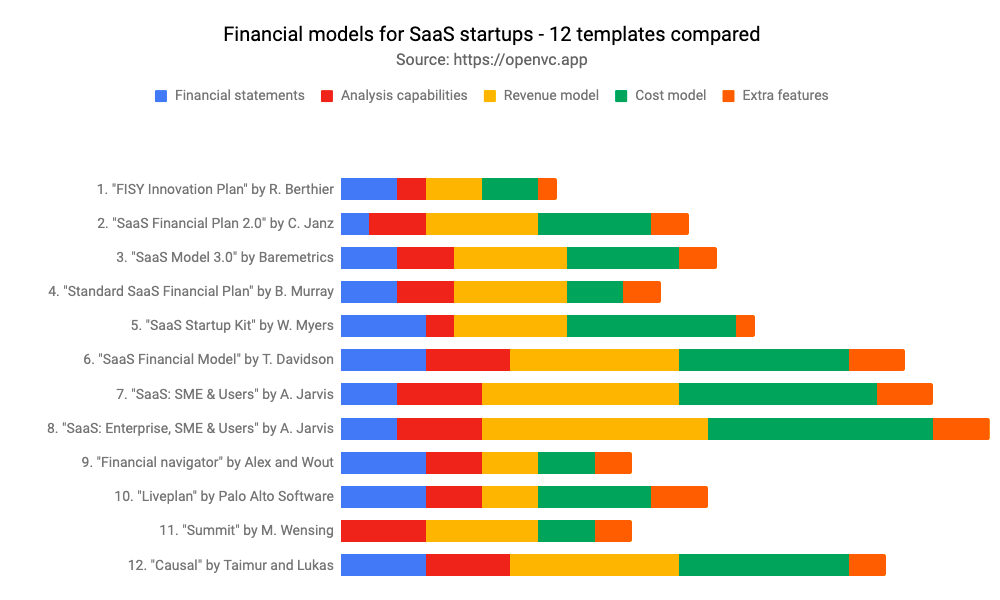

Pitch deck for startups - 9 templates compared

How to Model a Venture Capital Fund

How to whitelist OpenVC

Startup financial models - 12 templates compared

You might also enjoy

Why Seed Funding Is a Pool Party

You might think you’re fundraising, but what you’re actually doing is throwing a pool party. Venture funding dynamics in the Seed Phase have evolved differently than venture capital at Series A and beyond. A Seed fund would almost never take the whole round, even if it could.

Launching a VC fund? Why not a FAST instead?

With more funds in the market than ever, managers need to stay relevant and develop new models. Blockchain and Distributed Ledger Technology are coming to the forefront of the £10tn UK Asset Management industry. With that in mind, let me introduce you to FAST, a plug-and-play tokenized investment vehicle for hands-on syndicates and accelerators.

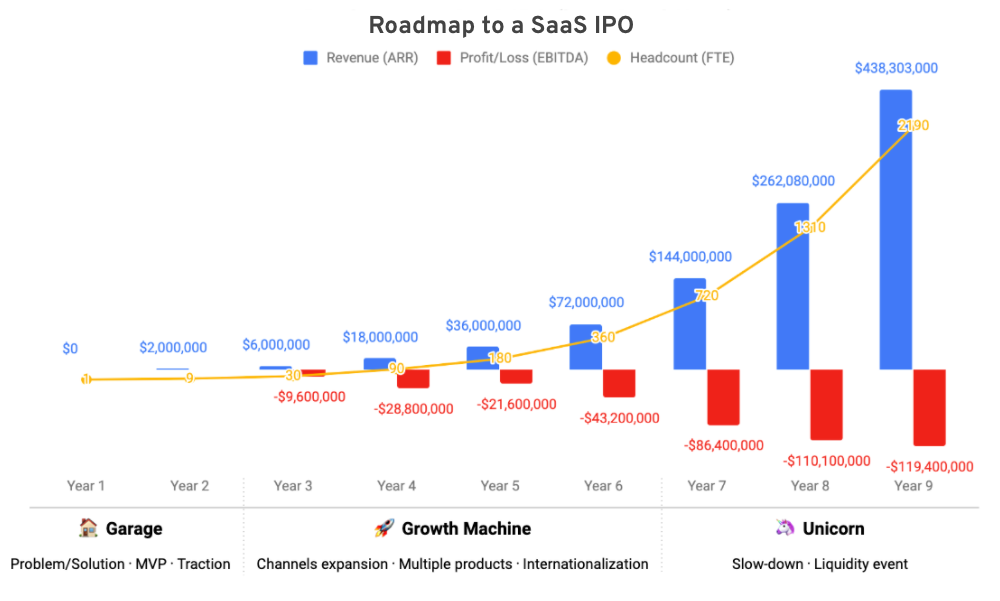

Roadmap to a SaaS IPO: how to unicorn your way to $100M revenue

Uncover 7 golden metrics leading to a SaaS IPO - timeframe, growth rate, EBITDA, funding, exit milestones, sales, and headcount.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Venture capital

- Entrepreneurial financing

- Entrepreneurship

- Finance and investing

- Investment management

Corporate Venturing

- Josh Lerner

- From the October 2013 Issue

Bootstrap Finance: The Art of Start-ups

- From the November–December 1992 Issue

The Era of “Move Fast and Break Things” Is Over

- Hemant Taneja

- January 22, 2019

There Are Only Two Types of Venture-Backed Companies

- Michael Fertik

- April 16, 2013

The Top Ten Lies of Entrepreneurs

- Guy Kawasaki

- From the January 2001 Issue

A Stealthier Way to Raise Money

- David Champion

- From the September–October 2000 Issue

Entrepreneurs Versus Executives at Socaba.com

- Regina Fazio Maruca

- From the July–August 2000 Issue

How the Market Ruined Twitter

- October 31, 2014

Why the U.S. Innovation Ecosystem Is Slowing Down

- Ashish Arora

- Sharon Belenzon

- Andrea Patacconi

- Jungkyu Suh

- November 26, 2019

What High-Quality Revenue Looks Like

- Anthony K. Tjan

- February 07, 2013

Does Silicon Valley Still Care About Climate Change?

- Walter Frick

- May 30, 2017

What African Fintech Startups Can Teach Silicon Valley About Longevity

- Glory Enyinnaya

- Olamitunji Dakare

- May 19, 2023

What Venture Trends Can Tell You

- William F. Meehan III, Ron Lemmens, and Matthew R. Cohler

- From the July 2003 Issue

Research: The Gender Gap in Startup Success Disappears When Women Fund Women

- Sahil Raina

- July 19, 2016

The Disruption of Venture Capital

- Eugene Chung and Maxwell Wessel

- January 26, 2012

The Other Diversity Dividend

- Paul Gompers

- Silpa Kovvali

- From the July–August 2018 Issue

Groupon Doomed by Too Much of a Good Thing

- Rob Wheeler

- August 16, 2011

Start-Up Capital Is Spreading Across the U.S.

- Ian Hathaway

- February 23, 2015

Venture Financing and Entrepreneurial Success

- William Kerr

- May 12, 2010

What Western Investors Want from African Entrepreneurs

- Ronald Klingebiel

- Christian Stadler

- November 11, 2014

Harambe: Mobilizing Capital in Africa

- Siko Sikochi

- Dilyana Karadzhova Botha

- Francesco Tronci

- September 24, 2021

Kleiner-Perkins and Genentech: When Venture Capital Met Science

- G. Felda Hardymon

- Tom Nicholas

- October 27, 2012

MAYA Capital

- Robert F. White

- Carla Larangeira

- Pedro Levindo

- September 09, 2021

Honest Jobs: A Path to Redemption

- Paul A. Gompers

- Jeffrey Barkas

- September 06, 2023

On the Bubble: Startup Bootstrapping

- Jeffrey J. Bussgang

- Annelena Lobb

- September 21, 2021

Statements of Cash Flows: Three Examples

- William J. Bruns Jr.

- Julie H. Hertenstein

- February 03, 1993

All Hands: A Tale of Two Term Sheets

- Robert Siegel

- Alessia Morales

- January 19, 2023

Dating Ring

- Thomas R. Eisenmann

- Lindsay N. Hyde

- January 04, 2022

Aspada: In Search of the Right Structure for Impact Investing

- Michael Chu

- Rachna Tahilyani

- April 01, 2014

A Close Shave at Squire

- Zoe B. Cullen

- William R. Kerr

- Benjamin N. Roth

- Michael Norris

- July 09, 2021

Barteca: The Challenge and Opportunity of Private Equity

- Lena G. Goldberg

- Michael S. Kaufman

- December 12, 2018

NextView Ventures

- Nori Gerardo Lietz

- August 19, 2020

Credible in India: Empowering Agri-business with Technology

- Jasper Lens

- Simon Shuster

- Willem Hulsink

- December 31, 2020

Pridebites: Roles and Decisions of Entrepreneurs and Investors

- Ludvig Levasseur

- Jacqueline Gomes

- June 01, 2022

Nuwa Capital: Investing During Uncertainty

- Fares Khrais

- February 08, 2024

Fusion Industry Association: Igniting the Future of Clean Energy

- Joshua Lev Krieger

- Jim Matheson

- Kyle R. Myers

- January 31, 2024

Y Combinator

- John R. Wells

- July 18, 2021

Venus Medtech: Global Innovation in the Race Between China and the U.S.A.

- Peter Ziebelman

- Joseph Golden

- February 01, 2020

Acumen Fund: Measurement in Impact Investing (A)

- Alnoor Ebrahim

- V. Kasturi Rangan

- September 16, 2009

Velasca: Organizing Growth

- Valeria Giacomin

- R. Daniel Wadhwani

- October 18, 2021

Popular Topics

Partner center.

- Consumer & Retail

- Enterprise Tech

- Financial Services

- Healthcare & Life Sciences

- Industrials

- Media & Entertainment

- Climate Tech

- Cybersecurity

- Quantum Tech

- Big Tech Reports

- Buyer Perspective Reports

- Competitor Analysis

- Future Of Reports

- Investment Thesis Maps

- Market Maps

- Market Prioritization

- State Of Reports

- Strategy Maps

- Top Company Lists

- The CB Insights Newsletter

- Upcoming Webinars

Join 500,000+ CB Insights newsletter readers

What Is Venture Capital?

- June 2, 2020

- Corporate Venture Capital

- Share What Is Venture Capital? on Facebook

- Share What Is Venture Capital? on Twitter

- Share What Is Venture Capital? on LinkedIn

- Share What Is Venture Capital? via Email

As a decade of growth in venture capital investment falters amid uncertain economic conditions, one thing remains constant: VCs will keep searching for companies that do business in a way that’s never been done before.

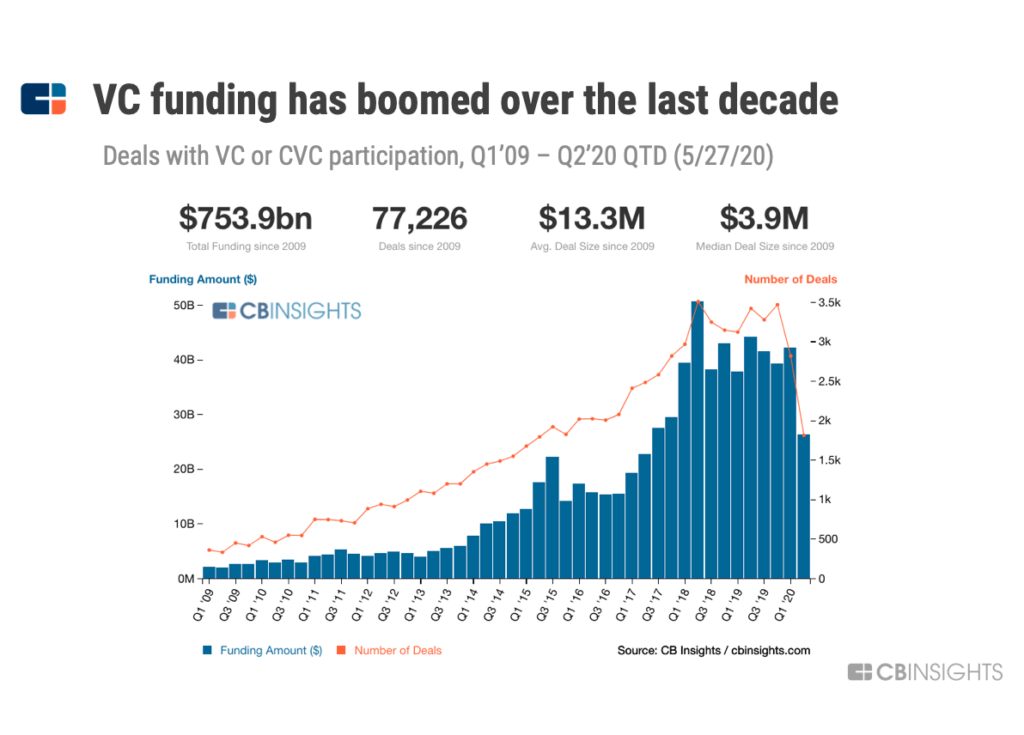

Venture capital has experienced a boom over the past decade.

Fueled by billion-dollar exits, the explosion of Silicon Valley startups, and massive raises from SoftBank’s $100B Vision Fund, annual capital invested worldwide increased by nearly 13x from 2010 to 2019 to reach over $160B . Meanwhile, mega-rounds (investments of $100M+) nearly tripled from 2016 to 2018.

However, the economic downturn brought on by Covid-19 has to some extent put the brakes on that growth. Fewer VCs are investing in seed-stage startups, and March 2020 saw a 22% year-over-year (YoY) decline in overall VC deals in the US.

It’s likely that VCs are being more selective in their investments, preferring more established companies that have proven themselves to be strong enough to weather the pandemic and grow when the economy ramps back up.

But venture capital is in many ways resistant to short-term changes, due to the simple fact that venture investments are long-term. VCs aren’t necessarily looking to invest in startups that will see huge growth in the immediate future; they are looking for ones that will grow into something extraordinary 10 years from now.

Overall, the fundamentals of venture capital haven’t changed. VCs place their bets on startups poised to jump-start a fundamental change in consumer or business behavior — and this fact is no different now than it was when the industry began.

In this report, we explore the foundations of venture capital by diving into its key terms and definitions, the motivations and thought processes of VCs, and what VCs — and startups — look for at each investment stage.

Table of contents

What is venture capital, a game of home runs, why startups seek vc funding.

The VC food chain

Who are LPs?

Vcs to startups, the venture deal, tips and sources, inbound deals, market size, founding team, pro rata rights, liquidation preference, the venture capital financing cycle: seed to exit.

Venture capital is a financing tool for companies and an investment vehicle for institutional investors and wealthy individuals. In other words, it’s a way for companies to receive money in the short term and for investors to grow wealth in the long term.

VC firms raise capital from investors to create venture funds, which are used to buy equity in early- or late-stage companies, depending on the firm’s specialization (although some VCs are stage-agnostic). These investments are locked in until a liquidity event, such as when the company is acquired or goes public, at which point VCs realize profits from their initial investment.

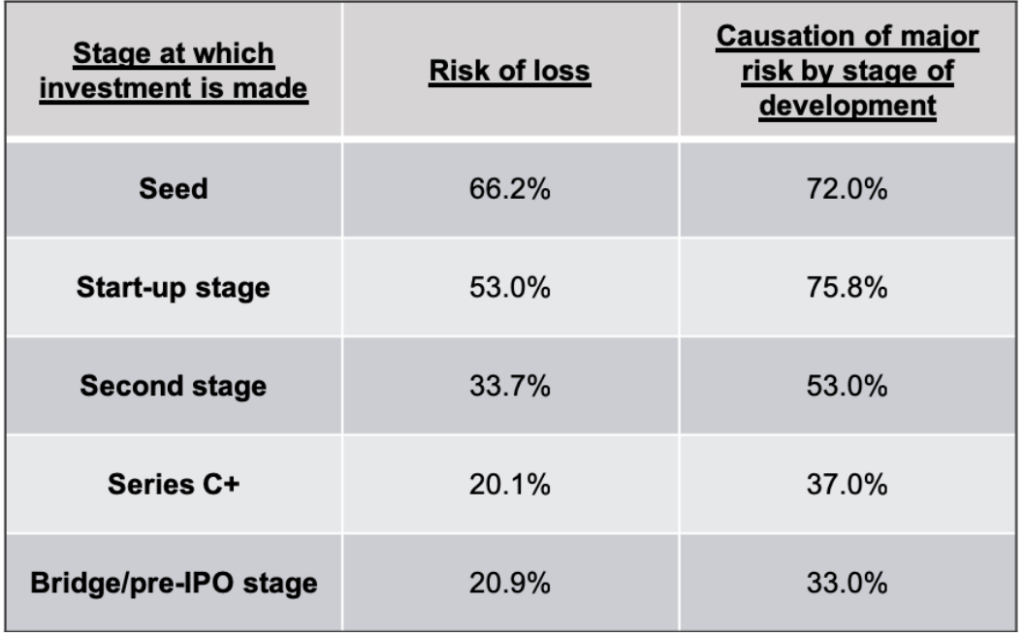

Venture capital is characterized by high risk, but also high reward. On the one hand, VCs must invest in emerging technologies and products that have massive potential to scale, but aren’t profitable yet — and over two-thirds of VC-backed startups fail . At the same time, VC investments can prove to be enormously profitable, depending on how successful a portfolio startup is.

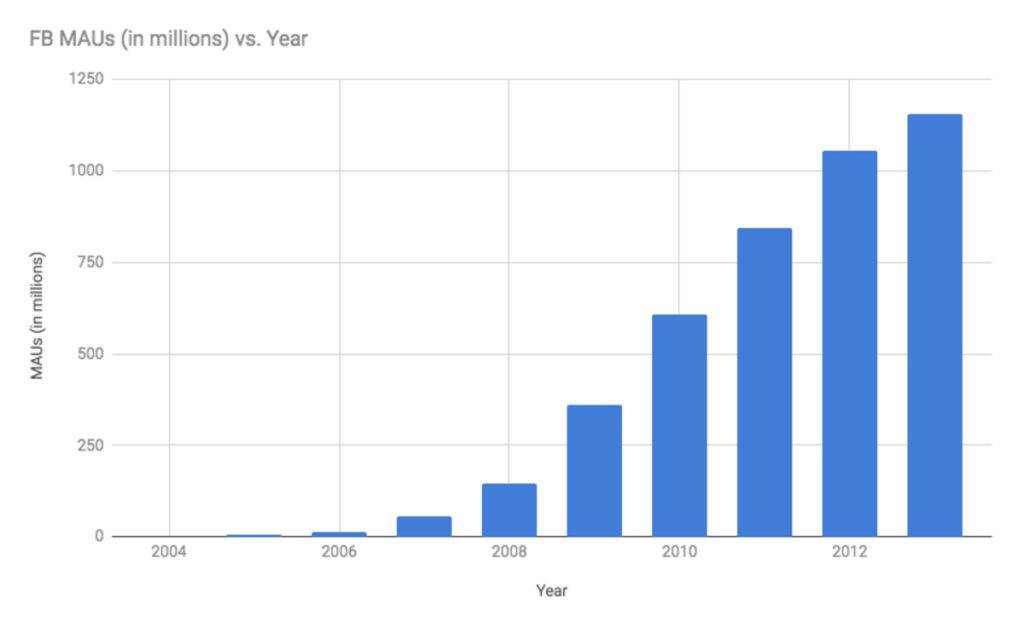

For example, in 2005, Accel Partners invested $12.7M in Facebook for a ~10% equity stake. The firm sold a part of its shares in 2010 for around half a billion dollars, and went on to make over $9B when the company went public in 2012.

Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, and Accel Partners partner Jim Breyer. Source: Jim Breyer via Medium

Another important characteristic of venture capital is that most investments are long-term. Startups often take 5 to 10 years to mature, and any money invested in a startup is difficult to pull out until the startup is robust enough to attract buyers in the mergers & acquisitions, secondary, or public markets. Venture funds have a 10-year lifetime, so VCs can see through these investments without the pressure to demonstrate short-term gains.

On the company side of VC transactions, venture capital allows startups to finance their operations without taking on the burden of debt. Because startups pay for venture capital in the form of shares, they don’t have to incur debt on their balance sheets or pay the money back. For startups looking to grow quickly, venture capital is an attractive financing option, potentially allowing startups to outpace the competition as they take in more investments at each growth stage.

Startups also take on venture capital to tap into VCs’ expertise, networks, and resources. VCs often have a wide network of investors and talent in the markets they operate in, as well as years of experience overseeing the growth of many startups. The mentorship VCs can bring is especially valuable for first-time founders.

Today, venture capital is most active in the B2C software, B2B software, life sciences, and direct-to-consumer (D2C) industries. The software industry is fertile grounds for VC investment because of its low up-front costs and huge addressable market. Companies like Google , Twitter , and Slack have risen to dominance thanks in part to venture financing.

The life sciences sector, while a more capital-intensive area for companies to start out in, also offers a giant addressable market and technological and regulatory moats to protect against competition. The sector is also attracting increased attention during the coronavirus pandemic.

The D2C industry has also been a large focus for VC funding, with companies like Warby Parker delivering affordable, well-made products at scale through online channels.

Until 1964, Babe Ruth held the record for the most career strikeouts, at 1,330. Despite that, he also hit 714 home runs in his career, giving him the highest slugging percentage of all time. When Babe Ruth went to bat, he swung for the fences.

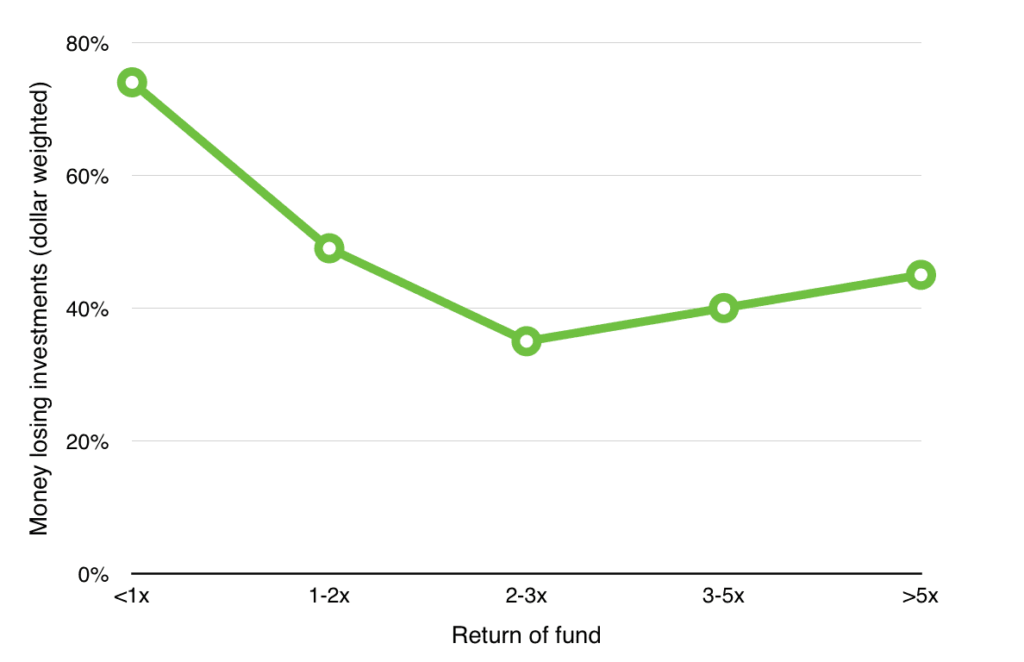

VCs espouse a similar strategy. By taking stakes in companies that have a small chance of becoming enormous, they make investments that tend to be either home runs or strikeouts. Chris Dixon, a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz , calls this the Babe Ruth Effect.

According to Dixon, great funds with a 5x or greater return rate tend to have more failed investments than good funds with 2-3x returns. In other words, great VCs are bigger risk-takers than good VCs: They make fewer bets on “safe” startups that do fairly well, and more bets on startups that will either flop or transform the industry.

Source: Chris Dixon

These great funds also have more home-run investments (investments that return more than 10x) and even home runs of greater magnitude (returning around 70x).

This is why Peter Thiel, an early investor in Facebook, looks for companies that create new technology, rather than companies that replicate something that already exists. He observes that these new technologies enable “vertical progress,” where something is transformed from “0 to 1.”

He cautions against “horizontal” or “1 to n” progress: taking an existing technology and spreading it elsewhere, such as by recreating a service in a new geographic location.

That said, many VCs do ride on trends and invest in incremental companies. One reason for this is that the reputational cost of failing on a contrarian bet is high: If a fund flops, its investors might be more forgiving of investments that were widely thought to be the next big thing.

Generally speaking, bankers do not lend to startups the way they may offer traditional loans to other businesses (e.g. agreements where the borrower agrees to pay back a principal, plus a set level of interest).

Banks rely on financial models, income statements, and balance sheets to determine whether a business qualifies for a loan — documents that aren’t as useful when gauging an early-stage startup’s value. Furthermore, in the early stages, there is hardly anything for banks to hedge as collateral. Whereas an established company may have factories, equipment, and patents, which a bank could take in the event of a foreclosure, a software startup might leave behind a few laptops and office chairs.

VC firms are better attuned to evaluating early-stage startups, using metrics that go beyond financial statements — such as product, market-size estimates, and the startup’s founding team.

These tools are by no means perfect, and most investments will lose their value. However, because equity returns are uncapped, the high risk of investing in startups can be justified. While debts are structured so that a lender can only recuperate the principal and a set amount of interest, equity-based financing is structured so that there is no upper limit to how much an investor can earn.

Broadly, the equity financing model has served the startup ecosystem well. Startups can accelerate growth without slowing down to pay down debt, as they would with a traditional business loan, and VCs can capitalize on the rapid growth of startups upon their exits.

However, giving out equity in exchange does carry two main liabilities for companies: loss of upside and loss of control.

Because equity is partial ownership of the company, investors are paid a percentage share of the total price of the acquisition or IPO when the company exits. The more equity a startup gives out, the less is left for founders and employees. And if the company grows extremely valuable, the founding members may end up missing out on a much greater amount than what they would have paid if they had taken on regular debt financing, rather than equity funding.

Giving out equity can also mean ceding control. VCs become shareholders, often sitting as board members. They may apply pressure to important business decisions, from when products launch to how the company exits. Because VCs need big exits to boost their overall fund performance, they may even urge decisions that lower the chance of moderate success, while increasing the odds that the startup, if successful, returns 100x.

Get the full report On Venture capital here

The venture capital food chain.

VCs raise their money from limited partners (LPs), institutional investors who serve the interests of their client organizations.

The interests and incentives of LPs greatly influence VCs’ investment strategies. This section will examine the flow of influence and relationships across the chain, from the LPs’ institutions to the VC-backed startups.

LPs are typically large institutional investors, such as university endowments, pension funds, insurance companies, and nonprofit foundations. (Some LPs are wealthy individuals and family offices.) They can manage up to tens of billions of dollars, which they invest in diversified portfolios.

An LP’s portfolio must serve the needs of the institution by growing its asset base year-over-year, while also funding expenses of the institution.

For example, Harvard’s endowment funds a large portion of the school’s annual operation. If its $40B+ endowment grows at 5% annually, but the university’s expenses on average cost 6% of the endowment, the asset base will shrink by 1% every year. A weakening endowment can endanger the institution’s standing and hamper its ability to hire the best professors, attract top students, and fund leading research.

Similarly, pension funds are responsible for funding pensioners’ retirements; insurance company reserves are responsible for payouts; and nonprofit foundation reserves are responsible for financing their organizations’ grants.

As LPs manage risk and grow their asset base at a sustainable rate, venture capital’s role in their portfolio is to (hopefully) produce the investment’s alpha — excess returns relative to a benchmark index.

LPs invest in venture capital by pledging a certain amount in VC funds. The size of these funds can range from $50M to, in some cases, billions.

Over the past few years, greater influxes of capital into VC firms have led to the rise of $1B+ mega-funds and an increased number of sub-$100M micro-funds.

In 2018, for example, Sequoia Capital raised $8B for its Global Growth Fund III, $1.5B of which it has dispersed in 15 growth-stage startups (as of January 2020). The fund’s largest investment so far was $384M to China-based Bytedance , the TikTok parent company.

On the other end of the spectrum, Catapult Ventures raised a $55M fund in 2019 that targets seed-stage startups specializing in AI, automation, and internet of things (IoT). In April 2020, the firm participated in a $3.3M seed round for Strella Biotechnology , a company that optimizes supply chains for fresh produce.

VCs raise capital from LPs by pitching their track record, projections into the fund’s performance, and hypotheses on promising areas of growth.

Fundraising can take a long time, so VCs will often do a “first close” after hitting 25-50% of the target amount and then start investing those funds before the final close.

Most funds have a 2-20 structure: 2% management fee and 20% carry. The 2% fee covers the firm’s operating expenses — employee salaries, rent, day-to-day operations.

The “carry,” meanwhile, is the essence of VC compensation — VCs take 20% of the profit their funds make. While investing in a potential Google or Facebook can generate more than enough profit to go around for both VCs and their LPs, a 20% carry can become a pain point for LPs when a VC delivers thin margins.

In return for high fees, high risk, and long-term illiquidity, LPs expect VCs to deliver market-beating returns. Generally speaking, they expect VCs to return 500 to 800 basis points higher than the index. For example, if the S&P 500 returned 7% annually, LPs would expect venture capital to return at least 12%.

The higher a VCs’ returns, the more prestige the firm gains. Some of the most well-known funds include:

- Andreessen Horowitz’s Andreessen Fund I, which performed in the top 5% of funds raised in 2009, with a 2.6x return on investment (ROI)

- Sequoia Capital’s 2003 and 2006 funds, which brought 8x in returns, net of fees

- Benchmark ’s 2011 fund, which carried 11x in returns, net of fees

If VCs fail to deliver market-beating returns or even lose LPs’ money, their reputation takes a hit, making it difficult to raise new funds to cover expenses. To stay in business, VCs need to invest in high-performing startups that yield returns that will keep their LPs happy, while still leaving the fund with a generous carry to take home.

For VC funds to yield market-beating rates of returns, VCs need companies that return 10 to 100 times their investment.

Because 67% of VC-backed startups fail , and there is only a slim chance — at most 1.28% — of a billion-dollar company being created, VCs need startups that return astronomically to make up for the inevitable failures.

A closer look at how VC returns are distributed demonstrates how extremely disproportionate investment performance is across VC-backed startups.

VC returns follow a power-law curve: one quantity varies with the power of another. This means the highest performer has exponentially greater returns compared to the second highest, and so on.

As a result, distribution is heavily skewed, with a few top investments bringing in the lion’s share of the returns. (The rest, called the “long tail,” generate only a fraction.)

The cost of missing an investment at the high-return end is enormous, while netting one has the potential to return the fund many times over, even if the rest of the portfolio flounders.

What keeps VCs up at night isn’t the portfolio companies that go bust — it’s the wildly successful ones that got away.

The VC industry as a whole follows the power-law curve, just as VC investments do.

In other words, funds managed by a few elite firms generate most of the wealth, and the long tail is littered with funds that don’t make the industry average rate of return.

Top investment opportunities are scarce. While there may be more financing rounds, there is only one Facebook Series A round. Once that window closes, it’s closed for good: There’s no way to invest under the same terms and conditions.

VCs compete with one another to get a seat at the table in these highly sought-out rounds, where the lead investor is usually an elite firm, such as Sequoia Capital, Accel Partners, or Kleiner Perkins .

Because of the Babe Ruth Effect, closing the right deal is the most important activity a VC does. In a survey of nearly 900 early- and late-stage VCs, deal flow and selection together were reported to make up about 71% of the value VCs create.

Source: Antoine Buteau via Medium

No amount of mentorship or cash can transform a mediocre company into the next Google. That’s why VCs spend the bulk of their time and effort gaining access to the best deals, evaluating and selecting their investments, and hammering out the details in the term sheet (more on this below).

How VCs source deals

Steady access to high-quality deals is crucial for a VC to succeed. Without healthy deal flow, a VC can miss out on high-profile investment rounds and fail to discover high-potential startups in their infancy. Each time a VC fails in this regard, its fund is at risk of underperforming against the competition.

Therefore, VCs will go to great lengths to improve the quality of their deal flow. Successful VCs have a strong network that helps them capture investment opportunities, as well as a strong brand that generates a steady stream of inbound deals.

A rich and diverse network is often a VC’s best source of deals. VCs rely on their network to connect to promising founders whose startups fit the investment thesis.

Firstly, VCs network with one another by investing jointly in companies, sitting on boards together, and attending industry events. VCs will often invite others in their network to investment rounds or refer startups that aren’t a match to their firm.

VC firms also rely on a professional network of entrepreneurs, investment bankers, M&A lawyers, LPs, and others they’ve worked with in growing and selling startups.

Accelerators — which offer a kind of entrepreneurship boot camp for founders — also maintain close relationships with VCs, often becoming joint investors. In 2009, Paul Graham of accelerator Y Combinator tried to loop Fred Wilson of Union Square Ventures into investing with him in Airbnb — and Wilson famously declined.

Lastly, MBA programs and university entrepreneurship centers are also good deal sources for VCs. One example is DoorDash , which started as a Stanford Business School project, and went on to raise more than $2B of capital and be valued at nearly $13B.

If there isn’t a good bridge in their network to connect with a promising startup, however, VCs will resort to the tried-and-true method of cold emails to express interest in partnering.

Building a robust network isn’t enough for a VC to gain maximum exposure to the highest-quality deals. Given the scarcity of unicorn startups and the intensity of competition, VCs need to build a strong brand to improve the flow of inbound deals.

There are largely two ways in which VCs differentiate their brand and offerings: thought leadership marketing and “value-add” services.

By becoming thought leaders, VCs attract a community of entrepreneurs and other investors that look to them for expertise and authority. VCs build their platforms by writing, blogging, tweeting, and speaking publicly at various events.

First Round Capital publishes long-form articles on leadership, management, and teamwork for early-stage entrepreneurs. Fred Wilson of Union Square Ventures has run a daily blog since 2003 where he shares various behind-the-scenes insights into the industry. Bedrock Capital brands itself as a firm that discovers “narrative violations” — companies challenging a commonly accepted narrative.

Pairing thought leadership expertise with an enticing “value-add” service can be a powerful way to lure top startups. VCs add value to their portfolio companies beyond just offering capital; they deliver mentorship, network, and technical support.

Andreessen Horowitz provides its companies with a full-stack marketing and accounting service. GV , the VC arm of Alphabet , has an operations team dedicated to helping startups with product design and marketing. First Round Capital holds leadership conferences and mentorship programs specifically geared toward early-stage founders, offering a community of relationships beyond just the firm itself.

How VCs select investments

Evaluating a startup presents a unique challenge. Often, there aren’t comparable businesses, accurate market-size estimates, or predictable models. As a result, VCs rely on a mix of intuition and data to assess whether the startup is worth investing in and how much it should be valued at.

VCs chase after opportunities with a large total addressable market (TAM). If the TAM is small, there is a limit to the returns the VC can reap when the company exits — which is no good for VCs that need companies exiting at 10-100x in order to be recognized as one of the elites.

But VCs don’t just want to invest in companies situated within large addressable markets from the get-go. They also want to bet on companies that grow their addressable markets over time.

Uber’s TAM grew 70x over 10 years, from a $4B black-car market to a near $300B cab and car ownership market. As the product matured, its cheaper, more convenient service converted customers , starting a network effect in which costs decreased as ride availability increased.

Bill Gurley, general partner at Benchmark (which has invested in Uber), sees the company eventually taking on the entire auto market, as ride hailing becomes preferable to owning a car.

Another example is Airbnb, which started in 2009 as a couch-surfing website for college students. At the time, its own pitch deck told investors that there were only 630,000 global listings on couchsurfing.com. But by 2017, Airbnb had 4M listings — more rooms than the 5 biggest hotel groups combined. Its TAM had grown with it.

It’s challenging to predict the magnitude of the impact a product will have on its market. According to Scott Kupor, managing partner at Andreessen Horowitz and author of “Secrets of Sand Hill Road,” VCs must be able to “think creatively about the role of technology in developing new markets” to seize great investments, rather than take TAM at face value.

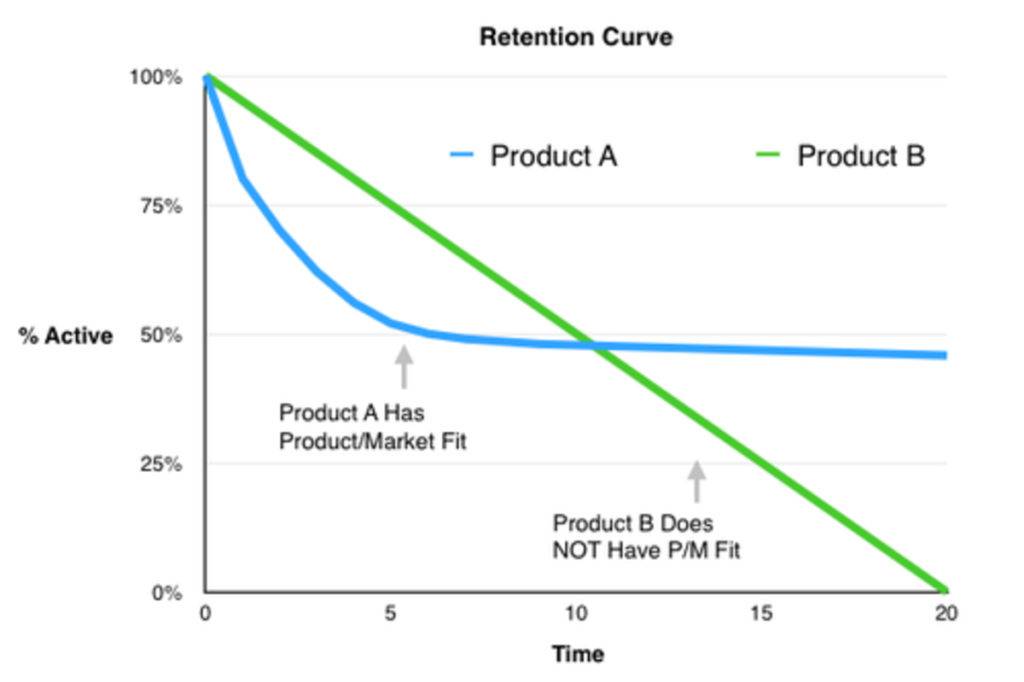

Another key consideration is product-market fit, a nebulous idea that refers to the point when a product sufficiently meets a need in a market, such that adoption grows quickly, while churn remains low. The majority of startups fail because they don’t find product-market fit, which is why many venture capitalists hold that it is the most important goal for an early-stage company.

There isn’t a particular point at which product-market fit occurs; rather, it happens through a gradual process that could take from several months to several years. Neither is it permanent once it’s reached: Customer expectations are constantly changing, and products that once had strong product-market fit can fall out of it without proper adjustments.

It’s also important to understand that product-market fit doesn’t equate to growth. A spike in usage driven by early adopters may look impressive on a dashboard, but if the numbers drop off in a few weeks, it’s not a good indicator of product-market fit.

Founders have gone to extreme lengths to nail product-market fit, from Stewart Butterfield scrapping his mobile game company before arriving at Slack to Tobias Lütke using his online snowboarding shop’s infrastructure to build the e-commerce platform Shopify .

These startups succeeded in scaling exponentially because they were able to reach product-market fit before ramping up sales and marketing. (What is dangerous is scaling prematurely before hitting product-market fit, as about 70% of startups do, according to Startup Genome.)

Product-market fit can be difficult to measure because a product could be anywhere from a few iterations to a significant pivot away from achieving it. However, there are a few quantitative benchmarks that can show a startup’s progress.

A high Net Promoter Score (NPS), for instance, shows that customers not only recognize the value of the product, but are willing to go out of their way to recommend it to other people.

Similarly, for angel investor Sean Ellis, product-market fit can be reduced to the question, “How would you feel if you could no longer use [the product]?” The users who respond “Very disappointed” make up the market for that product.

Another simple framework looks for strong top-line growth accompanied by high retention and meaningful usage.

Source: Brian Balfour

Strong product-market fit is a compelling sign that a startup will become successful. VCs look for startups that have already achieved it or have a concrete road map toward it. By the Series A stage, a startup generally needs to show investors that it has achieved or made visible progress toward product-market fit.

At the seed stage, a startup is nothing more than a pitch deck. Josh Kopelman of First Round Capital says that, at the seed stage, it’s likely that a startup’s product is wrong, its strategy is off, its team is incomplete, or it hasn’t built the technology. In those cases, what he bets on is not the startup idea, but the founder.

When a VC invests in a startup, the VC is wagering that the company will become what Scott Kupor calls the “de facto winner in the space.” VCs must therefore prudently decide whether a founding team is the best team to tackle this market problem over any others that may come to them for funding at a later time.

VCs look for founders with strong problem-solving skills. They ask questions to get a glimpse of how the founder thinks through certain problems. They get a sense of whether the founder has the flexibility to navigate through challenges, adapt to changes in the market, and even pivot the product when necessary.

They also look for founders that have a coherent connection to the space they’re looking to disrupt. Chris Dixon says that he looks at whether founders have industry, cultural, or academic knowledge that led them to their idea.

Emily Weiss, founder of Glossier , worked in fashion before launching the DTC beauty company. Airbnb’s founders understood the culture of a generation willing to share homes and experiences. Konstantin Guericke, co-founder of LinkedIn , studied software engineering at Stanford before arriving at the idea that professional networking could be done online.

VCs also favor founders who have previously founded unicorn startups. These founders have the experience of taking a company from zero dollars in revenue to billions, and they understand what it takes to transition the company at each level. They also have media coverage and a robust network — all contributing to recruiting talent and attracting resources.

For example, a group of early PayPal employees, called the PayPal Mafia, went on to start a number of highly successful startups, including Yelp , Palantir , LinkedIn, and Tesla . Other startup “mafias” — made up of early employees-turned-founders — continue to branch off from mature startups like Uber and Airbnb, in turn attracting additional VC attention and funding.

The term sheet

The term sheet is a nonbinding agreement between VCs and startups about the conditions of investing in the company. It covers a number of provisions, the most important being valuation, pro rata rights, and liquidation preference.

The valuation of the startup determines how much equity investors will own from a certain amount of investment. If a startup is valued at $100M, a $10M round of investment will give the investors 10% of the company.

$100M would be the pre-money valuation of the company — how much the company is worth before the investment — and $110M would be the post-money valuation.

A higher valuation allows the founder to sell less of the company for the same amount of money. Existing shareholders — founders, employees, and any previous investors — experience less share dilution, which means greater compensation when the company is eventually sold. Selling less of the company in a given investment round also means the founder can raise more money down the line while keeping the level of dilution in check.

However, a high valuation comes with high expectations and pressure from investors. Founders who have pushed investors to the brink of what they’re comfortable paying will have little room for mistakes. Each round generally needs to yield at least double the valuation of the previous one, so a high valuation will also be harder to overshoot.

Another downside to a high valuation is that investors may veto moderate exits because their stake in the company requires a bigger exit to be worthwhile. Investors may not allow a company with a valuation over $100M to exit for anything less than $300M, while they might be okay with a lower-valued company being acquired for a more moderate sum.

Pro rata rights give an investor the ability to participate in future financing rounds and secure the amount of equity they own.

If earlier VCs don’t follow on in their investments, their shares get progressively diluted with each financing round. If they owned 10% of the company upon investment, they will lose 10% of that initial ownership each time the startup offers up 10% to new investors.

Exercising previously secured pro rata rights can become a source of tension between early VCs that want to pitch in and protect against share dilution and downstream VCs who want to buy as much of the company as possible.

The liquidation preference in a financing contract is a clause that determines who gets how much in the event that a company liquidates.

VCs, the preferred shareholders, are prioritized in the event of a payout.

A 1x multiple guarantees the investor will be paid at least the investment principal before others are paid out. The seniority structure determines the order in which preferences are paid. “Pari passu” seniority pays all preferred shareholders at the same time, while standard seniority honors preferences in reverse order, starting with the most recent investor.

As rounds get bigger and more investors get involved, a company should pay attention to managing its liquidation stack so that investors aren’t disproportionately rewarded in a payout without leaving much behind for founders and employees.

The average VC-backed startup goes through multiple rounds of funding in its lifetime.

At the initial or seed stage, most of the capital is allocated to developing the minimum viable product (MVP). Angel investors and the founder’s friends and family often play a big role in funding the startup at the seed stage.

At the early stages, capital is used for growth: developing the product, discovering new business channels, finding customer segments, and expanding into new markets.

At the later stages, the startup continues to scale revenue growth, although it may not yet be profitable. Funding is generally used to expand internationally, acquire competitors, or prepare for an IPO.

In the final stage of the cycle, the company exits through a public offering or an M&A transaction, and shareholders have the opportunity to realize gains from their equity ownership.

Seed- to early-stage investments are inherently more risky than late-stage investments, because startups at these stages don’t yet have a commercially scalable product in place. At the same time, these earlier investments also generate higher returns, as early-stage startups with low valuations have much more room to grow.

Later-stage investments tend to be safer because startups at this stage are usually more established. This isn’t necessarily true in every case: Some technologies take longer to mature, and late-stage investors may still be betting on them to hit mass-market adoption.

Not all companies proceed down this funnel. Some founders choose not to raise further rounds of venture capital, instead financing the startup with debt, cash flow, or savings.

Two big reasons founders choose to “bootstrap” are to maintain ownership of the company’s direction and build at a sustainable pace. Because venture capital comes with investor expectations that the company will grow rapidly month-to-month, VC-backed startups can fall into the trap of burning cash for more customers.

This short-term pressure to produce can lead startups to lose sight of their long-term creative vision. Recognizing this setback, founders of the video-sharing platform Wistia , for one, chose to take on debt instead, writing in a blog post that they “felt confident that the profitability constraints the debt imposed would be healthy for the business.”

On the flip side, Facebook is an example of a company that has successfully scaled through various stages of the venture capital cycle. The startup’s trajectory culminated in a $16B IPO at a $104B valuation, making it one of the most successful VC-backed exits of all time.

To some extent, Facebook’s rise to the top seems inevitable. Its monthly active users grew exponentially from 2004 to 2012 , from just 1M to over 1B. In 2010, it surpassed Google as the most-visited website in the US, accounting for over 7% of weekly traffic.

But in the first few years of its founding, Facebook was considered overvalued. In 2005, Facebook’s Series A $87M valuation was thought to be too high, and investor Peter Thiel chose not to follow on. In 2006, Facebook’s users were still limited to 12M college students, and investors expected the service to fizzle out when it was released to a broader user base.

This section will cover the basic objectives of each venture funding stage, while examining the specific steps Facebook took toward a successful exit that created billions in wealth for its investors.

At the seed stage, a startup is no more than the founders and the idea. The purpose of the seed round is for the startup to figure out its product, market, and user base.

As the product starts to gain more users, the company may then look to raise a Series A. However, most startups fail to gain traction before the money runs out, and end up folding at this stage.

Seed-stage investments typically range from $250,000 to $2M, with a median between $750,000 and $1M. Angel investors, accelerators, and seed-stage VCs, such as Y Combinator, First Round Capital, and Founders Fund, invest in these rounds.

When Facebook raised its seed round, Peter Thiel, who had co-founded PayPal and had turned to angel investing, became the company’s first outside investor, buying 10.2% stake for $500,000. This put Facebook’s valuation at $5M.

LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, who also invested in the round, recalled that Zuckerberg was painfully quiet and awkward, with “a lot of staring at the desk” during their meeting. Nonetheless, Facebook’s “unreal” user engagement levels on college campuses tipped Thiel and Hoffman over the edge to invest.

Facebook used the funding to relocate to an office a few blocks away from the Stanford campus and hire more than 100 employees, many of whom were graduates of the college’s engineering program.

By the time a startup raises a Series A, it has developed a product and a business model to prove to investors that it will generate profit in the long run. The purpose of fundraising in this round is to optimize the user base and scale distribution.

Some startups skip the seed round and start by raising a Series A. This tends to happen if the founder has established credibility, prior experience in the market, or a product that has a high chance of scaling quickly with the right execution (e.g. enterprise software).

Series A rounds range from $2M-$15M, with a median of $3M-$7M. Traditional VCs such as Sequoia Capital, Benchmark, and Greylock tend to lead these rounds. While angels may co-invest, they don’t have the power to set the price or impact the round.

Accel and Breyer Capital led Facebook’s Series A in 2005, bringing its post-money valuation to nearly $100M.