Why is it important to do a literature review in research?

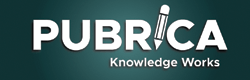

The importance of scientific communication in the healthcare industry

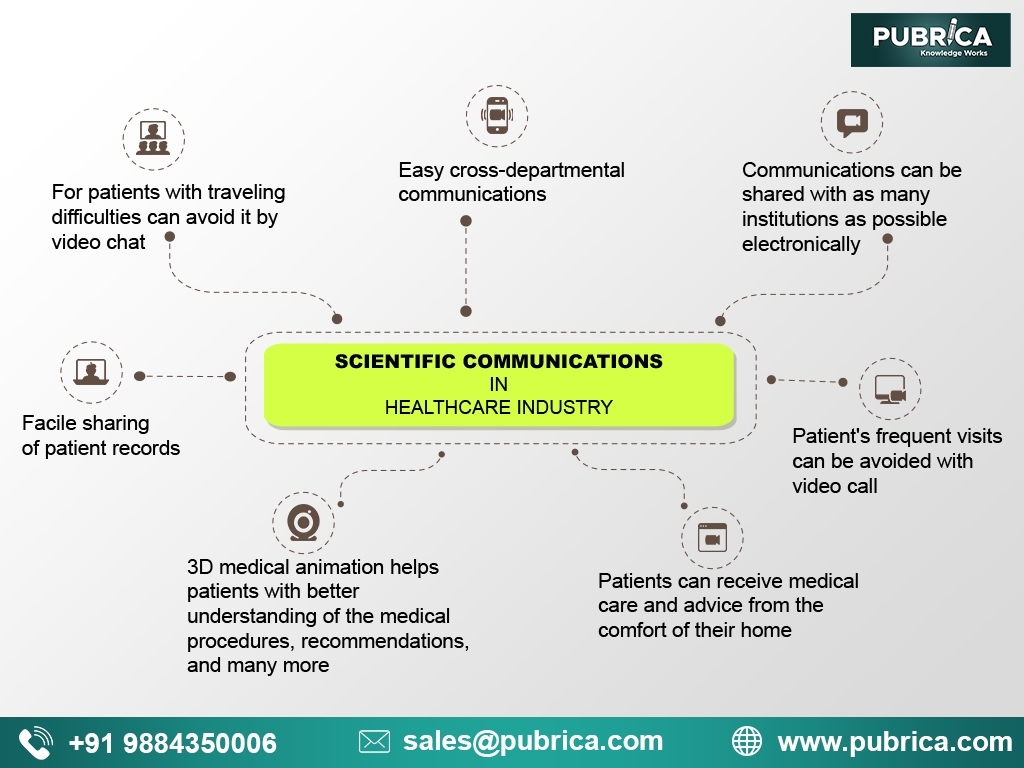

The Importance and Role of Biostatistics in Clinical Research

“A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research”. Boote and Baile 2005

Authors of manuscripts treat writing a literature review as a routine work or a mere formality. But a seasoned one knows the purpose and importance of a well-written literature review. Since it is one of the basic needs for researches at any level, they have to be done vigilantly. Only then the reader will know that the basics of research have not been neglected.

The aim of any literature review is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of existing knowledge in a particular field without adding any new contributions. Being built on existing knowledge they help the researcher to even turn the wheels of the topic of research. It is possible only with profound knowledge of what is wrong in the existing findings in detail to overpower them. For other researches, the literature review gives the direction to be headed for its success.

The common perception of literature review and reality:

As per the common belief, literature reviews are only a summary of the sources related to the research. And many authors of scientific manuscripts believe that they are only surveys of what are the researches are done on the chosen topic. But on the contrary, it uses published information from pertinent and relevant sources like

- Scholarly books

- Scientific papers

- Latest studies in the field

- Established school of thoughts

- Relevant articles from renowned scientific journals

and many more for a field of study or theory or a particular problem to do the following:

- Summarize into a brief account of all information

- Synthesize the information by restructuring and reorganizing

- Critical evaluation of a concept or a school of thought or ideas

- Familiarize the authors to the extent of knowledge in the particular field

- Encapsulate

- Compare & contrast

By doing the above on the relevant information, it provides the reader of the scientific manuscript with the following for a better understanding of it:

- It establishes the authors’ in-depth understanding and knowledge of their field subject

- It gives the background of the research

- Portrays the scientific manuscript plan of examining the research result

- Illuminates on how the knowledge has changed within the field

- Highlights what has already been done in a particular field

- Information of the generally accepted facts, emerging and current state of the topic of research

- Identifies the research gap that is still unexplored or under-researched fields

- Demonstrates how the research fits within a larger field of study

- Provides an overview of the sources explored during the research of a particular topic

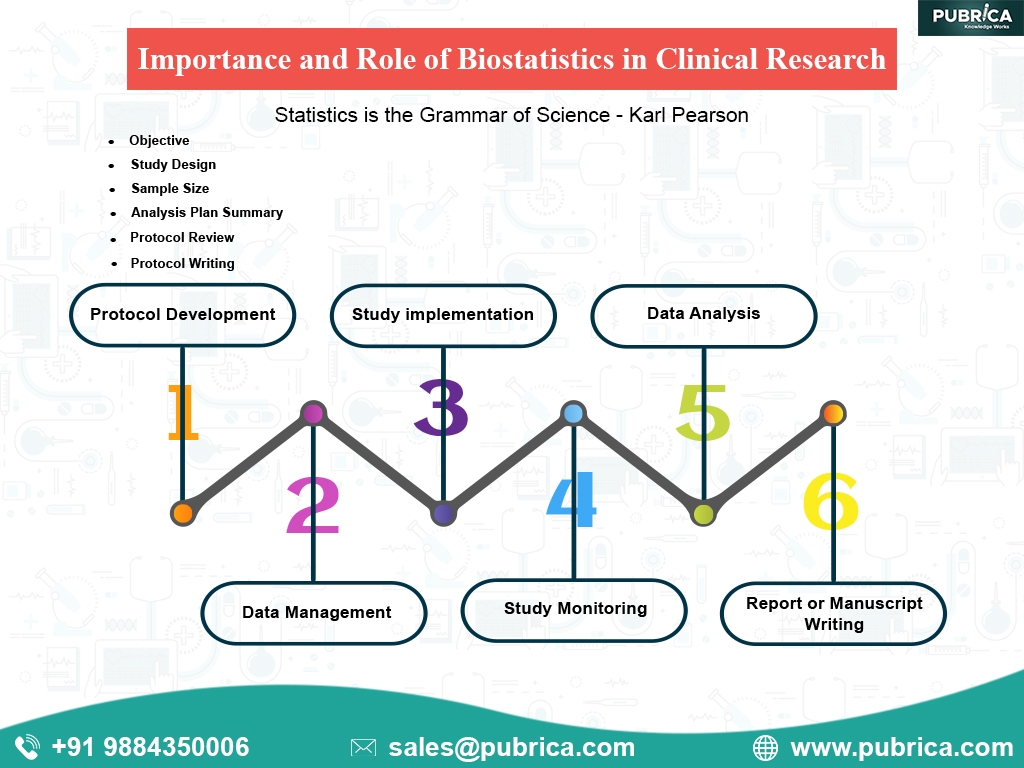

Importance of literature review in research:

The importance of literature review in scientific manuscripts can be condensed into an analytical feature to enable the multifold reach of its significance. It adds value to the legitimacy of the research in many ways:

- Provides the interpretation of existing literature in light of updated developments in the field to help in establishing the consistency in knowledge and relevancy of existing materials

- It helps in calculating the impact of the latest information in the field by mapping their progress of knowledge.

- It brings out the dialects of contradictions between various thoughts within the field to establish facts

- The research gaps scrutinized initially are further explored to establish the latest facts of theories to add value to the field

- Indicates the current research place in the schema of a particular field

- Provides information for relevancy and coherency to check the research

- Apart from elucidating the continuance of knowledge, it also points out areas that require further investigation and thus aid as a starting point of any future research

- Justifies the research and sets up the research question

- Sets up a theoretical framework comprising the concepts and theories of the research upon which its success can be judged

- Helps to adopt a more appropriate methodology for the research by examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research in the same field

- Increases the significance of the results by comparing it with the existing literature

- Provides a point of reference by writing the findings in the scientific manuscript

- Helps to get the due credit from the audience for having done the fact-finding and fact-checking mission in the scientific manuscripts

- The more the reference of relevant sources of it could increase more of its trustworthiness with the readers

- Helps to prevent plagiarism by tailoring and uniquely tweaking the scientific manuscript not to repeat other’s original idea

- By preventing plagiarism , it saves the scientific manuscript from rejection and thus also saves a lot of time and money

- Helps to evaluate, condense and synthesize gist in the author’s own words to sharpen the research focus

- Helps to compare and contrast to show the originality and uniqueness of the research than that of the existing other researches

- Rationalizes the need for conducting the particular research in a specified field

- Helps to collect data accurately for allowing any new methodology of research than the existing ones

- Enables the readers of the manuscript to answer the following questions of its readers for its better chances for publication

- What do the researchers know?

- What do they not know?

- Is the scientific manuscript reliable and trustworthy?

- What are the knowledge gaps of the researcher?

22. It helps the readers to identify the following for further reading of the scientific manuscript:

- What has been already established, discredited and accepted in the particular field of research

- Areas of controversy and conflicts among different schools of thought

- Unsolved problems and issues in the connected field of research

- The emerging trends and approaches

- How the research extends, builds upon and leaves behind from the previous research

A profound literature review with many relevant sources of reference will enhance the chances of the scientific manuscript publication in renowned and reputed scientific journals .

References:

http://www.math.montana.edu/jobo/phdprep/phd6.pdf

journal Publishing services | Scientific Editing Services | Medical Writing Services | scientific research writing service | Scientific communication services

Related Topics:

Meta Analysis

Scientific Research Paper Writing

Medical Research Paper Writing

Scientific Communication in healthcare

pubrica academy

Related posts.

Statistical analyses of case-control studies

Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient, packaging material) for drug development

Health economics in clinical trials

Comments are closed.

University Libraries

Literature review.

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is Its Purpose?

- 1. Select a Topic

- 2. Set the Topic in Context

- 3. Types of Information Sources

- 4. Use Information Sources

- 5. Get the Information

- 6. Organize / Manage the Information

- 7. Position the Literature Review

- 8. Write the Literature Review

A literature review is a comprehensive summary of previous research on a topic. The literature review surveys scholarly articles, books, and other sources relevant to a particular area of research. The review should enumerate, describe, summarize, objectively evaluate and clarify this previous research. It should give a theoretical base for the research and help you (the author) determine the nature of your research. The literature review acknowledges the work of previous researchers, and in so doing, assures the reader that your work has been well conceived. It is assumed that by mentioning a previous work in the field of study, that the author has read, evaluated, and assimiliated that work into the work at hand.

A literature review creates a "landscape" for the reader, giving her or him a full understanding of the developments in the field. This landscape informs the reader that the author has indeed assimilated all (or the vast majority of) previous, significant works in the field into her or his research.

"In writing the literature review, the purpose is to convey to the reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. The literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (eg. your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries.( http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/specific-types-of-writing/literature-review )

Recommended Reading

- Next: What is Its Purpose? >>

- Last Updated: Oct 2, 2023 12:34 PM

A Guide to Literature Reviews

Importance of a good literature review.

- Conducting the Literature Review

- Structure and Writing Style

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Citation Management Software This link opens in a new window

- Acknowledgements

A literature review is not only a summary of key sources, but has an organizational pattern which combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

- << Previous: Definition

- Next: Conducting the Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 3:13 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mcmaster.ca/litreview

Literature Review - what is a Literature Review, why it is important and how it is done

What are literature reviews, goals of literature reviews, types of literature reviews, about this guide/licence.

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Literature Reviews and Sources

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

- Useful Resources

Help is Just a Click Away

Search our FAQ Knowledge base, ask a question, chat, send comments...

Go to LibAnswers

What is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries. " - Quote from Taylor, D. (n.d) "The literature review: A few tips on conducting it"

Source NC State University Libraries. This video is published under a Creative Commons 3.0 BY-NC-SA US license.

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review?

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

- Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1997). "Writing narrative literature reviews," Review of General Psychology , 1(3), 311-320.

When do you need to write a Literature Review?

- When writing a prospectus or a thesis/dissertation

- When writing a research paper

- When writing a grant proposal

In all these cases you need to dedicate a chapter in these works to showcase what have been written about your research topic and to point out how your own research will shed a new light into these body of scholarship.

Literature reviews are also written as standalone articles as a way to survey a particular research topic in-depth. This type of literature reviews look at a topic from a historical perspective to see how the understanding of the topic have change through time.

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

- Narrative Review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Book review essays/ Historiographical review essays : This is a type of review that focus on a small set of research books on a particular topic " to locate these books within current scholarship, critical methodologies, and approaches" in the field. - LARR

- Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L.K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

- Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M.C. & Ilardi, S.S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

- Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). "Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts," Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53(3), 311-318.

Guide adapted from "Literature Review" , a guide developed by Marisol Ramos used under CC BY 4.0 /modified from original.

- Next: Strategies to Find Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 10:56 AM

- URL: https://lit.libguides.com/Literature-Review

The Library, Technological University of the Shannon: Midwest

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved July 27, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Jul 15, 2024 10:34 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.3 Reviewing the Research Literature

Learning objectives.

- Define the research literature in psychology and give examples of sources that are part of the research literature and sources that are not.

- Describe and use several methods for finding previous research on a particular research idea or question.

Reviewing the research literature means finding, reading, and summarizing the published research relevant to your question. An empirical research report written in American Psychological Association (APA) style always includes a written literature review, but it is important to review the literature early in the research process for several reasons.

- It can help you turn a research idea into an interesting research question.

- It can tell you if a research question has already been answered.

- It can help you evaluate the interestingness of a research question.

- It can give you ideas for how to conduct your own study.

- It can tell you how your study fits into the research literature.

What Is the Research Literature?

The research literature in any field is all the published research in that field. The research literature in psychology is enormous—including millions of scholarly articles and books dating to the beginning of the field—and it continues to grow. Although its boundaries are somewhat fuzzy, the research literature definitely does not include self-help and other pop psychology books, dictionary and encyclopedia entries, websites, and similar sources that are intended mainly for the general public. These are considered unreliable because they are not reviewed by other researchers and are often based on little more than common sense or personal experience. Wikipedia contains much valuable information, but the fact that its authors are anonymous and its content continually changes makes it unsuitable as a basis of sound scientific research. For our purposes, it helps to define the research literature as consisting almost entirely of two types of sources: articles in professional journals, and scholarly books in psychology and related fields.

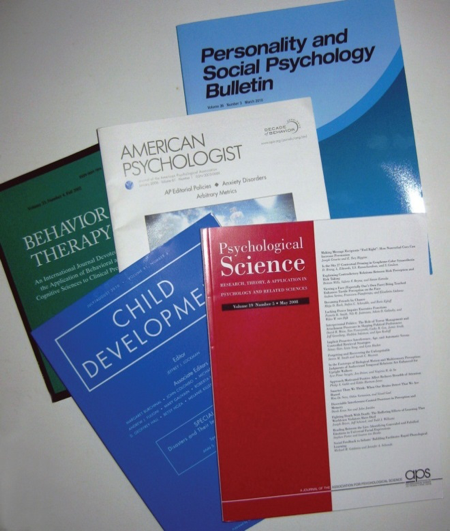

Professional Journals

Professional journals are periodicals that publish original research articles. There are thousands of professional journals that publish research in psychology and related fields. They are usually published monthly or quarterly in individual issues, each of which contains several articles. The issues are organized into volumes, which usually consist of all the issues for a calendar year. Some journals are published in hard copy only, others in both hard copy and electronic form, and still others in electronic form only.

Most articles in professional journals are one of two basic types: empirical research reports and review articles. Empirical research reports describe one or more new empirical studies conducted by the authors. They introduce a research question, explain why it is interesting, review previous research, describe their method and results, and draw their conclusions. Review articles summarize previously published research on a topic and usually present new ways to organize or explain the results. When a review article is devoted primarily to presenting a new theory, it is often referred to as a theoretical article .

Figure 2.6 Small Sample of the Thousands of Professional Journals That Publish Research in Psychology and Related Fields

Most professional journals in psychology undergo a process of peer review . Researchers who want to publish their work in the journal submit a manuscript to the editor—who is generally an established researcher too—who in turn sends it to two or three experts on the topic. Each reviewer reads the manuscript, writes a critical review, and sends the review back to the editor along with his or her recommendations. The editor then decides whether to accept the article for publication, ask the authors to make changes and resubmit it for further consideration, or reject it outright. In any case, the editor forwards the reviewers’ written comments to the researchers so that they can revise their manuscript accordingly. Peer review is important because it ensures that the work meets basic standards of the field before it can enter the research literature.

Scholarly Books

Scholarly books are books written by researchers and practitioners mainly for use by other researchers and practitioners. A monograph is written by a single author or a small group of authors and usually gives a coherent presentation of a topic much like an extended review article. Edited volumes have an editor or a small group of editors who recruit many authors to write separate chapters on different aspects of the same topic. Although edited volumes can also give a coherent presentation of the topic, it is not unusual for each chapter to take a different perspective or even for the authors of different chapters to openly disagree with each other. In general, scholarly books undergo a peer review process similar to that used by professional journals.

Literature Search Strategies

Using psycinfo and other databases.

The primary method used to search the research literature involves using one or more electronic databases. These include Academic Search Premier, JSTOR, and ProQuest for all academic disciplines, ERIC for education, and PubMed for medicine and related fields. The most important for our purposes, however, is PsycINFO , which is produced by the APA. PsycINFO is so comprehensive—covering thousands of professional journals and scholarly books going back more than 100 years—that for most purposes its content is synonymous with the research literature in psychology. Like most such databases, PsycINFO is usually available through your college or university library.

PsycINFO consists of individual records for each article, book chapter, or book in the database. Each record includes basic publication information, an abstract or summary of the work, and a list of other works cited by that work. A computer interface allows entering one or more search terms and returns any records that contain those search terms. (These interfaces are provided by different vendors and therefore can look somewhat different depending on the library you use.) Each record also contains lists of keywords that describe the content of the work and also a list of index terms. The index terms are especially helpful because they are standardized. Research on differences between women and men, for example, is always indexed under “Human Sex Differences.” Research on touching is always indexed under the term “Physical Contact.” If you do not know the appropriate index terms, PsycINFO includes a thesaurus that can help you find them.

Given that there are nearly three million records in PsycINFO, you may have to try a variety of search terms in different combinations and at different levels of specificity before you find what you are looking for. Imagine, for example, that you are interested in the question of whether women and men differ in terms of their ability to recall experiences from when they were very young. If you were to enter “memory for early experiences” as your search term, PsycINFO would return only six records, most of which are not particularly relevant to your question. However, if you were to enter the search term “memory,” it would return 149,777 records—far too many to look through individually. This is where the thesaurus helps. Entering “memory” into the thesaurus provides several more specific index terms—one of which is “early memories.” While searching for “early memories” among the index terms returns 1,446 records—still too many too look through individually—combining it with “human sex differences” as a second search term returns 37 articles, many of which are highly relevant to the topic.

Depending on the vendor that provides the interface to PsycINFO, you may be able to save, print, or e-mail the relevant PsycINFO records. The records might even contain links to full-text copies of the works themselves. (PsycARTICLES is a database that provides full-text access to articles in all journals published by the APA.) If not, and you want a copy of the work, you will have to find out if your library carries the journal or has the book and the hard copy on the library shelves. Be sure to ask a librarian if you need help.

Using Other Search Techniques

In addition to entering search terms into PsycINFO and other databases, there are several other techniques you can use to search the research literature. First, if you have one good article or book chapter on your topic—a recent review article is best—you can look through the reference list of that article for other relevant articles, books, and book chapters. In fact, you should do this with any relevant article or book chapter you find. You can also start with a classic article or book chapter on your topic, find its record in PsycINFO (by entering the author’s name or article’s title as a search term), and link from there to a list of other works in PsycINFO that cite that classic article. This works because other researchers working on your topic are likely to be aware of the classic article and cite it in their own work. You can also do a general Internet search using search terms related to your topic or the name of a researcher who conducts research on your topic. This might lead you directly to works that are part of the research literature (e.g., articles in open-access journals or posted on researchers’ own websites). The search engine Google Scholar is especially useful for this purpose. A general Internet search might also lead you to websites that are not part of the research literature but might provide references to works that are. Finally, you can talk to people (e.g., your instructor or other faculty members in psychology) who know something about your topic and can suggest relevant articles and book chapters.

What to Search For

When you do a literature review, you need to be selective. Not every article, book chapter, and book that relates to your research idea or question will be worth obtaining, reading, and integrating into your review. Instead, you want to focus on sources that help you do four basic things: (a) refine your research question, (b) identify appropriate research methods, (c) place your research in the context of previous research, and (d) write an effective research report. Several basic principles can help you find the most useful sources.

First, it is best to focus on recent research, keeping in mind that what counts as recent depends on the topic. For newer topics that are actively being studied, “recent” might mean published in the past year or two. For older topics that are receiving less attention right now, “recent” might mean within the past 10 years. You will get a feel for what counts as recent for your topic when you start your literature search. A good general rule, however, is to start with sources published in the past five years. The main exception to this rule would be classic articles that turn up in the reference list of nearly every other source. If other researchers think that this work is important, even though it is old, then by all means you should include it in your review.

Second, you should look for review articles on your topic because they will provide a useful overview of it—often discussing important definitions, results, theories, trends, and controversies—giving you a good sense of where your own research fits into the literature. You should also look for empirical research reports addressing your question or similar questions, which can give you ideas about how to operationally define your variables and collect your data. As a general rule, it is good to use methods that others have already used successfully unless you have good reasons not to. Finally, you should look for sources that provide information that can help you argue for the interestingness of your research question. For a study on the effects of cell phone use on driving ability, for example, you might look for information about how widespread cell phone use is, how frequent and costly motor vehicle crashes are, and so on.

How many sources are enough for your literature review? This is a difficult question because it depends on how extensively your topic has been studied and also on your own goals. One study found that across a variety of professional journals in psychology, the average number of sources cited per article was about 50 (Adair & Vohra, 2003). This gives a rough idea of what professional researchers consider to be adequate. As a student, you might be assigned a much lower minimum number of references to use, but the principles for selecting the most useful ones remain the same.

Key Takeaways

- The research literature in psychology is all the published research in psychology, consisting primarily of articles in professional journals and scholarly books.

- Early in the research process, it is important to conduct a review of the research literature on your topic to refine your research question, identify appropriate research methods, place your question in the context of other research, and prepare to write an effective research report.

- There are several strategies for finding previous research on your topic. Among the best is using PsycINFO, a computer database that catalogs millions of articles, books, and book chapters in psychology and related fields.

- Practice: Use the techniques discussed in this section to find 10 journal articles and book chapters on one of the following research ideas: memory for smells, aggressive driving, the causes of narcissistic personality disorder, the functions of the intraparietal sulcus, or prejudice against the physically handicapped.

Adair, J. G., & Vohra, N. (2003). The explosion of knowledge, references, and citations: Psychology’s unique response to a crisis. American Psychologist, 58 , 15–23.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Thomas G. Carpenter Library

Conducting a Literature Review

Benefits of conducting a literature review.

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Summary of the Process

- Additional Resources

- Literature Review Tutorial by American University Library

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It by University of Toronto

- Write a Literature Review by UC Santa Cruz University Library

While there might be many reasons for conducting a literature review, following are four key outcomes of doing the review.

Assessment of the current state of research on a topic . This is probably the most obvious value of the literature review. Once a researcher has determined an area to work with for a research project, a search of relevant information sources will help determine what is already known about the topic and how extensively the topic has already been researched.

Identification of the experts on a particular topic . One of the additional benefits derived from doing the literature review is that it will quickly reveal which researchers have written the most on a particular topic and are, therefore, probably the experts on the topic. Someone who has written twenty articles on a topic or on related topics is more than likely more knowledgeable than someone who has written a single article. This same writer will likely turn up as a reference in most of the other articles written on the same topic. From the number of articles written by the author and the number of times the writer has been cited by other authors, a researcher will be able to assume that the particular author is an expert in the area and, thus, a key resource for consultation in the current research to be undertaken.

Identification of key questions about a topic that need further research . In many cases a researcher may discover new angles that need further exploration by reviewing what has already been written on a topic. For example, research may suggest that listening to music while studying might lead to better retention of ideas, but the research might not have assessed whether a particular style of music is more beneficial than another. A researcher who is interested in pursuing this topic would then do well to follow up existing studies with a new study, based on previous research, that tries to identify which styles of music are most beneficial to retention.

Determination of methodologies used in past studies of the same or similar topics. It is often useful to review the types of studies that previous researchers have launched as a means of determining what approaches might be of most benefit in further developing a topic. By the same token, a review of previously conducted studies might lend itself to researchers determining a new angle for approaching research.

Upon completion of the literature review, a researcher should have a solid foundation of knowledge in the area and a good feel for the direction any new research should take. Should any additional questions arise during the course of the research, the researcher will know which experts to consult in order to quickly clear up those questions.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2022 8:54 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/litreview

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

5 Reasons the Literature Review Is Crucial to Your Paper

- 3-minute read

- 8th November 2016

People often treat writing the literature review in an academic paper as a formality. Usually, this means simply listing various studies vaguely related to their work and leaving it at that.

But this overlooks how important the literature review is to a well-written experimental report or research paper. As such, we thought we’d take a moment to go over what a literature review should do and why you should give it the attention it deserves.

What Is a Literature Review?

Common in the social and physical sciences, but also sometimes required in the humanities, a literature review is a summary of past research in your subject area.

Sometimes this is a standalone investigation of how an idea or field of inquiry has developed over time. However, more usually it’s the part of an academic paper, thesis or dissertation that sets out the background against which a study takes place.

There are several reasons why we do this.

Reason #1: To Demonstrate Understanding

In a college paper, you can use a literature review to demonstrate your understanding of the subject matter. This means identifying, summarizing and critically assessing past research that is relevant to your own work.

Reason #2: To Justify Your Research

The literature review also plays a big role in justifying your study and setting your research question . This is because examining past research allows you to identify gaps in the literature, which you can then attempt to fill or address with your own work.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Reason #3: Setting a Theoretical Framework

It can help to think of the literature review as the foundations for your study, since the rest of your work will build upon the ideas and existing research you discuss therein.

A crucial part of this is formulating a theoretical framework , which comprises the concepts and theories that your work is based upon and against which its success will be judged.

Reason #4: Developing a Methodology

Conducting a literature review before beginning research also lets you see how similar studies have been conducted in the past. By examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research, you can thus make sure you adopt the most appropriate methods, data sources and analytical techniques for your own work.

Reason #5: To Support Your Own Findings

The significance of any results you achieve will depend to some extent on how they compare to those reported in the existing literature. When you come to write up your findings, your literature review will therefore provide a crucial point of reference.

If your results replicate past research, for instance, you can say that your work supports existing theories. If your results are different, though, you’ll need to discuss why and whether the difference is important.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

University Libraries University of Nevada, Reno

- Skill Guides

- Subject Guides

Literature Reviews

- Searching for Literature

- Organizing Literature and Taking Notes

- Writing and Editing the Paper

- Help and Resources

Organizing Your Paper

Before you begin writing your paper, you will need to decide upon a way to organize your information. You can organize your paper using a number of different strategies, such as the following:

- Topics and subtopics : Discussing your sources in relation to different topics and subtopics; probably the most common approach

- Chronologically : Discussing your sources from oldest to newest in order to show trends or changes in the approach to a topic over time

- Methods : Discussing your sources by different methods that are used to approach the topic

When literature reviews are incorporated into a research paper, they are often structured using the funnel method , which begins with a broad overview of a topic and then narrows down to more specific themes before focusing in on the specific research question that the paper will address.

A literature review paper often follows this basic organization:

Introduction

- Describes the importance of the topic

- Defines key terms

- Describes the goals of the review

- Provides an overview of the literature to be discussed (e.g., methods, trends, etc.) (optional)

- Describes parameters of the review and particular search methods used (optional)

- Discusses findings of sources, as well as strengths, weaknesses, similarities, differences, contradictions, and gaps

- Divides content into sections (for longer reviews), uses headings and subheadings to indicate section divisions, and provides brief summaries at the end of each section

- Summarizes what is known about the topic

- Discusses implications for practice

- Discusses areas for further research

Synthesizing Sources

A literature review paper not only describes and evaluates the scholarly research literature related to a particular topic, but it also synthesizes that information. Synthesis is the process of weaving together information from sources to arrive at new analyses and insights.

To help you prepare to synthesize sources in your paper, you can take the topic matrix that you prepared as you were organizing your sources, and flesh it out into a synthesis matrix that contains detailed notes from each source as they relate to different topics and subtopics of your literature review. Once you've completed your synthesis matrix, you can more easily identify ways that sources relate to each other in terms of their similarities and differences, methodological strengths and weakness, and contradictions and gaps. The video below shows how to create a synthesis matrix.

Video: Synthesis Matrix Tutorial by Andrew Davis .

Writing Your Paper

A literature review paper should flow logically from one topic to the next. As you write your paper, consider these tips:

- Write in a formal voice and with an impartial tone.

- Define critical terms and describe key theories.

- Use topic sentences to clearly indicate what each paragraph is about.

- Use transitions to make links between sections.

- Introduce acronyms upon first using them.

- Call attention to seminal (i.e., highly influential; groundbreaking) studies.

- Clearly distinguish between your ideas and those of the authors you cite.

- Cite multiple sources for a single idea, if appropriate.

- Create a list of references that follows appropriate style guidelines.

- Give your paper a title that conveys what the literature review is about.

- Once you have written your paper, carefully proofread it for errors.

- << Previous: Organizing Literature and Taking Notes

- Next: Help and Resources >>

The History of Peer Review Is More Interesting Than You Think

The term “peer review” was coined in the 1970s, but the referee principle is usually assumed to be as old as the scientific enterprise itself. (It isn’t.)

Peer review has become a cornerstone of academic publishing, a fundamental part of scholarship itself. With peer review, independent, third-party experts in the relevant field(s) assess manuscripts submitted to journals. The idea is that these expert peers referee the process, especially when it comes to technical matters that may be beyond the knowledge of editors.

“In all fields of academia, reputations and careers are now expected to be built on peer-reviewed publication; concerns with its efficacy and appropriateness thus seem to strike at the heart of scholarship,” write historians Noah Moxham and Aileen Fyfe .

The peer review system, continue Moxham and Fyfe, is “crucial to building the reputation both of individual scientists and of the scientific enterprise at large” because the process

is believed to certify the quality and reliability of research findings. It promises supposedly impartial evaluation of research, through close scrutiny by specialists, and is widely used by journal editors, grant-making bodies, and government.

As with any human enterprise, peer review is far from foolproof . Errors and downright frauds have made it through the process. In addition, as Moxham and Fyfe note, there can be “inappropriate bias due to the social dynamics of the process.” (Some peer review types may introduce less bias than others.)

The term “peer review” was coined in the early 1970s, but the referee principle is usually assumed to be about as old as the scientific enterprise itself, dating to the Royal Society of London’s Philosophical Transactions , which began publication in 1665.

Moxham and Fyfe complicate this history, using the Royal Society’s “rich archives” to trace the evolution of editorial practices at one of the earliest scientific societies.

Initially, the publication of Philosophical Transactions was a private venture managed by the Society’s secretaries. Secretary Henry Oldenburg, the first editor, ran it from 1665 to 1677, without, write Moxham and Fyfe, any “clear set of standards.”

Research sponsored by the Royal Society itself was published separately from the Transactions . In fact, the royally chartered Society had the power to license publication of books and periodicals (like the Transactions ) as “part of a wider mechanism of state censorship intended to ensure the proscription of politically seditious or religious heterodox material.” But as time passed, there wasn’t really much Society oversight over the publication at all.

The situation came to a crisis in the early 1750s, when an unsuccessful candidate for a Society fellowship raised a ruckus, conflating the separate administrations of the Society and the now rather stodgy Transactions. The bad press compelled the Society to take over financial and editorial control—by committee—of the Transactions in 1752. The editorial committee could refer submissions to fellows with particular expertise—but papers were already being vetted since they needed to be referred by fellows in the first place.

Formalization of the use of expert referees would be institutionalized by 1832. A “written report of fitness” of submissions by one or more fellows was to be made before acceptance. This followed similar procedures already introduced abroad, particularly at the Académie des sciences in Paris.

All of this, Moxham and Fyfe argue, was more about institution-building (and fortification) than what we know as peer reviewing today.

“Refereeing and associated editorial practices” were intended to “disarm specific attacks upon the eighteenth-century Society; sometimes, to protect the Society’s finances; and, by the later nineteenth century, to award prestige to members of the nascent profession of natural scientists.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

From 1752 to 1957, the front of every Transactions included an “ Advertisement ” noting that the Society could not pretend to “answer for the certainty of the facts, or propriety of the reasonings” of the papers contained within; all that “must still rest on the credit or judgement of their respective authors.”

The twentieth century saw a plethora of independent scientific journals and an exponential increase in scientific papers. “Professional, international scientific research” burst the bounds of the old learned societies with their gentlemanly ways. In 1973, the journal Nature (founded in 1869) made refereeing standard practice, to “raise the journal above accusations of cronyism and elitism.” Since then, peer review, as it came to be called in preference to refereeing, has become universal. At least in avowed “peer-reviewed journals.”

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

From Gamification to Game-Based Learning

Brunei: A Tale of Soil and Oil

Why Architects Need Philosophy to Guide the AI Design Revolution

Inside China’s Psychoboom

Recent posts.

- Foreign Magic in Imperial Rome

- Cassini’s First Years at Saturn

- Debt-for-Nature Swaps: Solution or Scam?

- The Magical Furniture of David Roentgen

- Rosalind Franklin’s Methods of Discovery

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- Open access

- Published: 24 July 2024

A self-assessment maturity matrix to support large-scale change using collaborative networks in the New Zealand health system

- Kanchan M. Sharma 1 ,

- Peter B. Jones 2 ,

- Jacqueline Cumming 3 &

- Lesley Middleton 4