45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

✍️Essay on Humanity in 100 to 300 Words

- Updated on

- Oct 26, 2023

Humanity could be understood through different perspectives. Humanity refers to acts of kindness, care, and compassion towards humans or animals. Humanity is the positive quality of human beings. This characteristic involves the feeling of love, care, reason, decision, cry, etc. Our history reveals many acts of inhuman and human behaviour. Such acts differentiate the good and the bad. Some of the key characteristics of Humanity are intelligence, creativity , empathy and compassion. Here are some sample essay on Humanity that will tell about the importance and meaning of Humanity!

Table of Contents

- 1 Essay on Humanity 100 Words

- 2.1 Importance of Humanity

Also Read: Essay on Family

Essay on Humanity 100 Words

Humanity is the sum of all the qualities that make us human. We should seek inspiration from the great humanitarians from our history like Mahatma Gandhi , Nelson Mandela , Mother Teresa , and many more. They all devoted their life serving the cause of humanity. Their tireless efforts for the betterment of the needy make the world a better place.

In a world suffering from a humanitarian crisis, there is an urgent need to raise awareness about the works of humanitarians who died serving for a noble cause. World Humanitarian Day is celebrated on 19 August every year to encourage humanity.

Here are some examples of humanity:

- Firefighters risking their lives to save someone stuck in a burning building.

- Raising voices for basic human rights.

- Blood donation to save lives is also an example of humanity.

- A doctor volunteering to work in a war zone.

Also Read: Famous Personalities in India

Essay on Humanity 300 Words

Humanity is the concept that lies at the core of our existence. It contains the essence of what makes us humans. It encompasses our capacity for empathy, compassion, and understanding, and it is a driving force behind our progress as a species. In a world often characterized by division and war, the essence of humanity shines as a ray of hope, reminding us of our shared values and aspirations.

One of the defining characteristics of humanity is our ability to empathize with others. Empathy allows us to connect with people on a profound level, to feel their joys and sorrows, and to provide support in times of need. It bridges the gaps that might otherwise separate us, creating a sense of unity in the face of adversity. Even comforting a friend in distress is a sign of humanity.

Also Read: Emotional Intelligence at Workplace

Importance of Humanity

Compassion is the fundamental element of humanity. It is the driving force behind acts of kindness, charity, and selflessness. Humanity is important to protect cultural, religious, and geographical boundaries, as it is a universal language understood by all.

When we extend some help to those in need out of humanity, we affirm our commitment to the well-being of others and demonstrate our shared responsibility for the betterment of society.

Humanity balances out the evil doings in the world. It creates a better world for all to reside. Humanity is the foundation of the existence of humans because it makes us what we are and differentiate us from other living organism who do not possess the ability to think and feel. It is a testament to our potential for progress and unity.

In conclusion, humanity, with its pillars of empathy, compassion, and understanding, serves as a guiding light in a complex and divided world. These qualities remind us that, despite our differences, we are all part of the human family.

Related Articles

Humanity is a complex characteristic of any human being. It includes the ability of a person to differentiate between good and bad and to show sympathy and shared connections as human beings. The human race can win any war be it harsh climatic conditions, pandemic, economic crisis, etc, if they have humanity towards each other. Humans have the potential to solve problems and make the world a better place for all.

An essay on humanity should be started with an introduction paragraph stating the zest of the complete essay. It should include the meaning of humanity. You need to highlight the positive characteristics of the act of humanity and how it can work for the betterment of society.

Humanity is very important because this characteristic of human beings makes the world a better place to live. It is what makes us humans. Humanity is the feeling of care and compassion towards other beings and gives us the ability to judge between right and wrong.

For more information on such interesting topics, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu .

Kajal Thareja

Hi, I am Kajal, a pharmacy graduate, currently pursuing management and is an experienced content writer. I have 2-years of writing experience in Ed-tech (digital marketing) company. I am passionate towards writing blogs and am on the path of discovering true potential professionally in the field of content marketing. I am engaged in writing creative content for students which is simple yet creative and engaging and leaves an impact on the reader's mind.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

Essay on Love for Students and Children

500+ words essay on love.

Love is the most significant thing in human’s life. Each science and every single literature masterwork will tell you about it. Humans are also social animals. We lived for centuries with this way of life, we were depended on one another to tell us how our clothes fit us, how our body is whether healthy or emaciated. All these we get the honest opinions of those who love us, those who care for us and makes our happiness paramount.

What is Love?

Love is a set of emotions, behaviors, and beliefs with strong feelings of affection. So, for example, a person might say he or she loves his or her dog, loves freedom, or loves God. The concept of love may become an unimaginable thing and also it may happen to each person in a particular way.

Love has a variety of feelings, emotions, and attitude. For someone love is more than just being interested physically in another one, rather it is an emotional attachment. We can say love is more of a feeling that a person feels for another person. Therefore, the basic meaning of love is to feel more than liking towards someone.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Need of Love

We know that the desire to love and care for others is a hard-wired and deep-hearted because the fulfillment of this wish increases the happiness level. Expressing love for others benefits not just the recipient of affection, but also the person who delivers it. The need to be loved can be considered as one of our most basic and fundamental needs.

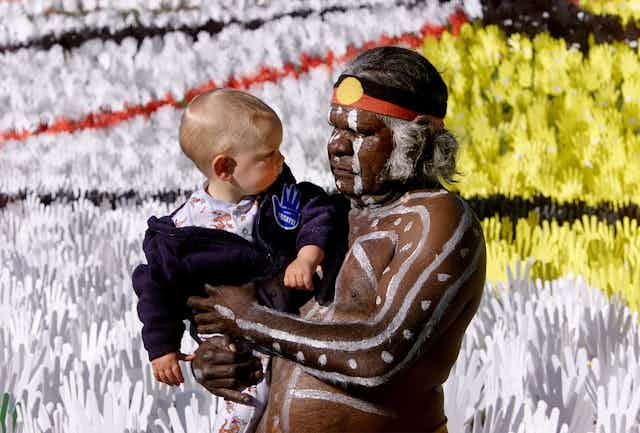

One of the forms that this need can take is contact comfort. It is the desire to be held and touched. So there are many experiments showing that babies who are not having contact comfort, especially during the first six months, grow up to be psychologically damaged.

Significance of Love

Love is as critical for the mind and body of a human being as oxygen. Therefore, the more connected you are, the healthier you will be physically as well as emotionally. It is also true that the less love you have, the level of depression will be more in your life. So, we can say that love is probably the best antidepressant.

It is also a fact that the most depressed people don’t love themselves and they do not feel loved by others. They also become self-focused and hence making themselves less attractive to others.

Society and Love

It is a scientific fact that society functions better when there is a certain sense of community. Compassion and love are the glue for society. Hence without it, there is no feeling of togetherness for further evolution and progress. Love , compassion, trust and caring we can say that these are the building blocks of relationships and society.

Relationship and Love

A relationship is comprised of many things such as friendship , sexual attraction , intellectual compatibility, and finally love. Love is the binding element that keeps a relationship strong and solid. But how do you know if you are in love in true sense? Here are some symptoms that the emotion you are feeling is healthy, life-enhancing love.

Love is the Greatest Wealth in Life

Love is the greatest wealth in life because we buy things we love for our happiness. For example, we build our dream house and purchase a favorite car to attract love. Being loved in a remote environment is a better experience than been hated even in the most advanced environment.

Love or Money

Love should be given more importance than money as love is always everlasting. Money is important to live, but having a true companion you can always trust should come before that. If you love each other, you will both work hard to help each other live an amazing life together.

Love has been a vital reason we do most things in our life. Before we could know ourselves, we got showered by it from our close relatives like mothers , fathers , siblings, etc. Thus love is a unique gift for shaping us and our life. Therefore, we can say that love is a basic need of life. It plays a vital role in our life, society, and relation. It gives us energy and motivation in a difficult time. Finally, we can say that it is greater than any other thing in life.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

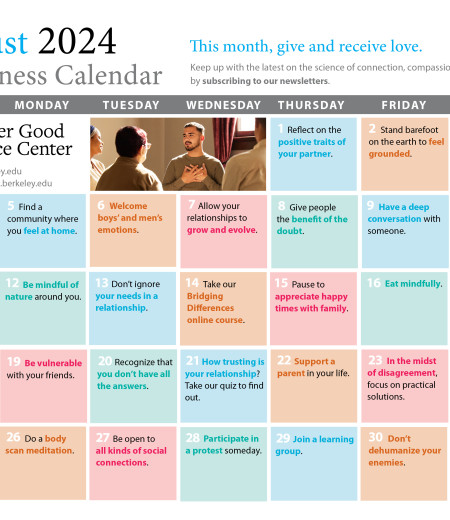

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Is It Possible to Love All Humanity?

When was the last time you thought about the fact that you are a member of the human species?

For most of us, this aspect of our identity is not front and center. More relevant are things like gender, ethnicity, nationality, religion, political party, sports team affiliations, and all of our other group memberships, large and small. Not only do we stake our identity and often also our sense of self-worth in these groups, but we tend to be more helpful towards those who belong to them, often at the expense of those who do not.

A significant minority of people, however, seem less concerned with group distinctions. As Stephen Asma recently argued in the New York Times Opinionater blog, these small group loyalties are both natural and inevitable, given our limited emotional and physical resources.

But while it may be true that we cannot be everywhere at once or love everyone equally, many forms of human connection are more like muscles to be strengthened than pools to be drained.

For a significant minority of people, this sense of limitless kinship is particularly strong. For example, while many turned a blind eye, some individuals risked their lives to rescue Jews during the Holocaust. In interviews conducted by Kristen Renwick Monroe for her book, The Heart of Altruism , many of these individuals described a sense of common humanity, or “belonging to one human family.” Those who did not offer help were less likely to possess this feeling of expanded kinship.

In a recent article published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , psychologists Sam McFarland, Matthew Webb, and Derek Brown developed a new scale for measuring individual differences in this attribute, the Identification With All Humanity scale (IWAH).

The scale involves a series of questions assessing the degree to which someone identifies with “all humans everywhere” (“identifying” includes things like feeling love toward, feeling similar to, and believing in), independent of how much they identify with people in their own community and country. They then examined how scores on this measure relate to various personality traits and behaviors. Here are four highlights from the findings.

1. It’s more than just being a good person.

Plenty of scales exist to measure traits like altruism, compassion, and interdependent self-construal, but these kinds of scales do not differentiate between people who feel connected only to a specific group of people and those who feel connected to all people.

Sometimes the two are even inversely correlated, as evidenced by research suggesting that, paradoxically, those living in collectivist cultures, though willing to sacrifice for their group members, may be even less likely to help outgroup members, compared to members of individualistic cultures. In other words, you might feel nothing but good will towards people who are similar to you, but how do you feel about people whose values or lifestyles are different from your own?

The IWAH is unique in that it identifies where people draw the line, and therefore it can make meaningful predictions about their behavior in a wider range of situations. The researchers found, for example, that people who score high in IWAH are also more concerned about global issues such as combating world hunger and addressing human rights violations, even when controlling for dispositional empathy and moral concern.

2. Caring about humanity might make you a nervous wreck.

Not surprisingly, people high in IWAH tend to be higher in the personality traits of openness to experience and agreeableness. But it turns out that they are also higher in neuroticism, a trait characterized by anxiety and negativity.

More on Loving Humanity

Take our quiz to measure how much you love humanity .

Learn how to increase your compassion bandwidth .

Discover more Greater Good articles and videos about the science of compassion and altruism .

The researchers find this perplexing: “We cannot hazard a guess,” they write, “as why those who agree with items such as ‘I would feel afraid if I had to travel in bad weather conditions’ and ‘I sometimes can’t help worrying about little things’ identify more strongly than others with all humanity.”

I’m not sure about the bad weather connection, but to me it’s not actually that surprising that those who worry about little things also worry about big things, like the state of humanity. If you truly care about the welfare of people across the world, many of whom are ravaged by war, natural disasters, and disease, how can that not cause you anguish? (And, looking at it the other way around, if you’re a generally anxious person, it’s maybe not so surprising that human suffering and injustice would enter into your repertoire of worries.)

3. “Every other person is basically you.”

As one of the Holocaust rescuers quoted in the article puts it, every life is worth just as much as one’s own. While most people value the lives of ingroup over outgroup members, those high in IWAH were found to value ingroup and outgroup lives more equally (in this case, American vs. Afghani lives).

Value placed on lives was measured by having participants choose between policies that pit lives in one country against economic loss or gain in the other (e.g., a loss of Afghani lives versus an increase in grocery prices in the U.S; a loss of American lives versus a loss of shelter for Afghani civilians) and comparing those policy preferences.

But what if these individuals were forced to make a direct choice between American and Afghani lives, or between the lives of family members and strangers? One might imagine that even the most devout humanitarian would prioritize the lives of those closest to them. We may strive to transcend group boundaries, but when it comes down to it, we are social beings who thrive on loyalty and belonging. It’s hard to imagine a world without any distinctions at all.

4. Is humanitarianism a luxury?

The main purpose of this research was to develop a scale to capture IWAH, but the researchers also speculate, in their conclusion, about why some people become high in IWAH and others do not.

One possible explanation is that a loving, secure childhood environment allows people to feel less threatened by those who are different from themselves (and indeed, attachment security primes have been shown to reduce intergroup bias ).

This reasoning led the researchers to question whether IWAH might be somewhat of a luxury, something that a person can only focus on when their own basic physical and psychological needs are met. In other words, maybe it’s only the privileged who have the time and resources to concern themselves with global human welfare.

But it seems that identification with humanity is possible even in the most dire of circumstances, as it was for the Holocaust rescuers whose own safety was clearly at risk, or for victims of natural disasters who have lost everything and yet still help strangers get back on their feet.

The Greater Good Science Center has developed a quiz , based on the IWAH scale, to measure how much you love humanity. When you’re done, you’ll get your score, along with ideas for increasing your feelings of connection to humankind.

About the Author

Juliana Breines

Juliana Breines, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral fellow at Brandeis University.

You May Also Enjoy

Is Violence on the Decline?

The Compassionate Instinct

Steven Pinker’s History of (Non)Violence

Is There an Altruism Gene?

The Compassionate Species

Beyond Sex and Violence

Our ability to identify with other humans failed an important test this past week. During the confirmation hearing of John Brennan (the president’s nominee for CIA director) much attention was drawn to the constitutional problems presented by the administration’s killing of American citizens abroad. But precious little attention was focused on the killing of Pakistanis, Afghans, Yemenis, and Somalis - many of whom are innocent civilians having absolutely no connection to the terrorist threat we are told to fear.

A society that cared about all humanity, and recognized its common human identity, would worry just as much about its impact on others as its impact on members of its own “tribe.” The so-called War on Terror has been a devastating blow against the spirit of shared humanity, deliberately and cynically cultivating an us v. them mentality in the general public. Those of us who see beyond tribal loyalties - like the Code Pink protestors who were forcibly ejected from the Brennan hearing - face a Sisyphean task in overcoming the unnecessary hatreds and suspicions that have multiplied since 9/11.

Non Commercial | 7:39 pm, February 9, 2013 | Link

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Novel — Love as a fundamental principle for humanity

Love as a Fundamental Principle for Humanity

- Categories: Novel

About this sample

Words: 786 |

Published: Jul 17, 2018

Words: 786 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays

Related topics.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

A Plus Topper

Improve your Grades

Humanity Essay | Essay on Humanity for Students and Children in English

February 13, 2024 by Prasanna

Humanity Essay: The definition of humanity would be as quality of being human; the precise nature of man, through which he is differentiated from other beings. But being human does not necessarily mean that an individual possesses humanity. If you want to know the quality of humanity in a person take notice of how they do for people who give nothing back in return to the favour they have offered.

You can also find more Essay Writing articles on events, persons, sports, technology and many more. Like, see many more facts and matters about humanity essay in this link, What is humanity essay.

Long and Short Essays on Humanity for Students and Kids in English

We provide children and students with essay samples on a long essay of 500 words and a short essay of 150 words on the topic “Humanity” for reference.

Long Essay on Humanity 500 Words in English

Long Essay on Humanity is usually given to classes 7, 8, 9, and 10.

When we talk about humanity, there can be various perspectives to look at it. The most common way to understand humanity is through this simple definition – the value of kindness and compassion towards other beings. When we scroll through the pages of history, we come across lots of acts of cruelty being performed by humans, but at the same time, there are many acts of humanity that have been done by few great people.

The thoughts of such great humanitarian have reached the hearts of many people across this planet. To name a few people, such as them are Mother Teresa, Mahatma Gandhi, and Nelson Mandela. These are just a few names with which most of us are familiar with. By taking Mother Teresa, as an example of a humanitarian, we see that she had dedicated her entire life to serving the poor and needy from a nation who she barely had any relation. She saw the people she served for, as humans, a part of her fraternity.

The great Indian poet, Rabindranath Tagore, expressed his strong beliefs on humanity and religion in his Nobel prize-winning piece, Gitanjali. He believed that to have contact with the divine one has to worship humanity. To serve the needy was equivalent to serving the divine power. Humanity was his soul religion. Their ways of life have taught us and will be teaching the future generation what it means to be a human—the act of giving back and coming to aid the ones in need. Humanity comes from the most selfless act, and the compassion one has.

But as we are progressing as a human race into the future, the very meaning of humanity is slowly being corrupted. An act of humanity should not and can never be performed with thoughts or expectations of any personal gain of any form; may it be fame, money or power.

Now we live in a world that, although it has been divided by borders, it is limitless. People have the freedom to travel anywhere, see and experience, anything and every feeling that ever existed, but we still are not satisfied. Nations fight now and then to attain pieces of land in the name of religion or patriotism, while millions of innocent lives are lost, or their homes are destroyed who are caught in the middle of this meaningless quarrels. The amount of divisiveness caused by human-made factors such as religion, race, nationalism, the socio-economic class is causing humanity to disintegrate slowly.

Humanitarian crisis such as the ones in Yemen, Myanmar and Syria has cost the lives of million people. Yet the situation is still far from being resolved. All it needs to save them is for people all across the globe to come ahead and help them. Humanity is just not limited to humans. It’s also caring for the environment, the nature and every living being in this universe. But most humans are regressing to the point that they don’t even care about their surroundings.

In this era of technology and capitalism, we are in desperate need to spread humanity. The global warming, pollution, extinction of species every day could be controlled if we and the future generation understand the meaning of humanity rather than just subduing ourselves to the rat race.

Short Essay on Humanity 150 Words in English

Short Essay on Humanity is usually given to classes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Humanity is an integral part of life which tells that to help other living beings, try to understand others and realize their problems with our perspective and try to help them. For expressing humanity, you don’t need to be a well-off person; everyone can show humanity by helping someone or sharing with them, part of our ration. Every religion in this world tells us about humanity, peace and love.

But humans have always indulged in acts that defy humanity, but we, as a generation, have to rise and strive to live in a world where everybody is living a fair life. And we can attain by acts of humanity. In last I would only say to any religion you belong to be a human first be a human lover strive for humanity as every religion teach us humanity and share your life with others as life is all about living for others and serving humanity that is why “no religion is higher than Humanity.”

10 Lines on Humanity in English

- Humanity is a collective term for all human beings.

- Humanity is also used to describe the value of kindness and compassion towards other beings.

- Humanity is one of the characteristics that differentiate us from other animals.

- Humanity is also a value that binds us together.

- When humans achieve something of importance, it is generally referred to as an achievement for humanity or the human race.

- Humanitarian is a person who wants to promote humanity and human welfare.

- Examples of a few famous Humanitarians are- Mother Teresa, Swami Vivekananda, Nelson Mandela.

- The world at present is facing several humanitarian crises.

- Yemen is the largest humanitarian crisis in the world, with more than 24 million people (some 80% of the population) in need of humanitarian assistance.

- The divided world right now needs the religion of humanity to guide them.

FAQ’s on Humanity Essay

Question 1. What defines humanity?

Answer: The definition of humanity is the entire human race or the characteristics that belong uniquely to human beings, such as kindness, mercy and sympathy.

Question 2. What are the qualities of humanity?

Answer: Qualities that form the foundation of all other human qualities are honesty, integrity, wholeheartedness, courage and self-awareness. These factors define who we are as human beings.

Question 3. How do we show humanity?

Answer: Some says to show humanity is to model genuine empathy, to show gratitude, and to express respect and humility.

- Picture Dictionary

- English Speech

- English Slogans

- English Letter Writing

- English Essay Writing

- English Textbook Answers

- Types of Certificates

- ICSE Solutions

- Selina ICSE Solutions

- ML Aggarwal Solutions

- HSSLive Plus One

- HSSLive Plus Two

- Kerala SSLC

- Distance Education

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

This essay focuses on personal love, or the love of particular persons as such. Part of the philosophical task in understanding personal love is to distinguish the various kinds of personal love. For example, the way in which I love my wife is seemingly very different from the way I love my mother, my child, and my friend. This task has typically proceeded hand-in-hand with philosophical analyses of these kinds of personal love, analyses that in part respond to various puzzles about love. Can love be justified? If so, how? What is the value of personal love? What impact does love have on the autonomy of both the lover and the beloved?

1. Preliminary Distinctions

2. love as union, 3. love as robust concern, 4.1 love as appraisal of value, 4.2 love as bestowal of value, 4.3 an intermediate position, 5.1 love as emotion proper, 5.2 love as emotion complex, 6. the value and justification of love, other internet resources, related entries.

In ordinary conversations, we often say things like the following:

- I love chocolate (or skiing).

- I love doing philosophy (or being a father).

- I love my dog (or cat).

- I love my wife (or mother or child or friend).

However, what is meant by ‘love’ differs from case to case. (1) may be understood as meaning merely that I like this thing or activity very much. In (2) the implication is typically that I find engaging in a certain activity or being a certain kind of person to be a part of my identity and so what makes my life worth living; I might just as well say that I value these. By contrast, (3) and (4) seem to indicate a mode of concern that cannot be neatly assimilated to anything else. Thus, we might understand the sort of love at issue in (4) to be, roughly, a matter of caring about another person as the person she is, for her own sake. (Accordingly, (3) may be understood as a kind of deficient mode of the sort of love we typically reserve for persons.) Philosophical accounts of love have focused primarily on the sort of personal love at issue in (4); such personal love will be the focus here (though see Frankfurt (1999) and Jaworska & Wonderly (2017) for attempts to provide a more general account that applies to non-persons as well).

Even within personal love, philosophers from the ancient Greeks on have traditionally distinguished three notions that can properly be called “love”: eros , agape , and philia . It will be useful to distinguish these three and say something about how contemporary discussions typically blur these distinctions (sometimes intentionally so) or use them for other purposes.

‘ Eros ’ originally meant love in the sense of a kind of passionate desire for an object, typically sexual passion (Liddell et al., 1940). Nygren (1953a,b) describes eros as the “‘love of desire,’ or acquisitive love” and therefore as egocentric (1953b, p. 89). Soble (1989b, 1990) similarly describes eros as “selfish” and as a response to the merits of the beloved—especially the beloved’s goodness or beauty. What is evident in Soble’s description of eros is a shift away from the sexual: to love something in the “erosic” sense (to use the term Soble coins) is to love it in a way that, by being responsive to its merits, is dependent on reasons. Such an understanding of eros is encouraged by Plato’s discussion in the Symposium , in which Socrates understands sexual desire to be a deficient response to physical beauty in particular, a response which ought to be developed into a response to the beauty of a person’s soul and, ultimately, into a response to the form, Beauty.

Soble’s intent in understanding eros to be a reason-dependent sort of love is to articulate a sharp contrast with agape , a sort of love that does not respond to the value of its object. ‘ Agape ’ has come, primarily through the Christian tradition, to mean the sort of love God has for us persons, as well as our love for God and, by extension, of our love for each other—a kind of brotherly love. In the paradigm case of God’s love for us, agape is “spontaneous and unmotivated,” revealing not that we merit that love but that God’s nature is love (Nygren 1953b, p. 85). Rather than responding to antecedent value in its object, agape instead is supposed to create value in its object and therefore to initiate our fellowship with God (pp. 87–88). Consequently, Badhwar (2003, p. 58) characterizes agape as “independent of the loved individual’s fundamental characteristics as the particular person she is”; and Soble (1990, p. 5) infers that agape , in contrast to eros , is therefore not reason dependent but is rationally “incomprehensible,” admitting at best of causal or historical explanations. [ 1 ]

Finally, ‘ philia ’ originally meant a kind of affectionate regard or friendly feeling towards not just one’s friends but also possibly towards family members, business partners, and one’s country at large (Liddell et al., 1940; Cooper, 1977). Like eros , philia is generally (but not universally) understood to be responsive to (good) qualities in one’s beloved. This similarity between eros and philia has led Thomas (1987) to wonder whether the only difference between romantic love and friendship is the sexual involvement of the former—and whether that is adequate to account for the real differences we experience. The distinction between eros and philia becomes harder to draw with Soble’s attempt to diminish the importance of the sexual in eros (1990).

Maintaining the distinctions among eros , agape , and philia becomes even more difficult when faced with contemporary theories of love (including romantic love) and friendship. For, as discussed below, some theories of romantic love understand it along the lines of the agape tradition as creating value in the beloved (cf. Section 4.2 ), and other accounts of romantic love treat sexual activity as merely the expression of what otherwise looks very much like friendship.

Given the focus here on personal love, Christian conceptions of God’s love for persons (and vice versa ) will be omitted, and the distinction between eros and philia will be blurred—as it typically is in contemporary accounts. Instead, the focus here will be on these contemporary understandings of love, including romantic love, understood as an attitude we take towards other persons. [ 2 ]

In providing an account of love, philosophical analyses must be careful to distinguish love from other positive attitudes we take towards persons, such as liking. Intuitively, love differs from such attitudes as liking in terms of its “depth,” and the problem is to elucidate the kind of “depth” we intuitively find love to have. Some analyses do this in part by providing thin conceptions of what liking amounts to. Thus, Singer (1991) and Brown (1987) understand liking to be a matter of desiring, an attitude that at best involves its object having only instrumental (and not intrinsic) value. Yet this seems inadequate: surely there are attitudes towards persons intermediate between having a desire with a person as its object and loving the person. I can care about a person for her own sake and not merely instrumentally, and yet such caring does not on its own amount to (non-deficiently) loving her, for it seems I can care about my dog in exactly the same way, a kind of caring which is insufficiently personal for love.

It is more common to distinguish loving from liking via the intuition that the “depth” of love is to be explained in terms of a notion of identification: to love someone is somehow to identify yourself with him, whereas no such notion of identification is involved in liking. As Nussbaum puts it, “The choice between one potential love and another can feel, and be, like a choice of a way of life, a decision to dedicate oneself to these values rather than these” (1990, p. 328); liking clearly does not have this sort of “depth” (see also Helm 2010; Bagley 2015). Whether love involves some kind of identification, and if so exactly how to understand such identification, is a central bone of contention among the various analyses of love. In particular, Whiting (2013) argues that the appeal to a notion of identification distorts our understanding of the sort of motivation love can provide, for taken literally it implies that love motivates through self -interest rather than through the beloved’s interests. Thus, Whiting argues, central to love is the possibility that love takes the lover “outside herself”, potentially forgetting herself in being moved directly by the interests of the beloved. (Of course, we need not take the notion of identification literally in this way: in identifying with one’s beloved, one might have a concern for one’s beloved that is analogous to one’s concern for oneself; see Helm 2010.)

Another common way to distinguish love from other personal attitudes is in terms of a distinctive kind of evaluation, which itself can account for love’s “depth.” Again, whether love essentially involves a distinctive kind of evaluation, and if so how to make sense of that evaluation, is hotly disputed. Closely related to questions of evaluation are questions of justification: can we justify loving or continuing to love a particular person, and if so, how? For those who think the justification of love is possible, it is common to understand such justification in terms of evaluation, and the answers here affect various accounts’ attempts to make sense of the kind of constancy or commitment love seems to involve, as well as the sense in which love is directed at particular individuals.

In what follows, theories of love are tentatively and hesitantly classified into four types: love as union, love as robust concern, love as valuing, and love as an emotion. It should be clear, however, that particular theories classified under one type sometimes also include, without contradiction, ideas central to other types. The types identified here overlap to some extent, and in some cases classifying particular theories may involve excessive pigeonholing. (Such cases are noted below.) Part of the classificatory problem is that many accounts of love are quasi-reductionistic, understanding love in terms of notions like affection, evaluation, attachment, etc., which themselves never get analyzed. Even when these accounts eschew explicitly reductionistic language, very often little attempt is made to show how one such “aspect” of love is conceptually connected to others. As a result, there is no clear and obvious way to classify particular theories, let alone identify what the relevant classes should be.

The union view claims that love consists in the formation of (or the desire to form) some significant kind of union, a “we.” A central task for union theorists, therefore, is to spell out just what such a “we” comes to—whether it is literally a new entity in the world somehow composed of the lover and the beloved, or whether it is merely metaphorical. Variants of this view perhaps go back to Aristotle (cf. Sherman 1993) and can also be found in Montaigne ([E]) and Hegel (1997); contemporary proponents include Solomon (1981, 1988), Scruton (1986), Nozick (1989), Fisher (1990), and Delaney (1996).

Scruton, writing in particular about romantic love, claims that love exists “just so soon as reciprocity becomes community: that is, just so soon as all distinction between my interests and your interests is overcome” (1986, p. 230). The idea is that the union is a union of concern, so that when I act out of that concern it is not for my sake alone or for your sake alone but for our sake. Fisher (1990) holds a similar, but somewhat more moderate view, claiming that love is a partial fusion of the lovers’ cares, concerns, emotional responses, and actions. What is striking about both Scruton and Fisher is the claim that love requires the actual union of the lovers’ concerns, for it thus becomes clear that they conceive of love not so much as an attitude we take towards another but as a relationship: the distinction between your interests and mine genuinely disappears only when we together come to have shared cares, concerns, etc., and my merely having a certain attitude towards you is not enough for love. This provides content to the notion of a “we” as the (metaphorical?) subject of these shared cares and concerns, and as that for whose sake we act.

Solomon (1988) offers a union view as well, though one that tries “to make new sense out of ‘love’ through a literal rather than metaphoric sense of the ‘fusion’ of two souls” (p. 24, cf. Solomon 1981; however, it is unclear exactly what he means by a “soul” here and so how love can be a “literal” fusion of two souls). What Solomon has in mind is the way in which, through love, the lovers redefine their identities as persons in terms of the relationship: “Love is the concentration and the intensive focus of mutual definition on a single individual, subjecting virtually every personal aspect of one’s self to this process” (1988, p. 197). The result is that lovers come to share the interests, roles, virtues, and so on that constitute what formerly was two individual identities but now has become a shared identity, and they do so in part by each allowing the other to play an important role in defining his own identity.

Nozick (1989) offers a union view that differs from those of Scruton, Fisher, and Solomon in that Nozick thinks that what is necessary for love is merely the desire to form a “we,” together with the desire that your beloved reciprocates. Nonetheless, he claims that this “we” is “a new entity in the world…created by a new web of relationships between [the lovers] which makes them no longer separate” (p. 70). In spelling out this web of relationships, Nozick appeals to the lovers “pooling” not only their well-beings, in the sense that the well-being of each is tied up with that of the other, but also their autonomy, in that “each transfers some previous rights to make certain decisions unilaterally into a joint pool” (p. 71). In addition, Nozick claims, the lovers each acquire a new identity as a part of the “we,” a new identity constituted by their (a) wanting to be perceived publicly as a couple, (b) their attending to their pooled well-being, and (c) their accepting a “certain kind of division of labor” (p. 72):

A person in a we might find himself coming across something interesting to read yet leaving it for the other person, not because he himself would not be interested in it but because the other would be more interested, and one of them reading it is sufficient for it to be registered by the wider identity now shared, the we . [ 3 ]

Opponents of the union view have seized on claims like this as excessive: union theorists, they claim, take too literally the ontological commitments of this notion of a “we.” This leads to two specific criticisms of the union view. The first is that union views do away with individual autonomy. Autonomy, it seems, involves a kind of independence on the part of the autonomous agent, such that she is in control over not only what she does but also who she is, as this is constituted by her interests, values, concerns, etc. However, union views, by doing away with a clear distinction between your interests and mine, thereby undermine this sort of independence and so undermine the autonomy of the lovers. If autonomy is a part of the individual’s good, then, on the union view, love is to this extent bad; so much the worse for the union view (Singer 1994; Soble 1997). Moreover, Singer (1994) argues that a necessary part of having your beloved be the object of your love is respect for your beloved as the particular person she is, and this requires respecting her autonomy.

Union theorists have responded to this objection in several ways. Nozick (1989) seems to think of a loss of autonomy in love as a desirable feature of the sort of union lovers can achieve. Fisher (1990), somewhat more reluctantly, claims that the loss of autonomy in love is an acceptable consequence of love. Yet without further argument these claims seem like mere bullet biting. Solomon (1988, pp. 64ff) describes this “tension” between union and autonomy as “the paradox of love.” However, this a view that Soble (1997) derides: merely to call it a paradox, as Solomon does, is not to face up to the problem.

The second criticism involves a substantive view concerning love. Part of what it is to love someone, these opponents say, is to have concern for him for his sake. However, union views make such concern unintelligible and eliminate the possibility of both selfishness and self-sacrifice, for by doing away with the distinction between my interests and your interests they have in effect turned your interests into mine and vice versa (Soble 1997; see also Blum 1980, 1993). Some advocates of union views see this as a point in their favor: we need to explain how it is I can have concern for people other than myself, and the union view apparently does this by understanding your interests to be part of my own. And Delaney, responding to an apparent tension between our desire to be loved unselfishly (for fear of otherwise being exploited) and our desire to be loved for reasons (which presumably are attractive to our lover and hence have a kind of selfish basis), says (1996, p. 346):

Given my view that the romantic ideal is primarily characterized by a desire to achieve a profound consolidation of needs and interests through the formation of a we , I do not think a little selfishness of the sort described should pose a worry to either party.

The objection, however, lies precisely in this attempt to explain my concern for my beloved egoistically. As Whiting (1991, p. 10) puts it, such an attempt “strikes me as unnecessary and potentially objectionable colonization”: in love, I ought to be concerned with my beloved for her sake, and not because I somehow get something out of it. (This can be true whether my concern with my beloved is merely instrumental to my good or whether it is partly constitutive of my good.)

Although Whiting’s and Soble’s criticisms here succeed against the more radical advocates of the union view, they in part fail to acknowledge the kernel of truth to be gleaned from the idea of union. Whiting’s way of formulating the second objection in terms of an unnecessary egoism in part points to a way out: we persons are in part social creatures, and love is one profound mode of that sociality. Indeed, part of the point of union accounts is to make sense of this social dimension: to make sense of a way in which we can sometimes identify ourselves with others not merely in becoming interdependent with them (as Singer 1994, p. 165, suggests, understanding ‘interdependence’ to be a kind of reciprocal benevolence and respect) but rather in making who we are as persons be constituted in part by those we love (cf., e.g., Rorty 1986/1993; Nussbaum 1990).

Along these lines, Friedman (1998), taking her inspiration in part from Delaney (1996), argues that we should understand the sort of union at issue in love to be a kind of federation of selves:

On the federation model, a third unified entity is constituted by the interaction of the lovers, one which involves the lovers acting in concert across a range of conditions and for a range of purposes. This concerted action, however, does not erase the existence of the two lovers as separable and separate agents with continuing possibilities for the exercise of their own respective agencies. [p. 165]

Given that on this view the lovers do not give up their individual identities, there is no principled reason why the union view cannot make sense of the lover’s concern for her beloved for his sake. [ 4 ] Moreover, Friedman argues, once we construe union as federation, we can see that autonomy is not a zero-sum game; rather, love can both directly enhance the autonomy of each and promote the growth of various skills, like realistic and critical self-evaluation, that foster autonomy.

Nonetheless, this federation model is not without its problems—problems that affect other versions of the union view as well. For if the federation (or the “we”, as on Nozick’s view) is understood as a third entity, we need a clearer account than has been given of its ontological status and how it comes to be. Relevant here is the literature on shared intention and plural subjects. Gilbert (1989, 1996, 2000) has argued that we should take quite seriously the existence of a plural subject as an entity over and above its constituent members. Others, such as Tuomela (1984, 1995), Searle (1990), and Bratman (1999) are more cautious, treating such talk of “us” having an intention as metaphorical.

As this criticism of the union view indicates, many find caring about your beloved for her sake to be a part of what it is to love her. The robust concern view of love takes this to be the central and defining feature of love (cf. Taylor 1976; Newton-Smith 1989; Soble 1990, 1997; LaFollette 1996; Frankfurt 1999; White 2001). As Taylor puts it:

To summarize: if x loves y then x wants to benefit and be with y etc., and he has these wants (or at least some of them) because he believes y has some determinate characteristics ψ in virtue of which he thinks it worth while to benefit and be with y . He regards satisfaction of these wants as an end and not as a means towards some other end. [p. 157]

In conceiving of my love for you as constituted by my concern for you for your sake, the robust concern view rejects the idea, central to the union view, that love is to be understood in terms of the (literal or metaphorical) creation of a “we”: I am the one who has this concern for you, though it is nonetheless disinterested and so not egoistic insofar as it is for your sake rather than for my own. [ 5 ]

At the heart of the robust concern view is the idea that love “is neither affective nor cognitive. It is volitional” (Frankfurt 1999, p. 129; see also Martin 2015). Frankfurt continues:

That a person cares about or that he loves something has less to do with how things make him feel, or with his opinions about them, than with the more or less stable motivational structures that shape his preferences and that guide and limit his conduct.

This account analyzes caring about someone for her sake as a matter of being motivated in certain ways, in part as a response to what happens to one’s beloved. Of course, to understand love in terms of desires is not to leave other emotional responses out in the cold, for these emotions should be understood as consequences of desires. Thus, just as I can be emotionally crushed when one of my strong desires is disappointed, so too I can be emotionally crushed when things similarly go badly for my beloved. In this way Frankfurt (1999) tacitly, and White (2001) more explicitly, acknowledge the way in which my caring for my beloved for her sake results in my identity being transformed through her influence insofar as I become vulnerable to things that happen to her.

Not all robust concern theorists seem to accept this line, however; in particular, Taylor (1976) and Soble (1990) seem to have a strongly individualistic conception of persons that prevents my identity being bound up with my beloved in this sort of way, a kind of view that may seem to undermine the intuitive “depth” that love seems to have. (For more on this point, see Rorty 1986/1993.) In the middle is Stump (2006), who follows Aquinas in understanding love to involve not only the desire for your beloved’s well-being but also a desire for a certain kind of relationship with your beloved—as a parent or spouse or sibling or priest or friend, for example—a relationship within which you share yourself with and connect yourself to your beloved. [ 6 ]

One source of worry about the robust concern view is that it involves too passive an understanding of one’s beloved (Ebels-Duggan 2008). The thought is that on the robust concern view the lover merely tries to discover what the beloved’s well-being consists in and then acts to promote that, potentially by thwarting the beloved’s own efforts when the lover thinks those efforts would harm her well-being. This, however, would be disrespectful and demeaning, not the sort of attitude that love is. What robust concern views seem to miss, Ebels-Duggan suggests, is the way love involves interacting agents, each with a capacity for autonomy the recognition and engagement with which is an essential part of love. In response, advocates of the robust concern view might point out that promoting someone’s well-being normally requires promoting her autonomy (though they may maintain that this need not always be true: that paternalism towards a beloved can sometimes be justified and appropriate as an expression of one’s love). Moreover, we might plausibly think, it is only through the exercise of one’s autonomy that one can define one’s own well-being as a person, so that a lover’s failure to respect the beloved’s autonomy would be a failure to promote her well-being and therefore not an expression of love, contrary to what Ebels-Duggan suggests. Consequently, it might seem, robust concern views can counter this objection by offering an enriched conception of what it is to be a person and so of the well-being of persons.

Another source of worry is that the robust concern view offers too thin a conception of love. By emphasizing robust concern, this view understands other features we think characteristic of love, such as one’s emotional responsiveness to one’s beloved, to be the effects of that concern rather than constituents of it. Thus Velleman (1999) argues that robust concern views, by understanding love merely as a matter of aiming at a particular end (viz., the welfare of one’s beloved), understand love to be merely conative. However, he claims, love can have nothing to do with desires, offering as a counterexample the possibility of loving a troublemaking relation whom you do not want to be with, whose well being you do not want to promote, etc. Similarly, Badhwar (2003) argues that such a “teleological” view of love makes it mysterious how “we can continue to love someone long after death has taken him beyond harm or benefit” (p. 46). Moreover Badhwar argues, if love is essentially a desire, then it implies that we lack something; yet love does not imply this and, indeed, can be felt most strongly at times when we feel our lives most complete and lacking in nothing. Consequently, Velleman and Badhwar conclude, love need not involve any desire or concern for the well-being of one’s beloved.

This conclusion, however, seems too hasty, for such examples can be accommodated within the robust concern view. Thus, the concern for your relative in Velleman’s example can be understood to be present but swamped by other, more powerful desires to avoid him. Indeed, keeping the idea that you want to some degree to benefit him, an idea Velleman rejects, seems to be essential to understanding the conceptual tension between loving someone and not wanting to help him, a tension Velleman does not fully acknowledge. Similarly, continued love for someone who has died can be understood on the robust concern view as parasitic on the former love you had for him when he was still alive: your desires to benefit him get transformed, through your subsequent understanding of the impossibility of doing so, into wishes. [ 7 ] Finally, the idea of concern for your beloved’s well-being need not imply the idea that you lack something, for such concern can be understood in terms of the disposition to be vigilant for occasions when you can come to his aid and consequently to have the relevant occurrent desires. All of this seems fully compatible with the robust concern view.

One might also question whether Velleman and Badhwar make proper use of their examples of loving your meddlesome relation or someone who has died. For although we can understand these as genuine cases of love, they are nonetheless deficient cases and ought therefore be understood as parasitic on the standard cases. Readily to accommodate such deficient cases of love into a philosophical analysis as being on a par with paradigm cases, and to do so without some special justification, is dubious.

Nonetheless, the robust concern view as it stands does not seem properly able to account for the intuitive “depth” of love and so does not seem properly to distinguish loving from liking. Although, as noted above, the robust concern view can begin to make some sense of the way in which the lover’s identity is altered by the beloved, it understands this only an effect of love, and not as a central part of what love consists in.

This vague thought is nicely developed by Wonderly (2017), who emphasizes that in addition to the sort of disinterested concern for another that is central to robust-concern accounts of love, an essential part of at least romantic love is the idea that in loving someone I must find them to be not merely important for their own sake but also important to me . Wonderly (2017) fleshes out what this “importance to me” involves in terms of the idea of attachment (developed in Wonderly 2016) that she argues can make sense of the intimacy and depth of love from within what remains fundamentally a robust-concern account. [ 8 ]

4. Love as Valuing

A third kind of view of love understands love to be a distinctive mode of valuing a person. As the distinction between eros and agape in Section 1 indicates, there are at least two ways to construe this in terms of whether the lover values the beloved because she is valuable, or whether the beloved comes to be valuable to the lover as a result of her loving him. The former view, which understands the lover as appraising the value of the beloved in loving him, is the topic of Section 4.1 , whereas the latter view, which understands her as bestowing value on him, will be discussed in Section 4.2 .

Velleman (1999, 2008) offers an appraisal view of love, understanding love to be fundamentally a matter of acknowledging and responding in a distinctive way to the value of the beloved. (For a very different appraisal view of love, see Kolodny 2003.) Understanding this more fully requires understanding both the kind of value of the beloved to which one responds and the distinctive kind of response to such value that love is. Nonetheless, it should be clear that what makes an account be an appraisal view of love is not the mere fact that love is understood to involve appraisal; many other accounts do so, and it is typical of robust concern accounts, for example (cf. the quote from Taylor above , Section 3 ). Rather, appraisal views are distinctive in understanding love to consist in that appraisal.

In articulating the kind of value love involves, Velleman, following Kant, distinguishes dignity from price. To have a price , as the economic metaphor suggests, is to have a value that can be compared to the value of other things with prices, such that it is intelligible to exchange without loss items of the same value. By contrast, to have dignity is to have a value such that comparisons of relative value become meaningless. Material goods are normally understood to have prices, but we persons have dignity: no substitution of one person for another can preserve exactly the same value, for something of incomparable worth would be lost (and gained) in such a substitution.

On this Kantian view, our dignity as persons consists in our rational nature: our capacity both to be actuated by reasons that we autonomously provide ourselves in setting our own ends and to respond appropriately to the intrinsic values we discover in the world. Consequently, one important way in which we exercise our rational natures is to respond with respect to the dignity of other persons (a dignity that consists in part in their capacity for respect): respect just is the required minimal response to the dignity of persons. What makes a response to a person be that of respect, Velleman claims, still following Kant, is that it “arrests our self-love” and thereby prevents us from treating him as a means to our ends (p. 360).

Given this, Velleman claims that love is similarly a response to the dignity of persons, and as such it is the dignity of the object of our love that justifies that love. However, love and respect are different kinds of responses to the same value. For love arrests not our self-love but rather

our tendencies toward emotional self-protection from another person, tendencies to draw ourselves in and close ourselves off from being affected by him. Love disarms our emotional defenses; it makes us vulnerable to the other. [1999, p. 361]

This means that the concern, attraction, sympathy, etc. that we normally associate with love are not constituents of love but are rather its normal effects, and love can remain without them (as in the case of the love for a meddlesome relative one cannot stand being around). Moreover, this provides Velleman with a clear account of the intuitive “depth” of love: it is essentially a response to persons as such, and to say that you love your dog is therefore to be confused.

Of course, we do not respond with love to the dignity of every person we meet, nor are we somehow required to: love, as the disarming of our emotional defenses in a way that makes us especially vulnerable to another, is the optional maximal response to others’ dignity. What, then, explains the selectivity of love—why I love some people and not others? The answer lies in the contingent fit between the way some people behaviorally express their dignity as persons and the way I happen to respond to those expressions by becoming emotionally vulnerable to them. The right sort of fit makes someone “lovable” by me (1999, p. 372), and my responding with love in these cases is a matter of my “really seeing” this person in a way that I fail to do with others who do not fit with me in this way. By ‘lovable’ here Velleman seems to mean able to be loved, not worthy of being loved, for nothing Velleman says here speaks to a question about the justification of my loving this person rather than that. Rather, what he offers is an explanation of the selectivity of my love, an explanation that as a matter of fact makes my response be that of love rather than mere respect.

This understanding of the selectivity of love as something that can be explained but not justified is potentially troubling. For we ordinarily think we can justify not only my loving you rather than someone else but also and more importantly the constancy of my love: my continuing to love you even as you change in certain fundamental ways (but not others). As Delaney (1996, p. 347) puts the worry about constancy:

while you seem to want it to be true that, were you to become a schmuck, your lover would continue to love you,…you also want it to be the case that your lover would never love a schmuck.

The issue here is not merely that we can offer explanations of the selectivity of my love, of why I do not love schmucks; rather, at issue is the discernment of love, of loving and continuing to love for good reasons as well as of ceasing to love for good reasons. To have these good reasons seems to involve attributing different values to you now rather than formerly or rather than to someone else, yet this is precisely what Velleman denies is the case in making the distinction between love and respect the way he does.

It is also questionable whether Velleman can even explain the selectivity of love in terms of the “fit” between your expressions and my sensitivities. For the relevant sensitivities on my part are emotional sensitivities: the lowering of my emotional defenses and so becoming emotionally vulnerable to you. Thus, I become vulnerable to the harms (or goods) that befall you and so sympathetically feel your pain (or joy). Such emotions are themselves assessable for warrant, and now we can ask why my disappointment that you lost the race is warranted, but my being disappointed that a mere stranger lost would not be warranted. The intuitive answer is that I love you but not him. However, this answer is unavailable to Velleman, because he thinks that what makes my response to your dignity that of love rather than respect is precisely that I feel such emotions, and to appeal to my love in explaining the emotions therefore seems viciously circular.

Although these problems are specific to Velleman’s account, the difficulty can be generalized to any appraisal account of love (such as that offered in Kolodny 2003). For if love is an appraisal, it needs to be distinguished from other forms of appraisal, including our evaluative judgments. On the one hand, to try to distinguish love as an appraisal from other appraisals in terms of love’s having certain effects on our emotional and motivational life (as on Velleman’s account) is unsatisfying because it ignores part of what needs to be explained: why the appraisal of love has these effects and yet judgments with the same evaluative content do not. Indeed, this question is crucial if we are to understand the intuitive “depth” of love, for without an answer to this question we do not understand why love should have the kind of centrality in our lives it manifestly does. [ 9 ] On the other hand, to bundle this emotional component into the appraisal itself would be to turn the view into either the robust concern view ( Section 3 ) or a variant of the emotion view ( Section 5.1 ).

In contrast to Velleman, Singer (1991, 1994, 2009) understands love to be fundamentally a matter of bestowing value on the beloved. To bestow value on another is to project a kind of intrinsic value onto him. Indeed, this fact about love is supposed to distinguish love from liking: “Love is an attitude with no clear objective,” whereas liking is inherently teleological (1991, p. 272). As such, there are no standards of correctness for bestowing such value, and this is how love differs from other personal attitudes like gratitude, generosity, and condescension: “love…confers importance no matter what the object is worth” (p. 273). Consequently, Singer thinks, love is not an attitude that can be justified in any way.

What is it, exactly, to bestow this kind of value on someone? It is, Singer says, a kind of attachment and commitment to the beloved, in which one comes to treat him as an end in himself and so to respond to his ends, interests, concerns, etc. as having value for their own sake. This means in part that the bestowal of value reveals itself “by caring about the needs and interests of the beloved, by wishing to benefit or protect her, by delighting in her achievements,” etc. (p. 270). This sounds very much like the robust concern view, yet the bestowal view differs in understanding such robust concern to be the effect of the bestowal of value that is love rather than itself what constitutes love: in bestowing value on my beloved, I make him be valuable in such a way that I ought to respond with robust concern.

For it to be intelligible that I have bestowed value on someone, I must therefore respond appropriately to him as valuable, and this requires having some sense of what his well-being is and of what affects that well-being positively or negatively. Yet having this sense requires in turn knowing what his strengths and deficiencies are, and this is a matter of appraising him in various ways. Bestowal thus presupposes a kind of appraisal, as a way of “really seeing” the beloved and attending to him. Nonetheless, Singer claims, it is the bestowal that is primary for understanding what love consists in: the appraisal is required only so that the commitment to one’s beloved and his value as thus bestowed has practical import and is not “a blind submission to some unknown being” (1991, p. 272; see also Singer 1994, pp. 139ff).

Singer is walking a tightrope in trying to make room for appraisal in his account of love. Insofar as the account is fundamentally a bestowal account, Singer claims that love cannot be justified, that we bestow the relevant kind of value “gratuitously.” This suggests that love is blind, that it does not matter what our beloved is like, which seems patently false. Singer tries to avoid this conclusion by appealing to the role of appraisal: it is only because we appraise another as having certain virtues and vices that we come to bestow value on him. Yet the “because” here, since it cannot justify the bestowal, is at best a kind of contingent causal explanation. [ 10 ] In this respect, Singer’s account of the selectivity of love is much the same as Velleman’s, and it is liable to the same criticism: it makes unintelligible the way in which our love can be discerning for better or worse reasons. Indeed, this failure to make sense of the idea that love can be justified is a problem for any bestowal view. For either (a) a bestowal itself cannot be justified (as on Singer’s account), in which case the justification of love is impossible, or (b) a bestowal can be justified, in which case it is hard to make sense of value as being bestowed rather than there antecedently in the object as the grounds of that “bestowal.”

More generally, a proponent of the bestowal view needs to be much clearer than Singer is in articulating precisely what a bestowal is. What is the value that I create in a bestowal, and how can my bestowal create it? On a crude Humean view, the answer might be that the value is something projected onto the world through my pro-attitudes, like desire. Yet such a view would be inadequate, since the projected value, being relative to a particular individual, would do no theoretical work, and the account would essentially be a variant of the robust concern view. Moreover, in providing a bestowal account of love, care is needed to distinguish love from other personal attitudes such as admiration and respect: do these other attitudes involve bestowal? If so, how does the bestowal in these cases differ from the bestowal of love? If not, why not, and what is so special about love that requires a fundamentally different evaluative attitude than admiration and respect?

Nonetheless, there is a kernel of truth in the bestowal view: there is surely something right about the idea that love is creative and not merely a response to antecedent value, and accounts of love that understand the kind of evaluation implicit in love merely in terms of appraisal seem to be missing something. Precisely what may be missed will be discussed below in Section 6 .

Perhaps there is room for an understanding of love and its relation to value that is intermediate between appraisal and bestowal accounts. After all, if we think of appraisal as something like perception, a matter of responding to what is out there in the world, and of bestowal as something like action, a matter of doing something and creating something, we should recognize that the responsiveness central to appraisal may itself depend on our active, creative choices. Thus, just as we must recognize that ordinary perception depends on our actively directing our attention and deploying concepts, interpretations, and even arguments in order to perceive things accurately, so too we might think our vision of our beloved’s valuable properties that is love also depends on our actively attending to and interpreting him. Something like this is Jollimore’s view (2011). According to Jollimore, in loving someone we actively attend to his valuable properties in a way that we take to provide us with reasons to treat him preferentially. Although we may acknowledge that others might have such properties even to a greater degree than our beloved does, we do not attend to and appreciate such properties in others in the same way we do those in our beloveds; indeed, we find our appreciation of our beloved’s valuable properties to “silence” our similar appreciation of those in others. (In this way, Jollimore thinks, we can solve the problem of fungibility, discussed below in Section 6 .) Likewise, in perceiving our beloved’s actions and character, we do so through the lens of such an appreciation, which will tend as to “silence” interpretations inconsistent with that appreciation. In this way, love involves finding one’s beloved to be valuable in a way that involves elements of both appraisal (insofar as one must thereby be responsive to valuable properties one’s beloved really has) and bestowal (insofar as through one’s attention and committed appreciation of these properties they come to have special significance for one).

One might object that this conception of love as silencing the special value of others or to negative interpretations of our beloveds is irrational in a way that love is not. For, it might seem, such “silencing” is merely a matter of our blinding ourselves to how things really are. Yet Jollimore claims that this sense in which love is blind is not objectionable, for (a) we can still intellectually recognize the things that love’s vision silences, and (b) there really is no impartial perspective we can take on the values things have, and love is one appropriate sort of partial perspective from which the value of persons can be manifest. Nonetheless, one might wonder about whether that perspective of love itself can be distorted and what the norms are in terms of which such distortions are intelligible. Furthermore, it may seem that Jollimore’s attempt to reconcile appraisal and bestowal fails to appreciate the underlying metaphysical difficulty: appraisal is a response to value that is antecedently there, whereas bestowal is the creation of value that was not antecedently there. Consequently, it might seem, appraisal and bestowal are mutually exclusive and cannot be reconciled in the way Jollimore hopes.

Whereas Jollimore tries to combine separate elements of appraisal and of bestowal in a single account, Helm (2010) and Bagley (2015) offer accounts that reject the metaphysical presupposition that values must be either prior to love (as with appraisal) or posterior to love (as with bestowal), instead understanding the love and the values to emerge simultaneously. Thus, Helm presents a detailed account of valuing in terms of the emotions, arguing that while we can understand individual emotions as appraisals , responding to values already their in their objects, these values are bestowed on those objects via broad, holistic patterns of emotions. How this amounts to an account of love will be discussed in Section 5.2 , below. Bagley (2015) instead appeals to a metaphor of improvisation, arguing that just as jazz musicians jointly make determinate the content of their musical ideas through on-going processes of their expression, so too lovers jointly engage in “deep improvisation”, thereby working out of their values and identities through the on-going process of living their lives together. These values are thus something the lovers jointly construct through the process of recognizing and responding to those very values. To love someone is thus to engage with them as partners in such “deep improvisation”. (This account is similar to Helm (2008, 2010)’s account of plural agency, which he uses to provide an account of friendship and other loving relationships; see the discussion of shared activity in the entry on friendship .)

5. Emotion Views

Given these problems with the accounts of love as valuing, perhaps we should turn to the emotions. For emotions just are responses to objects that combine evaluation, motivation, and a kind of phenomenology, all central features of the attitude of love.

Many accounts of love claim that it is an emotion; these include: Wollheim 1984, Rorty 1986/1993, Brown 1987, Hamlyn 1989, Baier 1991, and Badhwar 2003. [ 11 ] Thus, Hamlyn (1989, p. 219) says:

It would not be a plausible move to defend any theory of the emotions to which love and hate seemed exceptions by saying that love and hate are after all not emotions. I have heard this said, but it does seem to me a desperate move to make. If love and hate are not emotions what is?