An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.37(1); 2014 May

The Evidence-Based Practice of Applied Behavior Analysis

Timothy a. slocum.

Utah State University, Logan, UT USA

Ronnie Detrich

Wing Institute, Oakland, CA USA

Susan M. Wilczynski

Ball State University, Muncie, IN USA

Trina D. Spencer

Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ USA

Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR USA

Katie Wolfe

University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC USA

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is a model of professional decision-making in which practitioners integrate the best available evidence with client values/context and clinical expertise in order to provide services for their clients. This framework provides behavior analysts with a structure for pervasive use of the best available evidence in the complex settings in which they work. This structure recognizes the need for clear and explicit understanding of the strength of evidence supporting intervention options, the important contextual factors including client values that contribute to decision making, and the key role of clinical expertise in the conceptualization, intervention, and evaluation of cases. Opening the discussion of EBP in this journal, Smith ( The Behavior Analyst, 36 , 7–33, 2013 ) raised several key issues related to EBP and applied behavior analysis (ABA). The purpose of this paper is to respond to Smith’s arguments and extend the discussion of the relevant issues. Although we support many of Smith’s ( The Behavior Analyst, 36 , 7–33, 2013 ) points, we contend that Smith’s definition of EBP is significantly narrower than definitions that are used in professions with long histories of EBP and that this narrowness conflicts with the principles that drive applied behavior analytic practice. We offer a definition and framework for EBP that aligns with the foundations of ABA and is consistent with well-established definitions of EBP in medicine, psychology, and other professions. In addition to supporting the systematic use of research evidence in behavior analytic decision making, this definition can promote clear communication about treatment decisions across disciplines and with important outside institutions such as insurance companies and granting agencies.

Almost 45 years ago, Baer et al. ( 1968 ) described a new discipline—applied behavior analysis (ABA). This discipline was distinguished from the experimental analysis of behavior by its focus on social impact (i.e., solving socially important problems in socially important settings). ABA has produced remarkably powerful interventions in fields such as education, developmental disabilities and autism, clinical psychology, behavioral medicine, organizational behavior management, and a host of other fields and populations. Behavior analysts have long recognized that developing interventions capable of improving client behavior solves only one part of the problem. The problem of broad social impact must be solved by having interventions implemented effectively in socially important settings and at scales of social importance (Baer et al. 1987 ; Horner et al. 2005b ; McIntosh et al. 2010 ). This latter set of challenges has proved to be more difficult. In many cases, demonstrations of effectiveness are not sufficient to produce broad adoption and careful implementation of these procedures. Key decision makers may be more influenced by variables other than the increases and decreases in the behaviors of our clients. In addition, even when client behavior is a very powerful factor in decision making, it does not guarantee that empirical data will be the basis for treatment selection; anecdotes, appeals to philosophy, or marketing have been given priority over evidence of outcomes (Carnine 1992 ; Polsgrove 2003 ).

Across settings in which behavior analysts work, there has been a persistent gap between what is known from research and what is actually implemented in practice. Behavior analysts have been concerned with the failed adoption of research-based practices for years (Baer et al. 1987 ). Even in the fields in which behavior analysts have produced powerful interventions, the vast majority of current practice fails to take advantage of them.

Behavior analysts have not been alone in recognizing serious problems with the quality of interventions used employed in practice settings. In the 1960s, many within the medical field recognized a serious research-to-practice gap. Studies suggested that a relatively small percentage (estimates range from 10 to 25 %) of medical treatment decisions were based on high-quality evidence (Goodman 2003 ). This raised the troubling question of what basis was used for the remaining decisions if it was not high-quality evidence. These concerns led to the development of evidence-based practice (EBP) of medicine (Goodman 2003 ; Sackett et al. 1996 ).

The research-to-practice gap appears to be universal across professions. For example, Kazdin ( 2000 ) has reported that less than 10 % of the child and adolescent mental health treatments reported in the professional literature have been systematically evaluated and found to be effective and those that have not been evaluated are more likely to be adopted in practice settings. In recognition of their own research-to-practice gaps, numerous professions have adopted an EBP framework. Nursing and other areas of health care, social work, clinical and educational psychology, speech and language pathology, and many others have adopted this framework and adapted it to the specific needs of their discipline to help guide decision-making. Not only have EBP frameworks been helping to structure professional practice, but they have also been used to guide federal policy. With the passage of No Child Left Behind ( 2002 ) and the reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act ( 2005 ), the federal department of education has aligned itself with the EBP movement. A recent memorandum from the federal Office of Management and Budget instructed agencies to consider evidence of effectiveness when awarding funds, increase the use of evidence in competitions, and to encourage widespread program evaluation (Zients 2012 ). The memo, which used the term evidence-based practice extensively, stated: “Where evidence is strong, we should act on it. Where evidence is suggestive, we should consider it. Where evidence is weak, we should build the knowledge to support better decisions in the future” (Zients 2012 , p. 1).

EBP is more broadly an effort to improve decision-making in applied settings by explicitly articulating the central role of evidence in these decisions and thereby improving outcomes. It addresses one of the long-standing challenges for ABA; the need to effectively support and disseminate interventions in the larger social systems in which our work is embedded. In particular, EBP addresses the fact that many decision-makers are not sufficiently influenced by the best evidence that is relevant to important decisions. EBP is an explicit statement of one of ABA’s core tenets—a commitment to evidence-based decision-making. Given that the EBP framework is well established in many disciplines closely related to ABA and in the larger institutional contexts in which we operate (e.g., federal policy and funding agencies), aligning ABA with EBP offers an opportunity for behavior analysts to work more effectively within broader social systems.

Discussion of issues related to EBP in ABA has taken place across several years. Researchers have extensively discussed methods for identifying well-supported treatments (e.g., Horner et al. 2005a ; Kratochwill et al. 2010 ), and systematically reviewed the evidence to identify these treatments (e.g., Maggin et al. 2011 ; National Autism Center 2009 ). However, until recently, discussion of an explicit definition of EBP in ABA has been limited to conference papers (e.g., Detrich 2009 ). Smith ( 2013 ) opened a discussion of the definition and critical features of EBP of ABA in the pages of The Behavior Analyst . In his thought-provoking article, Smith raised many important points that deserve serious discussion as the field moves toward a clear vision of EBP of ABA. Most importantly, Smith ( 2013 ) argued that behavior analysts must carefully consider how EBP is to be defined and understood by researchers and practitioners of behavior analysis.

Definitions Matter

We find much to agree with in Smith’s paper, and we will describe these points of agreement below. However, we have a core disagreement with Smith concerning the vision of what EBP is and how it might enhance and expand the effective practice of ABA. As behavior analysts know, definitions matter. A well-conceived definition can promote conceptual understanding and set the context for effective action. Conversely, a poor definition or confusion about definitions hinders clear understanding, communication, and action.

In providing a basis for his definition of EBP, Smith refers to definitions in professions that have well-developed conceptions of EBP. He quotes the American Psychological Association (APA) ( 2005 ) definition (which we quote here more extensively than he did):

Evidence-based practice in psychology (EBPP) is the integration of the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of patient characteristics, culture, and preferences. This definition of EBPP closely parallels the definition of evidence-based practice adopted by the Institute of Medicine ( 2001 , p. 147) as adapted from Sackett et al. ( 2000 ): “Evidence-based practice is the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.” The purpose of EBPP is to promote effective psychological practice and enhance public health by applying empirically supported principles of psychological assessment, case formulation, therapeutic relationship, and intervention.

The key to understanding this definition is to note how APA and the Institute of Medicine use the word practice . Clearly, practice does not refer to an intervention; instead, it references one’s professional behavior. This is the sense in which one might speak of the professional practice of behavior analysis. American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force of Evidence-Based Practice ( 2006 ) further elaborates this point:

It is important to clarify the relation between EBPP and empirically supported treatments (ESTs)…. ESTs are specific psychological treatments that have been shown to be efficacious in controlled clinical trials, whereas EBPP encompasses a broader range of clinical activities (e.g., psychological assessment, case formulation, therapy relationships). As such, EBPP articulates a decision-making process for integrating multiple streams of research evidence—including but not limited to RCTs—into the intervention process. (p. 273)

In contrast, Smith defined EBP not as a decision-making process but as a set of interventions that have been shown to be efficacious through rigorous research. He stated:

An evidence-based practice is a service that helps solve a consumer’s problem. Thus it is likely to be an integrated package of procedures, operationalized in a manual, and validated in studies of socially meaningful outcomes, usually with group designs. (p. 27).

Smith’s EBP is what APA has clearly labeled an empirically supported treatment . This is a common misconception found in conversation and in published articles (e.g., Cook and Cook 2013 ) but at odds with formal definitions provided by many professional organizations; definitions which result from extensive consideration and debate by representative leaders of each professional field (e.g., APA 2005 ; American Occupational Therapy Association 2008 ; American Speech-Language Hearing Association 2005 ; Institute of Medicine 2001 ).

Before entering into the discussion of a useful definition of EBP of ABA, we should clarify the functions that we believe a useful definition of EBP should perform. First, a useful definition should align with the philosophical tenets of ABA, support the most effective current practice of ABA, and contribute to further improvement of ABA practice. A definition that is in conflict with the foundations of ABA or detracts from effective practice clearly would be counterproductive. Second, a useful definition of EBP of ABA should enhance social support for ABA practice by describing its empirical basis and decision-making processes in a way that is understandable to professions that already have well-established definitions of EBP. A definition that corresponds with the fundamental components of EBP in other fields would promote ABA practice by improving communication with external audiences. This improved communication is critical in the interdisciplinary contexts in which behavior analysts often practice and for legitimacy among those familiar with EBP who often control local contingencies (e.g., policy makers and funding agencies).

Based on these functions, we propose the following definition: Evidence-based practice of applied behavior analysis is a decision-making process that integrates (a) the best available evidence with (b) clinical expertise and (c) client values and context. This definition positions EBP as a pervasive feature of all professional decision-making by a behavior analyst with respect to client services; it is not limited to a narrowly restricted set of situations or decisions. The definition asserts that the best available evidence should be a primary influence on all decision-making related to services for clients (e.g., intervention selection, progress monitoring, etc.). It also recognizes that evidence cannot be the sole basis for a decision; effective decision-making in a discipline as complex as ABA requires clinical expertise in identifying, defining, and analyzing problems, determining what evidence is relevant, and deciding how it should be applied. In the absence of this decision-making framework, practitioners of ABA would be conceptualized as behavioral technicians rather than analysts. Further, the definition of EBP of ABA includes client values and context. Decision-making is necessarily based on a set of values that determine the goals that are to be pursued and the means that are appropriate to achieve them. Context is included in recognition of the fact that the effectiveness of an intervention is highly dependent upon the context in which it is implemented. The definition asserts that effective decision-making must be informed by important contextual factors. We elaborate on each component of the definition below, but first we contrast our definition with that offered by Smith ( 2013 ).

Although Smith ( 2013 ) made brief reference to the other critical components of EBP, he framed EBP as a list of multicomponent interventions that can claim a sufficient level of research support. We agree with his argument that such lists are valuable resources for practitioners and therefore developing them should be a goal of researchers. However, such lists are not, by themselves , a powerful means of improving the effectiveness of behavior analytic practice. The vast majority of decisions faced in the practice of behavior analysis cannot be made by implementing the kind of manualized, multicomponent treatment packages described by Smith.

There are a number of reasons a list of interventions is not an adequate basis for EBP of ABA. First, there are few interventions that qualify as “practices” under Smith’s definition. For example, when discussing the importance of manuals for operationalizing treatments, Smith stated that the requirement that a “practice” be based on a manual, “sharply reduces the number of ABA approaches that can be regarded as evidence based. Of the 11 interventions for ASD identified in the NAC ( 2009 ) report, only the three that have been standardized in manuals might be considered to be practices, and even these may be incomplete” (p. 18). Thus, although the example referenced the autism treatment literature, it seems apparent that even a loose interpretation of this particular criterion would leave all practitioners with a highly restricted number of intervention options.

Second, even if more “practices” were developed and validated, many consumers cannot be well served with existing multicomponent packages. In order to meet their clients’ needs, behavior analysts must be able to selectively implement focused interventions alone or in combination. This flexibility is necessary to meet the diverse needs of their clients and to minimize the response demands on direct care providers or staff, who are less likely to implement a complicated intervention with fidelity (Riley-Tillman and Chafouleas 2003 ).

Third, the strategy of assembling a list of treatments and describing these as “practices” severely limits the ways in which research findings are used by practitioners. With the list approach to defining EBP, research only impacts practice by placing an intervention on a list when a specific criteria has been met. Thus, any research on an intervention that is not sufficiently broad or manualized to qualify as a “practice” has no influence on EBP. Similarly, a research study that shows clear results but is not part of a sufficient body of support for an intervention would also have no influence. A study that provides suggestive results but is not methodologically strong enough to be definitive would have no influence, even if it were the only study that is relevant to a given problem.

The primary problem with a list approach is that it does not provide a strong framework that directs practitioners to include the best available evidence in all of their professional decision-making. Too often, practitioners who consult such lists find that no interventions relevant to their specific case have been validated as “evidence-based” and therefore EBP is irrelevant. In contrast, definitions of EBP as a decision-making process can provide a robust framework for including research evidence along with clinical expertise and client values and context in the practice of behavior analysis. In the next sections, we explore the components of this definition in more detail.

Best Available Evidence

The term “best available evidence” occupies a critical and central place in the definition and concept of EBP; this aligns with the fundamental reliance on scientific research that is one of the core tenets of ABA. The Behavior Analyst Certification Board ( 2010 ) Guidelines for Responsible Conduct for Behavior Analysts repeatedly affirm ways in which behavior analysts should base their professional conduct on the best available evidence. For example:

Behavior analysts rely on scientifically and professionally derived knowledge when making scientific or professional judgments in human service provision, or when engaging in scholarly or professional endeavors.

- The behavior analyst always has the responsibility to recommend scientifically supported most effective treatment procedures. Effective treatment procedures have been validated as having both long-term and short-term benefits to clients and society.

- Clients have a right to effective treatment (i.e., based on the research literature and adapted to the individual client).

A Continuum of Evidence Quality

The term best implies that evidence can be of varying quality, and that better quality evidence is preferred over lower quality evidence. Quality of evidence for informing a specific practical question involves two dimensions: (a) relevance of the evidence and (b) certainty of the evidence.

The dimension of relevance recognizes that some evidence is more germane to a particular decision than is other evidence. This idea is similar to the concept of external validity. External validity refers to the degree to which research results apply to a range of applied situations whereas relevance refers to the degree to which research results apply to a specific applied situation. In general, evidence is more relevant when it matches the particular situation in terms of (a) important characteristics of the clients, (b) specific treatments or interventions under consideration, (c) outcomes or target behaviors including their functions, and (d) contextual variables such as the physical and social environment, staff skills, and the capacity of the organization. Unless all conditions match perfectly, behavior analysts are necessarily required to use their expertise to determine the applicability of the scientific evidence to each unique clinical situation. Evidence based on functionally similar situations is preferred over evidence based on situations that share fewer important characteristics with the specific practice situation. However, functional similarity between a study or set of studies and a particular applied problem is not always obvious.

The dimension of certainty of evidence recognizes that some evidence provides stronger support for claims that a particular intervention produced a specific result. Any instance of evidence can be evaluated for its methodological rigor or internal validity (i.e., the degree to which it provides strong support for the claim of effectiveness and rules out alternative explanations). Anecdotes are clearly weaker than more systematic observations, and well-controlled experiments provide the strongest evidence. Methodological rigor extends to the quality of the dependent measure, treatment fidelity, and other variables of interest (e.g., maintenance of skill acquisition), all of which influence the certainty of evidence. But the internal validity of any particular study is not the only variable influencing the certainty of evidence; the quantity of evidence supporting a claim is also critical to its certainty. Both systematic and direct replication are vital for strengthening claims of effectiveness (Johnston and Pennypacker 1993 ; Sidman 1960 ). Certainty of evidence is based on both the rigor of each bit of evidence and the degree to which the findings have been consistently replicated. Although these issues are simple in principle, operationalizing and measuring rigor of research is extremely complex. Numerous quality appraisal systems for both group and single-subject research have been proposed and used in systematic reviews (see below for more detail).

Under ideal circumstances, consistently high-quality evidence that closely matches the specifics of the practice situation is available; unfortunately, this is not always the case, and evidence-based practitioners of ABA must proceed despite an imperfect evidence base. The mandate to use the best available evidence specifies that the practitioner make decisions based on the best evidence that is available. Although this statement may seem rather obvious, the point is worth underscoring because the implications are highly relevant to behavior analysts. In an area with considerable high-quality relevant research, the standards for evidence should be quite high. But in an area with more limited research, the practitioner should take advantage of the best evidence that is available. This may require tentative reliance on research that is somewhat weaker or is only indirectly relevant to the specific situation at hand. For example, ideally, evidence-based practitioners of ABA would rely on well-controlled experimental results that have been replicated with the precise population with whom they are working. However, if this kind of evidence is not available, they might have to make decisions based on a single study that involves a similar but not identical population.

This idea of using the best of the available evidence is very different from one of using only extremely high-quality evidence (i.e., empirically supported treatments). If we limit EBP to considering only the highest quality evidence, we leave the practitioner with no guidance in the numerous situations in which high-quality and directly relevant evidence (i.e., precise matching of setting, function, behavior, motivating operations and precise procedures) simply does not exist. This approach would lead to a form of EBP that is irrelevant to the majority of decisions that a behavior analyst must make on a daily basis. Instead, our proposed definition of EBP asserts that the practitioner should be informed by the best evidence that is available.

Expanding Research on Utility of Treatments

Smith ( 2013 ) argued that the research methods used by behavior analysts to evaluate these treatments should be expanded to more comprehensively describe the utility of interventions. He suggested that too much ABA research is conducted in settings that do not approximate typical service settings, optimizing experimental control at the expense of external validity. Along this same line of reasoning, he noted that it is important to test the generality of effects across clients and identify variables that predict differential effectiveness. He suggested systematically reporting results from all research participants (e.g., the intent-to-treat model), and purposive selection of participants would provide a more complete account of the situations in which treatments are successful and those in which they are unsuccessful. Smith argued that researchers should include more distal and socially important outcomes because with a narrow target “behavior may change, but remain a problem for the individual or may be only a small component of a much larger cluster of problems such as addiction or delinquency.” He pointed out that in order to best support effective practice, research must demonstrate that an intervention produces or contributes to producing the socially important outcomes that would cause a consumer to say that the problem is solved.

Further, Smith argues that many of the questions most relevant to EBP—questions about the likely outcomes of a treatment when applied in a particular type of situation—are well suited to group research designs. He argued that RCTs are likely to be necessary within a program of research because:

most problems pose important actuarial questions (e.g., determining whether an intervention package is more effective than community treatment as usual; deciding whether to invest in one intervention package or another, both, or neither; and determining whether the long-term benefits justify the resources devoted to the intervention)…. A particularly important actuarial issue centers on the identification of the conditions under which the intervention is most likely to be effective. (p. 23)

We agree that selection of research methods should be driven by the kinds of questions being asked and that group research designs are the methods of choice for some types of questions that are central to EBP. Therefore, we support Smith’s call for increased use of group research designs within ABA. If practice decisions are to be informed by the best available evidence, we must take advantage of both group and single-subject designs. However, we disagree with Smith’s statement that EBP should be limited to treatments that are validated “usually with group designs” (Smith, p. 27). Practitioners should be supported by reviews of research that draw from all of the available evidence and provide the best recommendations possible given the state of knowledge on the particular question. In most areas of behavior analytic practice, single-subject research makes up a large portion of the best available evidence. The Institute for Education Science (IES) has recognized the contribution single case designs can make toward identifying effective practices and has recently established standards for evaluating the quality of single case design studies (Institute of Educational Sciences, n.d. ; Kratochwill et al. 2013 ).

Classes of Evidence

Identifying the best available evidence to inform specific practice decisions is extremely complex, and no single currently available source of evidence can adequately inform all aspects of practice. Therefore, we outline a number of strategies for identifying and summarizing evidence in ways that can support the EBP of ABA. We do not intend to cover all sources of evidence comprehensively, but merely outline some of the options available to behavior analysts.

Empirically Supported Treatment Reviews

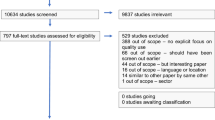

Empirically supported treatments (EST) are identified through a particular form of systematic literature review. Systematic reviews bring a rigorous methodology to the process of reviewing research. The development and use of these methods are, in part, a response to the recognition that the process of reviewing the literature is subject to threats to validity. The systematic review process is characterized by explicitly stated and replicable methods for (a) searching for studies, (b) screening studies for relevance to the review question, (c) appraising the methodological quality of studies, (d) describing outcomes from each study, and (e) determining the degree to which the treatment (or treatments) is supported by the research. When the evidence in support of a treatment is plentiful and of high quality, the treatment generally earns the status of an EST. Many systematic reviews, however, find that no intervention for a particular problem has sufficient evidence to qualify as an EST.

Well-known organizations in medicine (e.g., Cochrane Collaboration), education (e.g., What Works Clearinghouse), and mental health (e.g., National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices) conduct EST reviews. Until recently, systematic reviews have focused nearly exclusively on group research; however, systematic reviews of single-subject research are quickly becoming more common and more sophisticated (e.g., Carr 2009 ; NAC 2009 ; Maggin et al. 2012 ).

Systematic reviews for EST status is one important way to summarize the best available evidence because it can give a relatively objective evaluation of the strength of the research literature supporting a particular intervention. But systematic reviews are not infallible; as with all other research and evaluation methods, they require skillful application and are subject to threats to validity. The results of reviews can change dramatically based on seemingly minor changes in operational definitions and procedures for locating articles, screening for relevance, describing treatments, appraising methodological quality, describing outcomes, summarizing outcomes for the body of research as a whole, and rating the degree to which an intervention is sufficiently supported (Slocum et al. 2012a ; Wilczynski 2012 ). Systematic reviews and claims based upon them must be examined critically with full recognition of their limitations just as one examines primary research reports.

Behavior analysts encounter many situations in which no ESTs have been established for the particular combination of client characteristics, target behaviors, functions, contexts, and other parameters for decision-making. This dearth may exist because no systematic review has addressed the particular problem or because a systematic review has been conducted but failed to find any well-supported treatments for the particular problem. For example, in a recent review of all of the recommendations in the empirically supported practice guides published by the IES, 45 % of the recommendations had minimal support (Slocum et al. 2012b ). As Smith noted ( 2013 ), only 3 of the 11 interventions that the NAC identified as meeting quality standards might be considered practices in the sense that they are manualized. In these common situations, a behavior analyst cannot respond by simply selecting an intervention from a list of ESTs. A comprehensive EBP of ABA requires additional strategies for reviewing research evidence and drawing practice recommendations from existing evidence—strategies that can glean the best available evidence from an imperfect research base and formulate practice recommendations that are most likely to lead to favorable outcomes under conditions of uncertainty.

Other Methods for Reviewing Research Literature

The three strategies outlined below may complement systematic reviews in guiding behavior analysts toward effective decision-making.

Narrative Reviews of the Literature

There has been a long tradition across disciplines of relying on narrative reviews to summarize what is known with respect to treatments for a class of problems (e.g., aggression) or what is known about a particular treatment (e.g., token economy). The author of the review, presumably an expert, selects the theme and synthesizes the research literature that he or she considers most relevant. Narrative reviews allow the author to consider a wide range of research including studies that are indirectly relevant (e.g., those studying a given problem with a different population or demonstrating general principles) and studies that may not qualify for systematic reviews because of methodological limitations but which illustrate important points nonetheless. Narrative reviews can consider a broader array of evidence and have greater interpretive flexibility than most systematic reviews.

As with all sources of evidence, there are difficulties with narrative reviews. The selection of the literature is left up to the author’s discretion; there are no methodological guidelines and little transparency about how the author decided which literature to include and which to exclude. There is always the risk of confirmation bias that the author emphasized literature that is consistent with her preconceived opinions. Even with a peer-review process, it is always possible that the author neglected or misinterpreted research relevant to the discussion. These concerns not withstanding, narrative reviews may provide the best available evidence when no systematic reviews exist or when substantial generalizations from the systematic review to the practice context are needed. Many textbooks (e.g., Cooper et al. 2007 ) and handbooks (e.g., Fisher et al. 2011 ; Madden et al. 2013 ) provide excellent examples of narrative reviews that can provide important guidance for evidence-based practitioners of ABA.

Best Practice Guides

Best practice guides are another source of evidence that can inform decisions in the absence of available and relevant systematic reviews. Best practice guides provide recommendations that reflect the collective wisdom of an expert panel. It is presumed that the recommendations reflect what is known from the research literature, but the validity of recommendations is largely derived from the panel’s expertise rather than from the rigor of their methodology. Recommendations from best practice panels are usually much broader than the recommendations from systematic reviews. The recommendations from these guides can provide important information about how to implement a treatment, how to adapt the treatment for specific circumstances, and what is necessary for broad scale or system-wide implementation.

The limitations to best practice guides are similar to those for narrative reviews; specifically, potential bias and lack of transparency are significant concerns. Panel members are typically not selected using a specific set of operationalized criteria. Bias is possible if the panel is drawn too narrowly. If the panel is drawn too broadly; however, the panel may have difficulty reaching a consensus (Wilczynski 2012 ).

Empirically Supported Practice Guides

Empirically supported practice guides, a more recently developed strategy, integrate the strengths of systematic reviews and best practice panels. In this type of review, an expert panel is charged with developing recommendations on a topic. As part of the process, a systematic review of the literature is conducted. Following the systematic review, the panel generates a set of recommendations and objectively determines the strength of evidence for the recommendation and assigns an evidence rating. When there is little empirical evidence directly related to a specific issue, the panel’s recommendations may have weak research support but nonetheless may be based on the best evidence that is available. The obvious advantage of empirically supported practice guides is that there is greater transparency about the review process and certainty of recommendations. Practice recommendations are usually broader than those derived from systematic reviews and address issues related to implementation and acceptable variations to enhance the treatment’s contextual fit (Shanahan et al. 2010 ; Slocum et al. 2012b ). Although empirically supported practice guides offer the objectivity of a systematic review and the flexibility of best practice guidelines, they also face potential sources of error from both methods. Systematic and explicit criteria are used to review the research and rate the level of evidence for each recommendation; however, it is the panel that formulates recommendations. Thus, results of these reviews are influenced by the selection of panel members. When research evidence is incomplete or equivocal, panelists must exercise judgment in interpreting the evidence and drawing conclusions (Shanahan et al. 2010 ).

Other Units of Analysis

Smith ( 2013 ) weighed in on the critical issue of the unit of analysis when describing and evaluating treatments (Slocum and Wilczynski 2008 ). The unit of analysis refers to whether EBP should focus on (a) principles, such as reinforcement; (b) tactics, such as backward chaining; (c) multicomponent packages, such as Functional Communication Training; or (d) even more comprehensive systems, such as Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention. After reviewing the ongoing debate between those favoring a smaller unit of analysis that focuses on specific procedures and those favoring a larger unit of analysis that evaluates the effects of multicomponent packages, Smith made a case that the multicomponent treatment package is the key unit in EBP. Smith noted that practitioners rarely solve a client’s problem with a single procedure; instead, solutions typically involve combinations of procedures. He argued that the unit should be “a service aimed at solving people’s problems” and procedures that are merely components of such services are not sufficiently complete to be the proper unit of analysis for EBP. He further stated that these treatment packages should include strategies for implementation in typical service settings and an intervention manual.

We concur that the multicomponent treatment package is a particularly significant and strategic unit of treatment because it specifies a suite of procedures and exactly how they are to be used together to solve a problem. Validated treatment packages are far more than the sum of their parts. A well-developed treatment package can be revised and optimized over many iterations in a way that would be difficult or impossible for a practitioner to accomplish independently. In addition, research outcomes from implementation of treatment packages reflect the interaction of the components, and these interactions may not be evident in the research literature on the individual components. Further, research on the outcomes from multicomponent packages can evaluate broader and more socially important outcomes than is generally possible when evaluating more narrowly defined treatments. For example, in the case of teaching a child with autism to communicate, research on a focused procedure such as time delay may indicate that its use leads to more independent communicative responses; however, research on a comprehensive Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention can evaluate the impact of the program on children’s global development or intellectual functioning.

Having recognized our agreement with Smith ( 2013 ) on the special importance of multicomponent treatment packages for EBP, we hasten to add that this type of intervention is not enough to support a broad and robust EBP of ABA. EBP must also provide guidance to the practitioner in the frequently encountered situations in which well-established treatment packages are not available. In these situations, problems may be best addressed by building an intervention from a set of elemental components. These components, referred to as practice elements (Chorpita et al. 2005 , 2007 ) or kernels (Embry 2004 ; Embry and Biglan 2008 ), may be validated either directly or indirectly. The practitioner assembles a particular combination of components to solve a specific problem. Because this newly constructed package has not been evaluated as a whole, there is additional uncertainty about the effectiveness of the package, and the quality of evidence may be considered lower than a well-supported treatment package (Slocum et al. 2012b ; Smith 2013 ; however, see Chorpita ( 2003 ) for a differing view). Nonetheless, treatment components that are supported by strong evidence provide the practitioner with tools to solve practical problems when EST packages are not relevant.

In some cases, behavior analysts are presented with problems that cannot be addressed even by assembling established components. In these cases, the ABA practitioner must apply principles of behavior to construct an intervention and must depend on these principles to guide sensible modifications of interventions in response to client needs and to support sensible implementation of interventions. Principles of behavior are broadly generalized statements describing behavioral relations. Their empirical base is extremely large and diverse including both human and nonhuman participants across numerous contexts, behaviors, and consequences. Although principles of behavior are based on an extremely broad research literature, they are also stated at a broad level. As a result, the behavior analyst must use a great deal of judgment in applying principles to particular problems and a particular attempt to apply a principle to solve a problem may not be successful. Thus, although behavioral principles are supported by evidence, newly constructed interventions based on these principles have not yet been evaluated. These interventions must be considered less certain or validated than treatment packages or elements that have been demonstrated to be effective for specific problems, populations, and context (Slocum et al. 2012b ).

Evidence-based practitioners of ABA recognize that the process of selecting and implementing treatments always includes some level of uncertainty (Detrich et al. 2013 ). One of the fundamental tenets of ABA shared with many other professions is that the best evidence regarding the effectiveness of an intervention does not come from systematic literature reviews, best practice guides, or principles of behavior, but from close continual contact with the relevant outcomes (Bushell and Baer 1994 ). The BACB guidelines ( 2010 ) state that, “behavior analysts recognize limits to the certainty with which judgments or predictions can be made about individuals” (item 3.0 [c]). As a result, “the behavior analyst collects data…needed to assess progress within the program” (item 4.07) and “modifies the program on the basis of data” (item 4.08). Thus, an important feature of the EBP of ABA is that professional decision-making does not end with the selection of an initial intervention. The process continues with ongoing progress monitoring and adjustments to the treatment plan as needed to achieve the targeted outcomes. Progress monitoring and data-based decision-making are the ultimate hedge against the inherent uncertainties of imperfect knowledge derived from research. As the quality of the best available evidence decreases, the importance of frequent direct measurement of client progress increases.

Practice decisions are always accompanied by some degree of uncertainty; however, better decisions are likely when multiple of sources of evidence are integrated. For example, a multicomponent treatment package may be an EST for clients who differ slightly from those the practitioner currently serves. Confidence in the use of this treatment may be increased if there is evidence showing the central components are effective with clients belonging to the population of interest. The principles of behavior might further inform sensible variations appropriate for the specific context of practice. When considered together, numerous sources of evidence increase the confidence the behavior analyst can have in the intervention. And when the plan is implemented, progress monitoring may reveal the need for additional adjustments. Each of these different classes of evidence provides answers to different questions for the practitioner, resulting in a more fine-grained analysis of the clinical problem and solutions to it (Detrich et al. 2013 ).

Client Values and Context

In order to be compatible with the underlying tenets of ABA, parallel with other professions, and to promote effective practice, a definition of EBP of ABA must include client values and context among the primary contributors to professional decision-making. Baer et al. ( 1968 ) suggested that the word applied refers to an immediate and important change in behavior that has practical value and that this value is determined “by the interest which society shows in the problems” (p. 92)—that is, by social values. Wolf ( 1978 ) went on to specify that behavior analytic practice can only be termed successful if it addresses goals that are meaningful to our clients, uses procedures that are judged appropriate by our clients, and produces effects that are valued by our clients. These foundational tenets of ABA correspond with the centrality of client values in classic definitions of EBP (e.g., Institute of Medicine 2001 ). Like medical professionals and those in the many other fields that have adopted similar conceptualizations of EBP, behavior analysts have long recognized that client values are critical contributors to responsible decision-making.

Behavior analysts have defined the client as the individual who is the focus of the behavior change, other individuals who are critical to the behavior change process (Baer et al. 1968 ; Heward et al. 2005 ), as well as outside individuals or groups who may have a stake in the target behavior or improved outcomes (Baer et al. 1987 ; Wolf 1978 ). Wolf ( 1978 ) argued that only our clients can judge the social validity of our work and suggested that behavior analysts address three levels of social validity: (a) the social significance of the goals, (b) the social desirability of the procedures, and (c) the social importance of the outcomes. With respect to selection of interventions, Wolf noted, “not only is it important to determine the acceptability of treatment procedures to participants for ethical reasons, it may also be that the acceptability of the program is related to effectiveness, as well as to the likelihood that the program will be adopted and supported by others” (p. 210). He further maintained that clients are the ultimate arbiters of whether or not the effects of a program are sufficiently helpful to be termed successful.

The concept of social validity directs our attention to some of the important aspects of the context of intervention. Intervention always occurs in some context and features of that context can directly influence the fidelity with which the intervention is implemented and its effectiveness. Albin et al. ( 1996 ) expanded further on the contextual variables that might be critical for designing and implementing effective interventions. They described the concept of contextual fit or the congruence of a behavioral support plan and the context and indicate that this fit will determine its implementation, effectiveness, and maintenance.

Contextual fit includes the issues of social validity, but also explicitly encompasses issues associated with the individuals who implement treatments and manage other aspects of the environments within which treatments are implemented. Behavioral intervention plans prescribe the behavior of implementers. These implementers may include professionals, such as therapists and teachers, as well as nonprofessionals, such as family and community members. It is important to consider characteristics of these implementers when developing plans because the success of a plan may hinge on how it corresponds with the values, skills, goals, and stressors of the implementers. Effective plans must be within the skill repertoire of the implementers, or training to fidelity must occur to introduce the plan components into that repertoire. Values, goals, and stressors refer to motivating operations that determine the reinforcing or punishing value of implementing the plan. Plans that provide little reinforcement and substantial punishment in the process of implementation or outcomes are unlikely to be implemented with fidelity or maintained over time. The effectiveness of behavioral interventions is also influenced by their compatibility with other aspects of their context. Plans that are compatible with ongoing routines are more likely to be implemented than those that conflict (Riley-Tillman and Chafouleas 2003 ). Interventions require various kinds of resources to be implemented and sustained. For example, financial resources may be necessary to purchase curricula, equipment, or other goods. Interventions may require human resources such as direct service staff, training, supervision, administration, and consultation. Fixsen et al. ( 2005 ) have completed an extensive review of contextual variables that can potentially influence the quality of intervention implementation. Behavior analytic practice is unlikely to be effective if it does not consider the context in which interventions will be implemented.

Extensive behavior analytic research has documented the importance of social validity and other contextual factors in producing behavioral changes with practical value. This research tradition is as old as our field (e.g., Jones and Azrin 1969 ) and continues through the present day. For example, Strain et al. ( 2012 ) provided multiple examples of the impact of social validity considerations on relevant outcomes. They reported that integrating client values, preferences, and characteristics in the selection and implementation of an intervention can successfully inform decisions regarding (a) how to design service delivery systems, (b) how to support implementers with complex strategies, (c) when to fade support, (e) how to identify important and unanticipated effects, and (f) how to focus on future research efforts.

Benazzi et al. ( 2006 ) examined the effect of stakeholder participation in intervention planning on the acceptability and usability of behavior intervention plans (BIP) based on descriptive functional behavior assessments (FBA). Plans developed by behavior experts were rated as high in technical adequacy, but low in acceptability. Conversely, plans developed by key stakeholders were highly acceptable, but lacked technical adequacy. However, when the process included both behavior experts and key stakeholders, BIPs were considered both acceptable and technically adequate. Thus, the BIPs developed by behavior analysts may be marginalized and implementation may be less likely to occur in the absence of key stakeholder input. Thus, a practical commitment to effective interventions that are implemented and maintained with integrity over time requires that behavior analysts consider motivational variables such as the alignment of interventions with the values, reinforcers, and punishers of relevant stakeholders.

Clinical Expertise

All of the key components for expert behavior analytic practice (i.e., identification of important behavioral problems, recognition of underlying behavioral processes, weighing of evidence supporting various treatment options, selecting and implementing treatments in complex social contexts, engaging in ongoing data-based decision making, and being responsive to client values and context) require clinical expertise. Clinical expertise refers to the competence attained by practitioners through education, training, and experience that results in effective practice (American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force of Evidence-Based Practice 2006 ). Clinical expertise is the means by which the best available evidence is applied to individual cases in all their complexity. Based on the work of Goodheart ( 2006 ), we suggest that clinical expertise in EBP of ABA includes (a) knowledge of the research literature and its applicability to particular clients, (b) incorporation of the conceptual system of ABA, (c) breadth and depth of clinical and interpersonal skills, (d) integration of client values and context, (e) recognition of the need for outside consultation, (f) data-based decision making, and (g) ongoing professional development. In the sections that follow, we describe each component of clinical expertise in ABA.

Knowledge and Application of the Research Literature

ABA practitioners must be skilled in applying the best available evidence to unique cases in specific contexts. The role of the best available evidence in EBP of ABA was discussed above. Practitioners need to be knowledgeable about the scientific literature and able to appropriately apply the literature to behaviors, clients, and contexts that are rarely a perfect match to the behaviors, clients, and contexts in any particular study. This confluence of knowledge and skillful application requires that the behavior analyst respond to the functionally important features of cases. A great deal of training is necessary to build the expertise required to discriminate critical functional features from those that are incidental. These discriminations must be made with respect to the presenting problem (i.e., the behavioral patterns that have been identified as problematic, their antecedent stimuli, motivating operations, and consequences); client variables such as histories, skills, and preferences; and contextual variables that may impact the effectiveness of various treatment options as applied to the particular case. These skills are reflected in BACB Guidelines 1.01 and 2.10 cited above.

Incorporation of the Conceptual System

The critical features of a case must be identified and mapped onto the conceptual system of ABA. It is not enough to recognize that a particular feature of the environment is important; it must also be understood in terms of its likely behavioral function. This initial conceptualization is necessary in order to generate reasonable hypotheses that may be tested in more thorough analyses. Developing the skill of describing cases in terms of likely behavioral functions typically requires a great deal of formal and informal training as well as ongoing learning from experience. These repertoires are usually acquired through extensive training, supervised practice, and the ongoing feedback of client outcomes. This is recognized in BACB Guidelines; for example, 4.0 states that “the behavior analyst designs programs that are based on behavior analytic principles” (BACB 2010 ).

Breadth and Depth of Clinical and Interpersonal Skills

Evidence-based practitioners of behavior analysis must be able to implement various assessment and intervention procedures with fidelity, and often to train and supervise others to implement such procedures with fidelity. Further, clinical expertise in ABA requires that the practitioner have effective interpersonal skills. For example, he must be able to explain the behavioral philosophy and approach, in nonbehavioral terms, to various audiences who may have different theoretical orientations. BCBA Guidelines 1.05 specifies that behavior analysts “use language that is fully understandable to the recipient of those services” (BACB 2010 ).

Integration of Client Values and Context

In all aspects of their work, practitioners of evidence-based ABA must integrate the values and preferences of the client and other stakeholders as well as the features of the specific context that may impact the effectiveness of an intervention. These factors can be considered additional variables that the behavior analyst must attend to when planning and providing behavior-analytic services. For example, when assessment data suggest behavior serves a particular function, a range of intervention alternatives may be considered (see Geiger, Carr, and LeBlanc for an example of a model for selecting treatments for escape-maintained problem behavior). A caregiver’s statements might suggest that one type of intervention may not be viable due to limited resources while another treatment may be acceptable based on financial considerations, available resources, or other practical factors; the behavior analyst must have the training and expertise to evaluate and incorporate these factors into initial treatment selection and to re-evaluate these concerns as a part of progress monitoring for both treatment integrity and client improvement. BACB Guideline 4.0 states that the behavior analyst “involves the client … in the planning of … programs, [and] obtains the consent of the client” and 4.1 states that “if environmental conditions hamper implementation of the behavior analytic program, the behavior analyst seeks to eliminate the environmental constraints, or identifies in writing the obstacles to doing so” (BACB 2010 ).

Recognition of Need for Outside Consultation

Behavior analysts engaging in responsible evidence-based practice discriminate between behaviors and contexts that are within the scope of their training and those that are not, and respond differently based on this discrimination. For example, a behavior analyst who has been trained to provide assessment and intervention for severe problem behavior may not have the specific training to provide organizational behavior management services to a corporation; in this case, a behavior analyst with clinical expertise would make this discrimination and seek additional consultation or make appropriate referrals. This aspect of expertise is described in BACB ( 2010 ) Guidelines 1.02 and 2.02.

Data-Based Decision Making

Data-based decision making plays a central role in the practice of ABA and is an indispensable feature of clinical expertise. The process of data-based decision making includes identifying useful measurement pinpoints, constructing measurement systems, and graphing results, as well as identifying meaningful patterns in data, interpreting these patterns, and making appropriate responses to them (e.g., maintaining, modifying, replacing, or ending a program). The functional features of the case, the best available research evidence, and the new evidence obtained through progress monitoring must inform these judgments and are central to this model of EBP of ABA. BACB ( 2010 ) Guidelines 4.07 and 4.08 specify that behavior analysts collect data to assess progress and modify programs on the basis of data.

Ongoing Professional Development

Clinical expertise is not static; rather, it requires ongoing professional development. Clinical expertise in ABA requires ongoing contact with the research literature to ensure that practice reflects current knowledge about the most effective and efficient assessment and intervention procedures. The critical literature includes primary empirical research as well as reviews and syntheses such as those described in the section on “ Best Available Evidence ”. In addition, professional consensus on important topics for professional practice evolves over time. For example, in ABA, there has been increased emphasis recently on ethics and supervision competence. All of these dynamics point to the need for ongoing professional development. This is reflected in the requirement that certified behavior analysts “undertake ongoing efforts to maintain competence in the skills they use by reading the appropriate literature, attending conferences and conventions, participating in workshops, and/or obtaining Behavior Analyst Certification Board certification” (Guideline 1.03, BACB 2010 ).

Conclusions

We propose that EBP of ABA be understood as a professional decision-making framework that draws on the best available evidence, client values and context, and clinical expertise. We argue that this conception of EBP of ABA is more compatible with the basic tenets of ABA and more closely aligned with definitions of EBP in other fields than that provided by Smith ( 2013 ). It is noteworthy that this notion of EBP is not necessarily in conflict with many of the observations and arguments put forth by Smith ( 2013 ). His concerns were primarily about how to define and validate EST, which is an important way to inform practitioners about the best available evidence to integrate into their overall EBP.

Given the close alignment between the proposed framework of EBP of ABA and broadly accepted descriptions of behavior analytic practice, one might wonder whether EBP offers anything new. We believe that the EBP of ABA framework, offered here, has several important implications for our field. First, this framework draws together numerous elements of ABA practice into a single coherent system, which can help behavior analysts provide an explicit rationale for their decision-making to clients and other stakeholders. The EBP of ABA provides a decision-making framework that supports a cogent and transparent description of (a) the evidence considered, including direct and frequent measurement of the client’s behavior; (b) why this evidence was identified as the “best available” for the particular case; (c) how client values and contextual factors influenced the process; and (d) the ways in which clinical expertise was used to conceptualize the case and integrate the various considerations. This transparency and explicitness allows the behavior analyst to offer empirically based treatment recommendations while addressing the concerns raised by stakeholders. It also highlights the critical analysis required to be an effective behavior analyst. For example, if an EST is available and appropriate, the behavior analyst can describe the relevance and certainty of the evidence for this intervention. If no relevant EST is available, the behavior analyst can describe how the best available evidence supports the intervention and emphasize the importance of progress monitoring.

Second, the EBP framework prompts the behavior analyst to refer to the important client values that underlie the goals of intervention, the specific methods of intervention, and describe how the intervention is supported by features of the context. This requires the behavior analyst to explicitly recognize that the effectiveness of an intervention is always context dependent. By serving as a prompt, the EBP framework should increase behavior analysts’ adherence to this central tenet of ABA.

Third, by explicitly recognizing the role of clinical expertise, the framework gives the behavior analyst a way to talk about the complex skills required to make appropriate decisions about client needs. In addition, the fact that the proposed definition of EBP of ABA is so closely aligned with definitions in other professions such as medicine and psychology that it provides a common framework and language for communicating about a particular case that can enhance collaboration between behavior analysts and other professionals.

Fourth, this framework for EBP of ABA suggests further development of behavior analysis as well. Examination of the meaning of best available evidence encourages behavior analysts to continue to refine methods for systematically reviewing research literature and identifying ESTs. Further, behavior analysts could better support EBP if we developed methods for validating other units of intervention such as practice elements, kernels, and even the principles of behavior; when these are invoked to support interventions, they must be supported by a clearly specified research base.

Finally, the explicit recognition of the role of clinical expertise in the EBP of ABA has important implications for training behavior analysts. This framework suggests that decision-making is at the heart of EBP of ABA and could be an organizing theme for ABA training programs. Training programs could systematically teach students to articulate the chain of logic that is the basis for their treatment recommendations. The chain of logic would include statements about which research was considered and why, how the client’s values influenced decision-making, and how contextual factors influenced the selection and adaptation (if necessary) of the treatment. This type of training could be embedded in all instructional activities. Formally requiring students to articulate a rationale for the decisions and receiving feedback about their decisions would sharpen their clinical expertise.

In addition to influencing our behavior analytic practice, the EBP of ABA framework impacts our relationship with other members of the broader human service field as well as individuals and agencies that control contingencies relevant to practitioners and scientists. Methodologically rigorous reviews that identify ESTs and other treatments supported by the best available evidence are extremely important for working with organizations that control funding for behavior analytic research and practice. Federal funding for research and service provision is moving strongly towards EBP and ESTs. This trend is clear in education through the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 , the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004 , the funding policies of IES, and the What Works Clearinghouse. The recent memorandum by the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (Zients 2012 ) makes it clear that the importance of EBP is not limited to a single discipline or to one political party. In addition, insurance companies are increasingly making reimbursement decisions based, in part, on whether or not credible scientific evidence supports the use of the treatment (Small 2004 ). The insurance companies have consistently adopted criteria for scientific evidence that are closely related to EST (Bogduk and Fraifeld 2010 ). As a result, reimbursement for ABA services may depend on the scientific credibility of EST reviews, a critical component of EBP. Methodologically rigorous reviews that identify ESTs within a broader framework of EBP appear to be critical for ABA to maintain and expand its access to federal funding and insurance reimbursement for services. Establishment of this literature base will require behavior analysts to develop appropriate methods for reviewing and summarizing research based on single-subject designs. IES has established such standards for reviewing studies, but to date, there are no accepted methods for calculating a measure of effect size as an objective basis for combining result across studies (Kratochwill et al. 2013 ). If behavior analysts develop such a measure, it would reflect a significant methodological advance as a field and it would increase the credibility of behavior analytic research with agencies that fund research and services.

EBP of ABA emphasizes the research-supported selection of treatments and data-driven decisions about treatment progress that have always been at the core of ABA. ABA’s long-standing recognition of the importance of social validity is reflected in the definition of EBP. This framework for EBP of ABA offers many positive professional consequences for scientists and practitioners while promoting the best of the behavior analytic tradition and making contact with developments in other disciplines and the larger context in which behavior analysts work.

- Albin RW, Lucyshyn JM, Horner RH, Flannery KB. Contextual fit for behavior support plans. In: Koegel LK, Koegel RL, Dunlap G, editors. Positive behavioral support: Including people with difficult behaviors in the community. Baltimore: Brookes; 1996. pp. 81–92. [ Google Scholar ]

- American Occupational Therapy Association Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process (2nd ed.) American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008; 62 :625–683. doi: 10.5014/ajot.62.6.625. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American Psychological Association (2005). Policy statement on evidence-based practice in psychology. http://www.apa.org/practice/resources/evidence/evidence-based-statement.pdf .

- American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force of Evidence-Based Practice Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist. 2006; 61 :271–285. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (2005). Evidence-based practice in communication disorders [position statement]. www.asha.org/policy .

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968; 1 :91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some still-current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1987; 20 :313–327. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1987.20-313. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board (2010). Guidelines for responsible conduct for behavior analysts. http://www.bacb.com/index.php?page=57 .

- Benazzi L, Horner RH, Good RH. Effects of behavior support team composition on the technical adequacy and contextual-fit of behavior support plans. The Journal of Special Education. 2006; 40 (3):160–170. doi: 10.1177/00224669060400030401. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bogduk N, Fraifeld EM. Proof or consequences: who shall pay for the evidence in pain medicine? Pain Medicine. 2010; 11 (1):1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00770.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bushell D, Jr, Baer DM. Measurably superior instruction means close, continual contact with the relevant outcome data. Revolutionary! In: Gardner R III, Sainato DM, Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL, Eshleman J, Grossi TA, editors. Behavior analysis in education: Focus on measurably superior instruction. Pacific Grove: Brooks; 1994. pp. 3–10. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carnine D. Expanding the notion of teachers’ rights: access to tools that work. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992; 25 (1):13–19. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-13. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carr JE, Severtson JM, Lepper TL. Noncontingent reinforcement is an empirically supported treatment for problem behavior exhibited by individuals with developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009; 30 :44–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.03.002. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chorpita BF. The frontier of evidence-based practice. In: Kazdin AE, Weisz JR, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York: Oxford; 2003. pp. 42–59. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Weisz JR. Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: a distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research. 2005; 7 :5–20. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-1962-6. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chorpita BF, Becker KD, Daleiden EL. Understanding the common elements of evidence-based practice: misconceptions and clinical examples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007; 46 :647–652. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318033ff71. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cook BG, Cook SC. Unraveling evidence-based practices in special education. Journal of Special Education. 2013; 47 (2):71–82. doi: 10.1177/0022466911420877. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied behavior analysis. 2. Upper Saddle River: Pearson; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Detrich, R. (Chair) (2009). Evidence-based, empirically supported, best practice: What does it all mean? Symposium conducted at the annual meeting of the Association for Behavior Analysis International, Phoenix, AZ.

- Detrich R, Slocum TA, Spencer TD. Evidence-based education and best available evidence: Decision-making under conditions of uncertainty. In: Cook BG, Tankersley M, Landrum TJ, editors. Advances in learning and behavioral disabilities, 26. Bingly, UK: Emerald; 2013. pp. 21–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Embry DD. Community-based prevention using simple, low-cost, evidence-based kernels and behavior vaccines. Journal of Community Psychology. 2004; 32 :575–591. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20020. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Embry DD, Biglan A. Evidence-based kernels: fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2008; 11 :75–113. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0036-x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fisher WW, Piazza CC, Roane HS, editors. Handbook of applied behavior analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature (FMHI publication #231) Tampa: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodheart CD. Evidence, endeavor, and expertise in psychology practice. In: Goodheart CD, Kazdin AE, Sternberg RJ, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapy: Where practice and research meet. Washington, D.C.: APA; 2006. pp. 37–61. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodman KW. Ethics and evidence-based education: Fallibility and responsibility in clinical science. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Heward WL, et al., editors. Focus on behavior analysis in education: Achievements, challenges, and opportunities. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Horner RH, Carr EG, Halle J, McGee G, Odom S, Wolery M. The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children. 2005; 71 (2):165–179. doi: 10.1177/001440290507100203. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Horner RH, Sugai G, Todd AW, Lewis-Palmer T. Schoolwide positive behavior support. In: Bambera LM, Kern L, editors. Individualized supports for students with problem behaviors: Designing positive behavior plans. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 359–390. [ Google Scholar ]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, 70, Fed. Reg., (2005).

- Institute of Education Sciences, US. Department of Education. (n.d.). What Works Clearinghouse Procedures and Standards Handbook (No. Version 3.0). Washington DC. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/reference_resources/wwc_procedures_v3_0_standards_handbook.pdf .

- Institute of Medicine . Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnston JM, Pennypacker HS. Strategies and tactics of behavioral research. 2. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1993. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jones RJ, Azrin NH. Behavioral engineering: stuttering as a function of stimulus duration during speech synchronization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1969; 2 :223–229. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1969.2-223. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kazdin AE. Psychotherapy for children and adolescents: Directions for research and practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kratochwill, T. R., Hitchcock, J., Horner, R. H., Levin, J. R., Odom, S. L., Rindskopf, D. M., & Shadish, W. R. (2010). Single-case designs technical documentation. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf .

- Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock JH, Horner RH, Levin JR, Odom SL, Rindskopf DM, et al. Single-case intervention research design standards. Remedial & Special Education. 2013; 34 (1):26–38. doi: 10.1177/0741932512452794. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Madden GJ, Dube WV, Hackenberg TD, Hanley GP, Lattal KA, editors. American Psychological Association handbook of behavior analysis. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maggin DM, O’Keeffe BV, Johnson AH. A quantitative synthesis of single-subject meta-analyses in special education, 1985–2009. Exceptionality. 2011; 19 :109–135. doi: 10.1080/09362835.2011.565725. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maggin DM, Johnson AH, Chafouleas SM, Ruberto LM, Berggren M. A systematic evidence review of school-based group contingency interventions for students with challenging behavior. Journal of School Psychology. 2012; 50 :625–654. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2012.06.001. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McIntosh K, Filter KJ, Bennett JL, Ryan C, Sugai G. Principles of sustainable prevention: designing scale–up of School–wide Positive Behavior Support to promote durable systems. Psychology in the Schools. 2010; 47 (1):5–21. [ Google Scholar ]

- National Autism Center . National Standards Project: Findings and conclusions. Randolph: National Autism Center; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 107-110. (2002).

- Polsgrove L. Reflections on the past and future. Education and Treatment of Children. 2003; 26 :337–344. [ Google Scholar ]

- Riley-Tillman TC, Chafouleas SM. Using interventions that exist in the natural environment to increase treatment integrity and social influence in consultation. Journal of Educational & Psychological Consultation. 2003; 14 (2):139–156. doi: 10.1207/s1532768xjepc1402_3. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal. 1996; 312 (7023):71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB, editors. Evidence-based medicine: How to teach and practice EBM. Edinburgh: Livingstone; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]