Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

Should College Athletes Be Paid? An Expert Debate Analysis

Extracurriculars

The argumentative essay is one of the most frequently assigned types of essays in both high school and college writing-based courses. Instructors often ask students to write argumentative essays over topics that have “real-world relevance.” The question, “Should college athletes be paid?” is one of these real-world relevant topics that can make a great essay subject!

In this article, we’ll give you all the tools you need to write a solid essay arguing why college athletes should be paid and why college athletes should not be paid. We'll provide:

- An explanation of the NCAA and what role it plays in the lives of student athletes

- A summary of the pro side of the argument that's in favor of college athletes being paid

- A summary of the con side of the argument that believes college athletes shouldn't be paid

- Five tips that will help you write an argumentative essay that answers the question "Should college athletes be paid?"

The NCAA is the organization that oversees and regulates collegiate athletics.

What Is the NCAA?

In order to understand the context surrounding the question, “Should student athletes be paid?”, you have to understand what the NCAA is and how it relates to student-athletes.

NCAA stands for the National Collegiate Athletic Association (but people usually just call it the “N-C-double-A”). The NCAA is a nonprofit organization that serves as the national governing body for collegiate athletics.

The NCAA specifically regulates collegiate student athletes at the organization’s 1,098 “member schools.” Student-athletes at these member schools are required to follow the rules set by the NCAA for their academic performance and progress while in college and playing sports. Additionally, the NCAA sets the rules for each of their recognized sports to ensure everyone is playing by the same rules. ( They also change these rules occasionally, which can be pretty controversial! )

The NCAA website states that the organization is “dedicated to the well-being and lifelong success of college athletes” and prioritizes their well-being in academics, on the field, and in life beyond college sports. That means the NCAA sets some pretty strict guidelines about what their athletes can and can't do. And of course, right now, college athletes can't be paid for playing their sport.

As it stands, NCAA athletes are allowed to receive scholarships that cover their college tuition and related school expenses. But historically, they haven't been allowed to receive additional compensation. That meant athletes couldn't receive direct payment for their participation in sports in any form, including endorsement deals, product sponsorships, or gifts.

Athletes who violated the NCAA’s rules about compensation could be suspended from participating in college sports or kicked out of their athletic program altogether.

The Problem: Should College Athletes Be Paid?

You know now that one of the most well-known functions of the NCAA is regulating and limiting the compensation that student-athletes are able to receive. While many people might not question this policy, the question of why college athletes should be paid or shouldn't be paid has actually been a hot-button topic for several years.

The fact that people keep asking the question, “Should student athletes be paid?” indicates that there’s some heat out there surrounding this topic. The issue is frequently debated on sports talk shows , in the news media , and on social media . Most recently, the topic re-emerged in public discourse in the U.S. because of legislation that was passed by the state of California in 2019.

In September 2019, California governor Gavin Newsom signed a law that allowed college athletes in California to strike endorsement deals. An endorsement deal allows athletes to be paid for endorsing a product, like wearing a specific brand of shoes or appearing in an advertisement for a product.

In other words, endorsement deals allow athletes to receive compensation from companies and organizations because of their athletic talent. That means Governor Newsom’s bill explicitly contradicts the NCAA’s rules and regulations for financial compensation for student-athletes at member schools.

But why would Governor Newsom go against the NCAA? Here’s why: the California governor believes that it's unethical for the NCAA to make money based on the unpaid labor of its athletes . And the NCAA definitely makes money: each year, the NCAA upwards of a billion dollars in revenue as a result of its student-athlete talent, but the organization bans those same athletes from earning any money for their talent themselves. With the new California law, athletes would be able to book sponsorships and use agents to earn money, if they choose to do so.

The NCAA’s initial response to California’s new law was to push back hard. But after more states introduced similar legislation , the NCAA changed its tune. In October 2019, the NCAA pledged to pass new regulations when the board voted unanimously to allow student athletes to receive compensation for use of their name, image, and likeness.

Simply put: student athletes can now get paid through endorsement deals.

In the midst of new state legislation and the NCAA’s response, the ongoing debate about paying college athletes has returned to the spotlight. Everyone from politicians, to sports analysts, to college students are arguing about it. There are strong opinions on both sides of the issue, so we’ll look at how some of those opinions can serve as key points in an argumentative essay.

Let's take a look at the arguments in favor of paying student athletes!

The Pros: Why College Athletes Should B e Paid

Since the argument about whether college athletes should be paid has gotten a lot of public attention, there are some lines of reasoning that are frequently called upon to support the claim that college athletes should be paid.

In this section, we'll look at the three biggest arguments in favor of why college athletes should be paid. We'll also give you some ideas on how you can support these arguments in an argumentative essay.

Argument 1: The Talent Should Receive Some of the Profits

This argument on why college athletes should be paid is probably the one people cite the most. It’s also the easiest one to support with facts and evidence.

Essentially, this argument states that the NCAA makes millions of dollars because people pay to watch college athletes compete, and it isn’t fair that the athletes don't get a share of the profits

Without the student athletes, the NCAA wouldn’t earn over a billion dollars in annual revenue , and college and university athletic programs wouldn’t receive hundreds of thousands of dollars from the NCAA each year. In fact, without student athletes, the NCAA wouldn’t exist at all.

Because student athletes are the ones who generate all this revenue, people in favor of paying college athletes argue they deserve to receive some of it back. Otherwise, t he NCAA and other organizations (like media companies, colleges, and universities) are exploiting a bunch of talented young people for their own financial gain.

To support this argument in favor of paying college athletes, you should include specific data and revenue numbers that show how much money the NCAA makes (and what portion of that actually goes to student athletes). For example, they might point out the fact that the schools that make the most money in college sports only spend around 10% of their tens of millions in athletics revenue on scholarships for student-athletes. Analyzing the spending practices of the NCAA and its member institutions could serve as strong evidence to support this argument in a “why college athletes should be paid” essay.

I've you've ever been a college athlete, then you know how hard you have to train in order to compete. It can feel like a part-time job...which is why some people believe athletes should be paid for their work!

Argument 2: College Athletes Don’t Have Time to Work Other Jobs

People sometimes casually refer to being a student-athlete as a “full-time job.” For many student athletes, this is literally true. The demands on a student-athlete’s time are intense. Their days are often scheduled down to the minute, from early in the morning until late at night.

One thing there typically isn’t time for in a student-athlete’s schedule? Working an actual job.

Sports programs can imply that student-athletes should treat their sport like a full-time job as well. This can be problematic for many student-athletes, who may not have any financial resources to cover their education. (Not all NCAA athletes receive full, or even partial, scholarships!) While it may not be expressly forbidden for student-athletes to get a part-time job, the pressure to go all-in for your team while still maintaining your eligibility can be tremendous.

In addition to being a financial burden, the inability to work a real job as a student-athlete can have consequences for their professional future. Other college students get internships or other career-specific experience during college—opportunities that student-athletes rarely have time for. When they graduate, proponents of this stance argue, student-athletes are under-experienced and may face challenges with starting a career outside of the sports world.

Because of these factors, some argue that if people are going to refer to being a student-athlete as a “full-time job,” then student-athletes should be paid for doing that job.

To support an argument of this nature, you can offer real-life examples of a student-athlete’s daily or weekly schedule to show that student-athletes have to treat their sport as a full-time job. For instance, this Twitter thread includes a range of responses from real student-athletes to an NCAA video portraying a rose-colored interpretation of a day in the life of a student-athlete.

Presenting the Twitter thread as one form of evidence in an essay would provide effective support for the claim that college athletes should be paid as if their sport is a “full-time job.” You might also take this stance in order to claim that if student-athletes aren’t getting paid, we must adjust our demands on their time and behavior.

Argument 3: Only Some Student Athletes Should Be Paid

This take on the question, “Should student athletes be paid?” sits in the middle ground between the more extreme stances on the issue. There are those who argue that only the student athletes who are big money-makers for their university and the NCAA should be paid.

The reasoning behind this argument? That’s just how capitalism works. There are always going to be student-athletes who are more talented and who have more media-magnetizing personalities. They’re the ones who are going to be the face of athletic programs, who lead their teams to playoffs and conference victories, and who are approached for endorsement opportunities.

Additionally, some sports don't make money for their schools. Many of these sports fall under Title IX, which states that no one can be excluded from participation in a federally-funded program (including sports) because of their gender or sex. Unfortunately, many of these programs aren't popular with the public , which means they don't make the same revenue as high-dollar sports like football or basketball .

In this line of thinking, since there isn’t realistically enough revenue to pay every single college athlete in every single sport, the ones who generate the most revenue are the only ones who should get a piece of the pie.

To prove this point, you can look at revenue numbers as well. For instance, the womens' basketball team at the University of Louisville lost $3.8 million dollars in revenue during the 2017-2018 season. In fact, the team generated less money than they pay for their coaching staff. In instances like these, you might argue that it makes less sense to pay athletes than it might in other situations (like for University of Alabama football, which rakes in over $110 million dollars a year .)

There are many people who think it's a bad idea to pay college athletes, too. Let's take a look at the opposing arguments.

The Cons: Why College Athletes Shouldn't Be Paid

People also have some pretty strong opinions about why college athletes shouldn't be paid. These arguments can make for a pretty compelling essay, too!

In this section, we'll look at the three biggest arguments against paying college athletes. We'll also talk about how you can support each of these claims in an essay.

Argument 1: College Athletes Already Get Paid

On this side of the fence, the most common reason given for why college athletes should not be paid is that they already get paid: they receive free tuition and, in some cases, additional funding to cover their room, board, and miscellaneous educational expenses.

Proponents of this argument state that free tuition and covered educational expenses is compensation enough for student-athletes. While this money may not go straight into a college athlete's pocket, it's still a valuable resource . Considering most students graduate with nearly $30,000 in student loan debt , an athletic scholarship can have a huge impact when it comes to making college affordable .

Evidence for this argument might look at the financial support that student-athletes receive for their education, and compare those numbers to the financial support that non-athlete students receive for their schooling. You can also cite data that shows the real value of a college tuition at certain schools. For example, student athletes on scholarship at Duke may be "earning" over $200,000 over the course of their collegiate careers.

This argument works to highlight the ways in which student-athletes are compensated in financial and in non-financial ways during college , essentially arguing that the special treatment they often receive during college combined with their tuition-free ride is all the compensation they have earned.

Some people who are against paying athletes believe that compensating athletes will lead to amateur athletes being treated like professionals. Many believe this is unfair and will lead to more exploitation, not less.

Argument 2: Paying College Athletes Would Side-Step the Real Problem

Another argument against paying student athletes is that college sports are not professional sports , and treating student athletes like professionals exploits them and takes away the spirit of amateurism from college sports .

This stance may sound idealistic, but those who take this line of reasoning typically do so with the goal of protecting both student-athletes and the tradition of “amateurism” in college sports. This argument is built on the idea that the current system of college sports is problematic and needs to change, but that paying student-athletes is not the right solution.

Instead, this argument would claim that there is an even better way to fix the corrupt system of NCAA sports than just giving student-athletes a paycheck. To support such an argument, you might turn to the same evidence that’s cited in this NPR interview : the European model of supporting a true minor league system for most sports is effective, so the U.S. should implement a similar model.

In short: creating a minor league can ensure athletes who want a career in their sport get paid, while not putting the burden of paying all collegiate athletes on a university.

Creating and supporting a true professional minor league would allow the students who want to make money playing sports to do so. Universities could then confidently put earned revenue from sports back into the university, and student-athletes wouldn’t view their college sports as the best and only path to a career as a professional athlete. Those interested in playing professionally would be able to pursue this dream through the minor leagues instead, and student athletes could just be student athletes.

The goal of this argument is to sort of achieve a “best of both worlds” solution: with the development and support of a true minor league system, student-athletes would be able to focus on the foremost goal of getting an education, and those who want to get paid for their sport can do so through the minor league. Through this model, student-athletes’ pursuit of their education is protected, and college sports aren’t bogged down in ethical issues and logistical hang-ups.

Argument 3: It Would Be a Logistical Nightmare

This argument against paying student athletes takes a stance on the basis of logistics. Essentially, this argument states that while the current system is flawed, paying student athletes is just going to make the system worse. So until someone can prove that paying collegiate athletes will fix the system, it's better to maintain the status quo.

Formulating an argument around this perspective basically involves presenting the different proposals for how to go about paying college athletes, then poking holes in each proposed approach. Such an argument would probably culminate in stating that the challenges to implementing pay for college athletes are reason enough to abandon the idea altogether.

Here's what we mean. One popular proposed approach to paying college athletes is the notion of “pay-for-play.” In this scenario, all college athletes would receive the same weekly stipend to play their sport .

In this type of argument, you might explain the pay-for-play solution, then pose some questions toward the approach that expose its weaknesses, such as: Where would the money to pay athletes come from? How could you pay athletes who play certain sports, but not others? How would you avoid Title IX violations? Because there are no easy answers to these questions, you could argue that paying college athletes would just create more problems for the world of college sports to deal with.

Posing these difficult questions may persuade a reader that attempting to pay college athletes would cause too many issues and lead them to agree with the stance that college athletes should not be paid.

5 Tips for Writing About Paying College Athletes

If you’re assigned the prompt “Should college athletes be paid," don't panic. There are several steps you can take to write an amazing argumentative essay about the topic! We've broken our advice into five helpful tips that you can use to persuade your readers (and ace your assignment).

Tip 1: Plan Out a Logical Structure for Your Essay

In order to write a logical, well-organized argumentative essay, one of the first things you need to do is plan out a structure for your argument. Using a bare-bones argumentative outline for a “why college athletes should be paid” essay is a good place to start.

Check out our example of an argumentative essay outline for this topic below:

- The thesis statement must communicate the topic of the essay: Whether college athletes should be paid, and

- Convey a position on that topic: That college athletes should/ should not be paid, and

- State a couple of defendable, supportable reasons why college athletes should be paid (or vice versa).

- Support Point #1 with evidence

- Explain/interpret the evidence with your own, original commentary

- Support Point #2 with evidence

- Explain/interpret the evidence with your own, original commentary

- Support Point #3 with evidence

- New body paragraph addressing opposing viewpoints

- Concluding paragraph

This outline does a few things right. First, it makes sure you have a strong thesis statement. Second, it helps you break your argument down into main points (that support your thesis, of course). Lastly, it reminds you that you need to both include evidence and explain your evidence for each of your argumentative points.

While you can go off-book once you start drafting if you feel like you need to, having an outline to start with can help you visualize how many argumentative points you have, how much evidence you need, and where you should insert your own commentary throughout your essay.

Remember: the best argumentative essays are organized ones!

Tip 2: Create a Strong Thesis

T he most important part of the introduction to an argumentative essay claiming that college athletes should/should not be paid is the thesis statement. You can think of a thesis like a backbone: your thesis ties all of your essay parts together so your paper can stand on its own two feet!

So what does a good thesis look like? A solid thesis statement in this type of argumentative essay will convey your stance on the topic (“Should college athletes be paid?”) and present one or more supportable reasons why you’re making this argument.

With these goals in mind, here’s an example of a thesis statement that includes clear reasons that support the stance that college athletes should be paid:

Because the names, image, and talents of college athletes are used for massive financial gain, college athletes should be able to benefit from their athletic career in the same way that their universities do by getting endorsements.

Here's a thesis statement that takes the opposite stance--that college athletes shouldn’t be paid --and includes a reason supporting that stance:

In order to keep college athletics from becoming over-professionalized, compensation for college athletes should be restricted to covering college tuition and related educational expenses.

Both of these sample thesis statements make it clear that your essay is going to be dedicated to making an argument: either that college athletes should be paid, or that college athletes shouldn’t be paid. They both convey some reasons why you’re making this argument that can also be supported with evidence.

Your thesis statement gives your argumentative essay direction . Instead of ranting about why college athletes should/shouldn’t be paid in the remainder of your essay, you’ll find sources that help you explain the specific claim you made in your thesis statement. And a well-organized, adequately supported argument is the kind that readers will find persuasive!

Tip 3: Find Credible Sources That Support Your Thesis

In an argumentative essay, your commentary on the issue you’re arguing about is obviously going to be the most fun part to write. But great essays will cite outside sources and other facts to help substantiate their argumentative points. That's going to involve—you guessed it!—research.

For this particular topic, the issue of whether student athletes should be paid has been widely discussed in the news media (think The New York Times , NPR , or ESPN ).

For example, this data reported by the NCAA shows a breakdown of the gender and racial demographics of member-school administration, coaching staff, and student athletes. These are hard numbers that you could interpret and pair with the well-reasoned arguments of news media writers to support a particular point you’re making in your argument.

Though this may seem like a topic that wouldn’t generate much scholarly research, it’s worth a shot to check your library database for peer-reviewed studies of student athletes’ experiences in college to see if anything related to paying student athletes pops up. Scholarly research is the holy grail of evidence, so try to find relevant articles if you can.

Ultimately, if you can incorporate a mix of mainstream sources, quantitative or statistical evidence, and scholarly, peer-reviewed sources, you’ll be on-track to building an excellent argument in response to the question, “Should student athletes be paid?”

Having multiple argumentative points in your essay helps you support your thesis.

Tip 4: Develop and Support Multiple Points

We’ve reviewed how to write an intro and thesis statement addressing the issue of paying college athletes, so let’s talk next about the meat and potatoes of your argumentative essay: the body paragraphs.

The body paragraphs that are sandwiched between your intro paragraph and concluding paragraph are where you build and explain your argument. Generally speaking, each body paragraph should do the following:

- Start with a topic sentence that presents a point that supports your stance and that can be debated,

- Present summaries, paraphrases, or quotes from credible sources--evidence, in other words--that supports the point stated in the topic sentence, and

- Explain and interpret the evidence presented with your own, original commentary.

In an argumentative essay on why college athletes should be paid, for example, a body paragraph might look like this:

Thesis Statement : College athletes should not be paid because it would be a logistical nightmare for colleges and universities and ultimately cause negative consequences for college sports.

Body Paragraph #1: While the notion of paying college athletes is nice in theory, a major consequence of doing so would be the financial burden this decision would place on individual college sports programs. A recent study cited by the NCAA showed that only about 20 college athletic programs consistently operate in the black at the present time. If the NCAA allows student-athletes at all colleges and universities to be paid, the majority of athletic programs would not even have the funds to afford salaries for their players anyway. This would mean that the select few athletic programs that can afford to pay their athletes’ salaries would easily recruit the most talented players and, thus, have the tools to put together teams that destroy their competition. Though individual athletes would benefit from the NCAA allowing compensation for student-athletes, most athletic programs would suffer, and so would the spirit of healthy competition that college sports are known for.

If you read the example body paragraph above closely, you’ll notice that there’s a topic sentence that supports the claim made in the thesis statement. There’s also evidence given to support the claim made in the topic sentence--a recent study by the NCAA. Following the evidence, the writer interprets the evidence for the reader to show how it supports their opinion.

Following this topic sentence/evidence/explanation structure will help you construct a well-supported and developed argument that shows your readers that you’ve done your research and given your stance a lot of thought. And that's a key step in making sure you get an excellent grade on your essay!

Tip 5: Keep the Reader Thinking

The best argumentative essay conclusions reinterpret your thesis statement based on the evidence and explanations you provided throughout your essay. You would also make it clear why the argument about paying college athletes even matters in the first place.

There are several different approaches you can take to recap your argument and get your reader thinking in your conclusion paragraph. In addition to restating your topic and why it’s important, other effective ways to approach an argumentative essay conclusion could include one or more of the following:

While you don’t want to get too wordy in your conclusion or present new claims that you didn’t bring up in the body of your essay, you can write an effective conclusion and make all of the moves suggested in the bulleted list above.

Here’s an example conclusion for an argumentative essay on paying college athletes using approaches we just talked about:

Though it’s true that scholarships and financial aid are a form of compensation for college athletes, it’s also true that the current system of college sports places a lot of pressure on college athletes to behave like professional athletes in every way except getting paid. Future research should turn its attention to the various inequities within college sports and look at the long-term economic outcomes of these athletes. While college athletes aren't paid right now, that doesn’t necessarily mean that a paycheck is the best solution to the problem. To avoid the possibility of making the college athletics system even worse, people must consider the ramifications of paying college students and ensure that paying athletes doesn't create more harm than good.

This conclusion restates the argument of the essay (that college athletes shouldn't be paid and why), then uses the "Future Research" tactic to make the reader think more deeply about the topic.

If your conclusion sums up your thesis and keeps the reader thinking, you’ll make sure that your essay sticks in your readers' minds.

Should College Athletes Be Paid: Next Steps

Writing an argumentative essay can seem tough, but with a little expert guidance, you'll be well on your way to turning in a great paper . Our complete, expert guide to argumentative essays can give you the extra boost you need to ace your assignment!

Perhaps college athletics isn't your cup of tea. That's okay: there are tons of topics you can write about in an argumentative paper. We've compiled 113 amazing argumentative essay topics so that you're practically guaranteed to find an idea that resonates with you.

If you're not a super confident essay writer, it can be helpful to look at examples of what others have written. Our experts have broken down three real-life argumentative essays to show you what you should and shouldn't do in your own writing.

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

- Bachelor’s Degrees

- Master’s Degrees

- Doctorate Degrees

- Certificate Programs

- Nursing Degrees

- Cybersecurity

- Human Services

- Science & Mathematics

- Communication

- Liberal Arts

- Social Sciences

- Computer Science

- Admissions Overview

- Tuition and Financial Aid

- Incoming Freshman and Graduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Military Students

- International Students

- Early Access Program

- About Maryville

- Our Faculty

- Our Approach

- Our History

- Accreditation

- Tales of the Brave

- Student Support Overview

- Online Learning Tools

- Infographics

Home / Blog

Should College Athletes Be Paid? Reasons Why or Why Not

January 3, 2022

Tables of Contents

Why are college athletes not getting paid by their schools?

How do student athlete scholarships work, what are the pros and cons of compensation for college athletes, keeping education at the center of college sports.

Since its inception in 1906, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has governed intercollegiate sports and enforced a rule prohibiting college athletes to be paid. Football, basketball, and a handful of other college sports began to generate tremendous revenue for many schools in the mid-20th century, yet the NCAA continued to prohibit payments to athletes. The NCAA justified the restriction by claiming it was necessary to protect amateurism and distinguish “student athletes” from professionals.

The question of whether college athletes should be paid was answered in part by the Supreme Court’s June 21, 2021, ruling in National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Alston, et. al. The decision affirmed a lower court’s ruling that blocked the NCAA from enforcing its rules restricting the compensation that college athletes may receive.

- As a result of the NCAA v. Alston ruling, college athletes now have the right to profit from their name, image, and likeness (NIL) while retaining the right to participate in their sport at the college level. (The prohibition against schools paying athletes directly remains in effect.)

- Several states have passed laws that allow such compensation. Colleges and universities in those states must abide by these new laws when devising and implementing their own policies toward NIL compensation for college athletes.

Participating in sports benefits students in many ways: It helps them focus, provides motivation, builds resilience, and develops other skills that serve students in their careers and in their lives. The vast majority of college athletes will never become professional athletes and are happy to receive a full or partial scholarship that covers tuition and education expenses as their only compensation for playing sports.

Athletes playing Division I football, basketball, baseball, and other sports generate revenue for their schools and for third parties such as video game manufacturers and media companies. Many of these athletes believe it’s unfair for schools and businesses to profit from their hard work and talent without sharing the profits with them. They also point out that playing sports entails physical risk in addition to a considerable investment in time and effort.

This guide considers the reasons for and against paying college athletes, and the implications of recent court rulings and legislation on college athletes, their schools, their sports, and the role of the NCAA in the modern sports environment.

Back To Top

Discover a first-of-its-kind sport business management program

The online BS in Rawlings Sport Business Management from Maryville University will equip you with valuable skills in marketing, finance and public relations. No SAT or ACT scores required.

- Engage in a range of relevant course topics, from sports marketing to operations management.

- Gain real-world experience through professional internships.

The reasons why college athletes aren’t paid go back to the first organized sports competitions between colleges and universities in the late 19th century. Amateurism in college sports reflects the “ aristocratic amateurism ” of sports played in Europe at the time, even though most of the athletes at U.S. colleges had working-class backgrounds.

By the early 20th century, college football had gained a reputation for rowdiness and violence, much of which was attributed to the teams’ use of professional athletes. This led to the creation of the NCAA, which prohibited professionalism in college sports and enforced rules restricting compensation for college athletes. The rules are intended to preserve the amateurism of student participants. The NCAA justified the rules on two grounds:

- Fans would lose interest in the games if the players were professional athletes.

- Limiting compensation to capped scholarships ensures that college athletes remain part of the college community.

NCAA rules also prohibited college athletes from receiving payment to “ advertise, recommend, or promote ” any commercial product or service. Athletes were barred from participating in sports if they signed a contract to be represented by an agent as well. As a result of the NIL court decision, the NCAA will no longer enforce its rule relating to compensation for NIL activities and will allow athletes to sign contracts with agents.

Major college sports now generate billions in revenue for their schools each year

For decades, colleges and universities have operated under the assumption that scholarships are sufficient compensation for college athletes. Nearly all college sports cost more for the schools to operate than they generate in revenue for the institution, and scholarships are all that participants expect.

But while most sports don’t generate revenue, a handful, notably football and men’s and women’s basketball, stand out as significant exceptions to the rule:

- Many schools that field teams in the NCAA’s Division I football tier regularly earn tens of millions of dollars each year from the sport.

- The NCAA tournaments for men’s and women’s Division I basketball championships generated more than $1 billion in 2019 .

Many major colleges and universities generate a considerable amount of money from their athletic teams:

- The Power Five college sports conferences — the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), Big Ten, Big 12, Pac 12, and Southeastern Conference (SEC) — generated more than $2.9 billion in revenue from sports in fiscal 2020, according to federal tax records reported by USA Today .

- This figure represents an increase of $11 million from 2019, a total that was reduced because of restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- In the six years prior to 2020, the conferences recorded collective annual revenue increases averaging about $252 million.

What are name, image, likeness agreements for student athletes?

In recent years some college athletes at schools that field teams in the NCAA’s highest divisions have protested the restrictions placed on their ability to be compensated for third parties’ use of their name, image, and likeness. During the 2021 NCAA Division I basketball tournament known familiarly as March Madness, several players wore shirts bearing the hashtag “ #NotNCAAProperty ” to call attention to their objections.

Following the decision in NCAA v. Alston, the NCAA enacted a temporary policy allowing college athletes to enter into NIL agreements and other endorsements. The interim policy will be in place until federal legislation is enacted or new NCAA rules are created governing NIL contracts for college athletes.

- Student athletes are now able to sign endorsement deals, profit from their use of social media, and receive compensation for personal appearances and signing autographs.

- If they attend a school located in a state that has enacted NIL legislation, they are subject to any restrictions present in those state laws. As of mid-August 2021, 40 states had enacted laws governing NIL contracts for college athletes.

- If their school is in a state without such a law, the college or university will determine its own NIL policies, although the NCAA prohibits pay-for-play and improper recruiting inducements.

- Student athletes are allowed to sign with sports agents and enter into agreements with school boosters so long as the deals abide by state laws and school policies.

Within weeks of the NCAA policy change, premier college athletes began signing NIL agreements with the potential to earn them hundreds of thousands of dollars .

- Bryce Young, a sophomore quarterback for the University of Alabama, has nearly $1 million in endorsement deals.

- Quarterback Quinn Ewers decided to skip his last year of high school and enroll early at Ohio State University so he could make money from endorsements.

- A booster for the University of Miami pledged to pay each member of the school’s football team $500 for endorsing his business.

How will the change affect college athletes and their schools?

The repercussions of court decisions and state laws that allow college athletes to sign NIL agreements continue to be felt at campuses across the country, even though schools and athletes have received little guidance on how to manage the process.

- The top high school athletes in football, basketball, and other revenue-generating college sports will consider their potential for endorsement earnings while being recruited by various schools.

- The first NIL agreements highlight the disparity between what elite college athletes can expect to earn and what other athletes may realize. On one NIL platform, the average amount earned by Division I athletes was $471, yet one athlete made $210,000 in July alone.

- Most NIL deals at present are for small amounts, typically about $100 in free apparel, in exchange for endorsing a product on social media.

The presidents and other leaders of colleges and universities that field Division I sports have not yet responded to the changes in college athlete compensation other than to reiterate that they do not operate for-profit sports franchises. However, the NCAA requires that Division I sports programs be self-supporting, in contrast to sports programs at Division II and III institutions, which receive funding directly from their schools.

Many members of the Power 5 sports conferences have reported shortfalls in their operations, leading analysts to anticipate major structural reforms in the governing of college sports in the near future. The recent changes have also caused some people to believe the NCAA is no longer relevant or necessary.

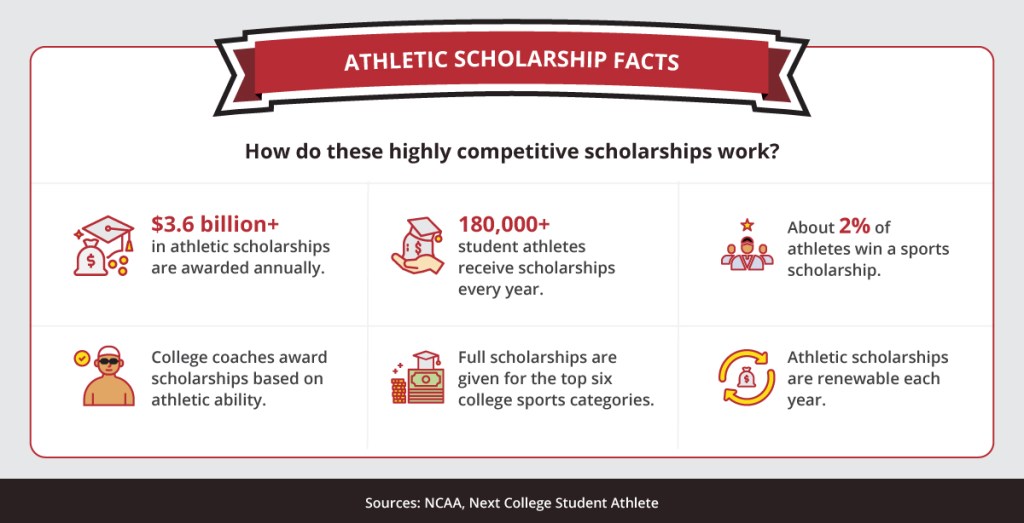

How do highly competitive athletic scholarships work? According to the NCAA and Next College Student Athlete: $3.6 billion+ in athletic scholarships are awarded annually, and 180,000+ student athletes receive scholarships every year. Additionally, about 2% of athletes win a sports scholarship; college coaches award scholarships based on athletic ability; full scholarships are given for the top six college sports categories; and athletic scholarships are renewable each year.

The primary financial compensation student athletes receive is a scholarship that pays all or part of their tuition and other college-related expenses. Other forms of financial assistance available to student athletes include grants, loans, and merit aid .

- Grants are also called “gift aid,” because students are not expected to pay them back (with some exceptions, such as failing to complete the course of study for which the grant was awarded). Grants are awarded based on a student’s financial need. The four types of grants awarded by the U.S. Department of Education are Federal Pell Grants , Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants , Iraq and Afghanistan Service Grants , and Teacher Education Assistance for College or Higher Education (TEACH) Grants .

- Loans are available to cover education expenses from government agencies and private banks. Students must pay the loans back over a specified period after graduating from or leaving school, including interest charges. EducationData.org estimates that as of 2020, the average amount of school-related debt owed by college graduates was $37,693.

- Merit aid is awarded based on the student’s academic, athletic, artistic, and other achievements. Athletic scholarships are a form of merit aid that typically cover one academic year at a time and are renewable each year, although some are awarded for up to four years.

Full athletic scholarships vs. partial scholarships

When most people think of a student athlete scholarship, they have in mind a full-ride scholarship that covers nearly all college-related expenses. However, most student athletes receive partial scholarships that may pay tuition but not college fees and living expenses, for example.

A student athlete scholarship is a nonguaranteed financial agreement between the school and the student. The NCAA refers to full-ride scholarships awarded to student athletes entering certain Division I sports programs as head count scholarships because they are awarded per athlete. Conversely, equivalency sports divide scholarships among multiple athletes, some of whom may receive a full scholarship and some a partial scholarship. Equivalency awards are divided among a team’s athletes at the discretion of the coaches, as long as they do not exceed the allowed scholarships for their sport.

These Division I sports distribute scholarships per head count:

- Men’s football

- Men’s basketball

- Women’s basketball

- Women’s volleyball

- Women’s gymnastics

- Women’s tennis

These are among the Division I equivalency sports for men:

- Track and field

- Cross-country

These are the Division I equivalency sports for women:

- Field hockey

All Division II and National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) sports programs distribute scholarships on an equivalency basis. Division III sports programs do not award sports scholarships, although other forms of financial aid are available to student athletes at these schools.

How college athletic scholarships are awarded

In most cases, the coaching staff of a team determines which students will receive scholarships after spending time scouting and recruiting. The NCAA imposes strict rules for recruiting student athletes and provides a guide to help students determine their eligibility to play college sports.

Once a student has received a scholarship offer from a college or university, the person may sign a national letter of intent (NLI), which is a voluntary, legally binding contract between an athlete and the school committing the student to enroll and play the designated sport for that school only. The school agrees to provide financial aid for one academic year as long as the student is admitted and eligible to receive the aid.

After the student signs an NLI, other schools are prohibited from recruiting them. Students who have signed an NLI may ask the school to release them from the commitment; if a student attends a school other than the one with which they have an NLI agreement, they lose one full year of eligibility and must complete a full academic year at the new school before they can compete in their sport.

Very few student athletes are awarded a full scholarship, and even a “full” scholarship may not pay for all of a student’s college and living expenses. The average Division I sports scholarship in the 2019-20 fiscal year was about $18,000, according to figures compiled by ScholarshipStats.com, although some private universities had average scholarship awards that were more than twice that amount. However, EducationData.org estimates that the average cost of one year of college in the U.S. is $35,720. They estimate the following costs by type of school.

- The average annual cost for an in-state student attending a public four-year college or university is $25,615.

- Average in-state tuition for one year is $9,580, and out-of-state tuition costs an average of $27,437.

- The average cost at a private university is $53,949 per academic year, about $37,200 of which is tuition and fees.

Student athlete scholarship resources

- College Finance, “Full-Ride vs. Partial-Ride Athletic Scholarships” — The college expenses covered by full athletic scholarships, how to qualify for partial athletic scholarships, and alternatives to scholarships for paying college expenses

- Student First Educational Consulting, “Athletic Scholarship Issues for 2021-2022 and Beyond” — A discussion of the decline in the number of college athletic scholarships as schools drop athletic programs, and changes to the rules for college athletes transferring to new schools

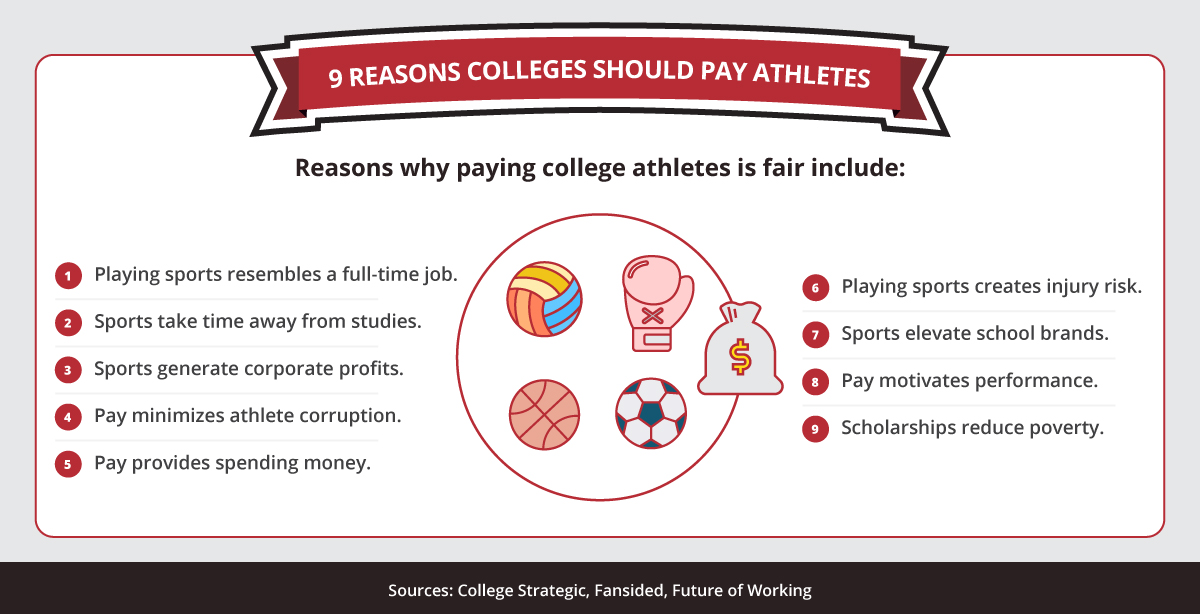

According to College Strategic, Fansided, and Future of Working, reasons why paying college athletes is fair include: 1. Playing sports resembles a full-time job. 2. Sports take time away from studies. 3. Sports generate corporate profits. 4. Pay minimizes athlete corruption. 5. Pay provides spending money. 6. Playing sports creates injury risk. 7. Sports elevate school brands. 8. Pay motivates performance. 9. Scholarships reduce poverty.

There are many reasons why student athletes should be paid, but there are also valid reasons why student athletes should not be paid in certain circumstances. The lifting of NCAA restrictions on NIL agreements for college athletes has altered the landscape of major college sports but will likely have little or no impact on the majority of student athletes, who will continue to compete as true amateurs.

Reasons why student athletes should be paid

The argument raised most often in favor of allowing college athletes to receive compensation is that colleges and universities profit from the sports they play but do not share the proceeds with the athletes who are the ultimate source of that profit.

- In 2017 (the most recent year for which figures are available), the NCAA recorded $1.07 billion in revenue. The organization’s president earned $2.7 million in 2018, and nine other NCAA executives had salaries greater than $500,000 that year.

- Elite college coaches earn millions of dollars a year in salary, topped by University of Alabama football coach Nick Saban’s $9.3 million annual salary.

- Many of the athletes at leading football and basketball programs are from low-income families, and the majority will not become professional athletes.

- College athletes take great physical risks to play their sports and put their future earning potential at risk. In school they may be directed toward nonchallenging courses, which denies them the education their fellow students receive.

Reasons why student athletes should not be paid

Opponents to paying college athletes rebut these arguments by pointing to the primary role of colleges and universities: to provide students with a rewarding educational experience that prepares them for their professional careers. These are among the reasons they give for not paying student athletes.

- Scholarships are the fairest form of compensation for student athletes considering the financial strain that college athletic departments are under. Most schools in Division I, II, and III spend more money on athletics than they receive in revenue from the sports.

- College athletes who receive scholarships are presented with an opportunity to earn a valuable education that will increase their earning power throughout their career outside of sports. A Gallup survey of NCAA athletes found that 70% graduate in four years or fewer , compared to 65% of all undergraduate students.

- Paying college athletes will “ diminish the spirit of amateurism ” that distinguishes college sports from their professional counterparts. Limiting compensation for playing a sport to the cost of attending school avoids creating a separate class of students who are profiting from their time in school.

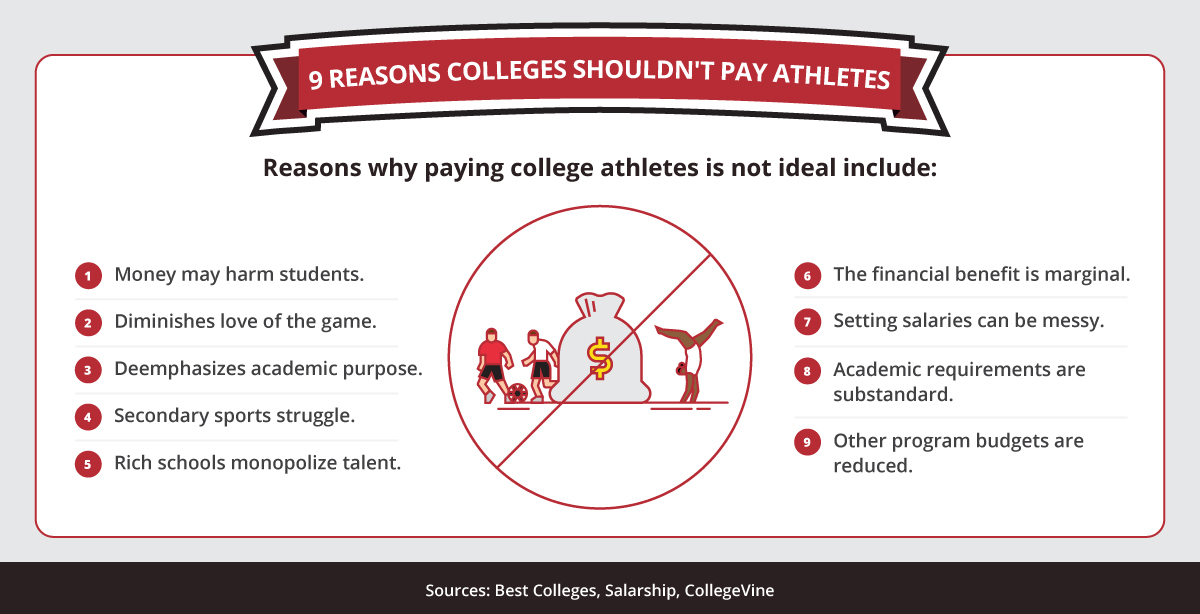

According to Best Colleges, Salarship, and CollegeVine, reasons why paying college athletes is less than ideal include: 1. Money may harm students. 2. Pay diminishes love of the game. 3. Pay deemphasizes academic purpose. 4. Secondary sports struggle. 5. Rich schools monopolize talent. 6. The financial benefit is marginal. 7. Setting salaries can be messy. 8. Academic requirements are substandard. 9. Other program budgets are reduced.

How do college athlete endorsements work?

Soon after the Supreme Court released its decision in NCAA v. Alston, the NCAA issued guidelines for schools that allow college athletes to make money from product endorsements, social media accounts, autographs, and other uses of their name, image, or likeness. This counters the NCAA’s longstanding opposition to student athletes profiting from endorsements. At present, implementation of the guidelines varies from school to school and state to state, which means athletes at some institutions may benefit more from NIL agreements than those attending other schools.

Several NIL consultancy firms are actively soliciting endorsements from college athletes in the aftermath of the rule change.

- Highly touted 19-year-old basketball recruit Hercy Miller, who joined the Tennessee State University basketball team in 2021, signed a $2 million endorsement deal with Web Apps America.

- University of Michigan quarterback Cade McNamara has entered into an endorsement deal with cryptocurrency company More Management that will pay him in cryptocurrency .

- Twin sisters Haley and Hanna Cavinder of the Fresno State University basketball team have marketing agreements to promote Boost Mobile and Six Star Pro Nutrition to the 3.3 million followers of their TikTok account.

- Gable Steveson, a wrestler for the University of Minnesota, entered into an endorsement deal with the delivery service Gopuff; Steveson has 245,000 followers on Instagram and 30,000 on Twitter.

Despite the rush of high-profile college athletes signing endorsement deals, some educators and analysts express concern about the impact of the endorsements on schools, athletes, and college sports.

- Schools with more favorable endorsement rules may entice student athletes away from the schools they are currently attending.

- Likewise, states that have enacted endorsement laws that provide more earning potential for college athletes may see more top recruits choosing to attend schools in those states.

- The time college athletes spend meeting the requirements of their endorsement contracts could detract from study and practice time. This can have an adverse effect on their education and athletic careers — if they are unable to maintain grade requirements, for example, they may be disqualified from playing.

- If a college athlete’s performance in the sport declines, they may be less likely to attract and retain endorsement deals. While the NCAA has banned NIL agreements based on the athlete meeting specific performance criteria, the group acknowledges that a student’s athletic performance may enhance their NIL value .

- Because of complicated contracts and tax laws, student athletes will have to rely on agents, advisers, and managers, which may leave them vulnerable to exploitation.

From the onset of intercollegiate sports, students have benefited from their participation by learning dedication to their sport, building relationships, and being part of a team. Sports allow students to acquire many important values, such as fair competition and physical and mental health. Education should remain at the forefront of all aspects of college, including sports, whether or not collegiate athletes are paid.

Infographic Source

Best Colleges, “Should College Athletes Be Paid?”

College Strategic, “Why College Athletes Should Be Paid”

CollegeVine, “Should College Athletes Be Paid? Pros and Cons”

Fansided, “64 Reasons College Athletes Need to Be Paid”

Future of Working, “17 Advantages and Disadvantages of Paying College Athletes”

NCAA, “Scholarships”

Next College Student Athlete, “What Are the Different Types of Offers I Could Get?”

Salarship, “Should College Athletes Be Paid: Pros and Cons”

Bring us your ambition and we’ll guide you along a personalized path to a quality education that’s designed to change your life.

Take Your Next Brave Step

Receive information about the benefits of our programs, the courses you'll take, and what you need to apply.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

Should College Athletes Be Paid? Pros and Cons

Do you know how to improve your profile for college applications.

See how your profile ranks among thousands of other students using CollegeVine. Calculate your chances at your dream schools and learn what areas you need to improve right now — it only takes 3 minutes and it's 100% free.

Show me what areas I need to improve

What’s Covered:

History of the debate: should college athletes be paid, why college athletes should be paid.

- Why College Athletes Shouldn’t Be Paid

- Where To Get Your Essay Edited For Free

College athletics provide big benefits for many schools: they increase their profile, generate millions of dollars in revenue, and have led to one of the most contentious questions in sports— should college athletes be paid? Like other difficult questions, there are good arguments on both sides of the issue of paying college athletes.

Historically, the debates over paying college athletes have only led to more questions, which is why it’s raged on for more than a century. Perhaps the earliest group to examine the quandary was Andrew Carnegie’s Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, which produced a mammoth study in 1929 of amateur athletes and the profits they generate for their universities. You don’t have to get past the preface to find questions that feel at home in today’s world:

- “What relation has this astonishing athletic display to the work of an intelligence agency like a university?”

- “How do students, devoted to study, find either the time or the money to stage so costly a performance?”

Many of the questions asked way back in 1929 continue to resurface today, and many of them have eventually ended up seeking answers in court. The first case of note came in the 1950s, when the widow of Fort Lewis football player Ray Dennison took the college all the way to the Colorado Supreme Court in an effort to collect a death benefit after he was killed playing football. She lost the case, but future generations would have more success and have slowly whittled away at arguments against paying athletes.

The most noticeable victory for athletes occurred in 2019, when California Governor, Gavin Newsom, signed legislation effectively allowing college athletes in the state to earn compensation for the use of their likeness, sign endorsement deals, and hire agents to represent them.

The court fights between college athletes and the NCAA continue today—while not exactly about payment, a case regarding whether or not schools can offer athletes tens of thousands of dollars in education benefits such as computers, graduate scholarships, tutoring, study abroad, and internships was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in March 2021. A decision is expected in June 2021.

There are a number of great reasons to pay college athletes, many of which will not only improve the lives of student-athletes, but also improve the product on the field and in the arena.

College Athletes Deserve to Get Paid

In 2019, the NCAA reported $18.9 billion in total athletics revenue. This money is used to finance a variety of paid positions that support athletics at colleges and universities, including administrators, directors, coaches, and staff, along with other employment less directly tied to sports, such as those in marketing and media. The only people not receiving a paycheck are the stars of the show: the athletes.

A testament to the disparate allocation of funds generated by college sports, of the $18.9 billion in athletics revenue in 2019, $3.6 billion went toward financial aid for student-athletes, and $3.7 billion was used for coaches’ compensation. A February 2020 USA Today article found that the average total pay for Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) college football head coaches in 2020-21 was $2.7 million. The highest-paid college football coach—the University of Alabama’s Nick Saban—earns $9.3 million a year and is the highest-paid public employee in the country. He is not alone, college coaches dominate the list of public employees with the largest salaries.

If there’s money to provide college coaches with lavish seven-figure salaries (especially at public institutions), why shouldn’t there be funds to pay college athletes?

Vital Support for Athletes

A 2011 study published by the National College Players Association (NCPA) found that an overwhelming number of students on full athletics scholarships live below the federal poverty line—85% of athletes who live on campus and 86% athletes who live off-campus. “Full scholarship” itself is a misnomer; the same study found that the average annual scholarship for FBS athletes on “full” scholarships was actually $3,222. Find out more information about athletic scholarships .

Paying student-athletes would help eliminate the need for these student-athletes to take out loans, burden their families for monetary support, or add employment to their already busy schedules. The NCAA limits in-season practice time to 20 hours a week, but a 2008 NCAA report shows that in-season student-athletes commonly spent upward of 30 and 40 hours a week engaged in “athletic activities.”

Encouraged to Stay in College Longer

A report produced by the NCPA and Drexel University estimated the average annual fair market value of big-time college football and men’s basketball players between 2011 and 2015 was $137,357 and $289,031, respectively, and concluded that football players only receive about 17% of their fair market value, while men’s basketball players receive approximately 8% of theirs.

If colleges paid athletes even close to their worth, they would provide an incentive for the athletes to stay in college and earn degrees, rather than leaving college for a paycheck. This would also help keep top talents playing for college teams, improve the level of competition, and potentially lead to even higher revenue. On a side note, this would incentivize athletes to complete their degree, making them more employable after the end of their athletic career.

Limit Corruption

Just because there are rules prohibiting the compensation of college athletes doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen, and over the years there have been numerous scandals. For example, in 2009, six ex-University of Toledo players were indicted in a point-shaving scheme , and in 2010, Reggie Bush returned his Heisman Trophy after allegations that he was given hundreds of thousands of dollars from sports agents while he played for USC.

Paying college athletes will likely not totally eliminate corruption from college sports, but putting athletes in a less-precarious financial position would be a good step toward avoiding external influence, especially when you consider some of the players involved in the University of Toledo point-shaving scandal were paid as little as $500.

It’s a Job (and a Dangerous One)

As mentioned before, college athletes can put in upward of 40 hours a week practicing, training, and competing—being a “student-athlete” is a challenge when you’re devoting full-time hours to athletics. A New York Times study found a 0.20-point difference in average GPA between recruited male athletes and non-athletes. The difference is less pronounced among females, with non-athletes averaging a 3.24 GPA and recruited women athletes at 3.18.

It’s not just the time commitment that playing college athletics puts on student-athletes, it’s the risk to their health. A 2009-2010 CDC report found that more than 210,000 injuries are sustained by NCAA student-athletes each year. Full athletic scholarships are only guaranteed a year at a time, meaning student-athletes are one catastrophic injury away from potentially losing their scholarship. That is to say nothing of the lasting effects of an injury, like head traumas , which made up 7.4% of all injuries in college football players between 2004 and 2009.

Discover your chances at hundreds of schools

Our free chancing engine takes into account your history, background, test scores, and extracurricular activities to show you your real chances of admission—and how to improve them.

Why College Athletes Should Not Be Paid

There are a lot of great reasons why college athletes should be paid, but there are also some compelling reasons why college athletes should not be paid—and why not paying athletes is actually good for both the institutions and athletes.

Compensation Conundrum

One of the most common reasons cited against paying college players is compensation. Will all college athletes get compensated equally? For example, will the star quarterback receive the same amount as the backup catcher on the softball team? A 2014 CNBC article estimated that Andrew Wiggins, a University of Kansas forward (and soon-to-be first-overall draft pick), had a fair market value of around $1.6 million.

Similarly, will compensation take into account talent? Will the All-American point guard get the same amount as the captain of the swim team? In all likelihood, paying college athletes will benefit big-time, revenue-generating sports and hurt less popular sports.

Eliminate Competitive Balance

According to the NCAA , in 2019, the 65 Power Five schools exceeded revenue by $7 million, while all other Division I colleges had a $23 million deficit between expenses and revenue. If college athletes were to get paid, then large, well-funded schools such as those of the Power Five would be best positioned to acquire top talent and gain a competitive advantage.

From a student’s point of view, paying college athletes will alter their college experience. No longer would fit, college, university reputation, and values factor into their college decisions—rather, choices would be made simply based on who was offering the most money.

Professionalism vs. the Classroom

There’s a feeling that paying college athletes sends the wrong message and incentivizes them to focus on athletics instead of academics, when the reality is that very few college athletes will go on to play sports professionally. Just 1.6% of college football players will take an NFL field. NCAA men’s basketball players have even slimmer odds of playing in a major professional league ( 1.2% ), while the chances of a professional career are particularly grim for women basketball players, at a mere 0.8% .

Although the odds of a college athlete turning pro are low, the probability of them earning a degree is high, thanks in part to the academic support athletes are given. According to data released by the NCAA, 90% of Division I athletes enrolled in 2013 earned a degree within six years.

It Will End Less-Popular, Unprofitable Sports

If colleges and universities pay their athletes, there is a fear that resources will only go to popular, revenue-generating sports. Programs like football and men’s basketball would likely benefit greatly, but smaller, unprofitable sports such as gymnastics, swimming and diving, tennis, track and field, volleyball, and wrestling could find themselves at best cash-strapped and, at the worst, cut altogether.

It’s just not less-popular sports that paying athletes could threaten—women’s programs could also find themselves in the crosshairs of budget-conscious administrators. Keep in mind, it was just in March 2021 that the NCAA made national news for its unequal treatment of the men’s and women’s NCAA basketball tournaments.

Financial Irresponsibility

Former ESPN, and current FOX Sports, personality Colin Cowherd made news in 2014 when he voiced a popular argument against paying college athletes: financial irresponsibility. In Cowherd’s words:

“I don’t think paying all college athletes is great… Not every college is loaded, and most 19-year-olds [are] gonna spend it—and let’s be honest, they’re gonna spend it on weed and kicks! And spare me the ‘they’re being extorted’ thing. Listen, 90 percent of these college guys are gonna spend it on tats, weed, kicks, Xboxes, beer and swag. They are, get over it!”

A look at the professional ranks bolsters Cowherd’s argument about athletes’ frivolous spending. According to CNBC , 60% of NBA players go broke within five years of departing the league and 78% of former NFL players experience financial distress two years after retirement.

Writing an Essay on This? Where to Get Your Essay Edited for Free

Writing an essay on whether college athletes should or shouldn’t be paid? CollegeVine can help! Our peer review tool allows you to receive feedback and learn the strengths and weaknesses of your essay for free.

Looking for more debate, speech, or essay topics? Check out these other CollegeVine articles for ideas:

- 52 Argumentative Essays Ideas that are Actually Interesting

- 52 Persuasive Speech Topics That Are Actually Engaging

- 60 Debate Topics for High Schoolers

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

More From Forbes

Why the public strongly supports paying college athletes.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

The Sportico/Harris poll shows a majority of people support players like Myan Williams of the Ohio ... [+] State Buckeyes earning money as student-athletes. (Photo by Gaelen Morse/Getty Images)

When student-athletes in 2021 were finally provided the chance to earn money from their name, image and likeness , some feared it would be the end of college sports as we knew it.

Fast forward two years, and the majority of Americans seem ready to let them bank even more bucks.

Nearly 70% of U.S. adults said college athletes should be able to receive direct compensation from their school when asked in a survey conducted this summer by Sportico and The Harris Poll.

“It’s about time,” sports attorney Luke Fedlam , founder of Advance NIL , said. “We have seen over the last 20 years the explosion in the commercialization of college sports. Look at the NCAA [March Madness] tournament. So much money is being made on student-athletes’ abilities. The idea that people are still coming around to is understanding and believing college athletes should receive compensation just makes sense.”

The poll, which surveyed 2,018 people nationally from Aug. 11–13, found 67% agreed college athletes should receive direct compensation from their universities, while 74% of respondents supported athletes’ ability to profit from NIL.

“I think it's good that athletes are getting their share,” Ohio University sports business professor B. David Ridpath said. “People are starting to come to the realization that not only is it inevitable, it's really the right thing to do.”

Best High-Yield Savings Accounts Of 2024

Best 5% interest savings accounts of 2024.

NIL became part of the sports landscape in June 2021 when the NCAA Board of Directors lifted NCAA restrictions on athlete payments for everything from sponsorships to personal appearances.

That same month, the Supreme Court voted unanimously that the NCAA can no longer limit education-related benefits that colleges offer athletes beyond tuition, including computers and internships. As part of what’s known as the Alston ruling, schools are now allowed to annually provide athletes with as much as $5,980 in education-related compensation .

Fedlam said the amount of money being poured into and flowing from collegiate sports has made it clear they are no longer purely about amateurism and love of competition. That means the move toward paying college athletes is an inevitability, not a debate.

“If college sports were solely about education and the benefits that could come from that, college sports would look entirely different,” Fedlam said. “Do we ruin college sports when we pay tens of millions to schools for broadcast rights, when March Madness makes $1 billion, when schools on the West Coast are aligning with Midwest and East Coast conferences to earn more compensation? That’s where sports have come.”

The survey also revealed 64% of respondents think college athletes should become university employees, an idea NCAA president Charlie Baker shot down at the April LEAD1 Association’s annual spring meeting, proclaiming, “I think student-athletes want to be student-athletes, and it’s up to us to figure out how to make that work for them in a variety of environments and in circumstances that are different.”

Democrats were much more in favor of direct compensation for college athletes than Republicans (78%-56%), while people who follow college sports favored the change at 78%, compared to 56% for those who do not follow sports closely.

More than 80% of respondents ages 18-41 supported athlete payments, while people over age 58 were just 48% in favor.

Ridpath said it sounds good in theory to allow athletes to be paid while in college, but to older fans more set in their ways, it is clearly far less accepted.

“The younger demographics are much more savvy than we were because they have access to more information,” he said. “This is the reality now.”

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Join The Conversation

One Community. Many Voices. Create a free account to share your thoughts.

Forbes Community Guidelines

Our community is about connecting people through open and thoughtful conversations. We want our readers to share their views and exchange ideas and facts in a safe space.

In order to do so, please follow the posting rules in our site's Terms of Service. We've summarized some of those key rules below. Simply put, keep it civil.

Your post will be rejected if we notice that it seems to contain:

- False or intentionally out-of-context or misleading information

- Insults, profanity, incoherent, obscene or inflammatory language or threats of any kind

- Attacks on the identity of other commenters or the article's author

- Content that otherwise violates our site's terms.

User accounts will be blocked if we notice or believe that users are engaged in:

- Continuous attempts to re-post comments that have been previously moderated/rejected

- Racist, sexist, homophobic or other discriminatory comments

- Attempts or tactics that put the site security at risk

- Actions that otherwise violate our site's terms.

So, how can you be a power user?

- Stay on topic and share your insights

- Feel free to be clear and thoughtful to get your point across

- ‘Like’ or ‘Dislike’ to show your point of view.

- Protect your community.

- Use the report tool to alert us when someone breaks the rules.

Thanks for reading our community guidelines. Please read the full list of posting rules found in our site's Terms of Service.

Survey shows most people want college athletes to be paid. You hear that, NCAA?

It's difficult for any fair-minded american to look at the vast amounts of money flowing into college sports and not see hypocrisy in its reliance on an unpaid labor force. .

When the legal threats to amateurism began to emerge about a dozen years ago, the NCAA’s main strategy was to claim that college sports would become less popular if athletes earned money.

Administrators said it repeatedly in the media. They said it in court. They even threatened to take their ball and go home if schools had to pay the athletes who help generate hundreds of millions of dollars playing college football and basketball.

And now they all need to admit that they were wrong. Historically, spectacularly, wrong.

A new national survey commissioned by Sportico in cooperation with The Harris Poll found that 67 percent of American adults believe college athletes should be paid — not just through name, image and likeness payments but in direct compensation from the school.

Further, 64 percent of those surveyed believed athletes should be able to claim status as employees, and 59 percent were in favor of college athletes being able to bargain as a union.

The numbers were relatively consistent across a variety of demographic groups. Whether man or woman, Democrat or Republican, white or Black, the notion of paying college athletes was supported by a majority of respondents. The only category registering less than 50 percent approval was respondents over the age of 58.

This is only one poll and one data point in a long-running narrative, but the trends are clear. College sports officials would be wise to pay attention.

TOP 25 RANKINGS: A closer look at every team in college football's preseason coaches poll

A similar survey conducted in 2014 by the Washington Post and ABC News found that only 33 percent supported paying college athletes, including just 24 percent of white people. So when former NCAA president Mark Emmert testified during the O’Bannon vs. NCAA trial in 2014 that paying athletes would be “tantamount to converting it into minor league sports, and we know that in the U.S., minor league sports aren’t very successful either for fan support or for the fan experience,” he had at least some data to support it.

But in the real world, there’s never been a link between the popularity of a sport and players being unable to make money.

Golf and tennis exploded across the world once they became fully professionalized. The International Olympic Committee was staunchly against including professional athletes until the 1980s. Once they opened the floodgates, the Olympics only got bigger and more popular. And even amidst all the consternation over the messy implementation of NIL in college, there’s absolutely nothing in the data from ticket sales to television ratings to suggest that fans are being turned off because the star quarterback has a nice car to drive.

It's been the same story time and time again throughout history: People like watching the games far more than they care about who’s getting paid to play them.

So perhaps former Big Ten commissioner Jim Delany was slightly out of touch when he said during the O’Bannon trial: “These games are owned by the institution, and the notion of paying athletes for participation in these games is foreign to the notion of amateurism.”

Maybe Delany and his colleagues really believed that at the time — or had convinced themselves of it — because they had spent their entire careers in the amateur model and had no other frame of reference for what college sports would look like if the athletes had the same access to large amounts of money that coaches and administrators did.

Or maybe they always knew they were full of it and used whatever rhetoric they could to preserve a dying system.