Evidence-Based Practice (EBP)

- The EBP Process

- Forming a Clinical Question

- Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria

- Acquiring Evidence

- Appraising the Quality of the Evidence

- Writing a Literature Review

- Finding Psychological Tests & Assessment Instruments

What Is a Literature Review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis of scholarly writings that are related directly to your research question. Put simply, it's a critical evaluation of what's already been written on a particular topic . It represents the literature that provides background information on your topic and shows a connection between those writings and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand-alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

What a Literature Review Is Not:

- A list or summary of sources

- An annotated bibliography

- A grouping of broad, unrelated sources

- A compilation of everything that has been written on a particular topic

- Literary criticism (think English) or a book review

Why Literature Reviews Are Important

- They explain the background of research on a topic

- They demonstrate why a topic is significant to a subject area

- They discover relationships between research studies/ideas

- They identify major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic

- They identify critical gaps and points of disagreement

- They discuss further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies

To Learn More about Conducting and Writing a Lit Review . . .

Monash University (in Australia) has created several extremely helpful, interactive tutorials.

- The Stand-Alone Literature Review, https://www.monash.edu/rlo/assignment-samples/science/stand-alone-literature-review

- Researching for Your Literature Review, https://guides.lib.monash.edu/researching-for-your-literature-review/home

- Writing a Literature Review, https://www.monash.edu/rlo/graduate-research-writing/write-the-thesis/writing-a-literature-review

Keep Track of Your Sources!

A citation manager can be helpful way to work with large numbers of citations. See UMSL Libraries' Citing Sources guide for more information. Personally, I highly recommend Zotero —it's free, easy to use, and versatile. If you need help getting started with Zotero or one of the other citation managers, please contact a librarian.

- << Previous: Appraising the Quality of the Evidence

- Next: Finding Psychological Tests & Assessment Instruments >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 2:44 PM

- URL: https://libguides.umsl.edu/ebp

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland, Starting Immediately

Due to the downward trend in respiratory viruses in Maryland, masking is no longer required but remains strongly recommended in Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. Read more .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Center for Nursing Inquiry

Evidence-based practice, what is ebp.

As nurses, we often hear the term evidence-based practice (EBP). But, what does it actually mean? EBP is a process used to review, analyze, and translate the latest scientific evidence. The goal is to quickly incorporate the best available research, along with clinical experience and patient preference, into clinical practice, so nurses can make informed patient-care decisions ( Dang et al., 2022 ). EBP is the cornerstone of clinical practice. Integrating EBP into your nursing practice improves quality of care and patient outcomes.

How do I get involved in EBP?

As a nurse, you will have plenty of opportunities to get involved in EBP. Take that “AHA” moment. Do you think there’s a better way to do something? Let’s turn to the evidence and find out!

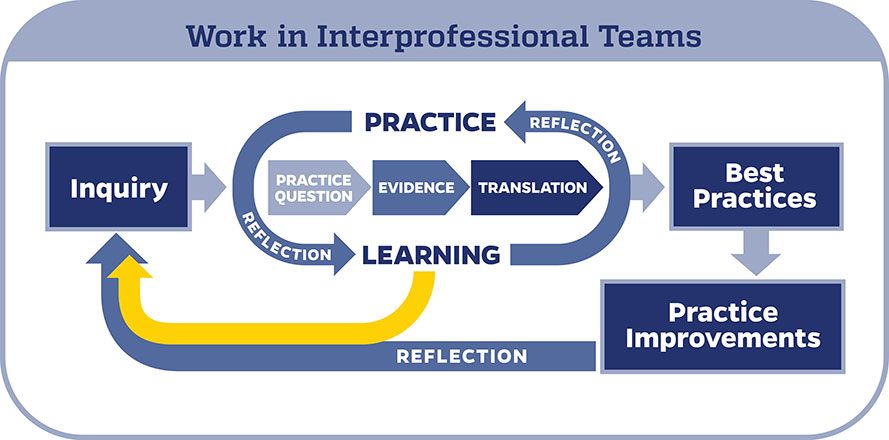

When conducting an EBP project, it is important to use a model to help guide your work. In the Johns Hopkins Health System, we use the Johns Hopkins Evidence-Based Practice (JHEBP) model. It is a three-phase approach referred to as the PET process: practice question, evidence, and translation. In the first phase, the team develops a practice question by identifying the patient population, interventions, and outcomes (PICO). In the second phase, a literature search is performed, and the evidence is appraised for strength and quality. In the third phase, the findings are synthesized to develop recommendations for practice.

The JHEBP model is accompanied by user-friendly tools. The tools walk you through each phase of the project. Johns Hopkins nurses can access the tools via our Inquiry Toolkit . The tools are available to individuals from other institutions via the Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing (IJHN) .

If you’re interested in learning more about the JHEBP model and tools, Johns Hopkins nurses have access to a free online course entitled JHH Nursing | Central | Evidence-Based Practice Series in MyLearning. The course follows the JHEBP process from beginning to end and provides guidance to the learner on how to use the JHEBP tools. The course is available to individuals from other institutions for a fee via the Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing (IJHN) .

Where should I start?

All EBP projects need to be submitted to the Center for Nursing Inquiry for review. The CNI ensures all nurse-led EBP projects are high-quality and value added. We also offer expert guidance and support, if needed.

Who can help me?

The Center for Nursing Inquiry can answer any questions you may have about the JHEBP tools. All 10 JHEBP tools can be found in our Inquiry Toolkit : project management guide, question development tool, stakeholder analysis tool, evidence level and quality guide, research evidence appraisal tool, non-research evidence appraisal tool, individual evidence summary tool, synthesis process and recommendations tool, action planning tool, and dissemination tool. The tools walk you through each phase of an EBP project.

The Welch Medical Library serves the information needs of the faculty, staff, and students of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Nursing and Public Health. Often, one of the toughest parts of conducting an EBP project is finding the evidence. The informationist assigned to your department can assist you with your literature search and citation management.

When do I share my work?

Your project is complete. Now what? It’s time to share your project with the scholarly community.

To prepare your EBP project for publication, use the JHEBP Dissemination Tool . The JHEBP Dissemination Tool (Appendix J) details what to include in each section of your manuscript, from the introduction to the discussion, and shows you which EBP appendices correspond to each part of a scientific paper. You can find the JHEBP Dissemination Tool in our Inquiry Toolkit .

You can also present your project at a local, regional, or national conference. Poster and podium presentation templates are available in our Inquiry Toolkit .

To learn more about sharing your project, check out our Abstract & Manuscript Writing webinar and our Poster & Podium Presentations webinar !

Submit Your Project

Do you have an idea for an EBP project?

University Libraries

- Ohio University Libraries

- Library Guides

Evidence-based Practice in Healthcare

- Performing a Literature Review

- EBP Tutorials

- Question- PICO

- Definitions

- Systematic Reviews

- Levels of Evidence

- Finding Evidence

- Filter by Study Type

- Too Much or Too Little?

- Critical Appraisal

- Quality Improvement (QI)

- Contact - Need Help?

Hanna's Performing a qualitity literature review presentation slides

- Link to the PPT slides via OneDrive anyone can view

Characteristics of a Good Literature Review in Health & Medicine

Clear Objectives and Research Questions : The review should start with clearly defined objectives and research questions that guide the scope and focus of the review.

Comprehensive Coverage : Include a wide range of relevant sources, such as research articles, review papers, clinical guidelines, and books. Aim for a broad understanding of the topic, covering historical developments and current advancements. To do this, an intentional and minimally biased search strategy.

- Link to relevant databases to consider for a comprehensive search (search 2+ databases)

- Link to the video "Searching your Topic: Strategies and Efficiencies" by Hanna Schmillen

- Link to the worksheet "From topic, to PICO, to search strategy" to help researchers work through their topic into an intentional search strategy by Hanna Schmillen

Transparency and Replicability : The review process, search strategy, should be transparent, with detailed documentation of all steps taken. This allows others to replicate the review or update it in the future.

Appraisal of Studies Included : Each included study should be critically appraised for methodological quality and relevance. Use standardized appraisal tools to assess the risk of bias and the quality of evidence.

- Link to the video " Evaluating Health Research" by Hanna Schmillen

- Link to evaluating and appraising studies tab, which includes a rubric and checklists

Clear Synthesis and Discussion of Findings : The review should provide a thorough discussion of the findings, including any patterns, relationships, or trends identified in the literature. Address the strengths and limitations of the reviewed studies and the review itself. Present findings in a balanced and unbiased manner, avoiding over interpretation or selective reporting of results.

Implications for Practice and Research : The review should highlight the practical implications of the findings for medical practice and policy. It should also identify gaps in the current literature and suggest areas for future research.

Referencing and Citation : Use proper citation practices to credit original sources. Provide a comprehensive reference list to guide readers to the original studies.

- Link to Citation Style Guide, includes tab about Zotero

Note: A literature review is not a systematic review. For more information about systematic reviews and different types of evidence synthesis projects, see the Evidence Synthesis guide .

- << Previous: Quality Improvement (QI)

- Next: Contact - Need Help? >>

Evidence-Based Practice: Literature Reviews / Systematic Reviews

- What is EBP?

- PICO and SPIDER

- More Resources

- Types of Research

- Levels of Evidence

- How to Search for Evidence

- Where to Search for Evidence

- Literature Reviews / Systematic Reviews

- Clinical Colleagues as a Source of Evidence

- What is Being Appraised?

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Step 4: Apply

- Step 5: Assess/Audit

- EBP Resources by Discipline

Introduction

- is based on database searches

- summarises the results of research

- has the aim of objectively discussing a specific topic or theme.

There are many types of literature review, but two of the main ones are:

- narrative (or traditional) review

- systematic review.

The image above describes common review types in terms of speed, detail, risk of bias, and comprehensiveness.

For more information on all types of literature reviews , see the Library's Literature Review guide. This guide includes a wealth of information on all types of reviews.

For more information on systematic reviews , see the Library's Systematic and systematic-like reviews guide.

[ Image attribution : "Schematic of the main differences between the types of literature review" by Brennan, M. L., Arlt, S. P., Belshaw, Z., Buckley, L., Corah, L., Doit, H., Fajt, V. R., Grindlay, D., Moberly, H. K., Morrow, L. D., Stavisky, J., & White, C. (2020). Critically Appraised Topics (CATs) in veterinary medicine: Applying evidence in clinical practice. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7 , 314. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00314 is licensed under CC BY 3.0 .]

- << Previous: Where to Search for Evidence

- Next: Clinical Colleagues as a Source of Evidence >>

- Last Updated: Jun 21, 2024 9:42 AM

- URL: https://libguides.csu.edu.au/ebp

Charles Sturt University is an Australian University, TEQSA Provider Identification: PRV12018. CRICOS Provider: 00005F.

NUR 506 - Evidence Based Practice

Need more help, ask a librarian.

SNHU Connect

Nursing & Healthcare Learning Community

What is a literature review?

Part of your final project is to conduct a literature review that shows a progressive development of ideas and explains the current state of the research surrounding your PICO question and rationale for the project. Use the resources below to learn more about how to approach the literature review and best practices.

An Introduction to Literature Reviews

- Article: Literature Review in Encyclopedia of Evaluation A literature review is both process and product. The literature review process entails a systematic examination of prior research, evaluation studies, and scholarship to answer questions of theory, policy, and practice. Read this short article entry from the Encyclopedia of Evaluation to learn about literature reviews and how an integrative review is a specific type.

- eBook Chapter: Literature Review in Nursing Research and Statistics Chapter 5 of Nursing Research and Statistics, detailing the concept of the literature review, its importance, purpose, the different types etc.

- << Previous: Peer Reviewed Sources

- Next: Theoretical Framework >>

JAY SIWEK, M.D., MARGARET L. GOURLAY, M.D., DAVID C. SLAWSON, M.D., AND ALLEN F. SHAUGHNESSY, PHARM.D.

Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(2):251-258

Traditional clinical review articles, also known as updates, differ from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Updates selectively review the medical literature while discussing a topic broadly. Nonquantitative systematic reviews comprehensively examine the medical literature, seeking to identify and synthesize all relevant information to formulate the best approach to diagnosis or treatment. Meta-analyses (quantitative systematic reviews) seek to answer a focused clinical question, using rigorous statistical analysis of pooled research studies. This article presents guidelines for writing an evidence-based clinical review article for American Family Physician . First, the topic should be of common interest and relevance to family practice. Include a table of the continuing medical education objectives of the review. State how the literature search was done and include several sources of evidence-based reviews, such as the Cochrane Collaboration, BMJ's Clinical Evidence , or the InfoRetriever Web site. Where possible, use evidence based on clinical outcomes relating to morbidity, mortality, or quality of life, and studies of primary care populations. In articles submitted to American Family Physician , rate the level of evidence for key recommendations according to the following scale: level A (randomized controlled trial [RCT], meta-analysis); level B (other evidence); level C (consensus/expert opinion). Finally, provide a table of key summary points.

American Family Physician is particularly interested in receiving clinical review articles that follow an evidence-based format. Clinical review articles, also known as updates, differ from systematic reviews and meta-analyses in important ways. 1 Updates selectively review the medical literature while discussing a topic broadly. An example of such a topic is, “The diagnosis and treatment of myocardial ischemia.” Systematic reviews comprehensively examine the medical literature, seeking to identify and synthesize all relevant information to formulate the best approach to diagnosis or treatment. Examples are many of the systematic reviews of the Cochrane Collaboration or BMJ's Clinical Evidence compendium. Meta-analyses are a special type of systematic review. They use quantitative methods to analyze the literature and seek to answer a focused clinical question, using rigorous statistical analysis of pooled research studies. An example is, “Do beta blockers reduce mortality following myocardial infarction?”

The best clinical review articles base the discussion on existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and incorporate all relevant research findings about the management of a given disorder. Such evidence-based updates provide readers with powerful summaries and sound clinical guidance.

In this article, we present guidelines for writing an evidence-based clinical review article, especially one designed for continuing medical education (CME) and incorporating CME objectives into its format. This article may be read as a companion piece to a previous article and accompanying editorial about reading and evaluating clinical review articles. 1 , 2 Some articles may not be appropriate for an evidence-based format because of the nature of the topic, the slant of the article, a lack of sufficient supporting evidence, or other factors. We encourage authors to review the literature and, wherever possible, rate key points of evidence. This process will help emphasize the summary points of the article and strengthen its teaching value.

Topic Selection

Choose a common clinical problem and avoid topics that are rarities or unusual manifestations of disease or that have curiosity value only. Whenever possible, choose common problems for which there is new information about diagnosis or treatment. Emphasize new information that, if valid, should prompt a change in clinical practice, such as the recent evidence that spironolactone therapy improves survival in patients who have severe congestive heart failure. 3 Similarly, new evidence showing that a standard treatment is no longer helpful, but may be harmful, would also be important to report. For example, patching most traumatic corneal abrasions may actually cause more symptoms and delay healing compared with no patching. 4

Searching the Literature

When searching the literature on your topic, please consult several sources of evidence-based reviews ( Table 1 ) . Look for pertinent guidelines on the diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of the disorder being discussed. Incorporate all high-quality recommendations that are relevant to the topic. When reviewing the first draft, look for all key recommendations about diagnosis and, especially, treatment. Try to ensure that all recommendations are based on the highest level of evidence available. If you are not sure about the source or strength of the recommendation, return to the literature, seeking out the basis for the recommendation.

| The AHRQ Web site includes links to the National Guideline Clearinghouse, Evidence Reports from the AHRQ's 12 Evidence-based Practice Centers (EPC), and Preventive Services. The AHCPR released 19 Clinical Practice Guidelines between 1992 and1996 that were not subsequently updated. | ||

| evaluates evidence in individual articles. Commentary by ACP author offers clinical recommendations. Access to the online version of is a benefit for members of the ACP-ASIM, but will be open to all until at least the end of 2001. | ||

| Features short evaluations/discussions of individual articles dealing with evidence-based clinical practice. | ||

| The University of Oxford/Oxford Radcliffe Hospital Clinical School Web site includes links to CEBM within the Faculty of Medicine, a CATbank (Critically Appraised Topics), links to evidence-based journals, and EBM-related teaching materials. | ||

| The AHRQ began the Translating Research into Practice (TRIP) initiative in 1990 to implement evidence-based tools and information. The TRIP Database features hyperlinks to the largest collection of EBM materials on the internet, including NGC, POEM, DARE, Cochrane Library, CATbank, and individual articles. A good starting place for an EBM literature search. | ||

| , | ||

| Searches BMJ's compendium for up-to-date evidence regarding effective health care. Lists available topics and describes the supporting body of evidence to date (e.g., number of relevant randomized controlled trials published to date). Concludes with interventions “likely to be beneficial” versus those with “unknown effectiveness.” Individuals who have received a free copy of Issue 5 from the United Health Foundation are also entitled to free access to the full online content. | ||

| Systematic evidence reviews that are updated periodically by the Cochrane Group. Reviewers discuss whether adequate data are available for the development of EBM guidelines for diagnosis or management. | ||

| Structured abstracts written by University of York CRD reviewers (see NHS CRD). Abstract summaries review articles on diagnostic or treatment interventions and discuss clinical implications. | ||

| Bi-monthly, peer-reviewed bulletin for medical decision-makers. Based on systematic reviews and synthesis of research on the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of health service interventions. | ||

| Bimonthly publication launched in 1995 by the BMJ Publishing Group. Article summaries include commentaries by clinical experts. Subscription is required. | ||

| Newsletter (including Patient-Oriented Evidence that Matters [POEM])* | ||

| This newsletter features up-to-date POEM, Disease-Oriented Evidence (DOE), and tests approved for Category 1 CME credit. Subscription required. | ||

| Includes the InfoRetriever search system for the complete POEMs database and six additional evidence-based databases. Subscription is required. | ||

| ICSI is an independent, nonprofit collaboration of health care organizations, including the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Web site includes the ICSI guidelines for preventive services and disease management. | ||

| Comprehensive database of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines from government agencies and health care organizations. Describes and compares guideline statements with respect to objectives, methods, outcomes, evidence rating scheme, and major recommendations. | ||

| Searches CRD Databases (includes DARE, NHS Economic Evaluation Database, Health Technology Assessment Database) for EBM reviews. More limited than TRIP Database. | ||

| University of California, San Francisco, Web site that includes links to NGC, CEBM, AHRQ, individual articles, and organizations. | ||

| This Web site features updated recommendations for clinical preventive services based on systematic evidence reviews by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. | ||

In particular, try to find the answer in an authoritative compendium of evidence-based reviews, or at least try to find a meta-analysis or well-designed randomized controlled trial (RCT) to support it. If none appears to be available, try to cite an authoritative consensus statement or clinical guideline, such as a National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement or a clinical guideline published by a major medical organization. If no strong evidence exists to support the conventional approach to managing a given clinical situation, point this out in the text, especially for key recommendations. Keep in mind that much of traditional medical practice has not yet undergone rigorous scientific study, and high-quality evidence may not exist to support conventional knowledge or practice.

Patient-Oriented vs. Disease-Oriented Evidence

With regard to types of evidence, Shaughnessy and Slawson 5 – 7 developed the concept of Patient-Oriented Evidence that Matters (POEM), in distinction to Disease-Oriented Evidence (DOE). POEM deals with outcomes of importance to patients, such as changes in morbidity, mortality, or quality of life. DOE deals with surrogate end points, such as changes in laboratory values or other measures of response. Although the results of DOE sometimes parallel the results of POEM, they do not always correspond ( Table 2 ) . 2 When possible, use POEM-type evidence rather than DOE. When DOE is the only guidance available, indicate that key clinical recommendations lack the support of outcomes evidence. Here is an example of how the latter situation might appear in the text: “Although prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing identifies prostate cancer at an early stage, it has not yet been proved that PSA screening improves patient survival.” (Note: PSA testing is an example of DOE, a surrogate marker for the true outcomes of importance—improved survival, decreased morbidity, and improved quality of life.)

| Antiarrhythmic therapy | Antiarrhythmic drug X decreases the incidence of PVCs on ECGs | Antiarrhythmic drug X is associated with an increase in mortality | POEM results are contrary to DOE implications |

| Antihypertensive therapy | Antihypertensive drug treatment lowers blood pressure | Antihypertensive drug treatment is associated with a decrease in mortality | POEM results are in concordance with DOE implications |

| Screening for prostate cancer | PSA screening detects prostate cancer at an early stage | Whether PSA screening reduces mortality from prostate cancer is currently unknown | Although DOE exists, the important POEM is currently unknown |

Evaluating the Literature

Evaluate the strength and validity of the literature that supports the discussion (see the following section, Levels of Evidence). Look for meta-analyses, high-quality, randomized clinical trials with important outcomes (POEM), or well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trials, clinical cohort studies, or case-controlled studies with consistent findings. In some cases, high-quality, historical, uncontrolled studies are appropriate (e.g., the evidence supporting the efficacy of Papanicolaou smear screening). Avoid anecdotal reports or repeating the hearsay of conventional wisdom, which may not stand up to the scrutiny of scientific study (e.g., prescribing prolonged bed rest for low back pain).

Look for studies that describe patient populations that are likely to be seen in primary care rather than subspecialty referral populations. Shaughnessy and Slawson's guide for writers of clinical review articles includes a section on information and validity traps to avoid. 2

Levels of Evidence

Readers need to know the strength of the evidence supporting the key clinical recommendations on diagnosis and treatment. Many different rating systems of varying complexity and clinical relevance are described in the medical literature. Recently, the third U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) emphasized the importance of rating not only the study type (RCT, cohort study, case-control study, etc.), but also the study quality as measured by internal validity and the quality of the entire body of evidence on a topic. 8

While it is important to appreciate these evolving concepts, we find that a simplified grading system is more useful in AFP . We have adopted the following convention, using an ABC rating scale. Criteria for high-quality studies are discussed in several sources. 8 , 9 See the AFP Web site ( www.aafp.org/afp/authors ) for additional information about levels of evidence and see the accompanying editorial in this issue discussing the potential pitfalls and limitations of any rating system.

Level A (randomized controlled trial/meta-analysis): High-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT) that considers all important outcomes. High-quality meta-analysis (quantitative systematic review) using comprehensive search strategies.

Level B (other evidence): A well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial. A nonquantitative systematic review with appropriate search strategies and well-substantiated conclusions. Includes lower quality RCTs, clinical cohort studies, and case-controlled studies with non-biased selection of study participants and consistent findings. Other evidence, such as high-quality, historical, uncontrolled studies, or well-designed epidemiologic studies with compelling findings, is also included.

Level C (consensus/expert opinion): Consensus viewpoint or expert opinion.

Each rating is applied to a single reference in the article, not to the entire body of evidence that exists on a topic. Each label should include the letter rating (A, B, C), followed by the specific type of study for that reference. For example, following a level B rating, include one of these descriptors: (1) nonrandomized clinical trial; (2) nonquantitative systematic review; (3) lower quality RCT; (4) clinical cohort study; (5) case-controlled study; (6) historical uncontrolled study; (7) epidemiologic study.

Here are some examples of the way evidence ratings should appear in the text:

“To improve morbidity and mortality, most patients in congestive heart failure should be treated with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. [Evidence level A, RCT]”

“The USPSTF recommends that clinicians routinely screen asymptomatic pregnant women 25 years and younger for chlamydial infection. [Evidence level B, non-randomized clinical trial]”

“The American Diabetes Association recommends screening for diabetes every three years in all patients at high risk of the disease, including all adults 45 years and older. [Evidence level C, expert opinion]”

When scientifically strong evidence does not exist to support a given clinical recommendation, you can point this out in the following way:

“Physical therapy is traditionally prescribed for the treatment of adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder), although there are no randomized outcomes studies of this approach.”

Format of the Review

Introduction.

The introduction should define the topic and purpose of the review and describe its relevance to family practice. The traditional way of doing this is to discuss the epidemiology of the condition, stating how many people have it at one point in time (prevalence) or what percentage of the population is expected to develop it over a given period of time (incidence). A more engaging way of doing this is to indicate how often a typical family physician is likely to encounter this problem during a week, month, year, or career. Emphasize the key CME objectives of the review and summarize them in a separate table entitled “CME Objectives.”

The methods section should briefly indicate how the literature search was conducted and what major sources of evidence were used. Ideally, indicate what predetermined criteria were used to include or exclude studies (e.g., studies had to be independently rated as being high quality by an established evaluation process, such as the Cochrane Collaboration). Be comprehensive in trying to identify all major relevant research. Critically evaluate the quality of research reviewed. Avoid selective referencing of only information that supports your conclusions. If there is controversy on a topic, address the full scope of the controversy.

The discussion can then follow the typical format of a clinical review article. It should touch on one or more of the following subtopics: etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation (signs and symptoms), diagnostic evaluation (history, physical examination, laboratory evaluation, and diagnostic imaging), differential diagnosis, treatment (goals, medical/surgical therapy, laboratory testing, patient education, and follow-up), prognosis, prevention, and future directions.

The review will be comprehensive and balanced if it acknowledges controversies, unresolved questions, recent developments, other viewpoints, and any apparent conflicts of interest or instances of bias that might affect the strength of the evidence presented. Emphasize an evidence-supported approach or, where little evidence exists, a consensus viewpoint. In the absence of a consensus viewpoint, you may describe generally accepted practices or discuss one or more reasoned approaches, but acknowledge that solid support for these recommendations is lacking.

In some cases, cost-effectiveness analyses may be important in deciding how to implement health care services, especially preventive services. 10 When relevant, mention high-quality cost-effectiveness analyses to help clarify the costs and health benefits associated with alternative interventions to achieve a given health outcome. Highlight key points about diagnosis and treatment in the discussion and include a summary table of the key take-home points. These points are not necessarily the same as the key recommendations, whose level of evidence is rated, although some of them will be.

Use tables, figures, and illustrations to highlight key points, and present a step-wise, algorithmic approach to diagnosis or treatment when possible.

Rate the evidence for key statements, especially treatment recommendations. We expect that most articles will have at most two to four key statements; some will have none. Rate only those statements that have corresponding references and base the rating on the quality and level of evidence presented in the supporting citations. Use primary sources (original research, RCTs, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews) as the basis for determining the level of evidence. In other words, the supporting citation should be a primary research source of the information, not a secondary source (such as a nonsystematic review article or a textbook) that simply cites the original source. Systematic reviews that analyze multiple RCTs are good sources for determining ratings of evidence.

The references should include the most current and important sources of support for key statements (i.e., studies referred to, new information, controversial material, specific quantitative data, and information that would not usually be found in most general reference textbooks). Generally, these references will be key evidence-based recommendations, meta-analyses, or landmark articles. Although some journals publish exhaustive lists of reference citations, AFP prefers to include a succinct list of key references. (We will make more extensive reference lists available on our Web site or provide links to your personal reference list.)

You may use the following checklist to ensure the completeness of your evidence-based review article; use the source list of reviews to identify important sources of evidence-based medicine materials.

Checklist for an Evidence-Based Clinical Review Article

The topic is common in family practice, especially topics in which there is new, important information about diagnosis or treatment.

The introduction defines the topic and the purpose of the review, and describes its relevance to family practice.

A table of CME objectives for the review is included.

The review states how you did your literature search and indicates what sources you checked to ensure a comprehensive assessment of relevant studies (e.g., MEDLINE, the Cochrane Collaboration Database, the Center for Research Support, TRIP Database).

Several sources of evidence-based reviews on the topic are evaluated ( Table 1 ) .

Where possible, POEM (dealing with changes in morbidity, mortality, or quality of life) rather than DOE (dealing with mechanistic explanations or surrogate end points, such as changes in laboratory tests) is used to support key clinical recommendations ( Table 2 ) .

Studies of patients likely to be representative of those in primary care practices, rather than subspecialty referral centers, are emphasized.

Studies that are not only statistically significant but also clinically significant are emphasized; e.g., interventions with meaningful changes in absolute risk reduction and low numbers needed to treat. (See http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1116 .) 11

The level of evidence for key clinical recommendations is labeled using the following rating scale: level A (RCT/meta-analysis), level B (other evidence), and level C (consensus/expert opinion).

Acknowledge controversies, recent developments, other viewpoints, and any apparent conflicts of interest or instances of bias that might affect the strength of the evidence presented.

Highlight key points about diagnosis and treatment in the discussion and include a summary table of key take-home points.

Use tables, figures, and illustrations to highlight key points and present a step-wise, algorithmic approach to diagnosis or treatment when possible.

Emphasize evidence-based guidelines and primary research studies, rather than other review articles, unless they are systematic reviews.

The essential elements of this checklist are summarized in Table 3 .

| Choose a common, important topic in family practice. |

| Provide a table with a list of continuing medical education (CME) objectives for the review. |

| State how the literature search and reference selection were done. |

| Use several sources of evidence-based reviews on the topic. |

| Rate the level of evidence for key recommendations in the text. |

| Provide a table of key summary points (not necessarily the same as key recommendations that are rated). |

Siwek J. Reading and evaluating clinical review articles. Am Fam Physician. 1997;55:2064-2069.

Shaughnessy AF, Slawson DC. Getting the most from review articles: a guide for readers and writers. Am Fam Physician. 1997;55:2155-60.

Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709-17.

Flynn CA, D'Amico F, Smith G. Should we patch corneal abrasions? A meta-analysis. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:264-70.

Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF, Bennett JH. Becoming a medical information master: feeling good about not knowing everything. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:505-13.

Shaughnessy AF, Slawson DC, Bennett JH. Becoming an information master: a guidebook to the medical information jungle. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:489-99.

Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. Becoming an information master: using POEMs to change practice with confidence. Patient-oriented evidence that matters. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:63-7.

Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, et al. Methods Work Group, Third U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. A review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 suppl):21-35.

CATbank topics: levels of evidence and grades of recommendations. Retrieved November 2001, from: http://www.cebm.net/ .

Saha S, Hoerger TJ, Pignone MP, Teutsch SM, Helfand M, Mandelblatt JS. for the Cost Work Group of the Third U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The art and science of incorporating cost effectiveness into evidence-based recommendations for clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 suppl):36-43.

Evidence-based medicine glossary. Retrieved November 2001, from: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1116 .

Continue Reading

More in afp, more in pubmed.

Copyright © 2002 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Evidence-Based Practice PT

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Literature Review

- Developing a Topic

- Question Development

- Background questions

- Citation Management

- Critical Appraisal

What is a Literature Review

A literature review is a systematic review of the published literature on a specific topic or research question designed to analyze-- not just summarize-- scholarly writings that are related directly to your research question . That is, it represents the literature that provides background information on your topic and shows a correspondence between those writings and your research question. This guide is designed to be a general resource for those completing a literature review in their field.

Why a Literature Review is Important

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

A Literature Review Must:

A literature review must do these things

- be organized around and related directly to the thesis or research question you are developing

- synthesize results into a summary of what is and is not known

- identify areas of controversy in the literature

- formulate questions that need further research

A Literature Review is NOT

Keep in mind that a literature review defines and sets the stage for your later research. While you may take the same steps in researching your literature review, your literature review is NOT:

- Not an annotated bibliography i n which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A lit review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

- Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

Types of Literature Reviews

D ifferent projects involve different kinds of literature reviews with different kinds and amounts of work. And, of course, the "end products" vary.

- Honors paper

- Capstone project

- Research Study

- Senior thesis

- Masters thesis

- Doctoral dissertation

- Research article

- Grant proposal

- Evidence based practice

- << Previous: Evidence-Based Practice

- Next: Developing a Topic >>

- The Interprofessional Health Sciences Library

- 123 Metro Boulevard

- Nutley, NJ 07110

- [email protected]

- Student Services

- Parents and Families

- Career Center

- Web Accessibility

- Visiting Campus

- Public Safety

- Disability Support Services

- Campus Security Report

- Report a Problem

- Login to LibApps

NUR 3710 Evidence Based Research Guide: Literature Review

- Evidence Based Practice

- Peer- Reviewed Journals

Literature Review

- About Zotero

A literature review is an essay or part of an essay that summarizes and analyzes research in a particular discipline. It assess the literature by reviewing a large body of studies on a given subject matter. It summarizes by pointing out the main findings, linking together the numerous studies and explaining how they fit into the overall academic discussion on that subject. It critically analyzes the literature by pointing out the areas of weakness, expansion, and contention.

Literature Review Sections:

- Introduction: indicates the general state of the literature on a given subject.

- Methodology: states where (databases), how (what subject terms used on searches), and what (parameters of studies that were included); so others may recreate the searches and explain the reasoning behind the selection of those studies.

- Findings: summary of the major findings in that subject.

- Discussion: a general progression from broader studies to more focused studies.

- Conclusion: for each major section that again notes the overall state of the research, albeit with a focus on the major synthesized conclusions, problems in the research, and even possible avenues for further research.

- References: a list of all the studies using proper citation style.

Literature Review Tips:

- Beware of stating your own opinions or personal recommendations (unless you have evidence to support such claims).

- Provide proper references to research studies.

- Focus on research studies to provide evidence and the primary purpose of the literature review.

- Connect research studies with the overall conversation on the subject.

- Have a search strategy planner and log to keep you focused.

Literature reviews are not book reports or commentaries; make sure to stay focused, organized, and free of personal biases or unsubstantiated recommendations.

Literature Review Examples:

- Lemetti, T., Stolt, M., Rickard, N., & Suhonen, R. (2015). Collaboration between hospital and primary care nurses: a literature review. International Nursing Review , 62 (2), 248-266. doi:10.1111/inr.12147

Templates for Starting Your Literature Review

- Literature search strategy planner

- Literature search log template

- Review Literature

Featured Ebook

Literature Review Steps

1. Choose a topic and define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by a focus research question. Consider PICO and FINER criteria for developing a research question.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Do a couple of pre-searches to see what information is out there and determine if it is a manageable topic.

- Identify the main concepts of your research question and write down terms that are related to them. Keep a list of terms that you can use when searching.

- If possible, discuss your topic with your professor.

2. Decide on the scope of your review.

Check with your assignment requirements and your professor for parameters of the Literature Review.

- How many studies are you considering?

- How comprehensive will your literature review be?

- How many years should it cover?

3. Select appropriate databases to search.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

- Don't forget to look at books, dissertations or other specialized databases .

- Contact your librarian to make sure you are not missing any vital databases for that topic.

4. Conduct searches and find relevant literature.

As you are searching in databases is important to keep track and notes as you uncover information.

- Read the abstracts of research studies carefully instead of just downloading articles that have good titles.

- Write down the searches you conduct in each database so that you may duplicate or avoid unsuccessful searches again.

- Look at the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others .

- Look for subject terms or MeSH terms that are associated with the research studies you find and use those terms in more searches.

- Use a citation manager such as Zotero or Endnote Basic to keep track of your research citations.

5. Review the literature.

As you are reading the full articles ask the following questions when assessing studies:

- What is the research question of the study?

- Who are the author(s)? What are their credentials and how are they viewed in their field?

- Has this study been cited?; if so, how has it been analyzed?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions. Does the research seem to be complete? What further questions does it raise?

- Are there any conflicting studies; if so why?

Throughout the process keep careful notes of your searches and findings so it is easier to put it together when it comes to the writing part.

- << Previous: Databases

- Next: Writing >>

- Last Updated: Jul 15, 2024 2:54 PM

- URL: https://hpu.libguides.com/NUR3710

- UWF Libraries

Evidence Based Nursing

- Types of Reviews

- What is Evidence -Based Practice & PICO

- PICO Widgets for Searching

- PubMed - Info & Tutorials

- Cochrane Library - Info & Tutorials

- Joanna Briggs Institute - Tutorial

- Finding the Evidence: Summaries & Clinical Guidlines

- Find Books & Background Resources

- Statistics and Data

- APA Formatting Guide

- Citation Managers

- Library Presentations

What are the types of reviews?

As you begin searching through the literature for evidence, you will come across different types of publications. Below are examples of the most common types and explanations of what they are. Although systematic reviews and meta-analysis are considered the highest quality of evidence, not every topic will have an Systematic Review or Metanalysis.

Use the PRISMA Online Checklist to assess research and systematic reviews

Literature Review Examples

Remember, a literature review provides an overview of a topic. There may or may not be a method for how studies are collected or interpreted. Lit reviews aren't always obviously labeled "literature review"; they may be embedded within sections such as the introduction or background. You can figure this out by reading the article .

- Dance therapy for individuals with Parkinson's Disease Notice how the introduction and subheadings provide background on the topic and describe way it's important. Some studies are grouped together that convey a similar idea. Limitations of some studies are addressed as a way of showing the significance of the research topic.

- Ethical Issues Regarding Human Cloning: A Nursing Perspective Notice how this article is broken into several sections: background on human cloning, harms of cloning, and nursing issues in cloning. These are the themes of the different articles that were used in writing this literature review. Look at how the articles work together to form a cohesive piece of literature.

Systematic Review Examples

Systematic reviews address a clinical question. Reviews are gathered using a specific, defined set of criteria.

- Selection criteria is defined

- The words "Systematic Review" may appear int he title or abstract

- BTW -> Cochrane Reviews aka Systematic Reviews

- Additional reviews can be found by using a systematic review limit

- A Systematic Review of Animal-Assisted Therapy on Psychosocial Outcomes in People with Intellectual Disability

- The determinants and consequences of adult nursing staff turnover: a systematic review of systematic reviews

- Cochrane Library (Wiley) This link opens in a new window Over 5000 reviews of research on medical treatments, practices, and diagnostic tests are provided in this database. Cochrane Reviews is the premier resource for Evidence Based Practice.

- PubMed (NLM) This link opens in a new window PubMed comprises more than 22 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books.

Meta-Analysis Examples

Meta-analysis is a study that combines data from OTHER studies. All the studies are combined to argue whether a clinical intervention is statistically significant by combining the results from the other studies. For example, you want to examine a specific headache intervention without running a clinical trial. You can look at other articles that discuss your clinical intervention, combine all the participants from those articles, and run a statistical analysis to test if your results are significant. Guess what? There's a lot of math.

- Include the words "meta-analysis" or "meta analysis" in your keywords

- Meta-analyses will always be accompanied by a systematic review, but a systematic review may not have a meta-analysis

- See if the abstract or results section mention a meta-analysis

- Use databases like Cochrane or PubMed

- Exercise Interventions for Preventing Falls Among Older People in Care Facilities: A Meta-Analysis

- Acupuncture for the prevention of tension-type headache This is a systematic review that includes a meta-analysis. Check out the Abstract and Results for an example of what a meta-analysis looks like!

- << Previous: What is Evidence -Based Practice & PICO

- Next: Finding the Evidence >>

- Last Updated: May 28, 2024 1:18 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uwf.edu/EBN

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Systematic reviews: the heart of evidence-based practice

Affiliation.

- 1 Academic Center for Evidence-Based Nursing, University of Texas, Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive MC 7951, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 11759425

- DOI: 10.1097/00044067-200111000-00009

Research utilization approaches in nursing recently have been replaced by evidence-based practice (EBP) approaches. The heart of the new EBP paradigm is the systematic review. Systematic reviews are carefully synthesized research evidence designed to answer focused clinical questions. Systematic reviews (also known as evidence summaries and integrative reviews) implement recently developed scientific methods to summarize results from multiple research studies. Specific strategies are required for success in locating systematic reviews. Major sources of systematic reviews for use by advanced practice nurses in acute and critical care are the Online Journal of Knowledge Synthesis for Nursing, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Cochrane Library. This discussion describes systematic reviews as the pivotal point in today's paradigm of EBP and guides the advanced practice nurse in locating and accessing systematic reviews for use in practice.

PubMed Disclaimer

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Wolters Kluwer

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Social Work 795: Evaluation of Social Work Practice and Programs

- What is Evidence-Based Practice?

- Create a search strategy

- Find Evidence-Based Interventions

- Research methods

- Cite sources in APA

- Citation Managers

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP)

NASW states that social work EBP is "a process involving creating an answerable question based on a client or organizational need, locating the best available evidence to answer the question, evaluating the quality of the evidence as well as its applicability, applying the evidence, and evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of the solution."

Read more from NASW about EBP in Social Work

EBP Tutorial Duke University Medical Center Library

Learn more about evidence synthesis reviews

Levels of Evidence

- The Pyramid

- Non-Research Information

Observational Studies

Experimental studies.

- Critical Analysis

Levels of evidence

The levels of evidence pyramid demonstrates a hierarchy of information sources based on the strength of the evidence reported. Click through the tabs to learn more about the each of the levels and the strength of the evidence and example research articles for different study types.

Non-Evidence-based sources

While these information sources do not meet the criteria for evidence, this kind of information can help you to get background information or context on a particular topic area, are typically easier to understand, and may include references to evidence-based research.

- Non-Evidence-based Expert Opinions : These can include commentary statements, speeches, or editorials written by prominent experts asserting ideas that are reached by conjecture, casual observation, emotion, religious belief, or ego

- Non-EBP guidelines : Practice guidelines that exist because of eminence, authority, eloquence, providence, or diffidence based approaches to healthcare

- News Articles : News articles are written by journalists for the general public and may report on or summarize research studies and outcomes

- Editorials : Opinions written by experts, non-experts, or regular folks that are published by news outlets, magazines, or academic journals

- Commentary : similar to an editorial, but it may be identified as a commentary, which can be an invited informal and non-reviewed short article pertaining to a particular concept or idea.

- Narrative literature review articles : Non-systematic and non-exhaustive survey of the literature on a specific topic. However, evidence synthesis review articles are considered to be a high degree of evidence by nature of their methodology (see critical appraisal tab).

Let's Talk about Review Articles

Review articles are common in health literature. They are typically overviews of literature found on topics, but do not go so far as to meet the methodological requirements for a Systematic Review.

These articles may contain some critical analysis, but will not have the rigorous criteria that a Systematic Review does. They can be used to demonstrate evidence, albeit they do not make a very strong case as they are secondary articles and not originally conducted observational or experimental research.

These types of publications have the lowest evidence strength in the hierarchy. The evidence is largely anecdotal since they often lack a systematic methodology, have limited statistical sampling, even if the studies are in some instances empirical and verifiable. Examples of observational studies are:

- example: Thoele, K., Ferren, M., Moffat, L. et al. (2020). Development and use of a toolkit to facilitate implementation of an evidence-based intervention: a descriptive case study. Implement Sci Commun, 1(86). DOI: 10.1186/s43058-020-00081-x

- example: Tone, J., Chelius, B. & Miller, Y.D. (2022). The effectiveness of a feminist-informed, individualised counselling intervention for the treatment of eating disorders: a case series study. J Eat Disord , 10(70). DOI: 10.1186/s40337-022-00592-z

- Choi, S., Bunting, A., Nadel, T., Neighbors, C. J., & Oser, C. B. (2023). Organizational access points and substance use disorder treatment utilization among Black women: a longitudinal cohort study. Health & Justice , 11 (1), 1–12. DOI: 10.1186/s40352-023-00236-7

- Example: Belenko, S., Dennis, M., Hiller, M., Mackin, J., Cain, C., Weiland, D., Estrada, B., & Kagan, R. (2022). The impact of juvenile drug treatment courts on substance use, mental health, and recidivism: Results from a multisite experimental evaluation. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 49 (4), 436-455. DOI: 10.1007/s11414-022-09805-4

- Example: Putnam-Hornstein, E., Prindle, J., & Hammond, I. (2021). Engaging Families in Voluntary Prevention Services to Reduce Future Child Abuse and Neglect: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Prevention Science , 22 (7), 856–865. DOI: 10.1007/s11121-021-01285-w

Critical Appraisal

"Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, and its value and relevance in a particular context." Burls, A. (2009). What is critical appraisal? In What Is This Series: Evidence-based medicine. Available online at What is Critical Appraisal?

Examples of Critical Appraisal

Evidence synthesis reviews are types of critical appraisal. Examples of evidence synthesis reviews are scoping reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis. To find these types of articles, search for "systematic review", "scoping review", or meta-analysis in the title. Learn more about conducting evidence synthesis reviews .

- Example: Kokorelias, K. M., PhD., Shiers-Hanley, J., Li, Z., & Hitzig, S. L., PhD. (2023/10//). A Systematic Review on Navigation Programs for Persons Living With Dementia and Their Caregivers. The Gerontologist, 63 (8), 1341. DOI: 10.1093/geront/gnac054

Example: Hans, B. B., Drozd, F., Olafsen, K., Nilsen, K. H., Linnerud, S., Kjøbli, J., & Jacobsen, H. (2023/08//). The effect of relationship-based interventions for maltreated children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 35 (3), 1251-1271. doi: 10.1017/S0954579421001164

- Example: After thorough testing and experimentation, researchers, doctors, and product developers created and started using less-invasive oxygen monitoring devices to improve recovery times after surgeries. These are now standard equipment.

Tips for identifying empirically based research

Characteristics to look for:

States the problem, population, or research question under study

Defines the group or issue being studied

Study methodology is reported

Alternative interventions may be included or compared

May be quantitative or qualitative [check with your course instructor or syllabus, as the course focus may be on just one or the other]

May include tests or surveys (embedded, as an appendix, or referred to by proper name)

May be reproducible; to be replicated or adapted to a new study

Tips for searching for empirically based research

Search for peer-reviewed journal articles that report research findings in one of the recommended databases. Some databases have a filter or advanced search limiter focus results on empirical research, for example filters for systematic reviews or randomized control trials . If a filter/limiter is not available, enter keywords to match on appropriate content and/or to look for these terms in the abstract or article itself:

- methods or methodology

- quantitative

- statistic* ( the asterisk is used as a "wildcard" ending to your search term which allows the database to match on statistic, statistics or statistical)

- [inclusion of] charts, statistical tables or graphs

- << Previous: Welcome

- Next: Create a search strategy >>

- Last Updated: Jul 16, 2024 3:13 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.uwm.edu/SW795

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Literature-based discovery approaches for evidence-based healthcare: a systematic review

Sudha cheerkoot-jalim.

1 Department of Information and Communication Technologies, University of Mauritius, Reduit, Mauritius

Kavi Kumar Khedo

2 Department of Digital Technologies, University of Mauritius, Reduit, Mauritius

Associated Data

Not applicable.

Not applicable

Literature-Based Discovery (LBD) is a text mining technique used to generate novel hypotheses from vast amounts of literature sources, by identifying links between concepts from disparate sources. One of the main areas where it has been predominantly applied is the healthcare domain, whereby promising results, in the form of novel hypotheses, have been reported. The purpose of this work was to conduct a systematic literature review of recent publications on LBD in the healthcare domain in order to assess the trends in the approaches used and to identify issues and challenges for such systems.

The review was conducted following the principles of the Kitchenham method. The selected studies have been scrutinized and the derived findings have been reported following the PRISMA guidelines.

The review results reveal useful information regarding the application areas, the data sources considered, the approaches used, the performance in terms of accuracy and reliability and future research challenges. The results of this review will be beneficial to LBD researchers and other stakeholders in the healthcare domain, by providing them with useful insights on the approaches to adopt, data sources to consider, evaluation model to use and challenges to reflect on.

The synthesis of the results of this work has shed light on recent issues and challenges that drive new LBD models and provides avenues for their application in other diverse areas in the healthcare domain. To the best of our knowledge, no such recent review has been conducted.

Introduction

Healthcare management, being one of the highest priorities of most governments, attracts huge investments in terms of health and medical research worldwide. Medical research was found to be the main contributing factor in the improvement of health and longevity of individuals and populations in developed countries [ 1 ]. Researchers in the field are making new discoveries and generating knowledge, which has the potential to enhance healthcare delivery, improve patient health outcomes and reduce healthcare costs, thus strengthening the overall healthcare system and economy. This is only achievable if the knowledge is actually put into action [ 2 ]. However, the transfer of research findings into healthcare practice in the clinical setting, known as knowledge translation [ 3 ], is a very complex and slow process, often resulting in patients not being provided with the most appropriate care, although better treatment recommendations have been proposed and demonstrated. A frequently stated average time lag for knowledge translation is 17 years [ 4 ]. Understanding the various stages of knowledge translation and speeding up the process is a policy priority for many health research systems [ 4 ].

In order to leverage new medical research findings more quickly for the benefit of patients, medical practitioners are encouraged to adopt the practice of evidence-based medicine, whereby medical practitioners are expected to scrutinize the scientific and clinical research literature in their respective areas in an attempt to translate health research knowledge into effective healthcare action more quickly. However, due to the large volumes of biomedical literature available and the time constraints of medical practitioners, the practice of evidence-based medicine has become a major challenge [ 5 ]. This limitation can be considerably overcome by the use of appropriate computation techniques for the automated or semi-automated knowledge extraction from relevant research literature. A broad term commonly used for such techniques is literature based discovery (LBD), whose main goal is to generate novel hypotheses from the vast available biomedical literature by discovering unknown associations in existing knowledge [ 6 ]. Recent advances in machine learning, text mining and statistical analysis techniques have spurred research in this field and have resulted in many publications on the design and application of LBD systems for various use cases in the biomedical and healthcare domains.

The purpose of this work is to perform a systematic literature review of recently published research papers on the application of LBD for evidence-based healthcare, with the objective of identifying and integrating the findings of the most relevant individual studies. It is expected that the results of this review will give insights on the different LBD approaches and tools used in various application areas in the healthcare domain. It will help establish to what extent research has progressed in the field, with a focus on performance criteria like effectiveness, accuracy and reliability. A main outcome would be to identify research challenges, which will invoke further studies and thus, provide avenues for future research in other areas in the healthcare domain. The Kitchenham guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews [ 7 ] was adopted and the reporting of this paper follows PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis) guidelines [ 8 ]. To the best of our knowledge, no such recent review has been performed for evidence-based healthcare.

Evidence-based healthcare

The challenges of knowledge translation have become a major concern to individuals who seek and need healthcare, healthcare providers, policy makers and funders of health services. The incorporation of scientific medical discoveries into practice guidelines and policies in the clinical setting can greatly improve healthcare delivery and patient health outcomes, and is the basis of evidence-based healthcare [ 9 ]. Evidence-based practice involves clinical decision making which considers the best and most up-to-date available scientific evidence, together with patient values and preferences, the clinical judgment of the medical practitioner and the context in which the care is provided [ 10 ]. Healthcare professionals seek evidence to support and justify any activity or intervention for patient care.

Literature based discovery in healthcare

In their practice of evidence-based medicine, medical practitioners are expected to scrutinize the best available evidence for making decisions about the care of individual patients. However, with the increasing volume of academic research papers and related structured knowledge resulting from medical research worldwide, they only focus on publications that are directly relevant to their respective area of specialization and often skip other potentially relevant research. Thus, discoveries in one field remain unknown to others and potential connections between sub-fields are often missed out [ 11 ]. This limitation can be greatly curbed by LBD, which can automate or semi-automate the analysis of online resources from disparate sources to find new discoveries. With the exponential growth of scientific literature, LBD is becoming an increasingly important tool for facilitating research [ 12 ].

LBD generates discoveries not yet published anywhere, by combining knowledge extracted from varied literature sources and therefore, supports hypothesis generation [ 13 ]. There are two modes of discovery in LBD, namely open discovery and closed discovery. Open discovery starts with a concept X and tries to generate a potential association between X and another concept Z, based on an intermediate concept Y. This follows from the ABC co-occurrence model, which states that if A and B are often associated to each other, and B and C are also often associated to each other, there may potentially be an association between A and C, even if this association is not mentioned in any research paper [ 14 ]. In contrast, in closed discovery, both the start concept X and end concept Z are known, and an association between X and Z is predicted, based on a hypothesis about the relationship between X and Z. This technique then attempts to demonstrate the hypothesis through an intermediate concept Y.

LBD approaches in healthcare are becoming essential, since biomedical knowledge is spread out across a larger number of publications [ 15 ]. Potential discoveries in healthcare can be associations that exist between biomedical concepts, which are not usually discussed together in the literature. Appropriate implementation of LBD techniques have the potential to predict future strong associations between these concepts [ 15 ] and therefore entails further research. In the LBD approach the starting concept X may be a disease and the end concept Z may be a treatment or cause for the disease. The results of such discoveries need to be further investigated through experimental methods or clinical studies.

Materials and methods

This review has been performed following the guidelines on undertaking systematic literature reviews by Kitchenham and Charters [ 7 ] and the reporting follows the PRISMA guidelines [ 8 ]. The methodology consisted of first setting out the research questions to give a focus for this review, followed by the specification of the search strategy, the application of assessment criteria for the selection of papers and finally the data analysis and extraction.

Research questions

Based on the objectives of this review, the research questions have been set out and elaborated as follows:

RQ1: What are the main application areas of literature based discovery in evidence-based healthcare?

We seek to find out the different application areas in which the application of LBD techniques has proved to be successful in the healthcare domain.

RQ2: Which important/impactful literature sources are considered by researchers/practitioners for literature based discovery?

The foundation of LBD is the large amount of scientific literature available for a specific field of study. It is therefore important to identify the different literature sources which have been harnessed for LBD in the different studies.

RQ3: Which specific literature based discovery approaches and tools have proven to be effective in the healthcare domain?

Due to the peculiarity of the healthcare domain, LBD techniques have to be adapted to specific application areas. There is therefore the need to investigate the specific LBD techniques/approaches which are more relevant and effective for the healthcare domain.

RQ4: How do literature based discovery systems in the healthcare domain perform in terms of accuracy and reliability?

Accuracy and reliability are imperative evaluation criteria for any computational technique in the healthcare domain, since a wrong intervention can lead to harmful consequences for the patient. We therefore study the different evaluation strategies used for LBD systems and find out their performance in terms of accuracy and reliability.

Search strategy and study selection

The search strategy involved the identification of potential research papers to be included in the review by performing a search on Google Scholar, with keywords ‘“Literature-based discovery” in health’. Google Scholar was chosen since it indexes scientific articles from various scholarly publishers and professional societies like Springer, ScienceDirect, ACM, IEEE Xplore, ResearchGate amongst others [ 16 ]. It also indexes biomedical-specific journals like the Journal of Biomedical Informatics, PLOS ONE and BioMed Central (BMC). Gusenbauer [ 17 ] performed a comparative study of academic search engines in 2019 and concluded that “Google Scholar is currently the most comprehensive academic search engine”. Keyword search was then followed by a manual screening of reference lists of relevant primary studies to extend the search space.

Eligibility criteria

Based on the objectives of this systematic review, we have set some inclusion and exclusion criteria to guide the study selection process, as follows. The focus of this review being on recent advances in LBD techniques and approaches, we considered studies carried out during the last five years, that is, since 2015. We only considered peer-reviewed papers published in the English language. Primary studies were included while secondary and tertiary studies, like surveys, systematic reviews and meta analyses were excluded. During an initial screening of studies, we came across papers which describe general LBD techniques without showing their application in the healthcare domain. Such studies were not included, since the objective of this review was to get insights on the different approaches which are more appropriate for specific application areas of LBD. We thus considered papers which describe the use of LBD approaches in a specific application area in the healthcare domain.

The database search was performed on 2 nd February 2021. The keyword search returned 650 results, after applying the filter on year of publication. The manual screening of reference lists of relevant studies returned 12 eligible studies. 8 duplicate studies were identified from the two sources, resulting in 654 studies to screen. After a rigorous screening of the titles and abstracts based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 29 studies were pre-selected for the review.

Quality assessment

After initial screening based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the pre-selected studies were assessed for “quality” in order to integrate more detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria. Based on the research questions, four quality assessment criteria were set as shown in Table Table1. 1 . The possible outcomes for each criteria were “Yes” if the paper met the criteria and “No” if it did not meet the criteria. Two of the quality assessment criteria also had a “Partially” outcome.

Quality Assessment Criteria

| No | Quality Criteria | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| QC1 | Has the LBD approach used been described in detail? | Yes: The LBD approach used has been described in detail Partially: The LBD approach used has been briefly described No: The LBD approach used has not been described |

| QC2 | Was there a discovery following the research work? | Yes: There was a discovery No: No discovery was made |