The Nazi rise to power

Courtesy of The Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

In the nine years between 1924 and 1933 the Nazi Party transformed from a small, violent, revolutionary party to the largest elected party in the Reichstag.

This topic will explain how Hitler and the Nazi Party rose to power.

Reorganisation and the Bamberg Conference

Whilst Hitler was in prison following the Munich Putsch in 1923, Alfred Rosenberg took over as temporary leader of the Nazi Party. Rosenberg was an ineffective leader and the party became divided over key issues.

The failure of the Munich Putsch had shown Hitler that he would not be able to take power by force. Hitler therefore decided to change tactic and instead focus on winning support for his party democratically and being elected into power.

Following his release from prison on the 20 December 1924, Hitler convinced the Chancellor of Bavaria to remove the ban on the Nazi Party.

In February 1926, Hitler organised the Bamberg Conference. Hitler wanted to reunify the party, and set out a plan for the next few years. Whilst some small differences remained, Hitler was largely successful in reuniting the socialist and nationalist sides of the party.

In the same year, Hitler restructured the Nazi Party to make it more efficient.

Firstly, the Nazi Party adopted a new framework, which divided Germany into regions called Gaue . Each Gaue had its own leader, a Gauleiter. Each Gaue was then divided into subsections, called Kreise . Each Kreise then had its own leader, called a Kreisleiter. Each Kreise was then divided into even smaller sections, each with its own leader, and so on. Each of these sections were responsible to the section above them, with Hitler at the very top of the party with ultimate authority.

The Nazis also established new groups for different professions, from children, to doctors, to lawyers. These aimed to infiltrate already existing social structures, and help the party gain more members and supporters.

These political changes changed the Nazi Party from a paramilitary organisation focused on overthrowing the republic by force, to one focused on gaining power through elections and popular support.

The role of the SA and the SS

The Nazi Party’s paramilitary organisation were the Sturm Abeilung , more commonly known as the SA. The SA were formed in 1921 and were known as ‘brownshirts’ due to their brown uniform. Initially most members were ex-soldiers or unemployed men. Violent and often disorderly, the SA were primarily responsible for the protection of leading Nazis and disrupting other political opponents’ meetings, although they often had a free rein on their activities.

If Hitler was to gain power democratically, he needed to reform the SA. He set out to change their reputation. A new leader, Franz von Salomon, was recruited. Rather than the violent free rein they had previously enjoyed, Salomon was stricter and gave the SA a more defined role.

In 1925, Hitler also established the Schutzstaffel , otherwise known as the SS. The SS were initially created as Hitler’s personal bodyguards, although they would go on to police the entire Third Reich.

The SS were a small sub-division of the SA with approximately 300 members until 1929. In 1929, Heinrich Himmler took over the organisation, and expanded it dramatically.

By 1933, the SS had 35,000 members. Members of the SS were chosen based on their ‘racial purity’, blind obedience and fanatical loyalty to Hitler.

The SS saw themselves as the ultimate defenders of the ‘Aryan’ race and Nazi ideology. They terrorized and aimed to destroy any person or group that threatened this.

The SA and the SS became symbols of terror. The Nazi Party used these two forces to terrify their opposition into subordination, slowly eliminate them entirely, or scare people into supporting them.

Propaganda and the Nazi rise to power

Whilst the SA and the SS played their part, the Nazis primarily focused on increasing their membership through advertising the party legitimately. They did this through simple and effective propaganda .

The Nazis started advocating clear messages tailored to a broad range of people and their problems. The propaganda aimed to exploit people’s fear of uncertainty and instability. These messages varied from ‘Bread and Work’, aimed at the working class and the fear of unemployment, to a ‘Mother and Child’ poster portraying the Nazi ideals regarding woman. Jews and Communists also featured heavily in the Nazi propaganda as enemies of the German people.

Joseph Goebbels was key to the Nazis use of propaganda to increase their appeal. Goebbels joined the Nazi Party in 1924 and became the Gauleiter for Berlin in 1926. Goebbels used a combination of modern media, such as films and radio, and traditional campaigning tools such as posters and newspapers to reach as many people as possible. It was through this technique that he began to build an image of Hitler as a strong, stable leader that Germany needed to become a great power again.

This image of Hitler became known as ‘The Hitler Myth’. Goebbels success eventually led to him being appointed Reich Minister of Propaganda in 1933.

The role of economic instability in the Nazi rise to power

Whilst the Nazis’ own actions, such as the party restructure and propaganda, certainly played a role in their rise to power, the economic and political failure of the Weimar Republic was also a key factor.

Germany’s economy suffered badly after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 .

Germany was particularly badly affected by the Wall Street Crash because of its dependence on American loans from 1924 onwards. As the loans were recalled, the economy in Germany sunk into a deep depression. Investment in business was reduced.

As a result, wages fell by 39% from 1929 to 1932. People in full time employment fell from twenty million in 1929, to just over eleven million in 1933. In the same period, over 10,000 businesses closed every year. As a result of this, the amount of people in poverty increased sharply.

The Depression associated economic failure and a decline in living standards with the Weimar democracy. When combined with the resulting political instability, it left people feeling disillusioned with the Weimar Republic’s democracy and looking for change.

This enhanced the attractiveness of the Nazis propaganda messages.

Reparations suspended

By 1932, Germany had reached breaking point. The economic crisis, which in turn had led to widespread social and political unrest in Germany, meant that it could no longer afford to pay reparations . At the Lausanne Conference held in Switzerland, from the 16 June 1932 to the 9 July 1932, the Allies conceded and indefinitely suspended Germany’s reparation payments.

This concession helped to give the economy a small boost in confidence. Under Brüning and later von Papen and, briefly, von Schleicher , there was an increase in state intervention in the economy. One example of this was the work creation schemes which began in the summer of 1932. These work creation schemes would later be expanded and reinvested in by the Nazis to combat unemployment.

These small signs started to hint at a positive climb in the economy.

These small improvements, only truly evident with the benefit of hindsight , were still at the time completely overshadowed by the poverty and widespread discontent about the general economic situation.

It was into this bleak situation that the Nazis were elected into power.

The role of political instability in the Nazi rise to power

The political instability in the late 1920s and early 1930s played an important role in helping the Nazis rise to power.

This topic will explain how the political situation escalated from the hope of the ‘Grand Coalition’ in 1928, to the dismissal of von Schleicher and the end of the Weimar Republic in 1933.

The ‘Grand Coalition’

In June 1928, Hermann Müller had created the ‘grand coalition’ to rule Germany. This coalition was made up of the SPD, DDP, DVP and the Centre Party: parties from the left and right. Müller had a secure majority of 301 seats out of a total of 491. Political parties seemed to be putting aside their differences and coming together for the good of Germany.

But this was not how it worked out. The parties could not agree on key policies and Müller struggled to get support for legislation.

As the aftermath of the Wall Street Crash hit Germany and unemployment spiralled, the government struggled to balance its budget. On top of its usual payments, the amount of people claiming unemployment benefits was increasing. As the government struggled to agree on the future of unemployment benefits, Müller asked Hindenburg for the use of Article 48 to try and restore stability.

President Hindenburg was a right-wing conservative politician and therefore disliked having the left-wing SPD in power. He refused Müller‘s request. Müller resigned on the 27 March 1930.

Br üning’s government

Müller’s successor was Heinrich Brüning. Although he did not have a majority of seats in the Reichstag, Brüning was well-respected by Hindenburg. Brüning increasingly relied upon, and was granted, use of Article 48 . This set a precedent of governing by presidential decree and moved the Republic away from parliamentary democracy.

As the economic crisis worsened in 1931, Brüning struggled to rule effectively. Extremism became more popular as people desperately sought a solution.

After a disagreement over provisions for the unemployed in 1932, Hindenburg demanded Brüning’s resignation.

Von Papen and von Schleicher

A new election was called, and von Papen replaced Brüning.

Von Papen agreed with the conservative elite that Germany needed an authoritarian leader to stabilise the country. He called for another election in November 1932, hoping to strengthen the frontier against communism and socialism.

Whilst the left-wing and socialist SPD did lose votes, so did the right-wing Nazi Party. The Communist Party gained votes, winning eleven more seats in the Reichstag. Once again, no one party had a majority. The election was a failure.

Following von Papen’s failure, Hitler was offered the chancellorship, but without the right to rule by presidential decree. He refused, and von Schleicher became chancellor.

However, without a majority of his own in the Reichstag, von Schleicher faced the same problems as von Papen. Hindenburg refused to grant von Schleicher permission to rule by decree.

Von Schleicher lasted just one month.

The role of the conservative elite in the Nazi rise to power

The conservative elite were the old ruling class and new business class in Weimar Germany. Throughout the 1920s they became increasingly frustrated with the Weimar Republic’s continuing economic and political instability, their lack of real power and the rise of communism. They believed that a return to authoritarian rule was the only stable future for Germany which would protect their power and money.

The first move towards this desired authoritarian rule was Hindenburg’s increasing use of Article 48 . Between 1925-1931 Article 48 was used a total of 16 times. In 1931 alone this rose to 42 uses, in comparison to only 35 Reichstag laws being passed in the same year. In 1932, Article 48 was used 58 times.

The conservative elite’s second move towards authoritarian rule was helping the Nazi Party to gain power. The conservative elite and the Nazi Party had a common enemy – the political left .

As Hitler controlled the masses support for the political right, the conservative elite believed that they could use Hitler and his popular support to ‘democratically’ take power. Once in power, Hitler could destroy the political left. Destroying the political left would help to remove the majority of political opponents to the ring-wing conservative elite.

Once Hitler had removed the left-wing socialist opposition and destroyed the Weimar Republic, the conservative elite thought they would be able to replace Hitler, and appoint a leader of their choice.

As Hitler’s votes dwindled in the November 1932 elections, the conservative elite knew that if they wanted to use Hitler and the Nazis to destroy the political left, they had to act quickly to get Hitler appointed as chancellor.

Von Papen and Oskar von Hindenburg (President Hindenburg’s son) met secretly and backed Hitler to become chancellor. A group of important industrialists, including Hjalmar Schacht and Gustav Krupp, also wrote outlining their support of Hitler to President Hindenburg.

The support of these figures was vital in Hindenburg’s decision to appoint Hitler as chancellor. Once elected, the conservative elite soon realised that they had miscalculated Hitler and his intentions.

Electoral success

Despite the party restructure, the reorganisation of the SA and the initial development of their propaganda under Goebbels, the Nazi Party gained very little in the 1928 elections. They won just 2.6% of the vote, gaining them 12 seats in the Reichstag.

The following year however, the Wall Street Crash and the resulting economic and political instability swung the conservative elite and electorate in their favour. Goebbels carefully tailored propaganda slowly became considerably more attractive.

In 1930, the Nazis attracted eight times more votes than in 1928. They managed to secure 18.3% of the vote, and 107 seats in the Reichstag. The continuing failure of the government to stabilise the situation only increased the Nazis popularity.

In February 1932, Hitler ran against Hindenburg to become president. Goebbel’s propaganda campaign presented Hitler as a new, dynamic and modern leader for Germany. To emphasise this point, Hitler flew from venue to venue via aeroplane. Hitler lost the election, with 36.8% of the vote to Hindenburg’s 53%. Despite losing, people now viewed Hitler as a credible politician.

Following another Reichstag election in July 1932, the Nazis became the largest party with 230 seats and 37.3% of the vote.

Hitler becomes chancellor

Hitler was not immediately appointed chancellor after the success of the July 1932 elections, despite being leader of the largest party in the Reichstag.

It took the economic and political instability (with two more chancellors failing to stabilise the situation) to worsen, and the support of the conservative elite , to convince Hindenburg to appoint Hitler.

Hitler was sworn in as the chancellor of Germany on the 30 January 1933. The Nazis were now in power.

Continue to next topic

What happened in August

On 2 August 1934, President von Hindenberg died.

On 19 August 1934, Hitler abolished the office of president and declared himself Führer of the German Reich and People.

On 1 August 1936, the Olmypic Games, hosted by Nazi Germany, began in Berlin.

On 17 August 1938, a law was passed forcing Jews who had ‘non-Jewish’ first names to adopt the middle name ‘Israel’ or ‘Sara’.

On 24 August 1941, Hitler publicly ordered the end of the T4 programme to murder disabled people. It still continued in secret.

Propaganda and Hoaxes in Nazi Germany: 80 Years Later

The psychological tactics used to make us believe the most outrageous ideas..

Posted November 8, 2018 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- What Is Fear?

- Take our Generalized Anxiety Disorder Test

- Find a therapist to combat fear and anxiety

When we look back at historical atrocities like the transatlantic slave trade and the Holocaust, we keep wondering how ordinary people with moral sentiments akin to ours could have let them happen.

We want to know, not just because we are completely flabbergasted by the enormities of terror, but also because we know that you and I could easily have been, or become, the not-so-innocent onlookers and even the active executioners.

Even if we accept that pure contempt, if intense enough, can make cruel exploitation seem justified to us, and that hatred, if intense enough, can make retribution and elimination seem justified to us, the question arises how a political group can make almost any ordinary person regard others with contempt or hate of this magnitude.

One answer to this question is that propaganda works in just this way, that is, propaganda is a tool strategically employed to make us believe the most outrageous ideas without us ever questioning their truth. How propaganda further extreme emotions and their corresponding attitudes is the topic of Yale philosophy professor Jason Stanley’s aptly entitled book How Propaganda Works .

Stanley is primarily concerned with what he calls “undermining propaganda” (p. 51). Undermining propaganda, he says, appeals to an ideal in the service of a goal that in fact contradicts this very ideal, for example, appealing to the value of peace to justify war or the value of liberty to justify slavery. This is contrasted with supportive propaganda, which appeals to emotion to strengthen an ideal (or cultural value) for the purposes of justifying a goal, for example, appealing to the horror and (hence) injustice of (real or imagined) atrocities committed by the enemy to justify war.

As a kind of speech, propaganda fundamentally involves political, economic or aesthetic ideals mobilized for a political purpose. Part of its effectiveness, Stanley argues, lies is its design that can make it appear to be harmlessly aiming at conveying an “innocent” at-issue content, when its true message is a derogatory not-at-issue content. For example, if you aim at mobilizing support for stricter immigration laws, referring to non-citizen immigrants as “aliens” can seem harmless, as “alien” is a legal term with just that meaning, but “alien” evokes images of an unwelcome, strange, hostile, humanoid-like creature. This is the not-at-issue content, which can propagandize, for example, by prompting us to regard stricter immigration laws as just.

Stanley provides an insightful and long-needed philosophical analysis of propaganda. However, his narrow focus on "undermining propaganda" makes it less suitable for accommodating the role such emotions as contempt, hate and pride play in mobilizing support for extremist ideologies and “solutions.”

To fill this gap, I will propose a complementary account of how propaganda elicits emotions and show how these emotions cause ordinary individuals to regard extremist ideologies and “solutions” as just and necessary.

Since my proposal will address propaganda that simultaneously undermine and support, I will treat Stanley’s distinction between supporting and undermining propaganda as a distinction implicitly referring to distinct mechanisms that can be at work in one and the same piece of propaganda.

On my view, the main function of propaganda is to elicit strong emotions in a group of people in order to create a cohesive group organized around common values and implicitly or explicitly define who are excluded from group membership in order to mobilize the forces of group polarization.

Rhetoric and pictures can induce emotions in a number of different ways. One is by containing slur-like phrases (for instance, phrases with negative connotations such as “welfare,” “alien,” “rat,” or “sexually promiscuous”) that indirectly degrade the perceived enemy but are less likely than explicit slurs to register with us as offensive, Stanley suggests.

Degrading language and pictures, including the use of slurs and animalistic depictions, especially in older form of propaganda, will tend to induce contempt but not hatred. In the colonial era, “cockroaches,” “orangutans,” “apes,” “monkeys,” “primates,” “beasts,” “bluegums,” “stenchers,” “drudges,” “she-devils,” (defiant black women) “six-legged-s,” (black women with sagging breasts) “mules,” (children of a white man and a black slave) and “uppity beasts” (“misbehaving” slaves) were part of the rhetoric that kept the colonists’ contemptuous attitudes toward blacks alive.

After Hitler came to power in 1933, expressions like “lives unworthy of life,” “useless eaters,” “unjust burdens,” “misfits,” “freaks,” and “monsters” were part of the rhetoric that made Germans hold contempt for the mentally and physically disabled and other marginalized groups. Hitler would later turn the contempt into hate of the “real enemy,” but when he first came to power, contempt helped garner support for implementing eugenic sterilization and euthanasia programs.

Another way for rhetoric and pictures to induce emotions is to make an apparently credible attribution of evildoing or evil intent to destroy us (or both) to the “enemy” or “outgroup,” sometimes while simultaneously strengthening positive feelings like pride, altruism and empathy already self-attributed by ingroup members. The attribution of evildoing to the enemy will tend to induce hate and vengefulness in the ingroup, and the attribution of evil intent to destroy us will tend to induce fear. If strong enough, the hatred will cause the ingroup to regard retaliation as just and the fear will cause deportation or extinction as necessary.

In Nazi Germany, the Nazi’s portrayal of the Jews as disease-spreading rats feeding off the host nation, poisoning its culture and polluting the Aryan race (evil-doings) triggered feelings of hate and vengefulness in German population. The portrayal of the national Jews as butchers and East-European Jews as aliens planning a communist takeover (evil intent to destroy) triggered intense fear. Their hatred of the Jews made retaliation seem just to many ordinary Germans, whereas their fear of the Jews’ taking over the country and then the world made mass deportations and, eventually, genocide, seem necessary.

The Nazi propagandists also used rhetoric and pictures to boost German pride (this is an example of supportive propaganda, in Stanley’s sense) and, in some instances, to rectify the sneaking suspicion from the Allies that something was rotten in the “Third Reich.”

In 1941, word had reached the Allies that there had been a mass deportation of Jews from their homes in Germany. As the pressure to explain what happened to the deported Jews increased, the Nazis established the “model” ghetto Theresienstadt. What was in reality an overcrowded, pest-infected concentration camp was portrayed in Nazi propaganda as a “spa town” where elderly German Jews could enjoy “their golden years” in safety.

In the fall of 1943, following the deportation of Danish Jews to Theresienstadt, the Danish Red Cross announced that they wanted to make a site inspection. To prepare for the visit the Nazis planned and made preparations for an elaborate hoax.

After drawing up the exact route the delegation would take, they ordered the prisoners to paint buildings and enlarge the living space and install furniture and curtains in select buildings. The areas outside were beautified with green turf, flower gardens and benches as well as fake stores, a café with white table cloths, a playground with a sandbox and swing set and a community hall with a stage, a Synagogue, a library and verandas. The streets and buildings were given names with positive connotations such as “Neuegasse” (New Street), and the artistic endeavors admirably carried out by the incarcerated underground was now allowed out in the open.

To avoid giving off the impression that the “village” was overcrowded, the Nazis deported over 7,500 of Jews to death camps, leaving hearty or famous Jews behind to improve their shady image.

On the day of the tour, the Jewish inmates were instructed to dress in good-quality clothing and enact rehearsed narratives, for example, bake fresh bread, showcase wagons with deliveries of fresh produce, play “major league” soccer in the camp square in front of a cheering crowd, serve as members of the Elders' Council, relax on the outdoor park benches or play music on a wooden pavilion in the town square. The tour culminated with a performance of a children's opera, Brundibár. Afterwards the Red Cross affirmed that the conditions at Theresienstadt passed for humane.

Following the visit, the Nazis used the Potemkin village to create the propaganda documentary Theresienstadt. Ein Dokumentarfilm aus dem jüdischen Siedlungsgebiet ( Terezin: A Documentary Film of the Jewish Resettlement Area ) that had been contemplated two years prior to the Red Cross visit. What remains of the documentary shows strong, healthy Jewish laborers and artists working in their different fields of expertise and cheerfully leaving the workplace at the end of the day (“Feierabend”).

The voice-over explains:

The use of free time is left to the discretion of the individual. Often the flow of those headed home goes in one direction: toward the big sporting event in Theresienstadt, the soccer match.

The camera then cuts to a soccer match, professionally enacted against a backdrop of cheering and applauding spectators. After the match we see the players shower in the sports facilities. A tour of the town’s recreational activities follows. The “villagers” are shown taking books out of the lending library, attending academic lectures and enjoying a classical concert.

The camera then cuts to scenes of older children and adults tending to the community garden and then to scenes of residents reading, chatting, knitting, playing cards or relaxing on garden benches. Healthy-looking young girls are shown playing with their life size dolls. The final scene displays a traditional Jewish family having dinner together.

The “model” ghetto Theresienstadt was the most egregious and elaborate piece of pro-Nazi propaganda concocted by the Nazi regime. Other hoaxes were staged in the Nazi’s effort to enrage the German population and justify the war. Footage showing battles at the border between Germany and Poland or ethnic Poles slaughtering German Poles was regularly exhibited in order to intensify hatred or provide evidence for the Nazi claim that Germany wasn’t interested in war but was merely defending themselves out of necessity.

In the third part of this post we look closer at how propaganda and indoctrination served as a catalyst for groupthink . The first part can be found here .

Prager, B. (2008). “Interpreting the Visible Traces of There is sein Stadt,” Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 7, 2: 175-194.

Stanley, J. (2015). How Propaganda Works. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Theresienstadt. Ein Dokumentarfilm aus dem jüdischen Siedlungsgebiet, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1001681 , retrieved on April 10, 2018. The film is sometimes incorrectly referred to as “The Führer Gives the Jews a Village.” See also Margry, K. (1992). “ ‘Theresienstadt’ (1944–1945): The Nazi propaganda film depicting the concentration camp as paradise,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 12, 2.

Berit Brogaard, D.M.Sci., Ph.D. , is a professor of philosophy and the Director of the Brogaard Lab for Multisensory Research at the University of Miami.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Pre-1933 Nazi Propaganda

This page is part of the German Propaganda Archive , a collection of translations of propaganda material from the Nazi and East German eras. It focuses on Nazi propaganda during what they called the Kampfzeit, the years when the party was fighting for political power (1919-1933). For further information, see the FAQ .

I. Material by Joseph Goebbels

- “We Demand” : Goebbels explains what the Nazis want (25 July 1927).

- “I sidor” : An attack on Bernhard Weiss (15 August 1927).

- “Hail Moscow” : Leave the Communist Party and join the Nazis (21 November 1927).

- “ Around the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church ”: Depravity in Berlin (23 January 1928).

- “ The World Enemy ”: An essay attacking international finance (19 March 1928).

- “Why Do We Want to Join the Reichstag?” : Goebbels explains why the Nazis are running for elective office (30 April 1928).

- “And You Really Want to Vote for Me?” : An election satire (7 May 1928).

- “ Why Do We Oppose the Jews ?” An anti-Semitic article (30 July 1928).

- “ When Hitler Speaks ”: In praise of Hitler (19 November 1928).

- “Kütemeyer” : Goebbels’s eulogy for a Berlin Nazi killed in street fighting (26 November 1928).

- “Germans: Buy only from the Jew!” : Goebbels attacks the Jews at Christmas (10 December 1928).

- “Toilet Graffiti” : Goebbels responds to attacks on him (7 January 1929).

- “The Jew” : A typical early attack on the Jews (21 January 1929).

- “Der Führer” : Goebbels on the occasion of Hitler’s 40th birthday (22 April 1929).

- “Raise High the Flag!” : Goebbels begins building the myth of Horst Wessel (27 February 1930).

- “One Hundred and Seven” : On the Nazi election victory in September 1930 (21 September1930).

- “Christmas 1931” : Goebbels on Christmas (December 1931).

- “We are Voting for Hitler” : A 1932 election appeal (7 March 1932).

- “ The Rising Tide ”: After the 10 April 1932 presidential election.

- “Advice for a Dictator” : Goebbels on how to be one (1 September 1932).

- “ The Chancellor without a People ”: After a disappointing election (7 November 1932).

- Lenin or Hitler : One of Goebbels’s early speeches, given often (1926).

- The Nazi-Sozi: What do Nazis believe? (1927).

- Those Damned Nazis : A widely distributed pamphlet first published in 1929.

- “The Storm is Coming”: A speech in Berlin on 9 July 1932. Available in Landmark Speeches of National Socialism .

- “Make Way for Young Germany” : An election speech in Munich on 31 July 1932.

- Goebbels on propaganda at the 1927 Nuremberg Rally

- “Knowledge and Propaganda” : A 1928 lecture on propaganda, some of Goebbels’ most detailed thinking on the matter.

- “Wille und Weg” : A Goebbels essay from 1931 on the role of Nazi propaganda.

- “ The Situation ” (August 1931): Goebbels analyzes the political situation.

II. Other propaganda material

- Posters : A collection of posters from 1921-1933.

- Those Damn Nazis : A widely distributed pamphlet from 1929.

- The Red Plague : An attack on the Social Democrats (August 1930).

- Human Export is Coming !: Germans to be exported to cover reparations (October 1931).

- Hitler to Brüning : Hitler’s response to Chancellor Brüning in December of 1931.

- The Bolshevist Swindle : An early 1932 pamphlet aimed at the Communists.

- The Newspapers Lie! : An early 1932 pamphlet aimed at the Socialists.

- Adolf Hitler the German Worker and Front Soldier: A pamphlet from the presidential election

- Why Hindenburg? : A February or March 1932 pamphlet.

- Facts and Lies about Hitler : A March 1932 pamphlet

- Nazi Emergency Economic Proposals : From about May 1932.

- Bring Down the System! : A pamphlet from summer 1932.

- Hitler re-establishes the NSDAP (1925): Available in my book Landmark Speeches of National Socialism.

- The 1927 Nuremberg Rally : Material from a 1927 Nazi booklet.

- Nazis in Harburg : A 1929 article on Nazi activities in the town of Harburg.

- Anti-Semitic Caricatures from Der Stürmer: 1928-1931 : Taken from Julius Streicher’s weekly.

- Cartoons from Brennessel : The Nazi Party humor magazine, founded in 1931.

- A Hitler rally in Gera : A 1931 article from the Illustrierter Beobachter.

- Nazi factory propaganda in Ludwigshafen : An appeal to factory workers (1931 or 1932).

- The Hitler No One Knows: Parts of a 1932 illustrated book on Hitler.

- Flamethrower : A propaganda flyer from June 1932.

- Hitler Over Germany: Hitler’s aerial speaking tour in 1932.

- Rote Erde : Articles from a 27 October 1932 Nazi newspaper.

- Communists!: A 1932 election flyer aimed at communists in Berlin.

III. Material intended for Nazi propagandists

- “Propaganda” : A 1927 guidebook for Nazi propagandists.

- “How I Treat a Local Group Leader” : a 1931 piece from the Nazi monthly for propagandists, discussing problems in the propaganda system.

- “How I Treat a Speaker”: A 1931 piece from the same periodical discussing problems speakers had with local group leaders.

- Rural Propaganda : A 1932 piece on how to reach the countryside.

- An Analysis of Nazi Propaganda : Written after the July 1932 Reichstag election.

- Reaching the Marxists : A late 1932 essay discussing the difficulties in appealing to Marxists.

Last edited 21 March 2024

My e-mail address is available on the FAQ page .

‘The greatest theft in history’: a new exhibition in Amsterdam offers an unprecedented account of Nazi looting

The two-part show reveals like never before how theft was used as a means of erasing jewish identity, writes ambassador (ret) stuart e. eizenstat, the chair of the united states holocaust memorial council, and the curator julie-marthe cohen.

An installation view of the section Humiliation in Looted . Exhibition design by Bureau Caspar Conijn and the independent spatial designer Lies Willers Photo: Julie-Marthe Cohen

The Holocaust perpetrated by the Nazis and their collaborators against European Jewry in the Second World War was the most comprehensive genocide in recorded history. Two-thirds of Europe’s Jews were exterminated. Many Holocaust museums, including the congressionally authorised United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, initiated by President Carter [at the co-author of this article Stuart E. Eizenstat's recommendation and whose governing council he chairs], and others in the US from Houston, Dallas, Detroit, suburban Chicago, Los Angeles, and Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, all movingly describe the steps that led to the killing of six million Jews, including one and a half million Jewish children, and millions of other victims—the mentally and physically disabled, Roma, Slavs, Poles.

But the Holocaust was also the greatest theft in history, and this has not been catalogued in any museum around the world until now, with the remarkable exhibition Looted , organised by the Jewish Cultural Quarter and the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. It is split into two parts: one focusing on Judaica (Jewish books and ritual objects) at Amsterdam’s Jewish Museum, and the other focusing on art, at the city’s new National Holocaust Museum. The exhibition is accompanied by the illustrated book Dispossessed: Personal Stories of Dispossession and Restitution .

The theft of Jewish property was carried out with the same efficiency, brutality and scale as the physical genocide. It was an essential effort to erase root and branch more than a thousand years of Jewish history, to dehumanise what the Nazis considered an inferior race. They stole personal effects including jewellery, rugs and musical instruments. Many ordinary Germans purchased household items on the cheap, such as pots and pans, that had been confiscated from Jews.

The houses of 26 deported poor Jewish families, a familiar sight in the old Jewish quarter of Amsterdam. Their belongings were looted by the Nazis, but regularly ordinary citizens also took their share. Photo taken in August 1944

Stadsarchief Amsterdam

The Nazis took some 600,000 paintings, the most valuable of which were reserved for Hitler’s planned Reichmuseum in his hometown of Linz, Austria. During the war, the Allies were aware of the Nazi theft of Jewish-owned art, and in the 1943 London Declaration warned neutral countries not to traffic in looted art—with mixed results.

In a dramatic measure, the US created the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives programme, consisting of museum curators, artists, librarians and art historians, the famous Monuments Men, who were embedded in Allied forces as they pushed east toward Berlin. They recovered an estimated 100,000 stolen works and books in one of the great artistic recoveries of history, sorted them out in collecting points in Germany, and under an order from President Harry Truman, repatriated them to the countries from which they had been stolen, with the goal of returning them to their owners. This was done imperfectly, and much of the looted art ended up in public museums and private collections in western countries; even more were taken by Soviet Trophy Brigades to the USSR, where they remain to this day.

Because of the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art I negotiated with 44 countries in 1998, now augmented by the 2009 Terezin Declaration, and most recently by the March 2024 Best Practices for the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, and the understandable fascination with major works of art, the misimpression is that such works were the major focus of the Nazi confiscation. But the vast majority of paintings were more valuable to the families as memorabilia than as expensive art.

More broadly, it obfuscates the even more vast theft of millions of books and cultural and religious objects precious to the families, but symbols of a culture the Nazis wished to extinguish: Hanukkah lamps, Shabbat candlesticks, kiddush cups used for wine to sanctify Shabbat. This aspect of the Holocaust is rarely captured by Holocaust museums around the world—until now.

Hanukkah lamp with a stamp under the base of the bookshop of Louis Lamm, one of the protagonists of the exhibition. The object was possibly created by his father Max Lamm around 1906-33 Gemeindearchiv Buttenwiesen

For the first time, the Nazi cultural genocide, the looting of Judaica, is the subject of an exclusive exhibition, Looted , at the Jewish Museum.

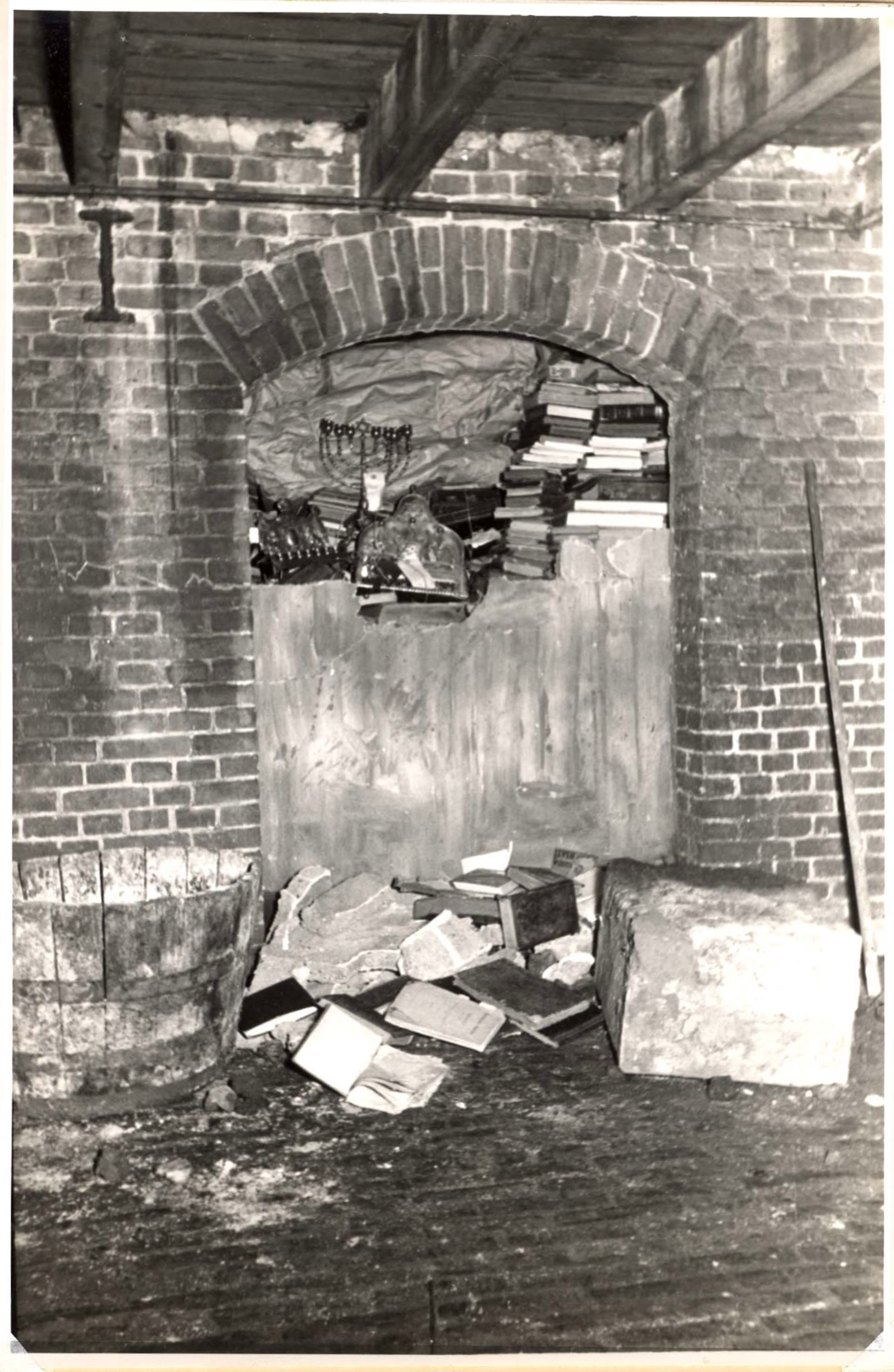

It centres around three personal stories—of Louis Hirschel, Louis Lamm and Leo Isaac Lessmann—and the emotional impact of looting. The men’s stories are presented in the New Synagogue (today part of the Jewish Museum). The war history of this location is integrated into the exhibition: in 1943 the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) looted Jewish books and ritual objects after discovering these objects behind false walls in the cellar of the building. This moment was captured in photographs taken by the ERR, two of which are projected as blow-ups on the wall.

While clearing out the basement of the New Synagogue on Jonas Daniël Meijerplein, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg discovered books and ritual objects behind bricked-up walls. This photograph was taken in October/November 1943

Yad Vashem Photo Archive, Jerusalem

Cultural genocide

The main theme of the exhibition is cultural genocide and how it changed people’s lives. At the very start of the exhibition, the theme is introduced by a quote by Raphael Lemkin, the Polish lawyer who coined the term genocide: “The impact of the concept of genocide could be greatly enriched if the cultural losses that occurred through assassination of civilisations could be brought before the eyes of the world.”

The focus on Judaica illustrates the meaning of cultural genocide in its very essence, because these objects form, nourish and reflect a family’s Jewish identity. Judaica is not about social class: it does not make a distinction between the affluent, “elite” people—who are usually the subject of stories of looting or restitution of art—and ordinary people of lesser means.

In fact, the stories of two of the three protagonists represent the fate of most persecuted Jews. As reflected in the exhibition, they were murdered and left hardly any personal belongings. On display are family photographs and ego-documents—personal letters and diaries of the protagonists—historical photographs and documents, Jewish books and ritual objects, a crate. Alternating photos projected on a wall illustrate the stories of each of the three protagonists. They highlight the emotional impact of looting.

Stories about the Holocaust are, by their nature, emotional stories. Three different “context sections”—Humiliation, Sicherstellung (safeguarding) and Complicit—focusing on the perpetrators enable the visitor to empathise even more with the protagonists of the exhibition. The three stories are intertwined with the Nazi looting and destruction of Jewish cultural assets as part of a process of dehumanisation, which also includes isolation and extermination. The Nazis considered the Jews to be an inferior race and humiliating them was a deliberate strategy to portray them as Untermenschen (sub-human). Humiliation could be best achieved by attacking the symbols of Jewish identity, destroying synagogues and Judaica.

During the November Pogrom of 9/10 November 1938, SS and SA soldiers desecrate a synagogue in the area of Nuremberg, Germany by pouring gasoline on furniture and setting it on fire

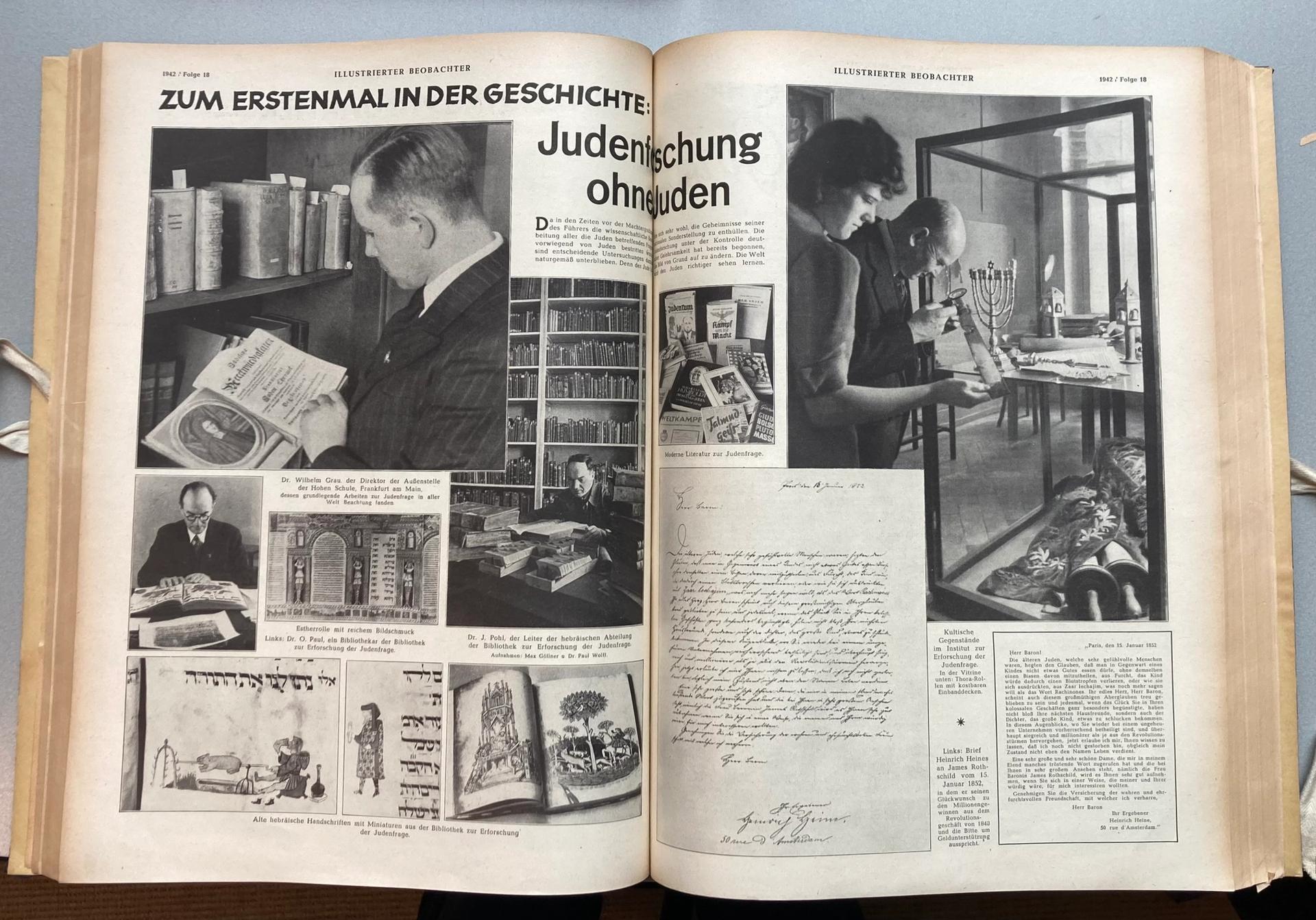

Furthermore, the Nazis “legitimised” the theft of Jewish cultural property through their conviction that the Jews were a threat to the German people. Their property therefore needed to be safeguarded ( sicherstellen ) or destroyed—their use of euphemistic language was a way to disguise their crimes and to mislead the Jews. The ERR was one of the main agencies that looted Judaica. Books were studied in the Institute zur Erforschung der Judenfrage (Institute for Research on the Jewish Question, IEJ) to prove that Jews were an inferior race according to Nazi ideology, legitimising the extermination of the Jews and their culture.

The propaganda magazine Illustrierter Beobachter , on show in the exhibition, with an article “Judenforschung ohne Juden” (“Jewish research without Jews”), dated 30 April 1942. According to the magazine, objective “Jewish research” was now being conducted for the first time. The extensive library of looted books in Alfred Rosenberg’s institute in Frankfurt enabled German scholars to study Judaism. They wanted to unravel secrets and demonstrate that Jews posed the greatest threat to Nazi ideology

Netherlands Institute for War Documentation (NIOD), Amsterdam

The Nazis were not the only ones who robbed the Jews of their property and dignity. Dutch people from all walks of life also participated, which enhanced the feeling of insecurity and fear of their Jewish fellow citizens: some acted out of greed, others were driven by antisemitic sentiments or because simply as part of their job.

For instance, a photograph of empty houses in the Amsterdam Jewish quarter tells the story of the notorious Abraham Puls, who as the owner of a removal company worked for the Möbel-Aktion, which robbed the households of deported Jews. It also speaks to “ordinary” thieves who did the same. A list from May 1940, recording people who had received instructions on prohibited literature, shows that the police helped the Nazis from the very start of the war.

Three personal stories

The drama of the exhibition is that objects get meaning in relation to people. When people are robbed of their belongings, they are robbed of their identity and dignity. The personal stories centre around this shift in the meaning of objects.

The story of Louis Hirschel (1895-1944) is about a dedicated father, rabbi, social worker, and librarian of the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana (ROS), the well-known Jewish library in Amsterdam. After his forced resignation, he managed to rescue 200 rare and valuable works in the library. In 1944 the ERR looted most of the books of the ROS; however, in 1946 the books were returned to Amsterdam from the Offenbach Archival Depot, one of the four American collecting points, and the library was reopened. Hirschel and his family did not survive. Thus, Hirschel’s memory lives on in the books, which have been objects of commemoration ever since.

Farewell note from Louis and Wies Hirschel and their children, probably thrown from the train just after they left Westerbork, when they were deported to Auschwitz on 16 November 1943

Private collection

The story of the devoted antiquarian, publisher and author Louis Lamm (1871-1943), meanwhile, is one of complete destruction. Neither Lamm nor his internationally renowned antiquarian bookshop of Hebrew and Jewish books survived the war.

Louis Lamm and his assistant Salomon Meijer in Louis Lamm’s antiquarian bookshop at 3 Amstel, Amsterdam (1934-36)

Gemeindearchiv Buttenwiesen, courtesy of Johannes Mordstein. New photo: Markus Komposch

Lamm fled to Amsterdam from Berlin in 1933, where he continued his bookshop. He was murdered in Auschwitz in November 1943. In a moving audio interview, his Israeli grandson talks about his unsuccessful search for his grandfather’s collection.

Leo Isaac Lessmann (1891-1971) was the owner of a well-known publishing house in Hamburg and one of the most important collectors of Jewish ritual objects of his time, which symbolised for him a link with true spiritual life. Lessmann survived, but his complete collection remains lost.

This set of a yad (pointer), Torah shield and rimonim (finials) was among the highlights of Leo Isaac Lessmann’s collection. It is of exceptional artistically and cultural historical quality and fashioned by the silversmith Johan Friedrich Wiese, who was active in Hamburg between 1743 and 1752. The photograph is all that remains

Gerstner family, Israel. New photo: Dalia Nava

To safeguard his collection of 1,000 objects, Lessmann sent it to Amsterdam in 1936, where it was stolen in 1943. Lessmann survived in Palestine and searched for his collection in vain. In 1966 he was only partly compensated by Germany. The Nazis had taken from him his collection, fortune, status and native country—as a result he became an altered man, with collecting losing its meaning.

Identified and orphaned objects

“The smell of death emanated from these hundreds of thousands of books and religious objects–orphaned and homeless mute survivors of their murdered owners”—Lucy Dawidowicz-Schildkret, American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, 1989

Two final context sections in the exhibition focus on the Jewish objects that survived. They show that cultural genocide was not complete. As Dawidowicz-Schildkret’s quote shows, these objects became the personification of the lost lives. In a sectioned called Return, objects like the books of the ROS and part of the ritual objects of the Jewish Historical Museum returned home from the American Offenbach Archival Depot. The Orphaned Objects section, meanwhile, tells the story of objects whose owners and users had been murdered, and which were salvaged and distributed by Jewish Cultural Reconstruction to Jewish religious and cultural institutions, mainly in Israel and the US.

Installation view of the section Orphaned Objects

Photo: Julie-Marthe Cohen

As repositories of the pre-war flourishing Jewish European culture, which had been largely destroyed, they now took on a new meaning. They passed that culture on to subsequent generations and ensured that those who once used them were not forgotten.

- Looted , Jewish Museum and National Holocaust Museum, Amsterdam, until 27 October

- Stuart E. Eizenstat has been a leader in Holocaust justice, memory, and restition in five US administrations from Presidents Carter through Clinton, Obama, Trump, and Biden, including being a principle author of the Washington Principles on Nazi-confiscated art endorsed by 44 countries and the 2024 Best Practices for the Washington Princilples, now endorsed by 25 countries. He is currently chairman of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum Council, but is co-authoring this article in his personal capacity.

- Julie-Marthe Cohen is curator of cultural history at the Jewish Museum of Amsterdam. She has worked on tracing Dutch Jewish ceremonial objects lost during the Second World War for more than two decades, and is presently doing a PhD at the University of Amsterdam on the history of looting of Jewish ritual objects and postwar restitution. She is the co-editor of publications including Neglected Witnesses: The Fate of Jewish Ceremonial Objects During the Second World War and After (Institute of Art and Law, Crickadarn, Nr Builth Wells, United Kingdom and Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam, 2011)

- Share full article

Advertisement

Canada Letter

A new national park that rests on indigenous and industrial history.

The collapse of a steel mill project during the Great Depression preserved natural lands linked to First Nations people in Windsor, Ontario.

By Ian Austen

While I occasionally return to my hometown, Windsor, Ontario, to do reporting for other articles, few of them have been as directly linked to my childhood as the story of Canada’s next national urban park. It was a trip that filled in some blanks from my past.

As I wrote in an article , a bill that’s now in its final stages at the Senate with funding in the current federal budget means that a patchwork of lands surrounded by industry, highways, stores and houses will become a national urban park, probably within a year.

[Read: Amid Heavy Industry, Canada’s Newest (and Tiniest) National Park ]

While the final boundaries of the park, as well as its name, have yet to be worked out, one bit of land that is likely to be included was once my childhood hangout. It sat several blocks from my family’s home in the neighborhood, which was developed between the 1950s and 1970s. Back then, everyone called the park Rankin Bush, presumably for the street that once marked its eastern boundary before developers came along.

It had a novel feature: ribbons of crumbling sidewalks and partly grown-over, unpaved roadways crisscrossing the forest. They were useful for cycling, bouncing balls and acting as a platform for experiments with homemade gunpowder that produced, at best, a fizzle and a disappointing puff of smoke. Legends about what older kids did at night in the bush were plentiful, but I can offer no confirmation.

I vaguely knew by the time I was in high school that the sidewalks and roadways were leftovers of a planned company town that was supposed to support a steel mill project before it collapsed during the Great Depression. Now, and then, a section of the unfinished mill sits near the Ojibway Nature Center, which will become the key component of the national park. But the collapse of the steel mill project had the unintended consequence of preserving swaths of tallgrass prairie and woodlands in an area that otherwise had long been consumed by industry and agriculture.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Search the Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Animated Map

- Discussion Question

- Media Essay

- Oral History

- Timeline Event

- Clear Selections

The Press in the Third Reich

Establishing control of the press.

When Adolf Hitler took power in 1933, the Nazis controlled less than three percent of Germany’s 4,700 papers.

The elimination of the German multi-party political system brought about the demise of hundreds of newspapers produced by outlawed political parties. It also allowed the state to seize the printing plants and equipment of the Communist and Social Democratic Parties, which were often turned over directly to the Nazi Party. In the following months, the Nazis established control or exerted influence over independent press organs.

During the first weeks of 1933, the Nazi regime deployed the radio, press, and newsreels to stoke fears of a pending “Communist uprising,” then channeled popular anxieties into political measures that eradicated civil liberties and democracy. SA (Storm Troopers) and members of the Nazi elite paramilitary formation, the SS , took to the streets to brutalize or arrest political opponents and incarcerate them in hastily established detention centers and concentration camps . Nazi thugs broke into opposing political party offices, destroying printing presses and newspapers.

Sometimes using holding companies to disguise new ownership, executives of the Nazi Party-owned publishing house, Franz Eher, established a huge empire that drove out competition and purchased newspapers at below-market prices. Some independent newspapers, particularly conservative newspapers and non-political illustrated weeklies, accommodated to the regime through self-censorship or initiative in dealing with approved topics.

"Aryanization"

Through measures to “Aryanize” businesses, the regime also assumed control of Jewish-owned publishing companies, notably Ullstein and Mosse.

Ullstein, which published the well-known Berlin daily the Vossische Zeitung , was the largest publishing house company in Europe by 1933, employing 10,000 people. In 1933, German officials forced the Ullstein family to resign from the board of the company and, a year later, to sell the company assets.

Owners of a worldwide advertising agency, the Mosse family owned and published a number of major liberal papers much hated by the Nazis, including the Berlin Tageblatt ; the Mosse family fled Germany the day after Hitler took power. Fearing imprisonment or death, reputable journalists also began to flee the country in large numbers. German non-Jewish newspaper owners replaced them in part with ill-trained and inexperienced amateurs loyal to the Nazi Party, as well as with skilled and veteran journalists prepared to collaborate with the regime in order to maintain and even enhance their careers.

The Propaganda Ministry and the Reich Press Chamber

The Propaganda Ministry , through its Reich Press Chamber, assumed control over the Reich Association of the German Press, the guild which regulated entry into the profession. Under the new Editors Law of October 4, 1933, the association kept registries of “racially pure” editors and journalists, and excluded Jews and those married to Jews from the profession. Propaganda Ministry officials expected editors and journalists, who had to register with the Reich Press Chamber to work in the field, to follow the mandates and instructions handed down by the ministry. In paragraph 14 of the law, the regime required editors to omit anything “calculated to weaken the strength of the Reich abroad or at home.”

The Propaganda Ministry aimed further to control the content of news and editorial pages through directives distributed in daily conferences in Berlin and transmitted via the Nazi Party propaganda offices to regional or local papers. Detailed guidelines stated what stories could or could not be reported and how to report the news. Journalists or editors who failed to follow these instructions could be fired or, if believed to be acting with intent to harm Germany, sent to a concentration camp. Rather than suppressing news, the Nazi propaganda apparatus instead sought to tightly control its flow and interpretation and to deny access to alternative sources of news.

Toward the End of World War II

By 1944, a shortage of newspaper and ink forced the Nazi government to limit all newspapers first to eight, then four, and finally, two pages. Of the 4,700 newspapers published in Germany when the Nazis took power in 1933, no more that 1,100 remained. Approximately half were still in the hands of private or institutional owners, but these newspapers operated in strict compliance with government press laws and published material only in accordance with directives issued by the Ministry of Propaganda. While the circulation of these newspapers was approximately 4.4 million, the circulation of the 325 newspapers and their multiple regional editions owned by the Nazi Party was 21 million. Many of these newspapers continued to publish until the end of the war.

Upon occupying Germany, Allied authorities shut down and confiscated presses owned by Nazi Party organs. The last surviving German radio station, located in Flensberg, near the Danish border, made its final broadcast in the name of the National Socialist state on May 9, 1945. After reporting the news of the unconditional capitulation of German forces to the Allies, it went off the air.

After the War

In the postwar US occupation zone of Germany, the military administration believed that the reestablishment of a free press was vital to the denazification and reeducation of Germans, and essential to the creation of democracy in Germany. Therefore, the first German newspaper approved for publication by the US military high command appeared on January 24, 1945, in Aachen, three months after the US forces captured the city.

Among those tried by the Allies as major war criminals at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg were Hans Fritzsche , head of the Radio Division of the Propaganda Ministry, and Julius Streicher , editor of Der Stürmer .

Critical Thinking Questions

- How did the Nazi regime try to control the foreign press?

- What risks may exist when the government controls the press? What can citizens do in the face of this threat?

- Investigate current governments and their relationship with the press within their countries.

Thank you for supporting our work

We would like to thank Crown Family Philanthropies, Abe and Ida Cooper Foundation, the Claims Conference, EVZ, and BMF for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for the Holocaust Encyclopedia. View the list of all donors .

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The Impact of Nazi Propaganda: Visual Essay. Explore a curated selection of primary source propaganda images from Nazi Germany. Propaganda was one of the most important tools the Nazis used to shape the beliefs and attitudes of the German public. Through posters, film, radio, museum exhibits, and other media, they bombarded the German public ...

Nazi propaganda had a key role in the persecution of Jews. Learn more about how Hitler and the Nazi Party used propaganda to facilitate war and genocide.

Propaganda and the Nazi rise to power Hitler pictured with Dr. Dietrich, who was the press chief of the Nazi Party from 1931 until his dismissal shortly before the end of the Second World War. Whilst Goebbels played the primary role in creating Nazi Propaganda and the Hitler myth, Dietrich was also key in spreading the Nazi ideology through publications and newspapers from an early stage.

Nazi Propaganda by Joseph Goebbels: 1933-1945. This is a collection of English translations of Nazi propaganda material by Joseph Goebbels, part of a larger site on Nazi and East German propaganda. It includes many of his weekly articles for Das Reich, as well as a range of his speeches. Some of Goebbels's pre-1933 articles and speeches are ...

Students analyze several examples of Nazi propaganda and consider how the Nazis used media to influence the thoughts, feelings, and actions of individual Germans.

Nazi Propaganda: 1933-1945. Propaganda was central to National Socialist Germany. This page is a collection of English translations of Nazi propaganda for the period 1933-1945, part of a larger site on German propaganda. The goal is to help people understand the great totalitarian systems of the twentieth century by giving them access to ...

On March 15 and March 25 1933, Joseph Goebbels gave two incredibly important speeches about his new role in the Reich Ministry of propaganda, and the use of propaganda. Goebbels wanted a united Germany and his belief was that propaganda was how to achieve this. In his first speech, he calls the Nazi government the "people's government ...

Nazi wartime propaganda for Germans focused on moral justice, defense, and necessity. As the German army rapidly advanced on neighboring countries, war posters and slogans trumpeted German victories. They inspired unity and enthusiasm.

Students define propaganda and practice an image-analysis activity on a piece of propaganda from Nazi Germany.

Nazi efforts to control forms of communication through censorship and propaganda included control of publications, art, theater, music, movies, and radio.

The Nazi propagandists also used rhetoric and pictures to boost German pride (this is an example of supportive propaganda, in Stanley's sense) and, in some instances, to rectify the sneaking ...

We will look at the calculated methodology adopted by the Nazi party under the guidance of both Adolf Hitler and Joseph Göbbels, and analyze the underlying techniques that were used. However, while the breadth and scope of Nazi propaganda were quite exhaustive, and included posters, movies, radio, and the press, this paper will focus on the primary method of rallying the German people - the ...

The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler 's dictatorship of Germany from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation of Nazi policies .

Boyes suggests that "Hitler was a political seducer.". With the use of propaganda, Hitler showed a sign of a totalitarian leader as he established his control and created "immense popularity amongst most Germans" and made a "dictatorship by consent" and shaped a "resurgence of German pride and. Free Essay: As of 1933 to 1939 ...

Before World War 2 (1933-1938), the Nazis used propaganda to brainwash their citizens into believing that Germany was the best country, to create anti-Semitism. After losing the first great war which caused a major depression in the state, Nazi's used Jewish people as a scapegoat for Germany's suffering economy and poor moral.

The Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda played a key role in the Nazis' efforts to cultivate favorable public opinion. Propaganda is biased or misleading information that is used to influence public opinion (see Visual Essay: The Impact of Propaganda in Chapter 6). Hitler created the new ministry on March 13, 1933, and put ...

This propaganda poster is very effective in many ways, including effective use of advertising strategies, superb visual composition, but most of all impactful to the reader, especially if they are pro-Hitler.

Nazi Propaganda (Pre-1933 Material) Pre-1933 Nazi Propaganda. This page is part of the German Propaganda Archive, a collection of translations of propaganda material from the Nazi and East German eras. It focuses on Nazi propaganda during what they called the Kampfzeit, the years when the party was fighting for political power (1919-1933).

Ministry of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment In the days after the Nazi electoral victories of July 1932, Adolf Hitler informed Joseph Goebbels that he intended to make Goebbels director of a new propaganda ministry when the Nazis took over the reins of national government. Goebbels soon envisioned an empire that would control schools, universities, film, radio, and propaganda. "The ...

The propaganda magazine Illustrierter Beobachter, on show in the exhibition, with an article "Judenforschung ohne Juden" ("Jewish research without Jews"), dated 30 April 1942. According to ...

Writing the News Shortly after taking power in January 1933, Adolf Hitler and the Nazis succeeded in destroying Germany's vibrant and diverse newspaper culture. The newly created Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda handed out daily instructions to all German newspapers, Nazi or independent, detailing how the news was to be reported.

Antisemitic propaganda was a common theme in Nazi propaganda. However, it was occasionally reduced for tactical reasons, such as for the 1936 Olympic Games. It was a recurring topic in Hitler's book Mein Kampf (1925-26), which was a key component of Nazi ideology .

A Villa Tainted by Nazism: The former estate of Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, is falling apart. No one knows quite what to do with it . Advertisement

The Propaganda Ministry aimed further to control the content of news and editorial pages through directives distributed in daily conferences in Berlin and transmitted via the Nazi Party propaganda offices to regional or local papers.