- Mardigian Library

- Subject Guides

HHS 225: Stress Management

- Cite and format using APA Style

- Getting started @ Mardigian Library

- Recommended databases

- Journals about Stress and Stress Management

- Books about Stress and Stress Management

- Citation Management Tools

APA Style Template for Google Docs

Here is a Google Docs template that you can use for APA formatted student papers. The template is View Only, so you will need to make a copy to use it. Click the Use Template button in the upper right corner to make a copy.

These template has headers, page numbers, margins, fonts and line spacing already set up for you. Just make a copy and type over the filler text.

APA Template Google Doc

Finding quick Citation Info

Apa style resources.

Here are some general APA Style resources. Scroll down further to see more details about citations and paper formatting.

- APA Style Website The APA Style Website is the official website for APA 7th edition, and includes formatting guidelines for formatting your overall paper including title page setup, tables and figures, as well as guidelines for formatting reference citations. Sample papers are included.

- Excelsior Online Writing Lab: APA Style The Excelsior OWL is an excellent resource for how to write and cite your academic work in APA Style. This is a recommended starting point if you're not sure how to use APA style in your work, and includes helpful multimedia elements.

Several print copies of the APA 7th edition Publication Manual are available for checkout at the Mardigian Library.

(Sorry, APA does not provide an eBook version of this for libraries at the present time.)

APA Style 7th edition Citations (References and In-Text Citations)

If you're new to citation, this brief video will cover an introduction to in-text citations and reference lists in APA 7th edition. Scroll down for more recommended resources about citations.

More information including examples and sample papers can be found at the recommended websites below:

- APA Style Website: Reference Examples Guidelines about references from the official APA Style website.

- APA Style Website: In-text Citations Guidelines for in-text citations from the official APA Style website.

- APA 7th edition quick reference handout This quick reference guide to APA 7th edition citations is handy and includes many commonly cited source types and corresponding in-text citations.

- APA In-text Citation Checklist APA's official In-text citation checklist for the 7th edition.

APA Style 7th edition Formatting for Student Papers

APA Style is more than just citations--it includes guidelines on how you entire paper should be formatted! Here are some quick tutorials and resources for formatting a student paper in APA 7th edition style. (Note that for more formal assignments, like a thesis or dissertation, you should instead follow the formatting guidelines for Professional papers.)

The video below will show you how to format an APA 7th edition student paper using Microsoft Word. Scroll down for more recommended resources about formatting.

- APA Style Website: Paper Format The APA Style website's paper format page includes all of the elements of paper format that you need to follow, including information about the title page, margins and spacing, fonts and headings. Sample papers are included.

- APA Style Website: Academic Writer Tutorial This tutorial is designed for writers new to APA Style. Learn the basics of seventh edition APA Style, including paper elements, format, and organization; academic writing style; grammar and usage; bias-free language; mechanics of style; tables and figures; in-text citations, paraphrasing, and quotations; and reference list format and order.

- Excelsior OWL: APA Formatting Guide The Excelsior OWL includes this great APA 7th edition formatting guide featuring a handy checklist.

- Student Paper Formatting Checklist APA's official student paper formatting checklist.

- << Previous: Books about Stress and Stress Management

- Next: Citation Management Tools >>

- Last Updated: Mar 10, 2024 2:54 PM

- URL: https://guides.umd.umich.edu/stressreduction

Call us at 313-593-5559

Chat with us

Text us: 313-486-5399

Email us your question

- 4901 Evergreen Road Dearborn, MI 48128, USA

- Phone: 313-593-5000

- Maps & Directions

- M+Google Mail

- Emergency Information

- UM-Dearborn Connect

- Wolverine Access

Health & Stress Management: APA Format, 7th Edition

- Find Books & Ebooks

- Find Articles

- Interlibrary Loan

- Find Web Sources

- Find Stress Management Resources

- APA Format, 7th Edition

Introduction

When you reference another’s work in your own papers or essays, you need to cite that author’s work. APA Citation Style is typically used to cite work in social sciences and education fields. When creating a citation, you will need two things:

- In-text or parenthetical citations – located within the body of your paper

- Works Cited or Bibliography – reference list that appears at the end of your paper.

Below is a guide to creating a 7th edition APA reference page. There are also links to external websites for more specific rules.

APA Citation Reference List

Articles

Article found in a database or in print, with one author:

Lastname, F. M . (Year) . Title of article . Title of Journal , volume (issue), pages .

Pajares, F . (2001) . Toward a positive psychology of academic motivation . Journal of Educational Research , 95 (1), 27-35 .

In-Text Citation

( Last name , Year ) OR ( Last name , Year , p. # )

( Pajares , 2001 ) OR ( Pajares , 2001 , p. 28 )

Article found on the open web, with one author:

Lastname, F. M . (Year) . Title of article . Title of Journal , volume if available (issue if available), pages if available. doi: OR

Retrieved from URL

Cohen, P. (2009, October 9 ). Author's personal forecast: Not always sunny, but pleasantly skeptical . The New York Times .

Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/10/books/10ehrenreich.html?_r=1

( Last name , Year ) OR ( Last name , Year , paragraph/page # )

( Cohen , 2009 ) OR ( Cohen , 2009 , para. 7 )

Article (from the open web) with two authors:

Lastname, F. M., & Surname, F. M. (Year) . Title of article . Title of Journal , volume (issue), pages . doi: OR Retrieved from

Norem, J. K., & Chang, E. C. (2002) . The positive psychology of negative thinking . Journal of Clinical Psychology , 58 (9),

993-1001 . https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10094

( Last names , Year ) OR ( Last names , Year , paragraph/page # )

( Norem & Chang , 2002 ) OR ( Norem & Chang , 2002 , p. 997 )

Article with three to six authors:

Lastname, F. M., Surname, F. M., & Lastname, F. M. (Year) . Title of article . Title of Journal , volume (issue), pages.

Jutras, S., Vinay, M. C., & Castonguay, G. (2002). Inner-city children's perceptions about well-being . Canadian Journal of

Community Mental Health , 21 (1), 47-65 .

( First last name et al. , Year ) OR ( Last name , Year , p. # )

( Jutras et al. , 2002 ) AND ( Jutras et al., 2002 , p. 48 )

More than 20 authors? List the first 19 authors and the last author.

Authorone, F. M., Authortwo, F. M., Authorthree, F. M., Authorfour, F. M., Authorfive, F. M., Authorsix, F.M. . . .

Finalauthor, F. M. (Year) . Title of article . Title of Journal , volume (issue), pages .

Book with one author:

Lastname, F. M . (Year). Title of book: Subtitle of book . Publisher .

Bok, S . (2010) . Exploring happiness: From Aristotle to brain science . Yale .

( Last name , Year ) OR ( Last name , Year , p. #)

( Bok , 2010 ) OR ( Bok , 2010 , p. 10)

Books with multiple authors:

The format follows the author format as listed under articles.

An edited book:

Editor, F. M . (Ed.) . (Year) . Title of book: Subtitle of book . Publisher .

Snyder, C.R. & Lopez, S. J. (Eds.) . (2009) . The Oxford handbook of positive psychology . Oxford

University Press .

( Editor , Year ) OR ( Editor , Year , p. #)

( Snyder & Lopez , 2009 ) OR ( Snyder & Lopez , 2009 , p. 78)

Web site with one author:

Lastname, F. M. (Date published) . Title of page . URL

Lopez, S. J. (2000) . The emergence of Positive Psychology: The building of a field of dreams.

http://www.apa.org/apags/profdev/pospsyc.html

( Last name , Date ) OR ( Last name , Date , para. #)

( Lopez , 2000 ) OR ( Lopez , 2000 , para. 5)

Web site with a corporate or organizational author:

Organization name . (Date published) . Title of page . URL

Positive Psychology Center. (2007) . A ttributional style research (Adults) . http://www.ppc.sas.upenn.edu

( Organization name , Date ) OR ( Organization name , Date , para. #)

( Positive Psychology Center , 2007 ) OR ( Positive Psychology Center , 2007 , para. 3)

Image from an online source with a creator listed:

Creator, F. M. (Date created) . Title of image [Description of image] . Retrieved [date] from URL

Swanbrow, D. (2008, July 23) . A happiness ranking of 97 nations [table] . Retrieved January 21, 2010 from

http://www.ur.umich.edu/0708/Jul14_08/23.php

In-Text Citation

( Last name , Year )

( Swanbrow , 2008 )

Image from an online source with no creator listed:

Title of image [Description of image]. (Date created) . Retrieved [date] from URL

( Title of image , Year )

Image from a print source with a creator listed:

Creator, F. M. (Date created) . Title of image. [Continue with title of book or article as appropriate.]

( Last Name , Year )

Updates in APA

Here are some of the changes in the latest version of APA Style:

- APA now has different title page requirements for student papers. This title page does not require a running head and has a different set of information to include. See APA Style: Student Title Page Guide .

- Titles of papers are now bolded, with a blank line before the author's name.

- There is no font requirement as long as the font is legible and consistent.

- The heading for the References list is now bolded.

- APA has simplified in-text citations in regards to multiple authors. For three or more authors, list only the first author's name and then et al.

- In the opposite direction, APA now requires listing up to 20 authors for a source in the references list. This is a change from 8 in the 6th edition. For works with more than 20 authors, list the first 19, insert an ellipsis point, and then list the last author's name.

- For books, no longer list the publication location.

- eBooks should be cited exactly as print books. Do not include a database.

- If an article has an article number, use that in place of the page numbers.

- Include a URL if it will take the reader to the full text without logging in. The article title is formatted regularly and the newspaper or magazine title is italicized.

- Omit the words 'Retrieved from' before the URL. Include the name of the website unless it is the same as the author. Italicize the name of the webpage.

APA Style Resources

- Purdue OWL - APA

- APA Style Central

- Empire State University - Writing Resources

- APA Citation Game

- EasyBib - APA Guide

- Video: APA Style Citation (Word)

- Video: APA Format Reference

Still have questions? Click here .

The information on this page was borrowed from URI LibGuides.

- << Previous: Find Stress Management Resources

- Next: Get Help >>

- Last Updated: Aug 14, 2024 3:11 PM

- URL: https://garrettcollege.libguides.com/health_stress

- Michael Schwartz Library

- Research Guides

HED 474/574: Stress Management

- APA Citations

- Articles / Research Databases

- Books / eBooks

- Google Scholar

- Web Resources

Citing Your Sources

Why are citations important? Why is it necessary to cite?

To avoid plagiarism, you must give proper credit to all sources you use! Whenever you paraphrase or directly quote information, you must cite the sources of the information using a specific citation style. One of the most commonly used citation styles is APA -- the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA) . The current version of the APA Manual is the 7th edition, 2020 . When using APA to cite your sources, you must have a list of References at the end of your paper and corresponding in-text citations in the body of your paper.

Cleveland State University takes plagiarism very seriously. Please see The Code of Student Conduct , which defines plagiarism as "stealing and/or using the ideas or writings of another in a paper or report and claiming them as your own. This includes but is not limited to the use, by paraphrase or direct quotation, of the work of another person without full and clear acknowledgment" (p. 53). Many CSU professors require their students to use a program named Turnitin.com , which checks papers for plagiarism.

Please take the time to become familiar with APA style since you will use it a lot in your courses! There are many RULES to follow when citing sources in APA style, such as order of the elements, capitalization, and punctuation.

- If you do not have access to the paper APA Manual, then refer to the Citation Guides page on the Library's Virtual Reference Desk . It contains links to websites to help you format your citations. A good starting point is the Purdue OWL site.

- The Purdue OWL is an excellent website for learning about APA Citation Style. Once you access the website, explore the links to the left, including In-Text Citations: The Basics and Reference List: Basic Rules . Review the many examples for citing different formats in APA style and the rules pertaining to Authors as well.

- The APA citing help inside a research database is a good starting point, but ALWAYS check the references because the formatting is NOT 100% correct.

- You can use free citation generators like Citation Machine or EasyBib to format citations, but they are not perfect, either! Double check your work!

- Use the References tab in Microsoft Word to insert citations and manage your sources. You can generate a reference list and insert in-text citations in your paper from this References tab. Make sure to check your citations for accuracy!

- Use Mendeley or Zotero , which are free, web-based tools "to help you collect, organize, cite, and share your research sources." See the Mendeley Research Guide and/or the Zotero Research Guide for more information. Mendeley and Zotero are powerful reference management tools, but errors still can occur. Remember that you are responsible for the accuracy of your citations. Make sure to proofread before submitting your work.

Writing Help

If you need help with the writing process (including properly citing sources), then make an appointment with CSU's Writing Center , which is located on the 1st floor of the Michael Schwartz Library.

APA Manual (Paper Version)

The Michael Schwartz Library has copies of the APA Manual available for review.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Articles / Research Databases >>

- Last Updated: May 31, 2024 4:11 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.csuohio.edu/hed474/574

Generate accurate APA citations for free

- Knowledge Base

- APA Style 7th edition

- APA format for academic papers and essays

APA Formatting and Citation (7th Ed.) | Generator, Template, Examples

Published on November 6, 2020 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on January 17, 2024.

The 7th edition of the APA Publication Manual provides guidelines for clear communication , citing sources , and formatting documents. This article focuses on paper formatting.

Generate accurate APA citations with Scribbr

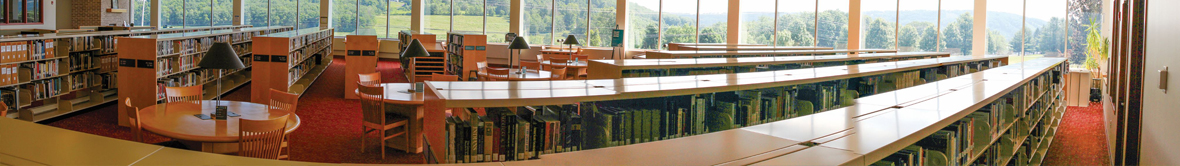

Throughout your paper, you need to apply the following APA format guidelines:

- Set page margins to 1 inch on all sides.

- Double-space all text, including headings.

- Indent the first line of every paragraph 0.5 inches.

- Use an accessible font (e.g., Times New Roman 12pt., Arial 11pt., or Georgia 11pt.).

- Include a page number on every page.

Let an expert format your paper

Our APA formatting experts can help you to format your paper according to APA guidelines. They can help you with:

- Margins, line spacing, and indentation

- Font and headings

- Running head and page numbering

Table of contents

How to set up apa format (with template), apa alphabetization guidelines, apa format template [free download], page header, headings and subheadings, reference page, tables and figures, frequently asked questions about apa format.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

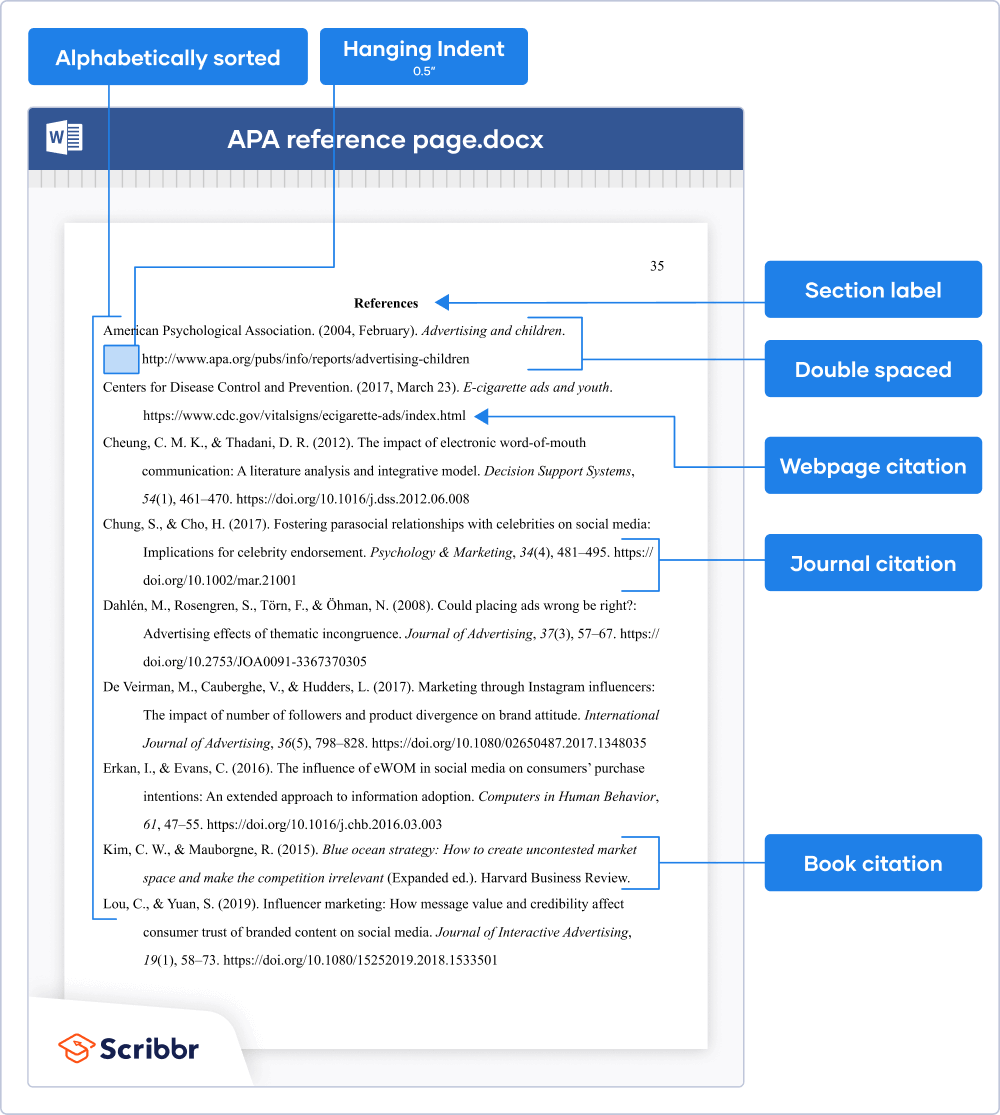

References are ordered alphabetically by the first author’s last name. If the author is unknown, order the reference entry by the first meaningful word of the title (ignoring articles: “the”, “a”, or “an”).

Why set up APA format from scratch if you can download Scribbr’s template for free?

Student papers and professional papers have slightly different guidelines regarding the title page, abstract, and running head. Our template is available in Word and Google Docs format for both versions.

- Student paper: Word | Google Docs

- Professional paper: Word | Google Docs

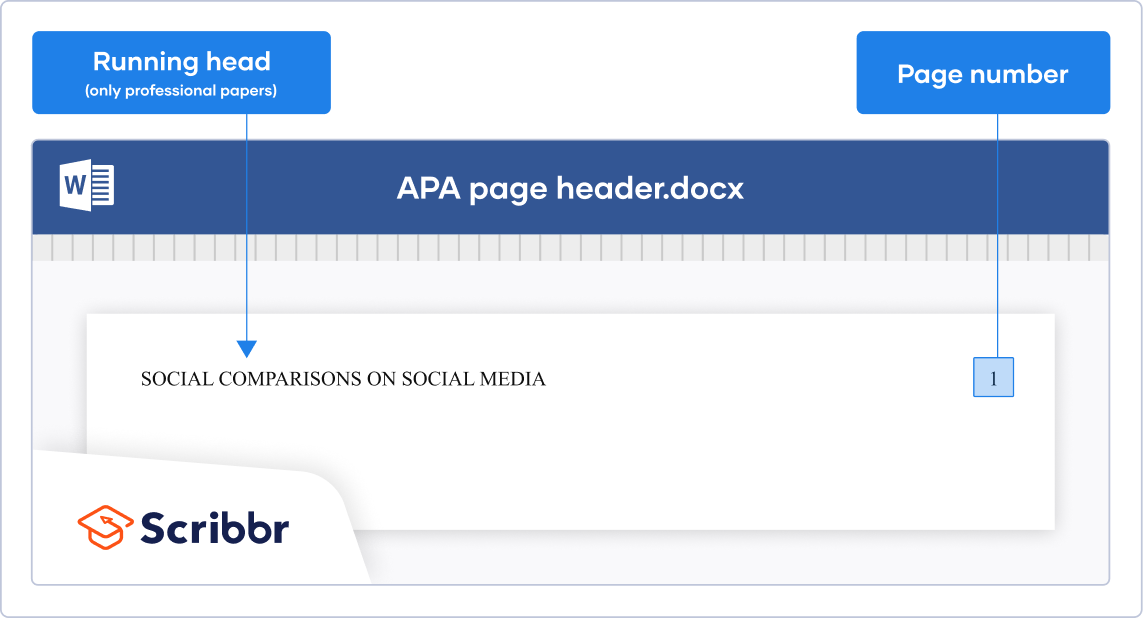

In an APA Style paper, every page has a page header. For student papers, the page header usually consists of just a page number in the page’s top-right corner. For professional papers intended for publication, it also includes a running head .

A running head is simply the paper’s title in all capital letters. It is left-aligned and can be up to 50 characters in length. Longer titles are abbreviated .

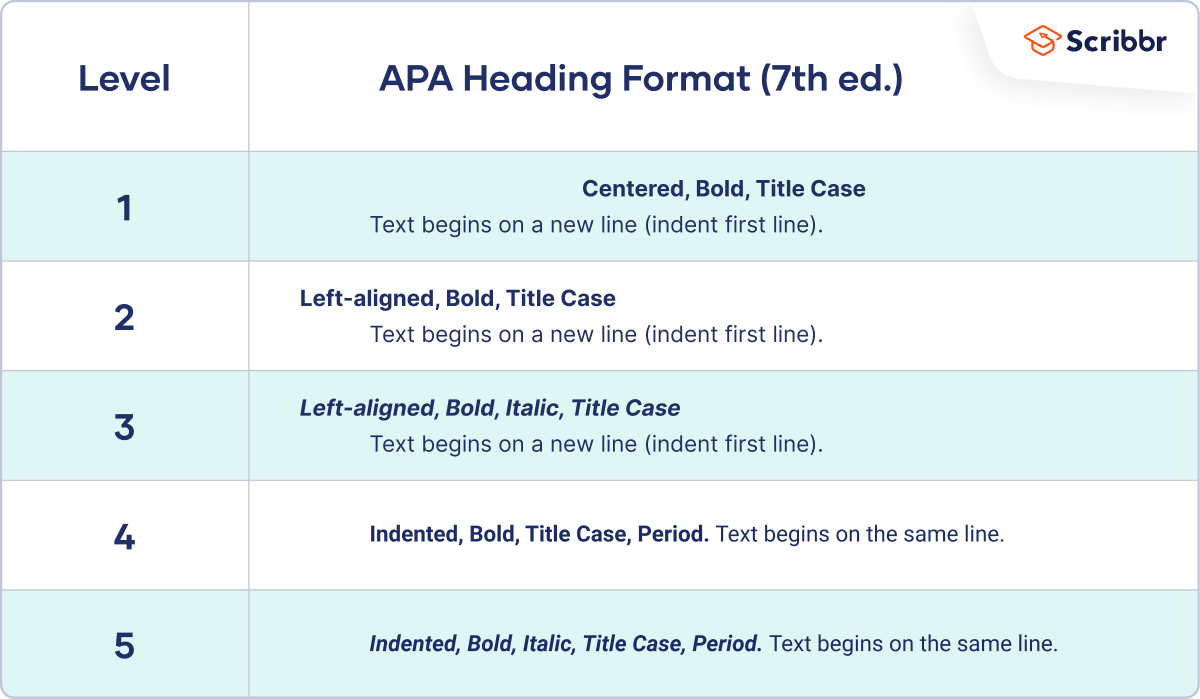

APA headings have five possible levels. Heading level 1 is used for main sections such as “ Methods ” or “ Results ”. Heading levels 2 to 5 are used for subheadings. Each heading level is formatted differently.

Want to know how many heading levels you should use, when to use which heading level, and how to set up heading styles in Word or Google Docs? Then check out our in-depth article on APA headings .

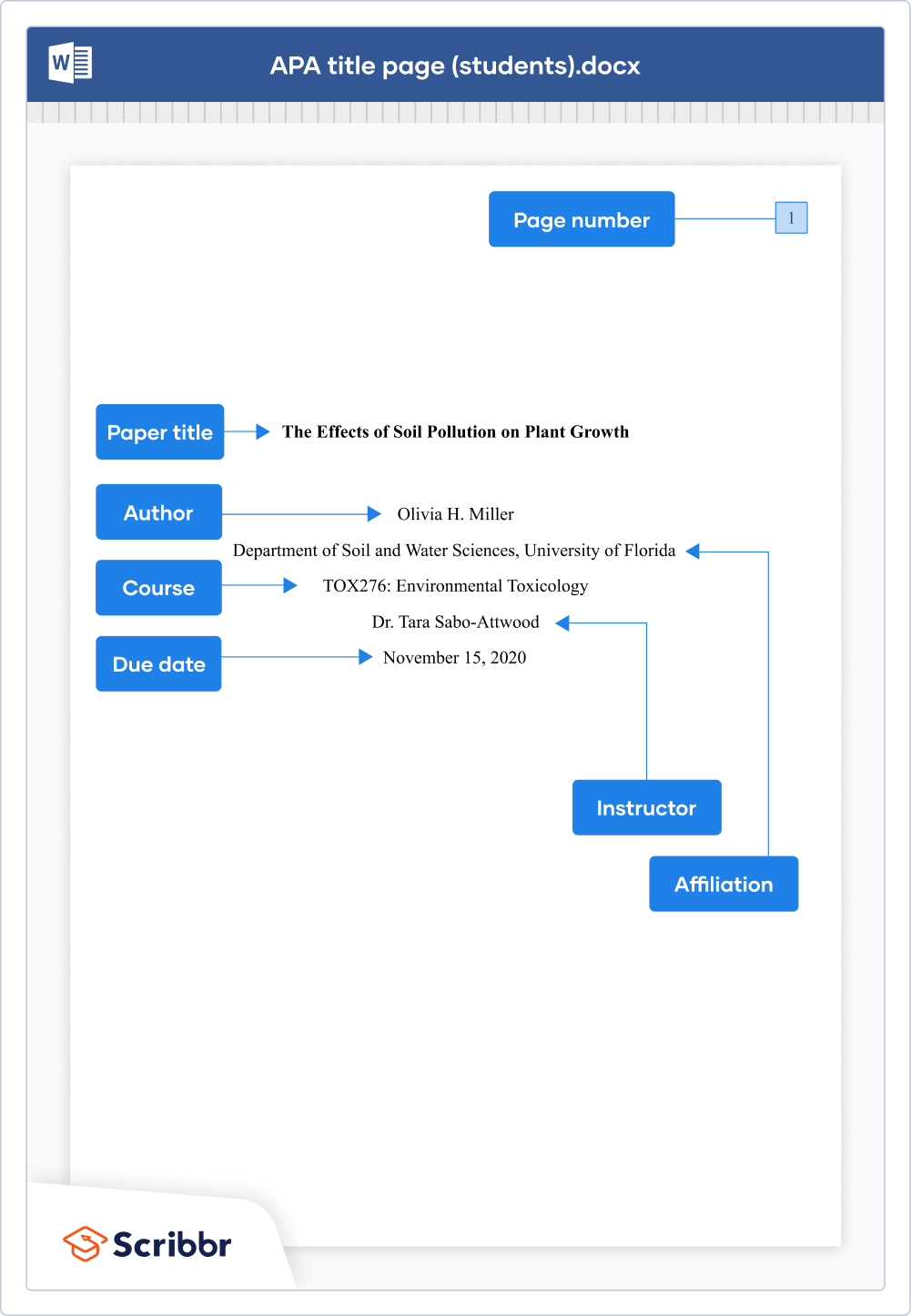

The title page is the first page of an APA Style paper. There are different guidelines for student and professional papers.

Both versions include the paper title and author’s name and affiliation. The student version includes the course number and name, instructor name, and due date of the assignment. The professional version includes an author note and running head .

For more information on writing a striking title, crediting multiple authors (with different affiliations), and writing the author note, check out our in-depth article on the APA title page .

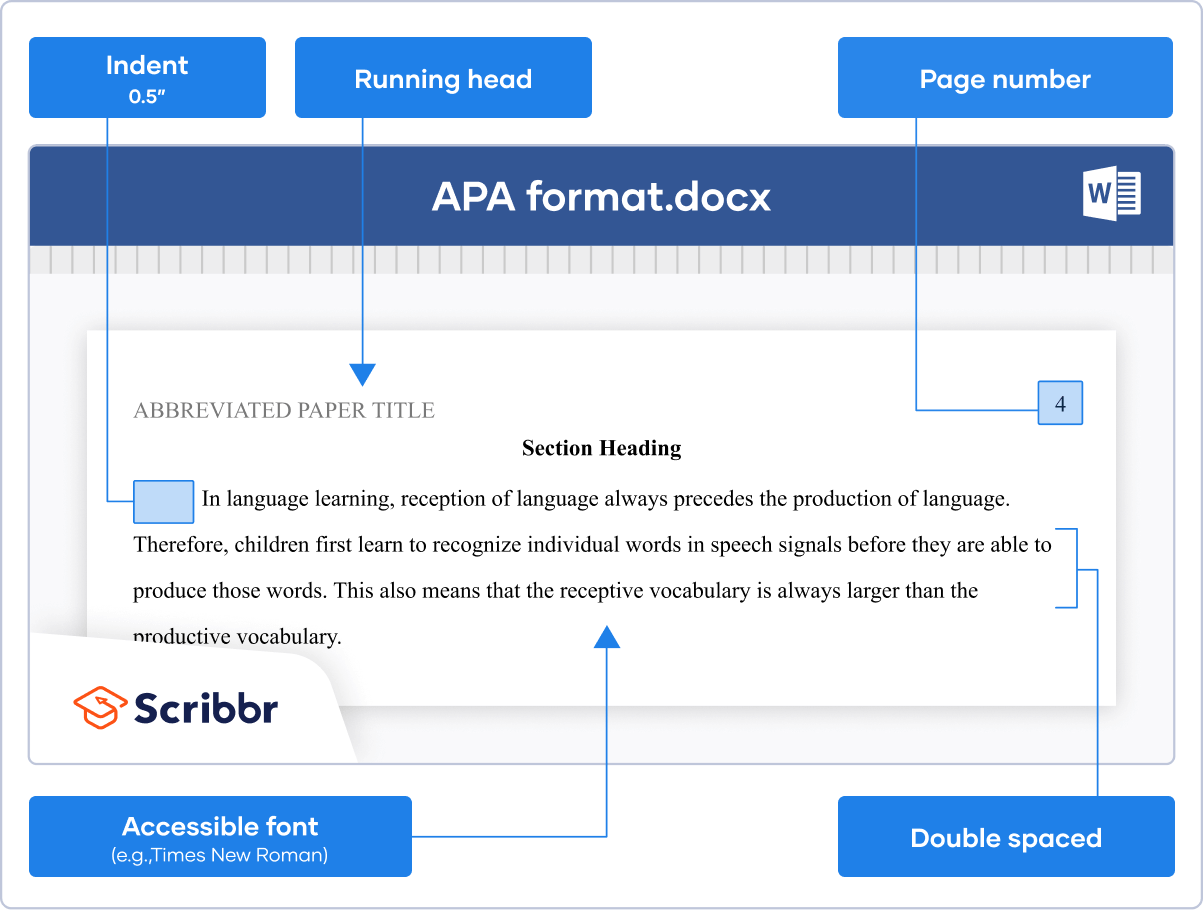

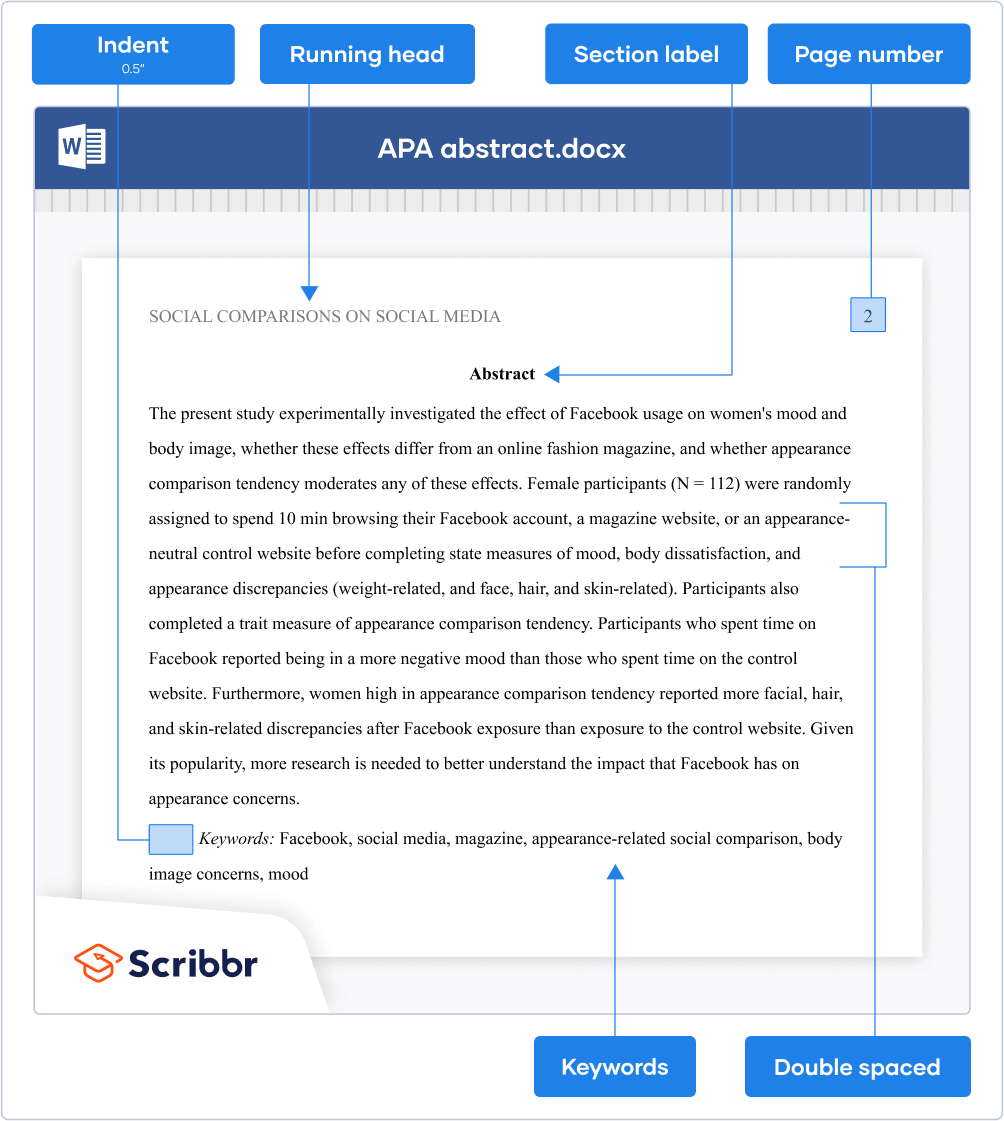

The abstract is a 150–250 word summary of your paper. An abstract is usually required in professional papers, but it’s rare to include one in student papers (except for longer texts like theses and dissertations).

The abstract is placed on a separate page after the title page . At the top of the page, write the section label “Abstract” (bold and centered). The contents of the abstract appear directly under the label. Unlike regular paragraphs, the first line is not indented. Abstracts are usually written as a single paragraph without headings or blank lines.

Directly below the abstract, you may list three to five relevant keywords . On a new line, write the label “Keywords:” (italicized and indented), followed by the keywords in lowercase letters, separated by commas.

APA Style does not provide guidelines for formatting the table of contents . It’s also not a required paper element in either professional or student papers. If your instructor wants you to include a table of contents, it’s best to follow the general guidelines.

Place the table of contents on a separate page between the abstract and introduction. Write the section label “Contents” at the top (bold and centered), press “Enter” once, and list the important headings with corresponding page numbers.

The APA reference page is placed after the main body of your paper but before any appendices . Here you list all sources that you’ve cited in your paper (through APA in-text citations ). APA provides guidelines for formatting the references as well as the page itself.

Creating APA Style references

Play around with the Scribbr Citation Example Generator below to learn about the APA reference format of the most common source types or generate APA citations for free with Scribbr’s APA Citation Generator .

Formatting the reference page

Write the section label “References” at the top of a new page (bold and centered). Place the reference entries directly under the label in alphabetical order.

Finally, apply a hanging indent , meaning the first line of each reference is left-aligned, and all subsequent lines are indented 0.5 inches.

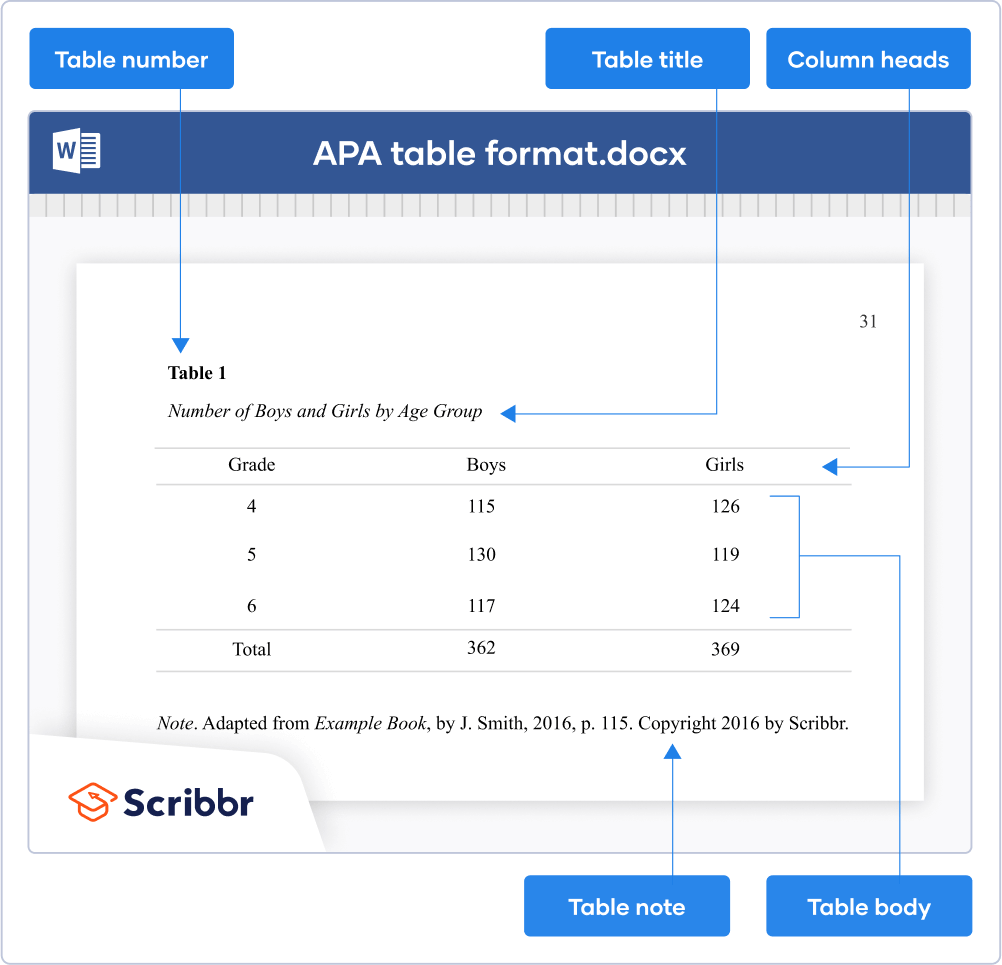

Tables and figures are presented in a similar format. They’re preceded by a number and title and followed by explanatory notes (if necessary).

Use bold styling for the word “Table” or “Figure” and the number, and place the title on a separate line directly below it (in italics and title case). Try to keep tables clean; don’t use any vertical lines, use as few horizontal lines as possible, and keep row and column labels concise.

Keep the design of figures as simple as possible. Include labels and a legend if needed, and only use color when necessary (not to make it look more appealing).

Check out our in-depth article about table and figure notes to learn when to use notes and how to format them.

The easiest way to set up APA format in Word is to download Scribbr’s free APA format template for student papers or professional papers.

Alternatively, you can watch Scribbr’s 5-minute step-by-step tutorial or check out our APA format guide with examples.

APA Style papers should be written in a font that is legible and widely accessible. For example:

- Times New Roman (12pt.)

- Arial (11pt.)

- Calibri (11pt.)

- Georgia (11pt.)

The same font and font size is used throughout the document, including the running head , page numbers, headings , and the reference page . Text in footnotes and figure images may be smaller and use single line spacing.

You need an APA in-text citation and reference entry . Each source type has its own format; for example, a webpage citation is different from a book citation .

Use Scribbr’s free APA Citation Generator to generate flawless citations in seconds or take a look at our APA citation examples .

Yes, page numbers are included on all pages, including the title page , table of contents , and reference page . Page numbers should be right-aligned in the page header.

To insert page numbers in Microsoft Word or Google Docs, click ‘Insert’ and then ‘Page number’.

APA format is widely used by professionals, researchers, and students in the social and behavioral sciences, including fields like education, psychology, and business.

Be sure to check the guidelines of your university or the journal you want to be published in to double-check which style you should be using.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2024, January 17). APA Formatting and Citation (7th Ed.) | Generator, Template, Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/apa-style/format/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

Other students also liked, apa title page (7th edition) | template for students & professionals, creating apa reference entries, beginner's guide to apa in-text citation, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

APA Sample Paper

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Note: This page reflects the latest version of the APA Publication Manual (i.e., APA 7), which released in October 2019. The equivalent resource for the older APA 6 style can be found here .

Media Files: APA Sample Student Paper , APA Sample Professional Paper

This resource is enhanced by Acrobat PDF files. Download the free Acrobat Reader

Note: The APA Publication Manual, 7 th Edition specifies different formatting conventions for student and professional papers (i.e., papers written for credit in a course and papers intended for scholarly publication). These differences mostly extend to the title page and running head. Crucially, citation practices do not differ between the two styles of paper.

However, for your convenience, we have provided two versions of our APA 7 sample paper below: one in student style and one in professional style.

Note: For accessibility purposes, we have used "Track Changes" to make comments along the margins of these samples. Those authored by [AF] denote explanations of formatting and [AWC] denote directions for writing and citing in APA 7.

APA 7 Student Paper:

Apa 7 professional paper:.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

STRESS AND HEALTH: Psychological, Behavioral, and Biological Determinants

Stressors have a major influence upon mood, our sense of well-being, behavior, and health. Acute stress responses in young, healthy individuals may be adaptive and typically do not impose a health burden. However, if the threat is unremitting, particularly in older or unhealthy individuals, the long-term effects of stressors can damage health. The relationship between psychosocial stressors and disease is affected by the nature, number, and persistence of the stressors as well as by the individual’s biological vulnerability (i.e., genetics, constitutional factors), psychosocial resources, and learned patterns of coping. Psychosocial interventions have proven useful for treating stress-related disorders and may influence the course of chronic diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Claude Bernard (1865/1961) noted that the maintenance of life is critically dependent on keeping our internal milieu constant in the face of a changing environment. Cannon (1929) called this “homeostasis.” Selye (1956) used the term “stress” to represent the effects of anything that seriously threatens homeostasis. The actual or perceived threat to an organism is referred to as the “stressor” and the response to the stressor is called the “stress response.” Although stress responses evolved as adaptive processes, Selye observed that severe, prolonged stress responses might lead to tissue damage and disease.

Based on the appraisal of perceived threat, humans and other animals invoke coping responses ( Lazarus & Folkman 1984 ). Our central nervous system (CNS) tends to produce integrated coping responses rather than single, isolated response changes ( Hilton 1975 ). Thus, when immediate fight-or-flight appears feasible, mammals tend to show increased autonomic and hormonal activities that maximize the possibilities for muscular exertion ( Cannon 1929 , Hess 1957 ). In contrast, during aversive situations in which an active coping response is not available, mammals may engage in a vigilance response that involves sympathetic nervous system (SNS) arousal accompanied by an active inhibition of movement and shunting of blood away from the periphery ( Adams et al. 1968 ). The extent to which various situations elicit different patterns of biologic response is called “situational stereotypy” ( Lacey 1967 ).

Although various situations tend to elicit different patterns of stress responses, there are also individual differences in stress responses to the same situation. This tendency to exhibit a particular pattern of stress responses across a variety of stressors is referred to as “response stereotypy” ( Lacey & Lacey 1958 ). Across a variety of situations, some individuals tend to show stress responses associated with active coping, whereas others tend to show stress responses more associated with aversive vigilance ( Kasprowicz et al. 1990 , Llabre et al. 1998 ).

Although genetic inheritance undoubtedly plays a role in determining individual differences in response stereotypy, neonatal experiences in rats have been shown to produce long-term effects in cognitive-emotional responses ( Levine 1957 ). For example, Meaney et al. (1993) showed that rats raised by nurturing mothers have increased levels of central serotonin activity compared with rats raised by less nurturing mothers. The increased serotonin activity leads to increased expression of a central glucocorticoid receptor gene. This, in turn, leads to higher numbers of glucocorticoid receptors in the limbic system and improved glucocorticoid feedback into the CNS throughout the rat’s life. Interestingly, female rats who receive a high level of nurturing in turn become highly nurturing mothers whose offspring also have high levels of glucocorticoid receptors. This example of behaviorally induced gene expression shows how highly nurtured rats develop into low-anxiety adults, who in turn become nurturing mothers with reduced stress responses.

In contrast to highly nurtured rats, pups separated from their mothers for several hours per day during early life have a highly active hypothalamic-pituitary adrenocortical axis and elevated SNS arousal ( Ladd et al. 2000 ). These deprived rats tend to show larger and more frequent stress responses to the environment than do less deprived animals.

Because evolution has provided mammals with reasonably effective homeostatic mechanisms (e.g., baroreceptor reflex) for dealing with short-term stressors, acute stress responses in young, healthy individuals typically do not impose a health burden. However, if the threat is persistent, particularly in older or unhealthy individuals, the long-term effects of the response to stress may damage health ( Schneiderman 1983 ). Adverse effects of chronic stressors are particularly common in humans, possibly because their high capacity for symbolic thought may elicit persistent stress responses to a broad range of adverse living and working conditions. The relationship between psychosocial stressors and chronic disease is complex. It is affected, for example, by the nature, number, and persistence of the stressors as well as by the individual’s biological vulnerability (i.e., genetics, constitutional factors) and learned patterns of coping. In this review, we focus on some of the psychological, behavioral, and biological effects of specific stressors, the mediating psychophysiological pathways, and the variables known to mediate these relationships. We conclude with a consideration of treatment implications.

PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF STRESS

Stressors during childhood and adolescence and their psychological sequelae.

The most widely studied stressors in children and adolescents are exposure to violence, abuse (sexual, physical, emotional, or neglect), and divorce/marital conflict (see Cicchetti 2005 ). McMahon et al. (2003) also provide an excellent review of the psychological consequences of such stressors. Psychological effects of maltreatment/abuse include the dysregulation of affect, provocative behaviors, the avoidance of intimacy, and disturbances in attachment ( Haviland et al. 1995 , Lowenthal 1998 ). Survivors of childhood sexual abuse have higher levels of both general distress and major psychological disturbances including personality disorders ( Polusny & Follett 1995 ). Childhood abuse is also associated with negative views toward learning and poor school performance ( Lowenthal 1998 ). Children of divorced parents have more reported antisocial behavior, anxiety, and depression than their peers ( Short 2002 ). Adult offspring of divorced parents report more current life stress, family conflict, and lack of friend support compared with those whose parents did not divorce ( Short 2002 ). Exposure to nonresponsive environments has also been described as a stressor leading to learned helplessness ( Peterson & Seligman 1984 ).

Studies have also addressed the psychological consequences of exposure to war and terrorism during childhood ( Shaw 2003 ). A majority of children exposed to war experience significant psychological morbidity, including both post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depressive symptoms. For example, Nader et al. (1993) found that 70% of Kuwaiti children reported mild to severe PTSD symptoms after the Gulf War. Some effects are long lasting: Macksound & Aber (1996) found that 43% of Lebanese children continued to manifest post-traumatic stress symptoms 10 years after exposure to war-related trauma.

Exposure to intense and chronic stressors during the developmental years has long-lasting neurobiological effects and puts one at increased risk for anxiety and mood disorders, aggressive dyscontrol problems, hypo-immune dysfunction, medical morbidity, structural changes in the CNS, and early death ( Shaw 2003 ).

Stressors During Adulthood and Their Psychological Sequelae

Life stress, anxiety, and depression.

It is well known that first depressive episodes often develop following the occurrence of a major negative life event ( Paykel 2001 ). Furthermore, there is evidence that stressful life events are causal for the onset of depression (see Hammen 2005 , Kendler et al. 1999 ). A study of 13,006 patients in Denmark, with first psychiatric admissions diagnosed with depression, found more recent divorces, unemployment, and suicides by relatives compared with age- and gender-matched controls ( Kessing et al. 2003 ). The diagnosis of a major medical illness often has been considered a severe life stressor and often is accompanied by high rates of depression ( Cassem 1995 ). For example, a meta-analysis found that 24% of cancer patients are diagnosed with major depression ( McDaniel et al. 1995 ).

Stressful life events often precede anxiety disorders as well ( Faravelli & Pallanti 1989 , Finlay-Jones & Brown 1981 ). Interestingly, long-term follow-up studies have shown that anxiety occurs more commonly before depression ( Angst &Vollrath 1991 , Breslau et al. 1995 ). In fact, in prospective studies, patients with anxiety are most likely to develop major depression after stressful life events occur ( Brown et al. 1986 ).

DISORDERS RELATED TO TRAUMA

Lifetime exposure to traumatic events in the general population is high, with estimates ranging from 40% to 70% ( Norris 1992 ). Of note, an estimated 13% of adult women in the United States have been exposed to sexual assault ( Kilpatrick et al. 1992 ). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association 2000 ) includes two primary diagnoses related to trauma: Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) and PTSD. Both these disorders have as prominent features a traumatic event involving actual or threatened death or serious injury and symptom clusters including re-experiencing of the traumatic event (e.g., intrusive thoughts), avoidance of reminders/numbing, and hyperarousal (e.g., difficulty falling or staying asleep). The time frame for ASD is shorter (lasting two days to four weeks), with diagnosis limited to within one month of the incident. ASD was introduced in 1994 to describe initial trauma reactions, but it has come under criticism ( Harvey & Bryant 2002 ) for weak empirical and theoretical support. Most people who have symptoms of PTSD shortly after a traumatic event recover and do not develop PTSD. In a comprehensive review, Green (1994) estimates that approximately 25% of those exposed to traumatic events develop PTSD. Surveys of the general population indicate that PTSD affects 1 in 12 adults at some time in their life ( Kessler et al. 1995 ). Trauma and disasters are related not only to PTSD, but also to concurrent depression, other anxiety disorders, cognitive impairment, and substance abuse ( David et al. 1996 , Schnurr et al. 2002 , Shalev 2001 ).

Other consequences of stress that could provide linkages to health have been identified, such as increases in smoking, substance use, accidents, sleep problems, and eating disorders. Populations that live in more stressful environments (communities with higher divorce rates, business failures, natural disasters, etc.) smoke more heavily and experience higher mortality from lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder ( Colby et al. 1994 ). A longitudinal study following seamen in a naval training center found that more cigarette smoking occurred on high-stress days ( Conway et al. 1981 ). Life events stress and chronically stressful conditions have also been linked to higher consumption of alcohol ( Linsky et al. 1985 ). In addition, the possibility that alcohol may be used as self-medication for stress-related disorders such as anxiety has been proposed. For example, a prospective community study of 3021 adolescents and young adults ( Zimmerman et al. 2003 ) found that those with certain anxiety disorders (social phobia and panic attacks) were more likely to develop substance abuse or dependence prospectively over four years of follow-up. Life in stressful environments has also been linked to fatal accidents ( Linsky & Strauss 1986 ) and to the onset of bulimia ( Welch et al. 1997 ). Another variable related to stress that could provide a link to health is the increased sleep problems that have been reported after sychological trauma ( Harvey et al. 2003 ). New onset of sleep problems mediated the relationship between post-traumatic stress symptoms and decreased natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity in Hurricane Andrew victims ( Ironson et al. 1997 ).

Variations in Stress Responses

Certain characteristics of a situation are associated with greater stress responses. These include the intensity or severity of the stressor and controllability of the stressor, as well as features that determine the nature of the cognitive responses or appraisals. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, and danger are related to the development of major depression and generalized anxiety ( Kendler et al. 2003 ). Factors associated with the development of symptoms of PTSD and mental health disorders include injury, damage to property, loss of resources, bereavement, and perceived life threat ( Freedy et al. 1992 , Ironson et al. 1997 , McNally 2003 ). Recovery from a stressor can also be affected by secondary traumatization ( Pfefferbaum et al. 2003 ). Other studies have found that multiple facets of stress that may work synergistically are more potent than a single facet; for example, in the area of work stress, time pressure in combination with threat ( Stanton et al. 2001 ), or high demand in combination with low control ( Karasek & Theorell 1990 ).

Stress-related outcomes also vary according to personal and environmental factors. Personal risk factors for the development of depression, anxiety, or PTSD after a serious life event, disaster, or trauma include prior psychiatric history, neuroticism, female gender, and other sociodemographic variables ( Green 1996 , McNally 2003 , Patton et al. 2003 ). There is also some evidence that the relationship between personality and environmental adversity may be bidirectional ( Kendler et al. 2003 ). Levels of neuroticism, emotionality, and reactivity correlate with poor interpersonal relationships as well as “event proneness.” Protective factors that have been identified include, but are not limited to, coping, resources (e.g., social support, self-esteem, optimism), and finding meaning. For example, those with social support fare better after a natural disaster ( Madakaisira & O’Brien 1987 ) or after myocardial infarction ( Frasure-Smith et al. 2000 ). Pruessner et al. (1999) found that people with higher self-esteem performed better and had lower cortisol responses to acute stressors (difficult math problems). Attaching meaning to the event is another protective factor against the development of PTSD, even when horrific torture has occurred. Left-wing political activists who were tortured by Turkey’s military regime had lower rates of PTSD than did nonactivists who were arrested and tortured by the police ( Basoğlu et al. 1994 ).

Finally, human beings are resilient and in general are able to cope with adverse situations. A recent illustration is provided by a study of a nationally representative sample of Israelis after 19 months of ongoing exposure to the Palestinian intifada. Despite considerable distress, most Israelis reported adapting to the situation without substantial mental health symptoms or impairment ( Bleich et al. 2003 ).

BIOLOGICAL RESPONSES TO STRESSORS

Acute stress responses.

Following the perception of an acute stressful event, there is a cascade of changes in the nervous, cardiovascular, endocrine, and immune systems. These changes constitute the stress response and are generally adaptive, at least in the short term ( Selye 1956 ). Two features in particular make the stress response adaptive. First, stress hormones are released to make energy stores available for the body’s immediate use. Second, a new pattern of energy distribution emerges. Energy is diverted to the tissues that become more active during stress, primarily the skeletal muscles and the brain. Cells of the immune system are also activated and migrate to “battle stations” ( Dhabar & McEwen 1997 ). Less critical activities are suspended, such as digestion and the production of growth and gonadal hormones. Simply put, during times of acute crisis, eating, growth, and sexual activity may be a detriment to physical integrity and even survival.

Stress hormones are produced by the SNS and hypothalamic-pituitary adrenocortical axis. The SNS stimulates the adrenal medulla to produce catecholamines (e.g., epinephrine). In parallel, the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus produces corticotropin releasing factor, which in turn stimulates the pituitary to produce adrenocorticotropin. Adrenocorticotropin then stimulates the adrenal cortex to secrete cortisol. Together, catecholamines and cortisol increase available sources of energy by promoting lipolysis and the conversion of glycogen into glucose (i.e., blood sugar). Lipolysis is the process of breaking down fats into usable sources of energy (i.e., fatty acids and glycerol; Brindley & Rollan 1989 ).

Energy is then distributed to the organs that need it most by increasing blood pressure levels and contracting certain blood vessels while dilating others. Blood pressure is increased with one of two hemodynamic mechanisms ( Llabre et al.1998 , Schneiderman & McCabe 1989 ). The myocardial mechanism increases blood pressure through enhanced cardiac output; that is, increases in heart rate and stroke volume (i.e., the amount of blood pumped with each heart beat). The vascular mechanism constricts the vasculature, thereby increasing blood pressure much like constricting a hose increases water pressure. Specific stressors tend to elicit either myocardial or vascular responses, providing evidence of situational stereotypy ( Saab et al. 1992 , 1993 ). Laboratory stressors that call for active coping strategies, such as giving a speech or performing mental arithmetic, require the participant to do something and are associated with myocardial responses. In contrast, laboratory stressors that call for more vigilant coping strategies in the absence of movement, such as viewing a distressing video or keeping one’s foot in a bucket of ice water, are associated with vascular responses. From an evolutionary perspective, cardiac responses are believed to facilitate active coping by shunting blood to skeletal muscles, consistent with the fight-or-flight response. In situations where decisive action would not be appropriate, but instead skeletal muscle inhibition and vigilance are called for, a vascular hemodynamic response is adaptive. The vascular response shunts blood away from the periphery to the internal organs, thereby minimizing potential bleeding in the case of physical assault.

Finally, in addition to the increased availability and redistribution of energy, the acute stress response includes activation of the immune system. Cells of the innate immune system (e.g., macrophages and natural killer cells), the first line of defense, depart from lymphatic tissue and spleen and enter the bloodstream, temporarily raising the number of immune cells in circulation (i.e., leukocytosis). From there, the immune cells migrate into tissues that are most likely to suffer damage during physical confrontation (e.g., the skin). Once at “battle stations,” these cells are in position to contain microbes that may enter the body through wounds and thereby facilitate healing ( Dhabar & McEwen 1997 ).

Chronic Stress Responses

The acute stress response can become maladaptive if it is repeatedly or continuously activated ( Selye 1956 ). For example, chronic SNS stimulation of the cardiovascular system due to stress leads to sustained increases in blood pressure and vascular hypertrophy ( Henry et al. 1975 ). That is, the muscles that constrict the vasculature thicken, producing elevated resting blood pressure and response stereotypy, or a tendency to respond to all types of stressors with a vascular response. Chronically elevated blood pressure forces the heart to work harder, which leads to hypertrophy of the left ventricle ( Brownley et al. 2000 ). Over time, the chronically elevated and rapidly shifting levels of blood pressure can lead to damaged arteries and plaque formation.

The elevated basal levels of stress hormones associated with chronic stress also suppress immunity by directly affecting cytokine profiles. Cytokines are communicatory molecules produced primarily by immune cells (see Roitt et al. 1998 ). There are three classes of cytokines. Proinflammatory cytokines mediate acute inflammatory reactions. Th1 cytokines mediate cellular immunity by stimulating natural killer cells and cytotoxic T cells, immune cells that target intracellular pathogens (e.g., viruses). Finally, Th2 cytokines mediate humoral immunity by stimulating B cells to produce antibody, which “tags” extracellular pathogens (e.g., bacteria) for removal. In a meta-analysis of over 30 years of research, Segerstrom & Miller (2004) found that intermediate stressors, such as academic examinations, could promote a Th2 shift (i.e., an increase in Th2 cytokines relative to Th1 cytokines). A Th2 shift has the effect of suppressing cellular immunity in favor of humoral immunity. In response to more chronic stressors (e.g., long-term caregiving for a dementia patient), Segerstrom & Miller found that proinflammatory, Th1, and Th2 cytokines become dysregulated and lead both to suppressed humoral and cellular immunity. Intermediate and chronic stressors are associated with slower wound healing and recovery from surgery, poorer antibody responses to vaccination, and antiviral deficits that are believed to contribute to increased vulnerability to viral infections (e.g., reductions in natural killer cell cytotoxicity; see Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 2002 ).

Chronic stress is particularly problematic for elderly people in light of immunosenescence, the gradual loss of immune function associated with aging. Older adults are less able to produce antibody responses to vaccinations or combat viral infections ( Ferguson et al. 1995 ), and there is also evidence of a Th2 shift ( Glaser et al. 2001 ). Although research has yet to link poor vaccination responses to early mortality, influenza and other infectious illnesses are a major cause of mortality in the elderly, even among those who have received vaccinations (e.g., Voordouw et al. 2003 ).

PSYCHOSOCIAL STRESSORS AND HEALTH

Cardiovascular disease.

Both epidemiological and controlled studies have demonstrated relationships between psychosocial stressors and disease. The underlying mediators, however, are unclear in most cases, although possible mechanisms have been explored in some experimental studies. An occupational gradient in coronary heart disease (CHD) risk has been documented in which men with relatively low socioeconomic status have the poorest health outcomes ( Marmot 2003 ). Much of the risk gradient in CHD can be eliminated, however, by taking into account lack of perceived job control, which is a potent stressor ( Marmot et al. 1997 ). Other factors include risky behaviors such as smoking, alcohol use, and sedentary lifestyle ( Lantz et al. 1998 ), which may be facilitated by stress. Among men ( Schnall et al. 1994 ) and women ( Eaker 1998 ), work stress has been reported to be a predictor of incident CHD and hypertension ( Ironson 1992 ). However, in women with existing CHD, marital stress is a better predictor of poor prognosis than is work stress ( Orth-Gomer et al. 2000 ).

Although the observational studies cited thus far reveal provocative associations between psychosocial stressors and disease, they are limited in what they can tell us about the exact contribution of these stressors or about how stress mediates disease processes. Animal models provide an important tool for helping to understand the specific influences of stressors on disease processes. This is especially true of atherosclerotic CHD, which takes multiple decades to develop in humans and is influenced by a great many constitutional, demographic, and environmental factors. It would also be unethical to induce disease in humans by experimental means.

Perhaps the best-known animal model relating stress to atherosclerosis was developed by Kaplan et al. (1982) . Their study was carried out on male cynomolgus monkeys, who normally live in social groups. The investigators stressed half the animals by reorganizing five-member social groups at one- to three-month intervals on a schedule that ensured that each monkey would be housed with several new animals during each reorganization. The other half of the animals lived in stable social groups. All animals were maintained on a moderately atherogenic diet for 22 months. Animals were also assessed for their social status (i.e., relative dominance) within each group. The major findings were that ( a ) socially dominant animals living in unstable groups had significantly more atherosclerosis than did less dominant animals living in unstable groups; and ( b ) socially dominant male animals living in unstable groups had significantly more atherosclerosis than did socially dominant animals living in stable groups. Other important findings based upon this model have been that heart-rate reactivity to the threat of capture predicts severity of atherosclerosis ( Manuck et al. 1983 ) and that administration of the SNS-blocking agent propranolol decreases the progression of atherosclerosis ( Kaplan et al. 1987 ). In contrast to the findings in males, subordinate premenstrual females develop greater atherosclerosis than do dominant females ( Kaplan et al. 1984 ) because they are relatively estrogen deficient, tending to miss ovulatory cycles ( Adams et al. 1985 ).

Whereas the studies in cynomolgus monkeys indicate that emotionally stressful behavior can accelerate the progression of atherosclerosis, McCabe et al. (2002) have provided evidence that affiliative social behavior can slow the progression of atherosclerosis in the Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbit. This rabbit model has a genetic defect in lipoprotein clearance such that it exhibits hypercholesterolemia and severe atherosclerosis. The rabbits were assigned to one of three social or behavioral groups: ( a ) an unstable group in which unfamiliar rabbits were paired daily, with the pairing switched each week; ( b ) a stable group, in which littermates were paired daily for the entire study; and ( c ) an individually caged group. The stable group exhibited more affiliative behavior and less agonistic behavior than the unstable group and significantly less atherosclerosis than each of the other two groups. The study emphasizes the importance of behavioral factors in atherogenesis, even in a model of disease with extremely strong genetic determinants.

Upper Respiratory Diseases

The hypothesis that stress predicts susceptibility to the common cold received support from observational studies ( Graham et al. 1986 , Meyer & Haggerty 1962 ). One problem with such studies is that they do not control for exposure. Stressed people, for instance, might seek more outside contact and thus be exposed to more viruses. Therefore, in a more controlled study, people were exposed to a rhinovirus and then quarantined to control for exposure to other viruses ( Cohen et al. 1991 ). Those individuals with the most stressful life events and highest levels of perceived stress and negative affect had the greatest probability of developing cold symptoms. In a subsequent study of volunteers inoculated with a cold virus, it was found that people enduring chronic, stressful life events (i.e., events lasting a month or longer including unemployment, chronic underemployment, or continued interpersonal difficulties) had a high likelihood of catching cold, whereas people subjected to stressful events lasting less than a month did not ( Cohen et al. 1998 ).

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

The impact of life stressors has also been studied within the context of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) spectrum disease. Leserman et al. (2000) followed men with HIV for up to 7.5 years and found that faster progression to AIDS was associated with higher cumulative stressful life events, use of denial as a coping mechanism, lower satisfaction with social support, and elevated serum cortisol.

Inflammation, the Immune System, and Physical Health

Despite the stress-mediated immunosuppressive effects reviewed above, stress has also been associated with exacerbations of autoimmune disease ( Harbuz et al. 2003 ) and other conditions in which excessive inflammation is a central feature, such as CHD ( Appels et al. 2000 ). Evidence suggests that a chronically activated, dysregulated acute stress response is responsible for these associations. Recall that the acute stress response includes the activation and migration of cells of the innate immune system. This effect is mediated by proinflammatory cytokines. During periods of chronic stress, in the otherwise healthy individual, cortisol eventually suppresses proinflammatory cytokine production. But in individuals with autoimmune disease or CHD, prolonged stress can cause proinflammatory cytokine production to remain chronically activated, leading to an exacerbation of pathophysiology and symptomatology.

Miller et al. (2002) proposed the glucocorticoid-resistance model to account for this deficit in proinflammatory cytokine regulation. They argue that immune cells become “resistant” to the effects of cortisol (i.e., a type of glucocorticoid), primarily through a reduction, or downregulation, in the number of expressed cortisol receptors. With cortisol unable to suppress inflammation, stress continues to promote proinflammatory cytokine production indefinitely. Although there is only preliminary empirical support for this model, it could have implications for diseases of inflammation. For example, in rheumatoid arthritis, excessive inflammation is responsible for joint damage, swelling, pain, and reduced mobility. Stress is associated with more swelling and reduced mobility in rheumatoid arthritis patients ( Affleck et al. 1997 ). Similarly, in multiple sclerosis (MS), an overactive immune system targets and destroys the myelin surrounding nerves, contributing to a host of symptoms that include paralysis and blindness. Again, stress is associated with an exacerbation of disease ( Mohr et al. 2004 ). Even in CHD, inflammation plays a role. The immune system responds to vascular injury just as it would any other wound: Immune cells migrate to and infiltrate the arterial wall, setting off a cascade of biochemical processes that can ultimately lead to a thrombosis (i.e., clot; Ross 1999 ). Elevated levels of inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), are predictive of heart attacks, even when controlling for other traditional risk factors (e.g., cholesterol, blood pressure, and smoking; Morrow & Ridker 2000 ). Interestingly, a history of major depressive episodes has been associated with elevated levels of CRP in men ( Danner et al. 2003 ).

Inflammation, Cytokine Production, and Mental Health

In addition to its effects on physical health, prolonged proinflammatory cytokine production may also adversely affect mental health in vulnerable individuals. During times of illness (e.g., the flu), proinflammatory cytokines feed back to the CNS and produce symptoms of fatigue, malaise, diminished appetite, and listlessness, which are symptoms usually associated with depression. It was once thought that these symptoms were directly caused by infectious pathogens, but more recently, it has become clear that proinflammatory cytokines are both sufficient and necessary (i.e., even absent infection or fever) to generate sickness behavior ( Dantzer 2001 , Larson & Dunn 2001 ).

Sickness behavior has been suggested to be a highly organized strategy that mammals use to combat infection ( Dantzer 2001 ). Symptoms of illness, as previously thought, are not inconsequential or even maladaptive. On the contrary, sickness behavior is thought to promote resistance and facilitate recovery. For example, an overall decrease in activity allows the sick individual to preserve energy resources that can be redirected toward enhancing immune activity. Similarly, limiting exploration, mating, and foraging further preserves energy resources and reduces the likelihood of risky encounters (e.g., fighting over a mate). Furthermore, decreasing food intake also decreases the level of iron in the blood, thereby decreasing bacterial replication. Thus, for a limited period, sickness behavior may be looked upon as an adaptive response to the stress of illness.

Much like other aspects of the acute stress response, however, sickness behavior can become maladaptive when repeatedly or continuously activated. Many features of the sickness behavior response overlap with major depression. Indeed, compared with healthy controls, elevated rates of depression are reported in patients with inflammatory diseases such as MS ( Mohr et al. 2004 ) or CHD ( Carney et al. 1987 ). Granted, MS patients face a number of stressors and reports of depression are not surprising. However, when compared with individuals facing similar disability who do not have MS (e.g., car accident victims), MS patients still report higher levels of depression ( Ron & Logsdail 1989 ). In both MS ( Fassbender et al. 1998 ) and CHD ( Danner et al. 2003 ), indicators of inflammation have been found to be correlated with depressive symptomatology. Thus, there is evidence to suggest that stress contributes to both physical and mental disease through the mediating effects of proinflammatory cytokines.

HOST VULNERABILITY-STRESSOR INTERACTIONS AND DISEASE

The changes in biological set points that occur across the life span as a function of chronic stressors are referred to as allostasis, and the biological cost of these adjustments is known as allostatic load ( McEwen 1998 ). McEwen has also suggested that cumulative increases in allostatic load are related to chronic illness. These are intriguing hypotheses that emphasize the role that stressors may play in disease. The challenge, however, is to show the exact interactions that occur among stressors, pathogens, host vulnerability (both constitutional and genetic), and such poor health behaviors as smoking, alcohol abuse, and excessive caloric consumption. Evidence of a lifetime trajectory of comorbidities does not necessarily imply that allostatic load is involved since immunosenescence, genetic predisposition, pathogen exposure, and poor health behaviors may act as culprits.

It is not clear, for example, that changes in set point for variables such as blood pressure are related to cumulative stressors per se, at least in healthy young individuals. Thus, for example, British soldiers subjected to battlefield conditions for more than a year in World War II showed chronic elevations in blood pressure, which returned to normal after a couple of months away from the front ( Graham 1945 ). In contrast, individuals with chronic illnesses such as chronic fatigue syndrome may show a high rate of relapse after a relatively acute stressor such as a hurricane ( Lutgendorf et al. 1995 ). Nevertheless, by emphasizing the role that chronic stressors may play in multiple disease outcomes, McEwen has helped to emphasize an important area of study.

TREATMENT FOR STRESS-RELATED DISORDERS

For PTSD, useful treatments include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), along with exposure and the more controversial Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing ( Foa & Meadows 1997 , Ironson et al. 2002 , Shapiro 1995 ). Psychopharmacological approaches have also been suggested ( Berlant 2001 ). In addition, writing about trauma has been helpful both for affective recovery and for potential health benefit ( Pennebaker 1997 ). For outpatients with major depression, Beck’s CBT ( Beck 1976 ) and interpersonal therapy ( Klerman et al. 1984 ) are as effective as psychopharmacotherapy ( Clinical Practice Guidelines 1993 ). However, the presence of sleep problems or hypercortisolemia is associated with poorer response to psychotherapy ( Thase 2000 ). The combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy seems to offer a substantial advantage over psychotherapy alone for the subset of patients who are more severely depressed or have recurrent depression ( Thase et al. 1997 ). For the treatment of anxiety, it depends partly on the specific disorder [e.g., generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, social phobia], although CBT including relaxation training has demonstrated efficacy in several subtypes of anxiety ( Borkovec & Ruscio 2001 ). Antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors also show efficacy in anxiety ( Ballenger et al. 2001 ), especially when GAD is comorbid with major depression, which is the case in 39% of subjects with current GAD ( Judd et al. 1998 ).

BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS IN CHRONIC DISEASE

Patients dealing with chronic, life-threatening diseases must often confront daily stressors that can threaten to undermine even the most resilient coping strategies and overwhelm the most abundant interpersonal resources. Psychosocial interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM), have a positive effect on the quality of life of patients with chronic disease ( Schneiderman et al. 2001 ). Such interventions decrease perceived stress and negative mood (e.g., depression), improve perceived social support, facilitate problem-focused coping, and change cognitive appraisals, as well as decrease SNS arousal and the release of cortisol from the adrenal cortex. Psychosocial interventions also appear to help chronic pain patients reduce their distress and perceived pain as well as increase their physical activity and ability to return to work ( Morley et al. 1999 ). These psychosocial interventions can also decrease patients’ overuse of medications and utilization of the health care system. There is also some evidence that psychosocial interventions may have a favorable influence on disease progression ( Schneiderman et al. 2001 ).

Morbidity, Mortality, and Markers of Disease Progression

Psychosocial intervention trials conducted upon patients following acute myocardial infarction (MI) have reported both positive and null results. Two meta-analyses have reported a reduction in both mortality and morbidity of approximately 20% to 40% ( Dusseldorp et al. 1999 , Linden et al. 1996 ). Most of these studies were carried out in men. The major study reporting positive results was the Recurrent Coronary Prevention Project (RCPP), which employed group-based CBT, and decreased hostility and depressed affect ( Mendes de Leon et al. 1991 ), as well as the composite medical end point of cardiac death and nonfatal MI ( Friedman et al. 1986 ).

In contrast, the major study reporting null results for medical end points was the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) clinical trial ( Writing Committee for ENRICHD Investigators 2003 ), which found that the intervention modestly decreased depression and increased perceived social support, but did not affect the composite medical end point of death and nonfatal MI. However, a secondary analysis, which examined the effects of the psychosocial intervention within gender by ethnicity subgroups, found significant decreases approaching 40% in both cardiac death and nonfatal MI for white men but not for other subgroups such as minority women ( Schneiderman et al. 2004 ). Although there were important differences between the RCPP and ENRICHD in terms of the objectives of psychosocial intervention and the duration and timing of treatment, it should also be noted that more than 90% of the patients in the RCPP were white men. Thus, because primarily white men, but not other subgroups, may have benefited from the ENRICHD intervention, future studies need to attend to variables that may have prevented morbidity and mortality benefits among gender and ethnic subgroups other than white men.

Psychosocial intervention trials conducted upon patients with cancer have reported both positive and null results with regard to survival ( Classen 1998 ). A number of factors that generally characterized intervention trials that observed significant positive effects on survival were relatively absent in trials that failed to show improved survival. These included: ( a ) having only patients with the same type and severity of cancer within each group, ( b ) creation of a supportive environment, ( c ) having an educational component, and ( d ) provision of stress-management and coping-skills training. In one study that reported positive results, Fawzy et al. (1993) found that patients with early stage melanoma assigned to a six-week cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM) group showed significantly longer survival and longer time to recurrence over a six-year follow-up period compared with those receiving surgery and standard care alone. The intervention also significantly reduced distress, enhanced active coping, and increased NK cell cytotoxicity compared with controls.

Although published studies have not yet shown that psychosocial interventions can decrease disease progression in HIV/AIDS, several studies have significantly influenced factors that have been associated with HIV/AIDS disease progression ( Schneiderman & Antoni 2003 ). These variables associated with disease progression include distress, depressed affect, denial coping, low perceived social support, and elevated serum cortisol ( Ickovics et al. 2001 , Leserman et al. 2000 ). Antoni et al. have used group-based CBSM (i.e., CBT plus relaxation training) to decrease the stress-related effects of HIV+ serostatus notification. Those in the intervention condition showed lower distress, anxiety, and depressed mood than did those in the control condition as well as lower antibody titers of herpesviruses and higher levels of T-helper (CD4) cells, NK cells, and lymphocyte proliferation ( Antoni et al. 1991 , Esterling et al. 1992 ). In subsequent studies conducted upon symptomatic HIV+ men who were not attempting to determine their HIV serostatus, CBSM decreased distress, dysphoria, anxiety, herpesvirus antibody titers, cortisol, and epinephrine ( Antoni et al. 2000a , b ; Lutgendorf et al. 1997 ). Improvement in perceived social support and adaptive coping skills mediated the decreases in distress ( Lutgendorf et al. 1998 ). In summary, it appears that CBSM can positively influence stress-related variables that have been associated with HIV/AIDS progression. Only a randomized clinical trial, however, could document that CBSM can specifically decrease HIV/AIDS disease progression.

Stress is a central concept for understanding both life and evolution. All creatures face threats to homeostasis, which must be met with adaptive responses. Our future as individuals and as a species depends on our ability to adapt to potent stressors. At a societal level, we face a lack of institutional resources (e.g., inadequate health insurance), pestilence (e.g., HIV/AIDS), war, and international terrorism that has reached our shores. At an individual level, we live with the insecurities of our daily existence including job stress, marital stress, and unsafe schools and neighborhoods. These are not an entirely new condition as, in the last century alone, the world suffered from instances of mass starvation, genocide, revolutions, civil wars, major infectious disease epidemics, two world wars, and a pernicious cold war that threatened the world order. Although we have chosen not to focus on these global threats in this paper, they do provide the backdrop for our consideration of the relationship between stress and health.

A widely used definition of stressful situations is one in which the demands of the situation threaten to exceed the resources of the individual ( Lazarus & Folkman 1984 ). It is clear that all of us are exposed to stressful situations at the societal, community, and interpersonal level. How we meet these challenges will tell us about the health of our society and ourselves. Acute stress responses in young, healthy individuals may be adaptive and typically do not impose a health burden. Indeed, individuals who are optimistic and have good coping responses may benefit from such experiences and do well dealing with chronic stressors ( Garmezy 1991 , Glanz & Johnson 1999 ). In contrast, if stressors are too strong and too persistent in individuals who are biologically vulnerable because of age, genetic, or constitutional factors, stressors may lead to disease. This is particularly the case if the person has few psychosocial resources and poor coping skills. In this chapter, we have documented associations between stressors and disease and have described how endocrine-immune interactions appear to mediate the relationship. We have also described how psychosocial stressors influence mental health and how psychosocial treatments may ameliorate both mental and physical disorders. There is much we do not yet know about the relationship between stress and health, but scientific findings being made in the areas of cognitive-emotional psychology, molecular biology, neuroscience, clinical psychology, and medicine will undoubtedly lead to improved health outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by NIH grants P01-MH49548, P01- HL04726, T32-HL36588, R01-MH66697, and R01-AT02035. We thank Elizabeth Balbin, Adam Carrico, and Orit Weitzman for library research.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adams DB, Bacelli G, Mancia G, Zanchetti A. Cardiovascular changes during naturally elicited fighting behavior in the cat. Am. J. Physiol. 1968; 216 :1226–1235. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Adams MR, Kaplan JR, Koritnik DR. Psychosocial influences on ovarian, endocrine and ovulatory function in Macaca fascicularis . Physiol. Behav. 1985; 35 :935–940. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Affleck G, Urrows S, Tennen H, Higgins P, Pav D, Aloisi R. A dual pathway model of daily stressor effects on rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Behav. Med. 1997; 19 :161–170. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV-TR. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Am. Psychiatr. Assoc.; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Angst J, Vollrath M. The natural history of anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1991; 84 :446–452. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antoni MH, Baggett L, Ironson G, LaPerriere A, Klimas N, et al. Cognitive behavioral stress management intervention buffers distress responses and elevates immunologic markers following notification of HIV-1 seropositivity. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991; 59 :906–915. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antoni MH, Cruess DG, Cruess S, Lutgendorf S, Kumar M, et al. Cognitive behavioral stress management intervention effects on anxiety, 24-hour urinary catecholamine output, and T-cytotoxic/suppressor cells over time among symptomatic HIV-infected gay men. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000a; 68 :31–45. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antoni MH, Cruess S, Cruess DG, Kumar M, Lutgendorf S, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management reduces distress and 24-hour urinary free cortisol output among symptomatic HIV-infected gay men. Ann. Behav. Med. 2000b; 22 :29–37. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Appels A, Bar FW, Bar J, Bruggeman C, de Bates M. Inflammation, depressive symptomatology, and coronary artery disease. Psychosom. Med. 2000; 62 :601–605. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, Nutt DJ, Borkovec TD, et al. Consensus statement on generalized anxiety disorder from the international consensus group on depression and anxiety. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2001; 62 :53–58. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Başoğlu M, Parker M, Parker Ö, Özmen E, Marks I, et al. Psychological effects of torture: a comparison of tortured with non-tortured political activists in Turkey. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1994; 151 :76–81. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baum A. Stress, intrusive imagery, and chronic distress. Health Psychol. 1990; 9 :653–675. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck AT. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. New York: Int. Univ. Press; 1976. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berlant JL. Topiramate in posttraumatic stress disorder: preliminary clinical observations. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2001; 62 :60–63. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernard C. An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine. Transl. HC Greene. New York: Collier; 18651961. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bleich A, Gelkopf M, Solomon Z. Exposure to terrorism, stress-related mental health symptoms, and coping behaviors among a nationally representative sample in Israel. JAMA. 2003; 290 :612–620. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borkovec TD, Ruscio AM. Psychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2001; 61 :37–42. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E. Sex differences in depression: a role for preexisting anxiety. Psychiatr. Res. 1995; 58 :1–12. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brindley D, Rollan Y. Possible connections between stress, diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and altered lipoprotein metabolism that may result in atherosclerosis. Clin. Sci. 1989; 77 :453–461. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown GW, Bifulco A, Harris T, Bridge L. Life stress, chronic subclinical symptoms and vulnerability to clinical depression. J. Affect. Disord. 1986; 11 :1–19. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brownley KA, Hurwitz BE, Schneiderman N. Cardiovascular psychophysiology. In: Cacioppo JT, Tassinary LG, Berntson GG, editors. Handbook of Psychophysiology. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge Univ.; 2000. pp. 224–264. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cannon WB. Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage. 2nd ed. New York: Appleton; 1929. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carney RM, Rich MW, Tevelde A, Saini J, Clark K, Jaffe AS. Major depressive disorder in coronary artery disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 1987; 60 :1273–1275. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cassem EH. Depressive disorders in the medically ill: an overview. Psychosomatics. 1995; 36 :S2–S10. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cicchetti D. Child maltreatment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005; 1 :409–438. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Classen C, Sephton SE, Diamond S, Spiegel D. Studies of life-extending psychosocial interventions. In: Holland J, editor. Textbook of Psycho-Oncology. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 1998. pp. 730–742. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clinical Practice Guidelines. No. 5. Depression in Primary Care. Vol. 2: Treatment of Major Depression. Rockville, MD: US Dept. Health Hum. Serv., Agency Health Care Policy Res.; 1993. AHCPR Publ. 93-0551.

- Cohen S, Frank E, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP, Rabin BS, Gwaltney JM., Jr Types of stressors that increase susceptibility to the common cold in healthy adults. Health Psychol. 1998; 17 :214–223. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen S, Tyrrell DA, Smith AP. Psychological stress and susceptibility to the common cold. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991; 325 :606–612. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Colby JP, Linsky AS, Straus MA. Social stress and state-to-state differences in smoking-related mortality in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 1994; 38 :373–381. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Conway TL, Vickers RR, Ward HW, Rahe RH. Occupational stress and variation in cigarette, coffee and alcohol consumption. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1981; 22 :156–165. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Danner M, Kasl SV, Abramson JL, Vaccarion V. Association between depression and elevated C-reactive protein. Psychosom. Med. 2003; 65 :347–356. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dantzer R. Cytokine-induced sickness behavior: Where do we stand? Brain Behav. Immun. 2001; 15 :7–24. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]