- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How We Use Abstract Thinking

MoMo Productions / Getty Images

- How It Develops

Abstract thinking, also known as abstract reasoning, involves the ability to understand and think about complex concepts that, while real, are not tied to concrete experiences, objects, people, or situations.

Abstract thinking is considered a type of higher-order thinking, usually about ideas and principles that are often symbolic or hypothetical. This type of thinking is more complex than the type of thinking that is centered on memorizing and recalling information and facts.

Examples of Abstract Thinking

Examples of abstract concepts include ideas such as:

- Imagination

While these things are real, they aren't concrete, physical things that people can experience directly via their traditional senses.

You likely encounter examples of abstract thinking every day. Stand-up comedians use abstract thinking when they observe absurd or illogical behavior in our world and come up with theories as to why people act the way they do.

You use abstract thinking when you're in a philosophy class or when you're contemplating what would be the most ethical way to conduct your business. If you write a poem or an essay, you're also using abstract thinking.

With all of these examples, concepts that are theoretical and intangible are being translated into a joke, a decision, or a piece of art. (You'll notice that creativity and abstract thinking go hand in hand.)

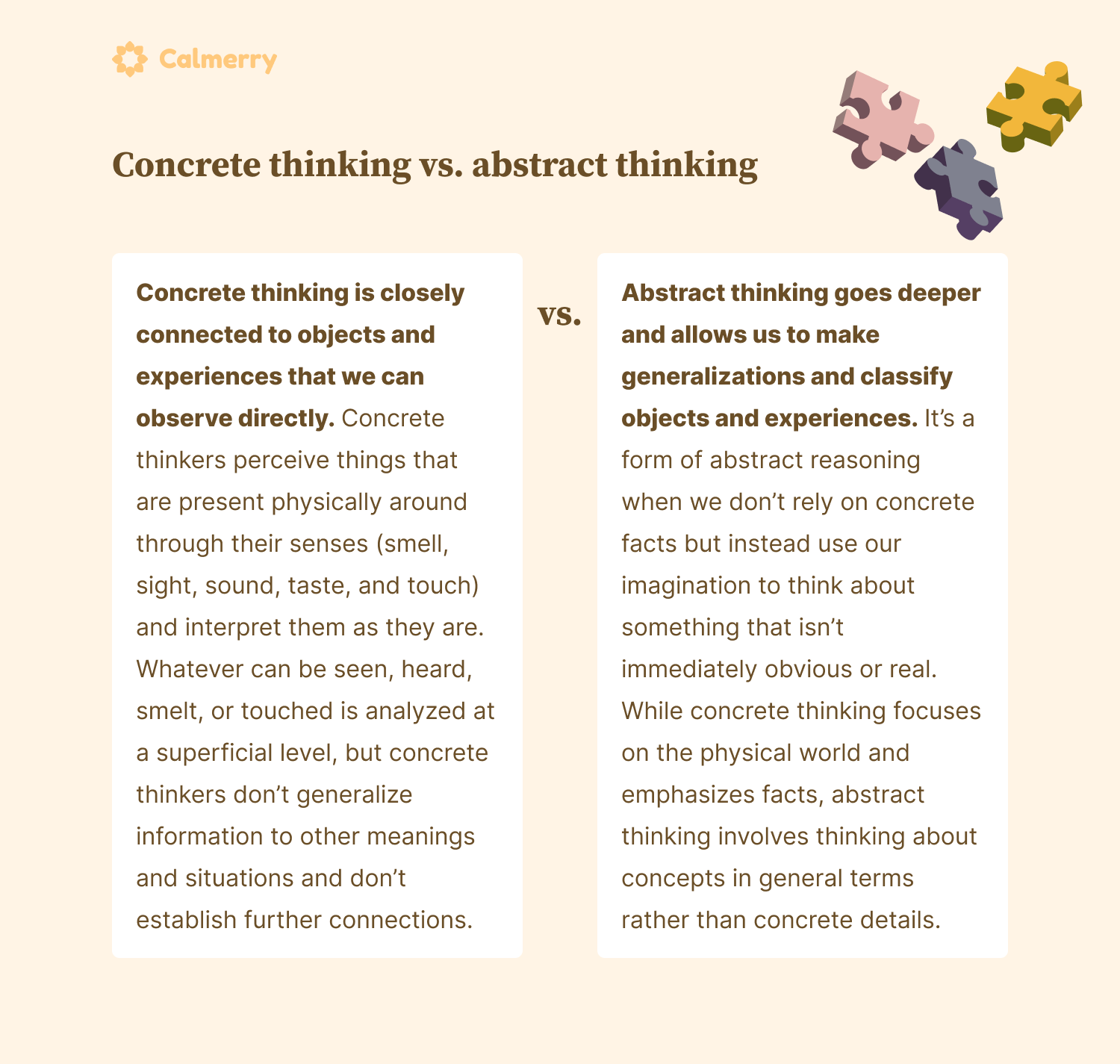

Abstract Thinking vs. Concrete Thinking

One way of understanding abstract thinking is to compare it with concrete thinking. Concrete thinking, also called concrete reasoning, is tied to specific experiences or objects that can be observed directly.

Research suggests that concrete thinkers tend to focus more on the procedures involved in how a task should be performed, while abstract thinkers are more focused on the reasons why a task should be performed.

It is important to remember that you need both concrete and abstract thinking skills to solve problems in day-to-day life. In many cases, you utilize aspects of both types of thinking to come up with solutions.

Other Types of Thinking

Depending on the type of problem we face, we draw from a number of different styles of thinking, such as:

- Creative thinking : This involves coming up with new ideas, or using existing ideas or objects to come up with a solution or create something new.

- Convergent thinking : Often called linear thinking, this is when a person follows a logical set of steps to select the best solution from already-formulated ideas.

- Critical thinking : This is a type of thinking in which a person tests solutions and analyzes any potential drawbacks.

- Divergent thinking : Often called lateral thinking, this style involves using new thoughts or ideas that are outside of the norm in order to solve problems.

How Abstract Thinking Develops

While abstract thinking is an essential skill, it isn’t something that people are born with. Instead, this cognitive ability develops throughout the course of childhood as children gain new abilities, knowledge, and experiences.

The psychologist Jean Piaget described a theory of cognitive development that outlined this process from birth through adolescence and early adulthood. According to his theory, children go through four distinct stages of intellectual development:

- Sensorimotor stage : During this early period, children's knowledge is derived primarily from their senses.

- Preoperational stage : At this point, children develop the ability to think symbolically.

- Concrete operational stage : At this stage, kids become more logical but their understanding of the world tends to be very concrete.

- Formal operational stage : The ability to reason about concrete information continues to grow during this period, but abstract thinking skills also emerge.

This period of cognitive development when abstract thinking becomes more apparent typically begins around age 12. It is at this age that children become more skilled at thinking about things from the perspective of another person. They are also better able to mentally manipulate abstract ideas as well as notice patterns and relationships between these concepts.

Uses of Abstract Thinking

Abstract thinking is a skill that is essential for the ability to think critically and solve problems. This type of thinking is also related to what is known as fluid intelligence , or the ability to reason and solve problems in unique ways.

Fluid intelligence involves thinking abstractly about problems without relying solely on existing knowledge.

Abstract thinking is used in a number of ways in different aspects of your daily life. Some examples of times you might use this type of thinking:

- When you describe something with a metaphor

- When you talk about something figuratively

- When you come up with creative solutions to a problem

- When you analyze a situation

- When you notice relationships or patterns

- When you form a theory about why something happens

- When you think about a problem from another point of view

Research also suggests that abstract thinking plays a role in the actions people take. Abstract thinkers have been found to be more likely to engage in risky behaviors, where concrete thinkers are more likely to avoid risks.

Impact of Abstract Thinking

People who have strong abstract thinking skills tend to score well on intelligence tests. Because this type of thinking is associated with creativity, abstract thinkers also tend to excel in areas that require creativity such as art, writing, and other areas that benefit from divergent thinking abilities.

Abstract thinking can have both positive and negative effects. It can be used as a tool to promote innovative problem-solving, but it can also lead to problems in some cases:

- Bias : Research also suggests that it can sometimes promote different types of bias . As people seek to understand events, abstract thinking can sometimes cause people to seek out patterns, themes, and relationships that may not exist.

- Catastrophic thinking : Sometimes these inferences, imagined scenarios, and predictions about the future can lead to feelings of fear and anxiety. Instead of making realistic predictions, people may catastrophize and imagine the worst possible potential outcomes.

- Anxiety and depression : Research has also found that abstract thinking styles are sometimes associated with worry and rumination . This thinking style is also associated with a range of conditions including depression , anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) .

Conditions That Impact Abstract Thinking

The presence of learning disabilities and mental health conditions can affect abstract thinking abilities. Conditions that are linked to impaired abstract thinking skills include:

- Learning disabilities

- Schizophrenia

- Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

The natural aging process can also have an impact on abstract thinking skills. Research suggests that the thinking skills associated with fluid intelligence peak around the ages of 30 or 40 and begin to decline with age.

Tips for Reasoning Abstractly

While some psychologists believe that abstract thinking skills are a natural product of normal development, others suggest that these abilities are influenced by genetics, culture, and experiences. Some people may come by these skills naturally, but you can also strengthen these abilities with practice.

Some strategies that you might use to help improve your abstract thinking skills:

- Think about why and not just how : Abstract thinkers tend to focus on the meaning of events or on hypothetical outcomes. Instead of concentrating only on the steps needed to achieve a goal, consider some of the reasons why that goal might be valuable or what might happen if you reach that goal.

- Reframe your thinking : When you are approaching a problem, it can be helpful to purposefully try to think about the problem in a different way. How might someone else approach it? Is there an easier way to accomplish the same thing? Are there any elements you haven't considered?

- Consider the big picture : Rather than focusing on the specifics of a situation, try taking a step back in order to view the big picture. Where concrete thinkers are more likely to concentrate on the details, abstract thinkers focus on how something relates to other things or how it fits into the grand scheme of things.

Abstract thinking allows people to think about complex relationships, recognize patterns, solve problems, and utilize creativity. While some people tend to be naturally better at this type of reasoning, it is a skill that you can learn to utilize and strengthen with practice.

It is important to remember that both concrete and abstract thinking are skills that you need to solve problems and function successfully.

Gilead M, Liberman N, Maril A. From mind to matter: neural correlates of abstract and concrete mindsets . Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci . 2014;9(5):638-45. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst031

American Psychological Association. Creative thinking .

American Psychological Association. Convergent thinking .

American Psychological Association. Critical thinking .

American Psychological Association. Divergent thinking .

Lermer E, Streicher B, Sachs R, Raue M, Frey D. The effect of abstract and concrete thinking on risk-taking behavior in women and men . SAGE Open . 2016;6(3):215824401666612. doi:10.1177/2158244016666127

Namkoong J-E, Henderson MD. Responding to causal uncertainty through abstract thinking . Curr Dir Psychol Sci . 2019;28(6):547-551. doi:10.1177/0963721419859346

White R, Wild J. "Why" or "How": the effect of concrete versus abstract processing on intrusive memories following analogue trauma . Behav Ther . 2016;47(3):404-415. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2016.02.004

Williams DL, Mazefsky CA, Walker JD, Minshew NJ, Goldstein G. Associations between conceptual reasoning, problem solving, and adaptive ability in high-functioning autism . J Autism Dev Disord . 2014 Nov;44(11):2908-20. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2190-y

Oh J, Chun JW, Joon Jo H, Kim E, Park HJ, Lee B, Kim JJ. The neural basis of a deficit in abstract thinking in patients with schizophrenia . Psychiatry Res . 2015;234(1):66-73. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.08.007

Hartshorne JK, Germine LT. When does cognitive functioning peak? The asynchronous rise and fall of different cognitive abilities across the life span . Psychol Sci. 2015;26(4):433-43. doi:10.1177/0956797614567339

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

What is Abstract Thinking? Understanding the Power of Creative Thought

When we think about thinking, we usually imagine it as a straightforward process of weighing options and making decisions. However, there is a more complex and abstract thinking type. Abstract thinking involves understanding and thinking about complex concepts not tied to concrete experiences, objects, people, or situations.

Abstract thinking is a type of higher-order thinking that usually deals with ideas and principles that are often symbolic or hypothetical. It is the ability to think about things that are not physically present and to look at the broader significance of ideas and information rather than the concrete details. Abstract thinkers are interested in the deeper meaning of things and the bigger picture. They can see patterns and connections between seemingly unrelated concepts and ideas. For example, when we listen to a piece of music, we may feel a range of emotions that are not directly related to the lyrics or melody. Abstract thinkers can understand and appreciate the complex interplay of elements that create this emotional response.

Understanding Abstract Thinking

Humans can think about concepts and ideas that are not physically present. This is known as abstract thinking. It is a type of higher-order thinking that involves processing often symbolic or hypothetical information.

Defining Abstract Thinking

Abstract thinking is a cognitive skill that allows us to understand complex ideas, make connections between seemingly unrelated concepts, and solve problems creatively. It is a way of thinking not tied to specific examples or situations. Instead, it involves thinking about the broader significance of ideas and information.

Abstract thinking differs from concrete thinking, which focuses on memorizing and recalling information and facts. Concrete thinking is vital for understanding the world, but abstract thinking is essential for problem-solving, creativity, and critical thinking.

Origins of Abstract Thinking

The origins of abstract thinking are partially clear, but it is believed to be a uniquely human ability. Some researchers believe that abstract thinking results from language and symbolic thought development. Others believe that it results from our ability to imagine and visualize concepts and ideas.

Abstract thinking is an essential skill that can be developed and strengthened with practice regardless of its origins. By learning to think abstractly, we can expand our understanding of the world and develop new solutions to complex problems.

Abstract thinking is a higher-order cognitive skill that allows us to think about concepts and ideas that are not physically present. We can improve our problem-solving, creativity, and critical thinking skills by developing our abstract thinking ability.

Importance of Abstract Thinking

Abstract thinking is a crucial skill that significantly impacts our daily lives. It allows us to understand complex concepts and think beyond what we see or touch. This section will discuss the benefits of abstract thinking in our daily lives and its role in problem-solving.

Benefits in Daily Life

Abstract thinking is essential for our personal growth and development. It enables us to think critically and creatively, which is necessary for making informed decisions. When we think abstractly, we can understand complex ideas and concepts, which helps us communicate more effectively with others.

Abstract thinking also helps us to be more adaptable and flexible in different situations. We can see things from different perspectives and find innovative solutions to problems. This skill is beneficial in today’s fast-paced world, where change is constant, and we need to adapt quickly.

Role in Problem Solving

Abstract thinking plays a crucial role in problem-solving. It allows us to approach problems from different angles and find creative solutions. When we can think abstractly, we can see the bigger picture and understand the underlying causes of a problem.

By using abstract thinking, we can also identify patterns and connections that may not be immediately apparent. This helps us to find solutions that are not only effective but also efficient. For example, a business owner who can think abstractly can identify the root cause of a problem and develop a solution that addresses it rather than just treating the symptoms.

Abstract thinking is a valuable skill with many benefits in our daily lives. It allows us to think critically and creatively, be more adaptable and flexible, and find innovative solutions to problems. By developing our abstract thinking skills, we can improve our personal and professional lives and positively impact the world around us.

Abstract Thinking Vs. Concrete Thinking

When it comes to thinking, we all have different approaches. Some of us tend to think more abstractly, while others tend to think more concretely. Abstract thinking and concrete thinking are two different styles of thought that can influence how we perceive and interact with the world around us.

Key Differences

The key difference between abstract and concrete thinking is the level of specificity involved in each style. Concrete thinking focuses on a situation’s immediate and tangible aspects, whereas abstract thinking is more concerned with the big picture and underlying concepts.

Concrete thinking is often associated with literal interpretations of information, while abstract thinking relates to symbolic and metaphorical interpretations. For example, if we describe a tree, someone who thinks concretely might describe its physical appearance and characteristics. In contrast, someone who thinks abstractly might explain its symbolic significance in nature.

The transition from Concrete to Abstract

While some people may naturally lean towards one style of thinking over the other, it is possible to transition from concrete to abstract thinking. This can be particularly useful in problem-solving and critical-thinking situations, where a more abstract approach may be needed to find a solution.

One way to make this transition is to focus on a situation’s underlying concepts and principles rather than just the immediate details. This can involve asking questions that explore the broader implications of a situation or looking for patterns and connections between seemingly unrelated pieces of information.

Abstract and concrete thinking are two different styles of thought that can influence how we perceive and interact with the world around us. While both styles have their strengths and weaknesses, transitioning between them can be valuable in many areas of life.

Development of Abstract Thinking

As we grow and learn, our ability to think abstractly develops. Age and education are two major factors that influence the development of abstract thinking.

Influence of Age

As we age, our ability to think abstractly improves. This is due to the development of our brain and cognitive abilities. According to Piaget’s theory of cognitive development , children progress through four stages of cognitive development, with the final stage being the formal operational stage. This stage is characterized by the ability to think abstractly and logically about hypothetical situations and concepts.

Role of Education

Education also plays a significant role in the development of abstract thinking. Through education, we are exposed to new ideas, concepts, and theories that challenge our existing knowledge and encourage us to think abstractly. Education also gives us the tools and skills to analyze and evaluate complex information and ideas.

In addition to traditional education, engaging in activities promoting abstract thinking can be beneficial. For example, participating in debates, solving puzzles, and playing strategy games can all help improve our abstract thinking skills.

The development of abstract thinking is a complex process influenced by age and education. By continually challenging ourselves to think abstractly and engaging in activities that promote abstract thinking, we can continue to improve our cognitive abilities and expand our knowledge and understanding of the world around us.

Challenges in Abstract Thinking

Abstract thinking can be a challenging cognitive process, especially for those not used to it. Here are some common misunderstandings and difficulties people may encounter when thinking abstractly.

Common Misunderstandings

One common misunderstanding about abstract thinking is that it is the same as creative thinking. While creativity can certainly involve abstract thinking, the two are not interchangeable. Abstract thinking consists of understanding and thinking about complex concepts not tied to concrete experiences, objects, people, or situations. Creative thinking, on the other hand, involves coming up with new and innovative ideas.

Another common misunderstanding is that abstract thinking is only helpful for people in certain fields, such as science or philosophy. Abstract thinking can benefit many different areas of life, from problem-solving at work to understanding complex social issues.

Overcoming Difficulties

One difficulty people may encounter when thinking abstractly is a lack of concrete examples or experiences to draw from. To overcome this, finding real-world examples of the concepts you are trying to understand can be helpful. For example, if you are trying to understand the concept of justice, you might look for examples of situations where justice was served or not served.

Another challenge people may encounter is focusing too much on details and needing more on the bigger picture. To overcome this, try to step back and look at the broader significance of the ideas and information you are working with. This can involve asking yourself questions like “What is the main point here?” or “How does this fit into the larger context?”

Abstract thinking can be a challenging but valuable cognitive process. By understanding common misunderstandings and overcoming difficulties, we can develop our ability to think abstractly and apply it in various aspects of our lives.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does abstract thinking differ from concrete thinking.

Abstract thinking is a type of thinking that involves the ability to think about concepts, ideas, and principles that are not necessarily tied to physical objects or experiences. Concrete thinking, on the other hand, is focused on the here and now, and is more concerned with the physical world and immediate experiences.

What are some examples of abstract thinking?

Examples of abstract thinking include the ability to understand complex ideas, to think creatively, to solve problems, to think critically, and to engage in philosophical discussions.

What is the significance of abstract thinking in psychiatry?

Abstract thinking is an important component of mental health and well-being. It allows individuals to think beyond the present moment and to consider different possibilities and outcomes. In psychiatry, the ability to engage in abstract thinking is often used as an indicator of cognitive functioning and overall mental health.

At what age does abstract thinking typically develop?

Abstract thinking typically develops during adolescence, around the age of 12 or 13. However, the ability to engage in abstract thinking can continue to develop throughout adulthood, with continued practice and exposure to new ideas and experiences.

What are the stages of abstract thought according to Piaget?

According to Piaget, there are four stages of abstract thought: the sensorimotor stage (birth to 2 years), the preoperational stage (2 to 7 years), the concrete operational stage (7 to 12 years), and the formal operational stage (12 years and up). During the formal operational stage, individuals are able to engage in abstract thinking and to think about hypothetical situations and possibilities.

What are some exercises to improve abstract thinking skills?

Some exercises that can help improve abstract thinking skills include engaging in philosophical discussions, solving puzzles and brain teasers, playing strategy games, and engaging in creative activities such as writing or painting. Additionally, exposing oneself to new ideas and experiences can help broaden one’s perspective and improve abstract thinking abilities.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Thinking Outside The Box: The Difference Between Concrete Vs. Abstract Thinking

Abstract thought is a defining feature of human cognition . Scholars from diverse fields — including psychologists, linguists, anthropologists, neuroscientists, and even philosophers — have contributed to the scientific discussion of how abstract ideas are acquired and used by the brain. Concrete thought is somewhat better understood, as it represents a more grounded form of thinking than what is typically found in abstract thought. Concrete thinkers focus on physical objects and the physical world, making their thinking process more immediately obvious and tied to the literal form. Both modes of thinking are useful for human cognition.

Distinguishing between concrete and abstract thoughts

Understanding the differences between these two types of thinking may help illustrate their unique contributions to human thought.

Concrete thinking

Concrete thinking is grounded in facts and operates in a literal domain , focusing on objective facets such as physical attributes (e.g., color and shape) and verifiable occurrences (e.g., chronological sequences). Concrete thinkers often rely on concrete objects and specific examples to solve problems and classify objects. It avoids extrapolations, categorizing information superficially and within rigid boundaries. Concrete thinking is chiefly concerned with detail gathering, excluding analyses of trends and exploration of potentialities.

Rumination , a cognitive process characterized by excessive or repetitive thoughts, including intrusive memories, that interfere with daily life, might use concrete thinking to contemplate complex issues. These thoughts might include questions like "What happened in this situation?" and "What steps can I take to address the problem?" Although these questions address more than basic attributes, they are anchored in objectively definable detail.

Abstract thinking

It synthesizes and integrates information into broader contexts, forming the bedrock of creativity, critical analysis, and problem-solving. This thinking style is a vital skill for those who exercise creativity in fields like theoretical math or philosophical concepts. This allows individuals to transcend surface-level understanding. Abstract thinking is indispensable for grappling with intangible concepts, including emotions, and often involves contemplating hypothetical scenarios.

Rumination, explored above, also has an abstract component . Abstract ruminative thoughts may include questions like "Why do I always feel so unhappy?" or "Why didn’t I handle this better?" These queries pivot away from objective facts and explore concepts that may be interpreted in multiple ways.

When is each type of thinking most useful?

Several factors determine whether concrete or abstract thinking is most appropriate, but in practice, most deliberate thought processes benefit from the interplay between the two modes. Abstract thinking skills, including abstract reasoning skills, are crucial in understanding complex concepts and integrating existing knowledge. For instance, effective problem-solving necessitates the initial definition of its core features (concrete thinking) and subsequent high-level analysis (abstract thinking).

Psychologists and sociologists have scrutinized the relationship between abstract and concrete thought, often using construal learning theory (CLT) as a framework. CLT identifies how psychological distance influences a person’s choice between abstract and concrete thinking. “Psychological distance” can be measured in various ways:

- Temporal distance: The amount of time between a person and their subject of contemplation.

- Spatial distance: The physical separation between a person and their subject of contemplation.

- Social distance: The emotional distance between individuals.

- Hypothetical distance: An individual’s assessment of the likelihood of their subject of contemplation occurring.

CLT suggests that individuals tend toward abstract thinking when they perceive substantial psychological distance and favor concrete thinking when that distance diminishes. This indicates that more abstract thinkers are likely to engage in abstract reasoning when dealing with subjects that are not immediately present or concrete. For example, a person planning to attend a family reunion next year (significant temporal distance) is more likely to think of big-picture, abstract elements of their plan — perhaps their excitement about attending the event. But as the event approaches, their thoughts shift toward concrete details, such as what they’ll wear to the party.

CLT can be used to assess a person's propensity for risk-taking behavior. Evidence suggests that individuals with a high construal level (greater psychological distance) employ more abstract thought processes and are more likely to engage in risky behaviors. Conversely, individuals with a low construal level (lesser psychological distance) display greater risk aversion as they are more aware of objective risk factors.

How do concrete and abstract thinking develop?

It’s worth noting that babies are not born with the ability to think abstractly. Jean Piaget’s stages of cognitive development illustrate how a child’s cognition develops over time. This cognitive development is crucial in the transition from a concrete thinker to an abstract thinker.

- Sensorimotor stage (birth to age two): Babies engage primarily with their sensory world, absorbing concrete information like a sponge without making abstract connections. This stage is fundamental in developing motor skills and concrete thinking skills.

- Preoperational stage (ages two to seven): Young children begin to develop abstract thinking, engaging in imaginary play, comprehending the rudiments of symbolism, and understanding someone else’s point. They start to understand figurative language and can interpret facial expressions, moving towards more abstract thinking abilities.

- Concrete operational stage (ages seven to 11): Children can understand that other people may experience the world differently than they do. They can recognize abstract concepts but remain tethered to empirical experiences. This stage involves processing theoretical concepts and developing concrete thinking skills to solve problems.

- Formal operational stage (age 11 to adulthood): Abstract thought matures as individuals use concrete information to derive abstract conclusions. Individuals expand their ability to empathize and discern patterns among abstract concepts. This stage is where strong abstract thinking skills are developed, allowing individuals to grapple with more complex concepts and engage in theoretical math and philosophical concepts, and solve abstract riddles such as brain teasers. This stage equips individuals with the capacity to analyze hypothetical scenarios and address "what-if" questions.

Key insights from Piaget's theory underscore the development of abstract thinking, where concrete thinking lays the foundation. This progression from being a concrete thinker to an abstract thinker is a vital aspect of cognitive development. That is, concrete thought is a prerequisite for abstract thought because objective facts must be defined before they can be analyzed. Proficiency in abstract thought unfolds gradually over many years.

Assessing the merits of abstract and concrete thinking

Abstract thinking allows humans to create art, reach conclusions through debate, and predict what the future may hold. It involves a thinking process that is less immediately obvious than concrete thinking, often requiring the individual to consider other meanings and exercise creativity. Because abstract thought empowers higher cognitive functions, it may seem that it is a preferable mode of cognition over concrete thought.

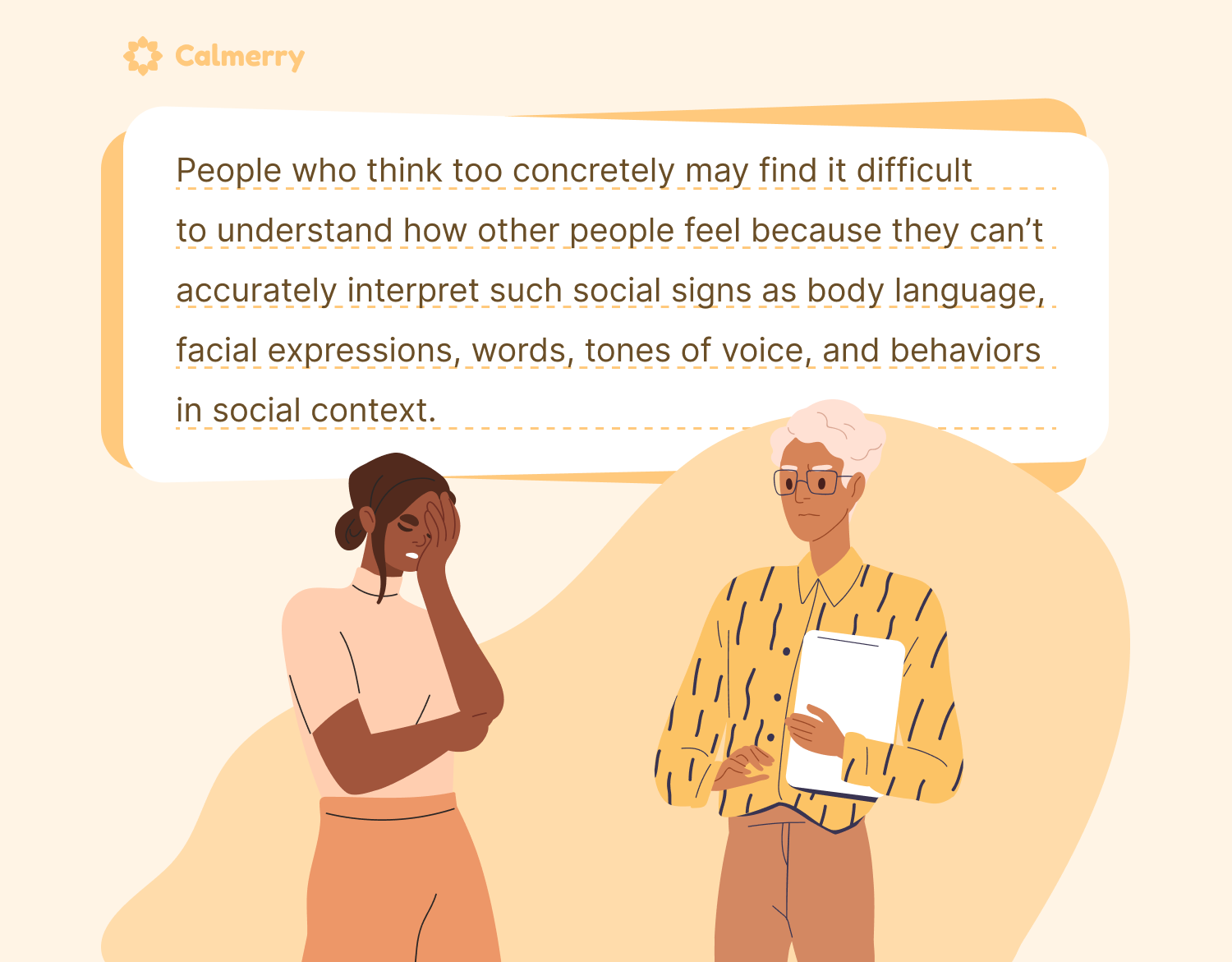

However, abstract thinking is not without its limitations. An unbalanced reliance on abstract rumination can lead to mental health concerns , such as depression. In individuals with mental health conditions like autism spectrum disorder or who have had a traumatic brain injury, the balance between abstract and concrete thinking can be particularly crucial, and reading body language and understanding figurative expressions may be difficult for some individuals. Conversely, a conscious preference for concrete thinking can potentially mitigate negative mental health . Both concrete and abstract thinking are necessary for human cognition. For instance, abstract thinkers may engage in the active practice of new ideas, while concrete thinkers might focus on classifying objects and dealing with the literal form of information. While abstract thought may be associated with higher-order cognitive processes, those processes are built upon the foundation of concrete thinking.

Can therapy help manage cognitive and abstract thinking?

If you’re interested in recognizing and adapting your cognitive tendencies, a therapist can help. Therapists are trained in a variety of evidence-based techniques, including cognitive behavioral therapy , to analyze your mental processes and guide you toward meaningful conclusions about your thought patterns. This therapy can be particularly helpful for those struggling with difficulty relating to others due to their thinking style, whether they are more comfortable with abstract thinking vs concrete thinking.

You may wish to consider online therapy, which is available for individuals to avail the care of a skilled mental health professional. Working with a therapist online removes some common barriers to therapy, like having to commute to an office. Removing geographical constraints allows you to choose a therapist outside of your local area, which may be especially helpful to those who live in regions with limited mental health professionals. Online therapists have the same training and credentials as traditional therapists, and evidence indicates that therapy delivered remotely is just as effective as in-person therapy.

What is an example of concrete thinking?

Concrete thinking is literal. It focuses on physical attributes and things that can be verified with facts. Concrete thinking is more rigid and is chiefly concerned with gathering details or information. Someone who is a concrete thinker might take things very literally. For example, if you ask them to run to the store, they may think you want them to actually run to the store.

What is an example of abstract thinking?

An abstract thinking style involves processing theoretical concepts. It is more flexible and links causality, figurative language, themes, and intangible concepts and is the basis of things like problem-solving, creativity, and critical analysis. It often involves contemplating hypothetical scenarios, intangible concepts, and emotions. An excellent example of abstract thinking is making predictions. Any time someone assesses available information and processes it to determine what might happen next, they use abstract thinking.

Can you be both a concrete and abstract thinker?

Yes, people can be both concrete and abstract thinkers. According to construal level theory (CLT), psychological distance can affect whether a person uses concrete or abstract thinking. This theory measures psychological distance in four ways: temporal distance, or the amount of time between the person and the subject they’re thinking about; spatial distance, or the physical distance between the person and what they’re thinking about; spatial distance, or the physical separation between the person and what they’re thinking; and hypothetical distance, of the person’s assessment of the likelihood of what they’re thinking about occurring.

CLT suggests that people tend to think more abstractly when they perceive a larger psychological distance and more concretely when they perceive less psychological distance. For example, someone who has a big vacation planned next year may think about how excited they are or a simple list of the things they hope to see, but as the trip approaches, they will likely focus on more concrete details, like making a list of what they need to pack, making sure they have their travel documents in order, and double-checking their itineraries.

Am I an abstract or concrete thinker?

Gaining abstract thinking is part of cognitive development; young children have concrete thinking first and develop abstract thinking as they mature. Some people may be prone to thinking more abstractly or concretely, but most are capable of both. People with good abstract reasoning skills may be better at imagining things that are not physically present, understanding complex concepts, and deciphering body language, and they may be more talented at creative endeavors or theoretical math or science concepts. On the other hand, concrete thinkers may be more likely to stick to rigid routines. They may think in more black-and-white terms and have difficulty considering gray areas or expanding their existing knowledge.

What are abstract thinkers good at?

People with strong abstract thinking skills can excel in many areas, including graphic design, landscape architecture, engineering, psychology, and psychology. They can also make excellent detectives, criminal investigators, and scientists.

An example of concrete thinking might be someone who sits down and lists items they need to accomplish in a day. In contrast, an abstract thinker might make the same kind of list, but they may rank it according to the order of importance or organize it according to the most efficient way to get all the tasks done.

What is a concrete thinking example for a student?

Specific examples of when students may use concrete thinking skills are when they organize their schedules or make a list of assignments they need to complete.

What is an example of a concrete task?

Many tasks might be considered concrete. For example, doing the dishes is a concrete task; they’re either clean or not. Other examples might be making the bed, folding laundry, washing the car, or vacuuming the carpet.

Is concrete thinking good or bad?

Concrete thinking isn’t necessarily good or bad; everyone needs to be able to think concretely at times. It can become a problem when people cannot switch out of concrete thinking in the physical world. Having abstract thinking abilities can help with problem-solving, creativity, and analysis, all of which can influence how someone interacts with the world.

What is an example of concrete thinking in mental health?

Concrete thinking can be considered a feature of schizophrenia . People with this condition can be said to have an abstraction deficit or the inability to distinguish between symbolic, abstract ideas and the concrete. People with schizophrenia may not be able to deal with their experiences conceptually and cannot perceive objects as belonging to a class or category. Another example is autism spectrum disorder; people with this condition may have a very concrete way of thinking.

- What Is Insecurity? Exploring The Definition, Symptoms, And Treatments Medically reviewed by Paige Henry , LMSW, J.D.

- How To Better Understand Yourself Via Character Survey Medically reviewed by Majesty Purvis , LCMHC

- Self Esteem

- Relationships and Relations

- Sign up and Get Listed

Be found at the exact moment they are searching. Sign up and Get Listed

- For Professionals

- Worksheets/Resources

- Get Help

- Learn

- For Professionals

- About

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Marriage Counselor

- Find a Child Counselor

- Find a Support Group

- Find a Psychologist

- If You Are in Crisis

- Self-Esteem

- Sex Addiction

- Relationships

- Child and Adolescent Issues

- Eating Disorders

- How to Find the Right Therapist

- Explore Therapy

- Issues Treated

- Modes of Therapy

- Types of Therapy

- Famous Psychologists

- Psychotropic Medication

- What Is Therapy?

- How to Help a Loved One

- How Much Does Therapy Cost?

- How to Become a Therapist

- Signs of Healthy Therapy

- Warning Signs in Therapy

- The GoodTherapy Blog

- PsychPedia A-Z

- Dear GoodTherapy

- Share Your Story

- Therapy News

- Marketing Your Therapy Website

- Private Practice Checklist

- Private Practice Business Plan

- Practice Management Software for Therapists

- Rules and Ethics of Online Therapy for Therapists

- CE Courses for Therapists

- HIPAA Basics for Therapists

- How to Send Appointment Reminders that Work

- More Professional Resources

- List Your Practice

- List a Treatment Center

- Earn CE Credit Hours

- Student Membership

- Online Continuing Education

- Marketing Webinars

- GoodTherapy’s Vision

- Partner or Advertise

- GoodTherapy Blog >

- PsychPedia >

Abstract Thinking

What Is Abstract Thinking?

A variety of everyday behaviors constitute abstract thinking. These include:

- Using metaphors and analogies

- Understanding relationships between verbal and nonverbal ideas

- Spatial reasoning and mentally manipulating and rotating objects

- Complex reasoning, such as using critical thinking, the scientific method , and other approaches to reasoning through problems

Abstract thinking makes it possible for people to exercise creativity. Creativity , in turn, is a useful survival mechanism—it allows us to develop tools and new ideas that improve the quality of human life.

Abstract Thinking in Psychology: How Does It Develop?

Developmental psychologist Jean Piaget argued that children develop abstract reasoning skills as part of their last stage of development, known as the formal operational stage. This stage occurs between the ages of 11 and 16. However, the beginnings of abstract reasoning may be present earlier, and gifted children frequently develop abstract reasoning at an earlier age.

Some psychologists have argued the development of abstract reasoning is not a natural developmental stage. Rather, it is the product of culture , experience, and teaching.

Children’s stories frequently operate on two levels of reasoning: abstract and concrete . The concrete story, for example, might tell of a princess who married Prince Charming, while the abstract version of the story tells of the importance of virtue and working hard. While young children are often incapable of complex abstract reasoning, they frequently recognize the underlying lessons of these stories, indicating some degree of abstract reasoning skills.

Abstract vs. Concrete Thinking

Concrete thinking is the opposite of abstract thinking. While abstract thinking is centered around ideas, symbols, and the intangible, concrete thinking focuses on what can be perceived through the five senses: smell, sight, sound, taste, and touch. The vast majority of people use a combination of concrete and abstract thinking to function in daily life, although some people may favor one mode over the other.

A study published in Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience found abstract thinking was tied to parts of the brain occupied with vision. Concrete thinking, on the other hand. activated parts of the brain that focus on actions taken to complete a goal.

Other research found that abstract thinkers are more likely than concrete thinkers to take risks. This may be partly due to the idea that concrete thinkers, more concerned with “how” to perform an action rather than “why,” might be dissuaded from starting a risky task because they’re more focused on the practical effort involved with the task, while the abstract thinker might be more occupied with considering the pros and cons of the risk.

Abstract Reasoning and Intelligence

Abstract reasoning is a component of most intelligence tests. Skills such as mental object rotation, mathematics, higher-level language usage, and the application of concepts to particulars all require abstract reasoning skills. Abstract thinking skills are associated with high levels of intelligence. And since abstract thinking is associated with creativity, it may often be found in gifted individuals who are innovators.

Learning disabilities can inhibit the development of abstract reasoning skills. People with severe intellectual disabilities may never develop abstract reasoning skills and may take abstract concepts such as metaphors and analogies literally. Since abstract reasoning is closely connected to the ability to solve problems, individuals with severely inhibited abstract thinking ability may need assistance with day-to-day life.

Mental Health and Abstract Thinking

Some mental health conditions can negatively impact an individual’s ability to think abstractly. For example, schizophrenia has been found to impair abstract thinking ability in those it affects. Some other conditions that may impair abstract thinking include:

- Learning disabilities

- Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

Some research has connected the ability to think abstractly with a stronger sense of self-control. This means that when people were given a reason to do or not to do something, it was easier for them to adhere to that rule than if they were simply told how to follow the rule.

A study published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology found an interesting link between power and abstract thought. A person’s conception of how much power they have may more strongly influence their behavior than the actual amount of power they have. Because of this, researchers posited that an increased capacity for abstract thought would increase an individual’s sense of personal power, creating a positive feedback loop in which their beliefs influence their behavior, and their behavior shapes their personal outcomes.

Abstract Thinking Exercises

In many cases, it is possible to improve your abstract reasoning skills. Working on your abstract reasoning skills may help you improve your ability to solve problems, understand and communicate complex ideas, and enjoy creative pursuits.

One way to exercise your abstract reasoning skills is to practice solving puzzles, optical illusions, and other “brain teasers.” These thinking exercises allow individuals to practice viewing information from different perspectives and angles. As they may help open a person’s mind to different possibilities through the problem-solving process, puzzles can be an engaging way for both young people and adults to get better at abstract thinking.

Strengthening improvisation skills may also help increase an individual’s creativity and abstract thinking skills. Tasks that require the person to rely mostly on their imagination may help strengthen their ability to think abstractly over time.

References:

- Culpin, B. (2018, October 16). ‘Abstract thought’ – How is it significant and how does it define the basis for modern humanity? Retrieved from https://medium.com/@bc805/abstract-thought-how-is-it-significant-and-how-does-it-define-the-basis-for-modern-humanity-a98a5b92fb9f

- Dementia: What are the common signs? (2003, March 1). American Family Physician, 67 (5), 1,051-1,052. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/afp/2003/0301/p1051.html

- De Vries, E. (2014). Improvisation as a tool to develop creativity mini-workshop divergent thinking. IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) Proceedings . doi: 10.1109/FIE.2014.7044132

- Gilead, M., Liberman, N., & Maril, A. (2013, May 18). From mind to matter: Neural correlates of abstract and concrete mindsets. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9 (5), 638-645. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst031

- Harwood, R., Miller, S. A., & Vasta, R. (2008). Child psychology: Development in a changing society. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Lermer, E., Streicher, B., Sachs, R., Raue, M., & Frey, D. (2016, August 26). The effect of abstract and concrete thinking on risk-taking behavior in women and men. SAGE Open, 6 (3). Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2158244016666127

- Logsdon, A. (2019, June 17). Why children need to use abstract reasoning in school. Retrieved from https://www.verywellfamily.com/what-is-abstract-reasoning-2162162

- Marintcheva, B. (2013, May 6). Looking for the forest and the trees : Exercises to provoke abstract thinking. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 14 (1), 127-128. doi: 10.1128/jmbe.v14i1.535

- Minshew, N., Meyer, J., & Goldstein, G. (2002). Abstract reasoning in autism: A dissociation between concept formation and concept identification. Neuropsychology, 16 (3), 327-334. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.16.3.327

- Oh, J., Chun, J., Lee, J. S., & Kim, J. (2014). Relationship between abstract thinking and eye gaze pattern in patients with schizophrenia. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 10 (13). doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-10-13

- Renzulli, J. S. (2003). The international handbook on innovation . Elsevier

- Scherzer, B. P., Charbonneau, S., Solomon, C. R., & Lepore, F. (1993). Abstract thinking following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 7 (5), 411-423. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8401483

- Smith, P. K., Wigboldus, D., & Dijksterhuis, A. (2008). Abstract thinking increases one’s sense of power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44 (2), 378-385. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2006.12.005

- Ylvisaker, M., Hibbard, M., & Feeney, T. (n.d.). Tutorial: Concrete vs. abstract thinking. Retrieved from http://www.projectlearnet.org/tutorials/concrete_vs_abstract_thinking.html

Last Updated: 07-30-2019

Please fill out all required fields to submit your message.

Invalid Email Address.

Please confirm that you are human.

- 28 comments

Leave a Comment

I recently took a psych test for a police department. I was told I failed horribly. When. Contacted the physician that administered the test. He told me I did not do well with abstract thinking. How is that? I am very intelligent, served as a soldier in the US Army for 14 years. Been to combat and was never injured.

Vince, Most professions including most MOS fields involved in soldiering don’t require much abstract thought. They are typically operating in the concrete world with specific tangible and practical applications with boots on the ground. Most police activities deal with policy and procedures which are concrete in form. The application of these must seen through the abstract variables of people and personalities. Many people have a limited ability for abstraction in thought process, that doesn’t mean that they are not intelligent. It just means that their thinking is external and associated with more about what is seen and known in the physical representations in actual form rather than internally as to the function of origin and meaning behind the actual form. One who is a concrete thinker may look at a a painting as a picture of a house. The abstract thinker may think of the meaning behind a place of rest and peace and view warmth of the colors, light, and shadows, as an inter-play with the emotions and vision of the artist in representation of a place of heart where meals are shared and love is fostered, called home.

So in other words, the Police Department missed out on a potentially great applicant because he was a concrete thinker rather and was unable to pass the departmental psychometric test. How’s that for an abstract comment? Let me ask as a concrete thinker, is there any meta analysis done on the workplace success of concrete vs abstract thinkers?

Your answer explains exactly why you failed. Somehow you figured your past job was evidence for your ability for abstract thought. Well sorry my friend you just don’t get it. Also, the Army stresses concrete thought and discourages abstract and higher order thinking. If you wanted that, should have joined the Air Force.

I don’t know much haha but from what I’ve been researching I believe you aren’t stupid in a sense but just not as strong with the abstract part of things. You’re intelligence could be fine but practicing your mathematics and using your ‘minds eye’ to see past what’s in front of you is the real test. Practice some spatial reasoning as well. I love sciences and mathematics it’s really stimulates my mind and I always think way outside of what anyone else is thinking so it’s hard to even find common ground sometimes but you’ll get there. You aren’t any less intelligent because your skills aren’t as developed you just have knowledge in a different area.

When you think about it, all thought is abstract thought. It all comes from experience gained, from birth onwards. The brain is just an engine of sorts. It doesn’t know anything at birth. I discount here, the minimal learning in utero.

What percentage of 16 year-old people are capable of abstract thinking?

This stuff is very interesting to me

I believe that stories that use anxiety to keep the reader engrossed are anti-abstract thought.

Would a 3 year old trying to find meaning in what a adult said be considered abstract thinking ?

Yes, to some level (of 3 yrs. old) it’s a form of abstract inquiry though it may not be as abstract as if it were asked by an adult.

I remember almost everything as a child an questioning god was one of them before grade school it made no scentes to me the things people would say I new I was different An no one could answer my questions that only made me more curious I was definitely odd I felt separate from people because I view things different in my head but adapted to others but kept my way of thinking because it felt right to me if I could paint a picture we would be an atom on an evolutionary scale

What are non-verbal ideas? Abstract thoughts can be verbalized or not, so I don’t understand the comment “understanding the relationship between verbal and non-verbal ideas.

Non-verbal ideas, to me, means symbols.

Ah yes. and those are neural networks from our experience.

Telepathy abstract means of communication I guess!

I heard people with schizophrenia have trouble with abstract thought. I had an early onset, been on medication for 10 years (all different antispychotics, anti-anxiety, and now mood stablizer), now I’m in my mid 20s and I can’t relate to anyone. How can I improve my thoughts? I take everything so literal and can’t flip an object in my head. When I took a career test in high school, I bombed every section. I will never be sucessful @ anything. Cant even drive. When I do flip objects in my head, I’m deeply psychotic and can’t control it. Please no negative comments like “your stupid”. I never did drugs and keep getting psychotic breaks. If you dont know what they are, look up “what is a psychotic break from reality”. Thanks.

You say you can’t relate to anyone & are bad at abstract thought but you just communicated beautifully when describing your situation, triggering empathy in others (me), both of which are essential pre-requisits for forming relationships. Do not give up hope. B:)

Barbara, thank you. I need hope, and I needed to hear that.

Hi Claudia. My heart goes out to you. My brother is currently suffering from something like a psychotic break, and it’s really hard. I hope you are finding the support you need and piecing things together. Everyone has gifts, and often people see them after they’ve dug themselves out of something dark and really challenging. I’m not sure if this is helpful given where you are, but the book that most helped me get control of my thoughts is Bryon Kate’s “Loving What Is.” It starts with interrupting the thought with curiosity and simply asking, “Is it true?” Followed by three other simple questions. Eventually the process asks you to look at things from other perspectives, and sounds like that might be hard for you right now. You can look at her website thework.com. Just start with the four questions (not the whole worksheet) and see how that feels. Hang in there and take care of yourself – that’s your most important job right now. Sending you hope. Warmly, Beth

so that means if you haven’t been using much of a critical thinking over the last yeara, there’s a big possibility that you’ll fail in a an abstract reasoning skill test.

first im an aeronautical engineer who served in the british army and im autistic.And all you neurotypicals obviously dont have a clue what your talking about.Soldiers have to use abstract thinking in combat situations particularly those of rank.As an engineer i have to use concrete and abstract thinking can yuo fully visualise how a mechanical component would work in your head. Oh and this empathy you are all so proud of being capable of is you projecting yourself on that person and clapping yuorselves on the back because you can relate to his/her situation. Unless yuor telepathic or have experienced every variable tht has had an effect on that person shaping their perceptions etc you cant.

Hey well said bro- I’m studying my Research Masters degree with my field of research being investigating just how dangerously over-rated Empathy is in Western moral reasoning. Just check out Friedrich Nietzsche’s thoughts on Compassion if you think I’m full of crap (A very good indicator of your Slave Moralty and Herd Conformity systems at work).

I have both abstract and concrete thinking, but the creativity abstract thinking presents is limited to certain subject areas. I am a verbal and a visual thinker. I also have this thought form that feels like the brain is moving, if you know the term for this please tell me.

All of these involve visuals in the imagination which would be described as Concrete. Using metaphors and analogies (using words to describe visuals of water when explaining electricity) Spatial reasoning and mentally manipulating and rotating objects (sorting out a collexion of items in front of the self and mentally picturing them sorted inside a closet). Complex reasoning, such as using critical thinking, the scientific method, and other approaches to reasoning through problems (geometry for matters of physics, logic symbols visually in place of words mentally, turning a method into an animation in the imagination) Perhaps I’m misunderstanding something. But if using mental imagery = concrete thinking, how is abstract thinking connected to the occipital lobe if it is supposed to help you understand the semiotics of a problem which is typically the function of the temporal lobe? Thanks.

I am a high school dropout that ranked in the 99th percentile nationally in abstract reasoning on a freshman aptitude test, also 97th in mechanical reasoning and 95th in spatial relations. Furthermore, other than verbal reasoning, I ranked below average in every other category. Three years later I dropped out due to crippling anxiety owing to the accumulation of misunderstanding between me and my peers, I believe I have a lot to offer the world but I have hidden myself away and find myself at middle age with no friends or prospects other than the stresses of manual and skilled labor environments. I understand science through books and lay communication better than the communicators or experts in some regards because of how I build my visual model of understanding but this universe exists inside my head alone and all of that potential will be lost when my likely to be relatively short existence inevitably comes to an end. I continue to leave cries for help on the internet like this but no one seems to hear me and all I want is purpose and to realize at least some of what I have come to see as a rare gift.

It is not actually unusual for people with your gifts to have problems relating to their high school peers and have a story like yours. Malcolm Gladwell looked into it and the most nobel prizes were actual for people with 125 IQ for pricely the reasons cited. So you are in fact one of crowd here. I think what you need is in fact a good therapist who can guide you to your best life. And then a way to let your light shine, platitudes I know but they are there for a reason. It is most likely you’ll need to find a partner to get these idea to market, a Jobs to your Wozniak if you will. This too is exceptionally normal and a well-trod path. So rather than bemoan how much of a weirdo you are, understand that in fact you are almost a cliche. Life is not high school and we have the internet. So here is my action plan for you: 1.) Get a therapist. (Shop around. Be sure you are comfortable with them and that they are intelligent to understand what you are talking about.) 2.) With the facility of the therapist, find like-minded groups that would welcome your expertise. The therapist will help you relate to them in. healthy manner and sort through who is in your interest. 3.) Once you have a a healthy group, find someone to partner your projects with. Again therapist can sound these people out. Listen for red flags etc. since you feel kinda fragile. I should note that if you dropped out of high school for social reasons you might need anxiety meds. If you did so because you academically couldn’t get your act together despite being smart, you might have ADHD or another learning disability and should get screened. Therapists are not good at catching this. But they are with anxiety and depression. Listen them.

By commenting you acknowledge acceptance of GoodTherapy.org's Terms and Conditions of Use .

* Indicates required field.

- Concrete Thinking

- Intellectual Disability

- Learning Difficulties

Notice to users

Abstract Thinking

Abstract thinking is a fundamental cognitive process that allows us to explore and understand concepts beyond the realm of concrete reality. It involves the ability to think conceptually, creatively, and symbolically, enabling us to grasp complex ideas, solve problems, and engage in higher-order thinking.

Abstract thinking can be defined as the mental ability to conceptualize and understand concepts that are not directly tied to physical objects or concrete events. Unlike concrete thinking that focuses on specific, tangible things, abstract thinking allows us to derive meaning, interpret symbols, make inferences, recognize patterns, and engage in metaphorical and symbolic reasoning. It is a process that goes beyond the surface-level understanding and helps us navigate the complexities of the world.

- Interpreting a poem’s underlying meaning rather than focusing solely on its literal words.

- Understanding the concept of justice and evaluating its application in various scenarios.

- Recognizing and appreciating symbolism in art, literature, and music.

- Arriving at a logical conclusion by examining multiple perspectives and possibilities.

- Using analogies to explain complex ideas or relationships.

- Developing and testing hypotheses in scientific experiments.

The Importance of Abstract Thinking

Abstract thinking plays a crucial role in various aspects of our lives. It is not only an essential cognitive skill but also a tool for problem-solving, decision-making, and creativity. Here are a few key areas where abstract thinking is particularly valuable:

- Education: Abstract thinking helps students engage in critical thinking, analyze information, and delve deeper into subjects beyond surface-level knowledge. It promotes a deeper understanding of complex ideas and encourages independent thinking.

- Problem Solving: When faced with challenges, abstract thinking allows us to generate innovative solutions by exploring unconventional possibilities and finding connections between seemingly unrelated concepts. It helps us think “outside the box” and discover new perspectives.

- Creativity: Abstract thinking fuels creativity by allowing us to envision and create something new. Artists, musicians, writers, and inventors rely heavily on abstract thinking to generate original ideas, visualize concepts, and communicate abstract emotions or experiences.

- Communication: Abstract thinking enhances effective communication by enabling us to convey complex ideas using metaphors, analogies, and symbolic language. It helps us express ourselves more vividly and engage listeners or readers on a deeper, emotional level.

- Decision-Making: Abstract thinking aids in decision-making, as it helps us consider the potential consequences, evaluate different options, and anticipate long-term effects. By thinking abstractly, we can make informed choices and weigh the pros and cons of each alternative.

Tips for Enhancing Abstract Thinking

While abstract thinking comes naturally to some individuals, it can also be developed and strengthened through practice. Here are a few tips to enhance your abstract thinking abilities:

- Embrace Curiosity: Cultivate a curious mindset and ask questions that encourage deeper thinking.

- Engage in Creative Activities: Explore art, music, writing, or any activity that encourages abstract thinking and self-expression.

- Read Widely: Engage with diverse literature and expose yourself to different perspectives, ideologies, and worldviews.

- Practice Symbolic Reasoning: Analyze symbols, metaphors, and allegories in various forms of media to develop your ability to interpret abstract representations.

- Investigate Opposing Views: Challenge your own beliefs by seeking out and critically evaluating opposing viewpoints.

- Play Brain-stimulating Games: Engage in puzzles, riddles, and strategy games that require abstract thinking and problem-solving.

Abstract thinking is a remarkable cognitive ability that allows us to explore the world beyond its concrete boundaries . By unlocking the power of imagination, symbolism, and conceptualization, abstract thinking enriches our lives and enables us to navigate the complexities of our existence. Enhancing our abstract thinking skills not only empowers us intellectually but also enhances our creativity, problem-solving abilities, and decision-making skills.

Need help? Call us at (833) 966-4233

- Anxiety therapy

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

- Depression counseling

- Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)

- Grief & loss counseling

- Relational therapy

- View all specialties & approaches

Thriveworks has earned 65+ awards (and counting) for our leading therapy and psychiatry services.

We’re in network with most major insurances – accepting 585+ insurance plans, covering 190 million people nationwide.

Thriveworks offers flexible and convenient therapy services, available both online and in-person nationwide, with psychiatry services accessible in select states.

Find the right provider for you, based on your specific needs and preferences, all online.

If you need assistance booking, we’ll be happy to help — our support team is available 7 days a week.

Discover more

What is abstract thinking? How it works & more

Our clinical and medical experts , ranging from licensed therapists and counselors to psychiatric nurse practitioners, author our content, in partnership with our editorial team. In addition, we only use authoritative, trusted, and current sources. This ensures we provide valuable resources to our readers. Read our editorial policy for more information.

Thriveworks was established in 2008, with the ultimate goal of helping people live happy and successful lives. We are clinician-founded and clinician-led. In addition to providing exceptional clinical care and customer service, we accomplish our mission by offering important information about mental health and self-improvement.

We are dedicated to providing you with valuable resources that educate and empower you to live better. First, our content is authored by the experts — our editorial team co-writes our content with mental health professionals at Thriveworks, including therapists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, and more.

We also enforce a tiered review process in which at least three individuals — two or more being licensed clinical experts — review, edit, and approve each piece of content before it is published. Finally, we frequently update old content to reflect the most up-to-date information.

- Abstract thinking, essential in various aspects of life, enables us to tackle problems ranging from calculus to navigating busy highways, showcasing its broad applicability.

- Applied on a daily basis, abstract thinking is a universal skill, transcending professions and daily routines, highlighting its pervasive nature.

- Abstract thinking involves thought processes that deviate from everyday rhythms, habits, and routines, providing a framework for simple to complex problem-solving scenarios.

- Delving into the concept of abstract thinking, it encompasses the ability to engage in unconventional thought processes, fostering creativity and strategic thinking.

From completing calculus problems to enabling us to strategize to successfully navigating a busy highway, abstract thinking allows us to accomplish a lot. Abstract thinking is applied daily, no matter what your profession or daily routines and habits are.

But what exactly is abstract thinking? And how can it be used? Learn more about abstract thinking below, including examples and comparisons between abstract and concrete thoughts.

What Is Meant By “Abstract Thinking?”

Abstract thinking typically refers to thinking and thought processes that often diverge from the ordinary rhythms, habits , and routines of daily life. Abstract thinking allows us to engage in simple to complex problem-solving.

Abstract thinking can be used to make decisions in split seconds or even ones that take days to consider. This form of thinking involves:

- Predictions

- Prior knowledge

- Past experiences

Often, abstract thinking patterns are not rooted in tangible, visible things but are rooted in concepts.

What Is an Example of Abstract Thinking?

A simple example of abstract thinking is solving a math problem; you might look at the problem and begin to use prior knowledge and logic to strategize on how to solve the problem before you begin.

A more psychologically-rooted example of abstract thinking can include character strengths, for example, such as wisdom and strength. In order to be able to define, discuss, and recognize wisdom and strength as concepts, you must first be able to think abstractly as to what they are, for you cannot see them physically or tangibly as items.

Hello, we're here to help you

We provide award-winning mental health services nationwide, with flexible scheduling & insurance coverage. Start your journey this week.

or call (833) 966-4233

What Are the 4 Stages of Abstract Thinking?

Abstract thinking and thought patterns tend to follow the four stages below:

- Non-objective fragmentation (birth months) : This stage is characterized by the developmental task of the infant building their understanding of the world through the use of their senses and being able to identify objects.

- Deconstruction ( 2-6 months ) : As children in this stage continue to develop relationships with objects and their senses, they can begin to understand routines and cause-and-effect patterns.

- Two-dimensionalization (6-12 months) : This is an exciting stage, as object permanence begins to develop; that is, being able to understand the abstract concept that an object can still exist even when you can’t physically see it.

- Non-figurative (12-18 months) : As sensorimotor and object permanence continue to develop, children begin to understand and develop memories for abstract concepts and ideas.

These four stages are based on the four stages of development posited by the developmental psychologist, Piaget . The four stages described above are developmental experiences that Piaget discovered that all children go through in their journey toward beginning to develop abstract thinking.

Though the four stages tend to end at approximately 18 months, as you can guess, the development of abstract concepts and thought processes is a lifelong process and continues to develop well past 18 months; the start of this secondary process occurs at 18 months. The stages above are described as the “sensorimotor stage” of development.

What Are Abstract Thinkers Good at?

Abstract thinkers tend to be very well-adjusted and well-adapted at handling difficult, unpredictable, and complex situations. They are often good at bringing original ideas to the table and this enables them to effectively solve complex problems as they can think critically and creatively , using flexible thought processes and patterns of thinking that are abstract, allowing them to be generative in their thinking.

Abstract thinkers are also great at context; they can typically use this generative way of thinking to make more informed decisions.

How Can You Tell if Someone Is an Abstract Thinker?

One of the best ways that you can tell if someone is an abstract thinker is to watch or have them describe ways that they solve problems. If they typically solve problems quickly and with few options or solutions, they are not typically an abstract thinker.

Abstract thinkers tend to involve many different types of cognitive inputs from various sources (past knowledge/experiences, current life experience, knowledge of certain concepts, etc.) to formulate many different solutions. Abstract thinkers are generative and typically offer a more structured, thorough thought process and multiple different solutions to one problem instead of formulating/focusing on one solution only.

What Does Abstract vs Concrete Thinking Mean?

The term “ abstract vs. concrete thinking ” simply refers to the description of two different philosophies or schools of thought. In other words, it identifies that there are two separate, distinct thought processes and ways of thinking that humans use to problem-solve and navigate their world and environment daily.

Humans will tend to demonstrate one type of problem-solving over the other due to predispositions, learned behaviors, past experiences, current environmental influences, and the type of problem or challenge they face.

What Is the Difference Between Abstract Thinking and Concrete Thinking?

There are many differences between abstract and concrete thinking styles . One of the most recognizable differences is that abstract thinking patterns involve uses of logic, and non-tangible ideals such as predictions, and typically cannot be fully tangibly measured whereas concrete thinking patterns typically involve constructs that can be fully measured from start to finish (think facts, numbers, statistics, etc).

Abstract thinking requires flexibility to be able to develop a solution(s) that fit the outcome and are usually highly individualized. Concrete thinking patterns tend to focus on simply solving the problem at hand using faster, non-flexible thought patterns and do not tend to include any measures of prediction or future-oriented thinking.

Am I an Abstract or Concrete Thinker?

One of the best ways to identify if you are an abstract or a concrete thinker is to test yourself. Give yourself a problem that needs to be solved and write down or record yourself speaking as you engage in the thought process.

Explore how you make your decisions:

- Was your decision-making process quick and did you settle on just one decision?

- What sources did you consider and how many did you consider as you pursued solutions for your decision?

Concrete thinkers also tend to gravitate towards tangible, measurable facts-based items to make decisions such as statistics. On the other hand, an abstract thinker might base their solution-making process on not only facts/statistics but also theories, philosophies, and other “abstract” thought patterns.

Published Nov 15, 2023

- Clinical writer

- Editorial writer

- Clinical reviewer

Alexandra “Alex” Cromer is a Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC) who has 4 years of experience partnering with adults, families, adolescents, and couples seeking help with depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and trauma-related disorders.

Theresa Lupcho is a Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC) with a passion for providing the utmost quality of services to individuals and couples struggling with relationship issues, depression, anxiety, abuse, ADHD, stress, family conflict, life transitions, grief, and more.

Jason Crosby is a Senior Copywriter at Thriveworks. He received his BA in English Writing from Montana State University with a minor in English Literature. Previously, Jason was a freelance writer for publications based in Seattle, WA, and Austin, TX.

We only use authoritative, trusted, and current sources in our articles. Read our editorial policy to learn more about our efforts to deliver factual, trustworthy information.

Dumontheil, I. (2014). Development of abstract thinking during childhood and adolescence: The role of rostrolateral prefrontal cortex . ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1878929314000516

Malik, F., & Marwaha, R. (2023, April 23). Cognitive development – StatPearls – NCBI bookshelf . National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537095/

The information on this page is not intended to replace assistance, diagnosis, or treatment from a clinical or medical professional. Readers are urged to seek professional help if they are struggling with a mental health condition or another health concern.

If you’re in a crisis, do not use this site. Please call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or use these resources to get immediate help.

Join our Newsletter

Get helpful tips and the latest information

Abstract Thinking: Definition, Benefits, & How to Improve It

Author: Andrea Brognano, LMHC, LPC, NCC

Andrea Brognano LMHC, LPC, NCC, CCMHC, ACS

Andrea empowers clients with compassion, specializing in corporate mental health, stress management, and empowering women entrepreneurs.

Abstract thinking isn’t just a fancy term for “thinking outside the box.” Instead, it’s a specific mindset that makes a person better at problem solving and creative thinking. Abstract thinking is a tool that we use in order to approach and resolve issues, while understanding new concepts in our day to day lives.