Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Tables and Figures

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Note: This page reflects the latest version of the APA Publication Manual (i.e., APA 7), which released in October 2019. The equivalent resources for the older APA 6 style can be found at this page as well as at this page (our old resources covered the material on this page on two separate pages).

The purpose of tables and figures in documents is to enhance your readers' understanding of the information in the document; usually, large amounts of information can be communicated more efficiently in tables or figures. Tables are any graphic that uses a row and column structure to organize information, whereas figures include any illustration or image other than a table.

General guidelines

Visual material such as tables and figures can be used quickly and efficiently to present a large amount of information to an audience, but visuals must be used to assist communication, not to use up space, or disguise marginally significant results behind a screen of complicated statistics. Ask yourself this question first: Is the table or figure necessary? For example, it is better to present simple descriptive statistics in the text, not in a table.

Relation of Tables or Figures and Text

Because tables and figures supplement the text, refer in the text to all tables and figures used and explain what the reader should look for when using the table or figure. Focus only on the important point the reader should draw from them, and leave the details for the reader to examine on their own.

Documentation

If you are using figures, tables and/or data from other sources, be sure to gather all the information you will need to properly document your sources.

Integrity and Independence

Each table and figure must be intelligible without reference to the text, so be sure to include an explanation of every abbreviation (except the standard statistical symbols and abbreviations).

Organization, Consistency, and Coherence

Number all tables sequentially as you refer to them in the text (Table 1, Table 2, etc.), likewise for figures (Figure 1, Figure 2, etc.). Abbreviations, terminology, and probability level values must be consistent across tables and figures in the same article. Likewise, formats, titles, and headings must be consistent. Do not repeat the same data in different tables.

Data in a table that would require only two or fewer columns and rows should be presented in the text. More complex data is better presented in tabular format. In order for quantitative data to be presented clearly and efficiently, it must be arranged logically, e.g. data to be compared must be presented next to one another (before/after, young/old, male/female, etc.), and statistical information (means, standard deviations, N values) must be presented in separate parts of the table. If possible, use canonical forms (such as ANOVA, regression, or correlation) to communicate your data effectively.

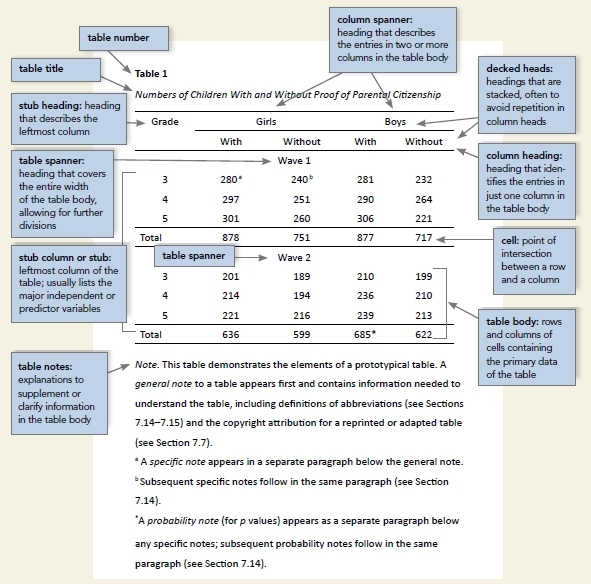

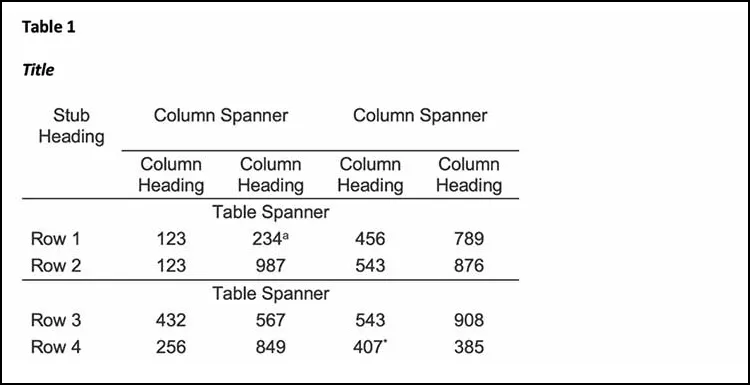

A generic example of a table with multiple notes formatted in APA 7 style.

Elements of Tables

Number all tables with Arabic numerals sequentially. Do not use suffix letters (e.g. Table 3a, 3b, 3c); instead, combine the related tables. If the manuscript includes an appendix with tables, identify them with capital letters and Arabic numerals (e.g. Table A1, Table B2).

Like the title of the paper itself, each table must have a clear and concise title. Titles should be written in italicized title case below the table number, with a blank line between the number and the title. When appropriate, you may use the title to explain an abbreviation parenthetically.

Comparison of Median Income of Adopted Children (AC) v. Foster Children (FC)

Keep headings clear and brief. The heading should not be much wider than the widest entry in the column. Use of standard abbreviations can aid in achieving that goal. There are several types of headings:

- Stub headings describe the lefthand column, or stub column , which usually lists major independent variables.

- Column headings describe entries below them, applying to just one column.

- Column spanners are headings that describe entries below them, applying to two or more columns which each have their own column heading. Column spanners are often stacked on top of column headings and together are called decked heads .

- Table Spanners cover the entire width of the table, allowing for more divisions or combining tables with identical column headings. They are the only type of heading that may be plural.

All columns must have headings, written in sentence case and using singular language (Item rather than Items) unless referring to a group (Men, Women). Each column’s items should be parallel (i.e., every item in a column labeled “%” should be a percentage and does not require the % symbol, since it’s already indicated in the heading). Subsections within the stub column can be shown by indenting headings rather than creating new columns:

Chemical Bonds

Ionic

Covalent

Metallic

The body is the main part of the table, which includes all the reported information organized in cells (intersections of rows and columns). Entries should be center aligned unless left aligning them would make them easier to read (longer entries, usually). Word entries in the body should use sentence case. Leave cells blank if the element is not applicable or if data were not obtained; use a dash in cells and a general note if it is necessary to explain why cells are blank. In reporting the data, consistency is key: Numerals should be expressed to a consistent number of decimal places that is determined by the precision of measurement. Never change the unit of measurement or the number of decimal places in the same column.

There are three types of notes for tables: general, specific, and probability notes. All of them must be placed below the table in that order.

General notes explain, qualify or provide information about the table as a whole. Put explanations of abbreviations, symbols, etc. here.

Example: Note . The racial categories used by the US Census (African-American, Asian American, Latinos/-as, Native-American, and Pacific Islander) have been collapsed into the category “non-White.” E = excludes respondents who self-identified as “White” and at least one other “non-White” race.

Specific notes explain, qualify or provide information about a particular column, row, or individual entry. To indicate specific notes, use superscript lowercase letters (e.g. a , b , c ), and order the superscripts from left to right, top to bottom. Each table’s first footnote must be the superscript a .

a n = 823. b One participant in this group was diagnosed with schizophrenia during the survey.

Probability notes provide the reader with the results of the tests for statistical significance. Asterisks indicate the values for which the null hypothesis is rejected, with the probability ( p value) specified in the probability note. Such notes are required only when relevant to the data in the table. Consistently use the same number of asterisks for a given alpha level throughout your paper.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001

If you need to distinguish between two-tailed and one-tailed tests in the same table, use asterisks for two-tailed p values and an alternate symbol (such as daggers) for one-tailed p values.

* p < .05, two-tailed. ** p < .01, two-tailed. † p <.05, one-tailed. †† p < .01, one-tailed.

Borders

Tables should only include borders and lines that are needed for clarity (i.e., between elements of a decked head, above column spanners, separating total rows, etc.). Do not use vertical borders, and do not use borders around each cell. Spacing and strict alignment is typically enough to clarify relationships between elements.

Example of a table in the text of an APA 7 paper. Note the lack of vertical borders.

Tables from Other Sources

If using tables from an external source, copy the structure of the original exactly, and cite the source in accordance with APA style .

Table Checklist

(Taken from the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7th ed., Section 7.20)

- Is the table necessary?

- Does it belong in the print and electronic versions of the article, or can it go in an online supplemental file?

- Are all comparable tables presented consistently?

- Are all tables numbered with Arabic numerals in the order they are mentioned in the text? Is the table number bold and left-aligned?

- Are all tables referred to in the text?

- Is the title brief but explanatory? Is it presented in italicized title case and left-aligned?

- Does every column have a column heading? Are column headings centered?

- Are all abbreviations; special use of italics, parentheses, and dashes; and special symbols explained?

- Are the notes organized according to the convention of general, specific, probability?

- Are table borders correctly used (top and bottom of table, beneath column headings, above table spanners)?

- Does the table use correct line spacing (double for the table number, title, and notes; single, one and a half, or double for the body)?

- Are entries in the left column left-aligned beneath the centered stub heading? Are all other column headings and cell entries centered?

- Are confidence intervals reported for all major point estimates?

- Are all probability level values correctly identified, and are asterisks attached to the appropriate table entries? Is a probability level assigned the same number of asterisks in all the tables in the same document?

- If the table or its data are from another source, is the source properly cited? Is permission necessary to reproduce the table?

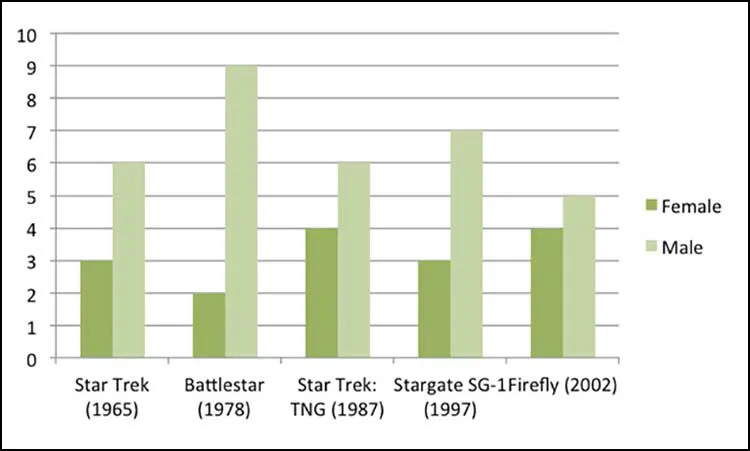

Figures include all graphical displays of information that are not tables. Common types include graphs, charts, drawings, maps, plots, and photos. Just like tables, figures should supplement the text and should be both understandable on their own and referenced fully in the text. This section details elements of formatting writers must use when including a figure in an APA document, gives an example of a figure formatted in APA style, and includes a checklist for formatting figures.

Preparing Figures

In preparing figures, communication and readability must be the ultimate criteria. Avoid the temptation to use the special effects available in most advanced software packages. While three-dimensional effects, shading, and layered text may look interesting to the author, overuse, inconsistent use, and misuse may distort the data, and distract or even annoy readers. Design properly done is inconspicuous, almost invisible, because it supports communication. Design improperly, or amateurishly, done draws the reader’s attention from the data, and makes him or her question the author’s credibility. Line drawings are usually a good option for readability and simplicity; for photographs, high contrast between background and focal point is important, as well as cropping out extraneous detail to help the reader focus on the important aspects of the photo.

Parts of a Figure

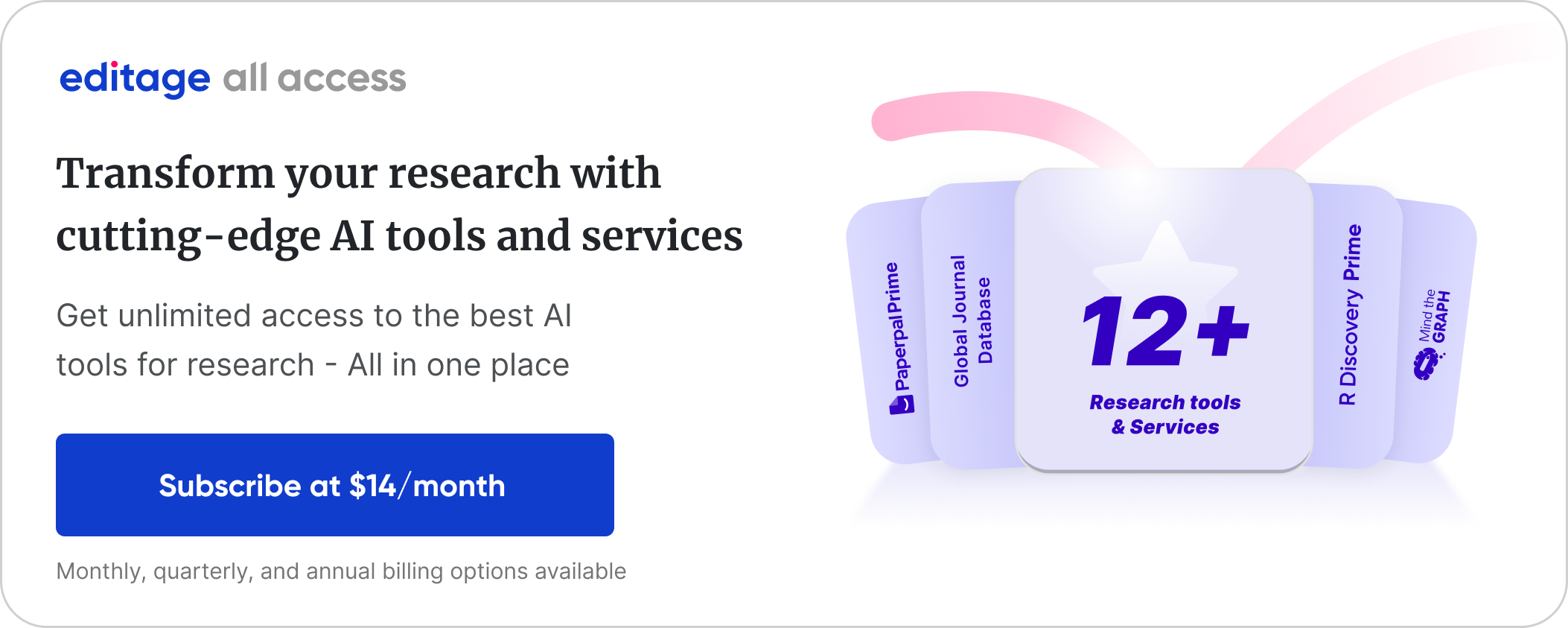

All figures that are part of the main text require a number using Arabic numerals (Figure 1, Figure 2, etc.). Numbers are assigned based on the order in which figures appear in the text and are bolded and left aligned.

Under the number, write the title of the figure in italicized title case. The title should be brief, clear, and explanatory, and both the title and number should be double spaced.

The image of the figure is the body, and it is positioned underneath the number and title. The image should be legible in both size and resolution; fonts should be sans serif, consistently sized, and between 8-14 pt. Title case should be used for axis labels and other headings; descriptions within figures should be in sentence case. Shading and color should be limited for clarity; use patterns along with color and check contrast between colors with free online checkers to ensure all users (people with color vision deficiencies or readers printing in grayscale, for instance) can access the content. Gridlines and 3-D effects should be avoided unless they are necessary for clarity or essential content information.

Legends, or keys, explain symbols, styles, patterns, shading, or colors in the image. Words in the legend should be in title case; legends should go within or underneath the image rather than to the side. Not all figures will require a legend.

Notes clarify the content of the figure; like tables, notes can be general, specific, or probability. General notes explain units of measurement, symbols, and abbreviations, or provide citation information. Specific notes identify specific elements using superscripts; probability notes explain statistical significance of certain values.

A generic example of a figure formatted in APA 7 style.

Figure Checklist

(Taken from the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7 th ed., Section 7.35)

- Is the figure necessary?

- Does the figure belong in the print and electronic versions of the article, or is it supplemental?

- Is the figure simple, clean, and free of extraneous detail?

- Is the figure title descriptive of the content of the figure? Is it written in italic title case and left aligned?

- Are all elements of the figure clearly labeled?

- Are the magnitude, scale, and direction of grid elements clearly labeled?

- Are parallel figures or equally important figures prepared according to the same scale?

- Are the figures numbered consecutively with Arabic numerals? Is the figure number bold and left aligned?

- Has the figure been formatted properly? Is the font sans serif in the image portion of the figure and between sizes 8 and 14?

- Are all abbreviations and special symbols explained?

- If the figure has a legend, does it appear within or below the image? Are the legend’s words written in title case?

- Are the figure notes in general, specific, and probability order? Are they double-spaced, left aligned, and in the same font as the paper?

- Are all figures mentioned in the text?

- Has written permission for print and electronic reuse been obtained? Is proper credit given in the figure caption?

- Have all substantive modifications to photographic images been disclosed?

- Are the figures being submitted in a file format acceptable to the publisher?

- Have the files been produced at a sufficiently high resolution to allow for accurate reproduction?

- Privacy Policy

Home » Tables in Research Paper – Types, Creating Guide and Examples

Tables in Research Paper – Types, Creating Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Tables in Research Paper

Definition:

In Research Papers , Tables are a way of presenting data and information in a structured format. Tables can be used to summarize large amounts of data or to highlight important findings. They are often used in scientific or technical papers to display experimental results, statistical analyses, or other quantitative information.

Importance of Tables in Research Paper

Tables are an important component of a research paper as they provide a clear and concise presentation of data, statistics, and other information that support the research findings . Here are some reasons why tables are important in a research paper:

- Visual Representation : Tables provide a visual representation of data that is easy to understand and interpret. They help readers to quickly grasp the main points of the research findings and draw their own conclusions.

- Organize Data : Tables help to organize large amounts of data in a systematic and structured manner. This makes it easier for readers to identify patterns and trends in the data.

- Clarity and Accuracy : Tables allow researchers to present data in a clear and accurate manner. They can include precise numbers, percentages, and other information that may be difficult to convey in written form.

- Comparison: Tables allow for easy comparison between different data sets or groups. This makes it easier to identify similarities and differences, and to draw meaningful conclusions from the data.

- Efficiency: Tables allow for a more efficient use of space in the research paper. They can convey a large amount of information in a compact and concise format, which saves space and makes the research paper more readable.

Types of Tables in Research Paper

Most common Types of Tables in Research Paper are as follows:

- Descriptive tables : These tables provide a summary of the data collected in the study. They are usually used to present basic descriptive statistics such as means, medians, standard deviations, and frequencies.

- Comparative tables : These tables are used to compare the results of different groups or variables. They may be used to show the differences between two or more groups or to compare the results of different variables.

- Correlation tables: These tables are used to show the relationships between variables. They may show the correlation coefficients between variables, or they may show the results of regression analyses.

- Longitudinal tables : These tables are used to show changes in variables over time. They may show the results of repeated measures analyses or longitudinal regression analyses.

- Qualitative tables: These tables are used to summarize qualitative data such as interview transcripts or open-ended survey responses. They may present themes or categories that emerged from the data.

How to Create Tables in Research Paper

Here are the steps to create tables in a research paper:

- Plan your table: Determine the purpose of the table and the type of information you want to include. Consider the layout and format that will best convey your information.

- Choose a table format : Decide on the type of table you want to create. Common table formats include basic tables, summary tables, comparison tables, and correlation tables.

- Choose a software program : Use a spreadsheet program like Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets to create your table. These programs allow you to easily enter and manipulate data, format the table, and export it for use in your research paper.

- Input data: Enter your data into the spreadsheet program. Make sure to label each row and column clearly.

- Format the table : Apply formatting options such as font, font size, font color, cell borders, and shading to make your table more visually appealing and easier to read.

- Insert the table into your paper: Copy and paste the table into your research paper. Make sure to place the table in the appropriate location and refer to it in the text of your paper.

- Label the table: Give the table a descriptive title that clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of the table. Also, include a number and a caption that explains the table in more detail.

- Check for accuracy: Review the table for accuracy and make any necessary changes before submitting your research paper.

Examples of Tables in Research Paper

Examples of Tables in the Research Paper are as follows:

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | N = 200 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 35.2 (8.6) | |

| Range | 21-57 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 92 | 46 |

| Female | 108 | 54 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 20 | 10 |

| High school graduate | 60 | 30 |

| Some college | 70 | 35 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 50 | 25 |

This table shows the demographic characteristics of 200 participants in a research study. The table includes information about age, gender, and education level. The mean age of the participants was 35.2 years with a standard deviation of 8.6 years, and the age range was between 21 and 57 years. The table also shows that 46% of the participants were male and 54% were female. In terms of education, 10% of the participants had less than a high school education, 30% were high school graduates, 35% had some college education, and 25% had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Table 2: Summary of Key Findings

| Variable | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean score | 76.3 | 84.7 | 72.1 |

| Standard deviation | 5.2 | 6.9 | 4.8 |

| t-value | -2.67* | 1.89 | -1.24 |

| p-value | < 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.22 |

This table summarizes the key findings of a study comparing three different groups on a particular variable. The table shows the mean score, standard deviation, t-value, and p-value for each group. The asterisk next to the t-value for Group 1 indicates that the difference between Group 1 and the other groups was statistically significant at p < 0.01, while the differences between Group 2 and Group 3 were not statistically significant.

Purpose of Tables in Research Paper

The primary purposes of including tables in a research paper are:

- To present data: Tables are an effective way to present large amounts of data in a clear and organized manner. Researchers can use tables to present numerical data, survey results, or other types of data that are difficult to represent in text.

- To summarize data: Tables can be used to summarize large amounts of data into a concise and easy-to-read format. Researchers can use tables to summarize the key findings of their research, such as descriptive statistics or the results of regression analyses.

- To compare data : Tables can be used to compare data across different variables or groups. Researchers can use tables to compare the characteristics of different study populations or to compare the results of different studies on the same topic.

- To enhance the readability of the paper: Tables can help to break up long sections of text and make the paper more visually appealing. By presenting data in a table, researchers can help readers to quickly identify the most important information and understand the key findings of the study.

Advantages of Tables in Research Paper

Some of the advantages of using tables in research papers include:

- Clarity : Tables can present data in a way that is easy to read and understand. They can help readers to quickly and easily identify patterns, trends, and relationships in the data.

- Efficiency: Tables can save space and reduce the need for lengthy explanations or descriptions of the data in the main body of the paper. This can make the paper more concise and easier to read.

- Organization: Tables can help to organize large amounts of data in a logical and meaningful way. This can help to reduce confusion and make it easier for readers to navigate the data.

- Comparison : Tables can be useful for comparing data across different groups, variables, or time periods. This can help to highlight similarities, differences, and changes over time.

- Visualization : Tables can also be used to visually represent data, making it easier for readers to see patterns and trends. This can be particularly useful when the data is complex or difficult to understand.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and...

Appendices – Writing Guide, Types and Examples

Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Research Techniques – Methods, Types and Examples

Research Summary – Structure, Examples and...

Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to...

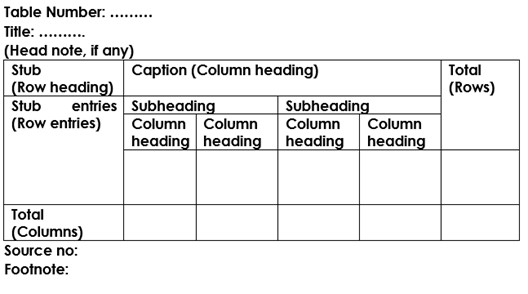

Table Setup

Tables are visual displays composed of columns and rows in which numbers, text, or a combination of numbers and text are presented. There are many common kinds of tables, including demographic characteristics tables, correlation tables, factor analysis tables, analysis of variance tables, and regression tables.

This page addresses the basics of table setup, including table components, principles of table construction (including the use of borders and how to handle long or wide tables), and placement of tables in the paper. Note that tables and figures have the same overall setup.

View the sample tables to see these guidelines in action.

Table components

APA Style tables have the following basic components:

- number: The table number (e.g., Table 1) appears above the table title and body in bold font. Number tables in the order in which they are mentioned in your paper.

- title: The table title appears one double-spaced line below the table number. Give each table a brief but descriptive title, and capitalize the table title in italic title case .

- headings: Tables may include a variety of headings depending on the nature and arrangement of the data. All tables should include column headings, including a stub heading (heading for the leftmost, or stub, column). The heading “Variable” is often used for the stub column if no other heading is suitable. Some tables also include column spanners, decked heads, and table spanners; these are described in the Publication Manual . Center column headings and capitalize them in sentence case .

- The table body may be single-spaced, one-and-a-half-spaced, or double-spaced.

- Left-align the information in the leftmost column or stub column of the table body (but center the heading).

- In general, center information in all other cells of the table. However, left-align the information if doing so would improve readability, particularly when cells contain lots of text.

- note: Three types of notes (general, specific, and probability) appear below the table as needed to describe contents of the table that cannot be understood from the table title or body alone (e.g., definitions of abbreviations, copyright attribution, explanations of asterisks used to indicate p values). Include table notes only as needed.

This diagram is an illustration of the basic table components.

Tables are covered in the seventh edition APA Style manuals in the Publication Manual Sections 7.8 to 7.21 and the Concise Guide Sections 7.8 to 7.21

Related handout

- Student Paper Setup Guide (PDF, 3MB)

Principles of table construction

The most important principle to follow when creating a table is to present information in a way that is easy for readers to understand. Provide sufficient information in the table itself so that readers do not need to read the text to understand it.

When creating a table, place entries that are to be compared next to each other. In general, place different indices (e.g., means and standard deviations) in different columns rather than in the same column. Use the same font in tables as in the rest of your paper.

Use the tables feature of your word-processing program to create tables in APA Style papers. Do not use the tab key or space bar to manually create the look of a table.

Table borders

Limit the use of borders or lines in a table to those needed for clarity. In general, use a border at the top and bottom of the table, beneath column headings (including decked heads), and above column spanners. You may also use a border to separate a row containing totals or other summary information from other rows in the table.

Do not use vertical borders to separate data, and do not use borders around every cell in a table. Use spacing between columns and rows and strict alignment to clarify relations among the elements in a table.

Long or wide tables

If a table is longer than one page, use the tables feature of your word-processing program to make the headings row repeat on the second and any subsequent pages. No other adjustments are necessary. If a table is too wide to fit on one page, use landscape orientation on the page with the wide table. It does not matter if the page header also moves when switching to landscape orientation.

Placement of tables in a paper

There are two options for the placement of tables (and figures) in a paper. The first is to embed tables in the text after each is first mentioned (or “called out”); the second is to place each table on a separate page after the reference list.

An embedded table may take up an entire page; if the table is short, however, text may appear on the same page as the table. In that case, place the table at either the top or bottom of the page rather than in the middle. Also add one blank double-spaced line between the table and any text to improve the visual presentation.

View the sample tables for more information on tables.

How to make a scientific table | Step-by-step and Formatting

It’s time to learn how to make a scientific table to increase the readability and attractiveness of your research paper.

When writing a research paper, there is frequently a massive quantity of data that must be incorporated to meet the research’s purpose. Instead of stuffing your research paper with all this information, you can employ visual assets to make it simpler to read and use to your advantage to make it more appealing to readers.

In this Mind The Graph article, you will learn how to make a scientific table properly, to attract readers and improve understandability.

What is a scientific table and what are its purposes?

Tables are typically used to organize data that is too extensive or nuanced to properly convey in the text, allowing the reader to quickly see and comprehend the findings. Tables can be used to summarize information, explain variables, or organize and present surveys. They can be used to highlight trends or patterns in data and to make research more readable by separating numerical data from text. Tables, although full, should not be overly convoluted.

Tables can only display numerical values and text in columns and rows. Any other type of illustration, such as a chart, graph, photograph, drawing, and so on is called a figure.

If you’re not sure whether to use tables or figures in your research, see How to Include Figures in a Research Paper to find out.

Table formatting

This section teaches you all you need to know on how to make a scientific table to include in your research paper. The proper table format is extremely basic and straightforward to accomplish, here’s a simple guideline to help you:

- Number: If you have more than one table, number them sequentially (Table 1, Table 2…).

- Referencing: Each table must be referred to in the text with a capital T: “as seen in Table 1”.

- Title: Make sure the title corresponds to the topic of the table. Tables should have a precise, informative title that serves as an explanation for the table. Titles can be short or long depending on their subject.

- Column headings: Headings must be helpful and clear when representing the type of data provided. The reader’s attention is drawn progressively from the headline to the column title. A solid collection of column headings will help the reader understand what the table is about immediately.

- Table body: This is the major section of the table that contains numerical or textual data. Make your table such that the elements read from top to bottom, not across.

- Needed information: Make sure to include units, error values and number of samples, as well as explain whatever abbreviation or symbol is used in tables.

- Lines: Limit the use of lines, only use what’s necessary.

Steps to make an effective scientific table

Now that you understand the fundamentals of how to make a scientific table , consider the following ideas and best practices for creating the most effective tables for your research work:

- If your study includes both a table and a graph, avoid including the same information in both.

- Do not duplicate information from a table in a text.

- Make your table aesthetically appealing and easy to read by leaving enough space between columns and rows and using a basic yet effective structure.

- If your table has a lot of information, consider categorizing it and dividing it into columns.

- Consider merging tables with repeated information or deleting those that may not be essential.

- Use footnotes to highlight important information for any of the cells. Use an alphabetical footnote marker if your table contains numerical data.

- Cite the reference if the table you’re displaying contains data from prior research to avoid plagiarism.

Make scientifically accurate infographics in minutes

Aside from adding tables to make your research paper more precise and appealing, consider using infographics, Mind the Graph is a simple tool for creating excellent scientific infographics that may help you solidify and improve the authority of your research.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Sign Up for Free

Try the best infographic maker and promote your research with scientifically-accurate beautiful figures

no credit card required

About Jessica Abbadia

Jessica Abbadia is a lawyer that has been working in Digital Marketing since 2020, improving organic performance for apps and websites in various regions through ASO and SEO. Currently developing scientific and intellectual knowledge for the community's benefit. Jessica is an animal rights activist who enjoys reading and drinking strong coffee.

Content tags

- Editing & Proofreading

- Writing Tips

Creating tables in scientific papers: basic formatting and title

Tables are a very important part of scientific papers. A good table should present the data simply, clearly and neatly, and allow the reader to understand the results without having to look at other sections of the paper. A bad table can be very confusing, and may reduce the chances of your paper being accepted.

In this post, we will look at the basic rules for creating effective scientific tables.

Let’s begin with an example of a bad table, highlighting some common errors and showing how the table can be improved.

Can you see anything wrong with this table?

Fig. 1: Example of a poorly formatted table that can be improved

Let’s start with the table formatting and editing.

Rule 1. Use a separate cell for each value

In the top row of Fig. 2 (below), the author has placed two columns of data in the same cell. We often see tables with only one row and column, with the rows of data arranged using the space bar or "tab" button.

If the table is adjusted or moved (for example, if the table size or text size is changed) the table layout will change, causing the data to be misplaced (as shown in the bottom of Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Tables created without cells can become disorganised if resized or moved

Additionally, if there are empty cells, rows or columns, it can be difficult to know if data is missing from the table, and impossible to know which columns or rows the data should be in.

Therefore, tables should be created with the correct number of rows and columns - use one cell for each piece of data.

You can add new rows and columns to an existing table by right clicking on the table, selecting “Insert” and choosing to insert new rows and columns above or below the existing rows or columns.

It is also possible to insert multiple rows/columns to a table at the same time. For example, if you would like to add three columns to the left of your table, highlight the first three columns, right click and choose “Insert Columns to the Left”.

Rule 2. Use only horizontal line borders and double line spacing

Most journals ask that tables only contain only horizontal lines as borders. Additionally, most journals require the text in tables to be double-spaced. It is always a good idea to look at the “Instructions to Authors” for your journal, and check if there are any special instructions for tables.

In Microsoft Word (version 2007 onwards), you can change the table borders by clicking on the table and using the menu that appears in the “Design” section under “Table Tools” - as indicated by the red arrows in Fig. 3.

Alternatively, right click your mouse over the table, and click “Borders and Shading” to change the table borders.

Fig. 3: How to format table borders in Microsoft Word

Rule 3. Use clear and informative titles

Generally, you should include information on the test system (e.g. the species, cell line or type of patients), as well as the type of treatment (e.g. salinity or the drug name) and what was measured (e.g. plant height, blood pressure or cell proliferation).

So the title for the Table 1 could be:

- Table 1. Height of wheat plants after salinity treatment

- Table 1. Effect of salinity on the growth of wheat plants

Sometimes, it can also be a good idea to describe the main result in the table title. This will help the reader quickly understand your data.

For example:

- Table 1. Salinity reduces the growth of wheat plants

- Table 1. Exposure to salinity reduces the growth of wheat plants

It’s not always possible or necessary to include the result in the table title, for example tables that show a list of data (such as patient characteristics, plant cultivars or PCR primers) or tables that contain complex or conflicting data.

Let’s see how the table changes if we apply these rules to the Table 1. I’ll insert a new column to the left of the table and place each value in a separate cell (rule 1), only use vertical rules and double space the table (rule 2) and use an informative title (rule 3).

Fig. 4: Improved table after placing values in individual cells, formatting and double spacing, and adding an informative title

At Science Editing Experts, we help scientists like you to submit well-written journal papers with confidence and complete your thesis without headaches, so you can focus on your research and career.

Andrea Devlin PhD

Chief editor and owner of Science Editing Experts

30 simple "word swaps" to improve your scientific writing

Discover these easy 'Find and Replace' strategies to make your dissertation or journal manuscript clearer, with zero effort!

Busy scientists...

discover 30 word swaps to improve your scientific writing

Easy 'Find and Replace' strategies to make your scientific writing clearer, with zero effort!

Editing & Proofreadin g

GDPR/Privacy

Website Terms

Course/Coaching Terms

Image Attribution

2 Drumgrannon Heights, Moy, Northern Ireland, BT71 7TW, UK.

© Science Editing Experts 2022-2024. All Rights Reserved.

Effective Use of Tables and Figures in Research Papers

Research papers are often based on copious amounts of data that can be summarized and easily read through tables and graphs. When writing a research paper , it is important for data to be presented to the reader in a visually appealing way. The data in figures and tables, however, should not be a repetition of the data found in the text. There are many ways of presenting data in tables and figures, governed by a few simple rules. An APA research paper and MLA research paper both require tables and figures, but the rules around them are different. When writing a research paper, the importance of tables and figures cannot be underestimated. How do you know if you need a table or figure? The rule of thumb is that if you cannot present your data in one or two sentences, then you need a table .

Using Tables

Tables are easily created using programs such as Excel. Tables and figures in scientific papers are wonderful ways of presenting data. Effective data presentation in research papers requires understanding your reader and the elements that comprise a table. Tables have several elements, including the legend, column titles, and body. As with academic writing, it is also just as important to structure tables so that readers can easily understand them. Tables that are disorganized or otherwise confusing will make the reader lose interest in your work.

- Title: Tables should have a clear, descriptive title, which functions as the “topic sentence” of the table. The titles can be lengthy or short, depending on the discipline.

- Column Titles: The goal of these title headings is to simplify the table. The reader’s attention moves from the title to the column title sequentially. A good set of column titles will allow the reader to quickly grasp what the table is about.

- Table Body: This is the main area of the table where numerical or textual data is located. Construct your table so that elements read from up to down, and not across.

Related: Done organizing your research data effectively in tables? Check out this post on tips for citing tables in your manuscript now!

The placement of figures and tables should be at the center of the page. It should be properly referenced and ordered in the number that it appears in the text. In addition, tables should be set apart from the text. Text wrapping should not be used. Sometimes, tables and figures are presented after the references in selected journals.

Using Figures

Figures can take many forms, such as bar graphs, frequency histograms, scatterplots, drawings, maps, etc. When using figures in a research paper, always think of your reader. What is the easiest figure for your reader to understand? How can you present the data in the simplest and most effective way? For instance, a photograph may be the best choice if you want your reader to understand spatial relationships.

- Figure Captions: Figures should be numbered and have descriptive titles or captions. The captions should be succinct enough to understand at the first glance. Captions are placed under the figure and are left justified.

- Image: Choose an image that is simple and easily understandable. Consider the size, resolution, and the image’s overall visual attractiveness.

- Additional Information: Illustrations in manuscripts are numbered separately from tables. Include any information that the reader needs to understand your figure, such as legends.

Common Errors in Research Papers

Effective data presentation in research papers requires understanding the common errors that make data presentation ineffective. These common mistakes include using the wrong type of figure for the data. For instance, using a scatterplot instead of a bar graph for showing levels of hydration is a mistake. Another common mistake is that some authors tend to italicize the table number. Remember, only the table title should be italicized . Another common mistake is failing to attribute the table. If the table/figure is from another source, simply put “ Note. Adapted from…” underneath the table. This should help avoid any issues with plagiarism.

Using tables and figures in research papers is essential for the paper’s readability. The reader is given a chance to understand data through visual content. When writing a research paper, these elements should be considered as part of good research writing. APA research papers, MLA research papers, and other manuscripts require visual content if the data is too complex or voluminous. The importance of tables and graphs is underscored by the main purpose of writing, and that is to be understood.

Frequently Asked Questions

"Consider the following points when creating figures for research papers: Determine purpose: Clarify the message or information to be conveyed. Choose figure type: Select the appropriate type for data representation. Prepare and organize data: Collect and arrange accurate and relevant data. Select software: Use suitable software for figure creation and editing. Design figure: Focus on clarity, labeling, and visual elements. Create the figure: Plot data or generate the figure using the chosen software. Label and annotate: Clearly identify and explain all elements in the figure. Review and revise: Verify accuracy, coherence, and alignment with the paper. Format and export: Adjust format to meet publication guidelines and export as suitable file."

"To create tables for a research paper, follow these steps: 1) Determine the purpose and information to be conveyed. 2) Plan the layout, including rows, columns, and headings. 3) Use spreadsheet software like Excel to design and format the table. 4) Input accurate data into cells, aligning it logically. 5) Include column and row headers for context. 6) Format the table for readability using consistent styles. 7) Add a descriptive title and caption to summarize and provide context. 8) Number and reference the table in the paper. 9) Review and revise for accuracy and clarity before finalizing."

"Including figures in a research paper enhances clarity and visual appeal. Follow these steps: Determine the need for figures based on data trends or to explain complex processes. Choose the right type of figure, such as graphs, charts, or images, to convey your message effectively. Create or obtain the figure, properly citing the source if needed. Number and caption each figure, providing concise and informative descriptions. Place figures logically in the paper and reference them in the text. Format and label figures clearly for better understanding. Provide detailed figure captions to aid comprehension. Cite the source for non-original figures or images. Review and revise figures for accuracy and consistency."

"Research papers use various types of tables to present data: Descriptive tables: Summarize main data characteristics, often presenting demographic information. Frequency tables: Display distribution of categorical variables, showing counts or percentages in different categories. Cross-tabulation tables: Explore relationships between categorical variables by presenting joint frequencies or percentages. Summary statistics tables: Present key statistics (mean, standard deviation, etc.) for numerical variables. Comparative tables: Compare different groups or conditions, displaying key statistics side by side. Correlation or regression tables: Display results of statistical analyses, such as coefficients and p-values. Longitudinal or time-series tables: Show data collected over multiple time points with columns for periods and rows for variables/subjects. Data matrix tables: Present raw data or matrices, common in experimental psychology or biology. Label tables clearly, include titles, and use footnotes or captions for explanations."

Enago is a very useful site. It covers nearly all topics of research writing and publishing in a simple, clear, attractive way. Though I’m a journal editor having much knowledge and training in these issues, I always find something new in this site. Thank you

“Thank You, your contents really help me :)”

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Explanatory & Response Variable in Statistics — A quick guide for early career researchers!

Often researchers have a difficult time choosing the parameters and variables (like explanatory and response…

- Manuscript Preparation

- Publishing Research

How to Use Creative Data Visualization Techniques for Easy Comprehension of Qualitative Research

“A picture is worth a thousand words!”—an adage used so often stands true even whilst…

- Figures & Tables

Effective Use of Statistics in Research – Methods and Tools for Data Analysis

Remember that impending feeling you get when you are asked to analyze your data! Now…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

SCI中稿技巧: 提升研究数据的说服力

如何寻找原创研究课题 快速定位目标文献的有效搜索策略 如何根据期刊指南准备手稿的对应部分 论文手稿语言润色实用技巧分享,快速提高论文质量

Distill: A Journal With Interactive Images for Machine Learning Research

Research is a wide and extensive field of study. This field has welcomed a plethora…

Explanatory & Response Variable in Statistics — A quick guide for early career…

How to Create and Use Gantt Charts

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- Industry News

- AI in Academia

- Promoting Research

- Career Corner

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Peer-Review Week 2023

- Open Access Week 2023

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

In your opinion, what is the most effective way to improve integrity in the peer review process?

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

How to Use Tables and Figures effectively in Research Papers

- 3 minute read

- 51.7K views

Table of Contents

Data is the most important component of any research. It needs to be presented effectively in a paper to ensure that readers understand the key message in the paper. Figures and tables act as concise tools for clear presentation . Tables display information arranged in rows and columns in a grid-like format, while figures convey information visually, and take the form of a graph, diagram, chart, or image. Be it to compare the rise and fall of GDPs among countries over the years or to understand how COVID-19 has impacted incomes all over the world, tables and figures are imperative to convey vital findings accurately.

So, what are some of the best practices to follow when creating meaningful and attractive tables and figures? Here are some tips on how best to present tables and figures in a research paper.

Guidelines for including tables and figures meaningfully in a paper:

- Self-explanatory display items: Sometimes, readers, reviewers and journal editors directly go to the tables and figures before reading the entire text. So, the tables need to be well organized and self-explanatory.

- Avoidance of repetition: Tables and figures add clarity to the research. They complement the research text and draw attention to key points. They can be used to highlight the main points of the paper, but values should not be repeated as it defeats the very purpose of these elements.

- Consistency: There should be consistency in the values and figures in the tables and figures and the main text of the research paper.

- Informative titles: Titles should be concise and describe the purpose and content of the table. It should draw the reader’s attention towards the key findings of the research. Column heads, axis labels, figure labels, etc., should also be appropriately labelled.

- Adherence to journal guidelines: It is important to follow the instructions given in the target journal regarding the preparation and presentation of figures and tables, style of numbering, titles, image resolution, file formats, etc.

Now that we know how to go about including tables and figures in the manuscript, let’s take a look at what makes tables and figures stand out and create impact.

How to present data in a table?

For effective and concise presentation of data in a table, make sure to:

- Combine repetitive tables: If the tables have similar content, they should be organized into one.

- Divide the data: If there are large amounts of information, the data should be divided into categories for more clarity and better presentation. It is necessary to clearly demarcate the categories into well-structured columns and sub-columns.

- Keep only relevant data: The tables should not look cluttered. Ensure enough spacing.

Example of table presentation in a research paper

For comprehensible and engaging presentation of figures:

- Ensure clarity: All the parts of the figure should be clear. Ensure the use of a standard font, legible labels, and sharp images.

- Use appropriate legends: They make figures effective and draw attention towards the key message.

- Make it precise: There should be correct use of scale bars in images and maps, appropriate units wherever required, and adequate labels and legends.

It is important to get tables and figures correct and precise for your research paper to convey your findings accurately and clearly. If you are confused about how to suitably present your data through tables and figures, do not worry. Elsevier Author Services are well-equipped to guide you through every step to ensure that your manuscript is of top-notch quality.

How to Write an Effective Problem Statement for Your Research Paper

What is the Background of a Study and How Should it be Written?

You may also like.

Submission 101: What format should be used for academic papers?

Page-Turner Articles are More Than Just Good Arguments: Be Mindful of Tone and Structure!

A Must-see for Researchers! How to Ensure Inclusivity in Your Scientific Writing

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- SpringerLink shop

Figures and tables

Figures and tables (display items) are often the quickest way to communicate large amounts of complex information that would be complicated to explain in text.

Many readers will only look at your display items without reading the main text of your manuscript. Therefore, ensure your display items can stand alone from the text and communicate clearly your most significant results.

Display items are also important for attracting readers to your work. Well designed and attractive display items will hold the interest of readers, compel them to take time to understand a figure and can even entice them to read your full manuscript.

Finally, high-quality display items give your work a professional appearance . Readers will assume that a professional-looking manuscript contains good quality science. Thus readers may be more likely to trust your results and your interpretation of those results.

When deciding which of your results to present as display items consider the following questions:

- Are there any data that readers might rather see as a display item rather than text?

- Do your figures supplement the text and not just repeat what you have already stated?

- Have you put data into a table that could easily be explained in the text such as simple statistics or p values?

Tables are a concise and effective way to present large amounts of data. You should design them carefully so that you clearly communicate your results to busy researchers.

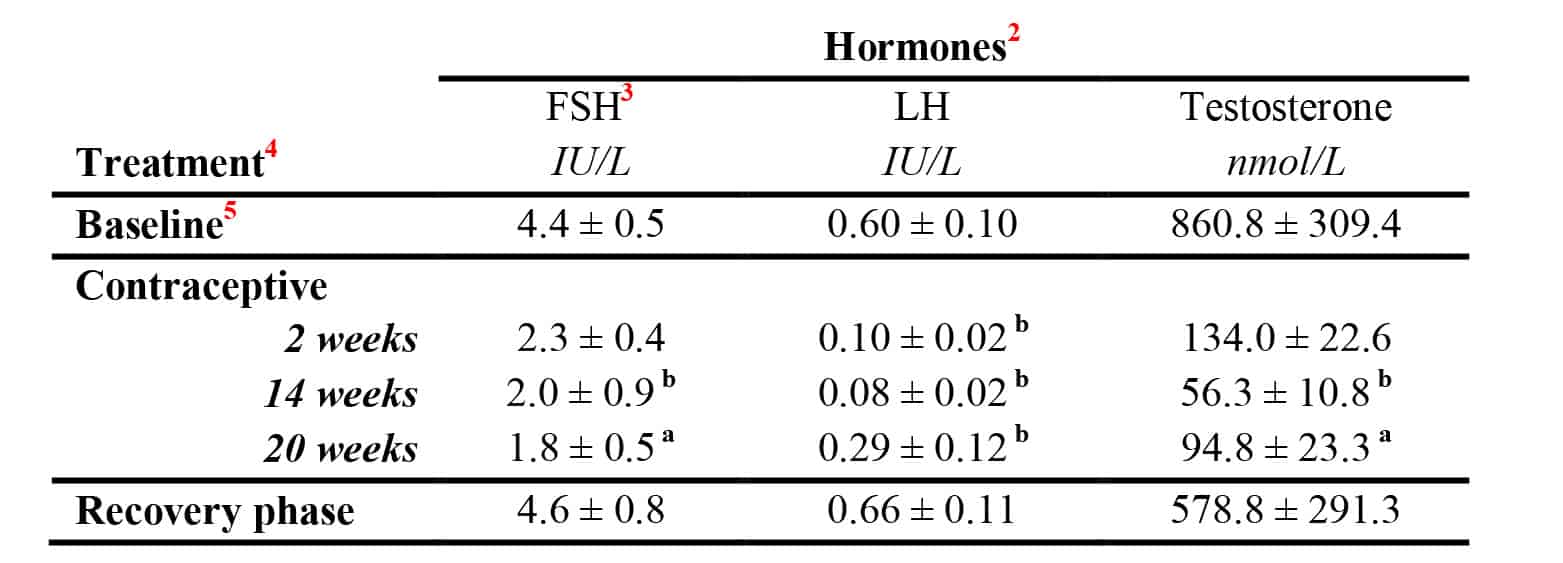

The following is an example of a well-designed table:

- Clear and concise legend/caption

- Data divided into categories for clarity

- Sufficient spacing between columns and rows

- Units are provided

- Font type and size are legible

How to create tables from data

What is a table? Tables present the results of data or information collected from a study. The purpose of a table is to present data summaries to help the reader to understand what was found. Not all data needs to go into a table: some results are simply presented as written text in the results section; data that shows a trend or a pattern in between variables is presented in figures, while additional data not necessary to explain the study should go into the appendix. Tables should convey data or information clearly and concisely and allow the key message to be interpreted at a glance. Tables often include detailed data in rows and columns, while sub-columns are often nested within larger columns.

Designing your table Once you have decided what data to present, jot down a rough draft of the table headings on paper to determine how many columns and rows you need. Choose categories with accurate labels that match your methodology and analysis. Before you spend too much time designing the layout of your table, check that you are following the format expected within your discipline or organisation as table formatting requirements often vary considerably; if you are preparing a science report, refer to the relevant In-House Style Guide(s) or if you are preparing a journal article, meticulously follow the journal’s Instruction to Authors. Title or Legend Consider the objective and key message of each table. The table title is typically placed at the top of the table. It should stand alone: it needs to be clearly understood by your target audience without them needing to go back to the results or methods sections. The title should be concise and describe what was measured, e.g. ‘Reproductive hormone levels during contraceptive administration in men’. Frame the title so that it conveys the key results, e.g. ‘Reproductive hormones are suppressed during contraceptive administration in men’. Sub-headings Take care to ensure the sub-headings are meaningful and accurate. The row and column headings clearly explain the treatment or data type, and include units. In the sample table below, the experimental details are given in the row headings (time points during the administration of a contraceptive), and the data measured (hormones) are given in the column headings.

Example Table

In this example table, horizontal lines have been used sparingly to improve clarity.

Explanatory notes Explanatory notes and footnotes are placed at the end of the table. Make sure that all abbreviations are defined and that the values are explained. For example, if the values are a percentage, mean ± SEM, n per group. Drawing and formatting the table Tables for publication can be created in Word, using the 'Insert Table' function. For instructions see: Office Support: Insert or create a table .

- Tables can also be created from existing datasets in Excel, and then cut and pasted into Word, or exported into Word as an image.

- Use a separate cell for each piece of information; avoid having to insert tabs or spaces which may cause the text to be unintentionally moved when the formatting is adjusted.

- Add your headings and data to each cell. Cells can be merged to create headings above sub-headings. Select the cells you want to merge then select the 'Merge Cells' option.

- The table then needs to be formatted to improve readability and clarity. Select the entire table or individual rows or columns and right click. Options will appear where you can modify the table size, cell height and width, and format the borders. Word tables will have borders on each side of the cell by default.

- Format the borders by selecting columns, rows or individual cells will help the table to take shape and improve visual clarity. Text within the table can be formatted by selecting the text, then formatting it as normal.

- Make sure that the columns and rows are well separated and that the table is not cluttered and is easy to read. Imagine the reader looking at your table: do they have access to all of the information they need and can they easily understand the results?

Formatting borders helps a table to take shape and improve clarity. Select and de-select the horizontal and vertical lines you want to use as borders

Citing the table

Always cite the table at the relevant point in your text. Avoid repeating the details that are presented in the table, and use the text to direct the reader to the main message, e.g. ‘ Contraceptive administration at 14 and 20 weeks significantly suppressed FSH, LH and testosterone levels in men (Table 1) ’. Tables should be numbered consecutively throughout the document.

Further reading: (external links)

* Creating tables in scientific papers: basic formatting and titles * How to create and customize tables in Microsoft Word * Tips on effective use of tables and figures in research papers * Tables and Figures * Office Support: Insert or create a table

© Dr Liza O’Donnell & Dr Marina Hurley 2019 www.writingclearscience.com.au

Any suggestions or comments please email [email protected]

Find out more about our new online course...

How to be an Efficient Science Writer

The Essentials of Sentence Structure

Now includes feedback on your writing Learn more...

SUBSCRIBE to the Writing Clear Science Newsletter

to keep informed about our latest blogs, webinars and writing courses.

FURTHER READING

- Co-authors should define their roles and responsibilities before they start writing

- The difference between a writing rule and a good idea

- When to cite and when not to

- How to create figures from data

- Back to basics: science knowledge is gained while information is produced

- How to build and maintain confidence as a writer

- If science was perfect, it wouldn’t be science

- The essentials of science writing: What is science writing?

- 8 steps to writing your first draft

- Two ways to be an inefficient writer

- Work-procrastination: important stuff that keeps us from writing

Preparing tables for research papers

Tables and illustrations are important tools for efficiently communicating information and data contained in your research paper to the readers. They present complex results in a comprehensible and organized manner.

However, it is advisable to use tables and illustrations wisely so as to maximize the impact of your research.They should be organized in an easy-to-understand format to convey the information and findings collected in your research. The tabular information helps the reader identify the theme of the study more readily. Although data tables should be complete,they should not be too complex. Instead of including a large volume of data in a single unwieldy table, it is prudent to use small tables to help readers identify the important information easily.

Here are some points you should consider before drafting the tables in your research paper:

- Finalize the results that are required to be presented in tabular form.

- Include the data or results that are relevant to the main aim of the study without being choosy and including only those results that support your hypothesis.

- Create each table in a lucid manner and style without cluttering it with in-table citations.

- Number the tables in a sequence according to their occurrence in the text.

- Don’t mix tables with figures. Maintain separate numbering systems for tables and figures.

- Create tables in a storytelling manner. Remember that your tables communicate a story to the reader that runs parallel to the text.

- If you are using or reproducing tables from other published articles, obtain permission from the copyright holder (usually the publisher) or/andacknowledge the source.

- Do not repeat the tabular contents in the text again; that will create confusion among readers.

- Use clear and informative text for each table title.

- Take extra care while extending the data in your tables. If you have too many tables, consider using them as appendices or supplementary materials.

- Create tables with sufficient spacing in the layout so that they do not look messy, crowded, or cluttered.

- Do not forget to spell out abbreviations used in the tables, ideally in the footnotes.

For the reader, a research paper that is dense and text-heavy can be tiresome. Conversely, tables not only encapsulate your data lucidly, but also welcome a visual relief for the reader. They add value to the layout of your paper. Besides, and more importantly, reviewers often glance at your tabulated data and illustrations first before delving into the text. Therefore, tables can be the initial draw for a reviewer and deliver a positive impact about your research paper. If you can achieve an optimum balance among your text, tables, and illustrations, it can go a long way toward being published.

Related Posts

The impact of authorship order: decoding conventions and expectations.

Understanding authorship order is essential since it affects academic recognition and reflects research contributions. Author lists are shaped by several standards, such as alphabetical or contribution-based orders, which impact how each contribution is perceived. Acknowledging these principles guarantees equitable crediting and recognizes the variety of responsibilities involved in cooperative scientific projects. How is […]

Importance of an apt title for your research paper

Writing a research paper with innovative and groundbreaking findings might be a difficult task in itself, but a carefully formulated title is also just as important. By its sheer positioning at the top, the title occupies a pristine position in your research paper and readers, reviewers, and editors are inadvertently drawn to it first. This […]

Trump releases his 100 days plan- What for Science?

Electing Donald Trump as the 45th American President will bring about scads of policy reforms, even faster than the people realize. Starting from freezing the employee recruitments to the scrapping of Obamacare initiatives are all on the list! In addition, the breakneck statements and views of Donald Trump on various scientific facts have also […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

Your Guide to Creating Effective Tables and Figures in Research Papers

Research papers are full of data and other information that needs to be effectively illustrated and organized. Without a clear presentation of a study's data, the information will not reach the intended audience and could easily be misunderstood. Clarity of thought and purpose is essential for any kind of research. Using tables and figures to present findings and other data in a research paper can be effective ways to communicate that information to the chosen audience.

When manuscripts are screened, tables and figures can give reviewers and publication editors a quick overview of the findings and key information. After the research paper is published or accepted as a final dissertation, tables and figures will offer the same opportunity for other interested readers. While some readers may not read the entire paper, the tables and figures have the chance to still get the most important parts of your research across to those readers.

However, tables and figures are only valuable within a research paper if they are succinct and informative. Just about any audience—from scientists to the general public—should be able to identify key pieces of information in well-placed and well-organized tables. Figures can help to illustrate ideas and data visually. It is important to remember that tables and figures should not simply be repetitions of data presented in the text. They are not a vehicle for superfluous or repetitious information. Stay focused, stay organized, and you will be able to use tables and figures effectively in your research papers. The following key rules for using tables and figures in research papers will help you do just that.

Check style guides and journal requirements

The first step in deciding how you want to use tables and figures in your research paper is to review the requirements outlined by your chosen style guide or the submission requirements for the journal or publication you will be submitting to. For example, JMIR Publications states that for readability purposes, we encourage authors to include no more than 5 tables and no more than 8 figures per article. They continue to outline that tables should not go beyond the 1-inch margin of a portrait-orientation 8.5"x11" page using 12pt font or they may not be able to be included in your main manuscript because of our PDF sizing.

Consider the reviewers that will be examining your research paper for consistency, clarity, and applicability to a specific publication. If your chosen publication usually has shorter articles with supplemental information provided elsewhere, then you will want to keep the number of tables and figures to a minimum.

According to the Purdue Online Writing Lab (Purdue OWL), the American Psychological Association (APA) states that Data in a table that would require only two or fewer columns and rows should be presented in the text. More complex data is better presented in tabular format. You can avoid unnecessary tables by reviewing the data and deciding if it is simple enough to be included in the text. There is a balance, and the APA guideline above gives a good standard cutoff point for text versus table. Finally, when deciding if you should include a table or a figure, ask yourself is it necessary. Are you including it because you think you should or because you think it will look more professional, or are you including it because it is necessary to articulate the data? Only include tables or figures if they are necessary to articulate the data.

Table formatting

Creating tables is not as difficult as it once was. Most word processing programs have functions that allow you to simply select how many rows and columns you want, and then it builds the structure for you. Whether you create a table in LaTeX , Microsoft Word , Microsoft Excel , or Google Sheets , there are some key features that you will want to include. Tables generally include a legend, title, column titles, and the body of the table.

When deciding what the title of the table should be, think about how you would describe the table's contents in one sentence. There isn't a set length for table titles, and it varies depending on the discipline of the research, but it does need to be specific and clear what the table is presenting. Think of this as a concise topic sentence of the table.

Column titles should be designed in such a way that they simplify the contents of the table. Readers will generally skim the column titles first before getting into the data to prepare their minds for what they are about to see. While the text introducing the table will give a brief overview of what data is being presented, the column titles break that information down into easier-to-understand parts. The Purdue OWL gives a good example of what a table format could look like:

When deciding what your column titles should be, consider the width of the column itself when the data is entered. The heading should be as close to the length of the data as possible. This can be accomplished using standard abbreviations. When using symbols for the data, such as the percentage "%" symbol, place the symbol in the heading, and then you will not use the symbol in each entry, because it is already indicated in the column title.

For the body of the table, consistency is key. Use the same number of decimal places for numbers, keep the alignment the same throughout the table data, and maintain the same unit of measurement throughout each column. When information is changed within the same column, the reader can become confused, and your data may be considered inaccurate.

When creating tables, especially those derived from complex datasets or scanned documents, tools like JPG to Excel converter can be incredibly useful. These tools can automate the extraction of tabular data from images, ensuring accuracy and saving time. By converting image-based data into editable Excel sheets, researchers can easily format, analyze, and integrate the information into their papers. Utilizing such converters can enhance the efficiency of your data management process, making the preparation of tables for your research paper more seamless.

Figures in research papers

Figures can be of many different graphical types, including bar graphs, scatterplots, maps, photos, and more. Compared to tables, figures have a lot more variation and personalization. Depending on the discipline, figures take different forms. Sometimes a photograph is the best choice if you're illustrating spatial relationships or data hiding techniques in images. Sometimes a map is best to illustrate locations that have specific characteristics in an economic study. Carefully consider your reader's perspective and what detail you want them to see.

As with tables, your figures should be numbered sequentially and follow the same guidelines for titles and labels. Depending on your chosen style guide, keep the figure or figure placeholder as close to the text introducing it as possible. Similar to the figure title, any captions should be succinct and clear, and they should be placed directly under the figure.

Using the wrong kind of figure is a common mistake that can affect a reader's experience with your research paper. Carefully consider what type of figure will best describe your point. For example, if you are describing levels of decomposition of different kinds of paper at a certain point in time, then a scatter plot would not be the appropriate depiction of that data; a bar graph would allow you to accurately show decomposition levels of each kind of paper at time "t." The Writing Center of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has a good example of a bar graph offering easy-to-understand information:

If you have taken a figure from another source, such as from a presentation available online, then you will need to make sure to always cite the source. If you've modified the figure in any way, then you will need to say that you adapted the figure from that source. Plagiarism can still happen with figures – and even tables – so be sure to include a citation if needed.

Using the tips above, you can take your research data and give your reader or reviewer a clear perspective on your findings. As The Writing Center recommends, Consider the best way to communicate information to your audience, especially if you plan to use data in the form of numbers, words, or images that will help you construct and support your argument. If you can summarize the data in a couple of sentences, then don't try and expand that information into an unnecessary table or figure. Trying to use a table or figure in such cases only lengthens the paper and can make the tables and figures meaningless instead of informative.

Carefully choose your table and figure style so that they will serve as quick and clear references for your reader to see patterns, relationships, and trends you have discovered in your research. For additional assistance with formatting and requirements, be sure to review your publication or style guide's instructions to ensure success in the review and submission process.

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Need an academic editor before submitting your work?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Turk J Urol

- v.39(Suppl 1); 2013 Sep

How to clearly articulate results and construct tables and figures in a scientific paper?

The writing of the results section of a scientific paper is very important for the readers for clearly understanding of the study. This review summarizes the rules for writing the results section of a scientific paper and describes the use of tables and figures.

Introduction