Insights into How & Why Students Cheat at High Performing Schools

“ A LOT of people cheat and I feel like it would ruin my character and personal standards if I also took part in cheating, but everyone tells me there’s no way I can finish the school year with straight As without cheating. It really makes me upset but I’m honestly contemplating it because colleges can’t see who does and doesn’t cheat. ” – High school student

“Academic dishonesty is any deceitful or unfair act intended to produce a more desirable outcome on an exam, paper, homework assignment, or other assessment of learning.” (Miller, Murdock & Grotwiel, 2017).

Cheating has been a hot topic in the news lately with the unfolding of the college admissions scandal involving affluent parents allegedly using bribery and forgery to help their kids get into selective colleges. Unfortunately, we also see that cheating is common among students in middle schools through graduate schools (Miller, Murdock & Grotwiel, 2017), including the high-performing middle and high schools that Challenge Success has surveyed. To better understand who is cheating in these high schools, how they are cheating, and what is driving this behavior, we looked at recent data from the Challenge Success Student Survey completed in Fall 2018—including 16,054 students from 15 high-performing U.S. high schools (73% public, 27% private). We asked students to self-report their engagement in 12 cheating behaviors during the past month. On each of the items, adapted from a scale developed by McCabe (1999), students could select one of four options: never; once; two to three times; four or more times. We found that 79% of students cheated in some way in the past month.

How Students Cheat & Who Does It

There are two types of cheating that the students we surveyed engage in: (1) cheating collectively and (2) cheating independently. Overall rates of cheating collectively were higher than rates of cheating individually. Examples of cheating collectively include, working on an assignment with others when the instructor asked for individual work, helping someone else cheat on an assessment, and copying from another student during an assessment with that person’s knowledge. Examples of independent cheating include using unpermitted cheat sheets during an assessment, copying from another student during an assessment without their knowledge, or copying material word for word without citing it and turning it in as your own work.

When we looked more closely at who is cheating according to our survey data, we found that 9 th graders were less likely than 10 th , 11 th , and 12 th graders to cheat individually and collectively. This is consistent with other research in the field that shows that cheating tends to increase with grade level (Murdock, Stephens, & Grotewiel, 2016). We also found that male students were more likely to cheat individually than female students. Broader research from the field about cheating by gender has yielded mixed results. Some find that rates for boys are higher than for girls, while others find no difference (McCabe, Treviño & Butterfield, 2001; Murdock, Hale & Weber, 2001; Anderman & Midgley, 2004).

Why Students Cheat

“I think what causes us stress during the school year is the amount of cheating going on around school…Some of my friends and classmates who have siblings or friends that took the classes before in a way have a copy of what the tests will look like. It makes them have a competitive advantage over other people who have no siblings or known friends that took the class before. To have people who have access to these past tests, it creates more stress on students because we have to study more and push ourselves harder.” – High School Student

Why are students cheating at such high rates? Previous research on cheating suggests students may be inclined to cheat and rationalize their behaviors because of various factors including:

- Performance over Mastery: Students may cheat because of the risk of low grades due to worry, pressure on academic performance, or a fixed mindset ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017). School environments perceived by students to be focused on performance goals like grades and test scores over mastery have been associated with behaviors such as cheating (Anderman & Midgley, 2004).

- Peer Relationships/Social Comparison: The increase of social comparisons and competition that many children and adolescents experience in high performing schools or classrooms or the desire to help a friend ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017) may be another factor of choosing to cheat. Students in high-achieving cultures, furthermore, tend to cheat more when they see or perceive their peers cheating (Galloway, 2012).

- Overloaded : Another factor in students cheating is the pressure in high-performing schools to “do it all” which can be influenced by heavy workloads and/or multiple tests on the same day ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017)

- “Cheat or be cheated” rationale: Students may rationalize cheating by blaming the teachers or situation. This often occurs when students see the teacher as uncaring or focused on performance over mastery ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017). Students may rationalize and normalize cheating as the way to succeed in a challenging environment where achievement is paramount (Galloway, 2012).

- Pressure: Students may also cheat because they feel pressure to maintain their status in a success focused community where they see the situation as “cheat or be cheated” ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017).

We see many of these factors reflected in our survey data. Students listed their major sources of stress as grades, tests, finals, or assessments (80% of students) and overall workload and homework (71% of students). We also found that 59% of students feel they have “too much homework,” 75% of students feel “often” or “always” stressed by their schoolwork , 31% of students feel that “many” or “all” of their classes assign homework that helps them learn the material, and 74% worry “quite a bit” or “a lot” about taking assessments while 70% worry the same amount about school assignments.

Reflecting high pressure from within their community, only 51% of students feel they can meet their parents expectations “often” or “always,” 52% of students worry at least a little that if they do not do well in school their friends will not accept them, and 80% of students feel “quite a bit” or “a lot” of pressure to do well in school. Meanwhile, only 33% of students feel “quite” or “very” confident in their ability to cope with stress . Open-ended responses reported by students on our survey reinforce the quantitative data:

“It is hard to do well in classes and become well rounded for applying to college without something giving way… in some cases students cheat. ”

“ I don’t think anyone is having a great time here, when all they’re focusing on is cheating and getting the grade that they want in order to ‘succeed’ in life after high school by going to a great college or university.”

“ Teachers often give very challenging tests that require very large curves to present even reasonable grades and this creates a very stressful atmosphere. Students are often caught cheating because that is often times the only route to getting a decent grade. ”

Quotes like these suggest that there may be a relationship between heavy amounts of homework on top of busy extracurriculars and students feeling that cheating is the only way to get everything done.

What Can Schools Do About It

Schools may find the prevalence of the cheating culture overwhelming—potentially daunted by counteracting the normalization and prevalence of achievement at-all-costs and cheating behaviors. Students themselves, in our survey and in previous research, call for a learning environment where cheating is not an expectation or everyday behavior for getting ahead, and students are held responsible for their behavior (McCabe, 2001).

“ The administration needs to punish students who cheat. The school does not crack down on these kids, and it makes it harder for others to succeed. ”

“ Since I was in 9th grade it feels like our counselors only really care about our class rank and GPA. I am a hard worker but I don’t have the best GPA. Our school focuses too much on grades. This creates pressure on students to cheat just to get a good grade to boost their GPA. Learning has been compromised by a desire for a number that we have been told defines us as people. ”

Schools can work with students to change the prevailing culture of cheating through listening to students about their experiences and perceptions, acknowledging the issue and predominant culture, and collaborating with students to clarify and redefine how and why students learn. Some areas we (and other researchers) recommend that schools can address underlying causes of cheating include:

- Strive for school-wide buy-in for honest academic practices including defining what constitutes cheating and academic dishonesty for students and providing clear consequences for cheating (Galloway, 2012). Further providing open dialogue and discussions with students, parents, and teachers may help students feel that teachers are treating then with respect and fairness (Murdock et al., 2004).

- Educate students on what cheating means in their school community so that cheating is viewed as unacceptable ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017)

- Establish a climate of care and a classroom where it is evident that the teacher cares about student progress, learning, and understanding.

- Emphasize mastery and learning over performance . One strategy is through using formative assessments such as practice exams that can be reviewed in class and homework that can be corrected until students achieve mastery on the concepts ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017).

- Revise assessments and grading policies to allow for redemption and revision.

- Ensure that students are met with “reasonable demands” such as spacing assignments and assessments across days and reduce workload without reducing rigor ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017)

- Teach students time management strategies (e.g. using a planner, breaking tasks into manageable pieces, and how to use resources or ask for help). Schools may even teach parents how to help students organize and manage their work rather than providing them with answers. ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017)

Overall, schools should aim to change student attitudes around integrity through “clear, fair, and consistent” assessments, valuing learning over mastery, reducing comparisons and competition between students, teaching students management and organization skills, and demonstrating care and empathy for students and the pressures that face ( Miller, Murdock & Grotewiel, 2017) .

Anderman, E.M. & Midgley, C. (2004). Changes in self-reported academic cheating across the transition from middle school to high school. Contemporary Educational Psychology , 29(4), 499-517.

Galloway, M. K. (2012). Cheating in advantaged high schools: Prevalence, justifications, and possibilities for change. Ethics & Behavior, 22(5), 378-399.

McCabe, D. (1999). Academic dishonesty among high school students. Adolescence, 34 (136), 681- 687.

McCabe, D. (2001) Cheating: Why students do it and how we can help them stop. American Educator , Winter, 38-43.

McCabe, D. L., Treviño, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2001). Cheating in academic institutions: A decade of research. Ethics & Behavior , 11, 219-232.

Miller, A. D., Murdock, T. B., & Grotewiel, M. M. (2017). Addressing Academic Dishonesty Among the Highest Achievers. Theory Into Practice , 56 (2), 121-128.

Murdock, T., Hale, N., & Weber, M. (2001). Predictors of cheating among early adolescents: Academic and social motivations. Contemporary Educational Psychology , 26, 96-115.

Murdock, T. B., Miller, A., & Kohlhardt, J. (2004). Effects of Classroom Context Variables on High School Students’ Judgments of the Acceptability and Likelihood of Cheating. Journal of Educational Psychology , 96 (4), 765-777.

Murdock, T., Stephens, J., & Grotewiel, M. (2016). Student dishonesty in the face of assessment. In G. Brown and L. Harris (Eds.), Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment (pp. 186-203). London, England: Routledge.

Wangaard, D. B. & J. M. Stephens (2011). Academic integrity: A critical challenge for schools. Excellence & Ethics , Winter 2011.

Interested in learning more about your students’ perceptions of their school experiences? Learn more about the Challenge Success Student Survey here .

Trending Post : 12 Powerful Discussion Strategies to Engage Students

Why Students Cheat on Homework and How to Prevent It

One of the most frustrating aspects of teaching in today’s world is the cheating epidemic. There’s nothing more irritating than getting halfway through grading a large stack of papers only to realize some students cheated on the assignment. There’s really not much point in teachers grading work that has a high likelihood of having been copied or otherwise unethically completed. So. What is a teacher to do? We need to be able to assess students. Why do students cheat on homework, and how can we address it?

Like most new teachers, I learned the hard way over the course of many years of teaching that it is possible to reduce cheating on homework, if not completely prevent it. Here are six suggestions to keep your students honest and to keep yourself sane.

ASSIGN LESS HOMEWORK

One of the reasons students cheat on homework is because they are overwhelmed. I remember vividly what it felt like to be a high school student in honors classes with multiple extracurricular activities on my plate. Other teens have after school jobs to help support their families, and some don’t have a home environment that is conducive to studying.

While cheating is never excusable under any circumstances, it does help to walk a mile in our students’ shoes. If they are consistently making the decision to cheat, it might be time to reduce the amount of homework we are assigning.

I used to give homework every night – especially to my advanced students. I wanted to push them. Instead, I stressed them out. They wanted so badly to be in the Top 10 at graduation that they would do whatever they needed to do in order to complete their assignments on time – even if that meant cheating.

When assigning homework, consider the at-home support, maturity, and outside-of-school commitments involved. Think about the kind of school and home balance you would want for your own children. Go with that.

PROVIDE CLASS TIME

Allowing students time in class to get started on their assignments seems to curb cheating to some extent. When students have class time, they are able to knock out part of the assignment, which leaves less to fret over later. Additionally, it gives them an opportunity to ask questions.

When students are confused while completing assignments at home, they often seek “help” from a friend instead of going in early the next morning to request guidance from the teacher. Often, completing a portion of a homework assignment in class gives students the confidence that they can do it successfully on their own. Plus, it provides the social aspect of learning that many students crave. Instead of fighting cheating outside of class , we can allow students to work in pairs or small groups in class to learn from each other.

Plus, to prevent students from wanting to cheat on homework, we can extend the time we allow them to complete it. Maybe students would work better if they have multiple nights to choose among options on a choice board. Home schedules can be busy, so building in some flexibility to the timeline can help reduce pressure to finish work in a hurry.

GIVE MEANINGFUL WORK

If you find students cheat on homework, they probably lack the vision for how the work is beneficial. It’s important to consider the meaningfulness and valuable of the assignment from students’ perspectives. They need to see how it is relevant to them.

In my class, I’ve learned to assign work that cannot be copied. I’ve never had luck assigning worksheets as homework because even though worksheets have value, it’s generally not obvious to teenagers. It’s nearly impossible to catch cheating on worksheets that have “right or wrong” answers. That’s not to say I don’t use worksheets. I do! But. I use them as in-class station, competition, and practice activities, not homework.

So what are examples of more effective and meaningful types of homework to assign?

- Ask students to complete a reading assignment and respond in writing .

- Have students watch a video clip and answer an oral entrance question.

- Require that students contribute to an online discussion post.

- Assign them a reflection on the day’s lesson in the form of a short project, like a one-pager or a mind map.

As you can see, these options require unique, valuable responses, thereby reducing the opportunity for students to cheat on them. The more open-ended an assignment is, the more invested students need to be to complete it well.

DIFFERENTIATE

Part of giving meaningful work involves accounting for readiness levels. Whenever we can tier assignments or build in choice, the better. A huge cause of cheating is when work is either too easy (and students are bored) or too hard (and they are frustrated). Getting to know our students as learners can help us to provide meaningful differentiation options. Plus, we can ask them!

This is what you need to be able to demonstrate the ability to do. How would you like to show me you can do it?

REDUCE THE POINT VALUE

If you’re sincerely concerned about students cheating on assignments, consider reducing the point value. Reflect on your grading system.

Are homework grades carrying so much weight that students feel the need to cheat in order to maintain an A? In a standards-based system, will the assignment be a key determining factor in whether or not students are proficient with a skill?

Each teacher has to do what works for him or her. In my classroom, homework is worth the least amount out of any category. If I assign something for which I plan on giving completion credit, the point value is even less than it typically would be. Projects, essays, and formal assessments count for much more.

CREATE AN ETHICAL CULTURE

To some extent, this part is out of educators’ hands. Much of the ethical and moral training a student receives comes from home. Still, we can do our best to create a classroom culture in which we continually talk about integrity, responsibility, honor, and the benefits of working hard. What are some specific ways can we do this?

Building Community and Honestly

- Talk to students about what it means to cheat on homework. Explain to them that there are different kinds. Many students are unaware, for instance, that the “divide and conquer (you do the first half, I’ll do the second half, and then we will trade answers)” is cheating.

- As a class, develop expectations and consequences for students who decide to take short cuts.

- Decorate your room with motivational quotes that relate to honesty and doing the right thing.

- Discuss how making a poor decision doesn’t make you a bad person. It is an opportunity to grow.

- Share with students that you care about them and their futures. The assignments you give them are intended to prepare them for success.

- Offer them many different ways to seek help from you if and when they are confused.

- Provide revision opportunities for homework assignments.

- Explain that you partner with their parents and that guardians will be notified if cheating occurs.

- Explore hypothetical situations. What if you have a late night? Let’s pretend you don’t get home until after orchestra and Lego practices. You have three hours of homework to do. You know you can call your friend, Bob, who always has his homework done. How do you handle this situation?

EDUCATE ABOUT PLAGIARISM

Many students don’t realize that plagiarism applies to more than just essays. At the beginning of the school year, teachers have an energized group of students, fresh off of summer break. I’ve always found it’s easiest to motivate my students at this time. I capitalize on this opportunity by beginning with a plagiarism mini unit .

While much of the information we discuss is about writing, I always make sure my students know that homework can be plagiarized. Speeches can be plagiarized. Videos can be plagiarized. Anything can be plagiarized, and the repercussions for stealing someone else’s ideas (even in the form of a simple worksheet) are never worth the time saved by doing so.

In an ideal world, no one would cheat. However, teaching and learning in the 21st century is much different than it was fifty years ago. Cheating? It’s increased. Maybe because of the digital age… the differences in morals and values of our culture… people are busier. Maybe because students don’t see how the school work they are completing relates to their lives.

No matter what the root cause, teachers need to be proactive. We need to know why students feel compelled to cheat on homework and what we can do to help them make learning for beneficial. Personally, I don’t advocate for completely eliminating homework with older students. To me, it has the potential to teach students many lessons both related to school and life. Still, the “right” answer to this issue will be different for each teacher, depending on her community, students, and culture.

STRATEGIES FOR ADDRESSING CHALLENGING BEHAVIORS IN SECONDARY

You are so right about communicating the purpose of the assignment and giving students time in class to do homework. I also use an article of the week on plagiarism. I give students points for the learning – not the doing. It makes all the difference. I tell my students why they need to learn how to do “—” for high school or college or even in life experiences. Since, they get an A or F for the effort, my students are more motivated to give it a try. No effort and they sit in my class to work with me on the assignment. Showing me the effort to learn it — asking me questions about the assignment, getting help from a peer or me, helping a peer are all ways to get full credit for the homework- even if it’s not complete. I also choose one thing from each assignment for the test which is a motivator for learning the material – not just “doing it.” Also, no one is permitted to earn a D or F on a test. Any student earning an F or D on a test is then required to do a project over the weekend or at lunch or after school with me. All of this reinforces the idea – learning is what is the goal. Giving students options to show their learning is also important. Cheating is greatly reduced when the goal is to learn and not simply earn the grade.

Thanks for sharing your unique approaches, Sandra! Learning is definitely the goal, and getting students to own their learning is key.

Comments are closed.

Get the latest in your inbox!

Cheating in School: Facts, Consequences & Prevention

- Kids have programmed answer sheets into their iPods or recorded course materials into their MP3s and played them back during exams.

- Students have text-messaged test questions (or used their camera phones to picture-message tests) to friends outside the classroom.

- When essays are assigned, some students simply cut and paste text from websites directly into their papers.

- Some students prep for pop quizzes by inputting math formulas or history dates into their programmable calculators.

- Students can buy term papers from a growing number of online “paper mills,” such as schoolsucks.com, for up to $10 a page.

In a recent survey of 18,000 students at 61 middle and high schools:

- 66% admitted to cheating on exams,

- 80% said they had let someone copy their homework, and

- 58% said they had committed plagiarism.

Our society seems to promote that you should do whatever it takes to win or succeed. Children don’t like to lose. Our culture appears to say that it is acceptable to step on others as you climb ahead. Some parents have contributed to the problem by not focusing their attention on instilling positive values – such as honesty, doing your best, and integrity – and instead pressuring their children to excel. Some parents are afraid that their child won’t have a good job or life if they don’t get to the best college, which requires the best grades. Nearly one-third of teens and 25% of tweens say that their parents push them too hard academically, according to a recent national survey commissioned by Family Circle . Additionally, when kids see other kids cheating and not getting caught, it makes them question the importance of honesty. If the cheaters get better grades, an honest youth can feel frustrated.

Consequences of Cheating

The consequences of cheating can be hard for a tween or teen to understand. Without the ability to see the long-term effects, children may feel that the pros of cheating (good grades) outweigh any negatives. That’s why it’s important for parents and teachers to explain the consequences of cheating, such as:

- Cheating lowers your self-respect and confidence. And if others see you cheating, you will lose their respect and trust.

- Unfortunately, cheating is usually not a one-time thing. Once the threshold of cheating is crossed, youth may find it easier to continue cheating more often, or to be dishonest in other situations in life. Students who cheat lose an element of personal integrity that is difficult to recapture. It damages a child’s self-image.

- Students who cheat are wasting their time in school. Most learning builds on itself. A child must first learn one concept so that they are prepared for the next lesson. If they don’t learn the basic concept, they have set themselves up to either continue failing or cheating.

- If you are caught, you could fail the course, be expelled, and gain a bad reputation with your teachers and peers.

- When you are hired by future employers based on the idea that you received good grades in a certain subject, you will not be able to solve problems, offer ideas, or maintain the workload in that subject area. A teen is only cheating themselves out of learning and discovering how good they could really do.

- students who repeatedly plagiarize Internet content lose their ability to think critically and to distinguish legitimate sources from those that are not.

- students who cheat in high school are more likely to do the same in college, and college cheaters, in turn, are more likely to behave dishonestly on the job.

Ways Schools Can Prevent Cheating

Schools are trying to fight the cheating epidemic. Here are some ways they can be successful:

- Set up an Internet firewall so students can’t exchange e-mail and instant messages that might contain exam questions or answers.

- Require students to submit their papers to websites like TurnItIn.com. For about $1 per pupil per year the company analyzes writing assignments for more than 5,000 middle and high schools, comparing a digital copy of a student’s composition to a database of books, journals, the Internet and previously submitted papers. Students and teachers get instant feedback with suspect material highlighted. Of the 100,000 papers TurnItIn.com checks daily, about a third contain unoriginal, unsourced “cut-and-paste” content, from a few sentences to a paragraph or even more.

- Create a school honor code that clearly spells out ethical behavior and defines academic misconduct.

- Establish specific penalties for those who plagiarize or cheat on exams, or those who fail to report classmates who do.

Complicating matters is that schools are sometimes reluctant to bring cheaters to justice for two main reasons. First, accusing a student usually results in very angry parents and sometimes lawsuits. Second, the federal government’s No Child Left Behind policy penalizes schools whose students perform poorly on standardized tests by forcing them to close or replace staff.

Ways Parents Can Prevent Cheating

Parents need to provide guidance and support to their teens to keep them from cheating. Education experts have this advice:

- Talk to your kids about the importance of ethical behavior and how cheating will hurt them in the long term (use the consequences listed above). Point out negative examples when you see them and explain the problems those people will suffer.

- Be honest with yourself about whether you might be putting too much pressure on your children to succeed at school. Explain to your kids that ambition is fine, but honesty and integrity are more important than academic success achieved through deceit.

- Be a good role model. If your child sees you cheat at board games or other small things, you are giving them the message that cheating is acceptable.

- Check your computer history to see if your teens are using websites that sell written papers. If you see anything suspicious, talk to them about it.

- Stay involved in your teen’s academic life. Review their homework and read your teens’ essays to see how they are doing.

- develop an honor code.

- create ways for kids to identify cheaters anonymously so they don’t fear retaliation from others.

- include lessons on proper paraphrasing and how to cite Internet sources.

- have teachers develop multiple versions of tests to deter students from sharing answers via text messaging.

Final thoughts…

Schools and parents must both actively discourage cheating if we have any hope of stopping this epidemic. Studies show that America is lagging behind other countries in academics. Our nation will not be globally competitive if we raise a generation of undereducated cheaters. Parents and teachers should emphasize the importance of integrity.

Share this:

I’m wondering if this is based on anecdotes or research? Could you let me know?

All of our articles are researched and based on scientific studies or advice from experts in the appropriate field. The article you’re referencing did mention two different study results. However, the article is 10 years old, so all of the information is outdated.

Pingback: Cheating and Technology | Life Long Learners Club

That is a good lesson for all of schools, parents and students. it reminds us the ways cheating can be avoided and what is expected if not done so. Thanks for your contribution

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from middle earth.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Advertisement

Supported by

Cheating Fears Over Chatbots Were Overblown, New Research Suggests

A.I. tools like ChatGPT did not boost the frequency of cheating in high schools, Stanford researchers say.

- Share full article

By Natasha Singer

Natasha Singer writes about education technology.

Last December, as high school and college students began trying out a new A.I. chatbot called ChatGPT to manufacture writing assignments, fears of mass cheating spread across the United States.

To hinder bot-enabled plagiarism, some large public schools districts — including those in Los Angeles , Seattle and New York City — quickly blocked ChatGPT on school-issued laptops and school Wi-Fi.

But the alarm may have been overblown — at least in high schools.

According to new research from Stanford University, the popularization of A.I. chatbots has not boosted overall cheating rates in schools. In surveys this year of more than 40 U.S. high schools, some 60 to 70 percent of students said they had recently engaged in cheating — about the same percent as in previous years, Stanford education researchers said .

“There was a panic that these A.I. models will allow a whole new way of doing something that could be construed as cheating,” said Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Education who has surveyed high school students for more than a decade through an education nonprofit she co-founded. But “we’re just not seeing the change in the data.”

ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI in San Francisco, began to capture the public imagination late last year with its ability to fabricate human-sounding essays and emails. Almost immediately, classroom technology boosters started promising that A.I. tools like ChatGPT would revolutionize education. And critics began warning that such tools — which liberally make stuff up — would enable widespread cheating, and amplify misinformation, in schools.

How much, if anything, have you heard about ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence (A.I.) program used to create text?

Do you think it’s acceptable for students to use ChatGPT for … ?

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Homework – Top 3 Pros and Cons

Pro/Con Arguments | Discussion Questions | Take Action | Sources | More Debates

From dioramas to book reports, from algebraic word problems to research projects, whether students should be given homework, as well as the type and amount of homework, has been debated for over a century. [ 1 ]

While we are unsure who invented homework, we do know that the word “homework” dates back to ancient Rome. Pliny the Younger asked his followers to practice their speeches at home. Memorization exercises as homework continued through the Middle Ages and Enlightenment by monks and other scholars. [ 45 ]

In the 19th century, German students of the Volksschulen or “People’s Schools” were given assignments to complete outside of the school day. This concept of homework quickly spread across Europe and was brought to the United States by Horace Mann , who encountered the idea in Prussia. [ 45 ]

In the early 1900s, progressive education theorists, championed by the magazine Ladies’ Home Journal , decried homework’s negative impact on children’s physical and mental health, leading California to ban homework for students under 15 from 1901 until 1917. In the 1930s, homework was portrayed as child labor, which was newly illegal, but the prevailing argument was that kids needed time to do household chores. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 45 ] [ 46 ]

Public opinion swayed again in favor of homework in the 1950s due to concerns about keeping up with the Soviet Union’s technological advances during the Cold War . And, in 1986, the US government included homework as an educational quality boosting tool. [ 3 ] [ 45 ]

A 2014 study found kindergarteners to fifth graders averaged 2.9 hours of homework per week, sixth to eighth graders 3.2 hours per teacher, and ninth to twelfth graders 3.5 hours per teacher. A 2014-2019 study found that teens spent about an hour a day on homework. [ 4 ] [ 44 ]

Beginning in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic complicated the very idea of homework as students were schooling remotely and many were doing all school work from home. Washington Post journalist Valerie Strauss asked, “Does homework work when kids are learning all day at home?” While students were mostly back in school buildings in fall 2021, the question remains of how effective homework is as an educational tool. [ 47 ]

Is Homework Beneficial?

Pro 1 Homework improves student achievement. Studies have shown that homework improved student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college. Research published in the High School Journal indicated that students who spent between 31 and 90 minutes each day on homework “scored about 40 points higher on the SAT-Mathematics subtest than their peers, who reported spending no time on homework each day, on average.” [ 6 ] Students in classes that were assigned homework outperformed 69% of students who didn’t have homework on both standardized tests and grades. A majority of studies on homework’s impact – 64% in one meta-study and 72% in another – showed that take-home assignments were effective at improving academic achievement. [ 7 ] [ 8 ] Research by the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) concluded that increased homework led to better GPAs and higher probability of college attendance for high school boys. In fact, boys who attended college did more than three hours of additional homework per week in high school. [ 10 ] Read More

Pro 2 Homework helps to reinforce classroom learning, while developing good study habits and life skills. Students typically retain only 50% of the information teachers provide in class, and they need to apply that information in order to truly learn it. Abby Freireich and Brian Platzer, co-founders of Teachers Who Tutor NYC, explained, “at-home assignments help students learn the material taught in class. Students require independent practice to internalize new concepts… [And] these assignments can provide valuable data for teachers about how well students understand the curriculum.” [ 11 ] [ 49 ] Elementary school students who were taught “strategies to organize and complete homework,” such as prioritizing homework activities, collecting study materials, note-taking, and following directions, showed increased grades and more positive comments on report cards. [ 17 ] Research by the City University of New York noted that “students who engage in self-regulatory processes while completing homework,” such as goal-setting, time management, and remaining focused, “are generally more motivated and are higher achievers than those who do not use these processes.” [ 18 ] Homework also helps students develop key skills that they’ll use throughout their lives: accountability, autonomy, discipline, time management, self-direction, critical thinking, and independent problem-solving. Freireich and Platzer noted that “homework helps students acquire the skills needed to plan, organize, and complete their work.” [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ] [ 49 ] Read More

Pro 3 Homework allows parents to be involved with children’s learning. Thanks to take-home assignments, parents are able to track what their children are learning at school as well as their academic strengths and weaknesses. [ 12 ] Data from a nationwide sample of elementary school students show that parental involvement in homework can improve class performance, especially among economically disadvantaged African-American and Hispanic students. [ 20 ] Research from Johns Hopkins University found that an interactive homework process known as TIPS (Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork) improves student achievement: “Students in the TIPS group earned significantly higher report card grades after 18 weeks (1 TIPS assignment per week) than did non-TIPS students.” [ 21 ] Homework can also help clue parents in to the existence of any learning disabilities their children may have, allowing them to get help and adjust learning strategies as needed. Duke University Professor Harris Cooper noted, “Two parents once told me they refused to believe their child had a learning disability until homework revealed it to them.” [ 12 ] Read More

Con 1 Too much homework can be harmful. A poll of California high school students found that 59% thought they had too much homework. 82% of respondents said that they were “often or always stressed by schoolwork.” High-achieving high school students said too much homework leads to sleep deprivation and other health problems such as headaches, exhaustion, weight loss, and stomach problems. [ 24 ] [ 28 ] [ 29 ] Alfie Kohn, an education and parenting expert, said, “Kids should have a chance to just be kids… it’s absurd to insist that children must be engaged in constructive activities right up until their heads hit the pillow.” [ 27 ] Emmy Kang, a mental health counselor, explained, “More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies.” [ 48 ] Excessive homework can also lead to cheating: 90% of middle school students and 67% of high school students admit to copying someone else’s homework, and 43% of college students engaged in “unauthorized collaboration” on out-of-class assignments. Even parents take shortcuts on homework: 43% of those surveyed admitted to having completed a child’s assignment for them. [ 30 ] [ 31 ] [ 32 ] Read More

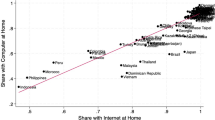

Con 2 Homework exacerbates the digital divide or homework gap. Kiara Taylor, financial expert, defined the digital divide as “the gap between demographics and regions that have access to modern information and communications technology and those that don’t. Though the term now encompasses the technical and financial ability to utilize available technology—along with access (or a lack of access) to the Internet—the gap it refers to is constantly shifting with the development of technology.” For students, this is often called the homework gap. [ 50 ] [ 51 ] 30% (about 15 to 16 million) public school students either did not have an adequate internet connection or an appropriate device, or both, for distance learning. Completing homework for these students is more complicated (having to find a safe place with an internet connection, or borrowing a laptop, for example) or impossible. [ 51 ] A Hispanic Heritage Foundation study found that 96.5% of students across the country needed to use the internet for homework, and nearly half reported they were sometimes unable to complete their homework due to lack of access to the internet or a computer, which often resulted in lower grades. [ 37 ] [ 38 ] One study concluded that homework increases social inequality because it “potentially serves as a mechanism to further advantage those students who already experience some privilege in the school system while further disadvantaging those who may already be in a marginalized position.” [ 39 ] Read More

Con 3 Homework does not help younger students, and may not help high school students. We’ve known for a while that homework does not help elementary students. A 2006 study found that “homework had no association with achievement gains” when measured by standardized tests results or grades. [ 7 ] Fourth grade students who did no homework got roughly the same score on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) math exam as those who did 30 minutes of homework a night. Students who did 45 minutes or more of homework a night actually did worse. [ 41 ] Temple University professor Kathryn Hirsh-Pasek said that homework is not the most effective tool for young learners to apply new information: “They’re learning way more important skills when they’re not doing their homework.” [ 42 ] In fact, homework may not be helpful at the high school level either. Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth, stated, “I interviewed high school teachers who completely stopped giving homework and there was no downside, it was all upside.” He explains, “just because the same kids who get more homework do a little better on tests, doesn’t mean the homework made that happen.” [ 52 ] Read More

Discussion Questions

1. Is homework beneficial? Consider the study data, your personal experience, and other types of information. Explain your answer(s).

2. If homework were banned, what other educational strategies would help students learn classroom material? Explain your answer(s).

3. How has homework been helpful to you personally? How has homework been unhelpful to you personally? Make carefully considered lists for both sides.

Take Action

1. Examine an argument in favor of quality homework assignments from Janine Bempechat.

2. Explore Oxford Learning’s infographic on the effects of homework on students.

3. Consider Joseph Lathan’s argument that homework promotes inequality .

4. Consider how you felt about the issue before reading this article. After reading the pros and cons on this topic, has your thinking changed? If so, how? List two to three ways. If your thoughts have not changed, list two to three ways your better understanding of the “other side of the issue” now helps you better argue your position.

5. Push for the position and policies you support by writing US national senators and representatives .

| 1. | Tom Loveless, “Homework in America: Part II of the 2014 Brown Center Report of American Education,” brookings.edu, Mar. 18, 2014 | |

| 2. | Edward Bok, “A National Crime at the Feet of American Parents,” , Jan. 1900 | |

| 3. | Tim Walker, “The Great Homework Debate: What’s Getting Lost in the Hype,” neatoday.org, Sep. 23, 2015 | |

| 4. | University of Phoenix College of Education, “Homework Anxiety: Survey Reveals How Much Homework K-12 Students Are Assigned and Why Teachers Deem It Beneficial,” phoenix.edu, Feb. 24, 2014 | |

| 5. | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “PISA in Focus No. 46: Does Homework Perpetuate Inequities in Education?,” oecd.org, Dec. 2014 | |

| 6. | Adam V. Maltese, Robert H. Tai, and Xitao Fan, “When is Homework Worth the Time?: Evaluating the Association between Homework and Achievement in High School Science and Math,” , 2012 | |

| 7. | Harris Cooper, Jorgianne Civey Robinson, and Erika A. Patall, “Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Researcher, 1987-2003,” , 2006 | |

| 8. | Gökhan Bas, Cihad Sentürk, and Fatih Mehmet Cigerci, “Homework and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Review of Research,” , 2017 | |

| 9. | Huiyong Fan, Jianzhong Xu, Zhihui Cai, Jinbo He, and Xitao Fan, “Homework and Students’ Achievement in Math and Science: A 30-Year Meta-Analysis, 1986-2015,” , 2017 | |

| 10. | Charlene Marie Kalenkoski and Sabrina Wulff Pabilonia, “Does High School Homework Increase Academic Achievement?,” iza.og, Apr. 2014 | |

| 11. | Ron Kurtus, “Purpose of Homework,” school-for-champions.com, July 8, 2012 | |

| 12. | Harris Cooper, “Yes, Teachers Should Give Homework – The Benefits Are Many,” newsobserver.com, Sep. 2, 2016 | |

| 13. | Tammi A. Minke, “Types of Homework and Their Effect on Student Achievement,” repository.stcloudstate.edu, 2017 | |

| 14. | LakkshyaEducation.com, “How Does Homework Help Students: Suggestions From Experts,” LakkshyaEducation.com (accessed Aug. 29, 2018) | |

| 15. | University of Montreal, “Do Kids Benefit from Homework?,” teaching.monster.com (accessed Aug. 30, 2018) | |

| 16. | Glenda Faye Pryor-Johnson, “Why Homework Is Actually Good for Kids,” memphisparent.com, Feb. 1, 2012 | |

| 17. | Joan M. Shepard, “Developing Responsibility for Completing and Handing in Daily Homework Assignments for Students in Grades Three, Four, and Five,” eric.ed.gov, 1999 | |

| 18. | Darshanand Ramdass and Barry J. Zimmerman, “Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework,” , 2011 | |

| 19. | US Department of Education, “Let’s Do Homework!,” ed.gov (accessed Aug. 29, 2018) | |

| 20. | Loretta Waldman, “Sociologist Upends Notions about Parental Help with Homework,” phys.org, Apr. 12, 2014 | |

| 21. | Frances L. Van Voorhis, “Reflecting on the Homework Ritual: Assignments and Designs,” , June 2010 | |

| 22. | Roel J. F. J. Aries and Sofie J. Cabus, “Parental Homework Involvement Improves Test Scores? A Review of the Literature,” , June 2015 | |

| 23. | Jamie Ballard, “40% of People Say Elementary School Students Have Too Much Homework,” yougov.com, July 31, 2018 | |

| 24. | Stanford University, “Stanford Survey of Adolescent School Experiences Report: Mira Costa High School, Winter 2017,” stanford.edu, 2017 | |

| 25. | Cathy Vatterott, “Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs,” ascd.org, 2009 | |

| 26. | End the Race, “Homework: You Can Make a Difference,” racetonowhere.com (accessed Aug. 24, 2018) | |

| 27. | Elissa Strauss, “Opinion: Your Kid Is Right, Homework Is Pointless. Here’s What You Should Do Instead.,” cnn.com, Jan. 28, 2020 | |

| 28. | Jeanne Fratello, “Survey: Homework Is Biggest Source of Stress for Mira Costa Students,” digmb.com, Dec. 15, 2017 | |

| 29. | Clifton B. Parker, “Stanford Research Shows Pitfalls of Homework,” stanford.edu, Mar. 10, 2014 | |

| 30. | AdCouncil, “Cheating Is a Personal Foul: Academic Cheating Background,” glass-castle.com (accessed Aug. 16, 2018) | |

| 31. | Jeffrey R. Young, “High-Tech Cheating Abounds, and Professors Bear Some Blame,” chronicle.com, Mar. 28, 2010 | |

| 32. | Robin McClure, “Do You Do Your Child’s Homework?,” verywellfamily.com, Mar. 14, 2018 | |

| 33. | Robert M. Pressman, David B. Sugarman, Melissa L. Nemon, Jennifer, Desjarlais, Judith A. Owens, and Allison Schettini-Evans, “Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background,” , 2015 | |

| 34. | Heather Koball and Yang Jiang, “Basic Facts about Low-Income Children,” nccp.org, Jan. 2018 | |

| 35. | Meagan McGovern, “Homework Is for Rich Kids,” huffingtonpost.com, Sep. 2, 2016 | |

| 36. | H. Richard Milner IV, “Not All Students Have Access to Homework Help,” nytimes.com, Nov. 13, 2014 | |

| 37. | Claire McLaughlin, “The Homework Gap: The ‘Cruelest Part of the Digital Divide’,” neatoday.org, Apr. 20, 2016 | |

| 38. | Doug Levin, “This Evening’s Homework Requires the Use of the Internet,” edtechstrategies.com, May 1, 2015 | |

| 39. | Amy Lutz and Lakshmi Jayaram, “Getting the Homework Done: Social Class and Parents’ Relationship to Homework,” , June 2015 | |

| 40. | Sandra L. Hofferth and John F. Sandberg, “How American Children Spend Their Time,” psc.isr.umich.edu, Apr. 17, 2000 | |

| 41. | Alfie Kohn, “Does Homework Improve Learning?,” alfiekohn.org, 2006 | |

| 42. | Patrick A. Coleman, “Elementary School Homework Probably Isn’t Good for Kids,” fatherly.com, Feb. 8, 2018 | |

| 43. | Valerie Strauss, “Why This Superintendent Is Banning Homework – and Asking Kids to Read Instead,” washingtonpost.com, July 17, 2017 | |

| 44. | Pew Research Center, “The Way U.S. Teens Spend Their Time Is Changing, but Differences between Boys and Girls Persist,” pewresearch.org, Feb. 20, 2019 | |

| 45. | ThroughEducation, “The History of Homework: Why Was It Invented and Who Was behind It?,” , Feb. 14, 2020 | |

| 46. | History, “Why Homework Was Banned,” (accessed Feb. 24, 2022) | |

| 47. | Valerie Strauss, “Does Homework Work When Kids Are Learning All Day at Home?,” , Sep. 2, 2020 | |

| 48. | Sara M Moniuszko, “Is It Time to Get Rid of Homework? Mental Health Experts Weigh In,” , Aug. 17, 2021 | |

| 49. | Abby Freireich and Brian Platzer, “The Worsening Homework Problem,” , Apr. 13, 2021 | |

| 50. | Kiara Taylor, “Digital Divide,” , Feb. 12, 2022 | |

| 51. | Marguerite Reardon, “The Digital Divide Has Left Millions of School Kids Behind,” , May 5, 2021 | |

| 52. | Rachel Paula Abrahamson, “Why More and More Teachers Are Joining the Anti-Homework Movement,” , Sep. 10, 2021 |

More School Debate Topics

Should K-12 Students Dissect Animals in Science Classrooms? – Proponents say dissecting real animals is a better learning experience. Opponents say the practice is bad for the environment.

Should Students Have to Wear School Uniforms? – Proponents say uniforms may increase student safety. Opponents say uniforms restrict expression.

Should Corporal Punishment Be Used in K-12 Schools? – Proponents say corporal punishment is an appropriate discipline. Opponents say it inflicts long-lasting physical and mental harm on students.

ProCon/Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 325 N. LaSalle Street, Suite 200 Chicago, Illinois 60654 USA

Natalie Leppard Managing Editor [email protected]

© 2023 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved

- Social Media

- Death Penalty

- School Uniforms

- Video Games

- Animal Testing

- Gun Control

- Banned Books

- Teachers’ Corner

Cite This Page

ProCon.org is the institutional or organization author for all ProCon.org pages. Proper citation depends on your preferred or required style manual. Below are the proper citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order): the Modern Language Association Style Manual (MLA), the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago), the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA), and Kate Turabian's A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (Turabian). Here are the proper bibliographic citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order):

[Editor's Note: The APA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

[Editor’s Note: The MLA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

- Our Mission

8 Ways to Reduce Student Cheating

Clarity about learning objectives and questions that focus on the thinking process can reduce the chance that students will cheat.

How can I prevent students from cheating on tests and exams?

The pandemic has made this question even more frequent, since many educators are concerned about the quality of learning and the possibility of cheating. Yet, it’s always been a common question among educators.

There’s a flaw in this question, though: It assumes that students want to cheat and will cheat. It also is reactive instead of preventive. My advice and coaching, as a discipline-based education researcher in science, has always been to avoid Band-Aid fixes and solve the root of the problem. I encourage teachers and professors to reflect on two questions:

- Why do students cheat?

- How can we, as educators, create a culture that eliminates the desire to cheat?

To eliminate the temptation of cheating, we need to adopt strategies that reduce anxiety about tests and exams, increase clarity of learning expectations and students’ learning progress, and emphasize the process of learning. We want students to be relaxed with tests and exams and see them as nothing more than an opportunity to demonstrate their current knowledge and skills.

8 Strategies to Change Class Structure and Shift Students’ Perspectives

1. Change your language: Sometimes, unintentionally, our language and behavior reinforce an emphasis on correct answers and grades. During instruction, try to use more open-ended questions that begin with “Why” or “How.” Emphasize process instead of final, definitive answers.

As a science, technology, engineering, and math educator, I have students explain how they solved the problem, and I assign more points on assessments for showing the thinking process and problem-solving. I resist answering students when they ask for a correct answer. Instead, I reply with a question to encourage them to think through the problem.

2. Constructive alignment: The alignment of learning objectives, instruction, and assessment is critical to reduce cheating. Learning objectives provide clarity of the expectations. When students know that the learning objectives are representative of the exam, they do not have as much test anxiety about the unknown. They can better prepare for the assessment.

3. Frequent low-stakes assessments: Frequent low-stakes assessments reduce the anxiety of a heavily weighted test or exam, and they also provide timely feedback to the student about their learning, which brings clarity and again reduces the unknown. I encourage improvement in my courses. I will replace any low-stakes assessment with their test or exam grade, if they demonstrate improvement. This creates a culture in which students can be rewarded for their growth and learning from mistakes.

4. Diagnostic tests: One week before a large unit test in my course, students independently complete a diagnostic test. They review the diagnostic in groups using a specific protocol. They determine the correct answer, what made the problem difficult, what was essential to know, and how they could better study or prepare for similar questions. At no point do I provide correct answers. Students love brainstorming study strategies with their peers. They then have a week to study and seek further guidance.

5. Test design: There is so much cognitive processing that goes on during a test, and much of it is not related to the actual content. Let students know the structure and format in advance. Use a cover sheet that has a cartoon or other funny, topic-related joke to activate dopamine boosters to calm students. I include mindfulness prompts to reduce anxiety and remind students to break problems down into smaller steps.

Additionally, line dividers between questions, rubrics for point breakdowns, clearly defined places to write answers and show work, and plenty of spacing between questions are all formatting structures that help reduce the cognitive load on students. Minimal effort should be spent trying to figure out how to take the test.

6. Question design: We can ask questions that eliminate a single definite answer and reinforce the process of learning. Ask questions that focus on students’ problem-solving or thinking process. Another option is to use creation-style questions. Ask students to explain an example or create a scenario with certain criteria. I also give a problem fully solved, and students analyze the response and justify their analysis with evidence. If students know that questions are more about their individual thinking, they will respect the assessment process more.

7. Review and reflect with exam wrappers: Emphasize the process of learning by explicitly teaching students to reflect on their learning. Using exam wrappers, which are guides with reflective questions, will help students identify their performance and strategies to improve. It’s not enough for students to know what their mistakes were; they need to understand why they made these mistakes.

8. Metacognitive check-ins: After the exam wrapper, students answer four questions. First, they identify their strengths in the course; second, they note their areas of improvement; and third, they describe actions to improve and change. The fourth question empowers them to think about how they can advocate for themselves and seek help from their teacher. I have student conferences in which we discuss the four questions. This reduces the anxiety of talking with a teacher and not knowing what to talk about.

'I Cheated All Throughout High School'

A teacher gets inside the mind of a serial cheater—and is dismayed by what she learns.

Sixty to 70 percent of high-school students report they have cheated. Ninety percent of students admit to having copied another student’s homework. Why is academic dishonesty so widespread? I wrote an article earlier this month that placed most of the blame on classroom culture. Currently, teachers assess students’ ability to reproduce examples and mimic lessons rather than display mastery of a concept. This is a misguided approach to learning, and it encourages students to cheat.

I specifically avoided a discussion of the question of student ethics and character in my article, not because I wanted to exonerate students from their share of the blame, but because I hoped to focus on pedagogy’s role in academic dishonesty. But just when I thought I had succeeded in divorcing character from practice for the sake of discussion, the folly of my strategy was made shockingly clear.

The day the article was published, I received an email from a college student who wanted to provide his perspective on the cheating question. I had naively assumed that my readers and my students were operating from the same ethical starting place: that cheating is wrong. How mistaken I was. Here’s a condensed version of his letter:

I cheated all throughout high school. Not only that, but I graduated as a valedictorian, National AP Scholar, Editor-in-Chief of the school newspaper, and I was accepted into the honors program at [school withheld]. To most educators, my true story is a disgrace to the system; I'm the one who got away. Now, I was talented enough in my cheating to be mostly hailed as one of the smartest and most ambitious students in my graduating class. But the one time I was caught cast a chilling shadow over my school, a shadow that briefly illuminated the overwhelming extent of cheating in my school, a shadow that no educator was then willing to confront. I have thought about that episode literally every day since it happened, and from those thoughts I have come to terms with my philosophy on cheating and how that fits into my greater perspective on education. It boils down to this: we are told that cheating is wrong because we are attempting to earn a grade that we do not deserve. A grade earned by cheating is not a grade reflective of our true achievement. But my contention uses identical reasoning. I cheated because the grade I would have otherwise been given was not reflective of my true learning. I never cheated in a subject that I did not learn on my own terms. That is supported by my performance in AP testing. I took 9 AP tests in high school, scoring 5s on all of them except the one I self-studied for, on which I earned a 4. Never did I cheat on any of those tests, because I felt that they were fair representations of my learning. But in AP Biology, I cheated on literally every in-class test. The curriculum and test techniques of my absolutely atrocious AP Biology class were not fair representations of my knowledge. I felt cheated of the education I deserved, and thus to earn the grade I knew I deserved, I had to cheat the system. This is only one example. I also cheated throughout physics, introduction to statistics, Spanish, chemistry, and so on. But never did I cheat a subject that I did not learn on my own terms. While most of my fellow cheaters, with whom I often colluded, may not have philosophized their cheating as deeply as I have, they intuitively followed the same reasoning. They knew that the classes they were attending were largely not adequately teaching them. And most of them went on to attend prestigious universities, majoring in the very fields they shamelessly cheated through in high school. This message is largely for my own good, to finally externalize these thoughts for another human being. But if you would like to investigate further this idea of principled cheating, as I call it, I would love to assist you with your journalism. Thank you for reading.

This student felt justified—even ethically obligated —to cheat when he felt he had been denied a good education. His teachers, he argued, had cheated him out of the education he deserved and promulgated the very system I blamed for the rise of academic dishonesty. He’d responded by cheating right back in retaliation. Most journalists are thrilled when evidence comes to light that supports their argument. I, however, was devastated. It’s one thing to read the statistics on cheating, but it was quite another to be faced a real-life example of a student cheater.

Recommended Reading

The Average Guy Who Spent 6,003 Hours Trying to Be a Professional Golfer

This Is What Life Without Retirement Savings Looks Like

The Dangers of Distracted Parenting

This student’s reasoning reveals more than a symptom of pedagogical shortcomings. Whereas I sought to accept some culpability for the role I have played in an educational system that fosters cheating, this student sought to transfer the blame for his own ethical transgressions on others. He chose to cheat, and rather than accept his part in that act, he blames his ethical transgressions on his teachers.

In a subsequent email exchange, the student elaborated, “It should be expected that when a student goes to school, he or she enters a social contract with the teacher, one that demands teacher expertise, devotion, and instructional talent in exchange for the student's disciplined loyalty and commitment.” I agree with his premise that education is a social contract. The problem is, though, that he does not acknowledge his own role in this contract. The teachers and administrators who heaped accolades on this student’s shoulders, wrote the letters of recommendation that secured his admission to a top university, and placed their faith in his intelligence and character deserved more. When faced with his end of the contract, this student chose his own individual success and misguided sense of justice over the duty he owed his classmates, teachers, and parents. Most teachers, even those perpetuating a flawed system of carrot-and-stick grading and high-stakes assessments, take their end of the contract seriously, and many teachers give that contract the last full measure of their devotion. To receive this letter in return for that devotion was devastating, at least for me.

At the very least, I would hope this student would use all that intelligence and resourcefulness he applied to his cheating to seek out avenues for change. Rather than resort to “principled cheating,” this student could have made his life his argument . He could have followed in the truly principled footsteps of education activist Nikhil Goyal , who began fighting for the education he felt he deserved while he was still a teenager, and by the time he was 18, had published his first book on education reform and identified as a future Secretary of Education by the Washington Post . Goyal continues to work to make our schools a better place for the children of tomorrow, while the author of this letter and his “fellow cheaters” have graduated to a world of their own design, in which they take what they feel they deserve and give nothing back in return.

This student sought me out in order to assuage his conscience and pay penance to the teachers he deceived. While I am willing to take responsibility for my part in perpetuating the circumstances that made his cheating profitable, I am not willing to abandon the basic tenets of the teacher-student contract. I am, however, willing to re-define our terms. I will continue to re-assess my own practices and work to improve education through my writing and my teaching if the author of this letter agrees to make good on the trust his teachers placed in him when they met him at the schoolhouse door.

About the Author

More Stories

The Children Being Denied Due Process

How Design Thinking Became a Buzzword at School

Advertisement

Academic dishonesty when doing homework: How digital technologies are put to bad use in secondary schools

- Open access

- Published: 23 July 2022

- Volume 28 , pages 1251–1271, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Juliette C. Désiron ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3074-9018 1 &

- Dominik Petko ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1569-1302 1

7151 Accesses

5 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

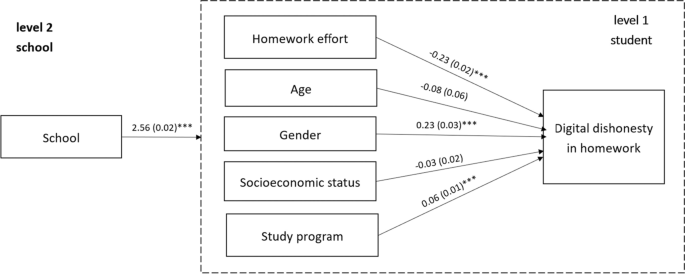

The growth in digital technologies in recent decades has offered many opportunities to support students’ learning and homework completion. However, it has also contributed to expanding the field of possibilities concerning homework avoidance. Although studies have investigated the factors of academic dishonesty, the focus has often been on college students and formal assessments. The present study aimed to determine what predicts homework avoidance using digital resources and whether engaging in these practices is another predictor of test performance. To address these questions, we analyzed data from the Program for International Student Assessment 2018 survey, which contained additional questionnaires addressing this issue, for the Swiss students. The results showed that about half of the students engaged in one kind or another of digitally-supported practices for homework avoidance at least once or twice a week. Students who were more likely to use digital resources to engage in dishonest practices were males who did not put much effort into their homework and were enrolled in non-higher education-oriented school programs. Further, we found that digitally-supported homework avoidance was a significant negative predictor of test performance when considering information and communication technology predictors. Thus, the present study not only expands the knowledge regarding the predictors of academic dishonesty with digital resources, but also confirms the negative impact of such practices on learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Homework characteristics as predictors of advanced math achievement and attitude among US 12th grade students

Do home computers and Internet access harm academic and psychological outcomes? Statistical evidence from Brazil, Mexico, Morocco, Thailand, and Turkey

Academic Integrity Matters: Successful Learning with Mobile Technology

Explore related subjects.

- Digital Education and Educational Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Academic dishonesty is a widespread and perpetual issue for teachers made even more easier to perpetrate with the rise of digital technologies (Blau & Eshet-Alkalai, 2017 ; Ma et al., 2008 ). Definitions vary but overall an academically dishonest practices correspond to learners engaging in unauthorized practice such as cheating and plagiarism. Differences in engaging in those two types of practices mainly resides in students’ perception that plagiarism is worse than cheating (Evering & Moorman, 2012 ; McCabe, 2005 ). Plagiarism is usually defined as the unethical act of copying part or all of someone else’s work, with or without editing it, while cheating is more about sharing practices (Krou et al., 2021 ). As a result, most students do report cheating in an exam or for homework (Ma et al., 2008 ). To note, other research follow a different distinction for those practices and consider that plagiarism is a specific – and common – type of cheating (Waltzer & Dahl, 2022 ). Digital technologies have contributed to opening possibilities of homework avoidance and technology-related distraction (Ma et al., 2008 ; Xu, 2015 ).

The question of whether the use of digital resources hinders or enhances homework has often been investigated in large-scale studies, such as the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), and the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS). While most of the early large-scale studies showed positive overall correlations between the use of digital technologies for learning at home and test scores in language, mathematics, and science (e.g., OECD, 2015 ; Petko et al., 2017 ; Skryabin et al., 2015 ), there have been more recent studies reporting negative associations as well (Agasisti et al., 2020 ; Odell et al., 2020 ). One reason for these inconclusive findings is certainly the complex interplay of related factors, which include diverse ways of measuring homework, gender, socioeconomic status, personality traits, learning goals, academic abilities, learning strategies, motivation, and effort, as well as support from teachers and parents. Despite this complexity, it needs to be acknowledged that doing homework digitally does not automatically lead to productive learning activities, and it might even be associated with counter-productive practices such as digital distraction or academic dishonesty. Digitally enhanced academic dishonesty has mostly been investigated regarding formal assessment-related examinations (Evering & Moorman, 2012 ; Ma et al., 2008 ); however, it might be equally important to investigate its effects regarding learning-related assignments such as homework. Although a large body of research exists on digital academic dishonesty regarding assignments in higher education, relatively few studies have investigated this topic on K12 homework. To investigate this issue, we integrated questionnaire items on homework engagement and digital homework avoidance in a national add-on to PISA 2018 in Switzerland. Data from the Swiss sample can serve as a case study for further research with a wider cultural background. This study provides an overview of the descriptive results and tries to identify predictors of the use of digital technology for academic dishonesty when completing homework.

1.1 Prevalence and factors of digital academic dishonesty in schools

According to Pavela’s ( 1997 ) framework, four different types of academic dishonesty can be distinguished: cheating by using unauthorized materials, plagiarism by copying the work of others, fabrication of invented evidence, and facilitation by helping others in their attempts at academic dishonesty. Academic dishonesty can happen in assessment situations, as well as in learning situations. In formal assessments, academic dishonesty usually serves the purpose of passing a test or getting a better grade despite lacking the proper abilities or knowledge. In learning-related situations such as homework, where assignments are mandatory, cheating practices equally qualify as academic dishonesty. For perpetrators, these practices can be seen as shortcuts in which the willingness to invest the proper time and effort into learning is missing (Chow, 2021; Waltzer & Dahl, 2022 ). The interviews by Waltzer & Dahl ( 2022 ) reveal that students do perceive cheating as being wrong but this does not prevent them from engaging in at least one type of dishonest practice. While academic dishonesty is not a new phenomenon, it has been changing together with the development of new digital technologies (Anderman & Koenka, 2017 ; Ercegovac & Richardson, 2004 ). With the rapid growth in technologies, new forms of homework avoidance, such as copying and plagiarism, are developing (Evering & Moorman, 2012 ; Ma et al., 2008 ) summarized the findings of the 2006 U.S. surveys of the Josephson Institute of Ethics with the conclusion that the internet has led to a deterioration of ethics among students. In 2006, one-third of high school students had copied an internet document in the past 12 months, and 60% had cheated on a test. In 2012, these numbers were updated to 32% and 51%, respectively (Josephson Institute of Ethics, 2012 ). Further, 75% reported having copied another’s homework. Surprisingly, only a few studies have provided more recent evidence on the prevalence of academic dishonesty in middle and high schools. The results from colleges and universities are hardly comparable, and until now, this topic has not been addressed in international large-scale studies on schooling and school performance.

Despite the lack of representative studies, research has identified many factors in smaller and non-representative samples that might explain why some students engage in dishonest practices and others do not. These include male gender (Whitley et al., 1999 ), the “dark triad” of personality traits in contrast to conscientiousness and agreeableness (e.g., Cuadrado et al., 2021 ; Giluk & Postlethwaite, 2015 ), extrinsic motivation and performance/avoidance goals in contrast to intrinsic motivation and mastery goals (e.g., Anderman & Koenka, 2017 ; Krou et al., 2021 ), self-efficacy and achievement scores (e.g., Nora & Zhang, 2010 ; Yaniv et al., 2017 ), unethical attitudes, and low fear of being caught (e.g., Cheng et al., 2021 ; Kam et al., 2018 ), influenced by the moral norms of peers and the conditions of the educational context (e.g., Isakov & Tripathy, 2017 ; Kapoor & Kaufman, 2021 ). Similar factors have been reported regarding research on the causes of plagiarism (Husain et al., 2017 ; Moss et al., 2018 ). Further, the systematic review from Chiang et al. ( 2022 ) focused on factors of academic dishonesty in online learning environments. The analyses, based on the six-components behavior engineering, showed that the most prominent factors were environmental (effect of incentives) and individual (effect of motivation). Despite these intensive research efforts, there is still no overarching model that can comprehensively explain the interplay of these factors.

1.2 Effects of homework engagement and digital dishonesty on school performance

In meta-analyses of schools, small but significant positive effects of homework have been found regarding learning and achievement (e.g., Baş et al., 2017 ; Chen & Chen, 2014 ; Fan et al., 2017 ). In their review, Fan et al. ( 2017 ) found lower effect sizes for studies focusing on the time or frequency of homework than for studies investigating homework completion, homework grades, or homework effort. In large surveys, such as PISA, homework measurement by estimating after-school working hours has been customary practice. However, this measure could hide some other variables, such as whether teachers even give homework, whether there are school or state policies regarding homework, where the homework is done, whether it is done alone, etc. (e.g., Fernández-Alonso et al., 2015 , 2017 ). Trautwein ( 2007 ) and Trautwein et al. ( 2009 ) repeatedly showed that homework effort rather than the frequency or the time spent on homework can be considered a better predictor for academic achievement Effort and engagement can be seen as closely interrelated. Martin et al. ( 2017 ) defined engagement as the expressed behavior corresponding to students’ motivation. This has been more recently expanded by the notion of the quality of homework completion (Rosário et al., 2018 ; Xu et al., 2021 ). Therefore, it is a plausible assumption that academic dishonesty when doing homework is closely related to low homework effort and a low quality of homework completion, which in turn affects academic achievement. However, almost no studies exist on the effects of homework avoidance or academic dishonesty on academic achievement. Studies investigating the relationship between academic dishonesty and academic achievement typically use academic achievement as a predictor of academic dishonesty, not the other way around (e.g., Cuadrado et al., 2019 ; McCabe et al., 2001 ). The results of these studies show that low-performing students tend to engage in dishonest practices more often. However, high-performing students also seem to be prone to cheating in highly competitive situations (Yaniv et al., 2017 ).

1.3 Present study and hypotheses

The present study serves three combined purposes.