- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

The killing of Christopher Seider and the end of the rope

From mob to “massacre”.

- Aftermath and agitprop

What was the Boston Massacre?

Why did the boston massacre happen.

- What are the American colonies?

- Who established the American colonies?

- What pushed the American colonies toward independence?

Boston Massacre

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Bill of Rights Institute - The Boston Massacre

- National Park Service - Boston Massacre

- Khan Academy - The Boston Massacre

- The Ohio State University - Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective - The Boston Massacre

- Teach Democracy - The Boston Massacre

- World History Encyclopedia - Boston Massacre

- Colonial America - Boston Massacre Facts

- Alpha History - The Boston Massacre

- American Battlefield Trust - The Boston Massacre

- Public Broadcasting Service - Africans in America - The Boston Massacre

- Boston Massacre - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Boston Massacre - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The incident was the climax of growing unrest in Boston , fueled by colonists’ opposition to a series of acts passed by the British Parliament . Especially unpopular was an act that raised revenue through duties on lead, glass, paper, paint, and tea. On March 5, 1770, a crowd confronted eight British soldiers in the streets of the city. As the mob insulted and threatened them, the soldiers fired their muskets, killing five colonists.

In 1767 the British Parliament passed the Townshend Acts , designed to exert authority over the colonies. One of the acts placed duties on various goods, and it proved particularly unpopular in Massachusetts . Tensions began to grow, and in Boston in February 1770 a patriot mob attacked a British loyalist, who fired a gun at them, killing a boy. In the ensuing days brawls between colonists and British soldiers eventually culminated in the Boston Massacre.

Why was the Boston Massacre important?

The incident and the trials of the British soldiers, none of whom received prison sentences, were widely publicized and drew great outrage. The events contributed to the unpopularity of the British regime in much of colonial North America and helped lead to the American Revolution .

Boston Massacre , (March 5, 1770), skirmish between British troops and a crowd in Boston , Massachusetts . Widely publicized, it contributed to the unpopularity of the British regime in much of colonial North America in the years before the American Revolution .

In 1767, in an attempt to recoup the considerable treasure expended in the defense of its North American colonies during the French and Indian War (1754–63), the British Parliament enacted strict provisions for the collection of revenue duties in the colonies. Those duties were part of a series of four acts that became known as the Townshend Acts , which also were intended to assert Parliament’s authority over the colonies, in marked contrast to the policy of salutary neglect that had been practiced by the British government during the early to mid-18th century. The imposition of those duties—on lead, glass, paper, paint, and tea upon their arrival in colonial ports—met with angry opposition from many colonists in Massachusetts. In addition to organized boycotts of those goods, the colonial response took the form of harassment of British officials and vandalism. Parliament answered British colonial authorities’ request for protection by dispatching the 14th and 29th regiments of the British army to Boston, where they arrived in October 1768. The presence of those troops, however, heightened the tension in an already anxious environment .

Early in 1770, with the effectiveness of the boycott uneven, colonial radicals, many of them members of the Sons of Liberty , began directing their ire against those businesses that had ignored the boycott. The radicals posted signs (large hands emblazoned with the word importer ) on the establishments of boycott-violating merchants and berated their customers. On February 22, when Ebenezer Richardson, who was known to the radicals as an informer, tried to take down one of those signs from the shop of his neighbour Theophilus Lillie, he was set upon by a group of boys. The boys drove Richardson back into his own nearby home, from which he emerged to castigate his tormentors, drawing a hail of stones that broke Richardson’s door and front window. Richardson and George Wilmont, who had come to his defense, armed themselves with muskets and accosted the boys who had entered Richardson’s backyard. Richardson fired, hitting 11-year-old Christopher Seider (or Snyder or Snider; sources differ on his last name), who died later that night. Seemingly, only the belief that Richardson would be brought to justice in court prevented the crowd from taking immediate vengeance upon him.

With tensions running high in the wake of Seider’s funeral, brawls broke out between soldiers and rope makers in Boston’s South End on March 2 and 3. On March 4 British troops searched the rope works owned by John Gray for a sergeant who was believed to have been murdered. Gray, having heard that British troops were going to attack his workers on Monday, March 5, consulted with Col. William Dalrymple, the commander of the 14th Regiment. Both men agreed to restrain those in their charge, but rumours of an imminent encounter flew.

On the morning of March 5 someone posted a handbill ostensibly from the British soldiers promising that they were determined to defend themselves. That night a crowd of Bostonians roamed the streets, their anger fueled by rumours that soldiers were preparing to cut down the so-called Liberty Tree (an elm tree in what was then South Boston from which effigies of men who had favoured the Stamp Act had been hung and on the trunk of which was a copper-plated sign that read “The Tree of Liberty”) and that a soldier had attacked an oysterman. One element of the crowd stormed the barracks of the 29th Regiment but was repulsed. Bells rang out an alarm and the crowd swelled , but the soldiers remained in their barracks, though the crowd pelted the barracks with snowballs. Meanwhile, the single sentry posted outside the Customs House became the focus of the rage for a crowd of 50–60 people. Informed of the sentry’s situation by a British sympathizer, Capt. Thomas Preston marched seven soldiers with fixed bayonets through the crowd in an attempt to rescue the sentry. Emboldened by the knowledge that the Riot Act had not been read—and that the soldiers could not fire their weapons until it had been read and then only if the crowd failed to disperse within an hour—the crowd taunted the soldiers and dared them to shoot (“provoking them to it by the most opprobrious language,” according to Thomas Gage , commander in chief of the British army in America). Meanwhile, they pelted the troops with snow, ice, and oyster shells.

In the confusion, one of the soldiers, who were then trapped by the patriot mob near the Customs House, was jostled and, in fear, discharged his musket . Other soldiers, thinking they had heard the command to fire, followed suit. Three crowd members—including Crispus Attucks , a Black sailor who likely was formerly enslaved—were shot and died almost immediately. Two of the eight others who were wounded died later. Hoping to prevent further violence, Lieut. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson , who had been summoned to the scene and arrived shortly after the shooting had taken place, ordered Preston and his contingent back to their barracks, where other troops had their guns trained on the crowd. Hutchinson then made his way to the balcony of the Old State House, from which he ordered the other troops back into the barracks and promised the crowd that justice would be done, calming the growing mob and bringing an uneasy peace to the city.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Boston Massacre

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 24, 2024 | Original: October 27, 2009

The Boston Massacre was a deadly riot that occurred on March 5, 1770, on King Street in Boston. It began as a street brawl between American colonists and a lone British soldier, but quickly escalated to a chaotic, bloody slaughter. The conflict energized anti-British sentiment and paved the way for the American Revolution.

Why Did the Boston Massacre Happen?

Tensions ran high in Boston in early 1770. More than 2,000 British soldiers occupied the city of 16,000 colonists and tried to enforce Britain’s tax laws, like the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts . American colonists rebelled against the taxes they found repressive, rallying around the cry, “no taxation without representation.”

Skirmishes between colonists and soldiers—and between patriot colonists and colonists loyal to Britain (loyalists)—were increasingly common. To protest taxes, patriots often vandalized stores selling British goods and intimidated store merchants and their customers.

On February 22, a mob of patriots attacked a known loyalist’s store. Customs officer Ebenezer Richardson lived near the store and tried to break up the rock-pelting crowd by firing his gun through the window of his home. His gunfire struck and killed an 11-year-old boy named Christopher Seider and further enraged the patriots.

Several days later, a fight broke out between local workers and British soldiers. It ended without serious bloodshed but helped set the stage for the bloody incident yet to come.

How Many Died After Violence Erupted?

On the frigid, snowy evening of March 5, 1770, Private Hugh White was the only soldier guarding the King’s money stored inside the Custom House on King Street. It wasn’t long before angry colonists joined him and insulted him and threatened violence.

At some point, White fought back and struck a colonist with his bayonet. In retaliation, the colonists pelted him with snowballs, ice and stones. Bells started ringing throughout the town—usually a warning of fire—sending a mass of male colonists into the streets. As the assault on White continued, he eventually fell and called for reinforcements.

In response to White’s plea and fearing mass riots and the loss of the King’s money, Captain Thomas Preston arrived on the scene with several soldiers and took up a defensive position in front of the Custom House.

Worried that bloodshed was inevitable, some colonists reportedly pleaded with the soldiers to hold their fire as others dared them to shoot. Preston later reported a colonist told him the protestors planned to “carry off [White] from his post and probably murder him.”

The violence escalated, and the colonists struck the soldiers with clubs and sticks. Reports differ of exactly what happened next, but after someone supposedly said the word “fire,” a soldier fired his gun, although it’s unclear if the discharge was intentional.

Once the first shot rang out, other soldiers opened fire, killing five colonists–including Crispus Attucks , a local dockworker of mixed racial heritage–and wounding six. Among the other casualties of the Boston Massacre was Samuel Gray, a rope maker who was left with a hole the size of a fist in his head. Sailor James Caldwell was hit twice before dying, and Samuel Maverick and Patrick Carr were mortally wounded.

7 Events That Enraged Colonists and Led to the American Revolution

Colonists didn't just take up arms against the British out of the blue. A series of events escalated tensions that culminated in America's war for independence.

8 Things We Know About Crispus Attucks

Crispus Attucks, a multiracial man who had escaped slavery, is known as the first American colonist killed in the American Revolution.

Did a Snowball Fight Start the American Revolution?

On a cold night in Boston in 1770, angry colonists pelted a lone British sentry with snowballs. The rest is history.

Boston Massacre Fueled Anti-British Views

Within hours, Preston and his soldiers were arrested and jailed and the propaganda machine was in full force on both sides of the conflict.

Preston wrote his version of the events from his jail cell for publication, while Sons of Liberty leaders such as John Hancock and Samuel Adams incited colonists to keep fighting the British. As tensions rose, British troops retreated from Boston to Fort William.

Paul Revere encouraged anti-British attitudes by etching a now-famous engraving depicting British soldiers callously murdering American colonists. It showed the British as the instigators though the colonists had started the fight.

It also portrayed the soldiers as vicious men and the colonists as gentlemen. It was later determined that Revere had copied his engraving from one made by Boston artist Henry Pelham.

John Adams Defends the British

It took seven months to arraign Preston and the other soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre and bring them to trial. Ironically, it was American colonist, lawyer and future President of the United States John Adams who defended them.

Adams was no fan of the British but wanted Preston and his men to receive a fair trial. After all, the death penalty was at stake and the colonists didn’t want the British to have an excuse to even the score. Certain that impartial jurors were nonexistent in Boston, Adams convinced the judge to seat a jury of non-Bostonians.

During Preston’s trial, Adams argued that confusion that night was rampant. Eyewitnesses presented contradictory evidence on whether Preston had ordered his men to fire on the colonists.

But after witness Richard Palmes testified that, “…After the Gun went off I heard the word ‘fire!’ The Captain and I stood in front about half between the breech and muzzle of the Guns. I don’t know who gave the word to fire,” Adams argued that reasonable doubt existed; Preston was found not guilty.

The remaining soldiers claimed self-defense and were all found not guilty of murder. Two of them—Hugh Montgomery and Matthew Kilroy—were found guilty of manslaughter and were branded on the thumbs as first offenders per English law.

To Adams’ and the jury’s credit, the British soldiers received a fair trial despite the vitriol felt towards them and their country.

Aftermath of the Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre had a major impact on relations between Britain and the American colonists. It further incensed colonists already weary of British rule and unfair taxation and roused them to fight for independence.

Yet perhaps Preston said it best when he wrote about the conflict and said, “None of them was a hero. The victims were troublemakers who got more than they deserved. The soldiers were professionals…who shouldn’t have panicked. The whole thing shouldn’t have happened.”

Over the next five years, the colonists continued their rebellion and staged the Boston Tea Party , formed the First Continental Congress and defended their militia arsenal at Concord against the redcoats, effectively launching the American Revolution . Today, the city of Boston has a Boston Massacre site marker at the intersection of Congress Street and State Street, a few yards from where the first shots were fired.

After the Boston Massacre. John Adams Historical Society. Boston Massacre Trial. National Park Service: National Historical Park of Massachusetts. Paul Revere’s Engraving of the Boston Massacre, 1770. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. The Boston Massacre. Bostonian Society Old State House. The Boston “Massacre.” H.S.I. Historical Scene Investigation.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Account of the Boston Massacre

- March 05, 1770

- March 06, 1770

- March 08, 1770

No related resources

Introduction

The Townshend Acts resulted in colonists’ nonimportation agreements. The enforcement of these pacts sometimes resulted in violence. On February 22, 1770, when a group of Boston teenagers placed a sign in front of the shop of merchant Theophilus Lillie noting his status as an “IMPORTER,” an angry crowd gathered. Ebenezer Richardson (1718–?), a customs employee who tried but failed to remove the sign, succeeded in attracting the scorn of the mob, which followed him home. As his house shook and his windows shattered, Richardson panicked and fired his shotgun into the crowd, killing 10-year-old Christopher Seider (1759–1770).

Seider’s death sparked outrage in Boston. The presence of British troops, who had arrived in 1768, did nothing to defuse tensions. By 1770, there was one Redcoat for every four of the city’s 16,000 inhabitants. Off-duty soldiers and civilians sometimes brawled in the streets, as on the nights of Friday, March 2, and Saturday, March 3. On Monday, March 5, Lord North (1732–1792), the new prime minister (1770–1782), introduced in Parliament a bill repealing most of the taxes imposed by the Townshend Acts. Yet this act, meant to improve relations between Britain and its colonies, would be overshadowed by the Boston Massacre, which occurred that same evening.

Taken together, accounts of the night’s events make clear the basic details of the “massacre.” Angry Bostonians surrounded a Redcoat sentry who stood at the door of the customhouse. They hurled snowballs, ice, and insults. He returned the crowd’s strong words. The crowd grew—and grew angrier. Church bells rang, summoning additional people, many of whom carried buckets because they thought the bells signaled a nearby fire. Captain Thomas Preston (c. 1722–c. 1798), who had been watching from a distance, marched with seven soldiers, bayonets fixed to their muskets, to rescue the sentry. Soon all nine of these Redcoats had their backs to the wall of the customhouse. In this chaos, Preston later testified, he ordered his men not to fire their half-cocked muskets. Meanwhile, people in the noisy crowd yelled “Fire!” One soldier, hit by a chunk of ice, discharged his musket. The other soldiers then fired as well. The soldiers wounded 11 members of the mob. Three died within minutes. Another died hours later. A fifth died after several days.

In October and November, in two separate trials, John Adams (1735–1826) served as defense attorney for Preston and his men. Presented with the testimony of multiple witnesses, a jury found Preston not guilty. Another jury found all but two of his men not guilty; the others were convicted of manslaughter, branded with an “M” between the thumb and index finger, and released. The British fared more poorly in the court of public opinion. A depiction popularized by the engraving of Paul Revere (1734–1818) showed Preston ordering his men to fire and the victims with their backs against the wall (see illustration). Meanwhile, merchant John Tudor (1709–1795), a deacon at the Second Church of Boston, recorded in his diary what he had seen and heard about the incident and its aftermath. As news of the massacre spread, more and more Americans wondered if the British government, entrusted to protect their lives, liberty, and property, in fact posed a grievous threat to those essential rights.

Source: William Tudor, ed., Deacon Tudor’s Diary …. (Boston: Wallace Spooner, 1896), 30–34. https://archive.org/details/deacontudorsdiar00tudo/page/n79

On Monday evening, the 5th current, a few minutes after 9 o’clock, a most horrid murder was committed in King Street before the customhouse door by 8 or 9 soldiers under the command of Captain Thomas Preston, drawn off from the main guard on the south side of the townhouse.

March 5 [Monday]

This unhappy affair began by some boys and young fellows throwing snowballs at the sentry placed at the customhouse door. On which 8 or 9 soldiers came to his assistance. Soon after a number of people collected, when the captain commanded the soldiers to fire, which they did and 3 men were killed on the spot and several mortally wounded, one of which died [ the ] next morning. The captain soon drew off his soldiers up to the main guard, or the consequences might have been terrible, for on the guns firing the people were alarmed and set the bells ringing as if for fire, which drew multitudes to the place of action. Lieutenant Governor [ Thomas ] Hutchinson, who was commander in chief, was sent for and came to the council chamber, where some of the magistrates attended. The [ lieutenant ] governor desired the multitude about 10 o’clock to separate and go home peaceable and he would do all in his power that justice should be done, etc…. The people insisted that the soldiers should be ordered to their barracks 1st before they would separate, which being done the people separated about 1 o’clock….

Captain Preston was taken up by a warrant… and we sent him to jail soon after 3, having evidence sufficient to commit him, on his ordering the soldiers to fire….

[March 6, Tuesday]

The next forenoon the 8 soldiers that fired on the inhabitants were also sent to jail. Tuesday A.M. the inhabitants met at Faneuil Hall and after some pertinent speeches, chose a committee of 15 gentlemen to wait on the lieutenant governor in council to request the immediate removal of the troops. The message was in these words. That it is the unanimous opinion of this meeting that the inhabitants and soldiery can no longer live together in safety; that nothing can rationally be expected to restore the peace of the town and prevent blood and carnage but the removal of the troops; and that we most fervently pray his honor that his power and influence may be exerted for their instant removal. His honor’s reply was, gentlemen I am extremely sorry for the unhappy difference and especially of the last evening, and signifying that it was not in his power to remove the troops, etc., etc.

The above reply was not satisfactory to the inhabitants, as but one regiment should be removed to the Castle Barracks. [1] In the afternoon the town adjourned to Dr. Sewill’s Meetinghouse, [2] for Faneuil Hall was not large enough to hold the people, there being at least 3,000, some supposed near 4,000, when they chose a committee to wait on the lieutenant governor to let him and the council know that nothing less will satisfy the people than a total and immediate removal of the troops out of the town.

His honor laid before the council the vote of the town. The council thereon expressed themselves to be unanimously of [ the ] opinion that it was absolutely necessary for his majesty’s service, the good order of the town, etc., that the troops should be immediately removed out of the town.

His honor communicated this advice of the council to Colonel Dalrymple [3] and desired he would order the troops down to Castle William. After the colonel had seen the vote of the council he gave his word and honor to the town’s committee that both the regiments should be removed without delay. The committee returned to the town meeting and Mr. Hancock, [4] chairman of the committee, read their report as above, which was received with a shout and clap of hands, which made the meetinghouse ring….

March 8 (Thursday)

Agreeable to a general request of the inhabitants, were followed to the grave (for they were all buried in one) in succession the 4 bodies of Messrs. Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell, and Crispus Attucks, the unhappy victims who fell in the bloody massacre. [5] On this sorrowful occasion most of the shops and stores in town were shut, all the bells were ordered to toll a solemn peal in Boston, Charleston, Cambridge, and Roxbury. The several hearses forming a junction in King Street, the theater of that inhuman tragedy, proceeded from thence through the main street, lengthened by an immense concourse of people so numerous as to be obliged to follow in ranks of 4 and 6 abreast and brought up by a long train of carriages. The sorrow visible in the countenances, together with the peculiar solemnity, surpass description; it was supposed that the spectators and those that followed the corps amounted to 15,000, some supposed 20,000. Note [ that ] Captain Preston was tried for his life on the affair of the above [ on ] October 24, 1770. The trial lasted 5 days, but the jury brought him in not guilty.

- 1. The barracks were located at Castle William (renamed Fort Independence in 1797) on Castle Island in Boston Harbor.

- 2. The Old South Church.

- 3. Colonel William Dalrymple (1736–1807), commander of the British troops in Boston.

- 4. John Hancock (1737–1793).

- 5. The fifth fatality, Patrick Carr, died on March 14 and was buried alongside the other victims on March 17

The Virginia Resolves of 1769

Report of a committee of the town of boston, see our list of programs.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Check out our collection of primary source readers

Coming soon! World War I & the 1920s!

Everything you've ever wanted to know about the American Revolution

Boston Massacre of 1770 | Summary, Causes, Effects, Facts

About the author.

Edward A. St. Germain created AmericanRevolution.org in 1996. He was an avid historian with a keen interest in the Revolutionary War and American culture and society in the 18th century. On this website, he created and collated a huge collection of articles, images, and other media pertaining to the American Revolution. Edward was also a Vietnam veteran, and his investigative skills led to a career as a private detective in later life.

The Boston Massacre was an incident that occurred on March 5, 1770, where a group of British soldiers fired into a crowd of civilians on King Street in Boston.

In this article, we’ve explained what happened during the Boston Massacre, and what caused it. We’ve also explained what happened in the aftermath, and provided some interesting facts about the event.

On the evening of March 5, 1770, two British soldiers guarding the Boston Custom House got into an argument with a local apprentice, leading one of the soldiers to hit the boy over the head with his musket.

A colonist who witnessed the assault began arguing with the soldiers, and gradually a mob formed, surrounding the British troops on the steps of the Custom House.

The crowd grew to over 300 people over the course of a few hours, and the British called for backup. They eventually ended up with nine men, including Captain Thomas Preston, who arrived from the nearby barracks.

The crowd threw snowballs, stones, and other projectiles, and hurled insults at the soldiers. Eventually, the soldiers panicked, and let out a volley of shots.

Three Americans were killed instantly, and another two would later die in hospital. Eight further civilians were injured.

In the late 1760s, tension was building between American colonists and the British government.

The British implemented the Stamp Act in 1765 , creating a new direct tax on colonial consumers. This led to widespread protests – colonists were outraged, as they did not feel the British had the right to tax them without their consent. Ultimately, the British were forced to repeal the Stamp Act a year later.

To the colonists’ dismay, the British immediately began implementing new laws to try and increase taxation revenue, in part by cracking down on illegal smuggling.

In 1767 and 1768, the British implemented the Townshend Acts . The Acts gave customers officials more power to search colonial ships and seize goods, and made it so that people accused of smuggling would be tried by a judge, rather than a colonial jury, increasing the likelihood of a conviction.

The acts also reduced the tax on tea purchased from the British East India Company, and placed new taxes on certain goods traded by colonial merchants.

The Townshend Acts caused widespread discontent, especially in Boston. At the time, Boston was a major trading hub, meaning it was home to large numbers of colonial merchants, sailors, and traders, who relied on being able to conduct commerce (including illegal smuggling) to make a living.

Boston residents were also upset by the presence of large numbers of British troops stationed in the city, who had arrived in 1768 to deal with protests, vandalism, and violence caused by the Townshend Acts.

Officially, under the British Quartering Act of 1765 , Massachusetts was supposed to provide housing and other supplies to British troops in their colony, which further upset the colonists.

Essentially, the Boston Massacre occurred because the people of Boston were extremely upset with the British authorities in the late 1760s and early 1770s. They felt that the British were threatening their livelihoods, freedom, and the autonomy of their colony.

Aftermath and effects

Immediately after the Boston Massacre, there was a fight to control the narrative about what happened.

The Patriot side labeled the event “The Boston Massacre” and portrayed it as a senseless killing of unarmed civilians, orchestrated by the British Army.

Paul Revere produced a famous propaganda engraving of the incident, which is shown below.

This engraving is not factually accurate – the British did not open fire in an orderly fashion as the image suggests, and they were not given the order to fire as the scene depicts.

The British called the event “The Incident on King Street” and tried to quell tensions in Boston. British troops were removed from the city, and those involved in the massacre were arrested and charged with murder.

For the Patriot side, propaganda about the Boston Massacre was very effective. The event caused an increase in colonial unity against British rule, and was used to demonstrate that the British government were tyrants, as hardline Patriots argued.

The trials for the soldiers were held in a colonial court in Massachusetts. The colonial government wanted to avoid a further escalation in tension with the British, so care was taken to ensure a fair trial.

John Adams , a leading Patriot, was brought in to defend the soldiers to avoid any accusations of bias from Bostonians.

The trial was decided by jury, to improve public trust. However, none of the jurors were from Boston, as the court thought that Bostonians would be too biased against the British.

Adams argued that the soldiers feared for their lives, and were forced to open fire after the crowd attacked them. He claimed that the crowd got close enough to grab the soldier’s bayonets, although some eyewitness accounts contradicted this.

In the end, six of the eight soldiers were acquitted, including Captain Preston. Two soldiers who were found to have fired into the crowd were found guilty of manslaughter, and were sentenced to branding of the thumb, escaping the death penalty.

- The first person killed during the massacre is thought to be Crispus Attucks, a man of African and Native American descent. He is remembered as a significant figure in African-American history, as the first person killed during the American Revolution, five years before the Revolutionary War officially started.

- The term “Boston Massacre” was coined by Samuel Adams to emphasize the brutality of the event and rally public support against the British government. The word was used to evoke strong emotions, even though the killing was relatively small in scale compared to most definitions of the word “massacre”.

- Following the incident, Bostonians began the tradition of marking the anniversary of the event with speeches and commemorations, which became known as the “Boston Massacre Orations”.

- The famous engraving by Paul Revere, depicting the Boston Massacre, was actually based on a drawing by Henry Pelham, another artist. Revere’s version was altered to emphasize the violence of the British.

- It remains unclear who exactly fired the first shot during the Boston Massacre. Some reports suggest that a soldier was knocked down by a club or a stick, and his musket discharged as he fell, while others believe the firing was more deliberate.

Related posts

Diary of charles herbert, american prisoner of war in britain.

Read the diary of Charles Herbet, a Continental soldier that was captured by the British Army and sent to a prison of war camp in the UK.

1781 Entries | James Thatcher’s Military Journal

Read entries from 1781 in the journal of James Thatcher, Continental Army surgeon during the American Revolution.

1780 Entries | James Thatcher’s Military Journal

Read entries from 1780 in the journal of James Thatcher, Continental Army surgeon during the American Revolution.

- Perspectives on the Boston Massacre

Reactions and Responses

- The Massacre Illustrated

- Anniversaries

- Browse Items by Format

In the days and weeks following the events of 5 March 1770, Boston residents wrote diary entries and letters trying to make sense of what exactly had happened that evening on King Street. It didn't take long for more public responses to also appear, in London as well as in Boston, in the form of poetry, calls for a quicker response by the court system and published testimonies from eye-witnesses.

Initial Reactions

…firing on the inhabitants in king street, killing 6. and wounding 5 others…, …the inhabitants are greatly enraged and not without reason-, …the noise of the bells the bustle of the town the beating of drums & the reports of killed and wounded…, …let it never be forgot…, …our common enemy's (you know who they are) have availd themselves of our neglect…, o [that] god could appear for us in this dark day…, …this is quite new to have the superior court directed by persons void of any legal authority….

Spreading the Word

…they have planned, and are executing a scheme of misrepresentation…, i beg the favour of you to make some inquiry into the origin and occasion of it; and that it may be done with as much caution and secrecy as possible, i will take every precaution which is in my power, the removal of the troops was in the slowest order, insomuch that eleven days were spent in carrying the two regiments to castle island.

Printed Accounts

Thus were we, in aggravation of our other embarrassments, embarrassed with troops, forced upon us, vid [see] landing of troops, &c, it was become unsafe for an officer or soldier to walk the streets, when a people have lost all confidence in government, it is vain to expect a cordial obedience to it., the blood of our fellow citizens running like water thro' king-street….

Poetry as Propaganda

Then the captain commanded them to fire away, / and one of the soldiers obey'd as they say., if bloody men intrudes upon our land, / where shall we go or wither shall we stand , but now at length your trials they draw near --, additional sources.

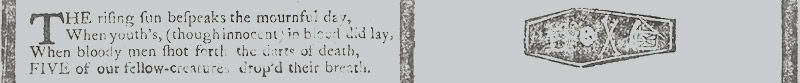

Harbottle Dorr's newspaper collection contains one of the first reported accounts to appear after the Massacre, in the 12 March 1770 Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal (see pages 3 and 4 of the display.) Dorr affixed a copy of a small woodcut of the Massacre scene made by Paul Revere to the first page of that newspaper. The 19 March 1770 issue of the Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal continues reportage of the incident.

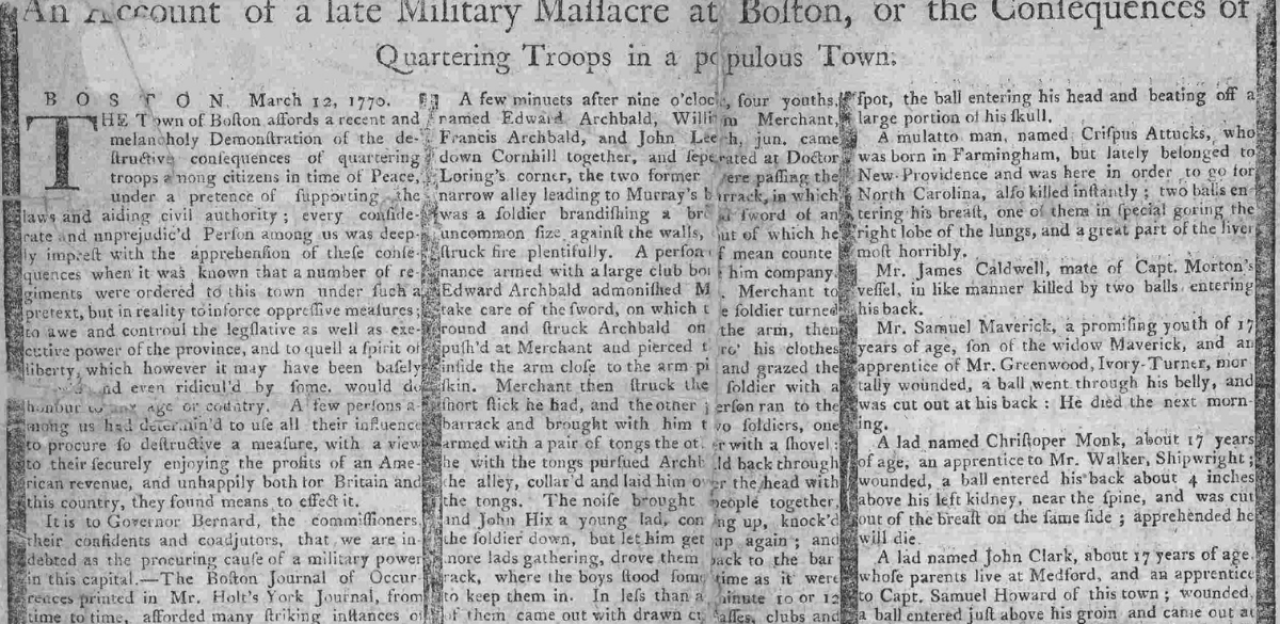

Account of the Boston Massacre

An Account of a late Military Massacre at Boston, or the Consequences of Quartering Troops in a populous Town.

BOSTON March 12, 1770.

THE Town of Boston affords a recent and melancholy Demonstration of the destructive consequences of quartering troops among citizens in time of Peace, under a pretence of supporting the laws and aiding civil authority; every considerate and unprejudic'd Person among us was deeply imprest with the apprehension of these consequences when it was known that a number of regiments were ordered to this town under such a pretext, but in reality to inforce oppressive measures; to awe and controul the legslative as well as executive power of the province, and to quell a spirit of liberty, which however it may have been basely and even ridicul'd by some, would do honour to any age or country. A few persons among us had determin'd to use all their influence to procure so destructive a measure, with a view to their securely enjoying the profits of an American revenue, and unhappily both for Britain and this country, they found means to effect it.

It is to Governor Bernard, the commissioners, their confidents and coadjutors, that we are indebted as the procuring cause of a military power in this capital.—The Boston Journal of Occurrences printed in Mr. Holt's York Journal, from time to time, afforded many striking instances of the distresses brought upon the inhabitants by this measure; and since those Journals have been discontinued, our troubles from that quarter have been growing upon us: We have known a party of soldiers in the face of day fire off a loaded musket upon the inhabitants, others have been prick'd with bayonets, and even our magistrate assaulted and put in danger of their lives, where offenders brought before them have been rescued and why those and other bold and base criminals have as yet escaped the punishment due to their crimes, may be soon matter of enquiry by the representative body of this people.—It is natural to suppose that when the inhabitants saw those laws which had been enacted for their security, and which they were ambitious of holding up to the soldiery, eluded, they should most commonly resent for themselves—and accordingly if so has happened; many have been the squabbles between them and the soldiery; but it seems their being often worsted by our youth in those ren counters, has only serv'd to irritate the former.—What passed at Mr. Gray's rope walk, has already been given the public, and may be said to have led the way to the late catastrophe.—That the rope walk lads when attacked by superior numbers should defend themselves with so much spirit and success in the club-way, was too mortifying, and perhaps it may hereafter appear, that even some of their officers, were unnappily affected with this circumstance: Divers stories were propagated among the soldiery, that serv'd to agitate their spirits particularly on the Sabbath, that one Chambers, a serjeant, represented as a sober man, had been missing the preceding day, and must therefore have been murdered by the townsmen; an officer of distinction so far credited this report, that he enter'd Mr. Gray's rope-walk that Sabbath; and when enquired of by that gentleman as soon as he could meet him, the occasion of his so doing, the officer reply'd, that it was to look if the serjeant said to be murdered had not been hid there; this sober serjeant was found on the Monday unhurt in a house of pleasure.—The evidences already collected shew, that many threatnings had been thrown out by the soldiery, but we do not pretend to say there was any preconcerted plan; when the evidences are published, the world will judge.—We may however venture to declare, that it appears too probable from their conduct, that some of the soldiery aimed to draw and provoke the townsmen into squabbles, and that they then intended to make use of other weapons than canes, clubs or bludgeons,

Our readers will doubtless expect a circumstantial account of the tragical affair on Monday night last; but we hope they will excuse our being so particular as we should have been, had we not seen that the town was intending an inquiry and full representation thereof.

On the evening of Monday, being the 5th current, several soldiers of the 29th regiment were seen parading the streets with their drawn cutlasses and , abusing and wounding numbers of the .

A few minutes after nine o'clock, four youths, named Edward Archbald, William Merchant, Francis Archbald, and John Leech, jun. came down Cornhill together, and seperated at Doctor Loring's corner, the two former were passing the narrow alley leading to Murray's barrack, in which was a soldier brandishing a sword of an uncommon size against the walls, but of which he struck fire plentifully. A person of mean countenance armed with a large club bore him company. Edward Archbald admonished Mr. Merchant to take care of the sword, on which the soldier turned round and struck Archbald on the arm, then push'd at Merchant and pierced thro' his clothes inside the arm close to the arm pit and grazed the skin. Merchant then struck the soldier with a short stick he had, and the other person ran to the barrack and brought with him two soldiers, one armed with a pair of tongs the other with a shovel; he with the tongs pursued Archbald back through the alley, collar'd and laid him over the head with the tongs. The noise brought people together, and John Hix a young lad, coming up, knock'd the soldier down, but let him get up again; and more lads gathering, drove them back to the barrack, where the boys stood sometime as it were to keep them in. In less than a minute 10 or 12 of them came out with drawn cutlasses, clubs and bayonets, and set upon the med boys and young folks, who stood them a little while but finding the inequality of their equipment dispersed.—On hearing the noise, one Samuel Atwood, came up to see what was the matter, and entering the alley from dock square, heard the latter part of the combat, and when the boys dispersed he met the 10 or 12 soldiers aforesaid rushing down the alley towards the square, and asked them if they intended to murder the people? They answered Yes, by G—d, root and branch! With that one of them struck Mr. Atwood with a club, which was repeated by another and being he turned to go off, received a wound on the left shoulder which reached the bone and gave him much pain. Retreating a few steps Mr Atwood met two offcers and said, Gentlemen what is the matter? They answered, you'll see by and by. Immediately after those heroes appeared in the square, asking where were the boogers where were the cowards? But notwithstanding their fierceness to naked men, one of them advanced towards a youth who had a split of a raw stave in his hand, and said damn them here is one of them; but the young man seeing a person near him with a drawn sword and a good cane ready to support him, held up his stave in defiance, and they quietly passed by him, up the little alley by Mr. Silsby's to King Street, where they attacked single and unarmed persons till they raised much clamour, and then turned down Cornhill street insulting all they met in like manner, and pursuing some to their very doors.

Thirty or forty persons, mostly lads, being by this means gathered in King-street, Capt. Preston with a party of men with charged bayonets, came from the main guard to the Commissioner's house the soldiers pushing their bayonets, crying, Make way! They took place by the custom-house, and continuing to push, to drive the people off, pricked some in several places; on which they were clamorous, and, it is said threw snow balls. On this, the Captain commanded them to fire, and more snow balls coming he again said, Damn you, Fire, be the consequence what it will! One soldier then fired, and a townsman with a dudgel struck him over the hands with such force that he dropt his firelock; and rushing forward aimed a blow at the Captain's head, which graz'd? hat and fell pretty heavy upon his arm: However, the soldiers continued the fire, successively, till or 8, or as some say 11 guns were discharged.

By this fatal manœuvre, three men were laid dead on the spot, and two more struggling for life; but what shewed a degree of cruelty unknown to British troops, at least since the house of Hanover has directed their operations, was an attempt to fire upon, or push with their bayonets the persons who undertook to remove the slain and wounded!

Mr. Benjamin Leigh, now undertaker in Delph Manufactory, came up, and after some conversation with Capt. Preston, relative to his conduct in this affair, advised him to draw off his men, with which he complied.

The dead are Mr. Samuel Gray, killed on the spot, the ball entering his head and beating off a large portion of his skull.

A mulatto man, named Crispus Attucks, who was born in Farmingham, but lately belonged to New Providence and was here in order to go for North Carolina, also killed instantly; two balls entering his breast, one of them in special goring the right lobe of the lungs, and a great part of the liver most horribly.

Mr. James Caldwell, mate of Capt. Morton's vessel, in like manner killed by two balls entering his back.

Mr. Samuel Maverick, a promising youth of 17 years of age, son of the widow Maverick, and an apprentice of Mr. Greenwood, Ivory Turner, mortally wounded, a ball went through his belly, and was cut out at his back: He died the next morning.

A lad named Christoper Monk, about 17 years of age, an apprentice to Mr. Walker, Shipwright; wounded, a ball entered his back about 4 inches above his left kidney, near the spine, and was cut out of the breast on the same side; apprehended he will die.

A lad named John Clark, about 17 years of age whose parents live at Medford, and an apprentice to Capt. Samuel Howard of this town; wounded a ball entered just above his groin and came out at his hip, on the opposite side, apprehended he will die.

Mr. Edward Payne, of this town, merchant, standing at his entry door, received a ball in his arm, which shattered some of the bones.

Mr. John Green, Taylor, coming up Leverett's Lane, received a ball just under his hip, and lodged it in the under part of his thigh, which was extracted

Mr. Robert Patterson, a seafaring man, who was the person that had his trowsers shot through in Richardson's affair, wounded; a ball went through his right arm, and he suffered great loss of blood.

Mr. Patrick Carr, about 30 years of age, who work'd with Mr. Field, Leather-Breeches maker in Queen-street, wounded, a ball enter'd near his hip, and went out at his side.

A lad named David Parker, an apprentice to Mr. Eddy the Wheelwright, wounded, a ball enter'd in his thigh.

The people were immediately alarmed with the report of this horrid massacre, the bells were set a ringing, and great numbers soon assembled at the place where this tragical scene had been acted; their feelings may be better conceived than expressed; and while some were taking care of the dead and wounded, the rest were in consultation what to do in these dreadful circumstances.—But so little intimidated were they, notwithstanding their being within a few yards of the main-guard, and seeing the 29th regiment under arms, and drawn up in King-street; that they kept their station, and appear'd as an officer of rank express'd it, ready to run upon the very muzzles of their muskets.—The Lieut. Governor soon came into the Town House, and there met some of his Majesty's Council, and a number of civil Magistrates; a considerable body of people immediately enter'd the Council chamber and expressed themselves to his Honour with a freedom and warmth becoming the occasion. He used his utmost endeavoure to pacify them, requesting that they would let the matter subside for the night, and promised to do all in his power that justice should be done, and the law have its course; men of influence and weight with the people were not wanting on their part to procure their compliance with his Honour's request, by representing the horrible consequences of a promiscuous and rash engagement in the night, and assuring them that such measures should be entered upon in the morning, as would be agreeable to their dignity, and more likely way of obtaining the best satisfaction for the blood of their fellow-townsmen.—The inhabitants attended to these suggestions, and the regiment under arms being ordered to the barracks which was insisted upon by the people, they then separated and return'd to their dwellings, by one o'clock. At 3 o'clock Capt. Preston was committed, as were the soldiers who fir'd, a few hour after him.

Tuesday morning presented a most shocking scene, the blood of our fellow-citizens running like water thro' King-street, and the Merchant's Exchange, the principal spot of the military parade

for about 18 months past. Our blood might also be track'd up to the head of Long-Lane, and thro' divers other streets and passages.

At eleven o'clock, the inhabitants met at Faneuil-Hall, and after some animated speeches, becoming the occasion, they chose a Committee of 15 respectable Gentlemen, to wait upon the Lieut. Governor in Council, to request of him to issue his orders for the immediate removal of the troops.

The Message was in these Words:

THAT it is the unanimous opinion of this meeting that the inhabitants and soldiery can no longer live together in safety; that nothing can rationally be expected to restore the peace of the town and prevent further blood and carnage, but the immediate removal of the troops; and that we therefore most servently pray his Honour, that his power and influence may be exerted for their instant removal.

His Honour's Reply, which was laid before the Town then adjourn'd to the Old South Meeting House, was as follows;

“I AM extremely sorry for the unhappy differences between the inhabitants and troops and especially for the action of the last evening, and I have exerted myself upon that occasion, that a due inquiry may be made, and that the law may have its course. I have in council consulted with the commanding officers of the two regiments who are in the town. They have their orders from the General at New-York. It is not in my power to countermand those orders. The council have desired that the two regiments may be removed to the Castle. From the particular concern which the 20th regiment has had in your differences, Col. Dalrymple, who is the commanding officer of the troops, has signified that regiment shall, with out delay, be placed in the barracks at the Castle until he can send to the General and receive his further orders concerning both the regiments; and that the main guard shall be removed, and the 14th regiment so disposed and laid under such restraint that all occasion of future disturbances may be prevented.”

The foregoing reply having been read and fully considered—the question was put, Whether there report be satisfactory? Passed in the negative, only 1 dissentient out of upwards of 4000 voters.

It was then moved and voted John Hancock, Esq; Mr. Samuel Adams, Mr. William Molineux, William Phillips, Esq; Dr. Joseph Warren. Joshua Henshaw, Esq; and Samuel Pemberton, Esq; be a Committee to wait on his Honour the Lieut. Governor, and inform him, that it is the unanimous Opinion of this Meeting, that the Reply made to a Vote of the Inhabitants presented his Honour in the Morning is by no means satisfactory; and that nothing less will satisfy, than a total and immediate removal off all the Troops.

The Committee having waited on the Lieut Governor agreeable to the foregoing Vote; laid before the Inhabitants the following Vote of Council received from his Honor.

His Honor the Lieut. Governor laid before the Board a Vote of the Town of Boston, passed this afternoon, and then addressed the Board as follows,

Gentlemen of the Council,

“I lay before you a Vote of the Town of Boston which I have just now received from them, and I now ask your advise what you judge necessary to be done upon it.”

The Council thereupon expressed themselves to be unanimously of opinion, “that it was absolutely necessary for his Majesty's service, the good order of the Town, and the Peace of the Province, that the Troops should be immediately removed out of the Town of Boston, and thereupon advised his Honor to communicate this Advise of the Council to Col. Dalrymple, and to pray that he would order the Troops down to Castle William.” The Committee also informed the Town, that Col. Dalrymple, after having seen the Vote of Council, said to the Committee, “That he now gave his word of Honor that he would begin his Preparations in the Morning, and that there should be no unnecessary delay until the whole of the two Regiments were removed to the Castle.

Upon the above Report being read, the Inhabitants could not avoid expressing the high satisfaction it afforded them.

After Measures were taken for the Security of the Town, in the Night by a strong Military Watch, the Meeting was Dissolved.

The 29th regiment have already left us, and the 14th regiment are following them, so that we expect the town will soon be clear of all the troops.

The wisdom and true policy of his majesty's council and Col. Dalrymple, the commander, appear in this measure. Two regiments in this populous city; and the inhabitants justly incensed: Those of the neighbouring towns actually under arms upon the first report of the massacre, and the signal only wanting to bring in a few hours to the gates of this city many thousands of our brave brethren in the country, deeply affected with our distresses, and to whom we are greatly obliged on this occasion—No one knows where this would have ended and what important consequences even to the whole British empire might have followed, which our moderation and loyalty upon so trying an occasion and our faith in the commander's assurances have happily prevented.

Last Thursday, agreeable to a general request of the Inhabitants, and by the consent of parents and friends, were carried to their grave in succession, the bodies of Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell and Chrispus Attucks, the unhappy victims who fell in the bloody massacre of the Monday evening preceeding!

On this occasion most of the shops in town were shut, all the bel?s were ordered to toll a solemn peal, as were al? those in the neighbouring towns of Charlestown Roxbury, &c. The procession began to move between the hours of 4 and 5 in the afternoon; two if the unfortunate sufferers, viz. Mess. James Goodwell and Crispus Attucks, who were strangers, borne from Faneuil-Hall, attended by a numerous twain of persons of all ranks; and the other two viz. Mr. Samuel Gray, from the House of Mr. Benjamin Gray, (his Brother) on the north side exchange, and Mr. Maverick, from the house of his distressed mother Mrs. Mary Maverick, in Union street, each followed by their respective relations and friends: The several hearses forming a junction in King street, the theatre of that inhuman tragedy! proceeded from thence thro' the main-street, lengthened by an immense concourse of people, so numerous as to be obliged a follow in ranks of fix, and brought up by a long train of carriages belonging to the principal entry of the town. The bodies were deposited in one vault in the middle burying-ground. The aggravated circumstances of their death, the distress and sorrow visible in every countenance, together with the peculiar solemnity with which the whole funeral was conducted, surpass description.

A military watch has been kept every night at the town-house and prison, in which many of the most respectable gentlemen of the town have appeared as the common soldiers, and night after night have given their attendance.

A Servant boy of one Manwaring the tide-waiter from Quebec, is now in goal, having deposed that himself, by the order and encouragement of his superiors, had discharged a musket several times from one of the windows of the house in King-street, hired by the commissioners and custom house officers to do their business in; more than one other person declared upon oath, that they apprehended several discharges came from that quarter.—It is not improbable that we may soon be able to account for the assassination of Mr. Otis some time past; the message by Wilmot, who came from the same house to the infamous Richardson before his firing the gun which kill'd young Snider, and to open up such a scene of villainy acted by a dirty banditti, at must astonish the public.

It is supposed that there must have been a greater number of people from town and country at the funeral of those who were massacred by the soldiers, than were ever together on this continent on any occasion.

A more dreadful tragedy has been acted by the soldiery in King-street, Boston, New-England than was some time since exhibitted in St. George's field, London, in old England, which may serve instead of Beacons for both countries.

Had those we thy Patriots, not only represented by Bernard and the commissioners as a faction, but as aiming at meaning a separation between Britain and the colonies had any thing else in contemplation than the preservation of our rights, and bringing things back to their old foundation What an opening has been given them?

Among other matters in the warrant for the annual town-meeting this day, is the following clause, viz. “Whether the town will take any measures that a public monument may be erected on the spot where the late tragical scene was acted, as a me mento to posterity, of that horrid massacre, and the destructive consequences of military troops being quartered in a well regulated city?”

Boston Goal, Monday 12 th March, 1770.

Messieurs Edes and Gill,

PERMIT me thro' the channel of your paper, to return my thanks in the most publick manner to the Inhabitants in general of this town—who throwing aside all party and prejudice, have with the utmost humanity and freedom slept forth advocates for truth, in defence of my injured innocence, in the late unhappy affair that happened on Monday night last: And to assure them, that I shall ever have the highest sense of the justice have done me, which will be ever gratefully remembered by their much obliged, and obedient humble servant, THOMAS PRESTON.

Dec. 30. Letters from Dantzick inform us, that orders have been given by her imperial majesty to fit out another fleet of twelve ships of the fine with the utmost expedition, the command of which it is said, will be given to Mr. Kofmin, a Russian officer, who was educated in the British navy under the brave admiral Warren.

A bet of 100 guineas was yesterday evening made at a coffee-house not far from Charring cross, that the author of Junius would be in custody before the first of next February.

It was yesterday reported, that the author of the last Junius is known, and that proper measures were taking in order to come at his person.

A great man absolutely declared this week that Junius's last letter had operated totally different from its intentions; for that “thereby the ministry were now become immoveable.”

It is reported that a great Personage has within these few days, had the real name of Junius, with the intelligence properly authenticated, sent by an anonymous hand, through the channel of the common post.

A certain very popular nobleman, and a great officer in the law department, have of late had several conferences on the subject of the Middlefex petition.

The national debt of this and our sister kingdom, Ireland, seems to terrify several among the moneyed men, who, in our present distractions, with so heavy a burthen, do not think their property over-safe in the public funds, especially in case of another war as expensive as the last.

It is said, that should the advice of Lord Catham be taken on an important subject, Mr. Wilkes will certainly take his seat without a dissolution of parliament.

A correspondent remarks that Junius, in all his letters never once shewed he wanted a head, till his last long laboured epistle, in which he struck at the supreme head both in church and state.

We hear that a petition from Mr. Wilks will be presented to the House of Commons, at the beginning of the ensuing sessions, desiring the house to examine the several parts of his former petition which have not as yet been enquired into: such as the evasion of the Habeas Corpus; the close commitment of their member for three days, with out the permission of seeing any person but his jailors; although charged only with a misdemeanour the breach of privilege, by serving a member of parliament with a subpœna; the counter notices signed Summoning Officer, sent to several of his jury only the day before the trial; and the papers seized under the general warrant, produced as evidence on his trial.

We are assured, from undoubted veracity, that the present state of the nation will undergo a very serious consideration at an ensuing meeting.

It is said that a noble Lord, who lately matched a certain cast-off Dutchess is, in the jockey-phrase already sick of the lay, and would willingly pay forfeit.

From the 15th of November to the 22d instant inclusive, the East India company have entered for their outward bound trade, of the woollen manufacture and other home commodities, to the amount of 213,000l. and as yet not near half of the? are freighted.

Paul Revere's Letters to his Wife and Son

"story of the battle of concord and lexington and revear’s ride twenty years ago", rachel revere's captured letter, you may also like.

American Revolution: The Boston Massacre

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/khickman-5b6c7044c9e77c005075339c.jpg)

- M.A., History, University of Delaware

- M.S., Information and Library Science, Drexel University

- B.A., History and Political Science, Pennsylvania State University

In the years following the French and Indian War , the Parliament increasingly sought ways to alleviate the financial burden caused by the conflict. Assessing methods for raising funds, it was decided to levy new taxes on the American colonies with the goal of offsetting some of the cost for their defense. The first of these, the Sugar Act of 1764 , was quickly met by outrage from colonial leaders who claimed "taxation without representation," as they had no members of Parliament to represent their interests. The following year, Parliament passed the Stamp Act which called for tax stamps to be placed on all paper goods sold in the colonies. The first attempt to apply a direct tax to the North American colonies, the Stamp Act was met with widespread protests.

Across the colonies, new protest groups, known as the " Sons of Liberty " formed to fight the new tax. Uniting in the fall of 1765, colonial leaders appealed to Parliament stating that as they had no representation in Parliament, the tax was unconstitutional and against their rights as Englishmen. These efforts led to the Stamp Act's repeal in 1766, though Parliament quickly issued the Declaratory Act which stated that they retained the power to tax the colonies. Still seeking additional revenue, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts in June 1767. These placed indirect taxes on various commodities such as lead, paper, paint, glass, and tea. Again citing taxation without representation, the Massachusetts legislature sent a circular letter to their counterparts in the other colonies asking them to join in resisting the new taxes.

London Responds

In London, the Colonial Secretary, Lord Hillsborough, responded by directing colonial governor to dissolve their legislatures if they responded to the circular letter. Sent in April 1768, this directive also ordered the Massachusetts legislature to rescind the letter. In Boston, customs officials began to feel increasingly threatened which led their chief, Charles Paxton, to request a military presence in the city. Arriving in May, HMS Romney (50 guns) took up a station in the harbor and immediately angered Boston's citizens when it began impressing sailors and intercepting smugglers. Romney was joined that fall by four infantry regiments which were dispatched to the city by General Thomas Gage . While two were withdrawn the following year, the 14th and 29th Regiments of Foot remained in 1770. As military forces began to occupy Boston, colonial leaders organized boycotts of the taxed goods in an effort to resist the Townshend Acts.

The Mob Forms

Tensions in Boston remained high in 1770 and worsened on February 22 when young Christopher Seider was killed by Ebenezer Richardson. A customs official, Richardson had randomly fired into a mob that had gathered outside his house hoping to make it disperse. Following a large funeral, arranged by Sons of Liberty leader Samuel Adams , Seider was interred at the Granary Burying Ground. His death, along with a burst of anti-British propaganda, badly inflamed the situation in the city and led many to seek confrontations with British soldiers. On the night of March 5, Edward Garrick, a young wigmaker's apprentice, accosted Captain Lieutenant John Goldfinch near the Custom House and claimed that the officer had not paid his debts. Having settled his account, Goldfinch ignored the taunt.

This exchange was witnessed by Private Hugh White who was standing guard at the Custom House. Leaving his post, White exchanged insults with Garrick before striking him in the head with his musket . As Garrick fell, his friend, Bartholomew Broaders, took up the argument. With tempers rising, the two men created a scene and a crowd began to gather. In an effort to quiet the situation, local book merchant Henry Knox informed White that if he fired his weapon he would be killed. Withdrawing to safety of the Custom House stairs, White awaited aid. Nearby, Captain Thomas Preston received word of White's predicament from a runner.

Blood on the Streets

Gathering a small force, Preston departed for the Custom House. Pushing through the growing crowd, Preston reached White and directed his eight men to form a semi-circle near the steps. Approaching the British captain, Knox implored him to control his men and reiterated his earlier warning that if his men fired he would be killed. Understanding the delicate nature of the situation, Preston responded that he was aware of that fact. As Preston yelled at the crowd to disperse, he and his men were pelted with rocks, ice, and snow. Seeking to provoke a confrontation, many in the crowd repeatedly yelled "Fire!" Standing before his men, Preston was approached by Richard Palmes, a local innkeeper, who inquired if the soldiers' weapons were loaded. Preston confirmed that they were but also indicated that he was unlikely to order them to fire as he was standing in front of them.

Shortly thereafter, Private Hugh Montgomery was hit with an object that caused him to fall and drop his musket. Angered, he recovered his weapon and yelled "Damn you, fire!" before shooting into the mob. After a brief pause, his compatriots began firing into the crowd though Preston had not given orders to do so. In the course of the firing, eleven were hit with three being killed instantly. These victims were James Caldwell, Samuel Gray, and Crispus Attucks . Two of the wounded, Samuel Maverick and Patrick Carr, died later. In the wake of the firing, the crowd withdrew to the neighboring streets while elements of the 29th Foot moved to Preston's aid. Arriving on the scene, Acting Governor Thomas Hutchinson worked to restore order.

Immediately beginning an investigation, Hutchison bowed to public pressure and directed that British troops be withdrawn to Castle Island. While the victims were laid to rest with great public fanfare, Preston and his men were arrested on March 27. Along with four locals, they were charged with murder. As tensions in the city remained dangerously high, Hutchinson worked to delay their trial until later in the year. Through the summer, a propaganda war was waged between the Patriots and Loyalists as each side tried to influence opinion abroad. Eager to build support for their cause, the colonial legislature endeavored to ensure that the accused received a fair trial. After several notable Loyalist attorneys refused to defend Preston and his men, the task was accepted by well-known Patriot lawyer John Adams .

To assist in the defense , Adams selected Sons of Liberty leader Josiah Quincy II, with the organization's consent, and Loyalist Robert Auchmuty. They were opposed by Massachusetts Solicitor General Samuel Quincy and Robert Treat Paine. Tried separately from his men, Preston faced the court in October. After his defense team convinced the jury that he had not ordered his men to fire, he was acquitted. The following month, his men went to court. During the trial, Adams argued that if the soldiers were threatened by the mob, they had a legal right to defend themselves. He also pointed out that if they were provoked, but not threatened, the most they could be guilty of was manslaughter. Accepting his logic, the jury convicted Montgomery and Private Matthew Kilroy of manslaughter and acquitted the rest. Invoking the benefit of clergy, the two men were publicly branded on the thumb rather than imprisoned.

Following the trials, tension in Boston remained high. Ironically, on March 5, the same day as the massacre, Lord North introduced a bill in Parliament that called for a partial repeal of the Townshend Acts. With the situation in the colonies reaching a critical point, Parliament eliminated most aspects of the Townshend Acts in April 1770, but left a tax on tea. Despite this, conflict continued to brew. It would come to head in 1774 following the Tea Act and the Boston Tea Party . In the months after the latter, Parliament passed a series of punitive laws, dubbed the Intolerable Acts , which set the colonies and Britain firmly on the path to war. The American Revolution would begin on April 19, 1775, when to two sides first clashed at Lexington and Concord .

- Massachusetts Historical Society: The Boston Massacre

- Boston Massacre Trials

- iBoston: Boston Massacre

- The Root Causes of the American Revolution

- American Revolution: Boston Tea Party

- American Revolution: The Intolerable Acts

- Questions Left by The Boston Massacre

- All About the Sons of Liberty

- American Revolution: Siege of Boston

- The Battles of Lexington and Concord

- American Revolution: The Townshend Acts

- American Revolution Battles

- John Hancock: Founding Father With a Famous Signature

- The Currency Act of 1764

- Quartering Act, British Laws Opposed by American Colonists

- Biography of Paul Revere: Patriot Famous for His Midnight Ride

- American Revolution: The Stamp Act of 1765

- American Revolution: Early Campaigns

- An Introduction to the American Revolutionary War

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Boston Massacre, (March 5, 1770), skirmish between British troops and a crowd in Boston, Massachusetts.Widely publicized, it contributed to the unpopularity of the British regime in much of colonial North America in the years before the American Revolution.. Prelude. In 1767, in an attempt to recoup the considerable treasure expended in the defense of its North American colonies during the ...

Investigating Perspectives on the Boston Massacre: Historical Context Essay. The Townshend Acts: Fall 1767. The Boston Massacre could not have happened if British soldiers were not stationed in the city. And the soldiers would not have been there if not for the Townshend Acts-and the distrust between colonists and the customs officials ...

Boston, Massachusetts was a hotbed of radical revolutionary thought and activity leading up to 1770. In March 1770, British soldiers stationed in Boston opened fire on a crowd, killing five townspeople and infuriating locals. What became known as the Boston Massacre intensified anti-British sentiment and proved a pivotal event leading up to the ...

The Boston Massacre was a deadly riot that occurred on March 5, 1770, on King Street in Boston between American colonists and British soldiers. It helped pave the way for the American Revolution.

Account of the Boston Massacre. by John Tudor. March 05, 1770. March 06, 1770. March 08, 1770. Edited and introduced by Robert M.S. McDonald. Image: Paul Revere, The bloody massacre perpetrated in King Street Boston on March 5th 1770 by a party of the 29th Regt., 1770. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-01657.

On the evening of 5 March 1770, a confrontation between British soldiers and a boisterous crowd in front of the Custom House on King Street in Boston, Massachusetts had deadly results and the event quickly became known as the "Boston Massacre." In its aftermath, the commander of the 29th Regiment, Captain Thomas Preston, as well as the eight ...

Essentially, the Boston Massacre occurred because the people of Boston were extremely upset with the British authorities in the late 1760s and early 1770s. They felt that the British were threatening their livelihoods, freedom, and the autonomy of their colony. Immediately after the Boston Massacre, there was a fight to control the narrative ...

Instructions: Body Paragraphs: Use the frame paragraph • Paragraph 2: Body Paragraph: Give one reason to blame a side for the Boston Massacre. Yellow: Topic Sentence State your claim. were Give one reason to blame the British soldiers or the Boston colonists for the Boston Massacre. First, the Red: Present your evidence. Prove your claim. Use

Reactions and Responses. In the days and weeks following the events of 5 March 1770, Boston residents wrote diary entries and letters trying to make sense of what exactly had happened that evening on King Street. It didn't take long for more public responses to also appear, in London as well as in Boston, in the form of poetry, calls for a ...

On March 5, 1770, British soldiers shot into a crowd of rowdy colonists in front of the Custom House on King Street, killing five and wounding six. The Boston Massacre marked the moment when political tensions between British soldiers and American colonists turned deadly. Patriots argued the event was the massacre of civilians perpetrated by ...

An Account of a late Military Massacre at Boston, or the Consequences of Quartering Troops in a populous Town. BOSTON March 12, 1770. THE Town of Boston affords a recent and melancholy Demonstration of the destructive consequences of quartering troops among citizens in time of Peace, under a pretence of supporting the laws and aiding civil ...

Eyewitness accounts of the Boston Massacre (1770) In the weeks following the shooting deaths of five people in King Street on March 5th 1770, more than 90 people from all ranks of colonial society gave depositions about what they had seen. Later that year, townspeople made up the bulk of the witness lists for both the prosecution and defence ...

The Mob Forms. Tensions in Boston remained high in 1770 and worsened on February 22 when young Christopher Seider was killed by Ebenezer Richardson. A customs official, Richardson had randomly fired into a mob that had gathered outside his house hoping to make it disperse.

The Boston Massacre, March 5, 1770, was an event that exemplified the growing tension between the American colonies and England which would subsequently result in the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. In 1767 the English Parliament had levied an import tax on tea, glass, paper, and lead.

Instructions: Body Paragraphs: Use the frame paragraph • Paragraph 2: Body Paragraph: Give one reason to blame a side for the Boston Massacre. Yellow: Topic Sentence State your claim. Give one reason to blame the British soldiers or the Boston colonists for the Boston Massacre. First, the were Red: Present examples of your evidence.

The Massacre was the 1770, pre-Revolutionary incident growing out of the anger against the British troops sent to Boston to maintain order and to enforce the Townshend Acts. The troops, constantly tormented by irresponsible gangs, finally on Mar. 5, 1770, fired into a rioting crowd and killed five men: three on the spot, two of wounds later ...

Then, formulate a thesis of three important points (if you are writing the 5 paragraph essay) on the idea of odd occurrences as the causes of the Boston Massacre.

Instructions: Body Paragraphs: Use the frame paragraph • Paragraph 2: Body Paragraph: Give one reason to blame a side for the Boston Massacre. Green: State your claim. Give one reason to blame the British soldiers or the Boston colonists for the Boston Massacre. First, the were Yellow: Present your evidence. Prove your claim. Use

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by Paul Revere. "The Bloody Massacre" engraved by Paul Revere, 1770 (The Gilder Lehrman Institute) By the beginning of 1770, there were 4,000 British soldiers in Boston, a city with 15,000 inhabitants, and tensions were running high. On the evening of March 5, crowds of day laborers, apprentices, and merchant ...

The Boston Massacre was a confrontation between British soldiers and a crowd of colonial civilians in the heart of Boston, Massachusetts, resulting in the tragic deaths of five colonists. This incident is seen as a pivotal event in the lead-up to the American Revolutionary War as it dramatically intensified tensions between the American ...

On March 12th, a week after the Boston Massacre, the Boston Gazette and Country Journal. published an account of the shootings and the events that preceded them: "On the evening of Monday, being the fifth, several soldiers of the 29th Regiment were seen parading the streets with their drawn cutlasses and bayonets, abusing and wounding numbers of the inhabitants.