Read The Diplomat , Know The Asia-Pacific

- Central Asia

- Southeast Asia

Environment

- Asia Defense

- China Power

- Crossroads Asia

- Flashpoints

- Pacific Money

- Tokyo Report

- Trans-Pacific View

- Photo Essays

- Write for Us

- Subscriptions

The Philippines’ COVID-19 Response Has Left the Most Vulnerable Behind

Recent features.

The Geopolitics of Cambodia’s Funan Techo Canal

The Killing of Dawa Khan Menapal and the Fall of Afghanistan’s Republic

How Bangladesh’s Quota Reform Protest Turned Into a Mass Uprising Against a ‘Killer Government’

Jammu and Kashmir: Five Years After the Abrogation of Its Autonomy

A Grand Coalition and a New Era in Mongolia

Dealing With China Should Be a Key Priority for the New EU Leadership

The US CHIPS Act, 2 Years Later

Understanding China’s Approach to Nuclear Deterrence

Fear Not? The Economic Impact of Vietnam’s Political Churn

How Should the World Perceive Today’s Hong Kong?

Radha Kumar on Kashmir, 5 Years After Article 370 Was Scrapped

On China-India Border, Ladakh Blames Modi’s BJP for Unemployment, Stagnancy

The debate | opinion.

Far from being a “great leveler,” the pandemic is much more likely to impact socioeconomically disadvantaged communities.

A vaccination center established on a basketball court in Las Pinas, Metro Manila, Philippines, April 2021.

Since early 2020, health experts have emphasized the need to support fragile countries during the pandemic to prevent the further spread of COVID-19 across the world. In response, the G7 nations last year affirmed their commitment to provide “affordable and equitable access to vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics” globally.

Despite this rhetoric, wealthy nations continue to put their needs and interests over those of lower income countries. They are hoarding vaccines from poorer countries (with some countries like the United States and Canada now offering their citizens third and fourth booster shots) and as a result, around 78 percent of the population in high and upper-middle income countries have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in contrast to only 11 percent of people in low-income countries. Even the targets for COVAX , the global initiative to send vaccines to lower and middle-income countries, have been repeatedly cut back due to production issues, export bans, and vaccine hoarding by wealthy nations.

Consequences of Vaccine Inequity on the Philippines

The Philippines is one of the many countries dealing with the effects of vaccine inequity. Despite being one of the hardest hit countries in Southeast Asia in 2021, the Philippines has had to wait for vaccines from wealthy countries. The country now has over 3.5 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and around 54,003 deaths. While its daily infection numbers had reduced significantly by the end of 2021, the rapidly spreading Omicron variant is concerning. The country’s vaccination rate remains relatively low, with only 52 percent of the population fully vaccinated, and recent evidence suggests that vaccines like AstraZeneca and Sinovac, used in low-income countries like the Philippines, provide less protection against Omicron than the mRNA vaccines produced by Pfizer and Moderna.

However, not all Filipinos have been impacted equally by vaccine inequity and the pandemic in general. In November 2021, 93 percent of residents in the capital region had been fully vaccinated in comparison to only 10.9 percent of people in the predominantly Muslim regions in southern Philippines. More broadly, research shows that the government has ignored the unique needs and vulnerabilities of marginalized groups in the Philippines such as the poor , Indigenous Peoples , and disabled people , which has affected their access to food and income, among other issues, throughout the pandemic.

Although the Philippine government is aware of the necessity of supporting vulnerable groups in order to curb the spread of the virus, it has repeatedly chosen to scapegoat and criminalize the poor who have to pursue their livelihood outside the home (due specifically to insufficient government assistance ) for “violating” lockdown measures. Just like wealthy countries’ attempts to “ boost [their] way out of the pandemic ,” the Philippine government’s solution to fighting the pandemic through criminalization is both unethical and ineffective at actually mitigating the spread of the virus.

Lack of Adequate Support for Typhoon Victims

Another group that has been heavily impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines are the over 75,000 residents of resettlement sites in Tacloban City, homes that were built for the hundreds of thousands of Typhoon Haiyan survivors. Our June 2021 study on the impact of COVID-19 on 357 households in these resettlement sites found that participants did not receive sufficient support from the government to get through the pandemic. Specifically, over a third of participants found the national government’s response to the pandemic to be somewhat inadequate or very inadequate and very few felt that any level of government could protect them from COVID-19 in their community.

Financial problems and lack of livelihoods were cited by participants as the most serious problems they were facing during the pandemic, both of which have been worsened by the government’s pandemic response. For example, though 91.6 percent of participants received financial assistance from the government, 47 percent said it was insufficient. Specifically, the participants, the majority of whom make 15,000 pesos (around $300) or less monthly on average, noted that they did not have sufficient financial resources to buy food, maintenance medicine, and other necessities.

Many participants also said that as a result of COVID-19, they had lost their livelihoods or made a lot less money from their work, as they mostly work in-person. One participant noted that without a livelihood, they could not “support [their] big family and… cope with daily living.” Other issues mentioned by participants include the inadequate amount and quality of food, the lack of running water at home, and the inability to participate fully in online learning (particularly due to poor internet connections).

These findings reinforce yet again that the pandemic is no “ great leveler .” In large part due to their financial and living conditions, socioeconomically disadvantaged communities are more likely to be affected by the pandemic. And by not addressing the specific needs of resettlement site residents, the Philippine government’s inadequate response has directly impacted their ability to meet their basic daily needs. As such, a group that was already vulnerable before the pandemic is now even more so, both financially and in terms of getting COVID-19.

How does the government solve this issue? In the above study, residents offered a variety of recommendations for how the government could better meet the challenges facing them, from providing more sustainable livelihood programs and offering sufficient financial assistance to the stricter implementation of COVID-19 health and safety protocols.

Ultimately, national and local governments in the Philippines must include marginalized groups when developing and executing their pandemic responses, specifically to understand their needs and the best ways to address them. This is necessary because, as a research study on community engagement found , “marginalized people living through the experience of COVID-19 have embodied knowledge, skills, and experience to inform equitable public policy.”

Wealthy nations must also support vulnerable nations by actually adhering to their commitments of sharing vaccine supplies as well as by sharing patents for vaccines so that countries in the Global South can produce them.

Winning the Fight Against COVID-19 in Conflict Zones

By dotan haim, nico ravanilla and renard sexton.

A Return to Beijing in the Age of ‘Zero COVID’

By james maclaren.

South Korea Can Do More in the Battle Against COVID-19

By troy stangarone.

Tackling the Pandemic of Inequality in Asia and the Pacific

By armida salsiah alisjahbana.

International Airlines Leave China, Despite Beijing’s Urging

By bonnie girard.

China Breaks With Latin America and BRICS Allies Over Venezuela Election Fraud

By paul hare.

The Silent Winner of Myanmar’s Northern Conflict

By amara thiha.

The Intensifying Impacts of Upstream Dams on the Mekong

By nguyen minh quang, nguyen phuong nguyen, le minh hieu, and james borton.

By Nguyen Minh Quang and James Borton

By Freshta Jalalzai

By Mehedi Hasan Marof

By Sudha Ramachandran

Supporting the Philippines’ COVID-19 Emergency Response

Beneficiaries

For Vilma Campos , a Quezon City resident and mother of five, life has improved since her family received their vaccinations. “My daughter has resumed working, so has my husband,” she said. “Life is no longer that difficult.”

Before COVID-19 hit, Vilma’s job was taking care of children. When the authorities started implementing quarantine restrictions, she, her daughter, and her spouse lost their jobs. Vilma said her family was always wondering where to get the next meal. “What gave us hope was the arrival of vaccines,” she said. “Things have improved and I really wish we can all overcome this pandemic.”

The Philippines was one of the countries hit hardest by COVID-19 in the East Asia and Pacific region. To manage the spread of the virus, authorities implemented strict quarantine restrictions and health protocols, restricted mobility of people as wells as the operational capacity of businesses. As a result, the Philippine economy suffered. In 2020, GDP contracted 9.5 percent, driven by significant declines in consumption and investment growth, and exacerbated by the sharp slowdown in exports, tourism, and remittances. Many Filipinos lost jobs and experienced food shortages and difficulties accessing health care. Due to global shortages, procurement of COVID-19 vaccines, medical supplies, personal protective equipment (PPE), reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test machines, and test kits proved challenging in the early phases of the pandemic.

The project supported the country’s efforts to scale up vaccination across the national territory, strengthen the country’s health system, and overcome the impact of the pandemic especially on the poor and the most vulnerable. Besides vaccines, the project supported procurement of PPE, essential medical equipment such as mechanical ventilators, cardiac monitors, portable x-ray machines; laboratory equipment and test kits; and ambulances. The project also supported construction and refurbishment of negative pressure isolation rooms and quarantine facilities, as well as the expansion of the country’s laboratory capacity at the national and sub-national levels for prevention of and preparedness against emerging infectious diseases. It funded retrofitting of the national reference laboratory – the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM) – as well as six sub-national and public health laboratories in Baguio, Cebu, Davao, and Manila, and the construction and expansion of laboratory capacity in priority regions without such facilities.

During year1 to year 2, the following results were achieved:

- The project supported the procurement and deployment of 33 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine across the country. The project supported pediatric vaccination for 7.5 million children. With the support of development partners including the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank, the Philippines administered more than 137 million vaccines (more than 126 million first and second doses, and more than 10 million booster doses) by March of 2022.

- The project helped scale up testing capacity from 1,000 RT-PCR tests per day to 24,979 per day.

- The project supported the procurement of 500 mechanical ventilators, 119 portable x-ray machines, 70 infusion pumps, 50 RT-PCR machines, and 68 ambulances.

- As a result of the strong vaccination rates and strengthened health response capacity, the Philippines is now much better able to manage the pandemic.

The Philippines COVID-19 Emergency Response Project supported the procurement and deployment of 33 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine across the country. The project also supported pediatric vaccination for 7.5 million Filipino children.

Bank Group Contribution

The World Bank through the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) provided $900 million of funding in total for the emergency response project. The project provided $100 million for medical and laboratory equipment and supplies; $500 million for primary vaccine doses, ancillaries, and end-to-end logistics; and $300 million for boosters and additional doses, and end-to-end logistics.

The World Bank collaborated with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) on project preparation and vaccines financing. The Bank worked with the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) on the Vaccine Introduction Readiness Tool (VIRAT) and Vaccine Readiness Assessment Tool (VRAF) Tool 2.0, which is used to assess status, gaps, and issues in four domains: planning and management, supply and distribution, program delivery, and supporting systems and infrastructure. Australia, through the AGaP Trust Fund, provided a US$300,000 grant to support implementation. The World Bank also collaborated with UNICEF to address vaccine hesitancy and with the WHO to procure RT-PCR machines and test kits.

Looking Ahead

The Philippine government is considering additional support for scaling up testing capacity. Equipment has been acquired and civil works commissioned through the project are now in use. An action plan is being developed for continued implementation of environmental and social safeguards employed in the project, such as COVID-19 waste management and assessment of accessibility of vulnerable groups to health care services. These will be institutionalized using the manuals developed and through directive issuances by the Department of Health. The project also supports the development of National Action Plan Towards Increased Accessibility of Health Care Facilities for Vulnerable Groups. The World Bank is also supporting the Department of Health and priority LGUs in strengthen local health systems for Universal Health Coverage.

Philippines Covid-19 Emergency Response Project

Philippines Covid-19 Emergency Response Project Additional Financing

Philippines COVID-19 Emergency Response Project – Additional Financing 2

Department of Health Covid-19 Tracker.

Department of Health Covid-19 Updates on Covid-19 Vaccines

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Licence or Product Purchase Required

You have reached the limit of premium articles you can view for free.

Already have an account? Login here

Get expert, on-the-ground insights into the latest business and economic trends in more than 30 high-growth global markets. Produced by a dedicated team of in-country analysts, our research provides the in-depth business intelligence you need to evaluate, enter and excel in these exciting markets.

View licence options

Suitable for

- Executives and entrepreneurs

- Bankers and hedge fund managers

- Journalists and communications professionals

- Consultants and advisors of all kinds

- Academics and students

- Government and policy-research delegations

- Diplomats and expatriates

This article also features in The Report: Philippines 2021 . Read more about this report and view purchase options in our online store.

Analysing the Philippines' health and economic response to Covid-19

The Philippines | Economy

The Philippines reported its first Covid-19 case on January 30, 2020, and confirmed its first coronavirus-related fatality three days later. The country was officially placed under a state of calamity for a period of six months on March 17, mandating that national and local authorities mobilise the resources needed to respond to the health crisis. The state of calamity was extended for an additional 12 months in September, facilitating one of the world’s longest, most stringent lockdowns. In March and September of that year the government passed two wide-ranging stimulus packages aimed at helping to mitigate the economic impact of the crisis and aid in the health response.

Movement Restrictions

Covid-19-related restrictions varied, with the government designating each region or metropolitan area one of four quarantine phases, based on contagion figures and in consultation with health officials and local authorities. These labels were re-evaluated every two to four weeks, and local officials had the autonomy to tighten restrictions within their area. The entire island of Luzon – home to over half of the population – was placed under the most stringent grade of restrictions, enhanced community quarantine, on March 16. This remained in force until May 12 across some areas – including the National Capital Region, which accounts for more than one-third of GDP.

By early November 2020 total confirmed cases exceeded 380,000, with over 7000 fatalities. Within the ASEAN region, only Indonesia had officially reported higher case and fatality counts. The Philippines had, however, ramped up testing by this time, with the Department of Health reporting that the country had performed the highest number of tests in South-east Asia as of early August. A curfew remained in place in many areas throughout November and all of the country retained some degree of quarantine restrictions.

Relief Funding

Two weeks after the World Health Organisation officially declared the pandemic, in late March 2020 President Rodrigo Duterte signed the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act – known as Bayanihan 1 – into law. Among the measures included in the stimulus package were economic assistance for disadvantaged families and displaced workers; protocols for coordination between the central government and local government units; a mandate for the public health insurance provider to shoulder the treatment costs for any medical centre employees who contracted the coronavirus; and measures to limit the hoarding and profiteering of essential food, fuel and medical supplies.

Bayanihan 1 was followed by the Bayanihan to Recover as One Act, or Bayanihan 2. Signed into law on September 11, 2020 and valid through December 19 of that year, the P165.5bn ($3.3bn) package included almost P39.5bn ($785.6m) for loans targeting small businesses; P24bn ($477.3m) for the agriculture sector; and P13bn ($258.6m) to assist displaced workers. Bayanihan 2 also mandated the extension of grace periods and zero-interest staggered instalments for rental payments and utility bills incurred by residential occupants and micro-, small and medium-sized businesses during the two strictest lockdown phases.

Recovery Priorities

The administration reinforced the importance of its flagship Build, Build, Build infrastructure development programme throughout the pandemic period, both as a strategy to create jobs in the immediate term and as a means to accelerate economic growth into the future (see Transport & Infrastructure chapter). Meanwhile, efforts to strengthen the digital economy gained momentum, providing an opportunity to grow value added in key segments and broaden financial inclusion. Supplemented by ongoing support for vulnerable groups and targeted strategies that aim to enhance food security and health care, these developments are expected to create a more resilient economy. These shifts will not only help to drive the post-pandemic recovery, but also pave the way for ongoing economic expansion in the years to come.

Request Reuse or Reprint of Article

Read More from OBG

In Philippines

The Philippine roadmap for inclusive, balanced, long-term growth is aligned with environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Ghana underscores its pivotal role as a regional and international trade partner Oxford Business Group has launched The Report: Ghana 2024. This latest edition offers a detailed analysis of the country’s economic trajectory, focusing on fiscal consolidation and structural reforms. It examines the nation's progress in managing expenditure and debt, alongside the impact of IMF programmes and strategic reforms aimed at enhancing revenue mobilisation. Despite challenges such as financial sector stress and the upcoming elections, Ghana remains optimistic…

Report: Examining Indonesia's path to responsible paint production With Indonesia's National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJPN) 2025-45 underscoring the role of manufacturing for economic growth, the paint and coatings segment has a role to play in sustainable economic development. From eco-friendly formulations to strategic risk management, the sector continues to navigate towards responsible production.This report explores the industry's commitment to environmental and social responsibility, balancing economic growth with eco-friendly products and …

Register for free Economic News Updates on Asia

“high-level discussions are under way to identify how we can restructure funding for health care services”, related content.

Featured Sectors in Philippines

- Asia Agriculture

- Asia Banking

- Asia Construction

- Asia Cybersecurity

- Asia Digital Economy

- Asia Economy

- Asia Education

- Asia Energy

- Asia Environment

- Asia Financial Services

- Asia Health

- Asia Industry

- Asia Insurance

- Asia Legal Framework

- Asia Logistics

- Asia Media & Advertising

- Asia Real Estate

- Asia Retail

- Asia Safety and Security

- Asia Saftey and ecurity

- Asia Tourism

- Asia Transport

Featured Countries in Economy

- Indonesia Economy

- Malaysia Economy

- Myanmar Economy

- Papua New Guinea Economy

Popular Sectors in Philippines

- The Philippines Agriculture

- The Philippines Construction

- The Philippines Economy

- The Philippines Financial Services

- The Philippines ICT

- The Philippines Industry

Popular Countries in Economy

- Kuwait Economy

- Qatar Economy

- Saudi Arabia Economy

- UAE: Abu Dhabi Economy

- UAE: Dubai Economy

Featured Reports in The Philippines

Recent Reports in The Philippines

- The Report: Philippines 2021

- The Report: Philippines 2019

- The Report: Philippines 2018

- The Report: The Philippines 2017

- The Report: The Philippines 2016

- The Report: The Philippines 2015

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

- Transparency Seal

- Citizen's Charter

- PIDS Vision, Mission and Quality Policy

- Strategic Plan 2019-2025

- Organizational Structure

- Bid Announcements

- Site Statistics

- Privacy Notice

- Research Agenda

- Research Projects

- Research Paper Series

- Guidelines in Preparation of Articles

- Editorial Board

- List of All Issues

- Disclaimer and Permissions

- Inquiries and Submissions

- Subscription

- Economic Policy Monitor

- Discussion Paper Series

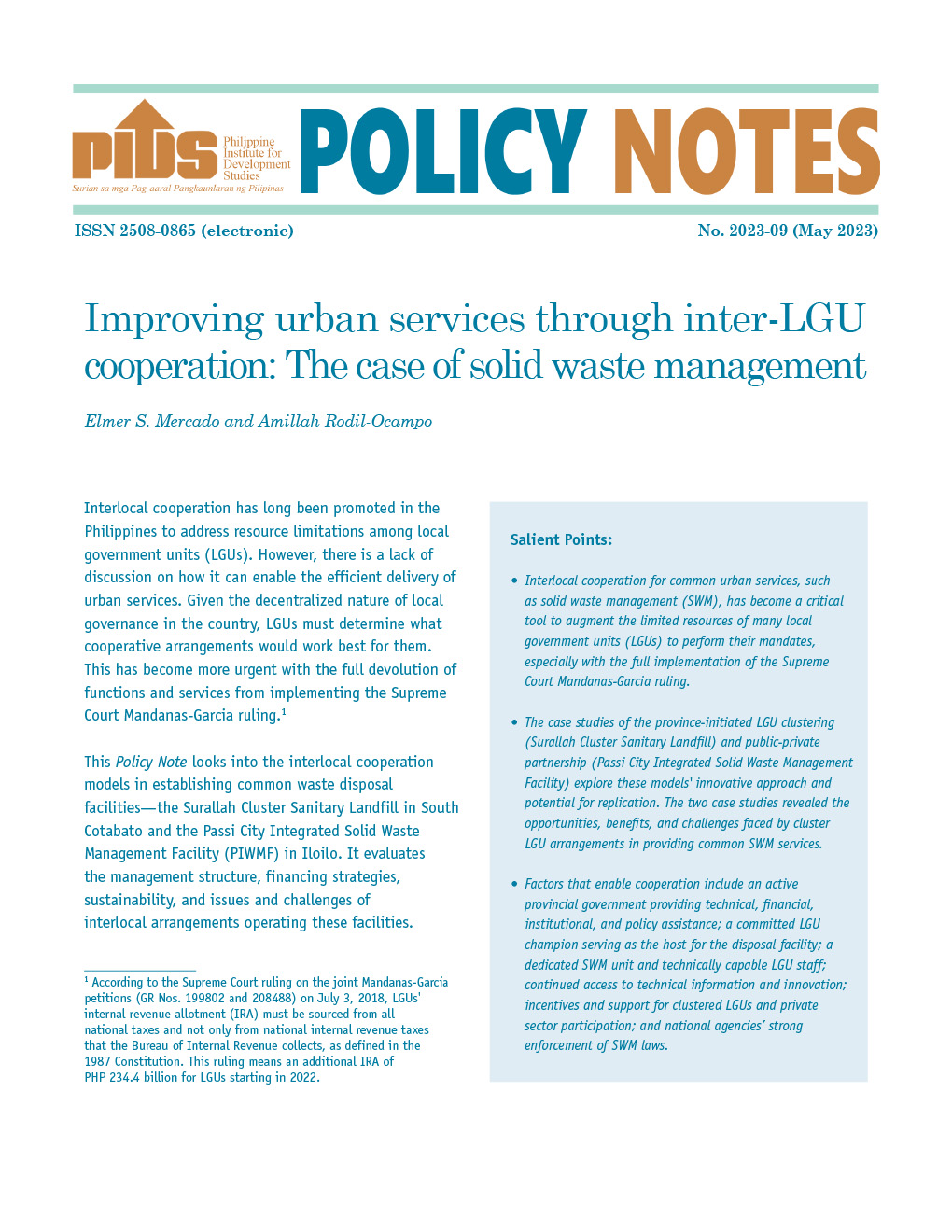

- Policy Notes

- Development Research News

- Policy Pulse

- Economic Issue of the Day

- Annual Reports

- Special Publications

Working Papers

Monograph Series

Staff Papers

Economic Outlook Series

List of All Archived Publications

- Other Publications by PIDS Staff

- How to Order Publications

- Rate Our Publications

- Press Releases

- PIDS in the News

- PIDS Updates

- Legislative Inputs

- Database Updates

- Socioeconomic Research Portal for the Philippines

- PIDS Library

- PIDS Corners

- Infographics

- Infographics - Fact Friday

- Infographics - Infobits

The Philippines’ Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Learning from Experience and Emerging Stronger to Future Shocks

- Celia M. Reyes

- COVID-19 pandemic

- whole-of-government approach

- COVID-19 policy responses

- macroeconomic response

- public health shock

- Philippine economy

- crisis response

- food security

- overseas Filipino workers

- human development

- income distribution

- basic education

- crisis communication

- risk communication

- COVID-19 recovery

- local government units

- fiscal response to pandemic

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic hit the Philippine economy and society unprecedentedly. To protect the people, the government had to act decisively and identify solutions to contain the rapid spread of the virus and the devastating economic and social disruption caused by the pandemic. This book compiles papers assessing the strategies, policies, and recovery efforts that the government had implemented during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. It discusses the challenges that the country had experienced and the government's responses in the areas of health, macroeconomy, food security, labor, social protection, poverty, education, digitalization, fiscal policy, and crisis and risk communication. Learning from these experiences, this book provides recommendations to help the Philippines recover from the current crisis and build better resilience to future shocks.

This publication has been cited 4 times

- Alviar, DC. 2023. Sapat ba ang teknolohiya upang epektibong magturo? Mga aral mula sa PIDS . Tutubi News Magazine.

- Daily Guardian . 2024. COVID-19 school closures led to significant learning losses – expert . DailyGuardian .

- Manila Standard Business. 2023. PIDS: Technology key to learning amid crises . Manila Standard.

- Nazario, Dhel. 2023. NAST PHL set to introduce new members, recognize outstanding Filipino scientists . Manila Bulletin.

Download Publication

Please let us know your reason for downloading this publication. May we also ask you to provide additional information that will help us serve you better? Rest assured that your answers will not be shared with any outside parties. It will take you only two minutes to complete the survey. Thank you.

Related Posts

Publications.

Video Highlights

- How to Order Publications?

- Opportunities

- Open access

- Published: 21 September 2021

Local government responses for COVID-19 management in the Philippines

- Dylan Antonio S. Talabis 1 , 2 ,

- Ariel L. Babierra 1 , 2 ,

- Christian Alvin H. Buhat 1 , 2 ,

- Destiny S. Lutero 1 , 2 ,

- Kemuel M. Quindala III 1 , 2 &

- Jomar F. Rabajante 1 , 2 , 3

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 1711 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

557k Accesses

28 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Responses of subnational government units are crucial in the containment of the spread of pathogens in a country. To mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Philippine national government through its Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases outlined different quarantine measures wherein each level has a corresponding degree of rigidity from keeping only the essential businesses open to allowing all establishments to operate at a certain capacity. Other measures also involve prohibiting individuals at a certain age bracket from going outside of their homes. The local government units (LGUs)–municipalities and provinces–can adopt any of these measures depending on the extent of the pandemic in their locality. The purpose is to keep the number of infections and mortality at bay while minimizing the economic impact of the pandemic. Some LGUs have demonstrated a remarkable response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of this study is to identify notable non-pharmaceutical interventions of these outlying LGUs in the country using quantitative methods.

Data were taken from public databases such as Philippine Department of Health, Philippine Statistics Authority Census, and Google Community Mobility Reports. These are normalized using Z-transform. For each locality, infection and mortality data (dataset Y ) were compared to the economic, health, and demographic data (dataset X ) using Euclidean metric d =( x − y ) 2 , where x ∈ X and y ∈ Y . If a data pair ( x , y ) exceeds, by two standard deviations, the mean of the Euclidean metric values between the sets X and Y , the pair is assumed to be a ‘good’ outlier.

Our results showed that cluster of cities and provinces in Central Luzon (Region III), CALABARZON (Region IV-A), the National Capital Region (NCR), and Central Visayas (Region VII) are the ‘good’ outliers with respect to factors such as working population, population density, ICU beds, doctors on quarantine, number of frontliners and gross regional domestic product. Among metropolitan cities, Davao was a ‘good’ outlier with respect to demographic factors.

Conclusions

Strict border control, early implementation of lockdowns, establishment of quarantine facilities, effective communication to the public, and monitoring efforts were the defining factors that helped these LGUs curtail the harm that was brought by the pandemic. If these policies are to be standardized, it would help any country’s preparedness for future health emergencies.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of cases have already reached 82 million worldwide at the end of 2020. In the Philippines, the number of cases exceeded 473,000. As countries around the world face the continuing threat of the COVID-19 pandemic, national governments and health ministries formulate, implement and revise health policies and standards based on recommendations by world health organization (WHO), experiences of other countries, and on-the-ground experiences. Early health measures were primarily aimed at preventing and reducing transmission in populations at risk. These measures differ in scale and speed among countries, as some countries have more resources and are more prepared in terms of healthcare capacity and availability of stringent policies [ 1 , 2 ].

During the first months of the pandemic, several countries struggled to find tolerable, if not the most effective, measures to ‘flatten’ the COVID-19 epidemic curve so that health facilities will not be overwhelmed [ 3 , 4 ]. In responding to the threat of the pandemic, public health policies included epidemiological and socio-economic factors. The success or failure of these policies exposed the strengths or weaknesses of governments as well as the range of inequalities in the society [ 5 , 6 ].

As national governments implemented large-scale ‘blanket’ policies to control the pandemic, local government units (LGUs) have to consider granular policies as well as real-time interventions to address differences in the local COVID-19 transmission dynamics due to heterogeneity and diversity in communities. Some policies in place, such as voluntary physical distancing, wearing of face masks and face shields, mass testing, and school closures, could be effective in one locality but not in another [ 7 – 9 ]. Subnational governments like LGUs are confronted with a health crisis that have economic, social and fiscal impact. While urban areas have been hot spots of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are health facilities that are already well in placed as compared to less developed and deprived rural communities [ 10 ]. The importance of local narratives in addressing subnational concerns are apparent from published experiences in the United States [ 11 ], China [ 12 , 13 ], and India [ 14 ].

In the Philippines, the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF) was convened by the national government in January 2020 to monitor a viral outbreak in Wuhan, China. The first case of local transmission of COVID-19 was confirmed on March 7, 2020. Following this, on March 8, the entire country was placed under a State of Public Health Emergency. By March 25, the IATF released a National Action Plan to control the spread of COVID-19. A community quarantine was initially put in place for the national capital region (NCR) starting March 13, 2020 and it was expanded to the whole island of Luzon by March 17. The initial quarantine was extended up to April 30 [ 5 , 15 ]. Several quarantine protocols were then implemented based on evaluation of IATF:

Community Quarantine (CQ) refers to restrictions in mobility between quarantined areas.

In Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ), strict home quarantine is implemented and movement of residents is limited to access essential goods and services. Public transportation is suspended. Only economic activities related to essential and utility services are allowed. There is heightened presence of uniformed personnel to enforce community quarantine protocols.

Modified Enhanced Community Quarantine (MECQ) is implemented as a transition phase between ECQ and GCQ. Strict home quarantine and suspension of public transportation are still in place. Mobility restrictions are relaxed for work-related activities. Government offices operates under a skeleton workforce. Manufacturing facilities are allowed to operate with up to 50% of the workforce. Transportation services are only allowed for essential goods and services.

In General Community Quarantine (GCQ), individuals from less susceptible age groups and without health risks are allowed to move within quarantined zones. Public transportation can operate at reduced vehicle capacity observing physical distancing. Government offices may be at full work capacity or under alternative work arrangements. Up to 50% of the workforce in industries (except for leisure and amusement) are allowed to work.

Modified General Community Quarantine (MGCQ) refers to the transition phase between GCQ and the New Normal. All persons are allowed outside their residences. Socio-economic activities are allowed with minimum public health standard.

LGUs are tasked to adopt, coordinate, and implement guidelines concerning COVID-19 in accordance with provincial and local quarantine protocols released by the national government [ 16 ].

In this study, we identified economic and demographic factors that are correlated with epidemiological metrics related to COVID-19, specifically to the number of infected cases and number of deaths [ 17 , 18 ]. At the regional, provincial, and city levels, we investigated the localities that differ with the other localities, and determined the possible reasons why they are outliers compared to the average practices of the others.

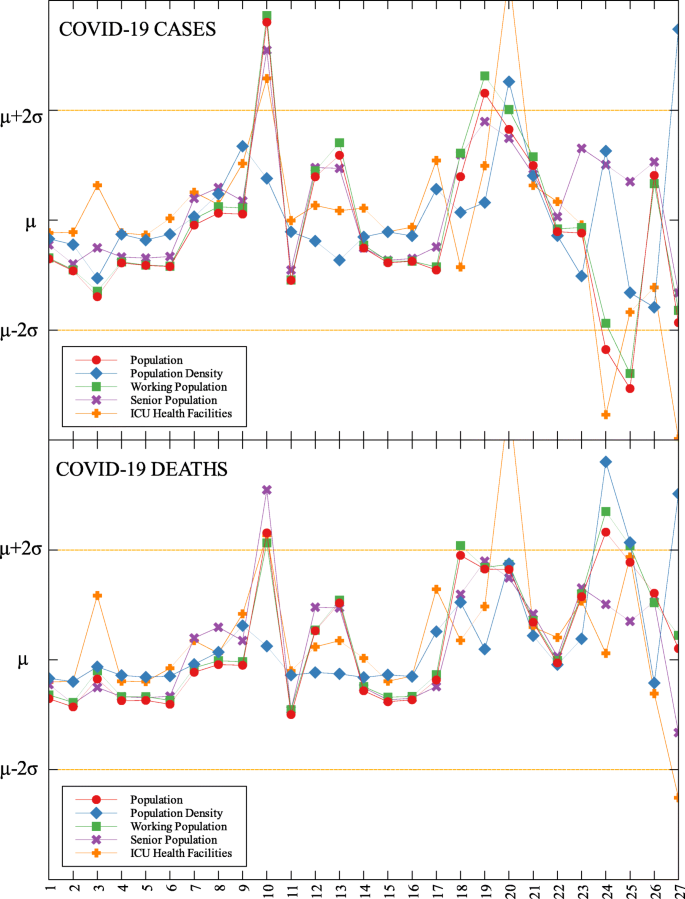

We categorized the data into economic, health, and demographic components (See Table 1 ). In the economic setting, we considered the number of people employed and the number of work hours. The number of health facilities provides an insight into the health system of a locality. Population and population density, as well as age distribution and mobility, were used as the demographic indicators. The data (as of November 10, 2020) from these seven factors were analyzed and compared to the number of deaths and cumulative cases in cities, provinces or regions in the Philippines to determine the outlier.

The Philippine government’s administrative structure and the availability of the data affected its range for each factor. Regional data were obtained for the economic component. For the health and demographic components, data from cities and provinces were retrieved from the sources. Due to the NCR exhibiting the highest figures in all key components, an investigation was conducted to identify an outlier among its cities. The z -transform

where x is the actual data, μ is the mean and σ is the standard deviation were applied to normalize the dataset. Two sets of normalized data X and Y were compared by assigning to each pair ( x , y ), where x ∈ X and y ∈ Y , its Euclidean metric d given by d =( x − y ) 2 . Here, the Y ’s are the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths, and X ’s are the other demographic indicators. Since 95% of the data fall within two standard deviations from the mean, this will be the threshold in determining an outlier. This means that if a data pair ( x , y ) exceeds, by two standard deviations, the mean of the Euclidean metric values between the sets X and Y , the pair is assumed to be an outlier.

To identify a good outlier, a bias computation was performed. In this procedure, Y represents the normalized data set for the number of deaths or the number of cases while X represents the normalized data set for every factor that were considered in this study. The bias is computed using the metric

for all x in X and y in Y . To categorize a city, province, or region as a good outlier, the bias corresponding to this locality must exceed two standard deviations from the mean of all the bias computations between the sets X and Y .

Results and discussion

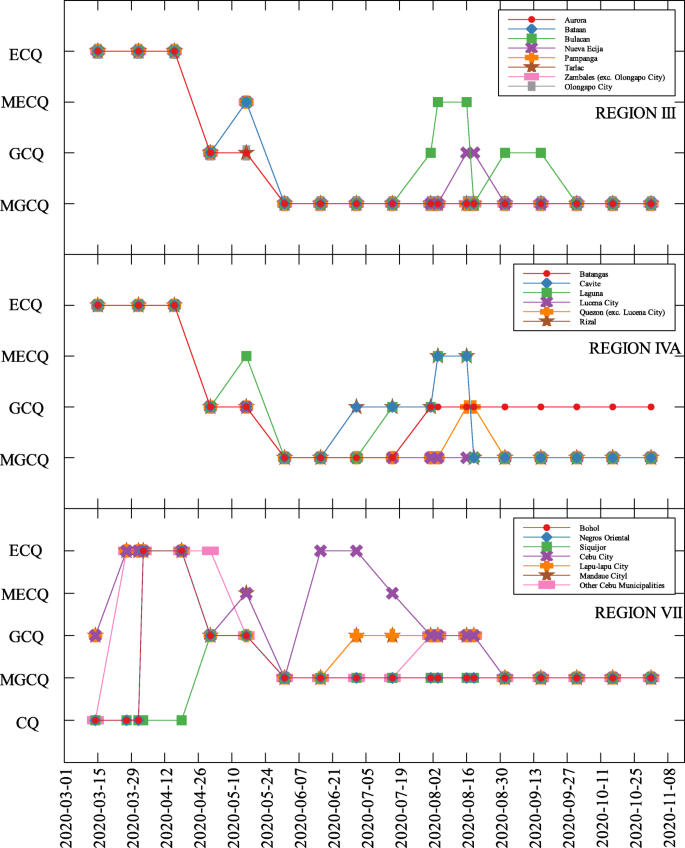

The data used were the reported COVID-19 cases and deaths in the Philippines as of November 10, 2020 which is 240 days since community lockdowns were implemented in the country. Figure 1 shows the different lockdowns implemented per province since March 15. It can be seen that ECQ was implemented in Luzon and major cities in the country in the first few weeks since March 15, and slowly eased into either GCQ or MGCQ as time progressed. By August, the most stringent lockdown was MECQ in the National Capital Region (NCR) and some nearby provinces. Places under MECQ on September were Iloilo City, Bacolod City, and Lanao del Sur, with the last province as the lone community to be placed under MECQ the month after. By November 1, 2020, communities were either placed under GCQ or MGCQ.

COVID-19 community quarantines in Regions III, IVA and VII

Comparison of economic, health, and demographic components and COVID-19 parameters

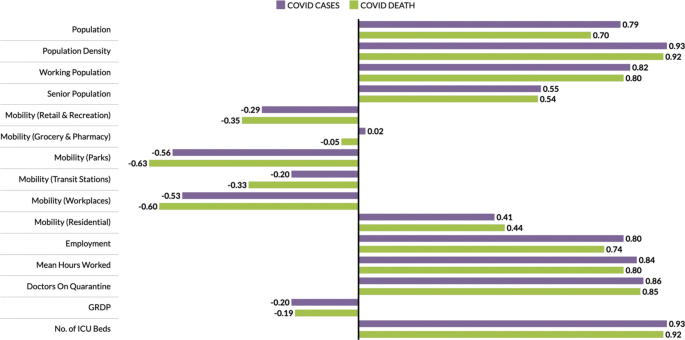

The economic, health and demographic components were compared to COVID-19 cases and deaths. These comparisons were done for different community levels (regional, provincial, city/metropolitan) (See Tables 2 , 3 , and 4 ). Figure 2 summarizes the correlation of components to COVID-19 cases and deaths at the regional level. In all components, correlations with other parameters to both COVID-19 cases and deaths are close. Every component except Residential Mobility and GRDP have slightly higher correlation coefficient for COVID-19 cases as compared to COVID-19 deaths.

Correlation of components to COVID-19 cases and deaths at the regional level

Among the components, the number of ICU beds component has the highest correlation with COVID-19 parameters. This makes sense as this is one of the first-degree measures of COVID-19 transmission. Population density comes in second, followed by mean hours worked and working population, which are all related to how developed the region is economy-wise. Regions having larger population density also have a huge working population and longer working hours [ 24 ]. Thus, having a huge population density implies high chance of having contact with each other [ 25 , 26 ]. Another component with high correlation to the cases and deaths is the number of doctors on quarantine, which can be looked at two ways; (i) huge infection rate in the region which is the reason the doctors got exposed or are on quarantine, and (ii) lots of doctors on quarantine which resulted to less frontliners taking care of the infected individuals. All definitions of mobility and the GDP are not strongly correlated to any of the COVID-19 measures.

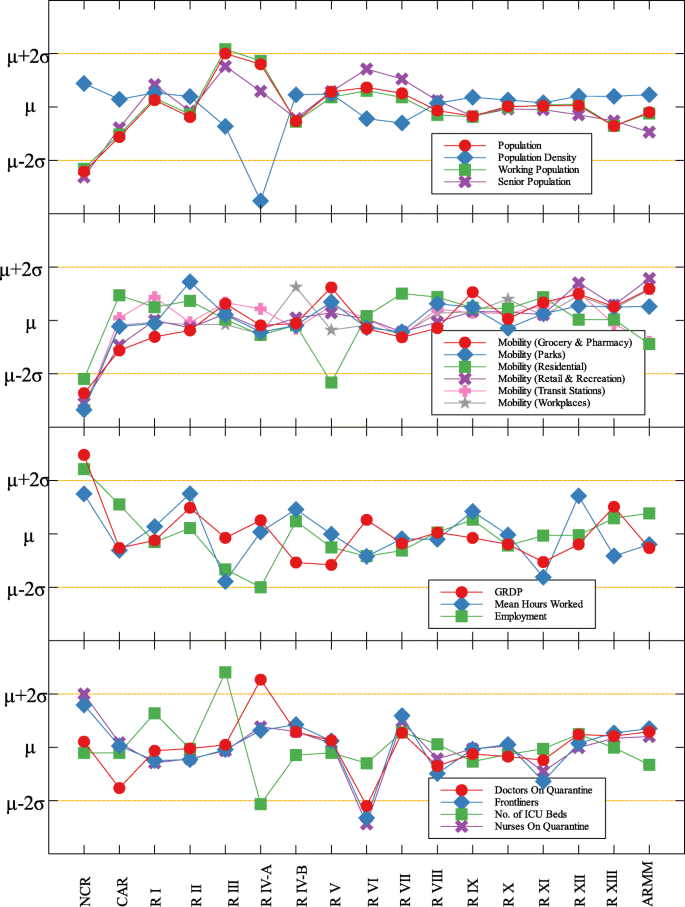

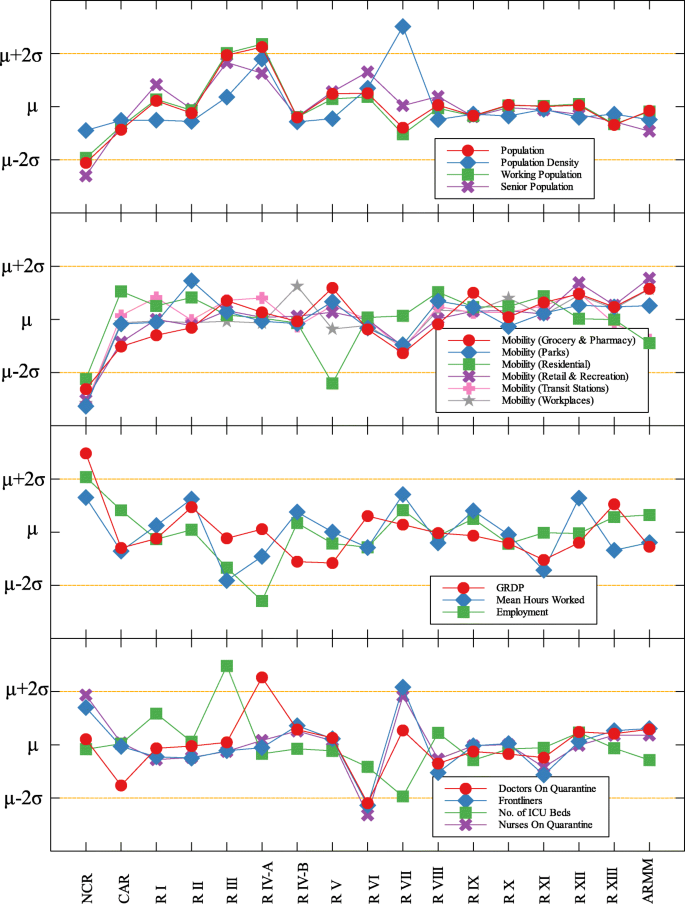

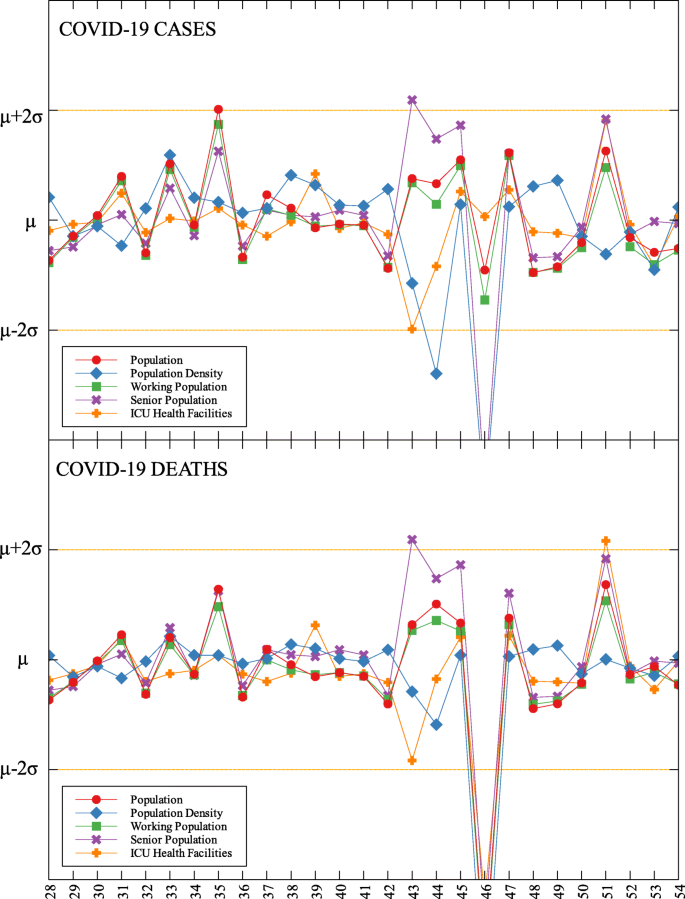

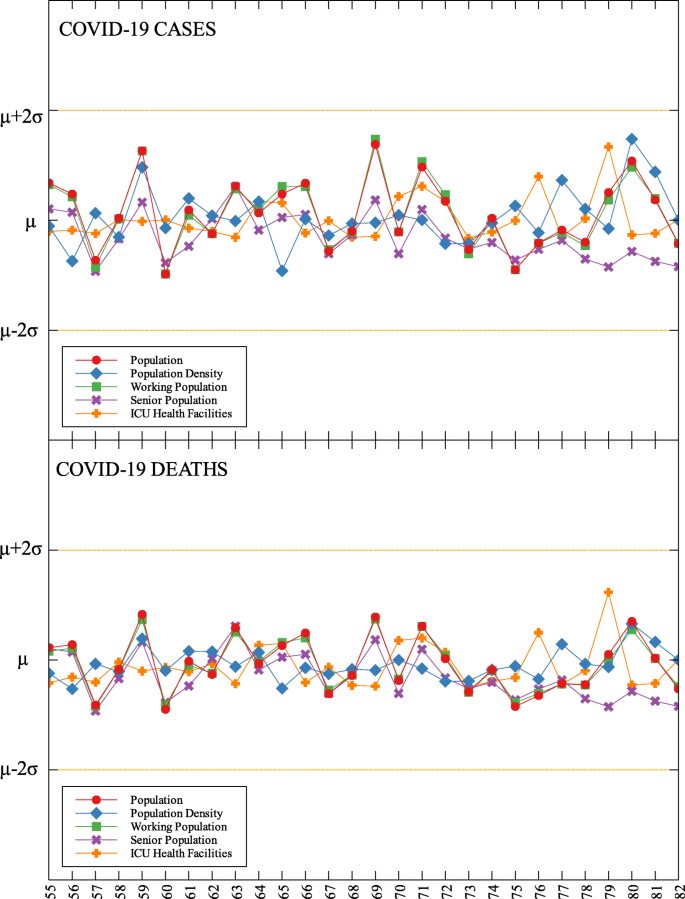

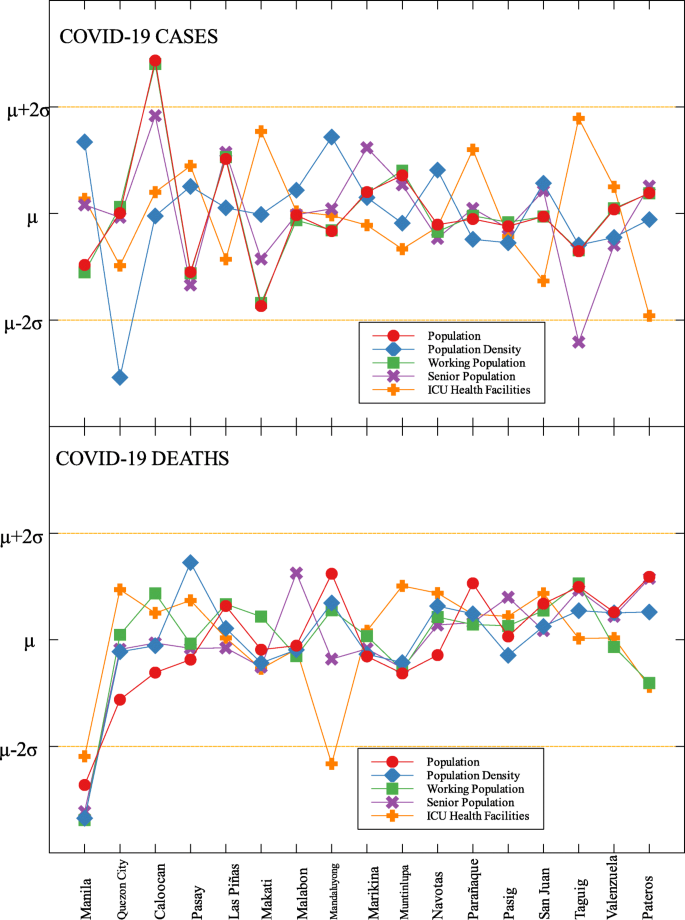

In each data set, outliers were identified depending on their distance from the mean. For simplicity, we denote components that are compared with COVID-19 cases by (C) and with COVID-19 deaths by (D). The summary of outliers among regions in the Philippines is shown in Figs. 3 and 4 . Data is classified according to groups of component. In each outlier region, non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) implemented and their timing are identified.

Outliers among regions in the Philippines with respect to COVID-19 cases

Outliers among regions in the Philippines with respect to COVID-19 deaths

Region III is an outlier in terms of working population (C) and the number of ICU beds (C) (see Fig. 5 and Table 5 ). This means that considering the working population of the region, the number of COVID-19 infections are better than that of other regions. Same goes with the number of ICU beds in relation to COVID-19 deaths. Region III is comprised of Aurora, Bataan, Nueva Ecija, Pampanga, Tarlac, Zambales, and Bulacan. This good performance might be attributed to their performance especially on their programs against COVID-19. As early as March 2020, the region had been under a community lockdown together with other regions in Luzon. Being the closest to NCR, Bulacan has been the most likely to have high number of COVID-19 cases in the region. But the province responded by opening infection control centers which offer free healthcare, meals, and rooms for moderate-severe COVID-19 patients [ 27 ]. They have also implemented strict monitoring of entry-exit borders, organization of provincial task force and incident command center, establishment of provincial quarantine facilities for returning overseas Filipino workers, mandated municipal quarantine facilities for asymptomatic cases, and mass testing, among others [ 27 ]. Most of which have been proven effective in reducing the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths [ 28 ].

Outliers among the provinces in Luzon with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

Outliers among the provinces in Visayas with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

Outliers among the provinces in Mindanao with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

Region IV-A is an outlier in terms of population and working population (D) and doctors on quarantine (D) (see Fig. 5 and Table 5 ). Considering their population and working population, the COVID-19 death statistics show better results compared to other regions. Same goes with the number of doctors in the region which are in quarantine in relation to the reported COVID-19 deaths. This shows that the region is doing well in terms of decreasing the COVID-19 fatalities compared to other regions in terms of populations and doctors on quarantine. Region IV-A is comprised of Batangas, Cavite, Laguna, Quezon, and Rizal. Same with Region III, they have been under the community lockdown since March of last year. Provinces of the region such as Rizal have been proactive in responding to the epidemic as they have already suspended classes and distributed face masks even before the nationwide lockdown [ 29 ]. Despite being hit by natural calamities, the region still continue ramping up the response to the pandemic through cash assistance, first aid kits, and spreading awareness [ 30 ].

An interesting result is that NCR, the center of the country and the most densely populated, is a good outlier in terms of GRDP (C) and GRDP (D). Cities in the region launched various programs in order to combat the disease. They have launched mass testings with Quezon City, Taguig City, and Caloocan City starting as early as April 2020. Pasig City started an on-the-go market called Jeepalengke. Navotas, Malabon, and Caloocan recorded the lowest attack rate of the virus. Caloocan city had good strategies for zoning, isolation and even in finding ways to be more effective and efficient. Other programs also include color-coded quarantine pass, and quarantine bands. It is also possible that NCR may just have a very high GRDP compared to other regions. A breakdown of the outliers within NCR can be seen in Fig. 8 .

Outliers in the national capital region with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

Region VII is also an outlier in terms of population density (D) and frontliners (D) (see Fig. 6 and Table 5 ). This means that given the population density and the number of frontliners in the region, their COVID-related deaths in the region is better than the rest of the country. This region consists of four provinces (Cebu, Bohol, Negros Oriental, and Siquijor) and three highly urbanized cities (Cebu City, Lapu-Lapu City, and Mandaue City), referred to as metropolitan Cebu. This significant decline may be explained by how the local government responded after they were placed in stricter community quarantine measures despite the rest of the country easing in to more lenient measures. Due to the longer and stricter quarantine in Cebu, the lockdown had a greater impact here than in other areas where restrictions were eased earlier [ 31 ]. Dumaguete was one of the destinations of the first COVID case in the Philippines [ 32 ], their local government was able to keep infections at bay early on. Siquijor was also COVID-19-free for 6 months [ 33 ]. The compounded efforts of the different provinces in the region can account for the region being identified as an outlier.

Among the metropolitan cities, Davao came out as a good outlier in terms of population (C) and working population (C) (see Figs. 7 , 9 , and Table 5 ). This result may be attributed to their early campaign on consistent communication of COVID-19-related concerns to the public [ 34 ]. They were also able to set up transportation for essential workers early on [ 35 ].

Outliers among metropolitan areas in the Philippines with respect to COVID-19 cases and deaths

This study identified outliers in each data group and determined the NPIs implemented in the locality. Economic, health and demographic components were used to identify these outliers. For the regional data, three regions in Luzon and one in Visayas were identified as outliers. Apart from the minimum IATF recommended NPIs, various NPIs were implemented by different regions in containing the spread of COVID-19 in their areas. Some of these NPIs were also implemented in other localities yet these other localities did not come out as outliers. This means that one practice cannot be the sole explanation in determining an outlier. The compounding effects of practices and their timing of implementation are seen to have influenced the results. A deeper analysis of daily data for different trends in the epidemic curve is considered for future research.

Correlation tables, outliers and community quarantine timeline

Availability of data and materials.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, Ren R, Leung KSM, Lau EHY, Wong JY, Xing X, Xiang N, Wu Y, Li C, Chen Q, Li D, Liu T, Zhao J, Liu M, Tu W, Chen C, Jin L, Yang R, Wang Q, Zhou S, Wang R, Liu H, Luo Y, Liu Y, Shao G, Li H, Tao Z, Yang Y, Deng Z, Liu B, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Shi G, Lam TTY, Wu JT, Gao GF, Phil D, Cowling BJ, Yang B, Leung GM, Feng Z. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(13):1199–207.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hsiang S, Allen D, Annan-Phan S, Bell K, Bolliger I, Chong T, Druckenmiller H, Huang LY, Hultgren A, Krasovich E, Lau P, Lee J, Rolf E, Tseng J, Wu T. The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the covid-19 pandemic. Nature. 2020; 584:262–67.

Anderson R, Heesterbeek JAP, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth T. Comment how will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the covid-19 epidemic?Lancet. 2020; 395. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5 .

Buhat CA, Torres M, Olave Y, Gavina MK, Felix E, Gamilla G, Verano KV, Babierra A, Rabajante J. A mathematical model of covid-19 transmission between frontliners and the general public. Netw Model Anal Health Inform Bioinforma. 2021; 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13721-021-00295-6 .

Ocampo L, Yamagishic K. Modeling the lockdown relaxation protocols of the philippine government in response to the covid-19 pandemic: an intuitionistic fuzzy dematel analysis. Socioecon Plann Sci. 2020; 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2020.100911 .

Weible C, Nohrstedt D, Cairney P, Carter D, Crow D, Durnová A, Heikkila T, Ingold K, McConnell A, Stone D. Covid-19 and the policy sciences: initial reactions and perspectives. Policy Sci. 2020; 53:225–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-020-09381-4 .

Article Google Scholar

Wibbens PD, Koo WW-Y, McGahan AM. Which covid policies are most effective? a bayesian analysis of covid-19 by jurisdiction. PLoS ONE. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244177 .

Mintrom M, O’Connor R. The importance of policy narrative: effective government responses to covid-19. Policy Des Pract. 2020; 3(3):205–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1813358 .

Google Scholar

Chin T, Kahn R, Li R, Chen JT, Krieger N, Buckee CO, Balsari S, Kiang MV. Us-county level variation in intersecting individual, household and community characteristics relevant to covid-19 and planning an equitable response: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open. 2020; 10(9). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039886 .

OECD. The territorial impact of COVID-19: managing the crisis across levels of government. 2020. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-territorial-impact-of-covid-19-managing-the-crisis-across-levels-of-government-d3e314e1/#biblio-d1e5202 . Accessed 20 Feb 2007.

White ER, Hébert-Dufresne L. State-level variation of initial covid-19 dynamics in the united states. PLoS ONE. 2020; 15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240648 .

Lin S, Huang J, He Z, Zhan D. Which measures are effective in containing covid-19? — empirical research based on prevention and control cases in China. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.28.20046110 . https://www.medrxiv.org/content/early/2020/03/30/2020.03.28.20046110.full.pdf .

Mei C. Policy style, consistency and the effectiveness of the policy mix in China’s fight against covid-19. Policy Soc. 2020; 39(3):309–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1787627. http://arxiv.org/abs/https: //doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1787627.

Dutta A, Fischer HW. The local governance of covid-19: disease prevention and social security in rural india. World Dev. 2021; 138:105234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105234 .

Vallejo BM, Ong RAC. Policy responses and government science advice for the covid 19 pandemic in the philippines: january to april 2020. Prog Disaster Sci. 2020; 7:100115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100115 .

Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases. Omnibus guidelines on the implementation of community quarantine in the Philippines. 2020. https://doh.gov.ph/node/27640 . Accessed 20 Feb 2020.

Roy S, Ghosh P. Factors affecting covid-19 infected and death rates inform lockdown-related policymaking. PloS ONE. 2020; 15(10):0241165. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241165 .

Pullano G, Valdano E, Scarpa N, Rubrichi S, Colizza V. Evaluating the effect of demographic factors, socioeconomic factors, and risk aversion on mobility during the covid-19 epidemic in france under lockdown: a population-based study. Lancet Digit Health. 2020; 2(12):638–49.

Department of Health. COVID-19 tracker. 2020. https://doh.gov.ph/covid19tracker . Accessed 25 Nov 2020.

Authority PS. Philippine population density (based on the 2015 census of population). 2020. https://psa.gov.ph/content/philippine-population-density-based-2015-census-population . Accessed 11 Apr 2020.

Google. COVID-19 community mobility report. 2020; https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility?hl=en. Accessed 25 Nov 2020.

Authority PS. Labor force survey. 2020. https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/survey/labor-and-employment/labor-force-survey?fbclid=IwAR0a5GS7XtRgRmBwAcGl9wGwNhptqnSBm-SNVr69cm8sCVd9wVmcoKHRCdU . Accessed 11 Apr 2020.

Authority PS. https://psa.gov.ph/grdp/tables?fbclid=IwAR3dKvo3B5eauY7KcWQG4VXbuiCrzFHO4b-f1k5Od76ccAlYxUimUIaqs94 . Accessed 11 Apr 2020. 2020.

Peterson E. The role of population in economic growth. SAGE Open. 2017; 7:215824401773609. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017736094 .

Buhat CA, Duero JC, Felix E, Rabajante J, Mamplata J. Optimal allocation of covid-19 test kits among accredited testing centers in the philippines. J Healthc Inform Res. 2021; 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41666-020-00081-5 .

Hamidi S, Sabouri S, Ewing R. Does density aggravate the covid-19 pandemic?: early findings and lessons for planners. J Am Plan Assoc. 2020; 86:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1777891 .

Philippine News Agency. Bulacan shares anti-COVID-19 best practices. 2020. https://mb.com.ph/2020/08/16/bulacan-shares-anti-covid-19-best-practices/ . Accessed Mar 2020.

Buhat CA, Villanueva SK. Determining the effectiveness of practicing non-pharmaceutical interventions in improving virus control in a pandemic using agent-based modelling. Math Appl Sci Eng. 2020; 1:423–38. https://doi.org/10.5206/mase/10876 .

Hallare K. Cainta, Rizal suspends classes, distributes face masks over coronavirus threat. 2020. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1238217/cainta-rizal-suspends-classes-distributes-face-masks-over-coronavirus-threat . Accessed Mar 2020.

Relief International. Responding to COVID-19 in the Aftermath of Volcanic Eruption. 2020. https://www.ri.org/projects/responding-to-covid-19-in-the-aftermath-of-volcanic-eruption/. Accessed Mar 2020.

Macasero R. Averting disaster: how Cebu City flattened its curve. 2020. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/explainers/how-cebu-city-flattened-covid-19-curve/ . Accessed Mar 2020.

Edrada EM, Lopez EB, Villarama JB, Salva-Villarama EP, Dagoc BF, Smith C, Sayo AR, Verona JA, Trifalgar-Arches J, Lazaro J, Balinas EGM, Telan EFO, Roy L, Galon M, Florida CHN, Ukawa T, Villaneuva AMG, Saito N, Nepomuceno JR, Ariyoshi K, Carlos C, Nicolasor AD, Solante RM. First covid-19 infections in the philippines: a case report. Trop Med Health. 2020; 48(30). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-020-00218-7 .

Macasero R. Coronavirus-free for 6 months, Siquijor reports first 2 cases. 2020. https://www.rappler.com/nation/siquijor-coronavirus-cases-august-2-2020 . Accessed Mar 2020.

Davao City. Mayor Sara, disaster radio journeying with dabawenyos. 2020. https://www.davaocity.gov.ph/disaster-risk-reduction-mitigation/mayor-sara-disaster-radio-journeying-with-dabawenyos . Accessed Mar 2020.

Davao City. Davao city free rides to serve GCQ-allowed workers. 2020. https://www.davaocity.gov.ph/transportation-planning-traffic-management/davao-city-free-rides-to-serve-gcq-allowed-workers/ . Accessed Mar 2020.

Download references

Acknowledgements

JFR is supported by the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics Associateship Scheme.

This research is funded by the UP System through the UP Resilience Institute.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Mathematical Sciences and Physics, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines

Dylan Antonio S. Talabis, Ariel L. Babierra, Christian Alvin H. Buhat, Destiny S. Lutero, Kemuel M. Quindala III & Jomar F. Rabajante

University of the Philippines Resilience Institute, University of the Philippines, Quezon City, Philippines

Faculty of Education, University of the Philippines Open University, Laguna, Philippines

Jomar F. Rabajante

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors are involved in drafting the manuscript and in revising it. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dylan Antonio S. Talabis .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable. We used secondary data. These are from the public database of the Philippine Department of Health ( https://www.doh.gov.ph/covid19tracker ) and Philippine Statistics Authority Census ( https://psa.gov.ph )

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

S. Talabis, D.A., Babierra, A.L., H. Buhat, C.A. et al. Local government responses for COVID-19 management in the Philippines. BMC Public Health 21 , 1711 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11746-0

Download citation

Received : 19 April 2021

Accepted : 30 August 2021

Published : 21 September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11746-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Local government

- Quantitative methods

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

RTI uses cookies to offer you the best experience online. By clicking “accept” on this website, you opt in and you agree to the use of cookies. If you would like to know more about how RTI uses cookies and how to manage them please view our Privacy Policy here . You can “opt out” or change your mind by visiting: http://optout.aboutads.info/ . Click “accept” to agree.

Fighting COVID-19 in the Philippines

8 ways usaid reachhealth supports pandemic response.

As COVID-19 swept the world in 2020, the Philippines became Southeast Asia’s most affected country.

RTI International has been supporting the COVID-19 response in the Philippines through ReachHealth , a five-year United States Agency for International Development (USAID) project that strengthens and improves access to family planning and maternal and child health services.

Building on 14 years of RTI experience working with local governments in the Philippines to improve health outcomes, the USAID ReachHealth Project supports the COVID-19 response in 15 priority local government units across the country. Working closely with the Department of Health (DOH), the Department of Interior and Local Governance, UN agencies, the private sector, and civil society organizations, we strengthen the government’s emergency and ongoing response at all levels.

Our support has included operationalizing nationwide COVID-19 policies, rolling out vaccines, helping facilities access national COVID-19 financing and testing kits, strengthening the capacities of health workers on infection prevention and control and case management, improving contact tracing, and supporting risk communication and community engagement efforts. Most recently, ReachHealth has helped the country prepare for the roll out of child vaccines and the safe reopening of in-person schools.

Since ReachHealth began supporting the Philippines' pandemic response, we have trained over 20,000 people and reached nearly 37 million people with messages on preventing gender-based violence and COVID-19’s spread.

Here are eight of the important ways we have and continue to respond to COVID-19 in the Philippines:

1. Strengthening community health and support systems

Barangay Health Emergency Response Teams, or BHERTs, usually connect community members to health facilities — but during times of emergency their work becomes more important than ever. These neighborhood-based teams formed the frontline of efforts to delay COVID-19’s spread and locally contain the pandemic by communicating risk, facilitating contact tracing and vaccination, and connecting communities with broader local health systems. ReachHealth works to ensure BHERTs in hotspot communities are active, effective, and trained on critical elements of the COVID-19 community response, including essential behaviors to prevent the virus’ spread, infection prevention and control, vaccination and testing protocols, contact tracing, and quarantine and isolation. ReachHealth has helped train over 7,800 people on contact tracing and rapid response so far.

2. Increasing vaccine coverage

In 2021, ReachHealth collaborated with the DOH and local actors to plan for vaccine rollouts. We developed public messaging for local governments to spread the word, updated FAQs for community health responders like BHERTs, and supported health facility planning and preparation. Once vaccines were available, ReachHealth also helped speed up the roll out by deploying 28 mobile vaccine teams across the country to ensure even the most remote communities got access. ReachHealth has established or supported over 200 vaccination sites in the Philippines. More than 2.8 million Filipinos have been fully vaccinated with ReachHealth’s support.

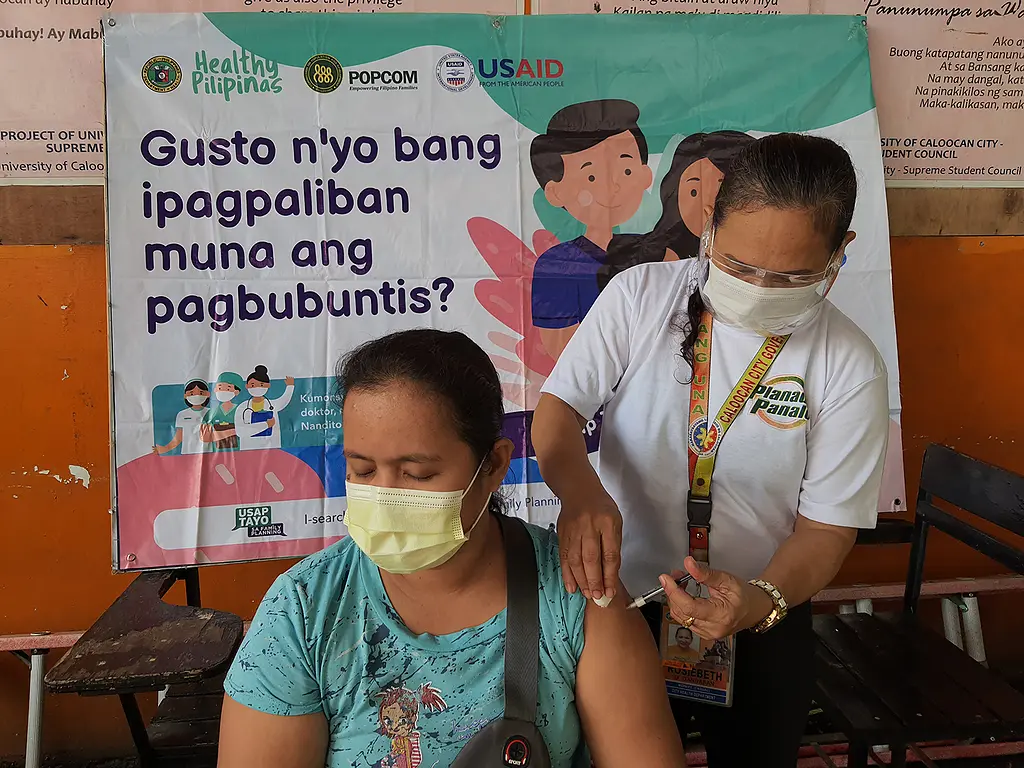

Grace Jose receives a COVID vaccine at a vaccination site in Caloocan City. Photo by Christian Rieza/USAID ReachHealth

3. Strengthening health and testing facilities

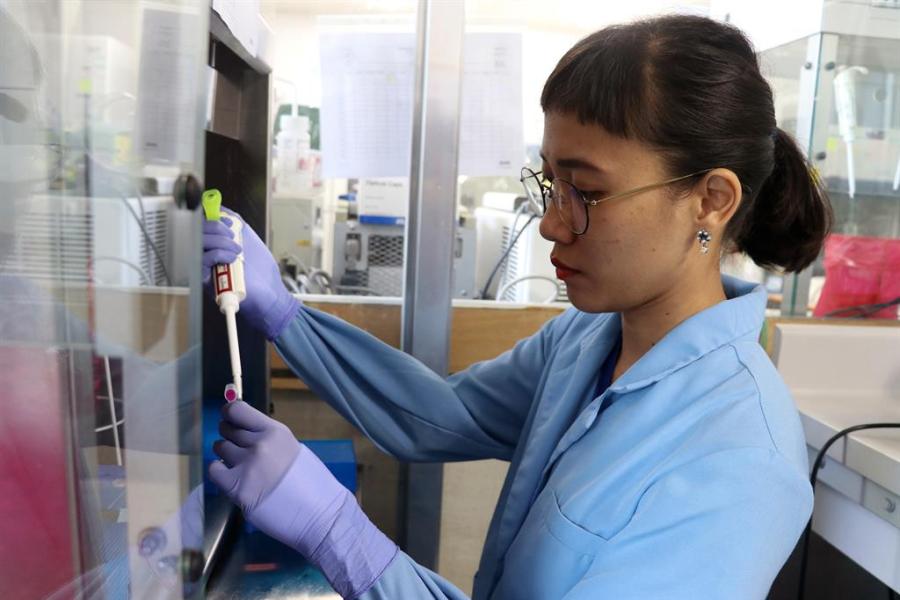

Throughout the pandemic, the science on COVID-19 and how to address it has evolved. To help health facilities keep up, ReachHealth provided training to over 5,000 people on case management and over 3,000 people on infection prevention and control. We also partnered with local governments to establish 10 additional mobile testing units and four community testing centers in vulnerable areas. As COVID-19 testing increased, so did the demand for accredited labs that could process tests quickly. By providing support , ReachHealth helped increase the number of accredited labs across the country and reduced testing times to just a few hours in eight labs in Mindanao and Luzon.

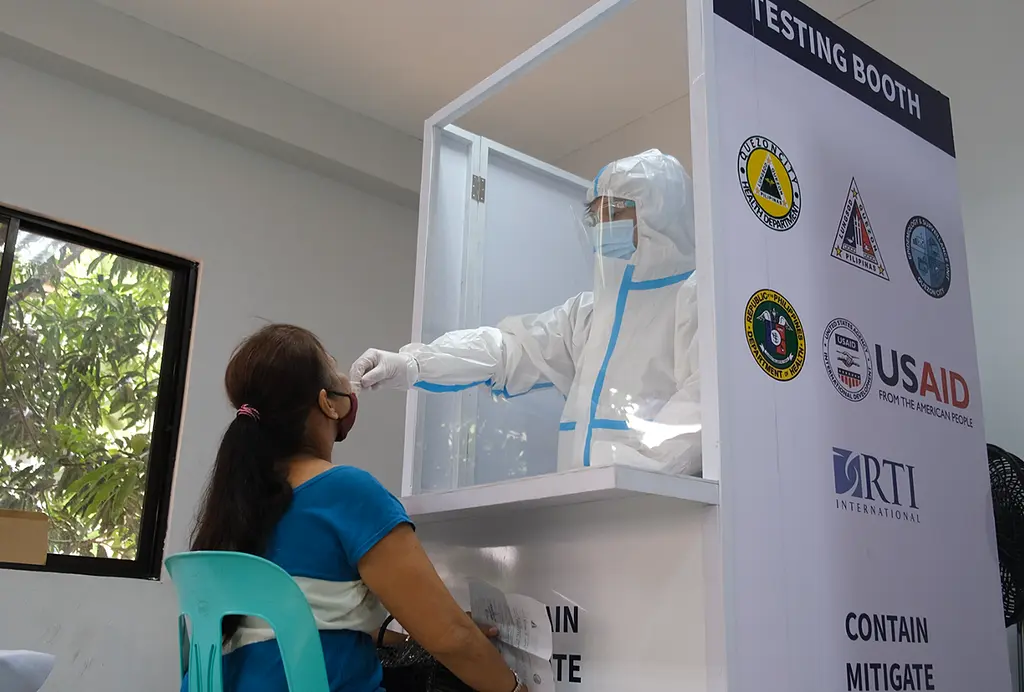

Vilma Cabral gets tested for COVID-19 at a USAID-supported community-based testing center in the Philippines. Photo by Rosana Ombao for USAID

4. Supporting a data-driven response

The DOH collaborated with the World Health Organization to launch a mobile application, COVID KAYA , that supports frontline responders with contact tracing and case monitoring. The introduction of any new, centralized data system across regions with varying needs and infrastructure can be challenging and uneven. Our team provided technical assistance to help local governments roll out the application, and directly trained officials, health workers, and personnel from health epidemiology units on its use.

5. Addressing gender-based violence

In the Philippines, 1 in 20 women and girls aged 15-49 have experienced sexual violence. COVID-19 lockdowns and quarantines brought extended periods of restricted movement and home confinement for millions of people — an unprecedented situation that worsened violence against women and children at home. ReachHealth supported the continued functioning of gender-based violence (GBV) services, such as a 24-hour helpline, while a messaging campaign, Hindi kailangang magtiis! (You don’t need to suffer in silence!), sought to prevent GBV and to let people know about available services. Since October 2020, this campaign has reached over 9 million Filipinos on Facebook alone.

6. Distributing essential equipment and supplies

Frontline health workers needed personal protective equipment (PPE) to care for their patients safely. In partnership with the Armed Forces of the Philippines, ReachHealth supported the distribution of PPE donated by the US Defense Threat Reduction Agency to 109 hospitals, rural health units, and quarantine facilities in vulnerable areas across the country. We also partnered with Proctor & Gamble to distribute more than 700,000 face masks. ReachHealth is now providing PPE and communication materials to local schools to aid in the safe reopening of in-person classes.

Boxes of personal protective equipment destined for health facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic in Cebu City, Philippines. Photo by Robyn Lacson/USAID ReachHealth

7. Prioritizing water, sanitation, and hygiene

Although water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) was not a focus area for ReachHealth, our team recognized that good sanitation and hygiene are critical to slowing the spread of COVID-19. We developed a tool to assess and prioritize sites for handwashing stations and installed these facilities in more than 200 quarantine centers, shelters, and public spaces. We also incorporated WASH messaging into our trainings and messaging campaigns and partnered with the DOH and Procter & Gamble to procure and distribute 70,000 hygiene kits to adults and young people. We have reached over 2.5 million Filipinos with WASH support so far, and our team continues to collaborate with local WASH organizations to bolster their ongoing work.

U.S. Ambassador Sung Kim uses one of the 16 handwashing stations installed in facilities and communities around the city. Photo by Rosana Ombao/USAID ReachHealth

8. Keeping our focus on family planning

Family planning (FP) continues to be an essential health service, especially in times of social and economic uncertainty. While our team stepped up to contribute their expertise to the COVID-19 response, they remain committed to expanding access to quality FP services across the Philippines. In March 2020, 25% of surveyed health centers reported a disruption in FP services and 81% saw a decline in people seeking FP care. From creating online resources to helping service providers improve their teleconsultation abilities, our team rapidly adapted approaches to accommodate the new normal and ensure all Filipinos could continue to access FP care. More than 2,000 teleconsultations on family planning have occurred since.

A team of "Nurses on Wheels" delivers family planning supplies to neighborhood health stations in Cainta. Photo by Mon Joshua Vergara/Cainta Municipal Health Office

- U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)

- Global Health

- Global Health Security

- COVID-19 Research + Response

- Health Systems Strengthening

- Primary Health Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- Interventions and Prevention Programs

ReachHealth: Strengthening Access to Critical Services for Filipino Families

Assessing the availability of essential family planning services during covid-19 in the philippines, from hotspots to bright spots: fighting covid-19 in the barangays of the philippines, hope on wheels: delivering vaccines to remote communities, stopping the spread: making covid testing accessible for filipinos.

- Emergencies /

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the Philippines /

- Information for the public /

Recognize and respond to COVID-19

Last updated: 08 September 2020

Do you have symptoms of coronavirus? Not sure what to do? Always follow your national health authority’s advice.

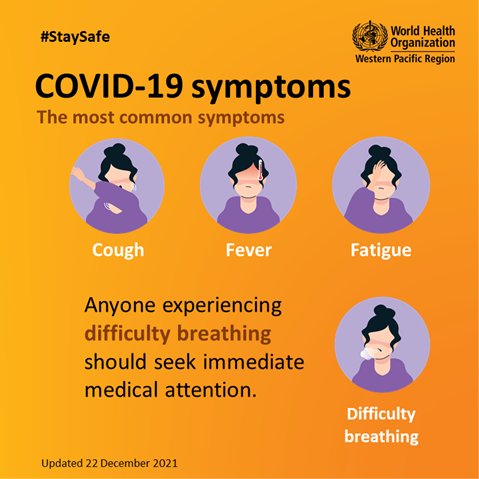

Symptoms of COVID-19 can vary, but mild cases often experience fever, cough, and fatigue. Moderate cases may have difficulty breathing or mild pneumonia. While severe cases may have severe pneumonia, other organ failure & possible death.

Anyone experiencing difficulty breathing should seek immediate medical attention.

Infographics

How can you recognize the symptoms of COVID-19?

Symptoms vary, but mild cases often experience fever, cough, and fatigue. Moderate cases may have difficulty breathing or mild pneumonia. While severe cases have severe pneumonia, other organ failure & possible death.

Follow advice from your national health authority on what to do if you have COVID-19 symptoms.

In some situations, people who are at low risk may be asked to stay home, self-isolate and rest.

More from the Western Pacific

More from WHO Global

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Journalism, public health, and COVID-19: some preliminary insights from the Philippines

In this essay, we engage with the call for Extraordinary Issue: Coronavirus, Crisis and Communication. Situated in the Philippines, we reflect on how COVID-19 has made visible the often-overlooked relationship between journalism and public health. In covering the pandemic, journalists struggle with the shrinking space for press freedom and limited access to information as they also grapple with threats to their physical and mental well-being. Digital media enable journalists to report even in quarantine, but new challenges such as the wide circulation of health mis-/disinformation and private information emerge. Moreover, journalists have to contend with broader structural contexts of shutdown not just of a mainstream broadcast but also of community newspapers serving as critical sources of pandemic-related information. Overall, we hope this essay broadens the dialogue among journalists, policymakers, and healthcare professionals to improve the delivery of public health services and advance health reporting.

Introduction

In this essay, we reflect on how COVID-19 has brought to our attention the often-overlooked relationship between journalism and public health. We draw initial insights from critical analysis of media and public health ( Henderson and Hilton, 2018 ) to suggest that health reporting in the country during the pandemic can be connected to journalistic practices, technological changes, and structural constraints. For journalism to advance public health, it needs to contend with the pandemic and the context into which it is uniquely situated – both of which are moving targets and difficult to predict. In this essay, we pay attention to the Philippines not just because it has one of the highest COVID 19-related cases and deaths in the world but also because the country is at the crossroads of changes in digital media and shrinking space for media freedom, as evidenced by the shutdown of the country’s biggest media network, closing or suspension of community newspapers, and passage of laws that may restrict free speech. In doing so, we hope to broaden dialogue among journalists, policymakers, and healthcare professionals to improve the delivery of public health services as well as advance health reporting.

Similar to other countries, the public health system in the Philippines was unprepared for and overburdened by COVID-19. The first case was reported on January 30 when a Chinese woman reached the country from Wuhan, China, and then a few days later her male companion died of the virus – making it the first recorded death outside of China ( Department of Health (DOH), 2020b ; Ramzy and May, 2020 ; World Health Organization (WHO), 2020a ). By March 7, the first case of local transmission was confirmed ( DOH, 2020a ; WHO, 2020a ). To date, there are 112,593 confirmed cases, 6,263 new cases, and 2,115 deaths in the country ( WHO, 2020b ) – making the Philippines as one of the most highly impacted in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific Region. Equally alarming is the number of doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff who get infected and die of COVID-19 ( CNN Philippines, 2020a ; McCarthy, 2020 ). Recently, professional medical and allied medical associations have called for a unified and calibrated response and temporary quarantine of the country’s capital to avoid a total collapse of the healthcare system ( Batnag, 2020 ). Critical but seldom discussed are the challenges of journalism in making sense of the rapid spread and devastating impact of COVID-19 in the Philippines and how the pandemic is also gradually transforming journalism in the country.

Journalism and public health work together to broaden health information sources, facilitate public understanding of health, and mobilize support for or against public health policy ( Henderson and Hilton, 2018 ; Larsson et al., 2003 ; Vercellesi et al., 2010 ) and this relationship is magnified during pandemics. The relationship between journalism and public health has mostly been explained based on journalistic roles and news framing. During the 2009 H1N1, for instance, Klemm et al. (2017) found that journalists shifted from ‘watchdogs’ to ‘cooperative’ roles. Holland et al. (2014) further argued that the 2009 H1N1 enabled journalists to be reflexive of their roles especially with conflicts of interest among experts and decision makers. News framing has likewise informed the conversations between journalism and public health. For example, Krishnatray and Gadekar (2014) found that fear and panic dominated the frames used by journalists in their news stories about the 2009 H1N1. In this essay, we hope to engage with ongoing discussion about journalism and public health by reflecting on how health reporting during COVID-19 in the Philippines relates to broader, emergent, and interconnected issues of journalistic practices, technological changes, and structural constraints in the country.

Reporting from home

COVID-19, along with the ensuing quarantines, poses challenges to existing journalistic practices that typically require fieldwork, but it also encourages journalists in the Philippines to reimagine news production. We observe that access to information has generally been limited because government offices have not been in full operation while virtual press briefings do not allow for a more open discussion between journalists and officials. To illustrate, Ilagan (2020) reported that most routine requests for information have not been processed since March 2020 when government offices were wholly or partly closed due to the ongoing quarantine. The Philippines is among many governments in the world that had to suspend the processing of freedom-of-information (FOI) requests because of the pandemic ( McIntosh, 2020 ). FOI officers working from home could not address requests because they lacked Internet connection, laptop computers, and scanners, including digital copies of files. They also found it difficult to coordinate remotely with record custodians. While some national agencies have been proactive in providing information on COVID-19, the same cannot be said for many local government units. Ilagan (2020) further noted that ‘[un]like frontline agencies at the national level, local governments do not proactively publish data on their websites’. Information about plans to combat the impact of the virus are usually available, but more prodding is needed to find out how these plans are being implemented and funded. Camus (2020) also reported that journalists were prohibited from covering what is happening in hospitals and other high-risk areas. More and more press briefings have thus taken place online, but reporters have found it harder to demand answers because officials and their staff often screen questions. For instance, Camus (2020) wrote that some questions from journalists were ignored while official reports from the government were consistently discussed.