- Skip to header navigation

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- Member login

International Federation of Social Workers

Global Online conference

Global Standards for Social Work Education and Training

August 1, 2020

Latvian Translation Spanish Translation

PREAMBLE RATIONALE THE SCHOOL 1. Core Mission, Aims and Objectives 2. Resources and Facilities 3. Curriculum 4. Core Curricula Social Work in Context Social Work in Practice Practice Education (Placement) 5. Research and Scholarly activity THE PEOPLE 1. Educators 2. Students 3. Service Users THE PROFESSION 1. A shared understanding of the Profession 2. Ethics and Values 3. Equity and Diversity 4. Human rights and Social, Economic and Environmental Justice MEMBERS OF THE JOINT TASKFORCE

back to top The International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW) and the International Association of Schools of Social Work (IASSW) have jointly updated the Global Standards for Social Work Education and Training. The previous version of the Global Standards for Social Work Education and Training document was adopted by the two organisations in Adelaide, Australia in 2004. Between 2004 and 2019, that document served as an aspirational guide setting out the standards for excellence in social work education.

With the adoption of a new Global Definition of Social Work in July 2014, and the publication of the updated Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles in 2019, the Global Standards for Social Work Education and Training document should be updated to integrate the changes in these two documents and to reflect recent developments in global social work.

To this effect, the two organisations created a joint task group comprising the IFSW Interim Global Education Commission and IASSW’s Global Standards Taskforce. This task group engaged with the global social work community through a rigorous consultation that lasted for over 18 months and included feedback from 125 countries represented by 5 Regional Associations and approximately 400 Universities and Further Education Organisations. In addition, members of the joint task force facilitated two international seminars involving service user representatives.

Therefore, we are confident that the present document has been the product of a dynamic and collective process. It has also been the culmination of a rigorous exploration of epistemological, political, ethical and cultural dilemmas.

The main objectives of the Global Standards are to:

- Ensure consistency in the provision of social work education while appreciating and valuing diversity, equity and inclusion.

- Ensure that Social Work education adheres to the values and policies of the profession as articulated by the IFSW and IASSW.

- Support and safeguard staff, students and service users involved in the education process.

- Ensure that the next generation of social workers have access to excellent quality learning, opportunities that also incorporate social work knowledge deriving from research, experience, policy and practice.

- Nurture a spirit of collaboration and knowledge transfer between different social work schools and between social work education, practice and research.

- Support social work schools to become thriving, well-resourced, inclusive and participatory teaching and learning environments.

While appreciating the overarching objectives, we are also mindful of the fact that the educational experience and policy framework in different countries varies significantly. The Global Standards aim at capturing both the universality of social work values and the diversity that characterises the profession through the articulation of a set of standards that are divided between compulsory (those that all programmes must adhere to) and aspirational (those standards that Schools should aspire to include when and where possible). The former represents foundational elements, which are intended in part to promote consistency in social work education across the globe.

Professor Vasilios Ioakimidis Professor Dixon Sookraj

back to top We took the following realities of social work across the globe into account in developing the standards:

- Diversity of historic, socio-cultural, economic and political contexts in which social work is practiced, both within countries and across the globe.

- Diversity of practices according to: 1) practice setting (e.g. government, NGO, health, education, child and family services agencies, correctional institutions, other community-based organizations and private practice settings); 2) field or area of practice (e.g. population served, type of personal and social, economic, political and environmental issues addressed); and 3) practice theories, methods, techniques and skills representing practice at different levels – individual, couple/family, group, organization, community, broader societal and international (i.e., micro, mezzo and macro levels).

- Diversity of structures and delivery methods of social work education. Social work education varies in terms of its position within the structures of education institutions (e.g., units, departments, schools, and faculties). Some social work education programs are aligned with other disciplines, such as economics and sociology, and some are part of broader professional groupings such as health or development. In addition, the level, attitudes toward, and integration of distance education and online learning vary a great deal among programs.

- Diversity of resources available to support social work education, including social work educators and directors across the globe.

- Diversity in levels of development of the social work profession across the globe. In many countries, it is a well-established profession backed by legislation and accompanying regulatory bodies and codes of ethics. A recognized baccalaureate social work degree is often the minimum educational requirement for professional practice. These mechanisms serve in part to protect the use of the title of ‘social worker’, define the scope of practice (what social workers can or cannot do in practice), ensure that practitioners maintain competence and protect the public from harm by social workers. In other countries social work takes different forms. Social work educational programs may be added to existing curriculum offerings rather than standing as separate academic units. They may range from individual course offerings, to one-year certificate programs, to two-year diploma programs. The curriculum standards presented in this document apply primarily to social work degree programs. Shorter certificate and degree programs may use the standards, but they may not be able to incorporate all the standards.

- The adverse effects of colonization and educational imperialism on the development of social work in the Global South. We believe and stand firm that the theoretical perspectives and practice methods, techniques and skills developed in the Global North should not be transported to the Global South without critical examinations of their suitability and potential effectiveness for the local contexts.

- The growing number of common issues and challenges affecting social work education and practice across the globe. These include growing inequalities produced by neoliberal globalization, climate change, human and natural disasters, economic and political corruption and conflicts.

- Many new developments and innovations, especially those relating to sustainable development, climate change and UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, are occurring in the Global South. Thus, connecting the global and the local within the curriculum would strengthen the academic preparation of social workers everywhere; it will facilitate assessments for transferability of social work education across jurisdictions, including international borders; it will also help strengthen students’ professional identities as members of a global profession.

- Finally, curriculum specializations’ contribution to fragmentation in education and practice. Regardless of the area of specialization delivered in the curriculum, the program should prepare students to understand the interconnectedness of practice at all levels – individual, family, group, organization, community, etc. (i.e., micro, mezzo, macro). This broader understanding will help students to become critical, ethical and competent practitioners.

This version of the Global Standards is organised around three overarching domains that capture the distinct, yet intertwined, elements of Social Work education: The School, The People and The Profession

back to top Social Work education has historically been delivered by a wide and diverse range of organisations, including Universities, Colleges, Tertiary, Further and Higher Education bodies- public, private and non-profit. Notwithstanding the diversity of education delivery modalities, organisational and financial structures, there is an expectation that social work schools and programmes are formally recognised by the appropriate education authorities and/or regulators in each country. Social Work education is a complex and demanding activity that requires access to adequate resources, educators, transparent strategies and up- to-date curricula.

1. Core Mission, Aims and Objectives

back to top All Social Work Programmes must develop and share a core purpose statement or a mission statement that:

- Is clearly articulated, accessible and reflects the values and the ethical principles of social work.

- Is consistent with the global definition and purpose of social work

- Respects the rights and interests of the people involved in all aspects of delivery of programmes and services (including the students, educators and service users).

Where possible, schools should aspire to:

- Articulate the broad strategies for contribution to the advancement of the Social Work profession and the empowerment of communities within which a school strives to operate (locally, nationally and internationally).

In respect of programme objectives and expected outcomes, schools must be able to demonstrate how it has met the following requirements:

- Specification of its programme objectives and expected higher education outcomes.

- Identification of its programme’s instructional methods that support the achievement of the cognitive and affective development of social work students.

- A curriculum that reflects the core knowledge, processes, values and skills of the social work profession, as applied in context-specific realities.

- Social Work students who attain an initial level of proficiency with regard to self-reflective use of social work values, knowledge and skills.

- Curriculum design that takes into account of the impact of interacting cultural, political, economic, communication, health, psychosocial and environmental global factors.

- The programme meets the requirements of nationally and/or regionally/internationally defined professional goals

- The programme addresses local, national and/or regional/international developmental needs and priorities.

- The provision of an education preparation that is relevant to beginning social work practice interventions with individuals, families, groups and/or communities (functional and geographic) adaptable to a wide range of contexts.

- The use of social work methods that are based on sound evidence regarding the effectiveness of interventions whenever possible, and always promote dignity and respect.

- Governance, administrative supports, physical structure and related resources that are adequate to deliver the program.

- The conferring of a distinctive social work qualification at the certificate, diploma, first degree or post-graduate level, as approved by national and/or regional qualification authorities, where such authorities exist.

In order to further enrich their mission and objectives, schools should aspire to:

- External peer evaluation of the programme as far as is reasonable and financially viable. This may include external peer moderation of assignments and/or written examinations and dissertations, and external peer review and assessment of curricula.

- Self-evaluation by the education programme constituents to assess the extent to which its programme objectives and expected outcomes are being achieved.

2. Resources and Facilities

back to top With regard to structure, administration, governance and resources, the school and/or body designated as the education provider must ensure the following:

- Social work programmes are independent of other disciplines and should therefore be implemented through a distinct unit known as a Faculty, School, Department, Centre or Division, which has a clear identity within education institutions.

- The school has a designated Head or Director 1 who has demonstrated administrative, scholarly and professional competence, preferably in the profession of social work.

- The Head or Director has primary responsibility for the co-ordination and professional leadership of the school, with sufficient time and resources to fulfil these responsibilities.

- The social work programme’s budgetary allocation is sufficient to achieve its core purpose or mission and the programme objectives.

- The budgetary allocation is stable enough to ensure programme planning and delivery in a sustainable way.

- The necessary clerical and administrative staff, as well as educators, is made available for the achievement of the programme objectives. These staff members are provided with reasonable amounts of autonomy and opportunity to contribute programme development, implementation, and evaluation.

- Irrespective of the mode of teaching (in the classroom, distance, mixed-mode, decentralised and/or internet-based education) there is the provision of adequate infrastructure, including classroom space, computers, texts, audio-visual equipment, community resources for practice education, and on-site instruction and supervision to facilitate the achievement of its core purpose or mission, programme objectives and expected outcomes.

- Internet-based education should not fully substitute spaces for face-to-face instruction, practice learning and dialogue. Face-to-face spaces are critical for a well rounded social work education and therefore irreplaceable.

Social Work courses tend to be administratively complex and resource-demanding due to the synthesis of the theoretical, research and practice-based elements, including relational training and service user interaction. Therefore, Schools could aspire to achieve the following:

- Sufficient physical facilities, including classroom space, offices for the educators and the administrative staff and space for student, faculty and field- liaison meetings.

- Adequate equipment necessary for the achievement of the school’s core purpose or mission and the programme objectives.

- High quality of the education programme whatever the mode of delivery. In the case of distance, mixed-mode, decentralised and/or internet-based teaching, mechanisms for locally based instruction and supervision should be put in place, especially with regard to the practice component of the programme.

- Well-resourced on-site and online libraries, knowledge and research environment, and, where possible, internet resources, all necessary to achieve the programme objectives.

- Access to international libraries, international roaming services (e.g., EduRoam), e-journals and databases.

3. Curriculum

back to top With regard to standards regarding programme curricula, schools must consistently ensure the following:

- The curricula and methods of instruction are consistent with the school’s programme objectives, its expected outcomes and its mission statement.

- Clear mechanisms for the organisation’s implementation and evaluation of the theory and field education components of the programme exist.

- Specific attention to undertaking constant review and development of the curricula.

- Clear guidelines for ethical use of technology in practice, curriculum delivery, distance/blended learning, big data analysis and engagement with social media

Schools should always aspire to develop curricula that:

- Help social work students to develop skills of critical thinking and scholarly attitudes of reasoning, openness to new experiences and paradigms and commitment to lifelong learning.

- Are sufficient in duration 2 and learning opportunities to ensure that students are prepared for professional practice. Students and educators are given sufficient space and time to adhere to the minimum standards described herein.

- Reflect the needs, values and cultures of the relevant populations.

- Are based on human rights principles and the pursuit of justice.

4. Core Curricula

back to top Social work education programs vary by economic and political contexts, practice settings, population served, type of personal and social, economic, political, or environmental issues addressed, and practice theories and approaches used. Nevertheless, there are certain core curricula that are universally applicable. Thus, the school must ensure that social work students, by the end of their first Social Work professional qualification 3 , have had sufficient/required and relevant exposure to the following core curricula which are organised into the following broad conceptual components:

a) Social Work in Context: refers to the broader knowledge that is required in order to critically understand the political, socio-legal, cultural and historical forces that have shaped social work.

b) Social Work in Practice: refers to a broader set of skills and knowledge required to design and deliver e ff ective, ethical and competent interventions.

The above two conceptual components are interdependent, dynamic and should be considered simultaneously.

Social Work In Context

back to top In relation to Social Work in Context, education programmes must include the following:

- Critical understanding of how socio-structural inadequacies, discrimination, oppression, and social, political, environmental and economic injustices impact human development at all levels, including the global must be considered.

- Knowledge of how traditions, culture, beliefs, religions and customs influence human development across the lifespan, including how these might constitute resources and/or obstacles to growth.

- Knowledge of theories of social work, social sciences, humanities and indigenous knowledges

- Critical understanding of social work’s origins and purposes.

- Critical understanding of historical injustices affecting service user communities and the role of social workers in addressing those.

- Sufficient knowledge of related occupations and professions to facilitate interprofessional collaboration and teamwork.

- Knowledge of social welfare policies (or lack thereof), services and laws at local, national and/or regional/international levels

- Understanding of the roles of social work in policy planning, implementation, evaluation and in social change processes.

- Knowledge of – human rights, social movements and their interconnectedness with class, gender and ethnic/race-related issues.

- Knowledge of relevant international treaties, laws and regulations, and global standards such as the Social Development Goals.

- Critical understanding of the impact of environmental degradation on the well-being of our communities and the promotion of Environmental Justice.

- A focus on gender equity

- An understanding of structural causes and impact of gender-based violence

- An emphasis on structural issues affecting marginalised, vulnerable and minority populations.

- The assumption, identification and recognition of strengths and potential of all human beings.

- Social Work contribution to promoting sustainable peace and justice in communities affected by political/ethnic conflict and violence.

Social Work in Practice

back to top In relation to Social Work In Practice, education programmes must prepare students to:

- Apply knowledge of human behaviour and development across the lifespan.

- Understand how social determinants impact on people’s health and wellbeing (mental, physical, emotional and spiritual).

- Promote healthy, cohesive, non-oppressive relationships among people and between people and organisations at all levels –individuals, families, groups, programs, organizations, communities.

- Facilitate and advocate for the inclusion of different voices, especially those of groups that have experienced marginalisation and exclusion.

- Understand the relationship between personal life experiences and personal value systems and social work practice.

- Integrate theory, ethics, research/knowledge in practice.

- Have sufficient practice skills in assessment, relationship building, empowerment and helping processes to achieve the identified goals of the programme and fulfil professional obligations to service users. The programme may prepare practitioners to serve purposes, including providing social support, and engaging in developmental, protective, preventive and/or therapeutic intervention – depending on the particular focus of the programme or professional practice orientation.

- Apply social work intervention that is informed by principles, knowledge and skills aimed at promoting human development and the potentialities of all people

- Engage in critical analysis of how social policies and programmes promote or violate human rights and justice

- Use peace building, non-violent activism and human rights-based advocacy as intervention methods.

- Use problem-solving and strengths-based approaches.

- Develop as critically self-reflective practitioners.

- Apply national, regional and/or international social work codes of ethics and their applicability to context-specific realities

- Ability to address and collaborate with others regarding the complexities, subtleties, multi-dimensional, ethical, legal and dialogical aspects of power.

Practice Education (Placement) 4

back to top Practice education is a critical component of professional social work education. Thus practice education should be well integrated into the curriculum in preparing students with knowledge, values and skills for ethical, competent and effective practice. Practice education must be sufficient in duration and complexity of tasks and learning opportunities to ensure that students are prepared for professional practice. Therefore, schools should also ensure:

- A well-developed and comprehensive practice education manual that details its practice placement standards, procedures, assessment standards/criteria and expectations should be made available to students, field placement supervisors and field placement instructors.

- selection of practice placement sites;

- matching students with placement sites;

- placement of students;

- supervision of students;

- coordination of with the program;

- supporting students and the field instructors;

- monitoring student progress and evaluating student performance in the field; and

- evaluating the performance of the practice education setting.

- Appointment of practice supervisors or instructors who are qualified and experienced, as determined by the development status of the social work profession in any given country, and provision of orientation for practice supervisors or instructors.

- Provision of orientation and ongoing supports, including training and education to practice supervisors.

- Ensuring that adequate and appropriate resources, to meet the needs of the practice component of the programme, are made available.

- Policies for the inclusion of marginalized populations, and reasonable accommodation and adjustment for people with disabilities and special needs.

- The practice education component provides ongoing, timely and developmental feedback to students.

Schools also should aspire to:

- Create practice placement opportunities that correspond to at least 25% of the overall education activity within the courses (counted in either credits, days, or hours).

- Nurture valuable partnerships between the education institution and the agency (where applicable) and service users in decision-making regarding practice education and the evaluation of student’s performance.

- If the programme engages in international placements, additional standards, guidelines and support should be provided to both students placed abroad and agencies in the receiving end. In addition the programme should have mechanisms to facilitate reciprocity, co-learning genuine knowledge exchange.

5. Research and Scholarly activity

back to top As an academic discipline, social work is underpinned by theories of social work, social sciences, humanities and indigenous knowledges. Social work knowledge and scholarship are generated through a diverse range of sources, including education providers, research organisations, independent researchers, local communities, social work organisations, practitioners and service users. All education providers should aspire to make a contribution to the development, critical understanding and generation of social work scholarship. This can be achieved, when and where possible, through the incorporation of research and scholarship strategies, including:

- An emphasis on the process of knowledge production in social work, by explaining different methodological approaches within the discipline and how these have evolved.

- An appreciation of the rigorous and diverse methods used by social workers in order to appraise the credibility, transferability, confirmability reliability and validity of information.

- Teaching that is informed by current, valid and reliable evidence.

- Provision of opportunities for students to critically appraise research findings and acquire research skills.

- Involvement of students in research activities.

- Support students to acquire and develop programme/practice evaluation skills, including partnering with them in such work.

1 Depending on the setting, other titles may be used to signify administrative leadership. 2 In many contexts, a first professional qualification (or baccalaureate degree in social work) is completed in within three or four years of full-time studies, although the amount of non-social work course contents included may vary. 3 See description above. 4 The terms “field education” and “field instruction” are also commonly used.

back to top Social Work programmes comprise a dynamic intellectual, social and material community. This community brings together students, educators, administrators and service users united in their effort to enhance opportunities for learning, professional and personal development.

1. Educators

back to top With regard to social work educators 5 , schools and programmes must ensure:

- The provision of educators, adequate in number and range of expertise, who have appropriate qualifications, including practice and research experience within the field of Social Work; all determined by the development status of the social work profession in any given country.

- Educator representation and inclusion in decision-making processes of the school or programme related to the development of the programme’s core purpose or mission, in the formulation of the objectives, curriculum design and expected outcomes of the programme.

- A clear statement of its equity-based policies or preferences, with regard to considerations of gender, ethnicity, ‘race’ or any other form of diversity in its recruitment and appointment of members of staff.

- Policies regarding the recruitment, appointment and promotion of staff are clearly articulated and transparent and are in keeping with other schools or programs within the education institution.

- Policies that are in-line with national labour legislation and also take into consideration International Labour Organisation guidelines. f. Educators benefit from a cooperative, supportive and productive working environment to facilitate the achievement of programme objectives.

- Institutional policies regarding promotion, tenure, discipline and termination are transparent and clear. Mechanisms for appeal and decision review should be in place.

- Teaching and other relevant workload are distributed equitably and transparently.

- Variations in workload distribution in terms of teaching, scholarship (including research) and service are inevitable. However, workload allocation should be based on principles such as equity and respect for educators’ diverse skills, expertise and talents.

- When there are differences and conflicts, transparent and fair mechanisms are in place to address them.

All Schools should also aspire to:

- Provide a balanced allocation of teaching, practice placement instruction, supervision and administrative workloads, ensuring that there is space for engagement with all forms of scholarship including creative work and research.

- With regards to educators involvement, a minimum of a Master’s level qualification in social work is preferred.

- Staff reflect the ethics, values and principles of the social work profession in their work on behalf and with students and communities.

- The school, when possible, nurtures interdisciplinary approaches. To this effect, the School, strives to engage educators from relevant disciplines such as sociology, history, economics, statistics etc.

- At least 50% of educators should have a social work qualification, and social work modules or courses should be taught by educators with a Master of Social work qualification, in line with the status of the profession in each country.

- The School has provisions for the continuing professional development of its educators.

2. Students

back to top In respect of social work students, Schools must ensure:

- Clear articulation of its admission criteria and procedures. When possible, practitioners and service users should be involved in the relevant processes.

- Non-discrimination against any student on the basis of race, colour, culture, ethnicity, linguistic origin, religion, political orientation, gender, sexual orientation, age, marital status, functional status, and socio-economic status.

- Explicit criteria for the evaluation of practice education

- Grievance and appeals procedures which are accessible, clearly explained to all students and operated without prejudice to the assessment of students.

- All information regarding, assessment, course aims and structure, learning outcomes, class attendance, examination rules, appeals procedures and student support services should be clearly articulated and provided to the students in the form of a handbook (printed or electronic) at the beginning of each academic year.

- Ensure that social work students are provided with opportunities to develop self-awareness regarding their personal and cultural values, beliefs, traditions and biases and how these might influence the ability to develop relationships with people and to work with diverse population groups.

- Provide information about the kinds of support available to students, including academic, financial, employment and personal assistance

- Students should be clear about what constitutes misconduct, including academic, harassment and discrimination, policies and procedures in place to address these.

- Comprehensive retention policies that prioritise student well-being.

- Positive action should be taken to ensure the inclusion of minority groups that are underrepresented and/or under-served.

- Democratic and sustained representation of students in decision-making committees and fora.

3. Service Users 6

back to top With regards to service user involvement Schools must :

- Incorporate the rights, views and interests of Service Users and broader communities served in its operations, including curriculum development, implementation and delivery.

- Develop a proactive strategy towards facilitating Service User involvement in all aspects of design, planning and delivery of study programmes.

- Ensure reasonable adjustments are made in order to support the involvement of Service Users.

Also aspire to:

- Create opportunities for the personal and professional development of Service Users involved in the study programme.

5 Different terminologies are used to represent and or describe the people providing the education (ie academics, faculty, instructors, pedagogues, teachers, tutors, lecturers etc.). For the purposes of this document we have adopted the term “Social Work Educators” to represent these diverse terminologies. 6 Depending on the context, other terms, including clients and community constituents are used instead of service users.

The Profession

back to top Social Work Schools are members of a global professional and academic community. As such, they must be able to contribute to and benefit from the growth of scholarly, practice and policy development at a national and global level. Nurturing, expanding and formalising links with the national and international representative bodies of the social work profession is of paramount importance.

1. A shared understanding of the Profession

back to top Schools must ensure the following:

- Definitions of social work used in the context of the education process should be congruent with the Global Definition of Social Work as approved by IASSW and IFSW including any regional applications that may exist.

- Schools retain close and formal relationships with representatives and key stakeholders of the social work profession, including regulators and national and regional associations of social work practice and education.

- Registration of professional staff and social work students (insofar as social work students develop working relationships with people via practice placements) with national and/or regional regulatory (whether statutory or non-statutory) bodies.

- All stakeholders involved in social work education should actively seek to contribute to and benefit from the global social work community in a spirit of partnership and international solidarity.

Schools should also aspire to:

- monitor students’ employability rates and encourage them to actively participate in the national and global social work community.

2. Ethics and Values

back to top In view of the recognition that social work values, ethics and principles are the core components of the profession, Schools must consistently ensure:

- Adhered to the Global Ethics Statement approved bythe IFSWW and IASSW.

- Adherence to the National and Regional Codes of Ethics.

- Adherence to the Global Definition of Social Work as approved by the IFSW and IASSW.

- Clear articulation of objectives with regard to social work values, principles and ethical conduct. Ensuring that every social work student involved in practice education, and every academic staff member, is aware of the boundaries of professional practice and what might constitute unprofessional conduct in terms of the code of ethics.

- Taking appropriate, reasonable and proportionate action in relation to those social work students and academic staff who fail to comply with the code of ethics, either through an established regulatory social work body, established procedures of the educational institution, and/or through legal mechanisms.

Schools should also aspire towards:

- Upholding, as far as is reasonable and possible, the principles of restorative rather than retributive justice in disciplining either social work students or academic staff who violate the code of ethics.

3. Equity and Diversity

back to top With regard to equity and diversity Schools must :

- Make concerted and continuous efforts to ensure the enrichment of the educational experience by reflecting cultural, ethnic and other forms of diversity in its programme and relevant populations.

- Ensure that educators, students and service users are provided with equal opportunities to learn and develop regardless of gender,socioeconomicc background, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation and other forms of diversity.

- Ensure that the programme has clearly articulated learning objectives in upholding the principles of respect for cultural and ethnic diversity, gender equity, human rights.

- Address and challenge racist, homophobic, sexist and other discriminatory behaviours, policies and structures.

- Recognition and development of indigenous or locally specific social work education and practice from the traditions and cultures of different ethnic groups and societies, insofar that such traditions and cultures are congruent with our ethical codes and human rights commitments.

4. Human rights and Social, Economic and Environmental Justice

back to top Social, Economic and Environmental Justice are fundamental pillars underpinning social work theory, policy and practice. All Schools must :

- Prepare students to be able to apply human rights principles (as articulated in the International Bill of Rights and core international human rights treaties) to frame their understanding of how current social issues affect social, economic and environmental justice.

- Ensure that their students understand the importance of social, economic, political and environmental justice and develop relevant intervention knowledge and skills.

- Contribute to collective efforts within and beyond school structures in order to achieve social, economic and environmental justice.

They should also aspire to:

- Identifying opportunities for supporting development at grass roots level and community participatory action to meet the aspirations of the Social Development Goals.

- Making use of opportunities to exchange knowledge, expertise and ideas with global peers to support the advancement of social work education free from colonial influences.

- Creating platforms for Indigenous social workers to shape curricula and relevant courses.

Members of the Joint Taskforce

back to top

IFSW Interim Education Commission

Chair : Vasilios Ioakimidis

Members: African Regional Commissioners: Lawrence Mukuka and Zena Mnasi Asia and Pacific Regional Commissioner: Mariko Kimura European Regional Commissioner: Nicolai Paulsen Latin American and Caribbean Regional Commissioner: Marinilda Rivera Díaz North American Regional Commissioners: Dr. Joan Davis-Whelan and Dr. Gary Bailey

IASSW Global Standards Taskforce

Chair: Dixon Sookraj

Members: Carmen Castillo (COSTA RICA): Member, Latin American Rep. Karene Nathaniel-DeCaires (TRINIDAD & TOBAGO): Member, North American/Caribbean Rep. Liu Meng (CHINA): Member, China National Rep. Teresa Francesca Bertotti (ITALY): Member, European Association Rep. Alexandre Hakizamunga (RWANDA): Member, African Association Rep. Vimla Nadkarni (INDIA): Member, Past IASSW President Emily Taylor (CANADA): Student Rep. Ute Straub (GERMANY): IASSW Co-Chair & Board Representative

Consultants: Carol S. Cohen (USA): Commission on Group Work in Social Work Education of the International Association for Social Work with Groups, Co-Chair. Shirley Gatenio Gabel (USA). Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, Co-Editor Varoshini Nadesan (SOUTH AFRICA). Association of South African Social Work Education Institutions, President.

- Login / Account

- Documentation

- Online Participation

- Constitution/ Governance

- Secretariat

- Our members

- General Meetings

- Executive Meetings

- Meeting papers 2018

- Global Definition of Social Work

- Meet Social Workers from around the world

- Frequently Asked Questions

- IFSW Africa

- IFSW Asia and Pacific

- IFSW Europe

- IFSW Latin America and Caribbean

- IFSW North America

- Education Commission

- Ethics Commission

- Indigenous Commission

- United Nations Commission

- Information Hub

- Upcoming Events

- Keynote Speakers

- Global Agenda

- Archive: European DM 2021

- The Global Agenda

- World Social Work Day

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

- PMC10187493

Characteristics and Outcomes of School Social Work Services: A Scoping Review of Published Evidence 2000–June 2022

1 Steve Hicks School of Social Work, The University of Texas at Austin, 1925 San Jacinto Blvd 3.112, Austin, TX 78712 USA

Estilla Lightfoot

2 School of Social Work, Western New Mexico University, Silver City, NM USA

Ruth Berkowitz

3 School of Social Work, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel

Samantha Guz

4 Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL USA

Cynthia Franklin

Diana m. dinitto.

School social workers are integral to the school mental health workforce and the leading social service providers in educational settings. In recent decades, school social work practice has been largely influenced by the multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) approach, ecological systems views, and the promotion of evidence-based practice. However, none of the existing school social work reviews have examined the latest characteristics and outcomes of school social work services. This scoping review analyzed and synthesized the focuses and functions of school social workers and the state-of-the-art social and mental/behavioral health services they provide. Findings showed that in the past two decades, school social workers in different parts of the world shared a common understanding of practice models and interests. Most school social work interventions and services targeted high-needs students to improve their social, mental/behavioral health, and academic outcomes, followed by primary and secondary prevention activities to promote school climate, school culture, teacher, student, and parent interactions, and parents’ wellbeing. The synthesis also supports the multiple roles of school social workers and their collaborative, cross-systems approach to serving students, families, and staff in education settings. Implications and directions for future school social work research are discussed.

Introduction

This scoping review examines the literature on school social work services provided to address children, youth, and families’ mental/behavioral health and social service-related needs to help students thrive in educational contexts. School social work is a specialty of the social work profession that is growing rapidly worldwide (Huxtable, 2022 ). They are prominent mental/behavioral health professionals that play a crucial role in supporting students’ well-being and meeting their learning needs. Although the operational modes of school social work services vary, for instance, operating within an interdisciplinary team as part of the school service system, or through non-governmental agencies or collaboration between welfare agencies and the school system (Andersson et al., 2002 ; Chiu & Wong, 2002 ; Beck, 2017 ), the roles and activities of school social work are alike across different parts of the world (Allen-Meares et al., 2013 ; International Network for School Social Work, 2016, as cited in Huxtable, 2022 ). School social workers are known for their functions to evaluate students’ needs and provide interventions across the ecological systems to remove students’ learning barriers and promote healthy sociopsychological outcomes in the USA and internationally (Huxtable, 2022 ). In the past two decades, school social work literature placed great emphasis on evidence-based practice (Huxtable, 2013; 2016, as cited in Huxtable, 2022 ); however, more research is still needed in the continuous development of the school social work practice model and areas such as interventions, training, licensure, and interprofessional collaboration (Huxtable, 2022 ).

The school social work practice in the USA has great influence both domestically and overseas. Several core journals in the field (e.g., the International Journal of School Social Work, Children & Schools ) and numerous textbooks have been translated into different languages originated in the USA (Huxtable, 2022 ). In the USA, school social workers have been providing mental health-oriented services under the nationwide endorsement of multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) (Avant & Lindsey, 2015 ; Barrett et al., 2020 ). In the past two decades, efforts at developing a school social work practice model recommended that school social workers have a master’s degree, embrace MTSS and use evidence-based practices (EBP) (Frey et al., 2012 ). Similar licensure requirements have been reported in other parts of the world (International Network for School Social Work, 2016, as cited in Huxtable, 2022 ), but the current state of research on MTSS and EBP applications in other countries is limited (Huxtable, 2022 ). Furthermore, although previous literature indicated more school social workers applied EBP to primary prevention, including trauma-informed care, social–emotional learning, and restorative justice programs in school mental health services (Crutchfield et al., 2020 ; Elswick et al., 2019 ; Gherardi, 2017 ), little research has been done to review and analyzed the legitimacy of the existing school social work practice model and its influence in the changing context of school social work services. The changing conditions and demands of social work services in schools require an update on the functions of school social workers and the efficacy of their state-of-the-art practices.

Previous Reviews on School Social Work Practice and Outcomes

Over the past twenty years, a few reviews of school social work services have been conducted. They include outcome reviews, systematic reviews, and one meta-analysis on interventions, but none have examined studies from a perspective that looks inclusively and comprehensively at evaluations of school social work services. Early and Vonk ( 2001 ), for example, reviewed and critiqued 21 controlled (e.g., randomized controlled trial [RCT] and quasi-experimental) outcome studies of school social work practice from a risk and resilience perspective and found that the interventions are overall effective in helping children and youth gain problem-solving skills and improve peer relations and intrapersonal functioning. However, the quality of the included studies was mixed, demographic information on students who received the intervention, such as race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and special education enrollment were missing, and the practices were less relevant to the guidelines in the school social work practice model (National Association of Social Workers [NASW], 2012 ). Later, Franklin et al. ( 2009 ) updated previous reviews by using meta-analytic techniques to synthesize the results of interventions delivered by social workers within schools. They found that these interventions had small to medium treatment effects for internalizing and externalizing problems but showed mixed results in academic or school-related outcomes. Franklin et al. ( 2009 ) approached the empirical evidence from an intervention lens and did not focus on the traits and characteristics of school social workers and their broad roles in implementing interventions; additionally, demographic information, symptoms, and conditions of those who received school social work services were lacking. Allen-Meares et al. ( 2013 ) built on Franklin and colleagues’ ( 2009 ) meta-analysis on school social work practice outcomes across nations by conducting a systematic review with a particular interest in identifying tier 1 and tier 2 (i.e., universal prevention and targeted early intervention) practices. School social workers reported services in a variety of areas (e.g., sexual health, aggression, school attendance, self-esteem, depression), and half of the included interventions were tier 1 (Allen-Meares et al., 2013 ). Although effect sizes were calculated (ranging from 0.01–2.75), the outcomes of the interventions were not articulated nor comparable across the 18 included studies due to the heterogeneity of metrics.

Therefore, previous reviews of school social work practice and its effectiveness addressed some aspects of these interventions and their outcomes but did not examine school social workers’ characteristics (e.g., school social workers’ credentials) or related functions (e.g., interdisciplinary collaboration with teachers and other support personnel, such as school counselors and psychologists). Further, various details of the psychosocial interventions (e.g., service type, program fidelity, target population, practice modality), and demographics, conditions, or symptoms of those who received the interventions provided by school social workers were under-researched from previous reviews. An updated review of the literature that includes these missing features and examines the influence of current school social work practice is needed.

Guiding Framework for the Scoping Review

The multi-tiered systems of support model allows school social workers to maximize their time and resources to support students’ needs accordingly by following a consecutive order of prevention. MTSS generally consists of three tiers of increasing levels of preventive and responsive behavioral and academic support that operate under the overarching principles of capacity-building, evidence-based practices, and data-driven decision-making (Kelly et al., 2010a ). Tier 1 interventions consist of whole-school/classroom initiatives (NASW, 2012 ), including universal positive behavior interventions and supports (PBIS) (Clonan et al., 2007 ) and restorative justice practices (Lustick et al., 2020 ). Tier 2 consists of targeted small-group interventions meant to support students at risk of academic or behavioral difficulties who do not respond to Tier 1 interventions (National Association of Social Workers, 2012 ). Finally, tier 3 interventions are intensive individual interventions, including special education services, meant to support students who do not benefit sufficiently from Tier 1 or Tier 2 interventions.

The current school social work practice model in the USA (NASW, 2012 ) consists of three main aspects: (1) delivering evidence-based practices to address behavioral and mental health concerns; (2) fostering a positive school culture and climate that promotes excellence in learning and teaching; (3) enhancing the availability of resources to students within both the school and the local community. Similar expectations from job descriptions have been reported in other countries around the world (Huxtable, 2022 ).

Moreover, school social workers are specifically trained to practice using the ecological systems framework, which aims to connect different tiers of services from a person-in-environment perspective and to activate supports and bridge gaps between systems (Huxtable, 2022 ; Keller & Grumbach, 2022 ; SSWAA, n.d.). This means that school social workers approach problem-solving through systemic interactions, which allows them to provide timely interventions and activate resources at the individual, classroom, schoolwide, home, and community levels as needs demand.

Hence, the present scoping review explores and analyzes essential characteristics of school social workers and their practices that have been missed in previous reviews under a guiding framework that consists of the school social work practice model, MTSS, and an ecological systems perspective.

This scoping review built upon previous reviews and analyzed the current school social work practices while taking into account the characteristics of school social workers, different types of services they deliver, as well as the target populations they serve in schools. Seven overarching questions guided this review: (1) What are the study characteristics of the school social work outcome studies (e.g., countries of origin, journal information, quality, research design, fidelity control) in the past two decades? (2) What are the characteristics (e.g., demographics, conditions, symptoms) of those who received school social work interventions or services? (3) What are the overall measurements (e.g., reduction in depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], improvement in parent–child relationships, or school climate) reported in these studies? (4) What types of interventions and services were provided? (5) Who are the social work practitioners (i.e., collaborators/credential/licensure) delivering social work services in schools? (6) Does the use of school social work services support the promotion of preventive care within the MTSS? (7) What are the main outcomes of the diverse school social work interventions and services?

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first scoping review to examine these aspects of school social work practices under the guidance of the existing school social work practice model, MTSS, and an ecological systems perspective.

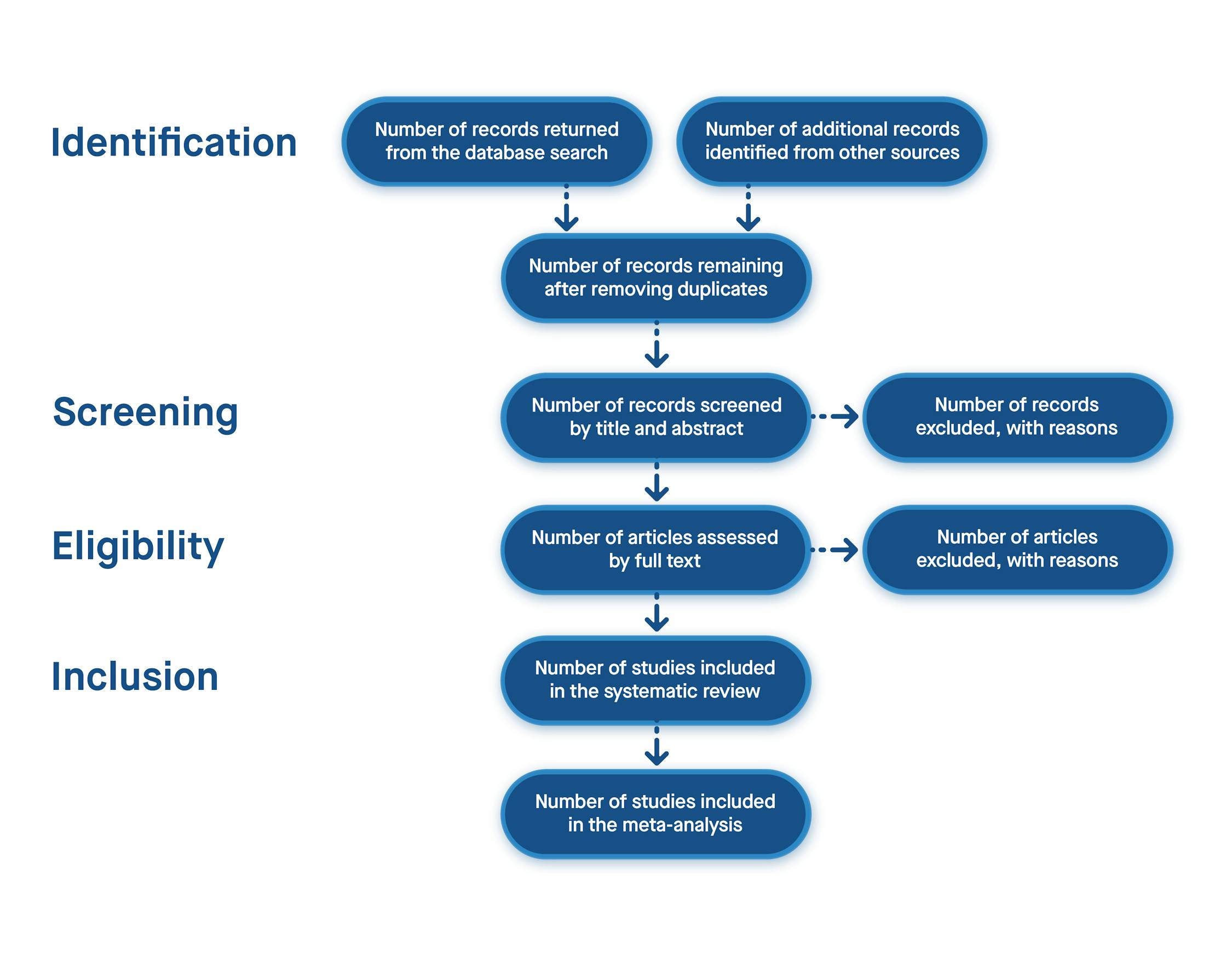

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension guidelines for completing a scoping review (Tricco et al., 2018 ) were followed for planning, conducting, and reporting the results of this review. The PRISMA scoping review checklist includes 20 essential items and two optional items. Together with the 20 essential items, the optional two items related to critical appraisal of included sources of evidence were also followed to assure transparency, replication, and comprehensive reporting for scoping reviews.

Search Strategy

The studies included in this review were published between 2000 and June 2022. These studies describe the content, design, target population, target concerns, delivery methods, and outcomes of services, practices, and interventions conducted or co-led by school social workers. This time frame was selected since it coincides with the completion of the early review of characteristics of school social work outcomes studies (Early & Vonk, 2001 ); furthermore, scientific approaches and evidence-based practice were written in the education law for school-based services since the early 2000s in the USA, which greatly impacted school social work practice (Wilde, 2004 ), and was reflected in the trend of peer-reviewed research in school practice journals (Huxtable, 2022 ).

Following consultation with an academic librarian, the authors systematically searched relevant articles in seven academic databases (APA PsycINFO, Education Source, ERIC, Academic Search Complete, SocINDEX, CINAHL Plus, and MEDLINE) between January 2000 and June 2022. These databases were selected due to the relevance of the outcomes and the broad range of relevant disciplines they cover. When built-in search filters were available, the search included only peer-reviewed journal articles or dissertations written in English and published between 2000 and 2022. The search terms were adapted from previous review studies with a similar purpose (Franklin et al., 2009 ). The rationale for adapting the search terms from a previous meta-analysis (Franklin et al., 2009 ) was to collect outcomes studies and if feasible (pending on the quality of the outcome data and enough effect sizes available) to do a meta-analysis of outcomes. Each database was searched using the search terms: (“school social work*”) AND (“effective*” OR “outcome*” OR “evaluat*” OR “measure*”). The first author did the initial search and also manually searched reference lists of relevant articles to identify additional publications. All references of included studies were combined and deduplicated for screening after completion of the manual search.

Eligibility Criteria

The same inclusion and exclusion criteria were used at all stages of the review process. Studies were included if they: (1) were original research studies, (2) were published in peer-reviewed scientific journals or were dissertations, (3) were published between 2000 and 2022, (4) described school social work services or identified school social workers as the practitioners, and (5) reported at least one outcome measure of the efficacy or effectiveness of social work services. Studies could be conducted in any country and were included for full-text review if they were published in English. The authors excluded: (1) qualitative studies, (2) method or conceptual papers, (3) interventions/services not led by school social workers, and (4) research papers that focused only on sample demographics (not on outcomes). Qualitative studies were excluded because though they often capture themes or ideas, experiences, and opinions, they rely on non-numeric data and do not quantify the outcomes of interventions, which is the focus of the present review. If some conditions of qualification were uncertain based on the review of the full text, verification emails were sent to the first author of the paper to confirm. Studies of school social workers as the sample population and those with non-accessible content were also excluded. If two or more articles (e.g., dissertation and journal articles) were identified with the same population and research aim, only the most recent journal publication was selected to avoid duplication. The protocol of the present scoping review can be retrieved from the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/4y6xp/?view_only=9a6b6b4ff0b84af09da1125e7de875fb .

A total of 1,619 records were initially identified. After removing duplicates, 834 remained. The first and the fourth author conducted title and abstract screening independently on Rayyan, an online platform for systematic reviews (Ouzzani et al., 2016 ). Another 760 records were removed from the title and abstract screening because they did not focus on school social work practice, were theory papers, or did not include any measures or outcomes, leaving 68 full-text articles to be screened for eligibility. Of these, 16 articles were selected for data analysis. An updated search conducted in June 2022 identified two additional studies. The combined searches resulted in a total of 18 articles that met the inclusion criteria. The first and the fourth author convened bi-weekly meetings to resolve disagreements on decisions. Reasons and number for exclusion at full-text review were reported in the reasons for exclusion in the PRISMA chart. The PRISMA literature search results are presented in Fig. 1 .

PRISMA Literature Search Record

Data Extraction

A data extraction template was created to aid in the review process. The information collected from each reference consists of three parts: publication information, program features, and practice characteristics and outcomes. Five references were randomly selected to pilot-test the template, and revisions were made accordingly. To assess the quality of the publication and determine the audiences these studies reached, information on the publications was gathered. The publication information included author names, publication year, country/region, publication type, journal name, impact factor, and the number of articles included. The journal information and impact factors came from the Journal Citation Reports generated by Clarivate Analytics Web of Science (n.d.). An impact factor rating is a proxy for the relative influence of a journal in academia and is computed by dividing the number of citations for all articles by the total number of articles published in the two previous years (Garfield, 2006 ). Publication information is presented in Table Table1. 1 . Program name, targeted population, sample size, demographics, targeted issues, treatment characteristics, MTSS level, and main findings (i.e., outcomes) are included in Table Table2. 2 . Finally, intervention features consisting of study aim and design, manualization, practitioners’ credential, fidelity control, type of intervention, quality assessment, and outcome measurement are presented in Table Table3. 3 . Tables Tables2 2 and and3 3 are published as open access for review and downloaded in the Texas Data Repository (Ding, 2023 ).

Journals Reviewed, Impact Factor, and Number of Articles Selected for Review

| Journal title | *IF | # of Articles |

|---|---|---|

| School Social Work Journal | – | 2 |

| Social Work in Public Health | 1.128 | 1 |

| International Social Work | 2.071 | 1 |

| Children & Schools (formerly Social Work in Education) | – | 5 |

| Social Work Research | 1.844 | 1 |

| Research on Social Work Practice | 2.236 | 1 |

| Contemporary School Psychology | – | 1 |

| Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry | 13.113 | 1 |

| The European Research Institute for Social Work (ERIS) Winter 2020 | – | 1 |

| Journal of Child and Family Studies | 2.784 | 1 |

| Georgia School Counselors Association Journal | – | 1 |

* The definition of impact factor (IF) is from Journal Citation Reports produced by Clarivate Analytics. IF is calculated based on a two-year period by dividing the number of citations in the JCR year by the total number of articles published in the two previous years

General Information on the Included School Social Work Practices

| Author | Program Name | Sample Size | Demographics (Mean age/age range, race/ethnicity) | Targeted Issues | Population | Treatment Characteristics (Length & Frequency) | MTSS | Main Findings (significance & effect sizes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acuna et al. ( ), USA | Back to Basics Parenting Training | 131 | 97.6% Latina/o, 2.4% Black; 87.9% participated in FRLP; 89.3% were mothers; 5–11 yo; 58% boys; 42% girls | Effective parenting and child’s mental health/behavioral outcomes | Student & parent | 120 min/tx; up to 10 weekly sessions | Tier 2 | Significant improvements found in all child behaviors post-intervention. Intervention had a large effect size (d = 1.11) for home bx change, with large to moderate Effect sizes for social bx (d = 0.70), academic bx (d = 0.65), and school attendance bx (d = 0.49) |

| Al-Rasheed et al. ( ), Kuwait | Fostering Youth Resilience Project | 54 | 16.34 yo; 37% female | Promoting resilience, adaptive coping skills, and effective problem-solving | Student | 60 min/tx; 9 sessions | Tier 1 | At post-intervention, significant increases found in total resilience skills score, goal setting, critical thinking, and decision-making, self-esteem and respect, negotiation and conflict resolution, and social support and anger management skills |

| Chupp and Boes ( ), USA | Too Good for Violence: A Curriculum for Non-Violent Living | 8 | 9–10 yo; 50% boys, 50% girls; 62.5% Black, 25% White, and 12.5% Multi-racial | Promoting social skills | Student | 40 min/tx; 8 weekly sessions | Tier 1 | Average student knowledge score increased by 8.3%; the majority increased in emotional skills, and a third showed improvement in inappropriate social behaviors; 33% reported improvement in grades |

| Elsherbiny et al. ( ), Egypt | Preventive Social Work Program | INT = 24 CON = 24 | 4–6 yo; 42% girls; enrolled in an inner-city private school | School refusal | Student, parent & teacher | 20–30 min/tx; 4 phases, 30 sessions over a year | Tier 2 | Compared to control group, improvements in the tx group were found for all four main hypotheses related to school refusal behaviors (e.g., decrease in school-avoiding stimuli, aversive social situations, attention-seeking, and tangible forces-seeking outside of school) at posttest and 6-month follow-up |

| Ervin et al. ( ), USA | Behavior Skills Training | 6 | 8–18 yo ( = 12.3); 100% enrolled in special ed | Classroom behaviors & academic difficulties | Student | 3 0 min/tx | Tier 2 | BST was effective in the classroom setting. Response to disruptive bx measurement showed large effect size (d) for all students, a decrease in disruptive behavior engagement was observed in both classrooms, and effect size was moderate or large for all students |

| Fein et al. ( ), USA | Families Over coming Under Stress Resilience Curriculum for Parents | 96 | NR | Trauma-informed resilience development | Parent | 60–90 min/tx; 7 sessions | Tier 2 | Parents’ improved significantly on one resilience item (“I am able to adapt when changes occur.”), in family functioning (d = 0.41), parent connectedness (d = 0.71) and social support (d = 0.66) from pre to post |

| Ijadi-Maghsoodi et al. ( ), USA | Resilience Classroom Curriculum | 100 | NR | Resilience development | Student & teacher | 45-55 min (or 2 25 min if needed)/tx; weekly or monthly; 9 sessions | Tier 1 | Significant improvements in empathy and problem-solving observed as well as internal assets. Improved school support reported but not statistically significant. Lower odds of a positive PTSD screen were observed at posttest but not statistically significant. Medium effect sizes for improvements in problem-solving and overall internal assets; small effect size for empathy |

| Kataoka et al. ( ), USA | Mental Health for Immigrants Program | INT = 152 CON = 47 | 11.5 yo; 50% female, 100% immigrant Hispanic-speaking students in both elementary and middle schools | Trauma-related depression and/or PTSD symptoms | Student, parent, & teacher | One school period; 8 weekly sessions | Tier 2 | Depression symptoms in the intervention group decreased from a mean CDI score of 16 to 14, and CPSS decreased from 19 to 13; no statistically significant CDI or CPSS difference for waitlist group. At 3-month follow-up, participants’ CDI scores were significantly lower than waitlist group |

| Kelly and Bluestone-Miller ( ), USA | Working on What Works | 21 | NR | Create positive learning environment | Student & teacher | Over a year | Tier 1 | WOWW resulted in an increase in teachers’ perceptions of their classes as better behaved, and of themselves as more effective classroom managers |

| Magnano ( ), USA | Partners in Success | INT = 20 CON = 20 | 10.4 yo; 12.5% female; 30% Black, 5% Hispanic, 65% White; 37.5% in foster placement; 100% enrolled in special ed; 67.5% had FRPL | Academic problems and anti-social behaviors among students with emotional/behavioral disabilities | Student & Parent | More than 16 weeks | Tier 3 | Participants in both conditions improved in externalizing behaviors and academic skill development. Significant main effects found in some externalizing bxs across time points |

| Newsome ( ), USA | Solution-Focused Brief Therapy | 26 | 11–14 yo ( = 13.19); 27% female; 20% Black, 80% White | School failure | Student | 35 min/tx; 8 weekly sessions; 4 groups | Tier 2 | Social skills ratings indicated students improved dramatically after the 8-week intervention and maintained these gains at six-week follow-up but did not show further improvement |

| Newsome et al. ( ), USA | School social work intervention | INT = 74 CON = 71 | 66% Black, 34 White, 47% female; 70% qualify FRPL (INT only); all participating schools are Title I schools | Academic failure and chronic truancy | Student, parent, & family | Avg number of tx sessions: 5.56 for one-on-one intervention; 2.23 for group counseling; 5.96 for speaking w/youth informally; 1.04 for one-on-one meeting w/guardian; 1.36 for phone conversation about youth; 3.46 for speaking w/teacher about youth informally | Tier 3 | School social work services had a statistically significant impact on reducing risk factors related to truant behaviors among students who received school social work services, but no significant differences between treatment and comparison groups on student absenteeism records |

| Phillips ( ), USA | Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | INT = 33 CON = 31 | 15.5–20.5 ( = 17.7); 63.5% female; 11.1% Black, 23.8% Hispanic, 54% White, 11.1% Other; 34.5% lived with per capita income < $20,000 yr | Adolescent’s depression | Student | 60 min/tx; 6 weekly sessions | Tier 2 | The BDI change score was 3.12 for treatment group and 0.39 for control group. Eta-squared of .148 indicated a small effect. Significant differences between INT and CON groups for females, those with family history of depression, Whites, students with no other tx, and students who reported no recreational drug use |

Sadzaglishvili et al ( ), Georgia | School Social Work Intervention | 81 | 44% female, 2 -6 grade students, high-number socially vulnerable families | School culture and class climate | Student, parent, & family | 45 min/tx; School 1 = 45 class interventions; School 2 = 62; more than 13 months | Tier 1 | Class climate more positive at posttest; students more involved in doing homework together and spent significant more free time together post-intervention; students expressed aggression less frequently; parents helped their children more and met with school administration more often to solve school related issues |

| Thompson and Webber ( ), USA | The Student and Teacher Agreement Realignment Strategy | 10 | 12 yo; 20% female; 30% Black, 70% White; all eligible for IEP | Perceptions of school and classroom norms | Student & teacher | 5–10 min conference; weekly w/SSW; bi-weekly social skill lessons; 18 weeks | Tier 2 | Mean number of office referrals for students during the intervention phase was significantly lower than the baseline means; required fewer suspensions and other reactive forms of discipline and classroom management |

| Wong et al. ( ), Hong-Kong | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | INT = 26 CON = 20 | 11–14 yo (INT = 13.35 yo; CON = 13.15 yo); 65% lived in public housing; 90% of the INT group had income < HK$20,000 | Adolescent’s anxiety | Student | 120 min/tx; 8 sessions | Tier 2 | Experimental group had a significant increase in cases falling back into the normal range of the HADS-A scale, and a significant decrease in number of probable anxiety cases while changes in number of anxiety cases were insignificant for the control group for all categories |

| Wong et al. ( ), Hong-Kong | Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | INT = 42 CON = 36 | 26–58 ( = 47.38, = 44.06); about 50% had monthly family income btw HK$10,001-HK$30,000 | Parental cognitions; self-efficacy, & mental health | Parent | 180 min/tx; 10 sessions; 5 groups | Tier 2 | Significant group by time interactions for most primary and secondary outcome variables indicating significantly greater improvement in experimental than control group; experimental group also showed greater improvement at post-test and 3-month follow-up |

| Young et al. ( ), USA | Perfect Attendance Wins Stuff | 41 | 47.1% Hispanic, 35.8% White, 7.2% Black, 7.1% Asian, 1.3% Multi-racial, 15.4% special education, 11.3% English-language learner, and 53.3% had FRPL | absenteeism | Student | Daily check-in, monthly celebration, weekly breakfast, phone calls home, referrals to community services, parent meetings, & home-visits; one year | Tier 3 | significant effect in attendance percentage between time periods; post hoc tests revealed that attendance increased by an average of 12.2% after one month and remained steady at months 2 and 3 |

Note. Bx behavior, ed education, yo years old, yr = year. tx treatment, w with, T treatment group, C control group, INT intervention, CON control, FRPL Free/Reduced prices lunch, IEP Individualized education program, CBT cognitive behavior therapy, BST Behavior skill training, HADS-A Hospital anxiety and depression scale

Characteristics of the Included Research Studies

| Authors (year), Country/Region | Study aims | Design | Manualized | Credential | Fidelity control | Service type | Practitioner | Quality assessment | Outcomes (Measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acuna et al. ( ), USA | Examine feasibility and impact of a short-term school-based parenting intervention for children’s disruptive behaviors | Pre-post-test | Yes | Master’s-level licensed school social worker/trainee | Training of at least 8 h by program creator | EBP | SSW | Strong | Positive child behavior (Mental Health/Behavior Instrument) |

| Al-Rasheed et al. ( ), Kuwait | Pilot test of new universal school-based group prevention program to promote healthy attitudes and behaviors among high school students in Kuwait | Pre-post-test | Yes | NR | 3 h training and workshop sessions for 5 days; ongoing evaluation | EPB | SSW & school psychologist | Strong | Resilience (The Resilience Skills Questionnaire) |

| Chupp and Boes ( ), USA | Examine efficacy of small group social skills lessons with elementary students based on a skills learning curriculum | Pre-post-test | NR | NR | Training (PI and SSW trained by curriculum creator) | EBP | SSW & school counselor | Weak | Social skills (Student Knowledge Survey; SBC; teacher’s interview); GPA |

| Elsherbiny et al. ( ), Egypt | Test effectiveness of a preventive school social work program targeting school children and their parents to reduce school refusal | Experimental | NR | NR | Supervision | Long-term psycho-social intervention | SSW & school psychologist | Strong | School refusal (SRAS-C-R; SRAS-P-R) |

| Ervin et al. ( ), USA | Assess effectiveness of combining behavior skill training with observational learning to train students to appropriately respond to disruptive bxs in the classroom | SS-multiple baselines | No | NR | IOA | Short-term psycho-social intervention | SSW & teacher | Weak | Behavior skills (Verbal Assessment; Classroom Observations) |

| Fein et al. ( ), USA | Study implementation of pilot Family Resilience Curriculum for Parents (FRC-P) in terms of functionality, feasibility, and acceptability | Pre-post-test | Yes | Master’s-level social worker/trainee | Training at least 12 h; supervision (ongoing support from lead trainer) | EBP | SSW | Strong | Resilience (CD-RISC); family functioning (FAD-GFS); parent stress (PSS) |

| Ijadi-Maghsoodi et al. ( ), USA | Test feasibility and efficacy of adapted trauma-informed curriculum in building resilience skills among urban, ethnically diverse students | Pre-post | Partially | Licensed school social worker | Training (one day); SSWs were certified as curriculum providers | EBP | SSW | Strong | PTSD (PC-PTSD); Internal Assets & School Support (RYDM; CHKS); Student's Perception Scale |

| Kataoka et al. ( ), USA | Pilot test effectiveness of a school-based trauma-informed CBT group intervention for Latino immigrant students in addressing trauma and depressive symptoms due to community violence exposure | Quasi-Experimental | Yes | Master’s-level social worker/trainee | Training (16 h); ongoing supervision (1 h/wk) | Short-term psycho-social intervention | SSW | Strong | Community violence (modified Life Events Scale); PTSD symptoms (CPSS); depressive symptoms (CDI) [in Spanish] |

| Kelly and Bluestone-Miller ( ), USA | Preliminarily test WOWW program as way for school social workers to help teachers positively influence students’ self-perception | Pre-post-test | Partially | NR | NR | EBP | SSW | Weak | Program effectiveness (Researcher-designed Likert Scale) |

| Magnano ( ), USA | Test effectiveness of a school-based case management intervention with articulated behavioral and academic outcomes of children placed in segregated settings due to emotional and behavioral disabilities | Quasi-Experimental, partial cross-over | Partially | NR | NR | Case management | SSW | Moderate | STAR Reading, Literacy, and Math scores; anti-social and aggressive behaviors (TRF; BRIC) |

| Newsome ( ), USA | Test efficacy of SFBT group counseling program to enhance the behavioral, social, and academic competencies of students at-risk of school failure | Pre-post-test | Yes | Master’s-level social worker/trainee | Training (a summer quarter); Supervision (1 h preceding each tx) | Short-term psycho-social intervention | SSW | Moderate | Homework completion (HPC); classroom behaviors and social skills (BERS; SSRS) |

| Newsome et al. ( ), USA | Examine impact of school social work services on reducing risk factors related to truancy and absenteeism in urban secondary school settings | Quasi-Experimental | NA | NR | NA | General school social work services | SSW | Strong | Risk factors for truancy (SSP); Unexcused truancy records from school district |

| Phillips ( ), USA | Test effectiveness of a school-based CBT curriculum for adolescents at risk for depression to improve emotional well-being | Quasi-Experimental | Partially | Master’s-level social worker/trainee | NR | Short-term psycho-social intervention | SSW | Moderate | Depression (BDI) |

| Sadzaglishvili et al. ( ), country of Georgia | Test how an intensive school social work intervention may improve school culture in two highly vulnerable schools in Georgia, and the impact on children with special education needs | Pre-post-test | Partially | NR | NR | General social work services | SSW | Weak | School culture (self-report & case number) |

| Thompson and Webber ( ), USA | Pilot test a cognitive–behavioral intervention with special-ed middle school students on realigning rule perceptions at school and improve student behaviors by strengthening teacher–student relationship | SS-AB | Yes | NR | NR | EBP | SSW & teacher | Weak | Students’ behaviors (teachers’ rating) |

| Wong et al. ( ), Hong-Kong | Examine effects of culturally attuned group CBT on anxiety symptoms and enhancing personal growth among adolescents at risk of anxiety disorders in Hong Kong | Quasi-Experimental | Yes | Licensed school social worker | Training (by experienced CBT therapists; videotape critiques); Supervision (throughout project) | Short-term psycho-social intervention | SSW | Strong | Anxiety (HADS-A subscale; Spence Children's Anxiety Scale); dysfunctional beliefs (DAS); personal growth (PGIS-II) |