An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Public Health

- v.106(6); Jun 2016

The Role of Labor Unions in Creating Working Conditions That Promote Public Health

All authors contributed to the conceptual development of the study. C. A. Paras and H. Greenwich coordinated data collection. All authors collaborated on study design. J. Hagedorn was the primary author of data analysis and interpretation and drafted the article with significant support from A. Hagopian and H. Greenwich. All authors revised content and approved the final version to be published.

We sought to portray how collective bargaining contracts promote public health, beyond their known effect on individual, family, and community well-being. In November 2014, we created an abstraction tool to identify health-related elements in 16 union contracts from industries in the Pacific Northwest. After enumerating the contract-protected benefits and working conditions, we interviewed union organizers and members to learn how these promoted health. Labor union contracts create higher wage and benefit standards, working hours limits, workplace hazards protections, and other factors. Unions also promote well-being by encouraging democratic participation and a sense of community among workers. Labor union contracts are largely underutilized, but a potentially fertile ground for public health innovation. Public health practitioners and labor unions would benefit by partnering to create sophisticated contracts to address social determinants of health.

Labor unions improve conditions for workers in ways that promote individual, family, and community well-being, yet the relationship between public health and organized labor is not fully developed. 1 Despite historic and current efforts by labor unions to improve conditions for workers, public health institutions have rarely sought out labor as a partner. 2,3

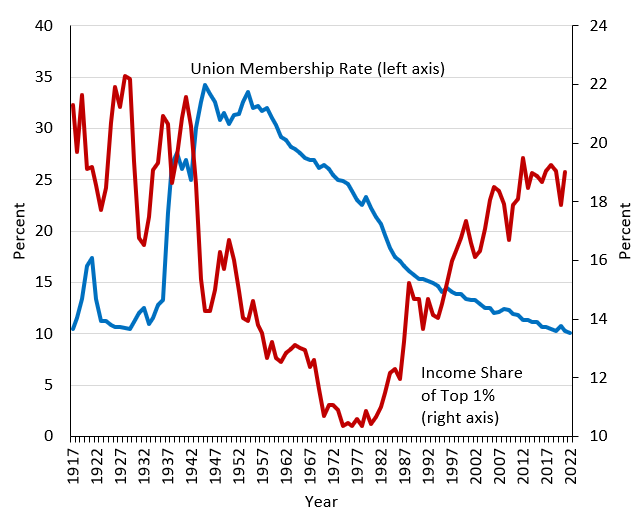

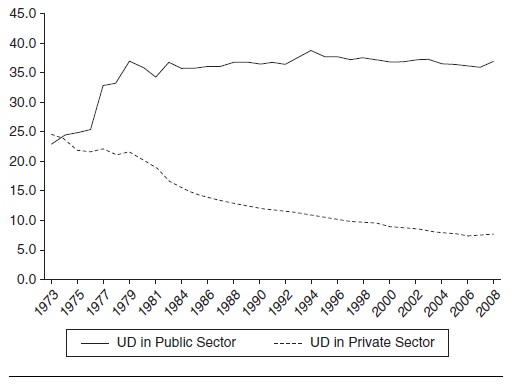

In 2014, American labor union density was at a 99-year low. 4 Low union density has left workers vulnerable to reduced health and safety standards, and has fed the decline in public perception of the value of unions. 5,6 Unions have helped to codify economic equity in the workplace, and the decline of their power is associated with the greatest level of economic inequity in our nation’s history. 5,7–9 The erosion of union density has undermined the role of organized labor as a societal power equalizer. 8

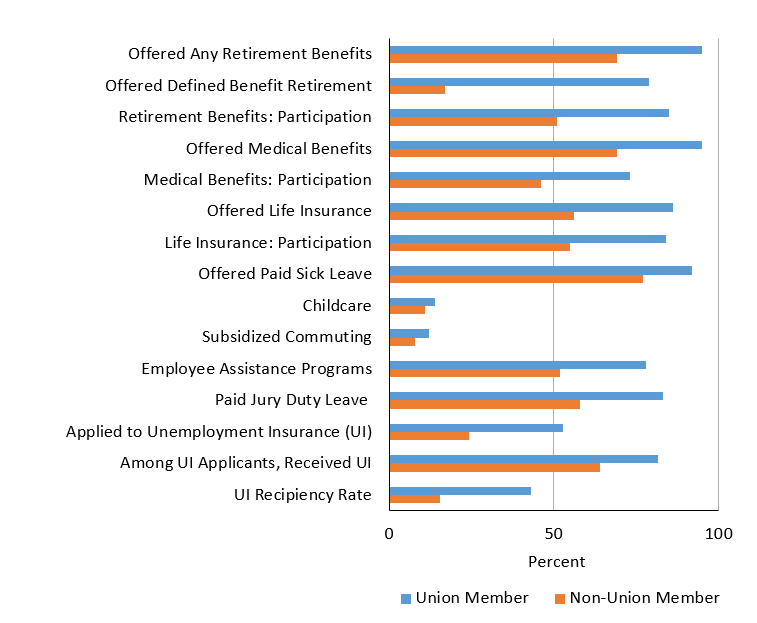

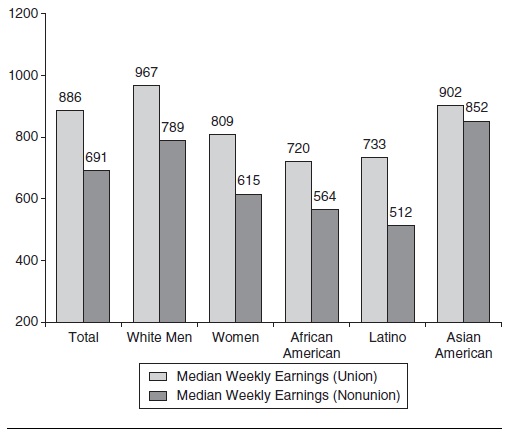

Income is a primary social determinant of health, associated with the living environment and overall well-being of individuals or families. 10–16 Income is higher in union jobs than in nonunion jobs, especially for lower-skilled workers. 5,16–18 Retirement or pension plans create the financial stability to promote health into old age. 19 Union employees are more likely to have a retirement or pension plan and are more likely to participate in a retirement plan sponsored by their employer than employees who are not members of a union. 20,21

Researchers have established a correlation between unionized work and a higher percentage of pay coming in the form of highly valued benefits. 22,23 Unions have historically been involved in creating healthy and safe workplaces, advocating regulations that are monitored and enforced by public health entities such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 3,24

Autonomy and control over one’s life are associated with positive health outcomes, 25–28 and social support in the work environment enhances psychological and physical health. 29,30 Conversely, perceived job insecurity is associated with risk factors for poor health outcomes, contributing to racial and socioeconomic health disparities. 31–35 Unions help members gain control over their scheduling 36,37 and job security, 38 and union membership is associated with increased democratic participation. 39

The American Public Health Association is on record supporting the role of labor unions in promoting healthy working conditions, health and safety programs, health insurance, and democratic participation. 40–42 The decline of union density may undermine public health in the United States, making this a critical time for public health to actively support labor unions.

Previous researchers published in AJPH have highlighted the links between unions, working conditions, and public health, but called for more research to establish the precise mechanism of the relationships. Malinowski et al. proposed the social–ecological model as theoretical framework for connecting public health and labor organizing. 43 Both labor unions and public health organizations intervene in the conditions that make people healthy through individual life choices, and social and community networks, as well as general socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental conditions. Malinowski et al. illustrates the overlapping interests of labor unions and public health and how their lack of coordination has created barriers for both institutions.

One mechanism unions use to promote public health is the union contract. These are legally binding, durable over a designated time, and specific. They are durable because they cannot be unilaterally changed, and contracts that follow often build on the progress of previous negotiations. Even after a contract expires, federal labor law provides a process and momentum for the negotiation of a new one.

We hypothesized that union contracts promote the health status of workers. If true, contracts have untapped potential for public health professionals working to improve the health of individuals and communities.

We designed this cross-sectional, mixed-methods study to identify specific mechanisms that link labor union representation and public health outcomes. Our primary unit of analysis was the negotiated contract between management and labor for a variety of unions in the Puget Sound region of Washington State. We supplemented a textual analysis of the contracts with interviews of union organizers and union members.

In the summer of 2014, we established a partnership between a University of Washington master of public health graduate student (J. H.) and Puget Sound Sage, a nonprofit organization that promotes alignment among labor, environmental, and community interests to “grow communities where all families thrive.” We identified 6 union locals in the region that represented hotel workers, truck drivers, home-care workers, construction workers, child-care workers, office workers, and grocery store workers. Sage held preexisting relationships with these unions, either through representation on Sage’s board or some other form of collaboration, which greatly facilitated our data requests. For each union, we obtained 1 or more labor contracts, for a total of 16 contracts ( Table 1 ).

TABLE 1—

Union Contracts Dated 2010 to 2014 Analyzed for Mechanisms That Advance Health of Employees and Their Families: Pacific Northwest, United States

| Contract ID No. | Union | Employer | Workforce | Date of Contract | No. of Pages |

| 242.1 | Washington & Northern Idaho District Council of Laborers | Associated General Contractor of Washington | Construction and demolition | June 21, 2012 | 36 |

| 242.2 | Washington & Northern Idaho District Council of Laborers | Various, unnamed | Construction and demolition | 2013–2016 | 32 |

| 242.3 | Seattle/King County Building and Construction Trades Council | Seattle School District | Construction and demolition | March 23, 2010 | 30 |

| 775.1 | SEIU Healthcare 775NW | Addus Healthcare—Washington | Home health care | May 8, 2014 | 48 |

| 775.2 | SEIU Healthcare 775NW | Amicable Healthcare, Chesterfield Health Services, Concerned Citizens, Korean Women’s Association | Home health care | April 8, 2014 | 66 |

| 775.3 | SEIU Healthcare 775NW | State of Washington | Home health care | July 1, 2013 | 35 |

| 775.4 | SEIU Healthcare 775NW | Res-Care Washington | Home health care | April 4, 2014 | 49 |

| 775.5 | SEIU Healthcare 775NW | Catholic Community Services | Home health care | July 1, 2014 | 39 |

| 925.1 | Childcare Guild of Local 925, SEIU | Association of Childcare Employers | Child care | September 1, 2011 | 40 |

| 925.2 | SEIU Local 925 | Community Development Institute Head Start | Child care | October 27, 2013 | 17 |

| 117.1 | Teamster Local No. 117 | Golden States Food Transportation | Transportation | November 14, 2014 | 38 |

| 117.2 | Teamster Local No. 117 | King County | Professional and technical and administrative support | October 30, 2012 | 102 |

| 117.3 | Teamster Local No. 118 | Safeway Inc | Warehouse | July 10, 2011 | 45 |

| 21.1 | UFCW Local 21 | Allied Employers Inc Grocery | Grocery stores | May 5, 2013 | 71 |

| 21.2 | UFCW Local 22 | Allied Employers Inc Meat Dealers | Grocery stores | May 6, 2013 | 54 |

| 8.1 | UNITE HERE Local 8 | The Westin Seattle Hotel | Hospitality | July 1, 2013 | 38 |

Note. SEIU = Service Employees International Union; UFCW = United Food and Commercial Workers; UNITE HERE = Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees and Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union. Data for this article came from the 16 union contracts analyzed for their health-related factors, obtained from 5 Puget Sound labor unions in 2014.

Through a comprehensive literature review of the work-related determinants of health, we identified health-related factors that theoretically might be addressed in a labor contract. We then created a spreadsheet abstracting specific language from each contract by each of the theoretical constructs, and, through an iterative process, settled on 12 health factors. For example, we created a cell for “fair and predictable pay increases,” into which the following Service Employees International Union (SEIU) 775 contract language was placed:

Employees who complete advanced training beyond the training required to receive a valid Home Care Aide certification (as set forth in the Training Partnership curriculum) shall be paid an additional twenty-five cents ($0.25) per hour differential to his/her regular hourly wage rate.

After creating the 12 large categories, we further analyzed the contract language in our spreadsheet to generate 34 subcategories ( Table 2 ). We suggest that these 34 factors, taken together, comprise the specific mechanisms by which labor contract language supports public health. We determined whether the indicators were present in each contract (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org ) and Table 2 reports what proportion of contracts contained language on each of the 34 factors. When “all” contracts have an indicator, this means each of the 16 contracts contains health-protecting language on the topic. “Almost all” refers to 14 or 15 contracts, “most” means 7 to 13 contracts, and “some” refers to 5 or 6 contracts.

TABLE 2—

Factors That Advance Health of Employees Theorized to be Found in Union Contracts, and Their Presence in 16 Union Contracts Dated 2010 to 2014: Pacific Northwest, United States

| Factors and Indicators | Indicator Present in Contracts |

| Income | |

| Wages | All |

| Employer-paid travel | Most |

| Employer-paid trainings | Most |

| Employer-paid materials | Some |

| Overtime | Almost all |

| Show-up pay | Some |

| Predictable and fair increases in wages | |

| Wage increases based on qualifications or duties | All |

| Predictable chronological wage increases | All |

| Transparency of paycheck calculations | Some |

| Old age security: retirement and pension | Almost all |

| Paid time off | |

| Holidays | Some |

| Lunch | Few |

| Rest periods | Most |

| Sick leave (separate from annual leave) | Some |

| Annual leave or vacation | Most |

| Bereavement | Most |

| Access to health care: health care insurance | All |

| Health information communication | |

| Health and safety regulations | Most |

| Bulletin board to communicate union information | Most |

| Union access to the worksite | Most |

| Training and mentorship | |

| Provide employer-paid training | Almost all |

| Support mentorship among employees | Some |

| Workplace safety culture | |

| Protective clothing and equipment provided and maintained by employer | Most |

| Right to light duty work after injury | Few |

| Required to report injuries and hazards | Most |

| Job security | |

| Leave of absence for personal or family reasons | Most |

| Nondiscrimination laws reinforced | Almost all |

| Procedure for grievances | All |

| Support in engaging with management | |

| Labor relations or management committee | Most |

| Right to union representation during meetings with managers | Almost all |

| Fair and predictable scheduling | |

| Mandatory notice of schedule changes | Most |

| Shift schedule parameters, including time between shifts or minimum shift length | Most |

| Democratic participation | |

| Full pay while on jury duty | Some |

| Opportunity to participate in lobby day or political work while paid by company | Most |

Note. All = 16 contracts; almost all = 14 or 15 contracts; most = 7 to 13 contracts; some = 5 or 6 contracts. Data for this article came from the 16 union contracts analyzed for their health-related factors, obtained from 5 Puget Sound labor unions in 2014.

To supplement our analysis, we interviewed 1 member from each of the 6 unions covered by a contract in our analysis, as well as 7 union organizers representing those members ( Table 3 ). In 1-hour interviews with union organizers, we explored how contract language is aligned with public health outcomes through questions about their job and the role of the union. We asked workers about the dangers in their job and if or how the union helps to protect them, we asked about safety and health problems and the union’s role in addressing those, and we asked about conflict in the workplace and whether the union helps to resolve issues. We also asked workers to compare any workplaces they had experienced without a union to their current workplace.

TABLE 3—

Interviews Conducted With Union Members and Organizers: Pacific Northwest, United States, 2015

| Union | Organizer Job Title | Employee Job Title |

| Teamsters 117 | Director of organizing and strategic campaigns | Warehouse employee |

| SEIU 775 | Organizer | Home-care worker |

| SEIU 925 | Two organizers | Home child-care worker |

| UFCW 21 | Organizer | Grocery store worker |

| UNITE HERE 8 | Director of strategic affairs | Housekeeper |

| Laborers 242 | Business manager | Construction worker |

Note. SEIU = Service Employees International Union; UFCW = United Food and Commercial Workers; UNITE HERE = Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees and Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union. Interviews conducted between January and April 2015 with Puget Sound–area labor union staff and industry employees to supplement our understanding of the role of labor union contracts in protecting employee health.

Each union assisted in identifying a covered member for us to interview. Usually, an e-mail was sent to members the organizer thought may be interested in the study. These members were compensated $50 for their 1-hour interviews, with funds provided by Sage. In interviews with members, we asked about the most dangerous or hazardous aspects of their jobs and how the union helps to mitigate those risks, as well as other benefits of being a union member.

There is consistency among contracts negotiated by same union (Table A). Contracts with public sector entities (such as 925.2, Headstart Program; 775.3, State of Washington; and 242.3, Seattle School District) have fewer provisions that contribute to health in their contracts.

Compensation

We created compensation indicators illustrating how the wages of employees are augmented when employers are prohibited from externalizing their costs by having employees pay for work-related travel, training, and materials.

All contracts include minimum wages by employee classifications, including overtime. Higher income and overtime wage gains are built over time. Income is augmented when employers are directed to cover specific work-related expenses. Most contracts compensate employees for the cost of traveling between work sites and the cost (or partial costs) of trainings. Some contracts also provide money for materials, such as United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) contract 21.2, which states, “The Employer shall bear the expense of furnishing and laundering aprons, shop coats, and smocks, for all employees under this Agreement.” Other contracts ensure employers will not call in more employees than needed and then send them home; they do this by creating a “show-up pay” provision. Laborers’ contract 242.1 describes this as

Employees reporting for work and not put to work shall receive two hours pay at the regular straight time rate, unless inclement weather conditions prohibits work, or notified not to report at the end of the previous shift or two hours prior to the start of a shift.

One child-care worker explained how union advocacy has increased the supplement provided by the state for the extra challenges posed by caring for low-income children, saying “For family childcare workers, who are often very underpaid for the amount of hours that they work, we have seen over the last 8 years, a 22% increase in our subsidized childcare. That is big!” Another worker from Teamsters Local 117 said, “I know there are guys doing the same job [in nonunion warehouses] making $10 less an hour.”

Predictable and fair increases.

All contracts provide wage increases on the basis of qualifications, duties, and duration of time at the company. Workers can increase their wages by increasing their training or by assuming additional responsibilities, including mentoring peers, accepting clients with higher needs, working less-desirable hours, doing more physically strenuous labor, or taking on leadership roles within a working group. Some contracts require transparency in paycheck calculations, mandating employers to itemize hours, overtime, and sometimes the cumulative number of sick days or holidays used, allowing employees to check the calculations.

An organizer with UFCW (grocery) Local 21 explained, “[employers] see experience as a cost and not a driver of sales.” The organizer explained that without the contracts, employers would not raise wages over time, especially for jobs viewed as requiring fewer technical skills.

Retirement and pension.

Almost all contracts include retirement or pensions. Most of these are set up in the form of trusts, with a collaborative process for management and employees to manage money and benefits. This language usually exists in a separate document referred to by the contract.

A retired member of Laborers Local 242 described how he was able to adjust his hours to make the money he needed, but also be able to retire comfortably because of his savings and pension. He explained, “I retired early. I wanted to do things that I wasn’t able to do when I was younger because I had to support the family.”

We created indicators to track evidence-based factors related to physical and psychological health, including time off and access to health care. 44–46

Paid time off.

Most contracts include the indicators of paid annual leave, paid rest periods, and bereavement leave. The amount of annual leave varies, but usually increases as the employee gains seniority. Paid rest periods are usually defined as short, 15- to 30-minute periods. Bereavement leave to attend a funeral or grieve a loss can be used for specific family members in some contracts, whereas others allow its use for a broader range of relationships.

Health care coverage.

Health insurance is included in all contracts. We did not attempt to distinguish among contracts with regard to affordability, comprehensiveness, or number of dependents covered because health care is managed by trusts, much like retirement or pension benefits.

All of the organizers discussed the benefits of union health coverage. An organizer from UFCW Local 21 explained,

Members have consistently traded wages for health benefits. They have been willing to have slowed wage increases in order to maintain their strong health benefits over and over and over. What I see if I go into a [unionized grocery] I see a much higher percentage of people who have children who rely on their health insurance.

Health and Safety

Most contracts guide how health and safety regulations are communicated to workers, including written and verbal forms.

Health and safety information.

Although most contracts include health and safety information, they are usually not very specific. For example, Teamsters’ contract 117.1, states,

[T]he Company may require the use of safety devices and safeguards and shall adopt and use practices, means, methods, operations and processes which are adequate to render such employment and place of employment safe and shall do all things necessary to protect the life and safety of all employees.

Most contracts also include a provision allowing the union to post and maintain a bulletin board to communicate information to members. Contracts also generally ensure union representative access to the worksite. For example, SEIU contract 925.2 (child-care workers) states,

The designated Stewards or Chief Stewards shall have access to the premises of [Community Development Institute Head Start] to carry out their duties subject to permission being granted in advance.

Training and mentorship.

Almost all contracts explicitly require training. Some contracts include compensation for providing mentorship to encourage more senior employees to provide support to new employees or employees taking on new roles.

One organizer from Laborers Local 242 described how important it is for workers to know how to do their work safely, for themselves, coworkers, workplace clients, and their own families. For example, a hospital demolition crew should know how to contain particulate matter to avoid contaminating patients or bringing it home to expose their children. The organizer said training ensures “If you hire a [union] laborer, you know you’re going to get the best product. We have the safest workforce. We’re the most experienced.”

Promotion of a culture of workplace safety.

Most contracts detail the employer’s responsibility to provide and maintain protective clothing and equipment. Most contracts also protect bringing a safety hazard to the attention of a supervisor. For example, SEIU contract 775.5 states, “the employee will immediately report to their Employer any working condition the employee believes threatens or endangers the health or safety of the employee or client.” Some contracts have a provision allowing workers who return to work after an injury to receive less strenuous work, or “light duty.” Both Laborers’ contracts contain this provision, an important provision for physically demanding work.

Promoting Individual, Family, and Community Well-Being

We analyzed indicators that measure the role of contracts in reinforcing social support in the work environment.

Job protections and security.

All contracts contain specific and detailed grievance procedures, the process of reporting, mediating, and resolving conflicts in the workplace. Almost all contracts confirm the right to have a union representative present during meetings with managers. Some contracts, such as SEIU 775.1, make it the employer’s responsibility to make this known:

In any case where a home care aide is the subject of a written formal warning the Employer will notify the home care aide of the purpose of the meeting and their option to have a local union representative present when the meeting is scheduled.

Most contracts also establish or maintain a labor relations or management committee. Although the language about this committee may differ, the purpose of the group is to create a space in which workers and employers can negotiate problems that arise between negotiations of new contracts.

Almost all contracts contain a commitment to creating a discrimination-free workplace. Most contracts create the opportunity for a worker to take a leave of absence without sacrificing seniority for maternity leave, further education, religious holidays (e.g., Yom Kippur, Easter), military leave (for the employee or spouse), domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking, or union activity.

Fair and predictable scheduling.

Most contracts include a mandatory notice of schedule changes. As UFCW contract 21.1 explains,

The Employer recognizes the desirability of giving his employees as much notice as possible in the planning of their weekly schedules of work and, accordingly, agrees to post a work schedule.

Some contracts specify the amount of notice required for a schedule change. Those that change regularly may require posting the week before. Most contracts also include an amount of time required between shifts or minimum shift length, and how employees can request additional hours.

Democratic participation.

Most contracts provide employees the opportunity to participate in union-sponsored legislative “lobby days,” or to engage in political work while being paid by their employer. As SEIU contract 925.1 explains,

As part of our ongoing campaign to provide the highest possible standard of childcare and engage in an ongoing public campaign to explain the direct relationship between funding and the quality of care, it is in each party’s best interest to provide reasonable opportunity for members of the bargaining unit to participate in these efforts.

Contracts require all union members to pay dues. Some contracts also specify how a union member can contribute to a political action fund, which generates revenue to represent employee interests in the policy arena. One home health worker explained that she is getting more involved in politics and collective bargaining because of union engagement, saying,

I like belonging to a union that believes in me as an individual and as a caregiver. They’re behind us every step of the way. They help us to look at things that otherwise we might not be aware of, like state legislation and contract negotiation.

Public health practitioners have not typically viewed unions as partners in promoting public health, nor have they explored contract negotiations as a way to ensure health protections. We suggest that this is a missed opportunity. Our findings demonstrate that union contract language advances many of the social determinants of health, including income, security, time off, access to health care, workplace safety culture, training and mentorship, predictable scheduling to ensure time with friends and family, democratic participation, and engagement with management. This article provides a provisional framework to explore further the factors that create public health opportunities in union contracts.

We examined selected union contracts in the Pacific Northwest, which may not be generalizable. Our sample included only those unions in a relationship with Puget Sound Sage, perhaps suggesting unique perspectives or priorities. We compared our sampled unions to those in the King County Labor Council, however, and although there were some industries not represented (e.g., aerospace, teachers, assembly line workers), we believe the types of workplaces in our sample are reasonably representative of the landscape of unions in the county. We did not attempt to incorporate the views of the respective employers on these contracts.

The language in the contracts we reviewed included rights won at the bargaining table along with restatements of existing city, state, and federal laws. For example, leave without pay contract provisions match the Washington State Family Leave Act. When union negotiators include these indicators in contracts, they generate awareness of health-promoting regulations and protections. Laws and policies can change, but a union contract can only change if the union agrees to renegotiate the contract or if the contract has expired. Union stewards learn the details about a contract, but cannot be expected to know the full range of laws from a variety of jurisdictions. The contract works to reinforce the knowledge of workers and their representatives. Although it was beyond the scope of our study, contracts must be enforced to actualize their health-related benefits. Effective enforcement mechanisms for contracts are also potentially beneficial to public health officials. 22,27,47

We identified many contract indicators that advance health for more than just employees. Unions generate higher prevailing wages in a community. 7,48 Unions invest in campaigns to raise wages for both union and nonunion workers, such as the $15 hourly wage initiative in SeaTac, Washington. 49,50 A safer environment for home-care and child-care workers creates safer environments for the people they serve. A culture of safety on construction sites ensures that environmental hazards are minimized for people who live nearby. Parents earning a living wage can avoid taking second jobs and use the time to engage in children’s schools or community councils. A healthy and happy workforce is more productive and less likely to leave a job, reducing the cost of turnover and absenteeism for employers. In spite of the many benefits unions confer to workplaces and communities, union membership is now limited to only 1 in 10 American employees. 4

The decline of labor union density is related to both the rise of corporate power and to mistakes made by labor. 1 After a period of radical inclusivity and left-leaning solidarity with broader political movements, unions moved toward racism and red-baiting in the 1950s, undermining their strength. 51 Unions are still working to reduce racial and gender disproportionality within their leadership. 52

Despite historical shortcomings, labor unions (and their contracts) offer an underutilized opportunity for public health innovation. As illustrated by Malinowski et al., public health practitioners often work in the “outer” layers of the social–ecological model, promoting environments that can better shape population health. 43 This is also true of labor unions. Public health practitioners could help unions negotiate more sophisticated contracts to address the social determinants of health. Public health practitioners could also work with policymakers to heighten awareness of how unions might help mitigate the forces that threaten health in the workplace and beyond. Supporting progressive labor union contracts is public health work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge a grant from the University of Washington Harry Bridges Labor Center that made this work possible. Also, thank you to Puget Sound Sage for providing the compensation for labor union members who were interviewed.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Ethical approval for the project was provided by the University of Washington institutional review board, approval 48520-EJ.

- Advanced search

Advanced Search

Unions, Worker Voice, and Management Practices: Implications for a High-Productivity, High-Wage Economy

- Find this author on Google Scholar

- Find this author on PubMed

- Search for this author on this site

- Figures & Data

- Info & Metrics

This article uses the metaphor of a social contract to review the evolution of American unions and their effects— especially in the variations in their quality—on firm employment strategies and performance, takes stock of the current state of unions and alternative forms of worker voice that have emerged in recent years, and discusses implications for the future of labor and employment policies. The key policy implication is that fundamental, not incremental, changes in labor policy will be needed if the range of worker voice and representation processes workers want and the economy needs are to grow to a scale large enough to close existing voice gaps and contribute to building a new productivity- and wage-enhancing social contract.

- collective bargaining

- productivity

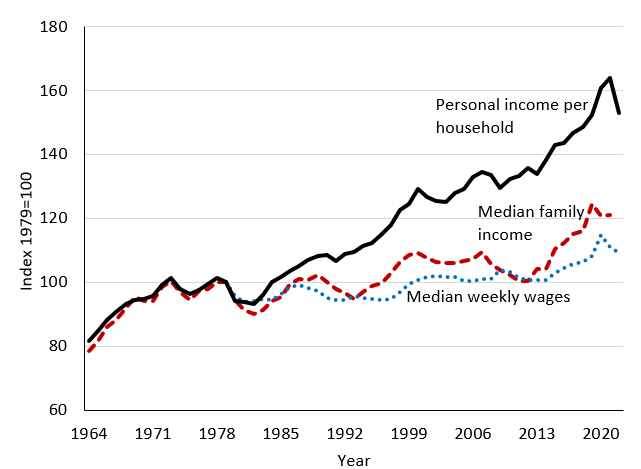

Throughout most of the twentieth century, unions and collective bargaining were powerful mechanisms for improving wages and other aspects of job quality for both union-represented and non-union workers. These improvements negotiated in collective bargaining in turn put pressure on employers to find ways to increase productivity, what Sumner Slichter, James Healy, and E. Robert Livernash ( 1960 ) labeled the “shock effect“ of unions on management practices. These management adjustments could range from or include a mix of investments in new technology, workforce training or other personnel management practices, product upgrading, or other productivity enhancing actions. This dynamic process served as a precursor to what would later be labeled high-road management strategies (Kochan and Osterman 1994 ; Osterman 2018 ). Pattern bargaining, and the threat effects of union organizing of non-union firms, spread wage increases and other negotiated improvements in employment practices across establishments and firms within regions and industries (Levinson 1960 ; Budd 1992 ) and contributed to reducing income inequality (Freeman 1980 ; DiNardo, Fortin, and Lemieux 1996 ; Western and Rosenfeld 2011 ; Farber et al. 2018 ). In doing so, collective bargaining played a significant role in generating tandem increases in compensation and productivity, an indicator of what some of us have labeled the post–World War II social contract (Kochan 2000 ).

In recent decades, however, declining union membership and bargaining power reduced the role of unions as both a source of wage growth and as a spur to high-road managerial practices. The postwar social contract’s tandem movement of productivity and wages broke down and has yet to be replaced with other ways of supporting steady wage growth or motivating employers to compete on the basis of high productivity and high wages. As a result, the past four decades have witnessed significant growth in income inequality and a number of its associated consequences, such as increased worker insecurity, resistance to trade and immigration, and growing political polarization between the perceived winners and losers from globalization and changing technologies.

This leaves policymakers who want to support a high-productivity, high-wage economy and society with a set of important but difficult questions: What can be done to build a new productivity and wage-enhancing social contract suited to the contemporary and future economy and workforce? Are new policies needed to rebuild unions and worker bargaining power in ways that work in today’s economy? And, given the difficulties associated with reversing long-term union decline, what additional policy options might be needed to create good jobs for all segments of the workforce?

Our bottom line is that fundamental rather than incremental changes in labor and employment policies will be needed to build a new social contract that reverses recent trends and lays the foundation for a new social contract.

- COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AND THE POSTWAR SOCIAL CONTRACT

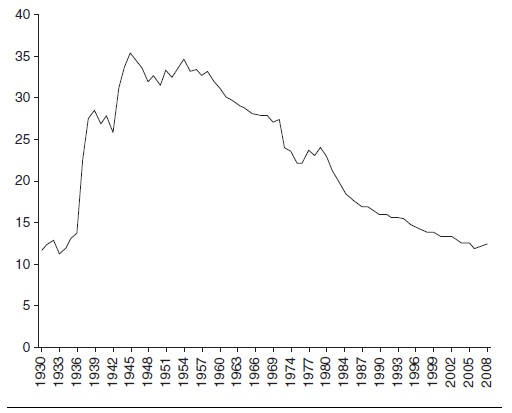

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935, along with the other three pillars of the New Deal labor legislation (unemployment insurance, social security and disability insurance, and minimum wages) laid the foundation for the social contract that emerged in the decades following World War II. The main effect of the NLRA was to provide long-term stability to union membership—once a union was recognized, it could not be ignored or broken by employers unless a majority of workers voted to decertify it. Union density in the private sector grew from approximately 11 percent in 1930 to a peak of 35 percent in 1945. Unions gained further legitimacy during World War II through participation in the National War Labor Board and its actions to endorse practices such as grievance arbitration, cross-firm wage comparisons within industries and occupations, and benefits such as paid health insurance (National War Labor Board 1946 ). The growth and strength of unions led President Truman to call a national labor-management conference in 1945 seeking a postwar accord for guiding the future of labor-management relations. That effort failed to achieve consensus largely because of the inability of labor and management representatives to agree on the extent to which unions should be able to have a voice in management practices (Chamberlain and Kuhn 1965 , 85). As a result, unions and employers were left to their own devices to develop the norms and practices that would shape collective bargaining in the postwar era.

The latter half of the 1940s was a tumultuous and pivotal time for collective bargaining. Pent-up demands for wage increases following the end of wartime wage restraints led to numerous strikes; a higher percentage (1.4 percent) of the workforce’s estimated total work hours (U.S. Department of Labor 1947 ) were lost to strike activity in 1946 than any year since. Major debates over the extent of union influence on management decisions dominated bargaining in the large industrial unions. Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers (UAW), pressed auto firms to give the union a voice in product pricing in return for moderating wage demands. This was vigorously resisted by General Motors (GM) and other auto firms but also discouraged by union leaders in other industries who favored a more conventional arms-length relationship that would leave management free to make business decisions and unions free to negotiate for the best wage, benefit, and working conditions deal possible. This debate was essentially resolved when, in two rounds of negotiations between 1948 and 1950, GM management proposed and the UAW accepted a new wage norm that would eventually spread across the auto industry and to unionized firms in other industries but excluded any role for unions in wider business decision making. Later labeled the Treaty of Detroit, this principle called for wages to increase annually to keep up with increases in the cost of living and to provide an “annual improvement factor” of 2 percent to share the growth in aggregate productivity (Lichtenstein 1995 , 279). Once GM agreed to this basic formula, the UAW then insisted it be followed in negotiations with Ford, with Chrysler, and to varying degrees throughout the unionized auto supply industry. Unions in other industries with high degrees of union density adopted similar practices. This process of diffusing similar wage increases within large unionized firms and within industries through collective bargaining became known as pattern bargaining. It became an instrument for diffusing this wage-productivity norm broadly enough across the economy to achieve the tandem upward movement in both indicators from the mid-1940s to around 1980 (see figure 1 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Growth in Productivity and in Average Hourly Compensation

Source: Economic Policy Institute 2017 .

- UNION WAGE EFFECTS DURING THE SOCIAL CONTRACT ERA

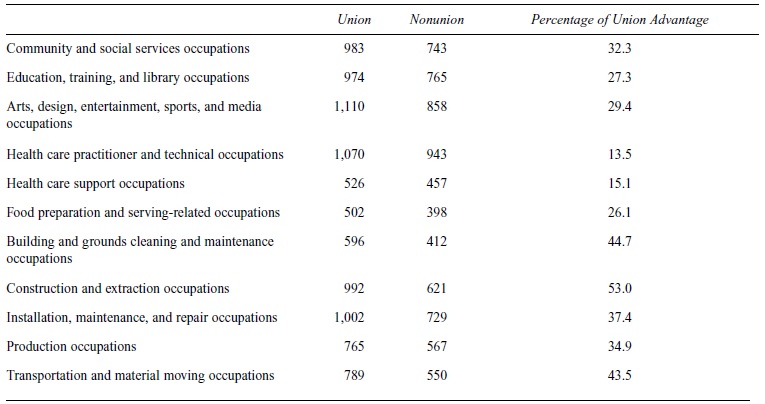

Given the growing importance of unions in the post–World War II expansion, it is not surprising that interest also grew among economists in estimating the effects of unions on wages (and to a lesser extent on productivity). Essentially all these studies applied and further refined the methodology for estimating the average effects of unions first developed by Gregg Lewis ( 1962 ). It calls for isolating the difference between wages of otherwise comparable union and non-union workers by controlling for other aspects of human capital. This task is made difficult by dynamic processes by which workers and employers react to unionization and the associated wage gains. For example, either adjustment (the shock effect responses described) or selection effects—lower- or higher-skilled workers might select into union jobs or employers might raise their standards for hiring to justify the higher union wage (Lewis 1986 )—render estimation of the union wage premium using conventional cross-sectional data sets (such as the Current Population Survey) incomplete. Nevertheless, in the 1950s and 1960s these estimated union differentials tended to range between 10 to 15 percent, depending on differences in occupations, industries, and regions. Estimates in the 1970s grew to 15 to 20 percent or more, again with considerable variations in and outside this range across different demographic and occupational groups (for a summary of the pre-1980s evidence, see box 1 ). Upon finding the union wage premium to be above 20 percent in some of their data by the late 1970s and early 1980s, Richard Freeman and James Medoff ( 1984 , 54) predicted that these premiums were unsustainable. Indeed, union employment declined as the premium reached its peak, followed by somewhat of a decline in the premium in more recent years (Bratsberg and Ragan 2002 ; Blanchflower and Bryson 2004 ). The predominant explanations for these wage premiums at the time were the traditional neoclassical view of unions acting as a monopoly (whereby they restrict labor supply and therefore increase wage levels) and a view that saw unions as a way to achieve greater rent sharing, particularly in firms or sectors where the product market allowed for sizable rents to exist. Neither Lewis ( 1962 ) nor Freeman and Medoff ( 1984 ) were able to adjudicate between these two hypotheses.

Summary of Pre-1980s Variations in Union Effects on Wages

Unions have a greater positive effect on wages of blacks, particularly black men relative to whites. (Ashenfelter 1972 )

Unions reduce the effects of age and education on earnings. That is, unions increase the earnings of younger workers by raising the entry-level salaries on union jobs above what an inexperienced worker would be paid in a comparable non-union job. At the upper end of the wage distribution, the effects of seniority provisions in union contracts protect older workers from wage erosion after they pass their peak productivity years. (Johnson and Youmans 1971 )

One study estimated the following union–non-union pay differentials by occupation: laborers, 45 percent; transportation equipment operators, 38 percent; craft workers, 19 percent; operatives, 18 percent; service workers, 15 percent; managers, 2 percent; clerical employees, 2 percent; and sales workers, 4 percent. (Bloch and Kuskin 1978 )

Union wage effects also vary across industries: 43 percent in construction; 16 percent in transportation, communications, and utilities; 12 percent in nondurable goods manufacturing; and 9 percent in durable goods manufacturing. (Ashenfelter 1978 )

Unions reduce white-collar/blue-collar wage differentials in firms where blue-collar workers are organized. Unions also reduce intra-industry wage differentials to a degree that this effect offsets the increase in earnings dispersion across industries so that the net effect of union is to reduce wage inequality among workers. (Freeman 1980 , 1982 )

Source: Katz, Kochan, and Colvin 2004 , 241.

Besides estimating the average effects of unions on wages, considerable attention was given to how unions affected income inequality in the post war period. At the firm level, unions have traditionally sought to attach wages to jobs following a principle of “equal pay for equal work.” Naturally, this leaves less room for variation of wages across individuals doing similar work (Freeman 1980 ; Freeman and Medoff 1984 ; Card 1996 ; Card, Lemieux, and Riddell 2004 ; Farber et al. 2018 ). Unions also reduced the pay differentials between occupational groups such as white- and blue-collar workers within firms (Freeman and Medoff 1984 ). Their equalizing effects across firms reflected, as noted, the role of pattern bargaining. Although less well-documented, the threat effect (that is, the motivation of non-union firms to avoid unionization) also played a significant role in equalizing wages in the past when unions were stronger. Although difficult to measure, that threat has largely dissipated given the very low probabilities that a union-organizing drive will occur or, if it occurs, will be successful (Ferguson 2008 ). Despite several successful and highly visible union-organizing drives at media companies (Masters and Gibney 2019 ) and academic institutions (Schmidt 2017 ; Benderly 2018 ), no substantial changes are apparent in the number of elections held or their success rate since 2011. 1

- UNION EFFECTS ON PRODUCTIVITY

Fewer studies have been undertaken on the effects of the average unions on productivity than on wages. The majority have focused on particular industries and also drew on data from the late 1960s through the early 1980s.

Freeman and Medoff ( 1984 ) suggest three potential pathways by which unions can affect productivity: restricting labor supply, restrictive work rules, and “voice.” The restriction to labor supply and work rules set off changes to employers’ allocation of capital and innovations to make more efficient use of higher-cost labor. The third pathway—empowering workers’ voice—however, can facilitate productive information exchange between frontline workers and management as well as boost workers’ loyalty to the firm. Early case studies found positive effects for unions on productivity in industries such as manufacturing, construction, and cement plants (for a review, see Freeman and Medoff 1984 ). Analysis of higher-level industry data included that of Freeman and Medoff ( 1984 ), which tested and reject some of the commonly cited mechanisms for why unions might inhibit productivity (for example, reduced managerial flexibility and prevention of technological change), and of Charles Brown and Medoff ( 1978 ), which also encountered little evidence for positively selected workers and instead supported voice-related or shock effects. Absent finer-detailed data or identification strategies, detailed case studies such as that of Kim Clark ( 1980 ) offered more insight into the potential mechanisms (albeit limited to specific industries)—Clark’s conclusions indeed found ex post changes to workers (such as turnover, absenteeism, discipline problems, and morale) but—more important— to management practices (such as formalization of procedures, worker-manager relations, performance reviews, and so on). Freeman and Medoff ( 1984 ) qualify that worker voice and management response channels could also negatively affect productivity if the state of employment relations is poor. We address the evidence of this mediating variation in union or employment relations quality later in this article.

- UNION EFFECTS ON PROFITS

The positive estimates of union effects on productivity have not, however, extended to effects on firm profits. Most of the studies on this issue report negative effects (Hirsch 2007 ). Unions appear to be associated with rent sharing with unionized firms, particularly in more concentrated industries, though it is not clear whether this is a causal effect (Belman 1988 ). Again, most of these empirical studies used data from the 1970s through the 1990s. One interesting, and to our knowledge unanswered, question is whether this effect still holds today. We would expect the decline in union power and failure of unions to organize the newer large so-called superstar firms in concentrated industries (such as Apple, Microsoft, and Google) would weaken the overall union effects on profits. If so, this suggests that the decline in unions may account for part of the decline in labor’s share of national and corporate income observed in recent decades. The issue warrants more careful research before firm conclusions on this issue can be reached.

In summary, research on the economic effects of unions in the era of the postwar social contract tends to focus on average effects, largely ignoring both the processes by which unions gained and sustained the bargaining power to have an impact, or on the variations in union-management relations in different settings. This began to change as evidence of both longitudinal and cross-sectional variations in union-management relationships became more visible.

- THE BREAKDOWN OF THE SOCIAL CONTRACT

The cumulative effects of the two oil shocks of the 1970s and the expanding union–non-union wage differentials—along with the inability of unions to overcome management resistance in organizing the growing high technology sectors of the economy or even the new plants of many unionized firms (Kochan, McKersie, and Chalykoff 1986 )—put significant stresses on existing collective bargaining relationships. These stresses seemed to explode with the combined effects of the change in political control of the national government that came with the election of Ronald Reagan; the decision of the Federal Reserve Bank to bring down the rate of inflation by raising interest rates and the recession that followed; the deregulation of various highly unionized industries such as trucking, airlines, railroads, and communications; and the rising importance of import competition in key manufacturing industries such as autos, steel, and electronics. The confluence of these policy decisions and economic developments helped launch what was described as a fundamental transformation of industrial relations in the 1980s that led to the demise of the old social contract and a search for new principles to guide labor-management relations (Kochan, Katz, and McKersie 1994 ).

One indication of the fundamental changes taking place in the 1980s was observed in the shift in the structure of wage determination under collective bargaining, a shift that lowered the bargaining power of unions and resulted in lower wage increases than collective bargaining produced in the pre-1980 period. Tables 1 and 2 present estimates of effects of the changes in wage determination that occurred before and after 1980 using the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Current Wage Developments series covering bargaining units with one thousand or more workers (Kochan 1988 ; Kochan and Riordan 2016 ). The regression coefficients in pre- and post-1980 equations in table 1 show that the major causes of the change were that strikes (or the threat of strikes proxied by actual strikes), centralized bargaining structures, and pattern bargaining, sources of bargaining power that drove wage increases in the period from 1957 through the 1970s, no longer served as significant determinants of wage changes in the early 1980s. Thus the forces that produced and sustained the postwar social contract were no longer able to sustain the tandem upward movement of wages with productivity growth. As a result, as shown in table 2 , the model used to explain wage determination in the pre-1980 period overpredicted the post-1980s by an average of 1.35 percent per year. Overprediction was greatest in centralized bargaining structures and in settings where intra-industry pattern bargaining had previously been the common practice. Unfortunately, in 1984 the BLS discontinued the data series that provided the wage data and so we are not able to test whether these differences persisted. Moreover, the expanding gap between aggregate productivity growth and wage growth from the 1980s to today suggests that the breakdown in the social contract has persisted.

- View inline

Wage Change Regressions: 1957–1984

Overpredictions of Post-1980 Wage Changes Using Pre-1980 Model

- VARIATIONS IN UNION EFFECTS AND THE QUALITY OF LABOR-MANAGEMENT RELATIONSHIPS

Starting in the 1980s, a large body of research began examining the effects of variations in the quality of labor-management relationships in both union and non-union establishments and firms within the same industries using what came to be called high-performance work systems. Two early studies of this type found large differences in productivity and product quality across auto assembly plants in the same firm. The differences were associated with variations in grievance rates, employee attitudes (trust) in supervisors, and the extent to which workers were engaged in quality improvement efforts (Katz, Kochan, and Gobeille 1983 ; Katz, Kochan, and Weber 1985 ). These studies had the effect of shifting focus from the average effects of unions on employment outcomes to explore more carefully the complementary (Milgrom and Roberts 1995 ; Black and Lynch 2001 ) or system of practices (Cutcher-Gershenfeld 1991 ; MacDuffie 1995 ; Ichniowski, Shaw, and Prennushi 1997 ) that combined to produce high or low productivity in both union and non-union firms.

The rise of Japanese “transplants” (auto assembly plants opened in the United States in the 1980s by Japanese firms such as Honda, Toyota, and Nissan) proved to be a fertile ground for studying these issues. A major debate developed over why the Japanese transplants appeared to achieve higher productivity and product quality than auto plants owned and managed by U.S. firms. The first documentation of this variation (without controlling for all unobserved factors) showed that average union effects would mask large differences between union and non-union facilities that employed traditional and high-performance work systems. Table 3 reproduces a classic set of comparisons that sparked much of this research. John Krafcik ( 1988 ) compared productivity and quality of auto assembly plants of non-union Japanese producers Nissan and Honda with a joint Toyota-GM unionized facility (NUMMI) and two other more traditionally structured GM-UAW plants using different levels of automation. The NUMMI plant matched and in some cases exceeded the productivity and quality performance of the non-union Japanese transplants and far exceeded the performance of the traditionally structured low and high technology (unionized) GM plants. This work spawned a host of industry-specific studies that documented similar productivity and quality results in organizations employing variations of high-performance work systems (MacDuffie 1995 ; Ichniowski, Shaw, and Prennushi 1997 ; for a review, see Appelbaum, Hoffer Gittell, and Leana 2011 ). Sandra Black and Lisa Lynch ( 2001 ) compared union and non-union manufacturing plants that used traditional and “transformed” or high-performance work system practices and further demonstrated the importance of focusing on the variations in both sectors: transformed plants achieved higher productivity in both union a nd non-union plants. Indeed, the differential between high and low productivity was greater in union than in non-union plants.

NUMMI Productivity Compared with Other Auto Plants in 1986

These quantitative results were collaborated with case studies of a number of transformed labor-management relationships observed in the auto, steel, office product, telecommunications, airline, health care, and other industries. The common features that distinguished transformed relationships was that unions and employers worked together in various forms of partnerships to engage employees in continuous improvement efforts. Many adopted variants of team work or other flexible work systems that departed from the individual job control model that characterized more traditional systems carried over from Taylorism and standard industrial engineering job design principles. Some encouraged and supported different forms of gains sharing thereby adapting the old productivity-wage norm in modified ways. Box 2 summarizes the features of the labor-management partnership at Kaiser Permanente, one of the largest, longest-lasting, and most comprehensive labor-management partnerships of the post-1980s era.

The Kaiser Permanente Labor-Management Partnership

In 1997, the CEO of Kaiser Permanente (KP), the president of the AFL-CIO, and leaders of the coalition of the unions representing employees at KP created what was to become the largest, most long-standing, and most innovative labor-management partnership in the nation’s history.

Over its first decade, the partnership helped turn around Kaiser Permanente’s financial performance, built and sustained a record of labor peace, and demonstrated the value of using interest-based processes to negotiate national labor agreements and to resolve problems on a day-to-day basis. Among its most significant achievements was the negotiation of a system-wide employment and income security agreement for dealing with workers affected by organizational restructurings. This agreement provided a framework that supported the introduction of electronic medical records technology on a scale that has made Kaiser Permanente a national leader in this area. In 2005 negotiations, the parties committed to bring partnership principles more fully to bear to support continuous improvement in health care delivery and performance by forming “unit based teams” (UBTs) of nurses, technicians, doctors, and service providers.

Since 2007 the parties have achieved significant progress in integrating the partnership into the standard operating model for delivering health care by expanding UBTs throughout the organization and demonstrating that high-performing teams that engage employees contribute significantly to improving health care quality and service, reducing workplace injuries, improving attendance rates, and achieving high levels of employee satisfaction with KP as a place to work and a place to get health care. As a result, Kaiser Permanente is now one of the nation’s leaders in the use of front line teams to improve health care delivery.

Source: Adapted from Kochan 2013 .

The bottom line of this body of research is that unions can and have had highly variable effects on managerial practices and on organizational performance, depending on the quality of the labor-management relationship. Traditional arms-length union-management relationships perform poorly relative to more flexible and partnership-oriented relationships. However, because a strong union is a precondition to partnerships (recall GM’s resistance to allowing a union to participate in what the company deemed management issues), these types of partnerships have withered and fewer new ones have been established as union power and density have declined. More broadly, the diffusion of high-performance work systems or high-road strategies also appears to have stalled (Albers Mohrman et al. 1995 ; Osterman 2018 ). The key question is whether unions or some other form of worker organization can regain its role as a significant force for wage and productivity growth. That is, can a new social contract be imagined and achieved in today’s economy? We now turn to this question.

- OUT OF THE ASHES: CURRENT STATE OF WORKER VOICE

So far we have painted a historical picture of the rise and decline of unions and the effects on both wages-compensation and the rise and stalled diffusion of high-road or high-performance work systems. Missing from this story is whether something has filled the void in worker voice and bargaining power as unions have declined. Can these new forms grow large enough to help increase wages or diffuse high-road practices that generate productivity growth? Or have workers lost interest in union representation in light of this long-term union decline? Answering these basic questions is crucial to deriving sensible implications for the future of labor policy.

Three data sets allow us to compare whether worker interest in gaining or having union representation has changed over the years before and after the breakdown in the postwar social contract. Two of these surveys also support comparisons of whether workers are experiencing a gap between the amount of say or influence (voice) they expect to have over conditions at work and their actual level of say or influence. We use these data to first summarize changes over time in interest in unions and then examine a number of other options for meeting worker expectations for a voice at work.

In 1995, Freeman and Rogers ( 1999 ) conducted a national survey of worker voice that identified what they labeled a representation gap; we use the term voice gap here. On average, workers reported that they had less say or influence on their jobs in determining wages, benefits, training, and other working conditions than they thought they ought to have. We conducted a similar national survey in 2017 and found these gaps persisted on compensation, wages, and training and extended to a broader array of workplace issues included in our survey than were measured in the Freeman and Rogers study (Kochan et al. 2019 ). Figure 2 summarizes the 2017 data. The largest voice gaps were reported for benefits, wages, promotions, and job security—essentially the key issues traditionally negotiated in collective bargaining. A majority of respondents reported having less of a voice on these issues than they felt they ought to have on their jobs. Although comparable data are not available for the earlier social contract era before 1980, the data—both that of Freeman and Rogers and the 2017 survey—suggest that a sizable voice gap has persisted since the 1990s.

Voice Gap: Percentage of Workers with Less Involvement Than They Want

Source: Adapted from Kochan et al. 2019 . Data based on Kochan and colleagues’ analysis of Worker Voice Survey.

Note: Calculated as the share of respondents who, on a given issue, rate higher on how much say they ought to have compared to how much say they actually have.

These two surveys, along with a 1977 national survey sponsored by the Department of Labor and conducted by the University of Michigan Survey Research Center, also allow for comparisons of the level of interest in joining a union among unorganized workers (Kochan 1979 ). Figure 3 presents the differences in the percentage of non-union workers who indicated a preference for union representation in nationally representative surveys in 1977, 1995, and 2017. 2 The 1977 and 1995 results were nearly identical: approximately one-third of the non-union workforce indicated they would vote to have union representation if given an opportunity to do so on their current job. Estimates of union support from the 1995 data are likely lower than what they would be if public-sector employees were included. In 2017 that number increased to 48 percent. This number translates into an underrepresentation of unions of approximately fifty-eight million workers. 3

Percent of Non-union Workers Who Would Vote for a Union

Source: Adapted from Kochan et al. 2019 . Based on authors’ analysis of 1977 Quality of Employment Survey (Quinn and Staines 1992 ), Worker Representation and Participation Survey (Freeman and Rogers 1999 ), and 2017 Worker Voice Survey data. Data for 1995 from Freeman and Rogers 1999 , 99.

Note: Each year’s sample excludes self-employed. The 1995 sample also excludes all management occupations.

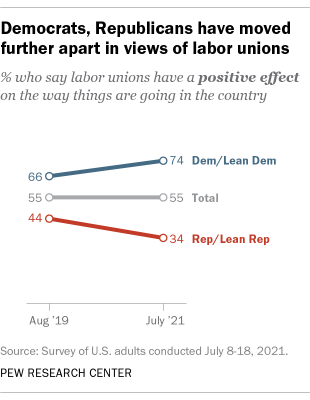

How do the results of these three surveys (that is, the share of non-union workers who would vote for union) comport with other analyses of public opinions on unions? According to Freeman ( 2007 ), citing polls conducted by Peter Hart Associates, worker willingness to join a union from 1984 to 2004 shows a similar pattern—interest hovers in the area of 30 to 40 percent between the 1980s and 1990s but by 2004 reaches a high of 53 percent (see figure 4 ). Meanwhile, Gallup polls on Americans’ opinions of unions since 1936 show a similar pattern in the trend of stagnation of approval from the late 1970s to the 1990s (see figure 5 ). However, no substantial gain is evident between either the 1970s or 1990s and 2017. In 1979, approval sat at 55 percent. By 2017, it had risen to only 61 percent. This minimal change suggests that no major societal change in the role of unions in the economy had taken place in recent decades, but rather that an increasing share of approvers might also see unions as personally instrumental and relevant. These two series suggest that the union-interest indicator from the worker voice survey is not an aberration—instead, it seems as if the antiunion wave of the 1960s and 1970s stagnated until turning slightly more favorable after the Great Recession (other than a negative turn against most institutions during the Great Recession). Unions have become more attractive in that people are more likely to evince interest in joining a union if an election were held at their work .

Non-union Worker Likely Vote in a Union Representation Election, 1984–2004

Source: Freeman 2007 , figure A.

Note : The original figure was based on polls conducted by Hart Research Associates from 1993 through 2014, supplemented with data from a 1984 Harris poll.

Approval of Labor Unions

Source : Gallup 2018 .

- EMERGING FORMS OF WORKER VOICE

Given the long-term decline in unions and the difficulties of organizing using traditional approaches under the National Labor Relations Act, it is not surprising that a variety of new approaches to providing workers a voice have been emerging and continue to emerge. We explored a number of such alternatives in the 2017 worker voice survey. These included both options typically offered by employers and options typically offered independently of employers by groups either working in coalition with one or more unions or on their own. Table 4 lists the options and frequency of their use. Workers are most likely to turn first to their supervisors and coworkers for advice on how to address a workplace problem, likely in part because they are readily available in most workplaces. The other newer options have only been used by 20 percent or less of this sample.

Workers Who Used Each Voice Channel

The number and variety of new forms of organizing and advocating for addressing workers’ issues is impressive and likely to continue to grow. A sampling of these are listed in box 3 . Some, such as the Freelancers Union, focus on professionals, in this case professional freelancers/independent contractors. Others such as the Domestic Workers Alliance focus on low-wage occupations that carry out their work in customers’ homes. Some are affiliated with worker centers across the country, advocate for immigrant rights, and provide advice and legal services in disputes over wage and hour violations, discrimination, harassment, or safety and health. Others, such as Coworkers.org, help employees mount petitions to their employers to change scheduling and other practices. OUR Walmart uses artificial intelligence tools to track and answer employee inquiries about legal rights and potential violations of company policies. Lobstermen 207 is a union-affiliated co-op created to market the catch of independent lobster fishermen in Maine. Still other groups, such as the Fight for $15, mobilize in states and cities for increasing minimum wages.

Examples of New Worker Voice Organizations

AFL-CIO Worker Center Partnerships

Alianza Nacional de Campesinas

Blue Green Alliance

Center on Policy Initiatives

Chinese Progressive Association

CLEAN Carwash Campaign

Contratados

Coworkers.org

Drivers Network

Fight for $15

Freelancers Union

Green for All

Interfaith Worker Justice

Jobs with Justice

Justice for Janitors

Laundry Workers Center

Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy

National Day Laborer Organizing Alliance

National Domestic Workers Alliance

National Guestworkers Alliance

National Taxi Workers Alliance

OUR Walmart

Partnership for Working Families

Raise Up Massachusetts

Restaurant Opportunities Center United

SherpaShare

Tech Workers Coalition

Turkopticon

Workers Lab

Working America

Source : Arvins, Larcom, and Weissbourd 2018 .

Although the range of innovations is impressive, the impact of these forms of organizing to date has been limited relative to that of unions at their peak. Evidence is scant that these innovations have had effects on wages or standards with the possible exception of the Fight for $15 movement in terms of achieving minimum wage increases that appear to be linked to recent wage growth for lower-paid workers (Gould 2019 ). Although some have succeeded in extending opportunities for voice (Coworker.org), labor protections (Domestic Workers Alliance), and job benefits such as health insurance (Freelancers Union) or training (Domestic Workers Alliance) to specific groups of workers who are otherwise unable to access them, none have achieved a level of scale at which they could have an impact on the overall economy or their industry the way that unions’ pattern bargaining did. Nor have any developed a fully self-sustaining revenue model: most still rely on financial support from foundations or unions (Rolf 2016 ). Thus, whether these emerging groups will be successful in building new sources of power that can achieve effects anywhere close to the effects of traditional unions remains to be seen. Clearly, however, the range and number of such efforts indicate that today’s labor advocates are looking to build worker voice and bargaining power in ways not limited to or constrained by existing labor law, union-management relations, or collective bargaining. This has profound implications for the future of labor policy.

- IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY

We now address three interrelated questions. First, what do the data on the current state of worker voice and representation imply for the future of labor policy? Second, what has the history of unions and union-management relations taught us about how labor policy fits with and might contribute to economic policies capable of improving living standards for the majority of Americans? Third, looking beyond policies for worker voice and representation, what other actions might government policymakers take to improve employment standards for union and non-union workers? We end with some more preliminary thoughts about how labor and employment policy might also contribute to meeting the challenges of technological innovations that lie ahead.

The evidence is quite clear that contemporary labor law is failing to deliver on its intended purpose of providing workers the ability to decide whether they want union representation. The survey data presented earlier show that a large and growing number of workers who express an interest in union membership have been and continue to be unable to get it. The best study of the union-organizing process proscribed in the National Labor Relation Act further reinforces this conclusion. John-Paul Ferguson ( 2008 ) traced the outcomes of organizing and first contract negotiations processes overseen by the National Labor Relations Board and the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service from 1999 to 2004. He finds that only 20 percent of those processes that showed enough support to request an election were successful in achieving an initial collective bargaining contract. 4 If the employer resisted to the point the union filed an unfair labor practice charge, the union success rate fell to just below 10 percent. These results suggest that, in reality, employers decide whether workers who express a desire for union representation will get it.

Many other features of labor law are equally ineffective, outdated, or—as one labor law scholar termed it—“ossified” (Estlund 2010 ). In a paper prepared for the seventh-fifth anniversary of the NLRA, Kochan ( 2011 ) suggests that five doctrines that need reconsideration are especially problematic. One pertains to distinctions between who is eligible for union membership and who is excluded. A second relates to the exclusion of topics from mandatory subjects of bargaining that workers want to influence. A third involves constraints on direct forms of employee engagement and participation in decisions about how work is organized or how to improve workplace operations and performance. A fourth is the role of exclusive representation. Last is the determination of separate bargaining units for occupational groups within an enterprise or workplace. This list could go on in regard to features that carry over from labor law conceived in the 1930s for a largely industrial economy that do not fit well with today’s economy and workforce. Indeed, consensus is growing among labor law experts that the time has come to take a clean slate approach to the design of a new labor law in contrast to the multiple failed efforts (such as those in 1977, 1995, and 2008) to make incremental reforms to the existing law. A broad-based discussion of what these new features of labor law should entail is now under way (Milano 2018 ).

- STARTING POINTS FOR A NEW LABOR POLICY

Although discussions of the features of a new labor law are only in the early stages, the evidence reviewed here suggests several basic design parameters for both an updated labor law and a labor policy that promotes forms of labor-management relations that might contribute to building a new productivity- and wage-enhancing social contract.

First, any new labor law and policy has to deliver on the core principle of freedom of association, especially given the evidence that interest in joining a union has increased in recent decades. Workers should be able to decide whether they want representation and those who do should have ready access to institutions and processes that allow them to express their voices at work in ways that allow them to influence the range of working conditions of importance to them. The United Nations’ International Labor Organization includes freedom of association as one of its fundamental principles. That is, workers should have the ability to express their voice collectively and participate in the determination of their working conditions through collective bargaining or other means. As Albert Rees ( 1963 ) clearly stated decades ago, the political functions that unions serve in a democratic society may be as or more important than their economic functions. This principle is often lost or overlooked in economic policy discussions about unions. We present it here as the starting point for building a future labor policy.

Second, given the economic (potentially positive and potentially negative) effects of collective representation, labor policy (both the law and its affiliated administrative arrangements) should be integrated with and an integral part of national economic policies capable of supporting high and increasing levels of productivity that are accompanied by increasing wages and economic security. This is the essence of the old social contract; new ways need to be crafted to achieve similar results in today’s significantly different economic and technological environment. Calls for viewing labor policy as an integral part of economic policy have been made before but have largely been ignored by those in charge of economic policy in both Democratic and Republican administrations. This needs to change.

Third, the results of our worker voice research to date suggest that “no one-size shoe” approach to voice at work fits all issues or all workers. This implies that labor law needs to open up to support a range of voice options that include but are not limited to collective bargaining, direct employee engagement in work design and improvement efforts, consultation or representation on the broad employment strategies adopted by employers through institutions such as works councils (representative and consultative bodies elected by all workers in an establishment that are common in Europe by are not allowed under current U.S. labor law) or representation on company boards (Hirsch 2007 ). Recognizing that “pattern bargaining” is no longer feasible as an instrument for reducing cross-firm income inequality or diffusing high-road strategies, some argue for establishing sectoral bargaining or industry-specific wage boards to set minimum standards (Madland 2018 ).

Fourth, labor policies need to promote high-quality labor-management relationships that contribute both to worker voice and to economic performance. This in turn calls for endorsement of models that support employee engagement, flexibility, investments in training and workforce development, and the types of labor-management partnerships discussed earlier.

Finally, the history of failed efforts at labor law reform suggest one other design principle. Prior efforts have been largely technical affairs among labor policy experts and narrowly debated political battles between labor and management and advocates. Yet the biggest changes in American labor policy have been achieved in times of widespread activism by workers who captured the attention of the American public. The NLRA was enacted in the midst of the Great Depression, when organizing and strike activity were rising and concern over social and political stability was growing. The 1947 amendments to the NLRA were passed when growing numbers of people disapproved of labor unions, presumably on the basis of the notion that labor had become too powerful and too disruptive a force. Public-sector workers began gaining access to collective bargaining in the 1960s in states where teacher unions and others were agitating and engaging in strikes in the absence of effective options for dispute resolution and in the context of escalating social unrest in cities across the country. The point here is that achieving a new labor policy will require a broad-based public awareness and a call to action. That necessary condition is not yet present in society. So the ultimate policy implication is to increase public awareness that labor policy is failing but that ideas on how to fix it are numerous.

- BROADER STRATEGIES FOR IMPROVING JOB QUALITY