Languages/Accessibility

IACP Suicide Prevention Sample Presentations

This section includes numerous PowerPoint presentations on a wide range of suicide-related topics. These presentations are provided for educational purposes and as a resource for agencies looking to create their own similar presentations. Advance through the slides to view all information.

General Suicide Presentations National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action Retooling the Village [FRCPI] Suicide Epidemiology in the United States, (2004) NCSPT Suicide Preventability Workshop Trends in Rates and Methods of Suicide, Harvard Injury Control Research Center and SPRC Florida’s Commitment to Suicide Prevention [FRCPI]

Law Enforcement Suicide Overview Police Suicide: In Harm’s Way II [FRPCI] Stress Behind the Badge: Understanding The Law Enforcement Culture and How It Affects The Officer and Family…Plus Tools and Skills To Overcome The Challenges [FRPCI] Death by Their Own Hand: Have We Failed to Protect Our Protectors? [LASD] Code of Silence/Culture of Suicide: Why Law Enforcement Officers Keep Killing Themselves Despite Our Prevention Efforts [LAPD]

Law Enforcement Suicide Prevention and Intervention Dealing with Depression & Suicide Situations: Tactics for Prevention and Intervention [SBSD] Law Enforcement Suicide: Tactics for Prevention and Intervention [FRCPI] Law Enforcement Suicide: Prevention, Intervention and Postvention [LASD]

More Sample Suicide Prevention Program Materials

- Initial Program Development Guidance

- Sample Suicide Prevention Materials

- Sample Training Materials

- Sample Funeral Protocols

These resources were compiled by the IACP Police Psychological Services Section with assistance from:

Please sign in to read and get access to more member only content.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicidal Behavior

- Handouts: Slides

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Stakeholder Engagement

- Connect with NIMH

- Digital Shareables

- Science Education

- Upcoming Observances and Related Events

Digital Shareables on Suicide Prevention

Everyone can play a role in preventing suicide. Use these resources to raise awareness about suicide prevention.

Suicide is a major public health concern. More than 48,100 people die by suicide each year in the United States ; it is the 11th leading cause of death overall . Suicide is complicated and tragic, but it is often preventable. For more information on suicide prevention, visit our health topic page or download our brochures .

Help raise awareness by sharing resources that help others recognize the warning signs for suicide and know how to get help.

Share these graphics and social media messages

Download and share these messages to help spread the word about suicide prevention. You can copy and paste the text and graphic into a tweet, email, or post. We encourage you to use the hashtag #shareNIMH in your social media posts to connect with people and organizations with similar goals. For more ideas on how to use these resources, visit our help page .

Let's Talk About Suicide Prevention

Help raise awareness about suicide prevention by sharing informational materials based on the latest research. Everyone can play a role to help save lives. Share science. Share hope. https://go.usa.gov/xvWK6 #shareNIMH

Copy post to clipboard

If You’re in Crisis, Help is Available

If you’re in crisis, there are options available to help you cope. You can call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at any time to connect with a trained crisis counselor. For confidential support available 24/7 for everyone in the U.S., call or text 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org, or visit https://go.usa.gov/xyxGa . #shareNIMH

Save the Number, Save a Life

Disponible en español

Save the number, save a life. Add the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (988) to your phone now—it could save a life later. Trained crisis counselors are available to talk 24/7/365. Visit https://go.usa.gov/xyxGa for more info. #shareNIMH

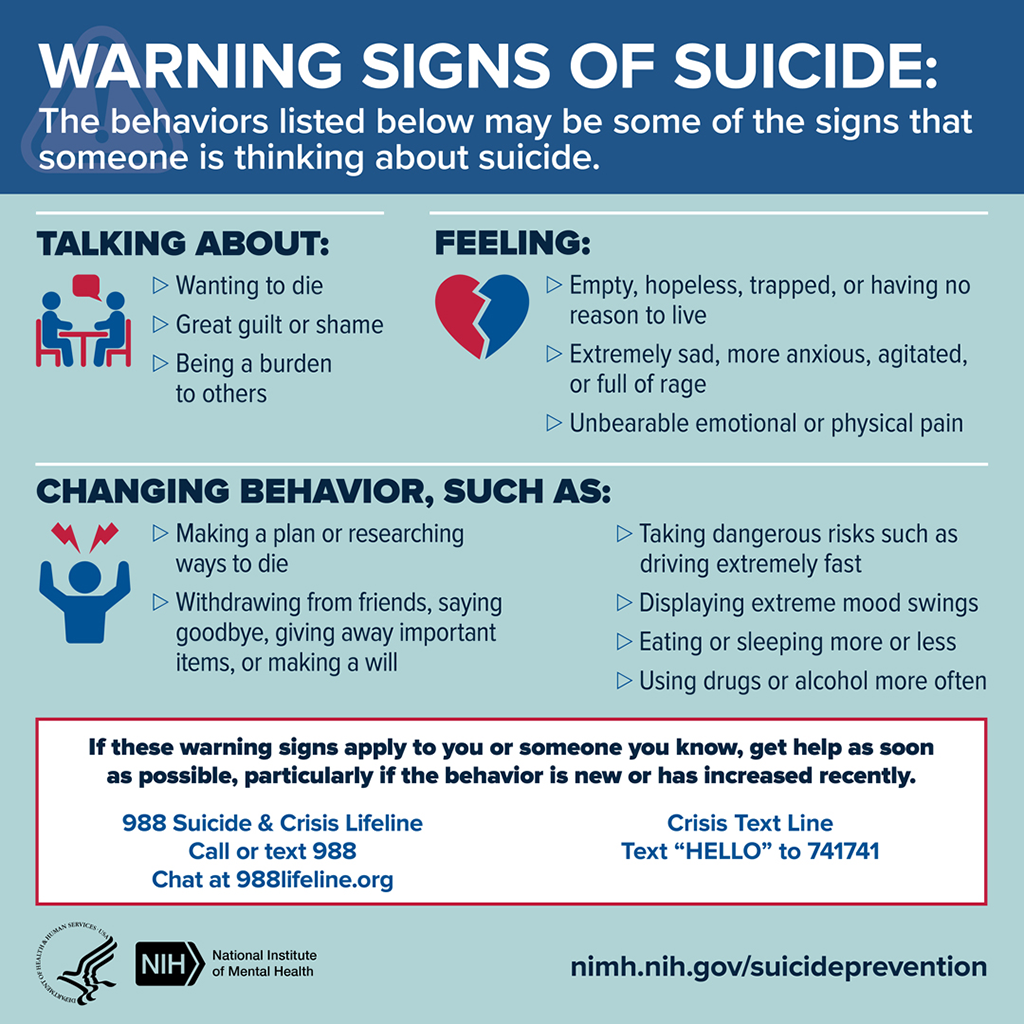

Warning Signs of Suicide

Suicide is complicated and tragic, but it is often preventable. Knowing the warning signs for suicide and how to get help can help save lives. Learn about behaviors that may be a sign that someone is thinking about suicide. For more information, visit https://go.usa.gov/xVCyZ #shareNIMH

5 Action Steps for Helping Someone in Emotional Pain

How can you make a difference in suicide prevention? Learn about what to do if you think someone might be at risk for self-harm by reading these 5 Action Steps for Helping Someone in Emotional Pain: https://go.usa.gov/xyxGc #shareNIMH

Tips for Talking With a Health Care Provider About Your Mental Health

Don’t wait for a health care provider to ask about your mental health. Start the conversation. Here are five tips to help prepare and guide you on talking to a health care provider about your mental health and getting the most out of your visit. https://go.usa.gov/xV3hH #shareNIMH

Mental Health Matters

Your mental health matters. Mental health is just as important as physical health. Good mental health helps you cope with stress and can improve your quality of life. Get tips and resources from NIMH to help take care of your mental health. https://go.nih.gov/wwSau0W #shareNIMH

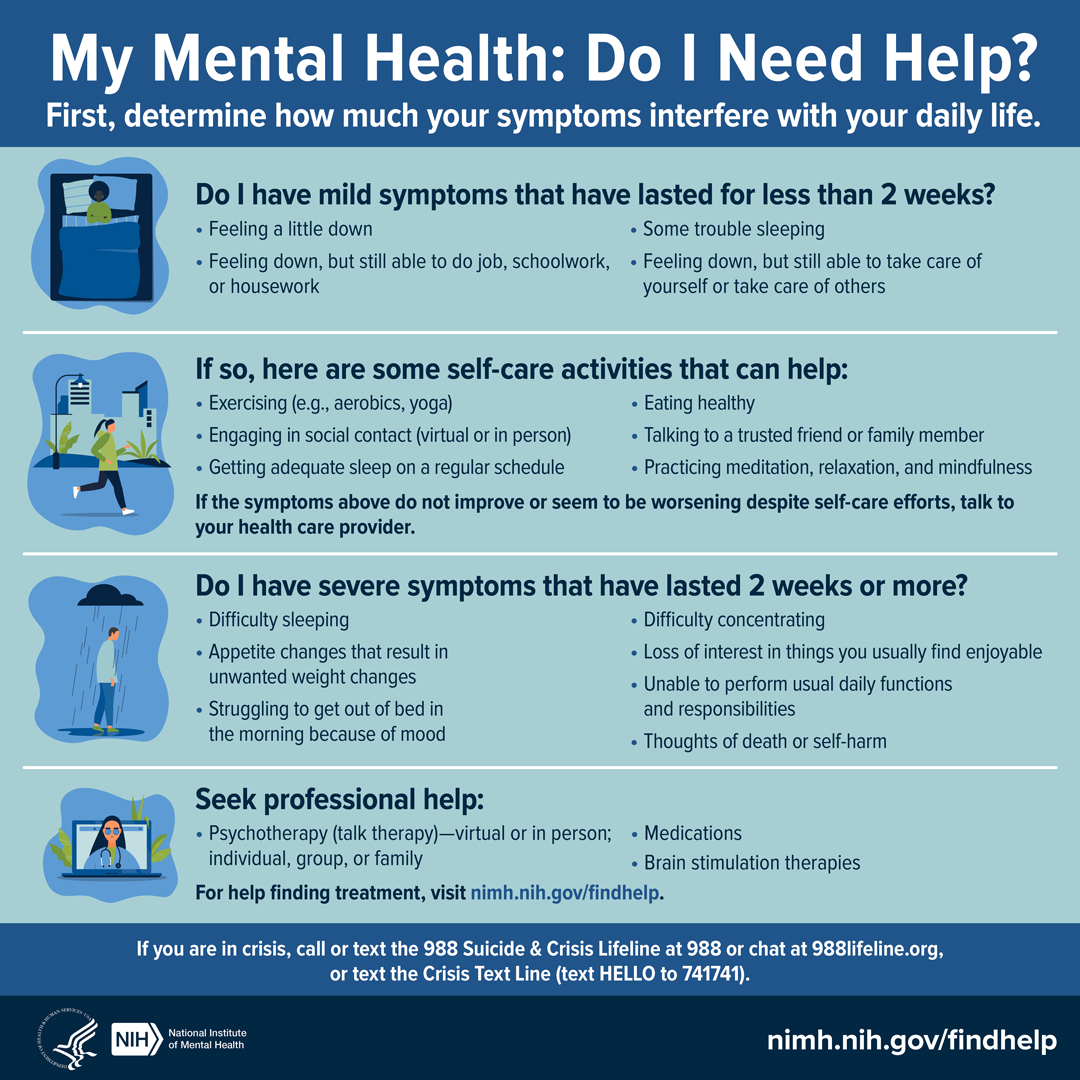

My Mental Health: Do I Need Help?

Do you need help with your mental health? If you don't know where to start, this infographic may help guide you. https://go.usa.gov/xGfxz #shareNIMH

Help for Mental Illnesses

If you or someone you know has a mental illness, is struggling emotionally, or has concerns about their mental health, use these resources to find help for yourself, a friend, or a family member: https://go.nih.gov/Fx6cHCZ . #shareNIMH

Use videos to educate others

Click “Copy Link” link to post these videos on social media, or embed them on your website.

NIMH Experts Discuss Youth Suicide Prevention: Learn how to talk to youth about suicide risk, how to identify the warning signs of suicide, risk factors for suicide, and about NIMH-supported research on interventions for youth suicide prevention.

Understanding and Preventing Youth Suicide Podcast: Learn who is at increased risk for suicide, how it’s impacting the nation’s youth, and most importantly, what NIMH is doing about this tragic and preventable issue.

Hope Through Early Prevention and Intervention: Share information on NIMH research efforts to identify at-risk individuals, help them improve quality of life, and prevent suicide attempts.

NIH Experts Discuss the Intersection of Suicide and Substance Use : Learn about common risk factors, populations at elevated risk, suicides by drug overdose, treatments, prevention, and resources for finding help.

Learn more about suicide prevention

more information about suicide prevention, brochures and fact sheets, statistics, 988 suicide & crisis lifeline .

Last Reviewed: July 2023

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley Open Access Collection

Hospital presenting suicidal ideation: A systematic review

Dr. emma fawcett.

1 Department of Psychology, University College Dublin, Dublin Ireland

Prof. Gary O'Reilly

Associated data.

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Research indicates that the emergency department is the primary setting for people to present with suicidal ideation. Attempting to provide interventions for this population depends greatly on understanding their needs and life circumstances at the time of presentation to services, therefore enabling more appropriate treatment pathways and services to be provided.

This review aims to collate, evaluate and synthesize the empirical research focused on the population of people presenting to hospital settings with suicidal ideation.

A systematic literature search was performed. Articles that met a specified set of inclusion criteria including participants being over 18, not being admitted to hospital and presenting to an emergency department setting underwent a quality assessment and data analysis. The quality assessment used was the EPHPP Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies ( Thomas et al., 2004).

Twenty‐seven articles were included in the review. Studies were quantitative and of reasonable methodological quality (Thomas et al., 2004). The literature was characterized by demographic information, mental health factors associated with the presentation to hospital and treatment pathways or outcomes reported. The reviewed research showed that people presenting to emergency departments with suicidal ideation were varying in age, gender, ethnic background and socio‐economic status (SES). Large proportions of studies reported psychosocial factors alongside interpersonal struggles as the main presenting reason. The review highlights large variability across these factors. Mental health diagnosis was common, previous suicide attempt was a risk factor, and treatment pathways were unclear. The review identifies the outstanding gaps and weaknesses in this literature as well as areas in need of future research.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the review highlights the prevalence of people reporting interpersonal factors as the reason for suicidal ideation and not mental health disorders or diagnosis. Despite this, no mention of trauma or life stories was made in any study assessing this population. Despite a large variation across studies making synthesis difficult, data proves clinically relevant and informative for future practice and guidance on areas needing further research.

Key Practitioner Message

- Large variation in the types of presentations of suicidal ideation is seen across hospital settings.

- Formal assessment for suicidal ideation is inconsistent across settings and often lacks psychological input relying on assessment tools with limited clinical utility.

- Psychosocial factors were repeatedly reported as causes for experiences of suicidal ideation, yet no focus or mention of trauma and assessment of wider contextual factors is mentioned in any aspect of the presentation, assessment or pathway.

- People presenting to hospital represent only a small amount of those experiencing suicidal ideation indicating a clear and consistent treatment pathway is required for this population.

1. INTRODUCTION

Suicide is a global and complex phenomenon resulting in the annual loss of more than 800,000 lives worldwide (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2014 ). The number of suicide attempts greatly exceeds the number of deaths by suicide, and it is estimated that there are as many as 20 suicide attempts for every death by suicide (WHO, 2014 ). The WHO has reported that effective suicide prevention strategies should be supported by regular monitoring of suicide rates. Most countries have systems to record and process information relating to deaths by suicide not many have equivalent systems dedicated to non‐fatal suicidal behaviours (Perry et al., 2012 ). As a result, the true prevalence of a range of suicidal behaviour in the general population is not well known and is made further difficult to assess considering not everyone engaging in suicidal behaviours seek help for these concerns (Milner & De Leo, 2010 ). While suicide is termed a significant cause of mortality worldwide, the continuum of suicidal behaviour ranges across a broad spectrum from thoughts of self‐harm or suicide to fatal or non‐fatal suicide attempts (Goodfellow et al., 2018 ). Suicidal ideation, defined as thoughts of engaging in behaviour intended to end one's life, has been identified as an important precursor of both attempted suicide and suicide (Crandall et al. 2006 ).

Emergency departments (ED) have been identified as important environments for suicide prevention as they provide opportunities for clinicians to engage with and provide support to people presenting with suicidal ideation (Griffin et al., 2019 ). One of the most frequently utilized methods of estimating the incidence of non‐fatal suicidal behaviour is by noting such behaviour on presentation to ED. While the majority of literature focuses on self‐harm presentations, few look at profiles of people who present to services with suicidal ideation. In addition to this, there are no standard or set clinical guidelines for the assessment and treatment of people presenting with suicidal ideation to acute settings (Griffin et al., 2019 ). The ED is the first point of contact for the majority of people with suicide‐related behaviour (Ceniti et al., 2020 ).

Previous studies have reported that people who attempt suicide were more likely to report ongoing suicidal ideation during psychiatric evaluation in the ED (Orsolini et al., 2020 ). Suicidal ideation was self‐disclosed frequently by patients in ED waiting rooms and patients who disclosed suicidal ideation did not always receive referrals for mental health services (Kemball et al., 2008 ). The emerging knowledge that ED are increasingly an important setting for introducing suicide prevention measures means studies have begun to examine ways to developing effective interventions to initiate during ED stays for patients who have attempted suicide (Boudreaux et al., 2013 ; Hirayasu et al., 2009 ). With suicide rates globally growing, the increasing number of ED visits for suicide is and will continue to be a significant challenge for clinicians. Logically holding this knowledge in mind, research on suicidal behaviour in ED is highly desirable and potentially highly critical to support a large population in need.

Suicidal ideation is highly prevalent across younger demographics, men aged 20–24 and women aged 15–19 being the most common presentation (WHO, 2014 ) and older adults being comparatively rare. Many factors have been identified as increasing suicidal ideation risk among populations. Living in a low socio‐economic area increases risk of presenting to ED with both self‐harm and suicidal ideation (Skegg, 2015 ). An international systematic review conducted in 2013 suggests that 84% of adults who self‐harm meet diagnostic criteria for a psychiatric disorder, 49% are diagnosed with depression and anxiety, 44% with depression and substance misuse and 6% with psychosis (Hawton et al., 2013 ). Unfortunately, literature in the United Kingdom also states that relatively few patients who present to hospital following self‐harm are referred to mental health services, particularly in more deprived areas of the United Kingdom (Carr et al., 2016 ). As well as these factors, a previous attempt of suicide is the greatest risk factor for completed suicide (Fedyszyn et al., 2016 ). Large variation in presentations and lack of reliable information from ED makes it difficult to understand and analyse to implement strategies to improve outcomes. It is important to note that often risk factors for presenting to hospital settings with suicidal ideation and risk factors for suicidal ideation itself may be different.

1.1. Current research

This systematic review of the available literature aims is to provide a detailed profile of presentations to ED for people reporting suicidal ideation.

This systematic review aims to evaluate the presentations of people presenting to emergency healthcare settings or services with suicidal ideation. The questions supporting the review include the following:

- Who is presenting to services with suicidal ideation?

- How many presentations of people reporting suicidal ideation are seen in hospital settings?

- Are there any risk factors or protective factors associated with these presentations?

- Are there any outcome data or follow‐up data of these presentations?

It is hoped that with a greater understanding of these population needs, the results could help to develop and refine strategies for preventing and intervening with suicidal ideation.

2.1. Design

A systematic literature review was carried out in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021 ). Articles that met a specified set of inclusion criteria underwent a quality assessment and thematic synthesis to facilitate a maximally comprehensive insight into the extant research. The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement (Page et al., 2021 ).

2.2. Search strategy

A subject‐specialist librarian was consulted in developing an appropriate search strategy. The databases PsycInfo (ProQuest), Medline and CINAHL (EBSCO) were searched until June 2021. This set of databases affords a comprehensive overview of the peer‐reviewed literature in social and health sciences. Reference lists were used to identify further studies. The search strategies are provided below. Keywords were selected for the search including

(suicide OR suicidal ideation)

('hospital'/exp OR hospitalization OR hospital OR ed OR emergency department OR clinic)

Electronic searches identified articles that contained this combination of keywords anywhere in the article. The search was restricted to English‐language articles in peer‐reviewed journals, which described empirical research with human participants. The search did not impose any restrictions in relation to publication date, research location or research methods.

2.3. Inclusion criteria

The review used the following inclusion criteria:

- Studies should be set in ED or emergency services/clinics.

- Studies should only include participants of 18 years or older.

- Studies should only include outpatient populations/people presenting to services, not inpatients.

- Studies must include participants with a presenting problem of suicidal ideation.

- Studies must include demographic information on participants presenting to services.

2.4. Exclusion criteria for studies

- Studies not published in English

- Studies that did not have emergency room/services as the setting

2.5. Screening

References were exported to a reference management software (Covidence). All articles were initially screened through inspection of their title and abstract (EF and AB). Articles that clearly did not meet inclusion criteria were excluded at this stage, with all other articles proceeding to full‐text eligibility assessment. Decisions were documented using Covidence.

Two pairs of reviewers with clinical and research expertise (EF and AB) screened titles and abstracts independently. We retrieved full‐text articles if either or both of the reviewers considered a study potentially eligible. Both reviewers read the full texts, and consensus was reached regarding eligibility. The PRISMA flow chart describes the review process with reasons for exclusion (Figure 1 .)

Prisma flow diagram for systematic review

Inter‐rater agreement on screening decisions at the title and abstract phase was reported as 94.2% and reported at 96.7% on the full‐text screening stage. Doubts about eligibility were resolved through team discussion, guided by the aim of maximal inclusiveness, reviewers erring on the side of inclusion over exclusion.

2.6. Data extraction

Studies meeting all inclusion criteria were coded to extract data relating to demographics (e.g. sample size and participant demographics), key characteristics of suicidal presentation (e.g. method, assessment tools and diagnosis), limitations and results. An Excel file was created to extract data. The following information was extracted; number of participants, mean age, male/female participants, socio‐economic status (SES), education, race/ethnicity, marital status, means of suicide attempt, reason for suicide attempt, previous suicide attempts, mental health diagnosis, assessment tool used, outcome of presentation and previous mental health diagnosis. See Table 1 for data extraction template.

Data extraction template

| Authors name | Number allocated to study for results section. | Country | Year published | Number of participants included in the study | Male/female participants | Method of recruitment | Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes: Demographic | Outcomes: Mental health | Assessment | Follow‐up data | |||||||

| Xhang & Xu | 1 | China | 2007 | 74 | 25/49 | Emergency room | Age, education level, SES, marital status, physical illness | Mental illness diagnosis, means of suicide, reason for suicide | Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) | No |

| Bezarjan‐Hejazi et al. | 2 | USA | 2017 | 24,590 | 9728/14862 | Emergency room | Age, race | Mental health diagnosis, means of suicide, alcoholism | Not reported | No |

| Wei et al. | 3 | China | 2013 | 239 | 53/186 | Emergency room | Age, education level, SES, employment status, marital status | Mental illness diagnosis, means of suicide, reason for suicide, alcoholism, previous suicide attempt | Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) | No |

| Alves et al. | 4 | Brazil | 2017 | 2142 | 683/1459 | Emergency room | Age | Mental illness diagnosis, means of suicide, alcoholism | Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) | No |

| Xhang, Jia, Jiang & Sun | 5 | China | 2006 | 74 | 25/49 | Emergency room | Age, marital status | Mental illness diagnosis, means of suicide, reason for suicide attempt | Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) | No |

| Donald, Dower, Correa‐Velez & Jones | 6 | Australia | 2006 | 95 | Emergency room | Age, marital status, education level | Mental illness diagnosis, alcoholism | Informal intake assessment | No | |

| Kim et al. | 7 | Korea | 2018 | 888 | 351/537 | Emergency room | Age, education level, SES, marital status, physical illness | Mental illness, means of suicide | Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) C‐SSRS | No |

| Larkin, Smith & Beautrais | 9 | USA | 2008 | 52,774 | 8610/8164 | Emergency room | Age, SES, race | No | ||

| Kim, Kim, oh & Cha | 10 | South Korea | 2020 | 3698 | 1266/2436 | Emergency room | Age, employment status | Mental illness diagnosis, reason for suicide attempt, alcoholism, previous suicide attempt | Psychiatry led assessment | No |

| Pavarin et al. | 11 | UK | 2014 | 505 | 199/306 | Emergency room | Age, race | Reason for suicide attempt, alcoholism, previous suicide attempt | Nurse assessment | Treatment pathway |

| Hepp et al. | 12 | Zurich | 2004 | 404 | 120/204 | Emergency room | Age, employment status, marital status | Mental illness diagnosis, means of suicide | Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) | Treatment pathway |

| Stapelberg, Sveticic, Hughes & Turner | 13 | Australia | 2020 | 20,526 | 10,341/11249 | Emergency room | Age | Mental illness diagnosis, previous suicide attempt | Machine algorithm | No |

| Wei et al. | 14 | China | 2013 | 366 | 53/186 | Emergency room | Age, educational status, marital status, employment status, SES | Mental illness diagnosis, means of suicide, reason for suicide, alcoholism, previous suicide attempt | Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) QOL scale | No |

| Wei et al. | 15 | China | 2018 | 239 | 53/186 | Emergency room | Age, educational status, marital status, employment status, SES | Mental illness diagnosis, means of suicide, reason for suicide, alcoholism, previous suicide attempt | Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) QOL scale | No |

| Ceniti Heineckea & McInerney | 16 | Canada | 2018 | 280 | Emergency room | No | ||||

| Keskin Gokcelli et al. | 17 | Turkey | 2017 | 63 | 30/33 | Emergency room | Age, education, marital status, physical health | Mental illness diagnosis, means of suicide attempt | No | |

| Griffen et al. | 18 | Northern Ireland | 2019 | 13,774 | 8646/5098 | Emergency room | Age | Mental health diagnosis, alcoholism | Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) | Treatment pathway |

| Marriott, Horrocks, House & Owens | 19 | UK | 2013 | 1854 | Emergency room | Mental illness diagnosis, means of suicide, previous suicide attempt | No | |||

| Woo et al. | 20 | Korea | 2018 | 328 | 145/183 | Emergency room | Age, educational status, SES, marital status | Mental illness diagnosis, means of suicide, reason for suicide, alcoholism, previous suicide attempt | HDRS Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) | No |

| Goldberg, Ernst & Bird | 21 | USA | 2007 | 257 | 146/111 | Emergency room | SES, employment status, marital status, race | Mental illness, alcoholism, previous suicide attempt | No | |

| Bi et al. | 22 | China | 2010 | 239 | 53/188 | Emergency room | Age, educational level, SES, employment status, marital status | Mental illness diagnosis, means of suicide, reason for suicide, alcoholism, previous suicide attempt | Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) HDRS | No |

| Zeppengno et al. | 23 | Italy | 2015 | 280 | 97/183 | Emergency room | Educational level, employment status, marital status | Mental illness diagnosis | Beck Scale for suicidal Ideation (BSS) | No |

| Poor, Tabatabaei & Bakhshani | 24 | Iran | 2014 | 369 | 129/240 | Emergency room | Education level, SES | Mental illness | No | |

| Corcoran, Keeley, Osullivan &Perry | 25 | Ireland | 2004 | 4463 | 2091/2372 | Emergency room | Age | Mental illness diagnosis, means of suicide, alcoholism | No | |

| Atay, Yaman, Demġrd & Akpinar | 26 | Turkey | 2014 | 640 | Emergency room | Marital status | Mental illness diagnosis, previous suicide attempt | No | ||

| Cripps et al. | 27 | UK | 2020 | 2211 | 1618/1701 | Emergency room | Age, SES, race | Mental illness | No | |

2.7. Quality appraisal

Relevant outcomes for each of the included studies were rated for methodological quality using published rating scales. For quantitative outcomes, methodological quality was assessed using the EPHPP Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (Thomas et al., 2004 ). This checklist evaluated each study's internal and external validity as either strong, moderate or weak by appraising: study design, analysis, withdrawals and dropouts, data collection practices, selection bias, invention integrity, blinding as part of a controlled trial and confounders.

This tool provided well‐defined instructions on how to rate each criterion and allowed for the systematic evaluation of studies with a range of quantitative experimental designs. When completing the quality assessment, two studies were removed due to being categorized as weak quality. See Table 2 for quality rating assigned to each study.

Quality rating assessment on the EPHPP protocol: results for all studies included

| Study referenced by first author | Selection Bias | Study design | Confounder | Blinding | Measures | Attrition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xhang 2007 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA |

| Bezarjan‐Hejazi 2017 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Wei 2013 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA |

| Alves 2017 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | NA |

| Xhang 2006 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Donald 2006 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Kim 2018 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA |

| Drew 2006 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA |

| Larkin 2008 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Kim 2020 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA |

| Pavarin 2014 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Hepp 2004 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA |

| Stapelberg 2020 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Wei 2013 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA |

| Wei 2018 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA |

| Ceniti 2018 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA |

| Keskin Gokcelli 2017 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Griffen 2019 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA |

| Marriott 2013 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Woo 2018 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA |

| Goldberg 2007 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA |

| Bi 2010 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA |

| Zeppengno 2015 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Behmanehsh Poor 2014 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA |

| Corcoran 2004 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA |

| Atay 2014 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Cripps 2020 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA |

2.8. Analysis

There was significant methodological and clinical heterogeneity between included studies. A meta‐analysis of quantitative data was viewed as inappropriate, and a descriptive approach to synthesis was employed. Observed patterns of similarity and difference between study populations, presentations and outcome measures were critically appraised.

The initial search yielded 4436 articles. Of these, 324 articles were identified as duplicates and discarded. The remaining 4112 articles were screened by abstract, at which stage 3992 of these were excluded, leaving 120 articles for the full‐text screening process. A further 91 articles were excluded. Two studies were removed due to being in the lowest quality range. Twenty‐seven full‐text articles were included in the final review.

3.1. Description of studies

The 27 included studies were all conducted in a general hospital setting. Over half of the studies were from countries where English is not the first language (59%) with 40% from English‐speaking countries. Ten studies (37%) were retrospective chart reviews, and the remainder cohort studies (63%).

3.2. Methodological quality of studies

The 27 included studies were assessed using the EPHPP Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (Thomas et al., 2004 ).

Identified high‐risk areas (weak studies) included non‐representative samples, non‐randomized studies, not controlling for confounding variables, high withdrawal rates and no blind studies. Low‐risk areas (strong studies) included randomized studies, approved and reliable assessment tools, ensuing sample represents population, controlling for confounding variables, high intervention integrity and blinding within interventions. Twenty‐nine studies were included for quality rating using the EPHPP Quality Assessment Tool. Twenty‐seven rated as moderate, and two rated as weak for quality. A second reviewer completed quality assessments also and returned an inter‐rater agreement of 93%.

3.2.1. Socio‐demographic factors

The overall number of participants included in the analyses from a total of 27 studies was 130,882.

The studies included focused on an adult population and not including paediatric research. Three of the studies (Alves et al., 2017 ; Bazargan‐Hejazi et al., 2017 ; Wei et al., 2013 ) included age group 16+ as their overall population. One study focused exclusively on older adult population (Keskin Gokcellia et al., 2017 ). Average age of participants ranges between studies to a large degree. An overall calculation including all studies included in the review indicated the average age for presentations to ED settings was 33.69 years with an age range of 16–91 years. With the large variation in age ranges across a large amount of studies, removing the older adult study did not significantly affect the average age.

Two studies did not include a breakdown of male or female presentations. Two studies reported male to female ratio as an overall percentage (Ceniti et al., 2020 ; Marriott et al., 2003 ), with both reporting 60% female presentations and 40% male presentations. Overall, the number of males attending across all 23 studies was 14% compared to 86% female. The three studies with higher numbers of male participants were from English‐speaking Western countries (two studies reporting from the United States and one from Northern Ireland).

Ten of the 27 studies reported on education level of people presenting to the ED settings. Of these, only two studies reported more than 50% of the participants having completed primary school level, only one reported more than 50% completing second‐level education, and all 10 studies reported less than 30% of people attending third‐level education settings.

Race/ethnicity

Only four of the 27 studies included data on the race/ethnicity of people presenting to the ED settings (Bazargan‐Hejazi et al., 2017 ; Cripps et al., 2020 ; Goldberg et al., 2007 ; Larkin et al., 2008 ). Of these, mixed results were reported; in two of them, more than 50% of the participants were White with the ‘other’ category reporting more than 20% in each study. Variation based on the location of where the research was conducted is important, for example, one study reported 32% of people to be Latino. Many studies commented on reporting race as ‘other’ throughout the assessment process and therefore not including data on it when reporting final results.

Marital status

Thirteen studies out of 27 included data on the marital status of people presenting to the ED. Of these, 38% of people reported that they were married, and 42% reported to be single. Of the 27 studies, nine reported that 7% of people were divorced, and five studies collectively reported that 4% of people were widowed.

Ten out of 27 studies reported on the employment status of participants. Out of these 10 studies, only three of 10 (Bi et al., 2010 ; Wei et al., 2013 , 2018 ) reported that more than 50% of people were in employment at the time of presenting. The number of people presenting who were employed at the time was 42%. Out of the same 10 studies, the number of people presenting as unemployed was 37%. Of these 10, three studies (Goldberg et al., 2007 ; Zeppegno et al., 2015 ; Zhang & Xu, 2007 ) reported that unemployed people accounted for greater than 50% of total presentations. Six studies reported on participants being classified as students. Of these six studies, 16% of the participants reported being full‐time students.

Ten out of 27 studies reported on the SES status of the participants. The number of peoples across the 10 studies reporting low SES was 26%. Only one of these studies (Larkin et al., 2008 ) had more than 50% of people report low SES. The number of people reporting middle SES was 50% with seven studies reporting more than 50% of people identified themselves in the middle SES bracket. Only eight of the 10 studies reported people in the high SES bracket, with the number of people being 21%. All of these studies had 30% or less participants' identity in this category.

3.3. Assessment factors

Of the 27 studies included, the following four assessment tools/methods were reported—screening tools and psychosocial interview, psychosocial interview, machine algorithm and medical assessment only. Fifty‐five per cent of the 27 studies reported using one or a combination of screening tools for assessment in the ED. The screening tools used in the studies were the following: Suicidal Intent Scale (Beck et al., 1974 ), Scale for Suicidal Ideation (Beck et al., 1979 ), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton, 1960 ), Columbia‐Suicide Severity Rating Scale (Posner et al., 2011 ), Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV Axis I Disorders (First et al., 1997 ) and a variety of measures of quality of life.

Thirty‐seven per cent of studies reported to carry out medical assessment only, meaning no psychological or psychiatric assessment took place. Four per cent of the studies reported to use psychosocial interview only, and 3% of studies (Stapelberg et al., 2020 ) reported using a machine algorithm for assessment purposes.

Varying results were presented on the amount of time someone spends receiving an assessment when presenting to the ED with suicidal ideation. Nineteen out of 27 studies reported on the time spent with a person during initial assessment. Fifty‐five per cent of studies reported time spent on assessment was between 1 and 2 h, 33% reported spending more than 2 h with each person, and 22% reported less than 1 h spent on assessment. Four studies (Goldberg et al., 2007 ; Wei et al., 2013 , 2018 ; Xhang & Xu, 2007) reported on the time of the presentation to the ED. Results indicate 52% of presentations were between 8 AM and 8 PM (day) and 48% of presentations were between 8 PM and 8 AM (night).

The outcome of the presentation for 10 of the 27 studies was recorded as either admitted or discharged. In three of the 10 studies (Alves et al., 2017 ; Atay et al., 2014 ; Bazargan‐Hejazi et al., 2017 ), over 50% of people were reportedly discharged. The amount of people presenting and discharged in these 10 studies was 39%. In four of the 10 studies (Bazargan‐Hejazi et al., 2017 ; Goldberg et al., 2007 ; Marriott et al., 2003 ; Pavarin et al., 2014 ), over 50% of the people presented were admitted to inpatient care. The number of people admitted to hospital of the 10 studies included was 34%.

In four studies, referral to community services were recorded also. The following were the percentage of people in those studies who received a referral to attend community services: 9%, 29%, 54% and 15%. Two studies also reported deaths indicating 1.3% (Zhang et al., 2006 ) and 9% (Bazargan‐Hejazi et al., 2017 ) of participants died after presenting to the ED setting. People who were neither classified as admitted or discharged were sent back to their GP, community teams or nursing or left without an onward referral.

Twelve studies reported on participants having previously had a suicide attempt recorded. Only one study (Goldberg et al., 2007 ) reported more than 50% of participants having a previous suicide attempt. The number of participants who met these criteria from the 12 studies recording these data was 31%.

3.4. Mental health factors

3.4.1. suicide attempt/ideation reasons.

Eight studies reported on reasons given by participants for presenting to the ED with suicidal ideation. Reasons attributed to love/marriage were the most commonly reported. This reason was reported in all eight studies, while in four of the eight studies, it was reported by more than 50% of participants as the main reason they felt suicidal thoughts (Kim et al., 2020 ; Wei et al., 2013 ; Woo et al., 2018 ; Zhang & Xu, 2007 ). In six of the eight studies, family and relationship problems were recorded by participants. Four of the studies reported work/study concerns to be the main reason for experiencing suicidal ideation. Three studies report physical illness as being the main reason for them, while only two studies (Wei et al., 2018 ; Woo et al., 2018 ) record people reporting mental illness as the reason for their experience. One study reported on participants reporting physical illness as being a main factor for their experience of suicidal ideation. This study reported 5.4% people reporting this reason (Zhang & Xu, 2007 ).

3.4.2. Means of suicide

Fifteen of the 27 studies reported on the method used by participants in attempting suicide or engaging in suicidal behaviour. The majority of studies report on two main methods of suicide—self‐poisoning or self‐harming behaviour. Of the 15 studies, nine reported that more than 50% of participants had reported self‐poisoning as the method of suicide. The rate across the 15 studies for self‐poisoning was 55%. Fourteen of the 15 studies reported self‐harming behaviour as a means of suicidal ideation. The number of participants reporting self‐harming as a method of suicidal ideation across the 14 studies was 11%. Five studies reported drug overdose as a method of suicide with three of the five studies reporting over 60% of participants overdosing. Four of the five studies report firearms as the method of suicidal ideation; however, the percentage of people reporting this was very low (1%–14%). Hanging and jumping from a height were also reported in five studies as methods of suicide. 3.6% of people engaged in hanging as a method of suicide, and 4.2% of people engaged in jumping from a height.

3.4.3. Alcoholism

Eleven studies reported on the participants suffering from alcohol‐related problems and being intoxicated when presenting to the ED. Of these 11 studies, four of them (Bi et al., 2010 ; Goldberg et al., 2007 ; Griffin et al., 2019 ; Kim et al., 2020 ) reported more than 40% of presentations to meet these criteria. The number of people presenting meeting these criteria of the included studies was 24%.

3.4.4. Mental illness

Ten out of 27 studies reported on specific mental illness diagnosis received by people prior to presenting at the ED. The following diagnoses were the ones reported by participants: schizophrenia, mood disorder, depression, personality disorder, psychosis and adjustment disorder. Three studies (Bazargan‐Hejazi et al., 2017 ; Cripps et al., 2020 ; Kim et al., 2018 ) reported people presenting with a diagnosis of schizophrenia although it was a low percentage of people: 11%, 4% and 2%. Nine of the 10 studies reported people presenting with mood disorders; the percentage of people was 29% across the nine studies. Nine out of the 10 studies also reported people presenting with a diagnosis of depression; the number of participants across the nine studies was 19%. Three of the 10 studies reported people presenting with a diagnosed personality disorder: 3%, 8% and 10% (Bazargan‐Hejazi et al., 2017 ; Cripps et al., 2020 ; Woo et al., 2018 ). Nine out of the 10 studies reported people presenting with an adjustment disorder; the number of people presenting with this across the nine studies was 12%. Eight out of the 10 studies reported people presenting with psychosis. The number of people with this diagnosis was 7% across the eight studies.

Some additional information which was not analysed but mentioned in more than three studies should be noted. Studies reported that the time of year with the highest suicide rate was November, followed by March with the least in June/July (Stapelberg et al., 2020 ).

4. DISCUSSION

This review identified and examined 27 papers which reported on people presenting to emergency settings with suicidal ideation. Summarizing these studies provided a large amount of data giving a rich understanding of the profiles of presentations to the ED. With regard to the methodological quality of included studies, few studies provided highly rated reliable data collection methods when assessed. It must be acknowledged that several studies eligible for inclusion in this review did not set out to examine this area of research and retrospectively analysed data for inclusion. There is no consistency on the data reported by each study individually in order to analyse the same outcome measures across all 27 studies. This has been accounted for in analyses to provide the most accurate data possible from a large amount of studies. Large variation was seen across studies in relation to assessment process, treatment pathway and demographic variables.

This systematic review gives information on the population of people presenting to services seeking assistance for their experience of suicidal ideation. Consistency was seen across all but three studies reporting that the presentations of this nature are females for the majority. Other demographic information analysed indicates that single people are more likely to present (42%) but that married people were close in comparison (38%). There was an even spread of people being in employment or unemployed with slightly more reported as in employment while people reported as students was inconsistent. The majority of people came from middle SES backgrounds.

The review highlighted the unclear and inconsistent treatment pathways for this population. A wide variety of assessment was used to determine the patients risk status, most commonly used was the Beck SIS (Beck et al., 1979 ). Only half of studies, 55%, reported using more than one assessment method, including psychosocial interview and questionnaires or medical assessment and psychosocial interview. A large proportion of people (37%) received medical assessment only and no psychological or psychiatric assessment or care. Thirty‐four per cent of people were admitted to hospital, while similar but slightly more were discharged (39%). It is not clear as to how many people received follow‐up care and even less reported on onward referrals to community services, thus highlighting a large gap in the literature and a potential need for future research on the outcomes for these presentations including treatment decisions and follow‐up care pathways.

Consistent with previous research (Goñi‐Sarriés et al., 2018 ; Gvion & Levi‐belz, 2018 ), a previous suicide attempt was a high risk factor identified consistently across studies which is valuable information for provision of care going forward for these presentations. Thirty‐one per cent of people presenting had previous experiences of suicidal ideation. In terms of DSM diagnosis, the most commonly reported diagnosis for people presenting to services was mood disorders consistent across all studies reporting on mental health diagnosis. However, it is worthwhile noting that data indicate that the majority of presentations reporting suicidal ideation are attributing this to psychosocial factors and not mental health disorders—a finding that is both relevant and informative for clinical settings and the role for psychologists to work with people presenting in this way. Exploring this finding further would lead us to question how traditional approaches such as the medical style models are attempting to assess and treat these types of presentations as by history they are medical or psychiatric in nature. However, the data would indicate that life factors, daily stress and crisis in personal circumstances are leading people to present in this way, further indicating how we respond to them may need to be therapeutic in nature and not medically based.

An important finding relates to the use of assessment for suicidal ideation in the hospital setting. Previous research has suggested that suicide risk assessment tools, some of which are discussed in this review, have inadequate reliability and low positive predictive value (Carter et al., 2017 ; Runeson et al., 2017 ). Most instruments were supported by too few studies to allow for the authors to evaluate their accuracy and of those that could be evaluated, not one fulfilled requirement for sufficient diagnostic accuracy. This has clinical implications for the use of these tools in settings such as this. As well as being potentially unreliable in providing valuable information to clinicians, they are time consuming to complete and may not be suitable for fast paced hospital environments.

While a clear picture of the profile of presentations to the ED settings for suicidal ideation can be seen, it is unclear what the best assessment and outcome measures are for this population. Huge variability across settings indicates no clear guidelines or response to this population needs has been established. Future research should consider this for service planning and considering which professionals are best place to intervene and support this populations needs. As mentioned earlier, considering the psychosocial factors contributing to these presentations in the majority of cases, a blended assessment approach for psychiatry and psychology should be considered to meet their needs as a whole.

Considering the findings that mental illness is not reported as the main contributing factor to suicidal ideation, a focus on psychosocial stressors as well as trauma factors as causal for these presentations must be further examined. Interpersonal factors are prevalent as reported reasons for suicidal ideation across all studies reviewed. Importantly, for clinical practice, clinicians need to be asking about trauma at this crucial time and need to be working in a trauma informed manner and considering the life events and journey of the person in front of them when carrying out initial assessments. Further research into this area could highlight important factors to consider when planning next step interventions for these people. A final but important point to note is that research indicates presentations of suicidal ideation to the ED are only representative of a small proportion of people that experience suicidal ideation. The people presenting represent those who engage in ‘help‐seeking’ behaviours, willing to present to services. It is indicated the majority of people do not seek out help and yet still experience suicidal ideation.

4.1. Limitations and recommendations

The following limitations were noted. Where demographic characteristics were reported, there was heterogeneity across participants in terms of age, gender and ethnicity, although White females are highly represented in the review. These findings are consistent with previous research in the area (Runeson et al., 2017 ). With regard to treatment provision, only a small number of studies provided a comprehensive breakdown of the different aspects of the care pathway or specified the medical professionals encountered when attending the ED setting. Methodologically, many studies had small sample sizes to infer results to the larger population as well as data collection methods being rated as low on a quality assessment in some studies. A detailed synthesis was limited by the varying method and data collection seen across studies. This suggests a need for further development of theoretically informed qualitative research and larger scale quantitative research in this subject area. Studies would also benefit from longitudinally tracing changes in patients' lived experiences over time. The ability to generalize the results from this review across different countries and larger populations is questionable. Further research may be needed to support the generalisability of these findings.

Despite the limitations, the review provides insight into the population of hospital presenting suicidal ideation. Valuable information can impact treatment pathway's and outcomes for these people. In conclusion, as initially suggested, the ED setting is a priority for assessing and intervening on presentations of suicidal ideation. While presentations are seen in large numbers across all countries, wide variety of means and demographic characteristics, a streamlined approach to care and management of this population is key to reducing overall presentation numbers and ensuring consistent and effective care for suicidal ideation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There was no funding received for this research. The first author, Emma Fawcett, completed this research as part of her D.Psych.Clin in UCD and is sponsored by the HSE while completing this training. No conflicts of interest were identified.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Open access funding provided by IReL.

Fawcett, E. , & O'Reilly, G. (2022). Hospital presenting suicidal ideation: A systematic review . Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy , 29 ( 5 ), 1530–1541. 10.1002/cpp.2761 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

- Alves, V. M. , Francisco, L. C. , De Melo, A. R. , Novaes, C. R. , Belo, F. M. , & Nardi, A. E. (2017). Trends in suicide attempts at an emergency department . Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria , 39 , 55–61. 10.1590/1516-4446-2015-1833 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Atay, N. M. , Yaman, G. B. , Demġrda, A. F. , & Akpinar, A. (2014). Outcomes of suicide attempters in the emergency unit of a university hospital . Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry , 15 , 124–131. 10.5455/apd.43672 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bazargan‐Hejazi, A. , Ahmadi, A. , Bazargan, M. , Rahmani, E. , Pan, D. , Zahmatkesh, G. , & Teruya, S. (2017). Profile of hospital admissions due to self‐inflicted harm in Los Angeles County from 2001 to 2010 . Journal of Forensic Science , 62 ( 5 ), 1244–1250. 10.1111/1556-4029.13416 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck, A. T. , Kovacs, M. , & Weissman, A. (1979). Assessment of suicidal intention: The scale for suicide ideation . Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 47 , 343–352. 10.1037/0022-006X.47.2.343 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck, A. T. , Schuyler, D. , & Herman, I. (1974). Development of suicidal intent scales. In Beck A. T., Resnik H. L., & Lettieri D. J. (Eds.), The prediction of suicide . Charles Press Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bi, B. , Tong, J. , Liu, L. , Wei, S. , Li, H. , Hou, J. , Tan, S. , Chen, X. , Chen, W. , Jia, X. , Liu, Y. , Dong, G. , Qin, X. , & Phillips, M. (2010). Comparison of patients with and without mental disorders treated for suicide attempts in the emergency departments of four general hospitals in Shenyang, China . General Hospital Psychiatry , 32 , 549–555. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.06.003 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boudreaux, E. D. , Miller, I. , Goldstein, A. B. , Sullivan, A. F. , Allen, M. H. , Manton, A. P. , Arias, S. A. , & Camargo, C. A. (2013). The emergency department safety assessment and follow‐up evaluation (ED‐SAFE): Method and design considerations . Contemporary Clinical Trials , 36 ( 1 ), 14–24. 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.008 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carr, M. J. , Ashcroft, D. M. , Kontopantelis, E. , While, D. , Awenat, Y. , Cooper, J. , Chew‐Graham, C. , Kapur, N. , & Webb, R. T. (2016). Clinical management following self‐harm in a UK‐wide primary care cohort . Journal of Affective Disorders , 197 , 182–188. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.013 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter, G. , Milner, A. , McGill, K. , Pirkis, J. , Kapur, N. , & Spittal, M. J. (2017). Predicting suicidal behaviours using clinical instruments: Systematic review and meta‐analysis of positive predictive values for risk scales . The British Journal of Psychiatry , 210 ( 6 ), 387–395. 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.182717 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ceniti, A. , Heinecke, K. , & McInerney, S. J. (2020). Examining suicide‐related presentations to the emergency department . General Hospital Psychiatry , 63 , 152–157. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.09.006 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crandall, C. , Fullerton‐Gleason, L. , Aguero, R. , & LaValley, J. (2006). Subsequent suicide mortality among emergency department patients seen for suicidal behavior . Academic Emergency Medicine , 13 ( 4 ), 435–442. 10.1197/j.aem.2005.11.072 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cripps, R. A. , Hayes, J. F. , Pitmanb, A. L. , Osbornb, D. P. , & Werbelof, N. (2020). Characteristics and risk of repeat suicidal ideation and self‐harm in patients who present to emergency departments with suicidal ideation or self‐harm: A prospective cohort study . Journal of Affective Disorders , 273 , 358–363. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.130 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fedyszyn, I. E. , Erlangsen, A. , Hjorthoj, C. , Madsen, T. , & Nordentoft, M. (2016). Repeated suicide attempts and suicide among individuals with a first emergency department contact for attempted suicide: A prospective, nationwide, Danish register‐based study . The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry , 77 ( 6 ), 832–840. 10.4088/JCP.15m09793 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- First, M. B. , Gibbon, M. , Spitzer, R. L. W. , Williams, J. B. , & Benjamin, L. S. (1997). Structured clinical interview for DSM‐IV axis II personality disorders, (SCID‐II) . American Psychiatric Association. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldberg, J. F. , Ernst, C. L. , & Bird, S. (2007). Predicting hospitalization versus discharge of suicidal patients presenting to a psychiatric emergency service . Psychiatric Services , 58 ( 4 ), 561–565. 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.561 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goñi‐Sarriés, A. , Blanco, M. , Azcárate, L. , Peinado, R. , & López‐Goñi, J. J. (2018). Are previous suicide attempts a risk factor for completed suicide? Psicothema , 30 ( 1 ), 33–38. 10.7334/psicothema2016.318 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodfellow, B. , Kolves, K. , & de Leo, D. (2018). Contemporary nomenclatures of suicidal behaviors: A systematic literature review . Suicide and Life Threatening Behaviour , 48 , 353–366. 10.1111/sltb.12354 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Griffin, E. , Bonner, B. , O'Hagan, D. , Kavalidou, K. , & Corcoran, P. (2019). Hospital‐presenting self‐harm and ideation: Comparison of incidence, profile and risk of repetition . General Hospital Psychiatry , 61 , 76–81. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.10.009 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gvion, Y. , & Levi‐belz, Y. (2018). Serious suicide attempts: Systematic review of psychological risk factors . Frontiers in Psychiatry , 9 ( 56 ). 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00056 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hamilton, M. (1960). A rating scale for depression . Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry , 23 , 56–62. 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hawton, K. , Saunders, K. , Topiwala, A. , & Haw, C. (2013). Psychiatric disorders in patients presenting to hospital following self‐harm: A systematic review . Journal of Affective Disorders , 151 ( 3 ), 821–830. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.020 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hirayasu, Y. , Kawanishi, C. , Yonemoto, N. , Ishizuka, N. , Okubo, Y. , Sakai, A. , Kishimoto, T. , Miyaoka, H. , Otsuka, K. , Kamijo, Y. , Matsuoka, Y. , & Aruga, T. (2009). A randomized controlled multicenter trial of post‐suicide attempt case management for the prevention of further attempts in Japan (ACTION‐J) . BMC Public Health , 9 ( 1 ), 364. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-364 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kemball, R. S. , Gasgarth, R. , Johnson, B. , Patil, M. , & Houry, D. (2008). Unrecognized suicidal ideation in ED patients: are we missing an opportunity? The American Journal of Emergency Medicine , 26 ( 6 ), 701–705. 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.09.006 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keskin Gokcellia, D. , Tasarb, P. T. , Akcama, N. O. , Sahinb, S. , Akarcac, U. K. , Aktasd, E. O. , Dumane, S. , Akcicekb, F. , & Noyana, A. (2017). Evaluation of attempted older adults suicides admitted to a university hospital emergency department: Izmir study . Asian Journal of Psychiatry , 30 , 196–199. 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.10.002 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim, H. , Kimc, B. , Kim, S. H. , Hyung Keun, C. , Young Kim, E. , & Min Ahn, Y. (2018). Classification of attempted suicide by cluster analysis: A study of 888 suicide attempters presenting to the emergency department . Journal of Affective Disorders , 235 , 184–190. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.001 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim, S. H. , Kim, H. J. , Hoo, S. , & Cha, K. (2020). Analysis of attempted suicide episodes presenting to the emergency department: Comparison of young, middle aged and older people . Int Journal of Mental Health System , 14 , 46. 10.1186/s13033-020-00378-3 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Larkin, G. L. , Smith, R. P. , & Beautrais, A. L. (2008). Trends in US emergency department visits for suicide attempts, 1992–2001 . Crisis , 29 ( 2 ), 73–80. 10.1027/0227-5910.29.2.73 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marriott, R. , Horrocks, J. , House, A. , & Owens, D. (2003). Assessment and management of self‐harm in older adults attending accident and emergency: A comparative cross‐sectional study . International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry , 18 , 645–652. 10.1002/gps.892 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Milner, A. , & De Leo, D. (2010). Who seeks treatment where? Suicidal behaviors and health care: Evidence from a community survey . The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease , 198 , 412–419. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e07905 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Orsolini, L. , Latini, R. , Pompili, M. , Serafini, G. , Volpe, U. , Vellante, F. , Fornaro, M. , Valchera, A. , Tomasetti, C. , Fraticelli, S., Alessandrini, M. , La Rovere, R. , Trotta, S. , Martinotti, G. , Di Giannantonio, M. , & De Berardis, D. (2020). Understanding the complex of suicide in depression: From research to clinics . Psychiatry Investigation , 17 ( 3 ), 207–221. 10.30773/pi.2019.0171 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Page, M. J. , McKenzie, J. E. , Bossuyt, P. M. , Boutron, I. , Hoffmann, T. C. , Mulrow, C. D. , Shamseer, L. , Tetzlaff, J. M. , Akl, E. A. , Brennan, S. E. , Chou, R. , Glanville, J. , Grimshaw, J. M. , Hróbjartsson, A. , Lalu, M. M. , Li, T. , Loder, E. W. , Mayo‐Wilson, E. , McDonald, S. , … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews . BMJ , 372 ( 7 ). 10.1136/bmj.n71 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pavarin, R. M. , Fioritti, A. , Fontana, F. , Marani, S. , Paparelli, A. , & Boncompagni, G. (2014). Emergency department admission and mortality rate for suicidal behavior. A follow‐up study on attempted suicides referred to the ED between January 2004 and December 2010 . Crisis , 35 ( 6 ), 406–414. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perry, I. J. , Corcoran, P. , Fitzgerald, A. P. , Keeley, H. S. , Reulbach, U. , & Arensman, E. (2012). The incidence and repetition of hospital‐treated deliberate self harm: Findings from the worlds first national registry . PLoS ONE , 7 , e31663. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031663 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Posner, K. , Brown, G. K. , Stanley, B. , Brent, D. A. , Yershova, K. V. , Oquendo, M. A. , Currier, G. W. , Melvin, G. A. , Greenhill, L. , Shen, S. , & Mann, J. J. (2011). The Columbia‐suicide severity rating scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults . The American Journal of Psychiatry , 168 ( 12 ), 1266–1277. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Runeson, B. , Odeberg, J. , Pettersson, A. , Edbom, T. , Jildevik Adamsson, I. , & Waern, M. (2017). Instruments for the assessment of suicide risk: A systematic review evaluating the certainty of the evidence . PLoS ONE , 12 ( 7 ), e0180292. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180292 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Skegg, K. (2015). Self‐harm . The Lancet , 336 ( 9495 ), 1471–1483. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stapelberg, N. J. C. , Sveticic, J. , Hughes, I. , & Turner, K. (2020). Suicidal presentations to emergency departments in a large Australian public health service over 10 years . International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 17 , 5920. 10.3390/ijerph17165920 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thomas, B. H. , Ciliska, D. , Dobbins, M. , & Micucci, S. (2004). A process for systematicallyreviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions . Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing , 1 ( 3 ), 176–184. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wei, S. , Lic, H. , Houc, J. , Chenc, W. , Tanc, S. , Chenc, X. , & Qin, X. (2018). Comparing characteristics of suicide attempters with suicidal ideation and those without suicidal ideation treated in the emergency departments of general hospitals in China . Psychiatry Research , 262 , 78–83. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.007 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wei, S. , Liu, L. , Bi, B. , Li, H. , Hou, J. , Chen, W. , Tan, S. , Chen, X. , Jia, X. , Dong, G. , & Qin, X. (2013). Comparison of impulsive and nonimpulsive suicide attempt patients treated in the emergency departments of four general hospitals in Shenyang, China . General Hospital Psychiatry , 35 , 186–191. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.10.015 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Woo, S. , Lee, S. W. , Lee, K. , Seo, W. S. , Lee, J. , Kim, H. C. , & Won, S. (2018). Characteristics of high‐intent suicide attempters admitted to emergency departments . Journal of Korean Medical Science , 8;33 ( 41 ). 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e259 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organisation (WHO) . (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative . WHO. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zeppegno, P. , Gramaglia, C. , Castello, L. M. , Bert, F. , Gualano, M. R. , Ressico, F. , Coppola, I. , Avanzi, G. C. , Siliquini, R. , & Torre, E. (2015). Suicide attempts and emergency room psychiatric consultation . BMC Psychiatry , 15 , 13. 10.1186/s12888-015-0392-2 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang, J. , Jia, S. , Jhiang, C. , & Sun, J. (2006). Characteristics of Chinese suicide attempters: An emergency room study . Death Studies , 30 , 259–268. 10.1080/07481180500493443 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang, J. , & Xu, H. (2007). Degree of suicide intent and the lethality of means employed: A study of Chinese attempters . Archives of Suicide Research , 11 , 343–350. 10.1080/13811110701541889 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Estimated Average Treatment Effect of Psychiatric Hospitalization in Patients With Suicidal Behaviors : A Precision Treatment Analysis

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington

- 2 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, University of South Florida, Tampa

- 3 VA Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care, Portland, Oregon

- 4 Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

- 5 Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention, Canandaigua VA Medical Center, Canandaigua, New York

- 6 Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- 7 Department of Statistics, University of Washington, Seattle

- 8 Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington

- 9 National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts

- 10 Department of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts

- 11 Department of Psychology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- 12 Graduate School of Business, Stanford University, Stanford, California

Question Can development of an individualized treatment rule identify patients presenting to emergency departments/urgent care with suicidal ideation or suicide attempts who are likely to benefit from psychiatric hospitalization?

Findings A decision analytic model found that hospitalization was associated with reduced suicide attempt risk among patients who attempted suicide in the past day but not among others with suicidality. Accounting for heterogeneity, suicide attempt risk was found to increase with hospitalization in 24% of patients and decrease in 28%.

Meaning Results of this study suggest that implementing an individualized treatment rule could identify many additional patients who may benefit from or be harmed by hospitalization.

Importance Psychiatric hospitalization is the standard of care for patients presenting to an emergency department (ED) or urgent care (UC) with high suicide risk. However, the effect of hospitalization in reducing subsequent suicidal behaviors is poorly understood and likely heterogeneous.

Objectives To estimate the association of psychiatric hospitalization with subsequent suicidal behaviors using observational data and develop a preliminary predictive analytics individualized treatment rule accounting for heterogeneity in this association across patients.

Design, Setting, and Participants A machine learning analysis of retrospective data was conducted. All veterans presenting with suicidal ideation (SI) or suicide attempt (SA) from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2015, were included. Data were analyzed from September 1, 2022, to March 10, 2023. Subgroups were defined by primary psychiatric diagnosis (nonaffective psychosis, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and other) and suicidality (SI only, SA in past 2-7 days, and SA in past day). Models were trained in 70.0% of the training samples and tested in the remaining 30.0%.

Exposures Psychiatric hospitalization vs nonhospitalization.

Main Outcomes and Measures Fatal and nonfatal SAs within 12 months of ED/UC visits were identified in administrative records and the National Death Index. Baseline covariates were drawn from electronic health records and geospatial databases.

Results Of 196 610 visits (90.3% men; median [IQR] age, 53 [41-59] years), 71.5% resulted in hospitalization. The 12-month SA risk was 11.9% with hospitalization and 12.0% with nonhospitalization (difference, −0.1%; 95% CI, −0.4% to 0.2%). In patients with SI only or SA in the past 2 to 7 days, most hospitalization was not associated with subsequent SAs. For patients with SA in the past day, hospitalization was associated with risk reductions ranging from −6.9% to −9.6% across diagnoses. Accounting for heterogeneity, hospitalization was associated with reduced risk of subsequent SAs in 28.1% of the patients and increased risk in 24.0%. An individualized treatment rule based on these associations may reduce SAs by 16.0% and hospitalizations by 13.0% compared with current rates.

Conclusions and Relevance The findings of this study suggest that psychiatric hospitalization is associated with reduced average SA risk in the immediate aftermath of an SA but not after other recent SAs or SI only. Substantial heterogeneity exists in these associations across patients. An individualized treatment rule accounting for this heterogeneity could both reduce SAs and avert hospitalizations.

Read More About

Ross EL , Bossarte RM , Dobscha SK, et al. Estimated Average Treatment Effect of Psychiatric Hospitalization in Patients With Suicidal Behaviors : A Precision Treatment Analysis . JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81(2):135–143. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.3994

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Psychiatry in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

July 16, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

reputable news agency

Suicidal ideation, behaviors show no increase with GLP-1 RAs for seniors with type 2 diabetes: Study

by Elana Gotkine

For older adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D), use of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) is not associated with a significantly increased risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors, according to a study published online July 16 in the Annals of Internal Medicine .

Huilin Tang, from the University of Florida College of Pharmacy in Gainesville, and colleagues examined the association between GLP-1 RAs versus sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) or dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (DPP4is) and the risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors among older adults with T2D in two target trial emulation studies using U.S. national Medicare administrative data from January 2017 to December 2020. In each pairwise comparison, new GLP-1 RA users were matched in a 1:1 ratio on propensity score to new users of SGLT2is or DPP4is.

Overall, 21,807 pairs of patients treated with a GLP-1 RA versus an SGLT2i and 21,402 pairs of patients treated with a GLP-1 RA versus a DPP4i were included in the analyses. The researchers found that the hazard ratios of suicidal ideation and behaviors were not significantly different for GLP-1 RAs versus SGLT2is (1.07; 95% confidence interval, 0.80 to 1.45) or for GLP-1 RAs versus DPP4is (0.94; 95% confidence interval, 0.71 to 1.24).

"Among Medicare beneficiaries with T2D, this study found no clear increased risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors with GLP-1 RAs, although estimates were imprecise and a modest adverse effect could not be ruled out," the authors write.

© 2024 HealthDay . All rights reserved.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Research shows spike gene mutations do not correlate with increased SARS-CoV-2 variant severity

Jul 19, 2024

How well does Medicare cover end-of-life care? It depends on what type

Computational tool integrates transcriptomic data to enhance breast cancer diagnosis and treatment

Pandemic health behaviors linked to rise in neonatal health issues

Making clinical guidelines work for large language models

High stress during pregnancy linked to elevated cortisol in toddlers' hair