The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 2: Handling Qualitative Data

- Handling qualitative data

- Introduction

Introduction to transcripts in qualitative research

Understanding the transcription process, practical insights: transcription in action, using transcription services, challenges in transcription.

- Field notes

- Survey data and responses

- Visual and audio data

- Data organization

- Data coding

- Coding frame

- Auto and smart coding

- Organizing codes

- Qualitative data analysis

- Content analysis

- Thematic analysis

- Thematic analysis vs. content analysis

- Narrative research

- Phenomenological research

- Discourse analysis

- Grounded theory

- Deductive reasoning

- Inductive reasoning

- Inductive vs. deductive reasoning

- Qualitative data interpretation

- Qualitative data analysis software

Research transcripts

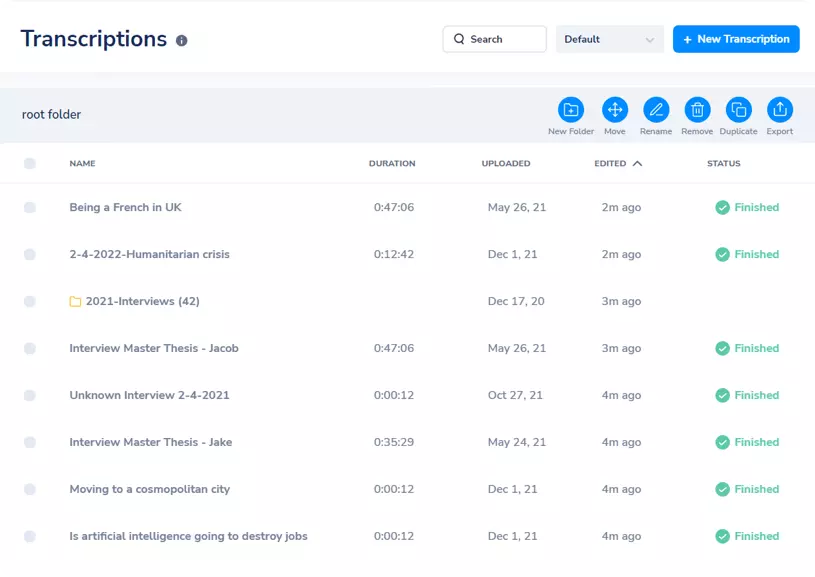

Conducting qualitative interviews or focus groups is only the first part of data collection in a qualitative research project. For most qualitative data analysis , you need to turn those audio or video files into written transcripts. While this may seem self-evident to many researchers, much discussion has taken place about transcripts, best research practices for generating them, the debate between transcription services and human transcription, and so much more.

Qualitative data transcription holds a key role in research , acting as the building blocks from which findings are derived and conclusions are drawn. They are the textual representation of verbal data gathered through interviews , focus groups , and observational studies . Given their significance, it's essential to grasp why they are fundamental to qualitative research.

What is the importance of transcripts in research?

The importance of transcripts in research lies in their ability to convert spoken language into written form, making data analysis significantly more manageable. Transcripts act as the raw material for your analysis , creating a tangible record of the conversations and discussions that form the basis of your research. They provide a precise, detailed account of the verbal data collected, enabling researchers to review the information repeatedly and uncover layers of meaning that might be overlooked when listening to the recording .

Transcripts help researchers systematically organize and manage the data, especially when dealing with large volumes of information. They make it easier to search for specific themes, patterns, or keywords, thereby speeding up the data analysis process. Furthermore, transcripts facilitate the sharing of data among researchers, allowing for collaborative analysis and review. They also ensure the transparency of your research by providing a permanent record that can be scrutinized by other researchers, reviewers, or auditors.

How is transcribing used in qualitative research?

A transcript is used as a way to record and represent the rich, detailed, and complex data collected during qualitative studies such as interviews, focus groups, or observations. Without transcriptions, it would be challenging for researchers to dissect, understand, and interpret the in-depth experiences, perceptions, and opinions shared by the participants. Most research involving audio recordings of interviews requires recordings to undergo the transcription process in order for qualitative data analysis to proceed.

Transcribing, in qualitative research, doesn't merely involve verbatim transcription (the word-for-word rendering of verbal data into text). It can also encompass the translation of non-verbal cues such as laughter, pauses, or emotional expressions that can provide valuable context and insights into the participants' experiences and perspectives. By capturing these details, transcripts can help portray a fuller, more authentic picture of the data, enabling a more comprehensive and nuanced analysis.

In qualitative research, transcriptions are also used for data coding , a process where researchers label or categorize parts of the data based on their content, themes, or patterns. This step is critical for identifying trends and making sense of the data, and having a written transcript makes the coding process significantly more efficient and precise.

How are transcripts used in quantitative research?

Interview transcripts also have an important role in quantitative research , specifically in methods like content analysis and conversation analysis . Content analysis involves the systematic coding and quantifying of data within transcripts, such as the frequency of specific words or themes. This allows researchers to discern patterns and trends and gain insights into the prevalence of certain concepts or attitudes. For example, this could involve quantifying the occurrence of health-related discussions within interviews with healthcare providers.

On the other hand, conversation analysis , while often qualitative, can include quantifiable aspects. Transcripts record details of conversation structure and patterns, such as timing and sequence of speech. Quantitative measures like the count of certain conversational elements or the duration of pauses can be used to understand communication dynamics.

In essence, transcripts are not solely a tool for qualitative research methods but also provide a source of quantitative data and a foundation for quantitative analysis methods. They allow for a detailed, tangible record of spoken data, crucial for both qualitative understanding and quantitative measures, showcasing their versatility in the research field.

The transcription process is a critical stage in qualitative research . It refers to the conversion of recorded or observed speech into written text, turning the fluid and dynamic nature of spoken communication into a tangible and analyzable form . In this section, we will delve deeper into the process of transcription and how it is approached in qualitative research.

How do you create a research transcript?

Writing a research transcript starts with the raw data , usually an audio or video recording from interviews , focus groups , or observations . The first step is to carefully listen to the recording and begin writing down what is being said. This should be done with utmost accuracy, capturing not only the spoken words but also any significant pauses, laughter, or emotional expressions.

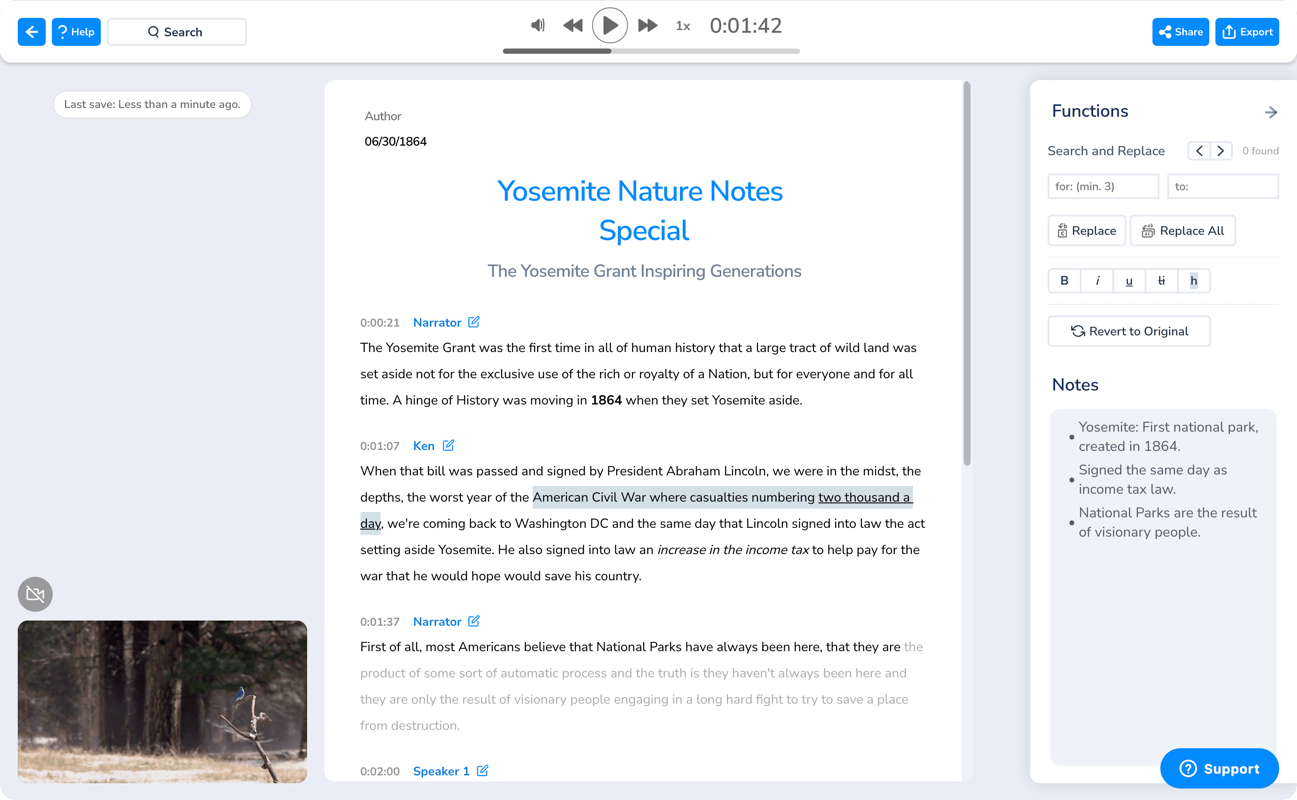

A crucial aspect of writing a transcript is deciding how detailed it should be. This varies depending on the research objectives and the nature of the data. For some research, a verbatim transcription, which includes every utterance, filler words, and non-verbal cues, is necessary. For other studies, a clean verbatim transcript, which omits irrelevant details like repeated words or stutters, is sufficient. After the initial transcription, the transcript should be reviewed and cross-checked with the recording for accuracy. During this revision process, the researcher may also add time stamps, annotations, or comments to enrich the transcript further.

Other details in transcripts

Depending on your research inquiry, you may consider more nuanced approaches to generating transcripts when you require the analysis of complex and multifaceted data. Apart from accurately rendering the spoken words into text, a qualitative research transcript can also capture the context, meaning, and nuances inherent in the spoken interaction.

This could involve noting the tone of voice, pauses, emotional expressions, body language, and interactions among participants. These non-verbal cues can provide rich insights into the participants' attitudes, emotions, and social dynamics, thus giving the researcher a deeper understanding of the data.

One unique aspect of transcribing qualitative data is the reflection and interpretative process embedded in it. Researchers often gain a deeper understanding of the data during transcription, as it forces them to engage closely with the data and notice details that might have been missed during the initial data collection.

How is data transcription done?

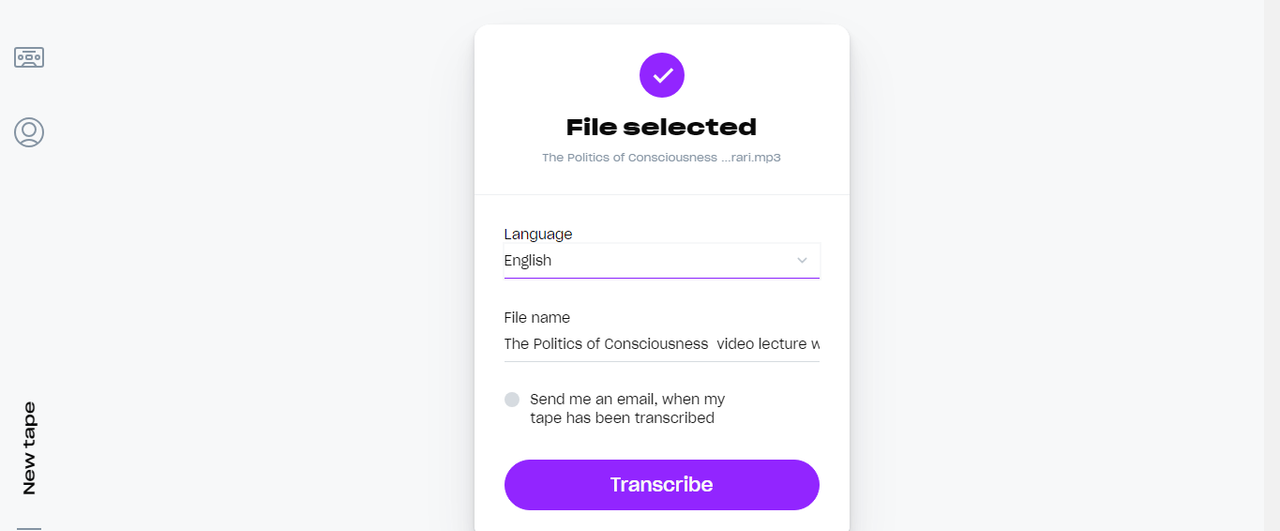

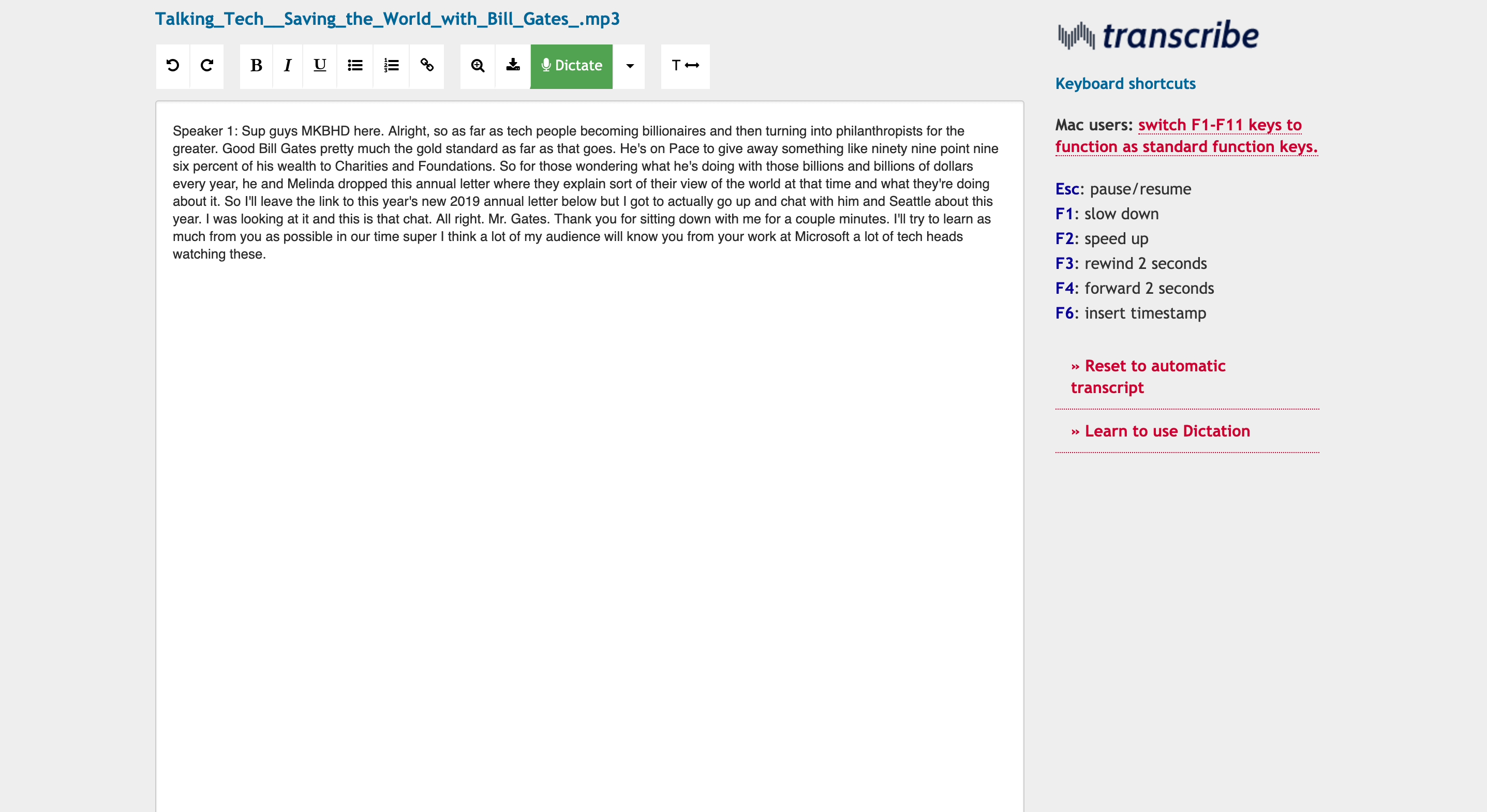

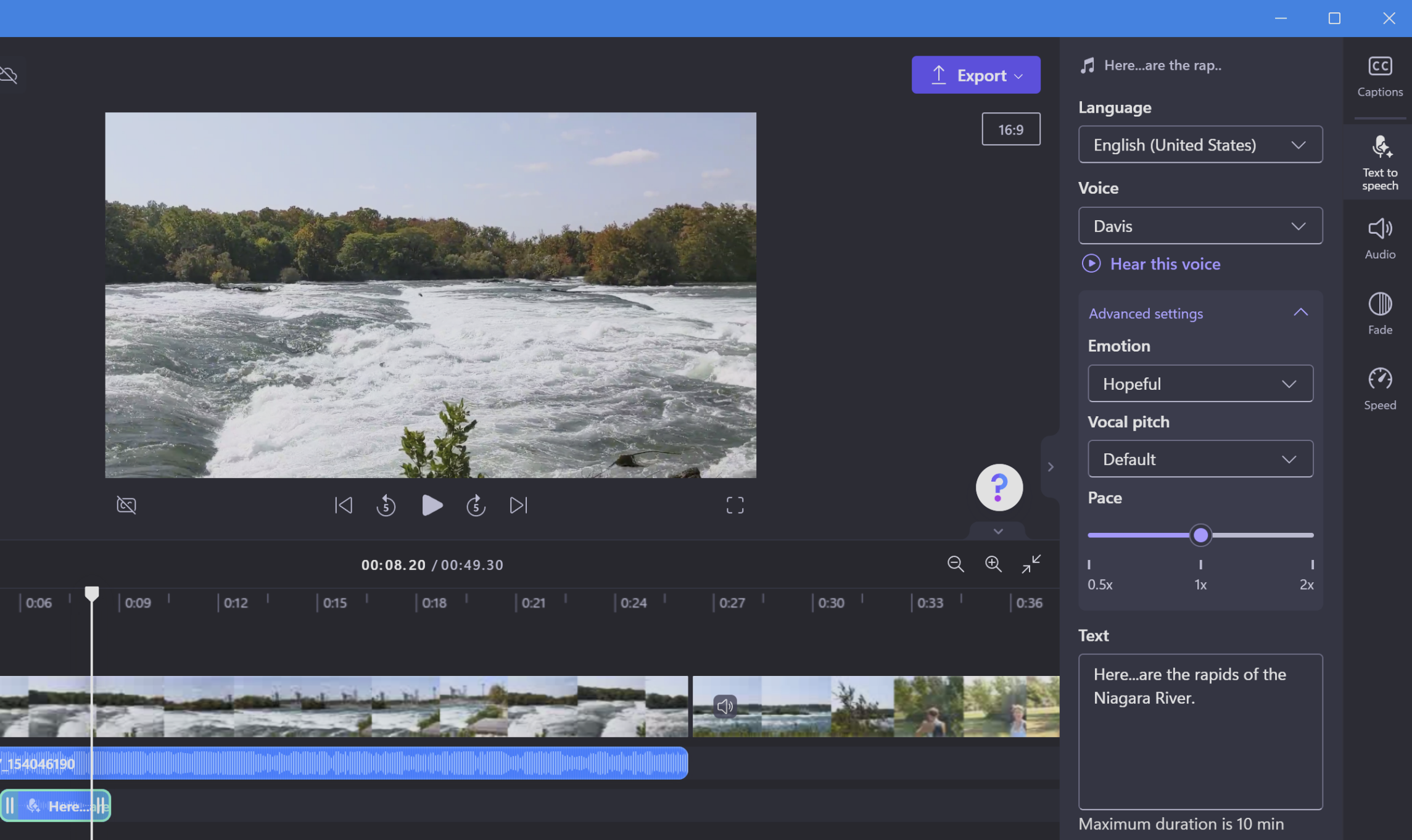

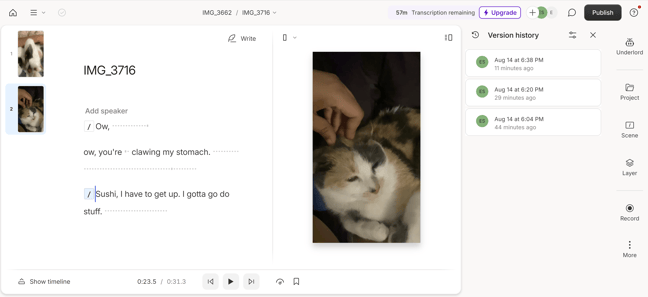

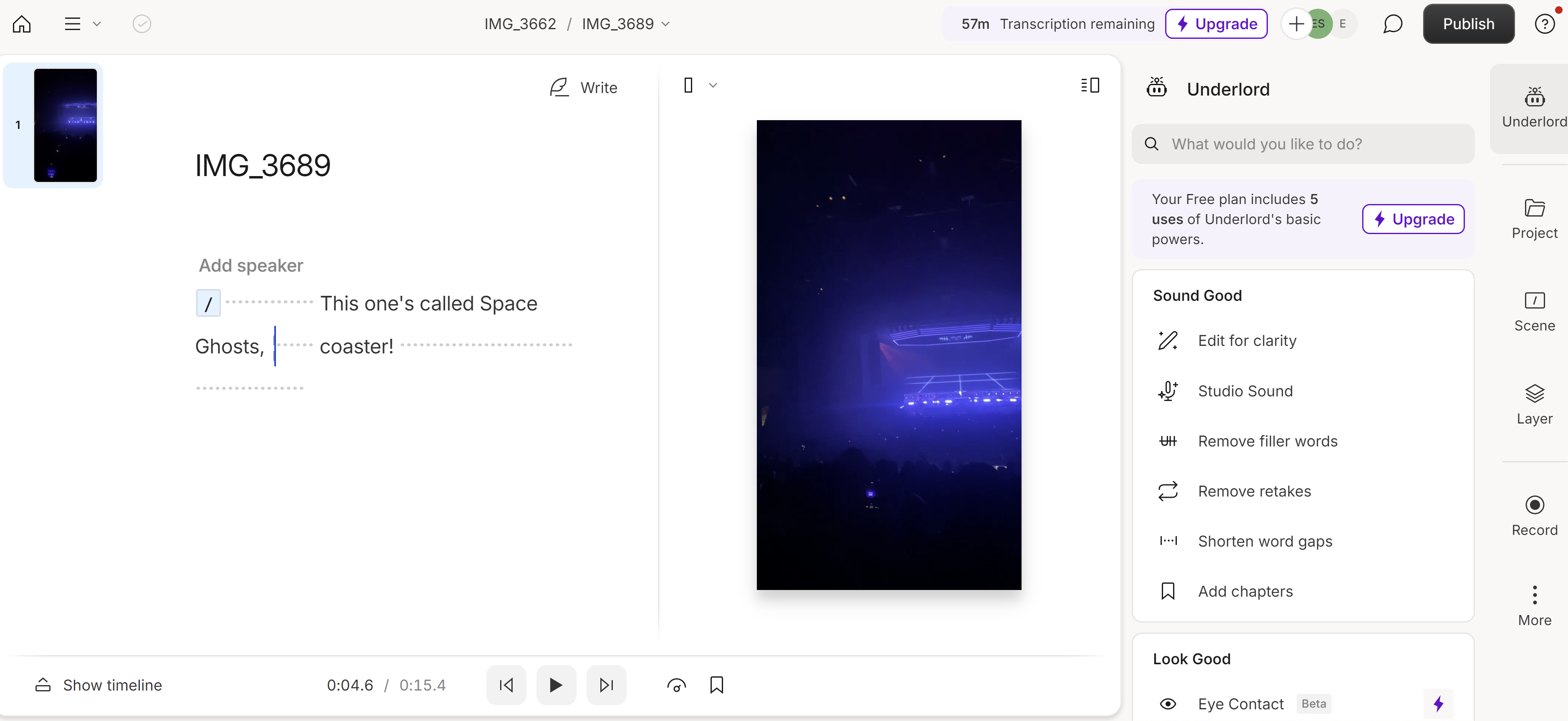

Data transcription can be done manually or with the assistance of transcription software. Manual transcription involves the researcher or a transcriptionist listening to the recording and typing out the conversation. This method is time-consuming but can lead to a higher level of accuracy and deeper immersion in the data.

Automated transcription software, on the other hand, uses automatic speech recognition (ASR) technology to transcribe audio recordings into text. While this method is faster and can handle large volumes of data, it may not be as accurate, especially when dealing with poor audio quality, heavy accents, or technical jargon.

Regardless of the method chosen, the transcribed data should be reviewed and edited for accuracy. This might involve repeated listening to the audio, making corrections, and refining the transcript until it accurately represents the original data.

In summary, the transcription process is a meticulous task that requires careful listening, accurate writing, and thoughtful interpretation. It is an essential step in transforming the raw data into a form suitable for in-depth analysis, thus laying the foundation for your qualitative research findings. By understanding how to write a research transcript, specifically a qualitative research transcript, and knowing how data transcription is done, you'll be well-equipped to handle this critical phase of your qualitative research process.

Types of data transcription in qualitative research

As qualitative data can be diverse and complex, it’s important to understand that not all transcripts are the same. Depending on the research objectives, data characteristics, and the resources available, researchers might opt for different types of transcriptions. Let's delve deeper into these different types and their applicability in qualitative research.

What are the different types of data transcription?

There are generally three main types of data transcription:

1. Verbatim transcription: This is the most detailed form of transcription. It involves transcribing every single word, including filler words (like "um," "uh," and "you know"), false starts, repetitions, and even non-verbal cues such as laughter, pauses, or sighs. Verbatim transcription is often used in research where the manner of speaking or the emotional context is as important as the content itself.

2. Clean verbatim transcription: This type of transcription also captures every word spoken but omits filler words, stutters, and false starts, resulting in a cleaner, more readable transcript. Clean verbatim transcription is usually preferred when the focus is on the content of the speech rather than the style or manner of speaking.

3. Intelligent transcription (or edited transcription): This form of transcription goes a step further in simplifying and clarifying the text. It not only removes filler words and repetitions but also corrects grammatical errors and may even rephrase sentences for clarity. Intelligent transcription is typically used for creating transcripts intended for publication or for audiences who are not directly involved in the research.

What are the different types of transcription in qualitative research?

In qualitative research, the type of transcription used often depends on the nature of the study and the level of detail required in the analysis.

For studies aiming to explore the content of the conversations, clean verbatim or intelligent transcriptions might be sufficient. These types provide a clear and concise account of the spoken data, allowing researchers to easily identify themes and patterns in the content.

However, for studies interested in the nuances of communication, such as sociolinguistic studies or discourse analysis, a verbatim transcription might be more appropriate. This type captures the exact words, speech patterns, and non-verbal cues, thus providing a richer and more authentic representation of the spoken interaction.

Choosing the right type of transcription for your qualitative research is crucial, as it can significantly impact the depth and quality of your data analysis . By understanding the different types of data transcription and their uses in qualitative research, you will be better positioned to make an informed decision that aligns with your research goals.

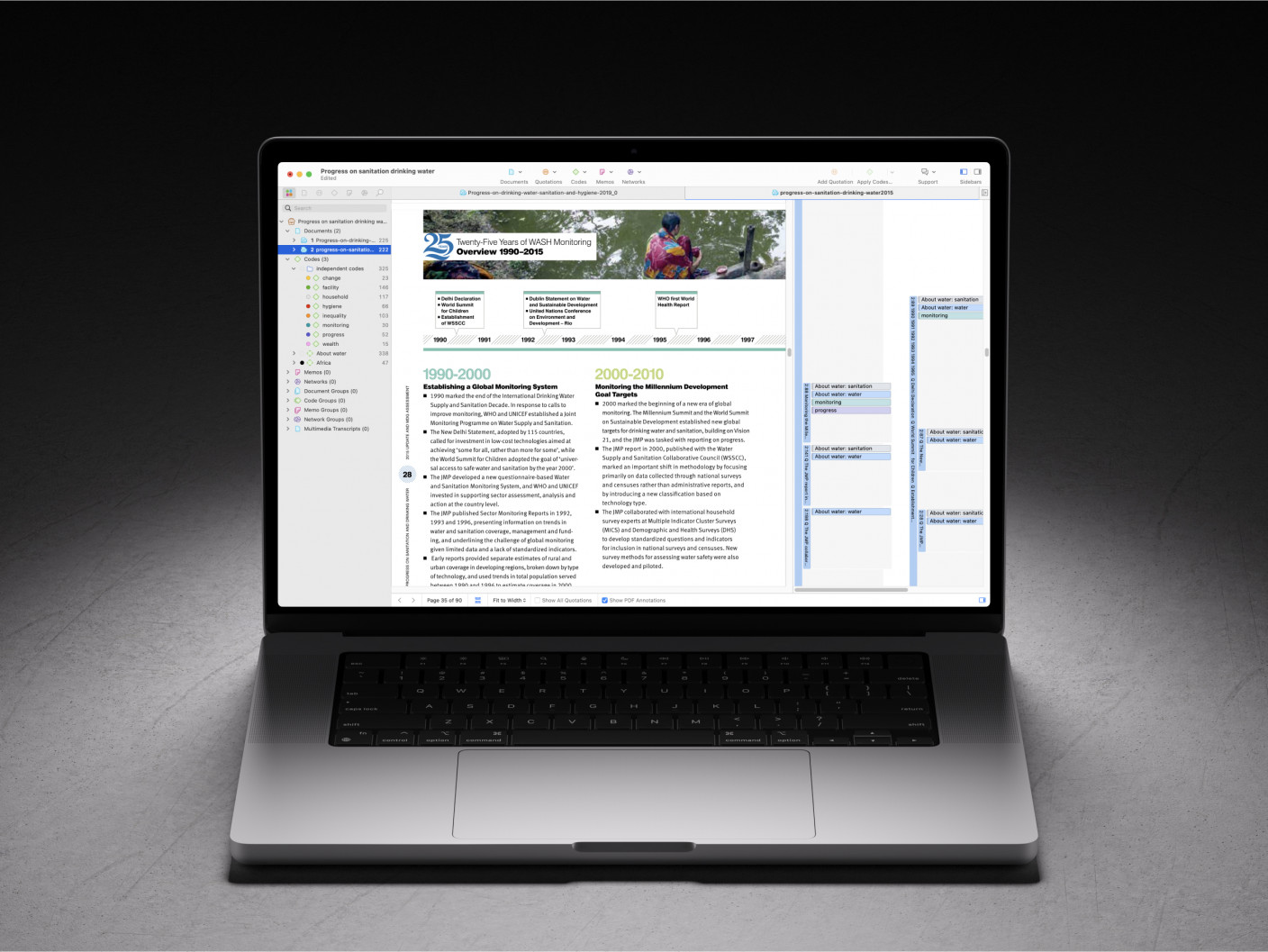

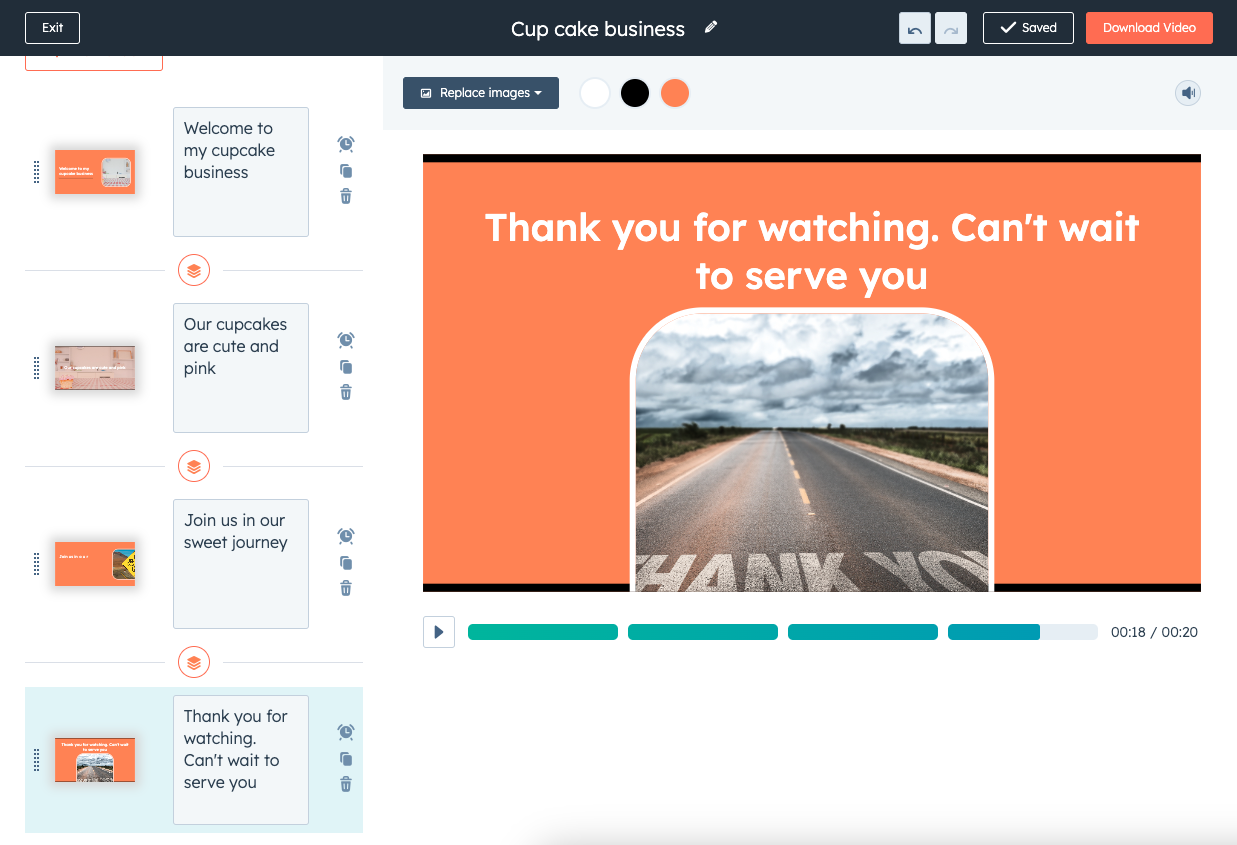

ATLAS.ti makes conducting qualitative research easy

Turn your research data into key insights starting with a free trial of ATLAS.ti.

Transcription is more than a technical process; it's a fundamental part of the journey from data collection to analysis in qualitative research . Understanding transcription in action means knowing how to do it, what to include, and how to record it for optimal use in your study.

What are examples of transcription?

Transcription can take various forms based on the nature of your research. For instance, a sociolinguistic study might require a detailed verbatim transcript, including non-verbal cues and speech anomalies.

Here's an example:

Interviewer: So, how are you feeling about the project? (in a concerned tone) Participant: Umm... Well, (laughs nervously) it's been a bit... um, overwhelming?

On the other hand, an interview transcript for a market research study might be a clean verbatim transcript, focusing on the content. Here's how it could look:

Interviewer: What do you like about our product? Participant: I really enjoy its user-friendly interface and the customer service is exceptional

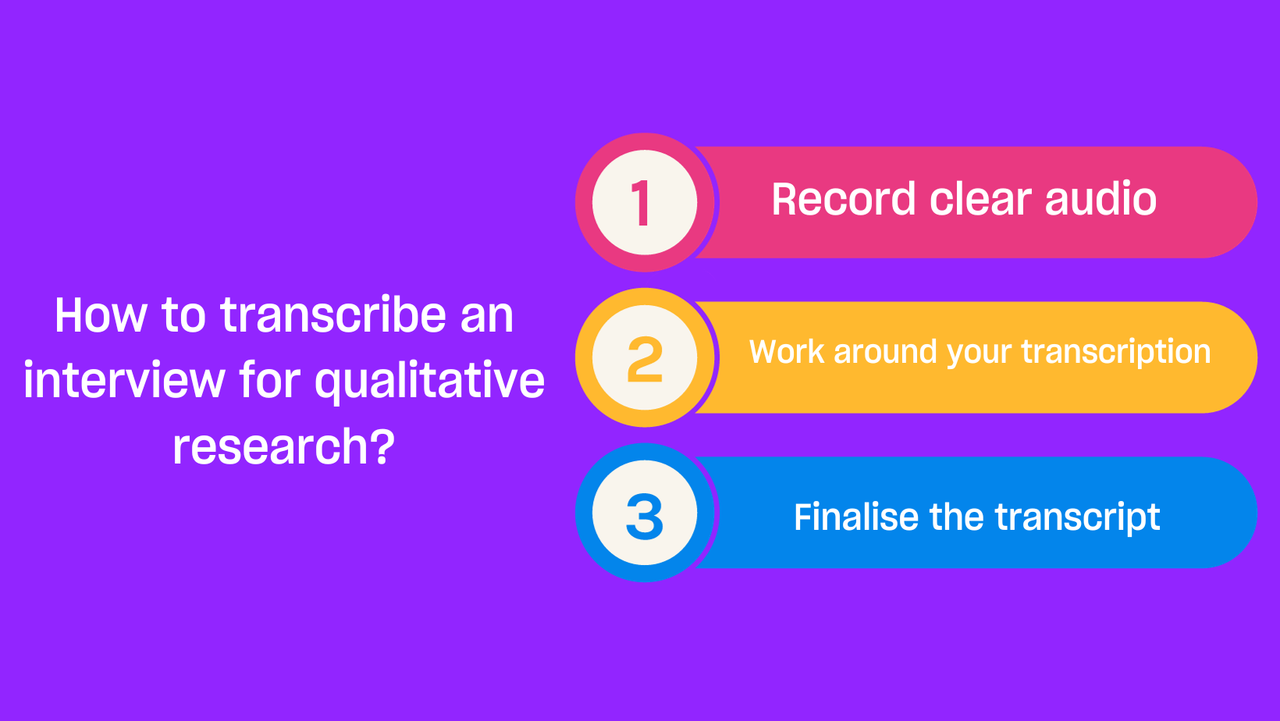

How do you transcribe a research interview?

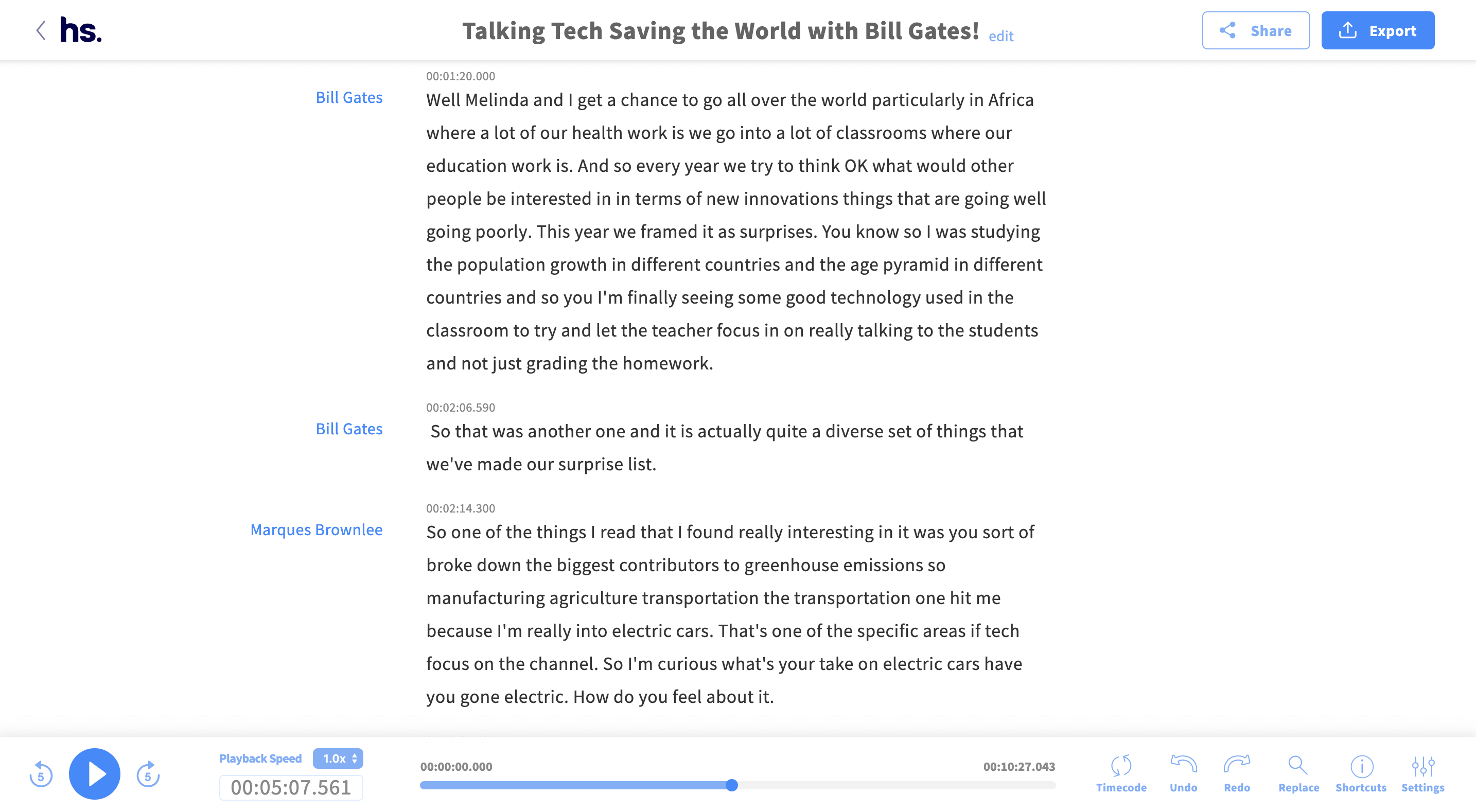

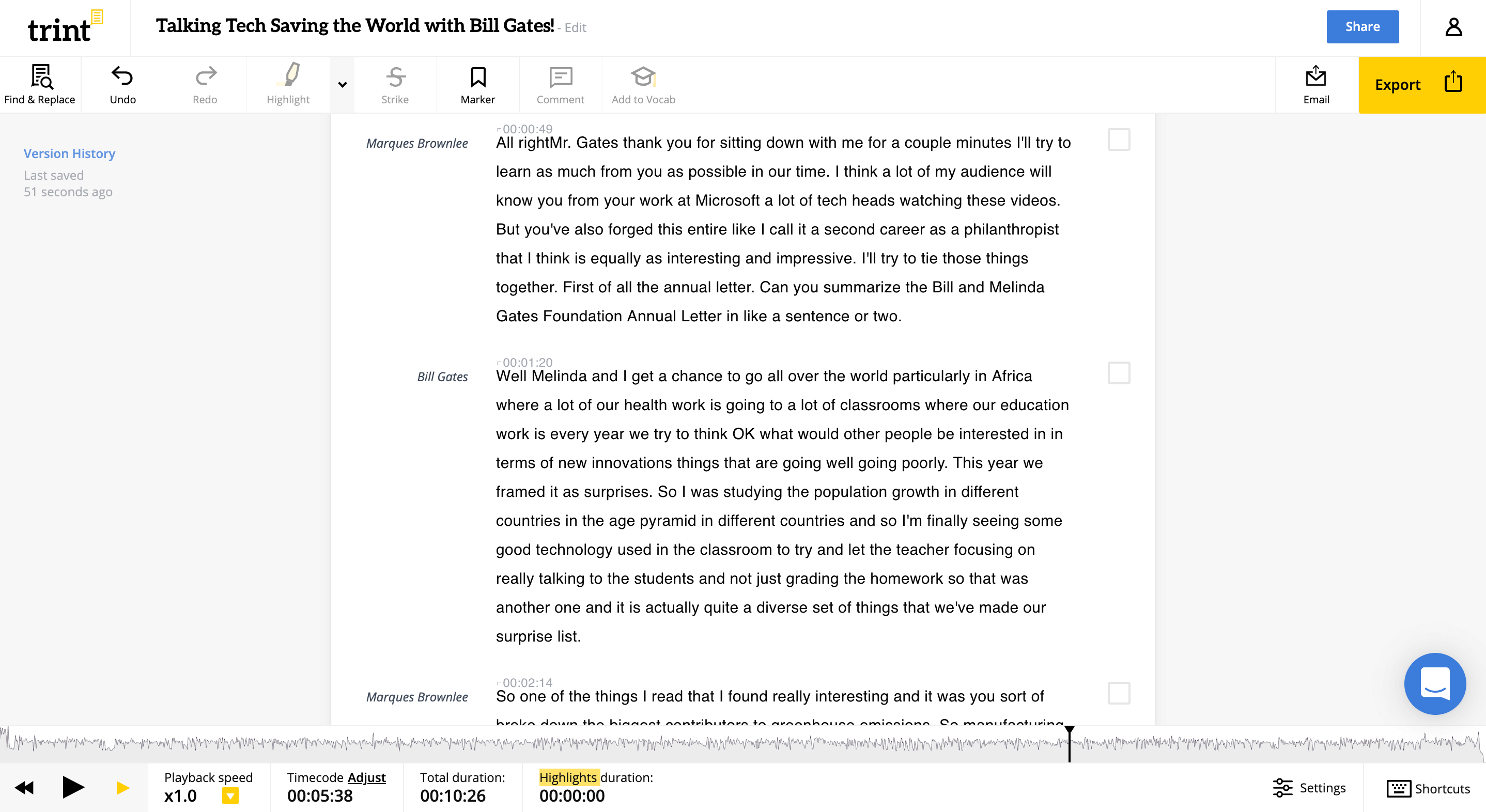

Transcribing a research interview involves several steps. First, ensure you have a good-quality audio or video recording of the interview . Listen to the recording carefully, typing out the conversation verbatim. You can also slow down the speed of the recording, and shortcut keys to rewind the recording a few seconds can be a great help. It's essential to maintain accuracy and include key details that might influence the interpretation of the data , such as significant pauses or emotional inflections.

Depending on your research aims, you may choose to transcribe in verbatim, clean verbatim, or intelligent transcription style. Once the initial transcription is complete, review and cross-check it against the recording for accuracy. Finally, anonymize the data if necessary to ensure participant confidentiality .

What should be included in an interview transcript?

An interview transcript should include everything that is said in the interview, but the level of detail can vary. Here are some elements that are typically included:

1. Identifiers: These help distinguish between different speakers. In the case of an interview, this would usually be the interviewer and the interviewee(s). 2. Verbal responses: All responses to the interview questions should be included in the transcript. 3. Non-verbal cues: Depending on the research objectives, non-verbal cues such as laughter, sighs, or pauses can provide additional context and should be included. 4. Time stamps: These help locate specific parts of the audio recording and can be very helpful during analysis. 5. Annotations: These might include comments or notes made by the transcriber about the context, the tone of voice, or background noises.

How do I record an interview transcript?

Recording an interview transcript starts with creating an audio or video recording of the interview. After the interview, use either manual transcription or automatic transcription software to convert the audio into written text. Make sure to include identifiers for each speaker, their verbal responses, and any relevant non-verbal cues. Review and revise the transcript for accuracy, adding time stamps or annotations as needed.

In summary, transcribing interviews is a meticulous task that requires careful attention to detail and accuracy. By understanding what to include in a transcript and how to record it, you'll be well-equipped to capture the richness and depth of your interview data, laying the groundwork for a robust analysis.

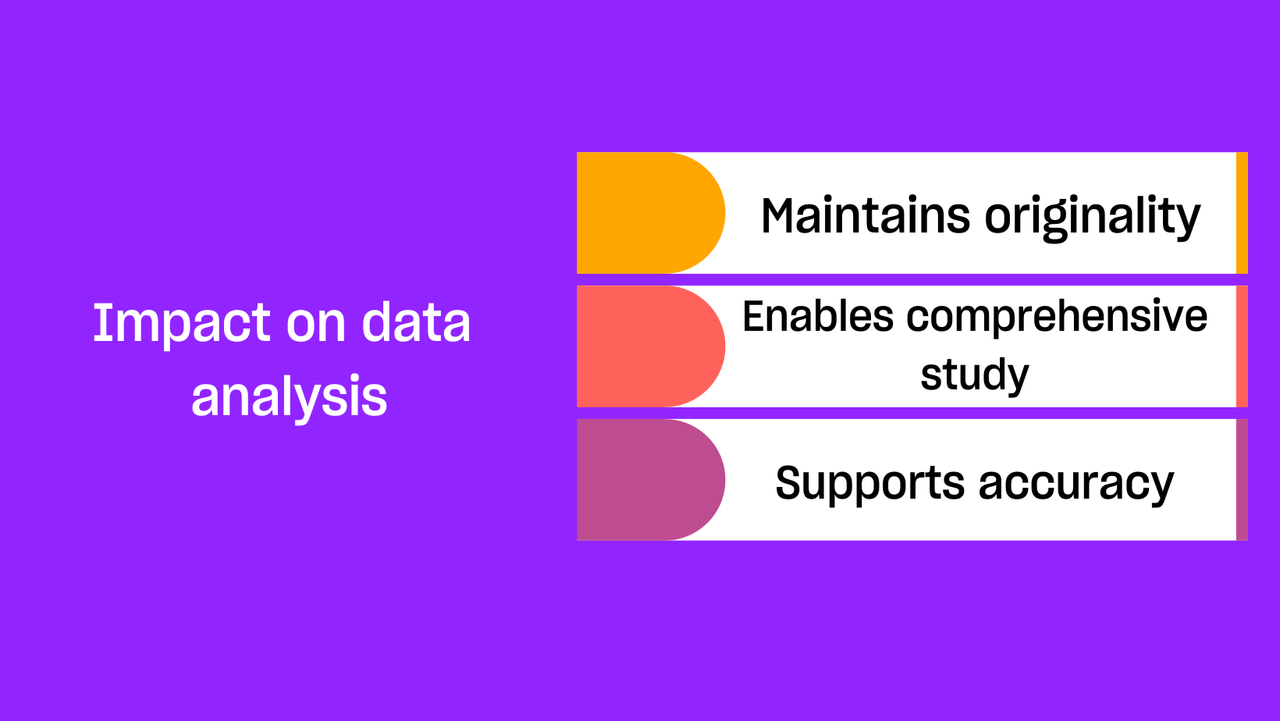

Benefits of transcription in qualitative research

In qualitative research , transcription represents more than a technical or administrative task. It’s the transformative process that turns spoken communication into a tangible, accessible text form that can be critically examined, dissected, and evaluated. This process forms the underpinning of the entire data analysis journey, creating the foundation upon which interpretations are built and conclusions are drawn.

Looking deeper into the benefits of transcription in qualitative research

Unearthing the multiple layers of transcription’s benefits in qualitative research reveals how it contributes to the efficacy and integrity of a study.

1. Facilitating data accessibility: One of the fundamental benefits of transcription is that it brings to life the spoken word, facilitating accessibility. It translates data into a format that is readable, searchable, and conducive to rigorous analysis. Transcripts can be reviewed multiple times, allowing researchers to revisit the data continually. They can be easily shared among team members or other researchers, enhancing the communicability of the study. Transcription also bridges barriers for those who are hearing-impaired or for whom the original language of the conversation might be a hurdle.

2. Enabling comprehensive analysis: Transcripts are the bedrock upon which qualitative analysis is built. They provide the raw material for various methods of qualitative data examination, whether it's the deep dive of a thematic analysis , the linguistic focus of discourse analysis , or the systematic categorization of content analysis . These written records allow researchers to delve into the data, identify recurring patterns, extract significant themes, and uncover insights that might be less discernible or entirely lost in the original audio or video format.

3. Promoting reflection and interpretation: Transcription is far from being a mechanical, dispassionate process. It necessitates active and continual engagement with the data , leading to a process of reflection and interpretation that forms the basis of qualitative analysis. During the act of transcribing, researchers can glean new insights, recognize overlooked details, and begin to make initial interpretations. It's often during this process that the data begin to speak, allowing researchers to discern their meaning and value.

4. Providing evidence and establishing an audit trail: Transcripts constitute a concrete, verifiable record of the data collected, the words expressed by the participants, their sentiments, and their experiences. This record acts as a form of evidence to substantiate the research findings, ensuring their credibility. Furthermore, they provide an audit trail, contributing to the transparency, accountability, and, thus, the overall trustworthiness of the study.

Justifying the use of transcription for qualitative data

The crucial role of transcription in qualitative research is underscored by its ability to capture the richness and multifaceted nature of spoken data and convert it into a format ripe for in-depth analysis. It provides a lens through which subtle nuances of communication - the ebb and flow of conversation, shifts in tone, or emotional expressions - can be understood. This is invaluable in qualitative research, where the aim is to capture and understand the depth and complexity of human experiences.

Transcripts also serve as a durable, enduring record of the data, preserving the words and voices of the participants. They ensure that the insights, stories, and experiences shared by participants are not transient but can be revisited, reviewed, and reinterpreted in future research.

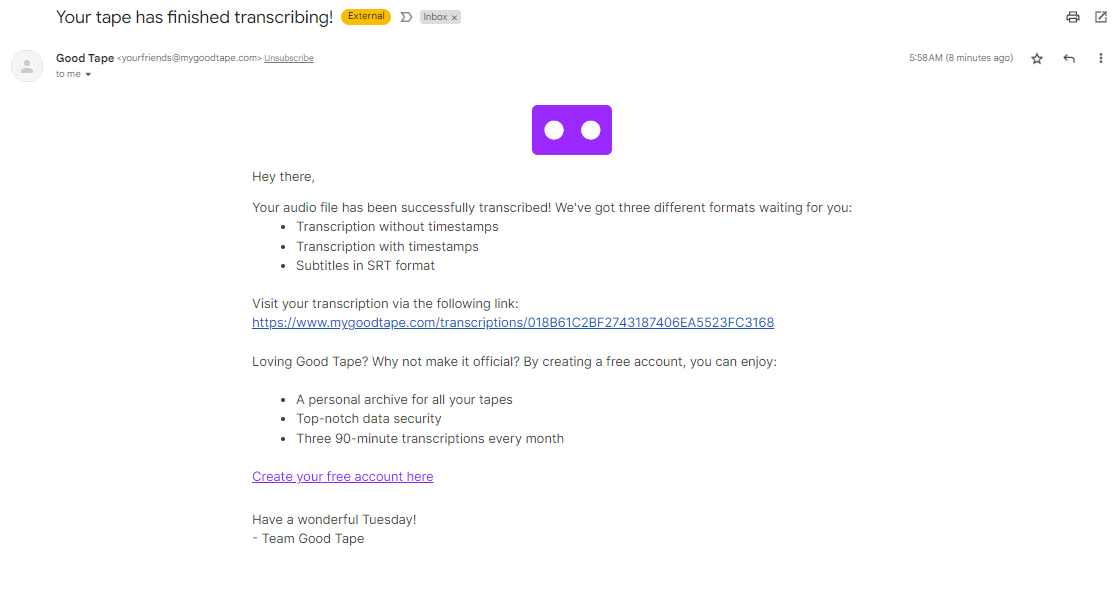

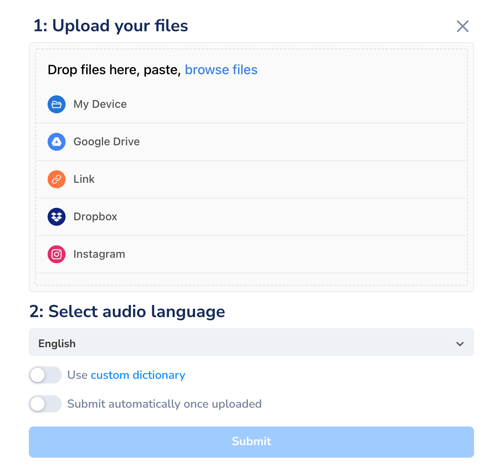

Transcription services have revolutionized the way researchers process their data, offering a range of possibilities from manual transcription to advanced AI-driven software. These services often come with their own benefits and drawbacks, and understanding these is key to making an informed decision for your qualitative research project. This section will delve into the world of transcription services, helping you to explore your options and make the best choice for your research needs.

Types of transcription services

Broadly, transcription services fall into two main categories: human services and automated services.

Human transcription services employ professional transcribers to convert your audio or video files into text. These services often offer high-quality, accurate transcripts, as they benefit from the nuanced understanding and context interpretation abilities of a human transcriber.

Automated transcription services, on the other hand, use speech recognition software to transcribe audio or video files. They are typically faster and less expensive than human transcription services, but their accuracy can vary depending on the quality of the audio and the complexity of the language used.

Advantages and disadvantages of outside services

Choosing between human and automated transcription services often depends on your project's specific needs. Let's delve into some advantages and disadvantages of each.

Advantages of human services

1. Accuracy: Human transcribers can understand context, decipher accents, and make out words in poor-quality audio better than any software, ensuring high-quality transcripts.

2. Personalized service: They offer personalized service with attention to detail, including specific formatting requests or specialized transcription styles.

Disadvantages of human services

1. Time-consuming: Human transcription is slower than automated transcription, which can be an issue for projects with tight timelines.

2. Cost: Human transcription services can be expensive, especially for large volumes of data. Advantages of automated services

1. Speed: Automated services can transcribe audio or video files much faster than human transcribers.

2. Cost: They are usually more affordable than human transcription services, making them a good option for budget-conscious projects.

Disadvantages of automated services

1. Accuracy: While speech recognition technology has improved significantly, it still struggles with accents, poor audio quality, and complex terminology, which may lead to less accurate transcripts.

2. Lack of context: Automated services may not capture nuances in language or understand context the way a human transcriber can.

Tips for choosing the right service

Selecting the right transcription service should be based on the specific needs and constraints of your project. Here are a few tips to guide your choice:

1. Assess your needs: Consider the complexity of your data, the quality of your recordings, your budget, and your timeline.

2. Test the service: If possible, use a short sample of your data to test the service. This can give you a sense of the quality of the transcription and whether it meets your needs.

3. Read reviews: Check out reviews and ratings from other users to gauge the reliability and performance of the service.

These outside services can be a valuable resource in qualitative research, saving you time and effort. By understanding the benefits and drawbacks of human and automated services and evaluating your specific research needs, you can make an informed choice that best supports your research goals.

The transcription process, while invaluable to qualitative research , does not come without its fair share of challenges. The transformation of oral data into written format can be a complicated endeavor, particularly in cases where the audio quality is poor, speakers have heavy accents, or the conversation is filled with technical or specific jargon. Despite these hurdles, there are various strategies that can help you navigate these issues and ensure high-quality, accurate transcripts.

Audio quality

One of the most common challenges in transcription is dealing with poor audio quality. Background noise, low speaking volumes, or unclear pronunciations can make it difficult to distinguish what is being said. It's a good idea to invest in high-quality recording equipment and choose a quiet, controlled environment for your interviews or focus groups. Ensure that all participants speak clearly and loudly enough to be heard. If your data is already collected and the audio quality is poor, consider using noise-canceling software or hiring a professional transcription service that specializes in handling poor-quality audio.

Accents and dialects

Dealing with heavy accents or unfamiliar dialects can be challenging, particularly for automated transcription services that may not be programmed to handle a wide range of accents or dialects. Human transcribers can spend time familiarizing themselves with the accent or dialect to aid their comprehension. In some cases, it may be beneficial to engage a local transcriber who is familiar with the accent or dialect. For automated services, choosing a service that offers multilingual support or can handle a variety of accents can improve the accuracy of your transcripts.

Technical jargon and specific language

Transcribing conversations that include technical jargon, specific terminology, or industry-specific language can be a challenge, especially if the transcriber is not familiar with the terminology. If you are outsourcing your transcription to a human service, providing a glossary of terms to your transcriber can be very helpful. This can include definitions of technical terms, acronyms, or any specific language used in your study. If using an automated service, choose one that has capabilities to learn and adapt to specific terminology.

Time and resources

Transcription can be a time-consuming and resource-intensive process, especially for large volumes of data. Consider using transcription software or outsourcing to a transcription service to save time. If you’re transcribing manually, developing a systematic approach can increase efficiency. This can include using transcription software to speed up or slow down the audio, utilizing keyboard shortcuts, or creating a consistent formatting system.

Choose ATLAS.ti for your interview research

Analyze transcripts for interviews and focus groups with ATLAS.ti. Download a free trial today.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Reasons to publish with us

- About Family Practice

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, what are the aims of the research project, what level of detail is required, who should do the transcribing, what contextual detail is necessary to interpret data, how should data be represented, what equipment is needed, declaration.

- < Previous

First steps in qualitative data analysis: transcribing

Bailey J. First steps in qualitative data analysis: transcribing. Family Practice 2008; 25: 127–131.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Julia Bailey, First steps in qualitative data analysis: transcribing, Family Practice , Volume 25, Issue 2, April 2008, Pages 127–131, https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmn003

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Qualitative research in primary care deepens understanding of phenomena such as health, illness and health care encounters. Many qualitative studies collect audio or video data (e.g. recordings of interviews, focus groups or talk in consultation), and these are usually transcribed into written form for closer study. Transcribing appears to be a straightforward technical task, but in fact involves judgements about what level of detail to choose (e.g. omitting non-verbal dimensions of interaction), data interpretation (e.g. distinguishing ‘I don't, no’ from ‘I don't know’) and data representation (e.g. representing the verbalization ‘hwarryuhh’ as ‘How are you?’).

Representation of audible and visual data into written form is an interpretive process which is therefore the first step in analysing data. Different levels of detail and different representations of data will be required for projects with differing aims and methodological approaches. This article is a guide to practical and theoretical considerations for researchers new to qualitative data analysis. Data examples are given to illustrate decisions to be made when transcribing or assigning the task to others.

Qualitative research can explore the complexity and meaning of social phenomena, 1 , 2 for example patients' experiences of illness 3 and the meanings of apparently irrational behaviour such as unsafe sex. 4 Data for qualitative study may comprise written texts (e.g. documents or field notes) and/or audible and visual data (e.g. recordings of interviews, focus groups or consultations). Recordings are transcribed into written form so that they can be studied in detail, linked with analytic notes and/or coded. 5

Word limits in medical journals mean that little detail is usually given about how transcribing is actually done. Authors' descriptions in papers convey the impression that transcribing is a straightforward technical task, summed up using terms such as ‘verbatim transcription’. 6 However, representing audible talk as written words requires reduction, interpretation and representation to make the written text readable and meaningful. 7 , 8 This article unpicks some of the theoretical and practical decisions involved in transcribing, for researchers new to qualitative data analysis.

Researchers' methodological assumptions and disciplinary backgrounds influence what are considered relevant data and how data should be analysed. To take an example, talk between hospital consultants and medical students could be studied in many different ways: the transcript of a teaching session could be analysed thematically, coding the content (topics) of talk. Analysis could also look at the way that developing an identity as a doctor involves learning to use language in particular ways, for example, using medical terminology in genres such as the ‘case history’. 9 The same data could be analysed to explore the construction of ‘truth’ in medicine: for example, a doctor saying ‘the patient's blood pressure is 120/80’ frames this statement as an objective, quantifiable, scientific truth. In contrast, formulating a patient's medical history with statements such as ‘she reports a pain in the left leg’ or ‘she denies alcohol use’ frames the patient's account as less trustworthy than the doctor's observations. 10 The aims of a project and methodological assumptions have implications for the form and content of transcripts since different features of data will be of analytic interest. 7

Making recordings involves reducing the original data, for example, selecting particular periods of time and/or particular camera angles. Selecting which data have significance reflects underlying assumptions about what count as data for a particular project, for example, whether social talk at the beginning and end of an interview is to be included or the content of a telephone call which interrupts a consultation.

Visual data

Verbal and non-verbal interaction together shape communicative meaning. 11 The aims of the project should dictate whether visual information is necessary for data interpretation, for example, room layout, body orientation, facial expression, gesture and the use of equipment in consultation. 12 However, visual data are more difficult to process since they take a huge length of time to transcribe, and there are fewer conventions for how to represent visual elements on a transcript. 5

Capturing how things are said

The meanings of utterances are profoundly shaped by the way in which something is said in addition to what is said. 13 , 14 Transcriptions need to be very detailed to capture features of talk such as emphasis, speed, tone of voice, timing and pauses but these elements can be crucial for interpreting data. 7

Dr 9: I would suggest yes paracetamol is a good symptomatic treatment, and you'll be fine Pt K: fine, okay, well, thank you very much.

Dr 9: (..) I would suggest (..) yes paracetamol or ibuprofen is a good (..) symptomatic treatment (..) um (.) (slapping hands on thighs) and you'll be fine Pt K: fine (..) okay (.) well (..) (shrugging shoulders and laughing) thank you very much

In the second representation of this interaction, both speakers pause frequently. The doctor slaps his thigh and uses the idiom ‘you'll be fine’ to wrap up his advice giving. In response, Patient K is hesitant and he uses the mitigation ‘well’, shrugs his shoulders and laughs, suggesting turbulence or difficulty in interaction. 15 Although the patient's words seem to indicate agreement, the way these words are said seem to indicate the opposite. 16

Dr 5: So let's just go back to this. So, so you've had this for a few weeks Pt F: yes

Dr 5: .hhh so let's just go back to this (.) so (..) so you've had this for a few w ee ks Pt F: yes (1.0) (left hand on throat, stroking with fingers)

Dr 5: I must ask you (.) why have you come in tod a y because it is a Saturday morning (1.0) it's for u rgent cases only that really have just st a rted Pt F: Yes because it has been troubling me since last last night (left hand still on neck)

This more detailed level of transcribing facilitates analysis of the social relationship between doctor and patient; in this example, the consequences for the doctor–patient interaction of consulting in an urgent surgery with ‘minor’ symptoms. 16

Data must inevitably be reduced in the process of transcribing, since interaction is hugely complex. Decisions therefore need to be made about which features of interaction to transcribe: the level of detail necessary depends upon the aims of a research project, and there is a balance to be struck between readability and accuracy of a transcript. 18

Transcribing is often delegated to a junior researcher or medical secretary for example, but this can be a mistake if the transcriber is inadequately trained or briefed. Transcription involves close observation of data through repeated careful listening (and/or watching), and this is an important first step in data analysis. This familiarity with data and attention to what is actually there rather than what is expected can facilitate realizations or ideas which emerge during analysis. 1 Transcribing takes a long time (at least 3 hours per hour of talk and up to 10 hours per hour with a fine level of detail including visual detail) 5 and this should be allowed for in project time plans, budgeting for researchers’ time if they will be doing the transcribing.

Recordings may be difficult to understand because of the recording quality (e.g. quiet volume, overlaps in speech, interfering noise) and differing accents or styles of speech. Utterances are interpretable through knowledge of their local context (i.e. in relation to what has gone before and what follows), 8 for example, allowing differentiation between ‘I don't, no’ and ‘I don't know'. Interaction is also understood in wider context such as understanding questions and responses to be part of an ‘interview’ or ‘consultation’ genre with particular expectations for speaker roles and the form and content of talk. 19 For example, the question ‘how are you?’ from a patient in consultation would be interpreted as a social greeting, while the same question from a doctor would be taken as an invitation to recount medical problems. 14 Contextual information about the research helps the transcriber to interpret recordings (if they are not the person who collected the data), for example, details about the project aims, the setting and participants and interview topic guides if relevant.

Dr 1: so what are your symptoms since yesterday (..) the aches Pt B: aches ere (..) in me arm (..) sneezing (..) edache Dr 1: ummm (..) okay (..) and have you tried anything for this (.) at all? Pt B: no (..) I ain't a believer of me- (.) medicine to tell you the truth

Although this attempts to represent linguistic variety, using a more literal spelling is difficult to read and runs the risk of portraying respondents as inarticulate and/or uneducated. 20 Even using standard written English, transcribed talk appears faltering and inarticulate. For example, verbal interaction includes false starts, repetitions, interruptions, overlaps, in- and out-breaths, coughs, laughs and encouraging noises (such as ‘mm’), and these features may be omitted to avoid cluttering the text. 18

If talk is mediated via an interpreter, decisions must be made about how to represent translation on a transcript, 8 for example, whether to translate ‘literally’, and then to interpret the meaning in terms of the second language and culture. For example, from French to English, ‘j'ai mal au coeur’ translates literally as ‘I have bad in the heart’, interpreted in English as ‘I feel sick’. Translation therefore adds an additional layer of interpretation to the transcribing process.

Written representations reflect researchers’ interpretations. For example, laughter could be transcribed as ‘he he he', ‘laughter (2 seconds)’, ‘nervous laughter’, ‘quiet laughter’ or ‘giggling’ and these representations convey different interpretations. The layout on paper and labelling also reflect analytic assumptions about data. 20 For example, labelling speakers as ‘patient’ and ‘doctor’ implies that their respective roles in a medical encounter are more salient than other attributes such as ‘man’, ‘mother’, ‘Spanish speaker’ or ‘advice giver’. Talk is often presented in speech turns, with a new line for the next speaker (as in the data examples given), but could also be laid out in a timeline, in columns or in stanzas like poetry, for example. 7 Transcripts are not therefore neutral records of events, but reflect researchers’ interpretations of data.

Presenting quotations in a research paper involves further steps in reduction and representation through the choice of which data to present and what to highlight. There is debate about what counts as relevant context in qualitative research. 21 , 22 For example, studies usually describe the setting in which data were collected and demographic features of respondents such as their age and gender, but relevant contextual information could also include historical, political and policy context, participants’ physical appearance, recent news events, details of previous meetings and so on. 23 Authors’ decisions on which data and what contextual information to present will lead to different framing of data.

Decisions about the level of detail needed for a project will inform whether video or audio recordings are needed. 24 Taking notes instead of making recordings is not sufficiently accurate or detailed for most qualitative projects. Digital audio and video recorders are rapidly replacing analogue equipment: digital recordings are generally better quality, but require computer software to store and process, and digital video files take up huge quantities of computer memory. It is usually necessary to playback recordings repeatedly: a foot-controlled transcription machine facilitates this for analogue audio tapes (see Fig. 1 ) and transcribing software is recommended for digital audio or video files, since this allows synchronous playback and typing (see Fig. 2 ).

Analogue audio recording equipment: dictaphone with microphone and mini-cassette tape and foot-pedal controlled transcription machine with headphones

Digital video recording equipment: video camera with firewire computer lead, mini DV cassette and Transana transcribing software

Representation of audible and visible data into written form is an interpretive process which involves making judgments and is therefore the first step in analysing data. Decisions about transcribing are guided by the methodological assumptions underpinning a particular research project, and there are therefore many different ways to transcribe the same data. Researchers need to decide which level of transcription detail is required for a particular project and how data are to be represented in written form.

Transcribing is an interpretive act rather than simply a technical procedure, and the close observation that transcribing entails can lead to noticing unanticipated phenomena. It is impossible to represent the full complexity of human interaction on a transcript and so listening to and/or watching the ‘original’ recorded data brings data alive through appreciating the way that things have been said as well as what has been said.

Funding: Primary Care Researcher Development award, Department of Health National Coordinating Centre for Research Capacity Development.

Ethical approval: East London and the City Ethical Committee.

Conflict of interest: None.

This paper derives from a PhD thesis written by Julia Bailey entitled ‘Doctor-patient consultations for upper respiratory tract infections: a discourse analysis’, which was supervised by Celia Roberts, Roger Jones and Jane Barlow. Thanks are due to doctors and patients who participated in the project, to practice staff, and to Anne Rouse for her advice on the practicalities of transcribing.

Transcription Conventions

(?) talk too obscure to transcribe.

Hhhhh audible out-breath

.hhh in-breath

[ overlapping talk begins

] overlapping talk ends

(.) silence, less than half a second

(..) silence, less than one second

(2.8) silence measured in 10 ths of a second

:::: lengthening of a sound

Becau- cut off, interruption of a sound

he says. Emphasis

= no silence at all between sounds

LOUD sounds

? rising intonation

(left hand on neck) body conduct

[notes, comments]

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Author notes

- consultation

- primary health care

- qualitative research

- interpretation of findings

Julia Bailey’s article on transcription of qualitative research data caught my attention because she gives the reader valuable advice regarding the theoretical and practical decisions involved in the process of transcription. For example, she emphasized the importance of focusing on the aim of the research project, on proper reduction of original data, on capturing the meaning of verbal and non-verbal interaction, and on the influence of the researcher’s interpretation of raw data on the outcome of the study (1).

Transcription is indeed a crucial process in any qualitative research project as it is the first step in the analysis of raw data. I agree with Bailey that investigators should be very careful with handling this process. I would like to add a few thoughts about the transcription process by reviewing some additional literature sources and by adding a few of my own experiences.

Marshall and Rossman (2) pointed out that we do not speak in paragraphs and do not give signals to researchers about punctuation during a conversation. Thus, transcribing qualitative data is challenging because the transcriber makes judgments and shapes the meaning of the written words. Sofaer (3) emphasized that the analysis and interpretation process should be deliberate and thorough in order to avoid the use of initial impressions. Bradley and Curry (4) discussed the importance of formatting and suggest the labeling of transcripts with a systematic file name and inserting line-numbering so that communication among members of the analysis team is easier, particularly when certain sections of an interview are being discussed later. They also suggest that once a transcript has been prepared, it should be read closely to gain a general understanding of the data. I found it personally quite helpful to read out loud my self-prepared transcripts for several times, which significantly improved my understanding of the qualitative data and also facilitated the subsequent development of coding categories.

Lichtman (5) discussed the issue of transcribing research data collected from a focus group interview with many people (e.g., 10 different voices). She pointed to the difficulty in transcribing those raw data because some people may speak at the same time, some may interrupt, and others may be talking so quietly that it is difficult to understand them. A solution to this problem is to listen and then extract themes rather than to attempt distinguishing one voice from another. I believe this is a good idea.

Transcribing recorded qualitative data is time-consuming and can be quite costly. Most literature sources I read indicate that self- transcribing original data has advantages over hiring a professional transcriber. However, this may not always be possible, particularly when large data sets need to be processed. Seidman (6) pointed out that an advantage of transcribing own tapes is that the investigator comes to know his/her interviews better. In case someone else is hired to transcribe the raw data, Bogdan and Biklen (7) suggest that the investigator should work closely together with the transcriber in order to make sure that the transcription is accurate. More specifically, when a professional transcriber is hired, the investigator should have prepared detailed written instructions for this person. As Seidman (6) puts it: “Writing out the instructions will improve the consistency of the process, encourage the researchers to think through all that is involved, and allow them to share their decision making with their readers at a later point.â€

Another important issue relates to the length of the transcripts. Should everything be transcribed or only certain sections of it? Seidman (6) does not recommend preselecting particular parts of the tape for transcription and omitting others because this could lead to premature judgments about what is important and what is not. I have tried out both ways and came to the same conclusion.

The term “transcription†is well known in biology. In this scientific discipline, it relates to “gene-transcription,†a process that can be defined as using the DNA as a template in order to make RNA strands (the transcripts) from it (8). If the genes encoded in the DNA are not accurately transcribed, the deciphering of the transcripts will be difficult and may result in improper protein synthesis. This, in turn, can significantly impact cellular functions. I suggest that we recognize the significance of “accurate gene transcription†in biology and adopt it to the field of qualitative research. Accurate “qualitative data transcription†will allow us to obtain a readable text that has important meaning and can help us solve complex social phenomena, including those related to medicine, public health, and education.

1. Bailey J. First steps in qualitative data analysis: transcribing. Fam Pract. 2008; 25: 127-131.

2. Marshall C, Rossman GB. Designing Qualitative Research. 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2006.

3. Sofaer S. Qualitative research methods. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002; 14: 329-336.

4. Bradley EH, Curry LA. Codes to theory: a critical stage in qualitative analysis. In: Curry L, Shield R, Wetle T (eds.). Improving Aging and Public Health Research: Qualitative and Mixed Methods. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, 2006: 91-102.

5. Lichtman M. Qualitative Research in Education: A User’s Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2006.

6. Seidman I. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences. 3rd edn. New York, NY: Teachers College Press, 2006.

7. Bogdan RC, Biklen SK. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theories and Methods. 5th edn. Boston, MA: Pearson Education, 2007.

8. Starr C. Basic Concepts in Biology. 6th edn. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brook/Cole, 2006.

Conflict of Interest:

None declared

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| November 2016 | 109 |

| December 2016 | 49 |

| January 2017 | 546 |

| February 2017 | 3,448 |

| March 2017 | 4,426 |

| April 2017 | 2,135 |

| May 2017 | 833 |

| June 2017 | 357 |

| July 2017 | 346 |

| August 2017 | 359 |

| September 2017 | 566 |

| October 2017 | 725 |

| November 2017 | 915 |

| December 2017 | 3,185 |

| January 2018 | 4,020 |

| February 2018 | 4,323 |

| March 2018 | 5,999 |

| April 2018 | 6,176 |

| May 2018 | 5,891 |

| June 2018 | 4,049 |

| July 2018 | 3,921 |

| August 2018 | 4,915 |

| September 2018 | 4,080 |

| October 2018 | 4,515 |

| November 2018 | 5,199 |

| December 2018 | 3,997 |

| January 2019 | 3,982 |

| February 2019 | 4,672 |

| March 2019 | 6,472 |

| April 2019 | 6,753 |

| May 2019 | 5,986 |

| June 2019 | 4,702 |

| July 2019 | 4,482 |

| August 2019 | 4,168 |

| September 2019 | 3,722 |

| October 2019 | 3,855 |

| November 2019 | 3,376 |

| December 2019 | 2,449 |

| January 2020 | 2,729 |

| February 2020 | 3,114 |

| March 2020 | 2,853 |

| April 2020 | 1,912 |

| May 2020 | 1,940 |

| June 2020 | 2,202 |

| July 2020 | 2,176 |

| August 2020 | 1,957 |

| September 2020 | 1,940 |

| October 2020 | 2,479 |

| November 2020 | 2,767 |

| December 2020 | 2,069 |

| January 2021 | 2,306 |

| February 2021 | 2,755 |

| March 2021 | 3,507 |

| April 2021 | 3,294 |

| May 2021 | 3,152 |

| June 2021 | 3,065 |

| July 2021 | 2,605 |

| August 2021 | 2,527 |

| September 2021 | 2,709 |

| October 2021 | 3,206 |

| November 2021 | 3,475 |

| December 2021 | 2,703 |

| January 2022 | 2,912 |

| February 2022 | 3,245 |

| March 2022 | 4,345 |

| April 2022 | 4,942 |

| May 2022 | 5,015 |

| June 2022 | 3,722 |

| July 2022 | 2,842 |

| August 2022 | 3,281 |

| September 2022 | 3,307 |

| October 2022 | 3,657 |

| November 2022 | 3,966 |

| December 2022 | 3,472 |

| January 2023 | 3,921 |

| February 2023 | 4,042 |

| March 2023 | 5,072 |

| April 2023 | 5,478 |

| May 2023 | 5,928 |

| June 2023 | 4,415 |

| July 2023 | 3,277 |

| August 2023 | 3,142 |

| September 2023 | 2,919 |

| October 2023 | 3,611 |

| November 2023 | 4,207 |

| December 2023 | 3,753 |

| January 2024 | 3,939 |

| February 2024 | 3,814 |

| March 2024 | 5,149 |

| April 2024 | 5,687 |

| May 2024 | 4,920 |

| June 2024 | 2,482 |

| July 2024 | 2,100 |

| August 2024 | 1,131 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2229

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

University Library

Qualitative Data Analysis: Transcription

- Atlas.ti web

- R for text analysis

- Microsoft Excel & spreadsheets

- Other options

- Planning Qual Data Analysis

- Free Tools for QDA

- QDA with NVivo

- QDA with Atlas.ti

- QDA with MAXQDA

- PKM for QDA

- QDA with Quirkos

- Working Collaboratively

- Qualitative Methods Texts

- Transcription

- Data organization

- Example Publications

Transcription as an Act of Analysis

While transcription is often treated as part of the data collection process, it is also an act of analysis (Woods, 2020). When you manually transcribe an interview, for example, you make choices about how to turn the recording of the interview into text, and these decisions shape the analysis you conduct.

For example, if you host a focus group, a transcription that just includes the words spoken by the participants loses data about the interaction between them. You may decide to ensure that your transcription includes details on interactions (which would take more time or resources) or decide that interaction information is not relevant to your analysis. This decision is influenced by your methodology and research goals, and should be recognized as a part of your analysis process.

Planning and communicating the transcription process is further complicated when the researcher works in a research team, asks participants to discuss sensitive topics, occurs in a cross-cultural environment, or when the transcript must be translated into another language (Clark et al, 2017). Published research reports rarely include significant detail about the transcription process, but if you find yourself in one of these situations, it may be worth seeking works in your discipline that address best practices for transcription, data management, participant relationships, and translation, such as Clark et al's (2017) work on developing a transcription and translation protocol for sensitive and cross-cultural team research.

Transcription Tools

- Atlas.ti (Mac)

- Atlas.ti (Windows)

- NVivo (Windows)

- NVivo (Mac)

- Kaltura/Mediaspace

- Free transcription tools

- Paid transcription services

- Importing automatic transcripts into Atlas.ti (Mac) You can import transcripts and media files from Zoom, Teams, and other video meeting platforms. Atlas.ti links the video and automatic transcript, which allows you to watch the video and edit the transcript right in Atlas.

- Creating transcripts in Atlas.ti You can import media files to Atlas.ti and then create your own transcript within the program. This process will create a transcript that is synced with the media file.

- Link a transcript to media in Atlas.ti You can import existing media and transcripts to Atlas.ti in order to link them together and enable synchronous viewing of the media with links to the transcript.

- Importing automatic transcripts into Atlas.ti (Windows) You can import transcripts and media files from Zoom, Teams, and other video meeting platforms. Atlas.ti links the video and automatic transcript, which allows you to watch the video and edit the transcript right in Atlas.

- Create a transcript in Atlas.ti You can import media files to Atlas.ti and create your own transcript within the program. The transcript will be linked to the media for synchronous scrolling.

- Link a transcript to a media file If you transcript text already, you can upload a media file to Atlas.ti and link the text. This will allow you to use synchronized scrolling, which shows you the video and transcript at the same time.

- Create transcripts in NVivo You can create new transcriptions of media in your NVivo project using the edit mode.

- Import and link transcripts in NVivo Existing transcripts can be imported to NVivo and link the transcript with a media file.

The MAXQDA is the same across Mac and Windows devices.

- Manual Transcription You can upload media files to MAXQDA and then create new transcripts using the Multimedia Browser.

- Link transcripts to a media file by creating timestamps If you already have transcript text, you can use the edit mode in MAXQDA to create timestamps and sync the transcript to the media file.

- Automatic transcription New to MAXQDA 24, you can now automatically transcribe your media.

- Downloading captions from Kaltura Video files you upload to Kaltura (including recorded Zoom meetings) are automatically captioned, though you'll need to edit the captions and publish them before they appear on your video. Once the file is created, you can download it from Kaltura to upload to other programs. See this page on captions in Kaltura for more information.

- Find and replace text in Word When you download captions from Zoom or Kaltura, it will come with timestamps. You can use the find and replace feature in Word to clear the timestamps for easier editing.

- OTranscribe OTranscribe is a free, open-source and web browser based tool for transcribing audio and video. You can upload media and use the tool to create citations. See the help pages for information.

- Google Docs Voice Typing You can use the voice typing feature to create rough transcriptions of audio as you collect data or by re-playing a recording into the microphone.

- Microsoft Word Dictate Typing Web and desktop versions of Microsoft Word include a dictation tool that will create a rough transcription while you collect data or when you play a recording near your device's microphone.

There are companies that will create transcripts from media files on your behalf, usually for a by-minute fee.

If you decide to use one of these options, you should ensure that the security of data shared with these services is in compliance with your IRB protocol and consent obtained from any participants.

Do you have experience with any paid transcription services that you think would be worth adding to this list? Please share your experience with me .

- NVivo Transcription NVivo offers a paid transcription service, which can be purchased as a paid subscription or a pay-as-you-go service. Transcription is available in 43 languages including English, Spanish, Japanese, Hindi, Arabic and Korean.

- Rev Ref offers both automatic, rough transcription as well as more accurate transcription conducted by workers. Rev supports 58+ languages including English, Spanish, Arabic, Mandarin, Japanese, Korean, and Hindi.

- Trint Trint is a paid transcription and analysis tool, with transcription available for 40+ languages , including English, Spanish, Chinese Mandarin, Korean, Hindi, and Korean. Trint also offers translation of text.

Cited on this page

Clark, L., Birkhead, A. S., Fernandez, C., & Egger, M. J. (2017). A transcription and translation protocol for sensitive cross-cultural team research . Qualitative Health Research , 27 (12), 1751–1764. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317726761

Woods, D. Presentation in: Christina Silver, Phd. (2020, December 4). CAQDAS webinar 005 Transcription as an analytic act. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7X-s1r4l0QQ.

- << Previous: Qualitative Data Analysis Strategies

- Next: Data organization >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2024 5:06 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.illinois.edu/qualitative

Transcription and Qualitative Methods: Implications for Third Sector Research

- Research Papers

- Published: 10 September 2021

- Volume 34 , pages 140–153, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Caitlin McMullin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7029-9998 1

78k Accesses

68 Citations

21 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

While there is a vast literature that considers the collection and analysis of qualitative data, there has been limited attention to audio transcription as part of this process. In this paper, I address this gap by discussing the main considerations, challenges and implications of audio transcription for qualitative research on the third sector. I present a framework for conducting audio transcription for researchers and transcribers, as well as recommendations for writing up transcription in qualitative research articles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Transcription and Data Management

Longform recordings of everyday life: Ethics for best practices

From voice to ink (Vink): development and assessment of an automated, free-of-charge transcription tool

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The field of third sector studies is inherently interdisciplinary, with studies from political science, management, sociology and social work, among others. Within the field of research, a large percentage (between 40–80%) of studies employ qualitative methods such as interviews, focus groups and ethnographic observations (von Schnurbein et al., 2018 ). In order to ensure rigor, qualitative researchers devote considerable time to developing interview guides, consent forms and coding frameworks. While there is a vast literature that considers the collection and the analysis of qualitative data, there has been comparatively limited attention paid to audio transcription, which is the conversion of recorded audio material into a written form that can be analyzed. Despite advances made in qualitative methodologies and increasing attention to positionality, subjectivity and reliability in qualitative data analysis, the transcription of interviews and focus groups is often presented uncritically as a direct conversion of recorded audio to text. As technology to facilitate transcription improves, many researchers have shifted to using voice-to-text software and companies that employ AI rather than human transcription. These technological advances in transcription, along with shifts in the way that research is undertaken (for example, increasingly via video conferencing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic), mean that the need to critically reflect upon the place of transcription in third sector research is more urgent.

In this article, I explore the place of transcription in qualitative research, with a focus on the importance of this process for third sector researchers. The article is structured as follows. First, I review the qualitative methods literature on audio transcription and the key themes that arise. Next, I report on a review undertaken of recent qualitative research articles in Voluntas and the way that authors discuss transcription in these articles. Finally, I propose a framework for qualitative third sector researchers to include transcription as part of their research design and elements to consider in including descriptions of the transcription process in writing up qualitative research.

Audio Transcription: What We Know

At a basic level, transcription refers to the transformation of recorded audio (usually spoken word) into a written form that can be used to analyze a particular phenomenon or event (Duranti, 2006 ). For many qualitative researchers, transcription has become a fairly taken-for-granted aspect of the research process. In this section, I review the methods literature on the process of audio (and video) transcription as part of qualitative research on the third sector, focusing on three key areas—how transcription is undertaken, epistemological and ethical considerations, and the role of technology.

Qualitative research and transcription

While quantitative research seeks to explain, generalize and predict patterns through the analysis of variables, qualitative research questions are more interested in understanding and interpreting the socially constructed world around us (Bryman, 2016 ). This means that data are collected through documents, observation and interviews, and the latter are often recorded in order to analyze these as documents. For third sector research, recordings are most commonly made of interviews and focus groups, but may also be of meetings, events and other activities to ensure that researchers do not have to rely on their power of recall or scribbled notes.

Transcription is a notoriously time-consuming and often tedious task which can take between three hours and over eight hours to transcribe one hour of audio, depending on typing speed. Transcription is not, however, a mechanical process where the written document becomes an objective record of the event—indeed, written text varies from the spoken word in terms of syntax, word choice and accepted grammar (Davidson, 2009 ). The transcriber therefore has to make subjective decisions throughout about what to include (or not), whether to correct mistakes and edit grammar and repetitions. This has been described as a spectrum between “naturalized” transcription (or “intelligent verbatim”) which adapts the oral to written norms, and “denaturalized” transcription (“full verbatim”), where everything is left in, including utterances, mistakes, repetitions and all grammatical errors (Bucholtz, 2000 ).

While some contend that denaturalized transcription is more ‘accurate’, the same can equally be argued for naturalized, as it allows the transcriber to omit occasions when, for instance, an individual mis-speaks and corrects themselves, thereby allowing the transcriber to record closer to what was intended and how the interviewee might have portrayed themselves in a written form. As Lapadat ( 2000 , p. 206) explains, “Spoken language is structured and accomplished differently than written text, so when talk is re-presented as written text, it is not surprising that readers draw on their knowledge of written language to evaluate it.” Other nonverbal cues, such as laughter, tone of voice (e.g. sarcasm, frustration, emphasis) and the use or omission of punctuation, can also drastically alter the meaning or intention of what an individual says. In addition, the transcriber must make decisions about how much contextual information to include, such as interruptions, crosstalk and inaudible segments (Lapadat, 2000 ). Because of the range of types of research that employ qualitative methods, there is no single set of rules for transcription but rather these decisions must be based on the research questions and approach.

Epistemological and Ethical Considerations

Because the researcher (or external transcriber) must make these decisions as they translate audio into written text, transcription is an inherently interpretative and political act, influenced by the transcriber’s own assumptions and biases (Jaffe, 2007 ). Every choice that the transcriber makes therefore shapes how the research participant is portrayed and determines what knowledge or information is relevant and valuable and what is not. Indeed, two transcribers may hear differently and select relevant spoken material differently (Stelma & Cameron, 2007 ). As Davidson ( 2009 ) notes (and as I explore in further detail in the next section), despite being a highly interpretive process, transcription is frequently depicted using positivist norms of knowledge creation.

Transcription also involves potential ethical considerations and dilemmas. When working with disadvantaged communities, deciding how to depict research participants in written text can highlight the challenges of ethical representation. As Kvale ( 1996 , pp. 172–3) notes, “Be mindful that the publication of incoherent and repetitive verbatim interview transcripts may involve an unethical stigmatization of specific persons or groups of people”. Oliver et al. ( 2005 ) similarly demonstrate how transcribers must make decisions about how to represent participants’ use of slang, colloquialisms and accents in ways that are accurate but also respectful of the respondent’s intended meaning. Some researchers decide to send finished transcriptions to interviewees for approval in order to honor commitments to fully informed consent, to ensure transcription accuracy or in some cases as a means to address the balance of power between the researcher and interviewee. As Mero-Jaffe ( 2011 ) describes, on the one hand, this may empower interviewees to control the way that they are portrayed in the research. On the other hand, Mero-Jaffe found that seeking transcript approval from interviewees sometimes increased their embarrassment at the way that their statements appear in text. This may be especially problematic with full verbatim transcriptions.

Technology and Transcription

As technology improves and AI becomes increasingly able to create written text from recorded audio, researchers might ask—is human transcription even necessary? New options in Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) such as NVivo, Atlas.ti and MAXQDA give qualitative researchers the option to forgo audio-to-text transcription altogether, and instead engage in live coding of audio or video files. Using this method, researchers first watch or listen to recordings to code for nonverbal cues, followed by a stage of note taking and coding based on pre-defined themes and matching these with time codes and nonverbal cues. Finally, researchers then transcribe specific quotes of interest from the recording (Parameswaran et al., 2020 ). This process may improve immersion in the data and allow researchers to account for dynamics that are often lost in complete audio-to-text transcription, such as group interactions and nonverbal communication.

There is a considerable need to develop the evidence base on the role of AI in transcription for qualitative research, with many important publications that consider the issue (e.g. Gibbs et al., 2002 ; Markle et al., 2011 ) out-of-date given the swift rate of change in AI technologies. Over the last few years, voice and speech recognition technologies have improved dramatically and may now be able to provide researchers with “good enough” first drafts of transcripts (Bokhove & Downey, 2018 ), providing certain conditions are in place (e.g. limited number of speakers and excellent audio quality). Using these technologies can save researchers time and money. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, many qualitative researchers are now undertaking interviews over Zoom or other video conferencing apps, which is a trend that may continue beyond the pandemic (Dodds & Hess, 2020 ). Zoom offers AI live transcription options, which benefits from the generally clear audio quality of a video conference, compared to in-person interviews where there is a greater chance of audio interference and background noise that may be undetected in the moment.

While AI may offer a cheaper and quicker alternative to human transcription, these transcripts will need to be meticulously checked by the researcher to ensure accuracy, fill in missing details or edit for context and readability. Using cloud-based AI transcription services also raises potential ethical concerns about data protection and confidentiality (Da Silva, 2021 ). There are numerous subjective decisions made in the course of creating a transcription that AI is unable to process, such as where to include punctuation, which words to include or exclude (such as filler words, hesitations, etc.) and how to denote things such as interruptions, hesitations and nonverbal cues. Voice-to-text software is also generally less accurate in discerning multiple voices or different accents (Bokhove & Downey, 2018 ). Several studies have considered how researchers/transcribers can use voice recognition software to listen and repeat the spoken text of an interview into software as a shortcut to traditional typing transcription (Matheson, 2007 ; Tilley, 2003 ), but the above shortcomings and cautions apply.

Transcription and Third Sector Research

Transcription matters for third sector research because qualitative research methodologies make up a large percentage of studies undertaken on nonprofits—as much as 40–80% of research published in this field (Igalla et al., 2019 ; Laurett & Ferreira, 2018 ; von Schnurbein et al., 2018 ). Audio transcription is particularly important for third sector research for several reasons. In conducting qualitative research (which aims to produce rich, rigorous description) and as third sector researchers (who study organizations that seek to improve society and who may be working with traditionally disenfranchised or disadvantaged communities), we have a particular ethical obligation to ensure that our research provides an accurate depiction of our participants’ lives and the organizations with which they are involved.

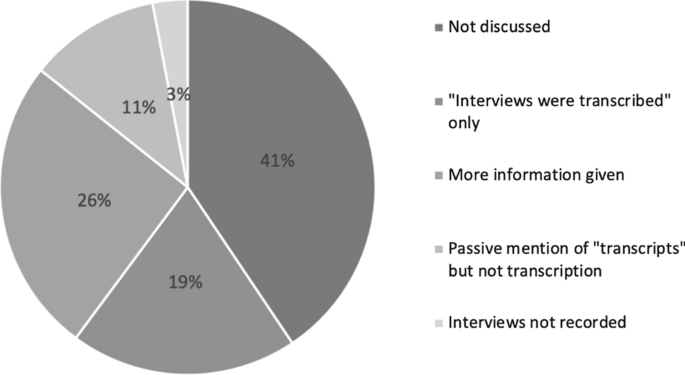

However, transcription is perhaps the most underacknowledged aspect of the qualitative research process, and this is also evident in the way that transcription is discussed in research articles. In order to survey the current depiction of the transcription process in third sector research, I undertook a review of the 212 most recent papers in Voluntas that include the word ‘interview’ to explore how qualitative research articles discuss transcription as part of their methodology. Footnote 1 Of these papers, 79 were deemed not applicable (because they were quantitative research papers that mentioned interviews in another context, or used the word interview to denote the administering of a structured questionnaire, or systematic review papers reporting on other research). This left 133 articles which were analyzed to explore the extent to which transcription was described—if at all—as part of the research methodology. Footnote 2

The analysis (illustrated in Fig. 1 ) found that 41% of papers employing interviews as a research method did not mention transcription at all, while 11% mentioned transcripts but not the process of transcription. It was not clear from these whether or not interviews were recorded or if researchers relied upon written notes taken during interviews, or how information from the oral interview was converted into analyzable text. The most common discussion of transcription (19%) was a simple sentence along the lines of “interviews were recorded and transcribed”, while 26% gave some further information including who undertook the transcription (the researcher(s), a research assistant or a commercial company) or that the interviews were transcribed ‘verbatim’ (with none explaining what they mean by this term). These findings are not dissimilar to a study of qualitative research in nursing, where it was found that 66% of articles reporting solely that interviews were transcribed, and the remaining articles indicated only “full” or “verbatim” to clarify the process (Wellard & McKenna, 2001 ). I also surveyed the first authors’ departmental affiliations/field of study to gauge any differences between academic fields (Table 1 ) although there were not considerable differences.

Transcription in Voluntas qualitative articles

The fact that over half of the Voluntas articles using interviews as a research method make no mention of the transcription process is a problem for transparency in qualitative research. This tendency may be a symptom of the fact that qualitative researchers face greater challenges in academic publishing that disadvantage longer from, in-depth qualitative research to fit within prescribed word limits (Moravcsik, 2014 ). In researchers’ efforts to ensure that qualitative research meets requirements for transparency, rigor and reliability, efforts are concentrated on descriptions of case and participant selection and data analysis while transcription as the conduit between data collection and analysis remains unproblematized. This emphasis reflects the growing influence of positivist views of validity. Ignoring the subjective decisions and theoretical perspectives that determine the creation of a transcript therefore inadvertently presupposes a positivist stance on the objective nature of data which is inconsistent with qualitative methodologies.

A Framework for Undertaking and Reporting on Transcription

As shown in the previous section, there is currently widespread neglect of transcription as part of interpretive qualitative research on the third sector. In this section, I present key elements for third sector researchers to consider in regard to transcription, both to ensure rigor as part of the qualitative research process and in writing up qualitative research, drawing upon examples of good practice from previous research in Voluntas. These recommendations are based on a review of the literature as well as my personal experience as a qualitative researcher, qualitative methods teacher, and professional transcriber.

Before Transcribing: Ethics and Data Management

All decisions regarding research design, data collection and data management should be made at the beginning of a qualitative research project when applying for ethical/IRB approval from one’s university, and this includes transcription. At this stage, the researcher should confirm with their university whether they have a budget for transcription. Undertaking ethical qualitative research means ensuring standards of transparency, informed consent, confidentiality and protection of the data obtained from the research (Blaxter et al., 2001 ). Increasing concerns about data protection and legislation such as GDPR in the European Union have prompted many universities to institute strict rules about where research data can be stored. Some universities do not allow the use of certain cloud servers, such as Dropbox. These considerations should be taken into account when deciding how to undertake and record interviews (Da Silva, 2021 )—for instance, if you are recording using your mobile phone, it is important to be sure you know whether recordings automatically upload to the cloud. For this reason, it may be preferable to use a traditional digital recorder so you can manually download the files to your computer and know exactly where everything is saved.

Before Transcribing: The Interview