An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Sage Choice

Continuing to enhance the quality of case study methodology in health services research

Shannon l. sibbald.

1 Faculty of Health Sciences, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada.

2 Department of Family Medicine, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada.

3 The Schulich Interfaculty Program in Public Health, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada.

Stefan Paciocco

Meghan fournie, rachelle van asseldonk, tiffany scurr.

Case study methodology has grown in popularity within Health Services Research (HSR). However, its use and merit as a methodology are frequently criticized due to its flexible approach and inconsistent application. Nevertheless, case study methodology is well suited to HSR because it can track and examine complex relationships, contexts, and systems as they evolve. Applied appropriately, it can help generate information on how multiple forms of knowledge come together to inform decision-making within healthcare contexts. In this article, we aim to demystify case study methodology by outlining its philosophical underpinnings and three foundational approaches. We provide literature-based guidance to decision-makers, policy-makers, and health leaders on how to engage in and critically appraise case study design. We advocate that researchers work in collaboration with health leaders to detail their research process with an aim of strengthening the validity and integrity of case study for its continued and advanced use in HSR.

Introduction

The popularity of case study research methodology in Health Services Research (HSR) has grown over the past 40 years. 1 This may be attributed to a shift towards the use of implementation research and a newfound appreciation of contextual factors affecting the uptake of evidence-based interventions within diverse settings. 2 Incorporating context-specific information on the delivery and implementation of programs can increase the likelihood of success. 3 , 4 Case study methodology is particularly well suited for implementation research in health services because it can provide insight into the nuances of diverse contexts. 5 , 6 In 1999, Yin 7 published a paper on how to enhance the quality of case study in HSR, which was foundational for the emergence of case study in this field. Yin 7 maintains case study is an appropriate methodology in HSR because health systems are constantly evolving, and the multiple affiliations and diverse motivations are difficult to track and understand with traditional linear methodologies.

Despite its increased popularity, there is debate whether a case study is a methodology (ie, a principle or process that guides research) or a method (ie, a tool to answer research questions). Some criticize case study for its high level of flexibility, perceiving it as less rigorous, and maintain that it generates inadequate results. 8 Others have noted issues with quality and consistency in how case studies are conducted and reported. 9 Reporting is often varied and inconsistent, using a mix of approaches such as case reports, case findings, and/or case study. Authors sometimes use incongruent methods of data collection and analysis or use the case study as a default when other methodologies do not fit. 9 , 10 Despite these criticisms, case study methodology is becoming more common as a viable approach for HSR. 11 An abundance of articles and textbooks are available to guide researchers through case study research, including field-specific resources for business, 12 , 13 nursing, 14 and family medicine. 15 However, there remains confusion and a lack of clarity on the key tenets of case study methodology.

Several common philosophical underpinnings have contributed to the development of case study research 1 which has led to different approaches to planning, data collection, and analysis. This presents challenges in assessing quality and rigour for researchers conducting case studies and stakeholders reading results.

This article discusses the various approaches and philosophical underpinnings to case study methodology. Our goal is to explain it in a way that provides guidance for decision-makers, policy-makers, and health leaders on how to understand, critically appraise, and engage in case study research and design, as such guidance is largely absent in the literature. This article is by no means exhaustive or authoritative. Instead, we aim to provide guidance and encourage dialogue around case study methodology, facilitating critical thinking around the variety of approaches and ways quality and rigour can be bolstered for its use within HSR.

Purpose of case study methodology

Case study methodology is often used to develop an in-depth, holistic understanding of a specific phenomenon within a specified context. 11 It focuses on studying one or multiple cases over time and uses an in-depth analysis of multiple information sources. 16 , 17 It is ideal for situations including, but not limited to, exploring under-researched and real-life phenomena, 18 especially when the contexts are complex and the researcher has little control over the phenomena. 19 , 20 Case studies can be useful when researchers want to understand how interventions are implemented in different contexts, and how context shapes the phenomenon of interest.

In addition to demonstrating coherency with the type of questions case study is suited to answer, there are four key tenets to case study methodologies: (1) be transparent in the paradigmatic and theoretical perspectives influencing study design; (2) clearly define the case and phenomenon of interest; (3) clearly define and justify the type of case study design; and (4) use multiple data collection sources and analysis methods to present the findings in ways that are consistent with the methodology and the study’s paradigmatic base. 9 , 16 The goal is to appropriately match the methods to empirical questions and issues and not to universally advocate any single approach for all problems. 21

Approaches to case study methodology

Three authors propose distinct foundational approaches to case study methodology positioned within different paradigms: Yin, 19 , 22 Stake, 5 , 23 and Merriam 24 , 25 ( Table 1 ). Yin is strongly post-positivist whereas Stake and Merriam are grounded in a constructivist paradigm. Researchers should locate their research within a paradigm that explains the philosophies guiding their research 26 and adhere to the underlying paradigmatic assumptions and key tenets of the appropriate author’s methodology. This will enhance the consistency and coherency of the methods and findings. However, researchers often do not report their paradigmatic position, nor do they adhere to one approach. 9 Although deliberately blending methodologies may be defensible and methodologically appropriate, more often it is done in an ad hoc and haphazard way, without consideration for limitations.

Cross-analysis of three case study approaches, adapted from Yazan 2015

| Dimension of interest | Yin | Stake | Merriam |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case study design | Logical sequence = connecting empirical data to initial research question Four types: single holistic, single embedded, multiple holistic, multiple embedded | Flexible design = allow major changes to take place while the study is proceeding | Theoretical framework = literature review to mold research question and emphasis points |

| Case study paradigm | Positivism | Constructivism and existentialism | Constructivism |

| Components of study | “Progressive focusing” = “the course of the study cannot be charted in advance” (1998, p 22) Must have 2-3 research questions to structure the study | ||

| Collecting data | Quantitative and qualitative evidentiary influenced by: | Qualitative data influenced by: | Qualitative data research must have necessary skills and follow certain procedures to: |

| Data collection techniques | |||

| Data analysis | Use both quantitative and qualitative techniques to answer research question | Use researcher’s intuition and impression as a guiding factor for analysis | “it is the process of making meaning” (1998, p 178) |

| Validating data | Use triangulation | Increase internal validity Ensure reliability and increase external validity |

The post-positive paradigm postulates there is one reality that can be objectively described and understood by “bracketing” oneself from the research to remove prejudice or bias. 27 Yin focuses on general explanation and prediction, emphasizing the formulation of propositions, akin to hypothesis testing. This approach is best suited for structured and objective data collection 9 , 11 and is often used for mixed-method studies.

Constructivism assumes that the phenomenon of interest is constructed and influenced by local contexts, including the interaction between researchers, individuals, and their environment. 27 It acknowledges multiple interpretations of reality 24 constructed within the context by the researcher and participants which are unlikely to be replicated, should either change. 5 , 20 Stake and Merriam’s constructivist approaches emphasize a story-like rendering of a problem and an iterative process of constructing the case study. 7 This stance values researcher reflexivity and transparency, 28 acknowledging how researchers’ experiences and disciplinary lenses influence their assumptions and beliefs about the nature of the phenomenon and development of the findings.

Defining a case

A key tenet of case study methodology often underemphasized in literature is the importance of defining the case and phenomenon. Researches should clearly describe the case with sufficient detail to allow readers to fully understand the setting and context and determine applicability. Trying to answer a question that is too broad often leads to an unclear definition of the case and phenomenon. 20 Cases should therefore be bound by time and place to ensure rigor and feasibility. 6

Yin 22 defines a case as “a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context,” (p13) which may contain a single unit of analysis, including individuals, programs, corporations, or clinics 29 (holistic), or be broken into sub-units of analysis, such as projects, meetings, roles, or locations within the case (embedded). 30 Merriam 24 and Stake 5 similarly define a case as a single unit studied within a bounded system. Stake 5 , 23 suggests bounding cases by contexts and experiences where the phenomenon of interest can be a program, process, or experience. However, the line between the case and phenomenon can become muddy. For guidance, Stake 5 , 23 describes the case as the noun or entity and the phenomenon of interest as the verb, functioning, or activity of the case.

Designing the case study approach

Yin’s approach to a case study is rooted in a formal proposition or theory which guides the case and is used to test the outcome. 1 Stake 5 advocates for a flexible design and explicitly states that data collection and analysis may commence at any point. Merriam’s 24 approach blends both Yin and Stake’s, allowing the necessary flexibility in data collection and analysis to meet the needs.

Yin 30 proposed three types of case study approaches—descriptive, explanatory, and exploratory. Each can be designed around single or multiple cases, creating six basic case study methodologies. Descriptive studies provide a rich description of the phenomenon within its context, which can be helpful in developing theories. To test a theory or determine cause and effect relationships, researchers can use an explanatory design. An exploratory model is typically used in the pilot-test phase to develop propositions (eg, Sibbald et al. 31 used this approach to explore interprofessional network complexity). Despite having distinct characteristics, the boundaries between case study types are flexible with significant overlap. 30 Each has five key components: (1) research question; (2) proposition; (3) unit of analysis; (4) logical linking that connects the theory with proposition; and (5) criteria for analyzing findings.

Contrary to Yin, Stake 5 believes the research process cannot be planned in its entirety because research evolves as it is performed. Consequently, researchers can adjust the design of their methods even after data collection has begun. Stake 5 classifies case studies into three categories: intrinsic, instrumental, and collective/multiple. Intrinsic case studies focus on gaining a better understanding of the case. These are often undertaken when the researcher has an interest in a specific case. Instrumental case study is used when the case itself is not of the utmost importance, and the issue or phenomenon (ie, the research question) being explored becomes the focus instead (eg, Paciocco 32 used an instrumental case study to evaluate the implementation of a chronic disease management program). 5 Collective designs are rooted in an instrumental case study and include multiple cases to gain an in-depth understanding of the complexity and particularity of a phenomenon across diverse contexts. 5 , 23 In collective designs, studying similarities and differences between the cases allows the phenomenon to be understood more intimately (for examples of this in the field, see van Zelm et al. 33 and Burrows et al. 34 In addition, Sibbald et al. 35 present an example where a cross-case analysis method is used to compare instrumental cases).

Merriam’s approach is flexible (similar to Stake) as well as stepwise and linear (similar to Yin). She advocates for conducting a literature review before designing the study to better understand the theoretical underpinnings. 24 , 25 Unlike Stake or Yin, Merriam proposes a step-by-step guide for researchers to design a case study. These steps include performing a literature review, creating a theoretical framework, identifying the problem, creating and refining the research question(s), and selecting a study sample that fits the question(s). 24 , 25 , 36

Data collection and analysis

Using multiple data collection methods is a key characteristic of all case study methodology; it enhances the credibility of the findings by allowing different facets and views of the phenomenon to be explored. 23 Common methods include interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. 5 , 37 By seeking patterns within and across data sources, a thick description of the case can be generated to support a greater understanding and interpretation of the whole phenomenon. 5 , 17 , 20 , 23 This technique is called triangulation and is used to explore cases with greater accuracy. 5 Although Stake 5 maintains case study is most often used in qualitative research, Yin 17 supports a mix of both quantitative and qualitative methods to triangulate data. This deliberate convergence of data sources (or mixed methods) allows researchers to find greater depth in their analysis and develop converging lines of inquiry. For example, case studies evaluating interventions commonly use qualitative interviews to describe the implementation process, barriers, and facilitators paired with a quantitative survey of comparative outcomes and effectiveness. 33 , 38 , 39

Yin 30 describes analysis as dependent on the chosen approach, whether it be (1) deductive and rely on theoretical propositions; (2) inductive and analyze data from the “ground up”; (3) organized to create a case description; or (4) used to examine plausible rival explanations. According to Yin’s 40 approach to descriptive case studies, carefully considering theory development is an important part of study design. “Theory” refers to field-relevant propositions, commonly agreed upon assumptions, or fully developed theories. 40 Stake 5 advocates for using the researcher’s intuition and impression to guide analysis through a categorical aggregation and direct interpretation. Merriam 24 uses six different methods to guide the “process of making meaning” (p178) : (1) ethnographic analysis; (2) narrative analysis; (3) phenomenological analysis; (4) constant comparative method; (5) content analysis; and (6) analytic induction.

Drawing upon a theoretical or conceptual framework to inform analysis improves the quality of case study and avoids the risk of description without meaning. 18 Using Stake’s 5 approach, researchers rely on protocols and previous knowledge to help make sense of new ideas; theory can guide the research and assist researchers in understanding how new information fits into existing knowledge.

Practical applications of case study research

Columbia University has recently demonstrated how case studies can help train future health leaders. 41 Case studies encompass components of systems thinking—considering connections and interactions between components of a system, alongside the implications and consequences of those relationships—to equip health leaders with tools to tackle global health issues. 41 Greenwood 42 evaluated Indigenous peoples’ relationship with the healthcare system in British Columbia and used a case study to challenge and educate health leaders across the country to enhance culturally sensitive health service environments.

An important but often omitted step in case study research is an assessment of quality and rigour. We recommend using a framework or set of criteria to assess the rigour of the qualitative research. Suitable resources include Caelli et al., 43 Houghten et al., 44 Ravenek and Rudman, 45 and Tracy. 46

New directions in case study

Although “pragmatic” case studies (ie, utilizing practical and applicable methods) have existed within psychotherapy for some time, 47 , 48 only recently has the applicability of pragmatism as an underlying paradigmatic perspective been considered in HSR. 49 This is marked by uptake of pragmatism in Randomized Control Trials, recognizing that “gold standard” testing conditions do not reflect the reality of clinical settings 50 , 51 nor do a handful of epistemologically guided methodologies suit every research inquiry.

Pragmatism positions the research question as the basis for methodological choices, rather than a theory or epistemology, allowing researchers to pursue the most practical approach to understanding a problem or discovering an actionable solution. 52 Mixed methods are commonly used to create a deeper understanding of the case through converging qualitative and quantitative data. 52 Pragmatic case study is suited to HSR because its flexibility throughout the research process accommodates complexity, ever-changing systems, and disruptions to research plans. 49 , 50 Much like case study, pragmatism has been criticized for its flexibility and use when other approaches are seemingly ill-fit. 53 , 54 Similarly, authors argue that this results from a lack of investigation and proper application rather than a reflection of validity, legitimizing the need for more exploration and conversation among researchers and practitioners. 55

Although occasionally misunderstood as a less rigourous research methodology, 8 case study research is highly flexible and allows for contextual nuances. 5 , 6 Its use is valuable when the researcher desires a thorough understanding of a phenomenon or case bound by context. 11 If needed, multiple similar cases can be studied simultaneously, or one case within another. 16 , 17 There are currently three main approaches to case study, 5 , 17 , 24 each with their own definitions of a case, ontological and epistemological paradigms, methodologies, and data collection and analysis procedures. 37

Individuals’ experiences within health systems are influenced heavily by contextual factors, participant experience, and intricate relationships between different organizations and actors. 55 Case study research is well suited for HSR because it can track and examine these complex relationships and systems as they evolve over time. 6 , 7 It is important that researchers and health leaders using this methodology understand its key tenets and how to conduct a proper case study. Although there are many examples of case study in action, they are often under-reported and, when reported, not rigorously conducted. 9 Thus, decision-makers and health leaders should use these examples with caution. The proper reporting of case studies is necessary to bolster their credibility in HSR literature and provide readers sufficient information to critically assess the methodology. We also call on health leaders who frequently use case studies 56 – 58 to report them in the primary research literature.

The purpose of this article is to advocate for the continued and advanced use of case study in HSR and to provide literature-based guidance for decision-makers, policy-makers, and health leaders on how to engage in, read, and interpret findings from case study research. As health systems progress and evolve, the application of case study research will continue to increase as researchers and health leaders aim to capture the inherent complexities, nuances, and contextual factors. 7

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved July 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Quasi-Experimental Research Design – Types...

Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Qualitative Research Methods

Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

- Corpus ID: 964694

Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for Novice Researchers

- Pamela Baxter , S. Jack

- Published 1 December 2008

- Education, Medicine

- The Qualitative Report

Tables from this paper

7,790 Citations

Case study as a method of qualitative research, case study as a qualitative research methodology, planning qualitative research: design and decision making for new researchers, qualitative case study research as empirical inquiry, case study observational research: a framework for conducting case study research where observation data are the focus, designing a case study template for theory building, case study method and research design, the qualitative report the, applying case study methodology to occupational science research, the case study as a type of qualitative research, 47 references, case study research: design and methods.

- Highly Influential

How to critique qualitative research articles.

Doing case study research: a practical guide for beginning researchers. third edition., the role of qualitative research in broadening the 'evidence base' for clinical practice., the problem of rigor in qualitative research, research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, qualitative evaluation and research methods, qualitative nursing research: a contemporary dialogue, reflecting on the strategic use of caqdas to manage and report on the qualitative research process, rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness., related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

- The Chicago School

- The Chicago School Library

- Research Guides

Research Methods: Qualitative

What is qualitative research, about this guide, introduction.

- Qualitative Research Approaches

- Key Resources

- Finding Qualitative Studies

The purpose of this guide is to provide a starting point for learning about qualitative research. In this guide, you'll find:

- Resources on diverse types of qualitative research.

- An overview of resources for data, methods, coding & analysis

- Popular qualitative software options

- Information on how to find qualitative studies

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a stand-alone study, purely relying on qualitative data or it could be part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data.

Qualitative researchers use multiple systems of inquiry for the study of human phenomena including biography, case study, historical analysis, discourse analysis, ethnography, grounded theory, and phenomenology.

Watch the following video to learn more about Qualitative Research:

(Video best viewed in Edge and Chrome browsers, or click here to view in the Sage Research Methods Database )

Qualitative Approaches

The case study approach is useful to employ when there is a need to obtain an in-depth appreciation of an issue, event or phenomenon of interest, in its natural real-life context.

Ethnography

Ethnographies are an in-depth, holistic type of research used to capture cultural practices, beliefs, traditions, and so on. Here, the researcher observes and interviews members of a culture an ethnic group, a clique, members of a religion, etc. and then analyzes their findings.

Grounded Theory

Researchers will create and test a hypothesis using qualitative data. Often, researchers use grounded theory to understand decision-making, problem-solving, and other types of behavior.

Narrative Research

Researchers use this type of framework to understand different aspects of the human experience and how their subjects assign meaning to their experiences. Researchers use interviews to collect data from a small group of subjects, then discuss those results in the form of a narrative or story.

Phenomenology

This type of research attempts to understand the lived experiences of a group and/or how members of that group find meaning in their experiences. Researchers use interviews, observation, and other qualitative methods to collect data.

Watch the video "Choosing among the Five Qualitative Approaches" from Sage Research Methods database for more on these qualitative approaches:

Note: Video is best viewed using Chrome, Edge, or Safari browsers.

Poth, C. (Academic). (2023). Choosing among five qualitative approaches [Video]. Sage Research Methods. doi.org/10.4135/9781529629866

- Next: Key Resources >>

- Last Updated: Jul 18, 2024 12:37 PM

- URL: https://library.thechicagoschool.edu/qualitative

Verify originality of an essay

Get ideas for your paper

Find top study documents

What is qualitative research? Approaches, methods, and examples

Published 19 Jul 2024

Students in social sciences frequently seek to understand how people feel, think, and behave in specific situations or relationships that evolve over time. To achieve this, they employ various techniques and data collection methods in qualitative research allowing for a deeper exploration of human experiences. Participant observation, in-depth interviews, and other qualitative methods are commonly used to gather rich, detailed data to uncover key aspects of social behavior and relationships. What is qualitative research? This article will answer this question and guide you through the essentials of this methodology, including data collection techniques and analytical approaches.

Qualitative research definition and significance

This inquiry method is helpful for learners interested in how to conduct research . It focuses on understanding human behavior, experiences, and social phenomena from the perspective of those involved. What does qualitative mean? It uses non-numerical data, such as interviews, observations, and textual analysis, to understand people’s feelings, thoughts, and actions.

Where and when is it used?

Qualitative analysis is crucial in education, healthcare, social sciences, marketing, and business. It helps gain detailed insights into behaviors, experiences, and cultural phenomena. This approach is fundamental during exploratory phases, for understanding complex issues, and when context-specific insights are required. By focusing on depth over breadth, this approach is often employed when researchers seek to explore complex issues, understand the context of a phenomenon, or investigate things that are not easily quantifiable. It uncovers rich, nuanced data essential for developing theories and evaluating programs.

Why is qualitative research important in academia?

- It sheds light on complex phenomena and human experiences that quantitative methods may overlook.

- This method offers contextual understanding by studying subjects in their natural environments, which is crucial for grasping real-world complexities.

- It adapts flexibly to evolving study findings and allows for adjusting approaches as new ideas emerge.

- It collects rich, detailed data through interviews, observations, and analysis, offering a comprehensive view of the exploration topic.

- Qualitative research studies focus on new or less explored areas, helping to identify key variables and generate hypotheses for further study.

- This approach focuses on understanding individuals' perspectives, motivations, and emotions, essential in fields like sociology, psychology, and education.

- It supports theory development by providing empirical data that can create new theories and frameworks (you may read about “ What is a conceptual framework ?” and learn about other frameworks on the EduBirdie website).

- It improves practices in fields such as education and healthcare by offering insights into practitioners' and clients' needs and experiences.

The difference between qualitative and quantitative studies

Now that you know the answer to “Why is qualitative data important?”, let’s consider how this method differs from quantitative. Both studies represent two main types of research methods. The qualitative approach focuses on understanding behaviors, experiences, and perspectives using interviews, observations, and analyzing texts. These studies are based on reflexivity and aim to explore complexities and contexts, often generating new ideas or theories. Researchers analyze data to find patterns and themes, clarifying the details. However, findings demonstrated in the results section of a research paper may not apply broadly because they often use small, specific groups rather than large, random samples.

Quantitative studies, on the other hand, emphasize numerical data and statistical analysis to measure variables and relationships. They use methods such as surveys, experiments, or analyzing existing data to collect structured information. The goal is quantifying phenomena, testing hypotheses, and determining correlations or causes. Statistical methods are used to analyze data, identifying patterns and significance. Quantitative studies produce results that can be applied to larger populations, providing generalizable findings. However, they may lack the detailed context that qualitative methods offer.

The approaches to qualitative research

To better understand the answer to “What is qualitative research?”, it’s necessary to consider various approaches within this methodology, each with its unique focus, implications, and functions.

1. Phenomenology.

This theory aims to understand and describe the lived experiences of individuals regarding a particular phenomenon.

Peculiarities:

- Focuses on personal experiences and perceptions.

- Seeks to uncover the essence of a phenomenon.

- Uses in-depth interviews and first-person accounts.

Example: Studying the experiences of people living with chronic illness to understand how it affects their daily lives.

2. Ethnography.

The approach involves immersive, long-term observation and participation in particular cultural or social contexts.

- Provides a deep understanding of cultural practices and social interactions.

- Involves participant observation and fieldwork.

- Researchers often live within the community they are studying.

Example: Observing and participating in the daily life of a rural village to understand its social structure and cultural practices.

3. Grounded theory.

This approach seeks to develop a research paper problem statement and theories based on participant data.

- Focuses on creating new theories rather than analyzing existing ones.

- Uses a systematic process of data collection and analysis.

- Involves constant comparison and coding of data.

Example: Developing a theory on how people cope with job loss by interviewing and analyzing the experiences of unemployed individuals.

4. Case study.

Case studies involve an in-depth examination of a single case or a small number of cases.

- Provides detailed, holistic insights.

- Can involve individuals, groups, organizations, or events.

- Uses multiple data sources such as interviews, observations, and documents.

Example: One of the qualitative research examples is analyzing a specific company’s approach to innovation to understand its success factors.

5. Narrative research.

This methodology focuses on the stories and personal interpretations of individuals.

- Emphasizes the chronological sequence and context of events.

- Seeks to understand how people make sense of their experiences.

- Uses interviews, diaries, and autobiographies.

Example: Collecting and analyzing the life stories of veterans to understand their experiences during and after military service.

6. Action research.

This theoretical model involves a collaborative approach in which researchers and participants work together to solve a problem or improve a situation.

- Aims for practical outcomes and improvements.

- Involves cycles of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting.

- Often used in educational, organizational, and community settings.

Example: Teachers collaborating with researchers to develop and test new teaching approaches to improve student engagement.

7. Discourse analysis.

It examines language use in texts, conversations, and other forms of communication.

- Focuses on how language shapes social reality and power dynamics.

- Analyzes speech, written texts, and media content.

- Explores the underlying meanings and implications of language.

Example: Analyzing political speeches to understand how leaders construct and convey their messages to the public.

Each of these examples of qualitative research offers unique tools and perspectives, enabling researchers to delve deeply into complex issues and gain a rich understanding of the issue they study.

Qualitative research methods

Various techniques exist to explore phenomena in depth and understand the complexities of human behavior, experiences, and social interactions. Some key methodologies that are commonly used in different sciences include several approaches.

Unstructured interviews;

These are informal and open-ended, designed to capture detailed narratives without imposing preconceived notions. Researchers typically start with a broad question and encourage interviewees to share their stories freely.

Semi-structured interviews;

They involve a core set of questions that allow researchers to explore topics deeply, adapting their inquiries based on responses received. This method of qualitative research design aims to gather rich, descriptive information, such as understanding what qualities make a good teacher.

Open questionnaire surveys;

They differ from closed-ended surveys in that they seek opinions and descriptions through open-ended questions. They allow for gathering diverse viewpoints from a larger group than one-on-one interviews would permit.

Observation;

It relies on researchers' skills to observe and interpret unbiased behaviors or activities. For instance, in education research, observation might track how students stay focused and manage distractions, recorded through field notes taken during or shortly after the observation.

Keeping logs and diaries;

This involves participants or researchers documenting daily activities or study contexts. Participants might record their social interactions or exercise routines, giving detailed data for later analysis. Researchers may also maintain diaries to document study contexts, helping to explain findings and other information sources.

All types of qualitative research have their strengths for gathering detailed information and exploring the social, cultural, and psychological aspects of exploration topics. Learners often use several methods (triangulation) to confirm their findings and deepen their understanding of complex subjects. If you need assistance choosing the most appropriate method to explore, feel free to contact our website, as we offer essays for sale and support with academic papers.

Advantages and disadvantages of the qualitative research methodology

This approach has unique strengths, making it valuable in many sciences. One of the primary advantages of qualitative research is its ability to capture participants' voices and perspectives accurately. It is highly adaptable, allowing researchers to modify the technique as new questions and ideas arise. This flexibility allows researchers to investigate new ideas and trends without being limited to set methods from the start. While this approach has many strengths, it also has significant drawbacks. A research paper writer faces practical and theoretical limitations when analyzing and interpreting data. Let’s consider all the pros and cons of this methodology in detail.

Strengths of qualitative research:

- Adaptability: Data gathering and analysis can be adjusted as new patterns or ideas develop, ensuring the study remains relevant and responsive.

- Real-world contexts: Research often occurs in natural conditions, providing a more authentic understanding of phenomena and describing the particularities of human behavior and interactions.

- Rich insights: Detailed analysis of people’s feelings, perceptions, and experiences can be useful for designing, testing, or developing systems, products, and services.

- Innovation: Open-ended responses allow experts to discover new problems or opportunities, leading to innovative ideas and approaches.

Limitations of qualitative research:

- Unpredictability: Real-world conditions often introduce uncontrolled factors, making this approach less reliable and difficult to replicate.

- Bias: The qualitative method relies heavily on the researcher’s viewpoint, leading to subjective interpretations. This makes it challenging to replicate studies and achieve consistent results.

- Limited applicability: Small, specific samples give detailed information but limit the ability to generalize findings to a broader population. Conclusions about the qualitative research topics may be biased and not representative of the wider population.

- Time and effort: Analyzing qualitative data is time-consuming and labor-intensive. While software can help, much of the analysis must be done manually, requiring significant effort and expertise.

So, qualitative methodology offers significant benefits, such as adaptability, real-world context, rich insights, and fostering innovation. However, it also presents challenges like unpredictability, bias, limited applicability, or time- and labor-intensive. Understanding these pros and cons helps researchers make informed decisions about when and how to effectively utilize various types of qualitative research designs in their studies.

Final thoughts

Qualitative research provides a valuable understanding of complicated human experiences and social situations, making it a strong tool in various areas of study. Despite its challenges, such as unreliability, subjectivity, and limited generalizability, its strengths in flexibility, natural settings, and generating meaningful insights make it an essential approach. If you are one of the students looking to incorporate qualitative methodology into their academic papers, EduBirdie is here to help. Our experts can guide you through the process, ensuring your work is thorough, credible, and impactful.

Was this helpful?

Thanks for your feedback.

Written by Elizabeth Miller

Seasoned academic writer, nurturing students' writing skills. Expert in citation and plagiarism. Contributing to EduBirdie since 2019. Aspiring author and dedicated volunteer. You will never have to worry about plagiarism as I write essays 100% from scratch. Vast experience in English, History, Ethics, and more.

Related Blog Posts

Discover how to compose acknowledgements in research paper.

This post will help you learn about the use of acknowledgements in research paper and determine how they are composed and why they must be present ...

How to conduct research: best tips from experienced EduBirdie writers

Have you ever got your scholarly task and been unsure how to start research? Are you a first-year student beginning your project? Whatever the case...

Research Papers on Economics: Writing Tips

More and more students nowadays are faced with the problem: How to write an economics paper. Research papers are one of the main results of researc...

Join our 150K of happy users

- Get original papers written according to your instructions

- Save time for what matters most

- Systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 15 July 2024

Teamwork and implementation of innovations in healthcare and human service settings: a systematic review

- Elizabeth A. McGuier ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6219-6358 1 ,

- David J. Kolko 1 ,

- Gregory A. Aarons 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Allison Schachter 5 , 6 ,

- Mary Lou Klem 7 ,

- Matthew A. Diabes 8 ,

- Laurie R. Weingart 8 ,

- Eduardo Salas 9 &

- Courtney Benjamin Wolk 5 , 6

Implementation Science volume 19 , Article number: 49 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

610 Accesses

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

Implementation of new practices in team-based settings requires teams to work together to respond to new demands and changing expectations. However, team constructs and team-based implementation approaches have received little attention in the implementation science literature. This systematic review summarizes empirical research examining associations between teamwork and implementation outcomes when evidence-based practices and other innovations are implemented in healthcare and human service settings.

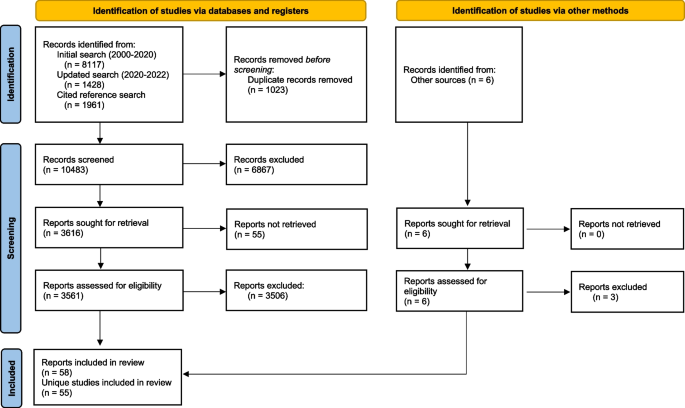

We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, APA PsycINFO and ERIC for peer-reviewed empirical articles published from January 2000 to March 2022. Additional articles were identified by searches of reference lists and a cited reference search for included articles (completed in February 2023). We selected studies using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods to examine associations between team constructs and implementation outcomes in healthcare and human service settings. We used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool to assess methodological quality/risk of bias and conducted a narrative synthesis of included studies. GRADE and GRADE-CERQual were used to assess the strength of the body of evidence.

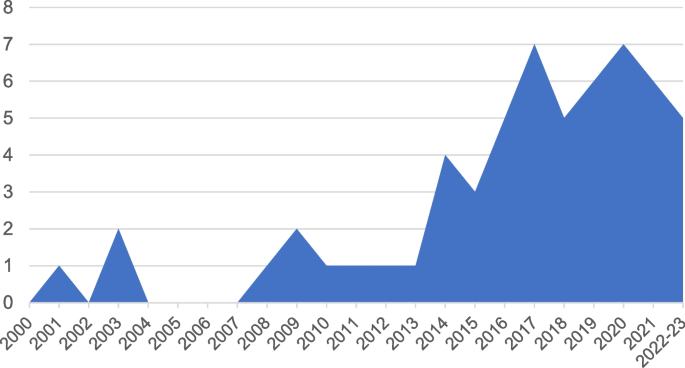

Searches identified 10,489 results. After review, 58 articles representing 55 studies were included. Relevant studies increased over time; 71% of articles were published after 2016. We were unable to generate estimates of effects for any quantitative associations because of very limited overlap in the reported associations between team variables and implementation outcomes. Qualitative findings with high confidence were: 1) Staffing shortages and turnover hinder implementation; 2) Adaptive team functioning (i.e., positive affective states, effective behavior processes, shared cognitive states) facilitates implementation and is associated with better implementation outcomes; Problems in team functioning (i.e., negative affective states, problematic behavioral processes, lack of shared cognitive states) act as barriers to implementation and are associated with poor implementation outcomes; and 3) Open, ongoing, and effective communication within teams facilitates implementation of new practices; poor communication is a barrier.

Conclusions

Teamwork matters for implementation. However, both team constructs and implementation outcomes were often poorly specified, and there was little overlap of team constructs and implementation outcomes studied in quantitative studies. Greater specificity and rigor are needed to understand how teamwork influences implementation processes and outcomes. We provide recommendations for improving the conceptualization, description, assessment, analysis, and interpretation of research on teams implementing innovations.

Trial registration

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews. Registration number: CRD42020220168.

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the Literature:

This paper reviews more than 20 years of research on teams and implementation of new practices in healthcare and human service settings.

We concluded with high confidence that adaptive team functioning is associated with better implementation outcomes and problems in team functioning are associated with poorer implementation outcomes. While not surprising, the implementation science literature has lacked clear empirical evidence for this finding.

Use of the provided recommendations will improve the quality of future research on teams and implementation of evidence-based practices.

Healthcare and human service providers (e.g., clinicians, case managers) often work in team-based settings where professionals work collaboratively with one another and service recipients toward shared goals [ 1 , 2 ]. Team-based care is intended to include multiple professionals with varying skills and expertise [ 1 , 3 ]. It requires shared responsibility for outcomes and increases team members’ dependence on one another to complete work [ 1 , 3 , 4 ]. Effective team-based care and higher quality teamwork are associated with improvements in care access and quality, patient safety, patient satisfaction, clinical outcomes, and costs [ 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ].

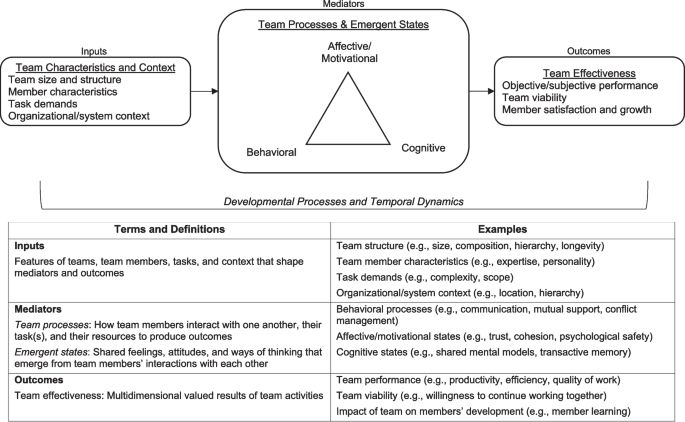

We use the term ‘teamwork’ to refer to an array of team constructs using the input-mediator-outcome-input (IMOI) framework (Fig. 1 ) [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. The IMOI framework recognizes that team interactions are dynamic and complex, with processes unfolding over time and feedback loops between processes, outcomes, and inputs [ 10 ]. Team inputs include team structure and composition, task demands, and contextual features [ 13 ]. Mediators are aspects of team functioning (i.e., what team members think, feel, and do [ 12 ]) through which inputs influence outcomes. These processes and emergent states may be cognitive, affective, or behavioral [ 5 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Team effectiveness outcomes are multidimensional and include team performance as well as team viability and the impact of the team on members’ development [ 12 , 17 , 18 , 19 ].

Conceptual model of team effectiveness and key terminology. Figure adapted from “Advancing research on teams and team effectiveness in implementation science: An application of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework” by E.A. McGuier, D.J. Kolko, N.A. Stadnick, L. Brookman-Frazee, C.B. Wolk, C.T. Yuan, C.S. Burke, & G.A. Aarons, 2023, Implementation Research and Practice , 4 , 26334895231190855. [CC BY-NC]

Implementation of new practices in team-based service settings requires team members to work together to respond to changing demands and expectations. Extensive research has identified barriers and facilitators to implementation of new practices at the individual provider, organization, and system levels; however, the team level has received little empirical attention [ 20 , 21 ]. This is a problem because implementation efforts increasingly rely on teams, and responses to a new practice are likely to be influenced by team characteristics and processes. See McGuier and colleagues [ 20 ] for an overview of team constructs in the context of implementation science and the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework [ 22 , 23 ]. Given increasing use of team-based care and interest in implementation strategies targeting teams, examining how teamwork is associated with implementation processes and outcomes is critical. This systematic review identified and summarized empirical research examining associations between teamwork and implementation outcomes when evidence-based practices (EBPs) and other innovations were implemented in healthcare and human service settings.

This systematic review was registered (PROSPERO; registration number: CRD42020220168) and conducted following the published protocol [ 24 ]. The review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA and SWiM guidance [ 25 , 26 ]; relevant checklists are in Additional File 1.

Information sources and search strategy

We searched the following databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL (Ebsco), APA PsycINFO (Ovid), and ERIC (Ebsco). Database searches were run on August 7, 2020, and again on March 8, 2022. For all searches, a publication date from 2000 to current was applied; there were no language restrictions (see [ 24 ]). An experienced health sciences librarian (MLK) designed the Ovid MEDLINE search and translated that search for use in the other databases (see additional file in [ 24 ]). The search strings consisted of controlled vocabulary (when available) and natural language terms representing concepts of teamwork and implementation science or innovation or evidence-based practice. Results were downloaded to an EndNote (version X9.3.3) library and duplicate records removed [ 27 ]. Additional relevant articles were identified by hand searches of reference lists of included articles, a cited reference search for included articles in the Web of Science (Clarivate) bibliographic database (completed in February 2023), and requests sent to implementation science listservs and centers for suggestions of relevant articles.

Eligibility criteria

We included empirical journal articles describing studies using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. Study protocols, reviews, and commentaries were excluded. All studies were conducted in healthcare or human service settings (e.g., hospitals, clinics, child welfare) and described the implementation of a practice to improve patient care. Studies of interventions to improve teamwork (e.g., team building interventions) and studies of teams created to implement the innovation (e.g., quality improvement teams, implementation support teams) were excluded. Eligible studies assessed at least one team construct and described its influence on implementation processes and outcomes.

Changes from protocol

Several changes were made from our systematic review protocol (PROSPERO CRD42020220168; [ 24 ]). Specifically, during the full-text review stage, we broadened the scope from team functioning (i.e., processes and states) to include team structure and performance because of the small number of studies that assessed and reported specific processes or states. This change increased the number of included studies. Similarly, because implementation outcomes were often inconsistently defined and poorly reported [ 28 , 29 , 30 ], we broadened our scope to include studies that identified team constructs as implementation determinants (i.e., barriers/facilitators) without explicitly defining and measuring an implementation outcome. Because of changes in university access to bibliographic databases, the cited reference search was performed in the Web of Science only instead of the Web of Science and Scopus. This bibliographic database indexes more than 21,000 scientific journals [ 31 ]. Lastly, because of time and resource constraints, we did not search conference abstracts or contact authors for unreported data.

Selection process and data extraction

Title/abstract screening and review of full-text articles were conducted by pairs of trained independent reviewers in DistillerSR. Conflicts were resolved through re-review, discussion between reviewers, and when needed, discussion with a senior team member (EAM). A final review of all included articles was conducted by EAM. Relevant data from each article was extracted into an Excel spreadsheet by one reviewer (AS). A second reviewer (EAM) conducted a line-by-line review and verification. Our data extraction form was informed by existing forms and guides (e.g., [ 32 , 33 ]). For each included study, we extracted information on measures of teamwork and implementation-relevant outcomes, characteristics of the setting, teams, and participants, analysis methods, and results. For quantitative studies, we recorded correlation coefficients and/or regression coefficients as standardized metrics of association. For qualitative studies, we recorded themes [ 33 ].

Quality and risk of bias assessment