- Inside SC Johnson

COVID-19’s impact on work, workers, and the workplace of the future

What will the world of work look like, post COVID-19? A paper co-authored by Dyson School faculty member Kevin Kniffin along with 28 other researchers and scholars from around the world — “ COVID-19 and the Workplace: Implications, Issues, and Insights for Future Research and Action ” ( American Psychologist ) — includes a preview of how COVID-19 may change work practices in the long term and offers projections about the workplace of the future.

Kniffin and his co-authors took a broad view of the pandemic’s many impacts on the workplace, encapsulating existing research, predicting a few likely outcomes, and pointing to new questions worthy of study. “By organizing our experiences as researchers in a wide array of topical areas,” they wrote, “we present a review of relevant literatures along with an evidence-based preview of changes that we expect in the wake of COVID-19 for both research and practice.”

“‘Sensemaking’ was the first value generated by this extraordinary collaboration, which we undertook because of the extraordinary impacts associated with the emergence of COVID-19,” says Kniffin. “With so many dimensions of work and life changing rapidly in relation to COVID-19, a clear and succinct assessment was our first task—and a foundation for charting roadmaps for future research and action.”

A new normal: Working from home

When the pandemic hit the U.S. hard in March, millions of workers began working from home – an unprecedented and ongoing phenomenon “facilitated by the rise of connectivity and communication technologies,” Kniffin and his co-authors note in the paper.

The authors project that working from home will not only continue for many workers, but that “COVID-19 will accelerate trends towards working from home past the immediate impacts of the pandemic.” This will be driven, in part, as organizations recognize the health risks of open-plan offices. “As we now live and work in globally interdependent communities, infectious disease threats such as COVID-19 need to be recognized as part of the workscape,” write Kniffin et al. “To continue to reap the benefits from global cooperation, we must find smarter and safer ways of working together.” Organizations will also appreciate the cost-savings of replacing full-time employees with contractors who can stay connected digitally, note the authors.

In light of this anticipated shift, one goal of the paper is to guide future research to “examine whether and how the COVID-19 quarantines that required millions to work from home affected work productivity, creativity, and innovation.”

Best practices for high-functioning virtual teams

Virtual teams were already growing in number and importance pre-COVID-19, as noted in the paper. Now, many workers participate in a variety of remote teams, via synchronous and asynchronous digital communication. Since virtual teams are here to stay for many workers even post-pandemic, it’s important to recognize the challenges and adopt best practices. For example, the authors point out that “traditional teamwork problems such as conflict and coordination can escalate quickly in virtual teams” and offer recommendations based on prior research, including:

- Build structural scaffolds to mitigate conflicts, align teams, and ensure safe and thorough information processing.

- Formalize team processes, clarify team goals, and build-in structural solutions to foster psychologically safe discussions.

- Provide opportunities for non-task interactions among employees to allow emotional connections and bonding to continue among team members.

Greater appreciation for woman leaders?

“A feminine style of leadership might become recognized as optimal for dealing with crises in the future,” write Kniffin et al. They point to high-profile woman leaders who have grappled with COVID-19 effectively, including Angela Merkel, chancellor of Germany, and Tsai Ing-wen, president of Taiwan. And they list several feminine values and traits that can be effective in crisis management (pointing to the relevant research regarding each trait), including:

- a communal orientation in moral decision-making,

- higher sensitivity to risk, particularly about health issues,

- higher conscientiousness, and

- more attentive communication styles.

Creating roadmaps for new patterns of work

In addition to the sudden shift in working from home, “COVID-19 and the Workplace” touches on many other aspects of the pandemic’s impact on workers and organizations. They point to the economic, social, and psychological challenges and risks for workers deemed “essential” as well as for furloughed and laid-off workers. They touch on fundamental changes brought about in some industries, and new opportunities in others. Regarding impacts on workers, they discuss increases in economic inequality, social distancing and loneliness, stress and burnout, and addiction. The authors also refer to factors that moderate the impacts of workplace changes brought about by the pandemic, including age, race and ethnicity, gender, family status, personality, and cultural differences.

By drawing on existing research to help make sense of the crisis and highlighting topics ripe for new research, the authors hope to clear a path to guide studies focused on building positive, productive interactions that will aid in the ongoing transition to new patterns of work. “We hope that our effort will help researchers and practitioners take steps to manage and mitigate the negative effects of COVID-19 and start designing evidence-based roadmaps for moving forward.”

“When we started this project,” Kniffin added, “it wasn’t clear how long COVID-19 would persist as a force of disruption and destruction. As the pandemic has persisted, though, it’s increasingly clear that COVID-19 should be considered for its impact in relation to almost any work-related practice. On top of that, the many ways in which COVID-19 has variably and disparately impacted people and work around the world warrants close attention, concern, and action.”

- Organizational Behavior

- Thought Leadership

Tim Iorio, Ph.D.

I am working on a book concerning survival in Corporate America: Lessons Learned (my memoirs), including chapters on how COVID-19 has changed the landscape. Your research is needed and invaluable, and I look forward to following it. I will more than likely do some Qualitative Research myself on the subject. Thank you.

Rachel Frampton

From my point of view, businesses must invest in workplace covid management software that will protect their employees. Well, I agree with you that they must provide smarter and safer ways of working together. We also share the same opinion about the importance of providing virtual consultations and meetings.

Comments are closed.

The future of work after COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted labor markets globally during 2020. The short-term consequences were sudden and often severe: Millions of people were furloughed or lost jobs, and others rapidly adjusted to working from home as offices closed. Many other workers were deemed essential and continued to work in hospitals and grocery stores, on garbage trucks and in warehouses, yet under new protocols to reduce the spread of the novel coronavirus.

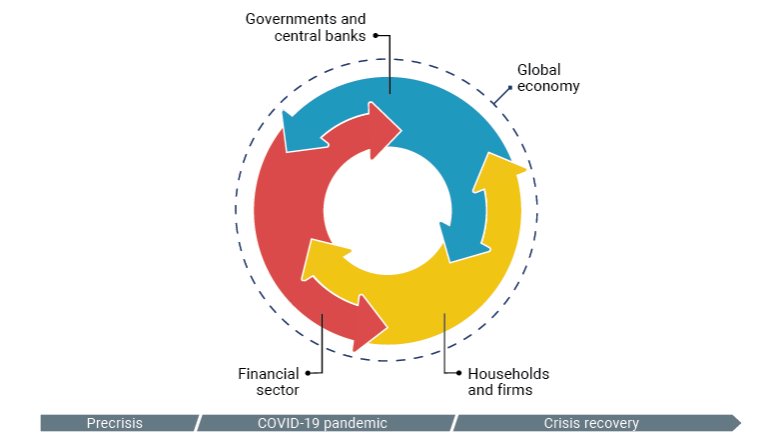

This report on the future of work after COVID-19 is the first of three MGI reports that examine aspects of the postpandemic economy. The others look at the pandemic’s long-term influence on consumption and the potential for a broad recovery led by enhanced productivity and innovation. Here, we assess the lasting impact of the pandemic on labor demand, the mix of occupations, and the workforce skills required in eight countries with diverse economic and labor market models: China, France, Germany, India, Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Together, these eight countries account for almost half the global population and 62 percent of GDP.

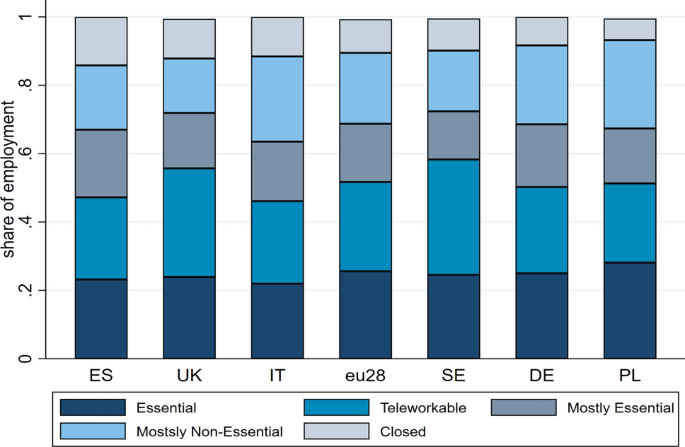

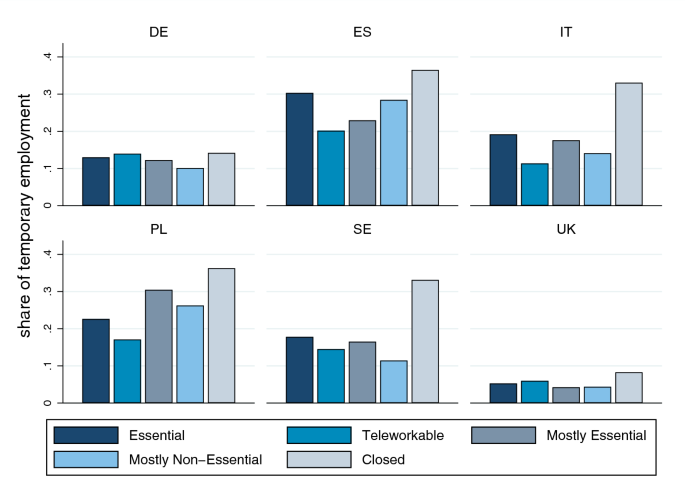

Jobs with the highest physical proximity are likely to be most disrupted

Before COVID-19, the largest disruptions to work involved new technologies and growing trade links. COVID-19 has, for the first time, elevated the importance of the physical dimension of work. In this research, we develop a novel way to quantify the proximity required in more than 800 occupations by grouping them into ten work arenas according to their proximity to coworkers and customers, the number of interpersonal interactions involved, and their on-site and indoor nature.

This offers a different view of work than traditional sector definitions. For instance, our medical care arena includes only caregiving roles requiring close interaction with patients, such as doctors and nurses. Hospital and medical office administrative staff fall into the computer-based office work arena, where more work can be done remotely. Lab technicians and pharmacists work in the indoor production work arena because those jobs require use of specialized equipment on-site but have little exposure to other people (Exhibit 1).

We find that jobs in work arenas with higher levels of physical proximity are likely to see greater transformation after the pandemic, triggering knock-on effects in other work arenas as business models shift in response.

The short- and potential long-term disruptions to these arenas from COVID-19 vary. During the pandemic, the virus most severely disturbed arenas with the highest overall physical proximity scores: medical care, personal care, on-site customer service, and leisure and travel. In the longer term, work arenas with higher physical proximity scores are also likely to be more unsettled, although proximity is not the only explanation. For example:

- The on-site customer interaction arena includes frontline workers who interact with customers in retail stores, banks, and post offices, among other places. Work in this arena is defined by frequent interaction with strangers and requires on-site presence. Some work in this arena migrated to e-commerce and other digital transactions, a behavioral change that is likely to stick.

- The leisure and travel arena is home to customer-facing workers in hotels, restaurants, airports, and entertainment venues. Workers in this arena interact daily with crowds of new people. COVID-19 forced most leisure venues to close in 2020 and airports and airlines to operate on a severely limited basis. In the longer term, the shift to remote work and related reduction in business travel, as well as automation of some occupations, such as food service roles, may curtail labor demand in this arena.

- The computer-based office work arena includes offices of all sizes and administrative workspaces in hospitals, courts, and factories. Work in this arena requires only moderate physical proximity to others and a moderate number of human interactions. This is the largest arena in advanced economies, accounting for roughly one-third of employment. Nearly all potential remote work is within this arena.

- The outdoor production and maintenance arena includes construction sites, farms, residential and commercial grounds, and other outdoor spaces. COVID-19 had little impact here as work in this arena requires low proximity and few interactions with others and takes place fully outdoors. This is the largest arena in China and India, accounting for 35 to 55 percent of their workforces.

COVID-19 has accelerated three broad trends that may reshape work after the pandemic recedes

The pandemic pushed companies and consumers to rapidly adopt new behaviors that are likely to stick, changing the trajectory of three groups of trends. We consequently see sharp discontinuity between their impact on labor markets before and after the pandemic.

Remote work and virtual meetings are likely to continue, albeit less intensely than at the pandemic’s peak

Perhaps the most obvious impact of COVID-19 on the labor force is the dramatic increase in employees working remotely. To determine how extensively remote work might persist after the pandemic, we analyzed its potential across more than 2,000 tasks used in some 800 occupations in the eight focus countries. Considering only remote work that can be done without a loss of productivity, we find that about 20 to 25 percent of the workforces in advanced economies could work from home between three and five days a week. This represents four to five times more remote work than before the pandemic and could prompt a large change in the geography of work, as individuals and companies shift out of large cities into suburbs and small cities. We found that some work that technically can be done remotely is best done in person. Negotiations, critical business decisions, brainstorming sessions, providing sensitive feedback, and onboarding new employees are examples of activities that may lose some effectiveness when done remotely.

Some companies are already planning to shift to flexible workspaces after positive experiences with remote work during the pandemic, a move that will reduce the overall space they need and bring fewer workers into offices each day. A survey of 278 executives by McKinsey in August 2020 found that on average, they planned to reduce office space by 30 percent. Demand for restaurants and retail in downtown areas and for public transportation may decline as a result.

Remote work may also put a dent in business travel as its extensive use of videoconferencing during the pandemic has ushered in a new acceptance of virtual meetings and other aspects of work. While leisure travel and tourism are likely to rebound after the crisis, McKinsey’s travel practice estimates that about 20 percent of business travel, the most lucrative segment for airlines, may not return. This would have significant knock-on effects on employment in commercial aerospace, airports, hospitality, and food service. E-commerce and other virtual transactions are booming.

Many consumers discovered the convenience of e-commerce and other online activities during the pandemic. In 2020, the share of e-commerce grew at two to five times the rate before COVID-19 (Exhibit 2). Roughly three-quarters of people using digital channels for the first time during the pandemic say they will continue using them when things return to “normal,” according to McKinsey Consumer Pulse surveys conducted around the world.

Other kinds of virtual transactions such as telemedicine, online banking, and streaming entertainment have also taken off. Online doctor consultations through Practo, a telehealth company in India, grew more than tenfold between April and November 2020 . These virtual practices may decline somewhat as economies reopen but are likely to continue well above levels seen before the pandemic.

This shift to digital transactions has propelled growth in delivery, transportation, and warehouse jobs. In China, e-commerce, delivery, and social media jobs grew by more than 5.1 million during the first half of 2020.

COVID-19 may propel faster adoption of automation and AI, especially in work arenas with high physical proximity

Two ways businesses historically have controlled cost and mitigated uncertainty during recessions are by adopting automation and redesigning work processes, which reduce the share of jobs involving mainly routine tasks. In our global survey of 800 senior executives in July 2020, two-thirds said they were stepping up investment in automation and AI either somewhat or significantly. Production figures for robotics in China exceeded prepandemic levels by June 2020.

Many companies deployed automation and AI in warehouses, grocery stores, call centers, and manufacturing plants to reduce workplace density and cope with surges in demand. The common feature of these automation use cases is their correlation with high scores on physical proximity, and our research finds the work arenas with high levels of human interaction are likely to see the greatest acceleration in adoption of automation and AI.

The mix of occupations may shift, with little job growth in low-wage occupations

The trends accelerated by COVID-19 may spur greater changes in the mix of jobs within economies than we estimated before the pandemic.

We find that a markedly different mix of occupations may emerge after the pandemic across the eight economies. Compared to our pre-COVID-19 estimates, we expect the largest negative impact of the pandemic to fall on workers in food service and customer sales and service roles, as well as less-skilled office support roles. Jobs in warehousing and transportation may increase as a result of the growth in e-commerce and the delivery economy, but those increases are unlikely to offset the disruption of many low-wage jobs. In the United States, for instance, customer service and food service jobs could fall by 4.3 million, while transportation jobs could grow by nearly 800,000. Demand for workers in the healthcare and STEM occupations may grow more than before the pandemic, reflecting increased attention to health as populations age and incomes rise as well as the growing need for people who can create, deploy, and maintain new technologies (Exhibit 3).

Before the pandemic, net job losses were concentrated in middle-wage occupations in manufacturing and some office work, reflecting automation, and low- and high-wage jobs continued to grow. Nearly all low-wage workers who lost jobs could move into other low-wage occupations—for instance, a data entry worker could move into retail or home healthcare. Because of the pandemic’s impact on low-wage jobs, we now estimate that almost all growth in labor demand will occur in high-wage jobs. Going forward, more than half of displaced low-wage workers may need to shift to occupations in higher wage brackets and requiring different skills to remain employed.

As many as 25 percent more workers may need to switch occupations than before the pandemic

Given the expected concentration of job growth in high-wage occupations and declines in low-wage occupations, the scale and nature of workforce transitions required in the years ahead will be challenging, according to our research. Across the eight focus countries, more than 100 million workers, or 1 in 16, will need to find a different occupation by 2030 in our post-COVID-19 scenario, as shown in Exhibit 4. This is 12 percent more than we estimated before the pandemic, and up to 25 percent more in advanced economies (Exhibit 4).

Before the pandemic, we estimated that just 6 percent of workers would need to find jobs in higher wage occupations. In our post-COVID-19 research, we find not only that a larger share of workers will likely need to transition out of the bottom two wage brackets but also that roughly half of them overall will need new, more advanced skills to move to occupations one or even two wage brackets higher.

The skill mix required among workers who need to shift occupations has changed. The share of time German workers spend using basic cognitive skills, for example, may shrink by 3.4 percentage points, while time spend using social and emotional skills will increase by 3.2 percentage points. In India, the share of total work hours expended using physical and manual skills will decline by 2.2 percentage points, while time devoted to technological skills will rise 3.3 percentage points. Workers in occupations in the lowest wage bracket use basic cognitive skills and physical and manual skills 68 percent of the time, while in the middle wage bracket, use of these skills occupies 48 percent of time spent. In the highest two brackets, those skills account for less than 20 percent of time spent. The most disadvantaged workers may have the biggest job transitions ahead, in part because of their disproportionate employment in the arenas most affected by COVID-19. In Europe and the United States, workers with less than a college degree, members of ethnic minority groups, and women are more likely to need to change occupations after COVID-19 than before. In the United States, people without a college degree are 1.3 times more likely to need to make transitions compared to those with a college degree, and Black and Hispanic workers are 1.1 times more likely to have to transition between occupations than white workers. In France, Germany, and Spain, the increase in job transitions required due to trends influenced by COVID-19 is 3.9 times higher for women than for men. Similarly, the need for occupational changes will hit younger workers more than older workers, and individuals not born in the European Union more than native-born workers.

Companies and policymakers can help facilitate workforce transitions

The scale of workforce transitions set off by COVID-19’s influence on labor trends increases the urgency for businesses and policymakers to take steps to support additional training and education programs for workers. Companies and governments exhibited extraordinary flexibility and adaptability in responding to the pandemic with purpose and innovation that they might also harness to retool the workforce in ways that point to a brighter future of work.

Businesses can start with a granular analysis of what work can be done remotely by focusing on the tasks involved rather than whole jobs. They can also play a larger role in retraining workers, as Walmart, Amazon, and IBM have done. Others have facilitated occupational shifts by focusing on the skills they need, rather than on academic degrees. Remote work also offers companies the opportunity to enrich their diversity by tapping workers who, for family and other reasons, were unable to relocate to the superstar cities where talent, capital, and opportunities concentrated before the pandemic.

Policymakers could support businesses by expanding and enhancing the digital infrastructure. Even in advanced economies, almost 20 percent of workers in rural households lack access to the internet. Governments could also consider extending benefits and protections to independent workers and to workers working to build their skills and knowledge mid-career.

Both businesses and policymakers could collaborate to support workers migrating between occupations. Under the Pact for Skills established in the European Union during the pandemic, companies and public authorities have dedicated €7 billion to enhancing the skills of some 700,000 automotive workers, while in the United States, Merck and other large companies have put up more than $100 million to burnish the skills of Black workers without a college education and create jobs that they can fill.

The reward of such efforts would be a more resilient, more talented, and better-paid workforce—and a more robust and equitable society.

Go behind the scenes and get more insights with “ Where the jobs are: An inside look at our new Future of Work research ” from our New at McKinsey blog.

Susan Lund and Anu Madgavkar are partners of the McKinsey Global Institute, where James Manyika and Sven Smit are co-chairs and directors. Kweilin Ellingrud is a senior partner in McKinsey’s Minneapolis office. Mary Meaney is a senior partner in the Paris office. Olivia Robinson is a consultant in the London office.

This report was edited by Stephanie Strom, a senior editor with the McKinsey Global Institute, and Peter Gumbel, MGI editorial director.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

What’s next for remote work: An analysis of 2,000 tasks, 800 jobs, and nine countries

What 800 executives envision for the postpandemic workforce

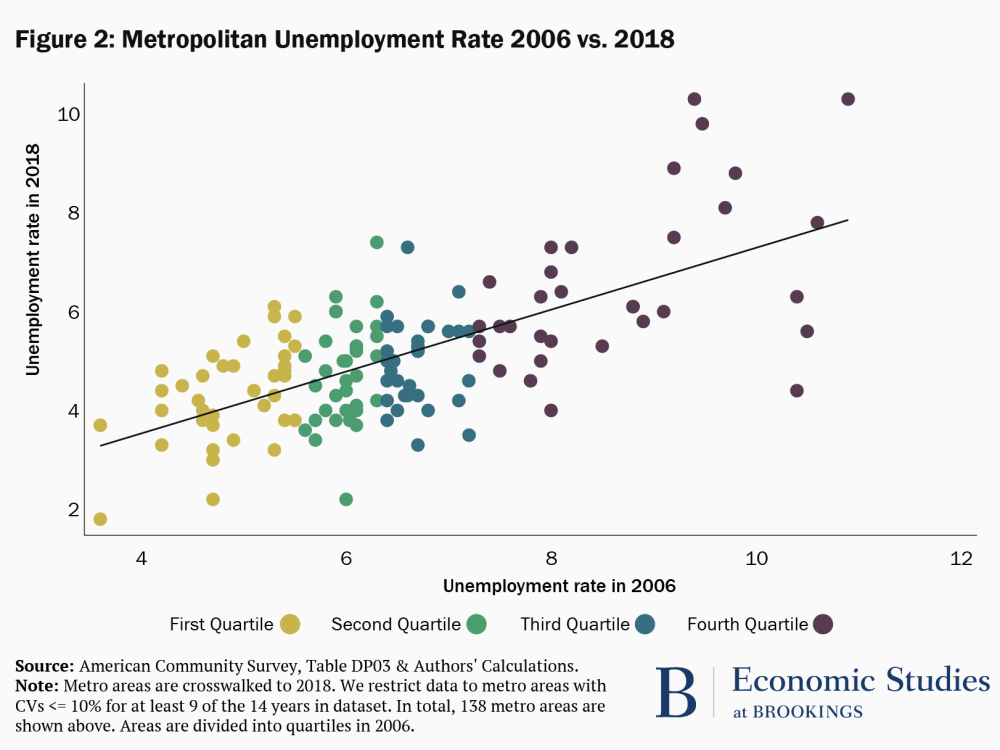

COVID-19 and jobs: Monitoring the US impact on people and places

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2021

Impact of the COVID-19 crisis on work and private life, mental well-being and self-rated health in German and Swiss employees: a cross-sectional online survey

- Martin Tušl 1 ,

- Rebecca Brauchli 1 ,

- Philipp Kerksieck 1 &

- Georg Friedrich Bauer 1

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 741 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

177k Accesses

72 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 crisis has radically changed the way people live and work. While most studies have focused on prevailing negative consequences, potential positive shifts in everyday life have received less attention. Thus, we examined the actual and perceived overall impact of the COVID-19 crisis on work and private life, and the consequences for mental well-being (MWB), and self-rated health (SRH) in German and Swiss employees.

Cross-sectional data were collected via an online questionnaire from 2118 German and Swiss employees recruited through an online panel service (18–65 years, working at least 20 h/week, various occupations). The sample provides a good representation of the working population in both countries. Using logistic regression, we analyzed how sociodemographic factors and self-reported changes in work and private life routines were associated with participants’ perceived overall impact of the COVID-19 crisis on work and private life. Moreover, we explored how the perceived impact and self-reported changes were associated with MWB and SRH.

About 30% of employees reported that their work and private life had worsened, whereas about 10% reported improvements in work and 13% in private life. Mandatory short-time work was strongly associated with perceived negative impact on work life, while work from home, particularly if experienced for the first time, was strongly associated with a perceived positive impact on work life. Concerning private life, younger age, living alone, reduction in leisure time, and changes in quantity of caring duties were strongly associated with perceived negative impact. In contrast, living with a partner or family, short-time work, and increases in leisure time and caring duties were associated with perceived positive impact on private life. Perceived negative impact of the crisis on work and private life and mandatory short-time work were associated with lower MWB and SRH. Moreover, perceived positive impact on private life and an increase in leisure time were associated with higher MWB.

The results of this study show the differential impact of the COVID-19 crisis on people’s work and private life as well as the consequences for MWB and SRH. This may inform target groups and situation-specific interventions to ameliorate the crisis.

Peer Review reports

Key findings

31% of employees perceived a negative impact of the crisis on their work life. Mandatory short-time workers and those who lost their job felt the negative impact the most.

10% of employees perceived a positive impact of the crisis on their work life. Those working in home-office, particularly if experienced for the first time, felt the positive impact the most.

30% of employees perceived a negative impact of the crisis on their private life. Living in a single household, reduction in leisure time, and changes in quantity of caring duties (i.e., increase or decrease) were strongly associated with the negative impact.

13% of employees perceived a positive impact on their private life. Living with a partner or family, mandatory short-time work, increases in leisure time and caring duties were strongly associated with the positive impact.

Perceived negative impact of the crisis on work and private life and mandatory short-time work were strongly associated with lower mental well-being and self-rated health.

Perceived positive impact of the crisis on private life and an increase in leisure time were strongly associated with higher mental well-being and, for leisure time, also with higher self-rated health.

Targeted interventions for vulnerable groups should be established on a company/governmental levels such as psychological first aid accessible online or rapid financial aids for those who have lost their income partially or completely.

Companies may consider offering positive psychology trainings to employees to help them purposefully focus on and make use of the beneficial consequences of the crisis. Such trainings may also include workshops on optimal crafting of their work and leisure time during the pandemic.

On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) [ 1 ]. In the following weeks, the virus quickly spread worldwide, forcing the governments of affected countries to implement lockdown measures to decrease transmission rates and prevent the overload of hospital emergency rooms. Switzerland entered full lockdown on March 16th, Germany followed 6 days later on March 22nd. Restrictive measures in both countries were comparable and included border controls, closing of schools, markets, restaurants, nonessential shops, bars, entertainment and leisure facilities, as well as ban on all public and private events and gatherings [ 2 , 3 ]. Such strict measures were in place until the end of April when both governments started to gradually ease the measures [ 4 , 5 ]. Consequently, much of the working population suddenly faced drastic changes to everyday life. People who commuted to work and had rich social lives outside their homes found themselves in a mandatory work from home (WFH) situation, many employees were furloughed or laid off as various businesses and industries had to shut down, and health workers in emergency rooms as well as supermarket staff and other essential employees were faced with a dramatic increase in workload and job strain [ 6 , 7 ].

Regarding the public health impact of the COVID-19 crisis, several studies suggest that working conditions have deteriorated and that employees are more likely to experience mental health problems, such as stress, depression, and anxiety [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. In particular, women, young adults, people with chronic diseases, and those who have lost their jobs as a result of the crisis seem to be the most affected [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. One of the common stressors that research has highlighted is the fear of losing one’s job and, consequently, one’s income [ 7 ]. Moreover, social isolation, conflicting messages from authorities, and an ongoing state of uncertainty have been described as some of the main factors contributing to emotional distress and negatively affecting mental health and well-being [ 8 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ].

In the European context, Eurofound [ 12 ] released a report on research in April 2020 involving 85,000 participants across 27 EU member countries. The data indicate that the EU population experienced high levels of loneliness, low levels of optimism, insecurity regarding their jobs and financial future, as well as a decrease in well-being. Germany scored slightly below the EU27 average in well-being, and there is further evidence that it decreased significantly in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, between March 2020 and May 2020 [ 19 ]. The Eurofound report does not discuss Switzerland; however, other studies suggest that there has been an increase in emotional distress in Swiss young adults [ 20 ] and that undergraduate students have experienced higher levels of stress, depression, anxiety, and loneliness compared to the time before the COVID-19 outbreak [ 14 ]. A Swiss social monitor study reports that over 40% of Swiss adults perceive a worsened quality of life compared to before the pandemic, 10% experience feelings of loneliness, 10% report fear of losing their job, and about 1% lost their job as a result of the pandemic. The report also indicates an increase in WFH by 29% compared to before the pandemic [ 21 ].

Accordingly, the data from Eurofound [ 12 ] also suggest that European employees have experienced a dramatic increase in WFH. About 37% of the EU working population transitioned to WFH as a result of the pandemic, and 24% WFH for the first time. Before the pandemic, employees had considered remote working a benefit when it followed their preferences. However, the COVID-19 lockdown changed this by forcing many employees into mandatory WFH [ 6 ]. This posed various challenges for employees without prior WFH experience, such as organizing the workspace, establishing new communication channels with colleagues, coping with work isolation, or managing boundaries between work and non-work [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]. Without proper support from the employer or insufficient resources to manage these challenges, mandatory WFH may become a burden that negatively affects employees’ well-being [ 8 ] and, in turn, their performance [ 22 ]. Furthermore, the increase in WFH has been highlighted as a potential threat to parents with small children at home, as this group is likely to experience difficulties in combining work duties with home schooling and household chores [ 12 , 23 ].

Indisputably, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a strong impact on many aspects of our lives and will continue to do so for months and years to come. However, the consequences of the crisis and societal reactions to the challenges posed by the virus are not deemed solely negative. The new situation also holds opportunities for positive shifts in our work and private lives that were impossible before the COVID-19 crisis. Many may see this crisis as an opportunity to learn how to cope with profound changes in everyday life and even to adopt new pro-active behaviors. For instance, some employees may discover that the new ways of working (e.g., WFH) facilitate more productivity and are more satisfying compared to working in an office [ 25 ]. Data collected from employees in Denmark and Germany between March and May 2020 [ 26 ] suggest that 71% of respondents felt informed and well prepared for the changing work situation and WFH. Participants also reported several advantages of working from home, such as perceived control over the workday, working more efficiently, or saving time previously spent commuting. In contrast, some reported disadvantages of WFH included social isolation, loss of the value of work, and a lack of important work equipment. Nonetheless, respondents reported overall relatively more positive experiences of WFH than negative ones. Thus, we argue that more balanced studies are needed that examine both the negative and positive impact of the COVID-19 crisis on peoples’ lives, health, and well-being, considering differential effects in diverse subgroups. Such studies have the potential to conclude how to diminish the negative and enhance the positive outcomes of the current and future pandemic-related crises in the working population.

Aim and objectives

The overall aim of the present study was to examine the actual and perceived overall impact of the COVID-19 crisis on employees’ work and private life, along with its consequences for mental well-being (MWB) and self-rated health (SRH) in the German and Swiss working populations. Specifically, we pursued the following objectives:

To investigate the perceived positive and negative impact of the COVID-19 crisis on work and private life as well as to assess the self-reported changes in work and private life routines induced by the crisis.

To examine which sociodemographic variables and which self-reported changes in work and private life routines are associated with perceived positive and negative impact of the COVID-19 crisis on work and private life.

To investigate how the self-reported changes and perceived overall impact of the COVID-19 crisis on work and private life are associated with MWB and SRH as relevant health outcomes.

Although SRH has been identified as a relevant predictor of mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 10 , 27 ], to our knowledge, it has not been studied as an outcome variable in combination with MWB indicators as in our study.

The present study used a cross-sectional online survey design. We report our study following the STROBE guidelines for cross-sectional studies [ 28 ], and the checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES) [ 29 ], see ‘Additional file 1 .pdf’ in supplementary material.

Participants were recruited through a panel data service Respondi ( respondi.com ). Cross-sectional data were collected from employees in Germany and Switzerland via an online questionnaire using a web-based survey provider SurveyGizmo. The questionnaire was tested and checked by senior researchers from the field for face validity prior to the administration. The period of data collection was from 9th to 22nd April 2020, when both countries were in full lockdown as part of the control measures relating to COVID-19. Participants received a minimal incentive for completing the survey (i.e., points which could be redeemed towards a given service after participating in several surveys). Participation was voluntary and participant anonymity and confidentiality of their data were assured and emphasized. Each participant in the online panel service database had a unique code which ensured anonymity and prevented multiple submissions from one participant. Important items in the survey were mandatory and participants were informed if they accidently skipped an item. Further, the questionnaire used a logic to avoid asking redundant or non-applicable questions (e.g., participants who indicated that they lost their job were not asked about the change in working time or home-office). Moreover, we included several disqualifying items (i.e., “Please choose number three as an answer to this item”) as a quality check to exclude participants who would give random answers. Participants were able to go back in the survey and review or change their answers.

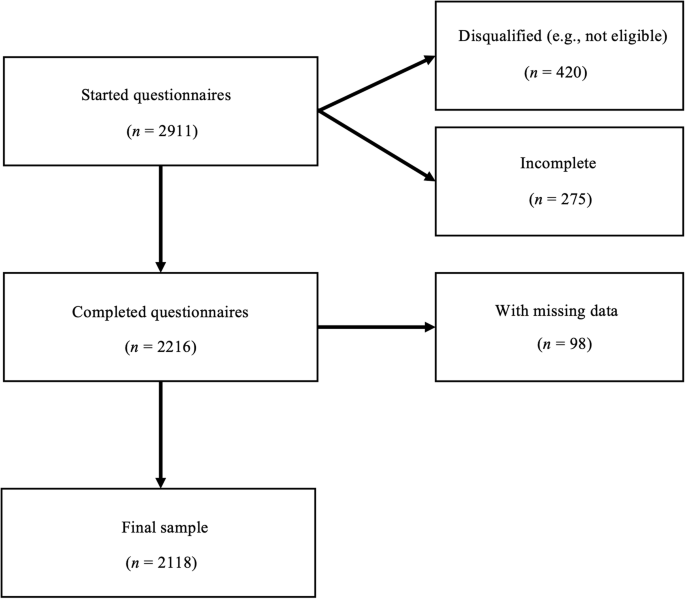

The eligibility criteria were: being employed (not self-employed), working more than 20 h per week, and being within the age range of 18 to 65 years. The final sample included 2118 participants. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram describing how the final sample was achieved.

Sample flow diagram

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1 : the mean age was 46.51 years ( SD = 11.28), 5% completed primary, 58% secondary, and 37% tertiary education, Footnote 1 55% were male, 77% were from Germany, and 72% were living with a partner, family, or in a shared housing.

Overall, in terms of age, education, and living situation (i.e., single households), the study sample seems to be a good representation of the target of the working population in Germany ( www.destatis.de ) and Switzerland ( www.bfs.admin.ch ). In general, males were slightly overrepresented in our sample (56%) compared to the general population (52%); however, the proportion of males in both countries did not differ significantly (56% from Germany, 52% from Switzerland), χ 2 (1) = 1.63, p = 0.201.

Perceived overall impact of COVID-19 on work and private life

Assuming that both improvements and deteriorations can simultaneously occur due to COVID-19, we designed four separate items (see ‘Additional file 2 .pdf’ in supplementary material) to assess participants’ subjective evaluation of the overall impact of the COVID-19 crisis on their work and private lives: “The Corona-crisis has (a) worsened my work life; (b) improved my work life; (c) worsened my private life; (d) improved my private life.” The response scale ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree . As a primer to this question, we defined the Corona-crisis as follows:

“The following questions deal directly with the current COVID-19 (Corona) pandemic and the consequent regulations from the government (i.e., business closures, school closures, event bans, contact reduction in public spaces, etc.). Hereafter, we refer to this collectively as the Corona-crisis. Please compare your current situation with the situation as it was before the government regulations.”

Changes in work and private life routines

The following items examined qualitative and quantitative changes in participants’ work and private life routines resulting from the COVID-19 crisis: (a) change in employment contract ( no change ; short-time work Footnote 2 with a reduced contract ; short-time work with a contract reduced to 0 h ; job loss ); (b) proportion of WFH before and after COVID-19 ( 0 to 100% ; participants were grouped into three categories according to their answers: None , Experienced , New Footnote 3 ); (c) changes in quantity of working time,; (d) changes in quantity of leisure time; and (e) changes in quantity of caring duties. The response scale for items c, d, and e ranged from 1 = strongly decreased to 5 = strongly increased . For the statistical analysis, responses were grouped into three categories: decreased (1 + 2), unchanged (3), increased (4 + 5).

- Mental well-being

MWB was assessed with the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) [ 30 ]. Specifically, we used the German translation of the 7-item short version of the WEMWBS [ 31 ]. WEMWBS is a measure of MWB capturing the positive aspects of mental health, namely, positive affect (feelings of optimism, relaxation), satisfying interpersonal relationships, and positive functioning (clear thinking, self-acceptance, competence, autonomy). The response scale ranged from 1 = never to 5 = all the time . For the statistical analysis (i.e., ordinal logistic regression model), we grouped participants into six categories according to their overall score in percentiles (10, 25, 50, 75, 90, 99%).

- Self-rated health

SRH was assessed with a single item: “In general, how would you evaluate your health?” [ 32 ]. The response scale ranged from 1 = very bad to 5 = very good . The application of single-item measures for self-evaluated health is a gold standard in public health research [ 33 ].

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out using R version 4.0.2. In the first step, four ordinal logistic regression models using polr from the MASS R package [ 34 ] were fitted to assess associations of the perceived overall impact of COVID-19 on work and private life as outcome variables with sociodemographic factors (gender, age, country, living situation) and factors related to changes in work and private life routines (changes in employment contract, WFH, work time, leisure time, caring duties) as independent variables. To verify that there was no multicollinearity, the variables were tested a priori using the variance inflation factor tested vif from the car R package [ 35 ] (VIF < 2). The results are presented as adjusted odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) interpreted as the OR of reporting a higher level of the impact compared to the reference category.

Further, two additional ordinal logistic regression models were fitted to investigate the association between the perceived overall impact of COVID-19 on work and private life Footnote 4 and the self-reported changes in work and private life routines as independent variables and MWB with SRH as outcome variables. In both models, we also controlled for possible confounders (gender, age, country, living situation). The results are presented as adjusted OR with 95% CI interpreted as the OR of reporting a higher level of MWB/SRH compared to the reference category.

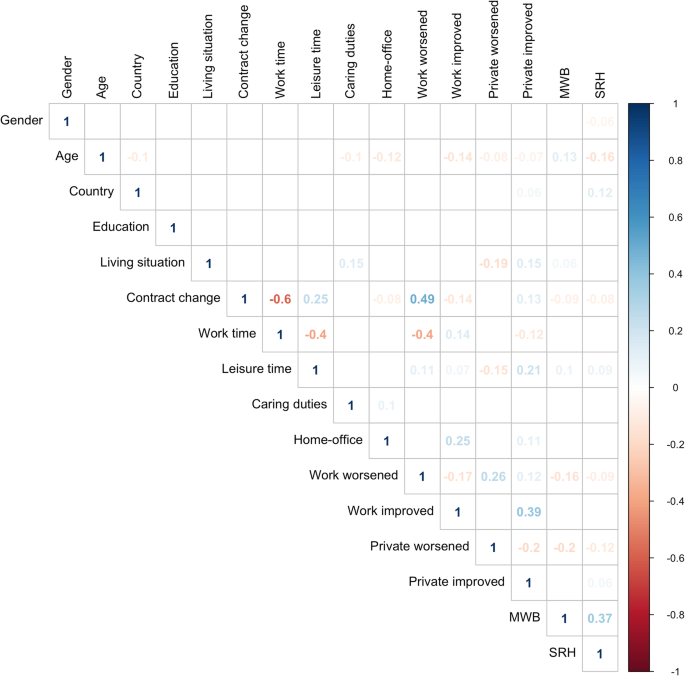

Figure 2 displays the correlations between the analyzed variables. Education was not included in the regression models due to missing data (see details in the Methods section).

Correlation matrix of the analyzed variables. Note: Only correlations with p < 0.01 displayed; Gender (1 = Female, 2 = Male); Country (1 = Germany, 2 = Switzerland); Education (1 = Primary, 2 = Secondary, 3 = Tertiary); Living situation (1 = Alone, 2 = With partner/family); Contract change (1 = No change, 2 = Short-time reduced, 3 = Short-time 0, 4 = Job loss); Home-office (1 = None, 2 = Experienced, 3 = New)

Perceived overall impact of COVID-19 crisis and self-reported changes in work and private life routines

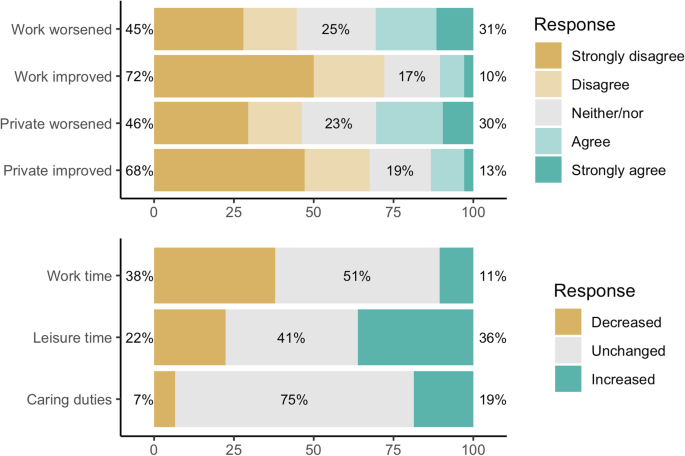

Figure 3 shows the results for the four items related to the perceived overall impact of the COVID-19 crisis on work and private life. Thirty-one percent of participants (strongly) agreed that their work life had worsened and 30% (strongly) agreed that their private life had worsened. In contrast, 10% (strongly) agreed that their work life had improved and 13% (strongly) agreed that their private life had improved as a result of the COVID-19 crisis.

Perceived impact on work and private life and self-reported changes in work time, leisure time, and caring duties. Note: Total percentage does not always equal 100% due to rounding error

Further, Fig. 3 shows self-reported changes with regard to the quantity of time actually spent in work and private life. Work time decreased for 38%, leisure time increased for 36%, while the amount of caring duties changed for 26% of participants.

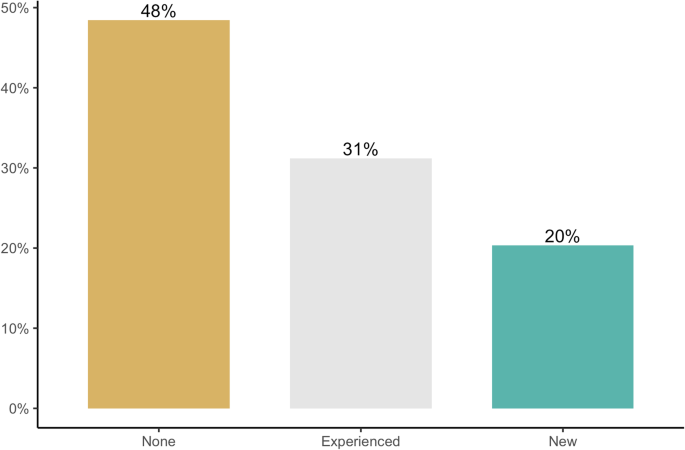

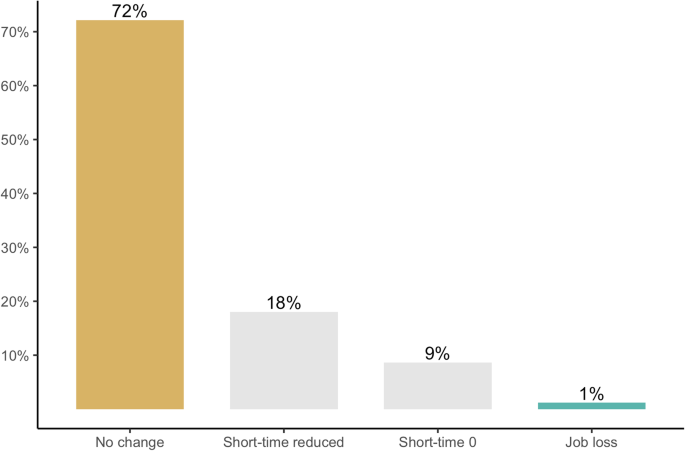

Figures 4 and 5 show self-reported changes with regard to contracted working hours and home-office. Twenty-eight percent of participants experienced a change in their employment contract, while 27% were affected by mandatory short-time work, 1% lost their job as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. Fifty-one percent reported to WFH and of those, 20% reported doing so for the first time.

Self-reported changes in home-office. Note: None = 0% WFH before COVID-19, 0% after; Experienced = at least 10% WFH before and at least 10% after COVID-19; New = 0% WFH before and at least 10% after COVID-19

Self-reported changes in contracted working hours. Note: Short-time reduced = work hours temporarily partly reduced by employer; Short time 0 = work hours temporarily reduced to 0 by employer

Factors associated with perceived impact on work life

Table 2 shows OR comparisons between different subgroups concerning their evaluation of the degree to which their work life had worsened or improved due to the COVID-19 crisis, assessed by two separate dependent variables. Regarding perceived negative impact on work life, change in employment contract demonstrated the highest OR of reporting a deterioration of work life. The association was particularly strong in participants who had their contract reduced to mandatory short-time work with 0 working hours (OR = 9.72) and in those who had lost their job (OR = 35.07). Further, participants who reported a change in their work time had a significantly higher OR of reporting a deterioration of work life (OR = 2.95; 2.06). Finally, changes in leisure time and increased caring duties were significantly associated with perceived deterioration of work life. This association was particularly strong for a decrease in leisure time (OR = 1.62) and an increase in caring duties (OR = 1.58).

Regarding perceived positive impact of COVID-19 on work life, WFH had the highest OR of reporting an improvement in work life. The association was particularly strong in those who had started to WFH for the first time (OR = 2.77). Increase in leisure time was also significantly associated with a positive impact on work life. Further, older employees in the 51–60 and 61–65 age groups had significantly lower odds of reporting a positive impact of COVID-19 on work life (OR = 0.71; 0.61), as well as short-time employees, in particular those with a contract reduced to 0 working hours (OR = 0.53), and those who reported a decrease in work time (OR = 0.61).

Factors associated with perceived impact on private life

Table 2 further shows OR comparisons within different subgroups concerning their evaluation of the degree to which their private life had worsened or improved due to the COVID-19 crisis, assessed by two separate dependent variables. Regarding perceived negative impact on private life, the subgroup of participants living with a partner, family, or in a shared housing had significantly lower odds of reporting the deterioration of their private life compared to those living alone (OR = 0.41). The odds of reporting deterioration of private life were lower also for the 61–65 age group (OR = 0.58). Finally, changes in the quantity of leisure time and quantity of caring duties were associated with perceived deterioration of private life, and this association was particularly strong for a decrease in leisure time (OR = 2.62) and a decrease in caring duties (OR = 1.62).

Regarding perceived positive impact on private life, the strongest association was with an increase in leisure time (OR = 2.25), followed by living with a partner, family, or in a shared housing (OR = 1.74); WFH, particularly among those with prior WFH experience (OR = 1.72); and with an increase in caring duties (OR = 1.33). Short-time workers had significantly higher odds of reporting a positive impact on their private life compared to workers without any change, especially those with a contract reduced to 0 working hours (OR = 1.57).

Association between the perceived impact, self-reported changes, mental well-being and self-rated health

Table 3 shows the results of the associations between perceived overall impact, the self-reported changes in work and private life routines, and relevant health outcomes in terms of MWB and SRH, controlled for various sociodemographic variables. Regarding the perceived overall impact, participants who (strongly) agreed that COVID-19 had worsened their work life reported significantly lower MWB (OR = 0.61) compared to those who (strongly) disagreed. In addition, participants who neither agreed nor disagreed that their work life had worsened reported lower MWB (OR = 0.71) compared to those who (strongly) disagreed. A strong negative association could also be seen regarding perceived negative impact on private life: participants who (strongly) agreed that their private life had worsened reported lower MWB (OR = 0.62) and SRH scores (OR = 0.67) compared to those who (strongly) disagreed. Both outcomes were also negatively associated with employees who neither agreed nor disagreed that their private life had worsened (OR = 0.80; 0.66) compared to those who (strongly) disagreed. Finally, participants who (strongly) agreed that their private life had improved as a result of the COVID-19 crisis had higher odds of reporting a higher MWB score (OR = 1.39) compared to those who (strongly) disagreed.

Regarding the impact of the self-reported changes in work and private life routines, mandatory short-time workers with a contract reduced to 0 working hours reported significantly lower MWB (OR = 0.57) and SRH (OR = 0.49) compared to participants without any change in their employment contract. In contrast, an increase in leisure time was positively associated with both better MWB (OR = 1.23) and SRH (OR = 1.45).

The present study aimed to examine the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on employees’ work and private life and the consequences for MWB and SRH in German and Swiss employees. The first objective of the study was to assess the perceived impact and self-reported changes related to COVID-19. Although the research has thus far mostly emphasized the negative impact of the COVID-19 crisis [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 36 ], our data show that more than 40% of participants perceived no negative changes and over 10% even positive shifts in both life domains. This can be partly explained by the experienced changes in daily routines: 28% of participants were affected by a change in their employment contract and 49% by changes in the quantity of work time, confirming almost identical findings for Germany in the Eurofound report [ 12 ]. Also, quantity of leisure time and of caring duties changed for 58 and 26% respectively. The finding that about half WFH at least part of their working time, and 20% for the first time is also in line with Eurofound’s data where 24% reported WFH for the first time [ 12 ]. Overall, the proportion of people affected by changes in work and private life is comparable but hardly exceeds 50%, similar to the proportion of participants who reported a deterioration in their work and private life.

The second objective was to explore the factors associated with perceived impact on work and private life. A change in contracted work hours (i.e., mandatory short-time work, job loss), and changes in work time were strongly associated with reporting deterioration of work life. Those affected by short-time work experienced a significant disruption in their work routine as well as fear of losing the job, factors associated with increased level of distress and low MWB [ 7 ]. In consequence, employees whose contract had been reduced or terminated due to the lockdown measures are particularly vulnerable to developing mental health problems [ 11 , 13 ]. Further, an increase in caring duties, and, perhaps more surprisingly, increase and decrease in leisure time were strongly associated with perceived deterioration of work life. Such changes in private life routines may require efforts for readjustments that can interfere with work and work-life balance. These readjustments may be particularly difficult for older employees (i.e., age group 61–65) who were more likely to report deterioration of their work life. They may be particularly sensitive to changes in daily structure and less flexible in adapting to a new situation, such as mandatory WFH, less personal contact with colleagues, and an increase in the use of digital technology.

WFH was most strongly associated with perceived positive impact of the COVID-19 crisis on work life, particularly in those reporting WFH for the first time, supporting evidence from Ipsen and colleagues [ 26 ]. This positive impact of WFH may be explained by a reduction or absence of commute time, more job autonomy, more flexible workdays, and ultimately, extra time for leisure. In fact, increased leisure time was another important factor associated with perceived positive impact of the COVID-19 crisis on work life. More time for leisure may allow for better recovery from work and rebuilding of personal resources [ 37 , 38 ], which can then help an individual deal with work demands. In contrast, a change in contracted working hours and a decrease in work time were negatively associated with perceived positive impact on work life. A reduction in work time may not only cause financial problems, but also reduces important daily routines and social interactions at work, and may trigger fear of losing one’s job. Again, older employees may struggle more with the new situation and may be less successful in transforming it to their benefit, explaining why the oldest age groups, 54–60 and 61–65 years, were less likely to report an improvement in their work life.

Regarding the perceived impact on private life, participants living alone were more likely to report a deterioration and less likely to report an improvement of their private life compared to those living with a partner, family, or in a shared housing. The COVID-19 lockdown substantially restricted possibilities for social interactions beyond one’s own household, particularly affecting people living alone. For individuals who live alone, this may lead to feelings of loneliness [ 12 ], which in turn, threatens their MWB [ 39 ], highlighting the importance of having opportunities for direct exchange in such a crisis situation. This could also explain that an increase in caring duties, allowing for more exchange with family members, was associated with perceived positive shifts in private life. Further, an increase in WFH showed to be beneficial also to the private life, particularly to those experienced in WFH who did not need to first establish their workspace and new routines. Increase in leisure time and, more surprisingly, mandatory short-time work were also associated with positive impact on private life, as employees can engage more freely in activities they value. Interestingly, participants over 60 years old were less likely to report a deterioration of their private life. Older employees may be less dependent on the number of social contacts beyond their household, and they may have more mature emotion regulation strategies than the younger generations [ 40 ]. Indeed, mental well-being of the German elderly population (65+) remained largely unaltered during the early COVID-19 lockdown [ 41 ].

Finally, our third objective was to investigate how the perceived overall impact and self-reported changes induced by the crisis were associated with MWB and SRH. Low SRH has been associated with increased odds of depression [ 27 ], displaying the relevance of SRH for psychologically demanding situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Our results suggest a strong negative association between the perceived negative impact on work and private life, MWB and SRH, indicating that this perception by itself is of relevance. It is of note that the perceived negative impact, particularly in private life, had such a strong association with SRH, which is more stable over time than MWB. In contrast, perceived positive impact on private life was associated with higher MWB. It seems that those who were able to cope with the COVID-19 crisis and translate the lockdown measures into some positive shifts in their private life, also benefited in terms of increased MWB.

Looking at the impact of the self-reported changes on MWB and SRH, mandatory short-time work with 0 contracted working hours was strongly associated with a lower MWB and SRH. Short-time work leads to significant losses of financial security and of daily structure and routines. Conversely, an increase in leisure time was positively associated with MWB, and the link was even stronger with SRH. More time for leisure gives extra opportunities for individuals to engage in meaningful activities that provide them with important resources that benefit their MWB and SRH. The overall strength of the associations indicates that MBW may be more affected by the perceived impact, as both are cognitive-emotional domains and are more dependent on the cognitive appraisal of one’s situation and emotional experience. SRH, on the other hand, may be more affected by actual changes in work and private life that increase or decrease opportunities to engage in activities that are perceived as beneficial to health.

Limitations and strengths

A major limitation is the cross-sectional design, which allowed only to infer associations between variables but did not provide evidence of the directions of the associations or potential causality. Furthermore, the online survey created timely data on the immediate impact of the COVID-19 crisis situation. However, the self-reported data may be influenced by common method biases [ 42 ], such as social desirability bias [ 43 ] or self-selection bias, posing potential threats to the validity of our findings. Thus, we hired a professional panel data service that guarantees collection of high quality data. Moreover, we implemented various strategies in the questionnaire such as using disqualifying items to prevent invalid answers. The sociodemographic characteristics of our sample indicate a good representation of the target population. Finally, we did not control for all variables that might have affected the results. For instance, coping with a crisis and MWB differ individually and may be influenced by variables such as personality traits, resilience, or coping style [ 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ]. However, our study aimed to provide a broad picture of both the negative and positive impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on a large, diverse sample of the working population. Thus, it was beyond the scope of this study to investigate individual differences and characteristics. In addition, a more complete, lengthy survey would have likely reduced the participation rate.

A strength of the present study is the relatively large and heterogeneous sample size that allowed us to conduct a detailed analysis and explore different subgroups within the sample. Another strength is the time point of the data collection launched at the beginning of April 2020, close to the first peak of the COVID-19 outbreak in Germany and Switzerland and onset of the related lockdown measures. This enabled us to capture a valid picture of the immediate impact of the lockdown measures. Moreover, the survey assessed the present situation, adding to the validity compared to a retrospective survey design. Finally, the combination of a subjective evaluation of the impact of the crisis with relevant, standardized public health indicators of MWB and SRH increases the relevance of the results to public health research and for policymaking.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

The present study contributes to our understanding of the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on work and private life. It provides evidence on the covariates of a more negative/positive perceived impact and on the associations with MWB and SRH in the German and Swiss working populations. Employees whose employment contract was affected by the crisis seem to have felt the greatest negative impact on their work life. This highlights the crucial role of (un−/under-)employment in a crisis, as employment is associated with several health-promoting factors that cannot be substituted in any other way [ 48 ]. Moreover, the private life of employees living alone has been affected most negatively due to social isolation. Thus, psychological first aid also accessible online should be established particularly for these vulnerable groups [ 49 ]. Employers need to assure that they keep close social ties with and emotionally support employees with reduced contract or working hours. Moreover, rapid financial aids are needed to those who have lost their income partially or completely.

Nevertheless, we should also foster positive consequences of the crisis. In general, it seems that an increase in WFH was positive for work life. Learning from the beneficial effects of WFH in a crisis can inform future organizational and legislative policies to support this form of working. As employees experienced with WFH had a stronger positive impact on private life than first-timers, future WFH policies should include offering training and exchange of experience between employees on how to establish positive routines compatible with their private life. This will help employees to proactively identify their preferences and craft their work environment accordingly [ 50 ]. Further, an increase in leisure time was particularly positive for private life. More leisure time allows for dedicating extra time to activities one enjoys, and this may be beneficial also for recovery and detachment from work [ 51 ] and for mental health in general [ 52 ]. Thus, employees could also be trained in optimal crafting of their leisure time to strengthen these beneficial effects [ 53 , 54 ].

Finally, we saw that besides the reported actual changes in work and private life, also the perception of the overall positive or negative impact is related to the health outcomes. This suggests to offer positive psychology trainings to employees helping them to purposefully focus on and make use of potential positive consequences of the crisis [ 55 , 56 , 57 ]. From a longitudinal research perspective, it would be interesting to further examine how the actual and perceived impact of the ongoing crisis as well as the associated health outcomes change over time and whether some of the new routines developed during the pandemic will be maintained in the long term.

To conclude, our study adds to recent evidence [ 58 ] that the Covid-19 crisis and related lockdown measures do not have solely negative impact. Rather, it affects vulnerable groups of individuals who need targeted support, while the majority of the population remain healthy or even experience positive shifts in their daily life.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The R code used for the statistical analysis is available in the GitHub repository: https://github.com/jesuismartin/covid

Education estimates are based on data from n = 1194 participants who took part in a subsequent wave of data collection (December 2020), missing values ( n = 924) were imputed using mice R package (for details see supplementary material). Education was not included in the regression models as the imputed data could potentially threaten the validity of our conclusions.

Short-time work is defined as “public programs that allow firms experiencing economic difficulties to temporarily reduce the hours worked while providing their employees with income support from the State for the hours not worked” (European Commission, 2020, Retrieved from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1587138033761&uri=CELEX%3A52020PC0139 ).

None = 0% WFH before COVID-19, 0% after; Experienced = at least 10% WFH before and at least 10% after COVID-19; New = 0% WFH before and at least 10% after COVID-19.

Participants were grouped into three categories according to their answers: disagree (1 + 2), neither/nor (3), agree (4 + 5).

Abbreviations

World Health Organization

Public Health Emergency of International Concern

Work from home

European Union

Confidence interval

World Health Organization. World Health Organization Director-General’s statement on IHR Emergency Committee on Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-statement-on-ihr-emergency-committee-on-novel-coronavirus- (2019-ncov). Accessed 19 May 2020.

Google Scholar

Federal Government of Switzerland. 22. March 2020: Regeln zum Corona-Virus [Rules about the Corona virus] 2020. https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/leichte-sprache/22-maerz-2020-regeln-zum-corona-virus-1733310 . Accessed 20 Feb 2021.

Federal Council of Switzerland. Federal Council declares “extraordinary situation” and introduces more stringent measures [press release]. 2020. https://www.admin.ch/gov/en/start/documentation/media-releases.msg-id-78454.html . Accessed 20 Feb 2021.

Federal Government of Switzerland. “Wir müssen ganz konzentriert weiter machen”. 2020. [“We have to stay focused”]. 2020. https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/coronavirus/bund-laender-corona-1744306 . Accessed 20 Feb 2021.

Federal Council of Switzerland. Federal Council to gradually ease measures against the new coronavirus [press release]. 2020. https://www.admin.ch/gov/en/start/documentation/media-releases.msg-id-78818.html . Accessed 20 Feb 2021.

Kniffin KM, Narayanan J, Anseel F, Antonakis J, Ashford SP, Bakker A, et al. COVID-19 and the workplace: implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am Psychol. 2020;76(1):1–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000716 .

Article Google Scholar

Koh D, Goh HP. Occupational health responses to COVID-19: what lessons can we learn from SARS? J Occup Health. 2020;62(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12128 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rodríguez-Rey R, Garrido-Hernansaiz H, Collado S. Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic among the general population in Spain. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1–23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01540 .

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729 .

Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(2):1–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213 .

Eurofound. Living, working and COVID-19: First findings – April 2020. 2020. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2020/living-working-and-covid-19-first-findings-april-2020 . Accessed 1 June 2020.

Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Idoiaga Mondragon N, Dosil Santamaría M, Picaza GM. Psychological symptoms during the two stages of lockdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak: an investigation in a sample of citizens in northern Spain. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01491 .

Elmer T, Mepham K, Stadtfeld C. Students under lockdown: comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337 .

Carvalho Aguiar Melo M, de Sousa Soares D. Impact of social distancing on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: an urgent discussion. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66:625–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020927047 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Venkatesh A, Edirappuli S. Social distancing in covid-19: what are the mental health implications? BMJ. 2020;369:1. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1379 .

Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):510–2. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2008017 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Benke C, Autenrieth LK, Asselmann E, Pané-Farré CA. Lockdown, quarantine measures, and social distancing: associations with depression, anxiety and distress at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic among adults from Germany. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113462 .

Zacher H, Rudolph C. Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol. 2020;76(1):50–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000702 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Shanahan L, Steinhoff A, Bechtiger L, Murray AL, Nivette A, Hepp U, et al. Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychol Med. 2020:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000241X .

Moser A, Carlander M, Wieser S, Hämmig O, Puhan MA, Höglinger M. The COVID-19 social monitor longitudinal online panel: real-time monitoring of social and public health consequences of the COVID-19 emergency in Switzerland. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242129 .

Ozcelik H, Barsade SG. No employee an island: workplace loneliness and job performance. AMJ. 2018;61(6):2343–66. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.1066 .

Shimazu A, Nakata A, Nagata T, Arakawa Y, Kuroda S, Inamizu N, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 for general workers. J Occup Health. 2020;62(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12132 .

Cho E. Examining boundaries to understand the impact of COVID-19 on vocational behaviors. J Vocat Behav. 2020;119:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103437 .

Kramer A, Kramer K. The potential impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on occupational status, work from home, and occupational mobility. J Vocat Behav. 2020;119:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103442 .

Ipsen C, Kirchner K, Hansen J. Experiences of working from home in times of COVID-19. International survey conducted the first months of the national lockdowns March-May, 2020. https://www.forskningsdatabasen.dk/en/catalog/2595069795 . Accessed 20 Aug 2020.

Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 .

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 .

Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):1–6. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34 .

Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S, Weich S, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63 .

Lang G, Bachinger A. Validation of the German Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS) in a community-based sample of adults in Austria: a bi-factor modelling approach. J Public Health. 2017;25(2):135–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-016-0778-8 .

Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(1):21–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/2955359 .

Bjorner JB, Fayers P, Idler E. Self-rated health. In: Fayers PM, Hays RD, editors. Assessing quality of life in clinical trials: methods and practice. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 2005. p. 309–23.

Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern applied statistics with S. New York: Springer; 2002. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-21706-2 .

Book Google Scholar

Fox J, Weisberg S. An R companion to applied regression. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2019.

Sibley CG, Greaves LM, Satherley N, Wilson MS, Overall NC, Lee CHJ, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes toward government, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2020;75(5):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000662 .

Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513 .

Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu J-P, Westman M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Ann Rev Org Psychol Org Behav. 2018;5(1):103–28. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640 .

Ahmed MZ, Ahmed O, Aibao Z, Hanbin S, Siyu L, Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092 .

Carstensen LL, Fung HH, Charles ST. Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motiv Emot. 2003;27(2):103–23. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024569803230 .

Röhr S, Reininghaus U, Riedel-Heller SG. Mental wellbeing in the German old age population largely unaltered during COVID-19 lockdown: results of a representative survey. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01889-x .

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 .

Larsen MV, Petersen MB, Nyrup J. Do Survey Estimates of the Public’s Compliance with COVID-19 Regulations Suffer from Social Desirability Bias? J Behav Public Admin. 2020;3:1–14. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/cy4hk .

Emmons RA, Diener E. Personality correlates of subjective well-being. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 1985;11(1):89–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167285111008 .

McCauley M, Minsky S, Viswanath K. The H1N1 pandemic: media frames, stigmatization and coping. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1116 .

Anglim J, Horwood S, Smillie LD, Marrero RJ, Wood JK. Predicting psychological and subjective well-being from personality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2020;146(4):279–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000226 .

Tonkin K, Malinen S, Näswall K, Kuntz JC. Building employee resilience through wellbeing in organizations. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2018;29(2):107–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21306 .

Jahoda M. Employment and unemployment: a social-psychological analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1982.

Zürcher SJ, Kerksieck P, Adamus C, Burr CM, Lehmann AI, Huber FK, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during virus epidemics in the general public, health care workers and survivors: a rapid review of the evidence. Front Public Health. 2020;8:1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.560389 .

Demerouti E. Design your own job through job crafting. Eur Psychol. 2014;19(4):237–47. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000188 .

Wendsche J, Lohmann-Haislah A. A meta-analysis on antecedents and outcomes of detachment from work. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1–24. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02072 .

Demerouti E, Mostert K, Bakker A. Burnout and work engagement: a thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs. J Occup Health Psychol. 2010;15(3):209–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019408 .

Kosenkranius M, Rink FA, de Bloom J, van den Heuvel M. The design and development of a hybrid off-job crafting intervention to enhance needs satisfaction, well-being and performance: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8224-9 .

De Bloom J, Vaziri H, Tay L, Kujanpää M. An identity-based integrative needs model of crafting: crafting within and across life domains. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(12):1423–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000495 .

Bakker A, van Woerkom M. Strengths use in organizations: a positive approach of occupational health. Can Psychol. 2018;59(1):38–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000120 .

Peláez MJ, Coo C, Salanova M. Facilitating work engagement and performance through strengths-based micro-coaching: a controlled trial study. J Happiness Stud. 2020;21(4):1265–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00127-5 .

Waters L, Algoe SB, Dutton J, Emmons R, Fredrickson BL, Heaphy E, et al. Positive psychology in a pandemic: buffering, bolstering, and building mental health. J Posit Psychol. 2021:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1871945 .

Ahrens KF, Neumann RJ, Kollmann B, Plichta MM, Lieb K, Tüscher O, et al. Differential impact of COVID-related lockdown on mental health in Germany. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):140–1. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20830 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank to Roald Pijpker from Wageningen University for his helpful comments during the final editing of the manuscript.

MT received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 801076, through the SSPH+ Global PhD Fellowship Programme in Public Health Sciences (GlobalP3HS) of the Swiss School of Public Health. RB, PK, and GB received funding from the University of Zurich Foundation. Beyond providing the funding, these funding bodies were not involved at any stage of the study.

Author information