129 Human Trafficking Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

📝 key points to use to write an outstanding human trafficking essay, 🏆 best human trafficking topic ideas & essay examples, ⭐ simple & easy human trafficking essay titles, 📌 most interesting human trafficking topics to write about, 👍 good research topics about human trafficking.

- ❓ Research Questions about Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is one of the most challenging and acute assignment topics. Students should strive to convey a strong message in their human trafficking essays.

They should discuss the existing problems in today’s world and the ways to solve them. It means that essays on human trafficking require significant dedication and research. But do not worry, we are here to help you write an outstanding essay.

Find the issue you want to discuss in your paper. There are many titles to choose from, as you can analyze the problem from various perspectives. The examples of human trafficking essay topics include:

- The problem of child trafficking in today’s world

- The causes of human trafficking

- Human trafficking: The problem of ethics and values

- The role of today’s society in fostering human trafficking

- Human trafficking as a barrier to human development

- The rate of human trafficking victims in the world’s countries

- How to prevent and stop human trafficking

Remember that you can select other human trafficking essay titles if you want. Search for them online or ask your professor for advice.

Now that you are ready to start working on your paper, you can use these key points for writing an outstanding essay:

- Study the issue you have selected and do preliminary research. Look for news articles, scholarly papers, and information from reputable websites. Do not rely on Wikipedia or related sources.

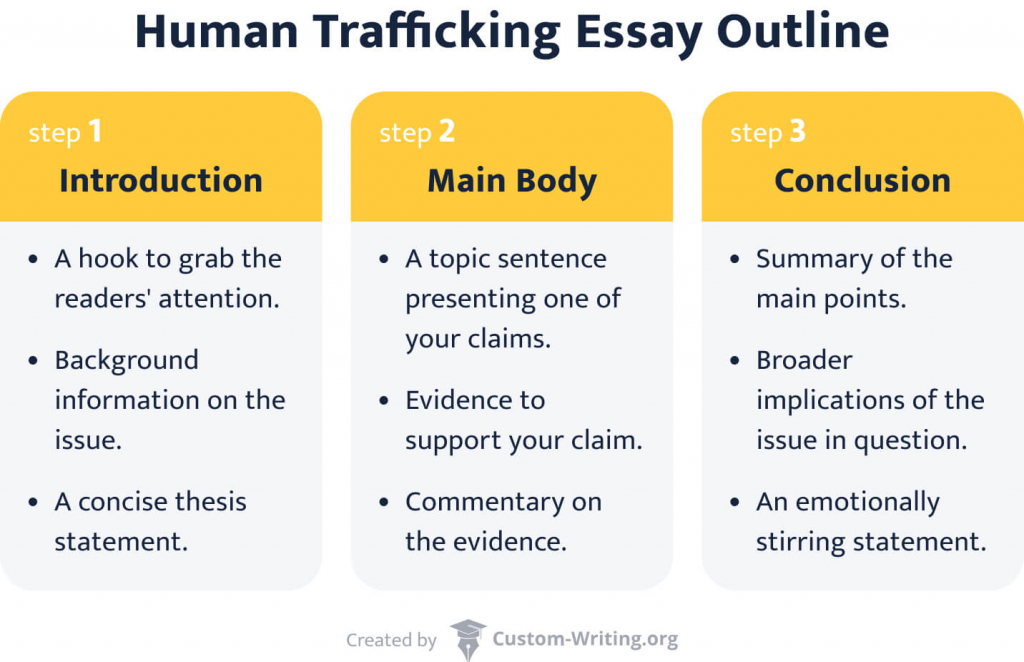

- Work on the outline for your paper. A well-developed outline is a key feature of an outstanding essay. Include an introductory and a concluding paragraph along with at least three body paragraphs. Make sure that each of your arguments is presented in a separate paragraph or section.

- Check out human trafficking essay examples online to see how they are organized. This step can also help you to evaluate the relevance of the topic you have selected. Only use online sources for reference and do not copy the information you will find.

- Your introductory paragraph should start with a human trafficking essay hook. The hooking sentence or a phrase should grab the reader’s attention. An interesting fact or a question can be a good hook. Hint: make sure that the hooking sentence does not make your paper look overly informal.

- Do not forget to include a thesis statement at the end of your introductory section. Your paper should support your thesis.

- Define human trafficking and make sure to answer related questions. Is it common in today’s world? What are the human trafficking rates? Help the reader to understand the problem clearly.

- Discuss the causes and consequences of human trafficking. Think of possible questions you reader would ask and try to answer all of them.

- Be specific. Provide examples and support your arguments with evidence. Include in-text citations if you refer to information from outside sources. Remember to use an appropriate citation style and consult your professor about it.

- Discuss the legal implications of human trafficking in different countries or states. What are the penalties for offenders?

- Address the ethical implications of the problem as well. How does human trafficking affect individuals and their families?

- A concluding paragraph should be a summary of your arguments and main ideas of the paper. Discuss the findings of your research as well.

Check out our samples (they are free!) and get the best ideas for your paper!

- Three Ethical Lenses on Human Trafficking As a result of the issue’s illegality, a deontologist will always observe the law and, as a result, will avoid or work to eradicate human trafficking.

- Human Trafficking: Process, Causes and Effects To make the matters worse they are abused and the money goes to the pockets of these greedy people as they are left empty handed after all the humiliation they go through.

- Trafficking of Children and Women: A Global Perspective The scale of women and children trafficking is very large but difficult to put a figure on the actual number of women and children trafficked all over the world. The demand for people to work […]

- Stephanie Doe: Misyar Marriage as Human Trafficking in Saudi Arabia In this article, the author seeks to highlight how the practice of temporary marriages by the wealthy in Saudi Arabia, commonly known as misyar, is a form of human trafficking.

- Human Trafficking in the United States The paper also discusses the needs of the victims of human trafficking and the challenges faced in the attempt to offer the appropriate services.

- The Human Trafficking Problem Another way is through employment and this involves the need to create more jobs within the community that is at a higher risk of facing human trafficking.

- How Prostitution Leads to Human Trafficking This is a form of a business transaction that comes in the name of commercial sex either in the form of prostitution or pornography.

- Human Trafficking: Slavery Issues These are the words to describe the experiences of victims of human trafficking. One of the best places to intercept human trafficking into the US is at the border.

- Reflection on Human Trafficking Studies When researching and critically evaluating the global issue of human trafficking, I managed to enrich my experience as a researcher, a professional, and an individual due to the facts and insights gained through this activity.

- Human Trafficking Through the General Education Lens First and foremost, the numerous initiatives show that the regional governments are prepared to respond to the problem of human trafficking in a coordinated manner.

- Discussion: Human Trafficking of Adults Human trafficking of adults is one of the most essential and significant issues of modern times, which affects the lives of millions of people in almost every corner of the globe.

- Human Trafficking and Related Issues and Tensions In the business sector, therefore, discrimination leads to the workload of the trafficked employee to make a huge lot of work to be done at the right time required.

- Doctor-Patient Confidentiality and Human Trafficking At the same time, it is obligatory to keep the records of all the patients in the healthcare settings while Dr. To conclude, the decision in the case of an encounter with human trafficking should […]

- Policy Issues on Human Trafficking in Texas The challenge of preventing human trafficking in Texas and meeting the needs of its victims is complicated by the multifaceted nature of the problem.

- Dark Window on Human Trafficking: Rhetorical Analysis In this essay, Ceaser utilized his rhetorical skills to dive into the dark world of human trafficking, which severely hits Latin America and the USA, through the usage of images and forms of different societal […]

- Human Trafficking in Africa Therefore, Africa’s human trafficking can be primarily attributed to the perennial political instability and civil unrest as the root causes of the vice in the continent. Some traditions and cultural practices in Africa have significantly […]

- Human Trafficking: Giving a Fresh Perspective One question I find reoccurring is, “Are all victims of human trafficking being dishonest?” Throughout my career and law enforcement, I met the cases in which victims were dishonest, and I wanted to discover why.

- Human Trafficking and Variety of Its Forms The types of human trafficking that harshly break human rights are sex trafficking, forced labor, and debt bondage. To conclude, it is essential to say that human trafficking has been the worst type of crime […]

- Child Welfare and Human Trafficking Young people and children that live in “out-of-home care” due to reasons of abuse or lack of resources are at higher risk of becoming subjects of trafficking.

- Human Trafficking and Healthcare Organizations Human Trafficking, which is a modern form of slavery, is a critical issue nowadays since it affects many marginalized people around the world.

- Human Trafficking Is a Global Affair It refers to the unlawful recruitment, harboring and transportation of men, women and children for forced labor, sex exploitation, forced marriages, through coercion and fraud.

- Human Trafficking and Nurses’ Education Therefore, there is a need to educate nurses in understanding human trafficking victims’ problems and learning the signs or ared flags’ of human trafficking.

- Intelligence Issues in Human Trafficking To begin with, the officer is to examine the social groups of migrants and refugees, as they are the most vulnerable groups in terms of human trafficking.

- Intelligence Issues in Border Security, Human Trafficking, and Narcotics Trafficking This paper aims to emphasize drug trafficking as the main threat for the nation and outline intelligence collecting methods on drug and human trafficking, border security, and cybersecurity.

- Human Trafficking in the UK: Examples and References The bureaucracy and lack of flexibility pose quite significant threats to the success of the UK anti-trafficking strategies. An illustration of this lack of flexibility and focus is the case of the Subatkis brothers.

- Criminology: Human Trafficking However, the UAE clearly has admitted that there is a high level of rights infringement against women by the ISIS in Iraq and Syria.

- Human Trafficking: Labor Facilitators and Programs Labor trafficking is a significant issue in the modern world because it refers to people who are forced to engage in labor through the use of coercion, fraud, and force.

- Human Trafficking: Solution to Treat Survivors And A Public Health Issues Ultimately, this led to the child’s lack of a sense of security, to the presence of a strong desire to be loved and important to someone.

- Human Trafficking and Its Social and Historical Significance Human trafficking is a type of crime that involves kidnapping and transporting of women, men, and children out of the country with the purposes of slave labor, prostitution, organ harvesting, and other nefarious purposes.

- Egypt and Sudan Refugees and Asylum Seekers Face Brutal Treatment and Human Trafficking In this report by Amnesty International, the issue of the security of refugees and asylum seekers in Shagarab refugee camps, which are located in the eastern parts of Sudan, is raised.

- Effects of Human Trafficking in Teenagers: The Present-Day Situation In this case, the inclusion of the additional factor, the type of human trafficking, will contribute to a better understanding of the problem and develop a solution.

- Aftermath of Human Trafficking in Children and Teenagers The major part of the available research is concentrated on the victims of sex abuse and the applied means of their treatment.

- Human Trafficking in the USA However, the development of the society and rise of humanism resulted in the reconsideration of the attitude towards this phenomenon and the complete prohibition of all forms of human trafficking.

- Human Trafficking and Exploitation in Modern Society It is necessary to determine the essence of human trafficking to understand the magnitude of the problem of slavery in the modern world.

- Child Welfare: Human Trafficking in San Diego The paper consists of an introduction, the consecutive sections addressing the definition of the issue, its legal background, the occurrence of child trafficking, and the interventions initiated by the authorities to fight the threat.

- Human Trafficking as an Issue of Global Importance Being a threat to global safety and well-being, the phenomenon of human trafficking has to be managed by reconsidering the existing policy statements of organizations responsible for monitoring the levels of human trafficking and preventing […]

- Psychotherapy for Victims of Human Trafficking The use of different dependent variables is the primary feature that differs a single-subject design from a program evaluation the essence of which is to cover a range of questions and evaluate them all without […]

- Human Trafficking: Enforcing Laws Worldwide This essay focuses on the issue of enforcement of laws concerning human trafficking, the influence of country prosperity on the approaches to solving this problem, the vulnerable categories at high risk of becoming victims, and […]

- Social Work: Human Trafficking and Trauma Theory One of the theoretical frameworks is trauma theory that focuses on the traumatic experiences victims are exposed to as well as the influence of these traumas on their further life.

- Human Trafficking Problems in Canada The authors describe the government’s influence on the level of human trafficking and argue that the concept of slavery is almost the same as modern human trafficking.

- Terrorism, Human Trafficking, and International Response One of the key positive results of the global counter-terrorism efforts was the reduction of Al Qaeda’s presence both globally and in the Middle East, and the enhancement of travel safety.

- Human Trafficking in Mozambique: Causes and Policies “Human Trafficking in Mozambique: Root Causes and Recommendations” is a policy paper developed by the research team of UNESCO as a powerful tool in order to analyze the situation with human trafficking in Mozambique and […]

- Human Trafficking as a Terrorist Activity The biggest problem that is worth mentioning is that it is believed that the number of such activities is growing at an incredibly fast rate, and it is important to take necessary measures to limit […]

- Human Trafficking and Modern-day Slavery One of the biggest challenges in addressing modern slavery and human trafficking is the fact that the vice is treated as a black market affair where facts about the perpetrators and the victims are difficult […]

- Combating Human Trafficking in the USA It is necessary to note, however, that numerous researchers claim that the number of human trafficking victims is quite difficult to estimate due to the lack of effective methodology.

- The Fight Against Human Trafficking Human trafficking constitutes a gross violation of the human rights of the individual as he/she is reduced to the status of a commodity to be used in any manner by the person who buys it.

- Criminal Law: Human Trafficking Promises of a good life and the absence of education opportunities for women have led to the increased levels of human trafficking.

- Human Trafficking: Definition, Reasons and Ways to Solve the Problem That is why, it becomes obvious that slavery, which is taken as the remnant of the past, prosper in the modern world and a great number of people suffer from it.

- Human Trafficking and the Trauma It Leaves Behind According to Snajdr, in the United States, most of the Black immigrants who came to the country during the colonial era were actually victims of human trafficking.

- Mexican Drug Cartels and Human Trafficking Reports from Mexico says that due to the pressure exerted on the drug cartels by the government, they have resolved in other means of getting revenue and the major one has been human trafficking alongside […]

- Human Trafficking between Africa and Europe: Security Issues This situation is usually made possible by the fact that the traffickers are usually criminal groups that have a potential to do harm to the victims and to the family of the victims.

- Tackling the Issue of Human Trafficking In Europe, prevention of human trafficking is interpreted to mean both awareness raising and active prevention activities that ideally look into the primary causes of human trafficking.

- Human trafficking in Mozambique The reason for this goes back to the fact the government in place has failed to put the interests of its people as a priority.

- “Not For Sale: End Human Trafficking and Slavery”: Campaign Critique To that extent, Not for Sale campaign attempts to enhance the ability of the people in vulnerable countries to understand the nature and form of trafficking and slavery.

- Human Trafficking in the United States: A Modern Day Slavery The question of the reasons of human trafficking is a complex one to answer since there are various causes for it, but the majors causes include; Poverty and Inequality: It is evident that human trafficking […]

- Definition of Human Rights and Trafficking One of the infamous abuses of human rights is the practice of human trafficking, which has become prevalent in the current society.

- Criminal Enforcement and Human Trafficking

- Combating Human Trafficking Should Go Towards the Recovery of The Victim

- Connections Between Human Trafficking and Environmental Destruction

- The Problems of Human Trafficking and Whether Prostitution Should Be Legal

- The Issue of Human Trafficking, a Criminal Business in the Modern Era

- The Problem of Human Trafficking in America

- Ways You Can Help Fight Human Trafficking

- Assignment on Human Trafficking and Prostitution

- The Plague of Human Trafficking in Modern Society

- Critical Thinking About International Adoptions: Saving Orphans or Human Trafficking

- The Issue of Human Trafficking and the Backlash of Saving People

- The Role of Corruption in Cambodia’s Human Trafficking

- A Theoretical Perspective on Human Trafficking and Migration-Debt Contracts

- Conditions That Allow Human Trafficking

- Understanding Human Trafficking Using Victim-Level Data

- Evaluation of the International Organization for Migration and Its Efforts to Combat Human Trafficking

- Causes and Consequences of Human Trafficking in Haiti

- Fishing in Thailand: The Issue of Overfishing, Human Trafficking and Forced Labor

- Differences Between Definitions of Human Trafficking

- Banks and Human Trafficking: Rethinking Human Rights Due Diligence

- The World Are Victims of Human Trafficking

- Understandings and Approaches to Human Trafficking in The Middle East

- The Issue of Human Trafficking, Child Prostitution and Child Soldiers

- Human Trafficking and the Trade in Sexual Slavery or Forced

- The Protection of Human Trafficking Victims by the Enforcement Bodies in Malaysia

- The Remnants of Human Trafficking Still Exists Today

- The Issue of Human Trafficking and Its Connection to Armed Conflict, Target Regions, and Sexual Exploitation

- Causes Effects of Human Trafficking

- The Issue of Human Trafficking and Forced Child Prostitution Around the World

- Assessing the Extent of Human Trafficking: Inherent Difficulties and Gradual Progress

- The Unknown About Human Trafficking

- Trafficking: Human Trafficking and Main Age

- The Issue of Human Trafficking in Thailand and South Africa

- The Tragedy of Human Trafficking

- Vertex Connectivity of Fuzzy Graphs with Applications to Human Trafficking

- Child Pornography and Its Effects on Human Trafficking

Human trafficking and exploitation: A global health concern

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdon

- Cathy Zimmerman,

Published: November 22, 2017

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002437

- Reader Comments

Citation: Zimmerman C, Kiss L (2017) Human trafficking and exploitation: A global health concern. PLoS Med 14(11): e1002437. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002437

Copyright: © 2017 Zimmerman, Kiss. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This work was supported by UKaid from the Department for International Development, grant number PO 5732. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Abbreviations: MOU, Memorandum of Understanding; PPE, personal protective equipment

Provenance: Commissioned; part of a Collection; externally peer reviewed

Summary points

- Labor migration is an economic and social mobility strategy that benefits millions of people around the world, yet human trafficking and the exploitation of low-wage workers is pervasive.

- The negative health consequences of human trafficking—and labor exploitation more generally—are sufficiently prevalent and damaging that they comprise a public health problem of global magnitude.

- Human trafficking and labor exploitation are substantial health determinants that need to be treated as preventable, drawing on public health intervention approaches that target the underlying drivers of exploitation before the harm occurs.

- Exploitative practices are commonly sustained by business models that rely on disposable labor, labyrinthine supply chains, and usurious labor intermediaries alongside weakening labor governance and protections, and underpinned by deepening social and economic divisions.

- Initiatives to address human trafficking require targeted actions to prevent the drivers of exploitation across each stage of the labor migration cycle to stop the types of harm that can lead to generational cycles of disability and disenfranchisement.

Introduction

While migration within and across national borders has been an economic and social mobility strategy that has benefited millions of people around the world, there is growing recognition that labor exploitation of migrant workers has become a problem of global proportions. Human trafficking and other forms of extreme exploitation, including forced labor and forced marriage, now collectively under the terminological umbrella “modern slavery,” are reported to affect an estimated 40.3 million people globally, with 29.4 million considered to be in situations of forced labor [ 1 ]. PLOS is launching a collection of essays and research articles on “Human Trafficking, Exploitation and Health” to increase awareness of the problem and to urge health and nonhealth professionals alike to engage in international and local responses to protect the health of individuals and populations affected by trafficking.

Human trafficking is a multidimensional human rights violation that centers on the act of exploitation. The United Nations defines trafficking in persons as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation” [ 2 ]. The elements of coercion, exploitation, and harm link human trafficking with other forms of modern slavery, forced labor and forced marriage.

In this introduction to the Collection on Human Trafficking, Exploitation and Health, we describe the magnitude of the problem, discuss the complex characteristics of trafficking, indicate the harm and associated health burden of trafficking, and offer a public health policy framework to guide robust responses to trafficking. Ultimately, however, in this introductory paper, we assert that human trafficking is a global health concern. That is, the health consequences of human trafficking are so widespread and severe that it should be addressed as a public health problem of global magnitude. Furthermore, because human trafficking has pervasive global health implications, we propose that these abuses—and perhaps labor exploitation more generally—be treated as preventable.

The dimensions of human trafficking and global health implications

Early discussions about trafficking in persons focused almost solely on sex trafficking of women and girls and drew primarily on law enforcement responses. But human trafficking is now understood more broadly to occur in a wide array of low- or no-wage hazardous labor. In fact, the contemporary amalgam of mobility and low-wage labor fosters many opportunities for labor exploitation. Men, women, and children are trafficked for various purposes, including domestic servitude, agricultural and plantation work, commercial fishing, textiles, factory labor, construction, mining, and forced sex work as well as bride trafficking and petty crime [ 3 – 5 ]. These types of abusive work situations are especially viable in low- and middle-income countries [ 6 ] where low-cost labor is in high demand and where informal and precarious employment proliferates and labor governance is weak [ 7 , 8 ]. A substantial proportion of human trafficking occurs within the same country, although international trafficking has received greater global attention [ 6 ].

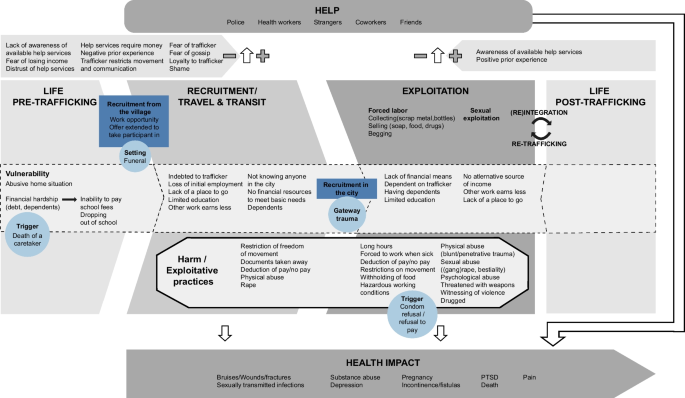

The exploitation that is at the heart of trafficking comprises different forms of abuse, such as extensive hours, poor pay, extortionate debt, physical confinement, serious occupational hazards, violence, and threats. These forms of abuse occur across a spectrum at varying levels of severity. And, importantly, the impact of exploitation on the health and wellbeing of a person who has been trafficked depends on the combination of types and severity of the acts she or he suffers ( Fig 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002437.g001

Harmful in what ways and to whom

There is growing evidence on the wide-ranging health consequences of human trafficking. A systematic review on health and human trafficking found that survivors experienced multiple forms of abuse, numerous sector-specific occupational hazards, and dangerous living conditions [ 9 ] and suffered a range of poor health consequences. Among trafficking surviors in Southeast Asia, nearly half (48%) reported physical or sexual abuse and 22% sustained severe injuries, including lost limbs, and reported symptoms indicative of depression and anxiety disorders [ 10 ]. At the same time, however, there has been limited evidence on the social, financial, and legal harm suffered by trafficked persons—which often have further implications for ill health.

Reports on human trafficking regularly highlight that child workers, minorities, and irregular migrants are at particular risk of more extreme forms of exploitation. Over half of the world’s 215 million young workers are estimated to be in hazardous sectors including forced sex work and forced street begging [ 11 ]. Ethnic minority and highly marginalized populations are known to work in some of the most exploitative and damaging sectors, such as leather tanning, mining, and stone quarry work [ 12 ]. Irregular or illegal migration status can be used to threaten and coerce workers. Poor language skills can prevent migrant workers from understanding and negotiating employment terms and enagaging in job training, and, importantly, it can hinder their understanding of local rights and assistance resources [ 13 , 14 ]. Human trafficking also frequently manifests in highly gendered ways [ 1 ]. For example, women and girls are commonly trafficked for sexual exploitation, forced marriage, and domestic work [ 1 , 4 ], while males appear to be more vulnerable to trafficking into various armed conflicts, and men in Southeast Asia are more likely than women to be recruited for commercial fishing, sometimes referred to as “sea slavery” [ 15 , 16 ]. Government can play a role in restricting migration, such as Nepal’s migration bans affecting younger prospective female migrants [ 17 ], or can promote migration through, for example, the Bangladeshi government’s Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), which subsidizes recruitment fees for females migrating to numerous Gulf States [ 18 ].

The public health burden of human trafficking and labor exploitation

Because of the challenges of conducting surveys on human trafficking, there has been little population-based prevalence data on trafficking-related morbidity and mortality. In fact, globally, there is very little research on the health of low-wage migrant workers in general, especially in low-income countries [ 19 ]. Nonetheless, broader research indicates that labor market inequalities are closely associated with mortality, healthy life expectancy, and injury rates [ 20 , 21 ]. Takala et al. suggest there are 2.3 million work-attributable deaths annually, with the greater share of work-related morbidity and injuries in low-income countries, and highlight the gradual shift of hazardous labor to Asia, in particular [ 22 ]. The economic burden of work-related injury and illness on states is also substantial, with global estimates indicating a worldwide price tag of US$2.8 trillion [ 23 ]. While it is currently not possible to know how extreme forms of exploitation might be represented in such figures, especially in hazardous sectors in low- and middle-income countries, the probability that the health burden is substantial can hardly be discounted.

Prevention: A public health approach

Recent epidemiological shifts away from infectious diseases towards noncommunicable diseases [ 24 ] has led to growing knowledge about the influence of socioeconomic and cultural determinants in mortality and morbidity patterns. This has resulted in increased recognition of the effect of precarious employment, multiple forms of marginalization, and legal and entitlement structures in individual and population health [ 14 ]. Addressing these structural determinants is at the core of effective prevention efforts for many public health problems. Extreme exploitation, like other complex social phenomena, such as violence against women or substance misuse, has multiple and interacting causes and effects [ 25 , 26 ]. Labor exploitation can be seen as a health determinant and preventable social problem and benefit from public health prevention approaches that target the harm before it occurs [ 27 ]. A prevention lens directs us to consider the interaction of multiple factors that protect or put individuals and populations at risk of labor exploitation and to seek potential mechanisms to minimize these risks or enhance protection. It also suggests that we examine how various dimensions of exploitation might contribute to aspects of harm among different populations. Moreover, from this vantage point, we might reflect somewhat provocatively on the striking similarities between the harm sustained by people who are officially identified as “trafficking victims” versus migrant workers in the same sectors [ 19 ].

A public health policy framework to address human trafficking, exploitation, and health

To prevent the exploitation of aspiring labor migrants, evidence is urgently needed on the determinants of exploitation and factors that promote safe migration and decent work. Moreover, theoretical or policy frameworks are required to look specifically at the ways that individual, group, and structural factors (including economic, social, legal, and policy-related aspects) influence exploitation and health along a migration trajectory, which can guide our search for evidence to inform interventions [ 28 – 31 ].

Fig 2 depicts factors associated with labor exploitation across a migration process, dimensions of exploitation, and various dimensions of harm. It is worth noting, however, that while structurally driven social, economic, and gendered power imbalances underpin exploitation more generally, they often manifest differently between different forms of exploitation. For example, there are critical distinctions between various types of labor trafficking and sex trafficking versus conflict-related trafficking. In many low-wage production sectors, for instance, exploitative practices are sustained by business models that rely on labyrinthine supply chains, myriad labor intermediaries, and high demand for inexpensive and disposable labor. It is not coincidental that exploitation of workers has occurred alongside the diminishing power and density of trade unions and shrinking freedom of association and collective bargaining [ 32 ]. These interactions are exacerbated by weak labor governance [ 33 ] that fails to protect workers from production processes frequently fueled by demands for low-cost goods and services—despite international conventions to protect workers [ 34 ]. The framework in Fig 2 depicts a process of complex, cumulative causation of potential harm throughout a migration cycle. It highlights interactions between macrolevel structural factors (e.g., global, national, social, etc., systems and institutions) that influence the persistence of trafficking and harm among individuals in communities (microlevels). And, while not explicit, this conceptualization also acknowledges the role of inequalities such as age, gender, nationality, ethnicity, and class [ 35 ] to each individual’s vulnerability to exploitation [ 36 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002437.g002

Labor intermediaries and migrant networks frequently play a key role in recruitment processes. Some labor recruiters may assist with job placement into decent work, while others might facilitate exploitation. Unscrupulous intermediaries are known to use extortion, deception, or coercion to exploit workers or to usher them towards abusive employers [ 37 ]. Notably, people can be recruited into trafficking situations multiple times over a single journey. Labor intermediaries can include a chain of connected or separate, formal or informal, trustworthy or untrustworthy agents. For instance, Nepali workers from rural areas often seek jobs abroad (e.g., domestic work, construction jobs) through a local agent who connects them to more formal manpower agencies in urban centers [ 38 ]. Informal migrant networks or social networks are often thought to confer greater protection from exploitation; however, this is not always the case [ 39 ]. Recent research indicated that Bolivian migrants were exploited by compatriots for textile work in Argentina, whereas the opposite was true among Kyrgyz construction workers who secured decent work in Kazakhstan through their own Kyrgyz networks [ 19 ]. Additionally, as recruitment processes or networks become more established, they can become a regular labor conduit, potentially feeding people into exploitative situations [ 40 ].

Importantly, this framework conceptualizes exploitation as a potentially preventable cause of harm [ 41 ]. This perspective incorporates forms of harm beyond physical, psychological, and occupational health problems and includes social, financial, and legal harm and further suggests that the damage from exploitation can transmit across generations.

The discussion that follows focuses primarily on trafficking of labor migrants and exploitation, but the core features underpinning exploitation, power, control, and abuse, are applicable to other forms of human trafficking (forced sex work, forced marriage, for armed conflict).

Predeparture

Most migrants leave home in search of a better life for themselves and their family, sometimes inspired by income disparities between neighboring migrant and nonmigrant households. The effects of climate change on local production, market-driven land exhaustion, humanitarian crises, and weak social assistance have each contributed in different ways to distress migration [ 42 ]. Local livelihood challenges have pushed millions of individuals away from their homes towards income opportunities that are often difficult to refuse or in which conditions are nonnegotiable—including situations of human trafficking [ 43 ]. To reduce people’s vulnerability to extreme forms of exploitation, the international community has made substantial investments in community-based awareness raising and migration knowledge building [ 44 ]. These efforts are often based on the premise that, if individuals were more informed about migrating for work, they would be less susceptible to being exploited. However, there remains little evidence to demonstrate that human trafficking is caused by information deficits among prospective migrants or about the positive effects of premigration awareness interventions [ 45 ].

People may be at greater risk of entering potentially exploitative arrangements when they are compelled to make urgent migration decisions, such as when confronted by humanitarian crises such as armed conflict, environmental disasters (tsunamis, flooding, earthquake), organized and gang violence (e.g., Northern Triangle of Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador), or personal crises such as family illness or death [ 46 – 48 ]. Household debt can push people to accept extortionate job placement or employment terms and conditions—and, conversely, people may take out loans at difficult repayment rates to fund their migration [ 49 ]. For example, 91% of Bangladeshi migrants reported multiple migration-related debts, including labor brokers’ fees [ 50 ]. Social support and job assistance schemes [ 51 ], where available, can mitigate distress migration but are sometimes perceived as inadequate to overcome financial pressures, long-term poverty, or to secure financial self-sufficiency [ 52 ].

Destination

At the work destination, labor exploitation and related abuses and their converse, ‘decent, safe employment,’ are generally determined by a combination of employment arrangements and work conditions [ 28 , 53 ]. The terms of employment set the parameters for the ways and extent to which a person can be exploited (e.g., low wages, piecework pay, extended hours, penalties for early termination of contract). For instance, among posttrafficking service users in the Mekong, an average work day (7 days per week) for fishermen was 19 hours, was 15 hours for domestic workers, and was 13 for factory workers [ 54 ]. Trafficked individuals are rarely given a contract, and if one is provided, they may not be able to read or change it [ 38 ]. Workers are rarely provided personal protective equipment (PPE) or medical insurance and few workplaces are equipped with health or safety measures, especially in less regulated sectors. Labor inspections are also uncommon, and when they do occur, inspectors are unlikely to check if workers are trafficked [ 55 ].

After being exploited, many trafficked workers are encumbered by physical and/or psychological health problems and debt. Trafficking victims seldom have access to health or social assistance or legal remedies such as financial compensation for work-related injuries or illness, disability-related lost future earnings, or unpaid wages. Debts and other financial obligations, including for medical care, can increase survivors’ vulnerability to further exploitation [ 49 ]. Additionally, returnee migrants who failed to gain the income they and their family expected commonly feel deep disappointment and sometimes stigma, which can lead to poor mental health outcomes and potential risk of retrafficking [ 56 , 57 ]. Moreover, when one family member is disabled, other family members, including children, may be pushed into exploitative situations. This can begin a generational cycle of entry into hazardous labor, such as has been observed among families and children working in palm oil plantations in Indonesia, mica mines in India, or tobacco farms in the United States [ 58 , 59 ].

Because there has been limited theoretical work conducted on labor exploitation and harm, this broad framework is meant to help guide future intervention research and prevention strategies. However, each of the categories and variables proposed must be understood within differing historical and socioeconomic contexts and the reigning political climate that might, for instance, fuel discriminatory public discourse on migrants and migrant workers.

Slavery and its like have existed for millennia; so have social and economic inequalities. Through the declaration of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, the international community has promised that efforts will be dedicated to reducing poverty, ensuring healthy lives, and, most encouragingly, promoting decent work. This brings us back to the proposition we posed initially: human trafficking should be considered a global health concern. First, in terms of prevalence, when compared with other well-recognised global health problems such as the approximately 35 million people infected with HIV or the 1 million girls under age 15 who give birth every year [ 60 , 61 ], human trafficking seems to deserve similar attention, with current estimates at approximately 40.3 million people [ 1 ]. Next, when considering harm, findings from studies around the world indicate consistently that most trafficked people experience violence and hazardous, exhausting work, and few emerge without longer-term, sometimes disabling, physical and psychological damage [ 54 ].

To date, there has been very limited engagement by the global health community in the dialogue on or responses to trafficking. Similarly, those working to address “modern slavery” have given little attention to the health impact of trafficking. So, how does one bring these communities together? As the first medical journal collection on human trafficking, exploitation, and health, the PLOS collection offers a good start towards gaining greater attention from the health sector. Providing evidence alongside expert commentary, this collection points to the range of clinical specialties and policy considerations required to address human trafficking as a global health determinant. Similarly, initiatives to tackle modern slavery, forced labor, and human trafficking need to make the links between human trafficking and health by working more closely with the health sector [ 62 ]. For both communities, a public health approach that treats the harm from exploitation as preventable will help foster interventions on the large scale that is needed. We urgently need to know more about the health burden posed by exploitative, low-wage, and hazardous labor, and, most importantly, the associated risk factors, especially in Asia and Africa—locations where some of the most exploitative labor occurs [ 63 ]. This is the type of evidentiary groundwork that was laid to address complex social problems such as intimate partner violence and that is now included in many routine health surveys and the international calculation of the Global Burden of Disease [ 25 , 64 ]. Importantly, to intervene in effective and efficient ways, evidence is also needed on the determinants of human trafficking and on who is most affected and in what ways so that precious funds for intervetions are well targeted. The ecological framework introduced in this paper might serve as a starting point to direct research to investigate key structural, social, and individual drivers of exploitation.

Moreover, a public health approach to prevent human trafficking should simultaneously generate greater attention to its less recognized sibling, labor exploitation. That is, initiatives to address human trafficking will benefit from including actions to prevent exploitation and harm among low-wage laborers, more broadly—in what is often known as 3D work: dirty, dangerous, and demeaning. A dialogue is needed about how much and in what ways low-wage workers are currently exploited and about the ways that work-related hazards might harm individuals, including by disabling parents, who may then be forced to send their children to work—perhaps producing a generational cycle of disability and disenfranchisement.

In an era in which the value of human labor appears to be systematically degraded and political rhetoric further marginalizes already disregarded migrants and disadvantaged workers, now is a propitious moment to launch, in earnest, global health actions to tackle endemic labor exploitation.

- 1. International Labor Organization. Global estimates of modern slavery: Forced labour and forced marriage. Geneva: 2017.[27 Oct 2017]. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_575479.pdf .

- 2. United Nations General Assembly. Optional Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime. 2000.[27 Oct 2017]. https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=XVIII-12-a&chapter=18&lang=en .

- 3. United States Department of State. 2016 Trafficking in Persons Report. Washington DC: 2016.[27 Oct 2017]. https://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/2016/ .

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 6. International Labor Organization. ILO global estimate of forced labor: results and methodology. Geneva: ILO, 2012.[27 Oct 2017]. file:///C:/Users/Micha/Downloads/ILO%20global%20estimate%20of%20forced%20labour.pdf.

- 7. International Labor Organization. Asian decent work decade resource kit: labour market governance. Bangkok: ILO, 2011.[27 Oct 2017]. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_098156.pdf .

- 8. Reinecke J, Donaghey J. Governance Mechanisms for Promoting Global Respect for Human Rights and Labour Standards in the Corporate Sphere: A Research Agenda for Studying their Effectiveness: Warwick Univeristy; 2016 [cited 2017 27 Oct]. [27 Oct]. http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/research/priorities/globalgovernance/themes/hrlsgg .

- 11. International Labor Organization. Children in hazardous work. Geneva: ILO, 2011.[27 Oct 2017]. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_155428.pdf .

- 12. Srivastava R. Bonded Labor in India: Its Incidence and Pattern. Geneva: 2005.[27 Oct 2017]. http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=forcedlabor .

- 15. Mendoza M, Mason M. Hawaiian seafood caught by foreign crews confined on boats: Associated Press; 2016 [27 Oct 2017]. [27 Oct 2017]. https://www.ap.org/explore/seafood-from-slaves/ .

- 16. Flynn B. Life Among the Sea Slaves. The New York Times. 2015 27 Jul 2015.[27 Oct 2017]. https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/07/27/life-among-the-sea-slaves/ .

- 17. International Labor Office. No Easy Exit: Migration Bans affecting Women from Nepal. Geneva: 2015.[27 Oct 2017]. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—declaration/documents/publication/wcms_428686.pdf .

- 18. Islam N. Gender Analysis of Migration from Bangladesh 2013 [25 August 2017]. [25 August 2017]. http://bomsa.net/Report/R1005.pdf .

- 19. Buller A, Vaca V, Stoklosa H, Borland R, Zimmerman C. Labor exploitation, trafficking and migrant health: Multi-country findings on the health risks and consequences of migrant and trafficked workers. Geneva: 2015.[27 Oct 2017]. https://publications.iom.int/books/labour-exploitation-trafficking-and-migrant-health-multi-country-findings-health-risks-and

- 23. International Labor Office. The Prevention of Occupational Diseases. Geneva: 2013.[27 Oct 2017]. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—safework/documents/publication/wcms_208226.pdf .

- 28. Benach J, Muntaner C, Santana V, Employment Conditions knowledge network (EMCONET). Final report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH). 2007.[27 Oct 2017]. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/articles/emconet_who_report.pdf .

- 33. Lee J. Global supply chain dynamics and labour governance: Implications for social upgrading 2016.[27 Oct 2017]. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—inst/documents/publication/wcms_480957.pdf .

- 34. Convention concerning Migrations in Abusive Conditions and the Promotion of Equality of Opportunity and Treatment of Migrant Workers, (1975).

- 35. Urry J. Mobilities: Polity Press; 2007.

- 36. Polaris. The Typology of Modern Slavery Defining Sex and Labor Trafficking in the United States. 2017.[27 Oct 2017]. https://polarisproject.org/sites/default/files/Polaris-Typology-of-Modern-Slavery.pdf .

- 37. Andrees B, Nasri A, Swiniarski P. Fair recruitment initiative: regulating labour recruitment to prevent human trafficking and to foster fair migration: models, challenges and opportunities. Geneva: ILO, 2015.[27 Oct 2017]. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—declaration/documents/publication/wcms_377813.pdf .

- 38. Verite. Labor Brokerage and Trafficking of Nepali Migrant Workers. Kathmandu: 2012.[27 Oct 2017]. https://www.verite.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Humanity-United-Nepal-Trafficking-Report-Final_1.pdf .

- 40. Sassen S. Immigration and Local Labor Markets. In: Portes A, editor. The Economic Sociology of Immigration: Essays on Networks, Ethnicity, and Entrepreneurship Russell Sage Foundation; 1995.

- 41. Pemberton S. Social harm and the structure of societies University of Birmingham2012 [cited 2017]. http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/accessibility/transcripts/dr-simon-pemberton-social-harm.aspx .

- 45. Zimmerman C, McAlpine A, Kiss L. Safer labour migration and community-based prevention of exploitation: The state of the evidence for programming. 2016

- 46. Lopez JA, Orellana X. The Crime No One Fights: Human Trafficking in the Northern Triangle Insight Crime: Investigation and Analysis of Organized Crime,2015 [cited 2017]. http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/human-trafficking-northern-triangle .

- 47. International Organization for Migration. Addressing human trafficking and exploitation in times of crisis: briefing document evidence and recommendations for further action to protect vulnerable and mobile populations. Geneva: 2015.[27 Oct 2017]. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/addressing_human_trafficking_dec2015.pdf .

- 48. Verite. Unaccompanied Children: Violence and Conditions in Central American Agriculture Linked to Border Crisis 2017. https://www.verite.org/unaccompanied-children-violence-and-conditions-in-central-american-agriculture-linked-to-border-crisis/ .

- 50. Rahman A. Bangladesh—Bangladesh: Safe Migration for Bangladeshi Workers 2015.[27 Oct 2017]. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/545741476894450828/pdf/ISR-Disclosable-P125302-10-19-2016-1476894433828.pdf .

- 51. Ministry of Law and Justice India. The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005. New Delhi: The Gazette of India; 2005.

- 53. International Labor Organization (ILO). Decent work—safe work. Geneve: 2005

- 55. Greenpeace. Slavery and Labour Abuse in the Fishing Sector: Greenpeace guidance for the seafood industry and government. 2016.[27 Oct 2017]. http://www.greenpeace.org/international/Global/international/briefings/oceans/2014/Slavery-and-Labour-Abuse-in-the-Fishing-Sector.pdf .

- 57. World Health Organization. Understanding and addressing violence against women: human trafficking 2012 [cited 2017 27 Oct]. [27 Oct]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77394/1/WHO_RHR_12.42_eng.pdf .

- 58. United Nations Children's Fund. Palm oil and children in Indonesia: exploring the sector's impact on children's rights. 2016.[27 Oct 2017]. https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/Palm_Oil_and_Children_in_Indonesia.pdf .

- 59. Human Rights Watch. Teens of the Tobacco Fields: Child Labor in United States Tobacco Farming. 2015.[27 Oct 2017]. https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/12/09/teens-tobacco-fields/child-labor-united-states-tobacco-farming .

- 60. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). GLOBAL HIV STATISTICS 2016 [cited 2017 27 Oct]. [27 Oct]. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf .

- 61. World Health Organization. Adolescent pregnancy 2014 [cited 2017]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs364/en/ .

- 62. United Nations. Alliance 8.7 2017. http://www.alliance87.org/ .

- 63. Kharel U. The Global Epidemic of Occupational Injuries: Counts, Costs, and Compensation Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2016. http://www.rand.org/pubs/rgs_dissertations/RGSD377.html .

Innovations in empirical research into human trafficking: introduction to the special edition

- Published: 25 July 2019

- Volume 72 , pages 1–7, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Ella Cockbain 1 &

- Edward R. Kleemans 2

6183 Accesses

14 Citations

12 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

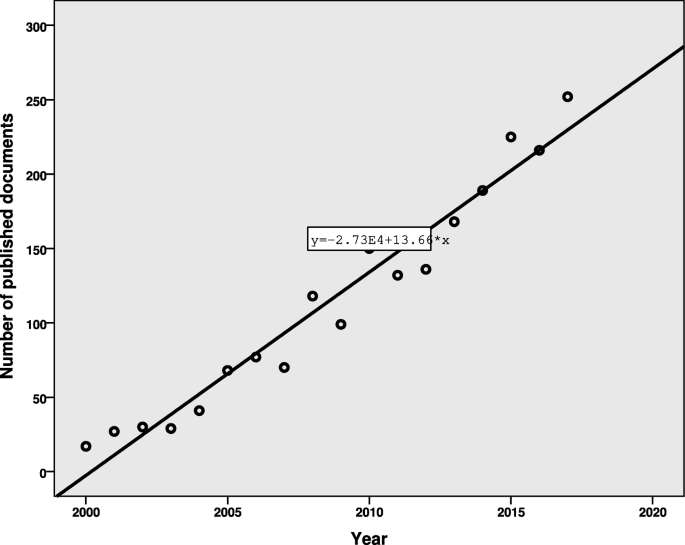

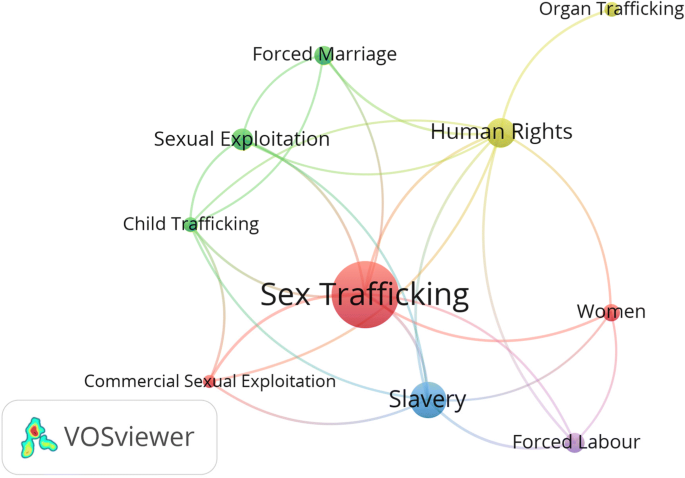

When it comes to human trafficking, hype often outweighs evidence. All too often, the discourse on trafficking – increasingly absorbed under discussions of so-called ‘modern slavery’ too – is dominated by simplistic treatments of a complex problem, sweeping claims and dubious statistics [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Such an approach might help to win attention, investment and support for an anti-trafficking agenda in the short term, but ultimately risks causing credibility problems for the entire field and contributing to ineffective, even harmful, interventions [see, e.g., 2 , 4 – 6 ]. From the 1990s onwards, levels of interest and investment in counter-trafficking expanded rapidly [ 3 , 7 , 8 ]. In tandem, the literature on trafficking has proliferated [ 9 , 10 ]. Yet, actual empirical (data-driven) research remains relatively rare [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Of course, non-empirical approaches have value too – for example in challenging how we conceptualise trafficking or highlighting tensions in governments’ or businesses’ commitments to anti-trafficking measures. Nevertheless, empirical research is clearly crucial to advance understanding of the trafficking phenomenon and shape nuanced, evidence-informed policy and practice. Even where empirical research exists, its quality can be highly variable, with many publications (even peer-reviewed ones) found to fall short of even rudimentary scientific standards [ 13 , 15 ]. Additionally, there is a particular dearth of rigorous, independent evaluations of interventions [ 7 , 13 ] – despite the many millions of dollars spent thus far on anti-trafficking efforts worldwide [ 12 , 16 ].

Before proceeding, it is worth acknowledging some fundamental tensions in researching human trafficking. First, trafficking is not a neatly delineated phenomenon that can be consistently identified and readily counted [ 1 , 2 ]. Instead, it is a relatively fuzzy social construct that exists upon what is increasingly recognised as a ‘continuum of exploitation’ running from decent conditions through to severe abuses [ 17 ]. Second, trafficking is not – and has never been – ‘discursively neutral terrain’ [ 18 ]. Instead it is contested territory that has long been tied up with broader political, economic and ideological agendas [ 3 , 19 ]. Third, trafficking is a sensitive topic involving hidden populations [ 20 ]. Whether those involved are identified at all – let alone assigned the trafficking label – is heavily contingent on other factors, ranging from victims’ willingness to disclose abuses to funding and prioritisation of counter-trafficking efforts [for further discussion, see 21 , 22 ].

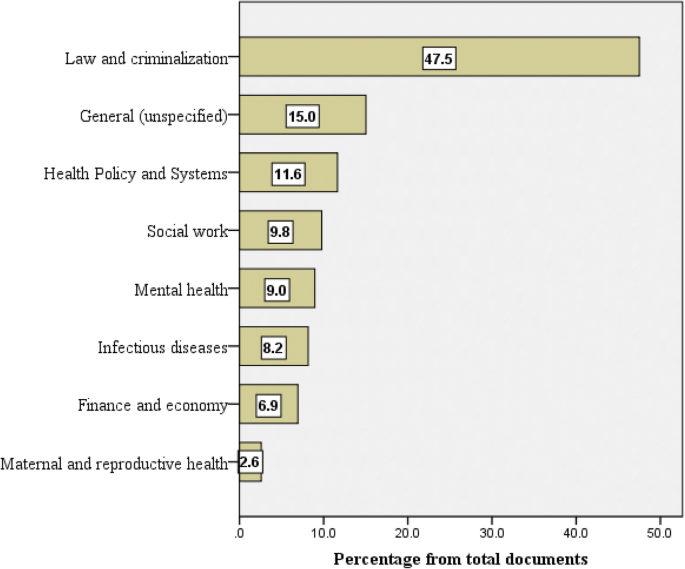

Despite these issues, it would be hard to argue that the extremes of exploitation that are – or could be – conceptualised as trafficking do not merit attention and intervention. If the trafficking field is to evolve and maintain credibility, therefore, more high-quality empirical research is needed. With so many gaps, there are many directions its expansion could take. Here, we highlight some of the gaps and limitations that are particularly pronounced and well-documented. Traditionally, research has focused overwhelmingly on sex trafficking and other trafficking types have been relatively overlooked [ 12 , 13 ]. Victim-focused research dominates the literature, leaving offenders comparatively neglected [ 23 , 24 , 25 ]. Most trafficking research is qualitative in nature and quantitative studies are far rarer, particularly those that go beyond descriptive statistics alone [ 9 , 13 ]. Accessing research data and participants is notoriously challenging and remains a key barrier to the development of the field [ 11 , 21 , 26 ]. On the one hand, existing datasets (e.g. police or other administrative data) have obvious under-tapped potential for academic research and could be used far more extensively and effectively [ 21 , 27 , 28 ]. On the other, increased investment in primary data collection – such as via survey methods – is also necessary to address questions that existing data cannot answer. Perhaps linked to difficulties accessing data, trafficking studies typically focus on a single country and robust comparative analyses across multiple jurisdictions are rare [see, e.g., 29 ]. Although researchers have often approached human trafficking through a criminological or sociological lens, trafficking is clearly not just a crime problem. Other disciplines, such as geography, public health, management and computer science (to name but a few), also clearly have much to contribute [see, e.g., 30 – 32 ]. Linked to this disciplinary expansion, pushback continues against exceptionalising trafficking: rather than treating it as the product of a few isolated criminals (i.e. ‘bad apples’), there is a need to examine more closely how exploitation can be enabled or exacerbated by broader systems (i.e. ‘bad barrels’) such as those involved in the neoliberal labour market and its regulation as well as migration policies [see, e.g., 33 – 36 ]. Finally, it is not enough just to do more research on trafficking: the research itself needs to consistently meet high standards, for example in terms of methodological transparency and rigour, solid research designs and robust ethical conduct [ 13 , 37 ].

Given this context, we are delighted this special edition begins to address many of these key gaps. The papers in it have been written by some of the world’s leading academic experts on trafficking and span a range of countries, topics and approaches. What unites the contents is a shared grounding in original, empirical research and innovative contributions to the literature, be it in thematic, methodological and/or conceptual terms. Thanks to funding from the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK, the process included a symposium in London in July 2018. Lead authors came together to present their first drafts and share their feedback on one another’s work; the resultant papers are all the stronger for the constructive criticism and vigorous debate that ensued. Overall, we are confident that this volume has much to offer for academics, policy-makers and practitioners interested in new perspectives on human trafficking. Below, we provide a short summary of each paper, followed by some brief concluding observations.

The special edition starts with a rare quantitative analysis of individual-level data on human trafficking, using data from the United Kingdom’s central system for identifying trafficking victims. For a sample of 2,630 confirmed victims, Cockbain and Bowers [ 38 ] systematically compare those trafficked for sexual exploitation, domestic servitude and (other) labour exploitation. They examine similarities and differences in terms of victim demographics, the trafficking process and official responses. They find both substantial and significant differences between types, demonstrating that human trafficking is a complex and diverse phenomenon. Although different forms of trafficking are routinely conflated in research, policy and interventions, this study highlights the value of a more nuanced approach that takes into account differences between – and indeed within – trafficking types.

Qiu, Zhang and Liu [ 39 ] provide a new perspective by focusing on trafficking for forced marriage – a particularly understudied issue – in the Chinese context. Women from poor neighbouring countries, such as Myanmar, frequently look for employment opportunities in China. Due to a severe imbalance in China’s sex ratio, a trafficking market has emerged to meet the demand for brides. The authors analyse 73 court cases involving 184 Myanmar women who were trafficked into China in the period 2003–2016. They find that most traffickers had limited education and were either unemployed or underemployed. The vast majority were Chinese nationals with good connections in both the cross-border trade and traditional matchmaking business. Most trafficking turned out to involve few formal organisational structures and occurred primarily under the guise of employment opportunities: it appeared that most victims were recruited within Myanmar in response to the offers of a job in interior China.

Wijkman and Kleemans [ 40 ] shed new light on female offenders involved in human trafficking, in particular trafficking for sexual exploitation. Analysing the court files of 150 women convicted for trafficking offences in the Netherlands, they conclude that popular conceptions of the role of women in trafficking are inaccurate and simplistic. Contrary to stereotypes of passive female victims/predatory male offenders, their analysis shows that female traffickers are neither rare nor unimportant. The roles they performed were not limited to low-ranking activities, nor were they exceptional: instead they could be similar to those of male offenders. Specific prior experiences of victimisation, such as a history of being sexually exploited, inadequately explained women’s involvement in the offending. Finally, the frequent presence of male co-offenders clearly shows that offending is embedded in social relationships, including intimate (romantic) relationships.

Brunovskis and Surtees [ 41 ] offer timely insights into the complexities of identifying trafficking victims in situations of massive and rapid transit movements. Their focus is on Europe’s so-called “refugee crisis” of 2015 and 2016. They draw on fieldwork in Serbia, where an extraordinarily high number of vulnerable migrants/refugees from different countries and cultural backgrounds passed through along the Balkan route over a short period of time. Opportunities to interact with these migrants/refugees in ways that would lead to victim identification and support proved heavily constrained. In such situations, the authors found it was difficult to set up appropriate and effective human trafficking screening mechanisms and to identify particular vulnerabilities. They conclude that the anti-trafficking framework can be difficult to apply in mass migration settings and does not always fit well with peoples’ experiences. Moreover, the protections on offer may not be suitable for or wanted by those who would be eligible.

Davies and Ollus [ 42 ] situate labour exploitation – including but not limited to trafficking at the extreme end of the spectrum – firmly within the context of developments in the economy, labour markets, and society at large. Breaking with dominant approaches to anti-trafficking that tend to centre individual offenders, they focus instead on how supply chains and business practices can enable and exacerbate the exploitation of vulnerable workers. Their analysis is based on qualitative, semi-structured interviews with both workers and supply chain stakeholders (e.g. employers, intermediaries and regulators) in the UK agri-food industry ( n = 27) and the Finnish cleaning industry ( n = 38). They identify industry dynamics, labour subcontracting and insufficient regulatory oversight as key factors in enabling exploitation in otherwise legitimate businesses. Given the significant role of corporate practices in facilitating exploitation, the authors argue in favour of framing labour exploitation as a form of corporate crime.

Van Meeteren and Wiering [ 43 ] take a fairly unusual approach in examining labour trafficking in the context of regular rather than irregular migration, specifically a labour migration scheme for the Chinese catering industry in the Netherlands. Through an in-depth qualitative analysis of investigative files from eight such cases identified as constituting labour trafficking, the authors explore various mechanisms through which exploitation is facilitated and sustained. They focus in particular on the impact of restrictions connected to regular migrant workers’ immigration status. The authors conclude that while employers and victims alike can manoeuvre within the space provided by immigration policies, these policies clearly shape relationships and dependencies in the labour market. They find, for example, that migrants’ reliance on their employers for work and residence permits makes them hesitant to disobey, run away and risk the large sums they have already invested in their migration ambitions. Tied residence and work permits emerge in this way as a particularly important contributor to vulnerability to labour exploitation.

De Vries, Nickerson, Farrell, Wittmer-Wolfe, and Bouché [ 44 ] extend research on the relationship between anti-immigration sentiment and criminal justice problems and solutions, by focusing on public support for anti-trafficking efforts in the United States. Using public opinion data from a nationally representative survey with 2,000 respondents, the authors find that anti-immigration sentiment is related to greater recognition that immigrants are vulnerable to human trafficking victimisation. While anti-immigration sentiment does not impact views on general governmental prioritization of counter-trafficking policies, it is associated with less public support for services for immigrant trafficking victims. These findings might explain why, according to the authors, public policies safeguarding migrant trafficked persons have been among the most difficult to pass in the United States, despite strong overall support for government prioritisation of anti-trafficking efforts.

Overall, this special edition covered a wide range of topics, geographies, datasets and methods. Despite the variety in the approaches, some common themes can be identified, which have important implications for research, policy and practice. First, many contributions underscore the complexity and diversity of both trafficking and counter-trafficking activity, including in terms of attributes and attitudes of victims, offenders and the general publics. Moving away from one-size-fits-all approaches is vital to become more effective at explaining and tackling this issue. Second, many papers highlight the importance of contextual factors in understanding how trafficking and exploitation are produced, sustained and exacerbated. Greater recognition of contextual factors - both at the individual- and systems-level - is crucial in supporting more nuanced responses and identifying a wider range of avenues for intervention. Third, the articles often challenge stereotypes, debunk myths and/or question assumptions about how trafficking and counter-trafficking function. With trafficking such a ‘hot’ topic, it is vital that rigorous empirical research continues to provide a measured and informed counter-balance to media and political treatments that are all too often simplistic and sensationalised.

Quirk, J. (2011). The anti-slavery project: from the slave trade to human trafficking . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Book Google Scholar

O'Connell Davidson, J. (2015). Modern slavery: the margins of freedom . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Weitzer, R. (2015). Human trafficking and contemporary slavery. Annual Review of Sociology, 41 , 223–242.

Article Google Scholar

Smith, M., & Mac, J. (2018). Revolting prostitutes: The fight for sex workers' rights . London: Verso.

Google Scholar

Zhang, S. X. (2012). Measuring labor trafficking: a research note. Crime, Law and Social Change, 58 (4), 469–482.

Fedina, L. (2015). Use and misuse of research in books on sex trafficking: implications for interdisciplinary researchers, practitioners, and advocates. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 16 (2), 188–198.

Van Der Laan, P., et al. (2011). Cross-border trafficking in human beings: prevention and intervention strategies for reducing sexual exploitation: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews (9). Available at: https://campbellcollaboration.org/media/k2/attachments/Van_der_Laan_Trafficking_Review.pdf . Accessed 22/7/19

Goodey, J. (2008). Human trafficking sketchy data and policy responses. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 8 (4), 421–442.

Laczko, F., & Gozdziak, E. (2005). Data and research on human trafficking: A global survey . Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

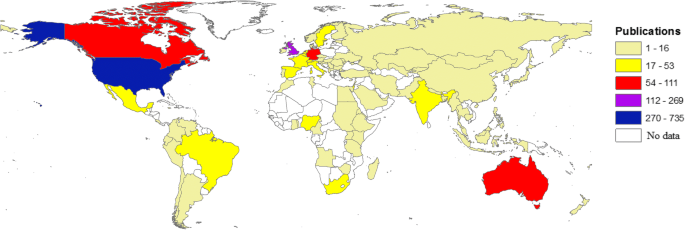

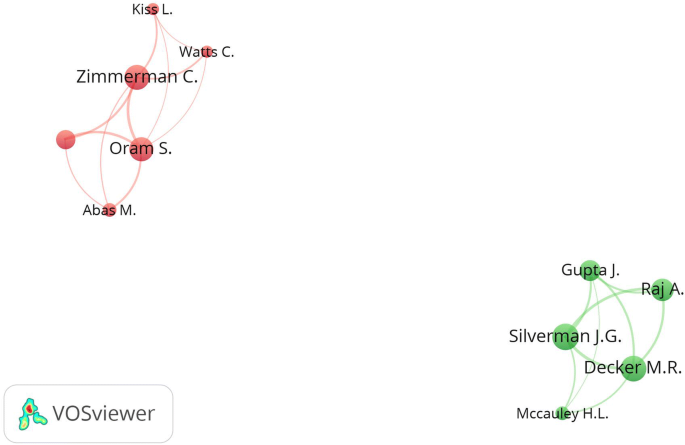

Sweileh, W. M. (2018). Research trends on human trafficking: a bibliometric analysis using Scopus database. Globalization and Health, 14 (1), 106.

Zhang, S. X. (2009). Beyond the ‘Natasha’story–a review and critique of current research on sex trafficking. Global Crime, 10 (3), 178–195.

Gozdziak, E., & Bump, M. (2008). In Georgetown University (Ed.), Data and research on human trafficking: Bibliography of research-based literature . Washington, D.C.

Cockbain, E., Bowers, K., & Dimitrova, G. (2018). Human trafficking for labour exploitation: the results of a two-phase systematic review mapping the European evidence base and synthesising key scientific research evidence. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 14 (3), 319–360.

Kleemans, E. R., & Smit, M. (2014). Human smuggling, human trafficking, and exploitation in the sex industry. In L. Paoli (Ed.), The oxford handbook of organized crime (pp. 381–401). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kelly, L. (2005). “You can find anything you want”: a critical reflection on research on trafficking in persons within and into Europe. International Migration, 43 (1–2), 235–265.

Hoff, S. (2014). Where is the funding for anti-trafficking work? A look at donor funds, policies and practices in Europe. Anti-Trafficking Review (3), 109–132.

Skrivankova, K. (2010). Between decent work and forced labour: Examining the continuum of exploitation . York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Doezema, J. (2013). Sex slaves and discourse masters: The construction of trafficking . London: Zed Books Ltd.

Weitzer, R. (2007). The social construction of sex trafficking: Ideology and institutionalization of a moral crusade. Politics and Society, 35 (3), 447–475.

Tyldum, G., & Brunovskis, A. (2005). Describing the unobserved: Methodological challenges in empirical studies on human trafficking. International Migration, 43 (1–2), 17–34.

Cockbain, E., Bowers, K., & Vernon, L. (2019). Using law enforcement data in trafficking research. In J. Winterdyk & J. Jones (Eds.), The Palgrave international handbook of human trafficking (pp. 1–25). Macmillan: Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Cockbain, E., & Olver, K. (2019). Child trafficking: Characteristics, complexities and challenges. In I. Bryce, W. Petherick, & Y. Robinson (Eds.), Child abuse and neglect: Forensic issues in evidence, impact and management (pp. 95–116). New York: Elsevier.

Chapter Google Scholar

Broad, R. (2015). ‘A vile and violent thing’: female traffickers and the criminal justice response. British Journal of Criminology, 55 (6), 1058–1075.

Cockbain, E. (2018). Offender and victim networks in human trafficking . Abingdon: Routledge.

Kleemans, E. R. (2011). Expanding the domain of human trafficking research: introduction to the special issue on human trafficking. Trends in Organized Crime, 14 (2–3), 95–99.

Tyldum, G. (2010). Limitations in research on human trafficking. International Migration, 48 (5), 1–13.

Bjelland, H. F., & Dahl, J. Y. (2017). Exploring criminal investigation practices: the benefits of analysing police-generated investigation data. European Journal of Policing Studies, 5 (2), 5–23.

Laczko, F., & Gramegna, M. A. (2003). Developing better indicators of human trafficking. The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 10 (1), 179–194.

Jokinen, A., Ollus, N., & Joutsen, M. (2013). Exploitation of migrant workers in Finland, Sweden, Estonia and Lithuania: Uncovering the links between recruitment, irregular employment practices and labour trafficking . Helsinki: HEUNI.

Oram, S., Stöckl, H., Busza, J., Howard, L. M., & Zimmerman, C. (2012). Prevalence and risk of violence and the physical, mental, and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: systematic review. PLoS Medicine, 9 (5), e1001224.

Smith, D. P. (2018). Population geography I: human trafficking. Progress in Human Geography, 42 (2), 297–308.

Crane, A., LeBaron, G., Phung, K., Behbahani, L., & Allain, J. (2018). Innovations in the business models of modern slavery: The dark side of business model innovation. In Academy of management proceedings . Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management 10510.

Gadd, D., & Broad, R. (2018). Troubling recognitions in British responses to modern slavery. The British Journal of Criminology, 58 (6), 1440–1461.

Scott, S. (2017). Labour exploitation and work-based harm . Bristol: Policy Press.

LeBaron, G. (2013). Subcontracting is not illegal, but is it unethical: Business ethics, forced labor, and economic success. The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 20 , 237.

Lewis, H., et al. (2014). Precarious lives: Forced labour, exploitation and asylum . Bristol: Policy Press.

Siegel, D., & de Wildt, R. (Eds.). (2015). Ethical concerns in research on human trafficking (Vol. 13). London: Springer.

Cockbain, E., & Bowers, K. (2019. Current issue). Human trafficking for sex, labour and domestic servitude: how do key trafficking types compare and what are their predictors? Crime, Law and Social Change . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-019-09842-9 .

Qiu, G., Zhang, S. X., & Liu, W. (2019. Current issue). Trafficking of Myanmar women for forced marriage in China. Crime, Law and Social Change . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-019-09826-9 .

Wijkman, M., & Kleemans, E. (2019. Current issue). Female offenders of human trafficking and sexual exploitation. Crime, Law and Social Change . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-019-09840-x .

Brunovskis, A., & Surtees, R. (2019. Current issue). Identifying trafficked migrants and refugees along the Balkan route. Exploring the boundaries of exploitation, vulnerability and risk. Crime, Law and Social Change . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-019-09842-9 .

Davies, J., & Ollus, N. (2019. Current issue). Labour exploitation as corporate crime and harm: outsourcing responsibility in food production and cleaning services supply chains. Crime, Law and Social Change . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-019-09842-9 .

van Meeteren, M., & Wiering, E. (2019). Labour trafficking in Chinese restaurants in the Netherlands and the role of Dutch immigration policies. A qualitative analysis of investigative case files. Crime, Law and Social Change Current issue.

de Vries, I., Nickerson, C., Farrell, A., Wittmer-Wolfe, D. E., & Bouché, V. (2019. Current issue). Anti-immigration sentiment and public opinion on human trafficking. Crime, Law and Social Change . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-019-09838-5 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK for funding the symposium in London via Dr. Ella Cockbain’s Future Research Leaders Fellowship (grant reference: ES/K008463/1). We thank the Department of Security and Crime Science at University College London for hosting the event and all who attended for their valuable contributions and feedback on others’ work. We thank all the anonymous reviewers for their generosity with their time and insightful comments. Our final thanks goes to the journal’s general editors, Professors Mary Dodge and Wim Huisman, for their support for this special edition and assistance throughout.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Security and Crime Science, University College London (UCL), London, UK

Ella Cockbain

Department of Criminal Law and Criminology, Faculty of Law, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Edward R. Kleemans

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ella Cockbain .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cockbain, E., Kleemans, E.R. Innovations in empirical research into human trafficking: introduction to the special edition. Crime Law Soc Change 72 , 1–7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-019-09852-7

Download citation

Published : 25 July 2019

Issue Date : 15 August 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-019-09852-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- MJC Library & Learning Center

- Research Guides

- Human Trafficking

Human Trafficking Research

Human trafficking: human trafficking research, start learning about your topic.

It's important to begin your research learning something about your subject; in fact, you won't be able to create a focused, manageable thesis unless you already know something about your topic.

Useful Search Terms

Use the words below to search for useful information in books including eBooks and articles.

- human trafficking

- human trafficking-prevention

- forced labor

- sex trafficking

- child soldiers

- child labor

- organ trafficking

- transplantation of organs, tissues, etc. - moral and ethical aspects

Use the Databases Below to Begin Learning About Your Topic

All of these resources are free for MJC students, faculty, & staff.

- Gale eBooks This link opens in a new window Use this database for preliminary reading as you start your research. You'll learn about your topic by reading authoritative topic overviews on a wide variety of subjects.