How Does Culture Affect Communication: Exploring the Impact, Importance & Examples

Communication is a cornerstone of our society. It helps us to build meaningful personal relationships, share ideas and create strong organizations. However, the way we communicate is influenced greatly by culture, which in turn has an undeniable impact on how efficient and effective communication is.

This article explores the importance of culture in communication and some practical examples demonstrating its profound effect. We will consider key concepts such as language styles, intercultural communication refers, barriers, and global business practices that are all pertinent facets of this topic.

By the end, readers will have a deeper understanding of how social influences shape the way we communicate.

How Does Culture Affect Communication?

Cultural differences, such as language, words, gestures, and phrases, can have a huge impact on how people communicate – like two ships passing in the night. Culture can also be a bridge between people; by understanding the culture of an other person’s culture or group, it is easier to connect and interact with each other.

Culture has an immense effect on communication – it shapes how we talk to one another, what kind of language we use, and what kinds of communication are considered appropriate. This is especially true in business settings where cultural values and norms can determine the decision-making process and the way messages are interpreted.

Frankness may be seen as normal in some cultures while frowned upon in others; this means that people from different cultures may not always understand the same message in the same way. Therefore, being mindful of cultural differences when communicating is essential for successful dialogue – like putting together pieces of a puzzle!

In conclusion, culture plays an important role when it comes to communication: from the same culture to language to beliefs, habits to customs – culture influences how we interact with each other and interpret messages. Taking these differences into account will help ensure effective communication between parties.

High and Low Context Cultures

Cross-cultural communication is a must for global harmony – but how does culture shape the way we communicate? High and low-context world cultures have distinct differences in their approach to communication. In high-context cultures, such as Japan and China, relationships are king; while in low-context countries, like the US or Germany, content is key.

The style of communication also varies between cultures: language use, words, and phrases, non-verbal cues like body language and gestures – even seating arrangements! In high-context societies, it’s all about acquiring knowledge through subtlety and indirectness, whereas, in low-context ones, it’s more about exchanging ideas directly.

Nonverbal communication can be especially tricky when navigating different cultural norms. Do you know what your facial expressions mean to someone from another country? Misunderstandings can easily arise if we don’t take into account these cultural nuances – so being aware of them is essential for effective intercultural communication and dialogue.

Culture has a profound power over how we communicate, like a sculptor chiseling away at a block of marble. Every culture has its own unique beliefs and values that shape how culture influences communication and the way people interact with each other – from social norms to decision-making processes. In some cultures, it’s polite to keep personal opinions and emotions under wraps; in others, it’s rude not to express them.

These beliefs and values also influence communication in different contexts – for instance, some cultures may require greetings before starting conversations while others don’t. And there are varying expectations for topics discussed in certain situations, such as business meetings or social gatherings.

It’s essential to recognize cultural differences when communicating with others: what is polite in one culture may be considered impolite in another! So remember this rule of thumb: respect the customs of all cultures you encounter – then your conversations will flow smoothly!

Cultural habits and customs can be compared to a powerful wave crashing onto the shore of communication. Different cultures have different ways of communicating – from body language and facial expressions to gestures. These non-verbal cues are like secret messages, conveying feelings or emotions without words. In some cultures, direct eye contact is seen as rude, while in others, it’s a sign of respect.

Habits and customs also shape how effective communication is in different contexts – like pieces on a chessboard that move around depending on the situation. For example, interrupting conversations may be acceptable in one culture but considered rude in a low-context culture in another. Additionally, expectations for directness vary between cultures too. How does culture influence communication?

Geographical factors can have a huge impact on how people and cultures communicate together. Physical distance, resources, and climate can all shape the way cultures interact. For instance, if two groups are close together, they may rely more heavily on verbal communication, while those further apart might use non-verbal cues to stay connected.

Different geographical locations also affect communication styles in other ways. Different languages may be spoken in different areas, or technology and media access could vary from place to place. Additionally, climates can influence how people communicate – for example, colder climates often lead to increased reliance on tech, while warmer ones tend to foster face-to-face communication front-to-face conversations.

In conclusion, geography plays an important role in determining how we communicate with each other – from language barriers to technological availability and even climate conditions!

What Cultural Aspects Affect Communication?

Culture can have a powerful effect on communication, like a sculptor shaping the way we understand and express ourselves. Cultural values and norms can influence our nonverbal cues – from facial expressions to body language to gestures. It can also affect how we interpret and respond to verbal and nonverbal messages. But cultural differences can create barriers to understanding, as different cultures have varying connotations for words, expectations for communication styles, and ways of expressing themselves.

When attempting to communicate effectively with people from other cultures, challenges such as language barriers or communication styles may arise. Plus, if the culture of the other person is not understood when communicating, it could lead to misunderstandings that damage trust in conversation.

That’s why it’s so important to consider cultural perspectives when communicating – interpreting information in a culture-specific way helps ensure messages are accurately conveyed and received. Cultural norms even play into how we use our hands or body language when speaking without words!

Values and Norms

Cultural values and norms can have a profound effect on how people communicate nonverbally. Different cultures have different ways of expressing themselves, such as through facial expressions, body language, and gestures. People from different cultures may interpret and respond to nonverbal communication and nonverbal communication differently, depending on their own cultural values and norms. For example, in some cultures, it is considered disrespectful to maintain eye contact with someone of higher status, while in other cultures, it is seen as a sign of respect.

Cultural values and norms can also influence how people communicate verbally. Different cultures have different expectations for communication styles and different connotations for words. For example, in some cultures, it is considered polite to be indirect when communicating, while in other cultures, it is seen as being overly polite or even disingenuous.

It is important to be aware of these cultural differences when communicating with people from different cultures in order to ensure that messages are accurately conveyed and received.

Cultural freedom is like a key that unlocks the door to honest communication. It allows people to express their thoughts and feelings without fear of judgment, encouraging openness, honesty, and mutual respect. Without it, conversations can become stifled, and trust may be lost.

Cultural freedom encourages directness in conversation, which helps ensure messages are accurately conveyed and received. This leads to more effective communication as everyone is on the same page with what’s being said. But how important is cultural freedom for successful communication?

Frankness is a cultural trait that can have a powerful impact on communication. It’s the direct and straightforward expression of thoughts and opinions without fear of judgment. Cultures that value frankness tend to be more open in their conversations, as they feel comfortable expressing themselves honestly and openly.

On the other hand, politeness is all about being respectful and courteous when talking with others. While it’s important for maintaining good relationships, too much politeness can lead to a lack of trust between people.

When communicating in different cultures, it’s essential to consider how frankness is perceived there – as what may be seen as honest in one culture could come across as rude or disrespectful in another.

Customs and traditions are a part of life, passed down from generation to generation and forming the identity of a culture. They can have an immense impact on communication between different cultures – from gestures and body language to how people interact with each other.

For instance, direct eye contact during conversations may be seen as disrespectful in some cultures while being viewed as respectful in others. Similarly, hand gestures can mean completely different things depending on where you are – a thumbs-up could be interpreted as approval or an insult!

Moreover, customs and traditions also dictate how people should greet one another; something that is considered polite in one culture might not be so in another. The use of formal languages such as honorifics, titles, and polite expressions also varies greatly between cultures.

It’s essential to understand these customs when communicating with someone from another culture if we want our messages to be accurately conveyed and received without any misunderstandings arising. Doing this will help build trust and understanding between us all!

Read also our posts about: How Communication Affects the Flow of Work in an Organization How Does Self Concept Affect Communication? Why is Feedback Needed in Interpersonal Communication How to Launch an Online Course in 2022

Tips for Effective Communication in Culture

Effective communication in a cross-cultural context is like a puzzle – it requires all the pieces to fit together. To ensure successful conversations, we must understand and appreciate cultural differences between the parties involved. Businesses must also adopt a cultural shift to make networked communication happen.

So how can we engage stakeholders and create an open and collaborative business culture? Virtual brainstorming sessions, informal company conversations during working hours, pairing different teams into virtual break-out rooms – these are just some of the approaches that can be used!

To foster open lines of communication within a company, businesses should encourage teams to exchange ideas, recognize individual contributions, respect different cultures and holidays – plus give feedback for understanding and improvement.

But what about celebrating individuals in their team? It’s important to create an inclusive environment by being aware of cultural differences, creating safe spaces for dialogue, and adapting to each other’s way of communicating. By following these tips, you’ll be well on your way toward effective communication in any cross-cultural context!

Impact, Importance & Examples

The impact of culture on communication is undeniable, and it can be a recipe for disaster if left unchecked. Cultural differences in communication styles, lack of awareness of cultural differences, and the use of language and customs that are unfamiliar to a person from a different culture can all lead to misunderstandings and conflict.

In high-context cultures and businesses, cultural diversity can have an array of effects on how people communicate with each other. Encouraging the exchange of thoughts and ideas, recognizing the significance behind words spoken, understanding context, and being aware of silence are all key components for successful business communication. When cultural differences are acknowledged and respected by companies, they open up their doors to new perspectives, which can enhance their public image as well as expand their global reach.

The big takeaway here is that when teams embrace cross-pollination, they reap better results – both in terms of effectiveness (twice as often rated by executives) but also financially (harnessing diverse ideas leads to more revenue).

Cultural sensitivity plays an important role in how companies interact with one another across cultures. Understanding beliefs, habits, and values – these things help bridge gaps between cultures so effective communication isn’t hindered by misunderstanding or miscommunication due to ignorance or prejudice. Being mindful of cultural barriers will ensure smooth sailing when communicating with people from backgrounds other than your very own culture.

To sum it up: The impact culture has on communication should not be underestimated; embracing different cultures helps foster better collaboration while understanding them prevents potential conflicts arising from miscommunication or misinterpretation due to a lack of knowledge about foreign customs or languages.

In conclusion, culture has a major influence on our interactions and communication. Our beliefs, values, habits, geography, and freedom all shape the way we communicate with one another. It is important to be conscious of cultural norms and understand how they can negatively or positively affect interpersonal communication .

This understanding of cultural differences can help businesses and employees to foster more effective communication in an international setting. To do this, companies should practice cultural sensitivity, provide the necessary education for their certain cultures, and adapt communication styles to those of different cultures.

By doing this, businesses will be better able to bridge cultural rifts, avoid miscommunication, and collaborate more successfully.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does culture affect communication examples.

Culture can greatly affect the way in which people communicate. For instance, certain cultural norms may dictate whether direct eye contact is deemed appropriate or inappropriate. Additionally, language use can differ drastically between cultures and heavily influence communication style.

It is essential to be aware of these differences in order to foster successful communication.

Why does culture influence communication?

Culture has a significant impact on the way individuals communicate, shape their communication styles, and can even determine the methods of communication used. This is because individuals are likely to be influenced by cultural elements such as values, beliefs, norms, and practices that are shared in the community.

As a result, culture plays an important role in setting the boundaries for effective communication.

What is the relationship between communication and culture?

Communication and culture are intimately connected, as communication is the method through which a culture’s cultural characteristics—customs, roles, rules, rituals, laws, and more—are created and shared.

In this way, communication plays a key role in forming and sustaining cultures.

Culture profoundly influences the way individuals communicate with one another. For example, different cultures may employ varying levels of directness or politeness in their communication styles.

Additionally, cultural norms affect word choices and the ways in which people interact with others. As such, it is essential to be mindful of how culture affects communication examples when communicating with people from various cultural backgrounds together.

I’m a student, with all due respect, I would like to ask the author about the reason behind the creation of this article. So, why did the author write the article?

read it and you will understand why.

Leave a Comment Cancel

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Email Address:

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Essay on How Does Culture Affect Communication

Students are often asked to write an essay on How Does Culture Affect Communication in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on How Does Culture Affect Communication

Introduction.

Culture shapes our life in many ways, including how we communicate. It’s like a set of unspoken rules that guide our actions. Our cultural background can influence our style of communication, the words we use, and how we understand others.

Language and Culture

The language we speak is a big part of our culture. It’s more than just words. It carries meanings and values that are important to us. For example, some cultures have many words for snow because it’s an important part of their life.

Non-Verbal Communication

Non-verbal communication, like gestures or facial expressions, is also influenced by culture. For instance, in some cultures, eye contact shows respect, while in others, it can be seen as rude.

Understanding and Misunderstandings

When people from different cultures communicate, misunderstandings can happen. This is because they might interpret words or actions differently. So, understanding other cultures can help us communicate better.

250 Words Essay on How Does Culture Affect Communication

Culture is like a big umbrella that covers the way we live, think, and communicate. It’s like a guidebook that tells us how to act or talk in different situations. So, when we talk about how culture affects communication, we’re looking at how this guidebook shapes the way we share ideas and feelings.

Language is the first thing we think of when we talk about communication. Different cultures have different languages. Even when people speak the same language, they might use different words or phrases because of their culture. For example, in the UK, people might say “lift” while in the US, people say “elevator”. So, culture influences the words we use and how we understand them.

Culture also affects non-verbal communication, which is how we talk without words. This includes things like hand gestures, eye contact, and personal space. For example, in some cultures, making direct eye contact is a sign of respect, while in others, it might be seen as rude. So, understanding a culture can help us understand these non-verbal cues.

Communication Styles

Every culture has its own style of communication. Some cultures are direct and say exactly what they mean. Others might be more indirect and use hints or suggestions. For example, in some cultures, people might say “It’s a bit cold in here” to suggest that they want the window closed. In other cultures, people might just ask directly. So, our culture shapes how we express our thoughts and needs.

In conclusion, culture is a big part of communication. It influences the language we use, the non-verbal cues we understand, and the communication style we prefer. By understanding this, we can communicate better with people from different cultures.

500 Words Essay on How Does Culture Affect Communication

Understanding culture, communication and culture.

Communication is more than just talking. It includes body language, facial expressions, and even silence. Culture plays a big role in shaping these elements. It sets the rules for what is right or wrong, polite or rude, normal or strange.

Language Differences

Culture affects the language we speak. Every culture has its own unique words, phrases, and styles of speaking. These can be very different from one culture to another. For example, in some cultures, people speak very directly. In others, people might use more indirect ways of saying things. This can cause misunderstandings if people from different cultures are not aware of these differences.

Non-verbal Communication

Understanding and respect.

Understanding and respecting other cultures is very important in communication. It helps avoid misunderstandings and conflicts. It also helps build stronger relationships. When we understand and respect other cultures, we are more likely to communicate effectively.

In conclusion, culture greatly affects communication. It shapes the way we speak, the non-verbal cues we use, and our understanding of what is polite or rude. Being aware of these cultural differences can help us communicate better with people from different cultures. It can also help us build stronger and more respectful relationships.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Culture and Communication

Introduction

7.1 Foundations of Culture and Identity

Culture is a complicated word to define, as there are at least six common ways that culture is used in the United States. For the purposes of exploring the communicative aspects of culture, we will define culture as the ongoing negotiation of learned and patterned beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors. Unpacking the definition, we can see that culture should not be conceptualized as stable and unchanging. Culture is “negotiated.” It is also dynamic, and cultural changes can be traced and analyzed to better understand why our society is the way it is. The definition also points out that culture is learned, which accounts for the importance of socializing institutions like family, school, peers, and the media. Culture is patterned in that there are recognizable widespread similarities among people within a cultural group. There is also deviation from and resistance to those patterns by individuals and subgroups within a culture, which is why cultural patterns change over time. Last, the definition acknowledges that culture influences our beliefs about what is true and false, our attitudes (including our likes and dislikes), our values regarding what is right and wrong, and our behaviors. It is from these cultural influences that our identities are formed.

Personal, Social, and Cultural Identities

Ask yourself the question “Who am I?” We develop a sense of who we are based on what is reflected back on us from other people. Our parents, friends, teachers, and the media help shape our identities. While this happens from birth, most people in Western societies reach a stage in adolescence where maturing cognitive abilities and increased social awareness lead them to begin to reflect on who they are. This begins a lifelong process of thinking about who we are now, who we were before, and who we will become (Tatum, 2000). Our identities make up an important part of our self-concept and can be broken down into three main categories: personal, social, and cultural identities.

We must avoid the temptation to think of our identities as constant. Instead, our identities are formed through processes that started before we were born. And they will continue after we are gone. Therefore, our identities are not something we achieve or complete. Two related but distinct components of our identities are our personal and social identities (Spreckels & Kotthoff, 2009). Personal identities include the components of self that are primarily intrapersonal and connected to our life experiences. Our social identities are the components of self that are derived from involvement in social groups with which we are interpersonally committed.

For example, we may derive aspects of our social identity from our family or from a community of fans for a sports team. Social identities differ from personal identities because they are externally organized through membership. Our membership may be voluntary (Greek organization on campus) or involuntary (family) and explicit (we pay dues to our labor union) or implicit (we purchase and listen to hip-hop music). There are innumerous options for personal and social identities. While our personal identity choices express who we are, our social identities align us with particular groups. Through our social identities, we make statements about who we are and who we are not.

[table id=2 /]

Personal identities may change often as people have new experiences and develop new interests and hobbies. A current interest in online video games may give way to an interest in graphic design. Social identities do not change as often because they take more time to develop, as you must become interpersonally invested. For example, if an interest in online video games leads someone to become a member of a MMORPG, or a massively multiplayer online role-playing game community, that personal identity has led to a social identity that is now interpersonal and more entrenched.

Cultural identities are based on socially constructed categories that teach us a way of being and include expectations for social behavior or ways of acting (Yep, 1998). Since we are often a part of them since birth, cultural identities are the least changeable of the three. The ways of being and the social expectations for behavior within cultural identities do change over time, but what separates them from most social identities is their historical roots (Collier, 1996). For example, think of how ways of being and acting have changed for African Americans since the civil rights movement. Additionally, common ways of being and acting within a cultural identity group are expressed through communication. In order to be accepted as a member of a cultural group, members must be acculturated, essentially learning and using a code that other group members will be able to recognize. We are acculturated into our various cultural identities in obvious and less obvious ways. We may literally have a parent or friend tell us what it means to be a man or a woman. We may also unconsciously consume messages from popular culture that offer representations of gender.

Difference Matters

Whenever we encounter someone, we notice similarities and differences. While both are important, often the differences are highlighted. These differences contribute to communication troubles. We do not only see similarities and differences on an individual level. In fact, we also place people into in-groups and out-groups based on the similarities and differences we perceive. This is important because we then tend to react to someone we perceive as a member of an out-group based on the characteristics we attach to the group rather than the individual (Allen, 2011). In these situations, it is more likely that stereotypes and prejudice will influence our communication. Learning about difference and why they matter will help us be more competent communicators. The other side of emphasizing difference is to claim that no differences exist and that you see everyone as a human being. Rather than trying to ignore difference and see each person as a unique individual, we should know the history of how differences came to be so socially and culturally significant and how they continue to affect us today.

Culture and identity are complex. You may be wondering how some groups came to be dominant and others non-dominant. These differences are not natural, which can be seen as we unpack how various identities have changed over time in the next section. There is, however, an ideology of domination that makes it seem natural and normal that some people or groups will always have power over others (Allen, 2011). In fact, hierarchy and domination, although prevalent throughout modern human history, were likely not the norm among early humans. So one of the first reasons difference matters is that people and groups are treated unequally, and better understanding how those differences came to be can help us create a more just society. Difference also matters because demographics and patterns of interaction are changing.

In the United States, the population of people of color is increasing and diversifying, and visibility for people who are gay or lesbian and people with disabilities has also increased. The 2010 Census shows that the Hispanic and Latino/a populations in the United States are now the second largest group in the country, having grown 43 percent since the last census in 2000 (Saenz, 2011). By 2030, racial and ethnic minorities will account for one-third of the population (Allen, 2011). Additionally, legal and social changes have created a more open environment for sexual minorities and people with disabilities. These changes directly affect our interpersonal relationships. The workplace is one context where changing demographics has become increasingly important. Many organizations are striving to comply with changing laws by implementing policies aimed at creating equal access and opportunity. Some organizations are going further than legal compliance to try to create inclusive climates where diversity is valued because of the interpersonal and economic benefits it has the potential to produce.

We can now see that difference matters due to the inequalities that exist among cultural groups and due to changing demographics that affect our personal and social relationships. Unfortunately, many obstacles may impede our valuing of difference (Allen, 2011). Individuals with dominant identities may not validate the experiences of those in non-dominant groups because they do not experience the oppression directed at those with non-dominant identities. Further, they may find it difficult to acknowledge that not being aware of this oppression is due to privilege associated with their dominant identities. Because of this lack of recognition of oppression, members of dominant groups may minimize, dismiss, or question the experiences of non-dominant groups and view them as “complainers” or “whiners.” Recall from our earlier discussion of identity formation that people with dominant identities may stay in the unexamined or acceptance stages for a long time. Being stuck in these stages makes it much more difficult to value difference.

Members of non-dominant groups may have difficulty valuing difference due to negative experiences with the dominant group, such as not having their experiences validated. Both groups may be restrained from communicating about difference due to norms of political correctness, which may make people feel afraid to speak up because they may be perceived as insensitive or racist. All these obstacles are common and they are valid. However, as we will learn later, developing intercultural communication competence can help us gain new perspectives, become more mindful of our communication, and intervene in some of these negative cycles.

7.2 Exploring Specific Cultural Identities

We can get a better understanding of current cultural identities by unpacking how they came to be. By looking at history, we can see how cultural identities that seem to have existed forever actually came to be constructed for various political and social reasons and how they have changed over time. Communication plays a central role in this construction. As we have already discussed, our identities are relational and communicative; they are also constructed. Social constructionism is a view that argues the self is formed through our interactions with others and in relationship to social, cultural, and political contexts (Allen, 2011). In this section, we will explore how the cultural identities of race, gender, sexual orientation, and ability have been constructed in the United States and how communication relates to those identities. Other important identities could be discussed, like religion, age, nationality, and class. Although they are not given their own section, consider how those identities may intersect with the identities discussed next.

Would it surprise you to know that human beings, regardless of how they are racially classified, share 99.9 percent of their DNA? This finding by the Human Genome Project asserts that race is a social construct, not a biological one. The American Anthropological Association agrees, stating that race is the product of “historical and contemporary social, economic, educational, and political circumstances” (Allen, 2011). Therefore, we will define race as a socially constructed category based on differences in appearance that has been used to create hierarchies that privilege some and disadvantage others.

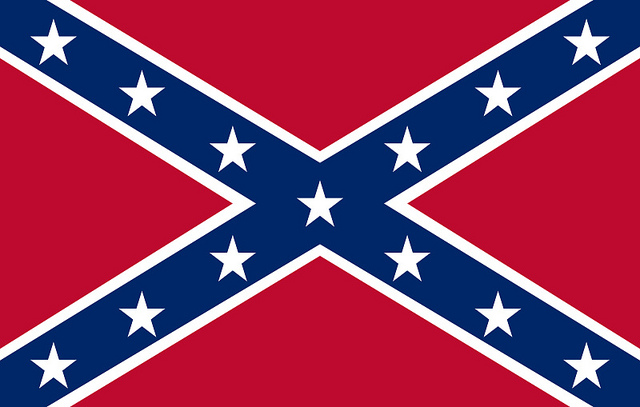

Race did not become a socially and culturally recognized marker until European colonial expansion in the 1500s. As Western Europeans traveled to parts of the world previously unknown to them and encountered people who were different from them, a hierarchy of races began to develop that placed lighter skinned Europeans above darker skinned people. At the time, newly developing fields in natural and biological sciences took interest in examining the new locales, including the plant and animal life, natural resources, and native populations. Over the next three hundred years, science that we would now undoubtedly recognize as flawed, biased, and racist legitimated notions that native populations were less evolved than white Europeans were, often calling them savages. In fact, there were scientific debates as to whether some of the native populations should be considered human or animal. Racial distinctions have been based largely on phenotypes, or physiological features such as skin color, hair texture, and body/facial features. Western “scientists” used these differences as “proof” that native populations were less evolved than the Europeans, which helped justify colonial expansion, enslavement, genocide, and exploitation on massive scales (Allen, 2011). Even though there is a consensus among experts that race is social rather than biological, we cannot deny that race still has meaning in our society and affects people as if it were “real.”

Given that race is one of the first things we notice about someone, it is important to know how race and communication relate (Allen, 2011). Discussing race in the United States is difficult for many reasons. One is due to uncertainty about language use. People may be frustrated by their perception that labels change too often or be afraid of using an “improper” term and being viewed as racially insensitive. It is important, however, that we not let political correctness get in the way of meaningful dialogues and learning opportunities related to difference. Learning some of the communicative history of race can make us more competent communicators and open us up to more learning experiences.

Racial classifications used by the government and our regular communication about race in the United States have changed frequently, which further points to the social construction of race. Currently, the primary racial groups in the United States are African American, Asian American, European American, Latino/a, and Native American, but a brief look at changes in how the US Census Bureau has defined race clearly shows that this hasn’t always been the case (see table 7.2). In the 1900s alone, there were twenty-six different ways that race was categorized on census forms (Allen, 2011). The way we communicate about race in our regular interactions has also changed, and many people are still hesitant to discuss race for fear of using “the wrong” vocabulary.

[table id=3 /]

The five primary racial groups noted previously can still be broken down further to specify a particular region, country, or nation. For example, Asian Americans are diverse in terms of country and language of origin and cultural practices. While the category of Asian Americans can be useful when discussing broad trends, it can also generalize among groups, which can lead to stereotypes. You may find that someone identifies as Chinese American or Korean American instead of Asian American. In this case, the label further highlights a person’s cultural lineage. We should not assume, however, that someone identifies with his or her cultural lineage, as many people have more in common with their US American peers than a culture that may be one or more generations removed.

History and personal preference also influence how we communicate about race. Culture and communication scholar Brenda Allen notes that when she was born in 1950, her birth certificate included an N for Negro. Later she referred to herself as colored because that is what people in her community referred to themselves as. During and before this time, the term black had negative connotations and would likely have offended someone. There was a movement in the 1960s to reclaim the word black, and the slogan “black is beautiful” was commonly used. Brenda Allen acknowledges the newer label of African American but notes that she still prefers black . The terms colored and Negro are no longer considered appropriate because they were commonly used during a time when black people were blatantly discriminated against. Even though that history may seem far removed to some, it is not to others. Currently, the terms African American and black are frequently used, and both are considered acceptable. The phrase people of color is acceptable for most and is used to be inclusive of other racial minorities. If you are unsure what to use, you could always observe how a person refers to himself or herself, or you could ask for his or her preference. In any case, a competent communicator defers to and respects the preference of the individual.

The label Latin American generally refers to people who live in Central American countries. Although Spain colonized much of what is now South and Central America and parts of the Caribbean, the inhabitants of these areas are now much more diverse. Depending on the region or country, some people primarily trace their lineage to the indigenous people who lived in these areas before colonization, or to a Spanish and indigenous lineage, or to other combinations that may include European, African, and/or indigenous heritage. Latina and Latino are labels that are preferable to Hispanic for many who live in the United States and trace their lineage to South and/ or Central America and/or parts of the Caribbean. Scholars who study Latina/o identity often use the label Latina/o in their writing to acknowledge women who avow that identity label (Calafell, 2007).

In verbal communication, you might say “Latina” when referring to a particular female or “Latino” when referring to a particular male of Latin American heritage. When referring to the group as a whole, you could say “Latinas and Latinos” instead of just “Latinos,” which would be more gender inclusive. While the US Census uses Hispanic, it refers primarily to people of Spanish origin, which does not account for the diversity of background of many Latinos/as. The term Hispanic also highlights the colonizer’s influence over the indigenous, which erases a history that is important to many. Additionally, there are people who claim Spanish origins and identify culturally as Hispanic but racially as white. Labels such as Puerto Rican or Mexican American, which further specify region or country of origin, may also be used. Just as with other cultural groups, if you are unsure of how to refer to someone, you can always ask for and honor someone’s preference.

The history of immigration in the United States also ties to the way that race has been constructed. The metaphor of the melting pot has been used to describe the immigration history of the United States but does not capture the experiences of many immigrant groups (Allen, 2011). Generally, immigrant groups who were white, or light skinned, and spoke English were better able to assimilate, or melt into the melting pot. However, immigrant groups that we might think of as white today were not always considered so. Irish immigrants were discriminated against and even portrayed as black in cartoons that appeared in newspapers. In some Southern states, Italian immigrants were forced to go to black schools, and it was not until 1952 that Asian immigrants were allowed to become citizens of the United States. All this history is important, because it continues to influence communication among races today.

Interracial Communication

Race and communication are related in various ways. Racism influences our communication about race and is not an easy topic for most people to discuss. Today, people tend to view racism as overt acts such as calling someone a derogatory name or discriminating against someone in thought or action. However, there is a difference between racist acts, which we can attach to an individual, and institutional racism, which is not as easily identifiable. It is much easier for people to recognize and decry racist actions than it is to realize that racist patterns and practices go through societal institutions, which means that racism exists and does not have to be committed by any one person. As competent communicators and critical thinkers, we must challenge ourselves to be aware of how racism influences our communication at individual and societal levels.

We tend to make some of our assumptions about people’s race based on how they talk, and often these assumptions are based on stereotypes. Dominant groups tend to define what is correct or incorrect usage of a language, and since language is so closely tied to identity, labeling a group’s use of a language as incorrect or deviant challenges or negates part of their identity (Yancy, 2011). We know there is not only one way to speak English, but there have been movements to identify a standard.

This becomes problematic when we realize that “standard English” refers to a way of speaking English that is based on white, middle-class ideals that do not match up with the experiences of many. When we create a standard for English, we can label anything that deviates from that “nonstandard English.” Differences between standard English and what has been called “Black English” have gotten national attention through debates about whether or not instruction in classrooms should accommodate students who do not speak standard English. Education plays an important role in language acquisition, and class relates to access to education. In general, whether someone speaks standard English themselves or not, they tend to judge negatively people whose speech deviates from the standard.

Another national controversy has revolved around the inclusion of Spanish in common language use, such as Spanish as an option at ATMs, or other automated services, and Spanish language instruction in school for students who do not speak or are learning to speak English. As was noted earlier, the Latino/a population in the United States is growing fast, which has necessitated inclusion of Spanish in many areas of public life. This has also created a backlash, which some scholars argue is tied more to the race of the immigrants than the language they speak and a fear that white America could be engulfed by other languages and cultures (Speicher, 2002). This backlash has led to a revived movement to make English the official language of the United States.

The U.S. Constitution does not stipulate a national language, and Congress has not designated one either. While nearly thirty states have passed English-language legislation, it has mostly been symbolic, and court rulings have limited any enforceability (Zuckerman, 2010). The Linguistic Society of America points out that immigrants are very aware of the social and economic advantages of learning English and do not need to be forced. They also point out that the United States has always had many languages represented, that national unity has not rested on a single language, and that there are actually benefits to having a population that is multilingual (Linguistic Society of America, 2011). Interracial communication presents some additional verbal challenges.

Code switching involves changing from one way of speaking to another between or within interactions. Some people of color may engage in code switching when communicating with dominant group members because they fear they will be negatively judged. Adopting the language practices of the dominant group may minimize perceived differences. This code switching creates a linguistic dual consciousness in which people are able to maintain their linguistic identities with their in-group peers but can still acquire tools and gain access needed to function in dominant society (Yancy, 2011). White people may also feel anxious about communicating with people of color out of fear of being perceived as racist. In other situations, people in dominant groups may spotlight non-dominant members by asking them to comment on or educate others about their race (Allen, 2011).

When we first meet a newborn baby, we ask whether it is a boy or a girl. This question illustrates the importance of gender in organizing our social lives and our interpersonal relationships. A Canadian family became aware of the deep emotions people feel about gender and the great discomfort people feel when they cannot determine gender when they announced to the world that they were not going to tell anyone the gender of their baby, aside from the baby’s siblings. Their desire for their child, named Storm, to be able to experience early life without the boundaries and categories of gender brought criticism from many (Davis & James, 2011).

Conversely, many parents consciously or unconsciously “code” their newborns in gendered ways based on our society’s associations of pink clothing and accessories with girls and blue with boys. While it is obvious to most people that colors are not gendered, they take on new meaning when we assign gendered characteristics of masculinity and femininity to them. Just like race, gender is a socially constructed category. While it is true that there are biological differences between who we label male and female, the meaning our society places on those differences is what actually matters in our day-today lives. In addition, the biological differences are interpreted differently around the world, which further shows that although we think gender is a natural, normal, stable way of classifying things, it is actually not. There is a long history of appreciation for people who cross gender lines in Native American and South Central Asian cultures, to name just two.

You may have noticed the use the word gender instead of sex . That is because gender is an identity based on internalized cultural notions of masculinity and femininity that is constructed through communication and interaction. There are two important parts of this definition to unpack. First, we internalize notions of gender based on socializing institutions, which helps us form our gender identity. Then we attempt to construct that gendered identity through our interactions with others, which is our gender expression. Sex is based on biological characteristics, including external genitalia, internal sex organs, chromosomes, and hormones (Wood, 2005). While the biological characteristics between men and women are obviously different, the meaning that we create and attach to those characteristics makes them significant. The cultural differences in how that significance is ascribed are proof that “our way of doing things” is arbitrary. For example, cross-cultural research has found that boys and girls in most cultures show both aggressive and nurturing tendencies, but cultures vary in terms of how they encourage these characteristics between genders. In a group in Africa, young boys are responsible for taking care of babies and are encouraged to be nurturing (Wood, 2005).

Gender has been constructed over the past few centuries in political and deliberate ways that have tended to favor men in terms of power. Moreover, various academic fields joined in the quest to “prove” there are “natural” differences between men and women. While the “proof” they presented was credible to many at the time, it seems blatantly sexist and inaccurate today. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, scientists who measure skulls, also known as craniometrists, claimed that men were more intelligent than women were because they had larger brains. Leaders in the fast-growing fields of sociology and psychology argued that women were less evolved than men and had more in common with “children and savages” than an adult (white) males (Allen, 2011).

Doctors and other decision makers like politicians also used women’s menstrual cycles as evidence that they were irrational, or hysterical, and therefore could not be trusted to vote, pursue higher education, or be in a leadership position. These are just a few of the many instances of how knowledge was created by seemingly legitimate scientific disciplines that we can now clearly see served to empower men and disempower women. This system is based on the ideology of patriarchy , which is a system of social structures and practices that maintains the values, priorities, and interests of men as a group (Wood, 2005). One of the ways patriarchy is maintained is by its relative invisibility. While women have been the focus of much research on gender differences, males have been largely unexamined. Men have been treated as the “generic” human being to which others are compared. However, that ignores the fact that men have a gender, too. Masculinities studies have challenged that notion by examining how masculinities are performed.

There have been challenges to the construction of gender in recent decades. Since the 1960s, scholars and activists have challenged established notions of what it means to be a man or a woman. The women’s rights movement in the United States dates back to the 1800s, when the first women’s rights convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848 (Wood, 2005). Although most women’s rights movements have been led by white, middle-class women, there was overlap between those involved in the abolitionist movement to end slavery and the beginnings of the women’s rights movement. Although some of the leaders of the early women’s rights movement had class and education privilege, they were still taking a risk by organizing and protesting. Black women were even more at risk, and Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave, faced those risks often and gave a much noted extemporaneous speech at a women’s rights gathering in Akron, Ohio, in 1851, which came to be called “Ain’t I a Woman?” (Wood, 2005) Her speech highlighted the multiple layers of oppression faced by black women.

Transgender is an umbrella term for people whose sex identity and/or expression does not match the sex they were assigned by birth. Transgender people may or may not seek medical intervention like surgery or hormone treatments to help match their physiology with their gender identity. The term transgender includes other labels such as transsexual and intersex, among others. Terms like hermaphrodite and she-male are not considered appropriate. As with other groups, it is best to allow someone to self-identify first and then honor their preferred label. If you are unsure of which pronouns to use when addressing someone, you can use gender-neutral language or you can use the pronoun that matches with how they are presenting.

Gender as a cultural identity has implications for many aspects of our lives, including real-world contexts like education and work. Schools are primary grounds for socialization, and the educational experience for males and females is different in many ways from preschool through college. Although not always intentional, schools tend to recreate the hierarchies and inequalities that exist in society. Given that we live in a patriarchal society, there are communicative elements present in school that support this (Allen, 2011). For example, teachers are more likely to call on and pay attention to boys in a classroom, giving them more feedback in the form of criticism, praise, and help. This sends an implicit message that boys are more worthy of attention and valuable than girls are. Teachers are also more likely to lead girls to focus on feelings and appearance and boys to focus on competition and achievement. The focus on appearance for girls can lead to anxieties about body image.

Gender inequalities are also evident in the administrative structure of schools, which puts males in positions of authority more than females. While females make up 75 percent of the educational workforce, only 22 percent of superintendents and 8 percent of high school principals are women. Similar trends exist in colleges and universities, with women only accounting for 26 percent of full professors. These inequalities in schools correspond to larger inequalities in the general workforce. While there are more women in the workforce now than ever before, they still face a glass ceiling, which is a barrier for promotion to upper management. Many of my students have been surprised at the continuing pay gap that exists between men and women. In 2010, women earned about seventy-seven cents to every dollar earned by men (National Committee on Pay Equity, 2021). To put this into perspective, the National Committee on Pay Equity started an event called Equal Pay Day. In 2011, Equal Pay Day was on April 11. This signifies that for a woman to earn the same amount of money a man earned in a year, she would have to work more than three months extra, until April 11, to make up for the difference (National Committee on Pay Equity, 2021).

While race and gender are two of the first things we notice about others, sexuality is often something we view as personal and private. Although many people hold a view that a person’s sexuality should be kept private, this is not a reality for our society. One only needs to observe popular culture and media for a short time to see that sexuality permeates much of our public discourse.

Sexuality relates to culture and identity in important ways that extend beyond sexual orientation, just as race is more than the color of one’s skin and gender is more than one’s biological and physiological manifestations of masculinity and femininity. Sexuality is not just physical; it is social in that we communicate with others about sexuality (Allen, 2011). Sexuality is also biological in that it connects to physiological functions that carry significant social and political meaning like puberty, menstruation, and pregnancy. Sexuality connects to public health issues like sexually transmitted infections (STIs), sexual assault, sexual abuse, sexual harassment, and teen pregnancy. Sexuality is at the center of political issues like abortion, sex education, and gay and lesbian rights. While all these contribute to sexuality as a cultural identity, the focus in this section is on sexual orientation.

The most obvious way sexuality relates to identity is through sexual orientation. Sexual orientation refers to a person’s primary physical and emotional sexual attraction and activity. The terms we most often use to categorize sexual orientation are heterosexual, gay, lesbian, and bisexual. Gays, lesbians, and bisexuals are sometimes referred to as sexual minorities. While the term sexual preference has been used previously, sexual orientation is more appropriate, since preference implies a simple choice. Although someone’s preference for a restaurant or actor may change frequently, sexuality is not as simple. The term homosexual can be appropriate in some instances, but it carries with it a clinical and medicalized tone. As you will see in the timeline that follows, the medical community has a recent history of “treating homosexuality” with means that most would view as inhumane today. So many people prefer a term like gay, which was chosen and embraced by gay people, rather than homosexual, which was imposed by a then discriminatory medical system.

The gay and lesbian rights movement became widely recognizable in the United States in the 1950s and continues on today, as evidenced by prominent issues regarding sexual orientation in national news and politics. National and international groups like the Human Rights Campaign advocate for rights for gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer (GLBTQ) communities. While these communities are often grouped together within one acronym (GLBTQ), they are different. Gays and lesbians constitute the most visible of the groups and receive the most attention and funding. Bisexuals are rarely visible or included in popular cultural discourses or in social and political movements. Transgender issues have received much more attention in recent years, but transgender identity connects to gender more than it does to sexuality. Last, queer is a term used to describe a group that is diverse in terms of identities but usually takes a more activist and at times radical stance that critiques sexual categories. While queer was long considered a derogatory label, and still is by some, the queer activist movement that emerged in the 1980s and early 1990s reclaimed the word and embraced it as a positive. As you can see, there is a diversity of identities among sexual minorities, just as there is variation within races and genders.

As with other cultural identities, notions of sexuality have been socially constructed in different ways throughout human history. Sexual orientation did not come into being as an identity category until the late 1800s. Before that, sexuality was viewed in more physical or spiritual senses that were largely separate from a person’s identity. The table below traces some of the developments relevant to sexuality, identity, and communication that show how this cultural identity has been constructed over the past 3,000 years.

[table id=4 /]

There is resistance to classifying ability as a cultural identity, because we follow a medical model of disability that places disability as an individual and medical rather than social and cultural issue. While much of what distinguishes able-bodied and cognitively able from disabled is rooted in science, biology, and physiology, there are important sociocultural dimensions. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) defines an individual with a disability as “a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, a person who has a history or record of such an impairment, or a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment” (Allen, 2011). An impairment is defined as “any temporary or permanent loss or abnormality of a body structure or function, whether physiological or psychological” (Allen, 2011).

This definition is important because it notes the social aspect of disability in that people’s life activities are limited and the relational aspect of disability in that the perception of a disability by others can lead someone to be classified as such. Ascribing an identity of disabled to a person can be problematic. If there is a mental or physical impairment, it should be diagnosed by a credentialed expert. If there is not an impairment, then the label of disabled can have negative impacts, as this label carries social and cultural significance. People are tracked into various educational programs based on their physical and cognitive abilities. In addition, there are many cases of people being mistakenly labeled disabled who were treated differently despite their protest of the ascribed label. Students who did not speak English as a first language, for example, were—and perhaps still are—sometimes put into special education classes.

Ability, just as the other cultural identities discussed, has institutionalized privileges and disadvantages associated with it. Ableism is the system of beliefs and practices that produces a physical and mental standard that is projected as normal for a human being and labels deviations from it abnormal, resulting in unequal treatment and access to resources. Ability privilege refers to the unearned advantages that are provided for people who fit the cognitive and physical norms (Allen, 2011). I once attended a workshop about ability privilege led by a man who was visually impaired. He talked about how, unlike other cultural identities that are typically stable over a lifetime, ability fluctuates for most people. We have all experienced times when we are more or less able.

Perhaps you broke your leg and had to use crutches or a wheelchair for a while. Getting sick for a prolonged period of time also lessens our abilities, but we may fully recover from any of these examples and regain our ability privilege. Whether you have experienced a short-term disability or not, the majority of us will become less physically and cognitively able as we get older.

Statistically, people with disabilities make up the largest minority group in the United States, with an estimated 20 percent of people five years or older living with some form of disability (Allen, 2011). Medical advances have allowed some people with disabilities to live longer and more active lives than before, which has led to an increase in the number of people with disabilities. This number could continue to increase, as we have thousands of veterans returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan with physical disabilities or psychological impairments such as posttraumatic stress disorder.

As disability has been constructed in US history, it has intersected with other cultural identities. For example, people opposed to “political and social equality for women cited their supposed physical, intellectual, and psychological flaws, deficits, and deviations from the male norm.” They framed women as emotional, irrational, and unstable, which was used to put them into the “scientific” category of “feeblemindedness,” which led them to be institutionalized (Carlson, 2001). Arguments supporting racial inequality and tighter immigration restrictions also drew on notions of disability, framing certain racial groups as prone to mental retardation, mental illness, or uncontrollable emotions and actions. Refer to table 7.4 for a timeline of developments related to ability, identity, and communication. These thoughts led to a dark time in US history, as the eugenics movement sought to limit reproduction of people deemed as deficient.

[table id=5 /]

7.3 Intercultural Communication Competence

It is through intercultural communication that we come to create, understand, and transform culture and identity. Intercultural communication is communication between people with differing cultural identities. One reason we should study intercultural communication is to foster greater self-awareness (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). Our thought process regarding culture is often “other focused,” meaning that the culture of the other person or group is what stands out in our perception. However, the old adage “know thyself” is appropriate, as we become more aware of our own culture by better understanding other cultures and perspectives. Intercultural communication can allow us to step outside of our comfortable, usual frame of reference and see our culture through a different lens. Additionally, as we become more self-aware, we may also become more ethical communicators as we challenge our ethnocentrism , or our tendency to view our own culture as superior to other cultures.

Intercultural communication competence (ICC) is the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in various cultural contexts. There are numerous components of ICC. Some key components include motivation, self- and other knowledge, and tolerance for uncertainty.

Initially, a person’s motivation for communicating with people from other cultures must be considered. Motivation refers to the root of a person’s desire to foster intercultural relationships and can be intrinsic or extrinsic (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). Put simply, if a person is not motivated to communicate with people from different cultures, then the components of ICC discussed next do not really matter. If a person has a healthy curiosity that drives him or her toward intercultural encounters in order to learn more about self and others, then there is a foundation from which to build additional competence-relevant attitudes and skills. This intrinsic motivation makes intercultural communication a voluntary, rewarding, and lifelong learning process. Motivation can also be extrinsic, meaning that the desire for intercultural communication is driven by an outside reward like money, power, or recognition. While both types of motivation can contribute to ICC, context may further enhance or impede a person’s motivation to communicate across cultures.

Members of dominant groups are often less motivated, intrinsically and extrinsically, toward intercultural communication than members of non-dominant groups, because they do not see the incentives for doing so. Having more power in communication encounters can create an unbalanced situation where the individual from the non-dominant group is expected to exhibit competence, or the ability to adapt to the communication behaviors and attitudes of the other. Even in situations where extrinsic rewards like securing an overseas business investment are at stake, it is likely that the foreign investor is much more accustomed to adapting to United States business customs and communication than vice versa. This expectation that others will adapt to our communication can be unconscious, but later ICC skills we will learn will help bring it to awareness.

The unbalanced situation I just described is a daily reality for many individuals with non-dominant identities. Their motivation toward intercultural communication may be driven by survival in terms of functioning effectively in dominant contexts. Recall the phenomenon known as code switching discussed earlier, in which individuals from non-dominant groups adapt their communication to fit in with the dominant group. In such instances, African Americans may “talk white” by conforming to what is called “standard English,” women in corporate environments may adapt masculine communication patterns, people who are gay or lesbian may self-censor and avoid discussing their same-gender partners with coworkers, and people with nonvisible disabilities may not disclose them in order to avoid judgment.

While intrinsic motivation captures an idealistic view of intercultural communication as rewarding in its own right, many contexts create extrinsic motivation. In either case, there is a risk that an individual’s motivation can still lead to incompetent communication. For example, it would be exploitative for an extrinsically motivated person to pursue intercultural communication solely for an external reward and then abandon the intercultural relationship once the reward is attained. These situations highlight the relational aspect of ICC, meaning that the motivation of all parties should be considered. Motivation alone cannot create ICC.

Knowledge supplements motivation and is an important part of building ICC. Knowledge includes self- and other-awareness, mindfulness, and cognitive flexibility. Building knowledge of our own cultures, identities, and communication patterns takes more than passive experience (Martin & Nakayama). Developing cultural self-awareness often requires us to get out of our comfort zones. Listening to people who are different from us is a key component of developing self-knowledge. This may be uncomfortable, because we may realize that people think of our identities differently than we thought.

The most effective way to develop other-knowledge is by direct and thoughtful encounters with other cultures. However, people may not readily have these opportunities for a variety of reasons. Despite the overall diversity in the United States, many people still only interact with people who are similar to them. Even in a racially diverse educational setting, for example, people often group off with people of their own race. While a heterosexual person may have a gay or lesbian friend or relative, they likely spend most of their time with other heterosexuals. Unless you interact with people with disabilities as part of your job or have a person with a disability in your friend or family group, you likely spend most of your time interacting with able-bodied people. Living in a rural area may limit your ability to interact with a range of cultures, and most people do not travel internationally regularly. Because of this, we may have to make a determined effort to interact with other cultures or rely on educational sources like college classes, books, or documentaries. Learning another language is also a good way to learn about a culture, because you can then read the news or watch movies in the native language, which can offer insights that are lost in translation. It is important to note though that we must evaluate the credibility of the source of our knowledge, whether it is a book, person, or other source. In addition, knowledge of another language does not automatically equate to ICC.

Developing self- and other-knowledge is an ongoing process that will continue to adapt and grow as we encounter new experiences. Mindfulness and cognitive complexity will help as we continue to build our ICC (Pusch, 2009). Mindfulness is a state of self- and other-monitoring that informs later reflection on communication interactions. As mindful communicators, we should ask questions that focus on the interactive process like “How is our communication going? What are my reactions? What are their reactions?” Being able to adapt our communication in the moment based on our answers to these questions is a skill that comes with a high level of ICC. Reflecting on the communication encounter later to see what can be learned is also a way to build ICC. We should then be able to incorporate what we learned into our communication frameworks, which requires cognitive flexibility. Cognitive flexibility refers to the ability to continually supplement and revise existing knowledge to create new categories rather than forcing new knowledge into old categories. Cognitive flexibility helps prevent our knowledge from becoming stale and also prevents the formation of stereotypes and can help us avoid prejudging an encounter or jumping to conclusions. In summary, to be better intercultural communicators, we should know much about others and ourselves and be able to reflect on and adapt our knowledge as we gain new experiences.

Motivation and knowledge can inform us as we gain new experiences, but how we feel in the moment of intercultural encounters is also important. Tolerance for uncertainty refers to an individual’s attitude about and level of comfort in uncertain situations (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). Some people perform better in uncertain situations than others, and intercultural encounters often bring up uncertainty. Whether communicating with someone of a different gender, race, or nationality, we are often wondering what we should or should not do or say. Situations of uncertainty most often become clearer as they progress, but the anxiety that an individual with a low tolerance for uncertainty feels may lead them to leave the situation or otherwise communicate in a less competent manner. Individuals with a high tolerance for uncertainty may exhibit more patience, waiting on new information to become available or seeking out information, which may then increase the understanding of the situation and lead to a more successful outcome (Pusch, 2009). Individuals who are intrinsically motivated toward intercultural communication may have a higher tolerance for uncertainty, in that their curiosity leads them to engage with others who are different because they find the self- and other-knowledge gained rewarding.

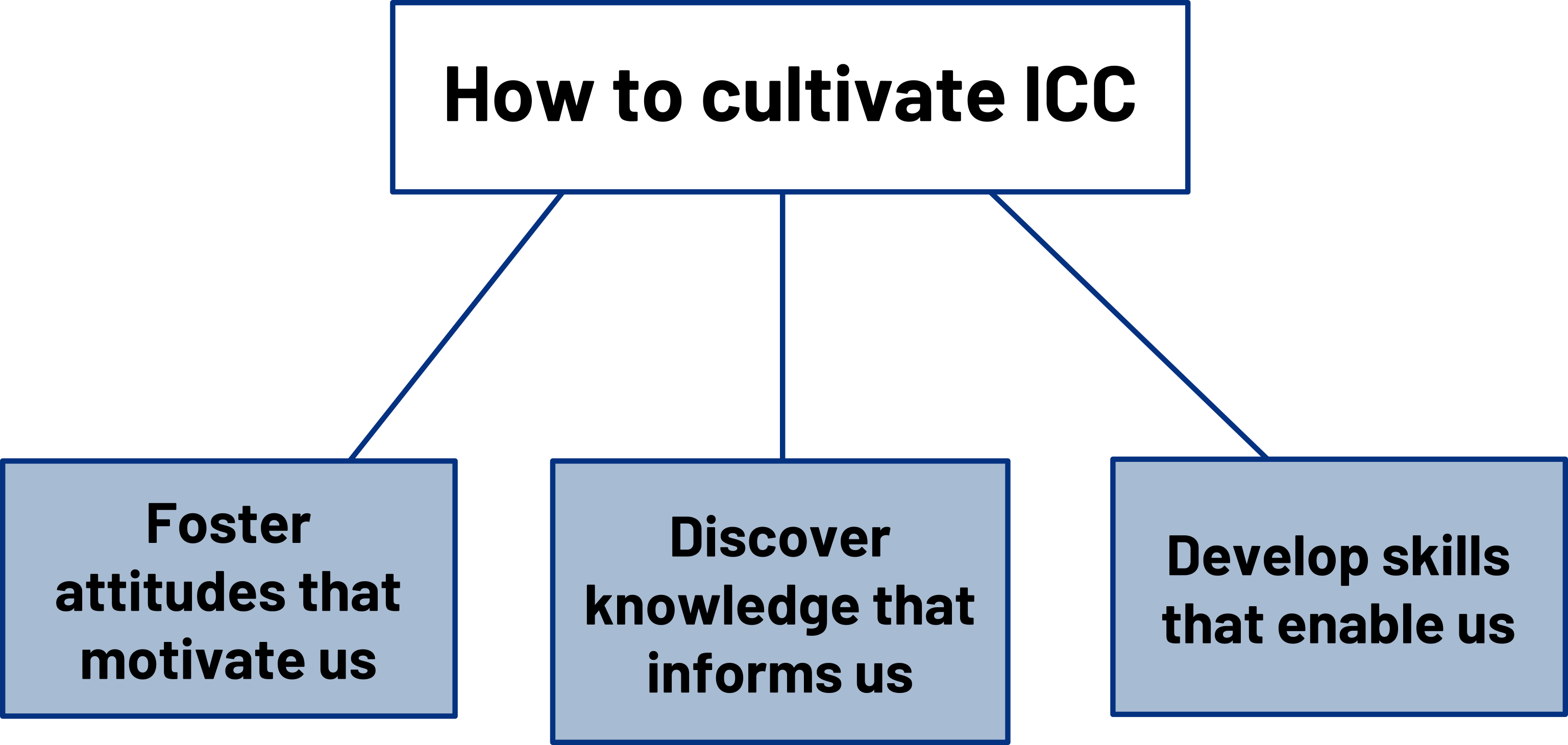

Cultivating Intercultural Communication Competence

How can ICC be built and achieved? This is a key question we will address in this section. Two main ways to build ICC are through experiential learning and reflective practices (Bednarz, 2010). We must first realize that competence is not any one thing. Part of being competent means that you can assess new situations and adapt your existing knowledge to the new contexts. What it means to be competent will vary depending on your physical location, your role (personal, professional, etc.), and your life stage, among other things. Sometimes we will know or be able to figure out what is expected of us in a given situation, but sometimes we may need to act in unexpected ways to meet the needs of a situation. Competence enables us to better cope with the unexpected, adapt to the non-routine, and connect to uncommon frameworks. ICC is less about a list of rules and more about a box of tools.

Three ways to cultivate ICC are to foster attitudes that motivate us, discover knowledge that informs us, and develop skills that enable us (Bennett, 2009). To foster attitudes that motivate us, we must develop a sense of wonder about culture. This sense of wonder can lead to feeling overwhelmed, humbled, or awed (Opdal, 2001). This sense of wonder may correlate to a high tolerance for uncertainty, which can help us turn potentially frustrating experiences we have into teachable moments. You may have had such moments in your own experience abroad. For example, trying to cook a pizza when you do not have instructions in your native language. The information on the packaging was written in Swedish, but like many college students, you have a wealth of experience cooking frozen pizzas to draw from. You might think it strange that the oven did not go up to the usual 425–450 degrees. Not to be deterred, and if you cranked the dial up as far as it would go, waited a few minutes, put in your pizza, and walked down the hall to room to wait for about fifteen minutes until the pizza was done. You would soon figure out that the oven temperatures in Sweden are listed in Celsius, not Fahrenheit!

Discovering knowledge that informs us is another step that can build on our motivation. One tool involves learning more about our cognitive style (how we learn). Our cognitive style consists of our preferred patterns for “gathering information, constructing meaning, and organizing and applying knowledge” (Bennett, 2009). As we explore cognitive styles, we discover that there are differences in how people attend to and perceive the world, explain events, organize the world, and use rules of logic (Nisbett, 2003). Some cultures have a cognitive style that focuses more on tasks, analytic and objective thinking, details and precision, inner direction, and independence, while others focus on relationships and people over tasks and things, concrete and metaphorical thinking, and a group consciousness and harmony.

Developing ICC is a complex learning process. At the basic level of learning, we accumulate knowledge and assimilate it into our existing frameworks. However, accumulated knowledge does not necessarily help us in situations where we have to apply that knowledge. Transformative learning takes place at the highest levels and occurs when we encounter situations that challenge our accumulated knowledge and our ability to accommodate that knowledge to manage a real-world situation. The cognitive dissonance that results in these situations is often uncomfortable and can lead to a hesitance to repeat such an engagement. One tip for cultivating ICC that can help manage these challenges is to find a community of like-minded people who are also motivated to develop ICC.

Developing skills that enable us is another part of ICC. Some of the skills important to ICC are the ability to empathize, accumulate cultural information, listen, resolve conflict, and manage anxiety (Bennett, 2009). Again, you are already developing a foundation for these skills by reading this book, but you can expand those skills to intercultural settings with the motivation and knowledge already described. Contact alone does not increase intercultural skills; there must be more deliberate measures taken to capitalize fully on those encounters. While research now shows that intercultural contact does decrease prejudices, this is not enough to become interculturally competent. The ability to empathize and manage anxiety enhances prejudice reduction, and these two skills have been shown to enhance the overall impact of intercultural contact even more than acquiring cultural knowledge. There is intercultural training available for people who are interested. If you cannot access training, you may choose to research intercultural training on your own, as there are many books, articles, and manuals written on the subject.

While formal intercultural experiences like studying abroad or volunteering for the Special Olympics or a shelter for gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer (GLBTQ) youth can result in learning, informal experiences are also important. We may be less likely to include informal experiences in our reflection if we do not see them as legitimate. Reflection should also include “critical incidents” or what I call “a-ha! moments.” Think of reflection as a tool for metacompetence that can be useful in bringing the formal and informal together (Bednarz, 2010).

Figure 7.1: The Hispanic and Latinx population has grown 43% since 2000. Jhon David. 2018. Unsplash license . https://unsplash.com/photos/3WgkTDw7XyE

Figure 7.2: Competent communicators challenge themselves through awareness. Kindred Grey. 2022. CC BY 4.0 . Includes Think by Brandon Lim from NounProject ( NounProject license ).

Figure 7.3: Ability is a social identity that makes up the largest minority group in the U.S.. CDC. 2021. Unsplash license . https://unsplash.com/photos/68zwHPkpxpI