On The Site

Harvard educational review.

Edited by Maya Alkateb-Chami, Jane Choi, Jeannette Garcia Coppersmith, Ron Grady, Phoebe A. Grant-Robinson, Pennie M. Gregory, Jennifer Ha, Woohee Kim, Catherine E. Pitcher, Elizabeth Salinas, Caroline Tucker, Kemeyawi Q. Wahpepah

Individuals

Institutions.

- Read the journal here

Journal Information

- ISSN: 0017-8055

- eISSN: 1943-5045

- Keywords: scholarly journal, education research

- First Issue: 1930

- Frequency: Quarterly

Description

The Harvard Educational Review (HER) is a scholarly journal of opinion and research in education. The Editorial Board aims to publish pieces from interdisciplinary and wide-ranging fields that advance our understanding of educational theory, equity, and practice. HER encourages submissions from established and emerging scholars, as well as from practitioners working in the field of education. Since its founding in 1930, HER has been central to elevating pieces and debates that tackle various dimensions of educational justice, with circulation to researchers, policymakers, teachers, and administrators.

Our Editorial Board is composed entirely of doctoral students from the Harvard Graduate School of Education who review all manuscripts considered for publication. For more information on the current Editorial Board, please see here.

A subscription to the Review includes access to the full-text electronic archives at our Subscribers-Only-Website .

Editorial Board

2023-2024 Harvard Educational Review Editorial Board Members

Maya Alkateb-Chami Development and Partnerships Editor, 2023-2024 Editor, 2022-2024 [email protected]

Maya Alkateb-Chami is a PhD student at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her research focuses on the role of schooling in fostering just futures—specifically in relation to language of instruction policies in multilingual contexts and with a focus on epistemic injustice. Prior to starting doctoral studies, she was the Managing Director of Columbia University’s Human Rights Institute, where she supported and co-led a team of lawyers working to advance human rights through research, education, and advocacy. Prior to that, she was the Executive Director of Jusoor, a nonprofit organization that helps conflict-affected Syrian youth and children pursue their education in four countries. Alkateb-Chami is a Fulbright Scholar and UNESCO cultural heritage expert. She holds an MEd in Language and Literacy from Harvard University; an MSc in Education from Indiana University, Bloomington; and a BA in Political Science from Damascus University, and her research on arts-based youth empowerment won the annual Master’s Thesis Award of the U.S. Society for Education Through Art.

Jane Choi Editor, 2023-2025

Jane Choi is a second-year PhD student in Sociology with broad interests in culture, education, and inequality. Her research examines intra-racial and interracial boundaries in US educational contexts. She has researched legacy and first-generation students at Ivy League colleges, families served by Head Start and Early Head Start programs, and parents of pre-K and kindergarten-age children in the New York City School District. Previously, Jane worked as a Research Assistant in the Family Well-Being and Children’s Development policy area at MDRC and received a BA in Sociology from Columbia University.

Jeannette Garcia Coppersmith Content Editor, 2023-2024 Editor, 2022-2024 [email protected]

Jeannette Garcia Coppersmith is a fourth-year Education PhD student in the Human Development, Learning and Teaching concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. A former public middle and high school mathematics teacher and department chair, she is interested in understanding the mechanisms that contribute to disparities in secondary mathematics education, particularly how teacher beliefs and biases intersect with the social-psychological processes and pedagogical choices involved in math teaching. Jeannette holds an EdM in Learning and Teaching from the Harvard Graduate School of Education where she studied as an Urban Scholar and a BA in Environmental Sciences from the University of California, Berkeley.

Ron Grady Editor, 2023-2025

Ron Grady is a second-year doctoral student in the Human Development, Learning, and Teaching concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. His central curiosities involve the social worlds and peer cultures of young children, wondering how lived experience is both constructed within and revealed throughout play, the creation of art and narrative, and through interaction with/production of visual artifacts such as photography and film. Ron also works extensively with educators interested in developing and deepening practices rooted in reflection on, inquiry into, and translation of the social, emotional, and aesthetic aspects of their classroom ecosystems. Prior to his doctoral studies, Ron worked as a preschool teacher in New Orleans. He holds a MS in Early Childhood Education from the Erikson Institute and a BA in Psychology with Honors in Education from Stanford University.

Phoebe A. Grant-Robinson Editor, 2023-2024

Phoebe A. Grant-Robinson is a first year student in the Doctor of Education Leadership(EdLD) program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her ultimate quest is to position all students as drivers of their destiny. Phoebe is passionate about early learning and literacy. She is committed to ensuring that districts and school leaders, have the necessary tools to create equitable learning organizations that facilitate the academic and social well-being of all students. Phoebe is particularly interested in the intersection of homeless students and literacy. Prior to her doctoral studies, Phoebe was a Special Education Instructional Specialist. Supporting a portfolio of more than thirty schools, she facilitated the rollout of New York City’s Special Education Reform. Phoebe also served as an elementary school principal. She holds a BS in Inclusive Education from Syracuse University, and an MS in Curriculum and Instruction from Pace University.

Pennie M. Gregory Editor, 2023-2024

Pennie M. Gregory is a second-year student in the Doctor of Education Leadership (EdLD) program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Pennie was born in Incheon, South Korea and raised in Gary, Indiana. She has decades of experience leading efforts to improve outcomes for students with disabilities first as a special education teacher and then as a school district special education administrator. Prior to her doctoral studies, Pennie helped to create Indiana’s first Aspiring Special Education Leadership Institute (ASELI) and served as its Director. She was also the Capacity Events Director for MelanatED Leaders, an organization created to support educational leaders of color in Indianapolis. Pennie has a unique perspective, having worked with members of the school community, with advocacy organizations, and supporting state special education leaders. Pennie holds an EdM in Education Leadership from Marian University.

Jennifer Ha Editor, 2023-2025

Jen Ha is a second-year PhD student in the Culture, Institutions, and Society concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her research explores how high school students learn to write personal narratives for school applications, scholarships, and professional opportunities amidst changing landscapes in college access and admissions. Prior to doctoral studies, Jen served as the Coordinator of Public Humanities at Bard Graduate Center and worked in several roles organizing academic enrichment opportunities and supporting postsecondary planning for students in New Haven and New York City. Jen holds a BA in Humanities from Yale University, where she was an Education Studies Scholar.

Woohee Kim Editor, 2023-2025

Woohee Kim is a PhD student studying youth activists’ civic and pedagogical practices. She is a scholar-activist dedicated to creating spaces for pedagogies of resistance and transformative possibilities. Shaped by her activism and research across South Korea, the US, and the UK, Woohee seeks to interrogate how educational spaces are shaped as cultural and political sites and reshaped by activists as sites of struggle. She hopes to continue exploring the intersections of education, knowledge, power, and resistance.

Catherine E. Pitcher Editor, 2023-2025

Catherine is a second-year doctoral student at Harvard Graduate School of Education in the Culture, Institutions, and Society program. She has over 10 years of experience in education in the US in roles that range from special education teacher to instructional coach to department head to educational game designer. She started working in Palestine in 2017, first teaching, and then designing and implementing educational programming. Currently, she is working on research to understand how Palestinian youth think about and build their futures and continues to lead programming in the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem. She holds an EdM from Harvard in International Education Policy.

Elizabeth Salinas Editor, 2023-2025

Elizabeth Salinas is a doctoral student in the Education Policy and Program Evaluation concentration at HGSE. She is interested in the intersection of higher education and the social safety net and hopes to examine policies that address basic needs insecurity among college students. Before her doctoral studies, Liz was a research director at a public policy consulting firm. There, she supported government, education, and philanthropy leaders by conducting and translating research into clear and actionable information. Previously, Liz served as a high school physics teacher in her hometown in Texas and as a STEM outreach program director at her alma mater. She currently sits on the Board of Directors at Leadership Enterprise for a Diverse America, a nonprofit organization working to diversify the leadership pipeline in the United States. Liz holds a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a master’s degree in higher education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Caroline Tucker Co-Chair, 2023-2024 Editor, 2022-2024 [email protected]

Caroline Tucker is a fourth-year doctoral student in the Culture, Institutions, and Society concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her research focuses on the history and organizational dynamics of women’s colleges as women gained entry into the professions and coeducation took root in the United States. She is also a research assistant for the Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery Initiative’s Subcommittee on Curriculum and the editorial assistant for Into Practice, the pedagogy newsletter distributed by Harvard University’s Office of the Vice Provost for Advances in Learning. Prior to her doctoral studies, Caroline served as an American politics and English teaching fellow in London and worked in college advising. Caroline holds a BA in History from Princeton University, an MA in the Social Sciences from the University of Chicago, and an EdM in Higher Education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Kemeyawi Q. Wahpepah Co-Chair, 2023-2024 Editor, 2022-2024 [email protected]

Kemeyawi Q. Wahpepah (Kickapoo, Sac & Fox) is a fourth-year doctoral student in the Culture, Institutions, and Society concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Their research explores how settler colonialism is addressed in K-12 history and social studies classrooms in the United States. Prior to their doctoral studies, Kemeyawi taught middle and high school English and history for eleven years in Boston and New York City. They hold an MS in Middle Childhood Education from Hunter College and an AB in Social Studies from Harvard University.

Submission Information

Click here to view submission guidelines .

Contact Information

Click here to view contact information for the editorial board and customer service .

Subscriber Support

Individual subscriptions must have an individual name in the given address for shipment. Individual copies are not for multiple readers or libraries. Individual accounts come with a personal username and password for access to online archives. Online access instructions will be attached to your order confirmation e-mail.

Institutional rates apply to libraries and organizations with multiple readers. Institutions receive digital access to content on Meridian from IP addresses via theIPregistry.org (by sending HER your PSI Org ID).

Online access instructions will be attached to your order confirmation e-mail. If you have questions about using theIPregistry.org you may find the answers in their FAQs. Otherwise please let us know at [email protected] .

How to Subscribe

To order online via credit card, please use the subscribe button at the top of this page.

To order by phone, please call 888-437-1437.

Checks can be mailed to Harvard Educational Review C/O Fulco, 30 Broad Street, Suite 6, Denville, NJ 07834. (Please include reference to your subscriber number if you are renewing. Institutions must include their PSI Org ID or follow up with this information via email to [email protected] .)

Permissions

Click here to view permissions information.

Article Submission FAQ

Submissions, question: “what manuscripts are a good fit for her ”.

Answer: As a generalist scholarly journal, HER publishes on a wide range of topics within the field of education and related disciplines. We receive many articles that deserve publication, but due to the restrictions of print publication, we are only able to publish very few in the journal. The originality and import of the findings, as well as the accessibility of a piece to HER’s interdisciplinary, international audience which includes education practitioners, are key criteria in determining if an article will be selected for publication.

We strongly recommend that prospective authors review the current and past issues of HER to see the types of articles we have published recently. If you are unsure whether your manuscript is a good fit, please reach out to the Content Editor at [email protected] .

Question: “What makes HER a developmental journal?”

Answer: Supporting the development of high-quality education research is a key tenet of HER’s mission. HER promotes this development through offering comprehensive feedback to authors. All manuscripts that pass the first stage of our review process (see below) receive detailed feedback. For accepted manuscripts, HER also has a unique feedback process called casting whereby two editors carefully read a manuscript and offer overarching suggestions to strengthen and clarify the argument.

Question: “What is a Voices piece and how does it differ from an essay?”

Answer: Voices pieces are first-person reflections about an education-related topic rather than empirical or theoretical essays. Our strongest pieces have often come from educators and policy makers who draw on their personal experiences in the education field. Although they may not present data or generate theory, Voices pieces should still advance a cogent argument, drawing on appropriate literature to support any claims asserted. For examples of Voices pieces, please see Alvarez et al. (2021) and Snow (2021).

Question: “Does HER accept Book Note or book review submissions?”

Answer: No, all Book Notes are written internally by members of the Editorial Board.

Question: “If I want to submit a book for review consideration, who do I contact?”

Answer: Please send details about your book to the Content Editor at [email protected].

Manuscript Formatting

Question: “the submission guidelines state that manuscripts should be a maximum of 9,000 words – including abstract, appendices, and references. is this applicable only for research articles, or should the word count limit be followed for other manuscripts, such as essays”.

Answer: The 9,000-word limit is the same for all categories of manuscripts.

Question: “We are trying to figure out the best way to mask our names in the references. Is it OK if we do not cite any of our references in the reference list? Our names have been removed in the in-text citations. We just cite Author (date).”

Answer: Any references that identify the author/s in the text must be masked or made anonymous (e.g., instead of citing “Field & Bloom, 2007,” cite “Author/s, 2007”). For the reference list, place the citations alphabetically as “Author/s. (2007)” You can also indicate that details are omitted for blind review. Articles can also be blinded effectively by use of the third person in the manuscript. For example, rather than “in an earlier article, we showed that” substitute something like “as has been shown in Field & Bloom, 2007.” In this case, there is no need to mask the reference in the list. Please do not submit a title page as part of your manuscript. We will capture the contact information and any author statement about the fit and scope of the work in the submission form. Finally, please save the uploaded manuscript as the title of the manuscript and do not include the author/s name/s.

Invitations

Question: “can i be invited to submit a manuscript how”.

Answer: If you think your manuscript is a strong fit for HER, we welcome a request for invitation. Invited manuscripts receive one round of feedback from Editors before the piece enters the formal review process. To submit information about your manuscript, please complete the Invitation Request Form . Please provide as many details as possible. The decision to invite a manuscript largely depends on the capacity of current Board members and on how closely the proposed manuscript reflects HER publication scope and criteria. Once you submit the form, We hope to update you in about 2–3 weeks, and will let you know whether there are Editors who are available to invite the manuscript.

Review Timeline

Question: “who reviews manuscripts”.

Answer: All manuscripts are reviewed by the Editorial Board composed of doctoral students at Harvard University.

Question: “What is the HER evaluation process as a student-run journal?”

Answer: HER does not utilize the traditional external peer review process and instead has an internal, two-stage review procedure.

Upon submission, every manuscript receives a preliminary assessment by the Content Editor to confirm that the formatting requirements have been carefully followed in preparation of the manuscript, and that the manuscript is in accord with the scope and aim of the journal. The manuscript then formally enters the review process.

In the first stage of review, all manuscripts are read by a minimum of two Editorial Board members. During the second stage of review, manuscripts are read by the full Editorial Board at a weekly meeting.

Question: “How long after submission can I expect a decision on my manuscript?”

Answer: It usually takes 6 to 10 weeks for a manuscript to complete the first stage of review and an additional 12 weeks for a manuscript to complete the second stage. Due to time constraints and the large volume of manuscripts received, HER only provides detailed comments on manuscripts that complete the second stage of review.

Question: “How soon are accepted pieces published?”

Answer: The date of publication depends entirely on how many manuscripts are already in the queue for an issue. Typically, however, it takes about 6 months post-acceptance for a piece to be published.

Submission Process

Question: “how do i submit a manuscript for publication in her”.

Answer: Manuscripts are submitted through HER’s Submittable platform, accessible here. All first-time submitters must create an account to access the platform. You can find details on our submission guidelines on our Submissions page.

Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application

- Open Access

- First Online: 22 November 2019

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Mark Newman 6 &

- David Gough 6

88k Accesses

152 Citations

2 Altmetric

This chapter explores the processes of reviewing literature as a research method. The logic of the family of research approaches called systematic review is analysed and the variation in techniques used in the different approaches explored using examples from existing reviews. The key distinctions between aggregative and configurative approaches are illustrated and the chapter signposts further reading on key issues in the systematic review process.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Reviewing Literature for and as Research

Methodological Approaches to Literature Review

The Role of Meta-analysis in Educational Research

1 what are systematic reviews.

A literature review is a scholarly paper which provides an overview of current knowledge about a topic. It will typically include substantive findings, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to a particular topic (Hart 2018 , p. xiii). Traditionally in education ‘reviewing the literature’ and ‘doing research’ have been viewed as distinct activities. Consider the standard format of research proposals, which usually have some kind of ‘review’ of existing knowledge presented distinctly from the methods of the proposed new primary research. However, both reviews and research are undertaken in order to find things out. Reviews to find out what is already known from pre-existing research about a phenomena, subject or topic; new primary research to provide answers to questions about which existing research does not provide clear and/or complete answers.

When we use the term research in an academic sense it is widely accepted that we mean a process of asking questions and generating knowledge to answer these questions using rigorous accountable methods. As we have noted, reviews also share the same purposes of generating knowledge but historically we have not paid as much attention to the methods used for reviewing existing literature as we have to the methods used for primary research. Literature reviews can be used for making claims about what we know and do not know about a phenomenon and also about what new research we need to undertake to address questions that are unanswered. Therefore, it seems reasonable to conclude that ‘how’ we conduct a review of research is important.

The increased focus on the use of research evidence to inform policy and practice decision-making in Evidence Informed Education (Hargreaves 1996 ; Nelson and Campbell 2017 ) has increased the attention given to contextual and methodological limitations of research evidence provided by single studies. Reviews of research may help address these concerns when carried on in a systematic, rigorous and transparent manner. Thus, again emphasizing the importance of ‘how’ reviews are completed.

The logic of systematic reviews is that reviews are a form of research and thus can be improved by using appropriate and explicit methods. As the methods of systematic review have been applied to different types of research questions, there has been an increasing plurality of types of systematic review. Thus, the term ‘systematic review’ is used in this chapter to refer to a family of research approaches that are a form of secondary level analysis (secondary research) that brings together the findings of primary research to answer a research question. Systematic reviews can therefore be defined as “a review of existing research using explicit, accountable rigorous research methods” (Gough et al. 2017 , p. 4).

2 Variation in Review Methods

Reviews can address a diverse range of research questions. Consequently, as with primary research, there are many different approaches and methods that can be applied. The choices should be dictated by the review questions. These are shaped by reviewers’ assumptions about the meaning of a particular research question, the approach and methods that are best used to investigate it. Attempts to classify review approaches and methods risk making hard distinctions between methods and thereby to distract from the common defining logics that these approaches often share. A useful broad distinction is between reviews that follow a broadly configurative synthesis logic and reviews that follow a broadly aggregative synthesis logic (Sandelowski et al. 2012 ). However, it is important to keep in mind that most reviews have elements of both (Gough et al. 2012 ).

Reviews that follow a broadly configurative synthesis logic approach usually investigate research questions about meaning and interpretation to explore and develop theory. They tend to use exploratory and iterative review methods that emerge throughout the process of the review. Studies included in the review are likely to have investigated the phenomena of interest using methods such as interviews and observations, with data in the form of text. Reviewers are usually interested in purposive variety in the identification and selection of studies. Study quality is typically considered in terms of authenticity. Synthesis consists of the deliberative configuring of data by reviewers into patterns to create a richer conceptual understanding of a phenomenon. For example, meta ethnography (Noblit and Hare 1988 ) uses ethnographic data analysis methods to explore and integrate the findings of previous ethnographies in order to create higher-level conceptual explanations of phenomena. There are many other review approaches that follow a broadly configurative logic (for an overview see Barnett-Page and Thomas 2009 ); reflecting the variety of methods used in primary research in this tradition.

Reviews that follow a broadly aggregative synthesis logic usually investigate research questions about impacts and effects. For example, systematic reviews that seek to measure the impact of an educational intervention test the hypothesis that an intervention has the impact that has been predicted. Reviews following an aggregative synthesis logic do not tend to develop theory directly; though they can contribute by testing, exploring and refining theory. Reviews following an aggregative synthesis logic tend to specify their methods in advance (a priori) and then apply them without any deviation from a protocol. Reviewers are usually concerned to identify the comprehensive set of studies that address the research question. Studies included in the review will usually seek to determine whether there is a quantitative difference in outcome between groups receiving and not receiving an intervention. Study quality assessment in reviews following an aggregative synthesis logic focusses on the minimisation of bias and thus selection pays particular attention to homogeneity between studies. Synthesis aggregates, i.e. counts and adds together, the outcomes from individual studies using, for example, statistical meta-analysis to provide a pooled summary of effect.

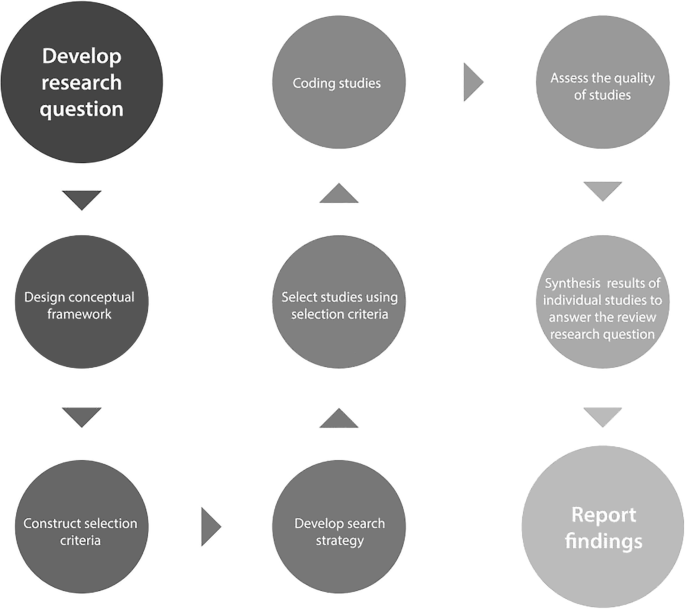

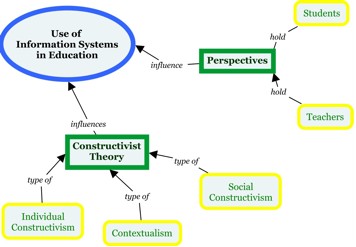

3 The Systematic Review Process

Different types of systematic review are discussed in more detail later in this chapter. The majority of systematic review types share a common set of processes. These processes can be divided into distinct but interconnected stages as illustrated in Fig. 1 . Systematic reviews need to specify a research question and the methods that will be used to investigate the question. This is often written as a ‘protocol’ prior to undertaking the review. Writing a protocol or plan of the methods at the beginning of a review can be a very useful activity. It helps the review team to gain a shared understanding of the scope of the review and the methods that they will use to answer the review’s questions. Different types of systematic reviews will have more or less developed protocols. For example, for systematic reviews investigating research questions about the impact of educational interventions it is argued that a detailed protocol should be fully specified prior to the commencement of the review to reduce the possibility of reviewer bias (Torgerson 2003 , p. 26). For other types of systematic review, in which the research question is more exploratory, the protocol may be more flexible and/or developmental in nature.

The systematic review process

3.1 Systematic Review Questions and the Conceptual Framework

The review question gives each review its particular structure and drives key decisions about what types of studies to include; where to look for them; how to assess their quality; and how to combine their findings. Although a research question may appear to be simple, it will include many assumptions. Whether implicit or explicit, these assumptions will include: epistemological frameworks about knowledge and how we obtain it, theoretical frameworks, whether tentative or firm, about the phenomenon that is the focus of study.

Taken together, these produce a conceptual framework that shapes the research questions, choices about appropriate systematic review approach and methods. The conceptual framework may be viewed as a working hypothesis that can be developed, refined or confirmed during the course of the research. Its purpose is to explain the key issues to be studied, the constructs or variables, and the presumed relationships between them. The framework is a research tool intended to assist a researcher to develop awareness and understanding of the phenomena under scrutiny and to communicate this (Smyth 2004 ).

A review to investigate the impact of an educational intervention will have a conceptual framework that includes a hypothesis about a causal link between; who the review is about (the people), what the review is about (an intervention and what it is being compared with), and the possible consequences of intervention on the educational outcomes of these people. Such a review would follow a broadly aggregative synthesis logic. This is the shape of reviews of educational interventions carried out for the What Works Clearing House in the USA Footnote 1 and the Education Endowment Foundation in England. Footnote 2

A review to investigate meaning or understanding of a phenomenon for the purpose of building or further developing theory will still have some prior assumptions. Thus, an initial conceptual framework will contain theoretical ideas about how the phenomena of interest can be understood and some ideas justifying why a particular population and/or context is of specific interest or relevance. Such a review is likely to follow a broadly configurative logic.

3.2 Selection Criteria

Reviewers have to make decisions about which research studies to include in their review. In order to do this systematically and transparently they develop rules about which studies can be selected into the review. Selection criteria (sometimes referred to as inclusion or exclusion criteria) create restrictions on the review. All reviews, whether systematic or not, limit in some way the studies that are considered by the review. Systematic reviews simply make these restrictions transparent and therefore consistent across studies. These selection criteria are shaped by the review question and conceptual framework. For example, a review question about the impact of homework on educational attainment would have selection criteria specifying who had to do the homework; the characteristics of the homework and the outcomes that needed to be measured. Other commonly used selection criteria include study participant characteristics; the country where the study has taken place and the language in which the study is reported. The type of research method(s) may also be used as a selection criterion but this can be controversial given the lack of consensus in education research (Newman 2008 ), and the inconsistent terminology used to describe education research methods.

3.3 Developing the Search Strategy

The search strategy is the plan for how relevant research studies will be identified. The review question and conceptual framework shape the selection criteria. The selection criteria specify the studies to be included in a review and thus are a key driver of the search strategy. A key consideration will be whether the search aims to be exhaustive i.e. aims to try and find all the primary research that has addressed the review question. Where reviews address questions about effectiveness or impact of educational interventions the issue of publication bias is a concern. Publication bias is the phenomena whereby smaller and/or studies with negative findings are less likely to be published and/or be harder to find. We may therefore inadvertently overestimate the positive effects of an educational intervention because we do not find studies with negative or smaller effects (Chow and Eckholm 2018 ). Where the review question is not of this type then a more specific or purposive search strategy, that may or may not evolve as the review progresses, may be appropriate. This is similar to sampling approaches in primary research. In primary research studies using aggregative approaches, such as quasi-experiments, analysis is based on the study of complete or representative samples. In primary research studies using configurative approaches, such as ethnography, analysis is based on examining a range of instances of the phenomena in similar or different contexts.

The search strategy will detail the sources to be searched and the way in which the sources will be searched. A list of search source types is given in Box 1 below. An exhaustive search strategy would usually include all of these sources using multiple bibliographic databases. Bibliographic databases usually index academic journals and thus are an important potential source. However, in most fields, including education, relevant research is published in a range of journals which may be indexed in different bibliographic databases and thus it may be important to search multiple bibliographic databases. Furthermore, some research is published in books and an increasing amount of research is not published in academic journals or at least may not be published there first. Thus, it is important to also consider how you will find relevant research in other sources including ‘unpublished’ or ‘grey’ literature. The Internet is a valuable resource for this purpose and should be included as a source in any search strategy.

Box 1: Search Sources

The World Wide Web/Internet

Google, Specialist Websites, Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic

Bibliographic Databases

Subject specific e.g. Education—ERIC: Education Resources Information Centre

Generic e.g. ASSIA: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts

Handsearching of specialist journals or books

Contacts with Experts

Citation Checking

New, federated search engines are being developed, which search multiple sources at the same time, eliminating duplicates automatically (Tsafnat et al. 2013 ). Technologies, including text mining, are being used to help develop search strategies, by suggesting topics and terms on which to search—terms that reviewers may not have thought of using. Searching is also being aided by technology through the increased use (and automation) of ‘citation chasing’, where papers that cite, or are cited by, a relevant study are checked in case they too are relevant.

A search strategy will identify the search terms that will be used to search the bibliographic databases. Bibliographic databases usually index records according to their topic using ‘keywords’ or ‘controlled terms’ (categories used by the database to classify papers). A comprehensive search strategy usually involves searching both a freetext search using keywords determined by the reviewers and controlled terms. An example of a bibliographic database search is given in Box 2. This search was used in a review that aimed to find studies that investigated the impact of Youth Work on positive youth outcomes (Dickson et al. 2013 ). The search is built using terms for the population of interest (Youth), the intervention of interest (Youth Work) and the outcomes of Interest (Positive Development). It used both keywords and controlled terms, ‘wildcards’ (the *sign in this database) and the Boolean operators ‘OR’ and ‘AND’ to combine terms. This example illustrates the potential complexity of bibliographic database search strings, which will usually require a process of iterative development to finalise.

Box 2: Search string example To identify studies that address the question What is the empirical research evidence on the impact of youth work on the lives of children and young people aged 10-24 years?: CSA ERIC Database

((TI = (adolescen* or (“young man*”) or (“young men”)) or TI = ((“young woman*”) or (“young women”) or (Young adult*”)) or TI = ((“young person*”) or (“young people*”) or teen*) or AB = (adolescen* or (“young man*”) or (“young men”)) or AB = ((“young woman*”) or (“young women”) or (Young adult*”)) or AB = ((“young person*”) or (“young people*”) or teen*)) or (DE = (“youth” or “adolescents” or “early adolescents” or “late adolescents” or “preadolescents”))) and(((TI = ((“positive youth development “) or (“youth development”) or (“youth program*”)) or TI = ((“youth club*”) or (“youth work”) or (“youth opportunit*”)) or TI = ((“extended school*”) or (“civic engagement”) or (“positive peer culture”)) or TI = ((“informal learning”) or multicomponent or (“multi-component “)) or TI = ((“multi component”) or multidimensional or (“multi-dimensional “)) or TI = ((“multi dimensional”) or empower* or asset*) or TI = (thriv* or (“positive development”) or resilienc*) or TI = ((“positive activity”) or (“positive activities”) or experiential) or TI = ((“community based”) or “community-based”)) or(AB = ((“positive youth development “) or (“youth development”) or (“youth program*”)) or AB = ((“youth club*”) or (“youth work”) or (“youth opportunit*”)) or AB = ((“extended school*”) or (“civic engagement”) or (“positive peer culture”)) or AB = ((“informal learning”) or multicomponent or (“multi-component “)) or AB = ((“multi component”) or multidimensional or (“multi-dimensional “)) or AB = ((“multi dimensional”) or empower* or asset*) or AB = (thriv* or (“positive development”) or resilienc*) or AB = ((“positive activity”) or (“positive activities”) or experiential) or AB = ((“community based”) or “community-based”))) or (DE=”community education”))

Detailed guidance for finding effectiveness studies is available from the Campbell Collaboration (Kugley et al. 2015 ). Guidance for finding a broader range of studies has been produced by the EPPI-Centre (Brunton et al. 2017a ).

3.4 The Study Selection Process

Studies identified by the search are subject to a process of checking (sometimes referred to as screening) to ensure they meet the selection criteria. This is usually done in two stages whereby titles and abstracts are checked first to determine whether the study is likely to be relevant and then a full copy of the paper is acquired to complete the screening exercise. The process of finding studies is not efficient. Searching bibliographic databases, for example, leads to many irrelevant studies being found which then have to be checked manually one by one to find the few relevant studies. There is increasing use of specialised software to support and in some cases, automate the selection process. Text mining, for example, can assist in selecting studies for a review (Brunton et al. 2017b ). A typical text mining or machine learning process might involve humans undertaking some screening, the results of which are used to train the computer software to learn the difference between included and excluded studies and thus be able to indicate which of the remaining studies are more likely to be relevant. Such automated support may result in some errors in selection, but this may be less than the human error in manual selection (O’Mara-Eves et al. 2015 ).

3.5 Coding Studies

Once relevant studies have been selected, reviewers need to systematically identify and record the information from the study that will be used to answer the review question. This information includes the characteristics of the studies, including details of the participants and contexts. The coding describes: (i) details of the studies to enable mapping of what research has been undertaken; (ii) how the research was undertaken to allow assessment of the quality and relevance of the studies in addressing the review question; (iii) the results of each study so that these can be synthesised to answer the review question.

The information is usually coded into a data collection system using some kind of technology that facilitates information storage and analysis (Brunton et al. 2017b ) such as the EPPI-Centre’s bespoke systematic review software EPPI Reviewer. Footnote 3 Decisions about which information to record will be made by the review team based on the review question and conceptual framework. For example, a systematic review about the relationship between school size and student outcomes collected data from the primary studies about each schools funding, students, teachers and school organisational structure as well as about the research methods used in the study (Newman et al. 2006 ). The information coded about the methods used in the research will vary depending on the type of research included and the approach that will be used to assess the quality and relevance of the studies (see the next section for further discussion of this point).

Similarly, the information recorded as ‘results’ of the individual studies will vary depending on the type of research that has been included and the approach to synthesis that will be used. Studies investigating the impact of educational interventions using statistical meta-analysis as a synthesis technique will require all of the data necessary to calculate effect sizes to be recorded from each study (see the section on synthesis below for further detail on this point). However, even in this type of study there will be multiple data that can be considered to be ‘results’ and so which data needs to be recorded from studies will need to be carefully specified so that recording is consistent across studies

3.6 Appraising the Quality of Studies

Methods are reinvented every time they are used to accommodate the real world of research practice (Sandelowski et al. 2012 ). The researcher undertaking a primary research study has attempted to design and execute a study that addresses the research question as rigorously as possible within the parameters of their resources, understanding, and context. Given the complexity of this task, the contested views about research methods and the inconsistency of research terminology, reviewers will need to make their own judgements about the quality of the any individual piece of research included in their review. From this perspective, it is evident that using a simple criteria, such as ‘published in a peer reviewed journal’ as a sole indicator of quality, is not likely to be an adequate basis for considering the quality and relevance of a study for a particular systematic review.

In the context of systematic reviews this assessment of quality is often referred to as Critical Appraisal (Petticrew and Roberts 2005 ). There is considerable variation in what is done during critical appraisal: which dimensions of study design and methods are considered; the particular issues that are considered under each dimension; the criteria used to make judgements about these issues and the cut off points used for these criteria (Oancea and Furlong 2007 ). There is also variation in whether the quality assessment judgement is used for excluding studies or weighting them in analysis and when in the process judgements are made.

There are broadly three elements that are considered in critical appraisal: the appropriateness of the study design in the context of the review question, the quality of the execution of the study methods and the study’s relevance to the review question (Gough 2007 ). Distinguishing study design from execution recognises that whilst a particular design may be viewed as more appropriate for a study it also needs to be well executed to achieve the rigour or trustworthiness attributed to the design. Study relevance is achieved by the review selection criteria but assessing the degree of relevance recognises that some studies may be less relevant than others due to differences in, for example, the characteristics of the settings or the ways that variables are measured.

The assessment of study quality is a contested and much debated issue in all research fields. Many published scales are available for assessing study quality. Each incorporates criteria relevant to the research design being evaluated. Quality scales for studies investigating the impact of interventions using (quasi) experimental research designs tend to emphasis establishing descriptive causality through minimising the effects of bias (for detailed discussion of issues associated with assessing study quality in this tradition see Waddington et al. 2017 ). Quality scales for appraising qualitative research tend to focus on the extent to which the study is authentic in reflecting on the meaning of the data (for detailed discussion of the issues associated with assessing study quality in this tradition see Carroll and Booth 2015 ).

3.7 Synthesis

A synthesis is more than a list of findings from the included studies. It is an attempt to integrate the information from the individual studies to produce a ‘better’ answer to the review question than is provided by the individual studies. Each stage of the review contributes toward the synthesis and so decisions made in earlier stages of the review shape the possibilities for synthesis. All types of synthesis involve some kind of data transformation that is achieved through common analytic steps: searching for patterns in data; Checking the quality of the synthesis; Integrating data to answer the review question (Thomas et al. 2012 ). The techniques used to achieve these vary for different types of synthesis and may appear more or less evident as distinct steps.

Statistical meta-analysis is an aggregative synthesis approach in which the outcome results from individual studies are transformed into a standardized, scale free, common metric and combined to produce a single pooled weighted estimate of effect size and direction. There are a number of different metrics of effect size, selection of which is principally determined by the structure of outcome data in the primary studies as either continuous or dichotomous. Outcome data with a dichotomous structure can be transformed into Odds Ratios (OR), Absolute Risk Ratios (ARR) or Relative Risk Ratios (RRR) (for detailed discussion of dichotomous outcome effect sizes see Altman 1991 ). More commonly seen in education research, outcome data with a continuous structure can be translated into Standardised Mean Differences (SMD) (Fitz-Gibbon 1984 ). At its most straightforward effect size calculation is simple arithmetic. However given the variety of analysis methods used and the inconsistency of reporting in primary studies it is also possible to calculate effect sizes using more complex transformation formulae (for detailed instructions on calculating effect sizes from a wide variety of data presentations see Lipsey and Wilson 2000 ).

The combination of individual effect sizes uses statistical procedures in which weighting is given to the effect sizes from the individual studies based on different assumptions about the causes of variance and this requires the use of statistical software. Statistical measures of heterogeneity produced as part of the meta-analysis are used to both explore patterns in the data and to assess the quality of the synthesis (Thomas et al. 2017a ).

In configurative synthesis the different kinds of text about individual studies and their results are meshed and linked to produce patterns in the data, explore different configurations of the data and to produce new synthetic accounts of the phenomena under investigation. The results from the individual studies are translated into and across each other, searching for areas of commonality and refutation. The specific techniques used are derived from the techniques used in primary research in this tradition. They include reading and re-reading, descriptive and analytical coding, the development of themes, constant comparison, negative case analysis and iteration with theory (Thomas et al. 2017b ).

4 Variation in Review Structures

All research requires time and resources and systematic reviews are no exception. There is always concern to use resources as efficiently as possible. For these reasons there is a continuing interest in how reviews can be carried out more quickly using fewer resources. A key issue is the basis for considering a review to be systematic. Any definitions are clearly open to interpretation. Any review can be argued to be insufficiently rigorous and explicit in method in any part of the review process. To assist reviewers in being rigorous, reporting standards and appraisal tools are being developed to assess what is required in different types of review (Lockwood and Geum Oh 2017 ) but these are also the subject of debate and disagreement.

In addition to the term ‘systematic review’ other terms are used to denote the outputs of systematic review processes. Some use the term ‘scoping review’ for a quick review that does not follow a fully systematic process. This term is also used by others (for example, Arksey and O’Malley 2005 ) to denote ‘systematic maps’ that describe the nature of a research field rather than synthesise findings. A ‘quick review’ type of scoping review may also be used as preliminary work to inform a fuller systematic review. Another term used is ‘rapid evidence assessment’. This term is usually used when systematic review needs to be undertaken quickly and in order to do this the methods of review are employed in a more minimal than usual way. For example, by more limited searching. Where such ‘shortcuts’ are taken there may be some loss of rigour, breadth and/or depth (Abrami et al. 2010 ; Thomas et al. 2013 ).

Another development has seen the emergence of the concept of ‘living reviews’, which do not have a fixed end point but are updated as new relevant primary studies are produced. Many review teams hope that their review will be updated over time, but what is different about living reviews is that it is built into the system from the start as an on-going developmental process. This means that the distribution of review effort is quite different to a standard systematic review, being a continuous lower-level effort spread over a longer time period, rather than the shorter bursts of intensive effort that characterise a review with periodic updates (Elliott et al. 2014 ).

4.1 Systematic Maps and Syntheses

One potentially useful aspect of reviewing the literature systematically is that it is possible to gain an understanding of the breadth, purpose and extent of research activity about a phenomenon. Reviewers can be more informed about how research on the phenomenon has been constructed and focused. This type of reviewing is known as ‘mapping’ (see for example, Peersman 1996 ; Gough et al. 2003 ). The aspects of the studies that are described in a map will depend on what is of most interest to those undertaking the review. This might include information such as topic focus, conceptual approach, method, aims, authors, location and context. The boundaries and purposes of a map are determined by decisions made regarding the breadth and depth of the review, which are informed by and reflected in the review question and selection criteria.

Maps can also be a useful stage in a systematic review where study findings are synthesised as well. Most synthesis reviews implicitly or explicitly include some sort of map in that they describe the nature of the relevant studies that they have identified. An explicit map is likely to be more detailed and can be used to inform the synthesis stage of a review. It can provide more information on the individual and grouped studies and thus also provide insights to help inform choices about the focus and strategy to be used in a subsequent synthesis.

4.2 Mixed Methods, Mixed Research Synthesis Reviews

Where studies included in a review consist of more than one type of study design, there may also be different types of data. These different types of studies and data can be analysed together in an integrated design or segregated and analysed separately (Sandelowski et al. 2012 ). In a segregated design, two or more separate sub-reviews are undertaken simultaneously to address different aspects of the same review question and are then compared with one another.

Such ‘mixed methods’ and ‘multiple component’ reviews are usually necessary when there are multiple layers of review question or when one study design alone would be insufficient to answer the question(s) adequately. The reviews are usually required, to have both breadth and depth. In doing so they can investigate a greater extent of the research problem than would be the case in a more focussed single method review. As they are major undertakings, containing what would normally be considered the work of multiple systematic reviews, they are demanding of time and resources and cannot be conducted quickly.

4.3 Reviews of Reviews

Systematic reviews of primary research are secondary levels of research analysis. A review of reviews (sometimes called ‘overviews’ or ‘umbrella’ reviews) is a tertiary level of analysis. It is a systematic map and/or synthesis of previous reviews. The ‘data’ for reviews of reviews are previous reviews rather than primary research studies (see for example Newman et al. ( 2018 ). Some review of reviews use previous reviews to combine both primary research data and synthesis data. It is also possible to have hybrid review models consisting of a review of reviews and then new systematic reviews of primary studies to fill in gaps in coverage where there is not an existing review (Caird et al. 2015 ). Reviews of reviews can be an efficient method for examining previous research. However, this approach is still comparatively novel and questions remain about the appropriate methodology. For example, care is required when assessing the way in which the source systematic reviews identified and selected data for inclusion, assessed study quality and to assess the overlap between the individual reviews (Aromataris et al. 2015 ).

5 Other Types of Research Based Review Structures

This chapter so far has presented a process or method that is shared by many different approaches within the family of systematic review approaches, notwithstanding differences in review question and types of study that are included as evidence. This is a helpful heuristic device for designing and reading systematic reviews. However, it is the case that there are some review approaches that also claim to use a research based review approach but that do not claim to be systematic reviews and or do not conform with the description of processes that we have given above at all or in part at least.

5.1 Realist Synthesis Reviews

Realist synthesis is a member of the theory-based school of evaluation (Pawson 2002 ). This means that it is underpinned by a ‘generative’ understanding of causation, which holds that, to infer a causal outcome/relationship between an intervention (e.g. a training programme) and an outcome (O) of interest (e.g. unemployment), one needs to understand the underlying mechanisms (M) that connect them and the context (C) in which the relationship occurs (e.g. the characteristics of both the subjects and the programme locality). The interest of this approach (and also of other theory driven reviews) is not simply which interventions work, but which mechanisms work in which context. Rather than identifying replications of the same intervention, the reviews adopt an investigative stance and identify different contexts within which the same underlying mechanism is operating.

Realist synthesis is concerned with hypothesising, testing and refining such context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations. Based on the premise that programmes work in limited circumstances, the discovery of these conditions becomes the main task of realist synthesis. The overall intention is to first create an abstract model (based on the CMO configurations) of how and why programmes work and then to test this empirically against the research evidence. Thus, the unit of analysis in a realist synthesis is the programme mechanism, and this mechanism is the basis of the search. This means that a realist synthesis aims to identify different situations in which the same programme mechanism has been attempted. Integrative Reviewing, which is aligned to the Critical Realist tradition, follows a similar approach and methods (Jones-Devitt et al. 2017 ).

5.2 Critical Interpretive Synthesis (CIS)

Critical Interpretive Synthesis (CIS) (Dixon-Woods et al. 2006 ) takes a position that there is an explicit role for the ‘authorial’ (reviewer’s) voice in the review. The approach is derived from a distinctive tradition within qualitative enquiry and draws on some of the tenets of grounded theory in order to support explicitly the process of theory generation. In practice, this is operationalised in its inductive approach to searching and to developing the review question as part of the review process, its rejection of a ‘staged’ approach to reviewing and embracing the concept of theoretical sampling in order to select studies for inclusion. When assessing the quality of studies CIS prioritises relevance and theoretical contribution over research methods. In particular, a critical approach to reading the literature is fundamental in terms of contextualising findings within an analysis of the research traditions or theoretical assumptions of the studies included.

5.3 Meta-Narrative Reviews

Meta-narrative reviews, like critical interpretative synthesis, place centre-stage the importance of understanding the literature critically and understanding differences between research studies as possibly being due to differences between their underlying research traditions (Greenhalgh et al. 2005 ). This means that each piece of research is located (and, when appropriate, aggregated) within its own research tradition and the development of knowledge is traced (configured) through time and across paradigms. Rather than the individual study, the ‘unit of analysis’ is the unfolding ‘storyline’ of a research tradition over time’ (Greenhalgh et al. 2005 ).

6 Conclusions

This chapter has briefly described the methods, application and different perspectives in the family of systematic review approaches. We have emphasized the many ways in which systematic reviews can vary. This variation links to different research aims and review questions. But also to the different assumptions made by reviewers. These assumptions derive from different understandings of research paradigms and methods and from the personal, political perspectives they bring to their research practice. Although there are a variety of possible types of systematic reviews, a distinction in the extent that reviews follow an aggregative or configuring synthesis logic is useful for understanding variations in review approaches and methods. It can help clarify the ways in which reviews vary in the nature of their questions, concepts, procedures, inference and impact. Systematic review approaches continue to evolve alongside critical debate about the merits of various review approaches (systematic or otherwise). So there are many ways in which educational researchers can use and engage with systematic review methods to increase knowledge and understanding in the field of education.

https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/

https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/evidence-summaries/teaching-learning-toolkit

https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=2914

Abrami, P. C. Borokhovski, E. Bernard, R. M. Wade, CA. Tamim, R. Persson, T. Bethel, E. C. Hanz, K. & Surkes, M. A. (2010). Issues in conducting and disseminating brief reviews of evidence. Evidence & Policy , 6 (3), 371–389.

Google Scholar

Altman, D.G. (1991) Practical statistics for medical research . London: Chapman and Hall.

Arksey, H. & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework, International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 8 (1), 19–32,

Article Google Scholar

Aromataris, E. Fernandez, R. Godfrey, C. Holly, C. Khalil, H. Tungpunkom, P. (2015). Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare , 13 .

Barnett-Page, E. & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review, BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9 (59), https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59 .

Brunton, G., Stansfield, C., Caird, J. & Thomas, J. (2017a). Finding relevant studies. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd edition, pp. 93–132). London: Sage.

Brunton, J., Graziosi, S., & Thomas, J. (2017b). Tools and techniques for information management. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd edition, pp. 154–180), London: Sage.

Carroll, C. & Booth, A. (2015). Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: Is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed? Research Synthesis Methods 6 (2), 149–154.

Caird, J. Sutcliffe, K. Kwan, I. Dickson, K. & Thomas, J. (2015). Mediating policy-relevant evidence at speed: are systematic reviews of systematic reviews a useful approach? Evidence & Policy, 11 (1), 81–97.

Chow, J. & Eckholm, E. (2018). Do published studies yield larger effect sizes than unpublished studies in education and special education? A meta-review. Educational Psychology Review 30 (3), 727–744.

Dickson, K., Vigurs, C. & Newman, M. (2013). Youth work a systematic map of the literature . Dublin: Dept of Government Affairs.

Dixon-Woods, M., Cavers, D., Agarwa, S., Annandale, E. Arthur, A., Harvey, J., Hsu, R., Katbamna, S., Olsen, R., Smith, L., Riley R., & Sutton, A. J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology 6:35 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-35 .

Elliott, J. H., Turner, T., Clavisi, O., Thomas, J., Higgins, J. P. T., Mavergames, C. & Gruen, R. L. (2014). Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence-practice gap. PLoS Medicine, 11 (2): e1001603. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001603 .

Fitz-Gibbon, C.T. (1984) Meta-analysis: an explication. British Educational Research Journal , 10 (2), 135–144.

Gough, D. (2007). Weight of evidence: a framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Research Papers in Education , 22 (2), 213–228.

Gough, D., Thomas, J. & Oliver, S. (2012). Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Systematic Reviews, 1( 28).

Gough, D., Kiwan, D., Sutcliffe, K., Simpson, D. & Houghton, N. (2003). A systematic map and synthesis review of the effectiveness of personal development planning for improving student learning. In: Research Evidence in Education Library. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

Gough, D., Oliver, S. & Thomas, J. (2017). Introducing systematic reviews. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd edition, pp. 1–18). London: Sage.

Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., Kyriakidou, O. & Peacock, R. (2005). Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: A meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 61 (2), 417–430.

Hargreaves, D. (1996). Teaching as a research based profession: possibilities and prospects . Teacher Training Agency Annual Lecture. Retrieved from https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=2082 .

Hart, C. (2018). Doing a literature review: releasing the research imagination . London. SAGE.

Jones-Devitt, S. Austen, L. & Parkin H. J. (2017). Integrative reviewing for exploring complex phenomena. Social Research Update . Issue 66.

Kugley, S., Wade, A., Thomas, J., Mahood, Q., Klint Jørgensen, A. M., Hammerstrøm, K., & Sathe, N. (2015). Searching for studies: A guide to information retrieval for Campbell Systematic Reviews . Campbell Method Guides 2016:1 ( http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/images/Campbell_Methods_Guides_Information_Retrieval.pdf ).

Lipsey, M.W., & Wilson, D. B. (2000). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Lockwood, C. & Geum Oh, E. (2017). Systematic reviews: guidelines, tools and checklists for authors. Nursing & Health Sciences, 19, 273–277.

Nelson, J. & Campbell, C. (2017). Evidence-informed practice in education: meanings and applications. Educational Research, 59 (2), 127–135.

Newman, M., Garrett, Z., Elbourne, D., Bradley, S., Nodenc, P., Taylor, J. & West, A. (2006). Does secondary school size make a difference? A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 1 (1), 41–60.

Newman, M. (2008). High quality randomized experimental research evidence: Necessary but not sufficient for effective education policy. Psychology of Education Review, 32 (2), 14–16.

Newman, M., Reeves, S. & Fletcher, S. (2018). A critical analysis of evidence about the impacts of faculty development in systematic reviews: a systematic rapid evidence assessment. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 38 (2), 137–144.

Noblit, G. W. & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Oancea, A. & Furlong, J. (2007). Expressions of excellence and the assessment of applied and practice‐based research. Research Papers in Education 22 .

O’Mara-Eves, A., Thomas, J., McNaught, J., Miwa, M., & Ananiadou, S. (2015). Using text mining for study identification in systematic reviews: a systematic review of current approaches. Systematic Reviews 4 (1): 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-5 .

Pawson, R. (2002). Evidence-based policy: the promise of “Realist Synthesis”. Evaluation, 8 (3), 340–358.

Peersman, G. (1996). A descriptive mapping of health promotion studies in young people, EPPI Research Report. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

Petticrew, M. & Roberts, H. (2005). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide . London: Wiley.

Sandelowski, M., Voils, C. I., Leeman, J. & Crandell, J. L. (2012). Mapping the mixed methods-mixed research synthesis terrain. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6 (4), 317–331.

Smyth, R. (2004). Exploring the usefulness of a conceptual framework as a research tool: A researcher’s reflections. Issues in Educational Research, 14 .

Thomas, J., Harden, A. & Newman, M. (2012). Synthesis: combining results systematically and appropriately. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (pp. 66–82). London: Sage.

Thomas, J., Newman, M. & Oliver, S. (2013). Rapid evidence assessments of research to inform social policy: taking stock and moving forward. Evidence and Policy, 9 (1), 5–27.

Thomas, J., O’Mara-Eves, A., Kneale, D. & Shemilt, I. (2017a). Synthesis methods for combining and configuring quantitative data. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An Introduction to Systematic Reviews (2nd edition, pp. 211–250). London: Sage.

Thomas, J., O’Mara-Eves, A., Harden, A. & Newman, M. (2017b). Synthesis methods for combining and configuring textual or mixed methods data. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd edition, pp. 181–211), London: Sage.

Tsafnat, G., Dunn, A. G., Glasziou, P. & Coiera, E. (2013). The automation of systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 345 (7891), doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f139 .

Torgerson, C. (2003). Systematic reviews . London. Continuum.

Waddington, H., Aloe, A. M., Becker, B. J., Djimeu, E. W., Hombrados, J. G., Tugwell, P., Wells, G. & Reeves, B. (2017). Quasi-experimental study designs series—paper 6: risk of bias assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 89 , 43–52.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Education, University College London, England, UK

Mark Newman & David Gough

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mark Newman .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Oldenburg, Germany

Olaf Zawacki-Richter

Essen, Germany

Michael Kerres

Svenja Bedenlier

Melissa Bond

Katja Buntins

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Newman, M., Gough, D. (2020). Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application. In: Zawacki-Richter, O., Kerres, M., Bedenlier, S., Bond, M., Buntins, K. (eds) Systematic Reviews in Educational Research. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-27602-7_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-27602-7_1

Published : 22 November 2019

Publisher Name : Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN : 978-3-658-27601-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-658-27602-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Literature Reviews

Introduction, what is a literature review.

- Literature Reviews for Thesis or Dissertation

- Stand-alone and Systemic Reviews

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Texts on Conducting a Literature Review

- Identifying the Research Topic

- The Persuasive Argument

- Searching the Literature

- Creating a Synthesis

- Critiquing the Literature

- Building the Case for the Literature Review Document

- Presenting the Literature Review

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Higher Education Research

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mixed Methods Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Politics of Education

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Educational Research Approaches: A Comparison

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- History of Education in Europe

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Literature Reviews by Lawrence A. Machi , Brenda T. McEvoy LAST REVIEWED: 27 October 2016 LAST MODIFIED: 27 October 2016 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0169

Literature reviews play a foundational role in the development and execution of a research project. They provide access to the academic conversation surrounding the topic of the proposed study. By engaging in this scholarly exercise, the researcher is able to learn and to share knowledge about the topic. The literature review acts as the springboard for new research, in that it lays out a logically argued case, founded on a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge about the topic. The case produced provides the justification for the research question or problem of a proposed study, and the methodological scheme best suited to conduct the research. It can also be a research project in itself, arguing policy or practice implementation, based on a comprehensive analysis of the research in a field. The term literature review can refer to the output or the product of a review. It can also refer to the process of Conducting a Literature Review . Novice researchers, when attempting their first research projects, tend to ask two questions: What is a Literature Review? How do you do one? While this annotated bibliography is neither definitive nor exhaustive in its treatment of the subject, it is designed to provide a beginning researcher, who is pursuing an academic degree, an entry point for answering the two previous questions. The article is divided into two parts. The first four sections of the article provide a general overview of the topic. They address definitions, types, purposes, and processes for doing a literature review. The second part presents the process and procedures for doing a literature review. Arranged in a sequential fashion, the remaining eight sections provide references addressing each step of the literature review process. References included in this article were selected based on their ability to assist the beginning researcher. Additionally, the authors attempted to include texts from various disciplines in social science to present various points of view on the subject.

Novice researchers often have a misguided perception of how to do a literature review and what the document should contain. Literature reviews are not narrative annotated bibliographies nor book reports (see Bruce 1994 ). Their form, function, and outcomes vary, due to how they depend on the research question, the standards and criteria of the academic discipline, and the orthodoxies of the research community charged with the research. The term literature review can refer to the process of doing a review as well as the product resulting from conducting a review. The product resulting from reviewing the literature is the concern of this section. Literature reviews for research studies at the master’s and doctoral levels have various definitions. Machi and McEvoy 2016 presents a general definition of a literature review. Lambert 2012 defines a literature review as a critical analysis of what is known about the study topic, the themes related to it, and the various perspectives expressed regarding the topic. Fink 2010 defines a literature review as a systematic review of existing body of data that identifies, evaluates, and synthesizes for explicit presentation. Jesson, et al. 2011 defines the literature review as a critical description and appraisal of a topic. Hart 1998 sees the literature review as producing two products: the presentation of information, ideas, data, and evidence to express viewpoints on the nature of the topic, as well as how it is to be investigated. When considering literature reviews beyond the novice level, Ridley 2012 defines and differentiates the systematic review from literature reviews associated with primary research conducted in academic degree programs of study, including stand-alone literature reviews. Cooper 1998 states the product of literature review is dependent on the research study’s goal and focus, and defines synthesis reviews as literature reviews that seek to summarize and draw conclusions from past empirical research to determine what issues have yet to be resolved. Theoretical reviews compare and contrast the predictive ability of theories that explain the phenomenon, arguing which theory holds the most validity in describing the nature of that phenomenon. Grant and Booth 2009 identified fourteen types of reviews used in both degree granting and advanced research projects, describing their attributes and methodologies.

Bruce, Christine Susan. 1994. Research students’ early experiences of the dissertation literature review. Studies in Higher Education 19.2: 217–229.

DOI: 10.1080/03075079412331382057