- Skip to main content

Life & Letters Magazine

The Value of the Liberal Arts

By Hina Azam September 20, 2022 facebook twitter email

Those of us who teach in liberal arts colleges are passionate about the value of a liberal arts education. But for those outside of academia – even for those who might have received a degree in UT’s College of Liberal Arts – the precise meaning of “liberal arts” can be murky. What, exactly, is meant by the “liberal arts”? What is the history of the idea, and how does it translate into the educational concept we know as a “liberal-arts curriculum,” or, more broadly, a “liberal education”? What is the value of a liberal arts education to both individual and collective life? This essay presents a brief overview of the idea, history, purposes, and values of liberal arts education, so that you, our readers, may understand the passion that inspires our faculty’s teaching and scholarship, and be similarly inspired.

What are the Liberal Arts?

The idea of the liberal arts originates in ancient Greece and was further developed in medieval Europe. Classically understood, it combined the four studies of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music – known as the quadrivium – with the three additional studies of grammar, rhetoric, and logic – known as the trivium . These artes liberales were meant to teach both general knowledge and intellectual skills, and thus train the mind. This training of the mind as well as this foundational body of content knowledge and intellectual skills was regarded by scholars and educators as necessary for all human beings – and especially a society’s leaders – in order to live well, both individually and collectively.

These liberal arts were distinguished from vocational or clinical arts, such as law, medicine, engineering, and business. These latter were conceived as servile arts – i.e. arts that served concrete production or construction. These productive/constructive arts were also known as artes mechanicae , “mechanical arts,” which included crafts such as weaving, agriculture, masonry, warfare, trade, cooking, and metallurgy. In contrast to the vocational or mechanical arts, the liberal arts put greater weight on intellectual skills – the ability to think and communicate clearly, and to analyze and solve problems. But more distinctively, the liberal arts emphasized learning and the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, independent of immediate application. The liberal arts taught not only bodies of knowledge, but – more dynamically – how to go about finding and creating knowledge – that is, how to learn. Finally, the liberal arts taught not only how to think and do, but also how to be – with others and with oneself, in the natural world and the social world. They were thus centrally concerned with ethics.

Notably, the term “liberal arts” has nothing to do with liberalism in the contemporary political or partisan sense; the opposite of “liberal” here is not “conservative.” Rather, the term goes back to the Latin root signifying “freedom,” as opposed to imprisonment or subjugation. Think here of the English word “liberty.” The liberal arts were historically connected to freedom in that they encompassed the types of knowledge and skills appropriate to free people, living in a free society. The term “art” in this phrase also must be understood correctly, for it does not refer to “art” as we use it today in its creative sense, to denote the fine and performing arts. Rather, from the Latin root ars , “art” is here used to refer to skill or craft. The “liberal arts,” then, may be thought of as liberating knowledges, or alternatively, the skills of being free.

What is a Liberal Arts Education ?

A liberal (arts) education is a curriculum designed around imparting core knowledge and skills through engagement with a wide range of subjects and disciplines. This core knowledge is taught through general education courses typically drawn from the humanities, (creative) arts, natural sciences, and social sciences. The humanities include disciplines such as language, literature, poetry, rhetoric, philosophy, religion, history, law, geography, archaeology, anthropology, politics, and classics. Natural sciences include subjects such as geology, chemistry, physics, and life sciences such as biology. Social sciences comprise disciplines such as sociology, economics, linguistics, psychology, and education. Through a core curriculum or general education courses, students gain a basic knowledge of the physical and natural world as well as of human ideas, histories, and practices.

A liberal arts education comprises more than learning only content, but also honing skills and cultivating values. Intellectual and practical skills at the heart of the liberal arts are reading comprehension, inquiry and analysis, critical and creative thinking, written and oral communication, information and quantitative literacy, teamwork and problem-solving. Values that are central to liberal education are personal and social responsibility, civic knowledge and engagement, intercultural knowledge and competence, ethical reasoning and action, and lifelong learning.

Why a Liberal Education? Purposes and Values

Four overarching purposes anchor the idea of an education in the liberal arts. One of those is liberty . As mentioned above, the traditional idea of the liberal arts was an education that befitted a free person, one who was fit to participate freely in the life of society. The modern casting of this idea is that a broad education does not limit one to a particular profession or occupation, but rather, is meant for any life path – it prepares the mind for a variety of possible futures and for constructive participation in a civil democratic society. The interconnection between liberal education and human freedom cannot be over-emphasized, and it was at the forefront of the minds of the great political theorists and educators of the western tradition. Those with insufficient knowledge and skills would easily fall prey to demagogues and agents of chaos, and pervasive ignorance and lack of intellectual skill would eat away at a polity’s foundations. Only an informed citizenry – who had familiarity with and foundational understanding in the major areas of knowledge, and who had the requisite skills to both process existing information and seek out reliable new information – would be able to uphold and maintain a democratic society and stave off a decline into tyranny and despotism. As Thomas Jefferson, a major architect of the American public university, held, “Wherever the people are well informed they can be trusted with their own government.” [1]

Another central purpose of a liberal arts education is the inculcation of the principle of human worth. This purpose is built on values collectively known as humanism : the idea that human life, individual and collective, has intrinsic value; the idea that human beings are endowed with rights to life, liberty, property, and a number of other rights that we know as “human rights”; that human beings are fundamentally equal, even if they are not the same, and that that equality should translate into both political and legal equality. This ideal of humanism is not in opposition to religious beliefs and practices; however, it regards the public sphere as one in which all should be able to participate regardless of religious beliefs and practices. Humanism mirrors the principle of a common or shared humanity, even while recognizing differences of experience, perspective, and resources. This vision is at the heart of that facet of liberal arts known as the humanities . Writes Robert Thornett, “Humanities is, in fact, education in how to be a human being.” [2] A liberal arts education exposes learners to diverse types of knowledge – which allow for understanding and empathy with others – within a humanistic framework that aims for deeper unity and synthesis. This approach to knowledge serves as a bulwark against social, political and ideological forces that seek to drive wedges between human beings, and that all too often culminate in violence and oppression.

A third purpose of liberal education is to provide a space for contemplation of truth and virtue , based on the conviction that such contemplation is necessary for the free mind, and that informed explorations of these notions lead to the formation of better human beings. The liberal arts are where students have opportunity to consider the “big questions”: What is true? What is good? What is just? What is beautiful? This contemplation is what fires the imaginations of our students, and what makes the liberal arts curriculum unlike any other curriculum. Vartan Gregorian explains the unique character of liberal arts education, writing that “the deep-seated yearning for knowledge and understanding endemic to human beings is an ideal that a liberal arts education is singularly suited to fulfill.” [3]

A fourth value of liberal arts education is its emphasis on the skills of learning , and of constructing knowledge out of information. We live in an increasingly complex information environment, where the sheer quantity of information – and its intentional manipulation into disinformation – overwhelms people’s abilities to make sense of it all. Without sufficient training, people are less equipped to find reliable information, to understand what they encounter, and to process that information, mentally and emotionally, into rational knowledge that can form the basis of ethical evaluation and action . This is a matter of grave importance for all human beings – in their capacity as students, citizens, consumers, workers, and people in relationships. Gregorian long ago identified the problem of information overload, and the function of education, in an interview with Bill Moyers: “Unfortunately, the information explosion … does not equal knowledge. … So, we’re facing a major problem: how to structure information into knowledge. Because … there are great possibilities of manipulating our society by inundating us with undigested information… paralyzing our choices by giving so much that we cannot possibly digest it.” [4]

Given this paralyzing deluge of information, he continues, “The teaching profession, the universities, have to provide connections … connections between subjects, connections between disciplines … to provide some kind of intellectual coherence.” In the final analysis, suggests Gregorian, “Education’s sole function is now, possibly, [to] provide an introduction to learning.”

The purposes and values outlined above cannot easily be fulfilled outside of an intentional liberal arts curriculum. One does meet people who are driven to read widely and to pursue lifelong learning; to develop skills of information critique and lucid oral and written communication; to hold steadily to the vision of a shared humanity and humane ethical conduct; to undertake the ethical burden of preserving political liberties and civil rights; to engage in sustained contemplation of truth and practice of virtue; to perceive the interconnectedness of different spheres of knowledge and therefore of our world; and to develop the facility to synthesize chaotic data and irrational information into rational and cogent knowledge. But these goals are far more difficult to achieve outside of the structured, collective, and compulsory activities of the college classroom and away from teachers whose minds are perpetually set to these concerns. For too many, such integrated learning is out of reach or undervalued. Meanwhile, the insufficient attainment and integration of broad knowledge, intellectual skills, and ethical reflection is wreaking havoc on our society and national culture; on our quality of life morally, intellectually, psychologically, and physically; and finally, on our planet, which is increasingly unable to withstand humanity’s relentless onslaught and is fast losing the capacity to sustain its assailant.

Liberal-arts education is not found in any one course, classroom, or teacher. It is a composite formation, attained over time through series of courses and learning opportunities that together coalesce in the minds of students. Each instructor, and each course, contributes elements that are oriented toward the purposes identified above. It is through the process of seeing the interconnections between different areas of knowledge, using diverse intellectual skills, that the human mind gains the capacity for liberation.

[1] https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/genesis-university-virginia

[2] Robert Thornett, “What Are College Students Paying For?” at The Quillette , June 2, 2022 [ https://quillette.com/2022/06/02/what-are-college-students-paying-for-the-stephen-curry-effect-and-getting-back-to-basics/

[3] Historian and former Brown University President Vartan Gregorian, in his essay “American Higher Education: An Obligation to the Future” at https://higheredreporter.carnegie.org/introduction/ .

[4] “Vartan Gregorian: Living in the Information Age,” interview with Bill Moyers, at https://billmoyers.com/content/vartan-gregorian/ .

- Get Started

- Join Our Team

- (212) 262-3500

- Initial Consultation

- IvyWise Roundtable

- School Placement

- Test Prep & Tutoring

- Early College Guidance

- College Admissions Counseling

- Academic Tutoring

- Test Prep Tutoring

- Research Mentorship

- Academic Advising

- Transfer Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- School Partnerships

- Webinars and Events

- IvyWise By The Numbers

- Testimonials

- Dr. Kat Cohen

- IvyWise In The News

- IvyWise Gives Back

- IvyWise Blog

- Just Admit It! Podcast

- Admission Statistics

The Value of a Liberal Arts Education in Today’s World

By an IvyWise College Admissions Counselor

The growing cost of college combined with the increasing demand for students in career-ready fields such as engineering, finance, computer science, and medicine has left many people challenging the liberal arts. Much of the conversation surrounding higher education is focused on value and ROI. What majors earn the most right out of college? Which institutions produce graduates with the highest salaries? When deciding how to choose a major , students might run into some difficulty. So as you approach your college search you may find yourself asking: Is a liberal arts education still relevant in the 21st century?

In short: yes. In our rapidly changing global economy, with millennials averaging five to seven career changes in a lifetime, one could argue that a liberal arts education may be more valuable than ever before. In fact, a 2021 study by the Association of American Colleges and Universities found that the majority of employers nationwide value employees with a well-rounded liberal arts education.

Why Consider a Liberal Arts Education?

A liberal arts education is intended to expand the capacity of the mind to think critically and analyze information effectively. It develops and strengthens the brain to think within and across all disciplines so that it may serve the individual over a lifetime. Students choose a specific major when they attend a liberal arts college, but they are also required to take courses in a variety of disciplines, where there is a heavy focus on writing and communicating effectively. The depth and breadth of a liberal arts education results in employees with strong research, creative problem-solving, and analytical reasoning skills — all skills that are highly valued in multiple industries.

Liberal arts colleges also tend to be smaller institutions that focus on undergraduates and teaching. The hallmarks of liberal arts colleges, such as Bowdoin, Williams, and Amherst, are small class sizes, close access to professors and undergraduate research opportunities, and a broad-based academic program in in the core subject areas of mathematics, the social sciences, and the hard sciences.

Art History Professor T. Kitao of Swarthmore delivered an address with a poignant summary of the value of a liberal education:

“The knowledge you learn about the subject of the course is its nominal benefit. It is like the stated moral at the end of a fable. The real substance of learning is something more subtle and complex and profound, which cannot be easily summarized — like the story itself. It has to be experienced, and it is as an experience that it becomes an integral part of the person. Learning how to learn by learning how to think makes a well-educated person.”

A Liberal Arts Degree is Not Useless in the 21st Century Job Market

In our increasingly evolving, globalized world, liberal arts colleges produce critical thinkers who have the confidence and flexibility to continually learn new skills and material. In his book, The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century , Thomas Friedman states that “in an age when parts or all of many jobs are constantly going to be exposed to digitization, automation, and outsourcing… it is not only what you know but how you learn that will set you apart. Because what you know today will be out-of-date sooner than you think.”

Even if you are certain about a career path you want to pursue, a liberal arts background can help you make it to the top of your field. For example, a student who is certain she wants to be a doctor could attend a liberal arts college pursuing a major in psychology and minor in economics before attending medical school. As a doctor, she could call upon her psychology degree to better understand and relate to her patients. The strong writing skills gained from her liberal arts background would help her to effectively communicate her research findings through publications. Her economics minor would help her to be successful if she decided to start and grow her own private practice.

It’s also important to note that while many families are concerned with immediate ROI and degrees that command high starting salaries right out of college, AAC&U’s “How Liberal Arts and Sciences Majors Fare in Employment” report found that by their 50s, liberal arts majors on average earn more annually than those who majored as undergraduates in professional or pre-professional fields. While STEM majors tend to earn the highest salaries out of college and typically earn more overall, liberal arts degree holders are seeing a great ROI — it’s just not as immediate.

Steve Jobs once said, “Technology alone is not enough. It’s technology married with the liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the results that make our hearts sing.” It’s important to remember that, while there is a demand for STEM students and specialized degrees, it is possible to pursue a liberal arts education with intent and create multiple paths to career success in the process.

KnowledgeBase Resources

The IvyWise KnowlegeBase provides the most current information about the admissions process. Select from the content categories below:

- Admission Decisions

- Admission Rates

- Admissions Interviews

- Admissions Trends

- Athletic Recruiting

- Choosing a College

- College Application Tips

- College Essay Tips

- College Lists

- College Majors

- College Planning

- College Prep

- College Visits

- Common Application

- Course Planning

- Demonstrated Interest

- Early Decision/Early Action

- Executive Functioning

- Extracurricular Activities

- Financial Aid

- Independent Project

- International Students

- Internships

- Law School Admissions

- MBA Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Middle School

- Outside Reading

- Recommendation Letters

- Summer Planning

- Test Prep Tips

- U.K. Admissions

Home » IvyWise KnowledgeBase » IvyWise Resources » All Articles » The Value of a Liberal Arts Education in Today’s World

The Value of Liberal Arts Education in College or University Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

The value of liberal arts, works cited.

A key component of our modern society is its educational system. Through this system, individuals are provided with the tools necessary to play a part in the growth and ultimate advancement of the society. Citizens and governments all over the world have recognized the value of education.

The number of institutes of higher learning in the country has increased significantly and efforts have been made to ensure that more students attend college and university. However, the cost of higher education has risen significantly and students are pressured to focus on courses that promise high returns. The demand for career-related education has led to the undervaluing of Liberal Arts Education by most parents and governments.

Instead, emphasis has been given to science and business related courses, which have an obvious economic payoff. This paper will argue that liberal arts education should be encouraged since it adds value to society by offering the ideal college experience that promotes intellectual growth, personal development, and the acquisition of a wide range of skills by the student.

Liberal arts promote the development of higher-order intellectual skills in students. The student acquires intellectual capacities such as the ability to solve problems with multiple solutions, critical thinking, and skillful use of technology. Good thinking habits are acquired by the student and he/she is able to identify and grasp new concepts.

The ability of an individual to engage in problem solving activities is sharpened by liberal arts education. Harris documents that a liberal arts education assists the student to think in an ordered fashion therefore increasing his/her ability to do intellectual work (1). An important fact is that this skill can be used in a wide range of settings since the knowledge of organized solutions is not confined to any specific discipline.

Liberal arts education helps students avoid the narrow vision that overemphasizes specialization causes. Career driven education often leads to compartmentalization as students are made to focus entirely on their expert courses.

This specialization is caused by the idea that students only need to undertake the courses that lead to work and money. This habit leads to the development of narrow world-views and a tunnel vision (Kazanjian 59). Students who are subjected to this form of education lack the fundamental skills that can make them ready for new challenges that might arise in their profession.

Hart asserts that employers are against education that only instills specialized skills and knowledge in the college graduates (1). Instead, they prefer education that is well rounded in nature and enhances the intellectual skills of the student. Liberal arts education provides this well-rounded education since it recognizes that a student might have to deal with issues that are not related to his/her area of specialization.

A liberal arts education offers practical intellectual foundation necessary for students to be successful in the modern work environment. Today’s workplace is complex in nature and the worker is required to have some critical knowledge and skills in order to be more productive.

Forest demonstrates that managers in major corporations are looking for employees who can communicate efficiently, solve problems independently, and show effective use of technology (402). This wide range of traits cannot be acquired through education that only focuses on career driven courses. A liberal arts education provides the student with all these desirable traits therefore making them competitive in the work environment.

The liberal arts education gives the student a global perspective and promotes effective citizenship. The knowledge of human cultures provided by this education is especially significant in today’s globalized world.

The career-driven education provided to most students does not prepare them to be successful in the global economy. Research by Hart indicates that most recent college graduates lack the skills necessary to operate at the level of global economy (6). The liberal arts education offers the solution to this by providing college and university students with global competence.

A liberal arts education enhances innovation and creativity in the students. A key characteristic of liberal arts is providing knowledge in a wide variety of subjects. Harris asserts that the wide range of knowledge stimulates creativity in the student (3). Students are able to come up with ideas inspired by a wide range of materials.

The knowledge on many subjects also acts as motivation for the students to be creative. For this reason, graduates who have a liberal arts education program are more likely to contribute to innovation in the workplace environment. Hart suggests that employers are keen to find such innovative graduates (7).

Liberal arts education promotes happiness and the enjoyment by life. This education recognizes that life is rich and that education can be a source of pleasure for the student. It therefore encourages students to appreciate art and see beauty in humanity. By studying poetry, literature, and historical characters student develops a deep appreciation of life.

Harris demonstrates that the enjoyment and happiness fostered by liberal art education are beneficial to the individual and the society (6). Happier individuals are more satisfied with their lives and are more likely to engage in activities for the good of their community. Happiness also contributes to higher work productivity since a happy person will have lower rates of depression and mental illnesses.

Liberal arts education helps in the development of good communication skills by the individual. Effective communication is the foundation of all relationships since it is the means through which human beings interact.

Good communication skills enable people to properly communicate their ideas and relate with others. Kazanjian asserts that for an organization to achieve its goals workers must learn how to communicate with each other effectively and treat each other with respect (62). The acquisition of good writing and reading skills is deemed integral to the future success of the individual. Students in liberal art programs are required to develop skills in writing and making oral presentations.

Forest reveals that students are helped to acquire the needed self-confidence to communicate effectively (402). Such students are better equipped to handle different situations in the real world environment. Hart declares that employers are looking for graduates who have good communication skills that will promote success in the work setting (7). These are the kind of graduates that liberal arts education produces.

Liberal art education enhances social skills of the individual and these social skills are integral in all social settings and work environments. Forest notes that liberal arts makes an emphasis on the significance of human relationships in all settings (402). Students are taught to demonstrate respect in all relationships.

This leads to the development of good personal and work relationships. Forest reveals that students with a liberal art education background show greater sensitivity to their fellow human beings and co-workers (Kazanjian 62). The liberal arts also encourage the individual to develop a sense of social responsibility. Exposure to a wide range of cultures promotes the appreciation of diversity.

Students are taught to not only respect differences but also appreciate them. By learning about various cultures and traditions, students develop an appreciation of diverse cultures. The moral standing of the individual is also promoted by the liberal arts. By studying the early philosophers, the sense of ethics and integrity in the student is promoted.

This paper is set out to argue that a liberal art education provides value to the student and the society. It began by noting that the perception that a liberal arts education leaves a student with few career options has contributed to the negative view of the value of this education by many members of the public.

The paper has demonstrated that liberal art education promotes the intellectual growth of the individual and encourages creativity. Contrary to popular belief, liberal arts education equips the student with the skills needed in the modern work place. The paper has revealed that liberal arts education is not concerned with developing skills that are focused on a particular career.

Instead, the education offered leads to the development of a well-rounded individual who has general knowledge and the intellectual skills necessary to function in a wide range of environments. The education also promotes personal growth and development of the student. Considering the many positive values of liberal art education, the public and governments should promote these programs in all institutes of higher learning.

Forest, James. Higher Education in the United States: An Encyclopedia . NY: ABC-CLIO, 2002. Print.

Hart, Peter. Should Colleges Prepare Students To Succeed In Today’s Global Economy? Washington, DC: Peter Hart Research Associates, Inc., 2006. Print.

Harris, Robert. On the Purpose of a Liberal Arts Education . 1991. Web.

Kazanjian, Michael. Learning Values Lifelong: From Inert Ideas to Wholes . Amsterdam: Rodipi, 2002. Print.

- Alternative Outlook on Education

- The six principles by Boyer

- Paintings by Edward Hopper and Thomas Hart Benton

- “Aspirin for the Primary Prevention of Stroke” by Hart et al.

- Thomas Hart Benton' and Faith Ringgold's Art Comparison

- Public Education in USA

- The general Liberation Education

- Solutions to instructional problems based on five key contextual perspectives

- Education System in America

- Brown vs. Board of Education

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, December 19). The Value of Liberal Arts Education in College or University. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-value-of-liberal-arts-education-in-college-or-university/

"The Value of Liberal Arts Education in College or University." IvyPanda , 19 Dec. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/the-value-of-liberal-arts-education-in-college-or-university/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'The Value of Liberal Arts Education in College or University'. 19 December.

IvyPanda . 2018. "The Value of Liberal Arts Education in College or University." December 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-value-of-liberal-arts-education-in-college-or-university/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Value of Liberal Arts Education in College or University." December 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-value-of-liberal-arts-education-in-college-or-university/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Value of Liberal Arts Education in College or University." December 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-value-of-liberal-arts-education-in-college-or-university/.

The Value of a Liberal Arts Education is More Than Most Know

Columns appearing on the service and this webpage represent the views of the authors, not of The University of Texas at Austin.

“What are you going to do with that?” Many new graduates will hear this question in the coming weeks.

For a business or computer science graduate, the answers seem obvious. What about someone studying a liberal arts field, like English or history or philosophy? A common misconception sees these as useless subjects or a waste of valuable resources. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Given the skills employers want, the traits we need in the next generation of leaders, and the qualities we value in our neighbors and friends, we might well ask the liberal arts grad, “What can’t you do with that?”

The main concern people have about liberal arts is marketability. Where are the jobs for people studying ancient Greek or African history? Everywhere. Because what those students are learning, alongside verb forms and dates, are the skills that appear time and again on top of employers’ wish lists. Skills such as persuasion, collaboration and creativity.

Does this mean that a liberal arts degree is as financially lucrative as computer science or petroleum engineering? No. But liberal arts majors do just fine in the workplace. Liberal arts students go on to earn good livings in a wide variety of fields, including technology.

In fact, the median annual income of a liberal arts major is just 8% lower than the median for all majors and more than one-third higher than the median income of people without a college degree.

Liberal arts offer not just financial value, but also personal, social and cultural values. The liberal arts take their name from the Latin word “liber,” which means “free.” Originally this referred to the education of free persons as distinct from slaves, but freedom is still at the root of the liberal arts. Liberal arts are a privilege of a free society, and the study of the liberal arts helps to keep us free.

Why is this? Contrary to what some would have us believe, our financial and social well-being depends on how we respond to the kinds of open-ended questions that liberal arts fields are asking. A computer scientist wants to invent a cool new app or technology. Whether he does a good job is measured by how much money his product earns.

As we see all too often, little thought is given to the social effects of these new technologies. They cause serious harm that people trained in writing computer code and making money may be unable or unwilling to address. Earnings can’t measure the things that most of us really care about when we think about new technologies.

This is where the liberal arts come in. The bedrock of a liberal arts education is the ability to understand a complex situation from many different viewpoints. To understand that the same information may look different to different people, or even to the same person at different times. We need the liberal arts to address questions that have no one right answer. And most of the important questions facing society are questions like this.

For instance, with all the technologies revolutionizing our society, how should we balance the need for accurate news and information with individual free speech? Where is the line between a legitimate business use of personal data and exploitation? Who gets to decide? So far, technology companies have done a lousy job of grappling with these questions. Some history majors, with their rich understanding of how complex forces shape society over time, would be a great idea.

Such skills have value in lots of places besides the workplace. The philosophy major on the church executive board is thinking about how the bedrock values of his community should inform decisions about replacing the roof or hiring a new Sunday school teacher. The English major participating in an environmental advocacy group can use her rhetorical and analytical skills to narrow the gap between the near-unanimous scientific consensus on climate change and political inaction on the issue.

The mistaken view that liberal arts are not financially valuable creates the more damaging idea that some fields of study have financial value, while others have social values. With liberal arts, we get both. Our society depends on it.

Deborah Beck is an associate professor of classics at The University of Texas at Austin.

A version of this op-ed appeared in The Hill .

Explore Latest Articles

Jul 18, 2024

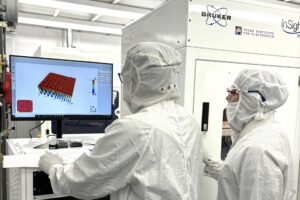

UT’s Texas Institute for Electronics Awarded $840M To Build a DOD Microelectronics Manufacturing Center, Advance U.S. Semiconductor Industry

Jul 17, 2024

Paving the Way to Extremely Fast, Compact Computer Memory

Jul 16, 2024

Four Longhorns Receive Fulbright U.S. Scholar Awards for 2024-2025

The Value of a Liberal Arts Education

It is often said: the university of mississippi is the flagship liberal arts university in the state of mississippi. what does this mean and, what is the value of a liberal arts education.

From the origins of Western civilization in the ancient world comes the concept of a liberal arts education. The term comes from the Greek word eleutheros and the Latin word liber , both meaning “free.” For free (male) citizens to fully participate in Athenian democracy, they needed certain skills in critical thinking and communication developed through a broad education in the verbal arts – grammar, logic, and rhetoric – and the numerical arts – arithmetic, astronomy, music, and geometry. Such an education celebrated and nurtured human freedom and early democracy.

In modern times, we can look to the American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) for a contemporary understanding of this concept.

“Liberal education is an approach to learning that empowers individuals and prepares them to deal with complexity, diversity, and change. It provides students with broad knowledge of the wider world (e.g. science, culture, and society) as well as in-depth study in a specific area of interest. A liberal education helps students develop a sense of social responsibility, as well as strong and transferable intellectual and practical skills such as communication, analytical and problem-solving skills, and a demonstrated ability to apply knowledge and skills in real-world settings. The broad goals of liberal education have been enduring even as the courses and requirements that comprise a liberal education have changed over the years. Today, a liberal education usually includes a general education curriculum that provides broad learning in multiple disciplines and ways of knowing, along with more in-depth study in a major.” —Association of American Colleges and Universities

You regularly will hear proponents of a liberal arts education cite some combination of the skills listed above as the mark of a well-educated citizen who is able to fully participate in our society, economy, and democracy. Those trained in the liberal arts are ready for the widest array of career options. Liberal arts education is still about nurturing human freedom by helping people discover and develop their talents. Many of you have at least an implicit understanding that you enrolled at the University of Mississippi to acquire or deepen these areas of knowledge and skills mentioned above. Understandably, many students and parents are focused on preparing for the workforce as the American economy continues the shift towards information age jobs in a dynamic global economy. A liberal arts education is the best preparation for such uncertainty. Better yet, it prepares you for a meaningful life.

Faculty members developed a vision for the liberal arts education that is the basis for every undergraduate degree on campus. Look at the core curriculum and the learning outcomes listed in the Undergraduate Academic Regulations section of the Undergraduate Catalog . There is a common core curriculum of 30 hours of course work that sets the liberal arts foundation for all degrees. And, when combined with the courses in the major and co-curricular learning experiences, the core curriculum should enable students to:

1. study the principal domains of knowledge and their methods of inquiry 2. integrate knowledge from diverse disciplines 3. analyze, synthesize, and evaluate complex and challenging material that stimulates intellectual curiosity, reflection, and capacity for lifelong learning 4. communicate qualitative, quantitative, and technological concepts by effective written, oral, numerical, and graphical means 5. work individually and collaboratively on projects that require the application of knowledge and skill 6. understand a variety of world cultures as well as the richness and complexity of American society 7. realize that knowledge and ability carry with them a responsibility for their constructive and ethical use in society

Students can connect the courses they take with the learning outcomes listed above. Sometimes it is very easy to make the connection due to the title of the course. In other cases students may need to look at the course objectives or description on the syllabus. Now, imagine a web of 100-level through 400- or 500-level courses that connect together to form the undergraduate degree. The connections between these courses are real and come from the above list. Students are not simply “checking off courses” on a degree sheet. They are building an interactive set of skills and content knowledge for a liberal arts education, whether it is for a degree in history, forensic chemistry, social work, or accountancy.

But don’t take my word for the value of a liberal arts education.

Colleges and Employers (NACE) survey of leading executives provides the list of top attributes or skills desired in job candidates. What is the number one skill desired every year? Written communication. See more of the skills listed on the table. These are precisely the skills gained in a liberal arts education.

The 2018 report, Fulfilling the American Dream: Liberal Education and the Future of Work , by the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU) provides a survey of the most valuable experiences desired among college graduates. Responses among executives and hiring managers with over 50% support are shown.

This survey showcases how communication skills, critical thinking, and working with a variety of people are still at the heart of our world needs. And, employers want graduates who have gotten off campus and learned more about “the real world” by being in it. Plan those college experiences, which are part of a liberal arts education, no matter your specific choice of a major.

The University of Mississippi campus is full of opportunities for students to refine their skill set, gain valued experiences, and learn about themselves and the world around them – the essense of a liberal arts education. Faculty members explicitly foster these skills and opportunities. Student services staff members work diligently to help students connect with enrichment opportunities beyond the classroom. Students will get a valuable education at UM and prepare for a rich, meaningful life.

By Holly Reynolds, Associate Dean of Liberal Arts

The Unexpected Value of the Liberal Arts

First-generation students are finding personal and professional fulfillment in the humanities and social sciences.

Growing up in Southern California, Mai-Ling Garcia’s grades were ragged; her long-term plans nonexistent. At age 20, she was living with her in-laws halfway between Los Angeles and the Mojave Desert, while her husband was stationed abroad. Tired of working subsistence jobs, she decided in 2001 to try a few classes at Mount San Jacinto community college.

Nobody pegged her for greatness at first. A psychology professor, Maria Lopez-Moreno recalls Garcia sitting in the midst of a lecture hall, fiddling constantly with a cream-colored scarf. Then something started to catch. After a spirited discussion about the basis for criminal behavior, Lopez-Moreno took this newcomer aside after class and asked: “Why are you here?”

Garcia blurted out a tangled story of marrying a Marine right after high school, seeing him head off to Iraq, and not knowing what to do next. Lopez-Moreno couldn’t walk away. “I said to myself: ‘Uh-oh. I’ve got to suggest something to her.’” At her professor’s urging, Garcia applied for a place in Mt. San Jacinto’s honors program—and began to thrive.

Nourished by smaller classes and motivated peers, Garcia earned straight-A grades for the first time. She emerged as a leader in diversity initiatives, too, drawing on her own multicultural heritage (Filipino and Irish). Shortly before graduation, she won admission to the University of California, Berkeley, campus, where she could pursue a bachelor’s degree.

Today, Garcia is a leading digital strategist for the city of Oakland, California. Rather than rely on an M.B.A. or a technical major, she has capitalized on a seldom-appreciated liberal-arts discipline—sociology—to power her career forward. Now, she describes herself as a “bureaucratic ninja” who doesn’t hide her stormy journey. Instead, she recognizes it as a valuable asset.

“I know what it’s like to be too poor to own a computer,” Garcia told me recently. “I’m the one in meetings who asks: ‘Never mind how well this new app works on an iPhone. Will it run on an old, public-library computer, because that’s the only way some of our residents will get to use it?’”

By its very name, the liberal-arts pathway is tinged with privilege. Blame this on Cicero, the ancient Roman orator, who championed the arts quae libero sunt dignae ( cerebral studies suited for freemen), as opposed to the practical, servile arts suited for lower-class tradespeople. Even today, liberal-arts majors in the humanities and social sciences often are portrayed as pursuing elitist specialties that only affluent, well-connected students can afford.

Look more closely, though, and this old stereotype is starting to crumble. In 2016, the National Association of Colleges and Employers surveyed 5,013 graduating seniors about their family backgrounds and academic paths. The students most likely to major in the humanities or social sciences—33.8 percent of them—were those who were the first generation in their family ever to have earned college degrees. By contrast, students whose parents or other forbears had completed college chose the humanities or social sciences 30.4 percent of the time.

Pursuing the liberal-arts track isn’t a quick path to riches. First-job salaries tend to be lower than what’s available with vocational degrees in fields such as nursing, accounting, or computer science. That’s especially true for first-generation students, who aren’t as likely to enjoy family-aided access to top employers. NACE found that first-generation students on average received post-graduation starting salaries of $43,320, about 12 percent below the pay packages being landed by peers with multiple generations of college experience.

Yet over time, liberal-arts graduates’ earnings often surge, especially for students pursuing advanced degrees. History majors often become well-paid lawyers or judges after completing law degrees, a recent analysis by the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project has found. Many philosophy majors put their analytical and argumentative skills to work on Wall Street. International-relations majors thrive as overseas executives for big corporations, and so on.

For college leaders, the liberal arts’ appeal across the socioeconomic spectrum is both exciting and daunting. As Dan Porterfield, the president of Pennsylvania’s Franklin and Marshall College, points out, first-generation students “may come to college thinking: ‘I want to be a doctor. I want to help people.’ Then they discover anthropology, earth sciences, and many other new fields. They start to fall in love with the idea of being a writer or an entrepreneur. They realize: ‘I just didn’t have a broad enough vision of how to be a difference maker in society.’”

A close look at the career trajectories of liberal-arts graduates highlights five factors—beyond traditional classroom academics—that can spur long-term success for anyone from a non-elite background. Strong support from a faculty mentor is a powerful early propellant. In a survey of about 1,000 college graduates, Richard Detweiler, president of the Great Lakes Colleges Association, found that students who sought out faculty mentors were nearly twice as likely to end up in leadership positions later in life.

Other positive factors include a commitment to keep learning after college; a willingness to move to major U.S. job hubs such as Seattle, Silicon Valley, or the greater Washington, D.C., area; and the audacity to dream big. Finally, students who enter college without well-connected relatives—the sorts who can tell you what classes to take or how to win a choice summer internship—benefit from programs designed to build up professional networks and social capital.

Among the groups offering career-readiness programs on campus is Braven, a nonprofit founded by Aimée Eubanks Davis, a former Teach for America executive. Making its debut in 2014, Braven already has reached about 1,000 students at Rutgers University-Newark in New Jersey and San Jose State University in California. Expansion into the Midwest is on tap. Braven mixes students majoring in the liberal arts and those pursuing vocational degrees in each cohort, the theory being that all can learn from one another.

One of Braven’s Newark enrollees in 2015 was Dyllan Brown-Bramble, a transfer student earning strong grades in psychology, who didn’t feel at all connected to the New Jersey campus. Commuting from his parents’ home, he usually arrived at Rutgers just a few minutes before 10 a.m. classes started. Once afternoon courses were done, he’d retreat to Parking Lot B and rev up his 2003 Sentra. By 3:50 p.m., he’d be gone.

Brown-Bramble’s parents are immigrants from Dominica. His father runs a small construction business; his mother, a Baruch College graduate, manages a tourism office. Privately, the Rutgers student is quite proud of them, but it seemed pointless to explain his Caribbean origins to strangers. They typically reacted inappropriately. Some imagined him to be the son of dirt-poor refugees struggling to rise above a shabby past. Others assumed he was a world-class genius: “an astrophysicist who could fly.” There wasn’t any room for him to be himself.

When Brown-Bramble encountered a campus flier urging students to enroll in small evening workshops called the Braven Career Accelerator, he took the bait. “I knew I was supposed to be networking in college,” he later told me. “I thought: Okay, here’s a chance to do something.”

Suddenly, Rutgers became more compelling. For nine weeks, Brown-Bramble and four other students of color became evening allies. They met in an empty classroom each Tuesday at six to construct LinkedIn profiles and practice mock interviews. They picked up tips about local internships, aided by a volunteer coach whose life and background was much like theirs. They united as a group, discussing each person’s weekly highs and lows while encouraging one another to keep trying for internships and better grades. “We had a saying,” Brown-Bramble recalled. “If one of us succeeds, all of us succeed.”

Most of the volunteer coaches came from minority backgrounds, too. Among them: Josmar Tejeda, who had graduated from the New Jersey Institute of Technology five years earlier with an architecture degree. Since graduating, Tejeda had worked at everything from social-media jobs to being an asbestos inspector. As the coach for Brown-Bramble’s group, Tejeda combined relentless optimism with an acknowledgment that getting ahead wasn’t easy.

“Keep it real,” Tejeda kept telling his students as they talked through case studies and their own goals. Everyone did so. That feeling of being the only black or Latino person in the room? The awkwardness of always being asked: Where are you from? The strains of always trying to be the “model minority”? Familiar territory for everyone.

“It was liberating,” Brown-Bramble told me. Surrounded by sympathetic peers, Brown-Bramble discovered new ways to share his heritage in job interviews. Yes, some of his Caribbean relatives had arrived in the United States not knowing how to fill out government forms. As a boy, he had needed to help them. But that was all right. In fact, it was a hidden strength. “I could create a culture story that worked for me,” Brown-Bramble said. “I can relate to people with different backgrounds. There’s nothing about me that I have to rise above.”

This summer, with the support of Inroads , a nonprofit that promotes workforce diversity, Brown-Bramble is interning in the compliance department of Novo Nordisk, a pharmaceutical maker. Riding the strength of a 3.8 grade-point average, he plans to get a law degree and work in a corporate setting for a few years to pay off his student loans. Then he hopes to set up his own law firm, specializing in start-up formation. “I’d like to help other entrepreneurs do things in Newark,” he told me.

Organizations like Braven draw on “the power of the cohort,” said Shirley Collado, the president of Ithaca College and a former top administrator at Rutgers-Newark. When students settle into small groups with trustworthy peers, she explained, candor takes hold. The sterile dynamic of large lectures and solo homework assignments gives way to a motivation-boosting alliance among seat mates and coaches. “You build social capital where it didn’t exist before,” Collado said.

For Mai-Ling Garcia, the leap from community college to Berkeley was perilous. Arriving at the famous university’s campus, she and her then-husband were so short on cash that they subsisted most days on bowls of ramen. Scraping by on partial scholarships, neither knew how to get the maximum available financial aid. To cover expenses, Garcia took a part-time job teaching art at a grade-school recreation center in Oakland.

Finishing college can become impossible in such circumstances. During her second semester, Garcia began tracking down what she now refers to as “a series of odd little foundations with funky scholarships.” People wanted to help her. Before long, she was attending Berkeley on a full ride. Her money problems abated. What she couldn’t forget was that initial feeling of being in trouble and ill-prepared. Her travails were pulling her into sociology’s most pressing issues: how vulnerable people fare in a world they don’t understand, and what can be done to improve their lives.

Simultaneously, Berkeley’s professors were arming Garcia with tools that would define her career. She spent a year learning the fine points of ethnography from a Vietnam-era Marine, Martin Sanchez-Jankowski, who taught students how to conduct field research. He sent Garcia into the Oakland courthouse to watch judges in action, advising her to heed the ways racial differences tinged courtroom conduct. She learned to take careful notes, to be explicit about her theories and assumptions, and to operate with a rigor that could withstand peer-review scrutiny. Her professors would stay in academia; she was being trained to have an impact in the wider world.

What can one do with a sociology degree? Garcia tried a lot of different jobs in her first few years after graduation. She spent two years at a nonprofit trying to untangle Veterans Administration bureaucracy. After that, she dedicated three years to a position at the Department of Labor, winning many small battles related to veterans’ employment. She had found job security, but she couldn’t shake the feeling that a technology revolution was racing through the private sector—and leaving government far behind.

Companies like Lyft, Airbnb, and Instagram were putting new powers in the public’s hands, giving them handy tools to hail a ride, find lodging, or share photos. By comparison, trying to change a jury-duty date remained a clumsy slog through outdated websites. Instead of bemoaning this tech gap, Garcia decided to gain vital tech skills herself. She signed up for evening classes in digital marketing and refined that knowledge during an 18-month stint at a startup. Then she began hunting for a government job with impact.

In 2014, Garcia joined the City of Oakland as a bridge builder who could amp up online government services on behalf of the city’s 400,000 residents. This wasn’t just an exercise in technology upgrading; it required a fundamental rethinking of the way that Oakland delivered services. Buffers between city workers and an impatient public would come down. The social structures of power would change. To make this transition, it helped to have a digitally savvy sociologist in the house.

Over coffee one afternoon, Garcia told me excitedly about the progress that she and the city communications manager were achieving with their initiative. If street-art creators want more recognition for their work, Garcia can drum up interest on social media. If garbage is piling up, new digital tools let citizens visit the city’s Facebook page and summon services within seconds.

Looking ahead, Garcia envisions a day when landing a municipal job becomes vastly easier, with cities’ Twitter feeds posting each new opening. Other aspects of digital technology ought to help residents connect quickly with whatever part of government matters to them—whether that means signing up for summer camp or giving the mayor a piece of one’s mind.

Related Video

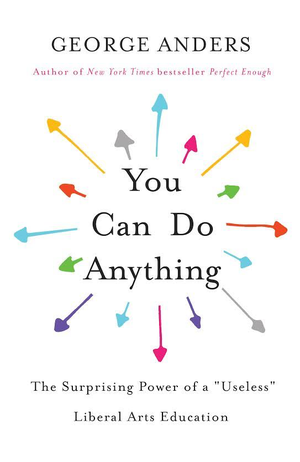

This article has been adapted from George Anders’s new book, You Can Do Anything.

About the Author

American Academy for Liberal Education

Advancing Excellence in Liberal Education

What is Liberal Education?

The American Academy for Liberal Education (AALE) welcomes readers to its on-line resource, What is Liberal Education? , a collection of essays and commentaries on topics of interest pertaining to the value and practice of liberal education and addressing the question: What is liberal education?

Current Topic: Liberal Education and the K-12 Curriculum

Jacques Barzun. “Why We Educate the Way We Do”

Jacques Barzun (1907-2012), one of the founders of the American Academy for Liberal Education, is recognized internationally as one of the most thoughtful commentators on the cultural history of the modern period. After receiving his PhD from Columbia University (NY) in 1932, Barzun was appointed to the history faculty. During his tenure at Columbia, he served as Dean of Faculties and as Provost. He was granted the title of University Professor in 1967.

Barzun is the author of over 30 books and countless essays on historical, cultural and educational topics. Among his writings are Critical Questions (a collection of essays 1940-1980), The Use and Abuse of Art (1974), and From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Life. 1500 to the Present (2000). The American Scholar called From Dawn to Decadence a “masterwork” by a “man whose entire life has been spent acquiring the perspective that only wisdom, and not mere knowledge, can grant.” His works on education include Teacher in America (1945) and The American University: How it Runs and Where it is Going (new ed. 1993). Barzun’s professional activities included membership in the American Philosophical Society, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Royal Society of Arts. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2003.

Jacquez Barzun was interviewed by Ruth Wattenburg of the American Educator in 2002 on the subjects that form a K-12 education. The interview is reproduced here with permission from the Fall 2002 issue of American Educator , the quarterly journal of the American Federation of Teachers, AFL-CIO, under its original title: Why We Educate the Way We Do .

The Power and Promise of the Liberal Arts

Illustration by Simon Pemberton

What is the value of a liberal arts education? From the public to the press to the U.S. president, the quality of university education is a burning issue.

The challenge can be seen in the falling numbers of liberal arts majors. Today, nationally, the liberal arts account for less than 30 percent of degrees awarded, a sharp drop from the 1970s. The Carnegie report, “Liberal Arts Education for a Global Society,” indicates that the benefits of a liberal arts education are no longer self-evident outside academe. The liberal arts find it particularly difficult to attract first-generation and foreign students, and students of color. In the meantime, independent liberal arts colleges are closing or adding vocational schools to survive.

We cannot ignore the challenge. We have an ethical responsibility to provide the best education we can and to continuously reflect on how we do so. Failure to do so invites external interventions that might not be in the best interests of our educational enterprise.

Ironically, what may be helpful is the accountability movement — the strident calls for quality education from the public, parents, pundits and politicians, whose model continues to be the small liberal arts college. Liberal arts educational practices are being replicated across universities through the establishment of learning communities, living and learning centers, honors colleges, and first-year seminars.

The rapid changes taking place in the world of work require flexible, transferable skills. This is what the liberal arts do best: They teach students to learn continuously, think critically and confront new challenges creatively. As one-career lifetimes disappear for most people, the knowledge, skills and literacies of the liberal arts will become even more important. Not surprisingly, surveys show business executives tend to have great confidence in the value of a liberal arts education, more so than parents.

I see the liberal arts resting on four interconnected values: intrinsic, intellectual, instrumental and idealistic. The power and promise of the liberal arts lies in the multidimensionality and mutuality of these values.

The intrinsic value of a liberal arts education lies in the sheer joy of learning for its own sake, asking the big questions, making discoveries, cultivating a life-long quest for learning. The liberal arts explore and engage the profound issues facing humanity, our enduring individual and collective searches for meaning and belonging, the moral, metaphysical and material dimensions of our existence.

The intellectual value is embodied in the capaciousness and versatility of the liberal arts, the richness of their content, the treasure of knowledge in the liberal arts disciplines and interdisciplines. Students are exposed to various fields, foci, and methodologies in the humanities, social sciences and natural sciences, as well as to vast repertoires of human experience, thought, creativity and invention that are both enlightening and liberating.

The liberal arts also have instrumental value. They cultivate invaluable skills and capacities for the world of work including verbal and written communication skills, critical thinking skills, and creative sensibilities. They foster breadth and adaptability to contexts, as well as sensitivity to human difference and commonality.

Finally, the liberal arts have idealistic value in their contribution to character development. They can deepen and expand students’ sensibilities and emotional richness, ethical reasoning, and capacity for empathy. The liberal arts often cultivate students’ moral and narrative imaginations, which is critical for responsible citizenship and leadership.

Through the liberal arts, we develop the capacity to commit to something greater than our individual selves as we grasp the complexities and connectedness of the human condition. There is no doubt the world needs technically skilled workers and professionals, but, in the words of the Carnegie report, there may even be a “greater need for liberally educated citizens and human beings who can distinguish between good from evil, justice from injustice, what is noble and beautiful from what is base and degrading.” Technological progress without ethical values produces the grotesque barbarisms that littered the 20th century, the most materially advanced century in history.

The liberal arts, which have been with us since the modern university emerged and can be traced back to the ancient universities in Europe, Africa and Asia, have a long future so long as the human need to understand ourselves, the natural world and the spiritual dimension exist.

Paul Tiyambe Zeleza is Presidential Professor of African American Studies and History and dean of the Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts.

The lasting value of a classical liberal arts education

Editor’s note: This essay is a response to Jason Gaulden’s Flypaper article, “ America’s anachronistic education system ,” as well as Education Week ’s recent Special Report, “ Schools and the Future of Work .”

Within the last week, Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak announced the founding of “Woz U,” a digital institute designed to inspire the next generation of innovators. The CEO of Google, Sundar Pichai, also proclaimed that the tech giant will invest $1 billion over the next five years to remediate what he sees as an alarming disconnect between how college graduates are prepared and what the job market actually requires. "The nature of work is fundamentally changing,” Pichai said, “and that is shifting the link between education, training, and opportunity. One-third of jobs in 2020 will require skills that aren't common today. It's a big problem."

The tech gods have spoken and are aligned: Our country faces a crisis in educating our children to meet an increasingly complex world. Where does this disconnect leave us educators? We need to develop our graduates’ skills and talents for an evolving twenty-first-century economy, but the goalposts have shifted away from the aim of our current schools, and it is hard to know where to start. What hope do we educators have to design a curriculum, program, and school culture that will actually matter for our students?

We can best do this by returning to a timeless and always applicable approach: a classical liberal arts education.

Before you dismiss this idea as nostalgic blowback, consider that the best hedge against the vicissitudes of fortune will always be the permanent: clear thinking, wisdom, and character, which a classical education is ideally structured to inculcate as a foundation for life-long learning. Indeed, we can’t know what and where jobs will be a few years from now, but history and human nature tell us that thoughtful leadership will be required. In every age of uncertainty, we should double down on the enduring ends of a classical education—the ability to deliberate carefully, see multiple sides of an issue, and exercise sound and decisive judgment. We sometimes call this critical thinking, but the ancients called it wisdom.

At Great Hearts, the classical charter school network I co-founded, we seek to develop wisdom in pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty. The medium of this pursuit is earnest conversation regarding, as Matthew Arnold said, “the best that has been thought and said.” All of our high school students have at the center of their day a two-hour Socratic conversation on works of great literature, philosophy, art, and history. Socratic pedagogy is deployed in all subjects, from music to physics.

In these spaces, students use the ideas of great authors, artists, and scientists of the past to understand classmates’ perceptions and premises by asking respectful, relevant questions. They learn to acknowledge ambiguity, respect disagreement, accept doubt, and allow for multiple interpretations to coexist. They escape the tyranny of the present, as well as their own emotions and concerns. And they imagine the permanent aspects of the human condition, both good and bad, and ponder what has been, what is, and what might be possible.

Every generation faces essential questions—and they skip them at their own peril. What does it mean to be a human being? How does a specific idea, pursuit, or product relate to human happiness? What is justice? What is my duty to myself and others? How does one balance freedom with responsibility? These are not coffee shop queries, but first order questions that are more important than ever in the twenty-first century. And a mind and soul well trained to pursue and answer them—and use this training practically in the workplace—will be ready to innovate and effect change for the greater good.

Unfortunately, too much of education today is focused on standardized tests, getting kids into college, and careerism before one’s career. Some of this is understandable; we want students to think ahead and strive to big goals. But many students are tracked without any consideration of their work’s purpose and inherent nobility, and with little concern for the professions in which their unique talents can be useful. A classical liberal arts education, however, instills in young people the joy of learning for learning’s sake, and helps them discover what makes them happy: the link between their character and unique talents, their calling. And when we are happy and grounded, we are more useful to ourselves and others, no matter what life brings our way.

It’s true, of course, that not every graduate is destined for Silicon Valley or an executive suite. We need craftsmen, tradeswomen, and soldiers. But they too deserve a classical liberal arts education. And they ought to be just as well educated as those in boardrooms and ivory towers. Indeed, American democracy, freedom, and ingenuity depend on poet-warriors and philosopher-technicians. This is why we believe at Great Hearts that all of our public school students should receive a classical liberal arts education before they go on to a profession or pick a major in college.

These, moreover, aren’t just my sentiments. There’s a growing body of research that a classical liberal arts education is not some ivy-covered relic and detour to a useless past, but an increasingly important part of the present and future. George Anders and Randall Stross, for example, both argued in recent books that the emotional intelligence, interpretive capacity, and problem-solving skills enabled by a liberal arts education set graduates of these programs apart from their non-program peers. And in The Age of Agility: Education Pathways for the Future of Work , Jason Gaulden and Alan Gottlieb argue that four capacities will emerge as more and more vital in the decades ahead: the ability to abstract deeper meaning; the self-awareness and empathy to have probing conversations with those from different backgrounds; the ability to intuit novel thinking in fluid environments; and the ability to write and codify processes under a desired outcome. While Gaulden and Gottlieb don’t expressly make the connection, these capacities sound like the cumulative outcomes of any classical liberal arts education worth its salt.

Tim Cook, CEO of Apple, said in his commencement address at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology this past spring: “I’m more concerned about people thinking like computers without values or compassion or concern for the consequences…That is what we need you to help us guard against. Because if science is a search in the darkness, then the humanities are a candle that shows us where we have been and the danger that lies ahead.”

I hope that in the age of expediency we don’t forget the great value of slowing down, of deep reflection and conversation, and of living in community in the shared search for truth and meaning. Abraham Lincoln said “the best thing about the future is that it comes one day at a time.” When it comes to schooling, trying to predict the future and rush towards it only diminishes the present. The one thing we do know about the future of work is that a well-stocked mind and well-nurtured soul will be the best provisions for the uncertain journey ahead.

Dan Scoggin is the co-founder and chief advancement officer of Great Hearts, serving 15,000 K–12 scholars in Arizona and Texas and growing nationally.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Longshoremen on their lunch hour at the San Francisco docks. Photo courtesy the Library of Congress

Do liberal arts liberate?

In jack london’s novel, martin eden personifies debates still raging over the role and purpose of education in american life.

by Nick Romeo + BIO

As Jack London’s most autobiographical novel begins, its hero, a poor young sailor named Martin Eden, has just gotten into a brawl. Noticing a gang of drunken hoodlums about to assault an upper-class young man, Martin scatters them with blows that leave his knuckles raw. To show his gratitude, the man invites Martin for a meal at the family home. While his host is helpless in a fight, Martin is intimidated by the refined atmosphere of a dinner party. He has seen distant ports and peoples, but this rarefied realm of books and music is perhaps the most exotic place he has ever visited. London describes him literally lurching about the dining room, as if tossed by rough seas.

Martin’s disorientation deepens once he meets Ruth Morse, the beautiful sister of his host who speaks knowledgeably about Victorian poets such as A C Swinburne and Robert Browning. When he learns that she studies at the University of California in Berkeley, he feels that ‘she had become remoter from him by at least a million miles.’ Looking at the gleaming forks and knives beside his plate, Martin recalls his meals with sailors: ‘eating salt beef with sheath-knives and fingers, or scooping thick pea-soup out of pannikins by means of battered iron spoons … to the accompaniment of creaking timbers and … loud mouth-noises of the eaters.’ Ruth uses words he has never heard with a casual ease, while his own language is full of coarse slang. After venturing into a conversation about poetry, he admits: ‘I guess the real facts is that I don’t know nothin’ much about such things.’

Unemployed men sitting on the sunny side of the San Francisco Public Library, February 1937. Photo by Dorothea Lange/Library of Congress

After meeting Ruth, Martin still must earn a living, but he begins haunting the free libraries of Oakland and Berkeley, sleeping only five hours a night, and devouring books on algebra, history, sociology, physics and poetry. This fanatical pursuit of knowledge – both as an end in itself and as a means to class mobility – anchors London’s exploration of the functions of education in American life. First published in 1909, Martin Eden is a narrative intervention in debates still raging over the purpose of the liberal arts and education. Should students be able to study subjects like Chinese, Greek or mathematics just because they find them interesting? What does a society lose when only the prosperous can study the liberal arts, and what does an individual gain by pursuing knowledge for its own sake? If the liberal arts often function as an ornament for the wealthy, can they still, as their name suggests, liberate people from all backgrounds?

W hen Martin launches into a manic course of self-study after falling for Ruth, he’s using his mind as a tool to gain wealth and status. He wants to become worthy of her, and by the standards of her family and milieu, this means he must improve his grammar and his income. But he is soon seduced by the intrinsic fascination and beauty of what he is learning. Martin sees awe-inspiring intellectual vistas, and London’s radiant portrait of his hero’s intellectual awakening is a powerful defence of the value of liberal study for its own sake. As the novel begins, Martin is a heavy drinker, a trait he shares with London. Once he begins reading seriously, his need for strong drink vanishes. ‘He was drunken in new and more profound ways,’ London writes. Books have become a source of lasting intoxication, a way of permanently enchanting the world. This vision of learning as a kind of sustainable drinking captures two important ideas: the deep pleasure of study for its own sake, and its consciousness-shifting possibilities.

Some of London’s other provocative metaphors refine this case for the liberating potential of education. One comes from the perspective of Ruth, who thinks, as she beholds Martin at the opening dinner party, that his badly fitting clothes, weathered hands and sunburned face are just the ‘prison-bars through which she saw a great soul looking forth, inarticulate and dumb because of those feeble lips that would not give it speech.’ At one level, this is pure class snobbery: if only Martin had a tailored suit, delicate hands, and a face not tanned by hard labour under the sun, he might be marriageable. Yet Ruth also suggests that the power of language could free him from the prison of his inarticulate state. There’s a crucial subtlety here that contemporary debates often miss: the history of the study of liberal arts has no shortage of elitism and exclusion, yet this historical fact does not undermine the philosophical claim for their liberating power . Ruth is wrong to scorn Martin because of his poverty; she is right that an education could transform him.

London has Martin himself endorse the same notion. Reflecting on great writers and poets, Martin thinks: ‘Dogs asleep in the sun often whined and barked, but they were unable to tell what they saw that made them whine and bark … And that was all he was, a dog asleep in the sun.’ Through education, he will gain a radical power to express his thoughts and feelings, transcending the inarticulate whines of his old self. Gaining this power will likely bring practical benefits – wealth, social status, expanded romantic options – but these pale compared with the value of articulating what would otherwise remain imprisoned in the self. This metaphor presents the self as a static given – education upgrades one’s expressive power, but it doesn’t restructure the self. Is Martin just becoming a speaking dog, or is he gaining the interests, dispositions and capacities of a more complex being, one more human than canine?

Education is a form of lasting intoxication and a sedentary voyage through space and time