Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

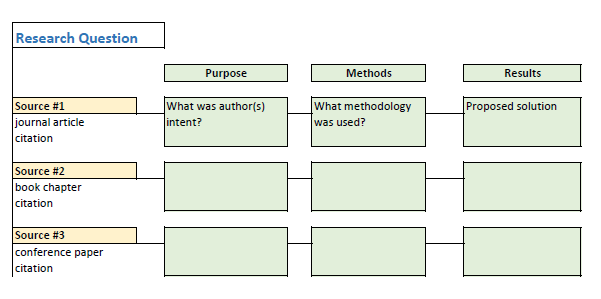

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Citation Styles

- Chicago Style

- Annotated Bibliographies

What is a Lit Review?

How to write a lit review.

- Video Introduction to Lit Reviews

Main Objectives

Examples of lit reviews, additional resources.

- Zotero (Citation Management)

What is a literature review?

- Either a complete piece of writing unto itself or a section of a larger piece of writing like a book or article

- A thorough and critical look at the information and perspectives that other experts and scholars have written about a specific topic

- A way to give historical perspective on an issue and show how other researchers have addressed a problem

- An analysis of sources based on your own perspective on the topic

- Based on the most pertinent and significant research conducted in the field, both new and old

- A descriptive list or collection of summaries of other research without synthesis or analysis

- An annotated bibliography

- A literary review (a brief, critical discussion about the merits and weaknesses of a literary work such as a play, novel or a book of poems)

- Exhaustive; the objective is not to list as many relevant books, articles, reports as possible

- To convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic

- To explain what the strengths and weaknesses of that knowledge and those ideas might be

- To learn how others have defined and measured key concepts

- To keep the writer/reader up to date with current developments and historical trends in a particular field or discipline

- To establish context for the argument explored in the rest of a paper

- To provide evidence that may be used to support your own findings

- To demonstrate your understanding and your ability to critically evaluate research in the field

- To suggest previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, and quantitative and qualitative strategies

- To identify gaps in previous studies and flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches in order to avoid replication of mistakes

- To help the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research

- To suggest unexplored populations

- To determine whether past studies agree or disagree and identify strengths and weaknesses on both sides of a controversy in the literature

- Choose a topic that is interesting to you; this makes the research and writing process more enjoyable and rewarding.

- For a literature review, you'll also want to make sure that the topic you choose is one that other researchers have explored before so that you'll be able to find plenty of relevant sources to review.

- Your research doesn't need to be exhaustive. Pay careful attention to bibliographies. Focus on the most frequently cited literature about your topic and literature from the best known scholars in your field. Ask yourself: "Does this source make a significant contribution to the understanding of my topic?"

- Reading other literature reviews from your field may help you get ideas for themes to look for in your research. You can usually find some of these through the library databases by adding literature review as a keyword in your search.

- Start with the most recent publications and work backwards. This way, you ensure you have the most current information, and it becomes easier to identify the most seminal earlier sources by reviewing the material that current researchers are citing.

The organization of your lit review should be determined based on what you'd like to highlight from your research. Here are a few suggestions:

- Chronology : Discuss literature in chronological order of its writing/publication to demonstrate a change in trends over time or to detail a history of controversy in the field or of developments in the understanding of your topic.

- Theme: Group your sources by subject or theme to show the variety of angles from which your topic has been studied. This works well if, for example, your goal is to identify an angle or subtopic that has so far been overlooked by researchers.

- Methodology: Grouping your sources by methodology (for example, dividing the literature into qualitative vs. quantitative studies or grouping sources according to the populations studied) is useful for illustrating an overlooked population, an unused or underused methodology, or a flawed experimental technique.

- Be selective. Highlight only the most important and relevant points from a source in your review.

- Use quotes sparingly. Short quotes can help to emphasize a point, but thorough analysis of language from each source is generally unnecessary in a literature review.

- Synthesize your sources. Your goal is not to make a list of summaries of each source but to show how the sources relate to one another and to your own work.

- Make sure that your own voice and perspective remains front and center. Don't rely too heavily on summary or paraphrasing. For each source, draw a conclusion about how it relates to your own work or to the other literature on your topic.

- Be objective. When you identify a disagreement in the literature, be sure to represent both sides. Don't exclude a source simply on the basis that it does not support your own research hypothesis.

- At the end of your lit review, make suggestions for future research. What subjects, populations, methodologies, or theoretical lenses warrant further exploration? What common flaws or biases did you identify that could be corrected in future studies?

- Double check that you've correctly cited each of the sources you've used in the citation style requested by your professor (APA, MLA, etc.) and that your lit review is formatted according to the guidelines for that style.

Your literature review should:

- Be focused on and organized around your topic.

- Synthesize your research into a summary of what is and is not known about your topic.

- Identify any gaps or areas of controversy in the literature related to your topic.

- Suggest questions that require further research.

- Have your voice and perspective at the forefront rather than merely summarizing others' work.

- Cyberbullying: How Physical Intimidation Influences the Way People are Bullied

- Use of Propofol and Emergence Agitation in Children

- Eternity and Immortality in Spinoza's 'Ethics'

- Literature Review Tutorials and Samples - Wilson Library at University of La Verne

- Literature Reviews: Introduction - University Library at Georgia State

- Literature Reviews - The Writing Center at UNC Chapel Hill

- Writing a Literature Review - Boston College Libraries

- Write a Literature Review - University Library at UC Santa Cruz

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliographies

- Next: Zotero (Citation Management) >>

- Last Updated: Aug 28, 2024 12:27 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.elac.edu/Citation

Boatwright Memorial Library

- Chicago/Turabian

- AP (Associated Press)

- APSA (Political Science)

- ASA & AAA (Soc/Ant)

- ACS (Chemistry)

- Harvard Style

- SBL (Society of Biblical Literature)

- EndNote Web

- Help Resources

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Literature Reviews

- Citation exercises This link opens in a new window

What is a Literature Review?

The literature review is a written explanation by you, the author, of the research already done on the topic, question or issue at hand. What do we know (or not know) about this issue/topic/question?

- A literature review provides a thorough background of the topic by giving your reader a guided overview of major findings and current gaps in what is known so far about the topic.

- The literature review is not a list (like an annotated bibliography) -- it is a narrative helping your reader understand the topic and where you will "stand" in the debate between scholars regarding the interpretation of meaning and understanding why things happen. Your literature review helps your reader start to see the "camps" or "sides" within a debate, plus who studies the topic and their arguments.

- A good literature review should help the reader sense how you will answer your research question and should highlight the preceding arguments and evidence you think are most helpful in moving the topic forward.

- The purpose of the literature review is to dive into the existing debates on the topic to learn about the various schools of thought and arguments, using your research question as an anchor. If you find something that doesn't help answer your question, you don't have to read (or include) it. That's the power of the question format: it helps you filter what to read and include in your literature review, and what to ignore.

How Do I Start?

Essentially you will need to:

- Identify and evaluate relevant literature (books, journal articles, etc.) on your topic/question.

- Figure out how to classify what you've gathered. You could do this by schools of thought, different answers to a question, the authors' disciplinary approaches, the research methods used, or many other ways.

- Use those groupings to craft a narrative, or story, about the relevant literature on this topic.

- Remember to cite your sources properly!

- Research: Getting Started Visit this guide to learn more about finding and evaluating resources.

- Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources (IUPUI Writing Center) An in-depth guide on organizing and synthesizing what you've read into a literature review.

- Guide to Using a Synthesis Matrix (NCSU Writing and Speaking Tutorial Service) Overview of using a tool called a Synthesis Matrix to organize your literature review.

- Synthesis Matrix Template (VCU Libraries) A word document from VCU Libraries that will help you create your own Synthesis Matrix.

Literature Reviews: Overview

This video from NCSU Libraries gives a helpful overview of literature reviews. Even though it says it's "for graduate students," the principles are the same for undergraduate students too!

Literature Review Examples

Reading a Scholarly Article

- Reading a Scholarly Article or Literature Review Highlights sections of a scholarly article to identify structure of a literature review.

- Anatomy of a Scholarly Article (NCSU Libraries) Interactive tutorial that describes parts of a scholarly article typical of a Sciences or Social Sciences research article.

- Evaluating Information | Reading a Scholarly Article (Brown University Library) Provides examples and tips across disciplines for reading academic articles.

- Reading Academic Articles for Research [LIBRE Project] Gabriel Winer & Elizabeth Wadell (ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI))

Additional Tutorials and Resources

- UR Writer's Web: Using Sources Guidance from the UR Writing Center on how to effectively use sources in your writing (which is what you're doing in your literature review!).

- Write a Literature Review (VCU Libraries) "Lit Reviews 101" with links to helpful tools and resources, including powerpoint slides from a literature review workshop.

- Literature Reviews (UNC Writing Center) Overview of the literature review process, including examples of different ways to organize a lit review.

- “Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review.” Pautasso, Marco. “Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review.” PLOS Computational Biology, vol. 9, no. 7, July 2013, p. e1003149.

- Writing the Literature Review Part I (University of Maryland University College) Video that explains more about what a literature review is and is not. Run time: 5:21.

- Writing the Literature Review Part II (University of Maryland University College) Video about organizing your sources and the writing process. Run time: 7:40.

- Writing a Literature Review (OWL @ Purdue)

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliographies

- Next: Citation exercises >>

- Library Accounts

Writing a Literature Review

About this guide, what is a literature review, trials and tribulations of writing.

- Planning a review

- Exploring the Literature

- Managing the Review

- Organizing and writing the review

Science Librarian

The guide instructs students on how to write the literature review in scientific research papers. It illustrates the principles and practices that enable students to write a cogent and relevant literature review that frames their research study in terms of structure, scope and content. Using steps delineated in this guide illustrates to the researcher the process of writing a literature review. It allows the reader, when reading the review, to understand the justification for the research study as supported through the literature..

The process of writing a literature review encompasses four phases:

1. P lanning the Review. Provides a strategic roadmap for the writing process.

2. Exploring the Literature. Searching the literature for relevant sources for addition into their review.

3. Managing the Literature. Compiling and evaluating relevant sources for inclusion into the review.

4. Organizing and Writing the Review. Involves outlining and writing the literature review.

A literature review surveys the scholarly literature for relevant sources that address the scope of a research topic. Neither an annotated bibliography, nor a systematic review, it lays the groundwork for justification of the research study by identifying the research problem, formulating the study’s research questions, and defining the objectives of the study.

There are two types of literature reviews. The first type, article literature review, provides a comprehensive coverage of a research topic, problem or area of interest. The second type is a chapter embedded within a research article, which cites relevant literature sources that support the research study findings and discussion. This libguide focuses on how to write a literature review for a research article.

- Next: Planning a review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2023 4:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.unlv.edu/LiteratureReview

- Special Collections

- Architecture Library

- Medical Library

- Music Library

- Teacher Library

- Law Library

How to Write a Literature Review

What is a literature review.

- What Is the Literature

- Writing the Review

A literature review is much more than an annotated bibliography or a list of separate reviews of articles and books. It is a critical, analytical summary and synthesis of the current knowledge of a topic. Thus it should compare and relate different theories, findings, etc, rather than just summarize them individually. In addition, it should have a particular focus or theme to organize the review. It does not have to be an exhaustive account of everything published on the topic, but it should discuss all the significant academic literature and other relevant sources important for that focus.

This is meant to be a general guide to writing a literature review: ways to structure one, what to include, how it supplements other research. For more specific help on writing a review, and especially for help on finding the literature to review, sign up for a Personal Research Session .

The specific organization of a literature review depends on the type and purpose of the review, as well as on the specific field or topic being reviewed. But in general, it is a relatively brief but thorough exploration of past and current work on a topic. Rather than a chronological listing of previous work, though, literature reviews are usually organized thematically, such as different theoretical approaches, methodologies, or specific issues or concepts involved in the topic. A thematic organization makes it much easier to examine contrasting perspectives, theoretical approaches, methodologies, findings, etc, and to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of, and point out any gaps in, previous research. And this is the heart of what a literature review is about. A literature review may offer new interpretations, theoretical approaches, or other ideas; if it is part of a research proposal or report it should demonstrate the relationship of the proposed or reported research to others' work; but whatever else it does, it must provide a critical overview of the current state of research efforts.

Literature reviews are common and very important in the sciences and social sciences. They are less common and have a less important role in the humanities, but they do have a place, especially stand-alone reviews.

Types of Literature Reviews

There are different types of literature reviews, and different purposes for writing a review, but the most common are:

- Stand-alone literature review articles . These provide an overview and analysis of the current state of research on a topic or question. The goal is to evaluate and compare previous research on a topic to provide an analysis of what is currently known, and also to reveal controversies, weaknesses, and gaps in current work, thus pointing to directions for future research. You can find examples published in any number of academic journals, but there is a series of Annual Reviews of *Subject* which are specifically devoted to literature review articles. Writing a stand-alone review is often an effective way to get a good handle on a topic and to develop ideas for your own research program. For example, contrasting theoretical approaches or conflicting interpretations of findings can be the basis of your research project: can you find evidence supporting one interpretation against another, or can you propose an alternative interpretation that overcomes their limitations?

- Part of a research proposal . This could be a proposal for a PhD dissertation, a senior thesis, or a class project. It could also be a submission for a grant. The literature review, by pointing out the current issues and questions concerning a topic, is a crucial part of demonstrating how your proposed research will contribute to the field, and thus of convincing your thesis committee to allow you to pursue the topic of your interest or a funding agency to pay for your research efforts.

- Part of a research report . When you finish your research and write your thesis or paper to present your findings, it should include a literature review to provide the context to which your work is a contribution. Your report, in addition to detailing the methods, results, etc. of your research, should show how your work relates to others' work.

A literature review for a research report is often a revision of the review for a research proposal, which can be a revision of a stand-alone review. Each revision should be a fairly extensive revision. With the increased knowledge of and experience in the topic as you proceed, your understanding of the topic will increase. Thus, you will be in a better position to analyze and critique the literature. In addition, your focus will change as you proceed in your research. Some areas of the literature you initially reviewed will be marginal or irrelevant for your eventual research, and you will need to explore other areas more thoroughly.

Examples of Literature Reviews

See the series of Annual Reviews of *Subject* which are specifically devoted to literature review articles to find many examples of stand-alone literature reviews in the biomedical, physical, and social sciences.

Research report articles vary in how they are organized, but a common general structure is to have sections such as:

- Abstract - Brief summary of the contents of the article

- Introduction - A explanation of the purpose of the study, a statement of the research question(s) the study intends to address

- Literature review - A critical assessment of the work done so far on this topic, to show how the current study relates to what has already been done

- Methods - How the study was carried out (e.g. instruments or equipment, procedures, methods to gather and analyze data)

- Results - What was found in the course of the study

- Discussion - What do the results mean

- Conclusion - State the conclusions and implications of the results, and discuss how it relates to the work reviewed in the literature review; also, point to directions for further work in the area

Here are some articles that illustrate variations on this theme. There is no need to read the entire articles (unless the contents interest you); just quickly browse through to see the sections, and see how each section is introduced and what is contained in them.

The Determinants of Undergraduate Grade Point Average: The Relative Importance of Family Background, High School Resources, and Peer Group Effects , in The Journal of Human Resources , v. 34 no. 2 (Spring 1999), p. 268-293.

This article has a standard breakdown of sections:

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Some discussion sections

First Encounters of the Bureaucratic Kind: Early Freshman Experiences with a Campus Bureaucracy , in The Journal of Higher Education , v. 67 no. 6 (Nov-Dec 1996), p. 660-691.

This one does not have a section specifically labeled as a "literature review" or "review of the literature," but the first few sections cite a long list of other sources discussing previous research in the area before the authors present their own study they are reporting.

- Next: What Is the Literature >>

- Last Updated: Jan 11, 2024 9:48 AM

- URL: https://libguides.wesleyan.edu/litreview

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Clinics (Sao Paulo)

Approaching literature review for academic purposes: The Literature Review Checklist

Debora f.b. leite.

I Departamento de Ginecologia e Obstetricia, Faculdade de Ciencias Medicas, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP, BR

II Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Pernambuco, PE, BR

III Hospital das Clinicas, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Pernambuco, PE, BR

Maria Auxiliadora Soares Padilha

Jose g. cecatti.

A sophisticated literature review (LR) can result in a robust dissertation/thesis by scrutinizing the main problem examined by the academic study; anticipating research hypotheses, methods and results; and maintaining the interest of the audience in how the dissertation/thesis will provide solutions for the current gaps in a particular field. Unfortunately, little guidance is available on elaborating LRs, and writing an LR chapter is not a linear process. An LR translates students’ abilities in information literacy, the language domain, and critical writing. Students in postgraduate programs should be systematically trained in these skills. Therefore, this paper discusses the purposes of LRs in dissertations and theses. Second, the paper considers five steps for developing a review: defining the main topic, searching the literature, analyzing the results, writing the review and reflecting on the writing. Ultimately, this study proposes a twelve-item LR checklist. By clearly stating the desired achievements, this checklist allows Masters and Ph.D. students to continuously assess their own progress in elaborating an LR. Institutions aiming to strengthen students’ necessary skills in critical academic writing should also use this tool.

INTRODUCTION

Writing the literature review (LR) is often viewed as a difficult task that can be a point of writer’s block and procrastination ( 1 ) in postgraduate life. Disagreements on the definitions or classifications of LRs ( 2 ) may confuse students about their purpose and scope, as well as how to perform an LR. Interestingly, at many universities, the LR is still an important element in any academic work, despite the more recent trend of producing scientific articles rather than classical theses.

The LR is not an isolated section of the thesis/dissertation or a copy of the background section of a research proposal. It identifies the state-of-the-art knowledge in a particular field, clarifies information that is already known, elucidates implications of the problem being analyzed, links theory and practice ( 3 - 5 ), highlights gaps in the current literature, and places the dissertation/thesis within the research agenda of that field. Additionally, by writing the LR, postgraduate students will comprehend the structure of the subject and elaborate on their cognitive connections ( 3 ) while analyzing and synthesizing data with increasing maturity.

At the same time, the LR transforms the student and hints at the contents of other chapters for the reader. First, the LR explains the research question; second, it supports the hypothesis, objectives, and methods of the research project; and finally, it facilitates a description of the student’s interpretation of the results and his/her conclusions. For scholars, the LR is an introductory chapter ( 6 ). If it is well written, it demonstrates the student’s understanding of and maturity in a particular topic. A sound and sophisticated LR can indicate a robust dissertation/thesis.

A consensus on the best method to elaborate a dissertation/thesis has not been achieved. The LR can be a distinct chapter or included in different sections; it can be part of the introduction chapter, part of each research topic, or part of each published paper ( 7 ). However, scholars view the LR as an integral part of the main body of an academic work because it is intrinsically connected to other sections ( Figure 1 ) and is frequently present. The structure of the LR depends on the conventions of a particular discipline, the rules of the department, and the student’s and supervisor’s areas of expertise, needs and interests.

Interestingly, many postgraduate students choose to submit their LR to peer-reviewed journals. As LRs are critical evaluations of current knowledge, they are indeed publishable material, even in the form of narrative or systematic reviews. However, systematic reviews have specific patterns 1 ( 8 ) that may not entirely fit with the questions posed in the dissertation/thesis. Additionally, the scope of a systematic review may be too narrow, and the strict criteria for study inclusion may omit important information from the dissertation/thesis. Therefore, this essay discusses the definition of an LR is and methods to develop an LR in the context of an academic dissertation/thesis. Finally, we suggest a checklist to evaluate an LR.

WHAT IS A LITERATURE REVIEW IN A THESIS?

Conducting research and writing a dissertation/thesis translates rational thinking and enthusiasm ( 9 ). While a strong body of literature that instructs students on research methodology, data analysis and writing scientific papers exists, little guidance on performing LRs is available. The LR is a unique opportunity to assess and contrast various arguments and theories, not just summarize them. The research results should not be discussed within the LR, but the postgraduate student tends to write a comprehensive LR while reflecting on his or her own findings ( 10 ).

Many people believe that writing an LR is a lonely and linear process. Supervisors or the institutions assume that the Ph.D. student has mastered the relevant techniques and vocabulary associated with his/her subject and conducts a self-reflection about previously published findings. Indeed, while elaborating the LR, the student should aggregate diverse skills, which mainly rely on his/her own commitment to mastering them. Thus, less supervision should be required ( 11 ). However, the parameters described above might not currently be the case for many students ( 11 , 12 ), and the lack of formal and systematic training on writing LRs is an important concern ( 11 ).

An institutional environment devoted to active learning will provide students the opportunity to continuously reflect on LRs, which will form a dialogue between the postgraduate student and the current literature in a particular field ( 13 ). Postgraduate students will be interpreting studies by other researchers, and, according to Hart (1998) ( 3 ), the outcomes of the LR in a dissertation/thesis include the following:

- To identify what research has been performed and what topics require further investigation in a particular field of knowledge;

- To determine the context of the problem;

- To recognize the main methodologies and techniques that have been used in the past;

- To place the current research project within the historical, methodological and theoretical context of a particular field;

- To identify significant aspects of the topic;

- To elucidate the implications of the topic;

- To offer an alternative perspective;

- To discern how the studied subject is structured;

- To improve the student’s subject vocabulary in a particular field; and

- To characterize the links between theory and practice.

A sound LR translates the postgraduate student’s expertise in academic and scientific writing: it expresses his/her level of comfort with synthesizing ideas ( 11 ). The LR reveals how well the postgraduate student has proceeded in three domains: an effective literature search, the language domain, and critical writing.

Effective literature search

All students should be trained in gathering appropriate data for specific purposes, and information literacy skills are a cornerstone. These skills are defined as “an individual’s ability to know when they need information, to identify information that can help them address the issue or problem at hand, and to locate, evaluate, and use that information effectively” ( 14 ). Librarian support is of vital importance in coaching the appropriate use of Boolean logic (AND, OR, NOT) and other tools for highly efficient literature searches (e.g., quotation marks and truncation), as is the appropriate management of electronic databases.

Language domain

Academic writing must be concise and precise: unnecessary words distract the reader from the essential content ( 15 ). In this context, reading about issues distant from the research topic ( 16 ) may increase students’ general vocabulary and familiarity with grammar. Ultimately, reading diverse materials facilitates and encourages the writing process itself.

Critical writing

Critical judgment includes critical reading, thinking and writing. It supposes a student’s analytical reflection about what he/she has read. The student should delineate the basic elements of the topic, characterize the most relevant claims, identify relationships, and finally contrast those relationships ( 17 ). Each scientific document highlights the perspective of the author, and students will become more confident in judging the supporting evidence and underlying premises of a study and constructing their own counterargument as they read more articles. A paucity of integration or contradictory perspectives indicates lower levels of cognitive complexity ( 12 ).

Thus, while elaborating an LR, the postgraduate student should achieve the highest category of Bloom’s cognitive skills: evaluation ( 12 ). The writer should not only summarize data and understand each topic but also be able to make judgments based on objective criteria, compare resources and findings, identify discrepancies due to methodology, and construct his/her own argument ( 12 ). As a result, the student will be sufficiently confident to show his/her own voice .

Writing a consistent LR is an intense and complex activity that reveals the training and long-lasting academic skills of a writer. It is not a lonely or linear process. However, students are unlikely to be prepared to write an LR if they have not mastered the aforementioned domains ( 10 ). An institutional environment that supports student learning is crucial.

Different institutions employ distinct methods to promote students’ learning processes. First, many universities propose modules to develop behind the scenes activities that enhance self-reflection about general skills (e.g., the skills we have mastered and the skills we need to develop further), behaviors that should be incorporated (e.g., self-criticism about one’s own thoughts), and each student’s role in the advancement of his/her field. Lectures or workshops about LRs themselves are useful because they describe the purposes of the LR and how it fits into the whole picture of a student’s work. These activities may explain what type of discussion an LR must involve, the importance of defining the correct scope, the reasons to include a particular resource, and the main role of critical reading.

Some pedagogic services that promote a continuous improvement in study and academic skills are equally important. Examples include workshops about time management, the accomplishment of personal objectives, active learning, and foreign languages for nonnative speakers. Additionally, opportunities to converse with other students promotes an awareness of others’ experiences and difficulties. Ultimately, the supervisor’s role in providing feedback and setting deadlines is crucial in developing students’ abilities and in strengthening students’ writing quality ( 12 ).

HOW SHOULD A LITERATURE REVIEW BE DEVELOPED?

A consensus on the appropriate method for elaborating an LR is not available, but four main steps are generally accepted: defining the main topic, searching the literature, analyzing the results, and writing ( 6 ). We suggest a fifth step: reflecting on the information that has been written in previous publications ( Figure 2 ).

First step: Defining the main topic

Planning an LR is directly linked to the research main question of the thesis and occurs in parallel to students’ training in the three domains discussed above. The planning stage helps organize ideas, delimit the scope of the LR ( 11 ), and avoid the wasting of time in the process. Planning includes the following steps:

- Reflecting on the scope of the LR: postgraduate students will have assumptions about what material must be addressed and what information is not essential to an LR ( 13 , 18 ). Cooper’s Taxonomy of Literature Reviews 2 systematizes the writing process through six characteristics and nonmutually exclusive categories. The focus refers to the reviewer’s most important points of interest, while the goals concern what students want to achieve with the LR. The perspective assumes answers to the student’s own view of the LR and how he/she presents a particular issue. The coverage defines how comprehensive the student is in presenting the literature, and the organization determines the sequence of arguments. The audience is defined as the group for whom the LR is written.

- Designating sections and subsections: Headings and subheadings should be specific, explanatory and have a coherent sequence throughout the text ( 4 ). They simulate an inverted pyramid, with an increasing level of reflection and depth of argument.

- Identifying keywords: The relevant keywords for each LR section should be listed to guide the literature search. This list should mirror what Hart (1998) ( 3 ) advocates as subject vocabulary . The keywords will also be useful when the student is writing the LR since they guide the reader through the text.

- Delineating the time interval and language of documents to be retrieved in the second step. The most recently published documents should be considered, but relevant texts published before a predefined cutoff year can be included if they are classic documents in that field. Extra care should be employed when translating documents.

Second step: Searching the literature

The ability to gather adequate information from the literature must be addressed in postgraduate programs. Librarian support is important, particularly for accessing difficult texts. This step comprises the following components:

- Searching the literature itself: This process consists of defining which databases (electronic or dissertation/thesis repositories), official documents, and books will be searched and then actively conducting the search. Information literacy skills have a central role in this stage. While searching electronic databases, controlled vocabulary (e.g., Medical Subject Headings, or MeSH, for the PubMed database) or specific standardized syntax rules may need to be applied.

In addition, two other approaches are suggested. First, a review of the reference list of each document might be useful for identifying relevant publications to be included and important opinions to be assessed. This step is also relevant for referencing the original studies and leading authors in that field. Moreover, students can directly contact the experts on a particular topic to consult with them regarding their experience or use them as a source of additional unpublished documents.

Before submitting a dissertation/thesis, the electronic search strategy should be repeated. This process will ensure that the most recently published papers will be considered in the LR.

- Selecting documents for inclusion: Generally, the most recent literature will be included in the form of published peer-reviewed papers. Assess books and unpublished material, such as conference abstracts, academic texts and government reports, are also important to assess since the gray literature also offers valuable information. However, since these materials are not peer-reviewed, we recommend that they are carefully added to the LR.

This task is an important exercise in time management. First, students should read the title and abstract to understand whether that document suits their purposes, addresses the research question, and helps develop the topic of interest. Then, they should scan the full text, determine how it is structured, group it with similar documents, and verify whether other arguments might be considered ( 5 ).

Third step: Analyzing the results

Critical reading and thinking skills are important in this step. This step consists of the following components:

- Reading documents: The student may read various texts in depth according to LR sections and subsections ( defining the main topic ), which is not a passive activity ( 1 ). Some questions should be asked to practice critical analysis skills, as listed below. Is the research question evident and articulated with previous knowledge? What are the authors’ research goals and theoretical orientations, and how do they interact? Are the authors’ claims related to other scholars’ research? Do the authors consider different perspectives? Was the research project designed and conducted properly? Are the results and discussion plausible, and are they consistent with the research objectives and methodology? What are the strengths and limitations of this work? How do the authors support their findings? How does this work contribute to the current research topic? ( 1 , 19 )

- Taking notes: Students who systematically take notes on each document are more readily able to establish similarities or differences with other documents and to highlight personal observations. This approach reinforces the student’s ideas about the next step and helps develop his/her own academic voice ( 1 , 13 ). Voice recognition software ( 16 ), mind maps ( 5 ), flowcharts, tables, spreadsheets, personal comments on the referenced texts, and note-taking apps are all available tools for managing these observations, and the student him/herself should use the tool that best improves his/her learning. Additionally, when a student is considering submitting an LR to a peer-reviewed journal, notes should be taken on the activities performed in all five steps to ensure that they are able to be replicated.

Fourth step: Writing

The recognition of when a student is able and ready to write after a sufficient period of reading and thinking is likely a difficult task. Some students can produce a review in a single long work session. However, as discussed above, writing is not a linear process, and students do not need to write LRs according to a specific sequence of sections. Writing an LR is a time-consuming task, and some scholars believe that a period of at least six months is sufficient ( 6 ). An LR, and academic writing in general, expresses the writer’s proper thoughts, conclusions about others’ work ( 6 , 10 , 13 , 16 ), and decisions about methods to progress in the chosen field of knowledge. Thus, each student is expected to present a different learning and writing trajectory.

In this step, writing methods should be considered; then, editing, citing and correct referencing should complete this stage, at least temporarily. Freewriting techniques may be a good starting point for brainstorming ideas and improving the understanding of the information that has been read ( 1 ). Students should consider the following parameters when creating an agenda for writing the LR: two-hour writing blocks (at minimum), with prespecified tasks that are possible to complete in one section; short (minutes) and long breaks (days or weeks) to allow sufficient time for mental rest and reflection; and short- and long-term goals to motivate the writing itself ( 20 ). With increasing experience, this scheme can vary widely, and it is not a straightforward rule. Importantly, each discipline has a different way of writing ( 1 ), and each department has its own preferred styles for citations and references.

Fifth step: Reflecting on the writing

In this step, the postgraduate student should ask him/herself the same questions as in the analyzing the results step, which can take more time than anticipated. Ambiguities, repeated ideas, and a lack of coherence may not be noted when the student is immersed in the writing task for long periods. The whole effort will likely be a work in progress, and continuous refinements in the written material will occur once the writing process has begun.

LITERATURE REVIEW CHECKLIST

In contrast to review papers, the LR of a dissertation/thesis should not be a standalone piece or work. Instead, it should present the student as a scholar and should maintain the interest of the audience in how that dissertation/thesis will provide solutions for the current gaps in a particular field.

A checklist for evaluating an LR is convenient for students’ continuous academic development and research transparency: it clearly states the desired achievements for the LR of a dissertation/thesis. Here, we present an LR checklist developed from an LR scoring rubric ( 11 ). For a critical analysis of an LR, we maintain the five categories but offer twelve criteria that are not scaled ( Figure 3 ). The criteria all have the same importance and are not mutually exclusive.

First category: Coverage

1. justified criteria exist for the inclusion and exclusion of literature in the review.

This criterion builds on the main topic and areas covered by the LR ( 18 ). While experts may be confident in retrieving and selecting literature, postgraduate students must convince their audience about the adequacy of their search strategy and their reasons for intentionally selecting what material to cover ( 11 ). References from different fields of knowledge provide distinct perspective, but narrowing the scope of coverage may be important in areas with a large body of existing knowledge.

Second category: Synthesis

2. a critical examination of the state of the field exists.

A critical examination is an assessment of distinct aspects in the field ( 1 ) along with a constructive argument. It is not a negative critique but an expression of the student’s understanding of how other scholars have added to the topic ( 1 ), and the student should analyze and contextualize contradictory statements. A writer’s personal bias (beliefs or political involvement) have been shown to influence the structure and writing of a document; therefore, the cultural and paradigmatic background guide how the theories are revised and presented ( 13 ). However, an honest judgment is important when considering different perspectives.

3. The topic or problem is clearly placed in the context of the broader scholarly literature

The broader scholarly literature should be related to the chosen main topic for the LR ( how to develop the literature review section). The LR can cover the literature from one or more disciplines, depending on its scope, but it should always offer a new perspective. In addition, students should be careful in citing and referencing previous publications. As a rule, original studies and primary references should generally be included. Systematic and narrative reviews present summarized data, and it may be important to cite them, particularly for issues that should be understood but do not require a detailed description. Similarly, quotations highlight the exact statement from another publication. However, excessive referencing may disclose lower levels of analysis and synthesis by the student.

4. The LR is critically placed in the historical context of the field

Situating the LR in its historical context shows the level of comfort of the student in addressing a particular topic. Instead of only presenting statements and theories in a temporal approach, which occasionally follows a linear timeline, the LR should authentically characterize the student’s academic work in the state-of-art techniques in their particular field of knowledge. Thus, the LR should reinforce why the dissertation/thesis represents original work in the chosen research field.

5. Ambiguities in definitions are considered and resolved

Distinct theories on the same topic may exist in different disciplines, and one discipline may consider multiple concepts to explain one topic. These misunderstandings should be addressed and contemplated. The LR should not synthesize all theories or concepts at the same time. Although this approach might demonstrate in-depth reading on a particular topic, it can reveal a student’s inability to comprehend and synthesize his/her research problem.

6. Important variables and phenomena relevant to the topic are articulated

The LR is a unique opportunity to articulate ideas and arguments and to purpose new relationships between them ( 10 , 11 ). More importantly, a sound LR will outline to the audience how these important variables and phenomena will be addressed in the current academic work. Indeed, the LR should build a bidirectional link with the remaining sections and ground the connections between all of the sections ( Figure 1 ).

7. A synthesized new perspective on the literature has been established

The LR is a ‘creative inquiry’ ( 13 ) in which the student elaborates his/her own discourse, builds on previous knowledge in the field, and describes his/her own perspective while interpreting others’ work ( 13 , 17 ). Thus, students should articulate the current knowledge, not accept the results at face value ( 11 , 13 , 17 ), and improve their own cognitive abilities ( 12 ).

Third category: Methodology

8. the main methodologies and research techniques that have been used in the field are identified and their advantages and disadvantages are discussed.

The LR is expected to distinguish the research that has been completed from investigations that remain to be performed, address the benefits and limitations of the main methods applied to date, and consider the strategies for addressing the expected limitations described above. While placing his/her research within the methodological context of a particular topic, the LR will justify the methodology of the study and substantiate the student’s interpretations.

9. Ideas and theories in the field are related to research methodologies

The audience expects the writer to analyze and synthesize methodological approaches in the field. The findings should be explained according to the strengths and limitations of previous research methods, and students must avoid interpretations that are not supported by the analyzed literature. This criterion translates to the student’s comprehension of the applicability and types of answers provided by different research methodologies, even those using a quantitative or qualitative research approach.

Fourth category: Significance

10. the scholarly significance of the research problem is rationalized.

The LR is an introductory section of a dissertation/thesis and will present the postgraduate student as a scholar in a particular field ( 11 ). Therefore, the LR should discuss how the research problem is currently addressed in the discipline being investigated or in different disciplines, depending on the scope of the LR. The LR explains the academic paradigms in the topic of interest ( 13 ) and methods to advance the field from these starting points. However, an excess number of personal citations—whether referencing the student’s research or studies by his/her research team—may reflect a narrow literature search and a lack of comprehensive synthesis of ideas and arguments.

11. The practical significance of the research problem is rationalized

The practical significance indicates a student’s comprehensive understanding of research terminology (e.g., risk versus associated factor), methodology (e.g., efficacy versus effectiveness) and plausible interpretations in the context of the field. Notably, the academic argument about a topic may not always reflect the debate in real life terms. For example, using a quantitative approach in epidemiology, statistically significant differences between groups do not explain all of the factors involved in a particular problem ( 21 ). Therefore, excessive faith in p -values may reflect lower levels of critical evaluation of the context and implications of a research problem by the student.

Fifth category: Rhetoric

12. the lr was written with a coherent, clear structure that supported the review.

This category strictly relates to the language domain: the text should be coherent and presented in a logical sequence, regardless of which organizational ( 18 ) approach is chosen. The beginning of each section/subsection should state what themes will be addressed, paragraphs should be carefully linked to each other ( 10 ), and the first sentence of each paragraph should generally summarize the content. Additionally, the student’s statements are clear, sound, and linked to other scholars’ works, and precise and concise language that follows standardized writing conventions (e.g., in terms of active/passive voice and verb tenses) is used. Attention to grammar, such as orthography and punctuation, indicates prudence and supports a robust dissertation/thesis. Ultimately, all of these strategies provide fluency and consistency for the text.

Although the scoring rubric was initially proposed for postgraduate programs in education research, we are convinced that this checklist is a valuable tool for all academic areas. It enables the monitoring of students’ learning curves and a concentrated effort on any criteria that are not yet achieved. For institutions, the checklist is a guide to support supervisors’ feedback, improve students’ writing skills, and highlight the learning goals of each program. These criteria do not form a linear sequence, but ideally, all twelve achievements should be perceived in the LR.

CONCLUSIONS

A single correct method to classify, evaluate and guide the elaboration of an LR has not been established. In this essay, we have suggested directions for planning, structuring and critically evaluating an LR. The planning of the scope of an LR and approaches to complete it is a valuable effort, and the five steps represent a rational starting point. An institutional environment devoted to active learning will support students in continuously reflecting on LRs, which will form a dialogue between the writer and the current literature in a particular field ( 13 ).

The completion of an LR is a challenging and necessary process for understanding one’s own field of expertise. Knowledge is always transitory, but our responsibility as scholars is to provide a critical contribution to our field, allowing others to think through our work. Good researchers are grounded in sophisticated LRs, which reveal a writer’s training and long-lasting academic skills. We recommend using the LR checklist as a tool for strengthening the skills necessary for critical academic writing.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Leite DFB has initially conceived the idea and has written the first draft of this review. Padilha MAS and Cecatti JG have supervised data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read the draft and agreed with this submission. Authors are responsible for all aspects of this academic piece.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to all of the professors of the ‘Getting Started with Graduate Research and Generic Skills’ module at University College Cork, Cork, Ireland, for suggesting and supporting this article. Funding: DFBL has granted scholarship from Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) to take part of her Ph.D. studies in Ireland (process number 88881.134512/2016-01). There is no participation from sponsors on authors’ decision to write or to submit this manuscript.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

1 The questions posed in systematic reviews usually follow the ‘PICOS’ acronym: Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study design.