Reference management. Clean and simple.

The key parts of a scientific poster

Why make a scientific poster?

Type of poster formats, sections of a scientific poster, before you start: tips for making a scientific poster, the 6 technical elements of a scientific poster, 3. typography, 5. images and illustrations, how to seek feedback on your poster, how to present your poster, tips for the day of your poster presentation, in conclusion, other sources to help you with your scientific poster presentation, frequently asked questions about scientific posters, related articles.

A poster presentation provides the opportunity to show off your research to a broad audience and connect with other researchers in your field.

For junior researchers, presenting a poster is often the first type of scientific presentation they give in their careers.

The discussions you have with other researchers during your poster presentation may inspire new research ideas, or even lead to new collaborations.

Consequently, a poster presentation can be just as professionally enriching as giving an oral presentation , if you prepare for it properly.

In this guide post, you will learn:

- The goal of a scientific poster presentation

- The 6 key elements of a scientific poster

- How to make a scientific poster

- How to prepare for a scientific poster presentation

- ‘What to do on the day of the poster session.

Our advice comes from our previous experiences as scientists presenting posters at conferences.

Posters can be a powerful way for showcasing your data in scientific meetings. You can get helpful feedback from other researchers as well as expand your professional network and attract fruitful interactions with peers.

Scientific poster sessions tend to be more relaxed than oral presentation sessions, as they provide the opportunity to meet with peers in a less formal setting and to have energizing conversations about your research with a wide cross-section of researchers.

- Physical posters: A poster that is located in an exhibit hall and pinned to a poster board. Physical posters are beneficial since they may be visually available for the duration of a meeting, unlike oral presentations.

- E-posters: A poster that is shown on a screen rather than printed and pinned on a poster board. E-posters can have static or dynamic content. Static e-posters are slideshow presentations consisting of one or more slides, whereas dynamic e-posters include videos or animations.

Some events allow for a combination of both formats.

The sections included in a scientific poster tend to follow the format of a scientific paper , although other designs are possible. For example, the concept of a #betterposter was invented by PhD student Mike Morrison to address the issue of poorly designed scientific posters. It puts the take-home message at the center of the poster and includes a QR code on the poster to learn about further details of the project.

| Poster section | Description |

|---|---|

Heading | The title of your research project, and one of the most important features of your poster. Use a specific and informative headline to attract interest from passers-by. Logos for funding agencies and institutions hosting the research project are often placed on either side of the heading. |

Subheading | List of contributing authors, affiliations, and contact details of corresponding author (usually the person presenting the poster). List the authors in the same order as on the publication. |

Introduction | Includes only essential background information as well as the goals of the study. Keep it brief, and use bullet points. The introduction should also highlight the novelty of your research. |

Methods | A chronological order of the steps and techniques used in your project. Include an image or diagram representing your study system if possible. |

Results | Has at most 3 graphs showing the key findings of your study, along with short descriptions. This section should occupy the most space on your poster. |

Conclusion | Summarizes the take-home message of your work. |

References | Includes the key sources used in your study. Have at most 6 references listed. |

Acknowledgments | List funding sources, and contributions from anyone who helped with the research. |

- Anticipate who your audience during the poster session will be—this will depend on the type of meeting. For example, presenting during a poster session at a large conference may attract a broad audience of generalists and specialists at a variety of career stages. You would like for your poster to appeal to all of these groups. You can achieve this by making the main message accessible through eye-catching figures, concise text, and an interesting title.

- Your goal in a poster session is to get your research noticed and to have interesting conversations with attendees. Your poster is a visual aid for the talks you will give, so having a well-organized, clear, and informative poster will help achieve your aim.

- Plan the narrative of your poster. Start by deciding the key take-home message of your presentation, and create a storyboard prioritizing the key findings that indicate the main message. Your storyboard can be a simple sketch of the poster layout, or you can use digital tools to make it. Present your results in a logical order, with the most important result in the center of the poster.

- Give yourself enough time to create a draft of your poster, and to get feedback on it. Since waiting to receive feedback, revising your poster, and sending the final version to the printers may take a few days, it is sensible to give yourself at least 1-2 weeks to make your poster.

- Check if the meeting has specific poster formatting requirements, and if your institution has a poster template with logos and color schemes that you can use. Poster templates can also be found online and can be adapted for use.

- Know where you will get your poster printed, and how long it typically takes to receive the printed poster.

- Ensure you write a specific and informative poster abstract, because specialists in your field may decide to visit your poster based on its quality. This is especially true in large meetings where viewers will choose what posters to visit before the poster session begins because it isn’t possible to read every poster.

➡️ Learn more about how to write an abstract

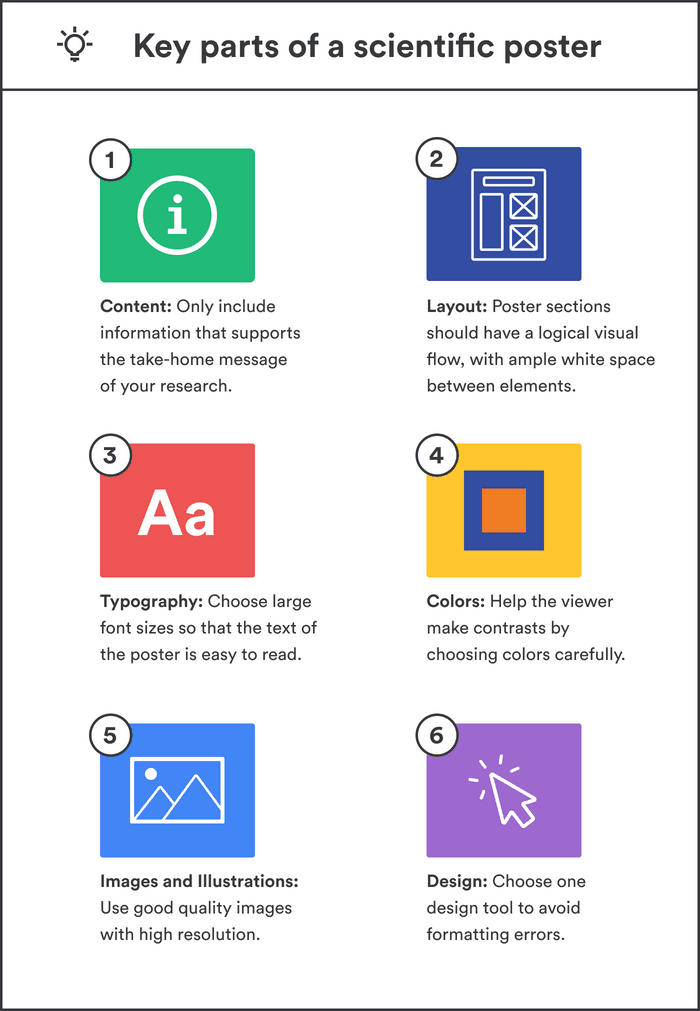

The technical elements of a scientific poster are:

- Images and Illustrations

Don’t be tempted to cram your entire paper into your poster—details that you omit can be brought up during conversations with viewers. Only include information that is useful for supporting your take-home message. Place your core message in the center of your poster, using either text or visual elements. Avoid jargon, and use concise text elements (no more than 10 lines and 50 words long). Present your data in graphs rather than in tabular form, as it can be difficult for visitors to extract the most important information from tables. Use bullet points and numbered lists to make text content easy to read. Your poster shouldn’t have more than 800 words.

Poster sections should have a logical visual flow, ideally in a longitudinal fashion. For example, in an article on poster presentations published in Nature , scientific illustrator Jamie Simon recommends using the law of thirds to display your research—a 3-column layout with 3 blocks per column. Headings, columns, graphs, and diagrams should be aligned and distributed with enough spacing and balance. The text should be left-aligned while maintaining an appropriate amount of "white space' i.e., areas devoid of any design elements.

To ensure the title is visible from 5 meters away, use a sans serif 85pt font. The body text should use a minimum of 24pt serif font so that it can be read from a one-meter distance. Section headings and subheadings should be in bold. Avoid underlining text and using all capitals in words; instead, a mixture of boldface and italics should be used for emphasis. Use adequate line spacing and one-inch margins to give a clean, uncluttered look.

Appropriate use of color can help readers make comparisons and contrasts in your figures. Account for the needs of color-blind viewers by not using red and green together, and using symbols and dashed lines in your figures. Use a white background for your poster, and black text.

Include no more than 4 figures, with a prominent centerpiece figure in the middle of the poster of your study system or main finding. Dimensions for illustrations, diagrams, and figures should be consistent. When inserting charts, avoid gray backgrounds and grid lines to prevent ink consumption and an unaesthetic look. Graphics used must have proper labels, legible axes, and be adequately sized. Images with a 200 dpi or higher resolution are preferred. If you obtain an image from the internet, make sure it has a high enough resolution and is available in the public domain.

Tools for poster design include Microsoft PowerPoint, Microsoft Publisher, Adobe Illustrator, In Design, Scribus, Canva, Impress, Google Slides, and LaTeX. When starting with the design, the page size should be identical to the final print size. Stick to one design tool to avoid formatting errors.

Have at least one proofreading and feedback round before you print your final poster by following these steps:

- Share your poster draft with your advisor, peers, and ideally, at least one person outside of your field to get feedback.

- Allow time to revise your poster and implement the comments you’ve received.

- Before printing, proofread your final draft. You can use a spelling and grammar-checking tool, or print out a small version of the poster to help locate typos and redundant text.

Before giving a poster presentation, you need to be ready to discuss your research.

- For large meetings where viewers of your poster have a range of specialties, prepare 2-3 levels for your speech, starting with a one-minute talk consisting of key background information and take-home messages. Prepare separate short talks for casual viewers with varying levels of interest in your topic, ranging from "very little" to "some".

- Prepare a 3-5 minute presentation explaining the methods and results for those in your audience with an advanced background.

- Anticipate possible questions that could arise during your presentation and prepare answers for them.

- Practice your speech. You can ask friends, family, or fellow lab members to listen to your practice sessions and provide feedback.

Here we provide a checklist for your presentation day:

- Arrive early—often exhibition halls are large and it can take some time to find the allocated spot for your poster. Bring tape and extra pins to put up your poster properly.

- Wear professional attire and comfortable shoes.

- Be enthusiastic. Start the conversation by introducing yourself and requesting the attendee’s name and field of interest, and offering to explain your poster briefly. Maintain eye contact with attendees visiting your poster while pointing to relevant figures and charts.

- Ask visitors what they know about your topic so that you can tailor your presentation accordingly.

- Some attendees prefer to read through your poster first and then ask you questions. You can still offer to give a brief explanation of your poster and then follow up by answering their questions.

- When you meet with visitors to your poster, you are having a conversation, so you can also ask them questions. If you are not sure they understand what you are saying, ask if your explanation makes sense to them, and clarify points where needed.

- Be professional. Stand at your poster for the duration of the session, and prioritize being available to meet with visitors to your poster over socializing with friends or lab mates. Pay due attention to all visitors at once by acknowledging visitors waiting to speak with you.

A scientific poster is an excellent method to present your work and network with peers. Preparation is essential before your poster session, which includes planning your layout, drafting your poster, practicing your speech, and preparing answers to anticipated questions. The effort invested in preparing your poster will be returned by stimulating conversations during the poster session and greater awareness of your work in your scientific community.

➡️ How to prepare a scientific poster

➡️ Conference presentations: Lead the poster parade

➡️ Designing conference posters

A scientific poster can be used to network with colleagues, get feedback on your research and get recognition as a researcher.

A scientific poster should include a main heading, introduction, methods, results, conclusion, and references.

An e-poster is a poster fashioned as a slideshow presentation that plays on a digital screen, with each slide carrying a sliver of information.

A handful of tools can be used to design a poster including Microsoft PowerPoint, Microsoft Publisher, Illustrator, In Design, Photoshop, Impress, and LaTeX.

Start the conversation by introducing yourself and requesting the attendees' names, affiliations, and fields of interest, and offering to explain your poster briefly. Alternatively, you can give attendees ample time to read through your poster first and then offer to explain your poster in 10 seconds followed by questions and answers.

How To Make an Academic Poster: Eye-Catching Poster Guide

Explore the strategies on how to make academic poster that engage and educate with precision with our ultimate guide.

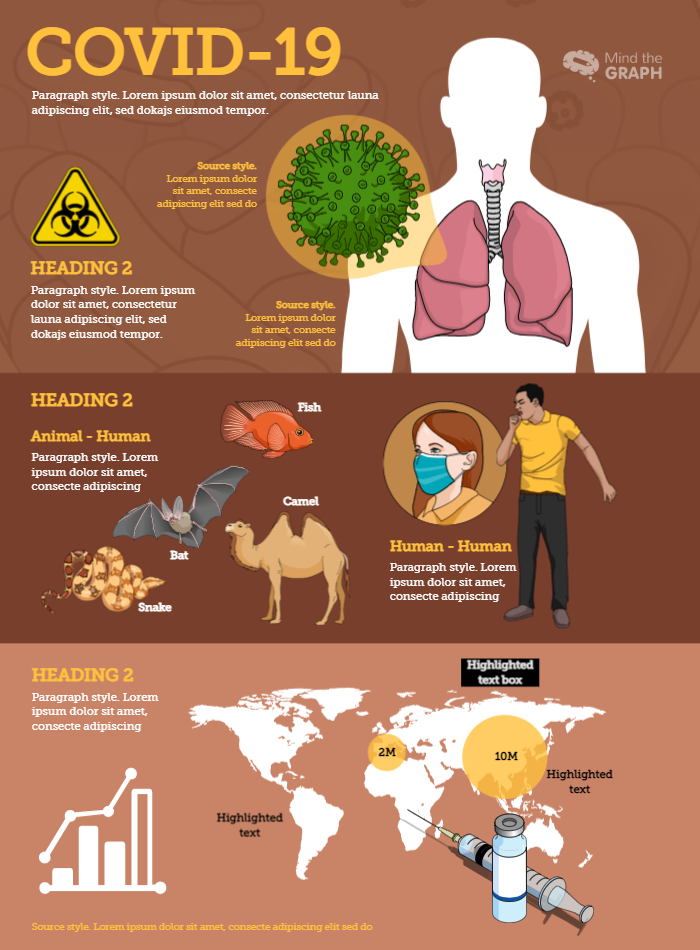

Are you a scientist or researcher looking to create an eye-catching academic poster? Look no further! In this ultimate guide, we will walk you through the step-by-step process of making an engaging and visually striking academic poster. Whether you’re a beginner or a seasoned professional, we’ve got you covered. We understand the challenge researchers face in visualizing complex scientific data without specialized design skills, which is why we’ve developed Mind the Graph. Our online platform offers a user-friendly experience, allowing you to easily create visually appealing figures, infographics, graphical abstracts, presentations, and of course, posters. With over 75,000 scientifically accurate illustrations in 80+ fields, Mind the Graph is the best free infographic maker for science. Get ready to take your scientific communication to the next level!

Understanding Academic Posters

Importance of academic posters.

Academic posters are a critical medium for communicating complex scientific data in a visually digestible format. They serve a pivotal role at scientific conferences, symposiums, and seminars, offering researchers a platform to showcase their work, share findings, and promote dialogue within the scientific community. An effective academic poster can engage the audience, encourage questions, and spark meaningful conversations, thereby leading to new collaborations and insights. However, making an academic poster that stands out is not an easy task. It requires the ability to simplify intricate data into a concise, visually appealing, and comprehensible format that can quickly grab the attention of passersby. This is where tools like Mind the Graph come into play, providing a user-friendly platform to create striking academic posters and enhance scientific communication.

Design Elements of Effective Posters

An effective academic poster is not just about presenting data; it also requires thoughtful design elements to engage the audience and communicate the research effectively. Here are some critical design elements to consider:

- Clarity : Clarity is key. The poster should present the research in a concise, straightforward manner, avoiding unnecessary jargon.

- Visual appeal : Use graphics and visuals to present complex data, making it easier for the audience to understand.

- Organization : The layout should guide the viewer’s eye from the title, introduction, methods, results, and finally the conclusion, in a logical order.

- Typography : Choose fonts that are easy to read from a distance. Make sure there’s a contrast between the text and the background color.

- Color Scheme : Choose a color scheme that’s pleasing to the eye and aligns with the research theme.

- Simplicity : Don’t overcrowd the poster with too much information. Less is more.

Remember, the primary goal of an academic poster is to attract attention, present information clearly, and stimulate discussion. Therefore, a well-designed poster can significantly enhance your academic communication and showcase your research effectively.

Steps to Create an Eye-Catching Academic Poster

Selecting key content for your poster.

The first step in creating an effective academic poster is to select the key content that will be displayed. You need to distill your research into a concise and clear message that can be conveyed visually. To do this, consider the following:

- Focus on the main findings : Highlight your most important findings or conclusions. These should take center stage in your poster.

- Simplify your methods : While it’s important to mention the methods used in your research, they should be simplified to a high-level overview. Save the detailed explanations for conversations with viewers.

- Use visuals : Whenever possible, use graphs, charts, or images to represent your data. Visuals can convey information more quickly and memorably than text alone.

- Include contact information : Ensure viewers can follow up on your research by including your contact information and any relevant social media or website links.

Remember, the goal is to engage viewers in a conversation about your work, so it’s important to leave some details for in-person discussions. Selecting key content carefully will ensure that your academic poster is effective and engaging.

Structuring Your Poster for Visual Flow

Once you’ve selected the key content for your academic poster, the next step is to structure it for a seamless visual flow. The aim is to guide your viewer’s eye through your poster naturally and logically. Here’s how you can achieve this:

- Title : Place the title at the top center of your poster. It should be the largest text on the poster to draw attention.

- Introduction : Below the title, provide a brief introduction to your research. This should give the viewer a quick understanding of the context and purpose of your study.

- Methods and Results : Following the introduction, present your methods and results. Use visuals like charts, graphs, or images wherever possible.

- Conclusion : Towards the end of the poster, summarize your findings and their implications. This should tie back to the introduction and provide a clear takeaway for the viewer.

- Contact Information : Finally, include your contact details at the bottom of the poster for viewers who want to discuss your research further or follow up later.

Remember to use ample whitespace to avoid clutter and ensure each section of content stands out. The layout should guide the viewer’s eye smoothly from the title to the conclusion, facilitating an easy understanding of your research.

Utilizing Mind the Graph Tools

Overview of mind the graph features.

Mind the Graph is an online platform designed to help you create visually appealing and scientifically accurate infographics for your research. Here are some of the key features that make Mind the Graph an invaluable tool for researchers:

- Extensive Illustration Library : Mind the Graph boasts over 40,000 scientifically accurate illustrations across 80+ fields of study. This vast library allows you to visually represent a wide range of scientific concepts, enhancing your ability to communicate complex ideas effectively.

- User-Friendly Design Interface : The platform’s design interface is intuitive and easy to navigate, making it accessible to beginners and professionals alike. You can drag and drop illustrations, resize elements, change colors, and customize your layout with ease.

- Customizable Templates : Mind the Graph offers a variety of customizable templates for different types of scientific communication materials, including posters. These templates provide a great starting point for your design.

- Downloadable Outputs : Once your design is complete, you can download your infographic in high-resolution formats suitable for printing or online sharing.

By leveraging these features, you can significantly enhance the visual appeal and effectiveness of your academic poster.

Creating Your Poster on Mind the Graph

Creating an academic poster on Mind the Graph is a straightforward process, thanks to its user-friendly interface:

- Select a Template : Start by choosing a template that suits your research topic and the information you want to present. Each template provides a well-structured starting point that you can customize to fit your needs.

- Add Your Content : Next, add your research content to the template. You can input text, import images, and use the platform’s extensive library of scientific illustrations to visually represent your data and findings.

- Customize Design Elements : Customize the poster’s design elements to suit your style and preference. Change the colors, adjust the fonts, resize images, and arrange elements to create an effective visual flow.

- Review and Refine : Once you’ve added all your content, review the design for clarity, visual appeal, and logical flow. Make necessary adjustments to ensure your poster communicates your research effectively.

- Download and Share : Finally, download the finished poster in a high-resolution format suitable for printing or digital sharing.

With Mind the Graph, you can create an eye-catching academic poster that effectively communicates your research and captures your audience’s attention.

Tips for Effective Poster Presentation

Engaging your audience.

Presenting your academic poster offers a unique opportunity to engage your audience directly and stimulate meaningful discussions about your research. Here are some tips to effectively engage your audience:

- Prepare a Short Pitch : Have a concise, engaging summary of your research ready to deliver when someone approaches your poster. This should highlight the key findings and the significance of your work.

- Be Approachable : Stand near your poster and be open to questions and discussions. A warm, welcoming demeanor can encourage more people to stop by and engage with your work.

- Ask Questions : Encourage interaction by asking viewers specific questions related to your research. This not only fosters engagement but can also provide valuable insights.

- Use Non-Technical Language : When discussing your research, avoid using jargon. Instead, explain your work in a way that’s accessible to people outside your field.

- Provide Takeaways : Have key takeaways ready for your audience. These could be insightful observations, implications of your research, or potential future work.

Remember, your goal is to engage viewers in a meaningful conversation about your work, and these tips can help make your poster presentation more interactive and effective.

Do’s and Don’ts of Poster Presentation

While presenting your academic poster, it’s essential to follow some do’s and don’ts to ensure an effective presentation. Here are some tips:

Do’s :

- Practice your pitch : Practice a summary of your research that you can deliver in under a minute. This can help you confidently explain your work to anyone who stops by your poster.

- Stand by your poster : Be present at your poster as much as possible during the poster session. This allows you to engage with viewers and answer any questions they may have.

- Use simple language : Explain your research in simple, accessible language. Try to avoid jargon or overly complex explanations.

Don’ts :

- Don’t overcrowd your poster : While it’s important to present your research comprehensively, avoid overcrowding your poster with too much information. Remember, less is more.

- Don’t be passive : Don’t just stand aside and let viewers read your poster. Engage them in conversation and explain your research.

- Don’t forget to provide context : Ensure you provide enough context for your research so viewers can understand its relevance and significance.

By following these do’s and don’ts, you can ensure a successful and effective poster presentation.

Elevate your research with captivating visuals using Mind the Graph

Mind the Graph platform offers customizable scientific illustrations, templates, and design tools, empowering scientists to create engaging figures that effectively convey their findings. With features to integrate data into graphs and customize colors, fonts, and styles, researchers can personalize their visuals to reflect their unique research style, making their work more accessible and memorable to a wider audience.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Sign Up for Free

Try the best infographic maker and promote your research with scientifically-accurate beautiful figures

no credit card required

About Fabricio Pamplona

Fabricio Pamplona is the founder of Mind the Graph - a tool used by over 400K users in 60 countries. He has a Ph.D. and solid scientific background in Psychopharmacology and experience as a Guest Researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry (Germany) and Researcher in D'Or Institute for Research and Education (IDOR, Brazil). Fabricio holds over 2500 citations in Google Scholar. He has 10 years of experience in small innovative businesses, with relevant experience in product design and innovation management. Connect with him on LinkedIn - Fabricio Pamplona .

Content tags

Undergraduate Research Center

An academic poster is one of many ways to communicate your research or scholarship. Researchers use books, talks, teaching, journal articles, press releases, popular media to communicate their findings. An academic poster, when done effectively, is a way to showcase your work at conferences and meetings in a concise and aesthetically pleasing format. It is a summary of your research project.

At a poster session, your ultimate goal is to share the story of your work with as many people as possible. This will give you the opportunity to network with people that may be future advisers, employers, or collaborators and you can receive important feedback on your work. To bring people in, your poster should communicate the topic quickly and include visual elements such as pictures, graphs, maps and diagrams as well as text. At its core, an effective poster is centered on a concise and powerful story. With the help of visuals, the presenter can share the story of the work in just five minutes.

Getting started with the poster:

- Are there any guidelines from the event or conference? Poster size and orientation? Required elements? (Be sure to size your poster or use a correctly sized template before you start designing!

- Posters can do "all the talking" or "some of the talking" or "highlights" the talking depending on whether the poster is meant to stand alone or be presented along side a presenter or team of presenters? Take this into consideration when deciding how much content you want to place on the poster. Word amount may also vary by field.

- What software will you use? PowerPoint is commonly used, but other illustration software applications can work well, too.

- What are the authors and in what order? Consult with your faculty research adviser on who should be included.

- Sketch out a layout. Make some rough drafts. Prioritize information giving the most important information a larger amount of space on the poster. Create an organized and logical pathway for reading the poster.

- Introduction/Background (do not put abstract on your poster unless required) - Provides context, clearly states your hypothesis, why are you asking the research question/

- Materials and methods - research strategy, how you carried it out

- Results - what did you find out? Briefly discuss data

- Conclusions/Discussion/Next Steps - Focus on main takeaway points, what is the significance, future research

- Publications cited - only most relevant.

- Acknowledgements - thank individuals who contributed to your project and always acknowledge funding sources

- Select visuals: graphs, charts, photos, graphic models. Make sure visuals are meaningful. Use the BEST ones not all the ones!

View the gallery of sample posters to start getting ideas and check out the resources listed below:

- More on making an effective poster

- General poster design principles

You will find many templates for posters on line, but remember that a template is just a guideline and you will need to resize sections and enter headings, photos and graphic components to create a poster that will be a visually engaging communication of your research. Ask your research mentor(s) for recommendations.

Before It's Printed

Proofread! Proofread! Proofread! Double check your captions and labels and numbers on your figures/graphs/charts. Read the content out loud. Have someone else proofread it.

Presenting your poster (the "pitch")

Your poster talk summarizes your research project in a clear, concise and captivating way. Consider your audience. Some conferences have general audiences and some will be conferences for specific fields and have attendees very knowledgeable in your field. The UC Davis Undergraduate Research, Scholarship and Creative activities conference attendees will include faculty, students, staff, friends, family, community college attendees and the general public. So you may need to modulate your presentation depending on the type of attendee. You can consider using questions such as "Are you familiar with..." or "Do you have a background in...". This can help you know to include more background and use more general terms for those unacquainted with your field or if you can include more field specific terms.

You will be standing to the side of your poster (not in front of it). Point to relevant parts of the poster so people can follow as you talk through it. Remember to also keep looking back to your audience to keep them engaged and feeling involved. Stay enthusiastic - your research is exciting!

A "tour" of your poster should be about 5 minutes at a comfortable, conversational pace. Poster presentations are often interactive.

Before you present

Practice! Practice! Practice! Practice with your mentors, colleagues, friends, room mates, etc. Ask them for feedback and what kind of questions they have so you can prepare for likely questions.

Creating a Poster

What exactly is a poster presentation.

A poster presentation combines text and graphics to present your project in a way that is visually interesting and accessible. It allows you to display your work to a large group of other scholars and to talk to and receive feedback from interested viewers.

Poster sessions have been very common in the sciences for some time, and they have recently become more popular as forums for the presentation of research in other disciplines like the social sciences, service learning, the humanities, and the arts.

Poster presentation formats differ from discipline to discipline, but in every case, a poster should clearly articulate what you did, how you did it, why you did it, and what it contributes to your field and the larger field of human knowledge.

What goals should I keep in mind as I construct my poster?

- Clarity of content. You will need to decide on a small number of key points that you want your viewers to take away from your presentation, and you will need to articulate those ideas clearly and concisely.

- Visual interest and accessibility. You want viewers to notice and take interest in your poster so that they will pause to learn more about your project, and you will need the poster’s design to present your research in a way that is easy for those viewers to make sense of it.

Who will be viewing my poster?

The answer to this question depends upon the context in which you will be presenting your poster. If you are presenting at a conference in your field, your audience will likely contain mostly people who will be familiar with the basic concepts you’re working with, field-specific terminology, and the main debates facing your field and informing your research. This type of audience will probably most interested in clear, specific accounts of the what and the how of your project.

If you are presenting in a setting where some audience members may not be as familiar with your area of study, you will need to explain more about the specific debates that are current in your field and to define any technical terms you use. This audience will be less interested in the specific details and more interested in the what and why of your project—that is, your broader motivations for the project and its impact on their own lives.

How do I narrow my project and choose what to put on my poster?

Probably less than you would like! One of the biggest pitfalls of poster presentations is filling your poster with so much text that it overwhelms your viewers and makes it difficult for them to tell which points are the most important. Viewers should be able to skim the poster from several feet away and easily make out the most significant points.

The point of a poster is not to list every detail of your project. Rather, it should explain the value of your research project. To do this effectively, you will need to determine your take-home message. What is the single most important thing you want your audience to understand, believe, accept, or do after they see your poster?

Once you have an idea about what that take-home message is, support it by adding some details about what you did as part of your research, how you did it, why you did it, and what it contributes to your field and the larger field of human knowledge.

What kind of information should I include about what I did?

This is the raw material of your research: your research questions, a succinct statement of your project’s main argument (what you are trying to prove), and the evidence that supports that argument. In the sciences, the what of a project is often divided into its hypothesis and its data or results. In other disciplines, the what is made up of a claim or thesis statement and the evidence used to back it up.

Remember that your viewers won’t be able to process too much detailed evidence; it’s your job to narrow down this evidence so that you’re providing the big picture. Choose a few key pieces of evidence that most clearly illustrate your take-home message. Often a chart, graph, table, photo, or other figure can help you distill this information and communicate it quickly and easily.

What kind of information should I include about how I did it?

Include information about the process you followed as you conducted your project. Viewers will not have time to wade through too many technical details, so only your general approach is needed. Interested viewers can ask you for details.

What kind of information should I include about why I did it?

Give your audience an idea about your motivation for this project. What real-world problems or questions prompted you to undertake this project? What field-specific issues or debates influenced your thinking? What information is essential for your audience to be able to understand your project and its significance? In some disciplines, this information appears in the background or rationale section of a paper.

What kind of information should I include about its contribution ?

Help your audience to see what your project means for you and for them. How do your findings impact scholars in your field and members of the broader intellectual community? In the sciences, this information appears in the discussion section of a paper.

How will the wording of my ideas on my poster be different from my research paper?

In general, you will need to simplify your wording. Long, complex sentences are difficult for viewers to absorb and may cause them to move on to the next poster. Poster verbiage must be concise, precise, and straightforward. And it must avoid jargon. Here is an example:

Wording in a paper: This project sought to establish the ideal specifications for clinically useful wheelchair pressure mapping systems, and to use these specifications to influence the design of an innovative wheelchair pressure mapping system.

Wording on a poster:

Aims of study

- Define the ideal wheelchair pressure mapping system

- Design a new system to meet these specifications

Once I have decided what to include, how do I actually design my poster?

The effectiveness of your poster depends on how quickly and easily your audience can read and interpret it, so it’s best to make your poster visually striking. You only have a few seconds to grab attention as people wander past your poster; make the most of those seconds!

How are posters usually laid out?

In general, people expect information to flow left-to-right and top-to-bottom. Viewers are best able to absorb information from a poster with several columns that progress from left to right.

Even within these columns, however, there are certain places where viewers’ eyes naturally fall first and where they expect to find information.

Imagine your poster with an upside-down triangle centered from the top to the bottom. It is in this general area that people tend to look first and is often used for the title, results, and conclusions. Secondary and supporting information tend to fall to the sides, with the lower right having the more minor information such as acknowledgements (including funding), and personal contact information.

- Main Focus Area Location of research fundamentals: Title, Authors, Institution, Abstract, Results, Conclusion

- Secondary Emphasis Location of important info: Intro, Results or Findings, Summary

- Supporting Area Location of supporting info: Methods, Discussion

- Final Info Area Location of supplemental info: References, Acknowledgments

How much space should I devote to each section?

This will depend on the specifics of your project. In general, remember that how much space you devote to each idea suggests how important that section is. Make sure that you allot the most space to your most important points.

How much white space should I leave on my poster?

White space is helpful to your viewers; it delineates different sections, leads the eye from one point to the next, and keeps the poster from being visually overwhelming. In general, leave 10—30% of your poster as white space.

Should I use graphics?

Absolutely! Visual aids are one of the most effective ways to make your poster visually striking, and they are often a great way to communicate complex information straightforwardly and succinctly. If your project deals with lots of empirical data, your best bet will be a chart, graph, or table summarizing that data and illustrating how that data confirms your hypothesis.

If you don’t have empirical data, you may be able to incorporate photographs, illustrations, annotations, or other items that will pique your viewers’ interest, communicate your motivation, demonstrate why your project is particularly interesting or unique.

Don’t incorporate visual aids just for the sake of having a pretty picture on your poster. The visual aids should contribute to your overall message and convey some piece of information that your viewers wouldn’t otherwise get just from reading your poster’s text.

How can I make my poster easy to read?

There are a number of tricks you can use to aid readability and emphasize crucial ideas. In general:

- Use a large font. Don’t make the text smaller in order to fit more onto the poster. Make sure that 95% of the text on your poster can be read from 4 feet away. If viewers can’t make out the text from a distance, they’re likely to walk away.

- Choose a sans-serif font like Helvetica or Verdana, not a serif font, like Times New Roman. Sans-serif fonts are easier to read because they don’t have extraneous hooks on every letter. Here is an example of a sans-serif and a serif font:

- Once you have chosen a font, be consistent in its usage. Use just one font.

- Don’t single-space your text. Use 1.5- or double-spacing to make the text easier to read.

For main points:

- Use bold, italicized, or colored fonts, or enclose text in boxes. Save this kind of emphasis for only a few key words, phrases, or sentences. Too much emphasized text makes it harder, not easier, to locate important points.

- AVOID USING ALL CAPITAL LETTERS, WHICH CAN BE HARD TO READ.

- Make your main points easy to find by setting them off with bullets or numbers.

What is my role as the presenter of my poster?

When you are standing in front of your poster, you—and what you choose to say—are as important as the actual poster. Be ready to talk about your project, answer viewers’ questions, provide additional details about your project, and so on.

How should I prepare for my presentation?

Once your poster is finished, you should re-familiarize yourself with the larger project you’re presenting. Remind yourself about those details you ended up having to leave out of the poster, so that you will be able to bring them up in discussions with viewers. Then, practice, practice, practice!

Show your poster to advisors, professors, friends, and classmates before the day of the symposium to get a feel for how viewers might respond. Prepare a four- to five-minute overview of the project, where you walk these pre-viewers through the poster, drawing their attention to the most critical points and filling in interesting details as needed. Make note of the kinds of questions these pre-viewers have, and be ready to answer those questions. You might even consider making a supplemental handout that provides additional information or answers predictable questions.

How long should I let audience members look at the poster before engaging them in discussion?

Don’t feel as if you have to start talking to viewers the minute they stop in front of your poster. Give them a few moments to read and process the information. Once viewers have had time to acquaint themselves with your project, offer to guide them through the poster. Say something like “Hello. Thanks for stopping to view my poster. Would you like a guided tour of my project?” This kind of greeting often works better than simply asking “Do you have any questions?” because after only a few moments, viewers might not have had time to come up with questions, even though they are interested in hearing more about your project.

Should I read from my poster?

No! Make sure you are familiar enough with your poster that you can talk about it without looking at it. Use the poster as a visual aid, pointing to it when you need to draw viewers’ attention to a chart, photograph, or particularly interesting point.

Sample Posters

Click on the links below to open a PDF of each sample poster.

“Quantitative Analysis of Artifacts in Volumetric DSA: The Relative Contributions of Beam Hardening and Scatter to Vessel Dropout Behind Highly Attenuating Structures” James R. Hermus, Timothy P. Szczykutowicz, Charles M. Strother, and Charles Mistretta

Departments of Medical Physics, Biomedical Engineering, and Radiology: University of Wisconsin-Madison

“Self-Care Interventions for the Management of Mouth Sores in Hematology Patients Receiving Chemotherapy” Stephanie L. Dinse and Catherine Cherwin

School of Nursing: University of Wisconsin-Madison

“Enhancing the Fluorescence of Wisconsin Infrared Phytofluor: Wi-Phy for Potential Use in Infrared Imaging” Jerad J. Simmons and Katrina T. Forest

Department of Bacteriology: University of Wisconsin-Madison

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

Learn more about how the Cal Poly Humboldt Library can help support your research and learning needs.

Stay updated at Campus Ready .

- Cal Poly Humboldt Library

- Research Guides

Creating a Research Poster

- Creating your poster step by step

- Getting Started

- Citing Images

- Creative Commons Images

- Printing options

- More Resources

Preparing your poster

There are three components to your poster session:

- Your poster

All three components should complement one another, not repeat each other.

Poster: Your poster should be an outline of your research with interesting commentary about what you learned along the way.

You: You should prepare a 10-30 second elevator pitch and a 1-2 minute lightning talk about your research. This should be a unique experience or insight you had about your research that adds depth of understanding to what the attendee can read on your poster.

Handout: Best practices for handouts - Your handout should be double-sided. The first side of the paper should include a picture of your poster (this can be in black and white or color). The second side of the handout should include your literature review, cited references, further information about your topic and your contact information.

Creating your poster by answering 3 questions:

- What is the most important and/or interesting finding from my research project?

- How can I visually share my research with conference attendees? Should I use charts, graphs, images, or a wordcloud?

- What kind of information do I need to share during my lightning talk that will complement my poster?

- *Title (at least 72 pt font).

- Research question or hypothesis (all text should be at least 24 pt font).

- Methodology. What is the research process that you used? Explain how you did your research.

- Your interview questions.

- Observations. What did you see? Why is this important?

- *Findings. What did you learn? Summarize your conclusions.

- Pull out themes in the literature and list in bullet points.

- Consider a brief narrative of what you learned - what was the most interesting/surprising part of your project?

- Interesting quotes from your research.

- Turn your data into charts or tables.

- Use images (visit the "Images" tab in the guide for more information). Take your own or legally use others.

- Recommendations and/or next steps for future research.

- You can include your list of citations on your poster or in your handout.

- *Make sure your name, and Cal Poly Humboldt University is on your poster.

*Required. Everything else is optional - you decide what is important to put on your poster. These are just suggestions. Use the tabs in this guide for more tips on how to create your poster.

Poster Sizes

You can create your poster from scratch by using PowerPoint or a similar design program.

Resize the slide to fit your needs before you begin adding any content. Standard poster sizes range from 40" by 30" and 48" by 36" but you should check with the conference organizers. If you don't resize your design at the beginning, when it is printed the image quality will be poor and pixelated if it is sized up to poster dimensions.

The standard poster sizes for ideaFest are 36" x 48" and 24" by 36".

To resize in PowerPoint, go to "File" then "Page Setup..." and enter your dimensions in the boxes for "width" and "height". Make sure to select "OK" to save your changes.

To resize in Google Slides, go to "File" then "Page setup" and select the "Custom" option in the drop down menu. Enter the dimensions for your poster size and then select "Apply" to save your changes.

Step Four: Final checklist

Final checklist for submitting your poster for printing:.

- Proofread your poster for spelling and grammar mistakes. Ask a peer to read your poster, they will catch the mistakes that you miss. Print your poster on an 8 1/2" by 11" sheet of paper - it is easier to read for mistakes and to judge your design.

- Make sure you followed Step 3 and resized your PPT slide correctly.

- Does your poster have flow? Did you "chunk" information into easily read pieces of information?

- Do your visualizations (e.g. charts, graphs, tag clouds, etc.) tell a story? Are they properly labeled and readable?

- Make sure that your images we not resized in PPT. You should use the original size of the image or try an image editor (e.g. Photoshop). Did you cite your image?

- Is your name, department, and affiliation on your poster?

- Did you want to include acknowlegments on your poster? This may be appropriate if your advisor and a graduate student provided leadership during the research process.

- Most importantly- Save your PPT slide to PDF before you send to the printer in order to avoid any printing mishaps. You should also double-check the properties to make sure it is still sized correctly in PDF.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Images >>

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Serv Res

- v.42(1 Pt 1); 2007 Feb

Preparing and Presenting Effective Research Posters

Associated data.

APPENDIX A.2. Comparison of Research Papers, Presentations, and Posters—Contents.

Posters are a common way to present results of a statistical analysis, program evaluation, or other project at professional conferences. Often, researchers fail to recognize the unique nature of the format, which is a hybrid of a published paper and an oral presentation. This methods note demonstrates how to design research posters to convey study objectives, methods, findings, and implications effectively to varied professional audiences.

A review of existing literature on research communication and poster design is used to identify and demonstrate important considerations for poster content and layout. Guidelines on how to write about statistical methods, results, and statistical significance are illustrated with samples of ineffective writing annotated to point out weaknesses, accompanied by concrete examples and explanations of improved presentation. A comparison of the content and format of papers, speeches, and posters is also provided.

Each component of a research poster about a quantitative analysis should be adapted to the audience and format, with complex statistical results translated into simplified charts, tables, and bulleted text to convey findings as part of a clear, focused story line.

Conclusions

Effective research posters should be designed around two or three key findings with accompanying handouts and narrative description to supply additional technical detail and encourage dialog with poster viewers.

An assortment of posters is a common way to present research results to viewers at a professional conference. Too often, however, researchers treat posters as poor cousins to oral presentations or published papers, failing to recognize the opportunity to convey their findings while interacting with individual viewers. By neglecting to adapt detailed paragraphs and statistical tables into text bullets and charts, they make it harder for their audience to quickly grasp the key points of the poster. By simply posting pages from the paper, they risk having people merely skim their work while standing in the conference hall. By failing to devise narrative descriptions of their poster, they overlook the chance to learn from conversations with their audience.

Even researchers who adapt their paper into a well-designed poster often forget to address the range of substantive and statistical training of their viewers. This step is essential for those presenting to nonresearchers but also pertains when addressing interdisciplinary research audiences. Studies of policymakers ( DiFranza and the Staff of the Advocacy Institute 1996 ; Sorian and Baugh 2002 ) have demonstrated the importance of making it readily apparent how research findings apply to real-world issues rather than imposing on readers to translate statistical findings themselves.

This methods note is intended to help researchers avoid such pitfalls as they create posters for professional conferences. The first section describes objectives of research posters. The second shows how to describe statistical results to viewers with varied levels of statistical training, and the third provides guidelines on the contents and organization of the poster. Later sections address how to prepare a narrative and handouts to accompany a research poster. Because researchers often present the same results as published research papers, spoken conference presentations, and posters, Appendix A compares similarities and differences in the content, format, and audience interaction of these three modes of presenting research results. Although the focus of this note is on presentation of quantitative research results, many of the guidelines about how to prepare and present posters apply equally well to qualitative studies.

WHAT IS A RESEARCH POSTER?

Preparing a poster involves not only creating pages to be mounted in a conference hall, but also writing an associated narrative and handouts, and anticipating the questions you are likely to encounter during the session. Each of these elements should be adapted to the audience, which may include people with different levels of familiarity with your topic and methods ( Nelson et al. 2002 ; Beilenson 2004 ). For example, the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association draws academics who conduct complex statistical analyses along with practitioners, program planners, policymakers, and journalists who typically do not.

Posters are a hybrid form—more detailed than a speech but less than a paper, more interactive than either ( Appendix A ). In a speech, you (the presenter) determine the focus of the presentation, but in a poster session, the viewers drive that focus. Different people will ask about different facets of your research. Some might do policy work or research on a similar topic or with related data or methods. Others will have ideas about how to apply or extend your work, raising new questions or suggesting different contrasts, ways of classifying data, or presenting results. Beilenson (2004) describes the experience of giving a poster as a dialogue between you and your viewers.

By the end of an active poster session, you may have learned as much from your viewers as they have from you, especially if the topic, methods, or audience are new to you. For instance, at David Snowdon's first poster presentation on educational attainment and longevity using data from The Nun Study, another researcher returned several times to talk with Snowdon, eventually suggesting that he extend his research to focus on Alzheimer's disease, which led to an important new direction in his research ( Snowdon 2001 ). In addition, presenting a poster provides excellent practice in explaining quickly and clearly why your project is important and what your findings mean—a useful skill to apply when revising a speech or paper on the same topic.

WRITING FOR A VARIED PROFESSIONAL AUDIENCE

Audiences at professional conferences vary considerably in their substantive and methodological backgrounds. Some will be experts on your topic but not your methods, some will be experts on your methods but not your topic, and most will fall somewhere in between. In addition, advances in research methods imply that even researchers who received cutting-edge methodological training 10 or 20 years ago might not be conversant with the latest approaches. As you design your poster, provide enough background on both the topic and the methods to convey the purpose, findings, and implications of your research to the expected range of readers.

Telling a Simple, Clear Story

Write so your audience can understand why your work is of interest to them, providing them with a clear take-home message that they can grasp in the few minutes they will spend at your poster. Experts in communications and poster design recommend planning your poster around two to three key points that you want your audience to walk away with, then designing the title, charts, and text to emphasize those points ( Briscoe 1996 ; Nelson et al. 2002 ; Beilenson 2004 ). Start by introducing the two or three key questions you have decided will be the focus of your poster, and then provide a brief overview of data and methods before presenting the evidence to answer those questions. Close with a summary of your findings and their implications for research and policy.

A 2001 survey of government policymakers showed that they prefer summaries of research to be written so they can immediately see how the findings relate to issues currently facing their constituencies, without wading through a formal research paper ( Sorian and Baugh 2002 ). Complaints that surfaced about many research reports included that they were “too long, dense, or detailed,” or “too theoretical, technical, or jargony.” On average, respondents said they read only about a quarter of the research material they receive for detail, skim about half of it, and never get to the rest.

To ensure that your poster is one viewers will read, understand, and remember, present your analyses to match the issues and questions of concern to them, rather than making readers translate your statistical results to fit their interests ( DiFranza and the Staff of the Advocacy Institute 1996 ; Nelson et al. 2002 ). Often, their questions will affect how you code your data, specify your model, or design your intervention and evaluation, so plan ahead by familiarizing yourself with your audience's interests and likely applications of your study findings. In an academic journal article, you might report parameter estimates and standard errors for each independent variable in your regression model. In the poster version, emphasize findings for specific program design features, demographic, or geographic groups, using straightforward means of presenting effect size and statistical significance; see “Describing Numeric Patterns and Contrasts” and “Presenting Statistical Test Results” below.

The following sections offer guidelines on how to present statistical findings on posters, accompanied by examples of “poor” and “better” descriptions—samples of ineffective writing annotated to point out weaknesses, accompanied by concrete examples and explanations of improved presentation. These ideas are illustrated with results from a multilevel analysis of disenrollment from the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP; Phillips et al. 2004 ). I chose that paper to show how to prepare a poster about a sophisticated quantitative analysis of a topic of interest to HSR readers, and because I was a collaborator in that study, which was presented in the three formats compared here—as a paper, a speech, and a poster.

Explaining Statistical Methods

Beilenson (2004) and Briscoe (1996) suggest keeping your description of data and methods brief, providing enough information for viewers to follow the story line and evaluate your approach. Avoid cluttering the poster with too much technical detail or obscuring key findings with excessive jargon. For readers interested in additional methodological information, provide a handout and a citation to the pertinent research paper.

As you write about statistical methods or other technical issues, relate them to the specific concepts you study. Provide synonyms for technical and statistical terminology, remembering that many conferences of interest to policy researchers draw people from a range of disciplines. Even with a quantitatively sophisticated audience, don't assume that people will know the equivalent vocabulary used in other fields. A few years ago, the journal Medical Care published an article whose sole purpose was to compare statistical terminology across various disciplines involved in health services research so that people could understand one another ( Maciejewski et al. 2002 ). After you define the term you plan to use, mention the synonyms from the various fields represented in your audience.

Consider whether acronyms are necessary on your poster. Avoid them if they are not familiar to the field or would be used only once or twice on your poster. If you use acronyms, spell them out at first usage, even those that are common in health services research such as “HEDIS®”(Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set) or “HLM”(hierarchical linear model).

Poor: “We use logistic regression and a discrete-time hazards specification to assess relative hazards of SCHIP disenrollment, with plan level as our key independent variable.” Comment: Terms like “discrete-time hazards specification” may be confusing to readers without training in those methods, which are relatively new on the scene. Also the meaning of “SCHIP” or “plan level” may be unfamiliar to some readers unless defined earlier on the poster.

Better: “Chances of disenrollment from the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) vary by amount of time enrolled, so we used hazards models (also known as event history analysis or survival analysis) to correct for those differences when estimating disenrollment patterns for SCHIP plans for different income levels.” Comment: This version clarifies the terms and concepts, naming the statistical method and its synonyms, and providing a sense of why this type of analysis is needed.

To explain a statistical method or assumption, paraphrase technical terms and illustrate how the analytic approach applies to your particular research question and data:

Poor : “The data structure can be formulated as a two-level hierarchical linear model, with families (the level-1 unit of analysis) nested within counties (the level-2 unit of analysis).” Comment: Although this description would be fine for readers used to working with this type of statistical model, those who aren't conversant with those methods may be confused by terminology such as “level-1” and “unit of analysis.”

Better: “The data have a hierarchical (or multilevel) structure, with families clustered within counties.” Comment: By replacing “nested” with the more familiar “clustered,” identifying the specific concepts for the two levels of analysis, and mentioning that “hierarchical” and “multilevel” refer to the same type of analytic structure, this description relates the generic class of statistical model to this particular study.

Presenting Results with Charts

Charts are often the preferred way to convey numeric patterns, quickly revealing the relative sizes of groups, comparative levels of some outcome, or directions of trends ( Briscoe 1996 ; Tufte 2001 ; Nelson et al. 2002 ). As Beilenson puts it, “let your figures do the talking,” reducing the need for long text descriptions or complex tables with lots of tiny numbers. For example, create a pie chart to present sample composition, use a simple bar chart to show how the dependent variable varies across subgroups, or use line charts or clustered bar charts to illustrate the net effects of nonlinear specifications or interactions among independent variables ( Miller 2005 ). Charts that include confidence intervals around point estimates are a quick and effective way to present effect size, direction, and statistical significance. For multivariate analyses, consider presenting only the results for the main variables of interest, listing the other variables in the model in a footnote and including complex statistical tables in a handout.

Provide each chart with a title (in large type) that explains the topic of that chart. A rhetorical question or summary of the main finding can be very effective. Accompany each chart with a few annotations that succinctly describe the patterns in that chart. Although each chart page should be self-explanatory, be judicious: Tufte (2001) cautions against encumbering your charts with too much “nondata ink”—excessive labeling or superfluous features such as arrows and labels on individual data points. Strive for a balance between guiding your readers through the findings and maintaining a clean, uncluttered poster. Use chart types that are familiar to your expected audience. Finally, remember that you can flesh out descriptions of charts and tables in your script rather than including all the details on the poster itself; see “Narrative to Accompany a Poster.”

Describing Numeric Patterns and Contrasts

As you describe patterns or numeric contrasts, whether from simple calculations or complex statistical models, explain both the direction and magnitude of the association. Incorporate the concepts under study and the units of measurement rather than simply reporting coefficients (β's) ( Friedman 1990 ; Miller 2005 ).

Poor: “Number of enrolled children in the family is correlated with disenrollment.” Comment: Neither the direction nor the size of the association is apparent.

Poor [version #2]: “The log-hazard of disenrollment for one-child families was 0.316.” Comment: Most readers find it easier to assess the size and direction from hazards ratios (a form of relative risk) instead of log-hazards (log-relative risks, the β's from a hazards model).

Better: “Families with only one child enrolled in the program were about 1.4 times as likely as larger families to disenroll.” Comment: This version explains the association between number of children and disenrollment without requiring viewers to exponentiate the log-hazard in their heads to assess the size and direction of that association. It also explicitly identifies the group against which one-child families are compared in the model.

Presenting Statistical Test Results

On your poster, use an approach to presenting statistical significance that keeps the focus on your results, not on the arithmetic needed to conduct inferential statistical tests. Replace standard errors or test statistics with confidence intervals, p- values, or symbols, or use formatting such as boldface, italics, or a contrasting color to denote statistically significant findings ( Davis 1997 ; Miller 2005 ). Include the detailed statistical results in handouts for later perusal.

To illustrate these recommendations, Figures 1 and and2 2 demonstrate how to divide results from a complex, multilevel model across several poster pages, using charts and bullets in lieu of the detailed statistical table from the scientific paper ( Table 1 ; Phillips et al. 2004 ). Following experts' advice to focus on one or two key points, these charts emphasize the findings from the final model (Model 5) rather than also discussing each of the fixed- and random-effects specifications from the paper.

Presenting Complex Statistical Results Graphically

Text Summary of Additional Statistical Results

Multilevel Discrete-Time Hazards Models of Disenrollment from SCHIP, New Jersey, January 1998–April 2000

| Baseline Hazard (1) | Ignoring County of Residence (2) | County Fixed Effects Model (3) | Random Effects Model Family Factors Only (4) | Random Effects Model Family + County Factors (5) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | LRH | SE | LRH | SE | LRH | SE | LRH | SE | LRH | SE |

| Intercept | −4.327 | (0.049) | −5.426 | (0.140) | −5.581 | (0.159) | −5.421 | (0.142) | −5.455 | (0.159) |

| Family-level characteristics | ||||||||||

| Months enrolled | 0.072 | (0.012) | 0.018 | (0.034) | 0.018 | (0.034) | 0.018 | (0.034) | 0.018 | (0.034) |

| Months enrolled-squared | −0.0008 | (0.0007) | 0.0046 | (0.002) | 0.0046 | (0.002) | 0.0046 | (0.002) | 0.0046 | (0.002) |

| Black race | 0.016 | (0.149) | 0.047 | (0.150) | 0.038 | (0.149) | 0.198 | (0.165) | ||

| Hispanic race | 0.091 | (0.062) | 0.121 | (0.064) | 0.109 | (0.063) | 0.124 | (0.064) | ||

| Plans C and D (ref =Plan B) | 0.819 | (0.142) | 0.826 | (0.142) | 0.823 | (0.142) | 0.825 | (0.142) | ||

| One enrolled child | 0.313 | (0.038) | 0.317 | (0.038) | 0.316 | (0.037) | 0.316 | (0.038) | ||

| #Infants | −0.555 | (0.168) | −0.562 | (0.168) | −0.555 | (0.168) | −0.550 | (0.168) | ||

| #1–4 year olds | 0.174 | (0.028) | 0.165 | (0.028) | 0.167 | (0.028) | 0.166 | (0.028) | ||

| Spanish with some English | −0.152 | (0.068) | −0.136 | (0.069) | −0.144 | (0.069) | −0.139 | (0.069) | ||

| Spanish with no English | 0.015 | (0.146) | 0.0092 | (0.146) | 0.0084 | (0.146) | 0.013 | (0.146) | ||

| Interactions | ||||||||||

| Black × plans C/D | 0.461 | (0.154) | 0.449 | (0.154) | 0.456 | (0.154) | 0.451 | (0.154) | ||

| Plans C/D × months | 0.078 | (0.036) | 0.078 | (0.036) | 0.078 | (0.036) | 0.077 | (0.036) | ||

| Plans C/D × months squared | −0.0069 | (0.0019) | −0.0069 | (0.0019) | −0.0069 | (0.0019) | −0.0068 | (0.0019) | ||

| County-level characteristics | ||||||||||

| KidCare provider density | −0.019 | (0.007) | ||||||||

| % Poor | 0.0054 | (0.005) | ||||||||

| % Black physicians | 0.007 | (0.012) | ||||||||

| Cross-level interaction | ||||||||||

| Black ×% black physicians | −0.039 | (0.019) | ||||||||

| Random effects | ||||||||||

| Between-county variance | 0.016 | (0.009) | 0.012 | (0.007) | 0.005 | (0.006) | ||||

| Scaled deviance statistic | 31,432.4 | 30,877.6 | 30,824.5 | 30,948.4 | 30,895.4 | |||||

Source : Phillips et al. (2004) .

SCHIP, State Children's Health Insurance Program; LRH, log relative-hazard; SE, standard error.

Figure 1 uses a chart (also from the paper) to present the net effects of a complicated set of interactions between two family-level traits (race and SCHIP plan) and a cross-level interaction between race of the family and county physician racial composition. The title is a rhetorical question that identifies the issue addressed in the chart, and the annotations explain the pattern. The chart version substantially reduces the amount of time viewers need to understand the main take-home point, averting the need to mentally sum and exponentiate several coefficients from the table.

Figure 2 uses bulleted text to summarize other key results from the model, translating log-relative hazards into hazards ratios and interpreting them with minimal reliance on jargon. The results for family race, SCHIP plan, and county physician racial composition are not repeated in Figure 2 , averting the common problem of interpreting main effect coefficients and interaction coefficients without reference to one another.

Alternatively, replace the text summary shown in Figure 2 with Table 2 —a simplified version of Table 1 which presents only the results for Model 5, replaces log-relative hazards with hazards ratios, reports associated confidence intervals in lieu of standard errors, and uses boldface to denote statistical significance. (On a color slide, use a contrasting color in lieu of bold.)

Relative Risks of SCHIP Disenrollment for Other * Family and County Characteristics, New Jersey, January 1998–April 2000

| Relative Risk (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Family-level characteristics | |

| One enrolled child (ref. =2 + children) | |

| Ages of children | |

| # Infants | |

| # 1–4 year olds | |

| Language spoken at home (ref. =English) | |

| Spanish with some English | 0.87 (0.76–1.00) |

| Spanish with no English | 1.01 (0.76–1.35) |

| County-level characteristics | |

| KidCare provider density (providers/mile ) | |

| % Poor | |

Statistically significant associations are shown in bold.

Based on hierarchical linear model controlling for months enrolled, months-squared, race, SCHIP plan, county physician racial composition, and all variables shown here. Scaled deviance =30,895. Random effects estimate for between-county variance =0.005 (standard error =0.006). SCHIP, State Children's Health Insurance Program; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

CONTENTS AND ORGANIZATION OF A POSTER

Research posters are organized like scientific papers, with separate pages devoted to the objectives and background, data and methods, results, and conclusions ( Briscoe 1996 ). Readers view the posters at their own pace and at close range; thus you can include more detail than in slides for a speech (see Appendix A for a detailed comparison of content and format of papers, speeches, and posters). Don't simply post pages from the scientific paper, which are far too text-heavy for a poster. Adapt them, replacing long paragraphs and complex tables with bulleted text, charts, and simple tables ( Briscoe 1996 ; Beilenson 2004 ). Fink (1995) provides useful guidelines for writing text bullets to convey research results. Use presentation software such as PowerPoint to create your pages or adapt them from related slides, facilitating good page layout with generous type size, bullets, and page titles. Such software also makes it easy to create matching handouts (see “Handouts”).

The “W's” (who, what, when, where, why) are an effective way to organize the elements of a poster.

- In the introductory section, describe what you are studying, why it is important, and how your analysis will add to the existing literature in the field.

- In the data and methods section of a statistical analysis, list when, where, who, and how the data were collected, how many cases were involved, and how the data were analyzed. For other types of interventions or program evaluations, list who, when, where, and how many, along with how the project was implemented and assessed.

- In the results section, present what you found.

- In the conclusion, return to what you found and how it can be used to inform programs or policies related to the issue.

Number and Layout of Pages

To determine how many pages you have to work with, find out the dimensions of your assigned space. A 4′ × 8′ bulletin board accommodates the equivalent of about twenty 8.5″ × 11″ pages, but be selective—no poster can capture the full detail of a large series of multivariate models. A trifold presentation board (3′ high by 4′ wide) will hold roughly a dozen pages, organized into three panels ( Appendix B ). Breaking the arrangement into vertical sections allows viewers to read each section standing in one place while following the conventions of reading left-to-right and top-to-bottom ( Briscoe 1996 ).

- At the top of the poster, put an informative title in a large, readable type size. On a 4′ × 8′ bulletin board, there should also be room for an institutional logo.

Suggested Layout for a 4′ × 8′ poster.

- In the left-hand panel, set the stage for the research question, conveying why the topic is of policy interest, summarizing major empirical or theoretical work on related topics, and stating your hypotheses or project aims, and explaining how your work fills in gaps in previous analyses.

- In the middle panel, briefly describe your data source, variables, and methods, then present results in tables or charts accompanied by text annotations. Diagrams, maps, and photographs are very effective for conveying issues difficult to capture succinctly in words ( Miller 2005 ), and to help readers envision the context. A schematic diagram of relationships among variables can be useful for illustrating causal order. Likewise, a diagram can be a succinct way to convey timing of different components of a longitudinal study or the nested structure of a multilevel dataset.

- In the right-hand panel, summarize your findings and relate them back to the research question or project aims, discuss strengths and limitations of your approach, identify research, practice, or policy implications, and suggest directions for future research.