How to Identify Yourself in an Essay: Exploring Self-Identity in Writing

- by Brandon Thompson

- October 18, 2023

Writing an essay about oneself can be a daunting task. How do you capture the essence of who you are in just a few words or pages? How do you define yourself in a way that is both authentic and engaging? In this blog post, we will dive into the art of self-identification in essay writing, providing you with tips, insights, and examples to help you craft a compelling narrative about your own identity.

Whether you’re facing the challenge of answering questions like “How do you define yourself?” or “What makes up your identity?” or struggling with how to discuss yourself without using the first-person pronoun, we’ll guide you through the process step by step. We will explore various techniques for writing a self-identity essay, such as using reflection, describing your social identity, and introducing yourself in a creative way.

So grab a pen and paper, or open up that blank document, as we journey together to discover how to effectively identify yourself in an essay – a reflection of who you are in this ever-evolving world of 2023.

How to Identify Yourself in an Essay: Let Your Words Shine!

When it comes to writing an essay, one of the most important aspects is identifying yourself and expressing your unique voice. After all, no one wants to read a dull and lifeless piece of writing! So, how can you make sure your essay stands out? Let’s dive in and explore some tips on how you can identify yourself effectively in your writing.

Find Your Writing Persona

Just like superheroes have alter egos, writers too have their own personas. Embrace your inner writer and let your personality shine through your words! Whether you’re witty, introspective, or even a bit sarcastic, infusing your essay with your authentic voice will make it engaging and relatable. Don’t be afraid to show some personality – after all, who said essays have to be boring?

Inject Some Humor

Who says essays can’t be entertaining? Injecting humor into your writing can captivate your readers and make your essay stand out from the crowd. Of course, don’t force it or try too hard to be funny; instead, lightheartedly sprinkle in some jokes or clever anecdotes that relate to your topic. A humorous tone can make your essay more enjoyable to read while still conveying your thoughts effectively.

Reflect Your Unique Perspectives

We all have our own perspectives and experiences that shape the way we view the world. Use your essay as an opportunity to showcase your unique point of view. Whether you’re tackling a philosophical question or exploring a personal experience, don’t be afraid to express your thoughts and feelings authentically. Remember, your perspective is what sets your essay apart.

Play with Structure

While essays typically have a formal structure, that doesn’t mean you can’t play around with it a little. Use subheadings, bullet points, or even numbered lists to organize your thoughts and make the reading experience more enjoyable. Breaking up your content into smaller, digestible sections makes it easier for your readers to follow along and keeps them engaged from start to finish.

Dare to Be Different

Everyone loves a fresh perspective, so dare to be different in your writing. Challenge conventional ideas or take a unique stance on a topic. By offering a fresh take or a creative spin, you’ll leave a lasting impression on your readers. Remember, the goal is not to conform but to stand out and be memorable.

Embrace Your Quirkiness

We all have our quirks, so don’t be afraid to let them shine in your essay. Whether it’s an unusual hobby, a unique talent, or a peculiar fascination, incorporating your quirks into your writing can make it more interesting and authentic. By embracing your individuality, you’ll create a personal connection with your readers and leave a lasting impact.

In conclusion, when it comes to identifying yourself in an essay, the key is to be genuine, entertaining, and captivating. Let your writing persona shine, inject some humor, reflect your unique perspectives, play with structure, dare to be different, and embrace your quirkiness. By following these tips, you’ll not only create an essay that stands out but also enjoy the process of writing and expressing yourself. So, grab your pen and let your words do the talking!

FAQ: How do you identify yourself in an essay?

How do you answer what defines you.

In an essay, when asked what defines you, it’s important to delve deep into your values, beliefs, experiences, and passions. Reflecting on your unique qualities and characteristics will help you provide an authentic and meaningful response. Remember, you are more than just a list of accomplishments or titles – you are the sum of your values and experiences.

How do you write a self-identity essay

Writing a self-identity essay can be both challenging and liberating. Start by introspecting and reflecting on your identity – the cultural, social, and personal influences that shape you. Then, craft a compelling narrative that showcases your journey of self-discovery. Share anecdotes, milestones, and experiences that have contributed to your growth and sense of self.

How can I define myself

Defining oneself is like peeling an onion – layer by layer, you discover who you truly are. Embrace introspection and explore your passions, values, strengths, and weaknesses. Look beyond external expectations and societal norms. Remember, it’s a lifelong process, and it often takes time and self-reflection to truly understand and define yourself.

What is an identity example

Identity is as unique as a fingerprint, and each person’s identity is formed by a combination of factors. For example, an identity can be shaped by cultural heritage, such as being a proud Latina or a devoted fan of Korean pop music. It can also be influenced by personal traits, such as being an adventurous thrill-seeker or a compassionate and empathetic friend. Ultimately, identity is the intricate tapestry that makes each person who they are.

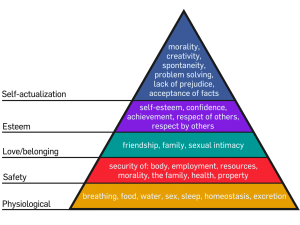

What makes up a person’s identity essay

A person’s identity essay encompasses various aspects that contribute to their sense of self. These include cultural background , beliefs, values, interests, experiences, and relationships. It is the fusion of these elements that shapes a person’s unique identity and makes them the individual they are.

How do you write an identity statement

Crafting an identity statement is like capturing the essence of who you are in a concise and powerful sentence. Start by reflecting on the core values, passions, and qualities that define you. Then, articulate these elements into a clear and compelling statement that encapsulates your identity. Be authentic, genuine, and unafraid to showcase what makes you extraordinary.

How do you make a new identity for yourself

Making a new identity for yourself can be both exciting and challenging. Start by identifying the changes you want to make, whether it’s adopting new habits, exploring new interests, or reassessing your values. Embrace personal growth, surround yourself with supportive individuals, and be open to new experiences. Remember, creating a new identity is a journey, and it takes time, effort, and self-reflection.

How do you write a few lines about yourself

When writing a few lines about yourself, it’s important to strike a balance between showcasing your unique qualities and maintaining brevity. Highlight your key accomplishments, interests, and passions. Inject a touch of humor, if appropriate, to engage your readers. Remember, the goal is to leave a lasting impression and pique curiosity about the person behind those few lines.

How do you define yourself reflection

Defining yourself through reflection involves introspection and analyzing your thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Take the time to understand your values, strengths, weaknesses, and aspirations. Explore how your past experiences have shaped you and consider how you want to grow in the future. Through reflection, you can gain a deeper understanding of yourself and thereby define your identity.

How would you describe your social identity

Describing social identity involves considering how you relate to different social groups and communities. It encompasses aspects such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, and socioeconomic background. When describing your social identity, you may discuss the intersectionality of these various facets and how they influence your perspective, experiences, and interactions within society.

What makes up your identity

Your identity is an intricate tapestry woven from various threads that make you unique. It comprises elements such as your cultural background, personal values, experiences, relationships, and aspirations. It is the combination of these factors that gives you a distinct identity, shaping your beliefs, actions, and overall sense of self.

How do you talk about yourself in an essay without using “I”

Crafting an essay about yourself without relying heavily on the pronoun “I” requires creativity and alternative perspectives. Instead of constantly using “I,” focus on sharing specific experiences, achievements, or insights. Use descriptive language to engage your readers and help them visualize your narrative. By varying sentence structures and utilizing storytelling techniques, you can effectively convey your unique story without relying solely on “I.”

How would you describe yourself in one sentence

In one sentence, I am a curious wanderer, forever seeking adventures, embracing new experiences, and finding joy in the simple moments of life.

What is meant by self-identity

Self-identity refers to the recognition, understanding, and acceptance of one’s own unique characteristics, values, and beliefs. It is a journey of self-discovery that involves introspection, reflection, and a deep connection with one’s true self. Self-identity allows individuals to define who they are and navigate their lives authentically.

How would you describe yourself in a college essay

Describing oneself in a college essay requires striking a delicate balance between showcasing personal qualities and demonstrating suitability for academic pursuits . Be authentic and genuine, highlighting your unique traits, experiences, and ambitions. Emphasize your academic achievements, extracurricular involvements, and personal growth. However, remember to let your personality shine through your writing, engaging the readers with your unique voice.

How do I identify myself example

An example of identifying oneself could be acknowledging oneself as an adventurous explorer who finds solace in nature, a compassionate listener who provides comfort to others, or an analytical thinker who thrives in problem-solving. Identifying oneself involves understanding and embracing personal traits and qualities that make each person unique.

How do you introduce yourself in a class essay

When introducing yourself in a class essay, start with a captivating anecdote or a thought-provoking question related to the topic. Provide a brief overview of your background, emphasizing experiences or interests relevant to the class. Establish credibility while showcasing enthusiasm and curiosity for the subject matter. Engage the reader from the start to set the tone for an engaging essay.

What are 5 important parts of your identity

Five important parts of one’s identity may include cultural background, personal values, aspirations, relationships, and experiences. These elements shape who we are, influence our decision-making, and provide a lens through which we view the world. Each individual’s identity is unique, comprising an intricate web of multifaceted components.

How do you introduce yourself in academic writing

In academic writing, introducing yourself should be done succinctly and professionally. Start with your full name, followed by your current academic affiliation, such as the university or institution you attend. If applicable, mention your area of study or research interests in a concise manner. Avoid unnecessary personal details and maintain a confident and polished tone throughout your introduction.

What is your identity as a student

As a student, your identity extends beyond being a mere participant in academic pursuits. It encompasses your intellectual curiosity, enthusiasm for learning, and dedication to personal growth. Your identity as a student is shaped by how you navigate challenges, collaborate with peers, and actively engage in the pursuit of knowledge. Embrace this multifaceted identity as a student, allowing it to empower and guide you on your academic journey.

How do you identify yourself meaning

Identifying yourself is about recognizing and defining your unique qualities, values, beliefs, and experiences. It involves understanding how these elements shape your perspective, actions, and life choices. By acknowledging and embracing your identity, you gain a sense of self-awareness, enabling personal growth and an authentic connection with others.

How do you introduce yourself in writing examples

Hello, fellow readers! I’m Jane, a passionate storyteller with a penchant for adventure. Whether lost in the pages of a book or exploring the great outdoors, I find solace in embracing new worlds and acquiring fresh perspectives.

Greetings, everyone! I’m John, a coffee-fueled wordsmith on a perpetual quest for knowledge. When I’m not decoding complex theories at my laptop, you can find me immersing myself in the creative realms of photography or scouring the city for the perfect cup of joe.

How do you introduce yourself in a creative essay

In a creative essay, the introduction is your chance to make a memorable first impression. Craft an opening that hooks the reader and sets the tone for your creative exploration. Utilize vivid descriptions, figurative language, or an intriguing anecdote that illuminates your unique perspective. Take the reader on a journey, introducing yourself as a protagonist in your own story, ready to embark on an adventure of self-expression.

How do you introduce yourself as a student

As a student, introducing yourself is an opportunity to showcase your enthusiasm for learning and to connect with your peers. Share your name, grade or year level, and a personal interest or hobby that reflects your individuality. Consider mentioning your academic goals and aspirations, highlighting your determination to excel. Be approachable, friendly, and open to forging new connections in the student community.

- cultural background

- essay writing

- experiences

- individuality

- interesting

- self-identity essay

- unique perspectives

- unique qualities

- unique voice

Brandon Thompson

How many regis are there unveiling the secrets of regice, registeel, regirock, and more, who is ennard soul unveiling the mysteries of fnaf's intriguing character, you may also like, the 555 practice: a spiritual awakening journey.

- by Thomas Harrison

- October 31, 2023

Who is the Biological Father of Fredrik Eklund’s Twins?

- by Daniel Taylor

- October 30, 2023

Why is Venom Scared of Sound?

- October 11, 2023

Is it Illegal to Own a Crow Skull?

- by Donna Gonzalez

- November 2, 2023

Naruto’s Maturation Journey in Shippuden: Does the Beloved Shinobi Grow Up?

- November 3, 2023

Why Does Eri Look Like Shigaraki? Explained

- by Laura Rodriguez

- October 7, 2023

Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- College essay

How to Write About Yourself in a College Essay | Examples

Published on September 21, 2021 by Kirsten Courault . Revised on May 31, 2023.

An insightful college admissions essay requires deep self-reflection, authenticity, and a balance between confidence and vulnerability. Your essay shouldn’t just be a resume of your experiences; colleges are looking for a story that demonstrates your most important values and qualities.

To write about your achievements and qualities without sounding arrogant, use specific stories to illustrate them. You can also write about challenges you’ve faced or mistakes you’ve made to show vulnerability and personal growth.

Table of contents

Start with self-reflection, how to write about challenges and mistakes, how to write about your achievements and qualities, how to write about a cliché experience, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about college application essays.

Before you start writing, spend some time reflecting to identify your values and qualities. You should do a comprehensive brainstorming session, but here are a few questions to get you started:

- What are three words your friends or family would use to describe you, and why would they choose them?

- Whom do you admire most and why?

- What are the top five things you are thankful for?

- What has inspired your hobbies or future goals?

- What are you most proud of? Ashamed of?

As you self-reflect, consider how your values and goals reflect your prospective university’s program and culture, and brainstorm stories that demonstrate the fit between the two.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing about difficult experiences can be an effective way to show authenticity and create an emotional connection to the reader, but choose carefully which details to share, and aim to demonstrate how the experience helped you learn and grow.

Be vulnerable

It’s not necessary to have a tragic story or a huge confession. But you should openly share your thoughts, feelings, and experiences to evoke an emotional response from the reader. Even a cliché or mundane topic can be made interesting with honest reflection. This honesty is a preface to self-reflection and insight in the essay’s conclusion.

Don’t overshare

With difficult topics, you shouldn’t focus too much on negative aspects. Instead, use your challenging circumstances as a brief introduction to how you responded positively.

Share what you have learned

It’s okay to include your failure or mistakes in your essay if you include a lesson learned. After telling a descriptive, honest story, you should explain what you learned and how you applied it to your life.

While it’s good to sell your strengths, you also don’t want to come across as arrogant. Instead of just stating your extracurricular activities, achievements, or personal qualities, aim to discreetly incorporate them into your story.

Brag indirectly

Mention your extracurricular activities or awards in passing, not outright, to avoid sounding like you’re bragging from a resume.

Use stories to prove your qualities

Even if you don’t have any impressive academic achievements or extracurriculars, you can still demonstrate your academic or personal character. But you should use personal examples to provide proof. In other words, show evidence of your character instead of just telling.

Many high school students write about common topics such as sports, volunteer work, or their family. Your essay topic doesn’t have to be groundbreaking, but do try to include unexpected personal details and your authentic voice to make your essay stand out .

To find an original angle, try these techniques:

- Focus on a specific moment, and describe the scene using your five senses.

- Mention objects that have special significance to you.

- Instead of following a common story arc, include a surprising twist or insight.

Your unique voice can shed new perspective on a common human experience while also revealing your personality. When read out loud, the essay should sound like you are talking.

If you want to know more about academic writing , effective communication , or parts of speech , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Academic writing

- Writing process

- Transition words

- Passive voice

- Paraphrasing

Communication

- How to end an email

- Ms, mrs, miss

- How to start an email

- I hope this email finds you well

- Hope you are doing well

Parts of speech

- Personal pronouns

- Conjunctions

First, spend time reflecting on your core values and character . You can start with these questions:

However, you should do a comprehensive brainstorming session to fully understand your values. Also consider how your values and goals match your prospective university’s program and culture. Then, brainstorm stories that illustrate the fit between the two.

When writing about yourself , including difficult experiences or failures can be a great way to show vulnerability and authenticity, but be careful not to overshare, and focus on showing how you matured from the experience.

Through specific stories, you can weave your achievements and qualities into your essay so that it doesn’t seem like you’re bragging from a resume.

Include specific, personal details and use your authentic voice to shed a new perspective on a common human experience.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Courault, K. (2023, May 31). How to Write About Yourself in a College Essay | Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/college-essay/write-about-yourself/

Is this article helpful?

Kirsten Courault

Other students also liked, style and tone tips for your college essay | examples, what do colleges look for in an essay | examples & tips, how to make your college essay stand out | tips & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Essays About Myself: Top 5 Essay Examples Plus Prompts

We are all unique individuals, each with traits, skills, and qualities we should be proud of. Here are examples and prompts on essays about myself .

It is good to reflect on ourselves from time to time. When applying for university or a new job, you may be asked to write about yourself to give the institution a better picture of yourself. Self-understanding and reflection are essential if you want to make a compelling argument for yourself.

Reflect on your life: look back on the people you’ve met, the places you’ve been, and the experiences you’ve had, and think about how they have shaped you into the person you have become today. Think of the bigger picture and be sure to consider who you are based on what others think and say about you, not just who you think you are.

If you are tasked with the prompt, “essays about myself,” keep reading to see some essay examples.

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

1. It’s My Life by Ann Smith

2. how i see myself by leticia woods, 3. the truth about myself by madeline dyer, 4. what we see in others is a reflection of ourselves by sandra brossman, 5. a letter to myself by gladys mclaughlin, 1. introducing yourself, 2. describing your strengths and weaknesses, 3. what sets you apart from others, 4. your beliefs and values, 5. an experience that has defined you as a person, 6. what family means to you, 7. your favorite pasttime.

“Sure, I’ve had bad experiences in my life too, but this is exactly what made me the way I am now: grateful, full of love, with a desire to study well because it will help me become a successful person in future and have a high quality of life. I believe that it is manifesting day by day and I feel even more responsibility for what I do and where I go. With all I already have, I know that I’m on the right path and I will do my best to inspire others to live the way they feel like living as well.”

In her essay, Smith describes her interests, habits, and qualities. She writes that she is sociable, enthusiastic about studying, and friendly. She also touches on others’ opinions of her- that she is funny. One of Smith’s hobbies is photography, which allowed her to meet her best friend. She aims to study hard so she can be successful on whatever path she may follow, and inspire others to live their best life.

“It is this drive that will carry me through my degree program and allow me to absorb the education that I receive and develop solid practical applications from this knowledge. I feel that I will eventually become highly successful in my chosen field because my past has clearly shown my commitment to excellence in every endeavor that I have chosen. Because I remain incredibly focused and committed for future success, I know that my future will be as rewarding as my past.”

Woods discusses how her identity helps her achieve her career goals. First, her commitment to her education is a great asset. Second, prior education and her service in the US Air Force allowed her to learn much about life, the world, and herself, and she was able to learn about different cultures. She believes that experience, devotion, and knowledge will allow her to achieve her dreams.

“I’m getting better as I recover from the brain inflammation which caused my OCD, but I want to have a day like that. A day where I can relax and enjoy life fully again. A day where I haven’t a care in the world. And for that, I need to be kind to myself. I need to relax and remove any pressure I place on myself.”

Dyer reflects on an important part of herself- her Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Brain inflammation has made her a perfectionist, and she cannot relax. She is constantly compelled by an inner voice to do things she “should” be doing. She wants to be happy, and will try to shut off this voice by practicing self-affirmation. You might also be interested in these essays about discovering yourself .

“Believe it or not, forgiving YOURSELF is the most effective way to disengage from negative interactions with people. We can only love and accept others to the degree that we love and accept ourselves. When you make it a habit to learn from your relationships, eventually you will discover that you can observe negative traits within others without judgment and without getting hooked into someone else’s drama.”

In her essay, Brossman writes how we see what we desire for ourselves in others. Our relationships help us understand ourselves better; we see people’s bad qualities and criticize them, professing that we will not be like them. On the other hand, we see qualities we like and try to imitate them. To become a better version of yourself, you should learn from your relationships and emulate desirable qualities.

“I never tell anyone that I am tired of work or study. Success will come to those who get up and go far. This is my life motto which always reminds me of how vital it is to be hard-working and resilient towards failures. I learn that no matter what others say (even mother and father) if their

thoughts contradict my goals, I don’t have to listen to them. Nobody will live your life, and nobody should tell you who you are and what you are.”

Mclaughlin writes a letter to her future self, explaining what she envisions for herself in the coming years. She writes about who she is now and describes her vision for how much better she will be in the future. She believes that she will have great encounters that will teach her about life, a loving, kind family, and an independent spirit that will triumph over all her struggles

Writing Prompts For Essays About Myself

Write a basic description of yourself; describe where you live, your school or job, and your family and friends. You should also give readers a glimpse of your personality- are you outgoing, shy, or sporty? If you want to write more, you can also briefly explain your hobbies, interests, and skills.

Each of us has our own strengths and weaknesses. Reflect on what you are good at and what you can improve on and select 1-2 from each to write about. Discuss what you can do to work on your weaknesses and improve yourself.

An essential part of yourself is your uniqueness; for a strong essay about “myself,” think about beliefs, qualities, or values that set you apart from others. Write about one or more, but be sure to explain your choices clearly. You can write about what separates you in the context of your family, friend group, culture, or even society as a whole.

Your beliefs and values are at the core of your being, as they guide the decisions you make every day. Discuss some of your basic beliefs and values and explain why they are important to you. For a stronger essay, be sure to explain how you use these in day-to-day life; give concrete examples of situations in which these beliefs and values are used.

We are all shaped by our past experiences. Reflect on an experience, whether that be an achievement, setback, or just a fun memory, and explain its significance to you. Retell the story in detail and describe how it has impacted you and helped make you the person you are today.

More often than not, family plays a big role in forming us. To give readers a better idea of your identity, describe your idea of family. Discuss its significance, impact, and role in your life. You may also choose to write about how your family has helped shape you into who you are. This should be based on personal experience; refrain from using external sources to inspire you.

Our likes and dislikes are an important part of who we are as well; in your essay, discuss a hobby of yours, preferably one you have been interested in for a long period of time, and explain why you enjoy it so much. You should also write about how it has helped you become yourself and made you a better person.

Grammarly is one of our top grammar checkers. Find out why in this Grammarly review . If you’re stuck picking your next essay topic, check out our round-up of essay topics about education .

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Self and identity.

- Sanaz Talaifar Sanaz Talaifar Department of Psychology, University of Texas at Austin

- and William Swann William Swann Department of Psychology, University of Texas

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.242

- Published online: 28 March 2018

Active and stored mental representations of the self include both global and specific qualities as well as conscious and nonconscious qualities. Semantic and episodic memory both contribute to a self that is not a unitary construct comprising only the individual as he or she is now, but also past and possible selves. Self-knowledge may overlap more or less with others’ views of the self. Furthermore, mental representations of the self vary whether they are positive or negative, important, certain, and stable. The origins of the self are also manifold and can be considered from developmental, biological, intrapsychic, and interpersonal perspectives. The self is connected to core motives (e.g., coherence, agency, and communion) and is manifested in the form of both personal identities and social identities. Finally, just as the self is a product of proximal and distal social forces, it is also an agent that actively shapes its environment.

- self-concept

- self-representation

- self-knowledge

- self-perception

- self-esteem

- personal identity

- social identity

Introduction

The concept of the self has beguiled—and frustrated—psychologists and philosophers alike for generations. One of the greatest challenges has been coming to terms with the nature of the self. Every individual has a self, yet no two selves are the same. Some aspects of the self create a sense of commonality with others whereas other aspects of the self set it apart. The self usually provides a sense of consistency, a sense that there is some connection between who a person was yesterday and who they are today. And yet, the self is continually changing both as an individual ages and he or she traverses different social situations. A further conundrum is that the self acts as both subject and object; it does the knowing about itself. With so many complexities, coupled with the fact that people can neither see nor touch the self, the construct may take on an air of mysticism akin to the concept of the soul (Epstein, 1973 ).

Perhaps the most pressing, and basic, question psychologists must answer regarding the self is “What is it?” For the man whom many regard as the father of modern psychology, William James, the self was a source of continuity that gave individuals a sense of “connectedness” and “unbrokenness” ( 1890 , p. 335). James distinguished between two components of the self: the “I” and the “me” ( 1910 ). The “I” is the self as agent, thinker, and knower, the executive function that experiences and reacts to the world, constructing mental representations and memories as it does so (Swann & Buhrmester, 2012 ). James was skeptical that the “I” was amenable to scientific study, which has been borne out by the fact that far more attention has been accorded to the “me.” The “me” is the individual one recognizes as the self, which for James included a material, social, and spiritual self. The material self refers to one’s physical body and one’s physical possessions. The social self refers to the various selves one may express and others may recognize depending on the social setting. The spiritual self refers to the enduring core of one’s being, including one’s values, personality, beliefs about the self, etc.

This article focuses on the “me” that will be referred to interchangeably as either the “self” or “identity.” We define the self as a multifaceted, dynamic, and temporally continuous set of mental self-representations. These representations are multifaceted in the sense that different situations may evoke different aspects of the self at different times. They are dynamic in that they are subject to change in the form of elaborations, corrections, and reevaluations (Diehl, Youngblade, Hay, & Chui, 2011 ). This is true when researchers think of the self as a sort of scientific theory in which new evidence about the self from the environment leads to adjustments to one’s self-theory (Epstein, 1973 ; Gopnick, 2003 ). It is also true when researchers consider the self as a narrative that can be rewritten and revised (McAdams, 1996 ). Finally, self-representations are temporally continuous because even though they change, most people have a sense of being the same person over time. Further, these self-representations, whether conscious or not, are essential to psychological functioning, as they organize people’s perceptions of their traits, preferences, memories, experiences, and group memberships. Importantly, representations of the self also guide an individual’s behavior.

Some psychologists (e.g., behaviorists and more recently Brubaker & Cooper, 2000 ) have questioned the need to implicate a construct as nebulous as the self to explain behavior. Certainly an individual can perform many complex actions without invoking his or her self-representations. Nevertheless, psychologists increasingly regard the self as one of the most important constructs in all of psychology. For example, the percentage of self-related studies published in the field’s leading journal, the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , increased fivefold between 1972 and 2002 (Swann & Seyle, 2005 ) and has continued to grow to this day. The importance of the self becomes evident when one considers the consequences of a sense of self that is interrupted, damaged, or absent. Epstein ( 1973 ) offers a case in point with an example of a schizophrenic girl meeting her psychiatrist:

Ruth, a five year old, approached the psychiatrist with “Are you the bogey man? Are you going to fight my mother? Are you the same mother? Are you the same father? Are you going to be another mother?” and finally screaming in terror, “I am afraid I am going to be someone else.” [Bender, 1950 , p. 135]

To provide a more commonplace example, children do not display several emotions we consider uniquely human, such as empathy and embarrassment, until after they have developed a sense of self-awareness (Lewis, Sullivan, Stanger, & Weiss, 1989 ). As Darwin has argued ( 1872 / 1965 ), emotions like embarrassment exist only after one has a developed a sense of self that can be the object of others’ attention.

The self’s importance also is evident when one considers that it is a pancultural phenomenon; all individuals have a sense of self regardless of where they are born. Though the content of self-representations may vary by cultural context, the existence of the self is universal. So too is the structure of the self. One of the most basic structural dimensions of the self involves whether the knowledge is active or stored.

Forms of Self-Knowledge

Active and stored self-knowledge.

Although i ndividuals accumulate immeasurable amounts of knowledge over their lifespans, at any given moment they can access only a portion of that knowledge. The aspects of self-knowledge held in consciousness make up “active self-knowledge.” Other terms for active self-knowledge are the working self-concept (Markus & Kunda, 1986 ), the spontaneous self-concept (McGuire, McGuire, Child, & Fujioka, 1978 ), and the phenomenal self (Jones & Gerard, 1967 ). On the other hand, “stored self-knowledge” is information held in memory that one can access and retrieve but is not currently held in consciousness. Because different features of the self are active versus stored at different times depending on the demands of the situation, the self can be quite malleable without eliciting feelings of inconsistency or inauthenticity (Swann, Bosson, & Pelham, 2002 ).

Semantic and Episodic Representations of Self-Knowledge

People possess both episodic and semantic representations of themselves (Klein & Loftus, 1993 ; Tulving, 1983 ). Episodic self-representations refer to “behavioral exemplars” or relatively brief “cartoons in the head” involving one’s past life and experiences. For philosopher John Locke, the self was built of episodic memory. For some researchers interested in memory and identity, episodic memory has been of particular interest because it is thought to involve re-experiencing events from one’s past, providing a person with content through which to construct a personal narrative (see, e.g., Eakin, 2008 ; Fivush & Haden, 2003 ; Klein, 2001 ; Klein & Gangi, 2010 ). Recall of these episodic instances happens together with the conscious awareness that the events actually occurred in one’s life (e.g., Suddendorf & Corballis, 1997 ).

Episodic self-knowledge may shed light on the individual’s traits or preferences and how he or she will or should act in the future, but some aspects of self-knowledge do not require recalling any specific experiences. Semantic self-knowledge involves memories at a higher level abstraction. These self-related memories are based on either facts (e.g., I am 39 years old) or traits and do not necessitate remembering a specific event or experience (Klein & Lax, 2010 ; Klein, Robertson, Gangi, & Loftus, 2008 ). Thus, one may consider oneself intelligent (semantic self-knowledge) without recalling that he or she achieved stellar grades the previous term (episodic self-knowledge). In fact, Tulving ( 1972 ) suggested that the two types of knowledge may be structurally and functionally independent of each other. In support of this, case studies show that damage to the episodic self-knowledge system does not necessarily result in impairment of the semantic self-knowledge system. Evaluating semantic traits for self-descriptiveness is associated with activation in brain regions implicated in semantic, but not episodic, memory. In addition, priming a trait stored in semantic memory does not facilitate recall of corresponding episodic memories that exemplify the semantic self-knowledge (Klein, Loftus, Trafton, & Fuhrman, 1992 ). The tenuous relationship between episodic and semantic self-knowledge suggests that only a portion of semantic self-knowledge arises inductively from episodic self-knowledge (e.g., Kelley et al., 2002 ).

Recently some researchers have questioned the importance of memory’s role in creating a sense of identity. For example, at least when it comes to perceptions of others, people perceive a person’s identity to remain more intact after a neurodegenerative disease that affects their memory than one that affects their morality (Strohminger & Nichols, 2015 ).

Conscious and Nonconscious Self-Knowledge (Sometimes Confused With Explicit Versus Implicit)

Individuals may be conscious, or aware, of aspects of the self to varying degrees in different situations. Indeed sometimes it is adaptive to have self-awareness (Mandler, 1975 ) and other times it is not (Wegner, 2009 ). Nonconscious self-representations can influence behavior in that individuals may be unaware of the ways in which their self-representations affect their behavior (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995 ). Some researchers have even suggested that individuals can be unconscious of the contents of their self-representations (e.g., Devos & Banaji, 2003 ). It is important to remember that consciousness refers primarily to the level of awareness of a self-representation, rather than the automaticity of a given representation (i.e., whether the representation is retrieved in an unaware, unintentional, efficient, and uncontrolled manner) (Bargh, 1994 ).

A key ambiguity in recent work on implicit self-esteem is defining its criterial attributes. One view contends that the nonconscious and conscious self reflect fundamentally distinct knowledge systems that arise from different learning experiences and have independent effects on thought, emotion, and behavior (Epstein, 1994 ). Another perspective views the self as a singular construct that may nevertheless show diverging responses on direct and indirect measures of self due to factors such as the opportunity and motivation to control behavioral responses (Fazio & Twoles-Schwen, 1999 ). While indirect measures such as the Implicit Association Test do not require introspection and as a result may tap nonconscious representations, this is an assumption that should be supported with empirical evidence (Gawronski, Hofmann, & Wilbur, 2006 ).

Issues of direct and indirect measurement are a key consideration in research on the implicit and explicit self. Indirect measures of self allow researchers to infer an individual’s judgment about the self as a result of the speed or nature of their responses to stimuli that may be more or less self-related (De Houwer & Moors, 2010 ). Some researchers have argued that indirect measures of self-esteem are advantageous because they circumvent self-presentational issues (Farnham, Greenwald, & Banaji, 1999 ), but other researchers have questioned such claims (Gawronski, LeBel, & Peters, 2007 ) because self-presentational strivings can be automatized (Paulhus, 1993 ).

Recent findings have raised additional questions regarding the validity of some key assumptions regarding research inspired by interest in implicit self-esteem (for a more optimistic take on implicit self-esteem, see Dehart, Pelham, & Tennen, 2006 ). Although near-zero correlations between individuals’ scores on direct and indirect measures of self (e.g., Bosson, Swann, & Pennebaker, 2000 ) are often taken to mean that nonconscious and conscious self-representations are distinct, other factors, such as measurement error and lack of conceptual correspondence, can cause these low correlations (Gawronski et al., 2007 ). Some researchers have also taken evidence of negligible associations between measures of implicit self-esteem and theoretically related outcomes to mean that such measures may not measure self-esteem at all (Buhrmester, Blanton, & Swann, 2011 ). A prudent strategy is thus to consider that indirect measures reflect an activation of associations between the self and other stimuli in memory and that these associations do not require conscious validation of the association as accurate or inaccurate (Gawronski et al., 2007 ). Direct measures, on the other hand, do require validation processes (Strack & Deutsch, 2004 ; Swann, Hixon, Stein-Seroussi, & Gilbert, 1990 ).

Global and Specific Self-Knowledge

Self-views vary in scope (Hampson, John, & Goldberg, 1987 ). Global self-representations are generalized beliefs about the self (e.g., I am a worthwhile person) while specific self-representations pertain to a narrow domain (e.g., I am a nimble tennis player). Self-views can fall anywhere on a continuum between these two extremes. Generalized self-esteem may be thought of as a global self-representation at the top of a hierarchy with individual self-concepts nested underneath in specific domains such as academic, physical, and social (Marsh, 1986 ). Individual self-concepts, measured separately, combine statistically to form a superordinate global self-esteem factor (Marsh & Hattie, 1996 ). When trying to predict behavior it is important not to use a specific self-representation to predict a global behavior or a global self-representation to predict a specific behavior (e.g., Donnellan, Trzesniewski, Robins, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2005 ; Swann, Chang-Schneider, & McClarty, 2007 ; Trzesniewski et al., 2006 ).

Actual, Possible, Ideal, and Ought Selves

The self does not just include who a person is in the present but also includes past and future iterations of the self. In addition, people tend to hold “ought” or “ideal” beliefs about the self. The former includes one’s beliefs about who they should be according to their own and others’ standards while the latter includes beliefs about who they would like to be (Higgins, 1987 ). In a related vein, possible selves are the future-oriented positive or negative aspects of the self-concept, selves that one hopes to become or fears becoming (Markus & Nurius, 1986 ). Some research has even shown that distance between one’s feared self and actual self is a stronger predictor of life satisfaction than proximity between one’s ideal self and actual self (Ogilvie, 1987 ). Possible selves vary in how far in the future they are, how detailed they are, and how likely they are to become an actual self (Oyserman & James, 2008 ). Many researchers have studied the content of possible selves, which can be as idiosyncratic as a person’s imagination is. The method used to measure possible selves (close-ended versus open-ended questions) will affect which possible selves are revealed (Lee & Oyserman, 2009 ). The content of possible selves is also socially and contextually grounded. For example, as a person ages, career-focused possible selves become less important while health-related possible selves become increasingly important (Cross & Markus, 1991 ; Frazier, Hooker, Johnson, & Kaus, 2000 ).

Researchers have been interested in not just the content but the function of possible selves. Thinking about successful possible selves is mood enhancing (King, 2001 ) because it is a reminder that the current self can be improved. In addition, possible selves may play a role in self-regulation. By linking present and future selves, they may promote desired possible selves and avoid feared possible selves. Possible selves may be in competition with each other and with a person’s actual self. For example, someone may envision one possible self as an artist and another possible self as an airline pilot, and each of these possible selves might require the person to take different actions in the present moment. Goal striving requires employing limited resources and attention, so working toward one possible self may require shifting attention and resources away from another possible self (Fishbach, Dhar, & Zhang, 2006 ). Possible selves may have other implications as well. For example, Alesina and La Ferrara ( 2005 ) show how expected future income affects a person’s preferences for economic redistribution in the present.

Accuracy of Self-Knowledge and Feelings of Authenticity

Most individuals have had at least one encounter with an individual whose self-perception seemed at odds with “reality.” Perhaps it is a friend who believes himself to be a skilled singer but cannot understand why everyone within earshot grimaces when he starts singing. Or the boss who believes herself to be an inspiring leader but cannot motivate her workers. One potential explanation for inaccurate self-views is a disjunction between episodic and semantic memories; the image of grimacing listeners (episodic memory) may be quite independent of the conviction that one is a skilled singer (semantic memory). Of course, if self-knowledge is too disjunctive with reality it ceases to be adaptive; self-views must be moderately accurate to be useful in allowing people to predict and navigate their worlds. That said, some researchers have questioned the desirability of accurate self-views. For example, Taylor and Brown ( 1988 ) have argued that positive illusions about the self promote mental health. Similarly, Von Hippel and Trivers ( 2011 ) have argued that certain kinds of optimistic biases about the self are adaptive because they allow people to display more confidence than is warranted, consequently allowing them to reap the social rewards of that confidence.

Studying the accuracy of self-knowledge is challenging because objective criteria are often scarce. Put another way, there are only two vantage points from which to assess a person: self-perception and the other’s perception of the self. This is true even of supposedly “objective” measures of the self. An IQ test is still a measure of intelligence from the vantage point of the people who developed the test. Both vantage points can be subject to error. For example, self-perceptions may be biased to protect one’s self-image or due to self-comparison to an inappropriate referent. Others’ perceptions may be biased because of a lack of cross-situational information about the person in question or lack of insight into that person’s motives. Because of the advantages and disadvantages of each vantage point, self-reports may be better for assessing some traits (e.g., those low in observability, like neuroticism) while informant reports may be better for others (such as traits high in observability, like extraversion) (Vazire, 2010 ).

Furthermore, self-perceptions and others’ perceptions of the self may overlap to varying degrees. The “Johari window” provides a useful way of thinking about this (Luft & Ingham, 1955 ). The window’s first quadrant consists of things one knows about oneself that others also know about the self (arena). The second quadrant includes knowledge one has about the self that others do not have (façade). The third quadrant consists of knowledge one does not have about the self but others do have (blindspot). The fourth quadrant consists of information about the self that is not known to oneself or to others (unknown).

Which of these quadrants contains the “true self”? If I believe myself to be kind, but others do not, who is right? Which is a reflection of the “real me”? One set of attempts to answer this question has focused on perceptions of authenticity. The authentic self (Johnson & Boyd, 1995 ) is alternatively termed the “true self” (Newman, Bloom, & Knobe, 2014 ), “real self” (Rogers, 1961 ), “intrinsic self” (Schimel, Arndt, Pyszczynski, & Greenberg, 2001 ), “essential self” (Strohminger & Nichols, 2014 ), or “deep self” (Sripada, 2010 ). Recent research has addressed both what aspects of the self other people describe as belonging to a person’s true self and how individuals judge their own authenticity.

Though authenticity has long been the subject of philosophical thought, only recently have researchers begun addressing the topic empirically, and definitional ambiguities abound (Knoll, Meyer, Kroemer, & Schroeder-Abe, 2015 ). Some studies use unidimensional measures that equate authenticity to feeling close to one’s true self (e.g., Harter, Waters, & Whitesell, 1997 ). A more elaborate and philosophically grounded approach proposes four necessary factors for trait authenticity: awareness (the extent of one’s self-knowledge, motivation to expand it, and ability to trust in it), unbiased processing (the relative absence of interpretative distortions in processing self-relevant information), behavior (acting consistently with one’s needs, preferences, and values), and relational orientation (valuing and achieving openness in close relationships) (Kernis, 2003 ). Authenticity is related to feelings of self-alienation (Gino, Norton, & Ariely, 2010 ). Being authentic is also sometimes thought to be equivalent to low self-monitoring (Snyder & Gangestad, 1982 )— someone who does not alter his or her behavior to accommodate changing social situations (Grant, 2016 ). Authenticity and self-monitoring, however, are orthogonal constructs; being sensitive to environmental cues can be compatible with acting in line with one’s true self.

Although some have argued that the ability to behave in a way that contradicts one’s feelings and mental states is a developmental accomplishment (Harter, Marold, Whitesell, & Cobbs, 1996 ), feelings of authenticity have been associated with many positive outcomes such as positive self-esteem, positive affect, and well-being (Goldman & Kernis, 2002 ; Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis, & Joseph, 2008 ). One interesting line of research examines the interaction of authenticity, power, and well-being. Power can increase feelings of authenticity in social interactions (Kraus, Chen, & Keltner, 2011 ), and that increased authenticity in turn can result in higher well-being (Kifer, Heller, Peruvonic, & Galinsky, 2013 ). Another line of research examines the relationship between beliefs about authenticity (at least in the West) and morality. Gino, Kouchaki, and Galinsky ( 2015 ) suggest that dishonesty and inauthenticity share a similar source: dishonesty involves being untrue to others while inauthenticity involves being untrue to the self.

Metacognitive Aspects of Self

Valence and importance of self-views.

Self-knowledge may be positively or negatively valenced. Having more positive self-views and fewer negative ones are associated with having higher self-esteem (Brown, 1986 ). Both bottom-up and top-down theories have been used to explain this association. The bottom-up approach posits that the valence of specific self-knowledge drives the valence of one’s global self-views (e.g., Marsh, 1990 ). In this view, someone who has more positive self-views in specific domains (e.g., I am intelligent and attractive) should be more likely to develop high self-esteem overall (e.g., I am worthwhile). In contrast, the top-down perspective holds that the valence of global self-views drive the valence of specific self-views such that someone who thinks they are a worthwhile person is more likely to view him or herself as attractive and intelligent (e.g., Brown, Dutton, & Cook, 2001 ). The reasoning is grounded in the view that global self-esteem develops quite early in life and thus determines the later development of domain-specific self-views.

A domain-specific self-view can vary not only in its valence but also in its importance. Domain-specific self-views that one believes are important are more likely to affect global self-esteem than those self-views that one considers unimportant (Pelham, 1995 ; Pelham & Swann, 1989 ). As James wrote, “I, who for the time have staked my all on being a psychologist, am mortified if others know much more psychology than I. But I am contented to wallow in the grossest ignorance of Greek” ( 1890 / 1950 , p. 310). Of course not all self-views matter to the same extent for all people. A professor of Greek studies is likely to place a great deal of importance on his knowledge of Greek. Furthermore, changes to features that are perceived to be more causally central than others are believed to be more disruptive to identity (Chen, Urminsky, & Bartels, 2016 ). Individuals try to protect their important self-views by, for example, surrounding themselves with people and environments who confirm those important self-views (Chen, Chen, & Shaw, 2004 ; Swann & Pelham, 2002 ) or distancing themselves from close friends who outperform them in these areas (Tesser, 1988 ).

Certainty and Clarity of Self-Views

Individuals may feel more or less certain about some self-views as compared to others. And just as they are motivated to protect important self-views, people are also motivated to protect the self-views of which they are certain. People are more likely to seek (Pelham, 1991 ) and receive (Pelham & Swann, 1994 ) feedback consistent with self-views that are highly certain than those about which they feel less certain. They also actively resist challenges to highly certain self-views (Swann & Ely, 1984 ).

Another construct related to certainty is self-concept clarity. Not only are people with high self-concept clarity confident and certain of their self-views, they also are clear, internally consistent, and stable in their convictions about who they are (Campbell et al., 1996 ). The causes of low self-concept clarity have been theorized to be due to a discrepancy between one’s current self-views and the social feedback one has received in childhood (Streamer & Seery, 2015 ). Both high self-concept certainty and self-concept clarity are associated with higher self-esteem (Campbell, 1990 ).

Stability of Self-Views

The self is constantly accommodating, assimilating, and immunizing itself against new self-relevant information (Diehl et al., 2011 ). In the end, the self may remain stable (i.e., spatio-temporally continuous; Parfit, 1971 ) in at least two ways. First, the self may be stable in one’s absolute position on a scale. Second, there may be stability in one’s rank ordering within a group of related others (Hampson & Goldberg, 2006 ).

The question of the self’s stability can only be answered in the context of a specified time horizon. For example, like personality traits, self-views may not be particularly good predictors of behavior at a given time slice (perhaps an indication of the self’s instability) but are good predictors of behavior over the long term (Epstein, 1979 ). Similarly, more than others, some people experience frequent, transient changes in state self-esteem (Kernis, Cornell, Sun, Berry, & Harlow, 1993 ). Furthermore, there is a difference between how people perceive the stability of their self-views and the actual stability of their self-knowledge. Though previous research has explored the benefits of perceived self-esteem stability (e.g., Kernis, Paradise, Whitaker, Wheatman, & Goldman, 2000 ; Kernis, Grannemann, & Barclay, 1989 ), a recent program of research on fixed versus growth mindsets explores the benefits of the malleability of self-views in a variety of domains (Dweck, 1999 , 2006 ). For example, teaching adolescents to have a more malleable (i.e., incremental) theory of personality that “people change” led them to react less negatively to an immediate experience of social adversity, have lower overall stress and physical illness eight months later, and better academic performance over the school year (Yeager et al., 2014 ). Thus, believing that the self can be unstable can have positive effects in that one negative social interaction, or an instance of poor performance is not an indication that the self will always be that way, and this may, in turn, increase effort and persistence.

Organization of Self-Views

Though we have already touched on some aspects of the organization of self (e.g., specific self-views nested within global self-views), it is important to consider other aspects of organization including the fact that some self-views may be more assimilated within each other. Integration refers to the tendency to store both positive and negative self-views together, and is thought to promote resilience in the face of stress or adversity (Showers & Zeigler-Hill, 2007 ). Compartmentalization refers to the tendency to store positive and negative self-views separately. But both integration and compartmentalization can have positive and negative consequences and can interact with other metacognitive aspects of the self, like importance. For example, compartmentalization has been associated with higher self-esteem and less depression among people for whom positive components of the self are important (Showers, 1992 ). On the other hand, for those whose negative self-views are important, compartmentalization has been associated with lower self-esteem and higher depression.

Origins and Development of the Self

Developmental approaches.

Psychologists have long been interested in when and how infants develop a sense of self. One very basic question is whether selfhood in infancy is comparable to selfhood in adulthood. The answer depends on definitions of selfhood. For example, some researchers have measured and defined selfhood in infants as the ability to self-regulate and self-organize, which even animals can do. This definition bears little resemblance to selfhood in adulthood. Nativist and constructivist debates within developmental psychology (and language development in particular) that grapple with the problem of the origins of knowledge also have implications for understanding origins of the self. A nativist account (e.g., Chomsky, 1975 ) that considers the human mind to be innately constrained to formulate a very small set of representations would suggest that the mind is designed to develop a self. Information from the environment may form specific self-representations, but a nativist account would posit that the structure of the self is intrinsic. A constructivist account would reject the notion that there are not enough environmental stimuli to explain the development of a construct like the self unless one invokes a specific innate cognitive structure. Rather, constructivists might suggest that a child develops a theory of self in the same way scientific theories are developed (Gopnik, 2003 ).

Because infants and children cannot self-report their mental states as adults can, psychologists must use other methods to study the self in childhood. One method involves studying the development of children’s use of the personal pronouns “me,” “mine,” and “I” (Harter, 1983 ; Hobson, 1990 ). Another method that is used cross-culturally, mirror self-recognition (Lewis & Brooks-Gunn, 1979 ; Lewis & Ramsay, 2004 ), has been associated with brain maturation (Lewis, 2003 ) and myelination of the left temporal region (Carmody & Lewis, 2006 , 2010 ; Lewis & Carmody, 2008 ). Pretend play, which occurs between 15 and 24 months, is an indication that the self is developing because it requires the toddler’s ability to understand its own and others’ mental states (Lewis, 2011 ). The development of self-esteem has also historically been difficult to study due to a lack of self-esteem measures that can be used across the lifespan. Recently, psychologists have developed a lifespan self-esteem scale (Harris, Donnellan, & Trzesniewski, 2017 ) suitable for measuring global self-esteem from ages 5 to 93.

The development of theory of mind, the understanding that others have minds separate from one’s own, is also closely related to the development of the self. For example, people cannot make social comparisons until they have developed the required cognitive abilities, usually by middle childhood (Harter, 1999 ; Ruble, Boggiano, Feldman, & Loebl, 1980 ). Finally, developmental psychology is also useful in understanding the self beyond childhood and into adolescence and beyond. Adolescence is a time where goals of autonomy from parents and other adults become particularly salient (Bryan et al., 2016 ), adolescents experiment with different identities to see which fit best, and many long-term goals and personal aspirations are established (Crone & Dahl, 2012 ).

Biological Approaches

Biological approaches to understanding the origins of the self consider neurological, genetic, and hormonal underpinnings. These biological underpinnings are likely evolutionarily driven (Penke, Denissen, & Miller, 2007 ). Neuroscientists have debated the extent to which self-knowledge is “special,” or processed differently than other kinds of knowledge. What is clear is that no brain region by itself is responsible for our sense of self, but different aspects of the self-knowledge may be associated with different brain regions. Furthermore, the same region that is implicated in self-related processing can also be implicated in other types of processing (Ochsner et al., 2005 ; Saxe, Moran, Scholz, & Gabrieli, 2006 ). Specifically, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) have been associated with self-related processing (Northoff Heinzel, De Greck, Bermpohl, Dobrowolny, & Panksepp, 2006 ). But meta-analyses have found that the mPFC and PCC are recruited during the processing of both self-specific and familiar stimuli more generally (e.g., familiar others) (Qin & Northoff, 2011 ).

Twin studies of personality traits can shed light on the genetic bases of self. For example, genes account for about 40% to 60% of the population variance in self-reports of the Big Five personality factors (for a review, see Bouchard & Loehlin, 2001 ). Self-esteem levels also seem to be heritable, with 30–50% of population variance accounted for by genes (Kamakura, Ando, & Ono, 2007 ; Kendler, Gardner, & Prescott, 1998 ).

Finally, hormones are unlikely to be a cause of the self but may affect the expression of the self. For example, testosterone and cortisol levels interact with personality traits to predict different levels of aggression (Tackett et al., 2015 ). Differences in levels of and in utero exposure to certain hormones also affect gender identity (Berenbaum & Beltz, 2011 ; Reiner & Gearhart, 2004 ).

Intrapsychic Approaches

Internal processes, including self-perception and introspection, also influence the development of the self. One of the most obvious ways to develop knowledge about the self (especially when existing self-knowledge is weak) is to observe one’s own behavior across different situations and then make inferences about the aspects of the self that may have caused those behaviors (Bem, 1972 ). And just as judgments about others’ attributes are less certain when multiple possible causes exist for a given behavior, the same is true of one’s own behaviors and the amount of information they yield about the self (Kelley, 1971 ).

Conversely, introspection involves understanding the self from the inside outward rather than from the outside in. Though surprisingly little thought (only 8%) is expended on self-reflection (Csikszentmihalyi & Figurski, 1982 ), people buttress self-knowledge through introspection. For example, contemporary psychoanalysis can increase self-knowledge, even though an increase in self-knowledge on its own is unlikely to have therapeutic effects (Reppen, 2013 ). Writing is one form of introspection that does have psychological and physical therapeutic benefits (Pennebaker, 1997 ). Research shows that brief writing exercises can result in fewer physician visits (e.g., Francis & Pennebaker, 1992 ), and depressive episodes (Pennebaker, Kiecolt-Glaser, & Glaser, 1988 ), better immune function (e.g., Esterling, Kiecolt-Glaser, Bodnar, & Glaser, 1994 ), and higher grade point average (e.g., Cameron & Nicholls, 1998 ) and many other positive outcomes.

Experiencing the “subjective self” is yet another way that individuals gain self-knowledge. Unlike introspection, experiencing the subjective self involves outward engagement, a full engagement in the moment that draws attention away from the self (e.g., Csikszentmihalyi, 1990 ). Being attentive to one’s emotions and thoughts in the moment can reveal much about one’s preferences and values. Apparently, people rely more on their subjective experiences than on their overt behaviors when constructing self-knowledge (Andersen, 1984 ; Andersen & Ross, 1984 ).

Interpersonal Approaches

At the risk of stating the obvious, humans are social animals and thus the self is rarely cut off from others. In fact, many individuals would rather give themselves a mild electric shock than be alone with their thoughts (Wilson et al., 2014 ). The myth of finding oneself by eschewing society is dubious, and one of the most famous proponents of this tradition, transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau, actually regularly entertained visitors during his supposed seclusion at Walden (Schulz, 2015 ). As early as infancy, the reactions of others can lay the foundation for one’s self-views. Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969 ; Hazan & Shaver, 1994 ) holds that children’s earliest interactions with their caregivers lead them to formulate schemas about their lovability and worth. This occurs outside of the infant’s awareness, and the schemas are based on the consistency and responsiveness of the care they receive. Highly consistent responsiveness to the infant’s needs provide the basis for the infant to develop feelings of self-worth (i.e., high global self-esteem) later in life. Though the mechanisms by which this occur are still being investigated, it may be that self-schemas developed during infancy provide the lens through which people interpret others’ reactions to them (e.g., Hazan & Shaver, 1987 ). Note, however, that early attachment relationships are in no way deterministic: 30–45% of people change their attachment style (i.e., their pattern of relating to others) across time (e.g., Cozzarelli, Karafa, Collins, & Tagler, 2003 ).

Early attachment relationships provide a working model for how an individual expects to be treated, which is associated with perceptions of self-worth. But others’ appraisals of the self are also a more direct source of self-knowledge. An extremely influential line of thought from sociology, symbolic interactionism (Cooley, 1902 ; Mead, 1934 ), emphasized the component of the self that James referred to as the social self. He wrote, “a man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him and carry an image of him in their mind” ( 1890 / 1950 , p. 294). The symbolic interactionists proposed that people come to know themselves not through introspection but rather through others’ reactions and perceptions of them. This “looking glass self” sees itself as others do (Yeung & Martin, 2003 ). People’s inferences about how others view them become internalized and guide their behavior. Thus the self is created socially and is sustained cyclically.

Research shows, however, that reflected appraisals may not tell the whole story. While it is clear that people’s self-views correlate strongly with how they believe others see them, self-views are not necessarily perfectly correlated with how people actually view them (Shrauger & Schoeneman, 1979 ). Further, people’s self-views may inform how they believe others see them rather than the other way around (Kenny & DePaulo, 1993 ). Lastly, individuals are better at knowing how people see them in general rather than knowing how specific others view them (Kenny & Albright, 1987 ).

Though others’ perceptions of the self are not an individual’s only source of self-knowledge, they are an important source, and in more than one way. For example, others’ provide a reference point for “social comparison.” According to Festinger’s social comparison theory ( 1954 ), people compare their own traits, preferences, abilities, and emotions to those of similar others, making both upward and downward comparisons. These comparisons tend to happen spontaneously and effortlessly. The direction of the comparison influences how one views and feels about the self. For example, comparing the self to someone worse off boosts self-esteem (e.g., Helgeson & Mickelson, 1995 ; Marsh & Parker, 1984 ). In addition to increasing self-knowledge, social comparisons are also motivating. For instance, those undergoing difficult or painful life events can cope better when they make downward comparisons (Wood, Taylor, & Lichtman, 1985 ). When motivated to improve the self in a given domain, however, people may make upward comparisons to idealized others (Blanton, Buunk, Gibbons, & Kuyper, 1999 ). Sometimes individuals make comparisons to inappropriate others, but they have the ability (with mental effort) to undo the changes made to the self-concept as a result of this comparison (Gilbert, Giesler, & Morris, 1995 ).

Others can influence the self not only through interactions and comparisons but also when an individual becomes very close to a significant other. In this case, according to self-expansion theory (Aron & Aron, 1996 ), as intimacy increases, people experience cognitive overlap between the self and the significant other. People can acquire novel self-knowledge as they subsume attributes of the close other into the self.

Finally, the origins and development of the self are interpersonally influenced to the extent that our identities are dependent on the social roles we occupy (e.g., as mother, student, friend, professional, etc.). This will be covered in greater detail in the section on “The Social Self.” Here it is important simply to recognize that as the social roles of an individual inevitably change over time, so too does their identity.

Cultural Approaches

Markus and Kitayama’s seminal paper ( 1991 ) on differences in expression of the self in Eastern and Western cultures spawned an incredible amount of work investigating the importance of culture on self-construals. Building on the foundational work of Triandis ( 1989 ) and others, this work proposed that people in Western cultures see themselves as autonomous individuals who value independence and uniqueness more so than connectedness and harmony with others. In contrast to this individualism, people in the East were thought to be more collectivist, valuing interdependence and fitting in. However, the theoretical relationship between self-construals and the continuous individualism-collectivism variable have been treated in several different ways in the literature. Some have described individualism and collectivism as the origins of differences in self-construals (e.g., Gudykunst et al., 1996 ; Kim, Aune, Hunter, Kim, & Kim, 2001 ; Singelis & Brown, 1995 ). Others have considered self-construals as synonymous with individualism and collectivism (Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002 ; Taras et al., 2014 ) or have used individualism-collectivism at the individual level as an analog of the variable at the cultural level (Smith, 2011 ).

However, in contrast to perspectives that treat individualism and collectivism as a unidimensional variable (e.g., Singelis, 1994 ), individualism and collectivism have also been theorized to be multifaceted “cultural syndromes” that include normative beliefs, values, and practices, as well as self-construals (Brewer & Chen, 2007 ; Triandis, 1993 ). In this view, there are many ways of being independent or collectivistic depending on the domain of functioning under consideration. For example, a person may be independent or interdependent when defining the self, experiencing the self, making decisions, looking after the self, moving between contexts, communicating with others, or dealing with conflicting interests (Vignoles et al., 2016 ). These domains of functioning are orthogonal such that being interdependent in one domain does not require being interdependent in another. This multidimensional picture of individual differences in individualism and collectivism is actually more similar to Markus and Kitayama’s ( 1991 ) initial treatment aiming to emphasize cultural diversity and contradicts the prevalent unidimensional approach to cultural differences that followed.

Recent research has pointed out other shortcomings of this dichotomous approach. There is a great deal of heterogeneity among the world’s cultures, so simplifying all culture to “Eastern” and “Western” or collectivistic versus individualistic types may be invalid. Vignoles and colleagues’ ( 2016 ) study of 16 nations supports this. They found that neither a contrast between Western and non-Western, nor between individualistic and collectivistic cultures, sufficiently captured the complexity of cross-cultural differences in selfhood. They conclude that “it is not useful to characterize any culture as ‘independent’ or ‘interdependent’ in a general sense” and rather advocate for research that identifies what kinds of independence and interdependence may be present in different contexts ( 2016 , p. 991). In addition, there is a great deal of within culture heterogeneity in self-construals For example, even within an individualistic, Western culture like the United States, working-class people and ethnic minorities tend to be more interdependent (Markus, 2017 ), tempering the geographically based generalizations one might draw about self-construals.