Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 21 January 2021

The effects of tobacco control policies on global smoking prevalence

- Luisa S. Flor ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6888-512X 1 ,

- Marissa B. Reitsma 1 ,

- Vinay Gupta 1 ,

- Marie Ng ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8243-4096 2 &

- Emmanuela Gakidou ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8992-591X 1

Nature Medicine volume 27 , pages 239–243 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

35k Accesses

117 Citations

364 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Risk factors

Substantial global effort has been devoted to curtailing the tobacco epidemic over the past two decades, especially after the adoption of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control 1 by the World Health Organization in 2003. In 2015, in recognition of the burden resulting from tobacco use, strengthened tobacco control was included as a global development target in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development 2 . Here we show that comprehensive tobacco control policies—including smoking bans, health warnings, advertising bans and tobacco taxes—are effective in reducing smoking prevalence; amplified positive effects are seen when these policies are implemented simultaneously within a given country. We find that if all 155 countries included in our counterfactual analysis had adopted smoking bans, health warnings and advertising bans at the strictest level and raised cigarette prices to at least 7.73 international dollars in 2009, there would have been about 100 million fewer smokers in the world in 2017. These findings highlight the urgent need for countries to move toward an accelerated implementation of a set of strong tobacco control practices, thus curbing the burden of smoking-attributable diseases and deaths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reductions in smoking due to ratification of the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control in 171 countries

Accelerating tobacco control at the national level with the Smoke-free Generation movement in the Netherlands

A dynamic modelling analysis of the impact of tobacco control programs on population-level nicotine dependence

Decades after its ill effects on human health were first documented, tobacco smoking remains one of the major global drivers of premature death and disability. In 2017, smoking was responsible for 7.1 (95% uncertainty interval (UI), 6.8–7.4) million deaths worldwide and 7.3% (95% UI, 6.8%–7.8%) of total disability-adjusted life years 3 . In addition to the health impacts, economic harms resulting from lost productivity and increased healthcare expenditures are also well-documented negative effects of tobacco use 4 , 5 . These consequences highlight the importance of strengthening tobacco control, a critical and timely step as countries work toward the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals 2 .

In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) led the development of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the first global health treaty intended to bolster tobacco use curtailment efforts among signatory member states 1 . Later, in 2008, to assist the implementation of tobacco control policies by countries, the WHO introduced the MPOWER package, an acronym representing six evidence-based control measures (Table 1 ) (ref. 6 ). While accelerated adoption of some of these demand reduction policies was observed among FCTC parties in the past decade 7 , many challenges remain to further decrease population-level tobacco use. Given the differing stages of the tobacco epidemic and tobacco control across countries, consolidating the evidence base on the effectiveness of policies in reducing smoking is necessary as countries plan on how to do better. In this study, we evaluated the association between varying levels of tobacco control measures and age- and sex-specific smoking prevalence using data from 175 countries and highlighted missed opportunities to decrease smoking rates by predicting the global smoking prevalence under alternative unrealized policy scenarios.

Despite the enhanced global commitment to control tobacco use, the pace of progress in reducing smoking prevalence has been heterogeneous across geographies, development status, sex and age 8 ; in 2017, there were still 1.1 billion smokers across the 195 countries and territories assessed by the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study. Global smoking prevalence in 2017 among men and women aged 15 and older, 15–29 years, 30–49 years and 50 years and older are shown in Extended Data Figs. 1 , 2 , 3 and 4 , respectively. We found that, between 2009 and 2017, current smoking prevalence declined by 7.7% for men (36.3% (95% UI, 35.9–36.6%) to 33.5% (95% UI, 32.9–34.1%)) and by 15.2% for women globally (7.9% (95% UI, 7.8–8.1%) to 6.7% (95% UI, 6.5–6.9%)). The highest relative decreases were observed among men and women aged 15–29 years, at 10% and 20%, respectively. Conversely, prevalence decreased less intensively for those aged over 50, at 2% for men and 9.5% for women. While some countries have shown an important reduction in smoking prevalence between 2009 and 2017, such as Brazil, suggesting sustained progress in tobacco control, a handful of countries and territories have shown considerable increases in smoking rates among men (for example, Albania) and women (for example, Portugal) over this time period.

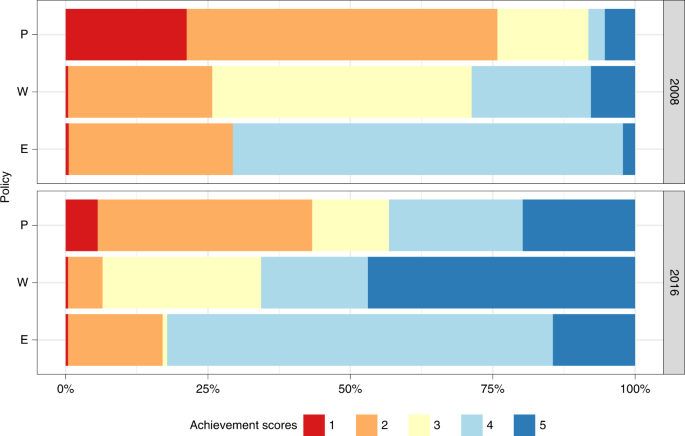

In an effort to counteract the harmful lifelong consequences of smoking, countries have, overall, implemented stronger demand reduction measures after the FCTC ratification. To assess national-level legislation quality, the WHO attributes a score to each of the MPOWER measures that ranges from 1 to 4 for the monitoring component (M) and 1–5 for the other components. A score of 1 represents no known data, while scores 2–5 characterize the overall strength of each measure, from the lowest level of achievement (weakest policy) to the highest level of achievement (strongest policy) 6 . Between 2008 and 2016, although very little progress was made in treatment provision (O) 7 , 9 , the share of the total population covered by best practice (score = 5) P, W and E measures increased (Fig. 1 ). Notably, however, a massive portion of the global population is still not covered by comprehensive laws. As an example, less than 15% of the global population is protected by strongly regulated tobacco advertising (E) and the number of people (2.1 billion) living in countries where none or very limited smoke-free policies (P) are in place (score = 2) is still nearly twice as high as the population (1.1 billion) living in locations with national bans on smoking in all public places (score = 5).

To assess national-level legislation quality, the WHO attributes a score to each MPOWER component that ranges from 1 to 5 for smoke-free (P), health warning (W) and advertising (E) policies. A score of 1 represents no known data or no recent data, while scores 2–5 characterize the overall strength of each policy, from 2 representing the lowest level of achievement (weakest policy), to 5 representing the highest level of achievement (strongest policy).

Source data

In terms of fiscal policies (R), the population-weighted average price, adjusted for inflation, of a pack of cigarettes across 175 countries with available data increased from I$3.10 (where I$ represents international dollars) in 2008 to I$5.38 in 2016. However, from an economic perspective, for prices to affect purchasing decisions, they need to be evaluated relative to income. The relative income price (RIP) of cigarettes is a measure of affordability that reflects, in this study, what proportion of the country-specific per capita gross domestic product (GDP) is needed to purchase half a pack of cigarettes a day for a year. Over time, cigarettes have become less affordable (RIP 2016 > RIP 2008) in about 75% of the analyzed countries, with relatively more affordable cigarettes concentrated across high-income countries.

Our adjusted analysis indicates that greater levels of achievement on key measures across the P, W and E policy categories and higher RIP values were significantly associated with reduced smoking prevalence from 2009 to 2017 (Table 2 ). Among men aged 15 and older, each 1-unit increment in achievement scores for smoking bans (P) was independently associated with a 1.1% (95% UI, −1.7 to −0.5, P < 0.0001) decrease in smoking prevalence. Similarly, an increase of 1 point in W and E scores was associated with a decrease in prevalence of 2.1% (95% UI, −2.7 to −1.6, P < 0.0001) and 1.9% (95% UI, −2.6 to −1.1, P < 0.0001), respectively. Furthermore, a 10 percentage point increase in RIP was associated with a 9% (95% UI, −12.6 to −5.0, P < 0.0001) decrease in overall smoking prevalence. Results were similar for men from other age ranges.

Among women, the magnitude of effect of different policy indicators varied across age groups. For those aged over 15, each 1-point increment in W and E scores was independently associated with an average reduction in prevalence of 3.6% (95% UI, −4.5 to −2.9, P < 0.0001) and 1.9% (95% UI, −2.9 to −1.8, P = 0.002), respectively, and these findings were similar across age groups. Smoking ban (P) scores were not associated with reduced prevalence among women aged 15–29 years or over 50 years. However, a 1-unit increase in P scores was associated with a 1.3% (95% UI, −2.3 to −0.2, P = 0.016) decline in prevalence among women aged 30–49 years. Lastly, while a 10 percentage point increase in RIP lowered women smoking prevalence by 6% overall (95% UI, −10.0 to −2.0, P = 0.014), this finding was not statistically significant when examining reductions in prevalence among those aged 50 and older (Table 2 ).

If tobacco control had remained at the level it was in 2008 for all 155 countries (with non-missing policy indicators for both 2008 and 2016; Methods ) included in the counterfactual analysis, we estimate that smoking prevalence would have been even higher than the observed 2017 rates, with 23 million more male smokers and 8 million more female smokers (age ≥ 15) worldwide (Table 3 ). Out of the counterfactual scenarios explored, the greatest progress in reducing smoking prevalence would have been observed if a combination of higher prices—resulting in reduced affordability levels—and strictest P, W and E laws had been implemented by all countries, leading to lower smoking rates among men and women from all age groups and approximately 100 million fewer smokers across all countries (Table 3 ). Under this policy scenario, the greatest relative decrease in prevalence would have been seen among those aged 15–29 for both sexes, resulting in 26.6 and 6.5 million fewer young male and female smokers worldwide in 2017, respectively.

Our findings reaffirm that a wide spectrum of tobacco demand reduction policies has been effective in reducing smoking prevalence globally; however, it also indicates that even though much progress has been achieved, there is considerable room for improvement and efforts need to be strengthened and accelerated to achieve additional gains in global health. A growing body of research points to the effectiveness of tobacco control measures 10 , 11 , 12 ; however, this study covers the largest number of countries and years so far and reveals that the observed impact has varied by type of control policy and across sexes and age groups. In high-income countries, stronger tobacco control efforts are also associated with higher cessation ratios (that is, the ratio of former smokers divided by the number of ever-smokers (current and former smokers)) and decreases in cigarette consumption 13 , 14 .

Specifically, our results suggest that men are, in general, more responsive to tobacco control interventions compared to women. Notably, with prevalence rates for women being considerably low in many locations, variations over time are more difficult to detect; thus, attributing causes to changes in outcome can be challenging. Yet, there is already evidence that certain elements of tobacco control policies that play a role in reducing overall smoking can have limited impact among girls and women, particularly those of low socioeconomic status 15 . Possible explanations include the different value judgments attached to smoking among women with respect to maintaining social relationships, improving body image and hastening weight control 16 .

Tax and price increases are recognized as the most impactful tobacco control policy among the suite of options under the MPOWER framework 10 , 14 , 17 , particularly among adolescents and young adults 18 . Previous work has also demonstrated that women are less sensitive than men to cigarette tax increases in the USA 19 . Irrespective of these demographic differences, effective tax policy is underutilized and only six countries—Argentina, Chile, Cuba, Egypt, Palau and San Marino—had adopted cigarette taxes that corresponded to the WHO-prescribed level of 70% of the price of a full pack by 2017 (ref. 20 ). Cigarettes also remain highly affordable in many countries, particularly among high-income nations, an indication that affordability-based prescriptions to countries, instead of isolated taxes and prices reforms, are possibly more useful as a tobacco control target. In addition, banning sales of single cigarettes, restricting legal cross-border shopping and fighting illicit trade are required so that countries can fully experience the positive effect of strengthened fiscal policies.

Smoke-free policies, which restrict the opportunities to smoke and decrease the social acceptability of smoking 17 , also affect population groups differently. In general, women are less likely to smoke in public places, whereas men might be more frequently influenced by smoking bans in bars, restaurants, clubs and workplaces across the globe due to higher workforce participation rates 16 . In addition to leading to reduced overall smoking rates, as indicated in this study, implementing complete smoking bans (that is, all public places completely smoke-free) at a faster pace can also play an important role in minimizing the burden of smoking-attributable diseases and deaths among nonsmokers. In 2017 alone, 2.18% (95% UI, 1.8–2.7%) of all deaths were attributable to secondhand smoke globally, with the majority of the burden concentrated among women and children 21 .

Warning individuals about the harms of tobacco use increases knowledge about the health risks of smoking and promotes changes in smoking-related behaviors, while full advertising and promotion bans—implemented by less than 20% of countries in 2017 (ref. 20 )—are associated with decreased tobacco consumption and smoking initiation rates, particularly among youth 17 , 22 , 23 . Large and rotating pictorial graphic warnings are the most effective in attracting smokers’ attention but are lacking in countries with high numbers of smokers, such as China and the USA 20 . Adding best practice health warnings to unbranded packages seems to be an effective way of informing about the negative effects of smoking while also eliminating the tobacco industry’s marketing efforts of using cigarette packages to make these products more appealing, especially for women and young people who are now the prime targets of tobacco companies 24 , 25 .

While it is clear that strong implementation and enforcement are crucial to accelerating progress in reducing smoking and its burden globally, our heterogeneous results by type of policy and demographics highlight the challenges of a one-size-fits-all approach in terms of tobacco control. The differences identified illustrate the need to consider the stages 26 of the smoking epidemics among men and women and the state of tobacco control in each country to identify the most pressing needs and evaluate the way ahead. Smoking patterns are also influenced by economic, cultural and political determinants; thus, future efforts in assessing the effectiveness of tobacco control policies under these different circumstances are of value. As tobacco control measures have been more widely implemented, tobacco industry forces have expanded and threaten to delay or reverse global progress 27 . Therefore, closing loopholes through accelerated universal adoption of the comprehensive set of interventions included in MPOWER, guaranteeing that no one is left unprotected, is an urgent requirement as efforts toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 are intensified.

This was an ecological time series analysis that aimed to estimate the effect of four key demand reduction measures on smoking rates across 175 countries. Country-year-specific achievement scores for P, W and E measures and an affordability metric measured by RIP—to capture the impact of fiscal policy (R)—were included as predictors in the model. Although the WHO also calls for monitoring (M) and tobacco cessation (O) interventions, these were not evaluated. Monitoring tobacco use is not considered a demand reduction measure, while very little progress has been made in treatment provision over the last decade 7 , 9 . Further information on research design is available in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Smoking outcome data

The dependent variable is represented by country-specific, age-standardized estimates of current tobacco smoking prevalence, defined as individuals who currently use any smoked tobacco product on a daily or occasional basis. Complete time series estimates of smoking prevalence from 2009 to 2017 for men and women aged 15–29, 30–49, 50 years and older and 15 years and older, were taken from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2017 study.

The GBD is a scientific effort to quantify the comparative magnitude of health loss due to diseases, injuries and risk factors by age, sex and geography for specific points in time. While full details on the estimation process for smoking prevalence have been published elsewhere, we briefly describe the main analytical steps in this article 3 . First, 2,870 nationally representative surveys meeting the inclusion criteria were systematically identified and extracted. Since case definitions vary between surveys, for example, some surveys only ask about daily smoking as opposed to current smoking that includes both daily and occasional smokers, the extracted data were adjusted to the reference case definition using a linear regression fit on surveys reporting multiple case definitions. Next, for surveys with only tabulated data available, nonstandard age groups and data reported as both sexes combined were split using observed age and sex patterns. These preprocessing steps ensured that all data used in the modeling were comparable. Finally, spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression, a three-step modeling process used extensively in the GBD to estimate risk factor exposure, was used to estimate a complete time series for every country, age and sex. In the first step, estimates of tobacco consumption from supply-side data are incorporated to guide general levels and trends in prevalence estimates. In the second step, patterns observed in locations, age groups and years with smoking prevalence data are synthesized to improve the first-step estimates. This step is particularly important for countries and time periods with limited or no available prevalence data. The third step incorporates and quantifies uncertainty from sampling error, non-sampling error and the preprocessing data adjustments. For this analysis, the final age-specific estimates were age-standardized using the standard population based on GBD population estimates. Age standardization, while less important for the narrower age groups, ensured that the estimated effects of policies were not due to differences in population structure, either within or between countries.

Using GBD-modeled data is a strength of the study since nearly 3,000 surveys inform estimates and countries are not required to have complete survey coverage between 2009 and 2017 to be included in the analysis. Yet, it is important to note that these estimates have limitations. For example, in countries where a prevalence survey was not conducted after the enactment of a policy, modeled estimates may not reflect changes in prevalence resulting from that policy. Nonetheless, the prevalence estimates from the GBD used in this study are similar to those presented in the latest WHO report 28 , indicating the validity and consistency of said estimates.

MPOWER data

Summary indicators of country-specific achievements for each MPOWER measure are released by the WHO every two years and date back to 2007. Data from different iterations of the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic (2008 6 , 2009 29 , 2011 30 , 2013 31 , 2015 32 and 2017 20 ) were downloaded from the WHO Tobacco Free Initiative website ( https://www.who.int/tobacco/about/en/ ). To assess the quality of national-level legislation, the WHO attributes a score to each MPOWER component that ranges from 1 to 4 for the monitoring (M) dimension and 1–5 for the other dimensions. A score of 1 represents no known data or no recent data, while scores 2–5 characterize the overall strength of each policy, from the lowest level of achievement (weakest policy) to the highest (strongest policy).

Specifically, smoke-free legislation (P) is assessed to determine whether smoke-free laws provide for a complete indoor smoke-free environment at all times in each of the respective places: healthcare facilities; educational facilities other than universities; universities; government facilities; indoor offices and workplaces not considered in any other category; restaurants or facilities that serve mostly food; cafes, pubs and bars or facilities that serve mostly beverages; and public transport. Achievement scores are then based on the number of places where indoor smoking is completely prohibited. Regarding health warning policies (W), the size of the warnings on both the front and back of the cigarette pack are averaged to calculate the percentage of the total pack surface area covered by the warning. This information is combined with seven best practice warning characteristics to construct policy scores for the W dimension. Finally, countries achievements in banning tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (E) are assessed based on whether bans cover the following types of direct and indirect advertising: (1) direct: national television and radio; local magazines and newspapers; billboards and outdoor advertising; and point of sale (indoors); (2) indirect: free distribution of tobacco products in the mail or through other means; promotional discounts; nontobacco products identified with tobacco brand names; brand names of nontobacco products used or tobacco products; appearance of tobacco brands or products in television and/or films; and sponsorship.

P, W and E achievement scores, ranging from 2 to 5, were included as predictors into the model. The goal was to not only capture the effect of adopting policies at its highest levels but also assess the reduction in prevalence that could be achieved if countries moved into the expected direction in terms of implementing stronger measures over time. Additionally, having P, W and E scores separately, and not combined into a composite score, enabled us to capture the independent effect of different types of policies.

Although compliance is a critical factor in understanding policy effectiveness, the achievement scores incorporated in our main analysis reflect the adoption of legislation rather than degree of enforcement, representing a limitation of these indicators.

Prices in I$ for a 20-cigarette pack of the most sold brand in each of the 175 countries were also sourced from the WHO Tobacco Free Initiative website for all available years (2008, 2010, 2012, 2014 and 2016). I$ standardize prices across countries and also adjust for inflation across time. This information was used to construct an affordability metric that captures the impact of cigarette prices on smoking prevalence, considering the income level of each country.

More specifically, the RIP, calculated as the percentage of per capita GDP required to purchase one half pack of cigarettes a day over the course of a year, was computed for each available country and year. Per capita GDP estimates were drawn from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; the estimation process is detailed elsewhere 33 .

Given that the price data used in the analysis refer to the most sold brand of cigarettes only, it does not reflect the full range of prices of different types of tobacco products available in each location. This might particularly affect our power in detecting a strong effect in countries where other forms of tobacco are more popular.

Statistical analysis

Sex- and age-specific logit-transformed prevalence estimates from 2009 to 2017 were matched to one-year lagged achievement scores and RIP values using country and year identifiers 34 . The final sample consisted of 175 countries and was constrained to locations and years with non-missing indicators. A multiple linear mixed effects model fitted by restricted maximum likelihood was used to assess the independent effect of P, W and E scores and RIP values on the rates of current smoking. Specifically, a country random intercept and a country random slope on RIP were included to account for geographical heterogeneity and within-country correlation. The regression model takes the following general form:

where y c,t is the prevalence of current smoking in each country ( c ) and year ( t ), β 0 is the intercept for the model and β p , β w , β e and β r are the fixed effects for each of the policy predictors. \(\mathrm{P}_{c,\,t - 1},\,\mathrm{W}_{c,\,t - 1},\,\mathrm{E}_{c,\,t - 1}\) are the P, W and E scores and R c , t −1 is the RIP value for country c in year t − 1. Finally, α c is the random intercept for country ( c ), while δ c represent the random slope for the country ( c ) to which the RIP value (R t − 1 ) belongs. Variance inflation factor values were calculated for all the predictor parameters to check for multicollinearity; the values found were low (<2) 35 . Bivariate models were also run and are shown in Extended Data Fig. 5 . The one-year lag introduced into the model may have led to an underestimation of effect sizes, particularly as many MPOWER policies require a greater period of time to be implemented effectively. However, due to the limited time range of our data (spanning eight years in total), introducing a longer lag period would have resulted in the loss of additional data points, thus further limiting our statistical power in detecting relevant associations between policies and smoking prevalence.

In addition to a joint model for smokers from both sexes, separate regressions were fitted for men and women and the four age groups (15–29, 30–49, ≥50 and ≥15 years old). To assess the validity of the mixed effects analyses, likelihood ratio tests comparing the models with random effects to the null models with only fixed effects were performed. Linear mixed models were fitted by maximum likelihood and t -tests used Satterthwaite approximations to degrees of freedom. P values were considered statistically significant if <0.05. All analyses were executed with RStudio v.1.1.383 using the lmer function in the R package lme4 v.1.1-21 (ref. 36 ).

A series of additional models to examine the impact of tobacco control policies were developed as part of this study. In each model, cigarette affordability (RIP) and a different set of policy metrics was used to capture the implementation, quality and compliance of tobacco control legislation. In models 1 and 2, we replaced the achievements scores by the proportion of P, W and E measures adopted by each country out of all possible measures reported by the WHO. In model 3, we used P and E (direct and indirect measures separately) compliance scores provided by the WHO to represent actual legislation implementation. Finally, an interaction term for compliance and achievement to capture the combined effect of legislation quality and performance was added to model 4. Results for men and women by age group for each of the additional models are presented in the Supplemental Information (Supplementary Tables 1–4 ).

The main model described in this study was chosen because it includes a larger number of country-year observations ( n = 823) when compared to models including compliance scores and because it is more directly interpretable.

Counterfactual analysis

To further explore and quantify the impact of tobacco control policies on current smoking prevalence, we simulated what smoking prevalence across all countries would have been achieved in 2017 under 4 alternative policy scenarios: (1) if achievement scores and RIP remained at the level they were at in 2008; (2) if all countries had implemented each of P, W and E component at the highest level (score = 5); (3) if the price of a cigarette pack was I$7.73 or higher, a price that represents the 90th percentile of observed prices across all countries and years; and (4) if countries had implemented the P, W and E components at the highest level and higher cigarette prices. To keep our results consistent across scenarios, we restricted our analysis to 155 countries with non-missing policy-related indicators for both 2008 and 2016.

Random effects were used in model fitting but not in this prediction. Simulated prevalence rates were calculated by multiplying the estimated marginal effect of each policy by the alternative values proposed in each of the counterfactual scenarios for each country-year. The global population-weighted average was computed for status quo and counterfactual scenarios using population data sourced from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Using the predicted prevalence rates and population data, the additional reduction in the number of current smokers in 2017 was also computed. Since models were ran using age-standardized prevalence, the number of smokers was proportionally redistributed across age groups using the sex-specific numbers from the age group 15 and older as an envelope.

The UIs for predicted estimates were based on a computation of the results of each of the 1,000 draws (unbiased random samples) taken from the uncertainty distribution of each of the estimated coefficients; the lower bound of the 95% UI for the final quantity of interest is the 2.5 percentile of the distribution and the upper bound is the 97.5 percentile of the distribution.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is publicly available at http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/global-tobacco-control-and-smoking-prevalence-scenarios-2017 ( https://doi.org/10.6069/QAZ7-6505 ). The dataset contains all data necessary to interpret, replicate and build on the methods or findings reported in the article. Tobacco control policy data that support the findings of this study are released every two years as part of the WHO’s Global Report on Tobacco Control; these data are also directly accessible at https://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/en/ . Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All code used for these analyses is available at http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/global-tobacco-control-and-smoking-prevalence-scenarios-2017 and https://github.com/ihmeuw/team/tree/effects_tobacco_policies .

World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control https://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/ (2003).

United Nations. Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication (2015).

Stanaway, J. D. et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392 , 1923–1994 (2018).

Article Google Scholar

Jha, P. & Peto, R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. N. Engl. J. Med. 370 , 60–68 (2014).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ekpu, V. U. & Brown, A. K. The economic impact of smoking and of reducing smoking prevalence: review of evidence. Tob. Use Insights 8 , 1–35 (2015).

World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER Package https://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2008/en/ (2008).

Chung-Hall, J., Craig, L., Gravely, S., Sansone, N. & Fong, G. T. Impact of the WHO FCTC over the first decade: a global evidence review prepared for the Impact Assessment Expert Group. Tob. Control 28 , s119–s128 (2019).

Reitsma, M. B. et al. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 389 , 1885–1906 (2017).

Nilan, K., Raw, M., McKeever, T. M., Murray, R. L. & McNeill, A. Progress in implementation of WHO FCTC Article 14 and its guidelines: a survey of tobacco dependence treatment provision in 142 countries. Addiction 112 , 2023–2031 (2017).

Dubray, J., Schwartz, R., Chaiton, M., O’Connor, S. & Cohen, J. E. The effect of MPOWER on smoking prevalence. Tob. Control 24 , 540–542 (2015).

Anderson, C. L., Becher, H. & Winkler, V. Tobacco control progress in low and middle income countries in comparison to high income countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13 , 1039 (2016).

Gravely, S. et al. Implementation of key demand-reduction measures of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and change in smoking prevalence in 126 countries: an association study. Lancet Public Health 2 , e166–e174 (2017).

Ngo, A., Cheng, K.-W., Chaloupka, F. J. & Shang, C. The effect of MPOWER scores on cigarette smoking prevalence and consumption. Prev. Med. 105S , S10–S14 (2017).

Feliu, A. et al. Impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and quit ratios in 27 European Union countries from 2006 to 2014. Tob. Control 28 , 101–109 (2019).

Google Scholar

Greaves, L. Gender, equity and tobacco control. Health Sociol. Rev. 16 , 115–129 (2007).

Amos, A., Greaves, L., Nichter, M. & Bloch, M. Women and tobacco: a call for including gender in tobacco control research, policy and practice. Tob. Control 21 , 236–243 (2012).

Hoffman, S. J. & Tan, C. Overview of systematic reviews on the health-related effects of government tobacco control policies. BMC Public Health 15 , 744 (2015).

Chaloupka, F. J., Straif, K. & Leon, M. E. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob. Control 20 , 235–238 (2011).

Rice, N., Godfrey, C., Slack, R., Sowden, A. & Worthy, G. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Price on the Smoking Behaviour of Young People (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2009); https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb/ShowRecord.asp?LinkFrom=OAI&ID=12013060057&LinkFrom=OAI&ID=12013060057

World Health Organizaion. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2017: Monitoring Tobacco Use and Prevention Policies https://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2017/en/ (2017).

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Compare https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ (2017).

Saffer, H. & Chaloupka, F. The effect of tobacco advertising bans on tobacco consumption. J. Health Econ. 19 , 1117–1137 (2000).

Noar, S. M. et al. The impact of strengthening cigarette pack warnings: systematic review of longitudinal observational studies. Soc. Sci. Med. 164 , 118–129 (2016).

Moodie, C., Brose, L. S., Lee, H. S., Power, E. & Bauld, L. How did smokers respond to standardised cigarette packaging with new, larger health warnings in the United Kingdom during the transition period? A cross-sectional online survey. Addict. Res. Theory 28 , 53–61 (2020).

Wakefield, M. et al. Australian adult smokers’ responses to plain packaging with larger graphic health warnings 1 year after implementation: results from a national cross-sectional tracking survey. Tob. Control 24 , ii17–ii25 (2015).

Thun, M., Peto, R., Boreham, J. & Lopez, A. D. Stages of the cigarette epidemic on entering its second century. Tob. Control 21 , 96–101 (2012).

Bialous, S. A. Impact of implementation of the WHO FCTC on the tobacco industry’s behaviour. Tob. Control 28 , s94–s96 (2019).

World Health Organization. Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Smoking 2000–2025 http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/surveillance/trends-tobacco-smoking-second-edition/en/ (2018).

World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2009: Implementing Smoke-Free Environments https://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2009/en/ (2009).

World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2011: Warning About the Dangers of Tobacco https://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/ (2011).

World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2013: Enforcing Bans on Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship https://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2013/en/ (2013).

World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2015: Raising Taxes on Tobacco https://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2015/en/ (2015).

James, S. L., Gubbins, P., Murray, C. J. & Gakidou, E. Developing a comprehensive time series of GDP per capita for 210 countries from 1950 to 2015. Popul. Health Metr. 10 , 12 (2012).

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Tobacco Control and Smoking Prevalence Scenarios 2017 (dataset) (Global Health Data Exchange, 2020).

Zuur, A. F., Ieno, E. N. & Elphick, C. S. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1 , 3–14 (2010).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01 (2015).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies (grant 47386, Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use). We thank the support of the Tobacco Metrics Team Advisory Group, which provided valuable comments and suggestions over several iterations of this manuscript. We also thank the Tobacco Free Initiative team at the WHO and the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids for making the tobacco control legislation data available and providing clarifications when necessary. We thank A. Tapp, E. Mullany and J. Whisnant for assisting in the management and execution of this study. We thank the team who worked in a previous iteration of this project, especially A. Reynolds, C. Margono, E. Dansereau, K. Bolt, M. Subart and X. Dai. Lastly, we thank all GBD 2017 Tobacco collaborators for their valuable work in providing feedback to our smoking prevalence estimates throughout the GBD 2017 cycle.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Department of Health Metrics Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Luisa S. Flor, Marissa B. Reitsma, Vinay Gupta & Emmanuela Gakidou

IBM Watson Health, San Jose, CA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

L.S.F., M.N. and E.G. conceptualized the study and designed the analytical framework. M.B.R. and V.G. provided input on data, results and interpretation. L.S.F. and E.G. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Emmanuela Gakidou .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Jennifer Sargent was the primary editor on this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended data fig. 1 prevalence of current smoking for men (a) and women (b) aged 15 years and older (age-standardized) in 2017..

Age-standardized smoking prevalence (%) estimates from the 2017 Global Burden of Disease Study for men (a) and women (b) aged 15 years and older for 195 countries. Smoking is defined as current use of any type of smoked tobacco product. Details on the estimation process can be found in the Methods section and elsewhere 3 .

Extended Data Fig. 2 Prevalence of current smoking for men (a) and women (b) aged 15 to 29 years old (age-standardized) in 2017.

Age-standardized smoking prevalence (%) estimates from the 2017 Global Burden of Disease Study for men (a) and women (b) aged 15–29 years old for 195 countries. Smoking is defined as current use of any type of smoked tobacco product. Details on the estimation process can be found in the Methods section and elsewhere 3 .

Extended Data Fig. 3 Prevalence of current smoking for men (a) and women (b) aged 30 to 49 years old (age-standardized) in 2017.

Age-standardized smoking prevalence (%) estimates from the 2017 Global Burden of Disease Study for men (a) and women (b) aged 30–49 years old for 195 countries. Smoking is defined as current use of any type of smoked tobacco product. Details on the estimation process can be found in the Methods section and elsewhere 3 .

Extended Data Fig. 4 Prevalence of current smoking for men (a) and women (b) aged 50 years and older (age-standardized) in 2017.

Age-standardized smoking prevalence (%) estimates from the 2017 Global Burden of Disease Study for men (a) and women (b) aged 50 years and older for 195 countries. Smoking is defined as current use of any type of smoked tobacco product. Details on the estimation process can be found in the Methods section and elsewhere 3 .

Extended Data Fig. 5 Percentage changes in current smoking prevalence based on fixed effect coefficients from bivariate mixed effect linear regression models, by policy component, sex and age group.

Bivariate models examined the unadjusted association between smoke-free (P), health warnings (W), and advertising (E) achievement scores, and cigarette’s affordability (RIP) and current smoking prevalence, from 2009 to 2017, across 175 countries (n = 823 country-years). Linear mixed models were fit by maximum likelihood and t-tests used Satterthwaite approximations to degrees of freedom. P values were considered statistically significant if lower than 0.05.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Tables 1–4: additional models results.

Source Data Fig. 1

Input data for Fig. 1 replication.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Input data for Extended Data 1 replication.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Input data for Extended Data 2 replication.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Input data for Extended Data 3 replication.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Input data for Extended Data 4 replication.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Flor, L.S., Reitsma, M.B., Gupta, V. et al. The effects of tobacco control policies on global smoking prevalence. Nat Med 27 , 239–243 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-01210-8

Download citation

Received : 28 May 2020

Accepted : 10 December 2020

Published : 21 January 2021

Issue Date : February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-01210-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Marketing claims, promotional strategies, and product information on malaysian e-cigarette retailer websites-a content analysis.

- Sameeha Misriya Shroff

- Chandrashekhar T Sreeramareddy

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy (2024)

Challenges in legitimizing further measures against smoking in jurisdictions with robust infrastructure for tobacco control: how far can the authorities allow themselves to go?

- Karl Erik Lund

- Gunnar Saebo

Harm Reduction Journal (2024)

Global smoking-related deaths averted due to MPOWER policies implemented at the highest level between 2007 and 2020

- Delia Hendrie

Globalization and Health (2024)

Health effects associated with exposure to secondhand smoke: a Burden of Proof study

- Luisa S. Flor

- Jason A. Anderson

- Emmanuela Gakidou

Nature Medicine (2024)

Single, Dual, and Poly Use of Tobacco Products, and Associated Factors Among Adults in 18 Global Adult Tobacco Survey Countries During 2015–2021

- Chandrashekhar T. Sreeramareddy

- Kiran Acharya

- N. RamakrishnaReddy

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Open access

- Published: 01 February 2017

College anti-smoking policies and student smoking behavior: a review of the literature

- Brooke L. Bennett 1 ,

- Melodi Deiner 1 &

- Pallav Pokhrel 1

Tobacco Induced Diseases volume 15 , Article number: 11 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

38 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Currently, most college campuses across the U.S. in some way address on-campus cigarette smoking, mainly through policies that restrict smoking on campus premises. However, it is not well understood whether college-level anti-smoking policies help reduce cigarette smoking among students. In addition, little is known about policies that may have an impact on student smoking behavior. This study attempted to address these issues through a literature review.

A systematic literature review was performed. To identify relevant studies, the following online databases were searched using specific keywords: Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Google Scholar. Studies that met the exclusion and inclusion criteria were selected for review. Studies were not excluded based on the type of anti-smoking policy studied.

Total 11 studies were included in the review. The majority of the studies (54.5%) were cross-sectional in design, 18% were longitudinal, and the rest involved counting cigarette butts or smokers. Most studies represented more women than men and more Whites than individuals of other ethnic/racial groups. The majority (54.5%) of the studies evaluated 100% smoke-free or tobacco-free campus policies. Other types of policies studied included the use of partial smoking restriction and integration of preventive education and/or smoking cessation programs into college-level policies. As far as the role of campus smoking policies on reducing student smoking behavior is concerned, the results of the cross-sectional studies were mixed. However, the results of the two longitudinal studies reviewed were promising in that policies were found to significantly reduce smoking behavior and pro-smoking attitudes over time.

More longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the role of college anti-smoking policies on student smoking behavior. Current data indicate that stricter, more comprehensive policies, and policies that incorporate prevention and cessation programming, produce better results in terms of reducing smoking behavior.

Tobacco use, especially cigarette smoking, continues to remain a leading preventable cause of mortality in the United States (U.S.). Across different age-groups, young adults (18–29 year olds) tend to show the highest prevalence of cigarette smoking [ 1 ]. For example, past-30-day prevalence of cigarette smoking among 18–24 year olds is 17%, whereas the prevalence is approximately 9% among high school students [ 2 ]. Although most smokers initiate cigarette smoking in adolescence, young adulthood is the period during which experimenters transition into regular use and develop nicotine dependence [ 1 ]. Young adulthood is also the period that facilitates continued intermittent or occasional smoking [ 3 ], neither of which is safe. In addition to the possibility that intermittent smokers may show escalation in nicotine dependence, intermittent smoking exposes individuals to carcinogens and induces adverse physiological consequences [ 4 ].

Research [ 5 ] shows that smokers who quit smoking before the age of 30 almost eliminate the risk of mortality due to smoking-induced causes. Thus smoking prevention and cessation efforts that target young adults are of importance. Traditionally, tobacco-related primary prevention efforts have mostly focused on adolescents [ 6 ] and have utilized mass media as well as school and community settings [ 7 , 8 ]. This is only natural given that most smoking initiation occurs in adolescence. However, primary and secondary prevention efforts focusing on young adults have been less common. This is particularly of concern because tobacco industry is known to market tobacco products strategically to promote tobacco use among young adults by integrating tobacco use into activities and places that are relevant to young adults [ 9 ].

As more and more young adults attend college [ 10 ], college campuses provide a great setting for primary and secondary smoking prevention as well as smoking cessation efforts targeting young adults. According to the American College Health Association [ 11 ], approximately 29% U.S. college students report lifetime cigarette smoking and 12% report past-30-day smoking. Currently, most college campuses across the U.S. in some way address on-campus cigarette smoking, mainly through policies that restrict smoking [ 12 , 13 ]. One of the main reasons why such policies are considered important is the concern about students’ exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke [ 14 ]. Therefore, at their most rudimentary forms, such policies tend to be extensions of local- or state-level policies restricting smoking in public places [ 15 ]. However, some colleges may take a more comprehensive approach, by integrating, for example, smoke-free policies with anti-smoking campaigns and college-sponsored cessation services [ 16 ]. Further, some colleges may implement plans to enhance enforcement of and compliance to the smoke-free policies [ 17 – 19 ].

At present, there are a number of questions related to college-level anti-smoking policies that need to be examined carefully in order to scientifically inform how colleges can be better utilized to promote smoking prevention and cessation among young adults. Besides the degree of variation in anti-smoking policies, there are questions about students’ compliance with such policies and whether such policies have influence on students’ attitudes and behavior related to cigarette smoking. Past reviews of the studies on the effects of tobacco control policies in general (e.g., not specific to college populations) [ 20 – 22 ] emphasize the need for a review such as the current study. Wilson et al. [ 20 ] found that interventions involving smoke-free public places, mostly restaurants/bars and workplaces, showed a moderate to low effect in terms of reducing smoking prevalence and promoting smoking cessation. The review included three longitudinal studies, none of which showed that the policies had an effect on smoking cessation. Fichtenberg & Glanz [ 21 ] focused on smoke-free workplaces and found that the effects of such policies seemed to depend on their strength. That is, 100% smoke-free policies were found to reduce cigarette consumption and smoking prevalence twice as much as partial smoke-free policies that allowed smoking in certain areas. In a recent exhaustive review, Frazer et al. [ 22 ] found that although national restrictions on smoking in public places may improve cardiovascular health outcomes and reduce smoking-related mortality, their effects on smoking behavior appear inconsistent. There are reasons why college anti-smoking policies may be more effective than policies focused on restaurant/bars or even workplaces. For example, students tend to spend the majority of their time on campus premises. In fact, in the case of 4-year colleges, a large number of students live on or around campus premises. Strong anti-smoking policies may deter students from smoking by making, for example, smoking very inconvenient. However, the current state of research on college anti-smoking policies and student smoking behavior is not well documented.

The purpose of the current study is to systematically review quantitative studies that have investigated the impact of college-level anti-smoking policies on students’ attitudes towards tobacco smoking and smoking behavior. In the process, we intend to highlight the types of research designs used across studies, the types of college and student participants represented across studies, and the studies’ major findings. A point to note is that this review’s focus is on anti-smoking policies and cigarette smoking. Although the review does assess tobacco-free policies in general, our assumption at the outset has been that most studies in the area have had a focus on smoke-free policies and smoking behavior because of the emphasis on secondhand smoke exposure. Smoke-free and tobacco-free policies are different in that smoke-free policies have traditionally targeted smoking only whereas tobacco-free policies that have targeted tobacco use of any kind, including smokeless tobacco [ 23 ]. Both types of policy could be easily extended to incorporate new tobacco products such as the electronic nicotine delivery devices, commonly known as e-cigarettes. Given that e-cigarettes are a relatively new phenomenon in the process of being regulated, we assumed that the studies eligible for the current review might not have addressed e-cigarette use, although if addressed by the studies reviewed, we were open to addressing e-cigarettes and e-cigarette use or vaping in the current review.

Study selection

We searched Ovid MEDLINE (1990 to June, 2016), PubMed (1990 to June, 2016), PsycINFO (1990 to 2013), and Google Scholar databases to identify U.S.-based peer-reviewed studies that examined the effects of college anti-smoking policies on young adults’ smoking behavior. Searches were conducted by crossing keywords “college” and “university” separately with “policy/policies” and “smoking”, “tobacco”, “school tobacco”, “smoke-free” “smoking ban,” and “tobacco free.” Article relevance was first determined by scanning the titles and abstracts of the articles generated from the initial search. Every quantitative study that dealt with college smoking policy was selected for the next round of appraisal, during which, the first and the last authors independently read the full texts of the articles to vet them for selection. Studies were selected for inclusion in the review if they met the following criteria: studies 1) were conducted in the U.S. college campuses, including 2- and 4-year colleges and universities; 2) were focused on young adults (18–25 year olds); 3) focused on implementation of college-level smoking policies; 4) were quantitative in methodology (e.g., case studies and studies based on focus groups and interviews were excluded); and 5) directly (e.g., self-report) or indirectly (e.g., counting cigarette butts on premises) assessed the cigarette smoking behavior. References and bibliographies of the articles that met the inclusion criteria were also carefully examined to locate additional, potentially eligible studies.

Selected studies were reviewed independently by the first and the last authors in terms of study objectives, study design (i.e., cross-sectional or longitudinal), data collection methods, participant characteristics, U.S. region where the study was conducted, college type (e.g., 2- year vs. 4-year), policies examined and the main study findings. The review results independently compiled by the two authors were compared and aggregated after differences were sorted out and a consensus was reached.

Study characteristics

Figure 1 depicts the path to the final set of articles selected for review. Initial searches across databases resulted in total 71 titles and abstracts related to college smoking policies. Of these, 49 were deemed ineligible at the first phase of evaluation. The remaining 22 articles were evaluated further, of which, 11 were excluded eventually. Two studies [ 24 , 25 ] were excluded because these studies did not assess students’ tobacco use behavior. One study [ 26 ] was excluded because it was not quantitative. Five studies [ 17 – 19 , 27 , 28 ] were excluded because the studies focused on compliance to existing smoking policies and did not assess the impact of policies on behavior. One study [ 15 ] was excluded because although it studied college students, the smoking policies examined were county-wide rather than college-level. Two studies [ 29 , 30 ] were excluded because their samples consisted of college personnel rather than students. Thus, a total of 11 studies were included in the current review.

Chart depicting selection of the final set of articles reviewed

Table 1 summarizes the selected studies in terms of research purpose, study design, subjects, type of college, region, policies and findings. The majority of the studies were conducted in the Midwestern ( n = 3; 27.3%) or Southeastern United States ( n = 3; 27.3%). Other regions represented across studies were Southern ( n = 2; 18.1%), Northwestern ( n = 2; 18.1%), and Western United States ( n = 1; 9.1%). Six studies (54.5%) included predominantly White participants (i.e., greater than 70%), and 2 studies (18%) included predominantly female participants. Nationally, women and Whites comprise 56% and 59% of the U.S. college student demographics, respectively [ 10 ]. Two studies (18.1%) assessed smoking behavior indirectly by counting cigarette butts on college premises, counting the number of individuals smoking cigarettes in campus smoking “hotspots,” or counting the number of smokers who utilized smoking cessation services. Across studies, the sample size ranged between N = 36 and N = 13,041. The mean and median sample sizes across studies were 3102 (SD = 4138) and 1309, respectively. Participants tended to range between 18 and 30 years in age. The majority of the studies ( n = 6; 54.4%) were cross-sectional in design. Only 2 (18%) of the studies were longitudinal. The majority of the studies were conducted at 4-year colleges ( n = 10; 90.9%). Only 1 study was conducted at a 2-year college ( n = 1; 9.1%).

Three studies (27%) focused on tobacco-free policies and 3 studies (27%) on smoke-free policies. Three studies ( n = 3; 27.3%) compared the associations of differing policies on smoking behavior. One study [ 31 ] examined the relative impacts of policies utilizing preventive education, smoking cessation programs, and designated smoking areas or partial smoking restriction. Another study [ 32 ] implemented an intervention to increase adherence to a partial smoking policy (i.e., smoking ban within 25 ft of buildings). The intervention involved increasing anti-tobacco signage, moving receptacles, marking the ground, and distributing reinforcements and reminder cards.

Anti-smoking policies and students’ smoking behavior

Table 1 lists the types of anti-smoking policies examined across studies and the corresponding findings. Major findings are as follows:

Partial smoking restriction

Borders et al. [ 31 ] compared colleges that utilized partial smoking restriction by providing “designated smoking areas” to curb smoking with college-level policies that incorporated preventive education and with those that provided smoking cessation courses only. Results indicated that the presence of preventive education was associated with lower odds of past-30-day smoking whereas the presence of designated smoking areas only or smoking cessation programs only was associated with higher odds of past-30-day smoking. Fallin et al. [ 16 ] found that college campuses with designated smoking areas tended to show higher prevalence of smoking, compared with campuses that enforced smoke-free and tobacco-free policies. Braverman et al.’s [ 33 ] findings indicate that enforcing smoke-free policies tends to reduce secondhand exposure close to college buildings but may increase smoking behavior on the campus periphery.

Smoke- and tobacco-free campuses

Fallin et al. [ 16 ] found that compared with policies that relied on partial smoking restriction, tobacco-free policies were associated with reduced self-reported exposure to secondhand smoke as well as students’ lower self-reported intentions to smoke cigarettes in the future. Studies [ 34 , 35 ] consistently observed fewer cigarette butts or smokers in campuses under smoke-free policies compared with campuses without smoke-free policies. Prevalence of cigarette butts was likely to be inversely related to policy strength [ 35 ]. A study that monitored smokers’ behavioral compliance to smoke-free policies [ 32 ] indicated that interventions to promote compliance, such as use of signage, are likely to be effective in improving compliance and reducing student smoking in areas were the policy is enforced.

Lechner et al. [ 36 ] conducted assessments at a single college campus before and after a tobacco-free policy went into implementation. The policy, which also involved making smoking cessation services available campus-wide, was found to reduce proportions of high- and low-frequency smokers, pro-smoking attitudes (i.e., weight loss expectancy), and exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke [ 36 ]. The study did not find an effect on smoking prevalence. Seo et al. [ 37 ] followed a similar design where a policy intervention was evaluated based on pretest and posttest surveys. However, this study [ 37 ] included a “control” campus where similar assessments as in the “treatment” campus were conducted but no intervention was implemented. The study found that compared with the control campus, the campus that implemented smoke-free policies showed an overall decrease in smoking prevalence.

Other policies

Borders et al. [ 31 ] did not find policies governing the sales and distribution of cigarettes on campus to be associated with smoking behavior. Hahn et al. [ 38 ] found that college smoking policies that integrate smoking cessation services may increase the use of such services as well as promote smoking cessation. This study kept track of students who utilized the smoking cessation service offered by a college after the policy offering such a service was enacted. Sixteen months after the policy was first implemented, smokers who utilized the service were surveyed. Based the results it was estimated that approximately 9% of them had quit smoking.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically review studies examining the effects of anti-smoking policies on smoking behaviors among U.S. college students. We found that such studies are severely limited. Only 11 studies met the inclusion criteria in the present review, although the review appeared to encompass all policies aimed at smoking behavior on college campuses. Thus, this review stresses the need for increased smoking policy and smoking behavior research on college campuses.

Rigorous evaluation of existing college anti-tobacco policies are needed to refine and improve the policies so that national-level efforts to reduce tobacco use among young adults are realized. Key initiatives at the national level have recognized the importance of mobilizing college campuses in the fight against tobacco use. For example, in September 2012 several national leaders involved in tobacco control efforts, in collaboration with the ACHA, came together to launch the Tobacco-Free College Campus Initiative (TFCCI) [ 39 ]. The TFCCI aims to promote and support the use of college-level anti-tobacco policies as a means to change pro-tobacco social norms on campuses, discourage tobacco use, protect non-smokers from second-hand exposure to tobacco smoke and promote smoking cessation. The ACHA’s position statement [ 11 ] regarding college tobacco control recommends a no tobacco use policy aimed towards achieving a 100% indoor and outdoor campus-wide tobacco-free environment.

We found that the majority of studies on smoking policies were cross-sectional in nature. Researchers relied upon students to report their smoking behavior or their observations of other students’ smoking behavior after a smoke-free or tobacco-free policy had been implemented. It is difficult to draw conclusions about an anti-smoking policy’s ability to change smoking behavior without knowing the smoking behavior prior to policy implementation. This domain of research would benefit from additional longitudinal studies. Ideally, research studies should collect data before the policy is implemented, immediately after, and at follow-up time points.

We found inconsistencies in the measurement of smoking behavior across studies. Two studies [ 34 , 35 ] counted cigarette butts, one study [ 38 ] counted people seeking tobacco dependence treatment, one study [ 32 ] counted smokers violating policy, and seven studies [ 16 , 31 , 36 , 37 , 40 , 41 ] relied upon self-report of smoking behavior. Another study [ 33 ] used survey methods to obtain participants’ response on other students’ smoking behavior. Counting cigarette butts has been validated as an effective measure of smoking behavior [ 19 ], especially when validating compliance to an anti-smoking policy, and self-report measures are commonly used in public health research [ 42 ]. Despite the validity and feasibility of these measures, the lack of a consistent measurement tool makes comparing effectiveness of anti-smoking policies on smoking behaviors across campuses difficult. Research in this domain would benefit from a consistently used measurement of smoking behaviors.

Although the reviewed studies represented diverse U.S. regions, the majority of the research was set in the Southeastern and Midwestern United States; Northeastern and Southwestern regions were not represented. Only one of the reviewed studies reported a sample that contained less than 50% White participants. Across studies, the minority group most represented was Asian American; but only one of the reviewed studies [ 16 ] included 20% or more Asian Americans. Relatively few studies included or reported Hispanic participants, although Hispanics are the largest minority group in the United States [ 43 ]. None of the reviewed studies included 20% or more Black participants. Only three studies [ 33 , 36 , 37 ] included American Indian/Alaska Natives and in only one of those studies [ 32 ] was the proportion greater than one percent. Only two studies [ 33 , 37 ] included Pacific Islanders, and in both the proportion was less than one percent. Clearly, more research is needed on minority populations, specifically Black, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native students and the subgroups commonly subsumed under these ethnic/racial categories. The U.S. college student demography is ethnically/racially diverse [ 10 ], comprising 59% Whites. The remaining 44% include various minority groups. Thus, for research on U.S. college students across the nation, studies with more ethnically/racially diverse student samples are needed.

The review findings were helpful in elucidating the types of tobacco policies being implemented on college campuses and their effects on the smoking behavior of U.S. college students. Mainly, three types of smoking policies were studied: smoke-free policies, tobacco-free policies and policies that enforced partial smoking restriction, including prohibition of smoking within 20–25 ft of all buildings and providing designated smoking areas. Indeed, campus-wide indoor and outdoor tobacco-free policy is considered a gold-standard for college campus tobacco control policy [ 11 ]. But only one study [ 16 ] compared tobacco-free and smoke-free policies. Other policies such as governing the sale and distribution of tobacco products, preventive education programs, and smoking cessations programs were also studied, but to a lesser extent. In general, interventions regarding the implementation of smoking policies on college campuses were difficult to find in the existing literature.

The combined results of the studies reviewed suggest that stricter smoking policies are more successful in reducing the smoking behavior of students. Tobacco-free and smoke-free policies were linked with reduced smoking frequency [ 16 , 36 , 37 ], reduced exposure to second-hand smoke [ 16 , 36 ], and a reduction in pro-smoking attitudes [ 36 ]. Implementation of a campus-wide tobacco-free or smoke-free policy combined with access to smoking cessation services was also associated with increased quit attempts [ 38 , 40 ] and treatment seeking behaviors [ 38 ]. It appears that 100% smoke-free policies are not only successful in reducing smoking rates, but also have strong support from students and staff members alike [ 33 ]. These results remained consistent when compared to less comprehensive tobacco control policies, which was evidenced by student report and the number of cigarette butts found on campus [ 34 , 35 ].

There was one important consistent exception to the general success of anti-smoking policies: designated smoking areas. All three studies which included designated smoking areas [ 16 , 31 , 41 ] found that designated smoking areas were associated with higher rates of smoking compared with smoke-free or tobacco-free policies. Designated smoking areas were also associated with the highest rates of recent smoking [ 16 ]. Lochbihler, Miller, and Etcheverry [ 41 ] proposed that students using the designated areas were more likely to experience positive effects of social interaction while smoking. They found that social interaction while smoking on campus significantly increased the perceived rewards associated with smoking and the frequency of visits to designated smoking areas [ 41 ].

None of the studies included in this review addressed new and emerging tobacco products such as e-cigarettes. This is understandable given that the surge in e-cigarette use is relatively new and in general there have only been a few studies examining the effects of anti-smoking policies on student smoking behavior, which has been the focus of this review. However, going forward, it will be crucial for studies to examine how campus policies are going to handle e-cigarette use, including the enforcement of on-campus anti-smoking policies given the new challenges posed by e-cigarette use [ 44 ]. For example, e-cigarette use is highly visible, the smell of the e-cigarette vapor does not linger in the air for long and e-cigarette consumption does not result in something similar to cigarette butts. These characteristics are likely to make the monitoring of policy compliance more difficult. Moreover, because of the general perception among e-cigarette users that e-cigarette use is safer than cigarette smoking, compared with cigarette smokers smoking cigarettes, e-cigarette users might be more likely to use e-cigarettes in public places. The fact that the TFCCI strongly recommends the inclusion of e-cigarettes in college tobacco-free policies [ 39 ] bodes well for the future of college health.

The current study has certain limitations. It is possible that this review might have missed a very small number of eligible studies. We believe that the literature searches we completed were thorough. However, new studies are regularly being published and the possibility that a new, eligible study may have been published after we completed our searches cannot be ignored. In addition, we may not have tapped eligible studies that were in press during our searches. If indeed a few eligible studies were not included in our review, the non-inclusion may have biased our results somewhat, although it is difficult for us to speculate the nature of such a bias. Hence, we recommend that similar studies need to be conducted in the future to periodically review the literature. Second, non-peer-reviewed articles or book chapters were excluded from this review. Despite the potential relevance of non-peer-reviewed materials, the choice was made to limit the inclusion in order to maintain scientific rigor of the review. However, it is possible that some data pertinent to the review might have been overlooked because of this, thus increasing the possibility of introducing a bias to the current findings. Third, this study focused on anti-smoking policies. Although we used “tobacco free” as search terms, “smoking” dominated our search strategies. Thus our results are more pertinent to cigarette smoking than other tobacco products and may not generalize to the latter. Lastly, in order to be as inclusive as possible, we reviewed three studies [ 32 , 35 , 38 ] that focused on more on compliance to anti-smoking policy than on the effect of policy on student smoking behavior. The findings of these studies may not be comprehensive in regard to student smoking behavior, even though they are indicative of the success of the policies under examination.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, this study is significant for increasing the understanding of smoking policies on U.S. college campuses and their effects on the smoking behavior of college students. We found that research on smoking policies on U.S. college campuses is very limited and is an area in need of additional research contribution. Within existing research, the majority used samples that were primarily White females. More diverse samples are needed. Future research should also report the full racial/ethnic characteristics of their samples in order to identify where representation may be lacking. Future research would benefit from longitudinal and interventional studies of the implementation of smoking policies. The majority of current research is cross-sectional, which does not provide the needed data in order to make causal statements about anti-smoking policies. Lastly, existing research was primarily conducted at 4-year colleges or universities. Future research would benefit from broadening the target campuses to include community colleges and trade schools. Community colleges provide a rich and unique opportunity to collect data on a population that is often older and more racial diverse than a typical 4-year college sample [ 45 ]. Also, there is at present a need to understand through research how evidence-based implementation and compliance strategies can be utilized to ensure policy success. A strong policy on paper does not often translate into a strong policy in action. Thus, comparing policies on the strength of written documents alone is not enough; policies need to be compared on the extent to which they are enforced as well as the impact they have on student behavior.

This review may be of particular interest to college or universities in the process of making their own anti-smoking policies. The combined results of the existing studies on the impact of anti-smoking policies on smoking behaviors among U.S. college students can help colleges and universities make informed decisions. The existing research suggests that stricter policies produce better results for smoking behavior reduction and with smoking continuing to remain a leading preventable cause of mortality in the U.S. across age-groups [ 1 ], college and university policy makers should take note. Young adults (18–25 year olds) show the highest prevalence of cigarette smoking [ 1 ], which places colleges and universities in the unique position to potentially intervene through restrictive anti-smoking policies on campus.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012.

Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Smoking and tobacco use. 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/ . Accessed 16 Aug 2016.

Pierce JP, White MM, Messer K. Changing age-specific patterns of cigarette consumption in the United States, 1992–2002: association with smoke-free homes and state-level tobacco control activity. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:171–7.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schane RE, Ling PM, Glanz SA. Health effects of light and intermittent smoking: a review. Circulation. 2010;121:1518–22.

Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the U.K. since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. BMJ. 2000;321:323–9.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bruvold WH. A meta-analysis of adolescent smoking prevention programs. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:872–80.