Essay on Inequality Between Rich And Poor

Students are often asked to write an essay on Inequality Between Rich And Poor in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Inequality Between Rich And Poor

What is inequality.

Inequality means not being equal, especially in status and chances to succeed. When talking about rich and poor people, it’s about the big gap between them. Rich people have more money, better houses, and can go to good schools. Poor people struggle for basic things like food and a place to live.

Why It Matters

This gap is important because it can make life unfair. If you’re born poor, it’s harder to get rich. This means not everyone gets the same start in life. Some have lots of help and chances, while others have very few.

What Causes Inequality?

Many things cause this gap. Rules that favor the rich, not enough good jobs, and poor access to education are some reasons. Sometimes, where you’re born or your family can decide if you’ll be rich or poor.

Effects on Society

A big gap between rich and poor can hurt everyone. It can lead to fewer people being happy and more crime. It can also make it hard for a country to grow strong because not all people can help build it.

What Can Be Done?

250 words essay on inequality between rich and poor.

Inequality is when people have different amounts of money, resources, or power. Some individuals have a lot, while others have very little. This difference is most clear when we look at rich and poor people.

Money Matters

Rich people can buy what they want, like good homes, education, and healthcare. Poor people often struggle to buy even basic things like food and a safe place to live. This difference means that rich and poor people live very different lives.

Education and Opportunities

Rich people can afford better schools, which often lead to better jobs and more money. Poor people might not go to school as much, which makes it hard for them to get good jobs. This makes it difficult for poor people to earn more money and improve their lives.

Health and Happiness

Rich people often have better health because they can pay for doctors and healthy food. Poor people may get sick more often because they can’t afford these things. Being sick can make it hard to work or go to school, which can keep people poor.

Why It’s a Problem

When rich and poor people live so differently, it’s not fair. Everyone should have a chance to live a good life. If only a few people have most of the money and power, it can make others feel left out or unhappy. It’s important to find ways to make things more equal so that everyone has the same chances in life.

500 Words Essay on Inequality Between Rich And Poor

Inequality between rich and poor is like a big gap or difference in what people have. Think of it as two groups of people: one group has a lot of money, nice houses, and can buy anything they want, while the other group has very little money, might not have a good place to live, and can’t always buy what they need.

Why Inequality Exists

Many reasons cause this gap. Sometimes, it’s because people are born into families with lots of money, so they start off with more than others. Other times, it’s because of the different chances people get, like better schools or jobs. Also, some places in the world have rules that make it easier for rich people to keep getting richer, while making it hard for poor people to get ahead.

The Effects of Inequality

Rich people, on the other hand, can do a lot more things. They can travel, eat healthy food, and go to the best schools. This can make them even richer as they grow up, because they have more opportunities.

There are ways to make this gap smaller. One way is to make sure everyone gets a good education, no matter how much money their family has. Another way is to have rules that help poor people get better jobs and pay them fair wages. Also, rich people can help by sharing some of their money with those who need it.

People Making a Difference

Inequality between rich and poor is a big issue that affects many people’s lives. It’s important to know about this gap so we can work together to make it smaller. By giving everyone the same chances to learn and work, and by helping each other, we can make the world a fairer place. Remember, even small actions can make a big difference in someone’s life.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Culture Online

Why do the rich keep getting richer and the poor keep getting poorer?

What compels people to think a certain type of way and understand things different to normal people? How does one break the cycle of poverty?

24 March 2021

That's a great question and something that many economists at UCL and elsewhere work on and also something that forms the central focus of the yearlong mandatory Economics module for UCL BSc Economics first-year students. Let me break down the question into two parts.

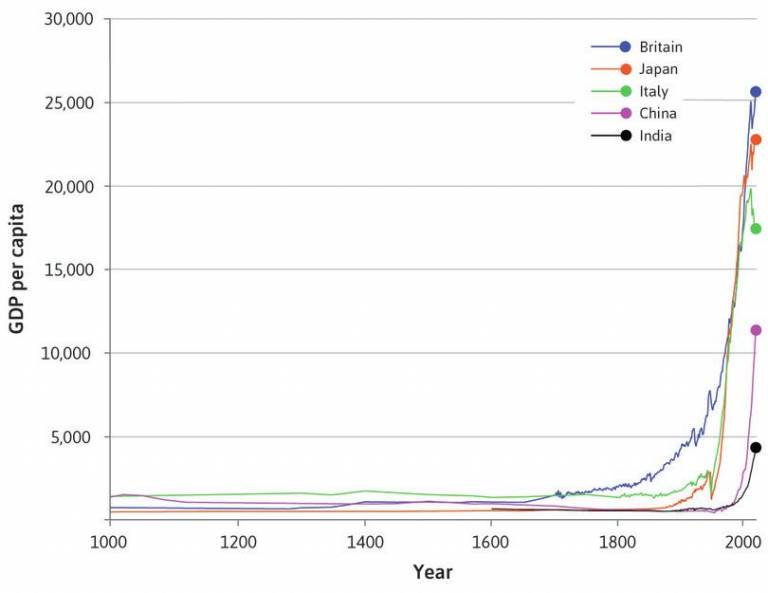

First, if you compare between different countries in the world, then you find that the gap between rich and poor countries has to a certain extent shrunk in recent times with the poorest countries in the world becoming quite a lot richer in the last 4 or 5 decades. This link from Our World in Data shows this (the graph is interactive, and there's lots more on this topic through the link).

For the second part, if you look at people within a country, particularly rich countries, you can see that inequality has indeed risen since about the late 1970s ( this link again from Our World in Data has more on it ). In the US in particular, this rise has to a certain degree been accompanied by the poor getting poorer over this period (not just the rich getting richer). There are several reasons for this development, including deindustrialisation, the ICT revolution favouring certain types of jobs, fall in unionisation, and globalisation.

Breaking out of the poverty trap is difficult of course, but one of the key factors that have been observed in both rich and poor countries, is investment in education and other human capital. Unfortunately in many of the countries that have seen the greatest rise in inequality in the last few decades, the government's spending on human capital (health, education, etc) has declined very often for ideological reasons. So there is a way to resolve this issue, but the political will is often missing.

Take a look at this free online book called 'The Economy' written by academics at UCL and other universities. The book is used by BSc Economics students in their first year of study.

Answered by:

Parama Chaudhury

View more questions

Meet our experts

Ask a question

If you'd like to provide feedback on the website itself, tell us what you think here .

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Richer and Poorer

For about a century, economic inequality has been measured on a scale, from zero to one, known as the Gini index and named after an Italian statistician, Corrado Gini, who devised it in 1912, when he was twenty-eight and the chair of statistics at the University of Cagliari. If all the income in the world were earned by one person and everyone else earned nothing, the world would have a Gini index of one. If everyone in the world earned exactly the same income, the world would have a Gini index of zero. The United States Census Bureau has been using Gini’s measurement to calculate income inequality in America since 1947. Between 1947 and 1968, the U.S. Gini index dropped to .386, the lowest ever recorded. Then it began to climb.

Income inequality is greater in the United States than in any other democracy in the developed world. Between 1975 and 1985, when the Gini index for U.S. households rose from .397 to .419, as calculated by the U.S. Census Bureau, the Gini indices of the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Sweden, and Finland ranged roughly between .200 and .300, according to national data analyzed by Andrea Brandolini and Timothy Smeeding. But historical cross-country comparisons are difficult to make; the data are patchy, and different countries measure differently. The Luxembourg Income Study, begun in 1983, harmonizes data collected from more than forty countries on six continents. According to the L.I.S.’s adjusted data, the United States has regularly had the highest Gini index of any affluent democracy. In 2013, the U.S. Census Bureau reported a Gini index of .476.

The evidence that income inequality in the United States has been growing for decades and is greater than in any other developed democracy is not much disputed. It is widely known and widely studied. Economic inequality has been an academic specialty at least since Gini first put chalk to chalkboard. In the nineteen-fifties, Simon Kuznets, who went on to win a Nobel Prize, used tax data to study the shares of income among groups, an approach that was further developed by the British economist Anthony Atkinson, beginning with his 1969 paper “On the Measurement of Inequality,” in the Journal of Economic Theory . Last year’s unexpected popular success of the English translation of Thomas Piketty’s “Capital in the Twenty-first Century” drew the public’s attention to measurements of inequality, but Piketty’s work had long since reached American social scientists, especially through a 2003 paper that he published with the Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez, in The Quarterly Journal of Economics . Believing that the Gini index underestimates inequality, Piketty and Saez favor Kuznets’s approach. (Atkinson, Piketty, Saez, and Facundo Alvaredo are also the creators of the World Top Incomes Database, which collects income-share data from more than twenty countries.) In “Income Inequality in the United States, 1913-1998,” Piketty and Saez used tax data to calculate what percentage of income goes to the top one per cent and to the top ten per cent. In 1928, the top one per cent earned twenty-four per cent of all income; in 1944, they earned eleven per cent, a rate that began to rise in the nineteen-eighties. By 2012, according to Saez’s updated data, the top one per cent were earning twenty-three per cent of the nation’s income, almost the same ratio as in 1928, although it has since dropped slightly.

Political scientists are nearly as likely to study economic inequality as economists are, though they’re less interested in how much inequality a market can bear than in how much a democracy can bear, and here the general thinking is that the United States is nearing its breaking point. In 2001, the American Political Science Association formed a Task Force on Inequality and American Democracy; a few years later, it concluded that growing economic inequality was threatening fundamental American political institutions. In 2009, Oxford University Press published both a seven-hundred-page “Handbook of Economic Inequality” and a collection of essays about the political consequences of economic inequality whose argument is its title: “The Unsustainable American State.” There’s a global version of this argument, too. “Inequality Matters,” a 2013 report by the United Nations, took the view—advanced by the economist Joseph Stiglitz in his book “The Price of Inequality”—that growing income inequality is responsible for all manner of political instability, as well as for the slowing of economic growth worldwide. Last year, when the Pew Research Center conducted a survey about which of five dangers people in forty-four countries consider to be the “greatest threat to the world,” many of the countries polled put religious and ethnic hatred at the top of their lists, but Americans and many Europeans chose inequality.

What’s new about the chasm between the rich and the poor in the United States, then, isn’t that it’s growing or that scholars are studying it or that people are worried about it. What’s new is that American politicians of all spots and stripes are talking about it, if feebly: inequality this, inequality that. In January, at a forum sponsored by Freedom Partners (a free-market advocacy group with ties to the Koch brothers), the G.O.P. Presidential swains Ted Cruz, Rand Paul, and Marco Rubio battled over which of them disliked inequality more, agreeing only that its existence wasn’t their fault. “The top one per cent earn a higher share of our income, nationally, than any year since 1928,” Cruz said, drawing on the work of Saez and Piketty. Cruz went on, “I chuckle every time I hear Barack Obama or Hillary Clinton talk about income inequality, because it’s increased dramatically under their policies.” No doubt there has been a lot of talk. “Let’s close the loopholes that lead to inequality by allowing the top one per cent to avoid paying taxes on their accumulated wealth,” Obama said during his State of the Union address. Speaker of the House John Boehner countered that “the President’s policies have made income inequality worse.”

The reason Democrats and Republicans are fighting over who’s to blame for growing economic inequality is that, aside from a certain amount of squabbling, it’s no longer possible to deny that it exists—a development that’s not to be sneezed at, given the state of the debate on climate change. That’s not to say the agreement runs deep; in fact, it couldn’t be shallower. The causes of income inequality are much disputed; so are its costs. And knowing the numbers doesn’t appear to be changing anyone’s mind about what, if anything, should be done about it.

Robert Putnam’s new book, “Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis” (Simon & Schuster), is an attempt to set the statistics aside and, instead, tell a story. “Our Kids” begins with the story of the town where Putnam grew up, Port Clinton, Ohio. Putnam is a political scientist, but his argument is historical—it’s about change over time—and fuelled, in part, by nostalgia. “My hometown was, in the 1950s, a passable embodiment of the American Dream,” he writes, “a place that offered decent opportunity for all the kids in town, whatever their background.” Sixty years later, Putnam says, Port Clinton “is a split-screen American nightmare, a community in which kids from the wrong side of the tracks that bisect the town can barely imagine the future that awaits the kids from the right side of the tracks.”

Inequality-wise, Port Clinton makes a reasonable Middletown. According to the American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, Port Clinton’s congressional district, Ohio’s ninth, has a Gini index of .467, which is somewhat lower than the A.C.S.’s estimate of the national average. But “Our Kids” isn’t a book about the Gini index. “Some of us learn from numbers, but more of us learn from stories,” according to an appendix that Putnam co-wrote with Jennifer M. Silva. Putnam, the author of “Bowling Alone,” is the director of the Saguaro Seminar for civic engagement at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government; Silva, a sociologist, has been a postdoctoral fellow there. In her 2013 book “Coming Up Short: Working-Class Adulthood in an Age of Uncertainty” (Oxford), Silva reported the results of interviews she conducted with a hundred working-class adults in Lowell, Massachusetts and Richmond, Virginia, described her account of the structural inequalities that shape their lives as “a story of institutions—not individuals or their families,” and argued that those inequalities are the consequence of the past half century’s “massive effort to roll back social protections from the market.” For “Our Kids,” Silva visited Robert Putnam’s home town and interviewed young people and their parents. Putnam graduated from Port Clinton High School in 1959. The surviving members of his class are now in their mid-seventies. Putnam and Silva sent them questionnaires; seventy-five people returned them. Silva also spent two years interviewing more than a hundred young adults in nine other cities and counties across the nation. As Putnam and Silva note, Silva conducted nearly all of the interviews Putnam uses in his book.

“Our Kids” is a heartfelt portrait of four generations: Putnam’s fellow 1959 graduates and their children, and the kids in Port Clinton and those nine other communities today and their parents. The book tells more or less the same story that the numbers tell; it’s just got people in it. Specifically, it’s got kids: the kids Putnam used to know, and, above all, the kids Silva interviewed. The book proceeds from the depressing assumption that presenting the harrowing lives of poor young people is the best way to get Americans to care about poverty.

Putnam has changed the names of all his subjects and removed certain identifying details. He writes about them as characters. First, there’s Don. He went to Port Clinton High School with Putnam. His father worked two jobs: an eight-hour shift at Port Clinton Manufacturing, followed by seven and a half hours at a local canning plant. A minister in town helped Don apply to university. “I didn’t know I was poor until I went to college,” Don says. He graduated from college, became a minister, and married a high-school teacher; they had one child, who became a high-school librarian. Libby, another member of Putnam’s graduating class, was the sixth of ten children. Like Don’s parents, neither of Libby’s parents finished high school. Her father worked at Standard Products, a factory on Maple Street that made many different things out of rubber, from weather stripping to tank treads. Libby won a scholarship to the University of Toledo, but dropped out to get married and have kids. Twenty years later, after a divorce, she got a job as a clerk in a lumberyard, worked her way up to becoming a writer for a local newspaper, and eventually ran for countywide office and won.

Link copied

All but two of the members of Putnam’s graduating class were white. Putnam’s wistfulness toward his childhood home town is at times painful to read. The whiteness of Port Clinton in the nineteen-fifties was not mere happenstance but the consequence of discriminatory housing and employment practices. I glanced through the records of the Ohio chapter of the N.A.A.C.P., which included a branch in Port Clinton. The Ohio chapter’s report for 1957 chronicles, among other things, its failed attempt to gain passage of statewide Fair Housing legislation; describes how “cross burnings occurred in many cities in Ohio”; recounts instances of police brutality, including in Columbus, where a patrolman beat a woman “with the butt of his pistol all over her face and body”; and states that in Toledo, Columbus, “and in a number of other communities, the Association intervened in situations where violence flared up or was threatened when Negro families moved into formerly ‘all-white neighborhoods.’ ” Thurgood Marshall, the director of the N.A.A.C.P.’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund, spoke in Ohio in 1958, after which a sympathetic Cleveland newspaper wrote that Marshall “will never be named to the Supreme Court.” In 1960, the Ohio N.A.A.C.P. launched a statewide voter-registration drive. One pamphlet asked, “Are you permitted to live wherever you please in any Ohio City?” Putnam acknowledges that there was a lot of racism in Port Clinton, but he suggests that, whatever hardships the two black kids in his class faced because they were black, the American dream was nevertheless theirs. This fails to convince. As one of those two kids, now grown, tells Putnam, “Your then was not my then, and your now isn’t even my now.”

In any case, the world changed, and Port Clinton changed with it. “Most of the downtown shops of my youth stand empty and derelict,” Putnam writes. In the late nineteen-sixties, the heyday of the Great Society, when income inequality in the United States was as low as it has ever been, the same was probably true of Port Clinton. But in the nineteen-seventies the town’s manufacturing base collapsed. Standard Products laid off more than half of its workers. In 1993, the plant closed. Since then, unemployment has continued to rise and wages to fall. Between 1999 and 2013, the percentage of children in Port Clinton living in poverty rose from ten to forty.

Silva found David hanging out in a park. His father, currently in prison, never had a steady job. David’s parents separated when he was a little boy. He bounced around, attending seven elementary schools. When he was thirteen, he was arrested for robbery. He graduated from high school only because he was given course credit for hours he’d worked at Big Boppers Diner (from which he was fired after graduation). In 2012, when David was eighteen, he got his girlfriend pregnant. “I’ll never get ahead,” he posted on his Facebook page last year, after his girlfriend left him. “I’m FUCKING DONE .”

Wealthy newcomers began arriving in the nineteen-nineties. On the shores of Lake Erie, just a few miles past Port Clinton’s trailer parks, they built mansions and golf courses and gated communities. “Chelsea and her family live in a large white home with a wide porch overlooking the lake,” Putnam writes, introducing another of his younger characters. Chelsea was the president of her high school’s student body and editor of the yearbook. Her mother, Wendy, works part time; her father, Dick, is a businessman. In the basement of their house, Wendy and Dick had a “1950s-style diner” built so that Chelsea and her brother would have a place to hang out with their friends. When Chelsea’s brother got a bad grade in school, Wendy went all the way to the school board to get it changed. Chelsea and her brother are now in college. Wendy does not appear to believe in welfare. “You have to work if you want to get rich,” she says. “If my kids are going to be successful, I don’t think they should have to pay other people who are sitting around doing nothing for their success.”

Aside from the anecdotes, the bulk of “Our Kids” is an omnibus of social-science scholarship. The book’s chief and authoritative contribution is its careful presentation for a popular audience of important work on the erosion, in the past half century, of so many forms of social, economic, and political support for families, schools, and communities—with consequences that amount to what Silva and others have called the “privatization of risk.” The social-science literature includes a complicated debate about the relationship between inequality of outcome (differences of income and of wealth) and inequality of opportunity (differences in education and employment). To most readers, these issues are more familiar as a political disagreement. In American politics, Democrats are more likely to talk about both kinds of inequality, while Republicans tend to confine their concern to inequality of opportunity. According to Putnam, “All sides in this debate agree on one thing, however: as income inequality expands, kids from more privileged backgrounds start and probably finish further and further ahead of their less privileged peers, even if the rate of socioeconomic mobility is unchanged.” He also takes the position, again relying on a considerable body of scholarship, that, “quite apart from the danger that the opportunity gap poses to American prosperity, it also undermines our democracy.” Chelsea is interested in politics. David has never voted.

The American dream is in crisis, Putnam argues, because Americans used to care about other people’s kids and now they only care about their own kids. But, he writes, “America’s poor kids do belong to us and we to them. They are our kids.” This is a lot like his argument in “Bowling Alone.” In high school in Port Clinton, Putnam was in a bowling league; he regards bowling leagues as a marker of community and civic engagement; bowling leagues are in decline; hence, Americans don’t take care of one another anymore. “Bowling Alone” and “Our Kids” also have the same homey just-folksiness. And they have the same shortcomings. If you don’t miss bowling leagues or all-white suburbs where women wear aprons—if Putnam’s then was not your then and his now isn’t your now—his well-intentioned “we” can be remarkably grating.

In story form, the argument of “Our Kids” is that while Wendy and Dick were building a fifties-style diner for their kids in the basement of their lakefront mansion, grade-grubbing with their son’s teachers, and glue-gunning the decorations for their daughter’s prom, every decent place to hang out in Port Clinton closed its doors, David was fired from his job at Big Boppers, and he got his girlfriend pregnant because, by the time David and Chelsea were born, in the nineteen-nineties, not only was Standard Products out of business but gone, too, was the sense of civic obligation and commonweal—everyone caring about everyone else’s kids—that had made it possible for Don and Libby to climb out of poverty in the nineteen-fifties and the nineteen-sixties. “Nobody gave a shit,” David says. And he’s not wrong.

“Our Kids” is a passionate, urgent book. It also has a sad helplessness. Putnam tells a story teeming with characters and full of misery but without a single villain. This is deliberate. “This is a book without upper-class villains,” he insists in the book’s final chapter. In January, Putnam tweeted, “My new book ‘Our Kids’ shows a growing gap between rich kids and poor kids. We’ll work with all sides on solutions.” It’s easier to work with all sides if no side is to blame. But Putnam’s eagerness to influence Congress has narrative consequences. If you’re going to tell a story about bad things happening to good people, you’ve got to offer an explanation, and, when you make your arguments through characters, your reader will expect that explanation in the form of characters. I feel bad for Chelsea. But I feel worse for David. Am I supposed to hate Wendy?

Some people make arguments by telling stories; other people make arguments by counting things. Charles Dickens was a story man. In “Hard Times” (1854), a novel written when statistics was on the rise, Dickens’s villain, Thomas Gradgrind, was a numbers man, “a man of facts and calculations,” who named one of his sons Adam Smith and another Malthus. “With a rule and a pair of scales, and the multiplication table always in his pocket, Sir, ready to weigh and measure any parcel of human nature, and tell you exactly what it comes to.”

Numbers men are remote and cold of heart, Dickens thought. But, of course, the appeal of numbers lies in their remoteness and coldness. Numbers depersonalize; that remains one of their chief claims to authority, and to a different explanatory force than can be found in, say, a poem. “Quantification is a technology of distance,” as the historian of science Theodore Porter has pointed out. “Reliance on numbers and quantitative manipulation minimizes the need for intimate knowledge and personal trust.” It’s difficult to understand something like income inequality across large populations and to communicate your understanding of it across vast distances without counting. But quantification’s lack of intimacy is also its weakness; it represents not only a gain but also a loss of knowledge.

Corrado Gini, he of the Gini index, was a numbers man, at a time when statistics had become a modern science. In 1925, four years after Gini wrote “Measurement of Inequality of Incomes,” he signed the “Manifesto of Fascist Intellectuals” (he was the only statistician to do so) and was soon running the Presidential Commission for the Study of Constitutional Reforms. As Jean-Guy Prévost reported in “A Total Science: Statistics in Liberal and Fascist Italy” (2009), Gini’s work was so closely tied to the Fascist state that, in 1944, after the regime fell, he was tried for being an apologist for Fascism. In the shadow of his trial, he joined the Movimento Unionista Italiano, a political party whose objective was to annex Italy to the United States. “This would solve all of Italy’s problems,” the movement’s founder, Santi Paladino, told a reporter for Time . (“Paladino has never visited the U.S., though his wife Francesca lived 24 years in The Bronx,” the magazine noted.) But, for Gini, the movement’s purpose was to provide him with some anti-Fascist credentials.

The story of Gini is a good illustration of the problem with stories, which is that they personalize (which is also their power). His support for Fascism doesn’t mean that the Gini index isn’t valuable. It is valuable. The life of Corrado Gini can’t be used to undermine all of statistical science. Still, if you wanted to write an indictment of statistics as an instrument of authoritarian states, and if you had a great deal of other evidence to support that indictment—including other stories and, ideally, numbers—why yes, Gini would be an excellent character to introduce in Chapter 1.

Because stories contain one kind of truth and numbers another, many writers mix and match, telling representative stories and backing them up with aggregate data. Putnam, though, doesn’t so much mix and match as split the difference. He tells stories about kids but presents data about the economy. That’s why “Our Kids” has heaps of victims but not a single villain. “We encounter Elijah in a dingy shopping mall on the north side of Atlanta, during his lunch break from a job packing groceries,” Putnam writes. “Elijah is thin and small in stature, perhaps five foot seven, and wears baggy clothes that bulk his frame: jeans belted low around his upper thighs, a pair of Jordans on his feet.” As for why Elijah is packing groceries, the book offers not characters—there are no interviews, for instance, with members of the Georgia legislature or the heads of national corporations whose businesses have left Atlanta—but numbers, citing statistics about the city (“Large swaths of southern and western Atlanta itself are over 95 percent black, with child poverty rates ranging from 50 percent to 80 percent”) and providing a series of charts reporting the results of studies about things like class differences in parenting styles and in the frequency of the family dinner.

In “The Age of Acquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth and Power” (Little, Brown), Steve Fraser fumes that what’s gone wrong with political discourse in America is that the left isn’t willing to blame anyone for anything anymore. There used to be battle cries. No more kings! Down with fat cats! Damn the moneycrats! Like Putnam’s argument, Fraser’s is both historical and nostalgic. Fraser longs for the passion and force with which Americans of earlier generations attacked aggregated power. Think of the way Frederick Douglass wrote about slavery, Ida B. Wells wrote about lynching, Ida Tarbell wrote about Standard Oil, Upton Sinclair wrote about the meatpacking industry, and Louis Brandeis wrote about the money trust. These people weren’t squeamish about villains.

To chronicle the rise of acquiescence, Fraser examines two differences between the long nineteenth century and today. “The first Gilded Age, despite its glaring inequities, was accompanied by a gradual rise in the standard of living; the second by a gradual erosion,” he writes. In the first Gilded Age, everyone from reporters to politicians apparently felt comfortable painting plutocrats as villains; in the second, this is, somehow, forbidden. “If the first Gilded Age was full of sound and fury,” he writes, “the second seemed to take place in a padded cell.” Fraser argues that while Progressive Era muckrakers ended the first Gilded Age by drawing on an age-old tradition of dissent to criticize prevailing economic, social, and political arrangements, today’s left doesn’t engage in dissent; it engages in consent, urging solutions that align with neoliberalism, technological determinism, and global capitalism: “Environmental despoiling arouses righteous eating; cultural decay inspires charter schools; rebellion against work becomes work as a form of rebellion; old-form anticlericalism morphs into the piety of the secular; the break with convention ends up as the politics of style; the cri de coeur against alienation surrenders to the triumph of the solitary; the marriage of political and cultural radicalism ends in divorce.” Why not blame the financial industry? Why not blame the Congress that deregulated it? Why not blame the system itself? Because, Fraser argues, the left has been cowed into silence on the main subject at hand: “What we could not do, what was not even speakable, was to tamper with the basic institutions of financial capitalism.”

Putnam closes “Our Kids” with a chapter called “What Is to Be Done?” Tampering with the basic institutions of financial capitalism is not on his to-do list. The chapter includes one table, one chart, many stories, and this statement: “The absence of personal villains in our stories does not mean that no one is at fault.” At fault are “social policies that reflect collective decisions,” and, “insofar as we have some responsibility for those collective decisions, we are implicated by our failure to address removable barriers to others’ success.” What can Putnam’s “we” do? He proposes changes in four realms: family structure, parenting, school, and community. His policy recommendations include expanding the earned-income tax credit and protecting existing anti-poverty programs; implementing more generous parental leaves, better child-care programs, and state-funded preschool; equalizing the funding of public schools, providing more community-based neighborhood schools, and increasing support for vocational high-school programs and for community colleges; ending pay-to-play extracurricular activities in public schools and developing mentorship programs that tie schools to communities and community organizations.

All of these ideas are admirable, many are excellent, none are new, and, at least at the federal level, few are achievable. The American political imagination has become as narrow as the gap between rich and poor is wide.

“Inequality: What Can Be Done?,” by Anthony Atkinson, will be published this spring (Harvard). Atkinson is a renowned expert on the measurement of economic inequality, but in “Inequality” he hides his math. “There are a number of graphs, and a small number of tables,” he writes, by way of apology, and he paraphrases Stephen Hawking: “Every equation halves the number of readers.”

Much of the book is a discussion of specific proposals. Atkinson believes that solutions like Putnam’s, which focus on inequality of opportunity, mainly through reforms having to do with public education, are inadequate. Atkinson thinks that the division between inequality of outcome and inequality of opportunity is largely false. He believes that tackling inequality of outcome is a very good way to tackle inequality of opportunity. (If you help a grownup get a job, her kids will have a better chance of climbing out of poverty, too.) Above all, he disagrees with the widespread assumption that technological progress and globalization are responsible for growing inequality. That assumption, he argues, is wrong and also dangerous, because it encourages the belief that growing inequality is inevitable.

Atkinson points out that neither globalization nor rapid technological advance is new and there are, therefore, lessons to be learned from history. Those lessons do not involve nostalgia. (Atkinson is actually an optimistic sort, and he spends time appreciating rising standards of living, worldwide.) One of those lessons is that globalizing economies aren’t like hurricanes or other acts of God or nature. Instead, they’re governed by laws regulating things like unions and trusts and banks and wages and taxes; laws are passed by legislators; in democracies, legislators are elected. So, too, new technologies don’t simply fall out of the sky, like meteors or little miracles. “The direction of technological change is the product of decisions by firms, researchers, and governments,” Atkinson writes. The iPhone exists, as Mariana Mazzucato demonstrated in her 2013 book “The Entrepreneurial State,” because various branches of the U.S. government provided research assistance that resulted in several key technological developments, including G.P.S., multi-touch screens, L.C.D. displays, lithium-ion batteries, and cellular networks.

Atkinson isn’t interested in stories the way Putnam is interested in stories. And he isn’t interested in villains the way Fraser is interested in villains. But he is interested in responsible parties, and in demanding government action. “It is not enough to say that rising inequality is due to technological forces outside our control,” Atkinson writes. “The government can influence the path taken.” In “Inequality: What Can Be Done?,” he offers fifteen proposals, from the familiar (unemployment programs, national savings bonds, and a more progressive tax structure) to the novel (a governmental role in the direction of technological development, a capital endowment or “minimum inheritance” paid to everyone on reaching adulthood), along with five “ideas to pursue,” which is where things get Piketty (a global tax on wealth, a minimum tax on corporations).

In Port Clinton, Ohio, a barbed-wire fence surrounds the abandoned Standard Products factory; the E.P.A. has posted signs warning that the site is hazardous. There’s no work there anymore, only poison. Robert Putnam finds that heartbreaking. Steve Fraser wishes people were angrier about it. Anthony Atkinson thinks something can be done. Atkinson’s specific policy recommendations are for the United Kingdom. In the United States, most of his proposals are nonstarters, no matter how many times you hear the word “inequality” on “Meet the Press” this year.

It might be that people have been studying inequality in all the wrong places. A few years ago, two scholars of comparative politics, Alfred Stepan, at Columbia, and the late Juan J. Linz—numbers men—tried to figure out why the United States has for so long had much greater income inequality than any other developed democracy. Because this disparity has been more or less constant, the question doesn’t lend itself very well to historical analysis. Nor is it easily subject to the distortions of nostalgia. But it does lend itself very well to comparative analysis.

Stepan and Linz identified twenty-three long-standing democracies with advanced economies. Then they counted the number of veto players in each of those twenty-three governments. (A veto player is a person or body that can block a policy decision. Stepan and Linz explain, “For example, in the United States, the Senate and the House of Representatives are veto players because without their consent, no bill can become a law.”) More than half of the twenty-three countries Stepan and Linz studied have only one veto player; most of these countries have unicameral parliaments. A few countries have two veto players; Switzerland and Australia have three. Only the United States has four. Then they made a chart, comparing Gini indices with veto-player numbers: the more veto players in a government, the greater the nation’s economic inequality. This is only a correlation, of course, and cross-country economic comparisons are fraught, but it’s interesting.

Then they observed something more. Their twenty-three democracies included eight federal governments with both upper and lower legislative bodies. Using the number of seats and the size of the population to calculate malapportionment, they assigned a “Gini Index of Inequality of Representation” to those eight upper houses, and found that the United States had the highest score: it has the most malapportioned and the least representative upper house. These scores, too, correlated with the countries’ Gini scores for income inequality: the less representative the upper body of a national legislature, the greater the gap between the rich and the poor.

The growth of inequality isn’t inevitable. But, insofar as Americans have been unable to adopt measures to reduce it, the numbers might seem to suggest that the problem doesn’t lie with how Americans treat one another’s kids, as lousy as that is. It lies with Congress. ♦

Money and Happiness in Poor and Wealthy Societies Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Positive correlation between happiness and money, insignificant correlation between happiness and money, works cited.

Many societies believe that money does not buy happiness. However, others affirm the contrary belief by saying that income levels affect people’s happiness. Before delving into the details of these perceptions, it is important to understand that happiness is an emotional or mental state where people experience more positive than negative feelings. These feelings outline how people interact with different stimuli, such as income, to influence their happiness.

People experience different emotional effects through such stimuli. The positive and negative effect refers to the effects that varying income levels have on people’s feelings and emotions. In detail, a positive effect refers to the extent that a person experiences positive moods (such as joy and interest), while negative affect refers to negative emotions (such as anxiety, sadness, and depression) that most people experience from varying income levels.

Using the above definitions, happiness, and emotional outcomes, Kesebir and Diener (117) say unsurprisingly different researchers have investigated the relationship between happiness and money. Indeed, many societies believe that life is not about (merely) living, but living a fulfilling and happy life (quality life). This realization has caused many philosophers to explore different ways of rising above the mere existence of life to a more fulfilling purpose of living.

Comprehending the motivations for pursuing money and happiness is the key to understanding this correlation. In this paper, I argue that wealthy and poor societies have different relationships between money and happiness. In detail, after exploring different types of correlation between the two variables, I explain that the relationship between both variables is strong in low-income societies, but it gradually weakens as income increases (especially in wealthy societies). Based on this understanding, money affects happiness to a limited extent. Indeed, beyond the satisfaction of basic human needs, other non-monetary factors, such as social relationships, have a more significant correlation with happiness than money does.

The positive correlation between money and happiness mainly exists in low-income societies. The utilitarian philosophies of the modern era affirm this relationship (Kesebir and Diener 117). However, their influences stem from common beliefs in the 19 th century (and beyond), which equaled happiness to utility (utility refers to the ability of material possessions to satisfy human needs and wants). Using the relationship between happiness and utility, many medieval societies believed the latter was equal to human pleasure (Kesebir and Diener 117). Jeremy Bentham and Aristotle (among other philosophers) supported this view by saying that most people should strive to experience more pleasure than pain (as a measure of their happiness) (Kesebir and Diener 117). They also argued that different societies should use this basis for understanding morality and legislation (Kesebir and Diener 117).

As many societies embraced this idea, the medieval conception of happiness, as a function of virtue and perfection, disappeared (Kesebir and Diener 117). People started to see material possessions as more important than gaining respect from society (by practicing good morals and virtues). Similarly, this ideological shift made it uncommon for many people to focus on issues of human well-being (human well-being closely associates with happiness because it refers to a state of health or prosperity) (Kesebir and Diener 117). Therefore, their focus shifted to material possessions as a measure of happiness.

In line with the above argument, Aristotle argued that wealth was an important requirement for happiness. Easterlin (3) shared the same view by explaining America’s perception of happiness. He said many US citizens perceived happiness through “material” lenses. The Easterlin (3) paradox summed this view by showing that income had a direct correlation with happiness. It based this argument on several cross-national studies, which showed that rich people were happier than poor people were. For example, in a 1970 American study, Easterlin (4) found out that less than one-quarter of low-income people believed they were “happy” people.

Comparatively, about double this number of respondents (in the high-income group) said they were happy. The same findings appeared in more than 30 similar researches conducted in other parts of the world. Although the same study established a correlation between happiness and education, health, and family relationships, income emerged as having the strongest and most consistent relationship with happiness (Easterlin 4).

Although Easterlin (3) used the above findings to support the correlation between income and happiness, he said increasing everybody’s income weakened the correlation between both variables. Therefore, income variations affected people’s perceptions of happiness (people always judge their happiness based on what their peers think of them). Lane (57) supported these views when he said that most people often adjusted to a new standard of measuring their happiness whenever they increased their income levels (the desire for money tapers off as income increases). Using this analogy, Easterlin (5) believed that wealthy nations were no happier than poor nations. Based on the same logic, he said that people’s subjective perceptions of happiness depended on their welfare perceptions (Easterlin 5).

Therefore, as opposed to perceiving their happiness through “material” lenses, they did so by understanding how it compared to their social norms. Consequently, people who are above the “norm” feel happier than those who are below it (how people perceive the social norm depends on the economic well-being of the society).

Although Easterlin (5) argued that happiness was subjective to the national income (as shown above), researchers who have conducted studies that are more recently told that the correlation between happiness and well-being was stronger than his paradox showed. Consequently, they revised this model by saying that increased national income affected the overall sense of individual well-being in a country. Unlike the data relied on Easterlin (4), researchers established the above fact, using findings that are more reliable. For example, Lane (56) quoted the findings of a 1976 transnational study, which showed that a nation’s poverty index affected the well-being of its citizens (such as people’s attitudes, feelings, and perceptions). These studies showed that personal satisfaction increased with increased levels of economic development (money “bought” happiness).

Money has an insignificant correlation with happiness in wealthy societies. This is an old view of this relationship because philosophers from ancient Greece started exploring this insignificant correlation in 370 BC (Kesebir and Diener 118). They said material wealth had an indirect correlation with happiness. Based on this understanding, they believed that a man’s mind defined his level of happiness. Similarly, they believed it was difficult for people to be happy if they lacked morals and virtues (money was not a priority). Democritus and Epicurus (two ancient Greek philosophers) mainly advanced this view (Kesebir and Diener 118).

Similarly, other ancient Greek philosophers, such as Socrates and his student, Plato, refuted the claim that happiness depended on the “enjoyment” of beautiful and good things. They believed that all people needed to show prudence and honor to be happy (Kesebir and Diener 118). Lane (56) has also reported the same findings after analyzing the relationship between money and happiness in a contextual approach. Like, Easterlin (3), he said in many developed countries, money did not increase happiness levels. Frank Andrews and Stephen Withey (cited in Lane 58) also supported these findings when they said that different socioeconomic groups showed small differences in people’s well-being. They also said that income levels had an insignificant impact on life as a whole.

The above findings show the different correlations between income and happiness. However, I believe this limited correlation mainly emerges in wealthy societies, as opposed to low-income societies. For example, non-monetary issues have a strong correlation with happiness in wealthy societies. Economists also affirm this fact through the Maslow hierarchy of needs because they say people crave for higher-level needs, such as love, social relationships, and recognition after they have met their primary needs such as food, shelter, sex, and clothing. Since many people in wealthy societies do not struggle to meet basic human needs, the insignificant correlation between happiness and money applies to this group of people.

Some philosophers maintain a “middle ground” by supporting the limited influence of money on happiness. Epicureans also supported this view because they said wealth was important to people’s happiness, to the extent that it gave people their basic needs, like shelter and clothing (Kesebir and Diener 118). However, beyond this threshold, it had an insignificant relationship with happiness. This analysis affirms the different correlations between happiness and income across poor and wealthy nations. Indeed, Kesebir and Diener 117) say there is a strong correlation between happiness and income in low-income countries, while wealthy economies experience an insignificant correlation between the two variables. A comparative study conducted in America revealed that the wealthiest Americans (profiled in Forbes) were only modestly happier than middle-income and low-income control groups that lived with them in the same location (Lane 58).

Based on the above analysis, income is not the only variable that affects happiness. Non-monetary issues affect happiness too. Lane (58) supports this argument by highlighting the need to distinguish individual pleasures from human well-being issues. Individual pleasures may depend on income, but people’s well-being is subjective. Therefore, besides income, other factors affect people’s happiness. To support this view, Lane (58) cited a 1982 study (conducted by Gallup), which asked Americans what made them happy (Lane 58). The respondents said family relationships made them happier than money did. Other things that made them happy included television, friends, reading books (and other pleasures) that most people from low-income families could afford (Lane 57).

Therefore, income does not solely define happiness. This analysis shows that although most people need to have adequate money to be happy, money, in isolation, is not sufficient to guarantee happiness, beyond providing basic needs. In the book, Happy People , Jonathan Freedman (cited in Lane 57) affirmed the above fact by saying that rich and poor people have different perceptions of the role of wealth in increasing people’s happiness levels. Overall, while many rich people understand that wealth does not automatically guarantee happiness, people from low-income societies believe it does. This was similarly true for their perceptions of well-being. Therefore, when a person is extremely poor, money looks like a “savior” of some sort, but as income increases, this idea disappears. This analogy has stronger merit than the general perception that money “buys” happiness. Indeed, not all happy people are rich. In this regard, many human societies have focused so much on material wealth that they have forgotten. It does not guarantee happiness.

After weighing the findings of this paper, easily, a person could affirm an indirect relationship between happiness and income. Some researchers say money has a direct relationship with happiness, while others do not affirm this relationship. This inconsistency stems from the contextual appeal of income and wealth to human societies. For example, income has a weak correlation with happiness in wealthy societies. However, this relationship is stronger in low-income societies. Evidence also shows that there was a weak correlation between income and happiness in medieval societies because many people believed adhering to human virtues made people happy (this was the medieval standard for happiness).

However, the modern era changed this perception and shifted the societal focus from virtues and morals to material wealth. Now, people attach more value to income and similar “material” factors. However, as changes to the Easterlin (3) paradox suggest, wealth increases happiness to a limited extent. Overall, this paper shows that income and happiness have a “contextual” relationship. For example, if there is a broad increase in income across a nation, this correlation weakens (the Easterlin (3) paradox mainly supports this view); however, as income levels decrease, the correlation strengthens. Consequently, there is a strong correlation between money and happiness in low-income societies. In wealthy societies, non-monetary factors like health and the quality of family relationships have a stronger impact on happiness than money does.

Easterlin, Richard. “Does Money Buy Happiness?” Public Interest 30.3 (1973): 3-10. Print.

Kesebir, Pelin and Ed Deiner. “In pursuit of happiness: Empirical Answers to Philosophical Questions.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 3.2 (2008): 117-123. Print.

Lane, Robert. “Does Money buy Happiness?” Public Interest 113.3 (1993): 56-65. Print.

- If “Love Is a Fallacy,” Are the “Loves” or Romantic Relationships Portrayed in the Story Logical or Illogical (Fallacious)?

- Happiness: Personal View and Suggestions

- Whether Housewives Happier than Full-time Working Mothers

- Money, Happiness and Relationship Between Them

- Money, Happiness and Satisfaction With Life

- Love Portrayal in Modern Day Film and Literature

- Love Concept: "Butterfly Lovers" and "Love Is a Fallacy"

- Analyzing Love and Love Addiction in Relationships

- The Nature of Humor: What Makes People Laugh

- Emotions and reasoning

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, May 26). Money and Happiness in Poor and Wealthy Societies. https://ivypanda.com/essays/money-and-happiness-in-poor-and-wealthy-societies/

"Money and Happiness in Poor and Wealthy Societies." IvyPanda , 26 May 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/money-and-happiness-in-poor-and-wealthy-societies/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Money and Happiness in Poor and Wealthy Societies'. 26 May.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Money and Happiness in Poor and Wealthy Societies." May 26, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/money-and-happiness-in-poor-and-wealthy-societies/.

1. IvyPanda . "Money and Happiness in Poor and Wealthy Societies." May 26, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/money-and-happiness-in-poor-and-wealthy-societies/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Money and Happiness in Poor and Wealthy Societies." May 26, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/money-and-happiness-in-poor-and-wealthy-societies/.

Download Your Free Book (pdf)

Modern Technology Is Increasing The Gap Between Rich and Poor - IELTS Essay

Get your personalised IELTS Essay Feedback from a former examiner

Download IELTS eBooks , get everything you need to achieve a high band score

Model Essay 1

The advent of modern technology has sparked a debate on its impact on socio-economic disparities, with opinions diverging on whether it widens or narrows the gap between the affluent and the underprivileged. This essay contends that while technology can indeed exacerbate inequality, its potential to democratize access to information and opportunities predominantly serves to bridge the socio-economic divide.

Proponents of the view that technology aggravates inequality argue that the high cost of cutting-edge technologies and the skills required to harness them create significant barriers for the less affluent. This phenomenon, known as the "digital divide," implies that wealthier individuals and nations can leverage technology to gain even more wealth, thus exacerbating the socio-economic disparities. For instance, access to high-speed internet, indispensable for many modern professions, remains a luxury in numerous parts of the world. This disparity is further highlighted by the digital literacy gap, which prevents the underprivileged from fully participating in the digital economy, underscoring the widening gap.

Conversely, the argument that technology acts as a great equalizer is both compelling and supported by numerous global success stories. Online education platforms, for example, offer free or low-cost courses to millions, providing a vital ladder for socio-economic mobility and bridging the knowledge divide. Furthermore, mobile banking and fintech innovations have revolutionized financial inclusion in regions previously underserved by traditional banking systems, enabling small entrepreneurs in remote areas to access credit, manage finances, and grow their businesses efficiently. These advancements not only underscore technology's potential to level the playing field but also illustrate its role in fostering entrepreneurial spirit and innovation among the economically disadvantaged.

In conclusion, while it is undeniable that technological advancements can initially deepen socio-economic rifts due to unequal access and capability gaps, the broader perspective reveals a trend towards inclusivity and empowerment. As we harness technology responsibly and inclusively, its capacity to dismantle barriers and foster equality becomes increasingly apparent, making it a pivotal tool in the quest to narrow the gap between rich and poor.

Model Essay 2

In the contemporary era, the role of modern technology in shaping socio-economic disparities has sparked a polarizing debate. Some argue it exacerbates the divide between the affluent and the destitute, while others believe it bridges this gap. This essay contends that technology serves both to widen and narrow these disparities, depending on its accessibility and application.

On one hand, technology's proponents highlight its democratizing potential. The advent of online education platforms, for instance, has rendered knowledge more accessible, enabling individuals from underprivileged backgrounds to acquire skills and education that were previously beyond their reach. Such platforms have not only democratized education but have also empowered individuals with the tools necessary for socio-economic advancement, thus potentially leveling the playing field. Moreover, digital financial services have facilitated greater financial inclusion, allowing people in remote areas to access banking services, thereby fostering economic empowerment and reducing geographical barriers to financial services.

Conversely, the critics of technological advancement point to the digital divide as a significant factor that exacerbates inequality. Access to cutting-edge technology often requires substantial financial resources, making it a privilege of the wealthy. Consequently, while the affluent have the luxury of leveraging technology to amplify their wealth, the poor are left further behind due to lack of access. This disparity is evident in the job market, where high-paying roles increasingly demand advanced technological skills, thus marginalizing those without the means to acquire such education. Moreover, this gap widens as technology evolves, requiring constant upskilling that disproportionately favors the economically advantaged.

In conclusion, while technology has the potential to bridge the gap between the rich and poor by democratizing access to education and financial services, the prevailing digital divide underscores its role in widening socio-economic disparities. Ultimately, the impact of technology on socio-economic inequality is contingent upon efforts to ensure equitable access.

- Task 2 Essays

Recent Posts

It Is Better for Children to Have Many Short Holidays during the Academic Year - IELTS Task 2 Band 9 Essays

In Some Educational Systems, Children Are Required to Study One or More Foreign Languages - Task 2 Band 9 Sample Essays

Doctors Should Be Responsible for Educating Their Patients about How to Improve Their Health - IELTS Task 2 Band 9 Sample Essays

Advertisement

Supported by

Study Shows Income Gap Between Rich and Poor Keeps Growing, With Deadly Effects

- Share full article

By Lola Fadulu

- Published Sept. 10, 2019 Updated June 11, 2020

WASHINGTON — The expanding gap between rich and poor is not only widening the gulf in incomes and wealth in America. It is helping the rich lead longer lives, while cutting short the lives of those who are struggling, according to a study released this week by the Government Accountability Office.

Almost three-quarters of rich Americans who were in their 50s and 60s in 1992 were still alive in 2014. Just over half of poor Americans in their 50s and 60s in 1992 made it to 2014.

“It’s not only that rich people are living longer but some people’s life expectancy is actually shrinking compared to their parents, for some groups of people,” said Kathleen Romig, a senior policy analyst at the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Income inequality has roiled American society and politics for years, animating the rise of Barack Obama out of the collapse of the financial system in 2008, energizing right-wing populism and the emergence of nationalist leaders like Donald J. Trump, and pushing the Democratic Party leftward. Senator Bernie Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist who is seeking the Democratic presidential nomination, commissioned the report from the Government Accountability Office, Congress’s independent watchdog, and seized on its findings.

“Poverty is a life-threatening issue for millions of people in this country, and this report confirms it,” Mr. Sanders said in a statement .

The Census Bureau reported on Tuesday that the poverty rate declined last year to 11.8 percent, the lowest level since 2001. But median household income was $63,200 in 2018, essentially unchanged from a year earlier, and income gains slowed last year from the increases posted in 2015 and 2016.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

IELTS Mentor "IELTS Preparation & Sample Answer"

- Skip to content

- Jump to main navigation and login

Nav view search

- IELTS Sample

IELTS Writing Task 2/ Essay Topics with sample answer.

Ielts writing task 2 sample 400 - the gap between rich and poor is becoming wider, ielts writing task 2/ ielts essay:, the gap between the rich and the poor is becoming wider; the rich are becoming richer, and the poor are getting even poorer. what problems can the situation cause what can be done to reduce this gap.

- IELTS Essay

- Writing Task 2

IELTS Materials

- IELTS Bar Graph

- IELTS Line Graph

- IELTS Table Chart

- IELTS Flow Chart

- IELTS Pie Chart

- IELTS Letter Writing

- Academic Reading

Useful Links

- IELTS Secrets

- Band Score Calculator

- Exam Specific Tips

- Useful Websites

- IELTS Preparation Tips

- Academic Reading Tips

- Academic Writing Tips

- GT Writing Tips

- Listening Tips

- Speaking Tips

- IELTS Grammar Review

- IELTS Vocabulary

- IELTS Cue Cards

- IELTS Life Skills

- Letter Types

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Copyright Notice

- HTML Sitemap

The ‘Rich’ and ‘Poor’: The Widening Income and Development Gap Between Rich and Poor Nations Worldwide

- First Online: 25 June 2019

Cite this chapter

- Richard J. Estes 10

Part of the book series: Social Indicators Research Series ((SINS,volume 76))

1032 Accesses

1 Citations

Wealth inequalities both within and between nations has reached an extreme point and is continuing to increase (Collier P. The bottom billion: why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it. Oxford University Press, New York, 2007; Henneberg S, The wealth gaps. Farmington Hills: Greenhaven Publishing, 2017). Today, approximately 8% of the world’s population owns approximately 85% of the world’s wealth, much of it held just by the upper 1% of the global population, whereas the “bottom” 92% of the world’s population hold somewhat less than 15% of global wealth (Burton J, 25 Highest income earning countries. World Atlas; Economics , April 25. Retrieved March 23, 2018 from https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-highest-incomes-in-the-world.html , 2017a; Countries with the lowest income in the world. World Atlas: Economics , April 25. Retrieved March 23, 2018 from https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/countries-with-the-lowest-income-in-the-world.html , 2017b; Frank RH, Falling behind: how rising inequality harms the middle class. University of California Press, Berkeley 2007; Piketty T, Capital in the twenty-first century (A. Goldhammer, Trans.). Belknap Press, Cambridge, 2017). Further, contemporary trends in the global wealth patterns contribute to a high sense of subjective ill-being among large segments of the global population, even within economically advanced countries (Clark A, Senik C, Happiness and economic growth: lessons from developing countries. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2017; Helliwell J, Layard R, Sachs J, World happiness report, 2017. Sustainable Development Solutions Network, New York, 2017). The present scenario can be improved upon however, but it will require a more equitable flow of net national wealth to a larger share of the world’s national and global populations (Estes RJ, Sirgy MJ, Chapter 20: Well-being from a global perspective. In R. J. Estes & M. J. Sirgy (Eds.), The pursuit of well-being: the untold global history. Springer, Cham, 2017b; Graham C Happiness around the world: the paradox of happy peasants and miserable millionaires. Oxford University Press, New York, 2012; Stiglitz JE, The price of inequality: how today’s divided society endangers our future. W.W. Norton Books, New York, 2013).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The geometry of growth: how wealth distribution patterns predict economic development

Global Inequality

Self-Interest and Similar Wealth Across Nations Equals World Peace

The Gini index or Gini coefficient is a statistical measure of distribution developed by the Italian statistician Corrado Gini in 1912. It is often used as a gauge of economic inequality, measuring income distribution or, less commonly, wealth distribution among a population. The coefficient ranges from 0 (or 0%) to 1 (or 100%), with 0 representing perfect equality and 1 representing perfect inequality. Values over 1 are theoretically possible due to negative income or wealth levels generated by selected countries ( Investopedia 2018 ).

See Thomas Kuhn ( 1996 ) for a fuller discussion of the range of revolutionary paradigms that drive the social policies of nations.

Baradaran, M. (2017). The color of money: Black banks and the racial wealth gap . Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Book Google Scholar

Berkeley Center for Religion Peace and World Affairs. (2018). Buddhism on wealth and poverty . Retrieved April 27, 2018 from https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/essays/buddhism-on-wealth-and-poverty

Brulé, G., & Veenhoven, R. (2017). The ‘10 excess’ phenomenon in responses to survey questions on happiness. Social Indicators Research, 131 (2), 853–870.

Article Google Scholar

Buddha, G. (500 BCE). Wealth, happiness, and satisfaction. Cited in Brainy Quotes . Retrieved May 20, 2018 from https://www.brainyquote.com/authors/buddha

Burton, J. (2017a, April 25). 25 Highest income earning countries. World Atlas; Economics . Retrieved March 23, 2018 from https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-highest-incomes-in-the-world.html

Burton, J. (2017b, April 25). Countries with the lowest income in the world. World Atlas: Economics . Retrieved March 23, 2018 from https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/countries-with-the-lowest-income-in-the-world.html

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). (2018). The world factbook, 2018. Washington: Department of State. Retrieved March 20, 2018 from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/

Censky, A. (2011). How the middle class became the underclass . CNN Money, February 16.

Google Scholar

Clark, A., & Senik, C. (2017). Happiness and economic growth: Lessons from developing countries . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Collier, P. (2007). The bottom billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it . New York: Oxford University Press.

Collins, M., & Bendinger, B. (2016). The rise of inequality & the decline of the middle class . London: First Flight Books.

Credit Suisse. (2017). Annual report, 2017 . Retrieved March 20, 2018 from http://publications.credit-suisse.com/index.cfm/publikationen-shop/annual-report/annual-report-2017/

Davies, J., Lluberas, R. & Shorrocks, A. (2017). Estimating the level and distribution of global wealth, 2000–2014. Review of Income and Wealth 63 (4): 731, 759. Retrieved May 25, 2018 from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/roiw.12318/

Earth Institute. (2018). Earth Institute videos . Retrieved March 1, 2018 from http://www.earth.columbia.edu/videos

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Redder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramowitz . New York: Academic.

Economy Watch. (2018). Economy, poverty, and GINI coefficients . Retrieved March 25, 2018 from http://www.economywatch.com/economic-statistics/

Essays, UK. (2013). The Impact of globalization on Income inequality . Retrieved from http://www.ukessays.com/essays/economics/impact-of-globalization-on-income-inequality-economics-essay.php?vref=1

Estes, R. J. (2007). Advancing quality of life in a turbulent world . Dordrecht/Berlin: Springer.

Estes, R. J. (2010). The world social situation: Development challenges at the outset of a new century. Social Indicators Research, 98 , 363–402.

Estes, R. J. (2012a). Economies in transition: Continuing challenges to quality of life. In K. Land, A. C. Michalos, & M. Joseph Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of quality of life research (pp. 433–457). Cham: Springer.

Estes, R. J. (2012b). Failed and failing states: Is quality of life possible? In K. Land, A. C. Michalos, & M. Joseph Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of quality of life research (pp. 555–580). Cham: Springer.

Estes, R. J. (2015a). Development trends among the world’s socially least developed countries: Reasons for cautious optimism. In B. Spooner (Ed.), Globalization: The crucial phase . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Estes, R. J. (2015b). Global change and quality of life indicators. In F. Maggino (Ed.), A life devoted to quality of life festschrift in honor of Alex C. Michalos (pp. 173–194). Cham: Springer.

Estes, R. J. (2015c). Trends in world social development: The search for global well-being. In W. Glatzer (Ed.), The global handbook of well-being: from the wealth of nations to the human well-being of nations . Cham: Springer.

Estes, R. J., & Sirgy, M. J. (2017). Chapter 20: Well-being from a global perspective. In R. J. Estes & M. J. Sirgy (Eds.), The pursuit of well-being: The untold global history . Cham: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Estes, R. J., & Sirgy, M. J. (2018). Advances in well-being: Toward a better world for all . London: Rowman and Littlefield.

Estes, R. J., & Tiliouine, H. (2014). Islamic development trends: From collective wishes to concerted actions. Social Indicators Research, 116 (1), 67–114.

Estes, R. J., & Tiliouine, H. (2016). Introduction. In Social progress in Islamic societies: Social, political, economic, and ideological challenges . Chapter 1. Dordrecht NL: Springer International Publishers.

Estes, R. J., & Zhou, H. M. (2014, December 4). A conceptual approach to the creation of public–private partnerships in social welfare. International Journal of Social Welfare, 24 (4), 348–363.

Estes, R. J., Sirgy, M. J., & Selian, A. (2017). Appendix C: Major worldwide accomplishments in well-being since 1900. In R. J. Estes & M. J. Sirgy (Eds.), The pursuit of well-being: The untold global history . Cham: Springer.

Fox, J. (2012). The economics of well-being. Harvard Business Review, 90 (1–2), 78–83.

Frank, R. H. (2007). Falling behind: How rising inequality harms the middle class . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Galasso, V.N. (2013). The drivers of economic inequality: A primer . Washington, DC: Oxfam USA. Retrieved April 3, 2017, from https://www.oxfamamerica.org/static/media/files/oxfam-drivers-of-economic-inequality.pdf

Gourevitch, P. (2008). The role of politics in economic development. Annual Review of Political Science, 11 , 137–159.

Graham, C. (2012). Happiness around the world: The paradox of happy peasants and miserable millionaires . New York: Oxford University Press.

Green, J. (2017, July 27). How much debt does the average person have? Managing your money. Retrieved February 12, 2018 from https://pocketsense.com/much-debt-average-person-8076005.html

Helliwell, J., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2017). World happiness report, 2017 . New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Henneberg, S. (2017). The wealth gaps . Farmington Hills: Greenhaven Publishing.

International Labour Organization (ILO). (2018). Statistics and databases . Retrieved February 28, 2018 from http://www.ilo.org/global/statistics-and-databases/lang%2D%2Den/index.htm

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2018). Managing debt vulnerabilities in low-income and developing countries . Washington: IMF. Retrieved March 23, 2018 from http://www.imf.org/external/index.htm

International Social Security Association (ISSA). (2018). Social security programs throughout the world . Geneva: ISSA.

Investopedia. (2018). Gini index retrieved April 1, 2018 from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/gini-index.asp#ixzz5Cmyg1UM0

Italian National Institute of Statistics. (2017). The 12 dimensions of well-being . Retrieved May 17, 2017, from http://www.istat.it/en/well-being-and-sustainability/well-being-measures/12-dimensions-of-well-being . Rome: Italian National Institute of Statistics.

Johansen, L. (2017). How to hygge: The Nordic secrets to a happy life . New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Krugman, P. (2003). The great unraveling: Losing our way in the new century . New York: W.W. Norton.

Kuhn, T. (1996). The structure of scientific revolutions (3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Layard, R. (2017). Making personal happiness and well-being a goal of public policy . London: London School of Economics. Retrieved May 15, 2017, from http://www.lse.ac.uk/researchAndExpertise/researchImpact/caseStudies/layard-happiness-well-being-public-policy.aspx

Lozada, C. (2017). Economic growth is reducing global poverty . Washington, DC: National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved April 1, 2017, from http://www.nber.org/digest/oct02/w8933.html

Møller, V., & Roberts, B. (2017). New beginnings in an ancient region: Well-being in Sub-Saharan Africa. In R. J. Estes & M. J. Sirgy (Eds.), The pursuit of human well-being: The untold global history (pp. 161–215). Cham: Springer.

Monaghan, A. (2012). US wealth inequality – top 0.1% worth as much as the bottom 90% . The Guardian, November 13. Retrieved January 25, 2018 from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/nov/13/us-wealth-inequality-top-01-worth-as-much-as-the-bottom-90

Myers, J. (2016). Which are the world’s fastest-growing economies? Geneva: World Economic Forum. Retrieved July 1, 2017, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/04/worlds-fastest-growing-economies/

New Scientist. (2016). The truth about migration: Rich countries need immigrants. New Scientist . April 6. Retrieved April 17, 2018 from https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg23030681-100-the-truth-about-migration-rich-countries-need-immigrants/

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2015). Net official development assistance by country as a percentage of gross national income in 2015 . Retrieved April 15, 2017, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_development_aid_country_donors

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2017a). Development aid rises again in 2016 but flows to poorest countries dip . Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Retrieved July 2, 2017, from http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/development-aid-rises-again-in-2016-but-flows-to-poorest-countries-dip.htm

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2017b). Economy: Developing countries set to account for nearly 60% of world GDP by 2030, according to new estimates . Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.