Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper

Writing a research paper is both an art and a skill, and knowing how to write the methods section of a research paper is the first crucial step in mastering scientific writing. If, like the majority of early career researchers, you believe that the methods section is the simplest to write and needs little in the way of careful consideration or thought, this article will help you understand it is not 1 .

We have all probably asked our supervisors, coworkers, or search engines “ how to write a methods section of a research paper ” at some point in our scientific careers, so you are not alone if that’s how you ended up here. Even for seasoned researchers, selecting what to include in the methods section from a wealth of experimental information can occasionally be a source of distress and perplexity.

Additionally, journal specifications, in some cases, may make it more of a requirement rather than a choice to provide a selective yet descriptive account of the experimental procedure. Hence, knowing these nuances of how to write the methods section of a research paper is critical to its success. The methods section of the research paper is not supposed to be a detailed heavy, dull section that some researchers tend to write; rather, it should be the central component of the study that justifies the validity and reliability of the research.

Are you still unsure of how the methods section of a research paper forms the basis of every investigation? Consider the last article you read but ignore the methods section and concentrate on the other parts of the paper . Now think whether you could repeat the study and be sure of the credibility of the findings despite knowing the literature review and even having the data in front of you. You have the answer!

Having established the importance of the methods section , the next question is how to write the methods section of a research paper that unifies the overall study. The purpose of the methods section , which was earlier called as Materials and Methods , is to describe how the authors went about answering the “research question” at hand. Here, the objective is to tell a coherent story that gives a detailed account of how the study was conducted, the rationale behind specific experimental procedures, the experimental setup, objects (variables) involved, the research protocol employed, tools utilized to measure, calculations and measurements, and the analysis of the collected data 2 .

In this article, we will take a deep dive into this topic and provide a detailed overview of how to write the methods section of a research paper . For the sake of clarity, we have separated the subject into various sections with corresponding subheadings.

Table of Contents

What is the methods section of a research paper ?

The methods section is a fundamental section of any paper since it typically discusses the ‘ what ’, ‘ how ’, ‘ which ’, and ‘ why ’ of the study, which is necessary to arrive at the final conclusions. In a research article, the introduction, which serves to set the foundation for comprehending the background and results is usually followed by the methods section, which precedes the result and discussion sections. The methods section must explicitly state what was done, how it was done, which equipment, tools and techniques were utilized, how were the measurements/calculations taken, and why specific research protocols, software, and analytical methods were employed.

Why is the methods section important?

The primary goal of the methods section is to provide pertinent details about the experimental approach so that the reader may put the results in perspective and, if necessary, replicate the findings 3 . This section offers readers the chance to evaluate the reliability and validity of any study. In short, it also serves as the study’s blueprint, assisting researchers who might be unsure about any other portion in establishing the study’s context and validity. The methods plays a rather crucial role in determining the fate of the article; an incomplete and unreliable methods section can frequently result in early rejections and may lead to numerous rounds of modifications during the publication process. This means that the reviewers also often use methods section to assess the reliability and validity of the research protocol and the data analysis employed to address the research topic. In other words, the purpose of the methods section is to demonstrate the research acumen and subject-matter expertise of the author(s) in their field.

Structure of methods section of a research paper

Similar to the research paper, the methods section also follows a defined structure; this may be dictated by the guidelines of a specific journal or can be presented in a chronological or thematic manner based on the study type. When writing the methods section , authors should keep in mind that they are telling a story about how the research was conducted. They should only report relevant information to avoid confusing the reader and include details that would aid in connecting various aspects of the entire research activity together. It is generally advisable to present experiments in the order in which they were conducted. This facilitates the logical flow of the research and allows readers to follow the progression of the study design.

It is also essential to clearly state the rationale behind each experiment and how the findings of earlier experiments informed the design or interpretation of later experiments. This allows the readers to understand the overall purpose of the study design and the significance of each experiment within that context. However, depending on the particular research question and method, it may make sense to present information in a different order; therefore, authors must select the best structure and strategy for their individual studies.

In cases where there is a lot of information, divide the sections into subheadings to cover the pertinent details. If the journal guidelines pose restrictions on the word limit , additional important information can be supplied in the supplementary files. A simple rule of thumb for sectioning the method section is to begin by explaining the methodological approach ( what was done ), describing the data collection methods ( how it was done ), providing the analysis method ( how the data was analyzed ), and explaining the rationale for choosing the methodological strategy. This is described in detail in the upcoming sections.

How to write the methods section of a research paper

Contrary to widespread assumption, the methods section of a research paper should be prepared once the study is complete to prevent missing any key parameter. Hence, please make sure that all relevant experiments are done before you start writing a methods section . The next step for authors is to look up any applicable academic style manuals or journal-specific standards to ensure that the methods section is formatted correctly. The methods section of a research paper typically constitutes materials and methods; while writing this section, authors usually arrange the information under each category.

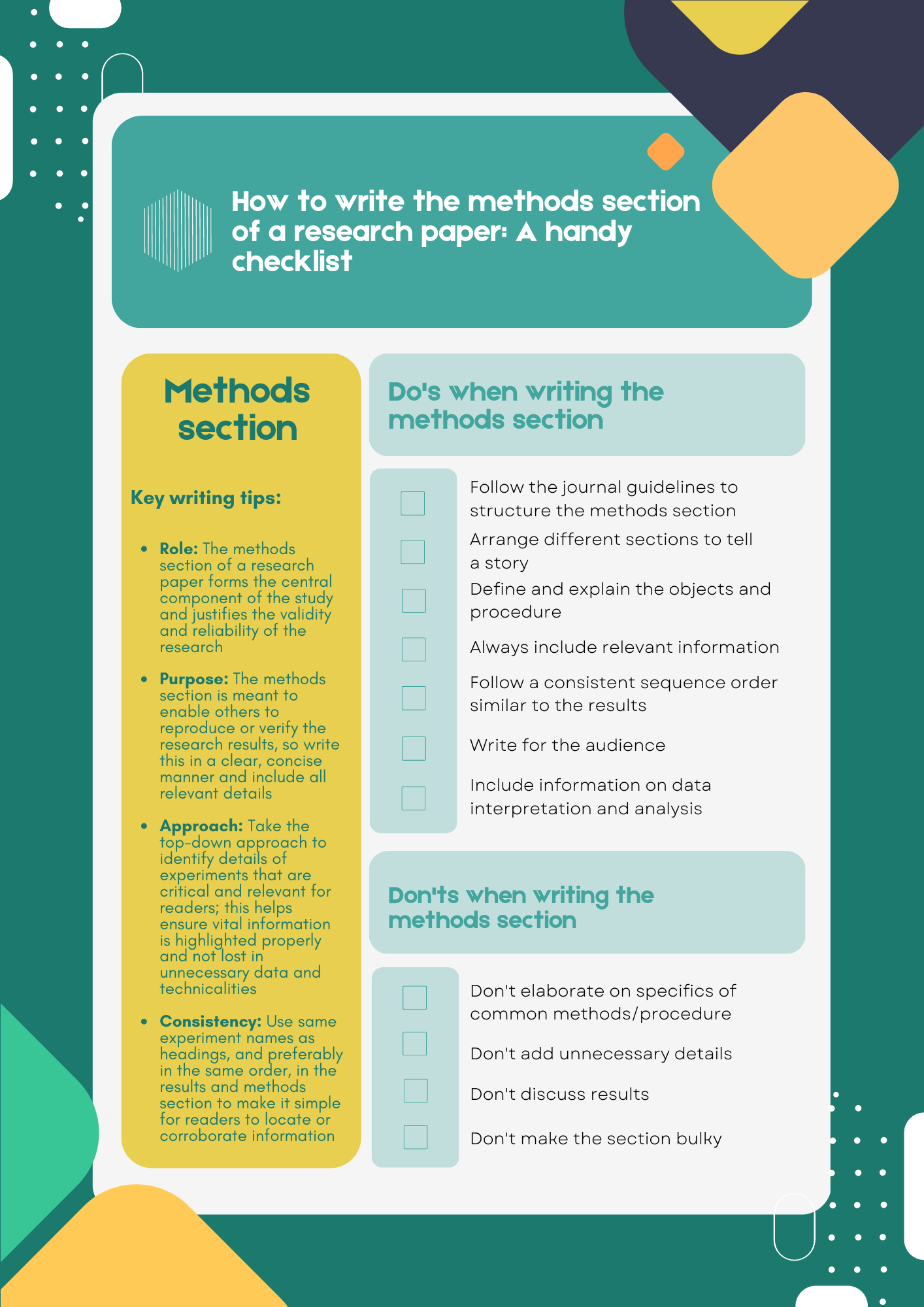

The materials category describes the samples, materials, treatments, and instruments, while experimental design, sample preparation, data collection, and data analysis are a part of the method category. According to the nature of the study, authors should include additional subsections within the methods section, such as ethical considerations like the declaration of Helsinki (for studies involving human subjects), demographic information of the participants, and any other crucial information that can affect the output of the study. Simply put, the methods section has two major components: content and format. Here is an easy checklist for you to consider if you are struggling with how to write the methods section of a research paper .

- Explain the research design, subjects, and sample details

- Include information on inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Mention ethical or any other permission required for the study

- Include information about materials, experimental setup, tools, and software

- Add details of data collection and analysis methods

- Incorporate how research biases were avoided or confounding variables were controlled

- Evaluate and justify the experimental procedure selected to address the research question

- Provide precise and clear details of each experiment

- Flowcharts, infographics, or tables can be used to present complex information

- Use past tense to show that the experiments have been done

- Follow academic style guides (such as APA or MLA ) to structure the content

- Citations should be included as per standard protocols in the field

Now that you know how to write the methods section of a research paper , let’s address another challenge researchers face while writing the methods section —what to include in the methods section . How much information is too much is not always obvious when it comes to trying to include data in the methods section of a paper. In the next section, we examine this issue and explore potential solutions.

What to include in the methods section of a research paper

The technical nature of the methods section occasionally makes it harder to present the information clearly and concisely while staying within the study context. Many young researchers tend to veer off subject significantly, and they frequently commit the sin of becoming bogged down in itty bitty details, making the text harder to read and impairing its overall flow. However, the best way to write the methods section is to start with crucial components of the experiments. If you have trouble deciding which elements are essential, think about leaving out those that would make it more challenging to comprehend the context or replicate the results. The top-down approach helps to ensure all relevant information is incorporated and vital information is not lost in technicalities. Next, remember to add details that are significant to assess the validity and reliability of the study. Here is a simple checklist for you to follow ( bonus tip: you can also make a checklist for your own study to avoid missing any critical information while writing the methods section ).

- Structuring the methods section : Authors should diligently follow journal guidelines and adhere to the specific author instructions provided when writing the methods section . Journals typically have specific guidelines for formatting the methods section ; for example, Frontiers in Plant Sciences advises arranging the materials and methods section by subheading and citing relevant literature. There are several standardized checklists available for different study types in the biomedical field, including CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) for randomized clinical trials, PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis) for systematic reviews and meta-analysis, and STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) for cohort, case-control, cross-sectional studies. Before starting the methods section , check the checklist available in your field that can function as a guide.

- Organizing different sections to tell a story : Once you are sure of the format required for structuring the methods section , the next is to present the sections in a logical manner; as mentioned earlier, the sections can be organized according to the chronology or themes. In the chronological arrangement, you should discuss the methods in accordance with how the experiments were carried out. An example of the method section of a research paper of an animal study should first ideally include information about the species, weight, sex, strain, and age. Next, the number of animals, their initial conditions, and their living and housing conditions should also be mentioned. Second, how the groups are assigned and the intervention (drug treatment, stress, or other) given to each group, and finally, the details of tools and techniques used to measure, collect, and analyze the data. Experiments involving animal or human subjects should additionally state an ethics approval statement. It is best to arrange the section using the thematic approach when discussing distinct experiments not following a sequential order.

- Define and explain the objects and procedure: Experimental procedure should clearly be stated in the methods section . Samples, necessary preparations (samples, treatment, and drug), and methods for manipulation need to be included. All variables (control, dependent, independent, and confounding) must be clearly defined, particularly if the confounding variables can affect the outcome of the study.

- Match the order of the methods section with the order of results: Though not mandatory, organizing the manuscript in a logical and coherent manner can improve the readability and clarity of the paper. This can be done by following a consistent structure throughout the manuscript; readers can easily navigate through the different sections and understand the methods and results in relation to each other. Using experiment names as headings for both the methods and results sections can also make it simpler for readers to locate specific information and corroborate it if needed.

- Relevant information must always be included: The methods section should have information on all experiments conducted and their details clearly mentioned. Ask the journal whether there is a way to offer more information in the supplemental files or external repositories if your target journal has strict word limitations. For example, Nature communications encourages authors to deposit their step-by-step protocols in an open-resource depository, Protocol Exchange which allows the protocols to be linked with the manuscript upon publication. Providing access to detailed protocols also helps to increase the transparency and reproducibility of the research.

- It’s all in the details: The methods section should meticulously list all the materials, tools, instruments, and software used for different experiments. Specify the testing equipment on which data was obtained, together with its manufacturer’s information, location, city, and state or any other stimuli used to manipulate the variables. Provide specifics on the research process you employed; if it was a standard protocol, cite previous studies that also used the protocol. Include any protocol modifications that were made, as well as any other factors that were taken into account when planning the study or gathering data. Any new or modified techniques should be explained by the authors. Typically, readers evaluate the reliability and validity of the procedures using the cited literature, and a widely accepted checklist helps to support the credibility of the methodology. Note: Authors should include a statement on sample size estimation (if applicable), which is often missed. It enables the reader to determine how many subjects will be required to detect the expected change in the outcome variables within a given confidence interval.

- Write for the audience: While explaining the details in the methods section , authors should be mindful of their target audience, as some of the rationale or assumptions on which specific procedures are based might not always be obvious to the audience, particularly for a general audience. Therefore, when in doubt, the objective of a procedure should be specified either in relation to the research question or to the entire protocol.

- Data interpretation and analysis : Information on data processing, statistical testing, levels of significance, and analysis tools and software should be added. Mention if the recommendations and expertise of an experienced statistician were followed. Also, evaluate and justify the preferred statistical method used in the study and its significance.

What NOT to include in the methods section of a research paper

To address “ how to write the methods section of a research paper ”, authors should not only pay careful attention to what to include but also what not to include in the methods section of a research paper . Here is a list of do not’s when writing the methods section :

- Do not elaborate on specifics of standard methods/procedures: You should refrain from adding unnecessary details of experiments and practices that are well established and cited previously. Instead, simply cite relevant literature or mention if the manufacturer’s protocol was followed.

- Do not add unnecessary details : Do not include minute details of the experimental procedure and materials/instruments used that are not significant for the outcome of the experiment. For example, there is no need to mention the brand name of the water bath used for incubation.

- Do not discuss the results: The methods section is not to discuss the results or refer to the tables and figures; save it for the results and discussion section. Also, focus on the methods selected to conduct the study and avoid diverting to other methods or commenting on their pros or cons.

- Do not make the section bulky : For extensive methods and protocols, provide the essential details and share the rest of the information in the supplemental files. The writing should be clear yet concise to maintain the flow of the section.

We hope that by this point, you understand how crucial it is to write a thoughtful and precise methods section and the ins and outs of how to write the methods section of a research paper . To restate, the entire purpose of the methods section is to enable others to reproduce the results or verify the research. We sincerely hope that this post has cleared up any confusion and given you a fresh perspective on the methods section .

As a parting gift, we’re leaving you with a handy checklist that will help you understand how to write the methods section of a research paper . Feel free to download this checklist and use or share this with those who you think may benefit from it.

References

- Bhattacharya, D. How to write the Methods section of a research paper. Editage Insights, 2018. https://www.editage.com/insights/how-to-write-the-methods-section-of-a-research-paper (2018).

- Kallet, R. H. How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper. Respiratory Care 49, 1229–1232 (2004). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15447808/

- Grindstaff, T. L. & Saliba, S. A. AVOIDING MANUSCRIPT MISTAKES. Int J Sports Phys Ther 7, 518–524 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3474299/

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

Back to School – Lock-in All Access Pack for a Year at the Best Price

Research Paper Appendix: Format and Examples

How To Write The Methodology Chapter

The what, why & how explained simply (with examples).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | September 2021 (Updated April 2023)

So, you’ve pinned down your research topic and undertaken a review of the literature – now it’s time to write up the methodology section of your dissertation, thesis or research paper . But what exactly is the methodology chapter all about – and how do you go about writing one? In this post, we’ll unpack the topic, step by step .

Overview: The Methodology Chapter

- The purpose of the methodology chapter

- Why you need to craft this chapter (really) well

- How to write and structure the chapter

- Methodology chapter example

- Essential takeaways

What (exactly) is the methodology chapter?

The methodology chapter is where you outline the philosophical underpinnings of your research and outline the specific methodological choices you’ve made. The point of the methodology chapter is to tell the reader exactly how you designed your study and, just as importantly, why you did it this way.

Importantly, this chapter should comprehensively describe and justify all the methodological choices you made in your study. For example, the approach you took to your research (i.e., qualitative, quantitative or mixed), who you collected data from (i.e., your sampling strategy), how you collected your data and, of course, how you analysed it. If that sounds a little intimidating, don’t worry – we’ll explain all these methodological choices in this post .

Why is the methodology chapter important?

The methodology chapter plays two important roles in your dissertation or thesis:

Firstly, it demonstrates your understanding of research theory, which is what earns you marks. A flawed research design or methodology would mean flawed results. So, this chapter is vital as it allows you to show the marker that you know what you’re doing and that your results are credible .

Secondly, the methodology chapter is what helps to make your study replicable. In other words, it allows other researchers to undertake your study using the same methodological approach, and compare their findings to yours. This is very important within academic research, as each study builds on previous studies.

The methodology chapter is also important in that it allows you to identify and discuss any methodological issues or problems you encountered (i.e., research limitations ), and to explain how you mitigated the impacts of these. Every research project has its limitations , so it’s important to acknowledge these openly and highlight your study’s value despite its limitations . Doing so demonstrates your understanding of research design, which will earn you marks. We’ll discuss limitations in a bit more detail later in this post, so stay tuned!

Need a helping hand?

How to write up the methodology chapter

First off, it’s worth noting that the exact structure and contents of the methodology chapter will vary depending on the field of research (e.g., humanities, chemistry or engineering) as well as the university . So, be sure to always check the guidelines provided by your institution for clarity and, if possible, review past dissertations from your university. Here we’re going to discuss a generic structure for a methodology chapter typically found in the sciences.

Before you start writing, it’s always a good idea to draw up a rough outline to guide your writing. Don’t just start writing without knowing what you’ll discuss where. If you do, you’ll likely end up with a disjointed, ill-flowing narrative . You’ll then waste a lot of time rewriting in an attempt to try to stitch all the pieces together. Do yourself a favour and start with the end in mind .

Section 1 – Introduction

As with all chapters in your dissertation or thesis, the methodology chapter should have a brief introduction. In this section, you should remind your readers what the focus of your study is, especially the research aims . As we’ve discussed many times on the blog, your methodology needs to align with your research aims, objectives and research questions. Therefore, it’s useful to frontload this component to remind the reader (and yourself!) what you’re trying to achieve.

In this section, you can also briefly mention how you’ll structure the chapter. This will help orient the reader and provide a bit of a roadmap so that they know what to expect. You don’t need a lot of detail here – just a brief outline will do.

Section 2 – The Methodology

The next section of your chapter is where you’ll present the actual methodology. In this section, you need to detail and justify the key methodological choices you’ve made in a logical, intuitive fashion. Importantly, this is the heart of your methodology chapter, so you need to get specific – don’t hold back on the details here. This is not one of those “less is more” situations.

Let’s take a look at the most common components you’ll likely need to cover.

Methodological Choice #1 – Research Philosophy

Research philosophy refers to the underlying beliefs (i.e., the worldview) regarding how data about a phenomenon should be gathered , analysed and used . The research philosophy will serve as the core of your study and underpin all of the other research design choices, so it’s critically important that you understand which philosophy you’ll adopt and why you made that choice. If you’re not clear on this, take the time to get clarity before you make any further methodological choices.

While several research philosophies exist, two commonly adopted ones are positivism and interpretivism . These two sit roughly on opposite sides of the research philosophy spectrum.

Positivism states that the researcher can observe reality objectively and that there is only one reality, which exists independently of the observer. As a consequence, it is quite commonly the underlying research philosophy in quantitative studies and is oftentimes the assumed philosophy in the physical sciences.

Contrasted with this, interpretivism , which is often the underlying research philosophy in qualitative studies, assumes that the researcher performs a role in observing the world around them and that reality is unique to each observer . In other words, reality is observed subjectively .

These are just two philosophies (there are many more), but they demonstrate significantly different approaches to research and have a significant impact on all the methodological choices. Therefore, it’s vital that you clearly outline and justify your research philosophy at the beginning of your methodology chapter, as it sets the scene for everything that follows.

Methodological Choice #2 – Research Type

The next thing you would typically discuss in your methodology section is the research type. The starting point for this is to indicate whether the research you conducted is inductive or deductive .

Inductive research takes a bottom-up approach , where the researcher begins with specific observations or data and then draws general conclusions or theories from those observations. Therefore these studies tend to be exploratory in terms of approach.

Conversely , d eductive research takes a top-down approach , where the researcher starts with a theory or hypothesis and then tests it using specific observations or data. Therefore these studies tend to be confirmatory in approach.

Related to this, you’ll need to indicate whether your study adopts a qualitative, quantitative or mixed approach. As we’ve mentioned, there’s a strong link between this choice and your research philosophy, so make sure that your choices are tightly aligned . When you write this section up, remember to clearly justify your choices, as they form the foundation of your study.

Methodological Choice #3 – Research Strategy

Next, you’ll need to discuss your research strategy (also referred to as a research design ). This methodological choice refers to the broader strategy in terms of how you’ll conduct your research, based on the aims of your study.

Several research strategies exist, including experimental , case studies , ethnography , grounded theory, action research , and phenomenology . Let’s take a look at two of these, experimental and ethnographic, to see how they contrast.

Experimental research makes use of the scientific method , where one group is the control group (in which no variables are manipulated ) and another is the experimental group (in which a specific variable is manipulated). This type of research is undertaken under strict conditions in a controlled, artificial environment (e.g., a laboratory). By having firm control over the environment, experimental research typically allows the researcher to establish causation between variables. Therefore, it can be a good choice if you have research aims that involve identifying causal relationships.

Ethnographic research , on the other hand, involves observing and capturing the experiences and perceptions of participants in their natural environment (for example, at home or in the office). In other words, in an uncontrolled environment. Naturally, this means that this research strategy would be far less suitable if your research aims involve identifying causation, but it would be very valuable if you’re looking to explore and examine a group culture, for example.

As you can see, the right research strategy will depend largely on your research aims and research questions – in other words, what you’re trying to figure out. Therefore, as with every other methodological choice, it’s essential to justify why you chose the research strategy you did.

Methodological Choice #4 – Time Horizon

The next thing you’ll need to detail in your methodology chapter is the time horizon. There are two options here: cross-sectional and longitudinal . In other words, whether the data for your study were all collected at one point in time (cross-sectional) or at multiple points in time (longitudinal).

The choice you make here depends again on your research aims, objectives and research questions. If, for example, you aim to assess how a specific group of people’s perspectives regarding a topic change over time , you’d likely adopt a longitudinal time horizon.

Another important factor to consider is simply whether you have the time necessary to adopt a longitudinal approach (which could involve collecting data over multiple months or even years). Oftentimes, the time pressures of your degree program will force your hand into adopting a cross-sectional time horizon, so keep this in mind.

Methodological Choice #5 – Sampling Strategy

Next, you’ll need to discuss your sampling strategy . There are two main categories of sampling, probability and non-probability sampling.

Probability sampling involves a random (and therefore representative) selection of participants from a population, whereas non-probability sampling entails selecting participants in a non-random (and therefore non-representative) manner. For example, selecting participants based on ease of access (this is called a convenience sample).

The right sampling approach depends largely on what you’re trying to achieve in your study. Specifically, whether you trying to develop findings that are generalisable to a population or not. Practicalities and resource constraints also play a large role here, as it can oftentimes be challenging to gain access to a truly random sample. In the video below, we explore some of the most common sampling strategies.

Methodological Choice #6 – Data Collection Method

Next up, you’ll need to explain how you’ll go about collecting the necessary data for your study. Your data collection method (or methods) will depend on the type of data that you plan to collect – in other words, qualitative or quantitative data.

Typically, quantitative research relies on surveys , data generated by lab equipment, analytics software or existing datasets. Qualitative research, on the other hand, often makes use of collection methods such as interviews , focus groups , participant observations, and ethnography.

So, as you can see, there is a tight link between this section and the design choices you outlined in earlier sections. Strong alignment between these sections, as well as your research aims and questions is therefore very important.

Methodological Choice #7 – Data Analysis Methods/Techniques

The final major methodological choice that you need to address is that of analysis techniques . In other words, how you’ll go about analysing your date once you’ve collected it. Here it’s important to be very specific about your analysis methods and/or techniques – don’t leave any room for interpretation. Also, as with all choices in this chapter, you need to justify each choice you make.

What exactly you discuss here will depend largely on the type of study you’re conducting (i.e., qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods). For qualitative studies, common analysis methods include content analysis , thematic analysis and discourse analysis . In the video below, we explain each of these in plain language.

For quantitative studies, you’ll almost always make use of descriptive statistics , and in many cases, you’ll also use inferential statistical techniques (e.g., correlation and regression analysis). In the video below, we unpack some of the core concepts involved in descriptive and inferential statistics.

In this section of your methodology chapter, it’s also important to discuss how you prepared your data for analysis, and what software you used (if any). For example, quantitative data will often require some initial preparation such as removing duplicates or incomplete responses . Similarly, qualitative data will often require transcription and perhaps even translation. As always, remember to state both what you did and why you did it.

Section 3 – The Methodological Limitations

With the key methodological choices outlined and justified, the next step is to discuss the limitations of your design. No research methodology is perfect – there will always be trade-offs between the “ideal” methodology and what’s practical and viable, given your constraints. Therefore, this section of your methodology chapter is where you’ll discuss the trade-offs you had to make, and why these were justified given the context.

Methodological limitations can vary greatly from study to study, ranging from common issues such as time and budget constraints to issues of sample or selection bias . For example, you may find that you didn’t manage to draw in enough respondents to achieve the desired sample size (and therefore, statistically significant results), or your sample may be skewed heavily towards a certain demographic, thereby negatively impacting representativeness .

In this section, it’s important to be critical of the shortcomings of your study. There’s no use trying to hide them (your marker will be aware of them regardless). By being critical, you’ll demonstrate to your marker that you have a strong understanding of research theory, so don’t be shy here. At the same time, don’t beat your study to death . State the limitations, why these were justified, how you mitigated their impacts to the best degree possible, and how your study still provides value despite these limitations .

Section 4 – Concluding Summary

Finally, it’s time to wrap up the methodology chapter with a brief concluding summary. In this section, you’ll want to concisely summarise what you’ve presented in the chapter. Here, it can be a good idea to use a figure to summarise the key decisions, especially if your university recommends using a specific model (for example, Saunders’ Research Onion ).

Importantly, this section needs to be brief – a paragraph or two maximum (it’s a summary, after all). Also, make sure that when you write up your concluding summary, you include only what you’ve already discussed in your chapter; don’t add any new information.

Methodology Chapter Example

In the video below, we walk you through an example of a high-quality research methodology chapter from a dissertation. We also unpack our free methodology chapter template so that you can see how best to structure your chapter.

Wrapping Up

And there you have it – the methodology chapter in a nutshell. As we’ve mentioned, the exact contents and structure of this chapter can vary between universities , so be sure to check in with your institution before you start writing. If possible, try to find dissertations or theses from former students of your specific degree program – this will give you a strong indication of the expectations and norms when it comes to the methodology chapter (and all the other chapters!).

Also, remember the golden rule of the methodology chapter – justify every choice ! Make sure that you clearly explain the “why” for every “what”, and reference credible methodology textbooks or academic sources to back up your justifications.

If you need a helping hand with your research methodology (or any other component of your research), be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through every step of the research journey. Until next time, good luck!

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

55 Comments

highly appreciated.

This was very helpful!

This was helpful

Thanks ,it is a very useful idea.

Thanks ,it is very useful idea.

Thank you so much, this information is very useful.

Thank you very much. I must say the information presented was succinct, coherent and invaluable. It is well put together and easy to comprehend. I have a great guide to create the research methodology for my dissertation.

Highly clear and useful.

I understand a bit on the explanation above. I want to have some coach but I’m still student and don’t have any budget to hire one. A lot of question I want to ask.

Thank you so much. This concluded my day plan. Thank you so much.

Thanks it was helpful

Great information. It would be great though if you could show us practical examples.

Thanks so much for this information. God bless and be with you

Thank you so so much. Indeed it was helpful

This is EXCELLENT!

I was totally confused by other explanations. Thank you so much!.

justdoing my research now , thanks for the guidance.

Thank uuuu! These contents are really valued for me!

This is powerful …I really like it

Highly useful and clear, thank you so much.

Highly appreciated. Good guide

That was helpful. Thanks

This is very useful.Thank you

Very helpful information. Thank you

This is exactly what I was looking for. The explanation is so detailed and easy to comprehend. Well done and thank you.

Great job. You just summarised everything in the easiest and most comprehensible way possible. Thanks a lot.

Thank you very much for the ideas you have given this will really help me a lot. Thank you and God Bless.

Such great effort …….very grateful thank you

Please accept my sincere gratitude. I have to say that the information that was delivered was congruent, concise, and quite helpful. It is clear and straightforward, making it simple to understand. I am in possession of an excellent manual that will assist me in developing the research methods for my dissertation.

Thank you for your great explanation. It really helped me construct my methodology paper.

thank you for simplifieng the methodoly, It was realy helpful

Very helpful!

Thank you for your great explanation.

The explanation I have been looking for. So clear Thank you

Thank you very much .this was more enlightening.

helped me create the in depth and thorough methodology for my dissertation

Thank you for the great explaination.please construct one methodology for me

I appreciate you for the explanation of methodology. Please construct one methodology on the topic: The effects influencing students dropout among schools for my thesis

This helped me complete my methods section of my dissertation with ease. I have managed to write a thorough and concise methodology!

its so good in deed

wow …what an easy to follow presentation. very invaluable content shared. utmost important.

Peace be upon you, I am Dr. Ahmed Khedr, a former part-time professor at Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt. I am currently teaching research methods, and I have been dealing with your esteemed site for several years, and I found that despite my long experience with research methods sites, it is one of the smoothest sites for evaluating the material for students, For this reason, I relied on it a lot in teaching and translated most of what was written into Arabic and published it on my own page on Facebook. Thank you all… Everything I posted on my page is provided with the names of the writers of Grad coach, the title of the article, and the site. My best regards.

A remarkably simple and useful guide, thank you kindly.

I real appriciate your short and remarkable chapter summary

Bravo! Very helpful guide.

Only true experts could provide such helpful, fantastic, and inspiring knowledge about Methodology. Thank you very much! God be with you and us all!

highly appreciate your effort.

This is a very well thought out post. Very informative and a great read.

THANKS SO MUCH FOR SHARING YOUR NICE IDEA

I love you Emma, you are simply amazing with clear explanations with complete information. GradCoach really helped me to do my assignment here in Auckland. Mostly, Emma make it so simple and enjoyable

Thank you very much for this informative and synthesised version.

thank you, It was a very informative presentation, you made it just to the point in a straightforward way .

Help me write a methodology on the topic “challenges faced by family businesses in Ghana

Well articulated, clear, and concise. I got a lot from this writings. Thanks

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Quantitative Data Analysis

9 Presenting the Results of Quantitative Analysis

Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur

This chapter provides an overview of how to present the results of quantitative analysis, in particular how to create effective tables for displaying quantitative results and how to write quantitative research papers that effectively communicate the methods used and findings of quantitative analysis.

Writing the Quantitative Paper

Standard quantitative social science papers follow a specific format. They begin with a title page that includes a descriptive title, the author(s)’ name(s), and a 100 to 200 word abstract that summarizes the paper. Next is an introduction that makes clear the paper’s research question, details why this question is important, and previews what the paper will do. After that comes a literature review, which ends with a summary of the research question(s) and/or hypotheses. A methods section, which explains the source of data, sample, and variables and quantitative techniques used, follows. Many analysts will include a short discussion of their descriptive statistics in the methods section. A findings section details the findings of the analysis, supported by a variety of tables, and in some cases graphs, all of which are explained in the text. Some quantitative papers, especially those using more complex techniques, will include equations. Many papers follow the findings section with a discussion section, which provides an interpretation of the results in light of both the prior literature and theory presented in the literature review and the research questions/hypotheses. A conclusion ends the body of the paper. This conclusion should summarize the findings, answering the research questions and stating whether any hypotheses were supported, partially supported, or not supported. Limitations of the research are detailed. Papers typically include suggestions for future research, and where relevant, some papers include policy implications. After the body of the paper comes the works cited; some papers also have an Appendix that includes additional tables and figures that did not fit into the body of the paper or additional methodological details. While this basic format is similar for papers regardless of the type of data they utilize, there are specific concerns relating to quantitative research in terms of the methods and findings that will be discussed here.

In the methods section, researchers clearly describe the methods they used to obtain and analyze the data for their research. When relying on data collected specifically for a given paper, researchers will need to discuss the sample and data collection; in most cases, though, quantitative research relies on pre-existing datasets. In these cases, researchers need to provide information about the dataset, including the source of the data, the time it was collected, the population, and the sample size. Regardless of the source of the data, researchers need to be clear about which variables they are using in their research and any transformations or manipulations of those variables. They also need to explain the specific quantitative techniques that they are using in their analysis; if different techniques are used to test different hypotheses, this should be made clear. In some cases, publications will require that papers be submitted along with any code that was used to produce the analysis (in SPSS terms, the syntax files), which more advanced researchers will usually have on hand. In many cases, basic descriptive statistics are presented in tabular form and explained within the methods section.

The findings sections of quantitative papers are organized around explaining the results as shown in tables and figures. Not all results are depicted in tables and figures—some minor or null findings will simply be referenced—but tables and figures should be produced for all findings to be discussed at any length. If there are too many tables and figures, some can be moved to an appendix after the body of the text and referred to in the text (e.g. “See Table 12 in Appendix A”).

Discussions of the findings should not simply restate the contents of the table. Rather, they should explain and interpret it for readers, and they should do so in light of the hypothesis or hypotheses that are being tested. Conclusions—discussions of whether the hypothesis or hypotheses are supported or not supported—should wait for the conclusion of the paper.

Creating Effective Tables

When creating tables to display the results of quantitative analysis, the most important goals are to create tables that are clear and concise but that also meet standard conventions in the field. This means, first of all, paring down the volume of information produced in the statistical output to just include the information most necessary for interpreting the results, but doing so in keeping with standard table conventions. It also means making tables that are well-formatted and designed, so that readers can understand what the tables are saying without struggling to find information. For example, tables (as well as figures such as graphs) need clear captions; they are typically numbered and referred to by number in the text. Columns and rows should have clear headings. Depending on the content of the table, formatting tools may need to be used to set off header rows/columns and/or total rows/columns; cell-merging tools may be necessary; and shading may be important in tables with many rows or columns.

Here, you will find some instructions for creating tables of results from descriptive, crosstabulation, correlation, and regression analysis that are clear, concise, and meet normal standards for data display in social science. In addition, after the instructions for creating tables, you will find an example of how a paper incorporating each table might describe that table in the text.

Descriptive Statistics

When presenting the results of descriptive statistics, we create one table with columns for each type of descriptive statistic and rows for each variable. Note, of course, that depending on level of measurement only certain descriptive statistics are appropriate for a given variable, so there may be many cells in the table marked with an — to show that this statistic is not calculated for this variable. So, consider the set of descriptive statistics below, for occupational prestige, age, highest degree earned, and whether the respondent was born in this country.

To display these descriptive statistics in a paper, one might create a table like Table 2. Note that for discrete variables, we use the value label in the table, not the value.

If we were then to discuss our descriptive statistics in a quantitative paper, we might write something like this (note that we do not need to repeat every single detail from the table, as readers can peruse the table themselves): This analysis relies on four variables from the 2021 General Social Survey: occupational prestige score, age, highest degree earned, and whether the respondent was born in the United States. Descriptive statistics for all four variables are shown in Table 2. The median occupational prestige score is 47, with a range from 16 to 80. 50% of respondents had occupational prestige scores scores between 35 and 59. The median age of respondents is 53, with a range from 18 to 89. 50% of respondents are between ages 37 and 66. Both variables have little skew. Highest degree earned ranges from less than high school to a graduate degree; the median respondent has earned an associate’s degree, while the modal response (given by 39.8% of the respondents) is a high school degree. 88.8% of respondents were born in the United States. CrosstabulationWhen presenting the results of a crosstabulation, we simplify the table so that it highlights the most important information—the column percentages—and include the significance and association below the table. Consider the SPSS output below.

Table 4 shows how a table suitable for include in a paper might look if created from the SPSS output in Table 3. Note that we use asterisks to indicate the significance level of the results: * means p < 0.05; ** means p < 0.01; *** means p < 0.001; and no stars mean p > 0.05 (and thus that the result is not significant). Also note than N is the abbreviation for the number of respondents.

If we were going to discuss the results of this crosstabulation in a quantitative research paper, the discussion might look like this: A crosstabulation of respondent’s class identification and their highest degree earned, with class identification as the independent variable, is significant, with a Spearman correlation of 0.419, as shown in Table 4. Among lower class and working class respondents, more than 50% had earned a high school degree. Less than 20% of poor respondents and less than 40% of working-class respondents had earned more than a high school degree. In contrast, the majority of middle class and upper class respondents had earned at least a bachelor’s degree. In fact, 50% of upper class respondents had earned a graduate degree. CorrelationWhen presenting a correlating matrix, one of the most important things to note is that we only present half the table so as not to include duplicated results. Think of the line through the table where empty cells exist to represent the correlation between a variable and itself, and include only the triangle of data either above or below that line of cells. Consider the output in Table 5.

Table 6 shows what the contents of Table 5 might look like when a table is constructed in a fashion suitable for publication.

If we were to discuss the results of this bivariate correlation analysis in a quantitative paper, the discussion might look like this: Bivariate correlations were run among variables measuring age, occupational prestige, the highest year of school respondents completed, and family income in constant 1986 dollars, as shown in Table 6. Correlations between age and highest year of school completed and between age and family income are not significant. All other correlations are positive and significant at the p<0.001 level. The correlation between age and occupational prestige is weak; the correlations between income and occupational prestige and between income and educational attainment are moderate, and the correlation between education and occupational prestige is strong. To present the results of a regression, we create one table that includes all of the key information from the multiple tables of SPSS output. This includes the R 2 and significance of the regression, either the B or the beta values (different analysts have different preferences here) for each variable, and the standard error and significance of each variable. Consider the SPSS output in Table 7.

The regression output in shown in Table 7 contains a lot of information. We do not include all of this information when making tables suitable for publication. As can be seen in Table 8, we include the Beta (or the B), the standard error, and the significance asterisk for each variable; the R 2 and significance for the overall regression; the degrees of freedom (which tells readers the sample size or N); and the constant; along with the key to p/significance values.

If we were to discuss the results of this regression in a quantitative paper, the results might look like this: Table 8 shows the results of a regression in which age, occupational prestige, and highest year of school completed are the independent variables and family income is the dependent variable. The regression results are significant, and all of the independent variables taken together explain 15.6% of the variance in family income. Age is not a significant predictor of income, while occupational prestige and educational attainment are. Educational attainment has a larger effect on family income than does occupational prestige. For every year of additional education attained, family income goes up on average by $3,988.545; for every one-unit increase in occupational prestige score, family income goes up on average by $522.887. [1]

Social Data Analysis Copyright © 2021 by Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted. Writing Quantitative Research Studies

1751 Accesses 1 Citations Summarizing quantitative data and its effective presentation and discussion can be challenging for students and researchers. This chapter provides a framework for adequately reporting findings from quantitative analysis in a research study for those contemplating to write a research paper. The rationale underpinning the reporting methods to maintain the credibility and integrity of quantitative studies is outlined. Commonly used terminologies in empirical studies are defined and discussed with suitable examples. Key elements that build consistency between different sections (background, methods, results, and the discussion) of a research study using quantitative methods in a journal article are explicated. Specifically, recommended standard guidelines for randomized controlled trials and observational studies for reporting and discussion of findings from quantitative studies are elaborated. Key aspects of methodology that include describing the study population, sampling strategy, data collection methods, measurements/variables, and statistical analysis which informs the quality of a study from the reviewer’s perspective are described. Effective use of references in the methods section to strengthen the rationale behind specific statistical techniques and choice of measures has been highlighted with examples. Identifying ways in which data can be most succinctly and effectively summarized in tables and graphs according to their suitability and purpose of information is also detailed in this chapter. Strategies to present and discuss the quantitative findings in a structured discussion section are also provided. Overall, the chapter provides the readers with a comprehensive set of tools to identify key strategies to be considered when reporting quantitative research. This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access. Access this chapterSubscribe and save.

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout Purchases are for personal use only Institutional subscriptions Similar content being viewed by others Quantitative Research Case Study 3: Application of Quantitative MethodologyBhaumik S, Arora M, Singh A, Sargent JD. Impact of entertainment media smoking on adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;6:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011720 . Article Google Scholar Dickersin K, Manheimer E, Wieland S, Robinson KA, Lefebvre C, McDonald S. Development of the Cochrane Collaboration’s CENTRAL register of controlled clinical trials. Eval Health Prof. 2002;25(1):38–64. Google Scholar Docherty M, Smith R. The case for structuring the discussion of scientific papers: much the same as that for structuring abstracts. Br Med J. 1999;318(7193):1224–5. Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10(1):37–48. Horton R. The rhetoric of research. Br Med J. 1995;310(6985):985–7. Kool B, Ziersch A, Robinson P, Wolfenden L, Lowe JB. The ‘Seven deadly sins’ of rejected papers. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40(1):3–4. Mannocci A, Saulle R, Colamesta V, D’Aguanno S, Giraldi G, Maffongelli E, et al. What is the impact of reporting guidelines on public health journals in Europe? The case of STROBE, CONSORT and PRISMA. J Public Health. 2015;37(4):737–40. Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “to whom do the results of this trial apply?”. Lancet. 2005;365(9453):82–93. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e1000251. Szklo M. Quality of scientific articles. Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40 Spec no:30–5. Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e297. Weiss NS, Koepsell TD, Psaty BM. Generalizability of the results of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(2):133–5. Singh A, Gupta A, Peres MA, Watt RG, Tsakos G, Mathur MR. Association between tooth loss and hypertension among a primarily rural middle aged and older Indian adult population. J Public Health Dent. 2016;76:198–205. Download references Author informationAuthors and affiliations. Centre for Health Equity, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia Ankur Singh School of Public Health, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA, Australia Adyya Gupta Australian Research Centre for Population Oral Health (ARCPOH), Adelaide Dental School, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA, Australia Karen G. Peres You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar Corresponding authorCorrespondence to Ankur Singh . Editor informationEditors and affiliations. School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia Pranee Liamputtong Rights and permissionsReprints and permissions Copyright information© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. About this entryCite this entry. Singh, A., Gupta, A., Peres, K.G. (2019). Writing Quantitative Research Studies. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_117 Download citationDOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_117 Published : 13 January 2019 Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore Print ISBN : 978-981-10-5250-7 Online ISBN : 978-981-10-5251-4 eBook Packages : Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences Share this entryAnyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Policies and ethics

A Scholar’s Guide to Writing the Methods Section of a Research PaperTable of contents

In the vast realm of academic writing, the research paper stands as a testament to a scholar’s systematic exploration of a particular subject. Each section of the paper plays a pivotal role, knitting together the fabric of the study. While the introduction sets the stage and the results showcase the findings, it is the Methods section that forms the backbone, providing a clear roadmap for any reader or researcher wishing to replicate or understand the study’s inner workings. As pivotal as it is, crafting an impeccable Methods section often poses challenges for researchers. This article aims to elucidate the intricacies of constructing a robust Methodology section in a research paper. After reading our guide, you will:

Now, let’s take a detailed look at these points! What Is the Methods Section of a Research PaperDo you have any questions about how to write the Methodology? Firstly, let’s define this section for research. The Methods or Methodology section of the research paper gives the road map for how the research was conducted. A well-crafted Methods section not only guides the researcher but also helps other scholars understand, replicate your study. In other words, it’s like a recipe in a cookbook. If you want others to recreate your experiment or study, this section tells them exactly how you did it. It includes details about the steps you took, the tools or ingredients you used, and how you measured your results. This way, others can see if they get the same outcome when they follow your “recipe” or if they can trust your findings. This means that the Methodology should be thoughtfully planned, executed, and reported. The reader should understand the basic research structure and the steps taken to conduct the study, including the research design, methods, gathered data, and data analysis techniques used. The Methodology of a research study is essential for several reasons: Validity and Reliability: A well-defined Methodology provides the foundation for the criteria and reliability of the study, particularly in addressing the research question for research. It helps to ensure that the research is conducted in a systematic and controlled manner and that the results are accurate and trustworthy. Replicability: It allows other researchers to understand and replicate the study, which is important for building on existing knowledge and advancing the field. Clarity and Transparency: A clear and concise Methods part makes it easier for readers to understand the research process and evaluate the results. This helps to increase transparency and build trust in the findings. Justification of Approach: The research methodology provides a rationale for the approach taken, including why certain methods and techniques were chosen and how they relate to the question for research. Evidence of Rigor: A well-executed research methodology demonstrates the rigor and thoroughness of the study, which is important for establishing the credibility of the results. Methodology vs. MethodsIn rigorous academic and research contexts, there is a distinction between “methods” and “methodology.” However, outside of strict scholarly circles or in more informal discussions, there might be some overlapping use. The “methods” generally refer to the specific techniques or procedures, while “methodology” dives into the theoretical framework and rationale behind those techniques. It’s essential to use the terms correctly in formal academic and research writings to maintain clarity and precision. Nevertheless, in many research papers, the specifics of the methods (the “how”) are the primary focus, and the theoretical rationale (the “why”) might be briefly touched upon within the same section. Structure of the Methodology In A Research PaperThe Methods section typically begins with a brief overview of its contents and a reiteration of the research question. This is followed by a description of the participants, detailing their demographics, and how they were recruited. The materials or apparatus used are then specified, from tools to equipment, with any unique specifications highlighted. The core of the Methods section is the procedure, a step-by-step account of the study, from experimental tasks to the sequence of operations. This is complemented by an explanation of the experimental design, where the type of research design is described, along with the variables involved. Detailed accounts of how data was gathered, whether through surveys, interviews, or other methods, are provided, ensuring the reader understands the data collection nuances. Critical to the credibility of the study is the section on statistical analysis, which reveals how data was processed, what statistical tests were used, and the software or tools employed. If the research involved humans or animals, the ethical considerations section becomes pivotal. Here, measures taken to ensure participants’ rights, confidentiality, and informed consent are documented. Towards the end, the limitations of the study are discussed, providing insights into potential biases or constraints faced during the research process. The section wraps up with a brief recap, emphasizing the methods’ role in ensuring the study’s integrity and reproducibility. According to APA style , there are three major subsections to report here: participants, apparatus, and procedure. ParticipantsThis segment reports the characteristics of the participants involved in the experiment, the method of sampling, and the sample size.

This details the demography of the respondents that may be relevant to the experiment. This includes but is not limited to age, gender, ethnicity or race, religion, level of education, socioeconomic status, origin of the population, and any restrictions. ✏️Example: Fifty female undergraduate students between the ages of 19 and 23 participated in the experiment. All were sophomores in the Faculty of Engineering and native English speakers who lived on the university campus. The participants were separated into two groups of 25 students, each without any determining criteria. This study was conducted at the University of Alabama, USA .

Identify the selection criteria and whether the sample was random or not. Include it if you have access to data informing the percentage of people invited to participate and how many agreed. You should also report the selection mode; was it voluntary, or were the participants assigned to the study? Additionally, identify any compensation that was provided to participants. The ethics board was petitioned, and approval was granted before the recruitment of participants commenced. All the female sophomores from the faculty of Engineering at the University of Alabama, USA, were invited to participate, and those who did were self-selected. In liaison with department heads, the students were offered additional credits in a faculty-wide course as compensation for their time.

Identify the sample size per group, the statistical power you aimed to attain, whether you could attain it, and the analyses you used to determine the figures you arrived at. You should also include whether the final sample you got was what you initially required. The required power for this experiment to detect a 15% effect at a significance level of .08 was 75%. To achieve this, we needed 25 participants in each group. The final sample met these conditions. This subsection describes the materials and apparatus used in the experiment. It calls for detailed information on all devices and techniques used to collate data, measure suitable variables, and reach analysis, including tests and surveys. You must include a proper count of the number of apparatus used, their names, model number, manufacturer, reliability, and validity. For surveys, including the meaning of the formats used and the number of questions asked. A survey that consisted of 15 multiple-choice questions was carried out to determine the safety of female students on the school campus. The participants were asked to answer the questions using a 5-point grading system (1 = Extremely True and 5 = Extremely False). This includes the conditions in which data was collated, instructions given to the participants, and data analysis methods. The two groups of participants were placed in two different classrooms at individual desks and given 10 minutes to answer the questions. They were instructed to give the first answers they thought of without thinking too deeply. Each group had a supervisor attached to it. Writing a research paper requires a great deal of skill and knowledge, so if you need help compiling the Methods section of your paper, consider using a professional coursework writing service to help you. Advice On How to Write the Methods SectionYou already know the relevance of the Methods part to your research paper. Additionally, you must adhere to formatting guidelines specific for your field. If you cannot write according to standards, you can use a research paper writing service to get good results. Go for one with good reviews and a super online reputation. Here are some more tips for a concise and meticulously written Methodology:

Methods and Results Should MatchIn the Methods section, the results obtained should be discussed based on the experimental procedures used. Explain the methodology behind the techniques used to acquire all the observations and results of the experiment in the right order. You can create a detailed flowchart or block flow diagram (BFD) to easily describe the complexities of the study and its procedures to the reader. Preparing the Statistical Methods SubsectionThe statistical analysis subsection comes at the end of the Methods section. It includes a thorough description of the analyzed data to arrive at the results and conclusion. Due to its technicality, it might be a little difficult and daunting to write. If this is the case, you can get the statistician who participated in the study to write it. Here, you must indicate all the data variables, including the control variables, dependent and independent variables, and any potentially irrelevant variables that could affect your results and conclusion. Specify the exact tests carried out on the different types of data you have, the requirements you tested, like distribution normality, and all assumptions you initially applied. You should also include all data alterations, possible mix-ups, confidence intervals or significance levels used, techniques for data analysis, and ensuing statistical tests that were employed. Furthermore, specify any criteria particular to the experiment, like set baselines and any specific software used to conduct the statistical analysis. The Style of the MethodologyAs mentioned earlier, it aims to explain how and why the experiment was carried out so that readers can understand it and possibly repeat the procedure. Therefore, it is essential to be aware of your audience so you can modify your writing based on what they know and explain technical terms where necessary. If you are finding it difficult to write in the appropriate style, you can buy a research paper written by writers. You can find these writers on several platforms for college essays. The methodology should read as though you describe the experiment to your reader. For this reason, it should be worded in third-person constructs and a passive voice. For example, you should use “We carried out a survey” and not “I carried out a survey.” Since the experiment has already been carried out, you must write the entire section in the past tense. Key Information to Include in MethodologyNow you know what the Methods section is, what information must be included in this segment of your paper? Here’s a summary of the things you need to include:

Helping Hand in Writing Methodology ChapterIt can be challenging for researchers to adequately describe their study methodologies and strategies when writing the methodology chapter of a research report. Organizing and presenting complex material, retaining clarity and conciseness, and describing technical processes or approaches are among the usual difficulties. To overcome these challenges, researchers can consider seeking feedback from peers, utilizing a https://papersowl.com/ or editor, and thoroughly reviewing and revising their methodology chapter multiple times. With the help of an essay writing service, you can ensure that your research paper is accurate and successful. Which information is not included in the methodology section of a research article?Where does the research methodology section go in a research paper, what is the difference between qualitative and quantitative methods, readers also enjoyed.  WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries! We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy. An official website of the United States government The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site. The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .