How to Do Comparative Analysis in Research ( Examples )

Comparative analysis is a method that is widely used in social science . It is a method of comparing two or more items with an idea of uncovering and discovering new ideas about them. It often compares and contrasts social structures and processes around the world to grasp general patterns. Comparative analysis tries to understand the study and explain every element of data that comparing.

Most social scientists are involved in comparative analysis. Macfarlane has thought that “On account of history, the examinations are typically on schedule, in that of other sociologies, transcendently in space. The historian always takes their society and compares it with the past society, and analyzes how far they differ from each other.

The comparative method of social research is a product of 19 th -century sociology and social anthropology. Sociologists like Emile Durkheim, Herbert Spencer Max Weber used comparative analysis in their works. For example, Max Weber compares the protestant of Europe with Catholics and also compared it with other religions like Islam, Hinduism, and Confucianism.

To do a systematic comparison we need to follow different elements of the method.

In social science, we can do comparisons in different ways. It is merely different based on the topic, the field of study. Like Emile Durkheim compare societies as organic solidarity and mechanical solidarity. The famous sociologist Emile Durkheim provides us with three different approaches to the comparative method. Which are;

2 . The unit of comparison

3. The motive of comparison

As another method of study, a comparative analysis is one among them for the social scientist. The researcher or the person who does the comparative method must know for what grounds they taking the comparative method. They have to consider the strength, limitations, weaknesses, etc. He must have to know how to do the analysis.

Steps of the comparative method

1. Setting up of a unit of comparison

As mentioned earlier, the first step is to consider and determine the unit of comparison for your study. You must consider all the dimensions of your unit. This is where you put the two things you need to compare and to properly analyze and compare it. It is not an easy step, we have to systematically and scientifically do this with proper methods and techniques. You have to build your objectives, variables and make some assumptions or ask yourself about what you need to study or make a hypothesis for your analysis.

The grounds of comparison should be understandable for the reader. You must acknowledge why you selected these units for your comparison. For example, it is quite natural that a person who asks why you choose this what about another one? What is the reason behind choosing this particular society? If a social scientist chooses primitive Asian society and primitive Australian society for comparison, he must acknowledge the grounds of comparison to the readers. The comparison of your work must be self-explanatory without any complications.

The main element of the comparative analysis is the thesis or the report. The report is the most important one that it must contain all your frame of reference. It must include all your research questions, objectives of your topic, the characteristics of your two units of comparison, variables in your study, and last but not least the finding and conclusion must be written down. The findings must be self-explanatory because the reader must understand to what extent did they connect and what are their differences. For example, in Emile Durkheim’s Theory of Division of Labour, he classified organic solidarity and Mechanical solidarity . In which he means primitive society as Mechanical solidarity and modern society as Organic Solidarity. Like that you have to mention what are your findings in the thesis.

Your paper must link each point in the argument. Without that the reader does not understand the logical and rational advance in your analysis. In a comparative analysis, you need to compare the ‘x’ and ‘y’ in your paper. (x and y mean the two-unit or things in your comparison). To do that you can use likewise, similarly, on the contrary, etc. For example, if we do a comparison between primitive society and modern society we can say that; ‘in the primitive society the division of labour is based on gender and age on the contrary (or the other hand), in modern society, the division of labour is based on skill and knowledge of a person.

Demerits of comparison

Comparative analysis is not always successful. It has some limitations. The broad utilization of comparative analysis can undoubtedly cause the feeling that this technique is a solidly settled, smooth, and unproblematic method of investigation, which because of its undeniable intelligent status can produce dependable information once some specialized preconditions are met acceptably.

One more basic issue with broad ramifications concerns the decision of the units being analyzed. The primary concern is that a long way from being a guiltless as well as basic assignment, the decision of comparison units is a basic and precarious issue. The issue with this sort of comparison is that in such investigations the depictions of the cases picked for examination with the principle one will in general turn out to be unreasonably streamlined, shallow, and stylised with contorted contentions and ends as entailment.

However, a comparative analysis is as yet a strategy with exceptional benefits, essentially due to its capacity to cause us to perceive the restriction of our psyche and check against the weaknesses and hurtful results of localism and provincialism. We may anyway have something to gain from history specialists’ faltering in utilizing comparison and from their regard for the uniqueness of settings and accounts of people groups. All of the above, by doing the comparison we discover the truths the underlying and undiscovered connection, differences that exist in society.

What is comparative analysis? A complete guide

Last updated

18 April 2023

Reviewed by

Jean Kaluza

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Comparative analysis is a valuable tool for acquiring deep insights into your organization’s processes, products, and services so you can continuously improve them.

Similarly, if you want to streamline, price appropriately, and ultimately be a market leader, you’ll likely need to draw on comparative analyses quite often.

When faced with multiple options or solutions to a given problem, a thorough comparative analysis can help you compare and contrast your options and make a clear, informed decision.

If you want to get up to speed on conducting a comparative analysis or need a refresher, here’s your guide.

Make comparative analysis less tedious

Dovetail streamlines comparative analysis to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What exactly is comparative analysis?

A comparative analysis is a side-by-side comparison that systematically compares two or more things to pinpoint their similarities and differences. The focus of the investigation might be conceptual—a particular problem, idea, or theory—or perhaps something more tangible, like two different data sets.

For instance, you could use comparative analysis to investigate how your product features measure up to the competition.

After a successful comparative analysis, you should be able to identify strengths and weaknesses and clearly understand which product is more effective.

You could also use comparative analysis to examine different methods of producing that product and determine which way is most efficient and profitable.

The potential applications for using comparative analysis in everyday business are almost unlimited. That said, a comparative analysis is most commonly used to examine

Emerging trends and opportunities (new technologies, marketing)

Competitor strategies

Financial health

Effects of trends on a target audience

Free AI content analysis generator

Make sense of your research by automatically summarizing key takeaways through our free content analysis tool.

- Why is comparative analysis so important?

Comparative analysis can help narrow your focus so your business pursues the most meaningful opportunities rather than attempting dozens of improvements simultaneously.

A comparative approach also helps frame up data to illuminate interrelationships. For example, comparative research might reveal nuanced relationships or critical contexts behind specific processes or dependencies that wouldn’t be well-understood without the research.

For instance, if your business compares the cost of producing several existing products relative to which ones have historically sold well, that should provide helpful information once you’re ready to look at developing new products or features.

- Comparative vs. competitive analysis—what’s the difference?

Comparative analysis is generally divided into three subtypes, using quantitative or qualitative data and then extending the findings to a larger group. These include

Pattern analysis —identifying patterns or recurrences of trends and behavior across large data sets.

Data filtering —analyzing large data sets to extract an underlying subset of information. It may involve rearranging, excluding, and apportioning comparative data to fit different criteria.

Decision tree —flowcharting to visually map and assess potential outcomes, costs, and consequences.

In contrast, competitive analysis is a type of comparative analysis in which you deeply research one or more of your industry competitors. In this case, you’re using qualitative research to explore what the competition is up to across one or more dimensions.

For example

Service delivery —metrics like the Net Promoter Scores indicate customer satisfaction levels.

Market position — the share of the market that the competition has captured.

Brand reputation —how well-known or recognized your competitors are within their target market.

- Tips for optimizing your comparative analysis

Conduct original research

Thorough, independent research is a significant asset when doing comparative analysis. It provides evidence to support your findings and may present a perspective or angle not considered previously.

Make analysis routine

To get the maximum benefit from comparative research, make it a regular practice, and establish a cadence you can realistically stick to. Some business areas you could plan to analyze regularly include:

Profitability

Competition

Experiment with controlled and uncontrolled variables

In addition to simply comparing and contrasting, explore how different variables might affect your outcomes.

For example, a controllable variable would be offering a seasonal feature like a shopping bot to assist in holiday shopping or raising or lowering the selling price of a product.

Uncontrollable variables include weather, changing regulations, the current political climate, or global pandemics.

Put equal effort into each point of comparison

Most people enter into comparative research with a particular idea or hypothesis already in mind to validate. For instance, you might try to prove the worthwhileness of launching a new service. So, you may be disappointed if your analysis results don’t support your plan.

However, in any comparative analysis, try to maintain an unbiased approach by spending equal time debating the merits and drawbacks of any decision. Ultimately, this will be a practical, more long-term sustainable approach for your business than focusing only on the evidence that favors pursuing your argument or strategy.

Writing a comparative analysis in five steps

To put together a coherent, insightful analysis that goes beyond a list of pros and cons or similarities and differences, try organizing the information into these five components:

1. Frame of reference

Here is where you provide context. First, what driving idea or problem is your research anchored in? Then, for added substance, cite existing research or insights from a subject matter expert, such as a thought leader in marketing, startup growth, or investment

2. Grounds for comparison Why have you chosen to examine the two things you’re analyzing instead of focusing on two entirely different things? What are you hoping to accomplish?

3. Thesis What argument or choice are you advocating for? What will be the before and after effects of going with either decision? What do you anticipate happening with and without this approach?

For example, “If we release an AI feature for our shopping cart, we will have an edge over the rest of the market before the holiday season.” The finished comparative analysis will weigh all the pros and cons of choosing to build the new expensive AI feature including variables like how “intelligent” it will be, what it “pushes” customers to use, how much it takes off the plates of customer service etc.

Ultimately, you will gauge whether building an AI feature is the right plan for your e-commerce shop.

4. Organize the scheme Typically, there are two ways to organize a comparative analysis report. First, you can discuss everything about comparison point “A” and then go into everything about aspect “B.” Or, you alternate back and forth between points “A” and “B,” sometimes referred to as point-by-point analysis.

Using the AI feature as an example again, you could cover all the pros and cons of building the AI feature, then discuss the benefits and drawbacks of building and maintaining the feature. Or you could compare and contrast each aspect of the AI feature, one at a time. For example, a side-by-side comparison of the AI feature to shopping without it, then proceeding to another point of differentiation.

5. Connect the dots Tie it all together in a way that either confirms or disproves your hypothesis.

For instance, “Building the AI bot would allow our customer service team to save 12% on returns in Q3 while offering optimizations and savings in future strategies. However, it would also increase the product development budget by 43% in both Q1 and Q2. Our budget for product development won’t increase again until series 3 of funding is reached, so despite its potential, we will hold off building the bot until funding is secured and more opportunities and benefits can be proved effective.”

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

Gen ed writes, writing across the disciplines at harvard college.

- Comparative Analysis

What It Is and Why It's Useful

Comparative analysis asks writers to make an argument about the relationship between two or more texts. Beyond that, there's a lot of variation, but three overarching kinds of comparative analysis stand out:

- Coordinate (A ↔ B): In this kind of analysis, two (or more) texts are being read against each other in terms of a shared element, e.g., a memoir and a novel, both by Jesmyn Ward; two sets of data for the same experiment; a few op-ed responses to the same event; two YA books written in Chicago in the 2000s; a film adaption of a play; etc.

- Subordinate (A → B) or (B → A ): Using a theoretical text (as a "lens") to explain a case study or work of art (e.g., how Anthony Jack's The Privileged Poor can help explain divergent experiences among students at elite four-year private colleges who are coming from similar socio-economic backgrounds) or using a work of art or case study (i.e., as a "test" of) a theory's usefulness or limitations (e.g., using coverage of recent incidents of gun violence or legislation un the U.S. to confirm or question the currency of Carol Anderson's The Second ).

- Hybrid [A → (B ↔ C)] or [(B ↔ C) → A] , i.e., using coordinate and subordinate analysis together. For example, using Jack to compare or contrast the experiences of students at elite four-year institutions with students at state universities and/or community colleges; or looking at gun culture in other countries and/or other timeframes to contextualize or generalize Anderson's main points about the role of the Second Amendment in U.S. history.

"In the wild," these three kinds of comparative analysis represent increasingly complex—and scholarly—modes of comparison. Students can of course compare two poems in terms of imagery or two data sets in terms of methods, but in each case the analysis will eventually be richer if the students have had a chance to encounter other people's ideas about how imagery or methods work. At that point, we're getting into a hybrid kind of reading (or even into research essays), especially if we start introducing different approaches to imagery or methods that are themselves being compared along with a couple (or few) poems or data sets.

Why It's Useful

In the context of a particular course, each kind of comparative analysis has its place and can be a useful step up from single-source analysis. Intellectually, comparative analysis helps overcome the "n of 1" problem that can face single-source analysis. That is, a writer drawing broad conclusions about the influence of the Iranian New Wave based on one film is relying entirely—and almost certainly too much—on that film to support those findings. In the context of even just one more film, though, the analysis is suddenly more likely to arrive at one of the best features of any comparative approach: both films will be more richly experienced than they would have been in isolation, and the themes or questions in terms of which they're being explored (here the general question of the influence of the Iranian New Wave) will arrive at conclusions that are less at-risk of oversimplification.

For scholars working in comparative fields or through comparative approaches, these features of comparative analysis animate their work. To borrow from a stock example in Western epistemology, our concept of "green" isn't based on a single encounter with something we intuit or are told is "green." Not at all. Our concept of "green" is derived from a complex set of experiences of what others say is green or what's labeled green or what seems to be something that's neither blue nor yellow but kind of both, etc. Comparative analysis essays offer us the chance to engage with that process—even if only enough to help us see where a more in-depth exploration with a higher and/or more diverse "n" might lead—and in that sense, from the standpoint of the subject matter students are exploring through writing as well the complexity of the genre of writing they're using to explore it—comparative analysis forms a bridge of sorts between single-source analysis and research essays.

Typical learning objectives for single-sources essays: formulate analytical questions and an arguable thesis, establish stakes of an argument, summarize sources accurately, choose evidence effectively, analyze evidence effectively, define key terms, organize argument logically, acknowledge and respond to counterargument, cite sources properly, and present ideas in clear prose.

Common types of comparative analysis essays and related types: two works in the same genre, two works from the same period (but in different places or in different cultures), a work adapted into a different genre or medium, two theories treating the same topic; a theory and a case study or other object, etc.

How to Teach It: Framing + Practice

Framing multi-source writing assignments (comparative analysis, research essays, multi-modal projects) is likely to overlap a great deal with "Why It's Useful" (see above), because the range of reasons why we might use these kinds of writing in academic or non-academic settings is itself the reason why they so often appear later in courses. In many courses, they're the best vehicles for exploring the complex questions that arise once we've been introduced to the course's main themes, core content, leading protagonists, and central debates.

For comparative analysis in particular, it's helpful to frame assignment's process and how it will help students successfully navigate the challenges and pitfalls presented by the genre. Ideally, this will mean students have time to identify what each text seems to be doing, take note of apparent points of connection between different texts, and start to imagine how those points of connection (or the absence thereof)

- complicates or upends their own expectations or assumptions about the texts

- complicates or refutes the expectations or assumptions about the texts presented by a scholar

- confirms and/or nuances expectations and assumptions they themselves hold or scholars have presented

- presents entirely unforeseen ways of understanding the texts

—and all with implications for the texts themselves or for the axes along which the comparative analysis took place. If students know that this is where their ideas will be heading, they'll be ready to develop those ideas and engage with the challenges that comparative analysis presents in terms of structure (See "Tips" and "Common Pitfalls" below for more on these elements of framing).

Like single-source analyses, comparative essays have several moving parts, and giving students practice here means adapting the sample sequence laid out at the " Formative Writing Assignments " page. Three areas that have already been mentioned above are worth noting:

- Gathering evidence : Depending on what your assignment is asking students to compare (or in terms of what), students will benefit greatly from structured opportunities to create inventories or data sets of the motifs, examples, trajectories, etc., shared (or not shared) by the texts they'll be comparing. See the sample exercises below for a basic example of what this might look like.

- Why it Matters: Moving beyond "x is like y but also different" or even "x is more like y than we might think at first" is what moves an essay from being "compare/contrast" to being a comparative analysis . It's also a move that can be hard to make and that will often evolve over the course of an assignment. A great way to get feedback from students about where they're at on this front? Ask them to start considering early on why their argument "matters" to different kinds of imagined audiences (while they're just gathering evidence) and again as they develop their thesis and again as they're drafting their essays. ( Cover letters , for example, are a great place to ask writers to imagine how a reader might be affected by reading an their argument.)

- Structure: Having two texts on stage at the same time can suddenly feel a lot more complicated for any writer who's used to having just one at a time. Giving students a sense of what the most common patterns (AAA / BBB, ABABAB, etc.) are likely to be can help them imagine, even if provisionally, how their argument might unfold over a series of pages. See "Tips" and "Common Pitfalls" below for more information on this front.

Sample Exercises and Links to Other Resources

- Common Pitfalls

- Advice on Timing

- Try to keep students from thinking of a proposed thesis as a commitment. Instead, help them see it as more of a hypothesis that has emerged out of readings and discussion and analytical questions and that they'll now test through an experiment, namely, writing their essay. When students see writing as part of the process of inquiry—rather than just the result—and when that process is committed to acknowledging and adapting itself to evidence, it makes writing assignments more scientific, more ethical, and more authentic.

- Have students create an inventory of touch points between the two texts early in the process.

- Ask students to make the case—early on and at points throughout the process—for the significance of the claim they're making about the relationship between the texts they're comparing.

- For coordinate kinds of comparative analysis, a common pitfall is tied to thesis and evidence. Basically, it's a thesis that tells the reader that there are "similarities and differences" between two texts, without telling the reader why it matters that these two texts have or don't have these particular features in common. This kind of thesis is stuck at the level of description or positivism, and it's not uncommon when a writer is grappling with the complexity that can in fact accompany the "taking inventory" stage of comparative analysis. The solution is to make the "taking inventory" stage part of the process of the assignment. When this stage comes before students have formulated a thesis, that formulation is then able to emerge out of a comparative data set, rather than the data set emerging in terms of their thesis (which can lead to confirmation bias, or frequency illusion, or—just for the sake of streamlining the process of gathering evidence—cherry picking).

- For subordinate kinds of comparative analysis , a common pitfall is tied to how much weight is given to each source. Having students apply a theory (in a "lens" essay) or weigh the pros and cons of a theory against case studies (in a "test a theory") essay can be a great way to help them explore the assumptions, implications, and real-world usefulness of theoretical approaches. The pitfall of these approaches is that they can quickly lead to the same biases we saw here above. Making sure that students know they should engage with counterevidence and counterargument, and that "lens" / "test a theory" approaches often balance each other out in any real-world application of theory is a good way to get out in front of this pitfall.

- For any kind of comparative analysis, a common pitfall is structure. Every comparative analysis asks writers to move back and forth between texts, and that can pose a number of challenges, including: what pattern the back and forth should follow and how to use transitions and other signposting to make sure readers can follow the overarching argument as the back and forth is taking place. Here's some advice from an experienced writing instructor to students about how to think about these considerations:

a quick note on STRUCTURE

Most of us have encountered the question of whether to adopt what we might term the “A→A→A→B→B→B” structure or the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure. Do we make all of our points about text A before moving on to text B? Or do we go back and forth between A and B as the essay proceeds? As always, the answers to our questions about structure depend on our goals in the essay as a whole. In a “similarities in spite of differences” essay, for instance, readers will need to encounter the differences between A and B before we offer them the similarities (A d →B d →A s →B s ). If, rather than subordinating differences to similarities you are subordinating text A to text B (using A as a point of comparison that reveals B’s originality, say), you may be well served by the “A→A→A→B→B→B” structure.

Ultimately, you need to ask yourself how many “A→B” moves you have in you. Is each one identical? If so, you may wish to make the transition from A to B only once (“A→A→A→B→B→B”), because if each “A→B” move is identical, the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure will appear to involve nothing more than directionless oscillation and repetition. If each is increasingly complex, however—if each AB pair yields a new and progressively more complex idea about your subject—you may be well served by the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure, because in this case it will be visible to readers as a progressively developing argument.

As we discussed in "Advice on Timing" at the page on single-source analysis, that timeline itself roughly follows the "Sample Sequence of Formative Assignments for a 'Typical' Essay" outlined under " Formative Writing Assignments, " and it spans about 5–6 steps or 2–4 weeks.

Comparative analysis assignments have a lot of the same DNA as single-source essays, but they potentially bring more reading into play and ask students to engage in more complicated acts of analysis and synthesis during the drafting stages. With that in mind, closer to 4 weeks is probably a good baseline for many single-source analysis assignments. For sections that meet once per week, the timeline will either probably need to expand—ideally—a little past the 4-week side of things, or some of the steps will need to be combined or done asynchronously.

What It Can Build Up To

Comparative analyses can build up to other kinds of writing in a number of ways. For example:

- They can build toward other kinds of comparative analysis, e.g., student can be asked to choose an additional source to complicate their conclusions from a previous analysis, or they can be asked to revisit an analysis using a different axis of comparison, such as race instead of class. (These approaches are akin to moving from a coordinate or subordinate analysis to more of a hybrid approach.)

- They can scaffold up to research essays, which in many instances are an extension of a "hybrid comparative analysis."

- Like single-source analysis, in a course where students will take a "deep dive" into a source or topic for their capstone, they can allow students to "try on" a theoretical approach or genre or time period to see if it's indeed something they want to research more fully.

- DIY Guides for Analytical Writing Assignments

- Types of Assignments

- Unpacking the Elements of Writing Prompts

- Formative Writing Assignments

- Single-Source Analysis

- Research Essays

- Multi-Modal or Creative Projects

- Giving Feedback to Students

Assignment Decoder

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Clin Oncol

Methods in Comparative Effectiveness Research

Katrina armstrong.

From the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Comparative effectiveness research (CER) seeks to assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers to make informed decisions to improve health care at both the individual and population levels. CER includes evidence generation and evidence synthesis. Randomized controlled trials are central to CER because of the lack of selection bias, with the recent development of adaptive and pragmatic trials increasing their relevance to real-world decision making. Observational studies comprise a growing proportion of CER because of their efficiency, generalizability to clinical practice, and ability to examine differences in effectiveness across patient subgroups. Concerns about selection bias in observational studies can be mitigated by measuring potential confounders and analytic approaches, including multivariable regression, propensity score analysis, and instrumental variable analysis. Evidence synthesis methods include systematic reviews and decision models. Systematic reviews are a major component of evidence-based medicine and can be adapted to CER by broadening the types of studies included and examining the full range of benefits and harms of alternative interventions. Decision models are particularly suited to CER, because they make quantitative estimates of expected outcomes based on data from a range of sources. These estimates can be tailored to patient characteristics and can include economic outcomes to assess cost effectiveness. The choice of method for CER is driven by the relative weight placed on concerns about selection bias and generalizability, as well as pragmatic concerns related to data availability and timing. Value of information methods can identify priority areas for investigation and inform research methods.

INTRODUCTION

The desire to determine the best treatment for a patient is as old as the medical field itself. However, the methods used to make this determination have changed substantially over time, progressing from the humoral model of disease through the Oslerian application of clinical observation to the paradigm of experimental, evidence-based medicine of the last 40 years. Most recently, the field of comparative effectiveness research (CER) has taken center stage 1 in this arena, driven, at least in part, by the belief that better information about which treatment a patient should receive is part of the answer to addressing the unsustainable growth in health care costs in the United States. 2 , 3

The emergence of CER has galvanized a re-examination of clinical effectiveness research methods, both among researchers and policy organizations. New definitions have been created that emphasize the necessity of answering real-world questions, where patients and their clinicians have to pick from a range of possible options, recognizing that the best choice may vary across patients, settings, and even time periods. 4 The long-standing emphasis on double-blinded, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is increasingly seen as impractical and irrelevant to many of the questions facing clinicians and policy makers today. The importance of generating information that will “assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers to make informed decisions” 1 (p29) is certainly not a new tenet of clinical effectiveness research, but its primacy in CER definitions has important implications for research methods in this area.

CER encompasses both evidence generation and evidence synthesis. 5 Generation of comparative effectiveness evidence uses experimental and observational methods. Synthesis of evidence uses systematic reviews and decision and cost-effectiveness modeling. Across these methods, CER examines a broad range of interventions to “prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care.” 1 (p29)

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

RCTs became the gold standard for clinical effectiveness research soon after publication of the first RCT in 1948. 6 An RCT compares outcomes across groups of participants who are randomly assigned to different interventions, often including a placebo or control arm ( Fig 1 ). RCTs are widely revered for their ability to address selection bias, the correlation between the type of intervention received and other factors associated with the outcome of interest. RCTs are fundamental to the evaluation of new therapeutic agents that are not available outside of a trial setting, and phase III RCT evidence is required for US Food and Drug Administration approval. RCTs are also important for evaluating new technology, including imaging and devices. Increasingly, RCTs are also used to shed light on biology through correlative mechanistic studies, particularly in oncology.

Experimental and observational study designs. In a randomized controlled trial, a population of interest is screened for eligibility, randomly assigned to alternative interventions, and observed for outcomes of interest. In an observational study, the population of interest is assigned to alternative interventions based on patient, provider, and system factors and observed for outcomes of interest.

However, traditional approaches to RCTs are increasingly seen as impractical and irrelevant to many of the questions facing clinicians and policy makers today. RCTs have long been recognized as having important limitations in real-world decision making, 7 including: one, RCTs often have restrictive enrollment criteria so that the participants do not resemble patients in practice, particularly in clinical characteristics such as comorbidity, age, and medications or in sociodemographic characteristics such as race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status; two, RCTs are often not feasible, either because of expense, ethical concerns, or patient acceptance; and three, given their expense and enrollment restrictions, RCTs are rarely able to answer questions about how the effect of the intervention may vary across patients or settings.

Despite these limitations, there is little doubt that RCTs will be a major component of CER. 8 Furthermore, their role is likely to grow with new approaches that increase their relevance in clinical practice. 9 Adaptive trials use accumulating evidence from the trials to modify trial design of the trial to increase efficiency and the probability that trial participants benefit from participation. 10 These adaptations can include changing the end of the trial, changing the interventions or intervention doses, changing the accrual rate, or changing the probability of being randomly assigned to the different arms. One example of an adaptive clinical trial in oncology is the multiarm I-Spy2 trial, which is evaluating multiple agents for neoadjuvant breast cancer treatment. 11 The I-Spy2 trial uses an adaptive approach to assigning patients to treatment arms (where patients with a tumor profile are more likely to be assigned to the arm with the best outcomes for that profile), and data safety monitoring board decisions are guided by Bayesian predicted probabilities of pathologic complete response. 12 , 13 Other examples of adaptive clinical trials in oncology include a randomized trial of four regiments in metastatic prostate cancer, where patients who did not respond to their initial regimen (selected based on randomization) were then randomly assigned to the remaining three regimens, 14 and the CALGB (Cancer and Leukemia Group B) 49907 trial, which used Bayesian predictive probabilities of inferiority to determine the final sample size needed for the comparison of capecitabine and standard chemotherapy in elderly women with early-stage breast cancer. 15 Pragmatic trials relax some of the traditional rules of RCTs to maximize the relevance of the results for clinicians and policy makers. These changes may include expansion of eligibility criteria, flexibility in the application of the intervention and in the management of the control group, and reduction in the intensity of follow-up or procedures for assessing outcomes. 16

OBSERVATIONAL METHODS

The emergence of comparative effectiveness has led to a renewed interest in the role of observational studies for assessing the benefits and harms of alternative interventions. Observational studies compare outcomes between patients who receive different interventions through some process other than investigator randomization. Most commonly, this process is the natural variation in clinical care, although observational studies also can take advantage of natural experiments, where higher-level changes in care delivery (eg, changes in state policy or changes in hospital unit structure) lead to changes in intervention exposure between groups. Observational studies can enroll patients by exposure (eg, type of intervention) using a cohort design or outcome using a case-control design. Cohort studies can be performed prospectively, where participants are recruited at the time of exposure, or retrospectively, where the exposure occurred before participants are identified.

The strengths and limitations of observational studies for clinical effectiveness research have been debated for decades. 7 , 17 Because the incremental cost of including an additional participant is generally low, observational studies often have relatively large numbers of participants who are more representative of the general population. Large, diverse study populations make the results more generalizable to real-world practice and enable the examination of variation in effect across patient subgroups. This advantage is particularly important for understanding effectiveness among vulnerable populations, such as racial minorities, who are often underrepresented in RCT participants. Observational studies that take advantage of existing data sets are able to provide results quickly and efficiently, a critical need for most CER. Currently, observational data already play an important role in influencing guidelines in many areas of oncology, particularly around prevention (eg, nutritional guidelines, management of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers) 18 , 19 and the use of diagnostic tests (eg, use of gene expression profiling in women with node-negative, estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer). 20 However, observational studies also have important limitations. Observational studies are only feasible if the intervention of interest is already being used in clinical practice; they are not possible for evaluation of new drugs or devices. Observational studies are subject to bias, including performance bias, detection bias, and selection bias. 17 , 21 Performance bias occurs when the delivery of one type of intervention is associated with generally higher levels of performance by the health care unit (ie, health care quality) than the delivery of a different type of intervention, making it difficult to determine if better outcomes are the result of the intervention or the accompanying higher-quality health care. Detection bias occurs when the outcomes of interest are more easily detected in one group than another, generally because of differential contact with the health care system between groups. Selection bias is the most important concern in the validity of observational studies and occurs when intervention groups differ in characteristics that are associated with the outcome of interest. These differences can occur because a characteristic is part of the decision about which treatment to recommend (ie, disease severity), which is often termed confounding by indication, or because it is correlated with both intervention and outcome for another reason. A particular concern for CER of therapies is that some new agents may be more likely to be used in patients for whom established therapies have failed and who are less likely to be responsive to any therapy.

There are two main approaches for addressing bias in observational studies. First, important potential confounders must be identified and included in the data collection. Measured confounders can be addressed through multivariate and propensity score analysis. A telling example of the importance of adequate assessment of potential confounders was found through examination of the observational studies of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and coronary heart disease (CHD). Meta-analyses of observational studies had long estimated a substantial reduction in CHD risk with the use of postmenopausal HRT. However, the WHI (Women's Health Initiative) trial, a large, double-blind RCT of postmenopausal HRT, found no difference in CHD risk between women assigned to HRT or placebo. Although this apparent contradiction is often used as general evidence against the validity of observational studies, a re-examination of the observational studies demonstrated that studies that adjusted for measures of socioeconomic status (a clear confounder between HRT use and better health outcomes) had results similar to those of the WHI, whereas studies that did not adjust for socioeconomic status found a protective effect with HRT 22 ( Fig 2 ). The use of administrative data sets for observational studies of comparative effectiveness is likely to become increasingly common as health information technology spreads, and data become more accessible; however, these data sets may be particularly limiting in their ability to include data on potential confounders. In some cases, the characteristics that influence the treatment decision may not be available in the data (eg, performance status, tumor gene expression), making concerns about confounding by indication too high to proceed without adjusting data collection or considering a different question.

Meta-analysis of observational studies of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and coronary artery disease incidence comparing studies that did and did not adjust for socioeconomic status (SES). Data adapted. 22

Second, several analytic approaches can be used to address differences between groups in observational studies. The standard analytic approach involves the use of multivariable adjustment through regression models. Regression allows the estimation of the change in the outcome of interest from the difference in intervention, holding the other variables in the model (covariates) constant. Although regression remains the standard approach to analysis of observational data, regression can be misleading if there is insufficient overlap in the covariates between groups or if the functional forms of the variables are incorrectly specified. 23 Furthermore, the number of covariates that can be included is limited by the number of participants with the outcome of interest in the data set.

Propensity score analysis is another approach to the estimation of an intervention effect in observational data that enables the inclusion of a large number of covariates and a transparent assessment of the balance of covariates after adjustment. 23 – 26 Propensity score analysis uses a two-step process, first estimating the probability of receiving a particular intervention based on the observed covariates (the propensity score) and estimating the effect of the intervention within groups of patients who had a similar probability of receiving the intervention (often grouped as quintiles of propensity score). The degree to which the propensity score is able to represent the differences in covariates between intervention groups is assessed by examining the balance in covariates across propensity score categories. In an ideal situation, after participants are grouped by their propensity for being treated, those who receive different interventions have similar clinical and sociodemographic characteristics—at least for the characteristics that are measured ( Table 1 ). Rates of the outcomes of interest are then compared between intervention groups within each propensity score category, paying attention to whether the intervention effect differs across patients with a different propensity for receiving the intervention. In addition, the propensity score itself can be included in a regression model estimating the effect of the intervention on the outcome, a method that also allows for additional adjustment for covariates that were not sufficiently balanced across intervention groups within propensity score categories.

Hypothetic Example of Propensity Score Analysis Comparing Two Intervention Groups, A and B

| Characteristic | Overall Sample | Quintiles of Propensity Score | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||||

| A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | |

| Mean age, years | 45.3 | 56.9 | 58.9 | 59.0 | 56.2 | 56.1 | 50.4 | 50.4 | 46.9 | 46.7 | 43.0 | 43.2 |

| No. of comorbidities | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 54.0 | 26.5 | 60.8 | 60.4 | 51.7 | 51.8 | 43.6 | 43.4 | 38.9 | 39 | 24.3 | 24.5 |

| 1-2 | 34.7 | 28.8 | 36.8 | 36.9 | 34.4 | 34.4 | 32 | 32.1 | 29.7 | 29.5 | 26.4 | 26.5 |

| > 3 | 11.3 | 44.7 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 13.9 | 13.8 | 24.4 | 24.5 | 31.4 | 31.5 | 49.3 | 49 |

The use of propensity scores for oncology clinical effectiveness research has become increasingly popular over the last decade, with six articles published in Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2011 alone. 27 – 32 However, propensity score analysis has limitations, the most important of which is that it can only include the variables that are in the available data. If a factor that influences the intervention assignment is not included or measured accurately in the data, it cannot be adequately addressed by a propensity score. For example, in a prior propensity score analysis of the association between active treatment and prostate cancer mortality among elderly men, we were able to include only the variables available in Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare linked data in our propensity score. 33 The data included some of the factors that influence treatment decisions (eg, age, comorbidities, tumor grade, and size) but not others (eg, functional status, prostate-specific antigen score). Furthermore, the measurement of some of the available factors was imperfect—for example, assessment of comorbidities was based on billing codes, which can underestimate actual comorbidity burden and provide no information about the severity of the comorbidity. Thus, although the final result demonstrating a fairly strong association between active treatment and reduced mortality was quite robust based on the data that were available, it is still possible that the association represents unaddressed selection factors where healthier men underwent active treatment. 34

Instrumental variable methods are a third analytic approach that estimate the effect of an intervention in observational data without requiring the factors that differ between the intervention groups to be available in the data, thereby addressing both measured and unmeasured confounders. 35 The goal underlying instrumental variable analysis is to identify a characteristic (called the instrument) that strongly influences the assignment of patients to intervention but is not associated with the outcomes of interest (except through the intervention). In essence, an instrumental variable approach is an attempt to replicate an RCT, where the instrument is randomization. 36 Common instruments include the patterns of treatment across geographic areas or health care providers, the distance to a health care facility able to provide the intervention of interest, or structural characteristics of the health care system that influence what interventions are used, such as the density of certain types of providers or facilities. The analysis involves two stages: first, the probability of receiving the intervention of interest is estimated as a function of the instrument variable and other covariates; second, a model is built predicting the outcome of interest based on the instrument-based intervention probability and the residual from the first model.

Instrumental variable analysis is commonly used in economics 37 and has increasingly been applied to health and health care. In oncology, instrumental variable approaches have been used to examine the effectiveness of treatments for lung, prostate, bladder, and breast cancers, with the most common instruments being area-level treatment patterns. 38 – 42 One recent analysis of prostate cancer treatment found that multivariable regression and propensity score methods resulted in essentially the same estimate of effect for radical prostatectomy, but an instrumental variable based on the treatment pattern of the previous year found no benefit from radical prostatectomy, similar to the estimate from a recently published trial. 41 , 43 However, concerns also exist about the validity of instrumental variable results, particularly if the instrument is not strongly associated with the intervention, or if there are other potential pathways by which the instrument may influence the outcome. Although the strength of the association between the instrument and the intervention assignment can be tested in the analysis, alternative pathways by which the instrument may be associated with the outcome are often not identified until after publication. A recent instrumental variable analysis used annual rainfall as the instrument to demonstrate an association between television watching and autism, arguing that annual rainfall is associated with the amount of time children watch television but is not otherwise associated with the risk of autism. 44 The findings generated considerable controversy after publication, with the identification of several other potential links between rainfall and autism. 45 Instrumental variable methods have traditionally been unable to examine differences in effect between patient subgroups, but new approaches may improve their utility in this important component of CER. 46 , 47

SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

For some decisions faced by clinicians and policy makers, there is insufficient evidence to inform decision making, and new studies to generate evidence are needed. However, for other decisions, evidence exists but is sufficiently complex or controversial that it must be synthesized to inform decision making. Systematic reviews are an important form of evidence synthesis that brings together the available evidence using an organized and evaluative approach. 48 Systematic reviews are frequently used for guideline development and generally include four major steps. 49 First, the clinical decision is identified, and the analytic framework and key questions are determined. Sometimes the decision may be straightforward and involve a single key question (eg, Does drug A reduce the incidence of disease B?), but other times the question may be more complicated (eg, Should gene expression profiling be used in early-stage breast cancer?) and involve multiple key questions. 50 Second, the literature is searched to identify the relevant studies using inclusion and exclusion criteria that may include the timing of the study, the study design, and the location of the study. Third, the identified studies are graded on quality using established criteria such as the CONSORT criteria for RCTs 51 and the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) criteria for observational studies. 52 Studies that do not meet a minimum quality threshold may be excluded because of concern about the validity of the results. Fourth, the results of all the studies are collated in evidence tables, often including key characteristics of the study design or population that might influence the results. Meta-analytic techniques may be used to combine results across studies when there is sufficient homogeneity to make a single-point estimate statistically valid. Alternatively, models may be used to identify the study or population factors that are associated with different results.

Although systematic reviews are a key component of evidence-based medicine, their role in CER is still uncertain. The traditional approach to systematic reviews has often excluded observational studies because of concerns about internal validity, but such exclusions may greatly limit the evidence available for many important comparative effectiveness questions. CER is designed to inform real-world decisions between available alternatives, which may include multiple tradeoffs. Inclusion of information about harms in comparative effectiveness systematic reviews is desirable but often challenging because of limited data. Finally, systematic reviews are rarely able to examine differences in intervention effects across patient characteristics, another important step for achieving the goals of CER.

DECISION AND COST-EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS

Another evidence synthesis method that is gaining increasing traction in CER is decision modeling. Decision modeling is a quantitative approach to evidence synthesis that brings together data from a range of sources to estimate expected outcomes of different interventions. 53 The first step in a decision model is to lay out the structure of the decision, including the alternative choices and the clinical and economic outcomes of those alternatives. 54 Ensuring that the structure of the model holds true to the clinical scenario of interest without becoming overwhelmed by minor possible variations is critical for the eventual impact of the model. 55 Once the decision structure is determined, a decision tree or simulation model is created that incorporates the probabilities of different outcomes over time and the change in those probabilities from the use of different interventions. 56 , 57 To calculate the expected outcomes, a hypothetic cohort of patients is run through each of the decision alternatives in the model. Estimated outcomes are generally assessed as a count of events in the cohort (eg, deaths, cancers) or as the mean or median life expectancy among the cohort. 58

Decision models can also include information about the value placed on each of the outcomes (often referred to as utility) as well as the health care costs incurred by the interventions and the health outcomes. A decision model that includes cost and utility is often referred to as a cost-benefit or cost-effectiveness model and is used in some settings to compare value across interventions. The types of costs that are included depend on the perspective of the model, with a model from the societal perspective including both direct and indirect medical costs (eg, loss of productivity), a model from a payer (ie, insurer) perspective including only direct medical costs, and a model from a patient perspective including the costs experienced by the patient. Future costs are discounted to address the change in monetary value over time. 59 Sensitivity analyses are used to explore the impact of different assumptions on the model results, a critical step for understanding how the results should be used in clinical and policy decisions and for the development of future evidence-generation research. These sensitivity analyses often use a probabilistic approach, where a distribution is entered for each of the inputs and the computer samples from those distributions across a large number of simulations, thereby creating a confidence interval around the estimated outcomes of the alternative choices.

Decision models have several strengths in CER. They can link multiple sources of information to estimate the effect of different interventions on health outcomes, even when there are no studies that directly assess the effect of interest. Because they can examine the effect of variation in different probability estimates, they are particularly useful for understanding how patient characteristics will affect the expected outcomes of different interventions. Decision models can also estimate the impact of an intervention across a population, including the effect on economic outcomes. Decision and cost-effectiveness analyses have been used frequently in oncology, particularly for decisions with options that include the use of a diagnostic or screening test (eg, bone mineral density testing for management of osteoporosis risk), 60 involve significant tradeoffs (eg, adjuvant chemotherapy), 61 or have only limited empirical evidence (eg, management strategies in BRCA mutation carriers). 62

However, decision models also have several limitations that have limited their impact on clinical and policy decision making in the United States to date and are likely to constrain their role in future CER. Often, model results are highly sensitive to the assumptions of the model, and removing bias from these assumptions is difficult. The potential impact of conflicts of interest is high. Decision models require data inputs. For many decisions, data are insufficient for key inputs, requiring the use of educated guesses (ie, expert opinion). The measurement of utility has proven particularly challenging and can lead to counterintuitive results. In the end, decision analysis is similar to other comparative effectiveness methods—useful for the right question as long as results are interpreted with an understanding of the methodologic limitations.

SELECTION OF CER METHODS

The choice of method for a comparative effectiveness study involves the consideration of multiple factors. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Methods Committee has identified five intrinsic and three extrinsic factors ( Table 2 ), including internal validity, generalizability, and variation across patient subgroups as well as the feasibility and time urgency. 63 The importance of these factors will vary across the questions being considered. For some questions, the concern about selection bias will be too great for observational studies, particularly if a strong instrument cannot be identified. Many questions about aggressive versus less aggressive treatments may fall into this category, because the decision is often correlated with patient characteristics that predict survival but are rarely found in observational data sets (eg, functional status, social support). For other questions, concern about selection bias will be less pressing than the need for rapid and efficient results. This scenario may be particularly relevant for the comparison of existing therapies that differ in cost or adverse outcomes, where the use of the therapy is largely driven by practice style. In many cases, the choice will be pragmatic based on what data are available and the feasibility of conducting an RCT. These choices will increasingly be informed by the value of information methods 64 – 66 that use economic modeling to provide guidance about where and how investment in CER should be made.

Factors That Influence Selection of Study Design for Patient-Centered Outcome Research

| Factor |

|---|

In reality, the questions of CER are not new but are simply more important than ever. Nearly 50 years ago, Sir Austin Bradford Hill spoke about the importance of a broad portfolio of methods in clinical research, saying “To-day … there are many drugs that work and work potently. We want to know whether this one is more potent than that, what dose is right and proper, for what kind of patient.” 7 (p109) This call has expanded beyond drugs to become the charge for CER. To fulfill this charge, investigators will need to use a range of methods, extending the experience in effectiveness research of the last decades “to assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers to make informed decisions that will improve health care at both the individual and population levels.” 1 (p29)

Supported by Award No. UC2CA148310 from the National Cancer Institute.

The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Author's disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHOR'S DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Comparative Case Studies: Methodological Discussion

- Open Access

- First Online: 25 May 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Marcelo Parreira do Amaral 7

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Adult Education and Lifelong Learning ((PSAELL))

14k Accesses

7 Citations

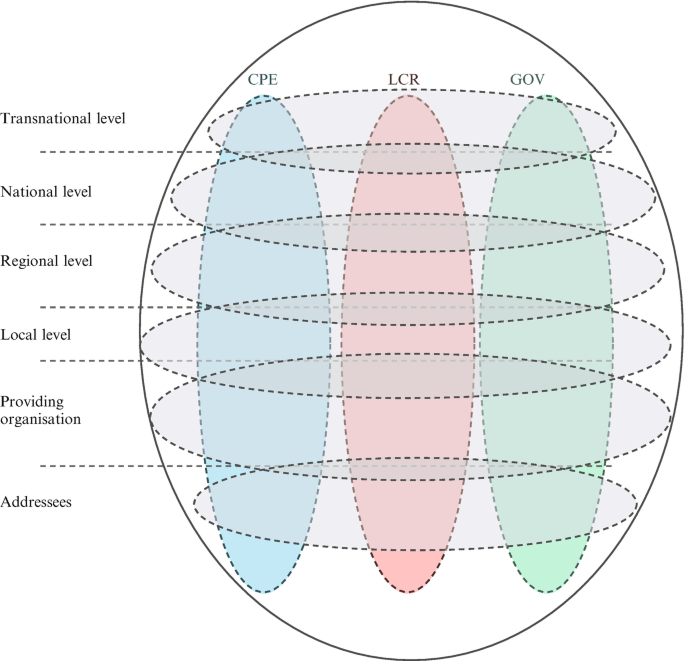

Case Study Research has a long tradition and it has been used in different areas of social sciences to approach research questions that command context sensitiveness and attention to complexity while tapping on multiple sources. Comparative Case Studies have been suggested as providing effective tools to understanding policy and practice along three different axes of social scientific research, namely horizontal (spaces), vertical (scales), and transversal (time). The chapter, first, sketches the methodological basis of case-based research in comparative studies as a point of departure, also highlighting the requirements for comparative research. Second, the chapter focuses on presenting and discussing recent developments in scholarship to provide insights on how comparative researchers, especially those investigating educational policy and practice in the context of globalization and internationalization, have suggested some critical rethinking of case study research to account more effectively for recent conceptual shifts in the social sciences related to culture, context, space and comparison. In a third section, it presents the approach to comparative case studies adopted in the European research project YOUNG_ADULLLT that has set out to research lifelong learning policies in their embeddedness in regional economies, labour markets and individual life projects of young adults. The chapter is rounded out with some summarizing and concluding remarks.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction to the Book and the Comparative Study

Theoretical and Methodological Considerations

Main findings and discussion.

- Case-based research

- Comparative case studies

1 Introduction

Exploring landscapes of lifelong learning in Europe is a daunting task as it involves a great deal of differences across places and spaces; it entails attending to different levels and dimensions of the phenomena at hand, but not least it commands substantial sensibility to cultural and contextual idiosyncrasies. As such, case-based methodologies come to mind as tested methodological approaches to capturing and examining singular configurations such as the local settings in focus in this volume, in which lifelong learning policies for young people are explored in their multidimensional reality. The ensuing question, then, is how to ensure comparability across cases when departing from the assumption that cases are unique. Recent debates in Comparative and International Education (CIE) research are drawn from that offer important insights into the issues involved and provide a heuristic approach to comparative cases studies. Since the cases focused on in the chapters of this book all stem from a common European research project, the comparative case study methodology allows us to at once dive into the specifics and uniqueness of each case while at the same time pay attention to common treads at the national and international (European) levels.

The chapter, first, sketches the methodological basis of case-based research in comparative studies as a point of departure, also highlighting the requirements in comparative research. In what follows, second, the chapter focuses on presenting and discussing recent developments in scholarship to provide insights on how comparative researchers, especially those investigating educational policy and practice in the context of globalization and internationalization, have suggested some critical rethinking of case study research to account more effectively for recent conceptual shifts in the social sciences related to culture, context, space and comparison. In a third section, it presents the approach to comparative case studies adopted in the European research project YOUNG_ADULLLT that has set out to research lifelong learning policies in their embeddedness in regional economies, labour markets and individual life projects of young adults. The chapter is rounded out with some summarizing and concluding remarks.

2 Case-Based Research in Comparative Studies

In the past, comparativists have oftentimes regarded case study research as an alternative to comparative studies proper. At the risk of oversimplification: methodological choices in comparative and international education (CIE) research, from the 1960s onwards, have fallen primarily on either single country (small n) contextualized comparison, or on cross-national (usually large n, variable) decontextualized comparison (see Steiner-Khamsi, 2006a , 2006b , 2009). These two strands of research—notably characterized by Development and Area Studies on the one side and large-scale performance surveys of the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) type, on the other—demarcated their fields by resorting to how context and culture were accounted for and dealt with in the studies they produced. Since the turn of the century, though, comparativists are more comfortable with case study methodology (see Little, 2000 ; Vavrus and Bartlett 2006 , 2009 ; Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 ) and diagnoses of an “identity crisis” of the field due to a mass of single-country studies lacking comparison proper (see Schriewer, 1990 ; Wiseman & Anderson, 2013 ) started dying away. Greater acceptance of and reliance on case-based methodology has been related with research on policy and practice in the context of globalization and coupled with the intention to better account for culture and context, generating scholarship that is critical of power structures, sensitive to alterity and of other ways of knowing.

The phenomena that have been coined as constituting “globalization” and “internationalization” have played, as mentioned, a central role in the critical rethinking of case study research. In researching education under conditions of globalization, scholars placed increasing attention on case-based approaches as opportunities for investigating the contemporary complexity of policy and practice. Further, scholarly debates in the social sciences and the humanities surrounding key concepts such as culture, context, space, and place but also comparison have also contributed to a reconceptualization of case study methodology in CIE. In terms of the requirements for such an investigation, scholarship commands an adequate conceptualization that problematizes the objects of study and that does not take them as “unproblematic”, “assum[ing] a constant shared meaning”; in short, objects of study that are “fixed, abstract and absolute” (Fine, quoted in Dale & Robertson, 2009 , p. 1114). Case study research is thus required to overcome methodological “isms” in their research conceptualization (see Dale & Robertson, 2009 ; Robertson & Dale, 2017 ; see also Lange & Parreira do Amaral, 2018 ). In response to these requirements, the approaches to case study discussed in CIE depart from a conceptualization of the social world as always dynamic, emergent, somewhat in motion, and always contested. This view considers the fact that the social world is culturally produced and is never complete or at a standstill, which goes against an understanding of case as something fixed or natural. Indeed, in the past cases have often been understood almost in naturalistic ways, as if they existed out there, waiting for researchers to “discover” them. Usually, definitions of case study also referred to inquiry that aims at elucidating features of a phenomenon to yield an understanding of why, how and with what consequences something happens. One can easily find examples of cases understood simply as sites to observe/measure variables—in a nomothetic cast—or examples, where cases are viewed as specific and unique instances that can be examined in the idiographic paradigm. In contrast, rather than taking cases as pre-existing entities that are defined and selected as cases, recent case-oriented research has argued for a more emergent approach which recognizes that boundaries between phenomenon and context are often difficult to establish or overlap. For this reason, researchers are incited to see this as an exercise of “casing”, that is, of case construction. In this sense, cases here are seen as complex systems (Ragin & Becker, 1992 ) and attention is devoted to the relationships between the parts and the whole, pointing to the relevance of configurations and constellations within as well as across cases in the explanation of complex and contingent phenomena. This is particularly relevant for multi-case, comparative research since the constitution of the phenomena that will be defined, as cases will differ. Setting boundaries will thus also require researchers to account for spatial, scalar (i.e., level or levels with which a case is related) and temporal aspects.

Further, case-based research is also required to account for multiple contexts while not taking them for granted. One of the key theoretical and methodological consequences of globalization for CIE is that it required us to recognize that it alters the nature and significance of what counts as contexts (see Parreira do Amaral, 2014 ). According to Dale ( 2015 ), designating a process, or a type of event, or a particular organization, as a context, entails bestowing a particular significance on them, as processes, events, and so on that are capable of affecting other processes and events. The key point is that rather than being so intrinsically, or naturally, contexts are constructed as “contexts”. In comparative research, contexts have been typically seen as the place (or the variables) that enable us to explain why what happens in one case is different from what happens another case; what counts as context then is seen as having the same effect everywhere, although the forms it takes vary substantially (see Dale, 2015 ). In more general terms, recent case study approaches aim at accounting for the increasing complexity of the contexts in which they are embedded, which, in turn, is related to the increasing impact of globalization as the “context of contexts” (Dale, 2015 , p. 181f; see also Carter & Sealey, 2013 ; Mjoset, 2013 ). It also aims at accounting for overlapping contexts. Here it is important to note that contexts are not only to be seen in spatio-geographical terms (i.e., local, regional, national, international), but contexts may also be provided by different institutional and/or discursive contexts that create varying opportunity structures (Dale & Parreira do Amaral, 2015 ; see also Chap. 2 in this volume). What one can call temporal contexts also plays an important role, for what happens in the case unfolds as embedded not only in historical time, but may be related to different temporalities (see the concept of “timespace” as discussed by Lingard & Thompson, 2016 ) and thus are influenced by path dependence or by specific moments of crisis (Rhinard, 2019 ; see also McLeod, 2016 ). Moreover, in CIE research, the social-cultural production of the world is influenced by developments throughout the globe that take place at various places and on several scales, which in turn influence each other, but in the end, become locally relevant in different facets. As Bartlett and Vavrus write, “context is not a primordial or autonomous place; it is constituted by social interactions, political processes, and economic developments across scales and times.” ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 14). Indeed, in this sense, “context is not a container for activity, it is the activity” (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 12, emphasis in orig.).

Also, dealing with the complexity of education policy and practice requires us to transcend the dichotomy of idiographic versus nomothetic approaches to causation. Here, it can be argued that case studies allow us to grasp and research the complexity of the world, thus offering conceptual and methodological tools to explore how phenomena viewed as cases “depend on all of the whole, the parts, the interactions among parts and whole, and the interactions of any system with other complex systems among which it is nested and with which it intersects” (Byrne, 2013 , p. 2). The understanding of causation that undergirds recent developments in case-based research aims at generalization, yet it resists ambitions to establishing universal laws in social scientific research. Focus is placed on processes while tracking the relevant factors, actors and features that help explain the “how” and the “why” questions (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 , p. 38ff), and on “causal mechanisms”, as varying explanations of outcomes within and across cases, always contingent on interaction with other variables and dependent contexts (see Byrne, 2013 ; Ragin, 2000 ). In short, the nature of causation underlying the recent case study approaches in CIE is configurational and not foundational.

This is also in line with how CIE research regards education practice, research, and policy as a socio-cultural practice. And it refers to the production of social and cultural worlds through “social actors, with diverse motives, intentions, and levels of influence, [who] work in tandem with and/or in response to social forces” (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 , p. 1). From this perspective, educational phenomena, such as in policymaking, are seen as a “deeply political process of cultural production engaged in and shaped by social actors in disparate locations who exert incongruent amounts of influence over the design, implementation, and evaluation of policy” ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 1f). Culture here is understood in non-static and complex ways that reinforce the “importance of examining processes of sense-making as they develop over time, in distinct settings, in relation to systems of power and inequality, and in increasingly interconnected conversation with actors who do not sit physically within the circle drawn around the traditional case” (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 11, emphasis in orig.).