- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Early life.

Mature life and works..

- Later life and works.

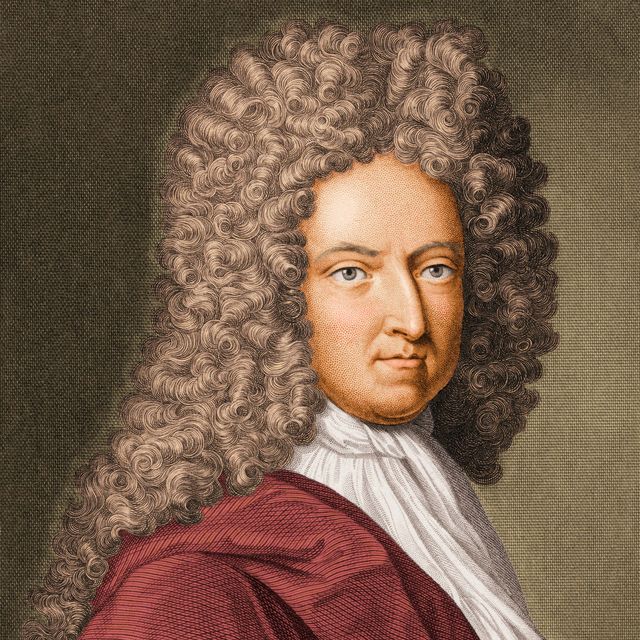

Daniel Defoe

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- The Victorian Web - Biography of Daniel Defoe

- Christian Classics Ethereal Library - Daniel Defoe

- The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction - Daniel Defoe

- Poetry Foundation - Biography of Daniel Defoe

- Official Site of the Daniel Defoe Society

- Michigan State University Libraries - Defoe and the Plague in London 1664-1665

- Luminarium - Life of Daniel Defoe

- Heritage History - Biography of Daniel Defoe

- Daniel Defoe - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

What was Daniel Defoe’s family like?

Daniel Defoe’s father, James Foe, was a Nonconformist , or Dissenter, and a fairly prosperous tallow chandler (perhaps also, later, a butcher) of Flemish descent. By his middle 30s, Daniel was calling himself “Defoe,” probably reviving a variant of what may have been the original family name.

What were Daniel Defoe’s jobs?

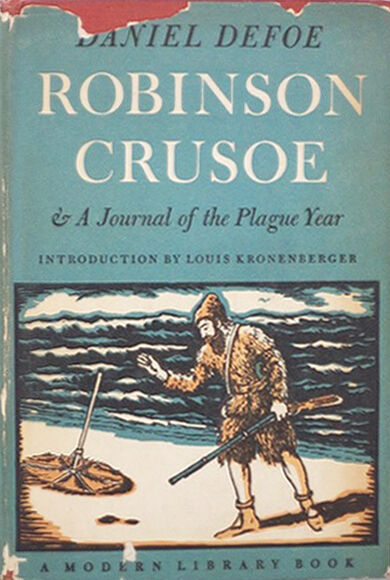

Daniel Defoe began his career as a merchant and trader, dealing in many commodities. He later became a writer, noted for his poems and political pamphlets. Defoe was 59 when he published his first novel, Robinson Crusoe , which brought him lasting fame.

What is Daniel Defoe best known for?

Daniel Defoe is best known as the writer of the novels Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Moll Flanders (1722). During his lifetime he gained fame—and notoriety—for his poems, political pamphlets, and journalism.

Daniel Defoe (born 1660, London , Eng.—died April 24, 1731, London) was an English novelist, pamphleteer, and journalist, known as the author of Robinson Crusoe (1719–22) and Moll Flanders (1722).

Defoe’s father, James Foe , was a hard-working and fairly prosperous tallow chandler (perhaps also, later, a butcher), of Flemish descent. By his middle 30s, Daniel was calling himself “Defoe,” probably reviving a variant of what may have been the original family name . As a Nonconformist , or Dissenter, Foe could not send his son to the University of Oxford or to Cambridge; he sent him instead to the excellent academy at Newington Green kept by the Reverend Charles Morton. There Defoe received an education in many ways better, and certainly broader, than any he would have had at an English university. Morton was an admirable teacher, later becoming first vice president of Harvard College; and the clarity, simplicity, and ease of his style of writing—together with the Bible, the works of John Bunyan , and the pulpit oratory of the day—may have helped to form Defoe’s own literary style.

Although intended for the Presbyterian ministry, Defoe decided against this and by 1683 had set up as a merchant. He called trade his “beloved subject,” and it was one of the abiding interests of his life. He dealt in many commodities, traveled widely at home and abroad, and became an acute and intelligent economic theorist, in many respects ahead of his time; but misfortune, in one form or another, dogged him continually. He wrote of himself:

No man has tasted differing fortunes more, And thirteen times I have been rich and poor.

It was true enough. In 1692, after prospering for a while, Defoe went bankrupt for £17,000. Opinions differ as to the cause of his collapse: on his own admission, Defoe was apt to indulge in rash speculations and projects; he may not always have been completely scrupulous, and he later characterized himself as one of those tradesmen who had “done things which their own principles condemned, which they are not ashamed to blush for.” But undoubtedly the main reason for his bankruptcy was the loss that he sustained in insuring ships during the war with France—he was one of 19 “merchants insurers” ruined in 1692. In this matter Defoe may have been incautious, but he was not dishonourable, and he dealt fairly with his creditors (some of whom pursued him savagely), paying off all but £5,000 within 10 years. He suffered further severe losses in 1703, when his prosperous brick-and-tile works near Tilbury failed during his imprisonment for political offenses, and he did not actively engage in trade after this time.

Soon after setting up in business, in 1684, Defoe married Mary Tuffley, the daughter of a well-to-do Dissenting merchant. Not much is known about her, and he mentions her little in his writings, but she seems to have been a loyal, capable, and devoted wife. She bore eight children, of whom six lived to maturity, and when Defoe died the couple had been married for 47 years.

With Defoe’s interest in trade went an interest in politics. The first of many political pamphlets by him appeared in 1683. When the Roman Catholic James II ascended the throne in 1685, Defoe—as a staunch Dissenter and with characteristic impetuosity—joined the ill-fated rebellion of the Duke of Monmouth , managing to escape after the disastrous Battle of Sedgemoor . Three years later James had fled to France, and Defoe rode to welcome the army of William of Orange —“ William, the Glorious, Great, and Good, and Kind,” as Defoe was to call him. Throughout William III’s reign, Defoe supported him loyally, becoming his leading pamphleteer. In 1701, in reply to attacks on the “foreign” king, Defoe published his vigorous and witty poem The True-Born Englishman, an enormously popular work that is still very readable and relevant in its exposure of the fallacies of racial prejudice . Defoe was clearly proud of this work, because he sometimes designated himself “Author of ‘The True-Born Englishman’” in later works.

Foreign politics also engaged Defoe’s attention. Since the Treaty of Rijswijk (1697), it had become increasingly probable that what would, in effect, be a European war would break out as soon as the childless king of Spain died. In 1701 five gentlemen of Kent presented a petition, demanding greater defense preparations, to the House of Commons (then Tory-controlled) and were illegally imprisoned. Next morning Defoe, “guarded with about 16 gentlemen of quality,” presented the speaker, Robert Harley, with his famous document “ Legion’s Memorial,” which reminded the Commons in outspoken terms that “Englishmen are no more to be slaves to Parliaments than to a King.” It was effective: the Kentishmen were released, and Defoe was feted by the citizens of London. It had been a courageous gesture and one of which Defoe was ever afterward proud, but it undoubtedly branded him in Tory eyes as a dangerous man who must be brought down.

What did bring him down, only a year or so later, and consequently led to a new phase in his career, was a religious question—though it is difficult to separate religion from politics in this period. Both Dissenters and “Low Churchmen” were mainly Whigs , and the “highfliers”—the High-Church Tories—were determined to undermine this working alliance by stopping the practice of “occasional conformity” (by which Dissenters of flexible conscience could qualify for public office by occasionally taking the sacraments according to the established church). Pressure on the Dissenters increased when the Tories came to power, and violent attacks were made on them by such rabble-rousing extremists as Dr. Henry Sacheverell . In reply, Defoe wrote perhaps the most famous and skillful of all his pamphlets, “The Shortest-Way With The Dissenters ” (1702), published anonymously. His method was ironic: to discredit the highfliers by writing as if from their viewpoint but reducing their arguments to absurdity. The pamphlet had a huge sale, but the irony blew up in Defoe’s face: Dissenters and High Churchmen alike took it seriously, and—though for different reasons—were furious when the hoax was exposed. Defoe was prosecuted for seditious libel and was arrested in May 1703. The advertisement offering a reward for his capture gives the only extant personal description of Defoe—an unflattering one, which annoyed him considerably: “a middle-size spare man, about 40 years old, of a brown complexion, and dark-brown coloured hair, but wears a wig, a hooked nose, a sharp chin, grey eyes, and a large mole near his mouth.” Defoe was advised to plead guilty and rely on the court’s mercy, but he received harsh treatment, and, in addition to being fined, was sentenced to stand three times in the pillory. It is likely that the prosecution was primarily political, an attempt to force him into betraying certain Whig leaders; but the attempt was evidently unsuccessful. Although miserably apprehensive of his punishment, Defoe had spirit enough, while awaiting his ordeal, to write the audacious “ Hymn To The Pillory” (1703); and this helped to turn the occasion into something of a triumph, with the pillory garlanded, the mob drinking his health, and the poem on sale in the streets. In An Appeal to Honour and Justice (1715), he gave his own, self-justifying account of these events and of other controversies in his life as a writer.

Triumph or not, Defoe was led back to Newgate, and there he remained while his Tilbury business collapsed and he became ever more desperately concerned for the welfare of his already numerous family. He appealed to Robert Harley , who, after many delays, finally secured his release—Harley’s part of the bargain being to obtain Defoe’s services as a pamphleteer and intelligence agent.

Defoe certainly served his masters with zeal and energy, traveling extensively, writing reports, minutes of advice, and pamphlets. He paid several visits to Scotland, especially at the time of the Act of Union in 1707, keeping Harley closely in touch with public opinion . Some of Defoe’s letters to Harley from this period have survived. These trips bore fruit in a different way two decades later: in 1724–26 the three volumes of Defoe’s animated and informative Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain were published, in preparing which he drew on many of his earlier observations.

Perhaps Defoe’s most remarkable achievement during Queen Anne’s reign, however, was his periodical, the Review . He wrote this serious, forceful, and long-lived paper practically single-handedly from 1704 to 1713. At first a weekly, it became a thrice-weekly publication in 1705, and Defoe continued to produce it even when, for short periods in 1713, his political enemies managed to have him imprisoned again on various pretexts. It was, effectively, the main government organ, its political line corresponding with that of the moderate Tories (though Defoe sometimes took an independent stand); but, in addition to politics as such, Defoe discussed current affairs in general, religion, trade, manners, morals , and so on, and his work undoubtedly had a considerable influence on the development of later essay periodicals (such as Richard Steele and Joseph Addison’s The Tatler and The Spectator ) and of the newspaper press.

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (c. 1660 – 24 April 1731), born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel Robinson Crusoe, which is second only to the Bible in its number of translations. He has been seen as one of the earliest proponents of the English novel, and helped to popularise the form in Britain with others such as Aphra Behn and Samuel Richardson. Defoe wrote many political tracts and often was in trouble with the authorities, including a spell in prison. Intellectuals and political leaders paid attention to his fresh ideas and sometimes consulted with him.

Defoe was a prolific and versatile writer, producing more than three hundred works—books, pamphlets, and journals—on diverse topics, including politics, crime, religion, marriage, psychology, and the supernatural. He was also a pioneer of business journalism and economic journalism.

Daniel Foe (his original name) was probably born in Fore Street in the parish of St Giles Cripplegate, London. Defoe later added the aristocratic-sounding “De” to his name, and on occasion claimed descent from the family of De Beau Faux. His birthdate and birthplace are uncertain, and sources offer dates from 1659 to 1662, with the summer or early autumn of 1660 considered the most likely. His father, James Foe, was a prosperous tallow chandler and a member of the Worshipful Company of Butchers. In Defoe’s early life, he experienced some of the most unusual occurrences in English history: in 1665, 70,000 were killed by the Great Plague of London, and the next year, the Great Fire of London left standing only Defoe’s and two other houses in his neighbourhood. In 1667, when he was probably about seven, a Dutch fleet sailed up the Medway via the River Thames and attacked the town of Chatham in the raid on the Medway. His mother, Annie, had died by the time he was about ten.

Defoe was educated at the Rev. James Fisher’s boarding school in Pixham Lane in Dorking, Surrey. His parents were Presbyterian dissenters, and around the age of 14, he attended a dissenting academy at Newington Green in London run by Charles Morton, and he is believed to have attended the Newington Green Unitarian Church and kept practising his Presbyterian religion. During this period, the English government persecuted those who chose to worship outside the Church of England.

Business career

Defoe entered the world of business as a general merchant, dealing at different times in hosiery, general woollen goods, and wine. His ambitions were great and he was able to buy a country estate and a ship (as well as civets to make perfume), though he was rarely out of debt. He was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1692. On 1 January 1684, Defoe married Mary Tuffley at St Botolph’s Aldgate. She was the daughter of a London merchant, receiving a dowry of £3,700—a huge amount by the standards of the day. With his debts and political difficulties, the marriage may have been troubled, but it lasted 47 years and produced eight children.In 1685, Defoe joined the ill-fated Monmouth Rebellion but gained a pardon, by which he escaped the Bloody Assizes of Judge George Jeffreys. Queen Mary and her husband William III were jointly crowned in 1689, and Defoe became one of William’s close allies and a secret agent. Some of the new policies led to conflict with France, thus damaging prosperous trade relationships for Defoe, who had established himself as a merchant. In 1692, Defoe was arrested for debts of £700, though his total debts may have amounted to £17,000. His laments were loud and he always defended unfortunate debtors, but there is evidence that his financial dealings were not always honest. He died with little wealth and evidence of lawsuits with the royal treasury.Following his release, he probably travelled in Europe and Scotland, and it may have been at this time that he traded wine to Cadiz, Porto and Lisbon. By 1695, he was back in England, now formally using the name “Defoe” and serving as a “commissioner of the glass duty”, responsible for collecting taxes on bottles. In 1696, he ran a tile and brick factory in what is now Tilbury in Essex and lived in the parish of Chadwell St Mary.

As many as 545 titles have been ascribed to Defoe, ranging from satirical poems, political and religious pamphlets, and volumes. (Furbank and Owens argue for the much smaller number of 276 published items in Critical Bibliography (1998).)

Pamphleteering and prison

Defoe’s first notable publication was An essay upon projects, a series of proposals for social and economic improvement, published in 1697. From 1697 to 1698, he defended the right of King William III to a standing army during disarmament, after the Treaty of Ryswick (1697) had ended the Nine Years’ War (1688–1697). His most successful poem, The True-Born Englishman (1701), defended the king against the perceived xenophobia of his enemies, satirising the English claim to racial purity. In 1701, Defoe presented the Legion’s Memorial to Robert Harley, then Speaker of the House of Commons—and his subsequent employer—while flanked by a guard of sixteen gentlemen of quality. It demanded the release of the Kentish petitioners, who had asked Parliament to support the king in an imminent war against France.

The death of William III in 1702 once again created a political upheaval, as the king was replaced by Queen Anne who immediately began her offensive against Nonconformists. Defoe was a natural target, and his pamphleteering and political activities resulted in his arrest and placement in a pillory on 31 July 1703, principally on account of his December 1702 pamphlet entitled The Shortest-Way with the Dissenters; Or, Proposals for the Establishment of the Church, purporting to argue for their extermination. In it, he ruthlessly satirised both the High church Tories and those Dissenters who hypocritically practised so-called “occasional conformity”, such as his Stoke Newington neighbour Sir Thomas Abney. It was published anonymously, but the true authorship was quickly discovered and Defoe was arrested. He was charged with seditious libel. Defoe was found guilty after a trial at the Old Bailey in front of the notoriously sadistic judge Salathiel Lovell. Lovell sentenced him to a punitive fine of 200 marks, to public humiliation in a pillory, and to an indeterminate length of imprisonment which would only end upon the discharge of the punitive fine. According to legend, the publication of his poem Hymn to the Pillory caused his audience at the pillory to throw flowers instead of the customary harmful and noxious objects and to drink to his health. The truth of this story is questioned by most scholars, although John Robert Moore later said that “no man in England but Defoe ever stood in the pillory and later rose to eminence among his fellow men”.

After his three days in the pillory, Defoe went into Newgate Prison. Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, brokered his release in exchange for Defoe’s co-operation as an intelligence agent for the Tories. In exchange for such co-operation with the rival political side, Harley paid some of Defoe’s outstanding debts, improving his financial situation considerably.Within a week of his release from prison, Defoe witnessed the Great Storm of 1703, which raged through the night of 26/27 November. It caused severe damage to London and Bristol, uprooted millions of trees, and killed more than 8,000 people, mostly at sea. The event became the subject of Defoe’s The Storm (1704), which includes a collection of witness accounts of the tempest. Many regard it as one of the world’s first examples of modern journalism.In the same year, he set up his periodical A Review of the Affairs of France which supported the Harley Ministry, chronicling the events of the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1714). The Review ran three times a week without interruption until 1713. Defoe was amazed that a man as gifted as Harley left vital state papers lying in the open, and warned that he was almost inviting an unscrupulous clerk to commit treason; his warnings were fully justified by the William Gregg affair.

When Harley was ousted from the ministry in 1708, Defoe continued writing the Review to support Godolphin, then again to support Harley and the Tories in the Tory ministry of 1710–1714. The Tories fell from power with the death of Queen Anne, but Defoe continued doing intelligence work for the Whig government, writing “Tory” pamphlets that undermined the Tory point of view.Not all of Defoe’s pamphlet writing was political. One pamphlet was originally published anonymously, entitled "A True Relation of the Apparition of One Mrs. Veal the Next Day after her Death to One Mrs. Bargrave at Canterbury the 8th of September, 1705." It deals with interaction between the spiritual realm and the physical realm and was most likely written in support of Charles Drelincourt’s The Christian Defense against the Fears of Death (1651). It describes Mrs. Bargrave’s encounter with her old friend Mrs. Veal after she had died. It is clear from this piece and other writings that the political portion of Defoe’s life was by no means his only focus.

Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707

In despair during his imprisonment for the seditious libel case, Defoe wrote to William Paterson, the London Scot and founder of the Bank of England and part instigator of the Darien scheme, who was in the confidence of Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, leading minister and spymaster in the English Government. Harley accepted Defoe’s services and released him in 1703. He immediately published The Review, which appeared weekly, then three times a week, written mostly by himself. This was the main mouthpiece of the English Government promoting the Act of Union 1707.In 1709, Defoe authored a rather lengthy book entitled The History of the Union of Great Britain, an Edinburgh publication printed by the Heirs of Anderson. The book was not published anonymously and cites Defoe twice as being its author. The book attempts to explain the facts leading up to the Act of Union 1707, dating all the way back to 6 December 1604 when King James I was presented with a proposal for unification. This so-called “first draft” for unification took place 100 years before the signing of the 1707 accord, which respectively preceded the commencement of Robinson Crusoe by another ten years.

Defoe began his campaign in The Review and other pamphlets aimed at English opinion, claiming that it would end the threat from the north, gaining for the Treasury an “inexhaustible treasury of men”, a valuable new market increasing the power of England. By September 1706, Harley ordered Defoe to Edinburgh as a secret agent to do everything possible to help secure acquiescence in the Treaty of Union. He was conscious of the risk to himself. Thanks to books such as The Letters of Daniel Defoe (edited by G. H. Healey, Oxford 1955), far more is known about his activities than is usual with such agents.

His first reports included vivid descriptions of violent demonstrations against the Union. “A Scots rabble is the worst of its kind”, he reported. Years later John Clerk of Penicuik, a leading Unionist, wrote in his memoirs that it was not known at the time that Defoe had been sent by Godolphin: … to give a faithful account to him from time to time how everything past here. He was therefor a spy among us, but not known to be such, otherways the Mob of Edin. had pull him to pieces.

Defoe was a Presbyterian who had suffered in England for his convictions, and as such he was accepted as an adviser to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland and committees of the Parliament of Scotland. He told Harley that he was “privy to all their folly” but “Perfectly unsuspected as with corresponding with anybody in England”. He was then able to influence the proposals that were put to Parliament and reported,

Having had the honour to be always sent for the committee to whom these amendments were referrèd, I have had the good fortune to break their measures in two particulars via the bounty on Corn andproportion of the Excise.

For Scotland, he used different arguments, even the opposite of those which he used in England, usually ignoring the English doctrine of the Sovereignty of Parliament, for example, telling the Scots that they could have complete confidence in the guarantees in the Treaty. Some of his pamphlets were purported to be written by Scots, misleading even reputable historians into quoting them as evidence of Scottish opinion of the time. The same is true of a massive history of the Union which Defoe published in 1709 and which some historians still treat as a valuable contemporary source for their own works. Defoe took pains to give his history an air of objectivity by giving some space to arguments against the Union but always having the last word for himself.

He disposed of the main Union opponent, Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, by ignoring him. Nor does he account for the deviousness of the Duke of Hamilton, the official leader of the various factions opposed to the Union, who seemingly betrayed his former colleagues when he switched to the Unionist/Government side in the decisive final stages of the debate.

Defoe made no attempt to explain why the same Parliament of Scotland which was so vehement for its independence from 1703 to 1705 became so supine in 1706. He received very little reward from his paymasters and of course no recognition for his services by the government. He made use of his Scottish experience to write his Tour thro’ the whole Island of Great Britain, published in 1726, where he admitted that the increase of trade and population in Scotland which he had predicted as a consequence of the Union was “not the case, but rather the contrary”.

Defoe’s description of Glasgow (Glaschu) as a “Dear Green Place” has often been misquoted as a Gaelic translation for the town’s name. The Gaelic Glas could mean grey or green, while chu means dog or hollow. Glaschu probably means “Green Hollow”. The “Dear Green Place”, like much of Scotland, was a hotbed of unrest against the Union. The local Tron minister urged his congregation “to up and anent for the City of God”.

The “Dear Green Place” and “City of God” required government troops to put down the rioters tearing up copies of the Treaty at almost every mercat cross in Scotland. When Defoe visited in the mid-1720s, he claimed that the hostility towards his party was “because they were English and because of the Union, which they were almost universally exclaimed against”.

Late writing

The extent and particulars are widely contested concerning Defoe’s writing in the period from the Tory fall in 1714 to the publication of Robinson Crusoe in 1719. Defoe comments on the tendency to attribute tracts of uncertain authorship to him in his apologia Appeal to Honour and Justice (1715), a defence of his part in Harley’s Tory ministry (1710–1174). Other works that anticipate his novelistic career include The Family Instructor (1715), a conduct manual on religious duty; Minutes of the Negotiations of Monsr. Mesnager (1717), in which he impersonates Nicolas Mesnager, the French plenipotentiary who negotiated the Treaty of Utrecht (1713); and A Continuation of the Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy (1718), a satire of European politics and religion, ostensibly written by a Muslim in Paris.

From 1719 to 1724, Defoe published the novels for which he is famous (see below). In the final decade of his life, he also wrote conduct manuals, including Religious Courtship (1722), The Complete English Tradesman (1726) and The New Family Instructor (1727). He published a number of books decrying the breakdown of the social order, such as The Great Law of Subordination Considered (1724) and Everybody’s Business is Nobody’s Business (1725) and works on the supernatural, like The Political History of the Devil (1726), A System of Magick (1727) and An Essay on the History and Reality of Apparitions (1727). His works on foreign travel and trade include A General History of Discoveries and Improvements (1727) and Atlas Maritimus and Commercialis (1728). Perhaps his greatest achievement with the novels is the magisterial A tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain (1724–1727), which provided a panoramic survey of British trade on the eve of the Industrial Revolution.

The Complete English Tradesman

Published in 1726, The Complete English Tradesman is an example of Defoe’s political works. He discusses the role of the tradesman in England in comparison to tradesmen internationally, arguing that the British system of trade is far superior. He also implies that trade is the backbone of the British economy: “estate’s a pond, but trade’s a spring.” He praises the practicality of trade not only within the economy but the social stratification as well. Most of the British gentry, he argues is at one time or another inextricably linked with the institution of trade, either through personal experience, marriage or genealogy. Oftentimes younger members of noble families entered into trade. Marriage to a tradesman’s daughter by a nobleman was also common. Overall Defoe demonstrated a high respect for tradesmen, being one himself.

Not only does Defoe elevate individual British tradesmen to the level of gentleman, but he praises the entirety of British trade as a superior system. Trade, Defoe argues is a much better catalyst for social and economic change than war. He states that through imperialism and trade expansion the British empire is able to “increase commerce at home” through job creation and increased consumption. He states that increased consumption, by laws of supply and demand, increases production and in turn raises wages for the poor therefore lifting part of British society further out of poverty.

Robinson Crusoe

Published in his late fifties, this novel relates the story of a man’s shipwreck on a desert island for twenty-eight years and his subsequent adventures. Throughout its episodic narrative, Crusoe’s struggles with faith are apparent as he bargains with God in times of life-threatening crises, but time and again he turns his back after his deliverances. He is finally content with his lot in life, separated from society, following a more genuine conversion experience. Usually read as fiction, a coincidence of background geography suggests that this may be non-fiction. In the opening pages of The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, the author describes how Crusoe settled in Bedford, married and produced a family, and that when his wife died, he went off on these further adventures. Bedford is also the place where the brother of “H. F.” in A Journal of the Plague Year retired to avoid the danger of the plague, so that by implication, if these works were not fiction, Defoe’s family met Crusoe in Bedford, from whence the information in these books was gathered. Defoe went to school in Stoke Newington, London, with a friend named Caruso.

The novel has been assumed to be based in part on the story of the Scottish castaway Alexander Selkirk, who spent four years stranded in the Juan Fernández Islands, but this experience is inconsistent with the details of the narrative. The island Selkirk lived on was named Más a Tierra (Closer to Land) at the time and was renamed Robinson Crusoe Island in 1966. It has been supposed that Defoe may have also been inspired by the Latin or English translation of a book by the Andalusian-Arab Muslim polymath Ibn Tufail, who was known as “Abubacer” in Europe. The Latin edition of the book was entitled Philosophus Autodidactus and it was an earlier novel that is also set on a deserted island.

Captain Singleton

Defoe’s next novel was Captain Singleton (1720), an adventure story whose first half covers a traversal of Africa and whose second half taps into the contemporary fascination with piracy. It has been commended for its sensitive depiction of the close relationship between the hero and his religious mentor, Quaker William Walters.

Memoirs of a Cavalier

Memoirs of a Cavalier (1720) is set during the Thirty Years’ War and the English Civil War.

A Journal of the Plague Year

A novel often read as non-fiction, this is an account of the Great Plague of London in 1665. It is undersigned by the initials “H. F.”, suggesting the author’s uncle Henry Foe as its primary source. It is an historical account of the events based on extensive research, published in 1722.

Bring out your dead! The ceaseless chant of doom echoed through a city of emptied streets and filled grave pits. For this was London in the year of 1665, the Year of the Great Plague … In 1721, when the Black Death again threatened the European Continent, Daniel Defoe wrote “A Journal of the Plague Year” to alert an indifferent populace to the horror that was almost upon them. Through the eyes of a saddler who had chosen to remain while multitudes fled, the master realist vividly depicted a plague-stricken city. He re-enacted the terror of a helpless people caught in a tragedy they could not comprehend: the weak preying on the dying, the strong administering to the sick, the sinful orgies of the cynical, the quiet faith of the pious. With dramatic insight he captured for all time the death throes of a great city.—Back cover of the New American Library version of “A Journal of the Plague Year”; Signet Classic, 1960

Colonel Jack

Colonel Jack (1722) follows an orphaned boy from a life of poverty and crime to colonial prosperity, military and marital imbroglios, and religious conversion, driven by a problematic notion of becoming a “gentleman.”

Moll Flanders

Also in 1722, Defoe wrote Moll Flanders, another first-person picaresque novel of the fall and eventual redemption, both material and spiritual, of a lone woman in 17th-century England. The titular heroine appears as a whore, bigamist, and thief, lives in The Mint, commits adultery and incest, and yet manages to retain the reader’s sympathy. Her savvy manipulation of both men and wealth earns her a life of trials but ultimately an ending in reward. Although Moll struggles with the morality of some of her actions and decisions, religion seems to be far from her concerns throughout most of her story. However, like Robinson Crusoe, she finally repents. Moll Flanders is an important work in the development of the novel, as it challenged the common perception of femininity and gender roles in 18th-century British society, and it has come to be widely regarded as an example of erotica.

Moll Flanders and Defoe’s final novel, Roxana: The Fortunate Mistress (1724), are examples of the remarkable way in which Defoe seems to inhabit his fictional characters (yet “drawn from life”), not least in that they are women. Roxana narrates the moral and spiritual decline of a high society courtesan. Roxana differs from other Defoe works because the main character does not exhibit a conversion experience, even though she claims to be a penitent later in her life, at the time that she’s relaying her story.

Daniel Defoe died on 24 April 1731, probably while in hiding from his creditors. He often was in debtors’ prison. The cause of his death was labelled as lethargy, but he probably experienced a stroke. He was interred in Bunhill Fields (today Bunhill Fields Burial and Gardens), Borough of Islington, London, where a monument was erected to his memory in 1870.Defoe is known to have used at least 198 pen names.

Selected works

The Consolidator, or Memoirs of Sundry Transactions from the World in the Moon: Translated from the Lunar Language (1705) Robinson Crusoe (1719) – originally published in two volumes:The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner: Who Lived Eight and Twenty Years [...] The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: Being the Second and Last Part of His Life [...] Serious Reflections During the Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: With his Vision of the Angelick World (1720) Captain Singleton (1720) Memoirs of a Cavalier (1720) A Journal of the Plague Year (1722) Colonel Jack (1722) Moll Flanders (1722) Roxana: The Fortunate Mistress (1724)

Non-fiction

An Essay Upon Projects (1697) – which includes a chapter suggesting a national insurance scheme. The Storm (1704) – describes the worst storm ever to hit Britain in recorded times. Includes eyewitness accounts. Atlantis Major (1711) The Family Instructor (1715) Memoirs of the Church of Scotland (1717) The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard (1724) – describing Sheppard’s life of crime and concluding with the miraculous escapes from prison for which he had become a public sensation. A Narrative of All The Robberies, Escapes, &c. of John Sheppard (1724) – written by or taken from Sheppard himself in the condemned cell before he was hanged for theft, apparently by way of conclusion to the Defoe work. A tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain, divided into circuits or journies (1724–1727) The Political History of the Devil (1726) The Complete English Tradesman (1726) A treatise concerning the use and abuse of the marriage bed... (1727) A Plan of the English Commerce (1728)

Pamphlets or essays in prose

The Poor Man’s Plea (1698) The History of the Kentish Petition (1701) The Shortest Way with the Dissenters (1702) The Great Law of Subordination Consider’d (1704) Giving Alms No Charity, and Employing the Poor (1704) An Appeal to Honour and Justice, Tho’ it be of his Worst Enemies, by Daniel Defoe, Being a True Account of His Conduct in Publick Affairs (1715) A Vindication of the Press: Or, An Essay on the Usefulness of Writing, on Criticism, and the Qualification of Authors (1718) Every-body’s Business, Is No-body’s Business (1725) The Protestant Monastery (1726) Parochial Tyranny (1727) Augusta Triumphans (1728) Second Thoughts are Best (1729) An Essay Upon Literature (1726) Mere Nature Delineated (1726) Conjugal Lewdness (1727)

Pamphlets or essays in verse

The True-Born Englishman: A Satyr (1701) Hymn to the Pillory (1703) An Essay on the Late Storm (1704)

Some contested works attributed to Defoe

A Friendly Epistle by way of reproof from one of the people called Quakers, to T. B., a dealer in many words (1715). The King of Pirates (1719) – purporting to be an account of the pirate Henry Avery. The Pirate Gow (1725) – an account of John Gow. A General History of the Pyrates (1724, 1725, 1726, 1828) – published in two volumes by Charles Rivington, who had a shop near St. Paul’s Cathedral, London. Published under the name of Captain Charles Johnson, it sold in many editions. Captain Carleton’s Memoirs of an English Officer (1728). The life and adventures of Mrs. Christian Davies, commonly call’d Mother Ross (1740) – published anonymously; printed and sold by R. Montagu in London; and attributed to Defoe but more recently not accepted.

Wikipedia—https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Defoe

The Education of Women, by Daniel Defoe

'To such whose genius would lead them to it, I would deny no sort of learning'

Heritage Images/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Best known as the author of " Robinson Crusoe " (1719), Daniel Defoe was an extremely versatile and prolific author. A journalist as well as a novelist, he produced more than 500 books, pamphlets, and journals.

The following essay first appeared in 1719, the same year in which Defoe published the first volume of Robinson Crusoe. Observe how he directs his appeals to a male audience as he develops his argument that women should be allowed full and ready access to education.

The Education of Women

by Daniel Defoe

I have often thought of it as one of the most barbarous customs in the world, considering us as a civilized and a Christian country, that we deny the advantages of learning to women. We reproach the sex every day with folly and impertinence; while I am confident, had they the advantages of education equal to us, they would be guilty of less than ourselves.

One would wonder, indeed, how it should happen that women are conversible at all; since they are only beholden to natural parts, for all their knowledge. Their youth is spent to teach them to stitch and sew or make baubles. They are taught to read, indeed, and perhaps to write their names, or so; and that is the height of a woman’s education. And I would but ask any who slight the sex for their understanding, what is a man (a gentleman, I mean) good for, that is taught no more? I need not give instances, or examine the character of a gentleman, with a good estate, or a good family, and with tolerable parts; and examine what figure he makes for want of education.

The soul is placed in the body like a rough diamond; and must be polished, or the luster of it will never appear. And ’tis manifest, that as the rational soul distinguishes us from brutes; so education carries on the distinction, and makes some less brutish than others. This is too evident to need any demonstration. But why then should women be denied the benefit of instruction? If knowledge and understanding had been useless additions to the sex, GOD Almighty would never have given them capacities; for he made nothing needless. Besides, I would ask such, What they can see in ignorance, that they should think it a necessary ornament to a woman? or how much worse is a wise woman than a fool? or what has the woman done to forfeit the privilege of being taught? Does she plague us with her pride and impertinence? Why did we not let her learn, that she might have had more wit? Shall we upbraid women with folly, when ’tis only the error of this inhuman custom, that hindered them from being made wiser?

The capacities of women are supposed to be greater, and their senses quicker than those of the men; and what they might be capable of being bred to, is plain from some instances of female wit, which this age is not without. Which upbraids us with Injustice, and looks as if we denied women the advantages of education, for fear they should vie with the men in their improvements.

[They] should be taught all sorts of breeding suitable both to their genius and quality. And in particular, Music and Dancing; which it would be cruelty to bar the sex of, because they are their darlings. But besides this, they should be taught languages, as particularly French and Italian: and I would venture the injury of giving a woman more tongues than one. They should, as a particular study, be taught all the graces of speech , and all the necessary air of conversation ; which our common education is so defective in, that I need not expose it. They should be brought to read books, and especially history; and so to read as to make them understand the world, and be able to know and judge of things when they hear of them.

To such whose genius would lead them to it, I would deny no sort of learning; but the chief thing, in general, is to cultivate the understandings of the sex, that they may be capable of all sorts of conversation; that their parts and judgments being improved, they may be as profitable in their conversation as they are pleasant.

Women, in my observation, have little or no difference in them, but as they are or are not distinguished by education. Tempers, indeed, may in some degree influence them, but the main distinguishing part is their Breeding.

The whole sex are generally quick and sharp. I believe, I may be allowed to say, generally so: for you rarely see them lumpish and heavy, when they are children; as boys will often be. If a woman be well bred, and taught the proper management of her natural wit, she proves generally very sensible and retentive.

And, without partiality, a woman of sense and manners is the finest and most delicate part of God's Creation, the glory of Her Maker, and the great instance of His singular regard to man, His darling creature: to whom He gave the best gift either God could bestow or man receive. And ’tis the sordidest piece of folly and ingratitude in the world, to withhold from the sex the due luster which the advantages of education gives to the natural beauty of their minds.

A woman well bred and well taught, furnished with the additional accomplishments of knowledge and behavior, is a creature without comparison. Her society is the emblem of sublimer enjoyments, her person is angelic, and her conversation heavenly. She is all softness and sweetness, peace, love, wit, and delight. She is every way suitable to the sublimest wish, and the man that has such a one to his portion, has nothing to do but to rejoice in her, and be thankful.

On the other hand, Suppose her to be the very same woman, and rob her of the benefit of education, and it follows—-

If her temper be good, want of education makes her soft and easy.

Her wit, for want of teaching, makes her impertinent and talkative.

Her knowledge, for want of judgment and experience, makes her fanciful and whimsical.

If her temper be bad, want of breeding makes her worse; and she grows haughty, insolent, and loud.

If she be passionate, want of manners makes her a termagant and a scold, which is much at one with Lunatic.

If she be proud, want of discretion (which still is breeding) makes her conceited, fantastic, and ridiculous.

And from these she degenerates to be turbulent, clamorous, noisy, nasty, the devil!--

The great distinguishing difference, which is seen in the world between men and women, is in their education; and this is manifested by comparing it with the difference between one man or woman, and another.

And herein it is that I take upon me to make such a bold assertion, That all the world are mistaken in their practice about women. For I cannot think that God Almighty ever made them so delicate, so glorious creatures; and furnished them with such charms, so agreeable and so delightful to mankind; with souls capable of the same accomplishments with men: and all, to be only Stewards of our Houses, Cooks, and Slaves.

Not that I am for exalting the female government in the least: but, in short, I would have men take women for companions, and educate them to be fit for it. A woman of sense and breeding will scorn as much to encroach upon the prerogative of man, as a man of sense will scorn to oppress the weakness of the woman. But if the women’s souls were refined and improved by teaching, that word would be lost. To say, the weakness of the sex, as to judgment, would be nonsense; for ignorance and folly would be no more to be found among women than men.

I remember a passage, which I heard from a very fine woman. She had wit and capacity enough, an extraordinary shape and face, and a great fortune: but had been cloistered up all her time; and for fear of being stolen, had not had the liberty of being taught the common necessary knowledge of women’s affairs. And when she came to converse in the world, her natural wit made her so sensible of the want of education, that she gave this short reflection on herself: "I am ashamed to talk with my very maids," says she, "for I don’t know when they do right or wrong. I had more need go to school, than be married."

I need not enlarge on the loss the defect of education is to the sex; nor argue the benefit of the contrary practice. ’Tis a thing will be more easily granted than remedied. This chapter is but an Essay at the thing: and I refer the Practice to those Happy Days (if ever they shall be) when men shall be wise enough to mend it.

- What Is a Past Progressive Verb in English?

- What Is Dialect Prejudice?

- What Is Reflected Meaning?

- Pied-Piping: Grammatical Movements in English

- Understanding Split Infinitives

- Modern English (language)

- Definition and Examples of Anticlimax in Rhetoric

- Everyday vs. Every Day: How to Choose the Right Word

- What Is Euphony in Prose?

- Imply vs. Infer: How to Choose the Right Word

- West African Pidgin English (WAPE)

- Key Events in the History of the English Language

- Sentence Imitation in English

- Precedence, Precedents, and Presidents

- Defining and Understanding Literacy

- Discourse Domain

Daniel Defoe

(1660-1731)

Who Was Daniel Defoe?

Daniel Defoe became a merchant and participated in several failing businesses, facing bankruptcy and aggressive creditors. He was also a prolific political pamphleteer which landed him in prison for slander. Late in life he turned his pen to fiction and wrote Robinson Crusoe , one of the most widely read and influential novels of all time.

Daniel Foe, born circa 1660, was the son of James Foe, a London butcher. Daniel later changed his name to Daniel Defoe, wanting to sound more gentlemanly.

Defoe graduated from an academy at Newington Green, run by the Reverend Charles Morton. Not long after, in 1683, he went into business, having given up an earlier intent on becoming a dissenting minister. He traveled often, selling such goods as wine and wool, but was rarely out of debt. He went bankrupt in 1692 (paying his debts for nearly a decade thereafter), and by 1703, decided to leave the business industry altogether.

Acclaimed Writer

Having always been interested in politics, Defoe published his first literary piece, a political pamphlet, in 1683. He continued to write political works, working as a journalist, until the early 1700s. Many of Defoe's works during this period targeted support for King William III, also known as "William Henry of Orange." Some of his most popular works include The True-Born Englishman, which shed light on racial prejudice in England following attacks on William for being a foreigner; and the Review , a periodical that was published from 1704 to 1713, during the reign of Queen Anne, King William II's successor. Political opponents of Defoe's repeatedly had him imprisoned for his writing in 1713.

Defoe took a new literary path in 1719, around the age of 59, when he published Robinson Crusoe , a fiction novel based on several short essays that he had composed over the years. A handful of novels followed soon after—often with rogues and criminals as lead characters—including Moll Flanders , Colonel Jack , Captain Singleton , Journal of the Plague Year and his last major fiction piece, Roxana (1724).

In the mid-1720s, Defoe returned to writing editorial pieces, focusing on such subjects as morality, politics and the breakdown of social order in England. Some of his later works include Everybody's Business is Nobody's Business (1725); the nonfiction essay "Conjugal Lewdness: or, Matrimonial Whoredom" (1727); and a follow-up piece to the "Conjugal Lewdness" essay, entitled "A Treatise Concerning the Use and Abuse of the Marriage Bed."

Death and Legacy

Defoe died on April 24, 1731. While little is known about Defoe's personal life—largely due to a lack of documentation—Defoe is remembered today as a prolific journalist and author, and has been lauded for his hundreds of fiction and nonfiction works, from political pamphlets to other journalistic pieces, to fantasy-filled novels. The characters that Defoe created in his fiction books have been brought to life countless times over the years, in editorial works, as well as stage and screen productions.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Daniel Defoe

- Birth Year: 1660

- Birth City: London

- Birth Country: United Kingdom

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: English novelist, pamphleteer and journalist Daniel Defoe is best known for his novels 'Robinson Crusoe' and 'Moll Flanders.'

- Fiction and Poetry

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Academy at Newington Green

- Death Year: 1731

- Death date: April 24, 1731

- Death City: London

- Death Country: United Kingdom

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Daniel Defoe Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/daniel-defoe

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: October 26, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Watch Next .css-16toot1:after{background-color:#262626;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Famous British People

Stephen Hawking

Gordon Ramsay

Kiefer Sutherland

Amy Winehouse

Mick Jagger

Agatha Christie

Alexander McQueen

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Biography of Daniel Defoe

By the time he took up his pen to write Robinson Crusoe at about the age of fifty-eight, Daniel Defoe had a broader range of experiences behind him than most can claim in a lifetime. At one time or another he was a merchant, a manufacturer, an insurer of ships, a convict, a soldier, an embezzler, a spy, a fugitive, a political spokesman, and, of course, an author. He produced over five hundred works on politics, geography, crime, religion, superstition, marriage, and psychology. Many critics and historians consider him the first true novelist.

Defoe's life was, to say the least, a strange one. He was born Daniel Foe to a family of Dissenters in the parish of St. Giles, Cripplegate, London; his exact birth date is unknown, but historians estimate the year to be either 1659 or 1660. Why he added the "De" to his surname is a subject of speculation; he might have decided to return to an original family name, or wanted to give himself a high-born cachet. In any event, in his mid-thirties he began signing his name as Defoe. James Foe, his father, a butcher by trade, was a sober, deeply pious Presbyterian of Flemish descent - one of perhaps twenty percent of the population that had relinquished ties to the main body of the Church of England. Very little is known of Defoe's childhood. However, it is reasonable to assume that, as the son of a Dissenter, much of his time was spent in religious observances. It is likely that this spurred the fervent belief in Divine Providence that is so evident in his writings. Since they were barred from Oxford and Cambridge universities, Dissenters sent their children to their own schools. Defoe's education began in the Rev. James Fisher's school in Dorking, and later, at about the age of fourteen, he was enrolled in the Dissenting academy in Newington Green. Newington's headmaster, Rev. Charles Morton, a plain-spoken Puritan, was a progressive educator (despite a belief in storks spending the winter on the moon). He gave his students a thorough grounding in English as well as the customary Greek and Latin. Morton is seen as a major influence on Defoe's writing style; another primary influence was the Bible.

Although intended for the ministry, Defoe settled instead on a career as a commission agent. For more than a decade he traded in a wide range of goods, including stockings, wine, tobacco, and oysters. Defoe's love for trade permeated his writings. He wrote countless essays and pamphlets on economic theory which were advanced for his time. Indeed, had he taken his own advice, he would have been a wealthy man. While his years as a broker endowed him with insight into human nature, his risky and unscrupulous ventures (he was sued at least eight times, and once bilked his own mother-in-law out of four hundred pounds in a cat-breeding deal), combined with bad luck and faulty judgment, more often than not steered him into debt, deceit, and political double-dealing. Still, in his mind and heart, Defoe undoubtedly saw himself in the role of a solid, middle-class family man. He wrote numerous treatises which demonstrated that he considered himself an expert on most, if not all, family matters. However, his own marriage to Mary Tuffley, a merchant's daughter, despite its length of forty-seven years and fecundity of eight children, cannot be considered a model of matrimonial paradise. Defoe's unstable fortunes, his extended visits abroad, and his absence while a fugitive from enemies and creditors would have tried the patience of even the most patient, loving spouse. There is also evidence that, in spite of loving them deeply, Defoe alienated some, if not all of his children. A year after his marriage, Defoe took up arms as a Dissenter in Monmouth's failed rebellion against the Catholic King James II. Unlike three of his former classmates who were caught and sent to the gallows, Defoe narrowly missed the troops and hastened to safety in London. When the king was deposed, Daniel rode with the volunteer guard of honor that escorted William of Orange and his wife Mary into the city.

Due mainly to losses incurred by insuring ships during a war with France, Defoe faced bankruptcy in 1692. With creditors hot on his trail he fled to a debtor sanctuary in Bristol, and from there was able to negotiate terms that spared him the humiliation of debtor's prison. Within ten years he had repaid most of what he owed. Unfortunately, Defoe never fully recovered from that fiasco. Debt would haunt him as long as he lived. This circumstance manifested itself in his ambivalent political actions and his prodigious output as a writer. He was able to win King William's favor, and was appointed Commissioner of the Glass Duty. He was put in charge of proceeds from a lottery and became the king's confidential advisor and leading pamphleteer. Defoe's fervent sense of justice often led him to tweak the noses of those in high places. His essay, The Shortest Way with the Dissenters , would bring him great grief. A satire that poked fun at the manner in which the Church and State dealt with Dissenters, it infuriated the powers that be and forced Defoe to go into hiding. He was betrayed by an informant and brought to trial for "seditious libel against the Church". He was jailed and sentenced to three days in the pillory, a manacle device that exposed a criminal to public ridicule.

A pardon some months later from Queen Anne was hardly a chance to start over. Defoe's tile and brick business had fallen apart during his absence, and he once again faced debtor's prison. A grant of one thousand pounds from the Earl of Oxford allowed Defoe to climb out of debt and start his own newspaper, The Review . He trumpeted his own views and was frequently in trouble for them. After another libel arrest in 1715, Defoe spent his time covertly editing other newspapers as he worked on novels such as Robinson Crusoe , Roxana (1724), A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), and Moll Flanders (1722). He died on April 24th, 1731 of a stroke and was buried in Bunhill Fields, a cemetery for Dissenters. His wife was buried with him on December 19th of that same year.

Study Guides on Works by Daniel Defoe

The consolidator daniel defoe.

The Consolidator or, Memoirs of Sundry Transactions from the World in the Moon, is a 1705 satirical fantasy/science fiction novel by English author Daniel Defoe, of Robinson Crusoe fame.

As described by Karen Severud Cook in her article "Daniel...

- Study Guide

An Essay Upon Projects Daniel Defoe

An Essay Upon Projects was the very first work of literature to which Daniel Defoe publicly signed his name as author. Lacking neither ambition nor audaciousness, the essays lays out over the court of more 50,000 words a detailed and comprehensive...

A Journal of the Plague Year Daniel Defoe

A Journal of the Plague Year is one of Daniel Defoe's most popular and strangest works; it is an amalgam of history and fiction that attempts to relate what life was like in London during the plague of 1665-66. Published in 1722, nearly 57 years...

Moll Flanders Daniel Defoe

Moll Flanders, published in 1722, was one of the earliest English novels (the earliest is probably Aphra Behn's Oroonoko, published in 1688). Like many early novels, it is told in the first person as a narrative, and is presented as a truthful...

Robinson Crusoe Daniel Defoe

The adventures of Crusoe on his island, the main part of Defoe's novel, are based largely on the central incident in the life of an undisciplined Scotsman, Alexander Selkirk. Although it is possible, even likely that Defoe met Selkirk before he...

- Lesson Plan

Roxana: The Fortunate Mistress Daniel Defoe

The novel now known as Roxana was published in 1724; it is the third and last of Defoe's major novels, following Robinson Crusoe in 1719, and Moll Flanders in 1722. The original title was The Fortunate Mistress: Or, A History of the Life and Vast...

We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

An essay on the history and reality of apparitions. : Being an account of what they are, and what they are not; whence they come, and whence they come not. As also how we may distinguish between the apparitions of good and evil spirits and how we ought to behave to them. With a great variety of surprizing and diverting examples, never publish'd before

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

3,095 Views

20 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by [email protected] on April 1, 2009

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- The Education Of Women Daniel Defoe

Education has been a topic of great interest throughout history. Women in particular have been subjected to many restrictions and limitations when it comes to education. In ancient times, women were not even allowed to receive an education at all. Even during the height of the Greek and Roman empires, women were largely excluded from educational opportunities.

This changed somewhat during the medieval period, when some women began to receive instruction in religious studies and other topics. However, it was not until the Renaissance that women began to gain significant ground in the realm of education.

During the Renaissance, certain women began to emerge as highly educated individuals. One such woman was Isabella d’Este, who was born into a noble family in Italy and received an excellent education. She went on to become a well-known patron of the arts and an important figure in Renaissance society.

Another example is the French writer Christine de Pizan, who was one of the first women to produce works of literature in the vernacular language. Education among women began to spread during this time, though it remained largely confined to the upper classes.

The situation changed dramatically during the Enlightenment, when education became more widely available and emphasis was placed on reason and individualism. This led to a greater push for educational opportunities for women, who were seen as capable of Reason just like men. One important figure in this movement was Mary Wollstonecraft, an English writer who argued forcefully for equal education for women and girls. Education began to spread more evenly during this period, though it still lagged behind that of men.

The situation continued to improve throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, as women increasingly fought for and gained access to educational opportunities. In recent years, girls’ education has become a major focus of international development efforts, as it is seen as critical to empowering women and achieving gender equality. Education is continuing to evolve, and there is no doubt that women will play an even more important role in shaping its future.

In “The Education of Women,” Daniel Defoe argued that women’s education should be more valued than it was at the time. England in the early 1700s was mostly Christian, so Defoe likely targeted men and other Christians in his essay. By advocating for better treatment of women according to God’s will, Defoe could gain credibility and a moral high ground with readers.

He writes “The Education of Women” not only because he believes that women should be educated but also because he assumes that if women were given the opportunity to be educated then they could be better wives, mothers and citizens.

Defoe opens his essay by stating that “the Education of Women” is more necessary than that of Men because they are the Education of the next Generation. He believes that if women are not educated then they will not be able to properly educate their children. Defoe believes that it is Women who have the greatest influence over their children and that if they are not educated then the next generation will be at a disadvantage.

He goes on to say that Women are capable of being as intelligent as Men, but they are not given the same opportunities to develop their intelligence. He argues that Women should be given the same educational opportunities as Men so that they can reach their full potential.

Though his reasoning for why women needed an education may not be well-founded, he effectively captures his reader’s attention from the beginning by referencing God throughout the essay. By starting each sentence with his opinion then referring to God in the next breath, he keeps His audience engaged until the very end.

He argues that there are two types of education, the first being “ornamental” and the second being “useful.” He believes that women should only be given the latter type of education as it would make them more virtuous. Education, at this time, was very much a male-dominated institution and Wollstonecraft is adamant that women are just as capable as men when it comes to learning.

She goes on to say that if women are not given an opportunity to be educated then they will be nothing more than pretty objects for men to look at. This is a view that would have been quite controversial at the time but one that Wollstonecraft believed strongly in.

In order for women to be educated properly, Wollstonecraft believes that they need to be taught in a way that is suited to their nature. She argues that the current education system does not do this and instead tries to force women into conformity.

She also belief that once women are educated, they will be better able to teach their children and instil good values in them. This is something that she felt was very important as she believed that it would help to create a better society overall.

Wollstonecraft’s essay is a stirring defence of the importance of educating women. She highlights the many ways in which such an education would benefit both women and society as a whole. Though her views may have been controversial at the time, they are certainly very thought-provoking and offer an interesting perspective on the role of women in society.

In this essay, Defoe included the following rhetorical sentence: “the soul is placed in the body like a rough diamond, and must be polished, or the luster of it will never appear.” His analogy is that if you don’t polish the diamond (women and educating them), then they will never shine.

Education is important for both genders but it has been seen as more important for boys/men. In the past, women were not given the same educational opportunities as men and this has led to a number of inequalities between the sexes.

Education is a key factor in ensuring that women are able to participate fully in society and the economy. Women with higher levels of education often have better employment prospects and earn higher incomes. They are also less likely to experience violence, and more likely to have healthier children.

Despite the clear benefits of education for women, there remains a significant gender gap in many parts of the world. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, only around 40% of women are literate, compared to around two-thirds of men. In South Asia, the figure is just over half for women, compared to three-quarters of men.

There are a number of reasons for this gender disparity in education. One is that girls and women often face discrimination within the education system. They may be discouraged from attending school, or may be segregated into lower-quality schools with fewer resources. They may also be subject to gender-based violence, both within and outside of school.

In conclusion, Defoe argues that Women’s Education is not only necessary for the good of society but also for the good of the individual woman. He believes that if women are given the opportunity to be educated then they will be able to contribute more to society and lead happier lives. Education, at this time, was very much a male-dominated institution and Wollstonecraft is adamant that women are just as capable as men when it comes to learning. Though her views may have been controversial at the time, she makes a strong case for the importance of educating women.

More Essays

- Women In Western Society

- College Essay On The Importance Of Education

- The Importance Of Education Essay

- Men and Women

- Essay about Education In Prisons

- “Immune to Reality” by Daniel Gilbert, and” An Army of One: Me” by Jean Twenge

- Invisible Man Role Of Education Essay

- Women’s Rights In Afghanistan Essay

- Deep Practice Daniel Coyle Analysis Research Paper

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Try AI-powered search

Six novels you can read in a day

Reluctant to start on a big masterpiece try these small gems instead.

F OR A SMALL format the novella carries a lot of baggage—starting with its diminutive. It has long been seen as the middle child of the literary world: it is neither the fully fledged novel, nor the fussed-over baby of the literary family, the short story. Presented with a work of between 60 and 160 pages, agents and editors typically tell an author to scale up or pare back. Melville House, an independent publisher in New York that prides itself on publishing novellas, calls them a “renegade art form”.

In its economy and audacity, an exceptional novella comes close to poetry. It doesn’t overstay its welcome. You can read one in the time it takes to watch a play or a film, then rise from your chair with the exhilaration of having finished a work in one sitting. Zipping through several novellas can cultivate a reading habit. Many of the greatest authors have written at least one: James Joyce (“The Dead”), Ernest Hemingway (“The Old Man and the Sea”), Mary Shelley (“Mathilda”) and Leo Tolstoy (“The Death of Ivan Ilyich”), to name just a few. Here are six short novels that may enchant you.

Small Things Like These. By Claire Keegan. Grove Atlantic; 128 pages; $20. Faber & Faber; £12.99

A hard-working coal merchant with a tidy life stumbles upon a scandal, and finds a deep, unstoppable need to do what is right. There is nothing easy about that: Bill Furlong must set aside his wife’s pleas and the warnings of villagers—well-intentioned yet also complicit—who urge him to ignore what he saw in the coal shed of a convent. He knows that his actions will hurt his daughters’ prospects for an education. “Once more the ordinary part of him simply wanted to be rid of this and get on home.” Furlong does not—finds he cannot—give in to it. The book’s gorgeous use of symbolism is reminiscent at times of a fairytale: crows roost around the convent, strutting and cawing ominously. But the crime it depicts is all too real, rooted in the history of the Magdalene laundries in Ireland run by the Roman Catholic Church. “Small Things Like These” was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2022, the shortest novel so far to gain that distinction.

Who Will Run the Frog Hospital? By Lorrie Moore. Knopf; 160 pages; $16. Faber & Faber; £9.99

Lorrie Moore’s book captures female adolescence and the intensity of its friendships. Berie, its adult narrator, tries to understand how, after the exuberance and small, wild joys of her teenage years, her life has become so staid and unfulfilling. She recounts a summer spent working at Storyland, a theme park, with her best friend, Sils: “She was my hero, and had been for almost as long as I could remember”. Their days are punctuated by cigarette breaks and jokes; they mock the small-town theme park and its tacky rides. But suddenly they must make a decision that is all too adult. It marks the beginning of the splintering of their friendship: one stays in their hometown, Horsehearts, the other leaves. Looking back, Berie sees the mockery and rebellion that the girls so enjoyed as callow answers to teenage insecurities. Yet her account vibrates with regret for what she has lost. Sils, for a magical while, had helped “keep the busy, roaring strange-tongued world at bay”. Moore’s writing is as luscious and funny as ever.

Open Water. By Caleb Azumah Nelson. Grove Atlantic; 160 pages; $16. Penguin; £9.99

The debut of a British-Ghanaian novelist published in 2021, “Open Water” is a love story that is equal parts graceful, defiant and mournful. The characters are two black British artists living in south-east London, whose blossoming love for each other is tested over the course of a year by racial injustice. Trauma and intimacy are central themes: the narrator must allow himself to soften into love, and work hard to stay there. “Seeing people”, he reflects, “is no small task.” The narrator, who addresses himself as “you” throughout the book, goes unnamed, as does the woman he loves. They share a deep admiration for many of the same black artists, among them Frank Ocean, Zadie Smith and Barry Jenkins, whose creations are referred to throughout the book. Read this while listening to the Spotify playlist that Caleb Azumah Nelson compiled for it.

Bonjour Tristesse. By Françoise Sagan. Translated by Heather Lloyd. Penguin; 112 pages; £9.99

This coming-of-age classic was a sensation when it came out in 1954. Françoise Sagan was just 18 years old. The novel takes place over the course of a summer in the south of France. Cécile, its 17-year-old narrator, spends languorous days at a secluded seaside villa in the company of her father, a philandering widower whom she adores and whose hedonism she emulates, and his latest mistress. When he begins a more serious romance with an old acquaintance, Cécile does everything she can to stop him from marrying, with tragic results. Cécile’s own heady romance—breezy sex with an earnest boy whom she later drops—and her existentialist musings shocked early readers. Questions of freedom, responsibility and how to lead a meaningful life were central to French philosophical thought of the 1950s. The novella’s opening lament is classic Sagan, and probably defined French ennui for a generation: “A strange melancholy pervades me to which I hesitate to give the grave and beautiful name of sorrow.”

Foe. By J.M. Coetzee. Penguin; 160 pages; $16 and £8.99

This is a beautifully imaginative retelling of Daniel Defoe’s “Robinson Crusoe”, written from the perspective of Susan Barton, a woman cast away during a mutiny on a ship. She washes up on the desert island where Cruso (he loses the final “e” in J.M. Coetzee’s novel) and his companion, Friday, have lived for years. In this subversive retelling, Cruso is decidedly unheroic: taciturn, complacent and uninterested in improving his life on the island. Most of the story is told in a series of letters Barton writes after her rescue to Daniel Foe, a novelist. She asks him to help transform her account into a bestselling work of fiction—for in Mr Coetzee’s reimagining, this is her story, not Cruso’s. “Foe” explores the tension between truth and storytelling, and what an author owes to those who inspire him. It is also a woman’s reckoning with losing her power to express herself. But nowhere is that muting clearer, or more thorough, than in the person of Friday, here a black former slave who, for reasons that cannot be known for sure, is tongueless. He cannot even begin to tell his own story.

Masks. By Enchi Fumiko. Translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Vintage; 144 pages; $16.95 and £8.99