- Poetry and Critical Thinking: Unlocking the Power of Reflection

Poetry has always been a medium that encourages deep contemplation and introspection. Through thoughtful exploration of language and imagery, poets have the ability to challenge our preconceived notions, provoke critical thinking, and inspire new perspectives. In this article, we will delve into the world of poetry that centers around critical thinking, showcasing examples that illustrate the profound impact of this literary genre.

Example 1: "The Road Not Taken" by Robert Frost

Example 2: "still i rise" by maya angelou, the power of critical thinking in poetry.

Critical thinking involves analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating information to form reasoned judgments. It is a skill that enables us to question assumptions, challenge biases, and broaden our understanding. Poetry, with its brevity and artistic license, offers a unique platform for fostering critical thinking.

Through the clever use of metaphors, symbolism, and wordplay, poets can convey complex ideas in a condensed form, leaving room for interpretation and reflection. This opens up a dialogue between the poet and the reader, encouraging us to think deeply about the underlying meaning and the broader implications of the words on the page.

"Two roads diverged in a wood, and I— I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference."

Robert Frost's "The Road Not Taken" is a classic example of a poem that prompts critical thinking. On the surface, it speaks of a traveler faced with a choice between two paths. However, upon closer inspection, we realize that the poem is about more than just a physical journey. It is a metaphor for the choices we make in life and the subsequent impact those choices have.

This poem challenges us to reflect upon the decisions we make and the paths we choose, urging us to critically examine whether we are following our own unique path or merely conforming to societal expectations. Frost leaves us with lingering questions, encouraging us to contemplate the significance of our choices and the unforeseen consequences they may bring.

"You may shoot me with your words, You may cut me with your eyes, You may kill me with your hatefulness, But still, like air, I'll rise."

Maya Angelou's powerful poem, "Still I Rise," confronts themes of racism, discrimination, and resilience. By weaving together vivid imagery and a defiant tone, the poem challenges societal norms and encourages critical examination of oppressive systems.

Angelou's words urge us to question the power dynamics at play in our society and to reflect on the ways in which we can rise above adversity. Through her defiant spirit, she inspires critical thinking about the importance of resilience, self-confidence, and the unwavering pursuit of justice.

Poetry and critical thinking are natural companions, both stimulating intellectual curiosity and nourishing the soul. The examples discussed in this article merely scratch the surface of the vast poetic landscape that encourages us to think deeply, question assumptions, and explore new perspectives.

As readers, we should embrace the opportunity to engage with these thought-provoking poems, allowing them to challenge our beliefs, broaden our horizons, and inspire critical thinking in our own lives. With each line of poetry, we embark on a journey of intellectual exploration, an expedition that nurtures our ability to think critically and unlocks the power of reflection.

- Poems That Illuminate the Night Sky: Stars and Constellations

- Funny Poems about Librarians: Celebrating the Unsung Heroes

Entradas Relacionadas

Poems Celebrating Excellence in Education

Poems about Education for Primary Schools: Inspiring Young Minds

The Burden of Homework: Poems that Echo the Struggles

Poems About Teaching Students: Unleashing the Power of Words

African American Poems about Education: Celebrating Knowledge and Empowerment

Poetry in the Age of Standardized Testing

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Literary Fusions

Integrating literacy in K-12 classrooms.

Poetry and the Four C’s: Critical Thinking

April 2, 2017 By Jessica

In honor of April being National Poetry Month, we are excited to bring you a series of blog posts on the 4Cs in poetry. Today’s post will focus on critical thinking. (P.S. This is what we do! We love helping teachers find ways to incorporate innovative teaching strategies into their already existing content! Contact us if you’re interested in a full or half day professional development. )

(Looking for the other 3 Cs? Communication and Collaboration , Creativity – check them out!)

Critical Thinking in Poetry

When students are given a poem, we want them to think critically about the obvious message as well as the implied message. Thinking critically about a poem includes evaluating, analyzing, and interpreting the message, and students must spend plenty of time with the text applying these skills so they are able to explain their interpretations with text evidence. This will not happen overnight or with one lesson! Take your time and scaffold lessons to help students be critical readers of poetry!

The high level of thinking we want from our students will come when they have ample time to practice asking questions about what they are reading, as well as make inferences, and have open discussions about what they are reading. The poem will need to be read many times and there are tools to help! Here are a few:

- Poetry Out Loud . Another great site where students can listen to poetry being recited. A huge difference here is that students are reading the poems instead of the author. There is a lot of power in students seeing other “regular” kids reading poems with enthusiasm. Not to mention, this is an interactive site if the students (and you) would like. Your own students could enter contests and competitions. The first section allows you to listen (just audio) or watch videos of the poem being recited. You can also find poems and you are given tips on reciting poems. While on this site, don’t miss the teacher section ! It has strong lesson plans to help you teach poetry.

- Poetry in Commercials. I always believe we should start with where the students are in their learning. Students are exposed to poetry through music and other media, but sometimes don’t realize it. Commercials the kids perk up to usually have a beat or a poem attached. Use those clips to have students think critically about the poem, why the poem was chosen, and how it is helping to sell the product! And now, we are teaching Media Literacy as well! Here are some videos you might like to share: iPad Air , Nike (wings) , Levi’s , Sprite , and Nike (soccer) .

- For a great list of questions to help you prompt students’ critical thought, check out this site .

Happy Thinking!

Copyright statement.

Content © 2024 Jessica Rogers and Sherry McElhannon of Literary Fusions and literaryfusions.com. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s authors and owners is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Literary Fusions and literaryfusions.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Reader Interactions

January 24, 2018 at 1:46 pm

This great for our 6th grade G/T students.

January 25, 2018 at 7:42 am

Excellent! Please let us know how it goes.

October 27, 2021 at 9:33 pm

Thank you for the information. I am looking for more research about classic poetry and critical thinking.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

literary_fusions

Get integration ideas in your inbox!

The latest posts….

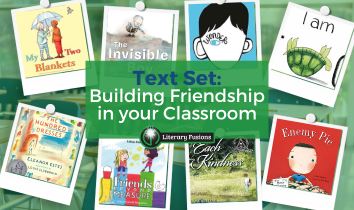

Text Set: Building Friendship in Your Classroom

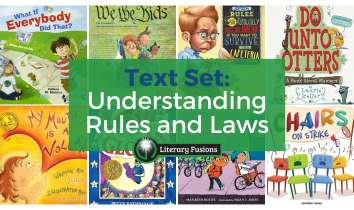

Text Set: Understanding Rules and Laws

Book Review: Imagine You and Me, by Benson Shum

10 of the Best Poems about Thinking and Meditation

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

Thinking and thought loom large in poetry, whether it’s the intellectual exercises of the metaphysical poets, the deep, personal introspection of the Romantics, or the modernists’ interest in subjectivity and interiority. Below, we introduce ten of the greatest introspective poems about thoughts, thinking, and meditation.

William Wordsworth, ‘ Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey ’.

Five years have past; five summers, with the length Of five long winters! and again I hear These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs With a soft inland murmur.—Once again Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs, That on a wild secluded scene impress Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect The landscape with the quiet of the sky…

This poem was not actually composed at Tintern Abbey, but, as the poem’s full title reveals, was written nearby, overlooking the ruins of the medieval priory in the Wye Valley in South Wales.

Well, actually, according to Wordsworth, he didn’t ‘write’ a word of the poem until he got to Bristol, where he wrote down the whole psoem, having composed it in his head shortly after leaving the Wye.

The poem is one of the great hymns to tranquillity, quiet contemplation, and self-examination in all of English literature, and a quintessential piece of Romantic poetry written in meditative blank verse. We’ve analysed this classic Wordsworth poem in detail here .

Walt Whitman, ‘ Thoughts ’.

In this poem, the American pioneer of free verse Walt Whitman (1819-92) offers a series of thoughts about various subjects, all supposedly coming to his mind as he sits there listening to music playing. The poem begins:

Of the visages of things—And of piercing through to the accepted hells beneath; Of ugliness—To me there is just as much in it as there is in beauty—And now the ugliness of human beings is acceptable to me; Of detected persons—To me, detected persons are not, in any respect, worse than undetected per- sons—and are not in any respect worse than I am myself; Of criminals—To me, any judge, or any juror, is equally criminal—and any reputable person is also—and the President is also …

Emily Dickinson, ‘ The Brain is Wider than the Sky ’.

The Brain — is wider than the Sky — For — put them side by side — The one the other will contain With ease — and You — beside —

The Brain is deeper than the sea — For — hold them — Blue to Blue — The one the other will absorb — As Sponges — Buckets — do …

A fine poem about the power of the human mind from one of America’s most distinctive poetic voices. The mind and all that it can take in – and imagine – is far greater than even the vast sky above us. This is the starting point of one of Emily Dickinson’s great meditations on the power of human imagination and comprehension.

Robert Louis Stevenson, ‘A Thought’.

This little four-line poem by the author of Treasure Island and Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is short enough to be quoted in full here. Stevenson was an accomplished author of verse for young children, as this pithy poem demonstrates:

It is very nice to think The world is full of meat and drink, With little children saying grace In every Christian kind of place.

A. E. Housman, ‘ Think No More, Lad; Laugh, Be Jolly ’.

Taken from Housman’s 1896 collection A Shropshire Lad , this poem sees the speaker addressing the titular ‘lad’ from rural Shropshire, imparting the advice that thinking only leads to depression and to death. Best just to enjoy life and go with the flow:

Think no more, lad; laugh, be jolly: Why should men make haste to die? Empty heads and tongues a-talking Make the rough road easy walking, And the feather pate of folly Bears the falling sky …

Walter D. Wintle, ‘ Thinking ’.

Life’s battles don’t always go To the stronger or faster man; But sooner or later the person who wins Is the one who thinks he can!

Wintle is something of a mystery: we don’t even know his precise birth or death dates, other than that he was active in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He is only known for this one poem, about ‘the man who thinks he can’, which espouses a ‘positive mental attitude’ to life. It’s become an influential motivational poem beloved of self-help gurus and businesspeople.

T. S. Eliot, ‘ Introspection ’.

Composed in 1915 but not published until 1996, more than thirty years after Eliot’s death, ‘Introspection’ treads a fine line between free verse and prose poetry, offering an anti-romantic image to convey the idea of soul-searching and meditation: the mind is ‘six feet deep’ in a cistern, with a brown snake devouring its own tail like Ouroboros from Greek myth.

The words of the poem curl round in a barely punctuated circular shape on the page, mimicking the form of the coiled snake …

Kathleen Raine, ‘ Introspection ’.

Perhaps, as Eliot’s poem suggests, introspection is not always a positive, affirmative process. Sometimes, our thoughts may take us to some dark realisations – such as here, in this poem from the twentieth-century poet Kathleen Raine, where thinking and introspection lead her to think about death.

Raine (1908-2003) wrote some beautifully intense poems inspired by William Blake and her own personal mythology, and ‘Introspection’ offers a nice way into her work.

William Stafford, ‘ Just Thinking ’.

Stafford (1914-93) was an American poet. ‘Just Thinking’ is a short poem about the simple act of contemplation – of a landscape, or a momentary scene from nature – and uses the metaphor of incarceration and being ‘on probation’ all one’s life to convey the way we live.

Nikki Giovanni, ‘ Introspection ’.

The American poet Yolande Cornelia ‘Nikki’ Giovanni Jr. was born in 1943, and rose to prominence in the late 1960s as part of the Black Arts Movement. ‘Introspection’ is one of her finest poems, about a woman who prefers to solve her depression and anxiety (she lives constantly ‘on the edge of an emotional abyss’) by doing something ‘concrete’ and practical rather than dealing in ‘abstracts’.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

INQUIRE TODAY (905) 764-6285

Address: 309-300 John Street, Thornhill ( map )

- Feb 28, 2023

Poetry: The Ultimate Exercise in Critical Thinking

Updated: Apr 11, 2023

#CriticalThinking #WritingTutoring

Poetry is a creative format that is meant to convey emotions through the use of various literary devices, such as metaphors, alliterations, rhyming, connotations, and imagery. When listening or reading poetry, the goal of the poet is to evoke a specific emotional and/or sensory experience.

But why is something so ambiguous taught in schools?

The purpose of studying poetry is not to transform children into poets, but rather to give students the opportunity to explore the complexities and variations available in language outside of the strict formal structures they are used to.

This opportunity is elaborated in four ways:

Analyzing Text: With its dense meaning and symbolism, a careful analyzing of a poem's text, structure, themes, and use of language allows students to develop their critical thinking abilities by placing them in an inquisitive mindset.

Making Connections: Poetry derives inspiration from culture, history, emotions, and nature. As a result, the use of abstract vocabulary pushes students to attempt to make other connections, whether they be worldly or personal, to build their inference-based skills.

Perspective-Taking: Since poetry is often thought-provoking and emotional, they are a great way to understand different perspectives and grow empathy, two things crucial to developing strong critical thinking skills.

Creative Thinking: As poetry not only is an exercise in emotional understanding, but it is also an exercise in creativity. Poetry requires a mind that can envision and paint words in order to create connections and deeper thinking.

So, for students that feel lost reading a poem, how can we help them exercise the aforementioned abilities?

Poetry can be overwhelming to a mind that has yet to fully develop and comprehend the complex emotions and perspectives that are often told through this form. Many learners fail to understand this and attempt to learn poetry in a very mechanical manner, when this literary form is so abstract, and no straightforward method can be used effectively for any child.

So what is an easy way to teach poetry, that is also open to adaptability? After you read through the poem, identify whether there are any words the child doesn't understand. Since poetry often uses more complex vocabulary, this will likely be something you come across frequently while reading.

Next, have the student pick out a sentence or stanza in the poem that stands out, or is memorable, or they just happen to like. The goal here is to get them to find some of their own footing first and then have you guide them along the way. This was you are also encouraging them to be more inquisitive with their learning. If they are struggling to find a line, then pick out one that you feel is minimalist and can be interpreted in both simple and complex ways.

With the line chosen, you can now probe deeper as to what the poet is saying, either in a literal sense or figurative sense. The great thing about poetry is while the writer may have a specific theme or idea in their writing, the poem itself can still be ambiguously interpreted. The ideal response is just to have the student make some sort of connection to the poetry that they can explain and make sense of. It does not matter how minimal or far-fetched it is as the idea is just for them to explain their thinking effectively. This then gets the ball rolling as now you can have them identify their perspective and now attempt to tie it into another line of the poem that may sound similar to the first one they had chosen. From here they can begin to visualize the poem as they connect the words and ideas that they have identified from the start.

The other day, one of our teachers was working with a high school student who was having trouble understanding what a poem about loneliness was trying to say, by using examples from nature. She ended up using the exact methods described earlier and as a result, by the end of the hour, the student was able to understand the poem in its entirety as well as be able to connect the whole work together. Poetry is abstract and therefore the way we approach it must also be in some ways abstract as well. When students are first taught how to analyze texts, it's always in a very linear form, meaning they start at the very beginning and analyze in order. The study of poetry breaks this habit and forces you to start at an obscure point and then branch out to connect all the ideas together.

Recent Posts

Friday Brain Workout

"Visual Learners: Understanding through Visual Aid "

Activities for Kids During the Summer that Subtly grows their skills

Iowa Reading Research Center

The Benefits of Poetry Reading

“Poetry begins in trivial metaphors, pretty metaphors, ‘grace’ metaphors, and goes on to the profoundest thinking that we have” (Frost, p. 77-78). This is a quote from Robert Frost’s “Education by Poetry” speech that he gave in 1930, (later published in the Amherst Graduates Quarterly the following year). The poet staunchly believed that reading and writing poetry foster thought and imagination. Even though Frost addressed this notion over ninety years ago, this idea still holds true as readers of poetry continue to analyze literary devices and word choice to uncover the intent of a poem. As poetry evolves with the times through its messages and language structure, students today can approach poetry to explore and further their own understanding of society and themselves. This exploration is seen in novels written in verse —a collection of poems that progress together as an entire story.

In novels written in verse, an entire story arc is conveyed through a collection of poems. Analogous to chapters in a novel, the poems range in length in accordance with the pacing of the story. The integration of the young adult narrative into poetry creates reads that are fast-paced with deliberate and creative word choice, portraying emotional growth that is relatable to students. Books written in verse can be added to the classroom library for independent reading or included in a reading unit. For recommendations, check out our Novels in Verse Reading List (Grades 5-12) .

Focus on Language

“A critical value of poetry in reading instruction is that it focuses the reader’s attention on the language used” (Nichols et al., 2018, p. 391). When we focus on language as we read, we are paying attention to things like word choice, sentence structure, and literary devices. The role of language is one of the factors that differentiates poetry from prose. Language in poetry is part of the story. It is on equal grounds with the story itself. Poetry reading allows students to interact with rhyme schemes, language structures, and word choice. (It is important to note that poetry doesn’t have to rhyme; free verse, in fact, is a genre of poetry that does not have any rhyme scheme or meter. It can provide space for students to explore a range of poetic writing styles). Due to the artistic freedom that poetry reflects, the language structures are unique to each collection, requiring readers to reflect on the language structure and word choice used. Often, the word count is constrained by meter or rhythm, prompting the poet to choose their language very carefully while still maintaining the essence of the poem’s intended message. These carefully chosen words depict very specific emotions and scenes.

Support Student Motivation and Interest

Reading depends largely on motivation, which relies on one’s dedication to furthering their learning. As Cambria and Guthrie (2010) describe, “The reason to read in this case is the students’ belief that reading is important” (p. 18). One way to promote motivation and dedication to reading is to provide students with a range of books to choose from that cover topics that are relevant to students and connect to their interests (Kamil, 2008). Additionally, students may be motivated to read novels in verse because of their fast pace and relatable YA voice. The unique relatability of novels in verse is an application of Rudine Sims Bishop’s assertion that books can be “mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors.” When books are windows, they let readers look into a world that is different from their own, like opening a window and looking out. When books serve as mirrors, they are reflective of the readers themselves—the reader feels that the story is relatable. Lastly, books can be seen as sliding glass doors when they immerse the reader in the world the author has created. Being able to see themselves or empathize with a character in a novel can promote the dedication that a student needs. Finding the genre or writing style that interests students may transform reading into an intrinsic dedication — a desire to read for enjoyment beyond the assigned readings in the classroom.

Discuss Vocabulary

The core elements of reading can be reinforced through poetry instruction as well. One of the core elements of reading identified by the National Reading Panel is vocabulary. It is also one of the strands of the Scarborough Rope model of reading that contributes to language comprehension. Students can develop their vocabulary skills through poetry analysis. Lessons with a focus on precise language, synonyms, and antonyms can provide students with clarity on the effectiveness of vocabulary. A lesson on word choice outlines when a word should or should not be used and how context can shift the meaning of the word.

For example, for a secondary classroom that is reading The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo, the teacher can lead a lesson on word choice and how the words in the poem work individually and together to describe Xiomara’s perspective and the emotional journey that she experiences throughout the novel. The stanza when Xiomara finds her voice to speak against her mother can be analyzed at the word level:

“Burn it! Burn it.

This is where the poems are,” I say,

thumping a fist against my chest.

“Will you burn me, too?” (Acevedo, 2018, p. 308)

From this excerpt, the class can hold a discussion as to how the word “burn” holds the betrayal and independence that Xiomara experiences—the empowerment the teen gets from finally speaking her mind. This heart-wrenching scene draws upon literal and literary meanings in order to showcase its message; her mother literally burned her poems, which are Xiomara’s soul laid bare, so Xiomara feels as though she is figuratively being burned alive. Explicit discussion of literal and figurative meanings will develop students’ comprehension of the selection of poems and/or excerpts being covered.

Consider Literary Devices and Metaphors

Another core component of reading is verbal reasoning, which is the ability to understand figurative language like metaphors, similes, and idioms. Teachers can support students’ development of verbal reasoning by pairing poetry instruction with close reading. Due to the concise narrative that poetry holds, students can zero in on specific stanzas to consider literary devices and metaphors. For example, for a class reading A Time to Dance by Padma Venkatraman, students will be diving into a novel that revolves around injury recovery and dance. Through the imagery and emotional awakening for the characters and the readers, students can be taught to read the poems with a focus on unpacking the metaphors on the page. For example, when Veda suddenly realizes the consequences of her injury, this metaphor strikes a chord: “ My heart feels like it’s at absolute zero”(Venkatraman, 2014). In science, absolute zero is the lowest temperature possible, meaning that particles stop moving. In the literary sense, it could be interpreted to mean that the anger and fear knocked out her optimism and made her numb to the possibility of joy–immobilizing her completely. By unpacking literary devices, readers can gain a broader understanding of the power of word choice. As Nichols et al. (2018) note, “Poetry lends itself to critical thinking, analysis, and the study of literary techniques and devices”(p. 393). Similarly, the Iowa Core Literacy standards require students to “Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative and connotative meanings”(RL.7.4). Participating in a close reading of a poetic text can broaden readers’ understandings of literal and underlying messages.

Given the benefits of teaching poetry, we have created a recommended list of novels in verse to share with students.

Novels in Verse Reading List (Grades 5-12)

The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo (grades 9-12)

Xiomara’s mother has a strict outlook on how she should behave and speak. Feeling silenced and misunderstood, Xiomara writes poems about everything she wishes she could say but knows that she can’t, from her love of writing poetry to faith, friendships, and boys.

House Arrest by K.A. Holt (grades 5-8)

Timothy is a twelve-year-old boy who gets caught stealing a wallet and is put under a year of house arrest. The court orders him to write a journal. Through his journal entries, readers discover that Timothy decided to steal because he was desperate to help his family and his sick baby brother. During this year, Timothy is under constant pressure and just wants his mom to be happy and his baby brother to be healthy.

Lifeboat 12 by Susan Hood (grades 5-8)

Based on a true story, Ken is one of the many children who were supposed to be sent to safety from England to Canada during World War II. However, the ship he was traveling on gets torpedoed, and the children on lifeboat 12 are trying to make it to neutral territory.

Inside Out and Back Again by Thanhha Lai (grades 5-8)

Hà and her family immigrate from Vietnam to the United States during the 1970s. Hà faces challenges that she steadily overcomes: learning English, navigating the culture of the American South, and making friends.

The Magical Imperfect by Chris Baron (grades 5-7)

This book is a story about friendship, community, Filipino culture, Jewish heritage, and mental health. Etan works at a grocery store and is sent on deliveries to a house in the woods where Malia lives. Due to her severe eczema, Malia can’t be out in the sun and has been bullied for her skin condition. Etan and Malia become friends and try to help each other become more confident and pursue their passions even if not everyone is supportive.

Clap When You Land by Elizabeth Acevedo (grades 7-12)

Camino lives in the Dominican. Yahaira lives in New York. Their lives suddenly intersect when their father passes away in a plane crash. The two girls discover that they are sisters, though each girl had been kept a secret by their father. Once the two meet, they find out more about who their father was and discover that maybe he wasn’t as perfect as they thought he was.

Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson (grades 6-12)

This story is based on Woodson’s own life. She describes what it was like growing up in the 1960s in the South where Jim Crow laws were in place. She writes about her experiences moving from state to state and explains how moving impacted her through the different stages of her life.

Locomotion by Jacqueline Woodson (grades 5-7)

Lonnie Collins Motions (nickname Locomotion) has been put in the foster system and separated from his younger sister. Full of anger, Lonnie acts out. A teacher introduces poetry as an outlet for his emotions, and it’s exactly what Lonnie needs.

A Time to Dance by Padma Venkatraman (grades 6-12)

Veda is a dance prodigy in India, and her entire life has revolved around it. When an accident leaves her with a prosthetic leg, Veda can’t accept a life without dance. She goes back to the basics and pursues dancing with all her might.

The beauty of poetry is that it doesn’t have to have a singular meaning. The reader doesn’t have to come to the same conclusion as the poet intended. The poet provides the story, the structure, and the vocabulary. It is up to the reader to take these components and find what the metaphors mean to them. The expansion of poetry into novels written in verse opens doors for readers to explore word choice and literary devices in a way that only poetry can provide. Through reading and discussing poetry, students can reflect on the value of language usage, as well as how it impacts their views on the world and themselves.

Supplemental Materials for Teachers

Acevedo, E. (2018). The poet X . HarperTeen.

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6 (3). https://scenicregional.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Mirrors-Windows-and-Sliding-Glass-Doors.pdf

Cambria, J., & Guthrie, J. (2010). Motivating and engaging students in reading. The NERA Journal , 46 (1) . https://webcapp.ccsu.edu/u/faculty/TurnerJ/NERA-V46-N1-2010.pdf#page=22

Frost, Robert. (1931) Education by poetry: A meditative monologue. Amherst Graduates Quarterly, 78 (2), 75,85.

Kamil, M. L., Borman, G. D., Dole, J., Kral, C. C., Salinger, T., & Torgesen, J. (2008). Improving adolescent literacy: Effective classroom and intervention practices: A practice guide (NCEE 2008-4027). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc

Nichols, W. D., Rasinski, T. V., Rupley, W. H., Kellogg, R. A., & Paige, D. D. (2018). Why poetry for reading instruction? Because it works! International Literacy Association , 72 (3), 389-397. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1734

Venkatraman, P. (2014). A time to dance. Nancy Paulsen Books.

- book choice

- book recommendations

- graphic novels

- independent reading

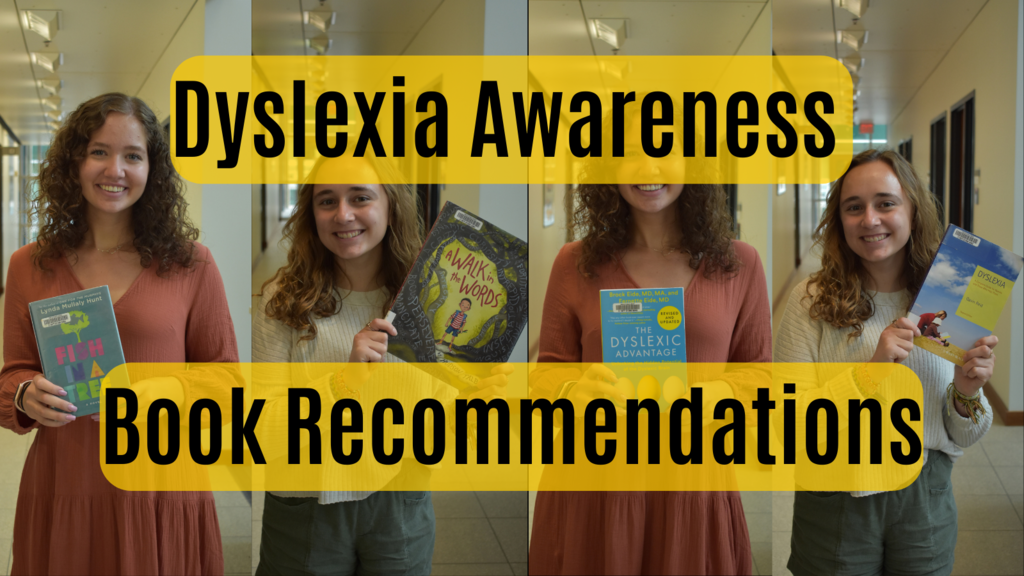

Book Recommendations About and for Children With Dyslexia and Their Caregivers

Celebrating Students’ Identities and Experiences With Culturally Relevant Texts

All You Need Is a Book: Our Favorite Children’s Literature

- Free writing courses

- Famous poetry classics

- Forums: Poet's • Suggestions

- My active groups see all

- Trade comments

- Print publishing

- Rate comments

- Recent views

- Membership plan

- Contact us + HELP

Poems / Critical thinking Poems - The best poetry on the web

Newest critical-thinking poems.

Perspective Deceptions

What Is Life Anyway?

Soydevs Destroyed Epic Style by Based Cooking (Not Clickbait)

Browse Categories

- Send Message

- Open Profile in New Window

- World Literatures

The Pedagogical Potential of Poems: Integrating Poetry in English Language Teaching

- ECT Excellencia Global Academy Foundation, Inc.

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Ahmad Arif Burhanuddin As Sholihin

- Adam Adzani

- Akmalus Salam

- Wahyu Indah Mala Rohmana

- Nury Mayerly Hoyos Hoyos

- Diego Sebastian Mayoral Anacona

- Gui Ke Ning

- Hanita Hanim Ismail

- Sharon Calibuso Toquero

- Femarie M Capistrano

- Janice Salinas

- Samina Sarwat

- Mobin Asghar

- Asma Manzoor

- Abdul Shakoor

- Natasha Kokab

- Marsha H. Malbas

- Jayson R. Miñoza

- Mark Kevin A. Angtud

- John Francis P. Book

- Annabelle R. Rabillas

- Ronnie E. Pasigui

- Francisca T. Uy

- Katrine S. Padilla

- Fedelyn S. Yorong

- July Grace A. Merabedes

- Shelley Dulsky

- Marsha Heyrosa-Malbas

- Se P. Villar

- Trinidad P Evangelista

- Nove Anne P Alestre

- Vidya Mandarani

- Ahmad Munir

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Cultivating Critical Thinking in Literature Classroom Through Poetry

Journal of Education Culture and Society

Aim. The development of learners' CT is considered to be one of the most important skills in today’s fast pacing world. It has also been regarded as the mainstay of and an important component of literature teaching. However, this is one of those areas that was overlooked mainly in eastern culture in general and in the EFL classrooms in particular. Methods. To this end, to foster learners' critical thinking skills, a poetry program was specifically designed to draw learners’ attention towards the significance of CT. Through a case study approach, a poetry program with a focus on culture-specific information was incorporated into the course. Four female students were engaged in a number of tasks in which they gradually learned to think critically through reflecting on and evaluating the assigned poems. A checklist was generated and used to observe and rate students’ CT before and after the intervention through teacher diaries. Results and conclusion. Analysis of the cas...

Related Papers

JEES (Journal of English Educators Society)

fithriyah abida

Teaching a language has become a challenging task for the teachers to train and to teach language for their students. In present time, the ability to master a language is vital for a language is a powerful means of communicating. Most of us will not focus on the language present in the literature part because our mind sets only towards the grammar. This has made both the teacher and students to ignore the literature part and made them to focus only on grammatical part to learn language. The urge behind using literary works in the teaching a language is to argue that the current attempts to implant literary works to the teaching of a language definitely develop students’ critical thinking in such a way that help them to easily master a particular language. Learning literary works in a classroom not only make the students learn about a story but also study how the language are structured and how its structured bring a great difference in meaning. Through a literary works student sees...

I Gusti Ayu Gde sosiowati

Richards (2006) states that the purpose of learning language is to master the communicative competence, meaning that by the end of the leaming process, the students should be able to produce proper language in any genre and in any situation. However, that competence alone, without accompanied by the ability to perform critical thinking will end in the conversation talking about explicit information only. It can not be denied that understanding the implicit infbrmation r'vill be challenging and making the conversation interesting. Halpern (cited on l5 March 2015) states that critical thinking refers to the use of cognitive skills or strategies that increase the probability of a desirable outcome. It is the kind of thinking which is involved in solving problems- formulating inferences, calculating likelihoods, and making decisions.The purpose of this article is to show that literary work can be used to develop critical thinking and at the same time is able to improve the students&...

International Journal of Linguistics

iman alizadeh

Advances in social science, education and humanities research

Vera Syamsi

Advances in Language and Literary Studies

Jayakaran Mukundan

Stefanie Fowler

Elahe Khorasani

Judith Langer

Jurnal Ilmiah Bina Bahasa

Neisya Neisya

This study investigated the improvement of students literary analysis by using taxonomy Blooms critical thinking questions. Action research was conducted for this research to the sixth semester students of English literature study program at Universitas Bina Darma. They are 5 male students and 10 female students. The action research was conducted for 12 meetings. On the first cycle, it consisted planning, action, observation and reflection. The assesment for the success criteria scored from a literary analysis rubric with scale poor, fair and good. During this cycle, the students only achieved mostly to poor level of literary analysis in their writing. After doing some revision and evaluation on the second cycle, it also included, replanning, action, observation and the reflection. In this cycle, the result shows most students succeeded to improve their literary analysis to the fair level and 2 students were in good level with some notes. Although, some students perhaps need more ti...

Cross-cultural Communication

maisoun Abujodah

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About The Review of English Studies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Books for Review

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Jessica Lewis Luck . Poetics of Cognition: Thinking through Experimental Poems

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Nikki Skillman, Jessica Lewis Luck . Poetics of Cognition: Thinking through Experimental Poems , The Review of English Studies , 2024;, hgae041, https://doi.org/10.1093/res/hgae041

- Permissions Icon Permissions

‘If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?’ Emily Dickinson’s eccentric account of aesthetic arrest may describe what reading poetry feels like to her ‘physically’, but her existential chill and exposed brain also resonate as metaphors for states of mind—for the pleasurable discomfort and radical openness poetry often provokes in readers. Such elusive states are the subject of Jessica Lewis Luck’s The Poetics of Cognition: Thinking through Experimental Poems , which brings the challenge of describing the ‘material effects’ of poetry, as Luck puts it, to contemporary experiments in poetic form. The poems she studies, by poets ranging from Aram Saroyan and Larry Eigner to Tracie Morris and Lisa Jarnot, are designed to blow our minds: to pull apart the self- and world-making system of language, to enchant with iconoclastic mischief, to make the status quo seem not only strange, but freshly pliable and ripe for reform. What if an intrepid literary critic could to peer into your head and observe your brain on such poetry? With the cutting-edge descriptive instruments of cognitive scientists at hand, might she prove that poems—particularly radical poems—alter how we think for the better?

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| June 2024 | 9 |

| July 2024 | 11 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1471-6968

- Print ISSN 0034-6551

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Professional development

- Promoting 21st century skills

Critical Material For Critical Thinking

To me, critical thinking has always been about looking at something, whether a poem, a piece of art, or an idea, appreciating what is good about it, and questioning what I felt was not good about it, while trying to keep an open mind to the opinions of others, but maintaining my own independent opinion. This is something I encourage my students to do; praising independent thought and ideas that are new, even if strange. Also to me, critical thinking is something that requires creativity. But what is creativity? Hodges (2005:53-54) outlines the following as features of creativity:

1. Using imagination

2. Pursuing purposes, aiming to come to a particular finishing point

3. Being original

4. Judging value, i.e. assessing quality, coming up with one’s own ideas, as well as looking at their ideas and those of others in a critical light.

To this, I would add the following in my lessons to encourage critical thinking:

5. Provoking thought, rather than just checking language comprehension, language use and practicing skills.

6. Exposing students to a variety of literature, art and music.

Keeping these 6 elements in mind, below I explore some of the practical possibilities they open up in every day lessons, looking at poems, comics and music, all of which I have experimented with in class and used as platforms to encourage creativity in my students and make learning more fun and diverse. For each, I have included question types I would ask to provoke thought, force students to be imaginative and think creatively and critically.

Poems are a great way to learn language, especially with higher levels. They provide examples of various grammar structures and are rich in vocabulary. They also provide examples of punctuation use, but most importantly, they provide a lot of food for thought. Working with poems, students can explore various themes, look at rhymes, and tap into their feelings and emotions through poetic expression. In class, students can look at shape poems and create their own around an object of interest to them. They could look at poems from various periods of history and from various cultures, identifying elements of politics, or tradition. They could explore deeper meanings and try to read the mind of the poet, each providing their own opinions on what the writer was thinking and why they think so. Another idea might be listening to a poem and drawing the images that come to mind or writing down one’s feelings as they listen to a poem. A good example of this kind of activity might be This Is Just to Say by W C Williams, with which students might pick on feelings of enjoyment, followed by guilt and the seeking of forgiveness. They may also be able to relate to the speaker in the poem, as he describes a normal incident that could happen to anyone.

Questions: How does the shape affect the poem? Do you think the shape means something? Why did you choose that particular shape? Which poem do you identify with and why? What is the poet trying to say? Which lines in the poems tell you this? Do you agree with the poet? Has something like this happened to you? How did it make you feel?

Comics present students with a more colourful and friendly way to do some reading. They provide spoken language in context and expose students to a variety of grammar structures. Their stories and the characters in them are also quite popular with the younger generation who have seen them in movies or animations growing up. The most famous of these are Batman, Spiderman and other well – known superheroes. Working with comics, students can be presented a problem in society that needs fixing, such as bullying in the neighbourhood, or a large company destroying the environment. Students can identify good guys and bad guys, creating a plot around the story of a superhero. This would require the creation of a superhero, identifying his or her super powers, costume details and other information about them. They could then illustrate and write their comic. It seems like a large project to work on and may take some time but scaffolding and breaking it up into a few focused lessons will make it easier for everyone.

Questions: Which character do you like most in this comic, and why? What are my superhero’s options in this scenario? What are the powers that would be most useful to my superhero? Whose superhero do you like the most in the class? Why? What do you like about this plot? What would you have written differently in this comic?

Music Music helps people relax. It provides common ground for discussion and sharing interests. It brings people and cultures together. It also provides language, much the same way as poetry or comics do and allows students to explore emotions and themes in a language context. As such, it has its own place in the classroom, especially with the youth. In class, students could listen to songs they like, sharing their favourite ones and talking about the kind of music they like and why. Students could take lyrics from songs to inspire their own songs, creating one of their own and sharing with or performing for the class.

Questions: Which one did you like better, and why? What was good about the first song? What did you not like in the second song? What do you think of the singer as an artist? Which artists would you like to see do a song like this? Which lines in the poem are your own? How can I change the ones I stole to make them mine? What can I do to make the rhythm better?

References: Hodges, 2005. Creativity in Education. University of Cambridge. pp. 53 – 54

Critical thinking

- Log in or register to post comments

Lovely ideas Zahra. I

Research and insight

Browse fascinating case studies, research papers, publications and books by researchers and ELT experts from around the world.

See our publications, research and insight

- Annual Emerging Poets Slam 2023

- Poems About the Pandemic Generation Slam

- Slam on AI - Programs or Poems?

- Slam on Gun Control

- Poet Leaderboard

- Poetry Genome

- What are groups?

- Browse groups

- All actions

- Find a local poetry group

- Top Poetry Commenters

- AI Poetry Feedback

- Poetry Tips

- Poetry Terms

- Why Write a Poem

- Scholarship Winners

Critical Thinking

All I need is critical thinking

The power to discern,

The ability to learn

From the issues of everyday life

Solving problems by linking

To the knowledge of previous strife.

Login or register to post a comment.

Additional Resources

Get ai feedback on your poem.

Interested in feedback on your poem? Try our AI Feedback tool .

If You Need Support

If you ever need help or support, we trust CrisisTextline.org for people dealing with depression . Text HOME to 741741

- Join 230,000+ POWER POETS!

- Request new password

This website uses cookies to give you the best possible experience. By continuing to use this site we'll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies as per our cookie policy.

Creative writing at a critical age: Using poetry to stimulate creativity and embrace writing skills in teenage classes

By Keely Laufer

A class creative writing project using authentic materials can be created to challenge, train and develop general writing skills and teach a variety of sub-skills to higher level teenagers, such as creative and critical thinking and editing skills. Creativity involves imaginative, innovative and abstract thinking, and critical thinking involves logic and reasoning, questioning, analysis, assessment and evaluation. When carried out as a long-term class poetry project, these skills combined can help teenagers to express their opinions, attitudes, emotions and sense of self in L2 sooner.

Coursebooks for teenagers do not always provide much opportunity for integrating creative and critical thinking and writing skills into language learning to help students achieve higher levels of self-expression, not only needed for FCE and beyond, but to motivate teenagers by making language learning an enjoyable experience. As Michael Lewis asserts, ‘Syllabuses are directed towards language teaching, but ultimately it is not languages which are being taught, but people. People want and need to express emotion and attitude’ (see note 1). My aim was to help my BKC ‘English in Mind 4’ students, aged between 13-15, develop their creative and critical thinking and writing skills, while raising general student motivation and enthusiasm levels by making the writing process fun, in the context of working towards the FCE course.

Why conduct a long-term poetry project with teenagers?

Teenagers are at a critical stage in their development where they are generally emotional and creative in their thinking and self-expression, yet are also developing the ability to think critically using logic and reason. Therefore, teenagers respond well to activities that have a fundamental expressive, yet critical purpose. As Gordon Lewis confirms, ‘When an activity is designed so that it addresses both types of thinking [creative and critical], students strengthen valuable academic skills and stimulate their curiosity.’ (see note 2). When well-exercised over a period of time, creative and critical writing activities centred around poetry can help to promote the mature development of writing skills, even for students who are not initially as interested in poetry, providing that poems are tailored to be thematically relevant to students’ interests.

Why poetry?

Poetry as an art form exploits language and form in its entirety: everything in a poem has meaning. The beauty of poetry analysis is that interpretations and creative ideas cannot be incorrect, providing that they are shaped from logical consideration of the text and are backed up by textual evidence. This gives students the freedom of exploration, autonomy and confidence in their writing. Poems are also usually shorter than prose and can therefore be revisited many times for the discovery of new layers of meaning.

Procedure for analysing a poem and writing a critical essay:

- Build interest in the central image or theme of the poem with pictures (e.g. a toad). OR In pairs, answer general boarded questions related to the central image or theme (not necessarily directly related to the poem).

- Present the poem on paper with a glossary.

- Teacher reads the poem while students underline any other words that they do not understand. Some students may prefer to take a flipped-classroom approach by taking the poem home to look up any unknown vocabulary. A recording of the poet reading the poem could also be played if available.

- Clarify any difficult vocabulary.

- Brainstorm ideas individually: what could the poem be about?

- Pair-check ideas.

- Students add ideas to the boarded class mind map.

- Class discussion of the poem by ‘chunk analysis’ (stanza by stanza), in relation to the set questions pre-folded back behind the poem (see note 3). These questions are answered to form the critical essay. Teacher boards students’ ideas during the discussion.

- Students write their essay in class or at home, depending on the plan. Some students prefer to take their time writing at home and others prefer to work in class under a time constraint.

- Illustrate and present individual or group posters based on the whole or on a part of the poem. Students or groups receive the poem cut-up into sense-logical chunks and can choose a chunk to focus their illustration on. These illustrations can then be used to further develop speaking skills when presenting their own or each other’s posters.

How students approached writing their own poems:

The students’ first poem was about their most meaningful possession, as a result of not wanting to do an unmotivating writing task in the coursebook. For the second poem, students chose a mutual object of desire and all wrote a poem about the same object. In the following lesson, their challenge was to merge these poems into one collective class poem. Students collaborated to think of a first and last line to add to each other’s poems. I supported as a mediator and helped where needed. This process taught students to appreciate, take into consideration and learn from each other’s work, which also helped develop their speaking, listening, negotiation and general social skills.

Error Correction and Feedback Process

When marking the essays, I prioritised corrections to major grammar, syntax and spelling errors, which made applying corrections achievable between essays. I wrote each student’s top three strengths and corrections at the bottom of their essays and encouraged them to use the list from the previous essay when writing the new essay. When giving class feedback after handing back an essay and before writing a new essay in class, I elicited and boarded the top three collective strengths and weaknesses, as a reminder while students wrote. Then, they proofread their essays against their personal and collective lists. Students can also read each other’s work and give feedback on specific positive achievements and areas for improvement, in relation to content, communicative achievement, organisation and language.

Arsenii was the youngest student in the class, yet his speaking fluency and general writing improved the most dramatically. At the beginning of the project he struggled to write a few sentences about the poems, and by the end, he started coming up with his own complex ideas that he pushed himself to develop, backed up by textual evidence. This creative project gave Arsenii the opportunity to realise his creative potential and trained him to be able to organise and express his ideas in detail.

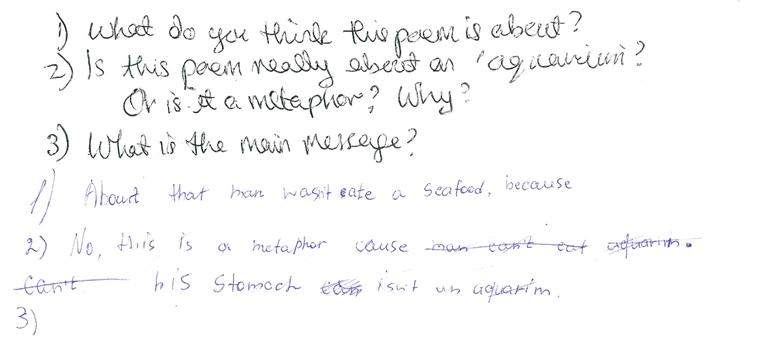

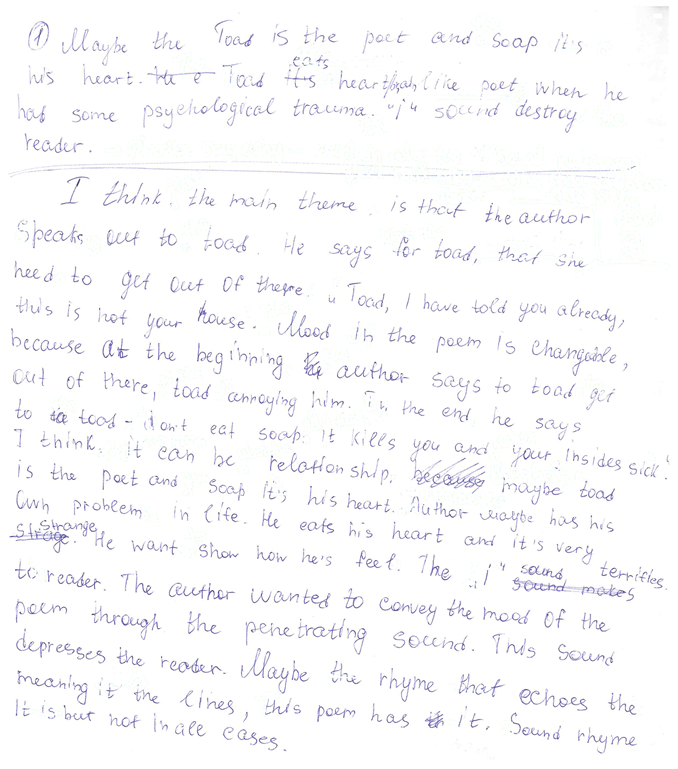

Earlier in the project:

Middle of the project:

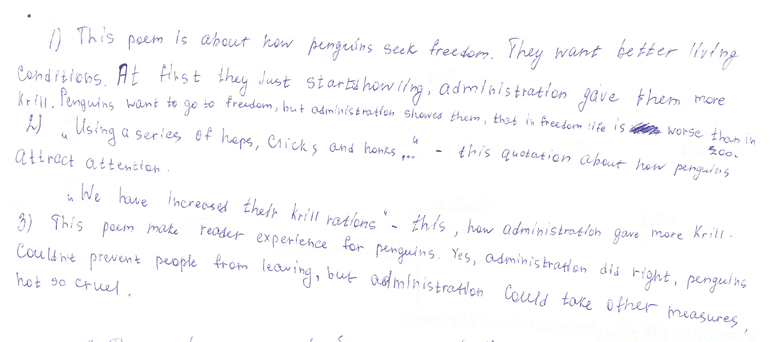

1) What is this poem about?

2) Is this poem really about penguins, or are they a metaphor and why?

3) How does this poem make the reader feel?

Later in the project:

Key improvements from each student (Names have been changed):

Boris - learnt to form his own opinions about a text and express them in his writing with increased detail. Dasha - learnt to organise her ideas clearly, and explore and expand upon them more creatively and in greater depth (see note 4). Lara - learnt to develop her own opinions about a text in greater detail and express spoken and written opinions with more ease and fluency, using sophisticated grammar structures and vocabulary. Lilia - learnt to organise her stream of free-flowing ideas in a structured way.

Samples of portfolio illustrations based on ‘Toad’:

(own image – shared with permission of the author)

By the end of this poetry project, my aim for students to develop creative and critical thinking and editing skills were met. This was demonstrated through the students’ ability to analyse poetry through the application of imaginative, innovative and abstract thinking, yet using logical thinking and reasoning, assessment and evaluation in their essays, class discussions and illustrations of poetry. Not only did creative and critical thinking skills help students to improve their general writing and editing skills, but their speaking, listening, negotiation and general social skills in class. Students were able to express their emotions, opinions and attitudes with increased written and spoken fluency through this poetry project, as knowing that their interpretations and creative ideas could not be incorrect if backed-up by textual evidence, gave students the confidence and freedom to explore themselves through L2.

My other equally fundamental aim to raise general student motivation and enthusiasm levels by making the writing process fun, in the context of preparing for the FCE course, was also met. Not only is the success of this project measurable by the students’ significantly improved writing skills, but also by the students’ level of engagement with the project, their collective pride and initiative shown, which was even greater than expected. Students asked for a new poem to analyse and write about at home after class tests, when given the option of no homework, and some students also illustrated poems to decorate our class portfolio, without being asked.

A long-term class poetry project can be used to improve targeted skills to meet individual and group needs, spice up a coursebook and course content, build a creative classroom climate that can strengthen overall rapport and foster a sense of community spirit. This poetry project proves Lewis’s statement that ‘Literature is a rich source of opinion, attitude and emotion, and literary texts can be exploited in different ways to encourage learners to express their own opinions, attitudes and emotions (p. 163).

Appendix 1:

- What is the theme? Happiness?

- What is the mood of the poem? What words or phrases create this mood?

- Who is the poem about and what is the relationship between the subject and the speaker (poetic voice)?

- Think about the way the poem looks on the page: the shape, where the lines end, line length, etc. How does this influence the meaning?

- Notice the repetitive ‘i’ sound. How does this make you feel as a reader? In what ways can these sound patterns contribute to the meaning?

- Is there any kind of rhyme in this poem, even if not obvious? Think about sound patterns aside from the ‘i’ sound in question 5.

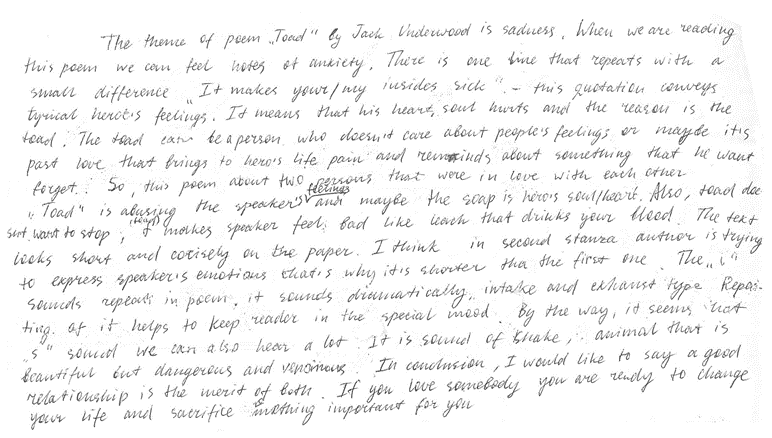

Appendix 2 - Dasha's essay:

Appendix 3:

Extra activities:.

1. Create different types of exercises from each poem:

- Use fewer poems to see how many exercises can be created from each poem.

- A cut-up version of the poem could be given out before being shown in its original form, for students to reorder in groups according to what they think the logical progression should be. Then, in different groups discuss their reasoning and how the meaning of the poem might be different between groups, depending on how it has been reordered. Individuals or groups could take a photograph of their version of the poem and revisit it once they are familiar with the original form, for the purpose of comparing and contrasting any similarities, differences or changes in meaning.

- Assigning different parts of the poem to different individuals or groups to read aloud or write about.

- Writing their own poem in response to the whole poem, or to an area of interest within the poem.

- Creating a performance of the poem (possibly with costumes and props).

- Rewriting exercises (changing or adding to a poem): how would they rewrite the poem to express the same message? Would they use the same language (further explore or play with pre-existing language, i.e. wordplay), form (shape, line length, enjambment, stanza order, meter, rhyme), sound patterns, imagery, tone, genre, context, point of view (poetic voice or another subject’s)? What would they ‘keep, change, add, remove’? Why? OR Rewrite the poem using the same key images to express a personal or social problem that affects teenagers today, by exploring the same poetic techniques in a different way or using different poetic techniques.

- Language awareness prediction exercises: remove words and encourage students to consider the overall message by using surrounding language and tone, in order to work out the words or choose their own words to fill in the gaps. This task would be useful practice for FCE Use of English.

2. Focus on editing skills:

- Read and make suggestions about each other’s work using purposeful guidelines set by the teacher.

- As the project progresses, introduce word counts to encourage shorter and more concise essays, as part of exam preparation technique training, for the purpose of focusing in more depth on a key idea and considering language quality.

- Create exercises using students’ essays: detailed expansion of a word count or to work on paraphrasing skills and reducing a word count.

3. Explore what is not in the poem: what it might mean if there is no clear set meter or rhyme, instead of it being another element less to consider, or dismissing the poem for being of a contemporary genre.

4. Read and engage with reviews of the poem or poetry collection in which the poem appears: after students have explored their own ideas through the essay writing process, they could read a review for the purpose of being exposed to other interpretations of the same poem and to write an engaged response. There could be an example of a positive and negative review, to which students can write an opinion piece to support or argue against the reviewer’s opinion. This is also extra exposure to other authentic materials of different writing styles in relation to the class poem.

5. Focus on grammar and collocations: teaching grammar in a creative context or teaching grammar creatively, such as by using the poem to teach or revise a grammar topic from the coursebook.

1 Michael, Lewis, ‘Classroom Reports: Using Poems and Songs in a Lexical Framework’, in Implementing the Lexical Approach: Putting Theory into Practice (Hove: Language Teaching Publications, 1997), p. 163.

2 Gordon, Lewis, ‘Chapter 2: Creative and Critical Thinking Tasks’, in Resource books for teachers: Teenagers, ed. by Alan Maley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), p.43.

3 See ‘Appendix 1’ for the questions written for Jack Underwood’s poem ‘Toad’.

4 See ‘Appendix 2’ for Dasha’s essay answering the questions in response to ‘Appendix 1’.

|

Lewis, Gordon, ‘Chapter 2: Creative and Critical Thinking Tasks’, in Resource books for teachers: Teenagers, ed. by Alan Maley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 43-77 Lewis, Michael, ‘Classroom Reports: Using Poems and Songs in a Lexical Framework’, in Implementing the Lexical Approach: Putting Theory into Practice (Hove: Language Teaching Publications, 1997), pp. 162-172 Underwood, Jack, ‘Toad’ in Happiness (London: Faber & Faber, 2015) p. 12

Poetry Foundation - Poetry International - Poetry Society - National Poetry Library -

Poetry Wales - Magma Poetry -

Falley, Megan, and Andrea Gibson, How Poetry Can Change Your Heart (Chronicle Books: San Francisco, 2019)

BBC Bitesize GCSE WJEC: Writing and Analysing Poetry - |

Author's bio: Keely Laufer finished her BA in English Literature and Creative Writing at Aberystwyth University in West Wales, followed by an MA in Creative Writing: Poetry, at the University of East Anglia in England. She then completed her Cambridge CELTA at International House London, followed by specialisation training at International House Moscow: 'IH Certificate in Teaching Very Young Learners, 2-7yrs', 'IH Certificate in Teaching Young Learners and Teenagers (IHCYLT)' and the 'IH Certificate in Developing literacy skills with primary and pre-primary learners'. She is particularly interested in stimulating a creative classroom climate through storytelling and craft projects for VYL, literacy projects for YL, and through running poetry courses to develop critical and creative writing skills in higher level teenagers.

Critical Thinking Is All About “Connecting the Dots”

Why memory is the missing piece in teaching critical thinking..

Updated July 23, 2024 | Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer

- Critical thinking requires us to simultaneously analyze and interpret different pieces of information.

- To effectively interpret information, one must first be able to remember it.

- With technology reducing our memory skills, we must work on strengthening them.

I have a couple of questions for my regular (or semi-regular) readers, touching on a topic I’ve discussed many times on this blog. When it comes to power, persuasion , and influence, why is critical thinking so crucial? Alternatively, what are some common traps and pitfalls for those who prioritize critical thinking? It's not necessary that you go in to great detail—just any vague or general information that comes to mind will do.

Great! Regardless of whether you recalled anything specific, the key is you made the effort to remember something. Like many questions I pose here, the real purpose is to illustrate a point. If you aim to be influential and persuasive—i.e., successful—in both work and life, you must be proficient in critical thinking. To achieve this proficiency, you need to cultivate and exercise your memory , a skill that is increasingly at risk in a technology-saturated age.

Remembering Is the Foundation of Knowing

Learning and remembering something are often discussed as if they are two separate processes, but they are inextricably linked . Consider this: Everything you know now is something you once had to learn, from basic facts to complex knowledge and skills. Retaining this information as actual knowledge, rather than fleeting stimuli, depends entirely on memory. Without memory, there is no knowledge. Consequently, there can be no critical thinking, as it relies on prior knowledge, which in turn relies on memory.

Students sometimes tell me that they want to learn how to be good critical thinkers but complain about having to “memorize stuff.” On these occasions I will often say, in a playfully teasing manner, “What I hear you saying is that you're bothered by having to remember stuff.” This usually helps them see how silly and unreasonable it is to complain about memorizing information, as there isn’t a single course in existence that doesn’t require remembering something . The ability to remember is at the core of critical thinking, and I often use the simple visual demonstration that follows to illustrate this point.

Collecting Dots and Connecting the Dots

Benjamin Bloom, an educational psychologist, developed a model known as the “Taxonomy of Learning.” Originally intended for educational psychology, this model also highlights why memory is the foundation of critical thinking—or any kind of thinking at all.

Humans are creatures of interpretation, constantly processing the information we perceive. This ability has made us the scientists, inventors, and artists that we are today. To interpret information, however, we must first remember it—not all information, obviously, as that’s impossible. Thanks to technology (which we’ll get to momentarily) we have vast amounts of information potentially at our fingertips. But how do you know what information to look up in a given situation? To know where to start and avoid endlessly searching irrelevant data, you need to remember enough of the right kind of information.

Think of a crime movie where an investigator, while reviewing evidence, suddenly has an epiphany and rushes off to confirm their hunch. These scenes illustrate that while the investigator needs more information, they remember enough to know what to search for.

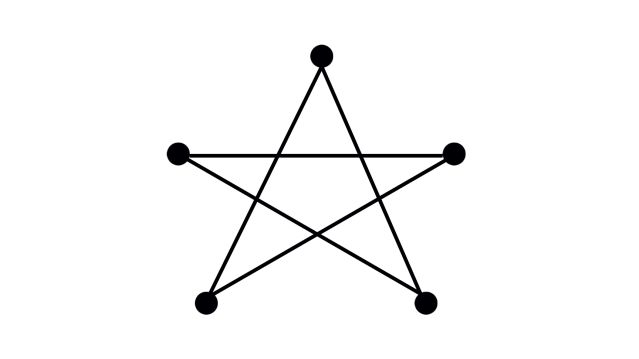

Here’s a visual demonstration I use in class to help my students understand. Imagine you have pieces of information represented as five dots:

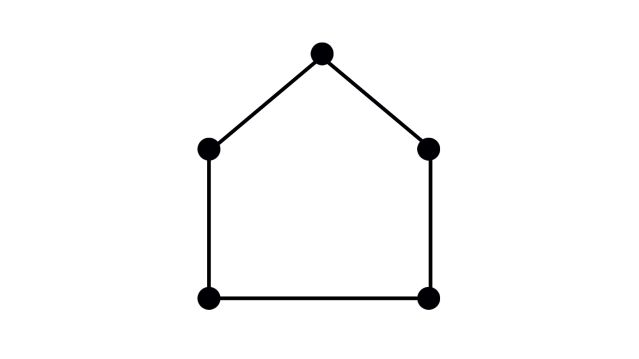

Now let’s say that any coherent shape or picture you can draw using these dots is an interpretation of the information. When examined together, what might these five dots mean? Here’s one way to connect the dots.

What does this shape represent? Many people will quickly say it’s a house, a common and reasonable interpretation. But not everyone sees it as a house. Some might say it’s the home plate used in baseball. Even when people connect the dots (i.e., interpret a cluster of information) the same way using the same lines, they don’t necessarily interpret the picture the same way. The situation becomes more complex when people connect the dots differently, creating a completely different shape or picture.

Now, having connected the dots differently, instead of a house, we have a star. Or at least some would consider it a star; others might say it’s an occult or magic symbol—these are all very different interpretations. This shows that with the same pieces of information, people can “connect the dots” differently, and even when they connect them the same way, they see different things.

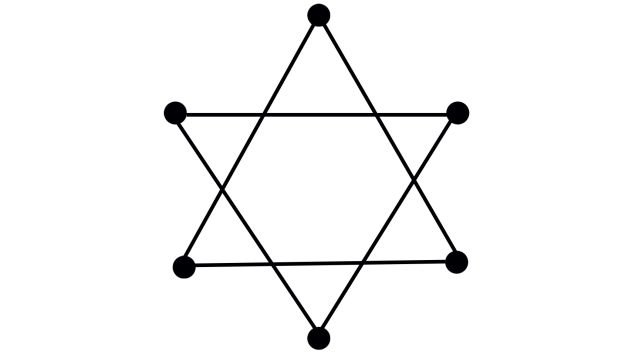

Now what happens when additional information is added or an alleged “missing dot” is perceived by others?

With just one additional dot, what could have previously been interpreted as a 5-pointed star can now be reasonably interpreted as the Star of David.

Finally, sometimes the additional information can lead to a completely different shape or image, resulting in a “eureka” moment of insight. What previously appeared as different types of stars now looks like a circle.

I use this classroom demonstration to illustrate how people can interpret the same objective information in highly subjective ways, creating different narratives for themselves and others. This is a crucial point to remember when aiming to influence or persuade others—i.e., the need to see things from their perspective. Additionally, this activity powerfully underscores the importance of “collecting dots”—that is, the importance of remembering crucial bits of information. Without enough such dots, you lack the basic information needed to form meaningful ideas. Without meaningful ideas, you can’t think critically, influence, or persuade. It’s as straightforward as that.

Memory in the Age of Omnipresent Technology

Why is it so crucial to recognize that memory is foundational to critical thinking, power, influence, and persuasion? Partly because this fact isn’t widely acknowledged—and it needs to be. Additionally, we live in an era where memory is under unprecedented assault. While technology allows us to achieve remarkable feats unimaginable to previous generations, it comes at a cost. One such cost is “digital-induced amnesia,” where our memory capabilities atrophy due to information overload and technology taking over many of the cognitive tasks we used to perform ourselves.

Memory doesn’t exist in isolation. It’s closely tied to traits like the ability to focus and pay attention . If you’re not paying attention, you can’t absorb the information that you want or need to remember. Unfortunately, technology also impacts our ability to focus , and this doesn’t even touch on the dramatic ways AI ’s explosive development might undermine our thinking skills .

This article won’t delve into specifics on improving focus and memory in an age of tech ubiquity. Fortunately, resources from Psychology Today can help with that. My goal here is to convince you why memory is so vital for anyone who wishes to be a critical thinker and a persuasive, influential person. Now you know. Whether you’ll remember or not...only time will tell.

Craig Barkacs, MBA, JD, is a professor of business law at the University of San Diego School of Business and a trial lawyer with three decades of experience as an attorney in high-profile cases.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire