- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Essay Film

Introduction, anthologies.

- Bibliographies

- Spectator Engagement

- Personal Documentary

- 1940s Watershed Years

- Chris Marker

- Alain Resnais

- Jean-Luc Godard

- Harun Farocki

- Latin American Cinema

- Installation and Exhibition

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Documentary Film

- Dziga Vertov

- Trinh T. Minh-ha

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Jacques Tati

- Media Materiality

- The Golden Girls

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Essay Film by Yelizaveta Moss LAST REVIEWED: 24 March 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 24 March 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0216

The term “essay film” has become increasingly used in film criticism to describe a self-reflective and self-referential documentary cinema that blurs the lines between fiction and nonfiction. Scholars unanimously agree that the first published use of the term was by Richter in 1940. Also uncontested is that Andre Bazin, in 1958, was the first to analyze a film, which was Marker’s Letter from Siberia (1958), according to the essay form. The French New Wave created a popularization of short essay films, and German New Cinema saw a resurgence in essay films due to a broad interest in examining German history. But beyond these origins of the term, scholars deviate on what exactly constitutes an essay film and how to categorize essay films. Generally, scholars fall into two camps: those who find a literary genealogy to the essay film and those who find a documentary genealogy to the essay film. The most commonly cited essay filmmakers are French and German: Marker, Resnais, Godard, and Farocki. These filmmakers are singled out for their breadth of essay film projects, as opposed to filmmakers who have made an essay film but who specialize in other genres. Though essay films have been and are being produced outside of the West, scholarship specifically addressing essay films focuses largely on France and Germany, although Solanas and Getino’s theory of “Third Cinema” and approval of certain French essay films has produced some essay film scholarship on Latin America. But the gap in scholarship on global essay film remains, with hope of being bridged by some forthcoming work. Since the term “essay film” is used so sparingly for specific films and filmmakers, the scholarship on essay film tends to take the form of single articles or chapters in either film theory or documentary anthologies and journals. Some recent scholarship has pointed out the evolutionary quality of essay films, emphasizing their ability to change form and style as a response to conventional filmmaking practices. The most recent scholarship and conference papers on essay film have shifted from an emphasis on literary essay to an emphasis on technology, arguing that essay film has the potential in the 21st century to present technology as self-conscious and self-reflexive of its role in art.

Both anthologies dedicated entirely to essay film have been published in order to fill gaps in essay film scholarship. Biemann 2003 brings the discussion of essay film into the digital age by explicitly resisting traditional German and French film and literary theory. Papazian and Eades 2016 also resists European theory by explicitly showcasing work on postcolonial and transnational essay film.

Biemann, Ursula, ed. Stuff It: The Video Essay in the Digital Age . New York: Springer, 2003.

This anthology positions Marker’s Sans Soleil (1983) as the originator of the post-structuralist essay film. In opposition to German and French film and literary theory, Biemann discusses video essays with respect to non-linear and non-logical movement of thought and a range of new media in Internet, digital imaging, and art installation. In its resistance to the French/German theory influence on essay film, this anthology makes a concerted effort to include other theoretical influences, such as transnationalism, postcolonialism, and globalization.

Papazian, Elizabeth, and Caroline Eades, eds. The Essay Film: Dialogue, Politics, Utopia . London: Wallflower, 2016.

This forthcoming anthology bridges several gaps in 21st-century essay film scholarship: non-Western cinemas, popular cinema, and digital media.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Cinema and Media Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Accounting, Motion Picture

- Action Cinema

- Advertising and Promotion

- African American Cinema

- African American Stars

- African Cinema

- AIDS in Film and Television

- Akerman, Chantal

- Allen, Woody

- Almodóvar, Pedro

- Altman, Robert

- American Cinema, 1895-1915

- American Cinema, 1939-1975

- American Cinema, 1976 to Present

- American Independent Cinema

- American Independent Cinema, Producers

- American Public Broadcasting

- Anderson, Wes

- Animals in Film and Media

- Animation and the Animated Film

- Arbuckle, Roscoe

- Architecture and Cinema

- Argentine Cinema

- Aronofsky, Darren

- Arzner, Dorothy

- Asian American Cinema

- Asian Television

- Astaire, Fred and Rogers, Ginger

- Audiences and Moviegoing Cultures

- Australian Cinema

- Authorship, Television

- Avant-Garde and Experimental Film

- Bachchan, Amitabh

- Battle of Algiers, The

- Battleship Potemkin, The

- Bazin, André

- Bergman, Ingmar

- Bernstein, Elmer

- Bertolucci, Bernardo

- Bigelow, Kathryn

- Birth of a Nation, The

- Blade Runner

- Blockbusters

- Bong, Joon Ho

- Brakhage, Stan

- Brando, Marlon

- Brazilian Cinema

- Breaking Bad

- Bresson, Robert

- British Cinema

- Broadcasting, Australian

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer

- Burnett, Charles

- Buñuel, Luis

- Cameron, James

- Campion, Jane

- Canadian Cinema

- Capra, Frank

- Carpenter, John

- Cassavetes, John

- Cavell, Stanley

- Chahine, Youssef

- Chan, Jackie

- Chaplin, Charles

- Children in Film

- Chinese Cinema

- Cinecittà Studios

- Cinema and Media Industries, Creative Labor in

- Cinema and the Visual Arts

- Cinematography and Cinematographers

- Citizen Kane

- City in Film, The

- Cocteau, Jean

- Coen Brothers, The

- Colonial Educational Film

- Comedy, Film

- Comedy, Television

- Comics, Film, and Media

- Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI)

- Copland, Aaron

- Coppola, Francis Ford

- Copyright and Piracy

- Corman, Roger

- Costume and Fashion

- Cronenberg, David

- Cuban Cinema

- Cult Cinema

- Dance and Film

- de Oliveira, Manoel

- Dean, James

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Denis, Claire

- Deren, Maya

- Design, Art, Set, and Production

- Detective Films

- Dietrich, Marlene

- Digital Media and Convergence Culture

- Disney, Walt

- Downton Abbey

- Dr. Strangelove

- Dreyer, Carl Theodor

- Eastern European Television

- Eastwood, Clint

- Eisenstein, Sergei

- Elfman, Danny

- Ethnographic Film

- European Television

- Exhibition and Distribution

- Exploitation Film

- Fairbanks, Douglas

- Fan Studies

- Fellini, Federico

- Film Aesthetics

- Film and Literature

- Film Guilds and Unions

- Film, Historical

- Film Preservation and Restoration

- Film Theory and Criticism, Science Fiction

- Film Theory Before 1945

- Film Theory, Psychoanalytic

- Finance Film, The

- French Cinema

- Game of Thrones

- Gance, Abel

- Gangster Films

- Garbo, Greta

- Garland, Judy

- German Cinema

- Gilliam, Terry

- Global Television Industry

- Godard, Jean-Luc

- Godfather Trilogy, The

- Greek Cinema

- Griffith, D.W.

- Hammett, Dashiell

- Haneke, Michael

- Hawks, Howard

- Haynes, Todd

- Hepburn, Katharine

- Herrmann, Bernard

- Herzog, Werner

- Hindi Cinema, Popular

- Hitchcock, Alfred

- Hollywood Studios

- Holocaust Cinema

- Hong Kong Cinema

- Horror-Comedy

- Hsiao-Hsien, Hou

- Hungarian Cinema

- Icelandic Cinema

- Immigration and Cinema

- Indigenous Media

- Industrial, Educational, and Instructional Television and ...

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers

- Iranian Cinema

- Irish Cinema

- Israeli Cinema

- It Happened One Night

- Italian Americans in Cinema and Media

- Italian Cinema

- Japanese Cinema

- Jazz Singer, The

- Jews in American Cinema and Media

- Keaton, Buster

- Kitano, Takeshi

- Korean Cinema

- Kracauer, Siegfried

- Kubrick, Stanley

- Lang, Fritz

- Latina/o Americans in Film and Television

- Lee, Chang-dong

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Cin...

- Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The

- Los Angeles and Cinema

- Lubitsch, Ernst

- Lumet, Sidney

- Lupino, Ida

- Lynch, David

- Marker, Chris

- Martel, Lucrecia

- Masculinity in Film

- Media, Community

- Media Ecology

- Memory and the Flashback in Cinema

- Metz, Christian

- Mexican Film

- Micheaux, Oscar

- Ming-liang, Tsai

- Minnelli, Vincente

- Miyazaki, Hayao

- Méliès, Georges

- Modernism and Film

- Monroe, Marilyn

- Mészáros, Márta

- Music and Cinema, Classical Hollywood

- Music and Cinema, Global Practices

- Music, Television

- Music Video

- Musicals on Television

- Native Americans

- New Media Art

- New Media Policy

- New Media Theory

- New York City and Cinema

- New Zealand Cinema

- Opera and Film

- Ophuls, Max

- Orphan Films

- Oshima, Nagisa

- Ozu, Yasujiro

- Panh, Rithy

- Pasolini, Pier Paolo

- Passion of Joan of Arc, The

- Peckinpah, Sam

- Philosophy and Film

- Photography and Cinema

- Pickford, Mary

- Planet of the Apes

- Poems, Novels, and Plays About Film

- Poitier, Sidney

- Polanski, Roman

- Polish Cinema

- Politics, Hollywood and

- Pop, Blues, and Jazz in Film

- Pornography

- Postcolonial Theory in Film

- Potter, Sally

- Prime Time Drama

- Queer Television

- Queer Theory

- Race and Cinema

- Radio and Sound Studies

- Ray, Nicholas

- Ray, Satyajit

- Reality Television

- Reenactment in Cinema and Media

- Regulation, Television

- Religion and Film

- Remakes, Sequels and Prequels

- Renoir, Jean

- Resnais, Alain

- Romanian Cinema

- Romantic Comedy, American

- Rossellini, Roberto

- Russian Cinema

- Saturday Night Live

- Scandinavian Cinema

- Scorsese, Martin

- Scott, Ridley

- Searchers, The

- Sennett, Mack

- Sesame Street

- Shakespeare on Film

- Silent Film

- Simpsons, The

- Singin' in the Rain

- Sirk, Douglas

- Soap Operas

- Social Class

- Social Media

- Social Problem Films

- Soderbergh, Steven

- Sound Design, Film

- Sound, Film

- Spanish Cinema

- Spanish-Language Television

- Spielberg, Steven

- Sports and Media

- Sports in Film

- Stand-Up Comedians

- Stop-Motion Animation

- Streaming Television

- Sturges, Preston

- Surrealism and Film

- Taiwanese Cinema

- Tarantino, Quentin

- Tarkovsky, Andrei

- Television Audiences

- Television Celebrity

- Television, History of

- Television Industry, American

- Theater and Film

- Theory, Cognitive Film

- Theory, Critical Media

- Theory, Feminist Film

- Theory, Film

- Theory, Trauma

- Touch of Evil

- Transnational and Diasporic Cinema

- Trinh, T. Minh-ha

- Truffaut, François

- Turkish Cinema

- Twilight Zone, The

- Varda, Agnès

- Vertov, Dziga

- Video and Computer Games

- Video Installation

- Violence and Cinema

- Virtual Reality

- Visconti, Luchino

- Von Sternberg, Josef

- Von Stroheim, Erich

- von Trier, Lars

- Warhol, The Films of Andy

- Waters, John

- Wayne, John

- Weerasethakul, Apichatpong

- Weir, Peter

- Welles, Orson

- Whedon, Joss

- Wilder, Billy

- Williams, John

- Wiseman, Frederick

- Wizard of Oz, The

- Women and Film

- Women and the Silent Screen

- Wong, Anna May

- Wong, Kar-wai

- Wood, Natalie

- Yang, Edward

- Yimou, Zhang

- Yugoslav and Post-Yugoslav Cinema

- Zinnemann, Fred

- Zombies in Cinema and Media

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [109.248.223.228]

- 109.248.223.228

Text size: A A A

About the BFI

Strategy and policy

Press releases and media enquiries

Jobs and opportunities

Join and support

Become a Member

Become a Patron

Using your BFI Membership

Corporate support

Trusts and foundations

Make a donation

Watch films on BFI Player

BFI Southbank tickets

- Follow @bfi

Watch and discover

In this section

Watch at home on BFI Player

What’s on at BFI Southbank

What’s on at BFI IMAX

BFI National Archive

Explore our festivals

BFI film releases

Read features and reviews

Read film comment from Sight & Sound

I want to…

Watch films online

Browse BFI Southbank seasons

Book a film for my cinema

Find out about international touring programmes

Learning and training

BFI Film Academy: opportunities for young creatives

Get funding to progress my creative career

Find resources and events for teachers

Join events and activities for families

BFI Reuben Library

Search the BFI National Archive collections

Browse our education events

Use film and TV in my classroom

Read research data and market intelligence

Funding and industry

Get funding and support

Search for projects funded by National Lottery

Apply for British certification and tax relief

Industry data and insights

Inclusion in the film industry

Find projects backed by the BFI

Get help as a new filmmaker and find out about NETWORK

Read industry research and statistics

Find out about booking film programmes internationally

You are here

The essay film

In recent years the essay film has attained widespread recognition as a particular category of film practice, with its own history and canonical figures and texts. In tandem with a major season throughout August at London’s BFI Southbank, Sight & Sound explores the characteristics that have come to define this most elastic of forms and looks in detail at a dozen influential milestone essay films.

Andrew Tracy , Katy McGahan , Olaf Möller , Sergio Wolf , Nina Power Updated: 7 May 2019

from our August 2013 issue

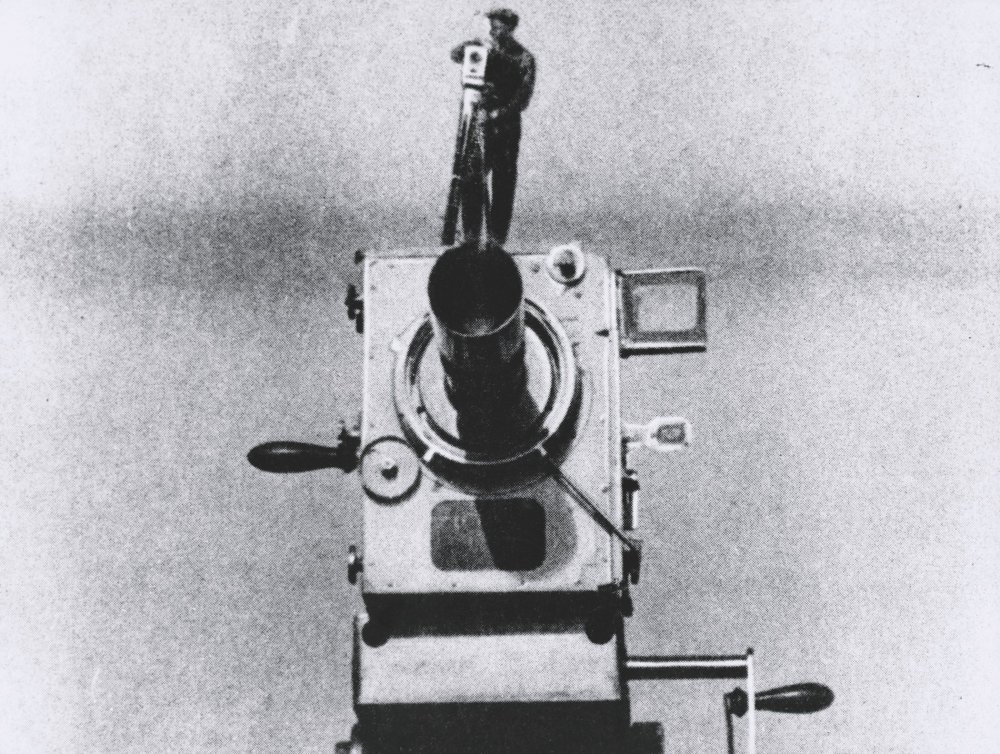

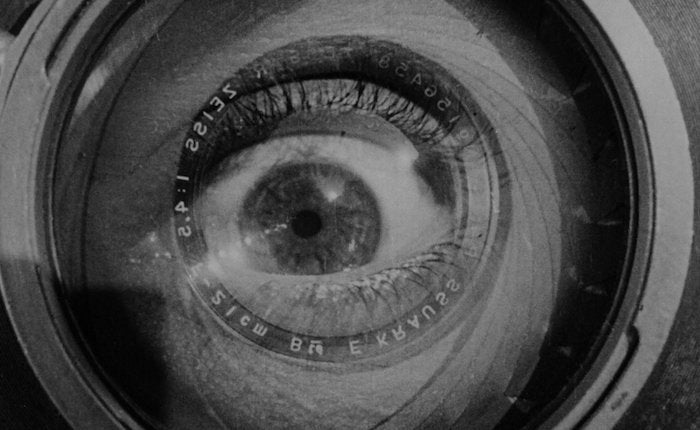

Le camera stylo? Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

I recently had a heated argument with a cinephile filmmaking friend about Chris Marker’s Sans soleil (1983). Having recently completed her first feature, and with such matters on her mind, my friend contended that the film’s power lay in its combinations of image and sound, irrespective of Marker’s inimitable voiceover narration. “Do you think that people who can’t understand English or French will get nothing out of the film?” she said; to which I – hot under the collar – replied that they might very well get something, but that something would not be the complete work.

The Sight & Sound Deep Focus season Thought in Action: The Art of the Essay Film runs at BFI Southbank 1-28 August 2013, with a keynote lecture by Kodwo Eshun on 1 August, a talk by writer and academic Laura Rascaroli on 27 August and a closing panel debate on 28 August.

To take this film-lovers’ tiff to a more elevated plane, what it suggests is that the essentialist conception of cinema is still present in cinephilic and critical culture, as are the difficulties of containing within it works that disrupt its very fabric. Ever since Vachel Lindsay published The Art of the Moving Picture in 1915 the quest to secure the autonomy of film as both medium and art – that ever-elusive ‘pure cinema’ – has been a preoccupation of film scholars, critics, cinephiles and filmmakers alike. My friend’s implicit derogation of the irreducible literary element of Sans soleil and her neo- Godard ian invocation of ‘image and sound’ touch on that strain of this phenomenon which finds, in the technical-functional combination of those two elements, an alchemical, if not transubstantiational, result.

Mechanically created, cinema defies mechanism: it is poetic, transportive and, if not irrational, then a-rational. This mystically-minded view has a long and illustrious tradition in film history, stretching from the sense-deranging surrealists – who famously found accidental poetry in the juxtapositions created by randomly walking into and out of films; to the surrealist-influenced, scientifically trained and ontologically minded André Bazin , whose realist veneration of the long take centred on the very preternaturalness of nature as revealed by the unblinking gaze of the camera; to the trash-bin idolatry of the American underground, weaving new cinematic mythologies from Hollywood detritus; and to auteurism itself, which (in its more simplistic iterations) sees the essence of the filmmaker inscribed even upon the most compromised of works.

It isn’t going too far to claim that this tradition has constituted the foundation of cinephilic culture and helped to shape the cinematic canon itself. If Marker has now been welcomed into that canon and – thanks to the far greater availability of his work – into the mainstream of (primarily DVD-educated) cinephilia, it is rarely acknowledged how much of that work cheerfully undercuts many of the long-held assumptions and pieties upon which it is built.

In his review of Letter from Siberia (1957), Bazin placed Marker at right angles to cinema proper, describing the film’s “primary material” as intelligence – specifically a “verbal intelligence” – rather than image. He dubbed Marker’s method a “horizontal” montage, “as opposed to traditional montage that plays with the sense of duration through the relationship of shot to shot”.

Here, claimed Bazin, “a given image doesn’t refer to the one that preceded it or the one that will follow, but rather it refers laterally, in some way, to what is said.” Thus the very thing which makes Letter “extraordinary”, in Bazin’s estimation, is also what makes it not-cinema. Looking for a term to describe it, Bazin hit upon a prophetic turn of phrase, writing that Marker’s film is, “to borrow Jean Vigo’s formulation of À propos de Nice (‘a documentary point of view’), an essay documented by film. The important word is ‘essay’, understood in the same sense that it has in literature – an essay at once historical and political, written by a poet as well.”

Marker’s canonisation has proceeded apace with that of the form of which he has become the exemplar. Whether used as critical/curatorial shorthand in reviews and programme notes, employed as a model by filmmakers or examined in theoretical depth in major retrospectives (this summer’s BFI Southbank programme, for instance, follows upon Andréa Picard’s two-part series ‘The Way of the Termite’ at TIFF Cinémathèque in 2009-2010, which drew inspiration from Jean-Pierre Gorin ’s groundbreaking programme of the same title at Vienna Filmmuseum in 2007), the ‘essay film’ has attained in recent years widespread recognition as a particular, if perennially porous, mode of film practice. An appealingly simple formulation, the term has proved both taxonomically useful and remarkably elastic, allowing one to define a field of previously unassimilable objects while ranging far and wide throughout film history to claim other previously identified objects for this invented tradition.

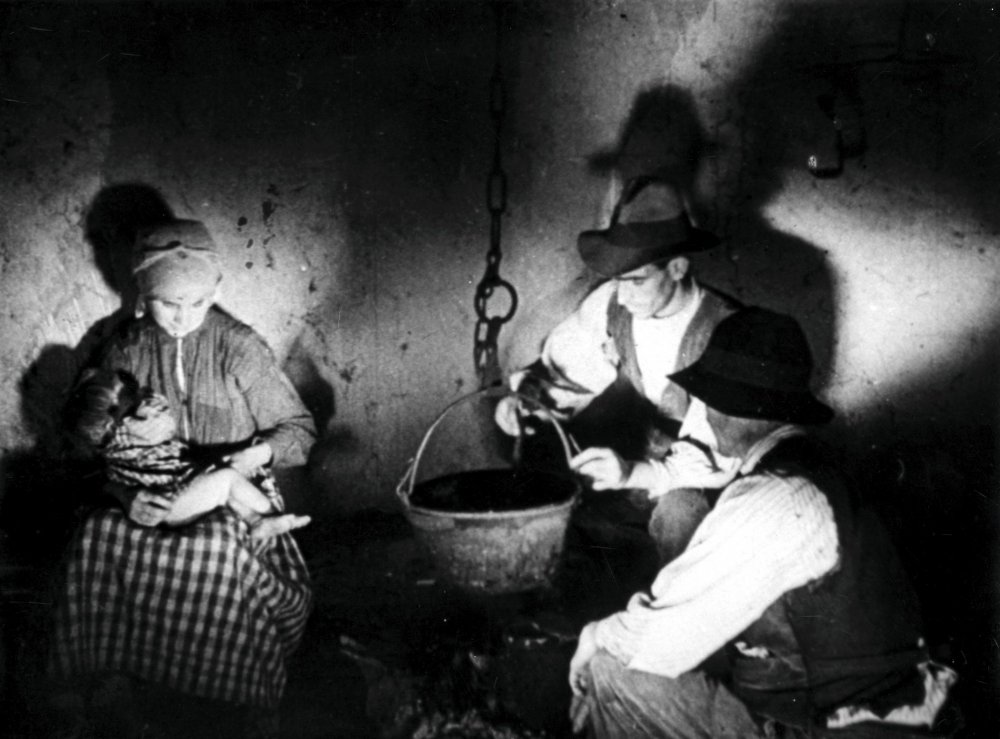

Las Hurdes (1933)

It is crucial to note that the ‘essay film’ is not only a post-facto appellation for a kind of film practice that had not bothered to mark itself with a moniker, but also an invention and an intervention. While it has acquired its own set of canonical ‘texts’ that include the collected works of Marker, much of Godard – from the missive (the 52-minute Letter to Jane , 1972) to the massive ( Histoire(s) de cinéma , 1988-98) – Welles’s F for Fake (1973) and Thom Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003), it has also poached on the territory of other, ‘sovereign’ forms, expanding its purview in accordance with the whims of its missionaries.

From documentary especially, Vigo’s aforementioned À propos de Nice, Ivens’s Rain (1929), Buñuel’s sardonic Las Hurdes (1933), Resnais’s Night and Fog (1955), Rouch and Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer (1961); from the avant garde, Akerman’s Je, Tu, Il, Elle (1974), Straub/Huillet’s Trop tôt, trop tard (1982); from agitprop, Getino and Solanas’s The Hour of the Furnaces (1968), Portabella’s Informe general… (1976); and even from ‘pure’ fiction, for example Gorin’s provocative selection of Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat (1909).

Just as within itself the essay film presents, in the words of Gorin, “the meandering of an intelligence that tries to multiply the entries and the exits into the material it has elected (or by which it has been elected),” so, without, its scope expands exponentially through the industrious activity of its adherents, blithely cutting across definitional borders and – as per the Manny Farber ian concept which gave Gorin’s ‘Termite’ series its name – creating meaning precisely by eating away at its own boundaries. In the scope of its application and its association more with an (amorphous) sensibility as opposed to fixed rules, the essay film bears similarities to the most famous of all fabricated genres: film noir, which has been located both in its natural habitat of the crime thriller as well as in such disparate climates as melodramas, westerns and science fiction.

The essay film, however, has proved even more peripatetic: where noir was formulated from the films of a determinate historical period (no matter that the temporal goalposts are continually shifted), the essay film is resolutely unfixed in time; it has its choice of forebears. And while noir, despite its occasional shadings over into semi-documentary during the 1940s, remains bound to fictional narratives, the essay film moves blithely between the realms of fiction and non-fiction, complicating the terms of both.

“Here is a form that seems to accommodate the two sides of that divide at the same time, that can navigate from documentary to fiction and back, creating other polarities in the process between which it can operate,” writes Gorin. When Orson Welles , in the closing moments of his masterful meditation on authenticity and illusion F for Fake, chortles, “I did promise that for one hour, I’d tell you only the truth. For the past 17 minutes, I’ve been lying my head off,” he is expressing both the conjuror’s pleasure in a trick well played and the artist’s delight in a self-defined mode that is cheerfully impure in both form and, perhaps, intention.

Nevertheless, as the essay film merrily traipses through celluloid history it intersects with ‘pure cinema’ at many turns and its form as such owes much to one particularly prominent variety thereof.

The montage tradition

If the mystical strain described above represents the Dionysian side of pure cinema, Soviet montage was its Apollonian opposite: randomness, revelation and sensuous response countered by construction, forceful argumentation and didactic instruction.

No less than the mystics, however, the montagists were after essences. Eisenstein , Dziga Vertov and Pudovkin , along with their transnational associates and acolytes, sought to crystallise abstract concepts in the direct and purposeful juxtaposition of forceful, hard-edged images – the general made powerfully, viscerally immediate in the particular. Here, says Eisenstein, in the umbrella-wielding harpies who set upon the revolutionaries in October (1928), is bourgeois Reaction made manifest; here, in the serried ranks of soldiers proceeding as one down the Odessa Steps in Battleship Potemkin (1925), is Oppression undisguised; here, in the condemned Potemkin sailor who wins over his imminent executioners with a cry of “Brothers!” – a moment powerfully invoked by Marker at the beginning of his magnum opus A Grin Without a Cat (1977) – is Solidarity emergent and, from it, the seeds of Revolution.

The relentlessly unidirectional focus of classical Soviet montage puts it methodologically and temperamentally at odds with the ruminative, digressive and playful qualities we associate with the essay film. So, too, the former’s fierce ideological certainty and cadre spirit contrast with that free play of the mind, the Montaigne -inspired meanderings of individual intelligence, that so characterise our image of the latter.

Beyond Marker’s personal interest in and inheritance from the Soviet masters, classical montage laid the foundations of the essay film most pertinently in its foregrounding of the presence, within the fabric of the film, of a directing intelligence. Conducting their experiments in film not through ‘pure’ abstraction but through narrative, the montagists made manifest at least two operative levels within the film: the narrative itself and the arrangement of that narrative by which the deeper structures that move it are made legible. Against the seamless, immersive illusionism of commercial cinema, montage was a key for decrypting those social forces, both overt and hidden, that govern human society.

And as such it was method rather than material that was the pathway to truth. Fidelity to the authentic – whether the accurate representation of historical events or the documentary flavouring of Eisensteinian typage – was important only insomuch as it provided the filmmaker with another tool to reach a considerably higher plane of reality.

Dziga Vertov’s Enthusiasm (1931)

Midway on their Marxian mission to change the world rather than interpret it, the montagists actively made the world even as they revealed it. In doing so they powerfully expressed the dialectic between control and chaos that would come to be not only one of the chief motors of the essay film but the crux of modernity itself.

Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), now claimed as the most venerable and venerated ancestor of the essay film (and this despite its prototypically purist claim to realise a ‘universal’ cinematic language “based on its complete separation from the language of literature and the theatre”) is the archetypal model of this high-modernist agon. While it is the turning of the movie projector itself and the penetrating gaze of Vertov’s kino-eye that sets the whirling dynamo of the city into motion, the recorder creating that which it records, that motion is also outside its control.

At the dawn of the cinematic century, the American writer Henry Adams saw in the dynamo both the expression of human mastery over nature and a conduit to mysterious, elemental powers beyond our comprehension. So, too, the modernist ambition expressed in literature, painting, architecture and cinema to capture a subject from all angles – to exhaust its wealth of surfaces, meanings, implications, resonances – collides with awe (or fear) before a plenitude that can never be encompassed.

Remove the high-modernist sense of mission and we can see this same dynamic as animating the essay film – recall that last, parenthetical term in Gorin’s formulation of the essay film, “multiply[ing] the entries and the exits into the material it has elected (or by which it has been elected)”. The nimble movements and multi-angled perspectives of the essay film are founded on this negotiation between active choice and passive possession; on the recognition that even the keenest insight pales in the face of an ultimate unknowability.

The other key inheritance the essay film received from the classical montage tradition, perhaps inevitably, was a progressive spirit, however variously defined. While Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938) amply and chillingly demonstrated that montage, like any instrumental apparatus, has no inherent ideological nature, hers were more the exceptions that proved the rule. (Though why, apart from ideological repulsiveness, should Riefenstahl’s plentifully fabricated ‘documentaries’ not be considered as essay films in their own right?)

The overwhelming fact remains that the great majority of those who drew upon the Soviet montagists for explicitly ideological ends (as opposed to Hollywood’s opportunistic swipings) resided on the left of the spectrum – and, in the montagists’ most notable successor in the period immediately following, retained their alignment with and inextricability from the state.

Progressive vs radical

The Grierson ian documentary movement in Britain neutered the political and aesthetic radicalism of its more dynamic model in favour of paternalistic progressivism founded on conformity, class complacency and snobbery towards its own medium. But if it offered a far paler antecedent to the essay film than the Soviet montage tradition, it nevertheless represents an important stage in the evolution of the essay-film form, for reasons not unrelated to some of those rather staid qualities.

The Soviet montagists had created a vision of modernity racing into the future at pace with the social and spiritual liberation of its proletarian pilot-passenger, an aggressively public ideology of group solidarity. The Grierson school, by contrast, offered a domesticated image of an efficient, rational and productive modern industrial society based on interconnected but separate public and private spheres, as per the ideological values of middle-class liberal individualism.

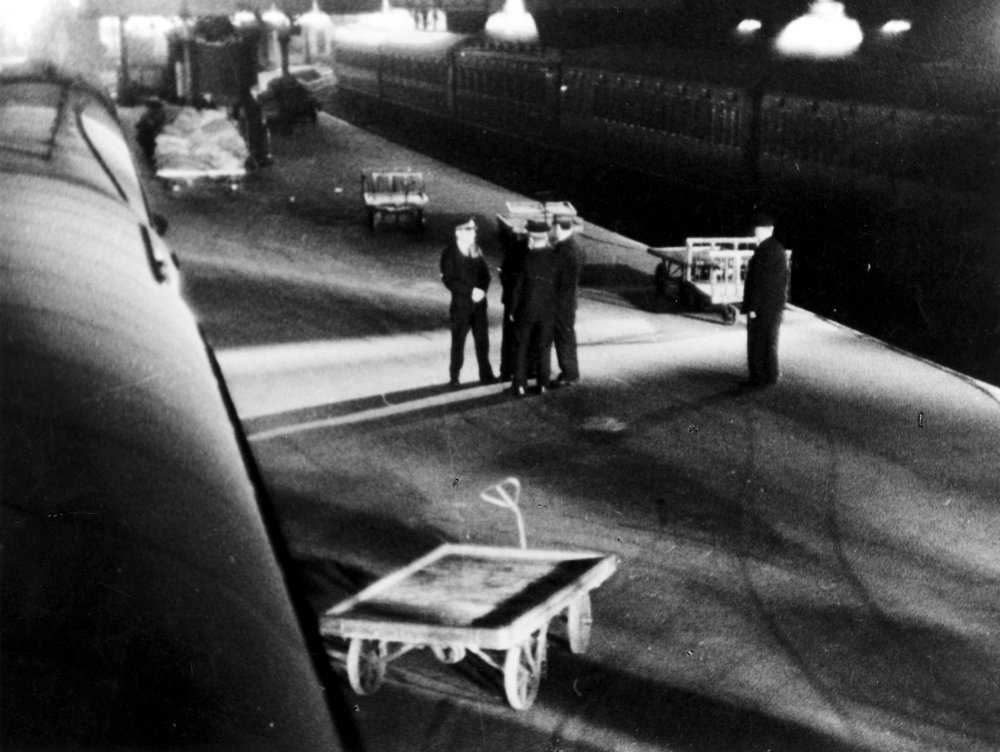

The Soviet montagists had looked to forge a universal, ‘pure’ cinematic language, at least before the oppressive dictates of Stalinist socialist realism shackled them. The Grierson school, evincing a middle-class disdain for the popular and ‘low’ arts, sought instead to purify the sullied medium of cinema by importing extra-cinematic prestige: most notably Night Mail (1936), with its Auden -penned, Britten -scored ode to the magic of the mail, or Humphrey Jennings’s salute to wartime solidarity A Diary for Timothy (1945), with its mildly sententious E.M. Forster narration.

Night Mail (1936)

What this domesticated dynamism and retrograde pursuit of high-cultural bona fides achieved, however, was to mingle a newfound cinematic language (montage) with a traditionally literary one (narration); and, despite the salutes to state-oriented communality, to re-introduce the individual, idiosyncratic voice as the vehicle of meaning – as the mediating intelligence that connects the viewer to the images viewed.

In Night Mail especially there is, in the whimsy of the Auden text and the film’s synchronisation of private time and public history, an intimation of the essay film’s musing, reflective voice as the chugging rhythm of the narration timed to the speeding wheels of the train gives way to a nocturnal vision of solitary dreamers bedevilled by spectral monsters, awakening in expectation of the postman’s knock with a “quickening of the heart/for who can bear to be forgot?”

It’s a curiously disquieting conclusion: this unsettling, anxious vision of disappearance that takes on an even darker shade with the looming spectre of war – one that rhymes, five decades on, with the wistful search of Marker’s narrator in Sans soleil, seeking those fleeting images which “quicken the heart” in a world where wars both past and present have been forgotten, subsumed in a modern society built upon the systematic banishment of memory.

It is, of course, with the seminal post-war collaborations between Marker and Alain Resnais that the essay film proper emerges. In contrast to the striving culture-snobbery of the Griersonian documentary, the Resnais-Marker collaborations (and the Resnais solo documentary shorts that preceded them) inaugurate a blithe, seemingly effortless dialogue between cinema and the other arts in both their subjects (painting, sculpture) and their assorted creative personnel (writers Paul Éluard , Jean Cayrol , Raymond Queneau , composers Darius Milhaud and Hanns Eisler ). This also marks the point where the revolutionary line of the Soviets and the soft, statist liberalism of the British documentarians give way to a more free-floating but staunchly oppositional leftism, one derived as much from a spirit of humanistic inquiry as from ideological affiliation.

Related to this was the form’s problems with official patronage. Originally conceived as commissions by various French government or government-affiliated bodies, the Resnais-Marker films famously ran into trouble from French censors: Les statues meurent aussi (1953) for its condemnation of French colonialism, Night and Fog for its shots of Vichy policemen guarding deportation camps; the former film would have its second half lopped off before being cleared for screening, the latter its offending shots removed.

Night and Fog (1955)

Appropriately, it is at this moment that the emphasis of the essay film begins to shift away from tactile presence – the whirl of the city, the rhythm of the rain, the workings of industry – to felt absence. The montagists had marvelled at the workings of human creations which raced ahead irrespective of human efforts; here, the systems created by humanity to master the world write, in their very functioning, an epitaph for those things extinguished in the act of mastering them. The African masks preserved in the Musée de l’Homme in Les statues meurent aussi speak of a bloody legacy of vanquished and conquered civilisations; the labyrinthine archival complex of the Bibliothèque Nationale in the sardonically titled Toute la mémoire du monde (1956) sparks a disquisition on all that is forgotten in the act of cataloguing knowledge; the miracle of modern plastics saluted in the witty, industrially commissioned Le Chant du styrène (1958) regresses backwards to its homely beginnings; in Night and Fog an unprecedentedly enormous effort of human organisation marshals itself to actively produce a dreadful, previously unimaginable nullity.

To overstate the case, loss is the primary motor of the modern essay film: loss of belief in the image’s ability to faithfully reflect reality; loss of faith in the cinema’s ability to capture life as it is lived; loss of illusions about cinema’s ‘purity’, its autonomy from the other arts or, for that matter, the world.

“You never know what you may be filming,” notes one of Marker’s narrating surrogates in A Grin Without a Cat, as footage of the Chilean equestrian team at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics offers a glimpse of a future member of the Pinochet junta. The image and sound captured at the time of filming offer one facet of reality; it is only with this lateral move outside that reality that the future reality it conceals can speak.

What will distinguish the essay film, as Bazin noted, is not only its ability to make the image but also its ability to interrogate it, to dispel the illusion of its sovereignty and see it as part of a matrix of meaning that extends beyond the screen. No less than were the montagists, the film-essayists seek the motive forces of modern society not by crystallising eternal verities in powerful images but by investigating that ever-shifting, kaleidoscopic relationship between our regime of images and the realities it both reveals and occludes.

— Andrew Tracy

1. À propos de Nice

Jean Vigo, 1930

Few documentaries have achieved the cult status of the 22-minute A propos de Nice, co-directed by Jean Vigo and cameraman Boris Kaufman at the beginning of their careers. The film retains a spontaneous, apparently haphazard, quality yet its careful montage combines a strong realist drive, lyrical dashes – helped by Marc Perrone’s accordion music – and a clear political agenda.

In today’s era, in which the Côte d’Azur has become a byword for hedonistic consumption, it’s refreshing to see a film that systematically undermines its glossy surface. Using images sometimes ‘stolen’ with hidden cameras, A propos de Nice moves between the city’s main sites of pleasure: the Casino, the Promenade des Anglais, the Hotel Negresco and the carnival. Occasionally the filmmakers remind us of the sea, the birds, the wind in the trees but mostly they contrast people: the rich play tennis, the poor boules; the rich have tea, the poor gamble in the (then) squalid streets of the Old Town.

As often, women bear the brunt of any critique of bourgeois consumption: a rich old woman’s head is compared to an ostrich, others grin as they gaze up at phallic factory chimneys; young women dance frenetically, their crotch to the camera. In the film’s most famous image, an elegant woman is ‘stripped’ by the camera to reveal her naked body – not quite matched by a man’s shoes vanishing to display his naked feet to the shoe-shine.

An essay film avant la lettre , A propos de Nice ends on Soviet-style workers’ faces and burning furnaces. The message is clear, even if it has not been heeded by history.

— Ginette Vincendeau

2. A Diary for Timothy

Humphrey Jennings, 1945

A Diary for Timothy takes the form of a journal addressed to the eponymous Timothy James Jenkins, born on 3 September 1944, exactly five years after Britain’s entry into World War II. The narrator, Michael Redgrave , a benevolent offscreen presence, informs young Timothy about the momentous events since his birth and later advises that, even when the war is over, there will be “everyday danger”.

The subjectivity and speculative approach maintained throughout are more akin to the essay tradition than traditional propaganda in their rejection of mere glib conveyance of information or thunderous hectoring. Instead Jennings invites us quietly to observe the nuances of everyday life as Britain enters the final chapter of the war. Against the momentous political backdrop, otherwise routine, everyday activities are ascribed new profundity as the Welsh miner Geronwy, Alan the farmer, Bill the railway engineer and Peter the convalescent fighter pilot go about their daily business.

Within the confines of the Ministry of Information’s remit – to lift the spirits of a battle-weary nation – and the loose narrative framework of Timothy’s first six months, Jennings finds ample expression for the kind of formal experiment that sets his work apart from that of other contemporary documentarians. He worked across film, painting, photography, theatrical design, journalism and poetry; in Diary his protean spirit finds expression in a manner that transgresses the conventional parameters of wartime propaganda, stretching into film poem, philosophical reflection, social document, surrealistic ethnographic observation and impressionistic symphony. Managing to keep to the right side of sentimentality, it still makes for potent viewing.

— Catherine McGahan

3. Toute la mémoire du monde

Alain Resnais, 1956

In the opening credits of Toute la mémoire du monde, alongside the director’s name and that of producer Pierre Braunberger , one reads the mysterious designation “Groupe des XXX”. This Group of Thirty was an assembly of filmmakers who mobilised in the early 1950s to defend the “style, quality and ambitious subject matter” of short films in post-war France; the signatories of its 1953 ‘Declaration’ included Resnais , Chris Marker and Agnès Varda. The success of the campaign contributed to a golden age of short filmmaking that would last a decade and form the crucible of the French essay film.

A 22-minute poetic documentary about the old French Bibliothèque Nationale, Toute la mémoire du monde is a key work in this strand of filmmaking and one which can also be seen as part of a loose ‘trilogy of memory’ in Resnais’s early documentaries. Les statues meurent aussi (co-directed with Chris Marker) explored cultural memory as embodied in African art and the depredations of colonialism; Night and Fog was a seminal reckoning with the historical memory of the Nazi death camps. While less politically controversial than these earlier works, Toute la mémoire du monde’s depiction of the Bibliothèque Nationale is still oddly suggestive of a prison, with its uniformed guards and endless corridors. In W.G. Sebald ’s 2001 novel Austerlitz, directly after a passage dedicated to Resnais’s film, the protagonist describes his uncertainty over whether, when using the library, he “was on the Islands of the Blest, or, on the contrary, in a penal colony”.

Resnais explores the workings of the library through the effective device of following a book from arrival and cataloguing to its delivery to a reader (the book itself being something of an in-joke: a mocked-up travel guide to Mars in the Petite Planète series Marker was then editing for Editions du Seuil). With Resnais’s probing, mobile camerawork and a commentary by French writer Remo Forlani, Toute la mémoire du monde transforms the library into a mysterious labyrinth, something between an edifice and an organism: part brain and part tomb.

— Chris Darke

4. The House is Black

(Khaneh siah ast) Forough Farrokhzad, 1963

Before the House of Makhmalbaf there was The House is Black. Called “the greatest of all Iranian films” by critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, who helped translate the subtitles from Farsi into English, this 20-minute black-and-white essay film by feminist poet Farrokhzad was shot in a leper colony near Tabriz in northern Iran and has been heralded as the touchstone of the Iranian New Wave.

The buildings of the Baba Baghi colony are brick and peeling whitewash but a student asked to write a sentence using the word ‘house’ offers Khaneh siah ast : the house is black. His hand, seen in close-up, is one of many in the film; rather than objects of medical curiosity, these hands – some fingerless, many distorted by the disease – are agents, always in movement, doing, making, exercising, praying. In putting white words on the blackboard, the student makes part of the film; in the next shots, the film’s credits appear, similarly handwritten on the same blackboard.

As they negotiate the camera’s gaze and provide the soundtrack by singing, stamping and wheeling a barrow, the lepers are co-authors of the film. Farrokhzad echoes their prayers, heard and seen on screen, with her voiceover, which collages religious texts, beginning with the passage from Psalm 55 famously set to music by Mendelssohn (“O for the wings of a dove”).

In the conjunctions between Farrokhzad’s poetic narration and diegetic sound, including tanbur-playing, an intense assonance arises. Its beat is provided by uniquely lyrical associative editing that would influence Abbas Kiarostami , who quotes Farrokhzad’s poem ‘The Wind Will Carry Us’ in his eponymous film . Repeated shots of familiar bodily movement, made musical, move the film insistently into the viewer’s body: it is infectious. Posing a question of aesthetics, The House Is Black uses the contagious gaze of cinema to dissolve the screen between Us and Them.

— Sophie Mayer

5. Letter to Jane: An Investigation About a Still

Jean-Luc Godard & Jean-Pierre Gorin, 1972

With its invocation of Brecht (“Uncle Bertolt”), rejection of visual pleasure (for 52 minutes we’re mostly looking at a single black-and-white still) and discussion of the role of intellectuals in “the revolution”, Letter to Jane is so much of its time as to appear untranslatable to the present except as a curio from a distant era of radical cinema. Between 1969 and 1971, Godard and Gorin made films collectively as part of the Dziga Vertov Group before they returned, in 1972, to the mainstream with Tout va bien , a big-budget film about the aftermath of May 1968 featuring leftist stars Yves Montand and Jane Fonda . It was to the latter that Godard and Gorin directed their Letter after seeing a news photograph of her on a solidarity visit to North Vietnam in August 1972.

Intended to accompany the US release of Tout va bien, Letter to Jane is ‘a letter’ only in as much as it is fairly conversational in tone, with Godard and Gorin delivering their voiceovers in English. It’s stylistically more akin to the ‘blackboard films’ of the time, with their combination of pedagogical instruction and stern auto-critique.

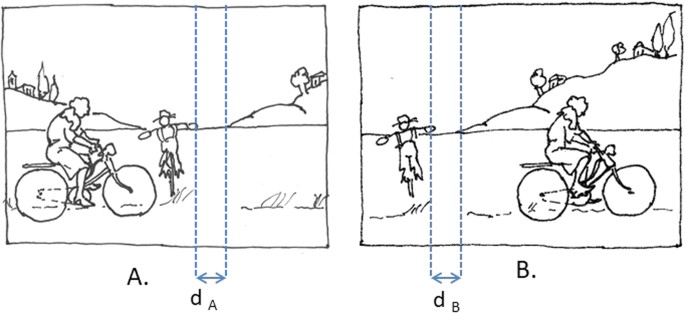

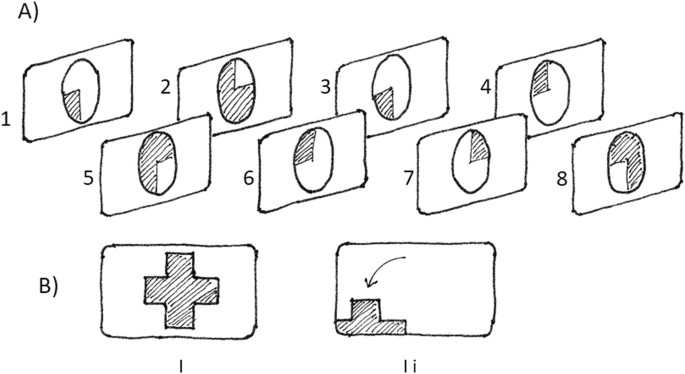

It’s also an inspired semiological reading of a media image and a reckoning with the contradictions of celebrity activism. Godard and Gorin examine the image’s framing and camera angle and ask why Fonda is the ‘star’ of the photograph while the Vietnamese themselves remain faceless or out of focus? And what of her expression of compassionate concern? This “expression of an expression” they trace back, via an elaboration of the Kuleshov effect , through other famous faces – Henry Fonda , John Wayne , Lillian Gish and Falconetti – concluding that it allows for “no reverse shot” and serves only to bolster Western “good conscience”.

Letter to Jane is ultimately concerned with the same question that troubled philosophers such as Levinas and Derrida : what’s at stake ethically when one claims to speak “in place of the other”? Any contemporary critique of celebrity activism – from Bono and Geldof to Angelina Jolie – should start here, with a pair of gauchiste trolls muttering darkly beneath a press shot of ‘Hanoi Jane’.

6. F for Fake

Orson Welles, 1973

Those who insist it was all downhill for Orson Welles after Citizen Kane would do well to take a close look at this film made more than three decades later, in its own idiosyncratic way a masterpiece just as innovative as his better-known feature debut.

Perhaps the film’s comparative and undeserved critical neglect is due to its predominantly playful tone, or perhaps it’s because it is a low-budget, hard-to-categorise, deeply personal work that mixes original material with plenty of footage filmed by others – most extensively taken from a documentary by François Reichenbach about Clifford Irving and his bogus biography of his friend Elmyr de Hory , an art forger who claimed to have painted pictures attributed to famous names and hung in the world’s most prestigious galleries.

If the film had simply offered an account of the hoaxes perpetrated by that disreputable duo, it would have been entertaining enough but, by means of some extremely inventive, innovative and inspired editing, Welles broadens his study of fakery to take in his own history as a ‘charlatan’ – not merely his lifelong penchant for magician’s tricks but also the 1938 radio broadcast of his news-report adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds – as well as observations on Howard Hughes , Pablo Picasso and the anonymous builders of Chartres cathedral. So it is that Welles contrives to conjure up, behind a colourful cloak of consistently entertaining mischief, a rueful meditation on truth and falsehood, art and authorship – a subject presumably dear to his heart following Pauline Kael ’s then recent attempts to persuade the world that Herman J. Mankiewicz had been the real creative force behind Kane.

As a riposte to that thesis (albeit never framed as such), F for Fake is subtle, robust, supremely erudite and never once bitter; the darkest moment – as Welles contemplates the serene magnificence of Chartres – is at once an uncharacteristic but touchingly heartfelt display of humility and a poignant memento mori. And it is in this delicate balancing of the autobiographical with the universal, as well as in the dazzling deployment of cinematic form to illustrate and mirror content, that the film works its once unique, now highly influential magic.

— Geoff Andrew

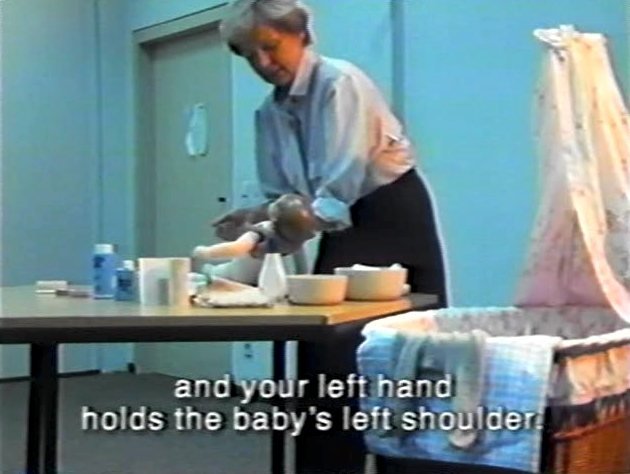

7. How to Live in the German Federal Republic

(Leben – BRD) Harun Farocki, 1990

Harun Farocki ’s portrait of West Germany in 32 simulations from training sessions has no commentary, just the actions themselves in all their surreal beauty, one after the other. The Bundesrepublik Deutschland is shown as a nation of people who can deal with everything because they have been prepared – taught how to react properly in every possible situation.

We know how birth works; how to behave in kindergarten; how to chat up girls, boys or whatever we fancy (for we’re liberal-minded, if only in principle); how to look for a job and maybe live without finding one; how to wiggle our arses in the hottest way possible when we pole-dance, or manage a hostage crisis without things getting (too) bloody. Whatever job we do, we know it by heart; we also know how to manage whatever kind of psychological breakdown we experience; and we are also prepared for the end, and even have an idea about how our burial will go. This is the nation: one of fearful people in dire need of control over their one chance of getting it right.

Viewed from the present, How to Live in the German Federal Republic is revealed as the archetype of many a Farocki film in the decades to follow, for example Die Umschulung (1994), Der Auftritt (1996) or Nicht ohne Risiko (2004), all of which document as dispassionately as possible different – not necessarily simulated – scenarios of social interactions related to labour and capital. For all their enlightening beauty, none of these ever came close to How to Live in the German Federal Republic which, depending on one’s mood, can play like an absurd comedy or the most gut-wrenching drama. Yet one disquieting thing is certain: How to Live in the German Federal Republic didn’t age – our lives still look the same.

— Olaf Möller

8. One Man’s War

(La Guerre d’un seul homme) Edgardo Cozarinsky , 1982

One Man’s War proves that an auteur film can be made without writing a line, recording a sound or shooting a single frame. It’s easy to point to the ‘extraordinary’ character of the film, given its combination of materials that were not made to cohabit; there couldn’t be a less plausible dialogue than the one Cozarinsky establishes between the newsreels shot during the Nazi occupation of Paris and the Parisian diaries of novelist and Nazi officer Ernst Jünger . There’s some truth to Pascal Bonitzer’s assertion in Cahiers du cinéma in 1982 that the principle of the documentary was inverted here, since it is the images that provide a commentary for the voice.

But that observation still doesn’t pin down the uniqueness of a work that forces history through a series of registers, styles and dimensions, wiping out the distance between reality and subjectivity, propaganda and literature, cinema and journalism, daily life and dream, and establishing the idea not so much of communicating vessels as of contaminating vessels.

To enquire about the essayistic dimension of One Man’s War is to submit it to a test of purity against which the film itself is rebelling. This is no ars combinatoria but systems of collision and harmony; organic in their temporal development and experimental in their procedural eagerness. It’s like a machine created to die instantly; neither Cozarinsky nor anyone else could repeat the trick, as is the case with all great avant-garde works.

By blurring the genre of his literary essays, his fictional films, his archival documentaries, his literary fictions, Cozarinsky showed he knew how to reinvent the erasure of borders. One Man’s War is not a film about the Occupation but a meditation on the different forms in which that Occupation can be represented.

—Sergio Wolf. Translated by Mar Diestro-Dópido

9. Sans soleil

Chris Marker, 1982

There are many moments to quicken the heart in Sans soleil but one in particular demonstrates the method at work in Marker’s peerless film. An unseen female narrator reads from letters sent to her by a globetrotting cameraman named Sandor Krasna (Marker’s nom de voyage), one of which muses on the 11th-century Japanese writer Sei Shōnagon .

As we hear of Shōnagon’s “list of elegant things, distressing things, even of things not worth doing”, we watch images of a missile being launched and a hovering bomber. What’s the connection? There is none. Nothing here fixes word and image in illustrative lockstep; it’s in the space between them that Sans soleil makes room for the spectator to drift, dream and think – to inimitable effect.

Sans soleil was Marker’s return to a personal mode of filmmaking after more than a decade in militant cinema. His reprise of the epistolary form looks back to earlier films such as Letter from Siberia (1958) but the ‘voice’ here is both intimate and removed. The narrator’s reading of Krasna’s letters flips the first person to the third, using ‘he’ instead of ‘I’. Distance and proximity in the words mirror, multiply and magnify both the distances travelled and the time spanned in the images, especially those of the 1960s and its lost dreams of revolutionary social change.

While it’s handy to define Sans soleil as an ‘essay film’, there’s something about the dry term that doesn’t do justice to the experience of watching it. After Marker’s death last year, when writing programme notes on the film, I came up with a line that captures something of what it’s like to watch Sans soleil: “a mesmerising, lucid and lovely river of film, which, like the river of the ancients, is never the same when one steps into it a second time”.

10. Handsworth Songs

Black Audio Film Collective, 1986

Made at the time of civil unrest in Birmingham, this key example of the essay film at its most complex remains relevant both formally and thematically. Handsworth Songs is no straightforward attempt to provide answers as to why the riots happened; instead, using archive film spliced with made and found footage of the events and the media and popular reaction to them, it creates a poetic sense of context.

The film is an example of counter-media in that it slows down the demand for either immediate explanation or blanket condemnation. Its stillness allows the history of immigration and the subsequent hostility of the media and the police to the black and Asian population to be told in careful detail.

One repeated scene shows a young black man running through a group of white policemen who surround him on all sides. He manages to break free several times before being wrestled to the ground; if only for one brief, utopian moment, an entirely different history of race in the UK is opened up.

The waves of post-war immigration are charted in the stories told both by a dominant (and frequently repressive) televisual narrative and, importantly, by migrants themselves. Interviews mingle with voiceover, music accompanies the machines that the Windrush generation work at. But there are no definitive answers here, only, as the Black Audio Film Collective memorably suggests, “the ghosts of songs”.

— Nina Power

11. Los Angeles Plays Itself

Thom Andersen, 2003

One of the attractions that drew early film pioneers out west, besides the sunlight and the industrial freedom, was the versatility of the southern Californian landscape: with sea, snowy mountains, desert, fruit groves, Spanish missions, an urban downtown and suburban boulevards all within a 100-mile radius, the Los Angeles basin quickly and famously became a kind of giant open-air film studio, available and pliant.

Of course, some people actually live there too. “Sometimes I think that gives me the right to criticise,” growls native Angeleno Andersen in his forensic three-hour prosecution of moving images of the movie city, whose mounting litany of complaints – couched in Encke King’s gravelly, near-parodically irritated voiceover, and sometimes organised, as Stuart Klawans wrote in The Nation, “in the manner of a saloon orator” – belies a sly humour leavening a radically serious intent.

Inspired in part by Mark Rappaport’s factual essay appropriations of screen fictions (Rock Hudson’s Home Movies, 1993; From the Journals of Jean Seberg , 1995), as well as Godard’s Histoire(s) de cinéma, this “city symphony in reverse” asserts public rights to our screen discourse through its magpie method as well as its argument. (Today you could rebrand it ‘Occupy Hollywood’.) Tinseltown malfeasance is evidenced across some 200 different film clips, from offences against geography and slurs against architecture to the overt historical mythologies of Chinatown (1974), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) and L.A. Confidential (1997), in which the city’s class and cultural fault-lines are repainted “in crocodile tears” as doleful tragedies of conspiracy, promoting hopelessness in the face of injustice.

Andersen’s film by contrast spurs us to independent activism, starting with the reclamation of our gaze: “What if we watch with our voluntary attention, instead of letting the movies direct us?” he asks, peering beyond the foregrounding of character and story. And what if more movies were better and more useful, helping us see our world for what it is? Los Angeles Plays Itself grows most moving – and useful – extolling the Los Angeles neorealism Andersen has in mind: stories of “so many men unneeded, unwanted”, as he says over a scene from Billy Woodberry’s Bless Their Little Hearts (1983), “in a world in which there is so much to be done”.

— Nick Bradshaw

12. La Morte Rouge

Víctor Erice, 2006

The famously unprolific Spanish director Víctor Erice may remain best known for his full-length fiction feature The Spirit of the Beehive (1973), but his other films are no less rewarding. Having made a brilliant foray into the fertile territory located somewhere between ‘documentary’ and ‘fiction’ with The Quince Tree Sun (1992), in this half-hour film made for the ‘Correspondences’ exhibition exploring resemblances in the oeuvres of Erice and Kiarostami , the relationship between reality and artifice becomes his very subject.

A ‘small’ work, it comprises stills, archive footage, clips from an old Sherlock Holmes movie, a few brief new scenes – mostly without actors – and music by Mompou and (for once, superbly used) Arvo Pärt . If its tone – it’s introduced as a “soliloquy” – and scale are modest, its thematic range and philosophical sophistication are considerable.

The title is the name of the Québécois village that is the setting for The Scarlet Claw (1944), a wartime Holmes mystery starring Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce which was the first movie Erice ever saw, taken by his sister to the Kursaal cinema in San Sebastian.

For the five-year-old, the experience was a revelation: unable to distinguish the ‘reality’ of the newsreel from that of the nightmare world of Roy William Neill’s film, he not only learned that death and murder existed but noted that the adults in the audience, presumably privy to some secret knowledge denied him, were unaffected by the corpses on screen. Had this something to do with war? Why was La Morte Rouge not on any map? And what did it signify that postman Potts was not, in fact, Potts but the killer – and an actor (whatever that was) to boot?

From such personal reminiscences – evoked with wondrous intimacy in the immaculate Castillian of the writer-director’s own wry narration – Erice fashions a lyrical meditation on themes that have underpinned his work from Beehive to Broken Windows (2012): time and change, memory and identity, innocence and experience, war and death. And because he understands, intellectually and emotionally, that the time-based medium he himself works in can reveal unforgettably vivid realities that belong wholly to the realm of the imaginary, La Morte Rouge is a great film not only about the power of cinema but about life itself.

Sight & Sound: the August 2013 issue

In this issue: Frances Ha’s Greta Gerwig – the most exciting actress in America? Plus Ryan Gosling in Only God Forgives, Wadjda, The Wall,...

More from this issue

DVDs and Blu Ray

Buy The Complete Humphrey Jennings Collection Volume Three: A Diary for Timothy on DVD and Blu Ray

Humphrey Jennings’s transition from wartime to peacetime filmmaking.

Buy Chronicle of a Summer on DVD and Blu Ray

Jean Rouch’s hugely influential and ground-breaking documentary.

Further reading

Video essay: The essay film – some thoughts of discontent

Kevin B. Lee

The land still lies: Handsworth Songs and the English riots

The world at sea: The Forgotten Space

What I owe to Chris Marker

Patricio Guzmán

His and her ghosts: reworking La Jetée

Melissa Bradshaw

At home (and away) with Agnès Varda

Daniel Trilling

Pere Portabella looks back

John Akomfrah’s Hauntologies

Laura Allsop

Back to the top

Commercial and licensing

BFI distribution

Archive content sales and licensing

BFI book releases and trade sales

Selling to the BFI

Terms of use

BFI Southbank purchases

Online community guidelines

Cookies and privacy

©2024 British Film Institute. All rights reserved. Registered charity 287780.

See something different

Subscribe now for exclusive offers and the best of cinema. Hand-picked.

Film Analysis

What this handout is about.

This handout introduces film analysis and and offers strategies and resources for approaching film analysis assignments.

Writing the film analysis essay

Writing a film analysis requires you to consider the composition of the film—the individual parts and choices made that come together to create the finished piece. Film analysis goes beyond the analysis of the film as literature to include camera angles, lighting, set design, sound elements, costume choices, editing, etc. in making an argument. The first step to analyzing the film is to watch it with a plan.

Watching the film

First it’s important to watch the film carefully with a critical eye. Consider why you’ve been assigned to watch a film and write an analysis. How does this activity fit into the course? Why have you been assigned this particular film? What are you looking for in connection to the course content? Let’s practice with this clip from Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). Here are some tips on how to watch the clip critically, just as you would an entire film:

- Give the clip your undivided attention at least once. Pay close attention to details and make observations that might start leading to bigger questions.

- Watch the clip a second time. For this viewing, you will want to focus specifically on those elements of film analysis that your class has focused on, so review your course notes. For example, from whose perspective is this clip shot? What choices help convey that perspective? What is the overall tone, theme, or effect of this clip?

- Take notes while you watch for the second time. Notes will help you keep track of what you noticed and when, if you include timestamps in your notes. Timestamps are vital for citing scenes from a film!

For more information on watching a film, check out the Learning Center’s handout on watching film analytically . For more resources on researching film, including glossaries of film terms, see UNC Library’s research guide on film & cinema .

Brainstorming ideas

Once you’ve watched the film twice, it’s time to brainstorm some ideas based on your notes. Brainstorming is a major step that helps develop and explore ideas. As you brainstorm, you may want to cluster your ideas around central topics or themes that emerge as you review your notes. Did you ask several questions about color? Were you curious about repeated images? Perhaps these are directions you can pursue.

If you’re writing an argumentative essay, you can use the connections that you develop while brainstorming to draft a thesis statement . Consider the assignment and prompt when formulating a thesis, as well as what kind of evidence you will present to support your claims. Your evidence could be dialogue, sound edits, cinematography decisions, etc. Much of how you make these decisions will depend on the type of film analysis you are conducting, an important decision covered in the next section.

After brainstorming, you can draft an outline of your film analysis using the same strategies that you would for other writing assignments. Here are a few more tips to keep in mind as you prepare for this stage of the assignment:

- Make sure you understand the prompt and what you are being asked to do. Remember that this is ultimately an assignment, so your thesis should answer what the prompt asks. Check with your professor if you are unsure.

- In most cases, the director’s name is used to talk about the film as a whole, for instance, “Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo .” However, some writers may want to include the names of other persons who helped to create the film, including the actors, the cinematographer, and the sound editor, among others.

- When describing a sequence in a film, use the literary present. An example could be, “In Vertigo , Hitchcock employs techniques of observation to dramatize the act of detection.”

- Finding a screenplay/script of the movie may be helpful and save you time when compiling citations. But keep in mind that there may be differences between the screenplay and the actual product (and these differences might be a topic of discussion!).

- Go beyond describing basic film elements by articulating the significance of these elements in support of your particular position. For example, you may have an interpretation of the striking color green in Vertigo , but you would only mention this if it was relevant to your argument. For more help on using evidence effectively, see the section on “using evidence” in our evidence handout .

Also be sure to avoid confusing the terms shot, scene, and sequence. Remember, a shot ends every time the camera cuts; a scene can be composed of several related shots; and a sequence is a set of related scenes.

Different types of film analysis

As you consider your notes, outline, and general thesis about a film, the majority of your assignment will depend on what type of film analysis you are conducting. This section explores some of the different types of film analyses you may have been assigned to write.

Semiotic analysis

Semiotic analysis is the interpretation of signs and symbols, typically involving metaphors and analogies to both inanimate objects and characters within a film. Because symbols have several meanings, writers often need to determine what a particular symbol means in the film and in a broader cultural or historical context.

For instance, a writer could explore the symbolism of the flowers in Vertigo by connecting the images of them falling apart to the vulnerability of the heroine.

Here are a few other questions to consider for this type of analysis:

- What objects or images are repeated throughout the film?

- How does the director associate a character with small signs, such as certain colors, clothing, food, or language use?

- How does a symbol or object relate to other symbols and objects, that is, what is the relationship between the film’s signs?

Many films are rich with symbolism, and it can be easy to get lost in the details. Remember to bring a semiotic analysis back around to answering the question “So what?” in your thesis.

Narrative analysis

Narrative analysis is an examination of the story elements, including narrative structure, character, and plot. This type of analysis considers the entirety of the film and the story it seeks to tell.

For example, you could take the same object from the previous example—the flowers—which meant one thing in a semiotic analysis, and ask instead about their narrative role. That is, you might analyze how Hitchcock introduces the flowers at the beginning of the film in order to return to them later to draw out the completion of the heroine’s character arc.

To create this type of analysis, you could consider questions like:

- How does the film correspond to the Three-Act Structure: Act One: Setup; Act Two: Confrontation; and Act Three: Resolution?

- What is the plot of the film? How does this plot differ from the narrative, that is, how the story is told? For example, are events presented out of order and to what effect?

- Does the plot revolve around one character? Does the plot revolve around multiple characters? How do these characters develop across the film?

When writing a narrative analysis, take care not to spend too time on summarizing at the expense of your argument. See our handout on summarizing for more tips on making summary serve analysis.

Cultural/historical analysis

One of the most common types of analysis is the examination of a film’s relationship to its broader cultural, historical, or theoretical contexts. Whether films intentionally comment on their context or not, they are always a product of the culture or period in which they were created. By placing the film in a particular context, this type of analysis asks how the film models, challenges, or subverts different types of relations, whether historical, social, or even theoretical.

For example, the clip from Vertigo depicts a man observing a woman without her knowing it. You could examine how this aspect of the film addresses a midcentury social concern about observation, such as the sexual policing of women, or a political one, such as Cold War-era McCarthyism.

A few of the many questions you could ask in this vein include:

- How does the film comment on, reinforce, or even critique social and political issues at the time it was released, including questions of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality?

- How might a biographical understanding of the film’s creators and their historical moment affect the way you view the film?

- How might a specific film theory, such as Queer Theory, Structuralist Theory, or Marxist Film Theory, provide a language or set of terms for articulating the attributes of the film?

Take advantage of class resources to explore possible approaches to cultural/historical film analyses, and find out whether you will be expected to do additional research into the film’s context.

Mise-en-scène analysis

A mise-en-scène analysis attends to how the filmmakers have arranged compositional elements in a film and specifically within a scene or even a single shot. This type of analysis organizes the individual elements of a scene to explore how they come together to produce meaning. You may focus on anything that adds meaning to the formal effect produced by a given scene, including: blocking, lighting, design, color, costume, as well as how these attributes work in conjunction with decisions related to sound, cinematography, and editing. For example, in the clip from Vertigo , a mise-en-scène analysis might ask how numerous elements, from lighting to camera angles, work together to present the viewer with the perspective of Jimmy Stewart’s character.

To conduct this type of analysis, you could ask:

- What effects are created in a scene, and what is their purpose?

- How does this scene represent the theme of the movie?

- How does a scene work to express a broader point to the film’s plot?

This detailed approach to analyzing the formal elements of film can help you come up with concrete evidence for more general film analysis assignments.

Reviewing your draft

Once you have a draft, it’s helpful to get feedback on what you’ve written to see if your analysis holds together and you’ve conveyed your point. You may not necessarily need to find someone who has seen the film! Ask a writing coach, roommate, or family member to read over your draft and share key takeaways from what you have written so far.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Aumont, Jacques, and Michel Marie. 1988. L’analyse Des Films . Paris: Nathan.

Media & Design Center. n.d. “Film and Cinema Research.” UNC University Libraries. Last updated February 10, 2021. https://guides.lib.unc.edu/filmresearch .

Oxford Royale Academy. n.d. “7 Ways to Watch Film.” Oxford Royale Academy. Accessed April 2021. https://www.oxford-royale.com/articles/7-ways-watch-films-critically/ .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Presidential Search

- Editor's Pick

Former Defense Department General Counsel Appointed Harvard’s Top Lawyer

Democracy Center Protesters Stage ‘Emergency Rally’ with Pro-Palestine Activists Amid Occupation

Harvard Violated Contract With HGSU in Excluding Some Grad Students, Arbitrator Rules

House Committee on China to Probe Harvard’s Handling of Anti-CCP Protest at HKS

Harvard Republican Club Endorses Donald Trump in 2024 Presidential Election

Pixar's 'Soul’ Offers a Thesis on the Meaning of Life, and It’s a Pretty Good One

Dir. pete docter––4.5 stars.

There are technically no rules against an animated film winning the Academy Award for Best Picture. In the 93-year history of the Oscars, however, only three have ever received a nomination (“Beauty and the Beast,” “Up,” and “Toy Story 3”), and none have ever won. When “Wall-E” wasn’t nominated in 2008, critics began to raise questions about whether the existence of the separate “Best Animated Feature” category was inherently harmful — an implicitly degrading statement that animated films must be judged by different standards than live-action ones.

This, in some ways, is besides the point; to delve into a discussion of the Academy’s inner machinations would probably make this review about 20 times longer. But the “Best Animated Feature” category is, in many ways, symptomatic of the way many Americans view animation: as a genre, rather than as a medium. The way we associate animation with fart jokes and cheesy endings makes it difficult to think broader, to produce something mature and thoughtful like “Spirited Away” or “Your Name” — leaving us to define animated movies as “just for kids”

Pixar’s “Soul,” however, blows this definition out of the water.

The film follows Joe Gardner (Jamie Foxx), a middle-school band teacher who’s always dreamed of being a professional jazz pianist. On the day he finally gets his big break — literally moments after being offered the chance to play with one of the jazz greats — he falls into an open manhole and, well, dies.

What follows is a bit less realistic. Instead of proceeding to The Great Beyond like all the other souls, Joe (now an ethereal, glowing, light teal-colored soul) flees to The Great Before — the fantastical celestial plane where new souls get their personalities before proceeding to Earth. There, he meets 22 (Tina Fey), a petulant, jaded new soul who’s not all that jazzed about going to Earth, and together, they devise a plan to return Joe to his earthly body in time for his big gig.

Much like in “Inside Out” (another brainchild of director and Pixar Chief Creative Officer Pete Docter), the far-fetched premise of “Soul” is balanced by how grounded it is in the human condition. It’s okay, for instance, that Joe’s soul inhabits a therapy cat named Mr. Mittens for a good chunk of the second act, because this ultimately allows 22 to recognize the true meaning of life on Earth. And the slapstick is kept to a minimum — replaced with humor that is either very clever or uncannily mature (“Can’t crush a soul here,” 22 says as a building collapses onto a group of new souls in The Great Before. “That’s what life on Earth is for”).