The Five Steps of Writing an Essay

Mastering these steps will make your words more compelling

- Tips For Adult Students

- Getting Your Ged

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Deb-Nov2015-5895870e3df78caebc88766f.jpg)

- B.A., English, St. Olaf College

Knowing how to write an essay is a skill that you can use throughout your life. The ability to organize ideas that you use in constructing an essay will help you write business letters, company memos, and marketing materials for your clubs and organizations.

Anything you write will benefit from learning these simple parts of an essay:

- Purpose and Thesis

Introduction

Body of information.

Here are five steps to make it happen:

Purpose/Main Idea

Echo / Cultura / Getty Images

Before you can start writing, you must have an idea to write about. If you haven't been assigned a topic, it's easier than you might think to come up with one of your own.

Your best essays will be about things that light your fire. What do you feel passionate about? What topics do you find yourself arguing for or against? Choose the side of the topic you are "for" rather than "against" and your essay will be stronger.

Do you love gardening? Sports? Photography? Volunteering? Are you an advocate for children? Domestic peace? The hungry or homeless? These are clues to your best essays.

Put your idea into a single sentence. This is your thesis statement , your main idea.

STOCK4B-RF / Getty Images

Choose a title for your essay that expresses your primary idea. The strongest titles will include a verb. Take a look at any newspaper and you'll see that every title has a verb.

Your title should make someone want to read what you have to say. Make it provocative.

Here are a few ideas:

- America Needs Better Health Care Now

- The Use of the Mentor Archetype in _____

- Who Is the She-Conomy?

- Why DJ Is the Queen of Pedicures

- Melanoma: Is It or Isn't It?

- How to Achieve Natural Balance in Your Garden

- Expect to Be Changed by Reading _____

Some people will tell you to wait until you have finished writing to choose a title. Other people find that writing a title helps them stay focused. You can always review your title when you've finished the essay to ensure that it's as effective as it can be.

Hero-Images / Getty Images

Your introduction is one short paragraph, just a sentence or two, that states your thesis (your main idea) and introduces your reader to your topic. After your title, this is your next best chance to hook your reader. Here are some examples:

- Women are the chief buyers in 80 percent of America's households. If you're not marketing to them, you should be.

- Take another look at that spot on your arm. Is the shape irregular? Is it multicolored? You could have melanoma. Know the signs.

- Those tiny wasps flying around the blossoms in your garden can't sting you. Their stingers have evolved into egg-laying devices. The wasps, busying finding a place to lay their eggs, are participating in the balance of nature.

Vincent Hazat / PhotoAlto Agency RF Collections / Getty Images

The body of your essay is where you develop your story or argument. Once you have finished your research and produced several pages of notes, go through them with a highlighter and mark the most important ideas, the key points.

Choose the top three ideas and write each one at the top of a clean page. Now go through your notes again and pull out supporting ideas for each key point. You don't need a lot, just two or three for each one.

Write a paragraph about each of these key points, using the information you've pulled from your notes. If you don't have enough for one, you might need a stronger key point. Do more research to support your point of view. It's always better to have too many sources than too few.

Anna Bryukhanova/E Plus / Getty Images

You've almost finished. The last paragraph of your essay is your conclusion. It, too, can be short, and it must tie back to your introduction.

In your introduction, you stated the reason for your paper. In your conclusion, you should summarize how your key points support your thesis. Here's an example:

- By observing the balance of nature in her gardens, listening to lectures, and reading everything she can get her hands on about insects and native plants, Lucinda has grown passionate about natural balance. "It's easy to get passionate if you just take time to look," she says.

If you're still worried about your essay after trying on your own, consider hiring an essay editing service. Reputable services will edit your work, not rewrite it. Choose carefully. One service to consider is Essay Edge .

Good luck! The next essay will be easier.

- 100 Persuasive Essay Topics

- Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

- How to Structure an Essay

- How To Write an Essay

- 6 Steps to Writing the Perfect Personal Essay

- How to Write a Research Paper That Earns an A

- Tips for Writing an Art History Paper

- What Is Expository Writing?

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- Development in Composition: Building an Essay

- How to Write a Great College Application Essay Title

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- How to Write a Great Essay for the TOEFL or TOEIC

- How to Write a Persuasive Essay

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- Enroll & Pay

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

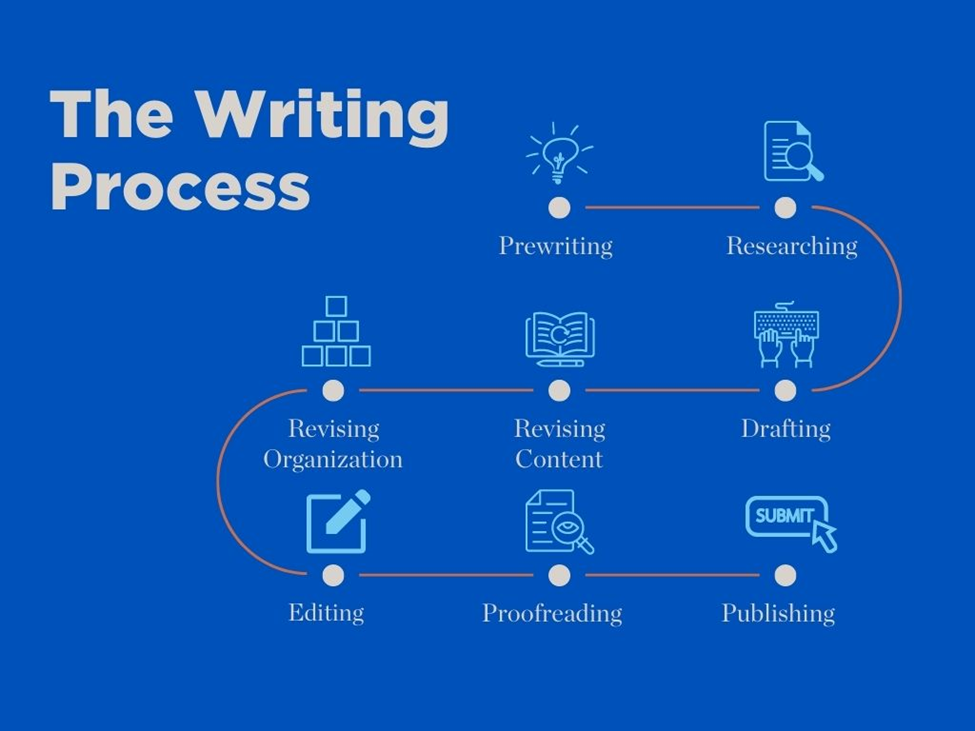

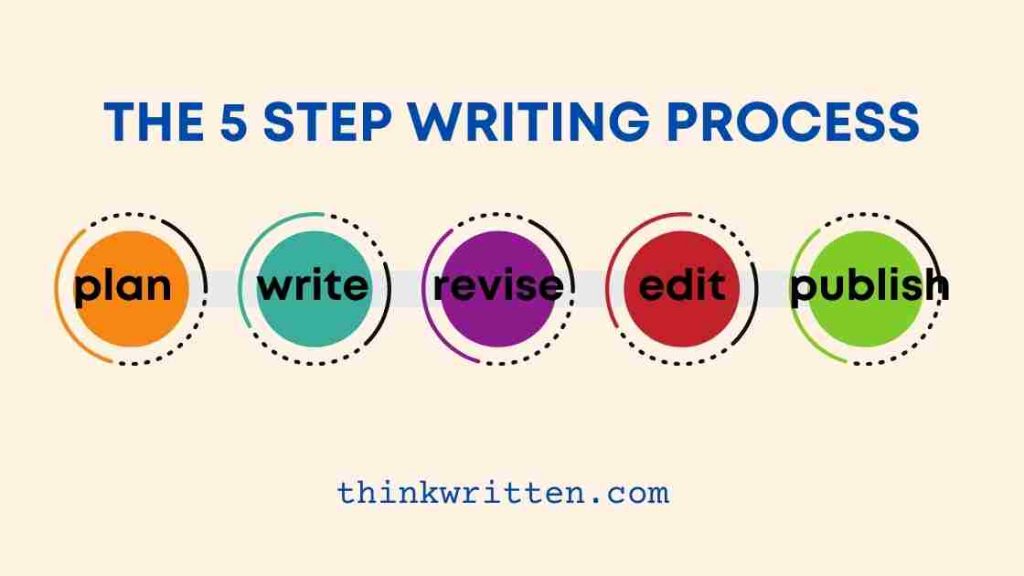

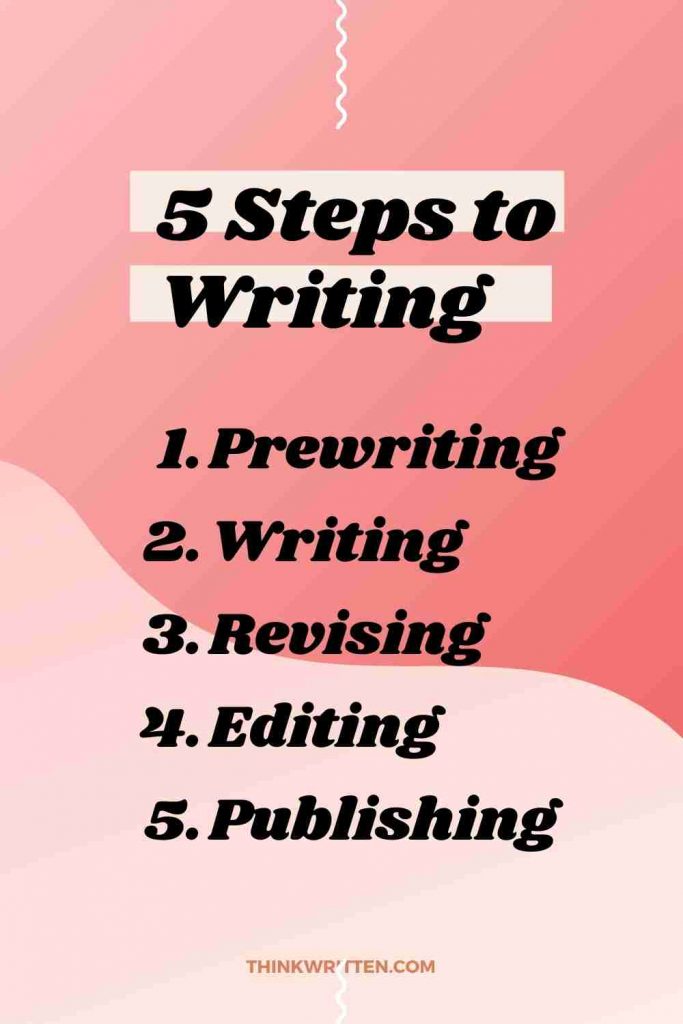

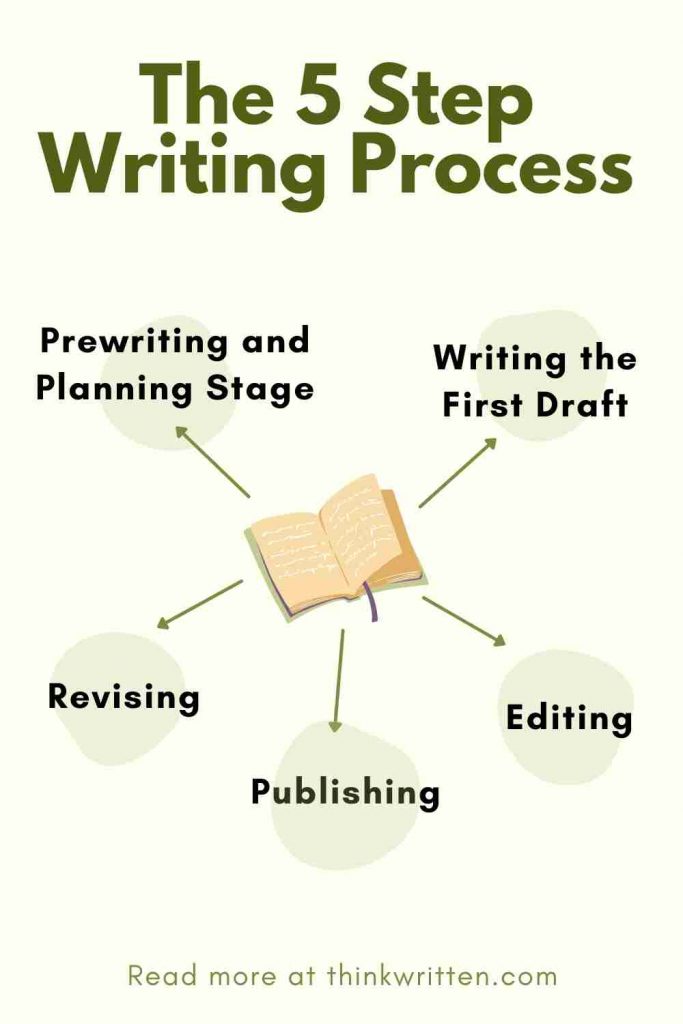

The Writing Process

The writing process is something that no two people do the same way. There is no "right way" or "wrong way" to write. It can be a very messy and fluid process, and the following is only a representation of commonly used steps. Remember you can come to the Writing Center for assistance at any stage in this process.

Steps of the Writing Process

Step 1: Prewriting

Think and Decide

- Make sure you understand your assignment. See Research Papers or Essays

- Decide on a topic to write about. See Prewriting Strategies and Narrow your Topic

- Consider who will read your work. See Audience and Voice

- Brainstorm ideas about the subject and how those ideas can be organized. Make an outline. See Outlines

Step 2: Research (if needed)

- List places where you can find information.

- Do your research. See the many KU Libraries resources and helpful guides

- Evaluate your sources. See Evaluating Sources and Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Make an outline to help organize your research. See Outlines

Step 3: Drafting

- Write sentences and paragraphs even if they are not perfect.

- Create a thesis statement with your main idea. See Thesis Statements

- Put the information you researched into your essay accurately without plagiarizing. Remember to include both in-text citations and a bibliographic page. See Incorporating References and Paraphrase and Summary

- Read what you have written and judge if it says what you mean. Write some more.

- Read it again.

- Write some more.

- Write until you have said everything you want to say about the topic.

Step 4: Revising

Make it Better

- Read what you have written again. See Revising Content and Revising Organization

- Rearrange words, sentences, or paragraphs into a clear and logical order.

- Take out or add parts.

- Do more research if you think you should.

- Replace overused or unclear words.

- Read your writing aloud to be sure it flows smoothly. Add transitions.

Step 5: Editing and Proofreading

Make it Correct

- Be sure all sentences are complete. See Editing and Proofreading

- Correct spelling, capitalization, and punctuation.

- Change words that are not used correctly or are unclear.

- APA Formatting

- Chicago Style Formatting

- MLA Formatting

- Have someone else check your work.

How to Write an Essay

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Essay Writing Fundamentals

How to prepare to write an essay, how to edit an essay, how to share and publish your essays, how to get essay writing help, how to find essay writing inspiration, resources for teaching essay writing.

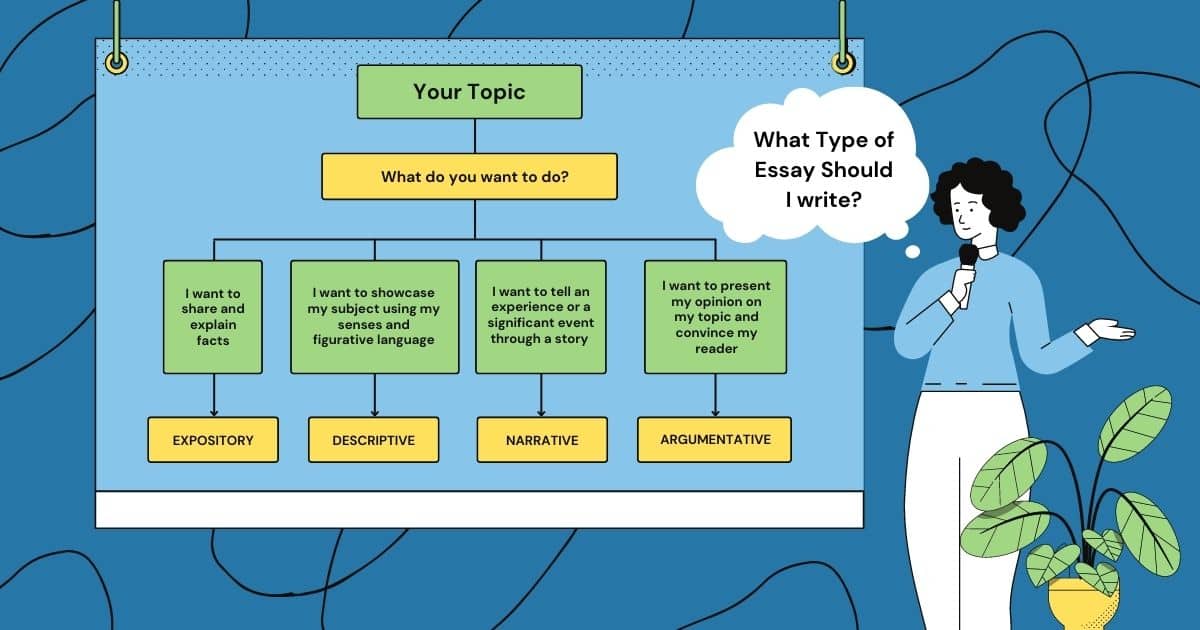

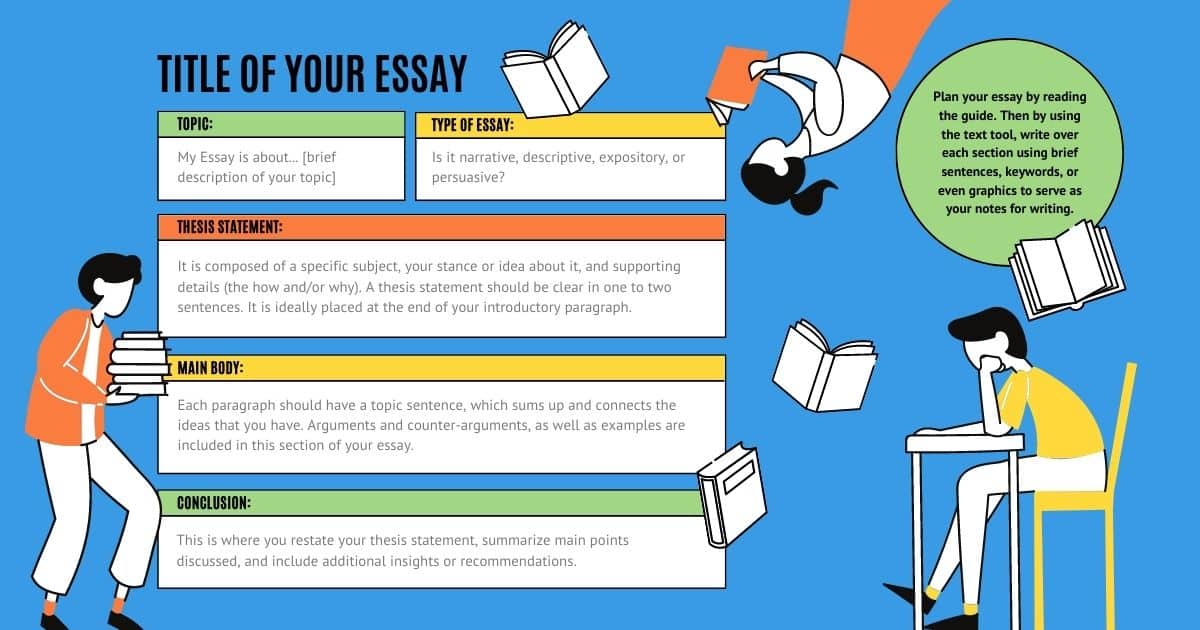

Essays, short prose compositions on a particular theme or topic, are the bread and butter of academic life. You write them in class, for homework, and on standardized tests to show what you know. Unlike other kinds of academic writing (like the research paper) and creative writing (like short stories and poems), essays allow you to develop your original thoughts on a prompt or question. Essays come in many varieties: they can be expository (fleshing out an idea or claim), descriptive, (explaining a person, place, or thing), narrative (relating a personal experience), or persuasive (attempting to win over a reader). This guide is a collection of dozens of links about academic essay writing that we have researched, categorized, and annotated in order to help you improve your essay writing.

Essays are different from other forms of writing; in turn, there are different kinds of essays. This section contains general resources for getting to know the essay and its variants. These resources introduce and define the essay as a genre, and will teach you what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab

One of the most trusted academic writing sites, Purdue OWL provides a concise introduction to the four most common types of academic essays.

"The Essay: History and Definition" (ThoughtCo)

This snappy article from ThoughtCo talks about the origins of the essay and different kinds of essays you might be asked to write.

"What Is An Essay?" Video Lecture (Coursera)

The University of California at Irvine's free video lecture, available on Coursera, tells you everything you need to know about the essay.

Wikipedia Article on the "Essay"

Wikipedia's article on the essay is comprehensive, providing both English-language and global perspectives on the essay form. Learn about the essay's history, forms, and styles.

"Understanding College and Academic Writing" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This list of common academic writing assignments (including types of essay prompts) will help you know what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Before you start writing your essay, you need to figure out who you're writing for (audience), what you're writing about (topic/theme), and what you're going to say (argument and thesis). This section contains links to handouts, chapters, videos and more to help you prepare to write an essay.

How to Identify Your Audience

"Audience" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This handout provides questions you can ask yourself to determine the audience for an academic writing assignment. It also suggests strategies for fitting your paper to your intended audience.

"Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

This extensive book chapter from Writing for Success , available online through Minnesota Libraries Publishing, is followed by exercises to try out your new pre-writing skills.

"Determining Audience" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This guide from a community college's writing center shows you how to know your audience, and how to incorporate that knowledge in your thesis statement.

"Know Your Audience" ( Paper Rater Blog)

This short blog post uses examples to show how implied audiences for essays differ. It reminds you to think of your instructor as an observer, who will know only the information you pass along.

How to Choose a Theme or Topic

"Research Tutorial: Developing Your Topic" (YouTube)

Take a look at this short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to understand the basics of developing a writing topic.

"How to Choose a Paper Topic" (WikiHow)

This simple, step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through choosing a paper topic. It starts with a detailed description of brainstorming and ends with strategies to refine your broad topic.

"How to Read an Assignment: Moving From Assignment to Topic" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Did your teacher give you a prompt or other instructions? This guide helps you understand the relationship between an essay assignment and your essay's topic.

"Guidelines for Choosing a Topic" (CliffsNotes)

This study guide from CliffsNotes both discusses how to choose a topic and makes a useful distinction between "topic" and "thesis."

How to Come Up with an Argument

"Argument" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

Not sure what "argument" means in the context of academic writing? This page from the University of North Carolina is a good place to start.

"The Essay Guide: Finding an Argument" (Study Hub)

This handout explains why it's important to have an argument when beginning your essay, and provides tools to help you choose a viable argument.

"Writing a Thesis and Making an Argument" (University of Iowa)

This page from the University of Iowa's Writing Center contains exercises through which you can develop and refine your argument and thesis statement.

"Developing a Thesis" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page from Harvard's Writing Center collates some helpful dos and don'ts of argumentative writing, from steps in constructing a thesis to avoiding vague and confrontational thesis statements.

"Suggestions for Developing Argumentative Essays" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

This page offers concrete suggestions for each stage of the essay writing process, from topic selection to drafting and editing.

How to Outline your Essay

"Outlines" (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill via YouTube)

This short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill shows how to group your ideas into paragraphs or sections to begin the outlining process.

"Essay Outline" (Univ. of Washington Tacoma)

This two-page handout by a university professor simply defines the parts of an essay and then organizes them into an example outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL gives examples of diverse outline strategies on this page, including the alphanumeric, full sentence, and decimal styles.

"Outlining" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Once you have an argument, according to this handout, there are only three steps in the outline process: generalizing, ordering, and putting it all together. Then you're ready to write!

"Writing Essays" (Plymouth Univ.)

This packet, part of Plymouth University's Learning Development series, contains descriptions and diagrams relating to the outlining process.

"How to Write A Good Argumentative Essay: Logical Structure" (Criticalthinkingtutorials.com via YouTube)

This longer video tutorial gives an overview of how to structure your essay in order to support your argument or thesis. It is part of a longer course on academic writing hosted on Udemy.

Now that you've chosen and refined your topic and created an outline, use these resources to complete the writing process. Most essays contain introductions (which articulate your thesis statement), body paragraphs, and conclusions. Transitions facilitate the flow from one paragraph to the next so that support for your thesis builds throughout the essay. Sources and citations show where you got the evidence to support your thesis, which ensures that you avoid plagiarism.

How to Write an Introduction

"Introductions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page identifies the role of the introduction in any successful paper, suggests strategies for writing introductions, and warns against less effective introductions.

"How to Write A Good Introduction" (Michigan State Writing Center)

Beginning with the most common missteps in writing introductions, this guide condenses the essentials of introduction composition into seven points.

"The Introductory Paragraph" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming focuses on ways to grab your reader's attention at the beginning of your essay.

"Introductions and Conclusions" (Univ. of Toronto)

This guide from the University of Toronto gives advice that applies to writing both introductions and conclusions, including dos and don'ts.

"How to Write Better Essays: No One Does Introductions Properly" ( The Guardian )

This news article interviews UK professors on student essay writing; they point to introductions as the area that needs the most improvement.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

"Writing an Effective Thesis Statement" (YouTube)

This short, simple video tutorial from a college composition instructor at Tulsa Community College explains what a thesis statement is and what it does.

"Thesis Statement: Four Steps to a Great Essay" (YouTube)

This fantastic tutorial walks you through drafting a thesis, using an essay prompt on Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter as an example.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through coming up with, writing, and editing a thesis statement. It invites you think of your statement as a "working thesis" that can change.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (Univ. of Indiana Bloomington)

Ask yourself the questions on this page, part of Indiana Bloomington's Writing Tutorial Services, when you're writing and refining your thesis statement.

"Writing Tips: Thesis Statements" (Univ. of Illinois Center for Writing Studies)

This page gives plentiful examples of good to great thesis statements, and offers questions to ask yourself when formulating a thesis statement.

How to Write Body Paragraphs

"Body Paragraph" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course introduces you to the components of a body paragraph. These include the topic sentence, information, evidence, and analysis.

"Strong Body Paragraphs" (Washington Univ.)

This handout from Washington's Writing and Research Center offers in-depth descriptions of the parts of a successful body paragraph.

"Guide to Paragraph Structure" (Deakin Univ.)

This handout is notable for color-coding example body paragraphs to help you identify the functions various sentences perform.

"Writing Body Paragraphs" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

The exercises in this section of Writing for Success will help you practice writing good body paragraphs. It includes guidance on selecting primary support for your thesis.

"The Writing Process—Body Paragraphs" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

The information and exercises on this page will familiarize you with outlining and writing body paragraphs, and includes links to more information on topic sentences and transitions.

"The Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post discusses body paragraphs in the context of one of the most common academic essay types in secondary schools.

How to Use Transitions

"Transitions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill explains what a transition is, and how to know if you need to improve your transitions.

"Using Transitions Effectively" (Washington Univ.)

This handout defines transitions, offers tips for using them, and contains a useful list of common transitional words and phrases grouped by function.

"Transitions" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This page compares paragraphs without transitions to paragraphs with transitions, and in doing so shows how important these connective words and phrases are.

"Transitions in Academic Essays" (Scribbr)

This page lists four techniques that will help you make sure your reader follows your train of thought, including grouping similar information and using transition words.

"Transitions" (El Paso Community College)

This handout shows example transitions within paragraphs for context, and explains how transitions improve your essay's flow and voice.

"Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post, another from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming, talks about transitions and other strategies to improve your essay's overall flow.

"Transition Words" (smartwords.org)

This handy word bank will help you find transition words when you're feeling stuck. It's grouped by the transition's function, whether that is to show agreement, opposition, condition, or consequence.

How to Write a Conclusion

"Parts of An Essay: Conclusions" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course explains how to conclude an academic essay. It suggests thinking about the "3Rs": return to hook, restate your thesis, and relate to the reader.

"Essay Conclusions" (Univ. of Maryland University College)

This overview of the academic essay conclusion contains helpful examples and links to further resources for writing good conclusions.

"How to End An Essay" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) by an English Ph.D. walks you through writing a conclusion, from brainstorming to ending with a flourish.

"Ending the Essay: Conclusions" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page collates useful strategies for writing an effective conclusion, and reminds you to "close the discussion without closing it off" to further conversation.

How to Include Sources and Citations

"Research and Citation Resources" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL streamlines information about the three most common referencing styles (MLA, Chicago, and APA) and provides examples of how to cite different resources in each system.

EasyBib: Free Bibliography Generator

This online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style. Be sure to select your resource type before clicking the "cite it" button.

CitationMachine

Like EasyBib, this online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style.

Modern Language Association Handbook (MLA)

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of MLA referencing rules. Order through the link above, or check to see if your library has a copy.

Chicago Manual of Style

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of Chicago referencing rules. You can take a look at the table of contents, then choose to subscribe or start a free trial.

How to Avoid Plagiarism

"What is Plagiarism?" (plagiarism.org)

This nonprofit website contains numerous resources for identifying and avoiding plagiarism, and reminds you that even common activities like copying images from another website to your own site may constitute plagiarism.

"Plagiarism" (University of Oxford)

This interactive page from the University of Oxford helps you check for plagiarism in your work, making it clear how to avoid citing another person's work without full acknowledgement.

"Avoiding Plagiarism" (MIT Comparative Media Studies)

This quick guide explains what plagiarism is, what its consequences are, and how to avoid it. It starts by defining three words—quotation, paraphrase, and summary—that all constitute citation.

"Harvard Guide to Using Sources" (Harvard Extension School)

This comprehensive website from Harvard brings together articles, videos, and handouts about referencing, citation, and plagiarism.

Grammarly contains tons of helpful grammar and writing resources, including a free tool to automatically scan your essay to check for close affinities to published work.

Noplag is another popular online tool that automatically scans your essay to check for signs of plagiarism. Simply copy and paste your essay into the box and click "start checking."

Once you've written your essay, you'll want to edit (improve content), proofread (check for spelling and grammar mistakes), and finalize your work until you're ready to hand it in. This section brings together tips and resources for navigating the editing process.

"Writing a First Draft" (Academic Help)

This is an introduction to the drafting process from the site Academic Help, with tips for getting your ideas on paper before editing begins.

"Editing and Proofreading" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page provides general strategies for revising your writing. They've intentionally left seven errors in the handout, to give you practice in spotting them.

"How to Proofread Effectively" (ThoughtCo)

This article from ThoughtCo, along with those linked at the bottom, help describe common mistakes to check for when proofreading.

"7 Simple Edits That Make Your Writing 100% More Powerful" (SmartBlogger)

This blog post emphasizes the importance of powerful, concise language, and reminds you that even your personal writing heroes create clunky first drafts.

"Editing Tips for Effective Writing" (Univ. of Pennsylvania)

On this page from Penn's International Relations department, you'll find tips for effective prose, errors to watch out for, and reminders about formatting.

"Editing the Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, the first of two parts, gives you applicable strategies for the editing process. It suggests reading your essay aloud, removing any jargon, and being unafraid to remove even "dazzling" sentences that don't belong.

"Guide to Editing and Proofreading" (Oxford Learning Institute)

This handout from Oxford covers the basics of editing and proofreading, and reminds you that neither task should be rushed.

In addition to plagiarism-checkers, Grammarly has a plug-in for your web browser that checks your writing for common mistakes.

After you've prepared, written, and edited your essay, you might want to share it outside the classroom. This section alerts you to print and web opportunities to share your essays with the wider world, from online writing communities and blogs to published journals geared toward young writers.

Sharing Your Essays Online

Go Teen Writers

Go Teen Writers is an online community for writers aged 13 - 19. It was founded by Stephanie Morrill, an author of contemporary young adult novels.

Tumblr is a blogging website where you can share your writing and interact with other writers online. It's easy to add photos, links, audio, and video components.

Writersky provides an online platform for publishing and reading other youth writers' work. Its current content is mostly devoted to fiction.

Publishing Your Essays Online

This teen literary journal publishes in print, on the web, and (more frequently), on a blog. It is committed to ensuring that "teens see their authentic experience reflected on its pages."

The Matador Review

This youth writing platform celebrates "alternative," unconventional writing. The link above will take you directly to the site's "submissions" page.

Teen Ink has a website, monthly newsprint magazine, and quarterly poetry magazine promoting the work of young writers.

The largest online reading platform, Wattpad enables you to publish your work and read others' work. Its inline commenting feature allows you to share thoughts as you read along.

Publishing Your Essays in Print

Canvas Teen Literary Journal

This quarterly literary magazine is published for young writers by young writers. They accept many kinds of writing, including essays.

The Claremont Review

This biannual international magazine, first published in 1992, publishes poetry, essays, and short stories from writers aged 13 - 19.

Skipping Stones

This young writers magazine, founded in 1988, celebrates themes relating to ecological and cultural diversity. It publishes poems, photos, articles, and stories.

The Telling Room

This nonprofit writing center based in Maine publishes children's work on their website and in book form. The link above directs you to the site's submissions page.

Essay Contests

Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards

This prestigious international writing contest for students in grades 7 - 12 has been committed to "supporting the future of creativity since 1923."

Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest

An annual essay contest on the theme of journalism and media, the Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest awards scholarships up to $1,000.

National YoungArts Foundation

Here, you'll find information on a government-sponsored writing competition for writers aged 15 - 18. The foundation welcomes submissions of creative nonfiction, novels, scripts, poetry, short story and spoken word.

Signet Classics Student Scholarship Essay Contest

With prompts on a different literary work each year, this competition from Signet Classics awards college scholarships up to $1,000.

"The Ultimate Guide to High School Essay Contests" (CollegeVine)

See this handy guide from CollegeVine for a list of more competitions you can enter with your academic essay, from the National Council of Teachers of English Achievement Awards to the National High School Essay Contest by the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Whether you're struggling to write academic essays or you think you're a pro, there are workshops and online tools that can help you become an even better writer. Even the most seasoned writers encounter writer's block, so be proactive and look through our curated list of resources to combat this common frustration.

Online Essay-writing Classes and Workshops

"Getting Started with Essay Writing" (Coursera)

Coursera offers lots of free, high-quality online classes taught by college professors. Here's one example, taught by instructors from the University of California Irvine.

"Writing and English" (Brightstorm)

Brightstorm's free video lectures are easy to navigate by topic. This unit on the parts of an essay features content on the essay hook, thesis, supporting evidence, and more.

"How to Write an Essay" (EdX)

EdX is another open online university course website with several two- to five-week courses on the essay. This one is geared toward English language learners.

Writer's Digest University

This renowned writers' website offers online workshops and interactive tutorials. The courses offered cover everything from how to get started through how to get published.

Writing.com

Signing up for this online writer's community gives you access to helpful resources as well as an international community of writers.

How to Overcome Writer's Block

"Symptoms and Cures for Writer's Block" (Purdue OWL)

Purdue OWL offers a list of signs you might have writer's block, along with ways to overcome it. Consider trying out some "invention strategies" or ways to curb writing anxiety.

"Overcoming Writer's Block: Three Tips" ( The Guardian )

These tips, geared toward academic writing specifically, are practical and effective. The authors advocate setting realistic goals, creating dedicated writing time, and participating in social writing.

"Writing Tips: Strategies for Overcoming Writer's Block" (Univ. of Illinois)

This page from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Center for Writing Studies acquaints you with strategies that do and do not work to overcome writer's block.

"Writer's Block" (Univ. of Toronto)

Ask yourself the questions on this page; if the answer is "yes," try out some of the article's strategies. Each question is accompanied by at least two possible solutions.

If you have essays to write but are short on ideas, this section's links to prompts, example student essays, and celebrated essays by professional writers might help. You'll find writing prompts from a variety of sources, student essays to inspire you, and a number of essay writing collections.

Essay Writing Prompts

"50 Argumentative Essay Topics" (ThoughtCo)

Take a look at this list and the others ThoughtCo has curated for different kinds of essays. As the author notes, "a number of these topics are controversial and that's the point."

"401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing" ( New York Times )

This list (and the linked lists to persuasive and narrative writing prompts), besides being impressive in length, is put together by actual high school English teachers.

"SAT Sample Essay Prompts" (College Board)

If you're a student in the U.S., your classroom essay prompts are likely modeled on the prompts in U.S. college entrance exams. Take a look at these official examples from the SAT.

"Popular College Application Essay Topics" (Princeton Review)

This page from the Princeton Review dissects recent Common Application essay topics and discusses strategies for answering them.

Example Student Essays

"501 Writing Prompts" (DePaul Univ.)

This nearly 200-page packet, compiled by the LearningExpress Skill Builder in Focus Writing Team, is stuffed with writing prompts, example essays, and commentary.

"Topics in English" (Kibin)

Kibin is a for-pay essay help website, but its example essays (organized by topic) are available for free. You'll find essays on everything from A Christmas Carol to perseverance.

"Student Writing Models" (Thoughtful Learning)

Thoughtful Learning, a website that offers a variety of teaching materials, provides sample student essays on various topics and organizes them by grade level.

"Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

In this blog post by a former professor of English and rhetoric, ThoughtCo brings together examples of five-paragraph essays and commentary on the form.

The Best Essay Writing Collections

The Best American Essays of the Century by Joyce Carol Oates (Amazon)

This collection of American essays spanning the twentieth century was compiled by award winning author and Princeton professor Joyce Carol Oates.

The Best American Essays 2017 by Leslie Jamison (Amazon)

Leslie Jamison, the celebrated author of essay collection The Empathy Exams , collects recent, high-profile essays into a single volume.

The Art of the Personal Essay by Phillip Lopate (Amazon)

Documentary writer Phillip Lopate curates this historical overview of the personal essay's development, from the classical era to the present.

The White Album by Joan Didion (Amazon)

This seminal essay collection was authored by one of the most acclaimed personal essayists of all time, American journalist Joan Didion.

Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace (Amazon)

Read this famous essay collection by David Foster Wallace, who is known for his experimentation with the essay form. He pushed the boundaries of personal essay, reportage, and political polemic.

"50 Successful Harvard Application Essays" (Staff of the The Harvard Crimson )

If you're looking for examples of exceptional college application essays, this volume from Harvard's daily student newspaper is one of the best collections on the market.

Are you an instructor looking for the best resources for teaching essay writing? This section contains resources for developing in-class activities and student homework assignments. You'll find content from both well-known university writing centers and online writing labs.

Essay Writing Classroom Activities for Students

"In-class Writing Exercises" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page lists exercises related to brainstorming, organizing, drafting, and revising. It also contains suggestions for how to implement the suggested exercises.

"Teaching with Writing" (Univ. of Minnesota Center for Writing)

Instructions and encouragement for using "freewriting," one-minute papers, logbooks, and other write-to-learn activities in the classroom can be found here.

"Writing Worksheets" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

Berkeley offers this bank of writing worksheets to use in class. They are nested under headings for "Prewriting," "Revision," "Research Papers" and more.

"Using Sources and Avoiding Plagiarism" (DePaul University)

Use these activities and worksheets from DePaul's Teaching Commons when instructing students on proper academic citation practices.

Essay Writing Homework Activities for Students

"Grammar and Punctuation Exercises" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

These five interactive online activities allow students to practice editing and proofreading. They'll hone their skills in correcting comma splices and run-ons, identifying fragments, using correct pronoun agreement, and comma usage.

"Student Interactives" (Read Write Think)

Read Write Think hosts interactive tools, games, and videos for developing writing skills. They can practice organizing and summarizing, writing poetry, and developing lines of inquiry and analysis.

This free website offers writing and grammar activities for all grade levels. The lessons are designed to be used both for large classes and smaller groups.

"Writing Activities and Lessons for Every Grade" (Education World)

Education World's page on writing activities and lessons links you to more free, online resources for learning how to "W.R.I.T.E.": write, revise, inform, think, and edit.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1956 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 41,253 quotes across 1956 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, the ultimate blueprint: a research-driven deep dive into the 13 steps of the writing process.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

This article provides a comprehensive, research-based introduction to the major steps , or strategies , that writers work through as they endeavor to communicate with audiences . Since the 1960s, the writing process has been defined to be a series of steps , stages, or strategies. Most simply, the writing process is conceptualized as four major steps: prewriting , drafting , revising , editing . That model works really well for many occasions. Yet sometimes you'll face really challenging writing tasks that will force you to engage in additional steps, including, prewriting , inventing , drafting , collaborating , researching , planning , organizing , designing , rereading , revising , editing , proofreading , sharing or publishing . Expand your composing repertoire -- your ability to respond with authority , clarity , and persuasiveness -- by learning about the dispositions and strategies of successful, professional writers.

Like water cascading to the sea, flow feels inevitable, natural, purposeful. Yet achieving flow is a state of mind that can be difficult to achieve. It requires full commitment to the believing gam e (as opposed to the doubting game ).

What are the Steps of the Writing Process?

Since the 1960s, it has been popular to describe the writing process as a series of steps or stages . For simple projects, the writing process is typically defined as four major steps:

- drafting

This simplified approach to writing is quite appropriate for many exigencies–many calls to write . Often, e.g., we might read an email quickly, write a response, and then send it: write, revise, send.

However, in the real world, for more demanding projects — especially in high-stakes workplace writing or academic writing at the high school and college level — the writing process involve additional steps, or strategies , such as

- collaboration

- researching

- proofreading

- sharing or publishing.

Related Concepts: Mindset ; Self Regulation

Summary – Writing Process Steps

The summary below outlines the major steps writers work through as they endeavor to develop an idea for an audience .

1. Prewriting

Prewriting refers to all the work a writer does on a writing project before they actually begin writing .

Acts of prewriting include

- Prior to writing a first draft, analyze the context for the work. For instance, in school settings students may analyze how much of their grade will be determined by a particular assignment. They may question how many and what sources are required and what the grading criteria will be used for critiquing the work.

- To further their understanding of the assignment, writers will question who the audience is for their work, what their purpose is for writing, what style of writing their audience expects them to employ, and what rhetorical stance is appropriate for them to develop given the rhetorical situation they are addressing. (See the document planner heuristic for more on this)

- consider employing rhetorical appeals ( ethos , pathos , and logos ), rhetorical devices , and rhetorical modes they want to develop once they begin writing

- reflect on the voice , tone , and persona they want to develop

- Following rhetorical analysis and rhetorical reasoning , writers decide on the persona ; point of view ; tone , voice and style of writing they hope to develop, such as an academic writing prose style or a professional writing prose style

- making a plan, an outline, for what to do next.

2. Invention

Invention is traditionally defined as an initial stage of the writing process when writers are more focused on discovery and creative play. During the early stages of a project, writers brainstorm; they explore various topics and perspectives before committing to a specific direction for their discourse .

In practice, invention can be an ongoing concern throughout the writing process. People who are focused on solving problems and developing original ideas, arguments , artifacts, products, services, applications, and texts are open to acts of invention at any time during the writing process.

Writers have many different ways to engage in acts of invention, including

- What is the exigency, the call to write ?

- What are the ongoing scholarly debates in the peer-review literature?

- What is the problem ?

- What do they read? watch? say? What do they know about the topic? Why do they believe what they do? What are their beliefs, values, and expectations ?

- What rhetorical appeals — ethos (credibility) , pathos (emotion) , and logos (logic) — should I explore to develop the best response to this exigency , this call to write?

- What does peer-reviewed research say about the subject?

- What are the current debates about the subject?

- Embrace multiple viewpoints and consider various approaches to encourage the generation of original ideas.

- How can I experiment with different media , genres , writing styles , personas , voices , tone

- Experiment with new research methods

- Write whatever ideas occur to you. Focus on generating ideas as opposed to writing grammatically correct sentences. Get your thoughts down as fully and quickly as you can without critiquing them.

- Use heuristics to inspire discovery and creative thinking: Burke’s Pentad ; Document Planner , Journalistic Questions , The Business Model Canvas

- Embrace the uncertainty that comes with creative exploration.

- Listen to your intuition — your felt sense — when composing

- Experiment with different writing styles , genres , writing tools, and rhetorical stances

- Play the believing game early in the writing process

3. Researching

Research refers to systematic investigations that investigators carry out to discover new knowledge , test knowledge claims , solve problems , or develop new texts , products, apps, and services.

During the research stage of the writing process, writers may engage in

- Engage in customer discovery interviews and survey research in order to better understand the problem space . Use surveys , interviews, focus groups, etc., to understand the stakeholder’s s (e.g., clients, suppliers, partners) problems and needs

- What can you recall from your memory about the subject?

- What can you learn from informal observation?

- What can you learn from strategic searching of the archive on the topic that interests you?

- Who are the thought leaders?

- What were the major turns to the conversation ?

- What are the current debates on the topic ?

- Mixed research methods , qualitative research methods , quantitative research methods , usability and user experience research ?

- What citation style is required by the audience and discourse community you’re addressing? APA | MLA .

4. Collaboration

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others to exchange ideas, solve problems, investigate subjects , coauthor texts , and develop products and services.

Collaboration can play a major role in the writing process, especially when authors coauthor documents with peers and teams , or critique the works of others .

Acts of collaboration include

- Paying close attention to what others are saying, acknowledging their input, and asking clarifying questions to ensure understanding.

- Expressing ideas, thoughts, and opinions in a concise and understandable manner, both verbally and in writing.

- Being receptive to new ideas and perspectives, and considering alternative approaches to problem-solving.

- Adapting to changes in project goals, timelines, or team dynamics, and being willing to modify plans when needed.

- Distributing tasks and responsibilities fairly among team members, and holding oneself accountable for assigned work.

- valuing and appreciating the unique backgrounds, skills, and perspectives of all team members, and leveraging this diversity to enhance collaboration.

- Addressing disagreements or conflicts constructively and diplomatically, working towards mutually beneficial solutions.

- Providing constructive feedback to help others improve their work, and being open to receiving feedback to refine one’s own ideas and contributions.

- Understanding and responding to the emotions, needs, and concerns of team members, and fostering a supportive and inclusive environment .

- Acknowledging and appreciating the achievements of the team and individual members, and using successes as a foundation for continued collaboration and growth.

5. Planning

Planning refers to

- the process of planning how to organize a document

- the process of managing your writing processes

6. Organizing

Following rhetorical analysis , following prewriting , writers question how they should organize their texts. For instance, should they adopt the organizational strategies of academic discourse or workplace-writing discourse ?

Writing-Process Plans

- What is your Purpose? – Aims of Discourse

- What steps, or strategies, need to be completed next?

- set a schedule to complete goals

Planning Exercises

- Document Planner

- Team Charter

7. Designing

Designing refers to efforts on the part of the writer

- to leverage the power of visual language to convey meaning

- to create a visually appealing text

During the designing stage of the writing process, writers explore how they can use the elements of design and visual language to signify , clarify , and simplify the message.

Examples of the designing step of the writing process:

- Establishing a clear hierarchy of visual elements, such as headings, subheadings, and bullet points, to guide the reader’s attention and facilitate understanding.

- Selecting appropriate fonts, sizes, and styles to ensure readability and convey the intended tone and emphasis.

- Organizing text and visual elements on the page or screen in a manner that is visually appealing, easy to navigate, and supports the intended message.

- Using color schemes and contrasts effectively to create a visually engaging experience, while also ensuring readability and accessibility for all readers.

- Incorporating images, illustrations, charts, graphs, and videos to support and enrich the written content, and to convey complex ideas in a more accessible format.

- Designing content that is easily accessible to a wide range of readers, including those with visual impairments, by adhering to accessibility guidelines and best practices.

- Maintaining a consistent style and design throughout the text, which includes the use of visuals, formatting, and typography, to create a cohesive and professional appearance.

- Integrating interactive elements, such as hyperlinks, buttons, and multimedia, to encourage reader engagement and foster deeper understanding of the content.

8. Drafting

Drafting refers to the act of writing a preliminary version of a document — a sloppy first draft. Writers engage in exploratory writing early in the writing process. During drafting, writers focus on freewriting: they write in short bursts of writing without stopping and without concern for grammatical correctness or stylistic matters.

When composing, writers move back and forth between drafting new material, revising drafts, and other steps in the writing process.

9. Rereading

Rereading refers to the process of carefully reviewing a written text. When writers reread texts, they look in between each word, phrase, sentence, paragraph. They look for gaps in content, reasoning, organization, design, diction, style–and more.

When engaged in the physical act of writing — during moments of composing — writers will often pause from drafting to reread what they wrote or to reread some other text they are referencing.

10. Revising

Revision — the process of revisiting, rethinking, and refining written work to improve its content , clarity and overall effectiveness — is such an important part of the writing process that experienced writers often say “writing is revision” or “all writing is revision.”

For many writers, revision processes are deeply intertwined with writing, invention, and reasoning strategies:

- “Writing and rewriting are a constant search for what one is saying.” — John Updike

- “How do I know what I think until I see what I say.” — E.M. Forster

Acts of revision include

- Pivoting: trashing earlier work and moving in a new direction

- Identifying Rhetorical Problems

- Identifying Structural Problems

- Identifying Language Problems

- Identifying Critical & Analytical Thinking Problems

11. Editing

Editing refers to the act of critically reviewing a text with the goal of identifying and rectifying sentence and word-level problems.

When editing , writers tend to focus on local concerns as opposed to global concerns . For instance, they may look for

- problems weaving sources into your argument or analysis

- problems establishing the authority of sources

- problems using the required citation style

- mechanical errors ( capitalization , punctuation , spelling )

- sentence errors , sentence structure errors

- problems with diction , brevity , clarity , flow , inclusivity , register, and simplicity

12. Proofreading

Proofreading refers to last time you’ll look at a document before sharing or publishing the work with its intended audience(s). At this point in the writing process, it’s too late to add in some new evidence you’ve found to support your position. Now you don’t want to add any new content. Instead, your goal during proofreading is to do a final check on word-level errors, problems with diction , punctuation , or syntax.

13. Sharing or Publishing

Sharing refers to the last step in the writing process: the moment when the writer delivers the message — the text — to the target audience .

Writers may think it makes sense to wait to share their work later in the process, after the project is fairly complete. However, that’s not always the case. Sometimes you can save yourself a lot of trouble by bringing in collaborators and critics earlier in the writing process.

Doherty, M. (2016, September 4). 10 things you need to know about banyan trees. Under the Banyan. https://underthebanyan.blog/2016/09/04/10-things-you-need-to-know-about-banyan-trees/

Emig, J. (1967). On teaching composition: Some hypotheses as definitions. Research in The Teaching of English, 1(2), 127-135. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED022783.pdf

Emig, J. (1971). The composing processes of twelfth graders (Research Report No. 13). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Emig, J. (1983). The web of meaning: Essays on writing, teaching, learning and thinking. Upper Montclair, NJ: Boynton/Cook Publishers, Inc.

Ghiselin, B. (Ed.). (1985). The Creative Process: Reflections on the Invention in the Arts and Sciences . University of California Press.

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. (1980). Identifying the Organization of Writing Processes. In L. W. Gregg, & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive Processes in Writing: An Interdisciplinary Approach (pp. 3-30). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hayes, J. R. (2012). Modeling and remodeling writing. Written Communication, 29(3), 369-388. https://doi: 10.1177/0741088312451260

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. S. (1986). Writing research and the writer. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1106-1113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1106

Leijten, Van Waes, L., Schriver, K., & Hayes, J. R. (2014). Writing in the workplace: Constructing documents using multiple digital sources. Journal of Writing Research, 5(3), 285–337. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2014.05.03.3

Lundstrom, K., Babcock, R. D., & McAlister, K. (2023). Collaboration in writing: Examining the role of experience in successful team writing projects. Journal of Writing Research, 15(1), 89-115. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2023.15.01.05

National Research Council. (2012). Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.https://doi.org/10.17226/13398.

North, S. M. (1987). The making of knowledge in composition: Portrait of an emerging field. Boynton/Cook Publishers.

Murray, Donald M. (1980). Writing as process: How writing finds its own meaning. In Timothy R. Donovan & Ben McClelland (Eds.), Eight approaches to teaching composition (pp. 3–20). National Council of Teachers of English.

Murray, Donald M. (1972). “Teach Writing as a Process Not Product.” The Leaflet, 11-14

Perry, S. K. (1996). When time stops: How creative writers experience entry into the flow state (Order No. 9805789). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304288035). https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/when-time-stops-how-creative-writers-experience/docview/304288035/se-2

Rohman, D.G., & Wlecke, A. O. (1964). Pre-writing: The construction and application of models for concept formation in writing (Cooperative Research Project No. 2174). East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.

Rohman, D. G., & Wlecke, A. O. (1975). Pre-writing: The construction and application of models for concept formation in writing (Cooperative Research Project No. 2174). U.S. Office of Education, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Sommers, N. (1980). Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers. College Composition and Communication, 31(4), 378-388. doi: 10.2307/356600

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Recommended

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Structured Revision – How to Revise Your Work

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Research, Speech & Writing

Citation Guide – Learn How to Cite Sources in Academic and Professional Writing

Page Design – How to Design Messages for Maximum Impact

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to structure an essay: Templates and tips

How to Structure an Essay | Tips & Templates

Published on September 18, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

The basic structure of an essay always consists of an introduction , a body , and a conclusion . But for many students, the most difficult part of structuring an essay is deciding how to organize information within the body.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

The basics of essay structure, chronological structure, compare-and-contrast structure, problems-methods-solutions structure, signposting to clarify your structure, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about essay structure.

There are two main things to keep in mind when working on your essay structure: making sure to include the right information in each part, and deciding how you’ll organize the information within the body.

Parts of an essay

The three parts that make up all essays are described in the table below.

| Part | Content |

|---|---|

Order of information

You’ll also have to consider how to present information within the body. There are a few general principles that can guide you here.

The first is that your argument should move from the simplest claim to the most complex . The body of a good argumentative essay often begins with simple and widely accepted claims, and then moves towards more complex and contentious ones.

For example, you might begin by describing a generally accepted philosophical concept, and then apply it to a new topic. The grounding in the general concept will allow the reader to understand your unique application of it.

The second principle is that background information should appear towards the beginning of your essay . General background is presented in the introduction. If you have additional background to present, this information will usually come at the start of the body.

The third principle is that everything in your essay should be relevant to the thesis . Ask yourself whether each piece of information advances your argument or provides necessary background. And make sure that the text clearly expresses each piece of information’s relevance.

The sections below present several organizational templates for essays: the chronological approach, the compare-and-contrast approach, and the problems-methods-solutions approach.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

The chronological approach (sometimes called the cause-and-effect approach) is probably the simplest way to structure an essay. It just means discussing events in the order in which they occurred, discussing how they are related (i.e. the cause and effect involved) as you go.

A chronological approach can be useful when your essay is about a series of events. Don’t rule out other approaches, though—even when the chronological approach is the obvious one, you might be able to bring out more with a different structure.

Explore the tabs below to see a general template and a specific example outline from an essay on the invention of the printing press.

- Thesis statement

- Discussion of event/period

- Consequences

- Importance of topic

- Strong closing statement

- Claim that the printing press marks the end of the Middle Ages

- Background on the low levels of literacy before the printing press

- Thesis statement: The invention of the printing press increased circulation of information in Europe, paving the way for the Reformation

- High levels of illiteracy in medieval Europe

- Literacy and thus knowledge and education were mainly the domain of religious and political elites

- Consequence: this discouraged political and religious change

- Invention of the printing press in 1440 by Johannes Gutenberg

- Implications of the new technology for book production

- Consequence: Rapid spread of the technology and the printing of the Gutenberg Bible

- Trend for translating the Bible into vernacular languages during the years following the printing press’s invention

- Luther’s own translation of the Bible during the Reformation

- Consequence: The large-scale effects the Reformation would have on religion and politics

- Summarize the history described

- Stress the significance of the printing press to the events of this period

Essays with two or more main subjects are often structured around comparing and contrasting . For example, a literary analysis essay might compare two different texts, and an argumentative essay might compare the strengths of different arguments.

There are two main ways of structuring a compare-and-contrast essay: the alternating method, and the block method.

Alternating

In the alternating method, each paragraph compares your subjects in terms of a specific point of comparison. These points of comparison are therefore what defines each paragraph.

The tabs below show a general template for this structure, and a specific example for an essay comparing and contrasting distance learning with traditional classroom learning.

- Synthesis of arguments

- Topical relevance of distance learning in lockdown

- Increasing prevalence of distance learning over the last decade

- Thesis statement: While distance learning has certain advantages, it introduces multiple new accessibility issues that must be addressed for it to be as effective as classroom learning

- Classroom learning: Ease of identifying difficulties and privately discussing them

- Distance learning: Difficulty of noticing and unobtrusively helping

- Classroom learning: Difficulties accessing the classroom (disability, distance travelled from home)

- Distance learning: Difficulties with online work (lack of tech literacy, unreliable connection, distractions)

- Classroom learning: Tends to encourage personal engagement among students and with teacher, more relaxed social environment

- Distance learning: Greater ability to reach out to teacher privately

- Sum up, emphasize that distance learning introduces more difficulties than it solves

- Stress the importance of addressing issues with distance learning as it becomes increasingly common

- Distance learning may prove to be the future, but it still has a long way to go

In the block method, each subject is covered all in one go, potentially across multiple paragraphs. For example, you might write two paragraphs about your first subject and then two about your second subject, making comparisons back to the first.

The tabs again show a general template, followed by another essay on distance learning, this time with the body structured in blocks.

- Point 1 (compare)

- Point 2 (compare)

- Point 3 (compare)

- Point 4 (compare)

- Advantages: Flexibility, accessibility

- Disadvantages: Discomfort, challenges for those with poor internet or tech literacy

- Advantages: Potential for teacher to discuss issues with a student in a separate private call

- Disadvantages: Difficulty of identifying struggling students and aiding them unobtrusively, lack of personal interaction among students

- Advantages: More accessible to those with low tech literacy, equality of all sharing one learning environment

- Disadvantages: Students must live close enough to attend, commutes may vary, classrooms not always accessible for disabled students

- Advantages: Ease of picking up on signs a student is struggling, more personal interaction among students

- Disadvantages: May be harder for students to approach teacher privately in person to raise issues

An essay that concerns a specific problem (practical or theoretical) may be structured according to the problems-methods-solutions approach.

This is just what it sounds like: You define the problem, characterize a method or theory that may solve it, and finally analyze the problem, using this method or theory to arrive at a solution. If the problem is theoretical, the solution might be the analysis you present in the essay itself; otherwise, you might just present a proposed solution.

The tabs below show a template for this structure and an example outline for an essay about the problem of fake news.

- Introduce the problem

- Provide background

- Describe your approach to solving it

- Define the problem precisely

- Describe why it’s important

- Indicate previous approaches to the problem

- Present your new approach, and why it’s better

- Apply the new method or theory to the problem

- Indicate the solution you arrive at by doing so

- Assess (potential or actual) effectiveness of solution

- Describe the implications

- Problem: The growth of “fake news” online

- Prevalence of polarized/conspiracy-focused news sources online

- Thesis statement: Rather than attempting to stamp out online fake news through social media moderation, an effective approach to combating it must work with educational institutions to improve media literacy

- Definition: Deliberate disinformation designed to spread virally online

- Popularization of the term, growth of the phenomenon

- Previous approaches: Labeling and moderation on social media platforms

- Critique: This approach feeds conspiracies; the real solution is to improve media literacy so users can better identify fake news

- Greater emphasis should be placed on media literacy education in schools

- This allows people to assess news sources independently, rather than just being told which ones to trust

- This is a long-term solution but could be highly effective

- It would require significant organization and investment, but would equip people to judge news sources more effectively

- Rather than trying to contain the spread of fake news, we must teach the next generation not to fall for it

Signposting means guiding the reader through your essay with language that describes or hints at the structure of what follows. It can help you clarify your structure for yourself as well as helping your reader follow your ideas.

The essay overview

In longer essays whose body is split into multiple named sections, the introduction often ends with an overview of the rest of the essay. This gives a brief description of the main idea or argument of each section.

The overview allows the reader to immediately understand what will be covered in the essay and in what order. Though it describes what comes later in the text, it is generally written in the present tense . The following example is from a literary analysis essay on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

Transitions

Transition words and phrases are used throughout all good essays to link together different ideas. They help guide the reader through your text, and an essay that uses them effectively will be much easier to follow.

Various different relationships can be expressed by transition words, as shown in this example.

Because Hitler failed to respond to the British ultimatum, France and the UK declared war on Germany. Although it was an outcome the Allies had hoped to avoid, they were prepared to back up their ultimatum in order to combat the existential threat posed by the Third Reich.

Transition sentences may be included to transition between different paragraphs or sections of an essay. A good transition sentence moves the reader on to the next topic while indicating how it relates to the previous one.

… Distance learning, then, seems to improve accessibility in some ways while representing a step backwards in others.

However , considering the issue of personal interaction among students presents a different picture.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

An essay isn’t just a loose collection of facts and ideas. Instead, it should be centered on an overarching argument (summarized in your thesis statement ) that every part of the essay relates to.

The way you structure your essay is crucial to presenting your argument coherently. A well-structured essay helps your reader follow the logic of your ideas and understand your overall point.

Comparisons in essays are generally structured in one of two ways:

- The alternating method, where you compare your subjects side by side according to one specific aspect at a time.

- The block method, where you cover each subject separately in its entirety.

It’s also possible to combine both methods, for example by writing a full paragraph on each of your topics and then a final paragraph contrasting the two according to a specific metric.

You should try to follow your outline as you write your essay . However, if your ideas change or it becomes clear that your structure could be better, it’s okay to depart from your essay outline . Just make sure you know why you’re doing so.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Structure an Essay | Tips & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved June 28, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/essay-structure/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, comparing and contrasting in an essay | tips & examples, how to write the body of an essay | drafting & redrafting, transition sentences | tips & examples for clear writing, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

)

How to Write an Essay

Published March 11, 2021. Updated May 5, 2022.

Essay Definition

An essay is a focused piece of writing that typically expresses a writer’s argument, opinion, or story about one subject.

Overview of an Essay

There is no one correct way to write an essay. Writing is a cyclical process. A writer may start by writing the introduction, get stuck, start writing a body paragraph, and then suddenly get inspiration for something else to put in the introduction.

If the writer has a clear outline, it is perfectly fine to switch between sections of the paper many times throughout the writing process. The four stages of writing an essay are prewriting, writing, revising, and editing. The amount of time spent in each stage depends on the type and complexity of the essay, as well as the individual’s strengths and weaknesses.

Worried about your writing? Submit your paper for a Chegg Writing essay check , or for an Expert Check proofreading . Both can help you find and fix potential writing issues.

Before you even begin writing your essay, there are several things you need to do to prepare your information and organize your ideas. This before-writing, or “prewriting,” stage includes evaluating the prompt or topic, conducting research, writing your working thesis, and creating an outline.

Evaluate the Prompt or Topic

Make sure you understand the assignment and the type of essay you are writing. If given a specific prompt, analyze the prompt several times, underlining or circling key action words like “claim” or “evaluate” along with key dates and terms from your class. If you are not given a specific prompt, consider the topic you want to write about. Most undergraduate-level essays are at least somewhat argumentative in nature. You will likely have to choose a side or position to argue, and now is the time to establish your stance.

Conduct Research

For many writing assignments, conducting research takes the most time. The type of research you conduct depends on the type of essay you are writing. For literary analysis essays, you will likely gather evidence from texts or critical essays on your topic. For argumentative essays, you will likely search databases or books for evidence that supports your claim. Regardless of what information you are searching for, use reliable and credible sources based on your course or discipline’s established guidelines.

Organize your research using a method that works for you. You might create physical or digital flashcards, use a graphic organizer, or simply record information in a document on your computer. Regardless of the method you choose, organize your information according to ideas rather than just listing the information all together. Sorting your information while you research will help you identify trends and areas where you have too much or too little information.

Write Your Working Thesis

A working thesis is a draft version of a thesis statement to use in the final version of your essay. You will likely revise the thesis several times throughout the writing process. Try to be clear and specific, answer the prompt directly, and state a claim you will prove in the essay. Writing the thesis directly after you research but before you draft your paper helps establish your essay’s focus.

Create an Outline

The final part of the prewriting stage is creating an outline. An outline is an organized overview of what you are going to write in your essay. An essay outline identifies your key points in a logical way. Some outlines are simple and identify only the main ideas and supporting details. Others are more complex and include full topic sentences and nearly all the research you plan to use in the essay.