Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on December 17, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviews.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymized) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymized comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymized) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymized) review —where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymized—does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimizes potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymize everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimize back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarize the argument in your own words

Summarizing the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organized. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

Tip: Try not to focus too much on the minor issues. If the manuscript has a lot of typos, consider making a note that the author should address spelling and grammar issues, rather than going through and fixing each one.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticized, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the “compliment sandwich,” where you “sandwich” your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarized or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published. There is also high risk of publication bias , where journals are more likely to publish studies with positive findings than studies with negative findings.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field. It acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/peer-review/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Find Resources for Your Midterms or Finals: Scholarly (Peer-reviewed) Journal Articles

- Scholarly (Peer-reviewed) Journal Articles

- Popular Sources

- Getting Research Help

What is Peer Review?

Peer review is the formal process scholarly journals employ to ensure that a manuscript's writing, methodology, arguments, and conclusions are sound. Peer review has long been a marker of quality that sets scholarly articles apart from popular articles (like those you would find in a magazine or newspaper).

Check out the video below for more information on peer review!

Tutorial: Peer Review

If your browser does not display frames, please use the direct link to the video provided on this page.

- Peer Review

Library Databases

You'll want to use the Pfau Library's databases to access peer-reviewed scholarly journal articles. The library subscribes to these databases, which give you (as a student) FREE access. If you don't use a library database and try to locate articles through a Google Search or by going directly to a journal's website, for example, you'll often hit a paywall and be asked to pay.

- Starter Databases for Finding Articles Try these recommended databases for locating scholarly articles.

- Explore our Databases by Subject Find databases for particular subjects, from anthropology and geography to nursing and world languages.

Getting a Copy of the Actual Article

Library databases often include complete copies of the articles themselves, or full text . On your results list, look for a link or an icon indicating that full text is available.

If the article is available in any of Pfau Library's databases, or is free on the Web, you'll be given a link to get it.

If the article might be in the library's hard-copy journals, this will be indicated.

If the article isn't available, you'll get a chance to request a copy through Interlibrary Loan.

Database Search Tips

Think of keywords, or important words describing each aspect of your topic, such as:

food insecurity college students

If you are not getting the results you want, think of synonyms or related terms that might get at your topic. For example:

hunger university students

You can search related terms at the same time. To do so, put OR between the related terms, then bracket them off with parentheses like this:

(hunger OR food insecurity)(university students OR college students)

Keep track of the keywords you use! You will want to try the same searches in different databases.

* Be sure to limit your results to peer-reviewed articles . To do so, select the Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals or Peer Reviewed box – most databases have this option. If you're not sure whether what you're seeing is peer-reviewed or not, contact a librarian or your professor.

Citation Chasing

When you find an article that's on point, check out its citations/references/works cited list. This will likely lead you to other relevant articles. If you have the name of an article you want, the easiest way to get it is to enter the full title in OneSearch.

- OneSearch Try a search in our online catalog!

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Popular Sources >>

- Last Updated: Oct 14, 2022 2:10 PM

- URL: https://libguides.csusb.edu/finals

The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

My Complete Guide to Academic Peer Review: Example Comments & How to Make Paper Revisions

Once you’ve submitted your paper to an academic journal you’re in the nerve-racking position of waiting to hear back about the fate of your work. In this post we’ll cover everything from potential responses you could receive from the editor and example peer review comments through to how to submit revisions.

My first first-author paper was reviewed by five (yes 5!) reviewers and since then I’ve published several others papers, so now I want to share the insights I’ve gained which will hopefully help you out!

This post is part of my series to help with writing and publishing your first academic journal paper. You can find the whole series here: Writing an academic journal paper .

The Peer Review Process

When you submit a paper to a journal, the first thing that will happen is one of the editorial team will do an initial assessment of whether or not the article is of interest. They may decide for a number of reasons that the article isn’t suitable for the journal and may reject the submission before even sending it out to reviewers.

If this happens hopefully they’ll have let you know quickly so that you can move on and make a start targeting a different journal instead.

Handy way to check the status – Sign in to the journal’s submission website and have a look at the status of your journal article online. If you can see that the article is under review then you’ve passed that first hurdle!

When your paper is under peer review, the journal will have set out a framework to help the reviewers assess your work. Generally they’ll be deciding whether the work is to a high enough standard.

Interested in reading about what reviewers are looking for? Check out my post on being a reviewer for the first time. Peer-Reviewing Journal Articles: Should You Do It? Sharing What I Learned From My First Experiences .

Once the reviewers have made their assessments, they’ll return their comments and suggestions to the editor who will then decide how the article should proceed.

How Many People Review Each Paper?

The editor ideally wants a clear decision from the reviewers as to whether the paper should be accepted or rejected. If there is no consensus among the reviewers then the editor may send your paper out to more reviewers to better judge whether or not to accept the paper.

If you’ve got a lot of reviewers on your paper it isn’t necessarily that the reviewers disagreed about accepting your paper.

You can also end up with lots of reviewers in the following circumstance:

- The editor asks a certain academic to review the paper but doesn’t get a response from them

- The editor asks another academic to step in

- The initial reviewer then responds

Next thing you know your work is being scrutinised by extra pairs of eyes!

As mentioned in the intro, my first paper ended up with five reviewers!

Potential Journal Responses

Assuming that the paper passes the editor’s initial evaluation and is sent out for peer-review, here are the potential decisions you may receive:

- Reject the paper. Sadly the editor and reviewers decided against publishing your work. Hopefully they’ll have included feedback which you can incorporate into your submission to another journal. I’ve had some rejections and the reviewer comments were genuinely useful.

- Accept the paper with major revisions . Good news: with some more work your paper could get published. If you make all the changes that the reviewers suggest, and they’re happy with your responses, then it should get accepted. Some people see major revisions as a disappointment but it doesn’t have to be.

- Accept the paper with minor revisions. This is like getting a major revisions response but better! Generally minor revisions can be addressed quickly and often come down to clarifying things for the reviewers: rewording, addressing minor concerns etc and don’t require any more experiments or analysis. You stand a really good chance of getting the paper published if you’ve been given a minor revisions result.

- Accept the paper with no revisions . I’m not sure that this ever really happens, but it is potentially possible if the reviewers are already completely happy with your paper!

Keen to know more about academic publishing? My series on publishing is now available as a free eBook. It includes my experiences being a peer reviewer. Click the image below for access.

Example Peer Review Comments & Addressing Reviewer Feedback

If your paper has been accepted but requires revisions, the editor will forward to you the comments and concerns that the reviewers raised. You’ll have to address these points so that the reviewers are satisfied your work is of a publishable standard.

It is extremely important to take this stage seriously. If you don’t do a thorough job then the reviewers won’t recommend that your paper is accepted for publication!

You’ll have to put together a resubmission with your co-authors and there are two crucial things you must do:

- Make revisions to your manuscript based off reviewer comments

- Reply to the reviewers, telling them the changes you’ve made and potentially changes you’ve not made in instances where you disagree with them. Read on to see some example peer review comments and how I replied!

Before making any changes to your actual paper, I suggest having a thorough read through the reviewer comments.

Once you’ve read through the comments you might be keen to dive straight in and make the changes in your paper. Instead, I actually suggest firstly drafting your reply to the reviewers.

Why start with the reply to reviewers? Well in a way it is actually potentially more important than the changes you’re making in the manuscript.

Imagine when a reviewer receives your response to their comments: you want them to be able to read your reply document and be satisfied that their queries have largely been addressed without even having to open the updated draft of your manuscript. If you do a good job with the replies, the reviewers will be better placed to recommend the paper be accepted!

By starting with your reply to the reviewers you’ll also clarify for yourself what changes actually have to be made to the paper.

So let’s now cover how to reply to the reviewers.

1. Replying to Journal Reviewers

It is so important to make sure you do a solid job addressing your reviewers’ feedback in your reply document. If you leave anything unanswered you’re asking for trouble, which in this case means either a rejection or another round of revisions: though some journals only give you one shot! Therefore make sure you’re thorough, not just with making the changes but demonstrating the changes in your replies.

It’s no good putting in the work to revise your paper but not evidence it in your reply to the reviewers!

There may be points that reviewers raise which don’t appear to necessitate making changes to your manuscript, but this is rarely the case. Even for comments or concerns they raise which are already addressed in the paper, clearly those areas could be clarified or highlighted to ensure that future readers don’t get confused.

How to Reply to Journal Reviewers

Some journals will request a certain format for how you should structure a reply to the reviewers. If so this should be included in the email you receive from the journal’s editor. If there are no certain requirements here is what I do:

- Copy and paste all replies into a document.

- Separate out each point they raise onto a separate line. Often they’ll already be nicely numbered but sometimes they actually still raise separate issues in one block of text. I suggest separating it all out so that each query is addressed separately.

- Form your reply for each point that they raise. I start by just jotting down notes for roughly how I’ll respond. Once I’m happy with the key message I’ll write it up into a scripted reply.

- Finally, go through and format it nicely and include line number references for the changes you’ve made in the manuscript.

By the end you’ll have a document that looks something like:

Reviewer 1 Point 1: [Quote the reviewer’s comment] Response 1: [Address point 1 and say what revisions you’ve made to the paper] Point 2: [Quote the reviewer’s comment] Response 2: [Address point 2 and say what revisions you’ve made to the paper] Then repeat this for all comments by all reviewers!

What To Actually Include In Your Reply To Reviewers

For every single point raised by the reviewers, you should do the following:

- Address their concern: Do you agree or disagree with the reviewer’s comment? Either way, make your position clear and justify any differences of opinion. If the reviewer wants more clarity on an issue, provide it. It is really important that you actually address their concerns in your reply. Don’t just say “Thanks, we’ve changed the text”. Actually include everything they want to know in your reply. Yes this means you’ll be repeating things between your reply and the revisions to the paper but that’s fine.

- Reference changes to your manuscript in your reply. Once you’ve answered the reviewer’s question, you must show that you’re actually using this feedback to revise the manuscript. The best way to do this is to refer to where the changes have been made throughout the text. I personally do this by include line references. Make sure you save this right until the end once you’ve finished making changes!

Example Peer Review Comments & Author Replies

In order to understand how this works in practice I’d suggest reading through a few real-life example peer review comments and replies.

The good news is that published papers often now include peer-review records, including the reviewer comments and authors’ replies. So here are two feedback examples from my own papers:

Example Peer Review: Paper 1

Quantifying 3D Strain in Scaffold Implants for Regenerative Medicine, J. Clark et al. 2020 – Available here

This paper was reviewed by two academics and was given major revisions. The journal gave us only 10 days to get them done, which was a bit stressful!

- Reviewer Comments

- My reply to Reviewer 1

- My reply to Reviewer 2

One round of reviews wasn’t enough for Reviewer 2…

- My reply to Reviewer 2 – ROUND 2

Thankfully it was accepted after the second round of review, and actually ended up being selected for this accolade, whatever most notable means?!

Nice to see our recent paper highlighted as one of the most notable articles, great start to the week! Thanks @Materials_mdpi 😀 #openaccess & available here: https://t.co/AKWLcyUtpC @ICBiomechanics @julianrjones @saman_tavana pic.twitter.com/ciOX2vftVL — Jeff Clark (@savvy_scientist) December 7, 2020

Example Peer Review: Paper 2

Exploratory Full-Field Mechanical Analysis across the Osteochondral Tissue—Biomaterial Interface in an Ovine Model, J. Clark et al. 2020 – Available here

This paper was reviewed by three academics and was given minor revisions.

- My reply to Reviewer 3

I’m pleased to say it was accepted after the first round of revisions 🙂

Things To Be Aware Of When Replying To Peer Review Comments

- Generally, try to make a revision to your paper for every comment. No matter what the reviewer’s comment is, you can probably make a change to the paper which will improve your manuscript. For example, if the reviewer seems confused about something, improve the clarity in your paper. If you disagree with the reviewer, include better justification for your choices in the paper. It is far more favourable to take on board the reviewer’s feedback and act on it with actual changes to your draft.

- Organise your responses. Sometimes journals will request the reply to each reviewer is sent in a separate document. Unless they ask for it this way I stick them all together in one document with subheadings eg “Reviewer 1” etc.

- Make sure you address each and every question. If you dodge anything then the reviewer will have a valid reason to reject your resubmission. You don’t need to agree with them on every point but you do need to justify your position.

- Be courteous. No need to go overboard with compliments but stay polite as reviewers are providing constructive feedback. I like to add in “We thank the reviewer for their suggestion” every so often where it genuinely warrants it. Remember that written language doesn’t always carry tone very well, so rather than risk coming off as abrasive if I don’t agree with the reviewer’s suggestion I’d rather be generous with friendliness throughout the reply.

2. How to Make Revisions To Your Paper

Once you’ve drafted your replies to the reviewers, you’ve actually done a lot of the ground work for making changes to the paper. Remember, you are making changes to the paper based off the reviewer comments so you should regularly be referring back to the comments to ensure you’re not getting sidetracked.

Reviewers could request modifications to any part of your paper. You may need to collect more data, do more analysis, reformat some figures, add in more references or discussion or any number of other revisions! So I can’t really help with everything, even so here is some general advice:

- Use tracked-changes. This is so important. The editor and reviewers need to be able to see every single change you’ve made compared to your first submission. Sometimes the journal will want a clean copy too but always start with tracked-changes enabled then just save a clean copy afterwards.

- Be thorough . Try to not leave any opportunity for the reviewers to not recommend your paper to be published. Any chance you have to satisfy their concerns, take it. For example if the reviewers are concerned about sample size and you have the means to include other experiments, consider doing so. If they want to see more justification or references, be thorough. To be clear again, this doesn’t necessarily mean making changes you don’t believe in. If you don’t want to make a change, you can justify your position to the reviewers. Either way, be thorough.

- Use your reply to the reviewers as a guide. In your draft reply to the reviewers you should have already included a lot of details which can be incorporated into the text. If they raised a concern, you should be able to go and find references which address the concern. This reference should appear both in your reply and in the manuscript. As mentioned above I always suggest starting with the reply, then simply adding these details to your manuscript once you know what needs doing.

Putting Together Your Paper Revision Submission

- Once you’ve drafted your reply to the reviewers and revised manuscript, make sure to give sufficient time for your co-authors to give feedback. Also give yourself time afterwards to make changes based off of their feedback. I ideally give a week for the feedback and another few days to make the changes.

- When you’re satisfied that you’ve addressed the reviewer comments, you can think about submitting it. The journal may ask for another letter to the editor, if not I simply add to the top of the reply to reviewers something like:

“Dear [Editor], We are grateful to the reviewer for their positive and constructive comments that have led to an improved manuscript. Here, we address their concerns/suggestions and have tracked changes throughout the revised manuscript.”

Once you’re ready to submit:

- Double check that you’ve done everything that the editor requested in their email

- Double check that the file names and formats are as required

- Triple check you’ve addressed the reviewer comments adequately

- Click submit and bask in relief!

You won’t always get the paper accepted, but if you’re thorough and present your revisions clearly then you’ll put yourself in a really good position. Remember to try as hard as possible to satisfy the reviewers’ concerns to minimise any opportunity for them to not accept your revisions!

Best of luck!

I really hope that this post has been useful to you and that the example peer review section has given you some ideas for how to respond. I know how daunting it can be to reply to reviewers, and it is really important to try to do a good job and give yourself the best chances of success. If you’d like to read other posts in my academic publishing series you can find them here:

Blog post series: Writing an academic journal paper

Subscribe below to stay up to date with new posts in the academic publishing series and other PhD content.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

The Five Most Powerful Lessons I Learned During My PhD

8th August 2024 8th August 2024

Minor Corrections: How To Make Them and Succeed With Your PhD Thesis

2nd June 2024 2nd June 2024

How to Master Data Management in Research

25th April 2024 4th August 2024

2 Comments on “My Complete Guide to Academic Peer Review: Example Comments & How to Make Paper Revisions”

Excellent article! Thank you for the inspiration!

No worries at all, thanks for your kind comment!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2020

- Volume 36 , pages 909–913, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clara Busse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0178-1000 1 &

- Ella August ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036 1 , 2

281k Accesses

16 Citations

708 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

How to Choose the Right Journal

The Point Is…to Publish?

Writing and publishing a scientific paper

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

Structure of the Introduction Section

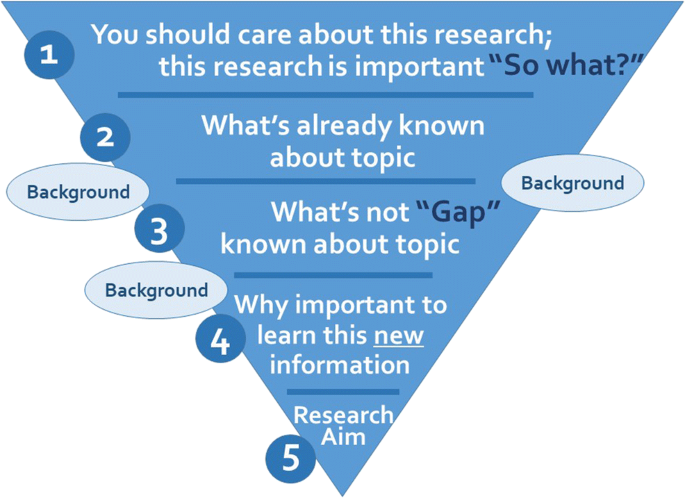

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Discussion Section

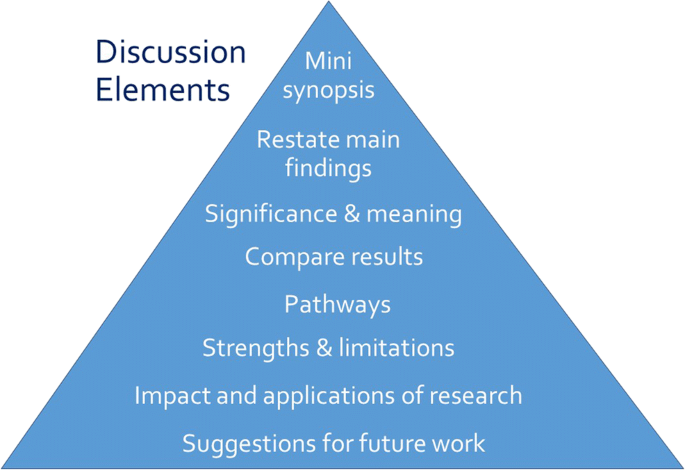

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

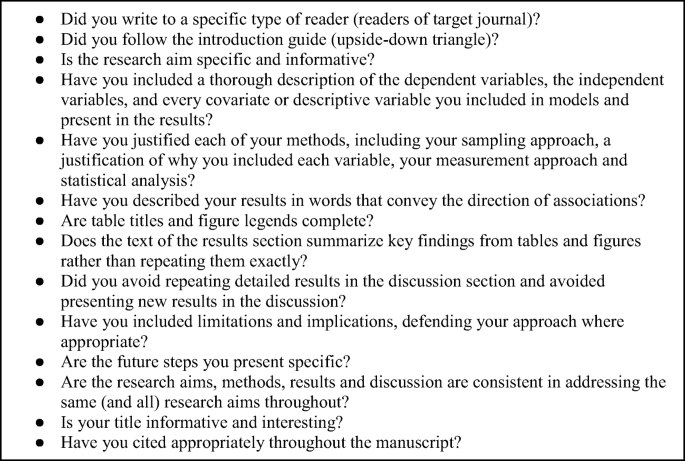

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

Data Availability

Michalek AM (2014) Down the rabbit hole…advice to reviewers. J Cancer Educ 29:4–5

Article Google Scholar

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors: who is an author? http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authosrs-and-contributors.html . Accessed 15 January, 2020

Vetto JT (2014) Short and sweet: a short course on concise medical writing. J Cancer Educ 29(1):194–195

Brett M, Kording K (2017) Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLoS ComputBiol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

Lang TA (2017) Writing a better research article. J Public Health Emerg. https://doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2017.11.06

Download references

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Clara Busse & Ella August

Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-2029, USA

Ella August

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ella August .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 362 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Busse, C., August, E. How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal. J Canc Educ 36 , 909–913 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Download citation

Published : 30 April 2020

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Manuscripts

- Scientific writing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Reviewer Guidelines

- Peer review model

- Scope & article eligibility

- Reviewer eligibility

- Peer reviewer code of conduct

- Guidelines for reviewing

- How to submit

- The peer-review process

- Peer Reviewing Tips

- Benefits for Reviewers

The genesis of this paper is the proposal that genomes containing a poor percentage of guanosine and cytosine (GC) nucleotide pairs lead to proteomes more prone to aggregation than those encoded by GC-rich genomes. As a consequence these organisms are also more dependent on the protein folding machinery. If true, this interesting hypothesis could establish a direct link between the tendency to aggregate and the genomic code.

In their paper, the authors have tested the hypothesis on the genomes of eubacteria using a genome-wide approach based on multiple machine learning models. Eubacteria are an interesting set of organisms which have an appreciably high variation in their nucleotide composition with the percentage of CG genetic material ranging from 20% to 70%. The authors classified different eubacterial proteomes in terms of their aggregation propensity and chaperone-dependence. For this purpose, new classifiers had to be developed which were based on carefully curated data. They took account for twenty-four different features among which are sequence patterns, the pseudo amino acid composition of phenylalanine, aspartic and glutamic acid, the distribution of positively charged amino acids, the FoldIndex score and the hydrophobicity. These classifiers seem to be altogether more accurate and robust than previous such parameters.

The authors found that, contrary to what expected from the working hypothesis, which would predict a decrease in protein aggregation with an increase in GC richness, the aggregation propensity of proteomes increases with the GC content and thus the stability of the proteome against aggregation increases with the decrease in GC content. The work also established a direct correlation between GC-poor proteomes and a lower dependence on GroEL. The authors conclude by proposing that a decrease in eubacterial GC content may have been selected in organisms facing proteostasis problems. A way to test the overall results would be through in vitro evolution experiments aimed at testing whether adaptation to low GC content provide folding advantage.

The main strengths of this paper is that it addresses an interesting and timely question, finds a novel solution based on a carefully selected set of rules, and provides a clear answer. As such this article represents an excellent and elegant bioinformatics genome-wide study which will almost certainly influence our thinking about protein aggregation and evolution. Some of the weaknesses are the not always easy readability of the text which establishes unclear logical links between concepts.

Another possible criticism could be that, as any in silico study, it makes strong assumptions on the sequence features that lead to aggregation and strongly relies on the quality of the classifiers used. Even though the developed classifiers seem to be more robust than previous such parameters, they remain only overall indications which can only allow statistical considerations. It could of course be argued that this is good enough to reach meaningful conclusions in this specific case.

The paper by Chevalier et al. analyzed whether late sodium current (I NaL ) can be assessed using an automated patch-clamp device. To this end, the I NaL effects of ranolazine (a well known I NaL inhibitor) and veratridine (an I NaL activator) were described. The authors tested the CytoPatch automated patch-clamp equipment and performed whole-cell recordings in HEK293 cells stably transfected with human Nav1.5. Furthermore, they also tested the electrophysiological properties of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPS) provided by Cellular Dynamics International. The title and abstract are appropriate for the content of the text. Furthermore, the article is well constructed, the experiments were well conducted, and analysis was well performed.

I NaL is a small current component generated by a fraction of Nav1.5 channels that instead to entering in the inactivated state, rapidly reopened in a burst mode. I NaL critically determines action potential duration (APD), in such a way that both acquired (myocardial ischemia and heart failure among others) or inherited (long QT type 3) diseases that augmented the I NaL magnitude also increase the susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmias. Therefore, I NaL has been recognized as an important target for the development of drugs with either antiischemic or antiarrhythmic effects. Unfortunately, accurate measurement of I NaL is a time consuming and technical challenge because of its extra-small density. The automated patch clamp device tested by Chevalier et al. resolves this problem and allows fast and reliable I NaL measurements.

The results here presented merit some comments and arise some unresolved questions. First, in some experiments (such is the case in experiments B and D in Figure 2) current recordings obtained before the ranolazine perfusion seem to be quite unstable. Indeed, the amplitude progressively increased to a maximum value that was considered as the control value (highlighted with arrows). Can this problem be overcome? Is this a consequence of a slow intracellular dialysis? Is it a consequence of a time-dependent shift of the voltage dependence of activation/inactivation? Second, as shown in Figure 2, intensity of drug effects seems to be quite variable. In fact, experiments A, B, C, and D in Figure 2 and panel 2D, demonstrated that veratridine augmentation ranged from 0-400%. Even assuming the normal biological variability, we wonder as to whether this broad range of effect intensities can be justified by changes in the perfusion system. Has been the automated dispensing system tested? If not, we suggest testing the effects of several K + concentrations on inward rectifier currents generated by Kir2.1 channels (I Kir2.1 ).

The authors demonstrated that the recording quality was so high that the automated device allows to the differentiation between noise and current, even when measuring currents of less than 5 pA of amplitude. In order to make more precise mechanistic assumptions, the authors performed an elegant estimation of current variance (σ 2 ) and macroscopic current (I) following the procedure described more than 30 years ago by Van Driessche and Lindemann 1 . By means of this method, Chevalier et al. reducing the open channel probability, while veratridine increases the number of channels in the burst mode. We respectfully would like to stress that these considerations must be put in context from a pharmacological point of view. We do not doubt that ranolazine acts as an open channel blocker, what it seems clear however, is that its onset block kinetics has to be “ultra” slow, otherwise ranolazine would decrease peak I NaL even at low frequencies of stimulation. This comment points towards the fact that for a precise mechanistic study of ionic current modifying drugs it is mandatory to analyze drug effects with much more complicated pulse protocols. Questions thus are: does this automated equipment allow to the analysis of the frequency-, time-, and voltage-dependent effects of drugs? Can versatile and complicated pulse protocols be applied? Does it allow to a good voltage control even when generated currents are big and fast? If this is not possible, and by means of its extraordinary discrimination between current and noise, this automated patch-clamp equipment will only be helpful for rapid I NaL -modifying drug screening. Obviously it will also be perfect to test HERG blocking drug effects as demanded by the regulatory authorities.

Finally, as cardiac electrophysiologists, we would like to stress that it seems that our dream of testing drug effects on human ventricular myocytes seems to come true. Indeed, human atrial myocytes are technically, ethically and logistically difficult to get, but human ventricular are almost impossible to be obtained unless from the explanted hearts from patients at the end stage of cardiac diseases. Here the authors demonstrated that ventricular myocytes derived from hiPS generate beautiful action potentials that can be recorded with this automated equipment. The traces shown suggested that there was not alternation in the action potential duration. Is this a consistent finding? How long do last these stable recordings? The only comment is that resting membrane potential seems to be somewhat variable. Can this be resolved? Is it an unexpected veratridine effect? Standardization of maturation methods of ventricular myocytes derived from hiPS will be a big achievement for cardiac cellular electrophysiology which was obliged for years to the imprecise extrapolation of data obtained from a combination of several species none of which was representative of human electrophysiology. The big deal will be the maturation of human atrial myocytes derived from hiPS that fulfil the known characteristics of human atrial cells.

We suggest suppressing the initial sentence of section 3. We surmise that results obtained from the experiments described in this section cannot serve to understand the role of I NaL in arrhythmogenesis.

1. Van Driessche W, Lindemann B: Concentration dependence of currents through single sodium-selective pores in frog skin. Nature . 1979; 282 (5738): 519-520 PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

The authors have clarified several of the questions I raised in my previous review. Unfortunately, most of the major problems have not been addressed by this revision. As I stated in my previous review, I deem it unlikely that all those issues can be solved merely by a few added paragraphs. Instead there are still some fundamental concerns with the experimental design and, most critically, with the analysis. This means the strong conclusions put forward by this manuscript are not warranted and I cannot approve the manuscript in this form.

- The greatest concern is that when I followed the description of the methods in the previous version it was possible to decode, with almost perfect accuracy, any arbitrary stimulus labels I chose. See https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1167456 for examples of this reanalysis. Regardless of whether we pretend that the actual stimulus appeared at a later time or was continuously alternating between signal and silence, the decoding is always close to perfect. This is an indication that the decoding has nothing to do with the actual stimulus heard by the Sender but is opportunistically exploiting some other features in the data. The control analysis the authors performed, reversing the stimulus labels, cannot address this problem because it suffers from the exact same problem. Essentially, what the classifier is presumably using is the time that has passed since the recording started.

- The reason for this is presumably that the authors used non-independent data for training and testing. Assuming I understand correctly (see point 3), random sampling one half of data samples from an EEG trace are not independent data . Repeating the analysis five times – the control analysis the authors performed – is not an adequate way to address this concern. Randomly selecting samples from a time series containing slow changes (such as the slow wave activity that presumably dominates these recordings under these circumstances) will inevitably contain strong temporal correlations. See TemporalCorrelations.jpg in https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1185723 for 2D density histograms and a correlation matrix demonstrating this.

- While the revised methods section provides more detail now, it still is unclear about exactly what data were used. Conventional classification analysis report what data features (usual columns in the data matrix) and what observations (usual rows) were used. Anything could be a feature but typically this might be the different EEG channels or fMRI voxels etc. Observations are usually time points. Here I assume the authors transformed the raw samples into a different space using principal component analysis. It is not stated if the dimensionality was reduced using the eigenvalues. Either way, I assume the data samples (collected at 128 Hz) were then used as observations and the EEG channels transformed by PCA were used as features. The stimulus labels were assigned as ON or OFF for each sample. A set of 50% of samples (and labels) was then selected at random for training, and the rest was used for testing. Is this correct?

- A powerful non-linear classifier can capitalise on such correlations to discriminate arbitrary labels. In my own analyses I used both an SVM with RBF as well as a k-nearest neighbour classifier, both of which produce excellent decoding of arbitrary stimulus labels (see point 1). Interestingly, linear classifiers or less powerful SVM kernels fare much worse – a clear indication that the classifier learns about the complex non-linear pattern of temporal correlations that can describe the stimulus label. This is further corroborated by the fact that when using stimulus labels that are chosen completely at random (i.e. with high temporal frequency) decoding does not work.

- The authors have mostly clarified how the correlation analysis was performed. It is still left unclear, however, how the correlations for individual pairs were averaged. Was Fisher’s z-transformation used, or were the data pooled across pairs? More importantly, it is not entirely surprising that under the experimental conditions there will be some correlation between the EEG signals for different participants, especially in low frequency bands. Again, this further supports the suspicion that the classification utilizes slow frequency signals that are unrelated to the stimulus and the experimental hypothesis. In fact, a quick spot check seems to confirm this suspicion: correlating the time series separately for each channel from the Receiver in pair 1 with those from the Receiver in pair 18 reveals 131 significant (p‹0.05, Bonferroni corrected) out of 196 (14x14 channels) correlations… One could perhaps argue that this is not surprising because both these pairs had been exposed to identical stimulus protocols: one minute of initial silence and only one signal period (see point 6). However, it certainly argues strongly against the notion that the decoding is any way related to the mental connection between the particular Sender and Receiver in a given pair because it clearly works between Receivers in different pairs! However, to further control for this possibility I repeated the same analysis but now comparing the Receiver from pair 1 to the Receiver from pair 15. This pair was exposed to a different stimulus paradigm (2 minutes of initial silence and a longer paradigm with three signal periods). I only used the initial 3 minutes for the correlation analysis. Therefore, both recordings would have been exposed to only one signal period but at different times (at 1 min and 2 min for pair 1 and 15, respectively). Even though the stimulus protocol was completely different the time courses for all the channels are highly correlated and 137 out of 196 correlations are significant. Considering that I used the raw data for this analysis it should not surprise anyone that extracting power from different frequency bands in short time windows will also reveal significant correlations. Crucially, it demonstrates that correlations between Sender and Receiver are artifactual and trivial.

- The authors argue in their response and the revision that predictive strategies were unlikely. After having performed these additional analyses I am inclined to agree. The excellent decoding almost certainly has nothing to do with expectation or imagery effects and it is irrelevant whether participants could guess the temporal design of the experiment. Rather, the results are almost entirely an artefact of the analysis. However, this does not mean that predictability is not an issue. The figure StimulusTimecourses.jpg in https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1185723 plots the stimulus time courses for all 20 pairs as can be extracted from the newly uploaded data. This confirms what I wrote in my previous review, in fact, with the corrected data sets the problem with predictability is even greater. Out of the 20 pairs, 13 started with 1 min of initial silence. The remaining 7 had 2 minutes of initial silence. Most of the stimulus paradigms are therefore perfectly aligned and thus highly correlated. This also proves incorrect the statement that initial silence periods were 1, 2, or 3 minutes. No pair had 3 min of initial silence. It would therefore have been very easy for any given Receiver to correctly guess the protocol. It should be clear that this is far from optimal for testing such an unorthodox hypothesis. Any future experiments should employ more randomization to decrease predictability. Even if this wasn’t the underlying cause of the present results, this is simply not great experimental design.

- The authors now acknowledge in their response that all the participants were authors. They say that this is also acknowledged in the methods section, but I did not see any statement about that in the revised manuscript. As before, I also find it highly questionable to include only authors in an experiment of this kind. It is not sufficient to claim that Receivers weren’t guessing their stimulus protocol. While I am giving the authors (and thus the participants) the benefit of the doubt that they actually believe they weren’t guessing/predicting the stimulus protocols, this does not rule out that they did. It may in fact be possible to make such predictions subconsciously (Now, if you ask me, this is an interesting scientific question someone should do an experiment on!). The fact familiar with the protocol may help that. Any future experiments should take steps to prevent this.

- I do not follow the explanation for the binomial test the authors used. Based on the excessive Bayes Factor of 390,625 it is clear that the authors assumed a chance level of 50% on their binomial test. Because the design is not balanced, this is not correct.

- In general, the Bayes Factor and the extremely high decoding accuracy should have given the authors reason to start. Considering the unusual hypothesis did the authors not at any point wonder if these results aren’t just far too good to be true? Decoding mental states from brain activity is typically extremely noisy and hardly affords accuracies at the level seen here. Extremely accurate decoding and Bayes Factors in the hundreds of thousands should be a tell-tale sign to check that there isn’t an analytical flaw that makes the result entirely trivial. I believe this is what happened here and thus I think this experiment serves as a very good demonstration for the pitfalls of applying such analysis without sanity checks. In order to make claims like this, the experimental design must contain control conditions that can rule out these problems. Presumably, recordings without any Sender, and maybe even when the “Receiver” is aware of this fact, should produce very similar results.

Based on all these factors, it is impossible for me to approve this manuscript. I should however state that it is laudable that the authors chose to make all the raw data of their experiment publicly available. Without this it would have impossible for me to carry out the additional analyses, and thus the most fundamental problem in the analysis would have remained unknown. I respect the authors’ patience and professionalism in dealing with what I can only assume is a rather harsh review experience. I am honoured by the request for an adversarial collaboration. I do not rule out such efforts at some point in the future. However, for all of the reasons outlined in this and my previous review, I do not think the time is right for this experiment to proceed to this stage. Fundamental analytical flaws and weaknesses in the design should be ruled out first. An adversarial collaboration only really makes sense to me for paradigms were we can be confident that mundane or trivial factors have been excluded.

This manuscript does an excellent job demonstrating significant strain differences in Burdian's paradigm. Since each Drosophila lab has their own wild type (usually Canton-S) isolate, this issue of strain differences is actually a very important one for between lab reproducibility. This work is a good reminder for all geneticists to pay attention to the population effects in the background controls, and presumably the mutant lines we are comparing.

I was very pleased to see the within-isolate behavior was consistent in replicate experiments one year apart. The authors further argue that the between-isolate differences in behavior arise from a Founder's effect, at least in the differences in locomotor behavior between the Paris lines CS_TP and CS_JC. I believe this is a very reasonable and testable hypothesis. It predicts that genetic variability for these traits exist within the populations. It should now be possible to perform selection experiments from the original CS_TP population to replicate the founding event and estimate the heritability of these traits.

Two other things that I liked about this manuscript are the ability to adjust parameters in figure 3, and our ability to download the raw data. After reading the manuscript, I was a little disappointed that the performance of the five strains in each 12 behavioral variables weren't broken down individually in a table or figure. I thought this may help us readers understand what the principle components were representing. The authors have made this data readily accessible in a downloadable spreadsheet.

This is an exceptionally good review and balanced assessment of the status of CETP inhibitors and ASCVD from a world authority in the field. The article highlights important data that might have been overlooked when promulgating the clinical value of CETPIs and related trials.

Only 2 areas need revision:

- Page 3, para 2: the notion that these data from Papp et al . convey is critical and the message needs an explicit sentence or two at end of paragraph.

- Page 4, Conclusion: the assertion concerning the ethics of the two Phase 3 clinical trials needs toning down. Perhaps rephrase to indicate that the value and sense of doing these trials is open to question, with attendant ethical implications, or softer wording to that effect.

The Wiley et al . manuscript describes a beautiful synthesis of contemporary genetic approaches to, with astonishing efficiency, identify lead compounds for therapeutic approaches to a serious human disease. I believe the importance of this paper stems from the applicability of the approach to the several thousand of rare human disease genes that Next-Gen sequencing will uncover in the next few years and the challenge we will have in figuring out the function of these genes and their resulting defects. This work presents a paradigm that can be broadly and usefully applied.

In detail, the authors begin with gene responsible for X-linked spinal muscular atrophy and express both the wild-type version of that human gene as well as a mutant form of that gene in S. pombe . The conceptual leap here is that progress in genetics is driven by phenotype, and this approach involving a yeast with no spine or muscles to atrophy is nevertheless and N-dimensional detector of phenotype.

The study is not without a small measure of luck in that expression of the wild-type UBA1 gene caused a slow growth phenotype which the mutant did not. Hence there was something in S. pombe that could feel the impact of this protein. Given this phenotype, the authors then went to work and using the power of the synthetic genetic array approach pioneered by Boone and colleagues made a systematic set of double mutants combining the human expressed UBA1 gene with knockout alleles of a plurality of S. pombe genes. They found well over a hundred mutations that either enhanced or suppressed the growth defect of the cells expressing UBI1. Most of these have human orthologs. My hunch is that many human genes expressed in yeast will have some comparably exploitable phenotype, and time will tell.

Building on the interaction networks of S. pombe genes already established, augmenting these networks by the protein interaction networks from yeast and from human proteome studies involving these genes, and from the structure of the emerging networks, the authors deduced that an E3 ligase modulated UBA1 and made the leap that it therefore might also impact X-linked Spinal Muscular Atrophy.

Here, the awesome power of the model organism community comes into the picture as there is a zebrafish model of spinal muscular atrophy. The principle of phenologs articulated by the Marcotte group inspire the recognition of the transitive logic of how phenotypes in one organism relate to phenotypes in another. With this zebrafish model, they were able to confirm that an inhibitor of E3 ligases and of the Nedd8-E1 activating suppressed the motor axon anomalies, as predicted by the effect of mutations in S. pombe on the phenotypes of the UBA1 overexpression.

I believe this is an important paper to teach in intro graduate courses as it illustrates beautifully how important it is to know about and embrace the many new sources of systematic genetic information and apply them broadly.