After decades of failures, researchers have renewed hopes for an effective HIV vaccine

The world needs an HIV vaccine if it ever hopes to beat a virus that still infects over 1 million people a year and contributes to hundreds of thousands of deaths.

Despite 20 years of failures in major HIV vaccine trials — four this decade alone — researchers say recent scientific advances have likely, hopefully, put them on the right track to develop a highly effective vaccine against the insidious virus.

But probably not until the 2030s.

“An effective vaccine is really the only way to provide long-term immunity against HIV, and that’s what we need,” Dr. Julie McElrath, the director of the vaccine and infectious disease division at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, said Monday at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Denver.

All current HIV vaccine action is in the laboratory, animal studies or very early human trials.

Researchers at the retrovirus conference presented favorable results from two HIV vaccine studies. One found that a modification to the simian version of HIV spurred production of what are known as broadly neutralizing antibodies against the virus in monkeys. Another showed promise in the effort to coax the immune system’s B cells to make the powerful antibodies in humans.

“These trials illustrate as a proof of concept that we can train the immune system. But we need to further optimize it and test it in clinical trials,” Karlijn van der Straten, a Ph.D. student at the Academic Medical Center at Amsterdam University, who presented the human study, said at a news conference Monday.

Still, the scrappy scientists in this field face a towering challenge. HIV is perhaps the most complex pathogen ever known.

“The whole field has learned from the past,” said William Schief, who leads Moderna’s HIV vaccine efforts. “We’ve learned strategies that don’t work.”

The cost has already been immense. Nearly $17 billion was spent worldwide on HIV -vaccine research from 2000 to 2021. Nearly $1 billion more is spent annually, according to the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS and the nonprofit HIV group AVAC.

“Maintaining the funding for HIV vaccines right now is really important,” said Dr. Nina Russell, who directs HIV research at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. She pointed to the field’s own “progress and the excitement” and to how “HIV vaccine science and scientists continue to drive innovation and science that benefits other infectious diseases and global health in general.”

Case in point: Covid. Thanks to HIV research, the mRNA vaccine technology was already available in 2020 to speed a coronavirus vaccine to market.

Why the HIV vaccine efficacy trials failed

In strong contrast to Covid, the HIV vaccine endeavor has spanned four decades. Only one of the nine HIV vaccine trials have shown efficacy: a trial conducted in Thailand and published in 2009 that reported a modest 31% reduction in HIV risk.

HIV vaccine researchers subsequently spent years seeking to retool and improve that vaccine strategy, leading to a series of trials that launched in the late 2010s — only to fail.

Researchers have concluded those latest trials were doomed because, aside from prompting an anti-HIV response based in immune cells, they only drove the immune system to produce what are known as non-neutralizing antibodies. Those weapons just weren’t strong enough for such a fearsome foe.

Preventing HIV through vaccination remains a daunting challenge because the immune system doesn’t naturally mount an effective defense against the virus, as it does with so many other vaccine-preventable infections, including Covid. An HIV vaccine must coax from the body a supercharged immune response with no natural equivalent.

That path to victory is based on a crucial caveat: A small proportion of people with HIV do produce what are known as broadly neutralizing antibodies against the virus. They attack HIV in multiple ways and can neutralize a swath of variants of the virus.

Those antibodies don’t do much apparent good for people who develop them naturally, because they typically don’t arise until years into infection. HIV establishes a permanent reservoir in the body within about a week after infection, one that their immune response can’t eliminate. So HIV-positive people with such antibodies still require antiretroviral treatment to remain healthy.

Researchers believe that broadly neutralizing antibodies could prevent HIV from ever seeding an infection, provided the defense was ready in advance of exposure. A pair of major efficacy trials, published in 2021 , demonstrated that infusions of cloned versions of one such antibody did, indeed, protect people who were exposed to certain HIV strains that are susceptible to that antibody.

However, globally, those particular strains of the virus comprise only a small subset of all circulating HIV. That means researchers can’t simply prompt a vaccine to produce that one antibody and expect it to be effective. Importantly, from this study they got a sense of what antibody level would be required to prevent infection.

It’s a high benchmark, but at least investigators now have a clearer sense of the challenge before them.

Also frustrating the HIV vaccine quest is that the virus mutates like mad. Whatever spot on the surface of the virus that antibodies target might be prone to change through mutation, thus allowing the virus to evade their attack. Consequently, researchers search for targets on the virus’ surface that aren’t highly subject to mutation.

Experts also believe warding off the mutation threat will require targeting multiple sites on the virus. So researchers are seeking to develop a portfolio of immune system prompts that would spur production of an array of broadly neutralizing antibodies.

Prompting the development of such antibodies requires a complex, step-by step process of coaxing the infection-fighting B cells, getting them to multiply and then guiding their maturation into potent broadly neutralizing antibody-producing factories.

HIV vaccine development ‘in a better place’

Dr. Carl Dieffenbach, the head of the AIDS division at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said numerous recent technological advances — including mRNA, better animal models of HIV infection and high-tech imaging technology — have improved researchers’ precision in designing, and speed in producing, new proteins to spur anti-HIV immune responses.

Global collaboration among major players is also flourishing, researchers said. There are several early-stage human clinical trials of HIV-vaccine components underway.

Three mRNA- based early human trials of such components have been launched since 2022. Among them, they have been led or otherwise funded by the global vaccine research nonprofit group IAVI, Fred Hutch, Moderna, Scripps Research, the Gates Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and university teams. More such trials are in the works.

On Friday, Science magazine reported concerning recent findings that among the three mRNA trials, a substantial proportion of participants — 7% to 18%, IAVI said in a statement — experienced skin-related symptoms following injections, including hives, itching and welts.

IAVI said in its statement that it and partners are investigating the HIV trials’ skin-related outcomes, most of which were “mild or moderate and managed with simple allergy medications.”

Researchers have shown success in one of those mRNA trials in executing a particular step in the B-cell cultivation process.

That vaccine component also generated “helper” CD4 cells primed to combat HIV. The immune cells are expected to operate like an orchestra conductor for the immune system, coordinating a response by sending instructions to B cells and scaling up other facets of an assault on HIV.

A complementary strategy under investigation seeks to promote the development of “killer” CD8 cells that might be primed to kill off any immune cells that the antibodies failed to save from infection.

Crucially, investigators believe they are now much better able to discern top vaccine component candidates from the duds. They plan to spend the coming years developing such components so that when they do assemble the most promising among them into a multi-pronged vaccine, they can be much more confident of ultimate success in a trial.

“An HIV vaccine could end HIV,” McElrath said at the Denver conference. “So I say, ‘Let’s just get on with it.”

Dr. Mark Feinberg, president and CEO of IAVI, suggested that the first trial to test effectiveness of the vaccine might not launch until 2030 or later.

Even so, he was bullish.

“The field of HIV vaccine development is in a better place now than it’s ever been,” he said.

Benjamin Ryan is independent journalist specializing in science and LGBTQ coverage. He contributes to NBC News, The New York Times, The Guardian and Thomson Reuters Foundation and has also written for The Washington Post, The Nation, The Atlantic and New York.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 28 November 2023

This is how the world finally ends the HIV/AIDS pandemic

- John Nkengasong 0 ,

- Mike Reid 1 &

- Ingrid T. Katz 2

John Nkengasong is the ambassador-at-large, US global AIDS coordinator and senior bureau official for Global Health Security and Diplomacy in the Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy — PEPFAR, US Department of State, Washington DC, USA.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Mike Reid is chief science officer in the Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy — PEPFAR, US Department of State, Washington DC, USA, and an associate professor at the University of California, San Francisco, USA.

Ingrid T. Katz is director for behavioural sciences in the Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy — PEPFAR, US Department of State, Washington DC, USA, and an associate professor at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

People undergo tests for HIV at a mobile outreach clinic in the Kyenjojo District, Uganda. Credit: Jake Lyell/Alamy

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Nearly 30 years ago — more than a decade after HIV/AIDS was first identified — a group of scientists in the United States and France reported impressive results from a clinical trial. Pregnant women living with HIV could reduce the risk of transmitting the virus to their newborn child by around 67% if they took a drug called zidovudine during pregnancy and their infant took it for the first six weeks of life 1 . Five years later, a similar finding was reported in Africa 2 where, at the time, the prevalence of HIV among pregnant women exceeded 35% in several regions.

These studies, and subsequent ones that elucidated how effectively antiretroviral therapy could block parent-to-child transmission of HIV, augured an era of tremendous progress — both towards eliminating such transmission and scaling up access to life-saving treatments for children and adults living with HIV.

Since these landmark studies, 5.5 million children of mothers living with HIV have been born free of the disease . This is due in large part to a programme called the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), created under former US president George W. Bush. Since its inception, PEPFAR, which one of us (J. N.) now leads, has ensured crucial access to life-saving treatment for more than 20 million people in at least 50 countries.

Twenty years after the programme was created, we now have the tools and knowledge to end the HIV/AIDS pandemic as a threat to public health — and to do so by 2030. According to the United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), this would mean reaching the ‘95-95-95’ targets: at least 95% of people living with HIV should know their status; at least 95% of those people should be on life-saving antiretroviral therapy; and at least 95% of those people should have an undetectable viral load 3 . The crucial question is how do we support countries to achieve these goals?

Early efforts to combat HIV/AIDS focused on systems-level changes — the procurement of drugs, training of health workers and the provision of clinics — that were needed to ensure that effective interventions were made available to millions of people. The global health community should continue to ensure sustained investment in these systems-level strategies. But we also have an opportunity to use behavioural-science approaches to reach populations that are most in need. Making people, rather than systems, the core focus of our response is the solution to finally ending the pandemic.

Uphill battle

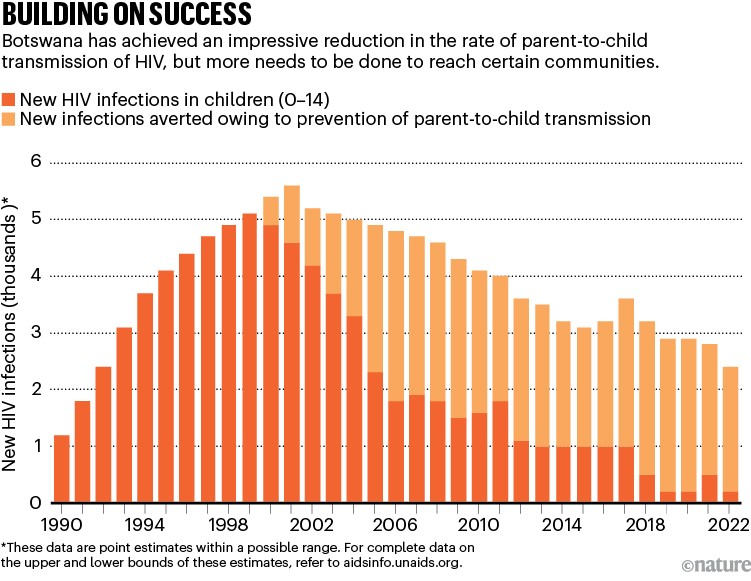

Botswana offers an important model for other countries (see ‘Building on success’). In 2008, 1 in 3 pregnant women aged 15–49 in Botswana were living with HIV 4 . By 2022, prevalence among women aged 15–49 had dropped to around 24% 5 , largely thanks to the government partnering with PEPFAR and other organizations, including civil society and faith-based groups. And in 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Botswana to be the first high-burden country, in which more than 2% of pregnant women are living with the virus, to be on track to eliminating new HIV infections among children .

Source: UNAIDS

Botswana’s achievements stem mainly from efforts to ensure that people living with HIV — and those at greatest risk of contracting the infection — can access life-saving interventions. These include drugs that eliminate the risk of parent-to-child transmission; antiretroviral therapy, which by suppressing the virus, both protects the infected person from severe illness and death, and blocks further transmission; condoms; voluntary male circumcision; and pre-exposure prophylaxis therapy (PrEP), all of which reduce people’s chances of contracting the virus.

But as infection becomes less common globally, it is becoming more challenging to reach the individuals and communities that continue to be severely affected by HIV/AIDS.

Hope rises that a vaccine can shield people with HIV from a deadly threat

Testing is crucial — both to link people to treatment, and to raise awareness about the possible preventive measures available to them and their partners. (Globally, an estimated 5.5 million people are living with HIV but are unaware of their status .) There is also compelling evidence that beginning antiretroviral therapy quickly — ideally on the same day as getting a diagnosis — increases the likelihood of a person taking the therapy, and of continuing to take it throughout their lives 6 .

Numerous barriers, however, prevent people — particularly those who might not be able to access care in current health-care systems — from getting tested and from receiving timely antiretroviral therapy 7 . These include anticipated or encountered stigma and discrimination, both in clinics and in the broader community; the logistical challenges of getting access to care or collecting medication; and the possibility of inciting anger and mistrust in partners or family members. Similarly, those who are most likely to benefit from various prevention strategies often feel the least empowered to access them .

No community left behind

For any one community, one strategy might work better or be more feasible at scale than another. But helping countries to achieve the 95-95-95 targets will require empowering health ministries, clinicians, community health workers and HIV activists to participate in the design of programmes that ensure everyone has access to life-long HIV care that is centred around the needs of individuals.

Most new infections occur in adolescents and young adults. So efforts should prioritize young people — specifically, girls and women aged 15–24 and men aged 25–35. Young people, aged 15–24, account for around 27% of new HIV infections globally. Yet in eastern and southern Africa — the region of the world most severely affected by HIV — only 25% of girls and 17% of boys between the ages of 15 and 19 underwent HIV testing in the past year .

Efforts should also continue to prioritize those who would benefit most from preventive treatments such as PrEP, including girls and women, sex workers and members of the LGBT+ community (people from sexual and gender minorities). These people might not be aware that they are at high risk of contracting HIV, or realize the degree to which PrEP could protect them 8 .

A youth-run HIV/AIDS centre provides counselling and testing in Bongor, Chad. Credit: Micah Albert/Redux/eyevine

Several studies over the past decade have indicated that young people, and others at greater risk of fearing and experiencing stigmatization and discrimination, benefit from having choices. They need to be able to select the combination of prevention or treatment interventions, the medication pick-up location and the frequency with which they take the drugs that work best for them 9 . But establishing youth-friendly health services can also help with this. This might entail training and supporting staff to better understand the decision-making processes, sensitivities and perspectives of young people — or providing services that are easy for young people to access while juggling school, employment, family responsibilities and so on 10 .

In a study published earlier this year, for example, researchers offered girls and women aged 18–25 information to help them with decision-making in a primary health clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. The information package included youth-friendly information and images of various prevention interventions. The uptake of PrEP among this group was more than 90%, and after one month, twice as many people were continuing to take it, compared with the group who received standard counselling 11 .

Third patient free of HIV after receiving virus-resistant cells

Evidence-based strategies to reduce stigma are also crucial — especially for those experiencing discrimination on multiple fronts, for instance because of their age, gender, sexuality, HIV status or ethnicity. At the community and individual level, these strategies can involve using social networks to spread messages about interventions or recruiting people who have experienced their own challenges while living with HIV to talk to and motivate others. Independent monitoring of the quality of care received by those living with HIV is also key to improving services and lessening stigma and discrimination 12 .

As new prevention tools, such as the drug cabotegravir — which protects people from HIV infection for up to two months after being injected into the body — become more widely available, health-care schemes must be designed so that those who are most likely to benefit from an intervention can access it.

Changing behaviour

Whether in relation to testing, antiretroviral therapy or PrEP and other prevention interventions, incorporating behavioural and social science into the design of health-care programmes — and making this incorporation mainstream — will be essential.

A good example of the importance of behavioural interventions comes from South Africa, where men are significantly less likely than women to seek HIV testing or engage in care, and health and social-welfare systems have failed to achieve the UNAIDS 95-95-95 goals for men 13 . In 2020, researchers provided 500 men in Cape Town with a card containing information about how antiretroviral therapy can prevent an infected person from passing HIV to their partner or family and inviting them to get HIV testing at a mobile clinic. The messaging strategy almost doubled the number of men who came to the mobile clinic for free HIV testing 14 .

A meta-analysis by another group, which included data from 47 studies conducted around the world 13 , showed that leveraging social networks to improve case finding (the discovery of new cases and the determination of who is at risk) is a useful and cost-effective way to reach adolescents and youth . Leveraging social networks involves identifying certain people as being important in a social network, and then encouraging them to motivate sexual partners or those in their social networks, who might benefit from testing, to test for HIV. Partly because of the results of the meta-analysis, the WHO now recommends that countries increase their use of testing approaches that utilize social networks .

Several mutually reinforcing interventions that support people to change their behaviour can help to reduce the time between diagnosis and a person starting antiretroviral treatment. These approaches include providing people who have tested positive for HIV with text messages and other reminders to make appointments at their local clinic; ensuring that people can get to the clinic by public transport; and providing incentives, such as monetary rewards, for starting treatment 15 .

Future focus

Investing in innovative strategies that meet the needs of individuals won’t just be key to ending the HIV/AIDS pandemic by 2030. It will also help to ensure that global health systems are resilient and dynamic in the face of future public-health threats. And it will help to shift the focus of global health, so that solutions to problems for tackling disease increasingly come from the individuals and communities that are most affected, and less from high-income countries.

Nature 623 , 907-909 (2023)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03715-x

Connor, E. M. et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 331 , 1173–1180 (1994).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Wiktor, S. Z. et al. Lancet 353 , 781–785 (1999).

Frescura, L. et al. PLoS ONE 17 , e0272405 (2022).

Sullivan, E., Drobac, P., Thompson, K. & Rodriguez, W. Botswana’s Program in Preventing Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission (Harvard Business Publishing, 2011).

Google Scholar

National AIDS & Health Promotion Agency. The Fifth Botswana AIDS Impact Survey 2021 (Government of Botswana, 2021).

Labhardt, N. D. et al. JAMA 319 , 1103–1112 (2018).

Hlongwa, M. et al. Am. J. Mens Health https://doi.org/10.1177/15579883221120987 (2022).

Article Google Scholar

Sullivan, P. S., Mena, L., Elopre, L. & Siegler, A. J. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep . 16 , 259–269 (2019).

Ngure, K. et al. Lancet HIV 9 , e464–e473 (2022).

Cluver, L. et al. AIDS 35 , 1263–1271 (2021).

Celum, C. et al. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 26 , e26154 (2023).

UNAIDS. Establishing Community-led Monitoring of HIV Services (UNAIDS, 2021).

Nardell, M. F. et al. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 25 , e25889 (2022).

Smith, P. et al. AIDS Behav. 25 , 3128–3136 (2021).

Dovel, K. L. et al. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 28 , 454–465 (2023).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Related Articles

you must enter a null

- HIV infections

- Public health

Stunning trial shows twice-yearly shots can prevent HIV infection

Research Highlight 02 AUG 24

Seventh patient ‘cured’ of HIV: why scientists are excited

News 26 JUL 24

Blockbuster obesity drug leads to better health in people with HIV

News 11 MAR 24

How I’m looking to medicine’s past to heal hurt and support peace in the Middle East

World View 15 AUG 24

‘Unacceptable’: a staggering 4.4 billion people lack safe drinking water, study finds

News 15 AUG 24

What is the hottest temperature humans can survive? These labs are redefining the limit

News 14 AUG 24

Growing mpox outbreak prompts WHO to declare global health emergency

News 13 AUG 24

The pathogens that could spark the next pandemic

News 02 AUG 24

Your nose has its own army of immune cells — here’s how it protects you

News 31 JUL 24

Faculty Positions in Center of Bioelectronic Medicine, School of Life Sciences, Westlake University

SLS invites applications for multiple tenure-track/tenured faculty positions at all academic ranks.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

School of Life Sciences, Westlake University

Faculty Positions, Aging and Neurodegeneration, Westlake Laboratory of Life Sciences and Biomedicine

Applicants with expertise in aging and neurodegeneration and related areas are particularly encouraged to apply.

Westlake Laboratory of Life Sciences and Biomedicine (WLLSB)

Faculty Positions in Chemical Biology, Westlake University

We are seeking outstanding scientists to lead vigorous independent research programs focusing on all aspects of chemical biology including...

Assistant Professor Position in Genomics

The Lewis-Sigler Institute at Princeton University invites applications for a tenure-track faculty position in Genomics.

Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, US

The Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton University

Associate or Senior Editor, BMC Medical Education

Job Title: Associate or Senior Editor, BMC Medical Education Locations: New York or Heidelberg (Hybrid Working Model) Application Deadline: August ...

New York City, New York (US)

Springer Nature Ltd

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

IMAGES