- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Thomas G. Carpenter Library

Conducting a Literature Review

Benefits of conducting a literature review.

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Summary of the Process

- Additional Resources

- Literature Review Tutorial by American University Library

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It by University of Toronto

- Write a Literature Review by UC Santa Cruz University Library

While there might be many reasons for conducting a literature review, following are four key outcomes of doing the review.

Assessment of the current state of research on a topic . This is probably the most obvious value of the literature review. Once a researcher has determined an area to work with for a research project, a search of relevant information sources will help determine what is already known about the topic and how extensively the topic has already been researched.

Identification of the experts on a particular topic . One of the additional benefits derived from doing the literature review is that it will quickly reveal which researchers have written the most on a particular topic and are, therefore, probably the experts on the topic. Someone who has written twenty articles on a topic or on related topics is more than likely more knowledgeable than someone who has written a single article. This same writer will likely turn up as a reference in most of the other articles written on the same topic. From the number of articles written by the author and the number of times the writer has been cited by other authors, a researcher will be able to assume that the particular author is an expert in the area and, thus, a key resource for consultation in the current research to be undertaken.

Identification of key questions about a topic that need further research . In many cases a researcher may discover new angles that need further exploration by reviewing what has already been written on a topic. For example, research may suggest that listening to music while studying might lead to better retention of ideas, but the research might not have assessed whether a particular style of music is more beneficial than another. A researcher who is interested in pursuing this topic would then do well to follow up existing studies with a new study, based on previous research, that tries to identify which styles of music are most beneficial to retention.

Determination of methodologies used in past studies of the same or similar topics. It is often useful to review the types of studies that previous researchers have launched as a means of determining what approaches might be of most benefit in further developing a topic. By the same token, a review of previously conducted studies might lend itself to researchers determining a new angle for approaching research.

Upon completion of the literature review, a researcher should have a solid foundation of knowledge in the area and a good feel for the direction any new research should take. Should any additional questions arise during the course of the research, the researcher will know which experts to consult in order to quickly clear up those questions.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2022 8:54 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/litreview

A Guide to Literature Reviews

Importance of a good literature review.

- Conducting the Literature Review

- Structure and Writing Style

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Citation Management Software This link opens in a new window

- Acknowledgements

A literature review is not only a summary of key sources, but has an organizational pattern which combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

- << Previous: Definition

- Next: Conducting the Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 3:13 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mcmaster.ca/litreview

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Literature Review - what is a Literature Review, why it is important and how it is done

What are literature reviews, goals of literature reviews, types of literature reviews, about this guide/licence.

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Literature Reviews and Sources

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

- Useful Resources

Help is Just a Click Away

Search our FAQ Knowledge base, ask a question, chat, send comments...

Go to LibAnswers

What is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries. " - Quote from Taylor, D. (n.d) "The literature review: A few tips on conducting it"

Source NC State University Libraries. This video is published under a Creative Commons 3.0 BY-NC-SA US license.

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review?

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

- Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1997). "Writing narrative literature reviews," Review of General Psychology , 1(3), 311-320.

When do you need to write a Literature Review?

- When writing a prospectus or a thesis/dissertation

- When writing a research paper

- When writing a grant proposal

In all these cases you need to dedicate a chapter in these works to showcase what have been written about your research topic and to point out how your own research will shed a new light into these body of scholarship.

Literature reviews are also written as standalone articles as a way to survey a particular research topic in-depth. This type of literature reviews look at a topic from a historical perspective to see how the understanding of the topic have change through time.

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

- Narrative Review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Book review essays/ Historiographical review essays : This is a type of review that focus on a small set of research books on a particular topic " to locate these books within current scholarship, critical methodologies, and approaches" in the field. - LARR

- Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L.K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

- Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M.C. & Ilardi, S.S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

- Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). "Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts," Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53(3), 311-318.

Guide adapted from "Literature Review" , a guide developed by Marisol Ramos used under CC BY 4.0 /modified from original.

- Next: Strategies to Find Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 10:56 AM

- URL: https://lit.libguides.com/Literature-Review

The Library, Technological University of the Shannon: Midwest

Frequently asked questions

What is the purpose of a literature review.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

Frequently asked questions: Academic writing

A rhetorical tautology is the repetition of an idea of concept using different words.

Rhetorical tautologies occur when additional words are used to convey a meaning that has already been expressed or implied. For example, the phrase “armed gunman” is a tautology because a “gunman” is by definition “armed.”

A logical tautology is a statement that is always true because it includes all logical possibilities.

Logical tautologies often take the form of “either/or” statements (e.g., “It will rain, or it will not rain”) or employ circular reasoning (e.g., “she is untrustworthy because she can’t be trusted”).

You may have seen both “appendices” or “appendixes” as pluralizations of “ appendix .” Either spelling can be used, but “appendices” is more common (including in APA Style ). Consistency is key here: make sure you use the same spelling throughout your paper.

The purpose of a lab report is to demonstrate your understanding of the scientific method with a hands-on lab experiment. Course instructors will often provide you with an experimental design and procedure. Your task is to write up how you actually performed the experiment and evaluate the outcome.

In contrast, a research paper requires you to independently develop an original argument. It involves more in-depth research and interpretation of sources and data.

A lab report is usually shorter than a research paper.

The sections of a lab report can vary between scientific fields and course requirements, but it usually contains the following:

- Title: expresses the topic of your study

- Abstract: summarizes your research aims, methods, results, and conclusions

- Introduction: establishes the context needed to understand the topic

- Method: describes the materials and procedures used in the experiment

- Results: reports all descriptive and inferential statistical analyses

- Discussion: interprets and evaluates results and identifies limitations

- Conclusion: sums up the main findings of your experiment

- References: list of all sources cited using a specific style (e.g. APA)

- Appendices: contains lengthy materials, procedures, tables or figures

A lab report conveys the aim, methods, results, and conclusions of a scientific experiment . Lab reports are commonly assigned in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .

If you’ve gone over the word limit set for your assignment, shorten your sentences and cut repetition and redundancy during the editing process. If you use a lot of long quotes , consider shortening them to just the essentials.

If you need to remove a lot of words, you may have to cut certain passages. Remember that everything in the text should be there to support your argument; look for any information that’s not essential to your point and remove it.

To make this process easier and faster, you can use a paraphrasing tool . With this tool, you can rewrite your text to make it simpler and shorter. If that’s not enough, you can copy-paste your paraphrased text into the summarizer . This tool will distill your text to its core message.

Revising, proofreading, and editing are different stages of the writing process .

- Revising is making structural and logical changes to your text—reformulating arguments and reordering information.

- Editing refers to making more local changes to things like sentence structure and phrasing to make sure your meaning is conveyed clearly and concisely.

- Proofreading involves looking at the text closely, line by line, to spot any typos and issues with consistency and correct them.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

In a scientific paper, the methodology always comes after the introduction and before the results , discussion and conclusion . The same basic structure also applies to a thesis, dissertation , or research proposal .

Depending on the length and type of document, you might also include a literature review or theoretical framework before the methodology.

Whether you’re publishing a blog, submitting a research paper , or even just writing an important email, there are a few techniques you can use to make sure it’s error-free:

- Take a break : Set your work aside for at least a few hours so that you can look at it with fresh eyes.

- Proofread a printout : Staring at a screen for too long can cause fatigue – sit down with a pen and paper to check the final version.

- Use digital shortcuts : Take note of any recurring mistakes (for example, misspelling a particular word, switching between US and UK English , or inconsistently capitalizing a term), and use Find and Replace to fix it throughout the document.

If you want to be confident that an important text is error-free, it might be worth choosing a professional proofreading service instead.

Editing and proofreading are different steps in the process of revising a text.

Editing comes first, and can involve major changes to content, structure and language. The first stages of editing are often done by authors themselves, while a professional editor makes the final improvements to grammar and style (for example, by improving sentence structure and word choice ).

Proofreading is the final stage of checking a text before it is published or shared. It focuses on correcting minor errors and inconsistencies (for example, in punctuation and capitalization ). Proofreaders often also check for formatting issues, especially in print publishing.

The cost of proofreading depends on the type and length of text, the turnaround time, and the level of services required. Most proofreading companies charge per word or page, while freelancers sometimes charge an hourly rate.

For proofreading alone, which involves only basic corrections of typos and formatting mistakes, you might pay as little as $0.01 per word, but in many cases, your text will also require some level of editing , which costs slightly more.

It’s often possible to purchase combined proofreading and editing services and calculate the price in advance based on your requirements.

There are many different routes to becoming a professional proofreader or editor. The necessary qualifications depend on the field – to be an academic or scientific proofreader, for example, you will need at least a university degree in a relevant subject.

For most proofreading jobs, experience and demonstrated skills are more important than specific qualifications. Often your skills will be tested as part of the application process.

To learn practical proofreading skills, you can choose to take a course with a professional organization such as the Society for Editors and Proofreaders . Alternatively, you can apply to companies that offer specialized on-the-job training programmes, such as the Scribbr Academy .

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Email [email protected]

- Start live chat

- Call +1 (510) 822-8066

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Our team helps students graduate by offering:

- A world-class citation generator

- Plagiarism Checker software powered by Turnitin

- Innovative Citation Checker software

- Professional proofreading services

- Over 300 helpful articles about academic writing, citing sources, plagiarism, and more

Scribbr specializes in editing study-related documents . We proofread:

- PhD dissertations

- Research proposals

- Personal statements

- Admission essays

- Motivation letters

- Reflection papers

- Journal articles

- Capstone projects

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker is powered by elements of Turnitin’s Similarity Checker , namely the plagiarism detection software and the Internet Archive and Premium Scholarly Publications content databases .

The add-on AI detector is powered by Scribbr’s proprietary software.

The Scribbr Citation Generator is developed using the open-source Citation Style Language (CSL) project and Frank Bennett’s citeproc-js . It’s the same technology used by dozens of other popular citation tools, including Mendeley and Zotero.

You can find all the citation styles and locales used in the Scribbr Citation Generator in our publicly accessible repository on Github .

University Libraries University of Nevada, Reno

- Skill Guides

- Subject Guides

Literature Reviews

- Searching for Literature

- Organizing Literature and Taking Notes

- Writing and Editing the Paper

- Help and Resources

Book an Appointment

What Is a Literature Review?

A literature review surveys and synthesizes the scholarly research literature related to a particular topic. Literature reviews both explain research findings and analyze the quality of the research in order to arrive at new insights.

Literature reviews may describe not only the key research related to a topic of inquiry but also seminal sources, influential scholars, key theories or hypotheses, common methodologies used, typical questions asked, or common patterns of inquiry.

There are different types of literature reviews. A narrative literature review summarizes and synthesizes the findings of numerous research articles, but the purpose and scope of narrative literature reviews vary widely. The term "literature review" is most commonly used to refer to narrative literature reviews, and these are the types of works that are described in this guide.

Some types of literature reviews that use prescribed methods for identifying and evaluating evidence-based literature related to specific questions are known as systematic reviews or meta-analyses . Systematic reviews or meta-analyses are typically conducted by at least two scholars working in collaboration as prescribed by certain guidelines, but narrative literature reviews may be conducted by authors working alone.

Purpose of a Literature Review

Literature reviews serve an important function in developing the scholarly record. Because of the vast amount of scholarly literature that exists, it can be difficult for readers to keep up with the latest developments related to a topic, or to discern which ideas, themes, authors, or methods are worthy of more attention. Literature reviews help readers to understand and make sense of a large body of scholarship.

Literature reviews also play an important function in assessing the quality of the evidence base in relation to a particular topic. Literature reviews contain assessments of the evidence in support of particular interventions, policies, programs, or treatments.

The literature that is reviewed may include a variety of types of research, including empirical research, theoretical works, and reports of practical application. The scholarly works that are considered for inclusion in a literature review may appear in a variety of publication types, including scholarly journals, books, conference proceedings, reports, and others.

Steps in the Process

Follow these steps to conduct your literature review:

- Select a topic and prepare for searching. Formulate a research question and establish inclusion and exclusion criteria for your search.

- Search for and organize the research. Use tools like the library website, library-subscription databases, Google Scholar, and others to locate research on your topic.

- Organize your research, read and evaluate it, and take notes. Use organizational and note-taking strategies to read sources and prepare for writing.

- Write and edit the paper. Synthesize information from sources to arrive at new insights.

Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students

View the video below for an overview of the process of writing literature review papers.

Video: Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students by libncsu

- Next: Searching for Literature >>

Explore Academics

Literature Review in Research: 14 key benefits

- X (Twitter)

Last updated on July 26th, 2024 at 06:20 am

A literature review in research forms the foundation of your study and provides a framework to build your research. By reviewing existing research, you get a well-rounded understanding of the field, which helps enhance your study.

What is a Literature Review in Research

A literature review in research gives a detailed summary of studies in a specific field. It involves a critical analysis of these studies, focusing on their depth and the effectiveness of their methodologies, and is crucial for enhancing your research work.

Key Benefits of a Literature Review

A literature review will benefit experienced researchers and beginners alike to write more effective research papers based on strong principles and maintain the highest levels of academic integrity and ethicality.

1. Analyzing Theories and Concepts

The literature review in research helps you understand the key theories and concepts in your field. It broadens your knowledge and helps you position your research within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Evaluating Existing Research

By evaluating existing research, you can identify the strengths and weaknesses of previous studies. This helps establish the credibility of your research and shows where improvements can be made.

3. Identifying Research Gaps

By writing a literature review in research helps you see what has already been researched and what hasn’t. Identifying these gaps allows you to find areas where more research is needed, providing opportunities to explore new topics for your research paper.

4. Providing a Detailed Roadmap

Understanding the gaps in existing research gives you a clear direction for your study. You can use this roadmap to position your research to fill these gaps or to develop new concepts.es you a clear direction for your study.

5. Choosing a Research Topic

Reviewing literature can inspire new research topics. It helps you find areas that are impactful and worth exploring further.

6. Expanding The Methodology Base

As you evaluate different studies, you’ll learn about various methodologies used for data collection and analysis. This knowledge can help you choose the best research methodology for your research.

7. Analyzing Strengths and Weaknesses

After reviewing multiple papers, you’ll gain a better perspective on what makes a study strong or weak. This insight is crucial for improving the quality of your research.

8. Assessing The Research Processes

By examining the methodology sections of other studies, you can learn about different research processes and how they can be applied to your work.

9. Refining Your Research Questions and Objectives

A literature review in research helps you refine your research questions and objectives. By synthesizing key concepts and theoretical frameworks, you can develop well-informed research questions.

10. Designing a Robust and Effective Study

With the insights gained from your literature review, you can make informed decisions about data collection and sampling techniques, ensuring a robust methodology for your study.

11. Staying Abreast with Latest Developments

A literature review in research keep you updated on the latest trends and emerging theories in your field, helping you stay relevant and informed.

12. Defending or Challenging Existing Concepts

Reviewing existing research allows you to critically assess the evidence supporting or challenging current concepts. This can guide you in deciding whether further research is needed.

13. Providing Practical Insights

While composing a literature review in research, you gain practical insights into the best practices and methodologies used by other researchers, which you can apply to your study.

14. Preventing Duplication

A thorough literature review in research ensures that your study is original and not a duplication of existing studies. This is crucial to maintaining academic integrity and avoiding plagiarism.

FAQ’s

What is the meaning of literature review in research.

A literature review is a summary of a subject field that supports the identification of specific research questions. A literature review needs to draw on and evaluate a range of different types of sources including academic and professional journal articles, books, and web-based resources.

What is a good literature review in research?

A good review should critically examine the methodological problems, and identify research gaps. After reading a literature review in research, a reader should have a decent idea of the important components in the reviewed field,

What is the format for a literature review in research?

Most literature reviews must include a few sentences in the introduction section, a detailed analysis in the body section, and a few sentences in the conclusion

In conclusion, a literature review in research is like a roadmap for your research journey. It helps you understand the existing landscape, identify gaps in knowledge, and refine your research question. By learning from previous studies and methodologies, you can develop a more focused and impactful research project.

So, the next time you embark on a research project, remember – a thorough literature review is the key to building a strong foundation for your work!

My journey in academia began as a dedicated researcher, specializing in the fascinating world of biochemistry. Over the years, I’ve had the privilege of mentoring Master’s and PhD students, collaborating on research papers that pushed the boundaries of knowledge. Now, post-retirement, I’ve embarked on a new chapter, sharing my academic expertise through freelance work on platforms like YouTube and Upwork. Here, I delve into the finer points of academic research, guiding aspiring writers through the intricacies of formatting, crafting compelling narratives, and navigating the publication process.

You May Also Like

How to write a literature review using chatgpt.

How To Write A Research Paper Outline Expertly

Importance of Research Methodology: With Examples

University Libraries

Literature review.

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is Its Purpose?

- 1. Select a Topic

- 2. Set the Topic in Context

- 3. Types of Information Sources

- 4. Use Information Sources

- 5. Get the Information

- 6. Organize / Manage the Information

- 7. Position the Literature Review

- 8. Write the Literature Review

A literature review is a comprehensive summary of previous research on a topic. The literature review surveys scholarly articles, books, and other sources relevant to a particular area of research. The review should enumerate, describe, summarize, objectively evaluate and clarify this previous research. It should give a theoretical base for the research and help you (the author) determine the nature of your research. The literature review acknowledges the work of previous researchers, and in so doing, assures the reader that your work has been well conceived. It is assumed that by mentioning a previous work in the field of study, that the author has read, evaluated, and assimiliated that work into the work at hand.

A literature review creates a "landscape" for the reader, giving her or him a full understanding of the developments in the field. This landscape informs the reader that the author has indeed assimilated all (or the vast majority of) previous, significant works in the field into her or his research.

"In writing the literature review, the purpose is to convey to the reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. The literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (eg. your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries.( http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/specific-types-of-writing/literature-review )

Recommended Reading

- Next: What is Its Purpose? >>

- Last Updated: Oct 2, 2023 12:34 PM

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Jul 15, 2024 10:34 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 8, 2024 11:22 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

- Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Assignment Help

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

Why Is Literature Review Important? (3 Benefits Explained)

by Antony W

June 26, 2024

Every research project needs a literature review. And while it’s one of the most challenging parts of the assignment, in part because of the intensity of the research involved, it’s by far the most important section of a research paper.

Many students fail to write comprehensive literature reviews because they see the assignment as a formality.

For the most part, they’ll vaguely create a list of existing studies and consider the assignment complete. But such an approach overlooks why a literature review is important.

We need to take a step back and look beyond the definition of a literature review.

In particular, the goal of this guide is to help you explore the significance of the review of the existing literature.

Once you understand the role that literature reviews play in research projects, you’ll give the assignment the full attention that it deserves.

Key Takeaways

Writing a literature review is important for the following reasons:

- It demonstrates that you understand the issue you’re investigating.

- A literature review allows you to develop a more theoretical framework for your research.

- It justifies your research and shows the gaps present in the current literature.

Get Literature Review Writing Help

Do you find the workload involved in writing a literature review for your thesis, research paper, or standalone project overwhelming? We understand how involving the writing process can be, and we are here to help you with writing if you currently feel stuck.

You can hire a professional literature review writer from Help for Assessment to get the writing done for you. Whether you have a flexible deadline or the submission date for the literature is almost due, you can count on our team to help you get the paper done fast.

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a study of the already existing research in a given area of study.

While it’s common in physical and social sciences, instructors may also request student to complete the assignment within the humanities space.

The review can be a standalone project or a part of an academic assignment.

If your professor or instructor asks you to write the review as a standalone project, your focus will be on exploring how a specific field of inquiry has developed over the course of time.

In the case where you have to include the review as part of your academic paper, the goal will be to set the background for the topic (or issue) you’re currently investigating.

How is Literature Review Different from an Essay?

In an education setting whether students are used to writing tons of essays every month, it’s likely for many to wonder whether an essay could be the same as a literature review.

While a literature review and an essay both require research before writing, there are a number of differences between them that you need to know.

Types of Literature Review

We’ll look at the significance of a literature review in a moment.

For now let’s look at the types of literature reviews that your instructor may ask you to write.

As of this writing, there are 6 types of reviews that you need to know about. These are:

1. Argumentative Review

Examines a literature review with the intention to support or refuse an argument, with the aim being to develop a body of literature that can establish a contrarian point of view.

2. Integrative Literature Review

This type of review critiques and synthesizes related literature to generate a new framework and perspective on a topic.

Researchers have to address identical and/or related hypotheses or research problems to comply with research standards with regards to replication, vigor, and clarity.

3. Historical Literature

The focus of the review is to examine research within a given period, and usually starts from the time a research problem or issue emerged.

Then, you have to trace its evolution throughout the suggested timeframe within the scholarship of that particular discipline.

4. Methodological Literature Review

The focus shifts from what someone said to how they ended up saying what they said.

Since the focus here is on the method of analysis , methodological reviews gives a better framework that help one to understand exactly how a researcher draws their conclusion from a wide range of knowledge.

5. Systematic Literature

A systematic review focuses on the existing evidence related to a specific research question.

You will need to use a pre-specified and standardized approach to identify, evaluate, and appraise research, not to mention collect, analyze, and report data collected from the review.

Understand that the goal of a systematic review is to evaluate, summarize, and document research that focuses on a specific (or clearly defined) research problem.

6. Theoretical Literature Review

Theoretical review focuses on examining theories that resulted from an issue, a concept, or a situation.

It’s through this type of review that a researcher can easily establish the kind of theories that already formulated, the degree to what researchers have investigated them, and the relationship between them.

It’s through theoretical review that one can develop new hypotheses for testing and can therefore help to determine what theories aren’t sufficient to explain emerging research problems.

Why Is Literature Review Important?

Now that you know the difference between an essay and a review as well as the different types of literature review, it’s important to look at why it’s important to examine existing literature in your research.

There are a number of reasons why instructors ask you to write a review , and they’re as follow:

1. Demonstrate a Clear Understanding of the Subject

Writing a literature review demonstrates that you have a clear understanding of the subject you’re investigating.

It also means that you can easily identify, evaluate, and summarize existing research that’s relevant to your work.

2. Justify Your Research

There’s more to writing a research paper than just identifying topic and generating your research question from it.

You also have to go as far as to justify your research, and the only way to do that is by including a literature review in your work.

It’s important to understand that looking at past research is the only way to identify gaps that exist in the current literature.

That can go a long way to help fill in the gap by addressing them in your own research work.

3. Helps to Set a Resourceful Theoretical Framework

Because a research paper assignment builds up on the ideas of already existing research, doing a literature review can help you to set a resourceful theoretical framework on which to base your study.

The theoretical framework will include concepts and theories that you will base your research on. And keep in mind that it’s this framework that professors will use to judge the overall quality of your work.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. what are the benefits of literature review in research.

A literature review in research allows you to discover exiting knowledge in your field and the boundaries and limitations that exists within that field.

Moreover, doing a review of existing literature helps you to understand the theories that drive an area of investigation, making it easy for you to place your research question into proper context.

2. What is the Effect of a Good Literature Review?

In addition to providing context, reducing research redundancy, and informing methodology, a well-written literature review can maximize relevance, enhance originality, and ensure professional standards in writing.

3. What is a Strength of a Literature Review?

The strength of a literature review is the ability to improve your information seeking skills and enhancing your knowledge about the topic under investigation.

As you can see, a review is quite a significant part of a research project, so you should treat it with the seriousness that it deserves.

At the end of the day, you want to create a good connection between you and your readers, and the best way to do that is to pack just as much value as you can in your literature review project.

About the author

Antony W is a professional writer and coach at Help for Assessment. He spends countless hours every day researching and writing great content filled with expert advice on how to write engaging essays, research papers, and assignments.

Home of Mass Communication Project Topics in Nigeria

No.1 Mass Communication Research Topics and Materials

BENEFITS OF LITERATURE REVIEW TO RESEARCH

Introduction.

Literature review offers lots of benefits to researcher. However, for the purpose of this post I will like to be direct. Below are few benefits of Literature review to researchers:

- A thorough exploration of the literature review will help to articulate our own research problems, objectives, as well as formulating our research questions or hypothesis.

- It helps to know the existing GAPS

- It helps to notices the important concepts and variables and how they were operationalized

- It widens the researcher knowledge of the problem

- It gives researchers detailed knowledge of the method and design that he can adopt or use new ones.

- It helps the researcher to arrive at picking a suitable scope

- It suggested theories previously used

Related Project Topics:

Influence of artificial intelligence on practice of public relations in nigeria.

(Last Updated On: ) Abstract: This study explores the influence of Artificial Intelligence on the practice of public relations in Nigeria, employing a cross-sectional survey

PERCEIVED EFFECTS OF AI ON JOURNALISM ETHICS PRACTICE IN NIGERIA

(Last Updated On: ) Abstract: This study explores the perceived effects of Ai on journalism ethics in Nigeria, employing a cross-sectional survey research method. The

INFLUENCE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN JOURNALISM INDUSTRY IN NIGERIA

(Last Updated On: ) Abstract: This study investigates the transformative influence of Artificial Intelligence in journalism industry in Nigeria. Employing a quantitative research method, the

EFFECTIVENESS OF THE INTERNET AS A TOOL FOR RESEARCH AND ASSIGNMENT AMONG STUDENTS

(Last Updated On: ) Abstract: This study investigates the effectiveness of the Internet as a tool for research and assignments among students. Guided by the

UTILIZATION OF INTERNET AS RESEARCH TOOL AMONG UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS

(Last Updated On: ) Abstract: The study was to investigate the utilization of internet as research tool among undergraduate students. The study was anchored on

Impact of ChatGPT on Writing Skills among Nigerian University Students

(Last Updated On: ) Abstract: This study examines the impact of ChatGPT on writing skills among University students, framed within the context of the Technological

IMPACT OF PROSTATE CANCER AWARENESS CAMPAIGNS ON THE KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDES, AND PRACTICES (KAP) AMONG MALE LECTURERS

(Last Updated On: ) Abstract: Prostate cancer, a leading cause of cancer mortality among men, is significantly prevalent in Nigeria. Despite its high incidence, awareness

USE OF NEW MEDIA AS A BUSINESS TOOL AMONG UNDERGRADUATES IN NIGERIA

(Last Updated On: ) ABSTRACT: This study examined the use of new media as a business tool among undergraduates in Nigeria. This research project specifically

PERCEPTION OF SOCIAL MEDIA ON THE 2023 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION

(Last Updated On: ) Abstract: The core objective of the study is to examine the perception of social media on the 2023 presidential election with a

ASSESSMENT OF IMPLICATION OF OPEN DEFECATION ON HEALTH OF PEOPLE IN RURAL AREAS

(Last Updated On: ) Abstract: The core objective of the study is assesses implications of open defecation on health of people living in rural areas:

Influence of Social Media on Social Capital

(Last Updated On: ) ABSTRACT: The study is on the thrust to examined the influence of social media on social capital. This study was anchored

INFLUENCE OF SOCIAL MEDIA ON LIFESTYLE OF YOUTH

(Last Updated On: ) ABSTRACT: This study explores the influence of social media on lifestyle of youth. Given the pervasive use of platforms such as

Call : 08033061386, Whatsapp : 07033401559, Email : [email protected]

Address: No. 2, His Grace Shopping Complex, Ramat Junction, Ayeekale, Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria.

- Open access

- Published: 25 July 2024

Strategies to strengthen the resilience of primary health care in the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review

- Ali Mohammad Mosadeghrad 1 ,

- Mahnaz Afshari 2 ,

- Parvaneh Isfahani 3 ,

- Farahnaz Ezzati 4 ,

- Mahdi Abbasi 4 ,

- Shahrzad Akhavan Farahani 4 ,

- Maryam Zahmatkesh 5 &

- Leila Eslambolchi 4

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 841 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Primary Health Care (PHC) systems are pivotal in delivering essential health services during crises, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. With varied global strategies to reinforce PHC systems, this scoping review consolidates these efforts, identifying and categorizing key resilience-building strategies.

Adopting Arksey and O'Malley's scoping review framework, this study synthesized literature across five databases and Google Scholar, encompassing studies up to December 31st, 2022. We focused on English and Persian studies that addressed interventions to strengthen PHC amidst COVID-19. Data were analyzed through thematic framework analysis employing MAXQDA 10 software.

Our review encapsulated 167 studies from 48 countries, revealing 194 interventions to strengthen PHC resilience, categorized into governance and leadership, financing, workforce, infrastructures, information systems, and service delivery. Notable strategies included telemedicine, workforce training, psychological support, and enhanced health information systems. The diversity of the interventions reflects a robust global response, emphasizing the adaptability of strategies across different health systems.

Conclusions

The study underscored the need for well-resourced, managed, and adaptable PHC systems, capable of maintaining continuity in health services during emergencies. The identified interventions suggested a roadmap for integrating resilience into PHC, essential for global health security. This collective knowledge offered a strategic framework to enhance PHC systems' readiness for future health challenges, contributing to the overall sustainability and effectiveness of global health systems.

Peer Review reports

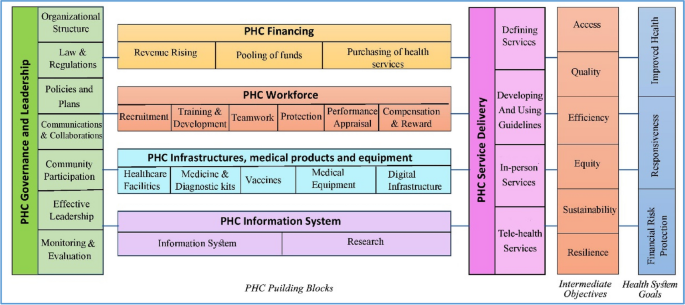

The health system is a complex network that encompasses individuals, groups, and organizations engaged in policymaking, financing, resource generation, and service provision. These efforts collectively aim to safeguard and enhance people health, meet their expectations, and provide financial protection [ 1 ]. The World Health Organization's (WHO) framework outlines six foundational building blocks for a robust health system: governance and leadership, financing, workforce, infrastructure along with technologies and medicine, information systems, and service delivery. Strengthening these elements is essential for health systems to realize their objectives of advancing and preserving public health [ 2 ].

Effective governance in health systems encompasses the organization of structures, processes, and authority, ensuring resource stewardship and aligning stakeholders’ behaviors with health goals [ 3 ]. Financial mechanisms are designed to provide health services without imposing financial hardship, achieved through strategic fund collection, management and allocation [ 4 , 5 ]. An equitable, competent, and well-distributed health workforce is crucial in delivering healthcare services and fulfilling health system objectives [ 2 ]. Access to vital medical supplies, technologies, and medicines is a cornerstone of effective health services, while health information systems play a pivotal role in generating, processing, and utilizing health data, informing policy decisions [ 2 , 5 ]. Collectively, these components interact to offer quality health services that are safe, effective, timely, affordable, and patient-centered [ 2 ]

The WHO, at the 1978 Alma-Ata conference, introduced primary health care (PHC) as the fundamental strategy to attain global health equity [ 6 ]. Subsequent declarations, such as the one in Astana in 2018, have reaffirmed the pivotal role of PHC in delivering high-quality health care for all [ 7 ]. PHC represents the first level of contact within the health system, offering comprehensive, accessible, community-based care that is culturally sensitive and supported by appropriate technology [ 8 ]. Essential care through PHC encompasses health education, proper nutrition, access to clean water and sanitation, maternal and child healthcare, immunizations, treatment of common diseases, and the provision of essential drugs [ 6 ]. PHC aims to provide protective, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative services that are as close to the community as possible [ 9 ].

Global health systems, however, have faced significant disruptions from various shocks and crises [ 10 ], with the COVID-19 pandemic being a recent and profound example. The pandemic has stressed health systems worldwide, infecting over 775 million and claiming more than 7.04 million lives as of April 13th, 2024 [ 11 ]. Despite the pandemic highlighting the critical role of hospitals and intensive care, it also revealed the limitations of specialized medicine when not complemented by a robust PHC system [ 12 ].

The pandemic brought to light the vulnerabilities of PHC systems, noting a significant decrease in the use of primary care for non-emergency conditions. Routine health services, including immunizations, prenatal care, and chronic disease management, were severely impacted [ 13 ]. The challenges—quarantine restrictions, fears of infection, staffing and resource shortages, suspended non-emergency services, and financial barriers—reduced essential service utilization [ 14 ]. This led to an avoidance of healthcare, further exacerbating health inequalities and emphasizing the need for more resilient PHC systems [ 15 , 16 , 17 ].

Resilient PHC systems are designed to predict, prevent, prepare, absorb, adapt, and transform when facing crises, ensuring the continuity of routine health services [ 18 ]. Investing in the development of such systems can not only enhance crisis response but also foster post-crisis transformation and improvement. This study focuses on identifying global interventions and strategies to cultivate resilient PHC systems, aiding policymakers and managers in making informed decisions in times of crisis.

In 2023, we conducted a scoping review to collect and synthesize evidence from a broad spectrum of studies addressing the COVID-19 pandemic. A scoping review allows for the assessment of literature's volume, nature, and comprehensiveness, and is uniquely inclusive of both peer-reviewed articles and gray literature—such as reports, white papers, and policy documents. Unlike systematic reviews, it typically does not require a quality assessment of the included literature, making it well-suited for rapidly gathering a wide scope of evidence [ 19 ]. Our goal was to uncover the breadth of solutions aimed at bolstering the resilience of the PHC system throughout the COVID-19 crisis. The outcomes of this review are intended to inform the development of a model that ensures the PHC system's ability to continue delivering not just emergency services but also essential care during times of crisis.

We employed Arksey and O'Malley's methodological framework, which consists of six steps: formulating the research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting the pertinent studies, extracting data, synthesizing and reporting the findings, and, where applicable, consulting with stakeholders to inform and validate the results [ 20 ]. This comprehensive approach is designed to capture a wide range of interventions and strategies, with the ultimate aim of crafting a robust PHC system that can withstand the pressures of a global health emergency

Stage 1: identifying the research question

Our scoping review was guided by the central question: "Which strategies and interventions have been implemented to enhance the resilience of primary healthcare systems in response to the COVID-19 pandemic?" This question aimed to capture a comprehensive array of responses to understand the full scope of resilience-building activities within PHC systems.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

To ensure a thorough review, we conducted systematic searches across multiple databases, specifically targeting literature up to December 31st, 2022. The databases included PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Magiran, and SID. We also leveraged the expansive reach of Google Scholar. Our search strategy incorporated a bilingual approach, utilizing both English and Persian keywords that encompassed "PHC," "resilience," "strategies," and "policies," along with the logical operators AND/OR to refine the search. Additionally, we employed Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms to enhance the precision of our search. The results were meticulously organized and managed using the Endnote X8 citation manager, facilitating the systematic selection and review of pertinent literature.

Stage 3: selecting studies

In the third stage, we meticulously vetted our search results to exclude duplicate entries by comparing bibliographic details such as titles, authors, publication dates, and journal names. This task was performed independently by two of our authors, LE and MA, who rigorously screened titles and abstracts. Discrepancies encountered during this process were brought to the attention of a third author, AMM, for resolution through consensus.

Subsequently, full-text articles were evaluated by four team members—LE, MA, PI, and SHZ—to ascertain their relevance to our research question. The selection hinged on identifying articles that discussed strategies aimed at bolstering the resilience of PHC systems amidst the COVID-19 pandemic Table 1 .

We have articulated the specific inclusion and exclusion criteria that guided our selection process in Table 2 , ensuring transparency and replicability of our review methodology

Stage 4: charting the data

Data extraction was conducted by a team of six researchers (LE, MA, PI, MA, FE, and SHZ), utilizing a structured data extraction form. For each selected study, we collated details including the article title, the first author’s name, the year of publication, the country where the study was conducted, the employed research methodology, the sample size, the type of document, and the PHC strengthening strategies described.

In pursuit of maintaining rigorous credibility in our study, we adopted a dual-review process. Each article was independently reviewed by pairs of researchers to mitigate bias and ensure a thorough analysis. Discrepancies between reviewers were addressed through discussion to reach consensus. In instances where consensus could not be reached, the matter was escalated to a third, neutral reviewer. Additionally, to guarantee thoroughness, either LE or MA conducted a final review of the complete data extraction for each study.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing and reporting the results

In this stage, authors LE, MZ, and MA worked independently to synthesize the data derived from the selected studies. Differences in interpretation were collaboratively discussed until a consensus was reached, with AMM providing arbitration where required.

We employed a framework thematic analysis, underpinned by the WHO's health system building blocks model, to structure our findings. This model categorizes health system components into six foundational elements: governance and leadership; health financing; health workforce; medical products, vaccines, and technologies; health information systems; and service delivery [ 2 ]. Using MAXQDA 10 software, we coded the identified PHC strengthening strategies within these six thematic areas.

Summary of search results and study selection

In total, 4315 articles were found by initial search. After removing 397 duplicates, 3918 titles and abstracts were screened and 3606 irrelevant ones were deleted. Finally, 167 articles of 312 reviewed full texts were included in data synthesis (Fig. 1 ). Main characteristics of included studies are presented in Appendix 1.

PRISMA Flowchart of search process and results

Characteristics of studies

These studies were published in 2020 (18.6%), 2021 (36.5%) and 2022 (44.9%). They were conducted in 48 countries, mostly in the US (39 studies), the UK (16 studies), Canada (11 studies), Iran (10 studies) and Brazil (7 studies) as shown in Fig. 2 .

Distribution of reviewed studies by country

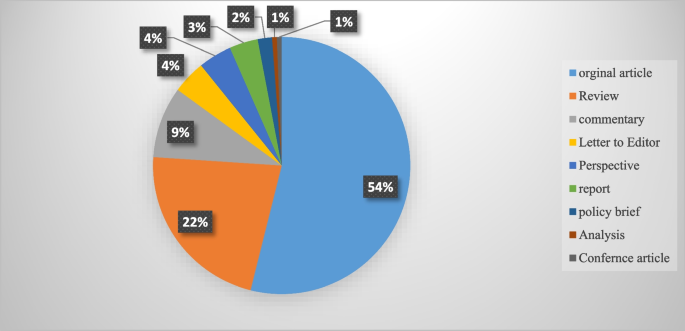

Although the majority of the reviewed publications were original articles (55.1 %) and review papers (21 %), other types of documents such as reports, policy briefs, analysis, etc., were also included in this review (Fig. 3 ).

An overview of the publication types

Strengthening interventions to build a resilient PHC system

In total, 194 interventions were identified for strengthening the resilience of PHC systems to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. They were grouped into six themes of PHC governance and leadership (46 interventions), PHC financing (21 interventions), PHC workforce (37 interventions), PHC infrastructures, equipment, medicines and vaccines (30 interventions), PHC information system (21 interventions) and PHC service delivery (39 interventions). These strategies are shown in Table 3 .

This scoping review aimed to identify and categorize the range of interventions employed globally to strengthen the resilience of primary healthcare (PHC) systems in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our comprehensive search yielded 194 distinct interventions across 48 countries, affirming the significant international efforts to sustain healthcare services during this unprecedented crisis. These interventions have been classified according to the WHO’s six building block model of health systems, providing a framework for analyzing their breadth and depth. This review complements and expands upon the findings from Pradhan et al., who identified 28 interventions specifically within low and middle-income countries, signaling the universality of the challenge and the myriad of innovative responses it has provoked globally [ 178 ].

The review highlights the critical role of governance and leadership in PHC resilience. Effective organizational structure changes, legal reforms, and policy development were crucial in creating adaptive healthcare systems capable of meeting the dynamic challenges posed by the pandemic. These findings resonate with the two strategies of effective leadership and coordination emphasized by Pradhan et al. (2023), and underscore the need for clear vision, evidence-based policy, and active community engagement in governance [ 178 ]. The COVID-19 pandemic posed significant challenges for PHC systems globally. A pivotal response to these challenges was the active involvement of key stakeholders in the decision-making process. This inclusivity spanned across the spectrum of general practitioners, health professionals, health managers, and patients. By engaging these vital contributors, it became possible to address their specific needs and to design and implement people-centered services effectively [ 41 , 42 , 43 ].